Abstract

Replacement of the phenolic hydroxy in 3-((1R,5S,9R)-2-phenethyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-5-yl)phenol (DC-1–76.2), a potent efficacious MOR agonist, with an amide bioisosteric moiety provided a MOR partial agonist with morphine-like potency in the forskolin-induced cAMP accumulation assay and in the [35S]GTPγS functional assay. This amide, 5, had superior metabolic stability in comparison to its precursor in human and mouse liver microsomes. However, in an antinociception study, an assay of pain-depressed locomotion in mice, it was found to possess shorter antinociceptive activity than its precursor. The in vitro and in vivo data enabled the characterization of amide, 5, as a functionally selective, low-efficacy, and low-potency MOR agonist with a relatively short duration of action in vivo. Modification of the N-phenethyl substituent in DC-1–76.2 gave a number of highly interesting partial agonists, and the unexpectedly potent antagonist, 17. The results of molecular docking and binding free energy calculations for DC-1–76.2 and 17 provided details about their receptor interactions and supported their functional roles. Several analogs synthesized were found to have sufficient potency in vitro to warrant further study.

Keywords: mu opioid receptor (MOR), agonists, antagonists, bioisosteres, opioid use disorder (OUD)

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Opioids have a variety of biological effects, most notably analgesia, with side-effects including respiratory depression, gastrointestinal effects, tolerance, and physical dependence.1 The majority of prescribed analgesics, such as morphine, hydrocodone, and oxymorphone are high efficacy μ-opioid receptor agonists (MOR).1 The side-effects of opioids have been said to be a consequence of G-protein activation leading to both G-protein and β-arrestin signaling.2–4 However, studies with transgenic mice indicated that knockout of β-arrestin 2 could protect animals from respiratory depression and constipation induced by opioids.5 Other evidence has pointed to the effectiveness of partial agonists, like buprenorphine. Buprenorphine is a non-selective partial MOR agonist with antagonist activity at KOR and DOR, and has been classified as a Schedule III drug, having moderate or low potential for physical and psychological dependence.6 Buprenorphine has been used for analgesia in the United States since 1981 highlighting the promise of partial agonists. There is a need for other selective partial agonists with fewer side-effects that could be used both as alternative analgesics to those in clinical use and as treatment medications for Opioid Use Disorder (OUD). From our exploration of three-dimensional space around the C9 position of 3-hydroxy-N-phenethyl-substituted 5-phenylmorphans we have designed and synthesized MOR selective partial agonists with efficacies, as determined by the forskolin-induced cAMP accumulation assay, ranging below that of buprenorphine to a little above naltrexone.7, 8 We synthesized all of the possible diastereomers of a specific C9-substituents such as alkyls, alkenes, hydroxyalkyls, and aminoalkyls.7, 9–11 Several of these were potent MOR agonists that were found to depress respiration less than morphine and have less effect on the GI system, as well. Our emphasis on partial agonists, rather than potent high efficacy agonists like morphine or fentanyl, was based on our finding that potent C9-substituted phenylmorphans that were fully efficacious MOR agonists for cAMP inhibition had little or no effect on β-arrestin, yet they still retained the well-known side-effects that plague most of the clinically useful opioids.11 Others have noted similar findings.12, 13

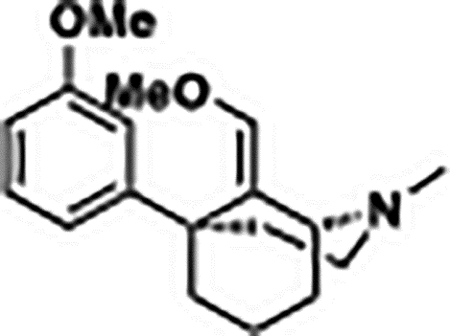

The high efficacy MOR agonist DC-1–76.2 (Figure 1) is a diastereomer of DC-1–76.1.8 It was chosen as our lead molecule for bioisosteric modification of the phenolic moiety and modification of the N-phenethyl side-chain in an attempt to increase metabolic stability and lower its efficacy. We considered that these modifications might also lessen potency and, hopefully, efficacy, hence our choice of a more potent and efficacious diastereomer as the candidate for further exploration. We hoped to retain sufficient potency and lessen the efficacy of DC-1–76.2, to convert it to a metabolically stable partial agonist. The JL-01–0039 and EG-01–0203 (Figure 1) compounds represent MOR partial agonists with approximately the upper and lower efficacy (Emax = 85 ± 5% and 63.3 ± 3.9%) that our former work indicated was essential for our partial agonists to exhibit fewer opioid-like side-effects, as determined in the forskolin-induced cAMP accumulation assay. In the [35S]GTPγS functional assay we considered the useful efficacy for further study to be about 10–20%.

Figure 1.

Previously synthesized partial MOR agonists (DC-01–76.1, 1S,5R,9R-JL-01–0039, and 1S,5R,9R-EG-01–0203) and a high efficacy (DC-01–76.2) MOR agonists.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chemistry:

The synthesis of 1 followed previously published protocols.8, 14, 15 The synthesis of an acetamide bioisostere, 3, proceeded via a triflate intermediate, 2, in the reaction of 1 with phenyl trflimidate with a 97% isolated yield (Scheme 1). The triflate intermediate was converted to acetamide 3, in a Pd-catalyzed C-N coupling reaction utilizing tBuBrettPhos Pd G3 catalyst with a moderate yield.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of bioisostere acetamide (3)a

aReagent and conditions: (a) Phenyl triflimide, TEA, DCM, RT, 97%; (b) K3PO4, Acetamide, tBuBrettPhos Pd G3, tBuOH: H2O, 90 °C, 42%.

The synthesis of the bioisosteric amide, 5, proceeded similarly to 3; the triflate was converted to nitrile, 4, using zinc cyanide and tBuxPhosPdG3, followed by hydrolysis of 4 to amide 5, using hydrogen peroxide in dimethyl sulfoxide (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of bioisostere amide (5)a

aReagent and conditions: (a) tBuXPhos Pd G3, Zn(CN)2, H2O:THF (4:1), 60 °C, 45%; (b) H2O2, K2CO3, DMSO, 25 °C, 68%.

The synthesis of the N-methyl isomers, 10 and 11, was achieved through the synthesis of 6 using previously published protocols.11 Hydrolysis of the enol ether, followed by a second Wittig gave 8 and 9, which were separable by column chromatography. O-Demethylation with boron tribromide, gave us the desired analogs 1R,5S,9S-10 and 1R,5S,9R-11 (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of the N-methyl phenylmorphan diasteroemers 10 and 11.

aReagent and conditions: (a) 6N aq. HCl; (b) KOtBu, MePPh3Br, THF, 53%. (c) BBr3, DCM, 11 (25%), 10 (55%).

To access an N-cyclopropylmethyl phenylmorphan and other N-substituted analogs we developed a synthetic route that utilized a late-stage derivatization of a stable common intermediate 13 (Scheme 4). 1-Chloroethyl chloroformate (ACE-Cl) was found to be the most useful reagent for the ease of removal of the N-methyl moiety from the phenolic ether 9. Subsequent hydrolysis of a carbamate intermediate in refluxing methanol yielded the corresponding secondary amine as a hydrochloride salt that was easily isolated by filtration. Free basing the hydrochloride salt followed by N-Boc protection, gave the desired common intermediate 13 in a 77% yield. Other reagents, including cyanogen bromide and ethyl chloroformate were explored for the N-dealkylation reaction, however, none of them proved superior to ACE-Cl.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of N-substituted analogs via common intermediate 13.

aReagent and conditions: (a) i. ACE-Cl, NaHCO3, 1,2-DCE, ii. MeOH; (b). Boc-anhydride, DMAP, TEA, 77% (c) BBr3, DCM; (d). R-Br or R-OTs, NaHCO3, ACN or DMF, 75°C, 19–59%.

Finally, global deprotection of the phenolic ether and the N-Boc group of 13 using boron tribromide yielded a secondary amine that was directly used for N-alkylation affording the desired analogs in yields ranging from 19–59% (Scheme 4).

Two additional analogs 24 and 25, were synthesized with a similar methodology. N-Demethylation of 9 with ACE-Cl was conducted, but alkylation was done on the secondary amine (Scheme 5) without prior removal of the phenolic ethers, giving N-alkylated phenolic ether intermediates. O-demethylation with boron tribromide provided our two final products, 24 and 25.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of meta-nitro and meta-hydroxy substituted N-phenethyl compounds 24 and 25 via the secondary amine as the common intermediate.

aReagent and conditions: a) i. ACE-Cl, NaHCO3, 1,2-DCE, ii. MeOH, 97%; (b) i. R-Br or R-OTs, NaHCO3, ACN/DMF, 70°C (c) BBr3, DCM (17%-35% over two steps).

Effect of bioisoteric replacement of phenolic hydroxyl:

Structural modification of the lead molecule DC-1–76.2 explored bioisosteric replacement of the C5-phenolic hydroxyl group with acetamide and amide functionalities while keeping the N-phenethyl fragment intact. The aryl acetamide 3 retained the potency of the partial MOR agonist DC-1–76.1 (MOR EC50 ± SEM (nM) 2.73 ± 0.69 and 2.12 ± 0.45, respectively) and was slightly less potent than the high efficacy agonist DC-1–76.2 (1.44 ± 0.48 nM) in the forskolin-induced cAMP accumulation assay (Table 1). In the same assay, 3 was also a highly efficacious compound at MOR with an Emax value of 101.2 ± 0.9% like DC-1–76.2 (94.7 ± 3.1%) which we consider a high potency and higher efficacy agonist compared to the low efficacy agonist DC-1–76.1 (67.3 ± 6.8%) and to DAMGO (MOR %Emax 102.9 ± 1.1%). Gratifyingly, the aryl amide analog, 5, displayed favorable MOR potency and efficacy (Table 1). The bioisostere 5 displayed a MOR EC50 value of 5.28 ± 2.07 nM which was comparable or less potent than DC-1–76.1 and DC-1–76.2, but as importantly, its efficacy (MOR %Emax 75.1 ± 10.4%) was intermediate between that found for DC-1–76.1 and DC-1–76.2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Opioid Receptor Activity Measured in the Forskolin-induced cAMP Accumulation Assaya

| MOR | DOR | KOR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agonist | Antagonistb | Agonist | Antagonistc | Agonist | Antagonistd | ||

| Name | Structure | EC50 ± SEM (nM) (%Emax ± SEM) | IC50 ± SEM (nM) (%Imax ± SEM) | EC50 ± SEM (nM) (%Emax ± SEM) | IC50 ± SEM (nM) (%Imax ± SEM) | EC50 ± SEM (nM) (%Emax ± SEM) | IC50 ± SEM (nM) (%Imax ± SEM) |

| 3 |

|

2.73 ± 0.69 (101.2 ± 0.9%) | N/D | 302.93 ± 40.68 (56.6 ± 8.2%) | N/D | 357.18 ± 108.53 (45.5 ± 3.9%) | N/D |

| 5 |

|

5.28 ± 2.07 (75.1 ± 10.4%) | N/D | 6.01 ± 4.97 (25.2 ± 4.4%) | 497.87 ± 208.37 (117.6 ± 8.0%) | > 10000 | > 10000 |

| 10 |

|

> 10000 | > 10000 | > 10000 | > 10000 | > 10000 | > 10000 |

| 11 |

|

> 10000 | > 10000 | > 10000 | > 10000 | > 10000 | > 10000 |

| 15 |

|

> 10000 | 973.37 ± 505.73 (136.5 ± 12.0%) | >10000 | > 10000 | > 10000 | N/D |

| 16 |

|

0.80 ± 0.26 (100.9 ± 0.9%) | > 10000 (0) | 13.20 ± 6.80 (20.0 ± 4.2%) | 59.76 ± 13.03 (87.1 ± 13.9%) | N/D | N/D |

| 17 |

|

> 10000 | 9.93 ± 3.00 (130.0 ± 11.6%) | N/D | 105.19 ± 21.27 (137.2 ± 9.7%) | > 10000 | N/D |

| 18 |

|

2.05 ± 0.74 (85.8 ± 3.8%) | N/D | >10000 | 52.45 ± 8.43 (149.9 ± 13.2%) | > 10000 (0) | N/D |

| 24 |

|

2.55 ± 0.51 (92.6 ± 1.3%) | N/D | 954.43 ± 501.85 (35.9 ± 5.3%) | 114.06 ± 11.66 (63.5 ± 12.0%) | > 10000 (0) | N/D |

| 19 |

|

3.33 ± 1.29 (74.3 ± 4.3%) | N/D | >10000 | 119.99 ± 18.54 (153.1 ± 15.3%) | > 10000 | N/D |

| 20 |

|

4.16 ± 1.02 (54.8 ± 11.8%) | 273.38 ± 122.87 (61.4 ± 8.2) | >10000 | 303.32 ± 29.24 (163.6 ± 19.5%) | >10000 | N/D |

| 21 |

|

0.40 ± 0.04 (100.8 ± 0.7%) | N/D | 7.19 ± 4.63 (24.2 ± 2.2%) | 62.63 ± 4.05 (87.8 ± 6.7%) | > 10000 (0) | N/D |

| 25 |

|

0.93 ± 0.39 (89.7 ± 1.3%) | N/D | >10000 (0) | 107.17 ± 12.38 (138.7 ± 19.3%) | > 10000 | N/D |

| COMPARISON | |||||||

| DC-1–76.2 |

|

1.44 ± 0.48 (94.7 ± 3.1%) | N/D | >10,000 | 112.9 ± 43.6 (119.1 ± 15.5%) | >10,000 | 74.0 ± 30.5 (97.1 ± 9.2%) |

| DC-1–76.1 |

|

2.12 ± 0.45 (67.3 ± 6.8%) | 45.6 ± 17.3 (18.8 ± 3.8%) | 57.0 ± 21.4 (22.6 ± 3.3%) | N/D | >10,000 | 19.8 ± 9.7 (101.8 ± 19.1%) |

| STANDARDS | |||||||

| Morphine | 5.8 ± 0.3 (102 ± 0.1%) | ||||||

| Naltrexone | 2.14 ± 1.2 (29.61 ± 6.4%) | 10.78 ± 0.98 (103.5 ± 0.6%) | >10,000 | 295.09 ± 47.47 (99.4 ± 1.1%) | 0.64 ± 0.32 (56.5 ± 7.2%) | 5.53 ± 1.02 (41.3 ± 6.8%) | |

| DAMGO | 0.3 ± 0.1 (103 ± 1%) | ||||||

| U50488H | 0.3 ± 0.03 (100 ± 0.3%) | ||||||

| SNC80 | 1.7 ± 0.2 (79 ± 2%) | ||||||

| Nor-BNI | 2.34 ± 0.29 (102.4 ± 1.2%) | ||||||

Inhibition of forskolin-induced cAMP accumulation; cAMP Hunter™ Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO-K1) that express human μ-opioid receptor (OPRM1), human κ-opioid receptor (OPRK1), and human δ-opioid receptor (OPRD1) were used for the forskolin-induced cAMP accumulation assay to determine potency and efficacy of the compounds following the previously established methods;16 to determine % efficacy in forskolin-induced cAMP assays, background readouts of the vehicle control were subtracted from all treatment readouts and then normalized to the forskolin control. Data were then analyzed in GraphPad Prism 10.2.2 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA) using nonlinear regression; values are expressed as the mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments; N/D = not determined.

MOR antagonist potency (IC50) determined versus EC90 of fentanyl; degree of antagonism (Imax) normalized to naltrexone.

DOR antagonist potency (IC50) determined versus EC50 of SNC80; degree of antagonism (Imax) normalized to naltrexone.

KOR antagonist potency (IC50) determined versus EC90 of U50488H; degree of antagonism (Imax) normalized to nor-BNI.

Modification of the N-phenethyl substituent:

The necessity and importance of the N-phenethyl substituent was explored next while keeping the C5-phenolic hydroxyl group of DC-1–76.2 constant. To determine if the N-phenethyl group is essential for biological activity in this series of compounds, we introduced different N-substituents on the nitrogen atom. The activity of these were explored through the synthesis of the N-methyl derivative of two alkenyl diastereomers, 10 and 11 (Scheme 3), and the conversion to an N-cyclopropylmethyl derivative, 1R,5S,9R-15 (Scheme 4). All three of these compounds lost their agonist potency at MOR; none of them displayed any effect in vitro at any opioid receptor, in the cAMP accumulation assay. These results are particularly interesting because the N-methyl substituted phenylmorphans with or without a C9 substituent are known opioid ligands. For example, 5-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-2-methylmorphan and its enantiomer were shown to have antinociceptive activity comparable to that of morphine.17 Strong agonist activity was also noted for C9α-hydroxy N-methyl 5-phenylmorphan,18 while the C9β-methyl substituted analog exhibited antagonist properties.19 Clearly, the addition of a C9-vinyl substituent to the N-methyl 5-phenylmorphan scaffold completely changed the activity of the molecule. This unusual finding led us to obtain the X-ray crystal structure to confirm the structure of 11 (Figure 2). This proved that the molecular structure and chirality of the compounds was correct and was retained throughout the synthesis.

Figure 2.

X-ray crystal structure of 3-((1R,5S,9R)-2-methyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-5-yl)phenol (11). The ellipsoids are shown at the 50% probability level. The second molecule observed in the ASU was removed for clarity.

We also synthesized an N-thienyl substituted derivative 16 (Scheme 4). Sufentanil, a fentanyl analog with a replacement of the phenyl with a thiophene is known to be 5–7 times more potent than fentanyl and has a rapid onset, short duration of action and an unusually high safety margin.20 We wanted to see whether a similar effect would be observed with the C9-substituted phenylmorphans series of compounds. Indeed, introduction of the thienyl group in 16 resulted in enhancement of potency and efficacy (0.80 ± 0.26 nM (100.9 ± 0.9%)) in comparison to the parent compound DC-1–76.2. Several other compounds with substituents on the aromatic ring in the N-phenethyl moiety were also synthesized.

One of these, a nitro substitution at the para position (17) of the N-phenethyl side chain produced a remarkable change in activity from DC-1–76.2, from a potent high efficacy agonist at MOR to a potent MOR antagonist (9.93 ± 3.00 nM) (Table 1). In the 6,7-benzomorphans and 5-(3-hydroxyphenyl)morphans, the para-nitro substituted analogs were found to be potent MOR agonists and we expected a similar result from the para-nitro substituent in our series.21, 22 This change from MOR agonist to antagonist was due to the specific substituent at C9, the position of the nitro moiety on the aromatic ring of the N-phenethyl group and, likely, the stereochemistry of the molecule.

We speculated that the para-nitro substituent of 17 prevented its ability to interact with the key amino acid residues and stabilize the active conformation of the receptor.8 To get further insight into the rationale of this profound change in activity of DC-1–76.2 after introduction of the para-nitro substitution, we conducted a computational study and the results are discussed in the next section. Moreover, we synthesized 18 and 24, with a nitro substitution at the meta and ortho position in the phenethyl side-chain, respectively. The meta analog, as expected, was a potent partial agonist at MOR (2.05 ± 0.74 nM) with relatively high efficacy (85.8 ± 3.8%). The ortho analog was still a potent agonist at MOR (2.55 ± 0.51 nM), but it displayed high efficacy (92.6 ± 1.3%).

A fluoro-substituent at the para position (19) resulted in a compound with similar potency to DC-1–76.1 and with the desired reduced efficacy (3.33 ± 1.29 nM (74.3 ± 4.3%)). A hydroxyl group at the para position (20) was a moderately potent agonist (4.16 ± 1.02 nM) at MOR with a low efficacy (54.8 ± 11.8%) in the cAMP accumulation assay (Table 1); an efficacy that may be borderline for needed activity. Due to the borderline useful efficacy for 20, we synthesized the ortho and meta derivatives, 21 and 25. The ortho-hydroxy substituted N-phenethyl phenylmorphan was a very potent agonist (0.40 ± 0.04 nM) at MOR with very high efficacy (100.8 ± 0.7%). The meta-hydroxy was also a potent agonist (0.93 ± 0.39 nM) with somewhat lower efficacy (89.7 ± 1.3%) at MOR in the cAMP accumulation assay.

Computational studies:

In silico studies were carried out to analyze at an atomistic level the transformation of the potent full MOR agonist DC-1–76.2 into a potent MOR antagonist 17. The following computational protocol has been applied to evaluate the effects of MOR agonist and antagonist and to understand their differences:

3D targets selection to evaluate Active and Inactive conformations

Molecular docking to define a putative binding mode and note any differences

Binding energy calculations to accurately clarify the binding free energies

The binding free energy results for DC-1–76.2 and 17, provided insightful details about their receptor interactions and potential functional roles (Table 2).

Table 2.

Binding free energies of DC-1–76.2 and 17 for the inactive and active forms of MOR

| Binding free Energy estimation (kcal/mol) | ||

|---|---|---|

| DC-1-76.2 | 17 | |

| MOR INACTIVE FORM | −64.56 | −78.52 |

| MOR ACTIVE FORM | −67.35 | −65.78 |

According to the experimental data, in the protein’s inactive form, 17 exhibited a significantly stronger binding free energy (-78.52 kcal/mol) compared to DC-1–76.2 (-64.56 kcal/mol). This suggests that 17 may more effectively stabilize the inactive receptor conformation, consistent with its role as an antagonist. The stronger binding energy likely reflects enhanced interactions, such as increased hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, or electrostatic stabilization (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Binding mode of compounds 17 (panel a) and DC-1–76.2 (panel b) in the MOR inactive conformation (green cartoon). The interacting residues are reported in bold. Electrostatic interactions, π-cation, π-π, and hydrogen bonds are reported in pink, green, cyan and yellow dashes, respectively.

On the other hand, regarding the active conformation, DC-1–76.2 showed a binding free energy of −67.35 kcal/mol, which is slightly more favorable than 17’s −65.78 kcal/mol. This indicates that DC-1–76.2 is better suited to stabilize the receptor in its active state, supporting its role as an agonist. Conversely, reduced binding energy of 17 in the active conformation may hinder its ability to promote the receptor’s conformational changes required for activation.

As a general comment, the significant drop in binding energy for 17 between the inactive (-78.52 kcal/mol) and active (-65.78 kcal/mol) forms suggests that this compound destabilizes the active receptor conformation, reinforcing its antagonist behavior. Conversely, the small energy difference for DC-1–76.2 between the inactive and active forms (−64.56 to −67.35 kcal/mol) indicates its capacity to maintain receptor stability in both conformations, facilitating activation and signal propagation.

In the inactive state, 17 exhibited robust binding through electrostatic interactions, π-cation (TYR 150-TM3 and HIS 299-TM6) and π-π stacking (TYR150-TM3), and hydrogen bonds (CYS219-ECL2) with key residues, stabilizing the receptor (Figure 3a). DC-1–76.2 showed similar yet distinct interactions, notably maintaining connections with ASP 149-TM3 and TYR 150-TM3, and interacting uniquely with LEU 234-TM5 (Figure 3b).

In the active state, 17 interacted differently than DC-1–76.2, with the antagonist forming electrostatic interactions with GLU231-TM5 and LYS235-TM5, and both compounds engaging ASP149-TM3 and TYR150-TM3. Figure 4 shows the main differences between 17 and DC-1–76.2, and highlights the different structural engagements. These findings provided insight into how ligand interactions could dictate receptor function, aiding in the design of selective MOR modulators.

Figure 4.

Binding mode of compounds 17 (panel a) and DC-1–76.2 (panel b) in the MOR active conformation (cyan cartoon). The interacting residues are reported in bold. Electrostatic interactions, π-cation, and hydrogen bonds are reported in pink, green, and yellow dashes, respectively.

Metabolic stability studies:

The metabolic stability of the synthesized analogs was assessed using liver microsomes and the cytosolic fractions. The Tier II stability assay is a multi-point microsome and cytosol stability assay conducted in three different species, human, mouse and rat. The aryl acetamide, 3, and amide, 5, showed an increase in stability for the two bioisosteres, in human and mouse microsomes (3 t1/2: 21.3 and 6.40 min; 5 t1/2: 40.4 and 16.7 min) (Table 3). Their stability in rat liver microsomes (RLM) was somewhat limited (3 t1/2: 3.0 and 5 t1/2 3.2 min), with the half-lives similar to the half-lives of the two diastereomers DC-1–76.1 and DC-1–76.2 (t1/2 rat: 2.40 and 6.90 min, respectively) (Table 3). The methyl analogs 10 and 11 showed enhanced stability in all three species, human, mouse and rat (10 t1/2: >120, 72.1 and 50.8 min, 11 t1/2: 68.9, 21.8 and 62.6 min). These two compounds unfortunately, displayed no MOR agonist activity. The cyclopropylmethyl analog, 15, was another compound with no MOR agonist activity, but it showed very similar stability to DC-1–76.1 in human microsomes (15 t1/2: 8.7; DC-1–76.1 t1/2: 8.0 min) (Table 3). The thienyl derivative, 16, which was a potent and highly efficacious agonist at MOR displayed less stability than DC-1–76.2 in human microsomes (16 t1/2: 8.21 min; DC-1–76.2 t1/2: 12.0 min). The nitro substitution at the para position, 17, displayed an increase in stability in human, mouse and rat microsomes when compared to DC-1–76.2 (17 t1/2: 16.8, 9.31, 12.9 min vs DC-1–76.2 t1/2: 12.0, 4.7 and 6.9 min). The switch of the nitro substitution from para to meta (18) and ortho (24) resulted in a decrease in stability in all three species human, mouse and rat (18 t1/2: 10.6, 3.54, 1.98 min; 24 t1/2: 5.02, 1.22 and 0.41 min), with 24 being more unstable than our lead compound DC-1–76.1. The compound with the fluoro substituent at the para position, 19, had very similar stability to DC-1–76.2 in all three species human, mouse and rat (19 t1/2: 11.8, 5.26, 7.60 min). The para-hydroxy, 20, was a moderate potency and low efficacious MOR agonist, this compound was our most stable compound in all three species, human, mouse and rat (20 t1/2: 88.1, 12.5 and 27.8 min). The meta-hydroxy, 25, resulted in another stable compound in human and rat microsomes (25 t1/2: 27.0 and 9.65 min), but limited stability in mouse microsomes (25 t1/2: 4.02 min). The hydroxyl in the ortho position, 21, resulted in a decrease in the stability, with a 10-fold reduction in stability in human microsomes in compartion with 20 (21 t1/2: 8.35 min vs 20 t1/2: 88.1 min).

Table 3.

Physicochemical properties and in vitro ADME assessments.

| Compound ID | Kinetic aqueous solubility (μg/mL) | Mutli-point microsomal stability t1/2 (min) | Multi-point cytosolic stability t1/2 (min) | PAMPA permeability Papp (10E-6 cm/s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Mouse | Rat | Human | Mouse | Rat | |||

| DC-1-76.1 | 34.0 | 8.00 | 1.10 | 2.40 | >120 | 114 | 81.8 | N/F |

| DC-1-76.2 | 34.0 | 12.0 | 4.70 | 6.90 | 80.7 | 71.9 | >120 | N/F |

| 3 | 38.0 | 21.3 | 6.40 | 3.00 | 78.0 | 22.9 | 88.1 | 731.0 |

| 5 | 5.1 | 40.4 | 16.7 | 3.20 | >120 | >120 | >120 | N/F |

| 10 | >25 | >120 | 72.1 | 50.8 | >120 | >120 | 116 | N/F |

| 11 | >25 | 68.9 | 21.8 | 62.6 | 97.9 | 112 | >120 | N/F |

| 15 | >29 | 8.7 | 2.7 | 9.70 | >120 | >120 | 108 | >1000 |

| 16 | >35 | 8.21 | 1.66 | 1.04 | >120 | >120 | >120 | N/F |

| 17 | 10.6 | 16.8 | 9.31 | 12.9 | >120 | 105 | >120 | N/F |

| 18 | >39 | 10.6 | 3.54 | 1.98 | >120 | >120 | >120 | >1000 |

| 19 | >36 | 11.8 | 5.26 | 7.60 | >120 | 108 | 79.4 | N/F |

| 20 | >34 | 88.1 | 12.5 | 27.8 | >120 | >120 | >120 | N/F |

| 21 | N/F | 8.35 | 1.30 | 1.00 | >120 | 105 | >120 | N/F |

| 24 | >39 | 5.02 | 1.22 | 0.41 | 112 | 102 | >120 | N/F |

| 25 | N/F | 27.0 | 4.02 | 9.65 | >120 | >120 | >120 | N/F |

N/F = not found

The majority of the newly synthesized analogs were found to be stable in the liver cytosol assay with half-lives ranging between 22.9 and >120 min (Table 3). Compound 3 was the only compound with lower cytosol stability in human, mouse and rat (t1/2: 78.0, 22.9, 88.1 min, respectively) than the lead molecule DC-1–76.1 (t1/2: >120, 114, 81.8 min) and its diastereomer DC-1–76.2 (t1/2: 80.7, 71.9, >120 min) in all three species. Moreover, all but one compound, the amide 5, had moderate aqueous solubility as determined in the Pion’s patented μSOL assay (Table 3). The permeability of our compounds using the Parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA) could not be determined in most cases, possibly due to one of the following reasons: non-specific binding, compound precipitation due to insolubility, weak UV signal or compound having high affinity to the lipid bilayer.

Since the amide, 5, was a potent agonist with moderate efficacy, and increased stability, we decided to further assess it in a radioligand binding assay and [35S]GTPγS functional assay for MOR (Table 4). 5 bound to the MOR with high affinity (Ki = 1.24 nM), which was intermediate between DC-1–76.2 (0.50 nM) and DC-01–76.1 (1.91 nM). It also stimulated MOR-mediated [35S]GTPγS binding with an EC50 value of 23.33 ± 6.45 nM, which was more potent than DC-01–76.1, but less potent than DC-1–76.2 (36.97 ± 15.47 and 6.73 ± 1.35 nM, respectively). The efficacy determined for 5 (%Emax 15.37 ± 1.80) was intermediate between that found for DC-1–76.1 and DC-1–76.2 (%Emax: 10.54 ± 0.82% and 20.09 ± 0.78%, respectively), corroborating the findings of the cAMP assay.

Table 4.

MOR radioligand binding assay (Ki, nM) and MOR [35S]GTPγS functional assaya

| Compounds | Molecular Structure |

[3H]NLX binding Ki (nM) |

GTPγS % Emax of (DAMGO) |

GTPγS EC50 (nM) |

GTPγS % Imax of (DAMGO) |

GTPγS IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 |

|

1.24 ± 0.17 | 15.37 ± 1.80 | 23.33 ± 6.45 | N/D | N/D |

| DC-1-76.2 |

|

0.50 ± 0.05 | 29.09 ± 0.78 | 6.73 ± 1.35 | N/D | N/D |

| DC-1-76.1 |

|

1.91 ± 0.13 | 10.54 ± 0.82 | 36.97 ± 15.47 | N/D | N/D |

| Morphine | 1.20 ± 0.16 | 88.30 ± 4.86 | 123.0 ± 23.56 | N/D | N/D | |

| 17 |

|

0.41 ± 0.05 | N/D | N/D | 98.42 ± 4.24 | 16.21 ± 2.52 |

The values are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Membranes for all radioligand binding assays were prepared from CHO cells stably expressing cloned MOR.

Values are from reference 9 (Chambers et al. 2022).

N/D = not determined.

The only potent antagonist of the series was also assessed in a radioligand binding assay and [35S]GTPγS functional assay for MOR (Table 4). Compound 17 exhibited high binding affinity towards MOR (Ki = 0.41 ± 0.05 nM). It inhibited MOR-mediated [35S]GTPγS binding with an IC50 value of 16.21 nM. The maximal percent inhibition was 98.42.

5 was also evaluated in a radioligand binding assay and [35S]GTPγS functional assay for KOR and DOR (Table 5). 5 bound to the KOR with a moderate affinity (Ki = 48.69 nM) and DOR with a weaker affinity (Ki = 237 nM). 5 did not stimulate KOR-mediated [35S]GTPγS binding at up to 30 μM. It affected DOR-mediated [35S]GTPγS binding with an EC50 of 1455.4 nM, but with a negative efficacy (%Emax −6.98 ± 1.21).

Table 5.

KOR and DOR radioligand binding assay (Ki, nM) and [35S]GTPγS functional assaya

| KOR | DOR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Receptor binding | GTPγS | GTPγS | Receptor binding | GTPγS | GTPγS |

| Ki (nM) | % Emax of (DAMGO) | EC50 (nM) | Ki (nM) | % Emax of (DAMGO) | EC50 (nM) | |

| 5 | 48.69 ± 7.065 | No Stim | N/A | 237.04 ± 39.19 | −6.98 ± 1.21 | 1455.4 ± 593.84 |

The values are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Membranes for all radioligand binding assays were prepared from CHO cells stably expressing the cloned DOR and KOR.

In vivo: Antinociception in an assay of pain-depressed locomotion in mice.

The in vivo antinociceptive potency, effectiveness, and time course of 5, were evaluated in a validated assay of pain-depressed locomotor activity in mice that was used previously to characterize effects of a wide range of other opioids, including DC-1–76.1 and DC-1–76.2.14, 23, 24 As discussed at length in previous review articles, assays of pain-related behavioral depression have numerous strengths for analgesic drug development, including (1) their assessment of pain-related behavioral impairment as a class of endpoints that is also clinically important for pain diagnosis and treatment in humans, and (2) their relative resistance to false-positive effects by sedative drugs, which can produce analgesia-like effects in conventional procedures but only exacerbate pain-related functional impairment.25, 26 Moreover, as with conventional procedures, assays of pain-depressed behavior readily enable in vivo comparisons of drug potencies, efficacies, and time courses. Locomotor activity was evaluated during 15-min sessions in a chamber that consisted of two compartments connected by a doorway that was obstructed by a 1-inch-tall barrier. Data were collected for two locomotor endpoints: (1) “Crosses” between the compartments, which required vertical locomotion for mice to surmount the barrier in the doorway, and (2) “Movement” defined as the total number of photobeam breaks summed across both compartments and requiring only horizontal locomotion. In this procedure, intraperitoneal injection of 0.56% lactic acid (IP acid) produces a pain-related depression of both Crosses and Movement, and drugs are evaluated for their effectiveness to alleviate this IP acid-induced behavioral depression and restore locomotion to baseline levels.

Results with 5 are shown in Figure 5. After administration of Vehicle alone, there was a high number of both Crosses and Movement Counts, and administration of Vehicle + IP acid produced a significant decrease in both Crosses (t=3.551, p=0.0009) and Movement (t=11.56, p<0.0001). 5 administered alone significantly increased both Crosses [F(4,55)=3.76, p=0.0090; different from Vehicle at 18 mg/kg] and Movement [F(4,55)=9.01, p<0.0001, different from Vehicle at 10–18 mg/kg]. Similarly, 5 produced a significant antinociceptive attenuation of IP acid-induced depression of both Crosses [F(4,55)=6.32, p=0.0003; different from Vehicle+IP acid at 18 mg/kg] and Movement [F(4,55)=8.11, p<0.0001, different from Vehicle at 10–18 mg/kg] (Figure 5). There were no Sex x Dose interactions for effects of either 5 alone or 5 + IP acid on either crosses or movement (data not shown). For comparison, Figure 5 also shows the previously published effects of DC-1–76.1 and DC-1–76.2.14 DC-1–76.1 has lower MOR efficacy than 5, and when administered alone, DC-76.1 did not alter either locomotor endpoint, although like 5, it significantly attenuated IP acid-induced depression of both Crosses and Movement. DC-1–76.2 has higher MOR efficacy than 5, and when administered alone, DC-1–76.2 significantly stimulated Crosses but not Movement. Conversely, when administered before IP acid, DC-1–76.2 failed to alleviate IP acid-induced depression of Crosses but did alleviate IP acid-induced depression of Movement. Both DC-1–76.1 and DC-1–76.2 were more potent than 5.

Figure 5.

Antinociceptive effects of 5, DC-1–76.1, and DC-1–76.2 in an assay of pain-depressed behavior in mice. Abscissae: dose in mg/kg. Ordinates: number of crosses between compartments during each session (left panels; vertical locomotion) and number of movement counts during each session (right panels, horizontal locomotion). Each drug was tested both alone (circles) and as a pretreatment to IP 0.56% lactic acid as a noxious stimulus (triangles). Each point shows mean ± SEM in 12 mice, and filled points are significantly different from vehicle (Veh) as determined by a significant one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test (p < 0.05). Data with DC-1–76.1, and DC-1–76.2 were published previously.14

Figure 6 shows the time course of antinociception produced by 18 mg/kg of 5. There was a significant effect of time for 5 effects on both Crosses [F(3,44)=7.53, p=0.0004] and Movement [F(3,44)=7.65, p=0.0003], but this effect was significantly different from Vehicle treatment only at 30 min on both endpoints; antinociception was no longer apparent after 60 min. The Sex x Time interaction was not significant for either endpoint (data not shown). For comparison, Figure 6 also shows the previously published time course of antinociception produced by 3.2 mg/kg DC-1–76.1.14 DC-1–76.1 antinociception had time course equal to or longer than that of 5.

Figure 6.

Time course of antinociception produced by 18 mg/kg 5 and 3.2 mg/kg DC-1–76.1. Abscissae: Time in min between drug administration and session onset. Points above “Veh” show effect of vehicle administered 30 min before session onset, and IP 0.56% lactic acid was always administered 5 min before session onset. Ordinates: number of crosses between compartments during each session (left panels; vertical locomotion) and number of movement counts during each session (right panels, horizontal locomotion). Each point shows mean ± SEM in 12 mice, and filled points are significantly different from 30-min vehicle pretreatment (Veh) as determined by a significant one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test (p < 0.05). Data with DC-1–76.1 were published previously.14

Taken together, these results are consistent with the characterization of 5 as a functionally selective, low-potency, and low-efficay MOR agonist with a relatively short duration of action in vivo. Regarding MOR selectivity, in vitro data indicated that 5 displayed similar potency for its MOR and weak DOR agonist effects, but antinociception likely reflected MOR actions because DOR agonists do not produce antinociception in this procedure.23 Regarding potency, the approximately 3- to 10-fold lower in vivo potency of 5 relative to DC-1–76.2 and DC-1–76.1 is consistent with its lower in vitro potency in binding and functional assays. Regarding efficacy, previous studies with MOR agonists across a broad range of efficacies have shown that intermediate MOR efficacy agonists like buprenorphine produce behavioral profiles similar to that observed here for 5 with locomotor stimulation when the drug is administered alone along with significant but partial antinociceptive relief of pain-related depression of Crosses and Movement when administered before IP acid.14, 24 The similar potencies for 5 to stimulate locomotion when administered alone and to partially alleviate IP acid-induced locomotor depression raise the possibility that antinociceptive effects may have resulted from locomotor stimulation rather from pain relief. However, substantial previous evidence suggests that locomotor stimulation by MOR agonists administered alone is not sufficient to predict relief of IP acid-induced behavioral depression. In the data presented here, for example, the low-efficacy MOR agonist DC-1–76.1 produced antinociception without stimulating either locomotor endpoint when administered alone, whereas the higher efficacy MOR agonist DC-1–76.2 significantly stimulated crosses when administered alone but failed to significantly alleviate IP acid-induced depression of crosses (Figure 5).14 A similar dissociation between locomotor stimulation by drugs alone and antinociception by drugs administered as a pretreatment to IP acid has been found for other opioid and non-opioid drugs.14, 23, 24 Additionally, previous studies with other opioids including DC-1–76.1 found that MOR agonists are effective to alleviate pain-related depression of locomotor activity produced by the noxious IP acid stimulus but not pain-independent depression of activity produced by the nauseant agent lithium chloride.14, 24 Taken together, these findings suggest that MOR agonist antinociception in this procedure occurs in addition to rather than because of its locomotor stimulant effects.

Lastly, regarding time course, 5 had a shorter antinociceptive time course than DC-1–76.1 as a comparator (Figure 6). This shorter duration of action is not consistent with the higher stability of 5 in liver microsomes preparations in human and mice, in particular. This discrepancy suggests that 5 may be subject to relatively rapid metabolism via non-hepatic mechanism, such as plasma esterases, and more rapid metabolism might also contribute to the lower potency of 5 in comparison to DC-1–76.1.

In conclusion, 5 was found to be a partial agonist; it displayed superior metabolic stability in comparison to its precursor in human and mice liver microsomes. In an antinociception study, an assay of pain-depressed locomotion in mice, it was found to possess a shorter antinociceptive activity than its precursor. Three N-phenethyl substituted compounds, the meta-nitro (18), the para-fluoro (19) and the meta-hydroxy (25) N-phenethyl phenylmorphans were found to be MOR partial agonists with potencies of twice to 6 times that of morphine and efficacies (%Emax) between 74 and 90% in the cAMP functional assay, worthy of extended study. An antagonist (17) was discovered with similar potency to naltrexone in the cAMP accumulation assay.

Methods:

In Vitro Assays:

Cell Lines and Cell Culture for cAMP Accumulation Assay

cAMP Hunter™ Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO-K1) expressing human μ-opioid receptor (OPRM1, catalog # 95–0107C2), human δ-receptor (OPRMD1, catalog # 95–0108C2), and human κ-opioid receptor (OPRMK1, catalog # 95–0088C2) were purchased from Eurofins DiscoverX (Fremont, CA, USA). All cell lines were maintained in F-12 media with 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA), 1% penicillin/streptomycin/ʟ-glutamine (Life Technologies), and 800 μg/mL geneticin (Mirus Bio, Madison, WI, USA), except for the media for the PathHunter™ cells that was supplemented with an additional 300 μg/mL hygromycin B (Mirus Bio). All cells were grown at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator.

Forskolin-Induced cAMP Accumulation Assays

Assays were performed as previously described.16 Briefly, the cAMP Hunter cells were plated in a 384-well white tissue culture microplate at a 10,000 cells/well density and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Stock solutions of compounds at 5 mM were prepared in DMSO, and then 9-dose of 100X solutions were prepared by serial dilution with DMSO. Subsequently, these 100X solutions were further diluted with assay buffer consisting of Hanks’s buffered salt solution, HEPES, and forskolin to generate the 5X working solutions. In the agonist assay, cells were treated with compounds and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. In the antagonist assay, cells were pretreated with compounds for 15 min at 37 °C followed by 30 min incubation at 37 °C with selected agonists at their EC50 or EC90 dose. The HitHunter cAMP Assay for Small Molecules by Eurofins DiscoverX (Fremont, CA, USA) was then used according to the manufacturer’s directions and the BioTek Synergy H1 hybrid and Cytation 5 plate readers (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) and Gen5 Software version 2.01 (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) were used to quantify luminescence.

Culturing for Competition Radioligand Binding Assay and [35S]GTPγS Functional Assay

All radioligand in vitro binding assays were performed using Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably transfected with mouse mu opioid receptor (mMOR-CHO). Cells were cultured and membrane homogenates were collected as previously described.27 All assays were performed in duplicate and repeated at least three times.

Competition Radioligand Binding Assay

Competitive binding assays were performed to determine ligand affinity for MOR, KOR and DOR as previously described.8, 27–29 Briefly, mMOR-, mKOR-, or hDOR-CHO membrane homogenates containing 15–20 μg (MOR and KOR) or 10 μg (DOR) protein were incubated with 1.45 nM [3H]naloxone, 0.29 nM (KOR) or 1.45 nM [3H]diprenorphine with or without varying concentrations of test ligands in TME buffer (50 mM Tris, 3 mM MgCl2, and 0.2 mM EGTA, pH 7.7) for 1.5 h at 30 °C. Bound radioactivity was determined via liquid scintillation counting, and specific binding was determined as the difference in binding obtained in the absence and presence of 5 μM naltrexone, U50,488-H or SNC-80 for MOR, KOR or DOR binding, respectively.

[35S]GTPγS Functional Assay

[35S]GTPγS functional assays were performed to determine ligand potency and efficacy as described3–5. Briefly, mMOR-, mKOR-, or hDOR-CHO membrane homogenates containing 9–12 μg of membrane protein were incubated in TME buffer with 100 mM NaCl, 20 μM GDP, 0.1 nM [35S]GTPγS with and without varying concentrations of test compounds in a final volume of 500 μL for 1.5 h at 30 °C. Additionally, 3 μM of DAMGO, U50,488-H or SNC-80 was used as a reference for a maximally effective concentration of a full MOR, KOR and DOR agonist, respectively. Basal binding was determined in the absence of agonist and non-specific binding was determined using 10 μM unlabeled GTPγS. Bound [35S]GTPγS was isolated by filtration, and radioactivity was determined via scintillation counting. Net-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding was defined as specific agonist-stimulated binding minus specific basal binding. Data were normalized as % of maximal DAMGO stimulation, defined as (net-stimulated binding by ligand/net-stimulated binding by full agonist) ×100.

Kinetic Solubility Assay

Pion’s patented μSOL assay was used for kinetic solubility determination as previously published.30

Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay (PAMPA):

Stirring double-sink PAMPA method (patented by pION Inc.) was employed to determine the permeability of compounds via PAMPA as previously published.31

Multi Species Multi-Point Metabolic Stability Assay

Microsome Stability Assay:

Microsome Stability Assay: Briefly, each reaction mixture (110 μL) consisted of a test article (1 μM), mix gender human, male Sprague Dawley rat or male CD-1 mouse microsomal fractions (0.5 mg/mL), and NADPH regenerating system in phosphate buffer at pH 7.4. Samples were incubated in 384-well plates at 37°C for 0, 5, 10, 15, 30 and 60 min. Sample analysis and half-life calculations were performed using a previously described method.32, 33

Cytosol Stability Assay:

Briefly, Each 110 μL reaction mixture contained 1 μM test compound and 2 mg/mL human, mouse or rat cytosol fractions in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Samples were incubated at 37°C for 0, 5, 10, 15, 30, and 60 minutes in 384-well plates. Sample analysis and half-life calculations followed a previously described method.34

In Vivo Methods:

General Experiment Design

Experimental procedures were identical to those described previously in studies that focused on opioid agonists.14, 23, 24 Each mouse was tested only once, and different groups of 12 mice (six females, six males) were used to evaluate drug effects at each dose or timepoint. We have previously presented a detailed rationale for this group size and sex allocation.35 For testing, groups of mice were brought from the housing room to the procedure room at least 1 h before injections, tested according to the procedures described below, returned to the housing room at the end of the day, and euthanized by the end of the week. Investigators were not blinded to treatment conditions because data collection for locomotor studies was automated by computer software and data from all mice were included for all experiments (i.e., there were no exclusion criteria, and no data were excluded). In vivo experiments were approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were performed in accordance with the National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Apparatus

Locomotor activity was assessed as described previously using plexiglass and metal test boxes housed in sound-attenuating chambers (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA) and located in a procedure room separate from the housing room. Each box had two adjacent compartments (16.8 × 12.7 cm2 floor area × 12.7 cm high) separated by a wall. One compartment had black walls with a bar floor. The other compartment had white walls with a wire-mesh floor. Additionally, each compartment had a clear plexiglass lid fitted with a house light as well as six photobeams arranged at 3 cm intervals across the long wall and 1 cm above the floor. Photobeam breaks were monitored by a microprocessor operating Med Associates software (MedPC 5). The wall separating the two compartments contained a central door (5 cm wide × 6 cm high) obstructed by a 1-inch (2.54 cm) tall stainless-steel wire-mesh barrier that had to be surmounted for mice to cross back and forth between the two compartments.

Procedure

DH-1–106 was dissolved in a vehicle of 5% ethanol, 5% emulphor, and 90% saline and tested under three conditions. First, the vehicle and a range of drug doses (1–32 mg/kg) were tested alone with the vehicle or drug administered SC 30 min before a 15 min test session. Second, the vehicle and the same doses were tested as a pretreatment to IP injection of 0.56% lactic acid (0.56% IP lactic acid). Lastly, in time course studies, a dose of 18 mg/kg DH-1–106 was administered at 30, 60, or 120 min before a 15 min test session, and 0.56% lactic acid was again administered 5 min before the session. Effects of vehicle administered 30 min before IP acid served as the control for time-course experiments. At the start of each locomotor test session for each mouse, the mouse was placed into the black compartment of the two-compartment chamber, and data were collected for 15 min.

Data Analysis

Two dependent measures were determined for each session in each mouse: (1) “Crosses”, defined as the number of crosses between the compartments and requiring mice to surmount the vertical barrier in the doorway, and (2) “Movement”, defined as the total number of beam breaks summed across both compartments and requiring only horizontal locomotor activity. Dose-effect and time-course data were averaged across mice within a given treatment and submitted to analysis that proceeded in two steps. First, data for a given manipulation were pooled across sexes and analyzed by one-way ANOVA. A significant ANOVA was followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test to compare test treatments with vehicle treatment. Second, data were segregated by sex and analyzed by two-way ANOVA, with sex as one of the variables. A significant main effect of Sex or Sex x Treatment interaction was followed by a Holm–Sidak post hoc test. In addition to this primary analysis of dose-effect data within a given drug, baseline data collected with control treatments (Vehicle vs. Vehicle + IP acid) were compared across drugs using t-tests. Prism 9.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for all ANOVAs and t-tests, and the criterion for significance was p < 0.05.

X-ray diffraction

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data on 11 was collected using Cu Kα radiation and a Bruker SMART APEX II CCD area detector. The crystal was prepared for data collection by coating with high-viscosity microscope oil. The oil-coated crystal was mounted on a micromesh mount (MiTeGen, Inc., Ithaca NY, USA) and transferred to the diffractometer and a data set collected at 100(2) K. The structures were solved by direct methods and refined by full-matrix least-squares on F2 values using the programs found in the SHELXL suite (Bruker, SHELXL v2014.7, 2014, Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, WI, USA). Corrections were applied for Lorentz, polarization, and absorption effects. Parameters refined included atomic coordinates and anisotropic thermal parameters for all non-hydrogen atoms. The H atoms were included using a riding models. There are two crystallographically unique molecules in the ASU with both showing the same stereo chemistry. The stereochemistry of each carbon was determined via the orientation of the molecules shown in Figure 2. It is of note that is one alert B observed in the cif. Due to minor absorption in the crystal there were two outlying reflections. This not a major concern and all other alerts are C or G.

Atomic coordinates for 11 have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, deposition number 2393608. Copies of the data can be obtained, free of charge, on application to CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge, CB2 1EZ, UK (fax: +44(0)-1223–336033 or e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

Computational Methods

3D model selection and preparation

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) entries 7UL4 [https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-022-00859-8] and 8EF5 [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.09.041] were selected for the in silico studies and provided structural insights into MOR in its inactive and active states, respectively. In particular, PDB 7UL4: is the inactive state of the mouse μ-opioid receptor (MOR) bound to the inverse agonist alvimopan, stabilized by a nanobody. Determined using cryo-EM; In this case, the human form has been remodeled based on the murine one, by using the Dompé proprietary pipeline belonging to their Comprehensive Therapeutic Target Database platform.

The pdb 8EF5 is the active state of MOR bound to fentanyl and a Gi-protein. Reveals key fentanyl interactions with transmembrane regions, providing insights for selective G-protein signaling.

The protein was prepared using Maestro Protein Preparation Wizard [Schrödinger Release 2024, Protein Preparation Wizard, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, USA.]. Hydrogen atoms were added, and water molecules were removed from the protein structure.

Docking engine and procedure

Docking simulations were conducted using LiGen (program (DOI: 10.1021/ci400079k, DOI: 10.1021/ci400078g, arXiv:2110.11644), a proprietary software developed by Dompé. LiGen employs a geometric fitting procedure combined with rigid body minimization. Specifically, the docking engine follows a workflow where three docking scores are computed: first, the Pacman Score (PS) estimates geometric fitting by evaluating the interaction between a ligand pose and the pocket based on shape and volume complementarity. Next, the Chemical Score (CS), which represents the ligand binding interaction energy, is calculated using an in-house developed scoring function. The final step involves a rigid body minimization of the docked ligand within the binding site, resulting in an optimized chemical score (Csopt). Poses that do not meet geometric fitting or threshold values of user-defined parameters are discarded.

The GENEOnet tool was used to define protein binding pockets to guide the docking experiments.36 This software from Dompé Farmaceutici SpA integrates the geometric and explainability features of GENEOs with a network architecture, forming a knowledge-based machine learning paradigm. GENEOnet utilizes knowledge such as lipophilicity, hydrophilicity, and electrostatic information, which are essential for identifying binding sites. For each chemical-physical parameter, a GENEO37 is defined to identify areas with optimal values for these parameters.

Binding Free energy Calculation

This section allows to evaluate the ligands behaviour by calculating free energy based on their capacity to interact with different target conformations. The MM/GBSA free energy was computed by:

| (1) |

Equation 1 represents the total Gibbs free energy (G) of a given system, which is the sum of various energy components such as the internal energy (Eint), electrostatic energy (Eele), van der Waals energy (Evdw), polarization energy (Gpol), non-polar solvation energy (Gnp), and the entropy-energy product (TS). The solvation free energies, denoted as Gpol and Gnp, represent the thermodynamic quantities associated with the solvation of polar and nonpolar compounds, respectively. T represents the absolute temperature, while S estimates the entropy. The binding free energy between a protein and a ligand was then estimated by using the following equation:

| (2) |

In Equation 2, PrLig represents the Protein-Ligand complex, Pr and Lig indicate the protein and the ligand, respectively. For determining the solvation free energy contribution, the linearized Generalized Born equation was solved using the in-built Python script MMPBSA.py of AMBER20, integrated in a proprietary and fully automated workflow called “Binding Free Energy Exscalate” (BFEx).

General Synthetic Methods

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Acros Organics, Fisher Scientific, Combi-blocks, Oakwood Chemical, Macron Fine Chemicals and used without further purification. Yields refer to chromatographically homogeneous materials. Flash column chromatography was performed on a Teledyne CombiFlash NextGen 300+ automated flash purification system with various RediSep Rf normal phase silica gel cartridges with Fluka silica gel 60 (mesh 220–400), unless otherwise noted. The solvents used were CHCl3 and CMA (CHCl3 : MeOH : NH4OH (50 : 45 : 5)) usually using a gradient of 0 – 10% or 0 – 15% CMA / CHCl3, or hexane and ethyl acetate at various gradients. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Gemini spectrometer at 400 and 101 MHz, respectively, in CDCl3, MeOD-d4, or DMSO-d6. Chemical shifts were reported in ppm (TMS as the internal standard). Multiplicities are indicated by s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q= quartet, dd = doublet of doublet, dt = doublet of triplet, dq =doublet of quartet, m = multiplet resonance. Coupling constants “J” were reported in Hz. High resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were recorded on a Waters (Mitford, MA, USA) Xevo G2-XS QTof mass spectrometer. Ions were produced using positive ion electrospray (ESI) at a capillary voltage of 2.8KV. The ESI source temperature was 280 °C. Melting points were determined on a Mettler Toledo MP70 and are uncorrected. The optical rotation data were obtained on a Rudolph Research Analytical Autopol V Plus automatic polarimeter. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) analyses were carried out on Analtech silica gel GHLF 0.25 mm plates using various gradients of CHCl3/MeOH containing 1% NH4OH or gradients of EtOAc/n-hexane. Visualization was accomplished under UV light or by staining in an iodine chamber. Robertson Microlit Laboratories, Ledgewood, NJ, USA, performed elemental analyses, and the results were within ±0.4% of the theoretical values.

3-((1R,5S,9R)-2-Phenethyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-5-yl)phenyl trifluoromethanesulfonate (2):

3-((1R,5S,9R)-2-Phenethyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-5-yl)phenol8 (320 mg, 921 μmol) was dissolved in anhydrous dichloromethane (8.8 mL). To this solution triethylamine (112 mg, 1.11 mmol) and phenyl triflimide (428 mg, 1.20 mmol) was added. The reaction was stirred under nitrogen at 25 °C for 16 h. The reaction was then diluted with water and extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layer was subsequently washed with saturated sodium bicarbonate followed by brine. The organic layer was dried with sodium sulfate and evaporated to dryness. Purification via flash chromatography on silica gel with (0–50% ethyl acetate in hexanes) gave the triflate as a pale yellow oil (429 mg, 97.1 %). 1H-NMR of free base (400 MHz; CDCl3): δ 7.48–7.42 (m, 2H), 7.35–7.32 (m, 2H), 7.28–7.26 (m, 3H), 7.22 (s, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 5.55 (ddd, J = 17.4, 10.1, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 5.20 (dd, J = 41.5, 13.8 Hz, 2H), 6.64–3.70 (m, 2H), 3.56–3.41 (m, 2H), 3.38–3.27 (m, 2H), 3.23–3.14 (m, 2H), 2.56–2.47 (m, 1H), 2.22 (s, 2H), 2.09–1.96 (m, 5H).13C NMR (101 MHz; CDCl3): δ 149.7, 148.9, 135.4, 132.3, 130.5, 129.1, 128.7, 127.5, 126.1, 125.1 (1J, q= 320 Hz), 121.6, 119.6, 118.9, 60.1, 56.6, 50.3, 46.0, 37.5, 37.0, 30.8, 28.1, 20.2, 17.3. HRMS-ESI (m/z): [M + H+] calcd for: C25H29NO3 480.1820; found 480.1817. [α]20D +10.8° (c 0.780, CHCl3) of free base.

N-(3-((1R,5S,9R)-2-Phenethyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-5-yl)phenyl)acetamide (3):

3-((1R,5S,9R)-2-Phenethyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-5-yl)phenyl trifluoromethanesulfonate (200 mg, 417 μmol), acetamide (148 mg, 2.50 mmol) and potassium phosphate (266 mg, 1.25 mmol) were added to a two-neck flask. A reflux condenser was attached to the reaction vessel. For 15 min, this was flushed with argon. tBuBrettPhos Pd G3 (53.5 mg, 62.6 μmol) was added and flushed for an additional 15 min with argon. Degassed tert-butanol (3.241 mL) and water (0.16 mL) was transferred using a cannula. This was subsequently heated to 90 °C for 5 h after which the reaction was cooled to room temperature and filtered through a thin layer of celite using chloroform. The reaction mixture was concentrated, diluted with water and made basic using ammonium hydroxide and extracted with 9:1 CHCl3:MeOH. The organic layer was dried with sodium sulfate, evaporated to dryness and purified via flash chromatography on silica gel with (0–25% CMA in chloroform) gave the acetamide (68.5 mg, 42.3%) as a colorless oil. Addition of methanol and (l)-tartaric acid (1 M in methanol, 1.1 eq) gave the tartrate salt, mp: 119–122 °C. 1H-NMR of free base (400 MHz; CDCl3): δ 7.51–7.38 (m, 3H), 7.32–7.28 (m, 2H), 7.23–7.19 (m, 3H), 7.13 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 5.72 (dt, J = 17.4, 8.9 Hz, 1H), 5.00 (dd, J = 27.0, 13.8 Hz, 2H), 3.11–3.04 (m, 4H), 2.88–2.82 (m, 4H), 2.15–2.08 (m, 6H), 2.00–1.90 (m, 2H), 1.80 (d, J = 13.3 Hz, 2H), 1.62–1.54 (m, 1H).13C-NMR (101 MHz; CDCl3): δ 168.3, 150.6, 140.5, 138.1, 137.7, 128.7, 128.5, 128.4, 126.0, 122.0, 117.7, 117.3, 117.1, 58.4, 57.8, 49.7, 49.2, 41.1, 38.0, 34.5, 29.6, 24.6, 22.0, 19.4. HRMS-ESI (m/z): [M + H+] calcd for: C26H33N2O 389.2593; found 389.2592; Anal. Calcd. For C17H24NO2·2 H2O: C, 62.7%; H, 7.37%; N, 4.87%. Found C, 63.02%; H, 7.46%; N, 4.62%. [α]20D +5.7° (c 0.670, MeOH) of salt.

3-((1R,5S,9R)-2-Phenethyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-5-yl)benzonitrile (4):

In a one-neck round-bottom, 3-((1R,5R,9R)-2-phenethyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-5-yl)phenyl trifluoromethanesulfonate (590 mg, 1.23 mmol), tBuXPhos Pd G3 (79.7 mg,. 98.4 μmol), and zinc cyanide (144 mg, 1.23 mmol) were combined, placed under high vacuum and backfilled with argon 3 times. THF (1.35 mL) and degassed Water (6.5 mL) were added via syringe. The formed bilayer reaction was stirred rapidly to combine the two layers. Temperature was subsequently increased to 60 °C for 4 h. This was then worked up with water and dichloromethane. The organic layer was washed with brine, dried with sodium sulfate, evaporated to dryness and purified via flash chromatography on silica gel with (0–100% ethyl acetate in hexanes) to give the nitrile (196 mg, 44.7 %). Crystalized as the oxalate salt using acetone, mp: 185–186 °C. 1H-NMR of free base (400 MHz; CDCl3): δ 7.64–7.60 (m, 2H), 7.43–7.42 (m, 1H), 7.38–7.34 (m, 1H), 7.31–7.18 (m, 5H), 5.69 (ddd, J = 17.5, 10.0, 7.9 Hz, 1H), 5.04–4.96 (m, 2H), 3.10–3.00 (m, 4H), 2.88–2.78 (m, 4H), 2.11–2.02 (m, 3H), 2.00–1.91 (m, 2H), 1.85–1.77 (m, 2H), 1.61–1.51 (m, 1H). 13C-NMR (101 MHz; CDCl3): δ 151.0 140.3, 137.2, 130.7, 129.8, 129.3, 128.8, 128.7, 128.4, 126.1, 119.3, 117.9, 112.1, 58.3, 57.7, 49.5, 49.4, 41.0, 38.3, 34.5, 29.4, 21.8, 19.2. HRMS-ESI (m/z): [M + H+] calcd for: C25H29N2 357.2331; found 357.2325.

3-((1R,5S,9R)-2-Phenethyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-5-yl)benzamide (5):

In a three-neck round bottom equipped with a thermometer, 3-((1R,5R,9R)-2-phenethyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-5-yl)benzonitrile (200 mg, 561 μmol) and potassium carbonate (61.2 mg, 443 μmol) was dissolved in DMSO (3 mL). Hydrogen peroxide (98.5 μL, 30% Wt, 965 μmol) was added slowly so that the temperature never rose above 25 °C and allowed to react for an hour. After 1 h, this mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (5×50 mL) and water, the organic layer was washed with brine, evaporated to dryness and purified via flash chromatography on silica gel (0–25% CMA in chloroform) to give the amide (143.5 mg, 68.3 %) as an amorphous white solid. Addition of acetone and oxalic acid (1.1 equiv) gave the oxalate salt, mp: 137–140 °C. 1H-NMR of oxalate (400 MHz; MeOD-d4): δ 7.92 (s, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.32–7.22 (m, 5H), 5.68 (ddd, J = 17.4, 10.0, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 5.11 (dd, J = 40.2, 13.8 Hz, 2H), 3.78 (s, 1H), 3.72–3.62 (m, 2H), 3.52–3.46 (m, 3H), 3.18–3.07 (m, 2H), 2.45–2.36 (m, 1H), 2.30–2.23 (m, 2H), 2.19–2.11 (m, 2H), 2.04–1.96 (m, 3H).13C-NMR (101 MHz; MeOD-d4): δ 172.3, 166.8, 148.7, 138.0, 135.5, 134.9, 130.8, 129.94, 129.90, 129.7, 128.2, 126.7, 126.4, 120.6, 62.1, 57.2, 50.5, 47.7, 38.8, 38.3, 31.8, 29.3, 20.9, 18.4. HRMS-ESI (m/z): [M + H+] calcd for: C25H31N2O 375.2436; found 375.2438; Anal. Calcd. For C27H32N2O5·0.6 H2O: C, 68.22%; H, 7.04%; N, 5.89%. Found C, 68.38%; H, 7.21%; N, 5.65%. [α]20D +32.9° (c 0.350, CHCl3) of free base.

(1R,5S,Z)-9-(Methoxymethylene)-5-(3-methoxyphenyl)-2-methyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (6):

(1S,5S)-5-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-2-methyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-9-one38 and (methoxymethyl)triphenylphosphonium chloride were placed separately under high vacuum overnight in a 250 mL round bottom flask equipped with a stir bar (1S,5S)-5-(3-methoxyphenyl)-2-methyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-9-one (16.39 mmol) and (methoxymethyl)triphenylphosphonium chloride (49.16 mmol) were combined and the flask was backfilled with argon 3 times. The flask was cooled in an ice bath and lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide was added (65.55 mmol, 1M in THF). This was left in the ice bath for 15 min after addition and then allowed to warm to room temperature for 5 h. The reaction reached completion (verified by TLC), cooled in an ice bath, after which methanol was added to quench the reaction. The solvent was removed via rotary evaporator, and the residue extracted with chloroform, washed with water and brine, dried with sodium sulfate and concentrated. This gave both E:Z isomers which were separated and purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (2% – 20% CMA in CHCl3) to give a reddish oil (1.98 g, 42% yield). 1H-NMR of free base (400 MHz; CDCl3): δ 7.26–7.22 (m, 1H), 7.03–6.98 (m, 2H), 6.76 (dd, J = 8.1, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 5.21 (s, 1H), 3.87 (t, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 3.81 (s, 3H), 3.40 (s, 3H), 3.12–3.06 (m, 1H), 2.75 (dt, J = 11.7, 5.8 Hz, 1H), 2.47 (s, 3H), 2.42–2.34 (m, 1H), 2.12–2.02 (m, 3H), 1.99–1.88 (m, 2H), 1.76–1.69 (m, 1H), 1.50–1.41 (m, 1H).13C-NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 159.11, 149.21, 141.07, 128.56, 123.47, 119.89, 113.65, 110.69, 59.36, 55.16, 53.64, 50.57, 43.73, 40.19, 38.98, 38.44, 27.55, 21.36. HRMS-ESI (m/z): [M + H+] calcd for: C18H26NO2 288.1964; found 288.1960. [α]20D +61.8° (c 0.710, CHCl3) of free base.

(1R,5S,E)-9-(Methoxymethylene)-5-(3-methoxyphenyl)-2-methyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (6):

(1S,5S)-5-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-2-methyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-9-one38 and (methoxymethyl)triphenylphosphonium chloride were placed separately under high vacuum overnight in a 250 mL round bottom flask equipped with a stir bar (1S,5S)-5-(3-methoxyphenyl)-2-methyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-9-one (16.39 mmol) and (methoxymethyl)triphenylphosphonium chloride (49.16 mmol) were combined and the flask was backfilled with argon 3 times. The flask was cooled in an ice bath and lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide was added (65.55 mmol, 1M in THF). This was left in the ice bath for 15 mins after addition and then allowed to warm to room temperature for 5 h. The reaction reached completion (verified by TLC), cooled in an ice bath, after which methanol was added to quench the reaction. The solvent was removed via rotary evaporator, and the residue extracted with chloroform, washed with water and brine, dried with sodium sulfate and concentrated. This gave both E:Z isomers which were separated and purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (2% – 20% CMA in CHCl3) to give a orange oil (2.75 g, 58.4% yield). 1H-NMR of free base (400 MHz; CDCl3): δ 7.17 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.02–6.97 (m, 2H), 6.71 (dd, J = 8.1, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 5.87 (s, 1H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 3.15–3.09 (m, 4H), 3.04–3.03 (m, 1H), 2.80 (dt, J = 11.6, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 2.48 (s, 3H), 2.42–2.34 (m, 1H), 2.24–2.03 (m, 4H), 1.88 (dt, J = 13.9, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 1.79–1.76 (m, 1H), 1.55–1.46 (m, 1H). 13C-NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.70, 151.32, 139.69, 139.66, 127.64, 119.28, 113.11, 110.32, 62.03, 58.96, 55.14, 50.80, 43.55, 40.79, 39.04, 37.81, 29.50, 21.59. HRMS-ESI (m/z): [M + H+] calcd for: C18H26NO2 288.1964; found 288.1960. [α]20D −19.5° (c 1.050, CHCl3) of free base.

(1R,5S,9S)-5-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-2-methyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (8):

(1R,5R,E&Z)-9-(Methoxymethylene)-5-(3-methoxyphenyl)-2-methyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (1.3 g, 4.523 mmol) was suspended in THF (11 mL) and treated with HCl (6M) (48 mL) and the reaction mixture was stirred at 55 °C for 2 h. The reaction mixture was quenched with 7N NH4OH in water to pH 9 under ice extracted with CHCl3 and washed with brine. The organic layer was then dried with sodium sulfate, concentrated and placed under high vacuum for 1 h. Methyltriphenylphosphonium bromide (4.848 g, 13.57 mmol) and potassium 2-methylpropan-2-olate (2.030 g, 18.09 mmol) were added to an oven-dried round-bottom flask purged with argon. The phosphonium salt was dried under high vacuum at 100 °C for 4 h while potassium tert-butoxide was dried a 60 °C for 24 h prior to their use. THF (12 mL) was added, and the reaction mixture was heated to 55 °C for 1 h to allow for ylide formation. The aldehyde mixture was added in THF (12 mL) and the reaction mixture was stirred at 55 °C for 4 h and then room temp for 14 h. The reaction mixture was quenched under ice with methanol, evaporated to dryness, diluted with water and extracted with chloroform. The product was purified via flash chromatography on silica gel (0–10% CMA in chloroform) to give both epimers separated as a blueish-green oil (159 mg, 13%). 1H-NMR of salt (400 MHz; MeOD-d4): δ 7.22 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.84 (s, 1H), 6.75 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 5.70 (ddd, J = 17.3, 10.4, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 5.36–5.24 (m, 2H), 3.75 (s, 3H), 3.72–3.71 (m, 1H), 3.69–3.63 (m, 1H), 3.51–3.44 (m, 1H), 3.29–3.29 (m, 1H), 2.93 (s, 3H), 2.47–2.35 (m, 3H), 2.17–2.03 (m, 2H), 2.00–1.89 (m, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 1.87–1.79 (m, 1H). 13C-NMR (101 MHz, MeOD-d4): δ 159.8, 148.3, 134.7, 129.0, 119.6, 117.6, 111.9, 110.74, 62.5, 54.2, 50.8, 46.3, 40.7, 40.3, 36.3, 27.8, 22.7, 20.5. Addition of isopropanol and HCl (1.1 eq) gave the hydrochloride salt, MP: 267.8–270.7 °C. HRMS-ESI (m/z): [M + H+] calcd for: C18H26NO 272.2014; found 272.2013. [α]20D −28.8° (c 1.140, MeOH) of HCl salt.

(1R,5S,9R)-5-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-2-methyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (9):

(1R,5R,E&Z)-9-(Methoxymethylene)-5-(3-methoxyphenyl)-2-methyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (1.3 g, 4.523 mmol) was suspended in THF (11 mL) and treated with HCl (6M) (48 mL) and the reaction mixture was stirred at 55 °C for 2 h. The reaction mixture was quenched with 7N NH3OH in water to pH 9 under ice extracted with CHCl3 and washed with brine. The organic layer was then dried with sodium sulfate, concentrated and put under high vacuum for 1 h. Methyltriphenylphosphonium bromide (4.848 g, 13.57 mmol) and potassium 2-methylpropan-2-olate (2.030 g, 18.09 mmol) were added to an oven-dried round bottom flask purged with argon. The phosphonium salt was dried under high vacuum at 100 °C for 4 h while potassium tert-butoxide was dried a 60 °C for 24 h prior to this. THF (12 mL) was added, and the reaction mixture was heated to 55 °C for 1 h to enable ylide formation as a yellow solution. The aldehyde mixture was added in THF (12 mL) and the reaction mixture was stirred at 55 °C for 4 h and then room temperature for 14 h. The reaction mixture was quenched under ice with methanol, evaporate to dryness, diluted with water and extracted with chloroform. Purified via flash chromatography on silica gel (0–10% CMA in chloroform) to give both epimers separated as a blueish-green oil (581 mg, 47.3%).1H-NMR of free base (400 MHz; CDCl3): δ 7.21 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.93–6.92 (m, 1H), 6.70 (dd, J = 8.1, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 5.75 (ddd, J = 17.5, 10.2, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 5.06–4.97 (m, 2H), 3.78 (s, 3H), 3.11–3.03 (m, 2H), 2.90–2.82 (m, 2H), 2.51 (s, 3H), 2.19–2.08 (m, 3H), 2.02–1.88 (m, 2H), 1.84–1.76 (m, 2H), 1.60–1.50 (m, 1H).13C NMR (101 MHz; CDCl3): δ 159.3, 151.3, 138.2, 128.8, 118.4, 116.8, 112.3, 110.5, 60.1, 55.0, 51.4, 49.9, 43.0, 41.4, 37.6, 29.6, 22.2, 18.5. HRMS-ESI (m/z): [M + H+] calcd for: C18H26NO 272.2014; found 272.2011. Addition of isopropanol and HCl (1.1 equiv) gave the hydrochloride salt, mp: 206.2–208.8 °C. [α]20D +8.9° (c 1.090, MeOH) of HCl salt.

3-((1R,5S,9S)-2-Methyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-5-yl)phenol (10):

In an oven-dried round-bottom flask, (1R,5S,9S)-5-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-2-methyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (145 mg, 534 μmol) was suspended in dichloromethane (5.4 mL) and the mixture was cooled to −78 °C. Boron tribromide (268 mg, 1.07 mmol) was added dropwise and the reaction was stirred at −78 °C for 15 mins. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 1 h. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C, quenched with MeOH and stirred for an additional 30 min. The reaction mixture was subsequently concentrated with a rotary evaporator, taken up in ethanol (1.8 mL) and 2N HCl (1.8 mL) and refluxed for 1h. This was then allowed to warm to room temperature and made basic to pH 9 using 4N NH4OH. The mixture was extracted using chloroform and purified on silica gel (0–10% CMA in chloroform) to obtain a blue oil. Subsequent purification via flash chromatography with an alumina column (10% - 100% EtOAc in hexanes) gets rid of remaining impurities, to give a pale-yellow oil (76 mg, 55%). Addition of isopropanol and HCl (1.1 eq) gave the hydrochloride salt, mp: 2897.7–292.3 °C. 1H-NMR of HCl salt (400 MHz; MeOD-d4): δ 7.12 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.79 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.74–6.74 (m, 1H), 6.64–6.61 (m, 1H), 5.71 (ddd, J = 17.4, 10.6, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 5.32 (dd, J = 26.7, 14.0 Hz, 2H), 3.74–3.65 (m, 2H), 3.51–3.46 (m, 1H), 3.28 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 2.94 (s, 3H), 2.47–2.34 (m, 3H), 2.18–1.81 (m, 5H).13C NMR (101 MHz; MeOD-d4): δ 157.2, 148.2, 134.7, 129.0, 119.5, 116.3, 112.8, 112.4, 62.5, 50.8, 46.2, 40.7, 40.3, 36.2, 27.8, 22.7, 20.4. HRMS-ESI (m/z): [M + H+] calcd for: C17H24NO 258.1858; found 258.1854; Anal. Calcd. For C17H24ClNO·0.15 H2O: C, 68.86%; H, 8.26%; N, 4.72%. Found C, 68.68%; H, 7.88%; N, 4.52%. [α]20D −22.6° (c 0.680, MeOH) of HCl salt.

3-((1R,5S,9R)-2-Methyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-5-yl)phenol (11):

In an oven-dried round-bottom flask, (1R,5S,9R)-5-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-2-methyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (420 mg, 1.55 mmol) was suspended in dichloromethane (15 mL) and the mixture was cooled to −78 °C. Boron tribromide (1.16 g, 4.64 mmol) was added dropwise and the reaction was stirred at −78 °C for 15 mins. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred overnight (16 h). Upon completion, the reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C and quenched with MeOH and stirred for 30 min. Reaction mixture was concentrated using a rotary evaporator, taken up in ethanol (5 mL) and 2N HCl (5 mL) and refluxed for 2 h. The mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and made basic to pH 9 using 4N NH4OH in water. The basic solution was extracted using chloroform and purified on silica gel via flash chromatography on silica gel (0–10% CMA in chloroform) to give a blue oil. Subsequent purification via flash chromatography with an alumina column (10% - 100% EtOAc in hexanes) removes the of remaining impurities to give a pale-greenish oil (102 mg, 25.6 %). Addition of isopropanol and HCl (1.1 eq) gave the hydrochloride salt, mp: 266.4–267.7 °C. 1H-NMR of HCl salt (400 MHz; MeOD-d4): δ 7.07 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.84–6.80 (m, 2H), 6.57–6.54 (m, 1H), 5.77 (ddd, J = 17.5, 10.3, 7.5 Hz, 1H), 5.04–4.96 (m, 2H), 3.10 (dt, J = 12.6, 6.3 Hz, 1H), 3.03 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 2.88–2.87 (m, 1H), 2.81 (dd, J = 12.2, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.48 (s, 3H), 2.16–1.93 (m, 5H), 1.84–1.74 (m, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 1.69–1.62 (m, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H).13C-NMR (101 MHz; MeOD-d4): δ 156.8, 150.6, 137.9, 128.5, 116.8, 115.9, 112.7, 112.1, 60.1, 50.9, 49.0, 41.7, 40.7, 37.0, 29.1, 21.6, 17.8. HRMS-ESI (m/z): [M + H+] calcd for: C17H24NO 258.1858; found 258.1855; Anal. Calcd. For C17H24ClNO·0.1 H2O: C, 69.07%; H, 8.25%; N, 4.74%. Found C, 69.29%; H, 8.41%; N, 4.74%. [α]20D +8.4° (c 0.730, MeOH) of HCl salt.

(1S,5S,9R)-5-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (12):

In a two-neck 250-mL round bottom flask equipped with a stir bar, the oil (1R,5R,9R)-5-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-2-methyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (0.830 g, 3.06 mmol) and sodium bicarbonate (5.14 g, 61.2 mmol) were added. This was then dissolved in 1,2-dichloroethane (16.6 mL). The reaction mixture was allowed to cool, then 1-chloroethyl chloroformate (2.19 g, 1.67 mL, 15.3 mmol) was added and stirred at 0 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, this was refluxed 83 °C for 2 hours. This was then allowed to cool to room temperature, filtered through a fritted funnel and washed with chloroform. This was subsequently evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure and then redissolved in methanol (16.6 mL). This was refluxed at 66 °C for 1 hour. Once it cooled to room temperature, it was evaporated to dryness on the rotary evaporator the mixture was dissolved in 2N KOH and extracted with 9:1 CHCl3:MeOH (4×50 mL). Once this was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure, it gave a reddish oil. 1H-NMR of free base (400 MHz; CDCl3): δ 7.12 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.79 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.74–6.74 (m, 1H), 6.64–6.61 (m, 1H), 5.71 (ddd, J = 17.4, 10.6, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 5.32 (dd, J = 26.7, 14.0 Hz, 2H), 3.74–3.65 (m, 2H), 3.49 (dd, J = 13.5, 6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.28 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 2.94 (s, 3H), 2.47–2.34 (m, 3H), 2.18–1.81 (m, 5H).13C-NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 159.35, 151.33, 137.89, 128.89, 118.29, 116.92, 112.45, 110.26, 55.08, 53.56, 49.35, 42.47, 41.61, 38.26, 29.45, 25.93, 21.74. HRMS-ESI (m/z): [M + H+] calcd for C17H24NO 258.1858; found 258.1855. [α]20D 19.7° (0.320, CHCl3) of free base.

tert-Butyl (1R,5S,9R)-5-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane-2-carboxylate (13):

In a two-neck 25-mL round bottom flask equipped with a stir bar and reflux condenser, the oil (1R,5R,9R)-5-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-2-methyl-9-vinyl-2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (1.127 g, 1 equiv, 4.153 mmol) and sodium bicarbonate (6.977 g, 20 equiv, 83.05 mmol) were added. This was then dissolved in 1,2-Dichloroethane (22 mL). Under ice, 1-chloroethyl chloroformate (2.968 g, 2.266 mL, 5 equiv, 20.76 mmol) was added and stirred at 0 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, this was refluxed at 83 °C for 2 hours, after completion, as observed on TLC. The reaction mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature and then filtered through a fritted funnel and the sodium bicarbonate was washed with chloroform. This was then evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure and then dissolved in methanol (22 mL). This was refluxed at 66 °C for 1 hour, upon completion oas observed n TLC. The solvent was evaporated, acetone was added, and the white solid was filtered on a Büchner funnel. The solid was subsequently free-based with 2N KOH and 9:1 CHCl3:MeOH, the organic layers were dried on the rotary evaporator. The oil was placed on high vacuum for 5 hours in a 25 mL round bottom flask. To the flask DMAP (0.1 eq), Boc-anhydride (3 eq) was added and dissolved in dichloromethane (6 mL). Triethylamine (5 eq) was added slowly and allowed to react overnight. After 17 hours, the reaction was diluted with a saturated solution of sodium bicarbonate and extracted with chloroform (3×50 mL). The organic layers were dried with sodium sulfate, evaporated to dryness on rotary evaporator and purified via silica gel (0% – 5% CMA in CHCl3) to give a pale-yellow oil (772.5 mg, 77.2%). δ 7.22 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.92–6.85 (m, 2H), 6.72–6.70 (m, 1H), 5.71–5.60 (m, 1H), 5.02 (dd, J = 23.8, 13.6 Hz, 2H), 4.31–4.10 (m, 1H), 3.79–3.72 (m, 5H), 2.99–2.94 (m, 1H), 2.06–1.86 (m, 5H), 1.76–1.72 (m, 3H), 1.49 (s, 9H).13C-NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 159.4, 155.5, 151.6, 136.9, 129.0, 118.3, 117.6, 112.5, 110.1, 79.4, 55.1, 53.4, 47.4, 41.4, 39.5, 37.4, 29.9, 28.5, 24.3, 19.5. HRMS-ESI (m/z): [M + H+] calcd for: C22H32NO3 358.2382; found 358.2376. [α]20D −6.0° (c 5.750, CHCl3) of free base.

Protocol A: