Abstract

The progressive aggregation of misfolded proteins is the underlying molecular cause of numerous pathologies including Parkinson’s disease and injection and transthyretin amyloidosis. A growing body of evidence indicates that protein deposits detected in organs and tissues of patients diagnosed with such pathologies contain fragments of lipid membranes. In vitro experiments also showed that lipid membranes could strongly change the aggregation rate of amyloidogenic proteins, as well as alter the secondary structure and toxicity of oligomers and fibrils formed in their presence. In this review, the effect of large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) composed of zwitterionic and anionic phospholipids on the aggregation rate of insulin, lysozyme, transthyretin (TTR) and α- synuclein (α-syn) will be discussed. The manuscript will also critically review the most recent findings on the lipid-induced changes in the secondary structure of protein oligomers and fibrils, as well as reveal the extent to which lipids could alter the toxicity of protein aggregates formed in their presence.

Keywords: Amyloid fibrils, LUVs, Oligomers, Toxicity, Neurodegeneration

1. Introduction

Misfolded proteins can minimize their free energies by adopting stable β-sheet-rich structures, also known as ‘dry zippers’ [1,2]. A progressive self-assembly of such β-sheet-rich specimens leads to the formation of highly toxic oligomers, transient species that can later propagate into amyloid fibrils, Fig. 1 [3–6]. Although the structural organization of amyloid oligomers remains unclear, Zhaliazka and Kurouski recently were able to resolve the secondary structure of amyloid β1–42 (Aβ1–42) oligomers formed at different stages of protein aggregation [7]. Similar results were previously reported by the Cullen research groups [8,9]. These oligomers together with Aβ1–42 fibrils are the major constituents of amyloid plaques observed in the frontal cortex of patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Using nano-Infrared spectroscopy, Zhaliazka and Kurouski showed that Aβ1–42 first formed oligomers with parallel β-sheet secondary structure [7]. These oligomers exhibited much slower rates of propagation into fibrils compared to the oligomers with anti-parallel β-sheet. These anti-parallel β-sheet-rich oligomers formed at much later stages of protein aggregation. However, once formed, they rapidly propagated into proto-filaments and fibrils. By 72 h after the initiation of Aβ1–42 aggregation, a steady-state equilibrium between the aggregates with parallel and antiparallel β-sheet secondary structures was observed. Next, Aβ1–42 aggregates with antiparallel β-sheet remained as a subpopulation during the late stages of protein aggregation, while the oligomers and fibrils with parallel β-sheets were dominant. Similar results were reported by Ghosh group for Dutch mutant of Aβ1–42 [10].

Fig. 1.

A schematic diagram of α-Syn aggregation. Monomeric α-Syn aggregates into various small oligomers that have different structures and morphologies. Some of these oligomers further propagate into proto-fibrils and fibrils.

Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (ss-NMR) and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) are highly powerful tools for elucidation of the secondary structure of amyloid fibrils [11,12]. Both techniques helped discover that amyloid fibrils were composed of filaments that contained two β-sheets with ~4.7 Å inter-strand distances spaced ~10 Å between each other [12–15]. Some of these filaments had three β-sheets arranged into a triangle [11,16]. The filaments were able to braid and coil or connect side-by-side, associated into proto-fibrils [17,18]. Finally, several proto-fibrils formed a mature fibril. Different ways of filament self-assembly result in a large variety of fibril morphologies, a phenomenon known as fibril polymorphism [19]. It should be noted that fibril polymorphism can originate from differences in the arrangement or packing of ‘dry zippers’ in the fibril filament [12–15].

Microscopic analysis of amyloid plaques, intracellular deposits formed in the human brain upon AD, revealed that Aβ1–42 fibrils were present together with fragments of lipid-rich membranes, organelles, and vesicles [20]. In vitro experiments performed by Zhaliazka and co-workers showed that large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) composed of phosphatidylcholine (PC), cardiolipin (CL) and cholesterol drastically accelerated the rate of Aβ1–42 aggregation [21]. Furthermore, it was shown that changes in the rate of protein aggregation, as well as the secondary structure and toxicity of such oligomers and fibrils directly depended on the chemical structure of the lipid that was present at the stage of Aβ1–42 aggregation [21]. Similar findings were reported by Lyubchenko group [22,23]. Specifically, Banerjee and co-workers found that the presence of 20% cholesterol in the mixture of POPC-POPS drastically enhanced the rate of Aβ1–42 aggregation [22]. Furthermore, it was found that Aβ1–42 oligomers caused no damage to the lipid bilayers. Using molecular simulations, Yu and Zheng showed that an increase in the concentration of cholesterol in POPC-based membranes changes the structure and dynamics of the lipid bilayer [24]. As a result, an increase in the bilayer thickness, hydrophobic chain order, and surface hydrophobicity was observed.

At the same time, Vestergaard reported the absence of significant changes in the rate of Aβ1–42 aggregation in the presence of POPC and 50:50% POPC:cholesterol compared to the rate of Aβ1–42 aggregation in the lipid-free environment [25]. However, substantial changes in the morphologies of amyloid fibrils formed under these experimental conditions (100% POPC and 50:50% POPC:cholesterol) were observed. Comparatively, recently reported results by the Vendruscolo group showed that an increase in the concentration of cholesterol in DMPC vesicles (from 0 to 15%) caused a significant increase in the rate of Aβ1–42 aggregation [26]. The researchers observed no differences in the length and height of the fibrils formed under these conditions, nor in the secondary structure of these fibrils. The researchers concluded that the presence of cholesterol in DMPC vehicles facilitates an alternative route for Aβ1–42 primary nucleation. These findings are in a good agreement with the results reported for Aβ1–42 by the Cullen group [27]. For more detailed information about the role of cholesterol in amyloid pathologies the reader is advised to read an excellent review by Rudaev and Novotny [28].

NMR results reported by Coles and co-workers showed that micelles and pH strongly alter the secondary structure of Aβ1–40 peptide [29]. Expanding upon this, Serra-Batiste and co-workers found that in the presence of micelles, Aβ1–40 aggregated into amyloid fibrils, whereas Aβ1–42 formed oligomers that could be inserted into lipid bilayers [30]. NMR revealed that these oligomers had a β-barrel structure that was stabilized by aliphatic tails of lipids [30]. Using a set of biophysical methods, Ramamoorthy group showed insertion of such pore-like oligomers in the lipid bilayers has to be followed by a propagation of these oligomers into fibrils to cause membrane fragmentation that ultimately leads to the cell death [31–33]. Finally, used NMR, Lindström and co-workers demonstrated that electrostatic interactions were dominated between Aβ1–40 peptide and lipid vesicles composed of a negatively charged dimyristoylphosphatidylglycerol (DMPG) and zwitterionic DMPC mixed at 1:4 M ratios [34]. It was also found that the presence of anionic lipids was critically important for Aβ1–40-membrane binding [34].

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a severe pathology that is linked to the progressive aggregation of α-synuclein (α-syn) [35–37], a small protein that regulates cell vesicle trafficking [36,38–43]. α-Syn oligomers and fibrils are found in Lewy bodies (LBs), intracellular formations observed in neurons located in several areas of the midbrain, hypothalamus, and thalamus [44,45]. A growing body of evidence indicates that α-syn aggregates can spread from cell to cell causing a sequential loss of neurons in other regions of the brain, which progresses along the caudo-rostral axis [35–37].

Microscopic analysis of LBs also revealed the presence of fragments of lipid-rich membranes, organelles, and vesicles [46,47]. Our group further demonstrated that lipids were also present in the structure of ex vivo extracted α-syn fibrils [48]. This and other pieces of evidence strongly suggest that lipid membranes can be directly involved in the formation of toxic α-syn oligomers and fibrils [49–53]. More on this, Galvagnion and co-workers found that anionic phosphatidylserine (DMPS) could alter the rate of α-syn aggregation, directly dependent on the protein-to-lipid ratio (P:L) [53], Fig. 2, A. With an increase in the concentration of lipid relative to the concentration of α-syn, an increase in the rate of protein aggregation was observed. However, a subsequent increase in the concentration of lipid vesicles decreased the rate of protein aggregation. It was proposed that a small number of LUVs facilitated protein interactions that were taking place on their surfaces, Fig. 2, B. As predicted, with a further increase in the concentration of LUVs, lipid surfaces were spacing out α-syn molecules, thus, minimizing chances of protein-protein interactions. It was also shown that oligomers and fibrils formed by α-syn at different P:L ratios exert different cytotoxicity, Fig. 2, C.

Fig. 2.

Role of lipids in aggregation of α-syn. (A) Variation in the maximum rate of aggregation of α-syn with changes in the DMPS/α-syn ratio; (B) LUV-based templating of α-syn aggregation. (C) Results of calcein release assay from LUVs of different POPS:POPC ratios after being incubated with monomeric (red bars), oligomeric (blue bars), and fibrillar (black bars) αS, at two different P:L ratios (1:10 and 1:100). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Galvagnion and co-workers also showed that the presence of DMPS and 1,2-dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (DLPS) vesicles altered the morphology of α-syn fibrils formed in their presence [54] These findings are in good agreement with results reported by Meade and co-workers that found a large number of fibrillar forms and shapes formed by α-syn in the presence of lipid vesicles [55].

Using fluorescence imaging, Hannestad and co-workers demonstrated that α-syn not only aggregates on the surfaces of LUVs, but strongly perturbed lipid vesicles in a stepwise and lipid-dependent fashion [56]. Numerous studies reported by Claessens group indicated that such interactions were directly controlled by the charge and the size of lipid vesicles [57–63]. Lee group discovered that α-syn could re-shape lipid bilayers [64], Fig. 3. Specifically, it was found that the addition of α-syn to SUVs composed of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) (POPG) caused rapid re-shaping of these vesicles into micellar and bilayer tubules with 7 and 30 nm diameters, respectively. Using CD spectroscopy, the researchers found that α-syn preserved its α helical conformation in bilayer tubules that were primarily observed at lipid -to-protein (L/P) ratio of 50. At the same time, micellar tubules observed at L/P = 1 were transformed into β-sheet-rich fibrils at later time points of protein aggregation [64]. Similar remodeling effect was also observed by Lee group for zwitterionic LUVs [65].

Fig. 3.

α-Syn remodeling of POPG SUVs and effect on amyloid formation. TEM images of POPG vesicles alone (A), α-syn + POPG SUVs at L/P = 1 (B) and L/P = 50 (C) before (T0) agitation and fibrils formed by α-syn alone (D) and by α-syn + POPG SUVs at L/P = 1 (E) and L/P = 50 (F) after (Tend) agitation (70 μM α-syn in 20 mM MOPS, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7, 37 °C). Length of scale bar is 100 nm. Far-UV CD spectra of α-syn alone (G), L/P = 1 (H), and L/P = 50 (J) at T0 (black) and Tend (red). (K) Aggregation kinetics of α-syn in the absence (red) or presence (green, L/P = 1; black, L/P = 50) of POPG SUVs monitored by ThT fluorescence.

NMR revealed that in such cases, α-syn formed strong electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions with lipids, which resulted in disruption and asymmetric deformation of lipid membranes [66,67]. Electrostatic interactions were primarily observed between the polar lipid heads and the highly charged N-terminus of α-syn. The hydrophobic interactions dominated between the central part of the protein and aliphatic tails of fatty acids (FAs) present in such lipids [68,69]. These results were confirmed by Frieg and co-workers that used cryo-EM to resolve the secondary structure of α-syn fibrils formed in the presence of lipids [70]. These researchers also found that phospholipids promoted an alternative protofilament fold, which lead to an unusual arrangement of protofilaments, and fill the central cavities of the fibrils. These findings led to two important conclusions: (i) A net charge of the lipid polar heads, as well as a chemical structure of lipid head groups should alter protein-lipid interactions. (ii) Chemical properties of FAs in lipids, such as their length and saturation may change protein-lipid interactions. In both cases, structural differences in lipid-protein complex should lead to dissimilar rates of protein aggregation, as well as a different secondary structure and toxicity of amyloid oligomers and fibrils.

Using a set of biophysical methods, our group tested this hypothesis on four different amyloidogenic proteins: insulin, lysozyme, α-syn, and transthyretin (TTR) [49,50,71–84]. To assess the effect of the net charge of the lipid head-group, we utilized anionic phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), and cardiolipin (CL), as well as zwitterionic phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). Finally, to test the effect of the length and saturation of FAs, we employed PS with 14:0 (DMPS), 18:0 (DSPS), 18:1 (DOPS) and 16:0/18:1 (POPS) Fas.

The role of the net charge of phospholipids on the rate of protein aggregation.

Using a thioflavin T (ThT) assay, Matveyenka and co-workers found that at pH 3.0, 37 °C at 510 rpm agitation, insulin aggregates within ~ 14 h [75,76], Fig. 4. However, in the presence of equimolar concentrations of anionic LUVs composed of PS, PG and CL, they saw a 2–3-fold increase in the rate of protein aggregation. Specifically, in the presence of both PG and CL, insulin aggregated within 3.8–3.9 h, whereas in the presence of PS LUVs, insulin aggregated within 8.5 h, Fig. 2 [75,76]. On the other hand, zwitterionic PC and PE fully inhibited insulin aggregation. Similar conclusions were made by Zhaliazka and co-workers for lysozyme [82]. The researchers found that PC and PE inhibited lysozyme aggregation at pH 3.0, 65 °C, whereas CL, PS and PG drastically accelerated the protein aggregation. Furthermore, CL exhibited much greater acceleration of lysozyme aggregation compared to PS and PG.

Fig. 4.

Negatively charged phospholipids accelerate while zwitterionic phospholipids strongly inhibit insulin aggregation. ThT aggregation kinetics of insulin in the lipid-free environment (red), as well as in the presence of PG (blue), PS (green), CL (black), PC (purple) and PE (orange). Each kinetic curve is the average of three independent measurements. For Ins, 400 μM of bovine insulin was dissolved in 1xPBS with 2 mM of ThT; pH adjusted to pH 3.0. For Ins:PG, Ins:PS, Ins:PS and Ins:CL and Ins:PE, 400 μM of bovine insulin was mixed with an equivalent concentration of the corresponding lipid; pH was adjusted to pH 3.0. All samples were kept at 37 °C under 510 rpm for 24 h. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The reported results by Ali and co-workers showed that anionic PS strongly accelerated the rate of TTR aggregation (pH 3.0, 37 °C at 510 rpm agitation) [84], whereas PC decelerated the rate of TTR aggregation. Dou and co-workers found that PC completely inhibited the aggregation of α-syn at the equimolar P:L ratio (pH 7.4, 37 °C at 510 rpm agitation), whereas PS accelerated the rate of α-syn aggregation (tlag = 10.0 ± 0.76 h compared to tlag of 12.9 ± 0.52 h of α-syn in the lipid-free condition) [85]. These results demonstrated that zwitterionic lipids decelerated or fully inhibited protein aggregation, whereas anionic lipids accelerated the aggregation of the aforementioned amyloidogenic proteins. These findings explain the important predominance of zwitterionic lipids in plasma membranes of neurons [86]. This suggests that anionic lipids can play an important role in the onset and progression of amyloid pathologies. PS, for example, is localized on the inner surface of plasma membranes via ATP-dependent transport [87]. As a result of cell malfunction, the concentration of PS in the outer plasma membrane increases, triggering the macrophage-induced apoptosis of such cells [72,88]. One may expect that under some pathological conditions, the rate of macrophage-determined clearance of such malfunctional cells in the brain and other organs can decrease. High concentration of PS in such cells will consequently trigger the aggregation of amyloid proteins proximal to plasma membranes of such cells [77].

An intracellular rather than extracellular mechanism of α-syn aggregation was proposed by Choi and co-workers [89]. It was found that the presence of 40%–60% CL in DMPC liposomes with 1:8 P:L ratio substantially enhanced the rate of A53T α-syn aggregation. Furthermore, morphologically different fibrils were formed by A53T α-syn under these experimental conditions. These aggregates induced mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening, which resulted in mitochondrial dysfunction. Thus, Choi and co-workers demonstrated that mitochondrial membranes could trigger α-syn aggregation, which results in the formation of highly toxic protein aggregates that can spread from cell to cell causing PD [89].

Generally, it is agreed that α-syn has much stronger interactions with membranes composed of anionic rather than zwitterionic lipids. At the same time, experimental results reported by Fraser group showed that phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) enhanced protein-membrane interactions [90]. Furthermore, α-syn exhibited stronger interactions with PA and PI compared to PS and PG [90]. In addition to phospholipids, α-syn interacts with gangliosides (GMs). GMs constitute a substantial portion of neuronal membranes [91–93]. These sphingolipids have a ceramide backbone with one or more sugars as the headgroup. Using a set of biophysical methods, several groups investigated mechanisms of α-syn interactions between GM1, GM2, GM3 [91–93]. It was found that GMs interact with α-syn via hydrogen-bonding network that was taken place between the sugar alcohols and the protein side chains [92].

It should be noted that not only the net charge of phospholipids, but also the size of LUVs and L:P ratio can play an important role in protein-lipid interactions that can alter the rates of protein aggregation [94,95]. Terakawa and co-workers found that small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) enable much greater acceleration of amyloid β1–40 (Aβ1–40) aggregation compared to LUVs with the same lipid composition, Fig. 5, A-B [96]. The researchers showed that this effect originated from a greater number of defects in lipids of SUVs compared to LUVs, Fig. 5, C. Consequently, lipids in such defects can be more accessible to proteins present on the surface of such vesicles. Independently, Zhaliazka and co-workers demonstrated that PS and CL exhibited much stronger enhancement of lysozyme aggregation if were present at 1:10 and 1:5 as opposed to 1:1 P:L ratios. [83]

Fig. 5.

The effect of lipid vesicle size on the aggregation of Aβ1–40. ThT kinetics (top) of Aβ1–40 aggregation in the presence of (pink) and absence (black) of 30 nm (A) and 100 nm (B) DOPC vesicles with corresponding AFM images (bottom) of the formed fibrils; (C) Models of Aβ1–40 aggregation on the surface of defect-rich SUVs and defect-poor LUVs. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Davidson and co-workers demonstrated that α-syn exhibits higher binding efficiency towards SUVs than LUVs [97]. Several following studies that employed site-specific fluorescence, gel-filtration, and isothermal titration calorimetry confirmed these findings [57,98,99]. Using confocal microscopy, Stockl and co-workers showed that such interactions are triggered by disordered domains of lipid vesicles. [63] Alternatively, experimental evidence reported by Antonny group showed that packing defects is SUVs and LUVs are the key elements that facilitate α-syn interactions with lipids [100].

The role of the length and saturation of FAs in phospholipids on the rate of protein aggregation.

Matveyenka and co-workers found that DMPS exhibited much greater acceleration of the rate of insulin aggregation compared to DOPS (pH 3.0, 37 °C at 510 rpm agitation), whereas the presence of POPS, on the opposite, decelerated the rate of insulin aggregation [72]. It was also found that unsaturated CL (u-CL) enabled much greater acceleration of insulin aggregation compared to its fully saturated analog (s-CL) [71]. However, the difference in the saturation of PC did not change the effect of this lipid on insulin aggregation. Specifically, both saturated (s-PC) and unsaturated PC (s-PC) strongly inhibited insulin aggregation [71].

These results are consistent with the experimental results that were recently reported by Frese and co-workers [101]. Specifically, the researchers found that DMPS enabled the strongest acceleration of lysozyme aggregation at pH 3.0, 37 °C compared to DOPS and POPS, Fig. 6. Finally, the acceleration effect of DSPS was the weakest compared to DMPS, POPS, and DOPS [101]. At the same time, DMPS, DSPS, POPS, and DOPS decelerated the rate of TTR aggregation (pH 3.0, 37 °C at 510 rpm agitation) [84]. It should be noted that DOPS enabled the strongest deceleration of TTR aggregation compared to POPS, DMPS and DSPS. These results indicate that both the length of FAs and their saturation play an important role in protein aggregation. Using docking simulations, Holman and co-workers demonstrated that FAs with different length and degree of saturation had drastically different interactions with insulin [102]. One can expect that similar differences in the interactions of FAs with other proteins determined the discussed above differences in the rate of lysozyme and TTR aggregation.

Fig. 6.

Length and saturation of FAs in PS uniquely alters the rate of lysozyme aggregation. (A) ThT aggregation kinetics of insulin in the lipid-free environment (grey), and in the presence of DMPS (green), DOPS (blue), POPS (orange), and DSPS (pink). Each kinetic curve is the average of three independent measurements. (B) A histogram of ttakeoff of lysozyme aggregation in the presence of DMPS (green), DOPS (blue), POPS (orange), and DPSP (pink). For Lys, 200 μM of chicken-egg lysozyme was dissolved in 1xPBS with 2 mM of ThT; pH adjusted to pH 3.0. For Lys:DMPS, Lys:DOPS, Lys:POPS, and Lys:DSPS, 200 μM of chicken-egg lysozyme was mixed with an equivalent concentration of the corresponding lipid; pH was adjusted to pH 3.0. All samples were kept at 37 °C under 510 rpm for 160 h. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The role of the net charge of phospholipids on the toxicity of protein aggregates.

It becomes critically important to understand whether the discussed above interaction between lipids and amyloidogenic proteins may have any biological relevance. For this reason, it is important to determine the extent to which the net charge of phospholipids alters the toxicity of protein aggregates formed in the presence of lipids.

Using N27 rat dopaminergic cells, Matveyenka and co-workers found that protein aggregates formed in the presence of lipids typically exhibited lower cell toxicity compared to insulin fibrils (Ins) formed in the lipid-free environment [75,76]. Specifically, the toxicity of Ins:PC, Ins:PE, Ins:PS, and Ins:CL was ~ 1.5–2 times lower than the toxicity of Ins. It should be noted that the toxicity of Ins:PG was similar to the toxicity of Ins [75,76]. Similar results were reported by Zhaliazka and co-workers for lysozyme [82]. The researchers found that all tested anionic and zwitterionic lipids reduced the toxicity of lysozyme aggregates that were formed in their presence. Ali and co-workers recently reported that TTR fibrils formed in the presence of PS exerted a weaker toxicity on N27 rat dopaminergic cells compared to TTR fibrils formed in the lipid-free environment [84]. At the same time, both PC and PS strongly enhanced the toxicity of α-syn oligomers and fibrils formed at different stages of protein aggregation [85]. Dou and co-workers also demonstrated that such an increase in the toxicity of these aggregates is correlated with the enhanced levels of ROS and mitochondrial impairment that these aggregates exerted on the N27 cells, Fig. 7 [85].

Fig. 7.

Histograms of ROS (top), JC-1(middle), and LDH (bottom) toxicity assays of α-Syn (green, 70 AD47), α-Syn:PS (light blue, 5B9BD5) and α-Syn:PC (yellow, FFC000) aggregates grown at lag phase (20h), growth phase (32h) and late stage (50 h) of protein aggregation, as well as PC (olive, 385,723) and PS (navy, 2F5597) lipids themselves. Control is in brown (7F6000). The percentage is calculated by comparing the intensity in the test group to the positive control. Red asterisks (*) show the significance of the level of difference between α-Syn and α-Syn aggregates grown in the presence of lipids as well as between lipid samples and α-Syn. Blue asterisks show the significance of the level of difference between α-Syn aggregates formed in PC and PS conditions. NS is a nonsignificant difference, and *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, and ***p ≤ 0.001. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

It should be noted that although P:L ratio strongly influenced the rate of protein aggregation, Zhaliazka and co-workers demonstrated that P:L ratio made no effect on the toxicity of insulin fibrils formed under different P:L ratios [83].

The role of the length and saturation of FAs in phospholipids on the toxicity of protein aggregates.

Matveyenka and co-workers found that unsaturation of FAs present in phospholipids results in the increase in toxicity of insulin fibrils formed in their presence compared to insulin fibrils formed in the presence of lipids with fully saturated FAs [72]. Specifically, the toxicity of Ins:DOPS and Ins:POPS fibrils were ~ 2 times greater than the toxicity of Ins:DMPS fibrils [72]. However, the opposite relationship was observed by Frese and co-workers for lysozyme oligomers [101]. It was found that Lys:POPS and Lys:DOPS were less toxic to N27 rat dopaminergic cells than Lys:DMPS, but more toxic than Lys:DSPS oligomers. It should be noted that all oligomers formed in the presence of PS with different length and saturation of FAs were more toxic compared to those formed in the lipid-free environment. However, Frese and co-workers found that Lys:DSPS and Lys:DOPS fibrils were more toxic to N27 cells compared to Lys:DMPS, Lys:POPS, and Lys fibrils formed in the lipid-free environment [101]. Therefore, we can conclude that no clear relationship between the toxicity of protein aggregates, length and saturation of FAs in lipids that were present at the stage of the protein aggregation was observed for lysozyme oligomers and fibrils. Experimental findings reported by Ali and co-workers revealed that the length and saturation of FAs in PS did not alter the toxicity of TTR fibrils [84]. Specifically, the researchers found that toxicity of TTR:DMPS, TTR:DSPS, TTR:DOPS and TTR:POPS fibrils exerted similar degrees of toxicity on N27 rat dopaminergic cells, Fig. 8. Similar effects were observed on the level of ROS production and mitochondrial impairment in the cells exposed to these protein aggregates [84]. It should be noted that do date, there is no reported results on the role of the length and saturation of FAs and toxicity of α-syn oligomers and fibrils formed in the presence of such lipids.

Fig. 8.

Histograms of LDH (left), ROS (middle) and JC-1 (right) assays reveals differences between cell toxicity of TTR, TTR:POPS, TTR:DOPS, TTR:DMPS, and TTR:DSPS. Black asterisks (*) show a significant level of differences between protein aggregates and the control; purple (LHD), orange (ROS), and green (JC-1) asterisks (*) show significance level of difference between TTR and TTR aggregates formed in the presence of lipids; * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001. NS- non significant difference according to One-Way ANOVA and the Tukey HSD posthoc test. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Although no systematic studies on the role of lipids in the toxicity of Aβ are reported [103], several studies demonstrated that lipids could destabilize and rapidly resolubilize Aβ fibrils into oligomers [104]. Ramamoorthy’s group found that hydrophobic thickness of lipids vesicles played not only the major role in the Aβ1–42 aggregation, but also in the toxicity of Aβ1–42 fibrils. [105] Specifically, Korshavn and co-workers demonstrated that LUVs formed by short-chain lipid 1,2-dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (DLPC) stabilized Aβ1–42 aggregates lowering their toxicity [105].

What are the underlying molecular causes of lipid-induced differences in the rate of protein aggregation and toxicity of amyloid aggregates formed in the presence of lipids?

To answer this question, our group proposed to utilize nano-Infrared imaging also known as atomic force microscopy Infrared (AFM-IR) spectroscopy [106–110]. Using AFM-IR, a metallized scanning probe can be positioned directly on the protein oligomer or fibril [111]. Next, pulsed tunable IR light induces thermal expansions in these aggregates that are sensed by the scanning probe [112,113]. Thus, thermal expansion recorded by the scanning probe can be used to obtain the IR spectrum of the protein specimens [106,114–117]. IR spectra contain an amide I (1600–1700 cm−1) that can be used to determine protein secondary structure. Amide I centered around 1625 cm−1 indicates the predominance of parallel β-sheet in the protein aggregate, whereas its redshift to ~ 1645 cm−1 indicates the presence of α-helix [118]. Unordered protein exhibited amide I centered around 1660 cm−1, whereas anti-parallel β-sheet can be detected by the amide I positioned at 1695 cm−1 [118]. It should also be noted that AFM-IR can be used to detect the presence of lipids in analyzed protein aggregates. Specifically, lipids exhibit a carbonyl vibration centered around 1730 cm−1, as well as a set of P═O and P-O-H vibration in 800–1300 cm−1 spectra region [80]. Using AFM-IR, our group demonstrated that lipids were present in nearly all protein aggregates that were formed in their presence, Fig. 6 [21,48,49,71,74,77–79,82,85,119]. Thus, one can expect that the presence of lipids on the surface of amyloid oligomers and fibrils could strongly alter the interactions of such aggregates with lipid bilayers facilitating their endocytosis by neurons. Using fluorescence microscopy, Matveyenka and co-workers demonstrated that the chemical structure of lipids determines the extent to which insulin aggregates were able to damage cell endosomes and activate an unfolded protein response (UPRs) of N27 cells [74,76].

AFM-IR also revealed drastic differences in the secondary structure of protein aggregates that were formed in the presence of lipids [21,48,49,71,74,77–79,82,85,119]. Specifically, it was found that insulin and lysozyme aggregates formed in the presence of PC and PE were dominated by unordered protein compared to Ins and Lys fibrils that were primarily composed by parallel β-sheet, Fig. 9 [75,76,79]. Using AFM-IR, Dou and co-workers found that both PC and PS strongly altered the secondary structure of α-syn oligomers and fibrils formed at the different stages of protein aggregation [49,50,85]. Thus, one can expect that both presence of lipids on the surfaces of protein aggregates and lipid-induced difference in their secondary structure determine the discussed above differences in the toxicities that such aggregates exert to neuronal cells.

Fig. 9.

Nanoscale analysis of (A) Ins:PC-u (red) and Ins:PC-s (green) and (C) Ins:CL-u (black) and Ins:CL-s (blue) aggregates. Histograms of relative contributions of parallel β-sheet (blue), unordered protein secondary structure (light blue) and antiparallel β-sheet (green) in amide I of AFM-IR spectra collected from two populations (A and B) of Ins:PC-u and Ins:PC-s (B) and Ins:CL-u and Ins:CL-s (D) together with insulin aggregates (Ins) grown in the lipid-free environment. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2. Conclusions and future perspectives

This review critically discussed the most recent research results reported by several research groups on the role of lipids in the aggregation of amyloidogenic proteins. Based on these findings, one can conclude that the net charge of phospholipids, as well as the length and saturation of lipid FAs play an important role in the aggregation rates of amyloidogenic proteins. Experimental results summarized in this review also showed that lipids not only change the rate of protein aggregation, but also alter the secondary structure and, consequently, the toxicity of oligomers and fibrils that were formed in their presence.

Although the review is critically focused on Aβ, insulin, lysozyme, TTR, and α-syn, it should be noted that recently reported results indicate that stability of other amyloidogenic proteins, such as islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) and Tau, could be altered by lipids. Ait-Bouziad and co-workers found that full-length Tau (2N4R) and its K18 isoform could strongly interact with PS forming highly toxic Tau-PS oligomers [120]. Using NMR, the researchers found that protein and lipids in the oligomers were held together by strong electrostatic interactions between the charged amino acids residues of Tau and polar heads of PS [120]. Yau and co-workers found that not only the presence of PS, but also protein-to-lipid ratio strongly influenced the secondary structure of Tau-lipid oligomers [121]. Knight and Miranker found that DOPG:DOPC lipid vesicles enhanced the aggregation rates of IAPP [122]. Furthermore, this effect was linked to the anionic DOPG [122,123]. Following this work, La Rosa group demonstrated that cholesterol had a negligible effect on the kinetics of IAPP fibril growth on the surface of POPC/POPS vesicles [124,125].

Although the majority of results reported to date were focused on phospholipids, elucidation of the role of other lipids becomes critically important to fully understand the role of lipids in neurodegeneration. For instance, Matveyenka and co-workers found that polyunsaturated FAs (PUFAs) strongly accelerated aggregation of both insulin and α-syn [78]. Furthermore, α-syn and insulin fibrils formed in the presence of PUFAs exerted greater toxicity compared to the fibrils formed in the absence of FAs [78]. Ramamoorthy group found that in the presence of GMs, Aβ40 formed stable, short, rod-like fibrils that were more toxic to the cell than Aβ fibrils formed in the lipid-free environment [126,127]. Furthermore, the presence of these lipids strongly accelerated aggregation of Aβ, Fig. 10. Molecular dynamic simulations indicated that a change in the toxicity of Aβ40 aggregates could be due to strong interactions that were taking place between the peptide and monosialoganglioside [128]. Independently, Okada and co-workers showed that Aβ40 formed structurally different fibrils in the presence of GM1 compared to the fibrils grown in the lipid-free environment [129]. Using AFM, the researchers showed that toxic Aβ40 fibrils had a flat, tape-like morphology composed of a single β-sheet layer. These results are in good agreement with experimental findings reported by Rangachari group [130]. Saha and co-workers found that GM1-enriched DMPC liposomes induced the formation of toxic, low-molecular-weight oligomers that were not observed in the absence of GM1. This effect was attributed to a higher number of pores on GM1-enriched DMPC liposomes compared to pure DMPC vesicles that triggered protein aggregation [130], Fig. 11. Considering these results, it becomes important to investigate the effect of other classes of lipids, such as sphingolipids and plasmalogens.

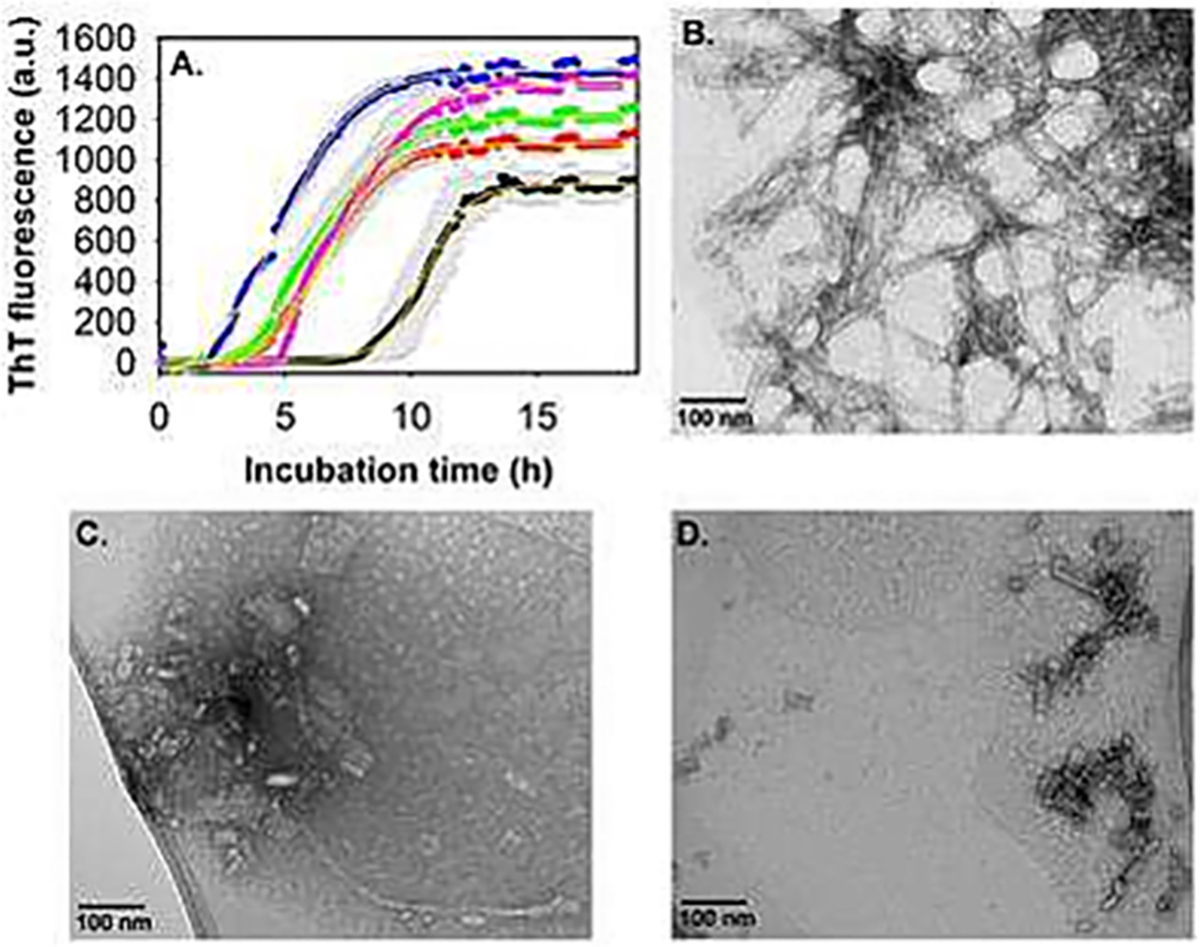

Fig. 10.

GM1 accelerated Aβ1–40 aggregation. (A) ThT fluorescence intensity of 10 μM Aβ1–40 alone (black) and with varying concentrations of GM1: 1 μM (red), 2.5 μM (green), 20 μM (magenta) and 40 μM (blue) in 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 at 37 °C, slow continuous shaking. The line of best fit (yellow, R2 = 0.99) through the data points was obtained by global fitting the data with a sigmoidal function. TEM images of 10 μM Aβ1–40 alone (B), and in the presence of 1 μM GM1 (C and D), acquired after 48 h incubation at physiological pH and temperature conditions. (C and D) Are the images of the same sample taken from two different positions in the TEM grid. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

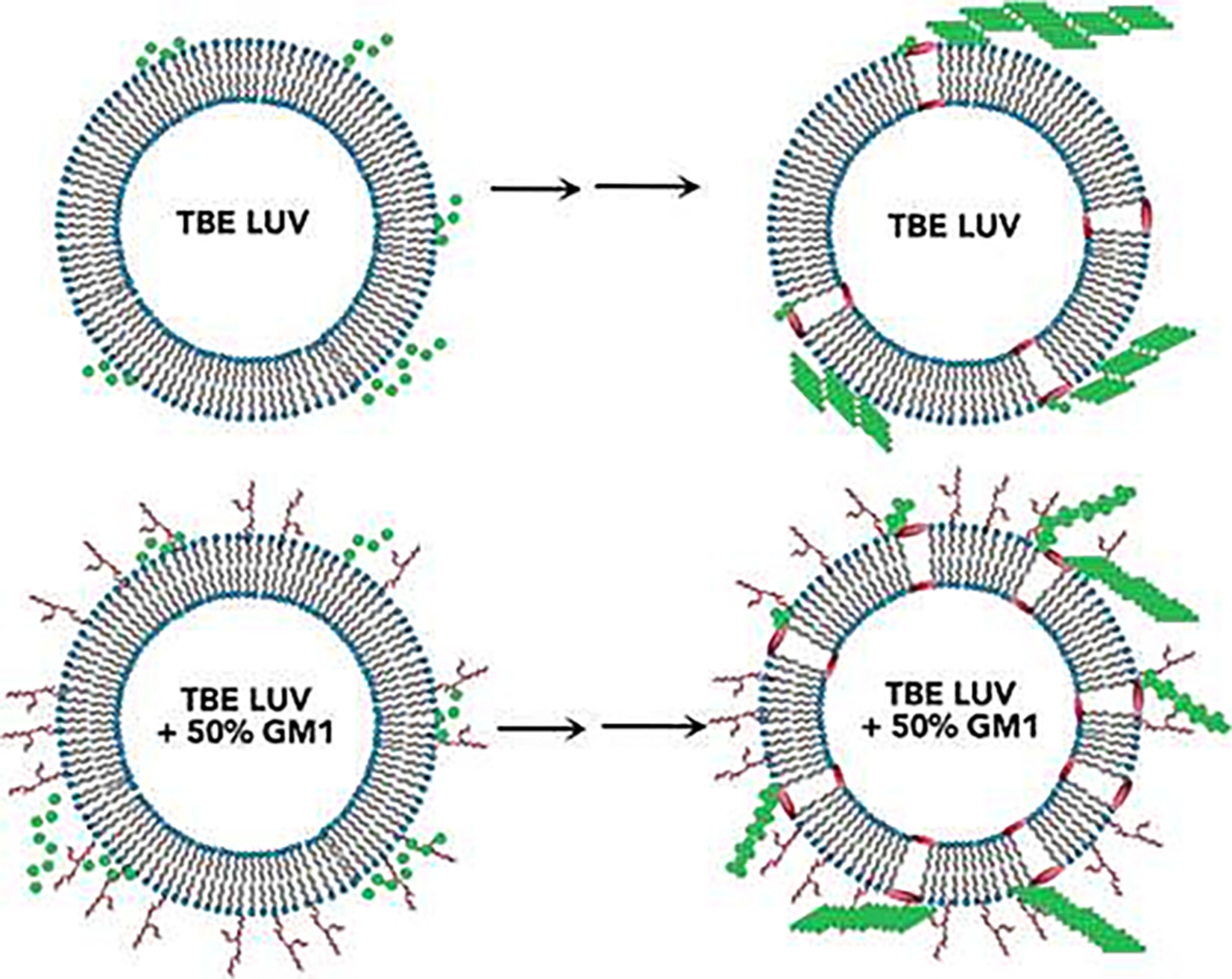

Fig. 11.

Schematic illustration of GM1-induced pore formation in total brain extract lipid (TBE) LUVs.

There is also an ongoing discussion about the intracellular vs extracellular mechanisms of amyloid formation [53,131–133]. An uptake of amyloidogenic proteins by cells results in the protein accumulation in cell endosomes. These intracellular vesicles are dominated by anionic bis(Monoacylglycero)phosphate (BMP). Recently reported results by Joshi and co-workers demonstrated that LUVs of BMP alone strongly accelerated insulin aggregation [132]. However, the presence of a very small amount of PC (23%) relative to BMP (77%), a ratio typical for late endosomes, strongly inhibited protein aggregation. These results are consistent with the recently reported findings by Vendruscolo group which demonstrated that unlikely any of the cell organelle could trigger protein aggregation [133]. Nevertheless, the role of mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum in the amyloid-induced toxicity should be studied in greater detail to understand the complex mechanism of amyloid diseases.

Finally, it is important to continue the search for the potential inhibitors of protein aggregation. Recently, Ruggeri and co-workers discovered that Aβ aggregation could be inhibited by bexarotene, a retinoid used to treat T-cell lymphoma [134]. Using AFM-IR, the researchers demonstrated that this molecular analyte directly bound to the peptide, which in that case failed to form amyloid fibrils. La Rosa group demonstrated that lipid vesicles could be used as a potential therapeutic approach against neurodegeneration [33,135]. Free lipids that dissociate out of these vesicles can bind amyloidogenic proteins forming lipid–protein complexes.

Acknowledgment

The author is also grateful to the National Institute of Health for the provided financial support (R35GM142869).

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

Dmitry Kurouski reports financial support was provided by Texas A&M University. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Abid Ali: Writing – review & editing. Tianyi Dou: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Aidan P. Holman: Writing – review & editing. Andrew Hung: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Luke Osborne: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Davis Pickett: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Axell Rodriguez: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Kiryl Zhaliazka: Writing – review & editing. Dmitry Kurouski: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- [1].Eisenberg DS, Sawaya MR, Structural studies of amyloid proteins at the molecular level, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 86 (2017) 69–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Nelson R, Eisenberg D, Structural models of amyloid-like fibrils, Adv. Protein Chem. 73 (2006) 235–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chen SW, Drakulic S, Deas E, Ouberai M, Aprile FA, Arranz R, Ness S, Roodveldt C, Guilliams T, De-Genst EJ, Klenerman D, Wood NW, Knowles TP, Alfonso C, Rivas G, Abramov AY, Valpuesta JM, Dobson CM, Cremades N, Structural characterization of toxic oligomers that are kinetically trapped during alpha-synuclein fibril formation, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112 (2015) E1994–E2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chiti F, Dobson CM, Protein Misfolding, amyloid formation, and human disease: a summary of Progress over the last decade, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 86 (2017) 27–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Knowles TP, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM, The amyloid state and its association with protein misfolding diseases, Nat. Rev. 15 (2014) 384–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Nguyen PH, Ramamoorthy A, Sahoo BR, Zheng J, Faller P, Straub JE, Dominguez L, Shea JE, Dokholyan NV, De Simone A, Ma B, Nussinov R, Najafi S, Ngo ST, Loquet A, Chiricotto M, Ganguly P, McCarty J, Li MS, Hall C, Wang Y, Miller Y, Melchionna S, Habenstein B, Timr S, Chen J, Hnath B, Strodel B, Kayed R, Lesne S, Wei G, Sterpone F, Doig AJ, Derreumaux P, Amyloid oligomers: a joint experimental/computational perspective on Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, type II diabetes, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Chem. Rev. 121 (2021) 2545–2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zhaliazka K, Kurouski D, Nanoscale characterization of parallel and antiparallel beta-sheet amyloid Beta 1–42 aggregates, ACS Chem. Neurosci. 13 (2022) 2813–2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bobo C, Chaignepain S, Henry S, Vignaud H, Ameadan A, Marchal C, Prado E, Doutch J, Schmitter JM, Nardin C, Lecomte S, Cullin C, Synthetic toxic Abeta(1–42) oligomers can assemble in different morphologies, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2017 (1861) 1168–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Vignaud H, Bobo C, Lascu I, Sorgjerd KM, Zako T, Maeda M, Salin B, Lecomte S, Cullin C, A structure-toxicity study of Ass42 reveals a new anti-parallel aggregation pathway, PLoS One 8 (2013) e80262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Banerjee S, Naik T, Baghel D, Ghosh A, Intermediate antiparallel fibrils in Abeta40 Dutch mutant aggregation: insights from nanoscale infrared spectroscopy, J. Phys. Chem. B 127 (2023) 5799–5807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tycko R, Solid-state NMR studies of amyloid fibril structure, Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 62 (2011) 279–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Guerrero-Ferreira R, Taylor NM, Mona D, Ringler P, Lauer ME, Riek R, Britschgi M, Stahlberg H, Cryo-EM structure of alpha-synuclein fibrils, Elife 7 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gremer L, Scholzel D, Schenk C, Reinartz E, Labahn J, Ravelli RBG, Tusche M, Lopez-Iglesias C, Hoyer W, Heise H, Willbold D, Schroder GF, Fibril structure of amyloid-beta(1–42) by cryo-electron microscopy, Science 358 (2017) 116–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kollmer M, Close W, Funk L, Rasmussen J, Bsoul A, Schierhorn A, Schmidt M, Sigurdson CJ, Jucker M, Fandrich M, Cryo-EM structure and polymorphism of Abeta amyloid fibrils purified from Alzheimer’s brain tissue, Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 4760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Li B, Ge P, Murray KA, Sheth P, Zhang M, Nair G, Sawaya MR, Shin WS, Boyer DR, Ye S, Eisenberg DS, Zhou ZH, Jiang L, Cryo-EM of full-length alpha-synuclein reveals fibril polymorphs with a common structural kernel, Nat. Commun. 9 (2018) 3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Paravastu AK, Qahwash I, Leapman RD, Meredith SC, Tycko R, Seeded growth of beta-amyloid fibrils from Alzheimer’s brain-derived fibrils produces a distinct fibril structure, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106 (2009) 7443–7448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kurouski D, Lu X, Popova L, Wan W, Shanmugasundaram M, Stubbs G, Dukor RK, Lednev IK, Nafie LA, Is supramolecular filament chirality the underlying cause of major morphology differences in amyloid fibrils? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 2302–2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Srinivasan S, Patke S, Wang Y, Ye Z, Litt J, Srivastava SK, Lopez MM, Kurouski D, Lednev IK, Kane RS, Colon W, Pathogenic serum amyloid a 1.1 shows a long oligomer-rich fibrillation lag phase contrary to the highly amyloidogenic non-pathogenic SAA2.2, J. Biol. Chem. 288 (2013) 2744–2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jimenez JL, Nettleton EJ, Bouchard M, Robinson CV, Dobson CM, Saibil HR, The protofilament structure of insulin amyloid fibrils, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 (2002) 9196–9201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Han S, Kollmer M, Markx D, Claus S, Walther P, Fandrich M, Amyloid plaque structure and cell surface interactions of beta-amyloid fibrils revealed by electron tomography, Sci. Rep. 7 (2017) 43577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhaliazka K, Matveyenka M, Kurouski D, Lipids uniquely Alter the secondary structure and toxicity of amyloid beta 1–42 aggregates, FEBS J. 290 (2023) 3203–3220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Banerjee S, Hashemi M, Zagorski K, Lyubchenko YL, Cholesterol in membranes facilitates aggregation of amyloid beta protein at physiologically relevant concentrations, ACS Chem. Neurosci. 12 (2021) 506–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hashemi M, Banerjee S, Lyubchenko YL, Free cholesterol accelerates Abeta self-assembly on membranes at physiological concentration, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yu X, Zheng J, Cholesterol promotes the interaction of Alzheimer beta-amyloid monomer with lipid bilayer, J. Mol. Biol. 421 (2012) 561–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Phan HTT, Shimokawa N, Sharma N, Takagi M, Vestergaard MC, Strikingly different effects of cholesterol and 7-ketocholesterol on lipid bilayer-mediated aggregation of amyloid beta (1–42), Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 14 (2018) 98–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Habchi J, Chia S, Galvagnion C, Michaels TCT, Bellaiche MMJ, Ruggeri FS, Sanguanini M, Idini I, Kumita JR, Sparr E, Linse S, Dobson CM, Knowles TPJ, Vendruscolo M, Cholesterol catalyses Abeta42 aggregation through a heterogeneous nucleation pathway in the presence of lipid membranes, Nat. Chem. 10 (2018) 673–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Henry S, Vignaud H, Bobo C, Decossas M, Lambert O, Harte E, Alves ID, Cullin C, Lecomte S, Interaction of Abeta(1–42) amyloids with lipids promotes “off-pathway” oligomerization and membrane damage, Biomacromolecules 16 (2015) 944–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Rudajev V, Novotny J, Cholesterol as a key player in amyloid beta-mediated toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease, Front. Mol. Neurosci. 15 (2022) 937056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Coles M, Bicknell W, Watson AA, Fairlie DP, Craik DJ, Solution structure of amyloid beta-peptide(1–40) in a water-micelle environment. Is the membrane-spanning domain where we think it is? Biochemistry 37 (1998) 11064–11077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Serra-Batiste M, Ninot-Pedrosa M, Bayoumi M, Gairi M, Maglia G, Carulla N, Abeta42 assembles into specific beta-barrel pore-forming oligomers in membrane-mimicking environments, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113 (2016) 10866–10871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lee DK, Brender JR, Sciacca MF, Krishnamoorthy J, Yu C, Ramamoorthy A, Lipid composition-dependent membrane fragmentation and pore-forming mechanisms of membrane disruption by pexiganan (MSI-78), Biochemistry 52 (2013) 3254–3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sciacca MF, Kotler SA, Brender JR, Chen J, Lee DK, Ramamoorthy A, Two-step mechanism of membrane disruption by Abeta through membrane fragmentation and pore formation, Biophys. J. 103 (2012) 702–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sciacca MF, Lolicato F, Tempra C, Scollo F, Sahoo BR, Watson MD, Garcia-Vinuales S, Milardi D, Raudino A, Lee JC, Ramamoorthy A, La Rosa C, Lipid-chaperone hypothesis: a common molecular mechanism of membrane disruption by intrinsically disordered proteins, ACS Chem. Neurosci. 11 (2020) 4336–4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lindström F, Bokvist M, Sparrman T, Gröbner G, Association of amyloid-β peptide with membrane surfaces monitored by solid state NMR, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 4 (2002) 5524–5530. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hawkes CH, Del Tredici K, Braak H, Parkinson’s disease: a dual-hit hypothesis, Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 33 (2007) 599–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E, Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease, Neurobiol. Aging 24 (2003) 197–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Braak H, Ghebremedhin E, Rub U, Bratzke H, Del Tredici K, Stages in the development of Parkinson’s disease-related pathology, Cell Tissue Res. 318 (2004) 121–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kordower JH, Chu Y, Hauser RA, Freeman TB, Olanow CW, Lewy body-like pathology in long-term embryonic nigral transplants in Parkinson’s disease, Nat. Med. 14 (2008) 504–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kordower JH, Chu Y, Hauser RA, Olanow CW, Freeman TB, Transplanted dopaminergic neurons develop PD pathologic changes: a second case report, Mov. Disord. 23 (2008) 2303–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Li JY, Englund E, Holton JL, Soulet D, Hagell P, Lees AJ, Lashley T, Quinn NP, Rehncrona S, Bjorklund A, Widner H, Revesz T, Lindvall O, Brundin P, Lewy bodies in grafted neurons in subjects with Parkinson’s disease suggest host-to-graft disease propagation, Nat. Med. 14 (2008) 501–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Mougenot AL, Nicot S, Bencsik A, Morignat E, Verchere J, Lakhdar L, Legastelois S, Baron T, Prion-like acceleration of a synucleinopathy in a transgenic mouse model, Neurobiol. Aging 33 (2012) 2225–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Masuda-Suzukake M, Nonaka T, Hosokawa M, Oikawa T, Arai T, Akiyama H, Mann DM, Hasegawa M, Prion-like spreading of pathological alpha-synuclein in brain, Brain 136 (2013) 1128–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kim S, Kwon SH, Kam TI, Panicker N, Karuppagounder SS, Lee S, Lee JH, Kim WR, Kook M, Foss CA, Shen C, Lee H, Kulkarni S, Pasricha PJ, Lee G, Pomper MG, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Ko HS, Transneuronal propagation of pathologic alpha-Synuclein from the gut to the brain models Parkinson’s disease, Neuron 103 (2019) 627–641 e627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hoffmann AC, Minakaki G, Menges S, Salvi R, Savitskiy S, Kazman A, Vicente Miranda H, Mielenz D, Klucken J, Winkler J, Xiang W, Extracellular aggregated alpha synuclein primarily triggers lysosomal dysfunction in neural cells prevented by trehalose, Sci. Rep. 9 (2019) 544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Vogiatzi T, Xilouri M, Vekrellis K, Stefanis L, Wild type alpha-synuclein is degraded by chaperone-mediated autophagy and macroautophagy in neuronal cells, J. Biol. Chem. 283 (2008) 23542–23556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Shahmoradian SH, Lewis AJ, Genoud C, Hench J, Moors TE, Navarro PP, Castano-Diez D, Schweighauser G, Graff-Meyer A, Goldie KN, Sutterlin R, Huisman E, Ingrassia A, Gier Y, Rozemuller AJM, Wang J, Paepe A, Erny J, Staempfli A, Hoernschemeyer J, Grosseruschkamp F, Niedieker D, El-Mashtoly SF, Quadri M, Van IWFJ, Bonifati V, Gerwert K, Bohrmann B, Frank S, Britschgi M, Stahlberg H, Van de Berg WDJ, Lauer ME, Lewy pathology in Parkinson’s disease consists of crowded organelles and lipid membranes, Nat. Neurosci. 22 (2019) 1099–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Killinger BA, Melki R, Brundin P, Kordower JH, Endogenous alpha-synuclein monomers, oligomers and resulting pathology: let’s talk about the lipids in the room, NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 5 (2019) 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zhaliazka K, Kurouski D, Nanoscale imaging of individual amyloid aggregates extracted from brains of Alzheimer and Parkinson patients reveals presence of lipids in alpha-synuclein but not in amyloid beta(1–42) fibrils, Protein Sci. 32 (2023) e4598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Dou T, Kurouski D, Phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylserine uniquely modify the secondary structure of alpha-Synuclein oligomers formed in their presence at the early stages of protein aggregation, ACS Chem. Neurosci. 13 (2022) 2380–2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Dou T, Zhou L, Kurouski D, Unravelling the structural Organization of Individual alpha-Synuclein oligomers grown in the presence of phospholipids, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12 (2021) 4407–4414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Galvagnion C, The role of lipids interacting with -Synuclein in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease, J. Parkinsons Dis. 7 (2017) 433–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Galvagnion C, Brown JW, Ouberai MM, Flagmeier P, Vendruscolo M, Buell AK, Sparr E, Dobson CM, Chemical properties of lipids strongly affect the kinetics of the membrane-induced aggregation of alpha-synuclein, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113 (2016) 7065–7070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Galvagnion C, Buell AK, Meisl G, Michaels TC, Vendruscolo M, Knowles TP, Dobson CM, Lipid vesicles trigger alpha-synuclein aggregation by stimulating primary nucleation, Nat. Chem. Biol. 11 (2015) 229–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Galvagnion C, Topgaard D, Makasewicz K, Buell AK, Linse S, Sparr E, Dobson CM, Lipid dynamics and phase transition within alpha-Synuclein amyloid fibrils, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10 (2019) 7872–7877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Meade RM, Williams RJ, Mason JM, A series of helical alpha-synuclein fibril polymorphs are populated in the presence of lipid vesicles, NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 6 (2020) 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Hannestad JK, Rocha S, Agnarsson B, Zhdanov VP, Wittung-Stafshede P, Hook F, Single-vesicle imaging reveals lipid-selective and stepwise membrane disruption by monomeric alpha-synuclein, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117 (2020) 14178–14186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Middleton ER, Rhoades E, Effects of curvature and composition on alpha-synuclein binding to lipid vesicles, Biophys. J. 99 (2010) 2279–2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].van Rooijen BD, Claessens MM, Subramaniam V, Lipid bilayer disruption by oligomeric alpha-synuclein depends on bilayer charge and accessibility of the hydrophobic core, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1788 (2009) 1271–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Iyer A, Claessens M, Disruptive membrane interactions of alpha-synuclein aggregates, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2019 (1867) 468–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Iyer A, Petersen NO, Claessens MM, Subramaniam V, Amyloids of alpha-synuclein affect the structure and dynamics of supported lipid bilayers, Biophys. J. 106 (2014) 2585–2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Iyer A, Roeters SJ, Schilderink N, Hommersom B, Heeren RM, Woutersen S, Claessens MM, Subramaniam V, The impact of N-terminal acetylation of alpha-Synuclein on phospholipid membrane binding and fibril structure, J. Biol. Chem. 291 (2016) 21110–21122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Iyer A, Schilderink N, Claessens M, Subramaniam V, Membrane-bound alpha Synuclein clusters induce impaired lipid diffusion and increased lipid packing, Biophys. J. 111 (2016) 2440–2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Stockl M, Fischer P, Wanker E, Herrmann A, Alpha-synuclein selectively binds to anionic phospholipids embedded in liquid-disordered domains, J. Mol. Biol. 375 (2008) 1394–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Jiang Z, Flynn JD, Teague WE Jr, Gawrisch K, Lee JC, Stimulation of alpha-synuclein amyloid formation by phosphatidylglycerol micellar tubules, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2018 (1860) 1840–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Jiang Z, de Messieres M, Lee JC, Membrane remodeling by alpha-synuclein and effects on amyloid formation, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (2013) 15970–15973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Viennet T, Wordehoff MM, Uluca B, Poojari C, Shaykhalishahi H, Willbold D, Strodel B, Heise H, Buell AK, Hoyer W, Etzkorn M, Structural insights from lipid-bilayer nanodiscs link alpha-Synuclein membrane-binding modes to amyloid fibril formation, Commun. Biol. 1 (2018) 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Fusco G, De Simone A, Gopinath T, Vostrikov V, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM, Veglia G, Direct observation of the three regions in alpha-synuclein that determine its membrane-bound behaviour, Nat. Commun. 5 (2014) 3827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Giasson BI, Murray IV, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, A hydrophobic stretch of 12 amino acid residues in the middle of alpha-synuclein is essential for filament assembly, J. Biol. Chem. 276 (2001) 2380–2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Ueda K, Fukushima H, Masliah E, Xia Y, Iwai A, Yoshimoto M, Otero DA, Kondo J, Ihara Y, Saitoh T, Molecular cloning of cDNA encoding an unrecognized component of amyloid in Alzheimer disease, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90 (1993) 11282–11286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Frieg B, Antonschmidt L, Dienemann C, Geraets JA, Najbauer EE, Matthes D, de Groot BL, Andreas LB, Becker S, Griesinger C, Schroder GF, The 3D structure of lipidic fibrils of alpha-synuclein, Nat. Commun. 13 (2022) 6810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Matveyenka M, Rizevsky S, Kurouski D, Unsaturation in the fatty acids of phospholipids drastically alters the structure and toxicity of insulin aggregates grown in their presence, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. (2022) 4563–4569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Matveyenka M, Rizevsky S, Kurouski D, The degree of unsaturation of fatty acids in phosphatidylserine alters the rate of insulin aggregation and the structure and toxicity of amyloid aggregates, FEBS Lett. 596 (2022) 1424–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Matveyenka M, Rizevsky S, Kurouski D, Length and unsaturation of fatty acids of phosphatidic acid determines the aggregation rate of insulin and modifies the structure and toxicity of insulin aggregates, ACS Chem. Neurosci. 13 (2022) 2483–2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Matveyenka M, Rizevsky S, Kurouski D, Amyloid aggregates exert cell toxicity causing irreversible damages in the endoplasmic reticulum, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. basis Dis. 1868 (2022) 166485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Matveyenka M, Rizevsky S, Kurouski D, Elucidation of the effect of phospholipid charge on the rate of insulin aggregation and structure and toxicity of amyloid fibrils, ACS Omega 8 (2023) 12379–12386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Matveyenka M, Rizevsky S, Pellois JP, Kurouski D, Lipids uniquely alter rates of insulin aggregation and lower toxicity of amyloid aggregates, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1868 (2023) 159247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Matveyenka M, Zhaliazka K, Kurouski D, Concentration of phosphatidylserine influence rates of insulin aggregation and toxicity of amyloid aggregates in vitro, ACS Chem. Neurosci. 14 (2023) 2396–2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Matveyenka M, Zhaliazka K, Kurouski D, Unsaturated fatty acids uniquely Alter aggregation rate of α-Synuclein and insulin and modify secondary structure and toxicity of amyloid aggregates formed in their presence, FASEB J. (2023), 10.1096/fj.202300003R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Matveyenka M, Zhaliazka K, Rizevsky S, Kurouski D, Lipids uniquely alter secondary structure and toxicity of lysozyme aggregates, FASEB J. 36 (2022) e22543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Rizevsky S, Matveyenka M, Kurouski D, Nanoscale structural analysis of a lipid-driven aggregation of insulin, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13 (2022) 2467–2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Rizevsky S, Zhaliazka K, Matveyenka M, Quinn K, Kurouski D, Lipids reverse supramolecular chirality and reduce toxicity of amyloid fibrils, FEBS J 289 (2022) 7537–7544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Zhaliazka K, Rizevsky S, Matveyenka M, Serada V, Kurouski D, Charge of phospholipids determines the rate of lysozyme aggregation but not the structure and toxicity of amyloid aggregates, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13 (2022) 8833–8839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Zhaliazka K, Serada V, Matveyenka M, Rizevsky S, Kurouski D, Protein-to-lipid ratio uniquely changes the rate of lysozyme aggregation but does not significantly alter toxicity of mature protein aggregates, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1868 (2023) 159305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Ali A, Zhaliazka K, Dou T, Holman AP, Kurouski D, Role of saturation and length of fatty acids of phosphatidylserine in the aggregation of transthyretin, ACS Chem. Neurosci. 14 (2023) 3499–3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Dou T, Matveyenka M, Kurouski D, Elucidation of secondary structure and toxicity of alpha-Synuclein oligomers and fibrils grown in the presence of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylserine, ACS Chem. Neurosci. 14 (2023) 3183–3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Fitzner D, Bader JM, Penkert H, Bergner CG, Su M, Weil MT, Surma MA, Mann M, Klose C, Simons M, Cell-type- and brain-region-resolved mouse brain Lipidome, Cell Rep. 32 (2020) 108132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Alecu I, Bennett SAL, Dysregulated lipid metabolism and its role in alpha-Synucleinopathy in Parkinson’s disease, Front. Neurosci. 13 (2019) 328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Levental I, Levental KR, Heberle FA, Lipid rafts: controversies resolved, mysteries remain, Trends Cell Biol. 30 (2020) 341–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Choi ML, Chappard A, Singh BP, Maclachlan C, Rodrigues M, Fedotova EI, Berezhnov AV, De S, Peddie CJ, Athauda D, Virdi GS, Zhang W, Evans JR, Wernick AI, Zanjani ZS, Angelova PR, Esteras N, Vinokurov AY, Morris K, Jeacock K, Tosatto L, Little D, Gissen P, Clarke DJ, Kunath T, Collinson L, Klenerman D, Abramov AY, Horrocks MH, Gandhi S, Pathological structural conversion of alpha-synuclein at the mitochondria induces neuronal toxicity, Nat. Neurosci. 25 (2022) 1134–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Jo E, McLaurin J, Yip CM, St George-Hyslop P, Fraser PE, alpha-Synuclein membrane interactions and lipid specificity, J. Biol. Chem. 275 (2000) 34328–34334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Fortin DL, Troyer MD, Nakamura K, Kubo S, Anthony MD, Edwards RH, Lipid rafts mediate the synaptic localization of alpha-synuclein, J. Neurosci. 24 (2004) 6715–6723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Martinez Z, Zhu M, Han S, Fink AL, GM1 specifically interacts with alpha-synuclein and inhibits fibrillation, Biochemistry 46 (2007) 1868–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Suzuki K, Iseki E, Katsuse O, Yamaguchi A, Katsuyama K, Aoki I, Yamanaka S, Kosaka K, Neuronal accumulation of alpha- and beta-synucleins in the brain of a GM2 gangliosidosis mouse model, Neuroreport 14 (2003) 551–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Kinoshita M, Kakimoto E, Terakawa MS, Lin Y, Ikenoue T, So M, Sugiki T, Ramamoorthy A, Goto Y, Lee YH, Model membrane size-dependent amyloidogenesis of Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta peptides, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19 (2017) 16257–16266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Terakawa MS, Lin Y, Kinoshita M, Kanemura S, Itoh D, Sugiki T, Okumura M, Ramamoorthy A, Lee YH, Impact of membrane curvature on amyloid aggregation, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2018 (1860) 1741–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Terakawa MS, Yagi H, Adachi M, Lee YH, Goto Y, Small liposomes accelerate the fibrillation of amyloid beta (1–40), J. Biol. Chem. 290 (2015) 815–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Davidson WS, Jonas A, Clayton DF, George JM, Stabilization of alpha-synuclein secondary structure upon binding to synthetic membranes, J. Biol. Chem. 273 (1998) 9443–9449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Shvadchak VV, Falomir-Lockhart LJ, Yushchenko DA, Jovin TM, Specificity and kinetics of alpha-synuclein binding to model membranes determined with fluorescent excited state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT) probe, J. Biol. Chem. 286 (2011) 13023–13032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Kjaer L, Giehm L, Heimburg T, Otzen D, The influence of vesicle size and composition on alpha-synuclein structure and stability, Biophys. J. 96 (2009) 2857–2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Drin G, Antonny B, Amphipathic helices and membrane curvature, FEBS Lett. 584 (2010) 1840–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Frese A, Goode C, Zhaliazka K, Holman A, Dou T, Kurouski D, Length and saturation of fatty acids in phosphatidylserine determine the rate of lysozyme aggregation simultaneously altering the structure and toxicity of amyloid oligomers and fibrils, Protein Sci. (2023), 10.1002/pro.4717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Holman AP, Quinn K, Kumar R, Kmiecik S, Ali A, Kurouski D, Fatty acids reverse the supramolecular chirality of insulin fibrils, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14 (2023) 6935–6939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Rangachari V, Dean DN, Rana P, Vaidya A, Ghosh P, Cause and consequence of Abeta - lipid interactions in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2018 (1860) 1652–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Martins IC, Kuperstein I, Wilkinson H, Maes E, Vanbrabant M, Jonckheere W, Van Gelder P, Hartmann D, D’Hooge R, De Strooper B, Schymkowitz J, Rousseau F, Lipids revert inert Abeta amyloid fibrils to neurotoxic protofibrils that affect learning in mice, EMBO J. 27 (2008) 224–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Korshavn KJ, Satriano C, Lin Y, Zhang R, Dulchavsky M, Bhunia A, Ivanova MI, Lee YH, La Rosa C, Lim MH, Ramamoorthy A, Reduced lipid bilayer thickness regulates the aggregation and cytotoxicity of amyloid-beta, J. Biol. Chem. 292 (2017) 4638–4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Ruggeri FS, Flagmeier P, Kumita JR, Meisl G, Chirgadze DY, Bongiovanni MN, Knowles TPJ, Dobson CM, The influence of pathogenic mutations in alpha-Synuclein on biophysical and structural characteristics of amyloid fibrils, ACS Nano 14 (2020) 5213–5222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Ruggeri FS, Mannini B, Schmid R, Vendruscolo M, Knowles TPJ, Single molecule secondary structure determination of proteins through infrared absorption nanospectroscopy, Nat. Commun. 11 (2020) 2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Rizevsky S, Kurouski D, Nanoscale structural Organization of Insulin Fibril Polymorphs Revealed by atomic force microscopy-infrared spectroscopy (AFM-IR), Chembiochem 21 (2020) 481–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Rizevsky S, Zhaliazka M, Dou T, Matveyenka M, Characterization of substrates and surface-enhancement in atomic force microscopy infrared (AFM-IR) analysis of amyloid aggregates, J. Phys. Chem. C 126 (2022) 4157–4162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Centrone A, Infrared imaging and spectroscopy beyond the diffraction limit, Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 8 (2015) 101–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Dazzi A, PhotoThermal induced resonance. Application to infrared Spectromicroscopy, in: Volz S (Ed.), Thermal Nanosystems and Nanomaterials, Springer, Berlin, 2009, pp. 469–503. [Google Scholar]

- [112].Kurouski D, Dazzi A, Zenobi R, Centrone A, Infrared and Raman chemical imaging and spectroscopy at the nanoscale, Chem. Soc. Rev. 49 (2020) 3315–3347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Dou T, Li Z, Zhang J, Evilevitch A, Kurouski D, Nanoscale structural characterization of individual viral particles using atomic force microscopy infrared spectroscopy (AFM-IR) and tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (TERS), Anal. Chem. 92 (2020) 11297–11304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Ramer G, Ruggeri FS, Levin A, Knowles TPJ, Centrone A, Determination of polypeptide conformation with nanoscale resolution in water, ACS Nano 12 (2018) 6612–6619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Ruggeri FS, Benedetti F, Knowles TPJ, Lashuel HA, Sekatskii S, Dietler G, Identification and nanomechanical characterization of the fundamental single-strand protofilaments of amyloid alpha-synuclein fibrils, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115 (2018) 7230–7235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Ruggeri FS, Charmet J, Kartanas T, Peter Q, Chia S, Habchi J, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M, Knowles TPJ, Microfluidic deposition for resolving single-molecule protein architecture and heterogeneity, Nat. Commun. 9 (2018) 3890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Ruggeri FS, Longo G, Faggiano S, Lipiec E, Pastore A, Dietler G, Infrared nanospectroscopy characterization of oligomeric and fibrillar aggregates during amyloid formation, Nat. Commun. 6 (2015) 7831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Kurouski D, Lombardi RA, Dukor RK, Lednev IK, Nafie LA, Direct observation and pH control of reversed supramolecular chirality in insulin fibrils by vibrational circular dichroism, Chem. Commun. 46 (2010) 7154–7156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Richard-Lacroix M, Deckert V, Direct molecular-level near-field plasmon and temperature assessment in a single plasmonic hotspot, Light Sci Appl 9 (2020) 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Ait-Bouziad N, Lv G, Mahul-Mellier AL, Xiao S, Zorludemir G, Eliezer D, Walz T, Lashuel HA, Discovery and characterization of stable and toxic tau/phospholipid oligomeric complexes, Nat. Commun. 8 (2017) 1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Yao QQ, Wen J, Perrett S, Wu S, Distinct lipid membrane-mediated pathways of tau assembly revealed by single-molecule analysis, Nanoscale 14 (2022) 4604–4613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Knight JD, Miranker AD, Phospholipid catalysis of diabetic amyloid assembly, J. Mol. Biol. 341 (2004) 1175–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Knight JD, Hebda JA, Miranker AD, Conserved and cooperative assembly of membrane-bound alpha-helical states of islet amyloid polypeptide, Biochemistry 45 (2006) 9496–9508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Milardi D, Gazit E, Radford SE, Xu Y, Gallardo RU, Caflisch A, Westermark GT, Westermark P, Rosa C, Ramamoorthy A, Proteostasis of islet amyloid polypeptide: a molecular perspective of risk factors and protective strategies for type II diabetes, Chem. Rev. 121 (2021) 1845–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Sciacca MF, Lolicato F, Di Mauro G, Milardi D, D’Urso L, Satriano C, Ramamoorthy A, La Rosa C, The role of cholesterol in driving IAPP-membrane interactions, Biophys. J. 111 (2016) 140–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Chakravorty A, McCalpin SD, Sahoo BR, Ramamoorthy A, Brooks CL 3rd, Free gangliosides can Alter amyloid-beta aggregation, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13 (2022) 9303–9308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Kumar M, Ivanova MI, Ramamoorthy A, Non-micellar ganglioside GM1 induces an instantaneous conformational change in Abeta(42) leading to the modulation of the peptide amyloid-fibril pathway, Biophys. Chem. 301 (2023) 107091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Kumar M, Ivanova MI, Ramamoorthy A, Ganglioside GM1 produces stable, short, and cytotoxic Aβ40 protofibrils, Chem. Commun. 59 (2023) 7040–7043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Okada Y, Okubo K, Ikeda K, Yano Y, Hoshino M, Hayashi Y, Kiso Y, Itoh-Watanabe H, Naito A, Matsuzaki K, Toxic amyloid tape: a novel mixed antiparallel/parallel beta-sheet structure formed by amyloid beta-protein on GM1 clusters, ACS Chem. Neurosci. 10 (2019) 563–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Saha J, Bose P, Dhakal S, Ghosh P, Rangachari V, Ganglioside-enriched phospholipid vesicles induce cooperative Abeta oligomerization and membrane disruption, Biochemistry 61 (2022) 2206–2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Takahashi RH, Milner TA, Li F, Nam EE, Edgar MA, Yamaguchi H, Beal MF, Xu H, Greengard P, Gouras GK, Intraneuronal Alzheimer abeta42 accumulates in multivesicular bodies and is associated with synaptic pathology, Am. J. Pathol. 161 (2002) 1869–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Joshi R, Zhaliazka K, Holman AP, Kurouski D, Elucidation of the role of lipids in late endosomes on the aggregation of insulin, ACS Chem. Neurosci. 14 (2023) 3551–3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Baumann KN, Sneideriene G, Sanguanini M, Schneider M, Rimon O, Gonzalez Diaz A, Greer H, Thacker D, Linse S, Knowles TPJ, Vendruscolo M, A kinetic map of the influence of biomimetic lipid model membranes on abeta(42) aggregation, ACS Chem. Neurosci. vol. 14 (2023) 323–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Ruggeri FS, Habchi J, Chia S, Horne RI, Vendruscolo M, Knowles TPJ, Infrared nanospectroscopy reveals the molecular interaction fingerprint of an aggregation inhibitor with single Abeta42 oligomers, Nat. Commun. 12 (2021) 688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [135].Scollo F, Tempra C, Lolicato F, Sciacca MFM, Raudino A, Milardi D, La Rosa C, Phospholipids critical micellar concentrations trigger different mechanisms of intrinsically disordered proteins interaction with model membranes, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9 (2018) 5125–5129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.