Abstract

Primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (PGI-DLBCL) is the most common lymphoma in the gastrointestinal tract, yet research on its clinicopathological characteristics and long-term prognosis across different sites is lacking. This study aims to assess these aspects in PGI-DLBCL patients using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Patients diagnosed with PGI-DLBCL between 2000 and 2021 were extracted from the SEER database. The clinicopathological characteristics of PGI-DLBCL in the stomach, small intestine, and colorectum were compared using Chi-square tests, and overall survival (OS) as well as cancer-specific survival (CSS) were evaluated using Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox regression analysis. A total of 10,935 patients were enrolled, with the stomach being the most prevalent site (53.3%), followed by the small intestine (26.3%) and colorectum (20.5%). Gastric PGI-DLBCL patients had higher proportions of elderly, females, and stage III/IV disease, primarily treated with chemotherapy. Patients with small intestine and colorectal PGI-DLBCL showed significantly better OS (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.88–0.98, P = 0.021; HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.82–0.95, P < 0.001) and CSS (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.81–0.98, P = 0.022; HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.78–0.94, P < 0.001) compared to gastric PGI-DLBCL. OS and CSS were similar between small intestine and colorectal PGI-DLBCL (P > 0.05). Five-year OS rates were 48.8%, 55.4%, and 52.8% for stomach, small intestine, and colorectum, respectively, with corresponding CSS rates of 61.5%, 65.6%, and 66.0%. Multivariate Cox regression identified age, race, marital status, tumor stage, location, and treatment as independent risk factors for OS and CSS. For gastric DLBCL, radiotherapy plus chemotherapy was most effective in improving prognosis, while surgery combined with chemotherapy was superior for small intestine and colorectal DLBCL. Gastric PGI-DLBCL has distinct clinicopathological features from small intestine and colorectum PGI-DLBCL, and may have a worse prognosis. However, chemoradiotherapy may enhance its outcome.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-04537-9.

Keywords: Primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Clinicopathological characteristics, Prognosis, SEER

Subject terms: Gastrointestinal cancer, Cancer, Haematological cancer, Lymphoma

Introduction

Primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (PGI-DLBCL) represents a significant subset of non-Hodgkin lymphomas and is the most prevalent type within the gastrointestinal tract1–3. In recent years, the incidence of PGI-DLBCL has been on the rise, mirroring the global increase in lymphoma cases4,5. Given its clinical importance, understanding the unique clinicopathological characteristics and long-term prognosis of this disease is vital for optimizing patient management and enhancing outcomes. Despite its significance, research examining the variations in clinicopathological features and prognosis across different gastrointestinal sites remains limited. Previous studies have predominantly focused on the clinical characteristics, prognosis, and treatment strategies of DLBCL in specific locations, such as the stomach6,7, small intestine8, or colon9. While these studies have provided valuable insights into the pathogenesis, histological features, and therapeutic responses of the disease, they often aggregate lymphomas from various gastrointestinal locations, potentially masking distinct clinicopathological profiles and prognostic implications. Furthermore, there is growing evidence to suggest that PGI-DLBCL arising in different sites may exhibit distinct clinicopathological features and prognoses. However, these studies have failed to compare these aspects longitudinally across different gastrointestinal locations. Additionally, long-term survival data, particularly those comparing different gastrointestinal sites, are scarce, leaving a significant gap in our understanding of PGI-DLBCL.

To address this knowledge gap, the present study aims to conduct a location-specific analysis of PGI-DLBCL using a large population-based dataset from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Our primary objectives are twofold: first, to compare the clinicopathological characteristics of PGI-DLBCL arising in the stomach, small intestine, and colorectum; and second, to assess their respective long-term overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS). By identifying site-specific differences, we aim to provide a more nuanced understanding of PGI-DLBCL, potentially guiding tailored treatment approaches. We anticipate that our findings will not only deepen the understanding of PGI-DLBCL but also inform clinical decision-making, ultimately leading to improved patient outcomes.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

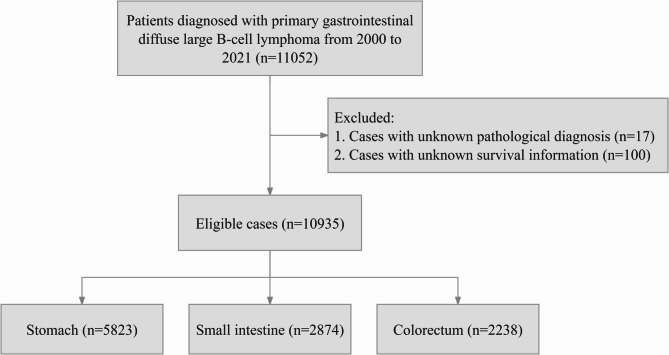

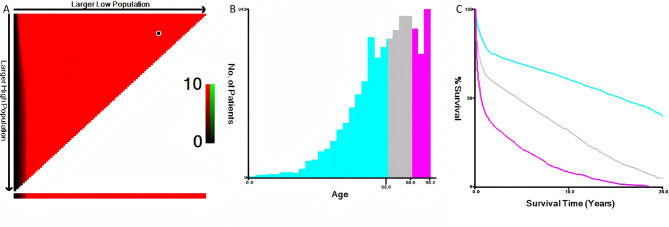

This research focused on individuals with a verified diagnosis of PGI-DLBCL spanning from 2000 to 2021, utilizing data sourced from the SEER database. Patient identification was based on the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3) code 9680/3, specifying Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (NOS). Participants lacking conclusive pathological diagnoses or complete survival data were excluded. A set of filtering criteria were applied to the initial group of patients, with the specific procedures outlined in a flowchart shown in Fig. 1. A range of factors were assessed, including age, gender, racial/ethnic origin, marital status, tumor stage, surgical intervention status, chemotherapy receipt, radiation status, OS, CSS, and follow-up period. The anatomical location of PGI-DLBCL was determined based on the “Primary Site - labeled” codes in the SEER database, with cases specifically categorized as stomach (C16.0–C16.9), small intestine (C17.0–C17.9), or colorectum (C18.0–C21.8) according to these codes. The X-tile software was used to determine the most appropriate age cutoff points, as illustrated in Fig. 2, resulting in the stratification of patients into three age brackets: ≤68 years, 69–80 years, and ≥ 81 years. Race was categorized as white, black, or a composite ‘others’ group encompassing American Indian/Alaska Native and Asian/Pacific Islander. Marital status was dichotomized into married versus unmarried, with the latter category encompassing divorced, separated, single, and widowed individuals. The study employed the “Lymphoma - Ann Arbor Stage” classification to evaluate the tumor stage. The objective of the study was to assess the clinicopathological characteristics and long-term prognosis of PGI-DLBCL affecting the stomach, small intestine, and colorectal regions. OS and CSS were measured from the date of PGI-DLBCL diagnosis until the occurrence of death, cancer-related mortality, or the end of follow-up, whichever occurred first. As the SEER database provides publicly accessible, anonymized data, the study proceeded without the necessity for Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval or informed consent.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study.

Fig. 2.

Age distribution at diagnosis in the SEER cohort of PGI-DLBCL patients, illustrated through an X-tile plot. (A) Area fill chart to determine the cut-off point for age; (B) Histogram to display the age distribution of patients in different groups; (C) Survival curve chart showing the survival time distribution across different groups. SEER: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; PGI-DLBCL: primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were summarized using frequency distributions with corresponding percentages, and chi-square tests were conducted to assess differences among groups. For non-normally distributed continuous variables, the median and interquartile range (IQR) were reported, and comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney U test. To enhance statistical reliability, particularly in handling missing data in the SEER dataset, a sophisticated approach combining multiple imputation (MI) with the random forest algorithm was implemented. Specifically, multiple imputed datasets were generated, and the random forest algorithm was applied to each dataset to account for the uncertainty introduced by missing values. Survival outcomes, including OS and CSS, were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences in survival distributions were evaluated with the log-rank test. Both univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were constructed to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and their associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Variables that achieved statistical significance (P < 0.05) in the univariate analysis were included in the subsequent multivariate Cox regression analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 4.1.0, with a significance level set at P < 0.05.

Results

Patients characteristics

A total of 10,935 patients were included in the study, with the stomach being the most frequent site (53.3%), followed by the small intestine (26.3%) and colorectum (20.5%). Of these, 6,577 (60.1%) were male and 4,358 (39.9%) were female. The predominant ethnic group was Caucasian, accounting for 81.0% of the patients. The treatment modalities included surgery for 1,394 cases (12.7%), chemotherapy for 4,251 cases (38.9%), radiotherapy for 153 cases (1.4%), a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy for 908 cases (8.3%), a combination of surgery and chemotherapy for 2,163 cases (19.8%), a combination of surgery and radiotherapy for 25 cases (0.2%), and a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy for 136 cases (1.2%). The median follow-up duration for the PGI-DLBCL cohort was 32.0 months (IQR: 4.0, 102.0). Gastric PGI-DLBCL patients exhibited a higher proportion of elderly individuals, females, and those with stage III/IV disease compared to patients with small intestine and colorectal DLBCL, and chemotherapy was the primary treatment modality. Table 1 provides an overview of the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with PGI-DLBCL involving the stomach, small intestine, and colorectum. Supplementary Table 1 offers a thorough examination of the patients’ demographic and clinical features prior to the occurrence of MI, with missing data reported for race (0.7% of cases), marital status (5.5%), tumor stage (30.1%), and surgical procedures (0.6% of cases).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with primary Gastrointestinal DLBCL.

| Variables | Total (n = 10,935) | Location | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stomach (n = 5823) | Small intestine (n = 2874) | Colorectum (n = 2238) | |||

| Age, years, n | < 0.001 | ||||

| ≤ 68 | 5051 (46.2%) | 2566 (44.1%) | 1409 (49.0%) | 1076 (48.1%) | |

| 69–80 | 3417 (31.2%) | 1856 (31.9%) | 880 (30.6%) | 681 (30.4%) | |

| ≥ 81 | 2467 (22.6%) | 1401 (24.1%) | 585 (20.4%) | 481 (21.5%) | |

| Sex, n | < 0.001 | ||||

| Male | 6577 (60.1%) | 3350 (57.5%) | 1815 (63.2%) | 1412 (63.1%) | |

| Female | 4358 (39.9%) | 2473 (42.5%) | 1059 (36.8%) | 826 (36.9%) | |

| Race, n | < 0.001 | ||||

| White | 8862 (81.0%) | 4582 (78.7%) | 2427 (84.4%) | 1853 (82.8%) | |

| Black | 748 (6.8%) | 466 (8.0%) | 155 (5.4%) | 127 (5.7%) | |

| Others | 1325 (12.1%) | 775 (13.3%) | 292 (10.2%) | 258 (11.5%) | |

| Marital status, n | 0.031 | ||||

| Married | 6289 (57.5%) | 3307 (56.8%) | 1713 (59.6%) | 1269 (56.7%) | |

| Unmarried | 4646 (42.5%) | 2516 (43.2%) | 1161 (40.4%) | 969 (43.3%) | |

| Stage, n | < 0.001 | ||||

| Stage I | 4221 (38.6%) | 2505 (43.0%) | 956 (33.3%) | 760 (34.0%) | |

| Stage II | 2881 (26.3%) | 919 (15.8%) | 1149 (40.0%) | 813 (36.3%) | |

| Stage III | 1369 (12.5%) | 928 (15.9%) | 275 (9.6%) | 166 (7.4%) | |

| Stage IV | 2464 (22.5%) | 1471 (25.3%) | 494 (17.2%) | 499 (22.3%) | |

| Treatment method, n | < 0.001 | ||||

| No therapy | 1905 (17.4%) | 1411 (24.2%) | 218 (7.6%) | 276 (12.3%) | |

| Surgery only | 1394 (12.7%) | 232 (4.0%) | 677 (23.6%) | 485 (21.7%) | |

| Chemotherapy only | 4251 (38.9%) | 2996 (51.5%) | 646 (22.5%) | 609 (27.2%) | |

| Radiation only | 153 (1.4%) | 119 (2.0%) | 13 (0.5%) | 21 (0.9%) | |

| Chemotherapy + Radiation | 908 (8.3%) | 738 (12.7%) | 78 (2.7%) | 92 (4.1%) | |

| Surgery + Chemotherapy | 2163 (19.8%) | 271 (4.7%) | 1190 (41.4%) | 702 (31.4%) | |

| Surgery + Radiation | 25 (0.2%) | 10 (0.2%) | 6 (0.2%) | 9 (0.4%) | |

| Surgery + Chemotherapy + Radiation | 136 (1.2%) | 46 (0.8%) | 46 (1.6%) | 44 (2.0%) | |

| Survival months, median (IQR) | 32.0 (4.0, 102.0) | 26.0 (3.0, 99.0) | 37.0 (6.0, 106.0) | 35.0 (5.0, 101.0) | < 0.001 |

PGI-DLBCL: primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; Others: American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian/Pacifc Islander; IQR: interquartile range; bold values indicate P < 0.05.

Survival analysis of patients with PGI-DLBCL

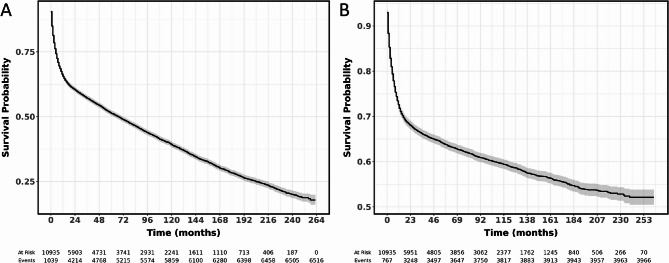

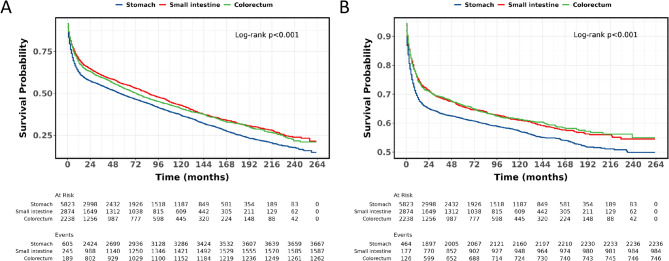

The 1, 3, 5, and 10-year OS rates for individuals with PGI-DLBCL were 65.6%, 57.1%, 51.3%, and 39.2% respectively, while the corresponding CSS rates for these periods were 71.8%, 66.0%, 63.5%, and 59.0%. For those with gastric DLBCL, the OS rates at 1, 3, 5, and 10 years were 62.4%, 54.5%, 48.8%, and 36.8% respectively, with CSS rates of 68.9%, 63.4%, 61.5%, and 57.1% for the same timeframes. Patients with small intestine DLBCL had OS rates of 70.1%, 60.7%, 55.4%, and 42.9% at 1, 3, 5, and 10 years respectively, and CSS rates of 75.5%, 68.7%, 65.6%, and 61.0% for these periods. In the case of colorectal DLBCL, the OS rates were 67.9%, 59.4%, 52.8%, and 40.8% at 1, 3, 5, and 10 years respectively, with CSS rates of 74.7%, 69.2%, 66.0%, and 61.3% for the same durations (Table 2). Figure 3A presents the OS for PGI-DLBCL patients, whereas Fig. 3B presents the CSS for PGI-DLBCL patients. Compared to gastric PGI-DLBCL, patients with small intestine and colorectal PGI-DLBCL exhibited significantly higher OS (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.77–0.87, P < 0.001; HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.80–0.91, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A) and CSS (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.78–0.90, P < 0.001; HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.76–0.90, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in OS and CSS between small intestine and colorectal PGI-DLBCL (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Overall survival and cancer-specific survival analysis in patients with primary Gastrointestinal DLBCL.

| Survival (%) | 95%CI lower | 95%CI upper | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | |||

| Primary gastrointestinal DLBCL (all) | |||

| 1-year | 65.6 | 64.7 | 66.5 |

| 3-year | 57.1 | 56.2 | 58.1 |

| 5-year | 51.3 | 50.4 | 52.3 |

| 10-year | 39.2 | 38.2 | 40.2 |

| Primary gastrointestinal DLBCL located in stomach | |||

| 1-year | 62.4 | 61.2 | 63.7 |

| 3-year | 54.5 | 53.2 | 55.8 |

| 5-year | 48.8 | 47.4 | 50.1 |

| 10-year | 36.8 | 35.4 | 38.2 |

| Primary gastrointestinal DLBCL located in small intestine | |||

| 1-year | 70.1 | 68.5 | 71.9 |

| 3-year | 60.7 | 58.9 | 62.6 |

| 5-year | 55.4 | 53.5 | 57.3 |

| 10-year | 42.9 | 40.9 | 45.1 |

| Primary gastrointestinal DLBCL located in colorectum | |||

| 1-year | 67.9 | 66.0 | 69.9 |

| 3-year | 59.4 | 57.3 | 61.5 |

| 5-year | 52.8 | 50.6 | 55.0 |

| 10-year | 40.8 | 38.5 | 43.2 |

| Cancer-specific survival | |||

| Primary gastrointestinal DLBCL (all) | |||

| 1-year | 71.8 | 70.9 | 72.7 |

| 3-year | 66.0 | 65.0 | 66.9 |

| 5-year | 63.5 | 62.5 | 64.5 |

| 10-year | 59.0 | 57.9 | 60.1 |

| Primary gastrointestinal DLBCL located in stomach | |||

| 1-year | 68.9 | 67.6 | 70.1 |

| 3-year | 63.4 | 62.1 | 64.7 |

| 5-year | 61.5 | 60.1 | 62.8 |

| 10-year | 57.1 | 55.7 | 58.6 |

| Primary gastrointestinal DLBCL located in small intestine | |||

| 1-year | 75.5 | 73.9 | 77.1 |

| 3-year | 68.7 | 67.0 | 70.5 |

| 5-year | 65.6 | 63.8 | 67.5 |

| 10-year | 61.0 | 59.0 | 63.1 |

| Primary gastrointestinal DLBCL located in colorectum | |||

| 1-year | 74.7 | 72.8 | 76.6 |

| 3-year | 69.2 | 67.2 | 71.2 |

| 5-year | 66.0 | 63.9 | 68.2 |

| 10-year | 61.3 | 59.0 | 63.7 |

DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; CI: confidence interval.

Fig. 3.

OS and CSS of patients with PGI-DLBCL. (A) OS; (B) CSS OS: overall survival; CSS: cancer-specific survival; PGI-DLBCL: primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Fig. 4.

OS and CSS were compared among gastric, small intestine, and colorectal PGI-DLBCL. (A) OS; (B) CSS. OS: overall survival; CSS: cancer-specific survival; PGI-DLBCL: primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression

Both univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses pinpointed age, sex, race, marital status, tumor stage, tumor location, and therapy method as predictors of poorer OS in patients with PGI-DLBCL (Table 3). Likewise, both analyses indicated that age, race, marital status, tumor stage, tumor location, and therapy method are associated with CSS in PGI-DLBCL patients (Table 4). To delve deeper into the prognostic factors impacting PGI-DLBCL patients based on tumor location, we performed further analyses on gastric, small intestine, and colorectal DLBCL. For gastric DLBCL, both univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses highlighted age, race, marital status, tumor stage, and therapy method as factors influencing OS (Supplementary Table 2). Similarly, both analyses underscored these same factors as influencing CSS (Supplementary Table 3). In the case of small intestine DLBCL, the univariate analysis pointed to age, marital status, tumor stage, and therapy method as OS risk factors. However, the multivariate analysis identified age, tumor stage, and therapy method as independent predictors of OS (Supplementary Table 4). Moreover, both analyses agreed that age, marital status, tumor stage, and therapy method are linked to CSS (Supplementary Table 5). For colorectal DLBCL, the univariate analysis linked age, race, marital status, tumor stage, and therapy method to OS. Nevertheless, the multivariate analysis revealed age, race, tumor stage, and therapy method as independent OS predictors (Supplementary Table 6). The univariate analysis associated age, marital status, tumor stage, and therapy method with CSS, while the multivariate analysis confirmed age, tumor stage, and therapy method as independent CSS predictors (Supplementary Table 7).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression for analyzing the overall survival for patients with primary Gastrointestinal DLBCL.

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age, years | ||||||

| ≤ 68 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| 69–80 | 2.39 | 2.25, 2.53 | < 0.001 | 2.39 | 2.25, 2.54 | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 81 | 4.67 | 4.39, 4.98 | < 0.001 | 4.07 | 3.81, 4.35 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Female | 1.05 | 1.00, 1.11 | 0.045 | 0.83 | 0.79, 0.87 | < 0.001 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Black | 1.04 | 0.95, 1.15 | 0.389 | 1.29 | 1.17, 1.42 | < 0.001 |

| Others | 0.84 | 0.77, 0.90 | < 0.001 | 0.93 | 0.86, 1.01 | 0.097 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Unmarried | 1.37 | 1.30, 1.44 | < 0.001 | 1.26 | 1.20, 1.33 | < 0.001 |

| Stage | ||||||

| Stage I | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Stage II | 1.09 | 1.03, 1.95 | < 0.001 | 1.31 | 1.22, 1.40 | < 0.001 |

| Stage III | 1.24 | 1.07, 2.02 | < 0.001 | 1.33 | 1.19, 1.44 | < 0.001 |

| Stage IV | 2.02 | 1.91, 2.15 | < 0.001 | 2.66 | 2.50, 2.83 | < 0.001 |

| Location | ||||||

| Stomach | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Small intestine | 0.82 | 0.77, 0.87 | < 0.001 | 0.91 | 0.88, 0.98 | 0.021 |

| Colorectum | 0.86 | 0.80, 0.91 | < 0.001 | 0.89 | 0.82, 0.95 | < 0.001 |

| Treatment method | ||||||

| No therapy | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Surgery only | 0.66 | 0.61, 0.71 | < 0.001 | 0.72 | 0.66, 0.78 | < 0.001 |

| Chemotherapy only | 0.36 | 0.34, 0.38 | < 0.001 | 0.37 | 0.34, 0.40 | < 0.001 |

| Radiation only | 0.81 | 0.67, 0.97 | 0.023 | 0.71 | 0.59, 0.85 | < 0.001 |

| Chemotherapy + Radiation | 0.27 | 0.24, 0.30 | < 0.001 | 0.35 | 0.31, 0.39 | < 0.001 |

| Surgery + Chemotherapy | 0.26 | 0.24, 0.28 | < 0.001 | 0.31 | 0.28, 0.34 | < 0.001 |

| Surgery + Radiation | 0.68 | 0.44, 1.04 | 0.076 | 0.49 | 0.32, 0.75 | 0.001 |

| Surgery + Chemotherapy + Radiation | 0.28 | 0.22, 0.36 | < 0.001 | 0.38 | 0.30, 0.48 | < 0.001 |

DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; HR: hazard ratios; CI: confidence interval; Others: American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian/Pacifc Islander; bold values indicate P < 0.05.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression for analyzing the cancer-specific survival for patients with primary Gastrointestinal DLBCL.

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age, years | ||||||

| ≤ 68 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| 69–80 | 1.87 | 1.73, 2.02 | < 0.001 | 1.83 | 1.69, 1.98 | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 81 | 3.62 | 3.35, 3.91 | < 0.001 | 2.93 | 2.70, 3.19 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1 | Reference | - | - | - | |

| Female | 1.05 | 0.99, 1.12 | 0.131 | - | - | - |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Black | 1.16 | 1.03, 1.30 | 0.016 | 1.32 | 1.17, 1.49 | < 0.001 |

| Others | 0.91 | 0.82, 1.00 | 0.051 | 1.02 | 0.93, 1.13 | 0.645 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Unmarried | 1.45 | 1.36, 1.54 | < 0.001 | 1.25 | 1.17, 1.33 | < 0.001 |

| Stage | ||||||

| Stage I | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Stage II | 1.10 | 1.01, 1.20 | 0.039 | 1.69 | 1.49, 1.92 | < 0.001 |

| Stage III | 1.98 | 1.87, 2.10 | 0.006 | 1.73 | 1.58, 1.90 | < 0.001 |

| Stage IV | 3.15 | 2.92, 3.40 | < 0.001 | 4.35 | 4.02, 4.71 | < 0.001 |

| Location | ||||||

| Stomach | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Small intestine | 0.84 | 0.78, 0.90 | < 0.001 | 0.93 | 0.81, 0.98 | 0.022 |

| Colorectum | 0.83 | 0.76, 0.90 | < 0.001 | 0.86 | 0.78, 0.94 | < 0.001 |

| Treatment method | ||||||

| No therapy | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Surgery only | 0.57 | 0.52, 0.63 | < 0.001 | 0.62 | 0.56, 0.69 | < 0.001 |

| Chemotherapy only | 0.31 | 0.29, 0.34 | < 0.001 | 0.29 | 0.26, 0.31 | < 0.001 |

| Radiation only | 0.76 | 0.61, 0.95 | 0.014 | 0.71 | 0.57, 0.88 | 0.002 |

| Chemotherapy + Radiation | 0.22 | 0.19, 0.25 | < 0.001 | 0.28 | 0.25, 0.33 | < 0.001 |

| Surgery + Chemotherapy | 0.22 | 0.20, 0.25 | < 0.001 | 0.24 | 0.21, 0.27 | < 0.001 |

| Surgery + Radiation | 0.51 | 0.29, 0.90 | 0.021 | 0.37 | 0.21, 0.66 | < 0.001 |

| Surgery + Chemotherapy + Radiation | 0.28 | 0.21, 0.38 | < 0.001 | 0.33 | 0.25, 0.45 | < 0.001 |

DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; HR: hazard ratios; CI: confidence interval; Others: American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian/Pacifc Islander; bold values indicate P < 0.05.

Survival analysis of PGI-DLBCL patients treated with different therapeutic approaches

Treatment approach is a key determinant affecting the outcome of patients with PGI-DLBCL. Hence, we assessed the OS and CSS rates of DLBCL patients with tumors in the stomach, small intestine, and colorectum based on various treatment strategies. Our findings indicated that for gastric DLBCL, treatment modalities including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy each led to better patient outcomes compared to no treatment. Notably, the combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy proved to be the most effective in enhancing OS and CSS, with HRs and 95% CIs for OS and CSS being 0.26 (0.23–0.29), P < 0.001 and 0.21 (0.17–0.24), P < 0.001, respectively, as illustrated in Fig. 5A and B. However, for small intestine DLBCL, the combination of surgery and chemotherapy yielded the greatest improvement in prognosis compared to no treatment, with HRs (95% CIs) for OS and CSS being 0.26 (0.22–0.31), P < 0.001 and 0.22 (0.18–0.27), P < 0.001, respectively, as depicted in Fig. 5C and D. In the case of colorectal DLBCL, patients who received both surgery and chemotherapy exhibited a better prognosis compared to those who underwent other treatment modalities or received no treatment at all, as shown in Fig. 5E and F.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of prognoses for different treatment modalities across different sites. (A) OS in stomach; (B) CSS in stomach; (C) OS in small intestine; (D) CSS in small intestine; (E) OS in colorectum; (F) CSS in colorectum.

Discussion

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive location-specific analysis of the clinicopathological characteristics and long-term prognosis of PGI-DLBCL utilizing data from the SEER database. Our findings revealed that gastric PGI-DLBCL was the most prevalent, accounting for 53.3% of cases, followed by the small intestine (26.3%) and colorectum (20.5%). Notably, gastric PGI-DLBCL patients exhibited distinct clinicopathological features, including a higher proportion of elderly and female patients, as well as a greater incidence of stage III/IV disease, predominantly managed with chemotherapy. In comparison, patients with small intestine and colorectal PGI-DLBCL demonstrated significantly better OS and CSS than those with gastric PGI-DLBCL. Interestingly, OS and CSS were comparable between small intestine and colorectal PGI-DLBCL. Five-year OS rates were 48.8%, 55.4%, and 52.8% for stomach, small intestine, and colorectum, respectively, with corresponding CSS rates of 61.5%, 65.6%, and 66.0%. Furthermore, multivariate Cox regression analysis identified age, race, marital status, tumor stage, location, and treatment as independent risk factors for both OS and CSS. Radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy emerged as the most potent therapeutic approach for enhancing the prognosis of gastric DLBCL, whereas for small intestine and colorectal DLBCL, the combination of surgery and chemotherapy proved to be the most effective in improving patient outcomes. These findings highlight the heterogeneity in clinicopathological features and prognosis of PGI-DLBCL based on tumor location and underscore the importance of considering these factors in the management of this disease.

The gastrointestinal tract stands as the most prevalent extranodal site involved in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), constituting approximately 10-15% of all NHL cases and 30-40% of all extranodal lymphomas1,10,11. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma (PGIL) is a relatively rare entity, accounting for only 3-4% of all gastrointestinal malignancies12,13. Notably, the stomach is the primary site for PGIL, constituting 60–77% of all cases. It is succeeded by the small intestine (20-30%) and the colon (0.2–5.1%), with DLBCL serving as the most frequent histological subtype14–16. Our study corroborates these findings, revealing that the stomach is also the primary site of involvement in primary gastric DLBCL, trailed by the small intestine and colorectum.

Lewis et al.6 conducted a retrospective analysis of 37 patients with early-stage, localized stage I PGI-DLBCL diagnosed across multiple centers between 2006 and 2018. Their findings underscored chemotherapy as the cornerstone of treatment for gastric DLBCL patients, with 91.9% receiving the rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) regimen. The 4-year progression-free survival (PFS) and OS rates for this regimen were impressive, at 88% (95% CI: 71–95) and 91% (95% CI: 75–97), respectively. Our study echoes these observations, with chemotherapy emerging as the primary therapeutic modality for gastric DLBCL patients. Nonetheless, it is important to note the limitations of our study, including its small sample size and exclusive focus on stage I patients. In an effort to elucidate the prognostic factors influencing gastric DLBCL outcomes, Bardakci et al.7 analyzed data from 91 patients from a single center. Their findings identified age and the International Prognostic Index (IPI) as independent prognostic factors. Similarly, Lin et al.17 constructed a predictive model for CSS based on SEER database data from 2,547 gastric DLBCL patients. Their model highlighted tumor stage, age, surgery, and chemotherapy as significant risk factors impacting CSS.

Our study further substantiates the critical role of age as a prognostic factor in gastric DLBCL, with older patients exhibiting a less favorable prognosis. This disparity may stem from the decline in physical function observed in elderly patients, coupled with their diminished tolerance to the R-CHOP chemotherapy regimen. Additionally, the biological characteristics of DLBCL, which can be categorized into germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) and activated B-cell-like (ABC) subtypes, may also contribute to this prognostic discrepancy. Studies have consistently demonstrated that patients harboring the ABC subtype tend to have a poorer prognosis18,19. Intriguingly, the proportion of the ABC subtype within DLBCL may increase with advancing age, potentially explaining the poorer prognosis observed in elderly patients. Furthermore, our study revealed that both surgery and chemotherapy hold promise in improving the prognosis of PGI-DLBCL patients. Notably, patients receiving a combination of surgery and chemotherapy exhibited a more favorable prognosis compared to those undergoing single surgery or single chemotherapy. This advantage may be attributed to the comprehensive nature of the combined treatment approach, which more effectively eradicates tumor cells, reduces the risk of recurrence and metastasis, enhances treatment tolerance, provides accurate information for pathological classification and clinical staging, exerts synergistic effects of chemotherapy drugs, and minimizes the occurrence of complications. Ultimately, these factors collectively contribute to the comprehensive improvement of treatment efficacy and prognosis in PGI-DLBCL patients.

In the current literature, numerous studies have leveraged the SEER database to elucidate the clinical characteristics and prognostic outcomes of patients with DLBCL arising in the small intestine or colon. Liu et al.8, for instance, conducted a comprehensive analysis of the clinical features and long-term prognosis of patients with small intestine DLBCL, integrating data from both the SEER database and their own institutional records. Similarly, Wang et al.20 utilized the SEER database to investigate the risk factors that influence the prognosis of patients with DLBCL of the small intestine and colon. Furthermore, several other studies have focused on the clinical features and prognosis of patients with DLBCL of the colon and cecum9,21,22. In addition to these efforts, previous research has delved into the risk factors affecting the prognosis of patients with PGI-DLBCL, identifying potential associations with prognostic indicators such as the inflammation response index (SIRI), lymphocyte-monocyte ratio (LMR), platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and metabolic tumor volume (MTV)23–25. Despite these advancements, however, the relationship between tumor location and the prognosis of PGI-DLBCL remains poorly defined. The incidence of PGI-DLBCL varies across different anatomical sites, and clinical manifestations, as well as subtle differences in tumor cell morphology and immunophenotype, may also differ accordingly.

Previous studies have suggested that the prognosis of gastric DLBCL may be more favorable than that of small intestine or colorectal DLBCL, potentially owing to earlier detection of gastric tumors, higher surgical resection rates, and enhanced patient responsiveness to treatment6,7,17. In contrast, our study revealed that the prognosis of gastric DLBCL was inferior to that of small intestine and colorectal DLBCL. We hypothesize that this discrepancy may be partly attributed to differences in the study population and sample size. Specifically, our study cohort included a higher proportion of elderly patients with gastric DLBCL, and a greater percentage of these patients presented with tumor stage III/IV. Moreover, 24.2% of patients did not undergo surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy, which may have contributed to the poorer prognostic outcomes observed in this subset of patients compared to those with small intestine and colorectal DLBCL. This finding holds significant clinical importance, as it underscores the prognostic significance of tumor location in PGI-DLBCL. The superior survival outcomes observed in patients with small intestine and colorectal PGI-DLBCL may be attributable to earlier diagnosis, more favorable tumor biology, or differences in treatment response. Notably, OS and CSS were comparable between patients with small intestine and colorectal PGI-DLBCL, suggesting that these two sites may share similar prognostic features. These insights warrant further investigation to better understand the underlying mechanisms driving the prognostic differences observed across various anatomical sites of PGI-DLBCL.

In our study, we found that marital status significantly influences survival outcomes in PGI-DLBCL, with married patients exhibiting a superior prognosis compared to unmarried individuals. This disparity may arise from the synergistic effects of social support, access to healthcare, lifestyle behaviors, and psychological well-being. Social support from spouses enhances treatment adherence and facilitates early symptom recognition, enabling timely medical intervention, which is critical in aggressive lymphomas like PGI-DLBCL26. Married patients are more likely to receive guideline-recommended therapies, as spousal advocacy improves their ability to navigate complex healthcare systems and allocate financial resources effectively27. Lifestyle factors also contribute to this disparity. Unmarried individuals exhibit higher rates of adverse health behaviors, including smoking and poor dietary habits, which may exacerbate metabolic dysregulation linked to PGI-DLBCL progression. Conversely, married patients often adopt healthier lifestyles due to the influence of their spouses, potentially mitigating tumor-associated metabolic perturbations. Psychologically, marital relationships serve as a buffer against stress and reduce anxiety or depression, factors known to impair immune function and correlate with poorer lymphoma outcomes. A population-based study of lymphoma patients confirmed that unmarried status independently predicted worse survival, even after adjusting for clinical stage and comorbidities28. These findings underscore the importance of integrating psychosocial support into holistic care models for PGI-DLBCL patients, particularly those lacking spousal companionship.

Our findings revealed that a greater percentage of patients with small intestine and colorectal DLBCL received surgical treatment compared to those with gastric DLBCL. Small intestine and colorectal DLBCL often present acutely with life-threatening complications, such as obstruction, perforation, or hemorrhage, necessitating emergency surgical intervention for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes29–31. For instance, previous studies32,33 have demonstrated that 11–19% of primary intestinal DLBCL cases present with perforation at diagnosis, and surgical resection is frequently required to manage these complications. Furthermore, intestinal lymphomas are more likely to manifest as localized lesions, such as ileocecal masses, which are technically amenable to complete resection29. Prior research supports that complete surgical resection of localized intestinal DLBCL, followed by abbreviated chemotherapy courses, yields excellent outcomes. This is because surgery not only removes the bulk tumor but also mitigates the risk of chemotherapy-induced perforation33,34.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, the retrospective extraction of data from the SEER database may introduce inherent biases and incomplete information. Secondly, while the SEER database provides a large, population-based sample, it lacks granular clinical details (e.g., specific chemotherapy protocols, comorbidity profiles, performance status, and treatment-related adverse events). Consequently, the observed survival differences in PGI-DLBCL may be influenced by unmeasured confounding factors affecting treatment selection or patient characteristics. Prospective studies incorporating detailed clinical and molecular data are required to validate these findings and elucidate the mechanisms underlying site-specific outcomes. Thirdly, although we identified independent prognostic factors for OS and CSS, the study may not have accounted for all potential confounders that could impact PGI-DLBCL prognosis. Finally, the generalizability of our results may be restricted to the population represented in the SEER database, necessitating further validation in diverse patient cohorts. Despite these limitations, our study offers valuable insights into the clinicopathological features and long-term prognosis of PGI-DLBCL across different anatomical sites.

In conclusion, this study highlights distinct clinicopathological features and prognostic variations among gastric, small intestine, and colorectal PGI-DLBCL. Site-specific differences in survival and treatment efficacy are evident. Future research should explore underlying mechanisms and validate optimal treatment protocols for each location. Tailored management strategies may improve outcomes for PGI-DLBCL patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Yunfu Feng wrote the main manuscript text, Sijie Zheng prepared figures and tables, Yibin Sun and Luojie Liu managed this project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Changshu Science and Technology Program (CY202339), the Suzhou Youth Science and Technology Project for the Advancement of Science, Education, and Health (KJXW2023067), and the Suzhou 23rd Batch of Science and Technology Development Plan (Clinical Trial Institution Capability Enhancement) Project (SLT 2023006).

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found here: https://seer.cancer.gov/. The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ghimire, P., Wu, G. Y. & Zhu, L. Primary Gastrointestinal lymphoma. World J. Gastroenterol.17 (6), 697–707. 10.3748/wjg.v17.i6.697 (2011). PMID: 21390139; PMCID: PMC3042647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen, X. et al. Primary intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: novel insights and clinical perception. Front. Oncol.14, 1404298. 10.3389/fonc.2024.1404298 (2024). PMID: 39211552; PMCID: PMC11357906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olszewska-Szopa, M. & Wróbel, T. Gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Adv Clin Exp Med. ;28(8):1119–1124. (2019). 10.17219/acem/94068. PMID: 31414733. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Álvarez Martínez, P. et al. Primary esophageal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Rev. Esp. Enferm Dig.115 (7), 400–401. 10.17235/reed.2022.9298/2022 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarez-Lesmes, J. et al. Gastrointestinal Tract Lymphomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. ;145(12):1585–1596. (2021). 10.5858/arpa.2020-0661-RA. PMID: 33836528. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Lewis, C. S. et al. Primary gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A multicentre retrospective study. Br. J. Haematol.205 (2), 534–541. 10.1111/bjh.19470 (2024). Epub 2024 Apr 17. PMID: 38632873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bardakci, M. et al. Evaluation of clinical and prognostic factors for primary gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: single-center experience. J Cancer Res Ther. 2023 Apr-Jun;19(3):778–782. 10.4103/jcrt.jcrt_2111_21. PMID: 37470610. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Liu, X. et al. Clinical features analysis and survival nomogram of primary small intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Manag Res.14, 2639–2648. 10.2147/CMAR.S369086 (2022). PMID: 36090469; PMCID: PMC9462437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma, B. et al. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the descending Colon. Am. J. Med. Sci.358 (2), 164–167. 10.1016/j.amjms.2019.05.004 (2019). Epub 2019 May 23. PMID: 31331454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.d’Amore, F. et al. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a population-based analysis of incidence, geographic distribution, clinicopathologic presentation features, and prognosis. Danish Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. ;12(8):1673-84. (1994). 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.8.1673. PMID: 8040680. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Bautista-Quach, M. A. et al. Gastrointestinal lymphomas: morphology, immunophenotype and molecular features. J. Gastrointest. Oncol.3 (3), 209–225. 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2012.024 (2012). PMID: 22943012; PMCID: PMC3418529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwamuro, M. et al. Recent updates on treatment options for primary follicular lymphoma of the Gastrointestinal tract. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.18 (7), 367–375 (2024). Epub 2024 Jul 15. PMID: 38997226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, L. et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors of primary Gastrointestinal lymphoma. Asian J. Surg.47 (5), 2255–2256. 10.1016/j.asjsur.2024.01.142 (2024). Epub 2024 Feb 16. PMID: 38368150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu, P. et al. Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors for primary pediatric and adolescent non-Hodgkin lymphomas of the gastrointestinal tract: a population-based study. World J. Surg. Oncol.21 (1), 353. 10.1186/s12957-023-03238-9 (2023). PMID: 37968641; PMCID: PMC10647069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickson, B. C., Serra, S. & Chetty, R. Primary gastrointestinal tract lymphoma: diagnosis and management of common neoplasms. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 6(11):1609-28. (2006). 10.1586/14737140.6.11.1609. PMID: 17134365. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Nagakita, K. et al. Clinicopathological features of 49 primary Gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cases; comparison with location, cell-of-origin, and frequency of MYD88 L265P. Pathol. Int.66 (8), 444–452. 10.1111/pin.12439 (2016). Epub 2016 Jul 20. PMID: 27439595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin, J. L. et al. Dynamic prediction of long-term survival in patients with primary gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a SEER population-based study. BMC Cancer. 19 (1), 873. 10.1186/s12885-019-5993-6 (2019). PMID: 31481021; PMCID: PMC6724291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmitz, R. et al. Genetics and pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl. J. Med.378 (15), 1396–1407. 10.1056/NEJMoa1801445 (2018). PMID: 29641966; PMCID: PMC6010183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson, W. H. et al. Effect of ibrutinib with R-CHOP chemotherapy in genetic subtypes of DLBCL. Cancer Cell.39 (12), 1643–1653e3. 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.10.006 (2021). Epub 2021 Nov 4. PMID: 34739844; PMCID: PMC8722194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang, Y. et al. A visual model for prognostic estimation in patients with primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of small intestine and colon: analysis of 1,613 cases from the SEER database. Transl Cancer Res.10 (4), 1842–1855. 10.21037/tcr-20-3086 (2021). PMID: 35116506; PMCID: PMC8798054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erginoz, E. et al. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the sigmoid colon. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep.87, 106454. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2021.106454 (2021). Epub 2021 Sep 28. PMID: 34600235; PMCID: PMC8488484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravilla, J. et al. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the Colon presenting as idiopathic thrombocytopenia: a case report. J. Community Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect.14 (1), 75–79. 10.55729/2000-9666.1284 (2024). PMID: 38482079; PMCID: PMC10932509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu, Y. et al. Prognosis and complications of patients with primary Gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: development and validation of the systemic inflammation response index-covered score. Cancer Med.12 (8), 9570–9582. 10.1002/cam4.5733 (2023). Epub 2023 Mar 3. PMID: 36866830; PMCID: PMC10166949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao, P. et al. The Lymphocyte-Monocyte ratio and the Platelet-Lymphocyte ratio at diagnosis as independent prognostic factors in primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Indian J. Hematol. Blood Transfus.33 (3), 333–341. 10.1007/s12288-016-0720-9 (2017). Epub 2016 Aug 29. PMID: 28824234; PMCID: PMC5544629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song, M. K. et al. Prognostic value of metabolic tumor volume on PET / CT in primary Gastrointestinal diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cancer Sci.103 (3), 477–482. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02164.x (2012). Epub 2012 Jan 16. PMID: 22126515; PMCID: PMC7716280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang, T. et al. The influence of marital status at diagnosis on survival of adult patients with mantle cell lymphoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol.150 (3), 120. 10.1007/s00432-024-05647-z (2024). PMID: 38466431; PMCID: PMC10927831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, S. et al. Marital status, living arrangement, and Cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III Colon cancer: findings from CALGB 89803 (Alliance). Oncologist27 (6), e494–e505. 10.1093/oncolo/oyab070 (2022). PMID: 35641198; PMCID: PMC9177101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zou, G. et al. Marital status independently predicts the overall survival in young adult patients with lymphoma: a population-based, propensity-matched study. Med. (Baltim).102 (36), e34416. 10.1097/MD.0000000000034416 (2023). PMID: 37682153; PMCID: PMC10489250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iida, T. et al. Upfront surgery for small intestinal non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Anticancer Res.40(4), 2373–2377. (2020). 10.21873/anticanres.14206. PMID: 32234940. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Svetlana, S., Liliya, K. & Vesela, K. Diffuse B cell large ileal lymphoma presenting with obstruction and associated with hashimoto’s thyroiditis. J. Surg. Case Rep.2025 (4), rjaf253. 10.1093/jscr/rjaf253 (2025). PMID: 40297716; PMCID: PMC12036825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wienerroither, V. et al. Operative R0 resection of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the pelvis: a case report. J. Med. Case Rep.12 (1), 293. 10.1186/s13256-018-1838-1 (2018). PMID: 30314526; PMCID: PMC6186087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu, Y. H. et al. Primary intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in Taiwan showed a relative higher rate of perforation and EBV association. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol.24(8):541-9. (2016). 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000226. PMID: 26258754. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Lu, P. W. et al. Surgical management of small bowel lymphoma. J. Gastrointest. Surg.25 (3), 757–765. 10.1007/s11605-020-04730-3 (2021). Epub 2020 Jul 14. PMID: 32666499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shu, Y. et al. Surgery plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in primary intestinal lymphoma: a meta-analysis. J. Int. Med. Res.49 (11), 3000605211056845. 10.1177/03000605211056845 (2021). PMID: 34763562; PMCID: PMC8593296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found here: https://seer.cancer.gov/. The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.