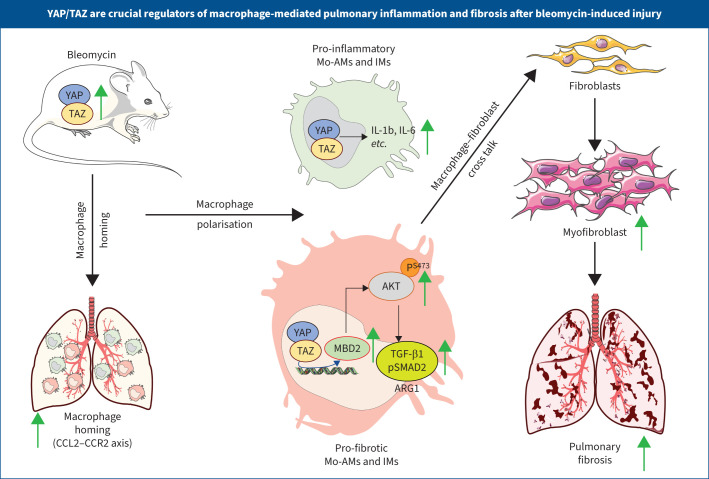

Graphical abstract

Overview of the study. Mo-AM: monocyte-derived alveolar macrophage; IM: interstitial macrophage; IL: interleukin; CCL: C-C motif chemokine ligand; CCR: C-C motif chemokine receptor; MBD: methyl-CpG–binding domain; TGF: transforming growth factor.

Abstract

Pulmonary fibrosis is the most prevalent and severe form of end-stage interstitial lung disease. Macrophages are crucial players in inflammation-induced pulmonary fibrosis, but the mechanisms driving macrophage polarisation and their specific roles in pulmonary fibrosis pathogenesis remain poorly understood. Here, we demonstrate that both YAP and TAZ are activated in lung macrophages from patients with pulmonary fibrosis as well as in mice with bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Myeloid-specific Yap/Taz deletion resulted in reduced recruitment of monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages (Mo-AMs), impaired inflammatory responses, decreased pulmonary fibrosis and enhanced alveolar epithelial cell regeneration following bleomycin treatment. Conversely, the expression of a constitutively active YAP mutant (YAP5SA) exacerbated bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by increasing Mo-AM recruitment, elevating expression of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic markers, and impairing alveolar epithelial cell regeneration. We demonstrate that YAP/TAZ-CCL2 (C-C motif chemokine ligand 2) signalling plays a crucial role in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, as blocking CCL2 with a neutralising antibody effectively abrogated the YAP5SA-induced recruitment of Mo-AMs, inflammatory and fibrotic responses. Additionally, we reveal that the YAP/TAZ-MBD2-TGFβ1-pSMAD2 signalling axis is crucial not only for pro-fibrotic macrophage polarisation, but also for their cross-talk with lung fibroblasts, driving the fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition. Collectively, these findings suggest that targeting aberrant YAP/TAZ activity to modulate inflammatory and fibrotic response could be a promising strategy for the prevention and treatment of pulmonary fibrosis.

Shareable abstract

Targeting the Hippo-pathway effectors YAP/TAZ could be viable therapeutic approaches for the prevention and treatment of pulmonary fibrosis https://bit.ly/4fPISXQ

Introduction

Pulmonary fibrosis is a chronic and progressive interstitial lung disease characterised by persistent inflammation and scarring of lung tissue. This condition involves the excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) between the alveoli or air sacs, leading to the destruction of lung parenchyma. The progressive fibrosis impairs oxygen exchange, resulting in breathlessness and ultimately, organ failure. Pulmonary fibrosis can be triggered by various factors including ageing, genetic disorders, autoimmune diseases, radiation, environmental exposures, and more recently, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection [1–3]. When the underlying cause of pulmonary fibrosis is unknown, it is termed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). IPF is a progressive lung disease with a complex and poorly understood pathophysiology, primarily affecting older adults. The median survival after an IPF diagnosis is typically 2–5 years [4]. Despite the increasing number of IPF cases, the underlying pathological mechanisms driving the disease remain elusive.

Growing evidence suggests that macrophages play a critical role in regulating pulmonary fibrosis. In the lung, two major populations of macrophages have been identified: alveolar macrophages (AMs) and interstitial macrophages (IMs). These macrophages are crucial for initiating innate immune responses and for clearing the airways of pathogenic microbes, apoptotic cells, debris and other pollutants through phagocytosis [5, 6]. Following lung injury, both AM and IM populations are expanded. Studies suggest that circulating monocytes are a primary source of newly derived macrophages, which play a crucial role in inflammation and various stages of fibrosis by secreting pro-fibrotic factors [7–10]. Studies suggest that both reduced and excessive inflammatory responses can adversely impact lung fibrosis [11–13]. For instance, nonselective depletion of both tissue-resident alveolar macrophages (TR-AMs) and monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages (Mo-AMs) can exacerbate the fibrotic response by promoting additional recruitment of monocytes, disrupting tissue homeostasis [12, 13]. Similarly, persistent chronic inflammation can exacerbate the fibrotic response [11]. Therefore, understanding the regulatory mechanisms and pro-inflammatory behaviours of distinct macrophage subpopulations is crucial for addressing the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis/IPF.

We have demonstrated that Yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ), key transcriptional regulators in the Hippo signalling pathway, play crucial roles in modulating immune responses by affecting both immune and nonimmune cells [14–17]. For example, macrophage-specific deletion of YAP/TAZ improved cardiac remodelling and function following myocardial infarction, primarily due to a reduction in inflammation-driven cardiac fibrosis [18]. Building on these findings, we hypothesised that YAP/TAZ might similarly regulate the phenotypic and functional characteristics of AMs and IMs at different stages of lung injury, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis/IPF.

In this study, we discovered that both YAP and TAZ are activated in lung macrophages from human patients with pulmonary fibrosis and in mice subjected to bleomycin-induced lung injury. Genetic inactivation of Yap/Taz resulted in a reduced population of Mo-AMs and IMs in bleomycin-treated lungs. This genetic alteration also led to a decrease in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and pro-fibrotic markers, culminating in reduced fibrosis in the lungs. Notably, this reduction in fibrosis was associated with improved alveolar epithelial regeneration in the Yap/Taz knockout mice. Conversely, a gain-of-function experiment using a constitutively active YAP mutant (YAP5SA) worsened bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. This exacerbation was largely due to an increased influx of Mo-AMs, elevated levels of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic markers, and impaired alveolar epithelial regeneration. We found that the YAP/TAZ-CCL2 (C-C motif chemokine ligand 2) signalling pathway plays a crucial role in pulmonary fibrosis, as blocking CCL2 with a neutralising antibody effectively prevented the YAP5SA-induced recruitment of Mo-AMs and mitigated the inflammatory and fibrotic responses following bleomycin injury. Furthermore, our findings indicate that the YAP/TAZ-MBD2-TGFβ1-pSMAD2 signalling axis is critical not only for the polarisation of pro-fibrotic macrophages, but also for their cross-talk with lung fibroblasts, driving the fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition. Collectively, our data suggest that targeting YAP/TAZ could offer a promising therapeutic strategy for the prevention and treatment of pulmonary fibrosis.

Materials and methods

Details of the materials and methods used can be found in the supplementary material.

Results

YAP/TAZ are activated in lung macrophages of pulmonary fibrotic patients and bleomycin-treated mice

To investigate whether YAP and TAZ are activated in macrophages under pathological fibrotic conditions, we examined their presence and activity in healthy and fibrotic adult human lungs. Immunofluorescence analysis of healthy and fibrotic lung sections revealed a notable increase in the abundance of CD68-positive (CD68+) macrophages in fibrotic lung tissues expressing collagen type I (collagen I), compared to healthy adult lung (supplementary figure S1). Moreover, YAP and TAZ proteins were detected in the nuclei of CD68+ macrophages, with a notable increase in YAP/TAZ expression in macrophages from fibrotic lungs relative to those from healthy lungs (figure 1a and b). To understand the macrophage-specific roles of YAP/TAZ in bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis, we analysed their expression in mice 7 days after intratracheal bleomycin administration. Immunohistological analysis of lung sections revealed an increased nuclear presence of YAP and TAZ in CD68+ macrophages from bleomycin-treated mice compared to saline-treated control mice (figure 1c and d). We observed elevated mRNA levels of Yap and Taz, along with their target gene connective tissue growth factor (Ctgf), and pro-inflammatory macrophage markers interleukin-6 (Il6), interleukin-1β (Il1β), and tumour necrosis factor-α (Tnfα) in lung macrophages identified as 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Dapi−)CD45+Ly6G−CD64+CD11b+ cells, obtained through fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) 7 days after bleomycin instillation (figure 1e–g). We further confirmed that Yap, Taz and CTGF protein expression was increased in primary human lung macrophages treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and in sorted primary lung macrophages from bleomycin-treated control and Yap/Taz double knockout (dKO) mice at different time points (figure 1h and i). These preliminary observations suggest that YAP/TAZ may contribute to lung macrophage function in response to injury.

FIGURE 1.

YAP/TAZ are activated in lung macrophages. a, b) Immunofluorescence staining and quantification of YAP or TAZ co-stained with CD68 on lung sections from human patients diagnosed with pulmonary fibrosis and compared with normal adult human (considered as healthy adult) lung (n=3). c, d) Immunofluorescence staining and quantification of YAP or TAZ co-stained with CD68 in wild-type mouse lung sections at 7 days (D7) post-bleomycin injury compared to saline-treated sham controls (n=5). e, f) Gating strategy and quantification of flow cytometry analysis to sort the total lung macrophages (identified as Dapi−CD45+Ly6G−CD64+CD11b+ cells) using saline-treated sham controls (n=5) and bleomycin-treated mice (n=5) at 7 days. g) Real-time quantitative PCR analysis of Yap, Taz, Ctgf, Il6, Il1β and Tnfα on sorted total lung macrophages. h) Immunoblot analysis of YAP, TAZ and CTGF on primary human lung macrophages treated with saline or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (100 ng·mL−1) for 12 h (n=3). Quantification of indicated proteins relative to vinculin. i) Immunoblot analysis of YAP and TAZ using cultured primary lung macrophages isolated through flow cytometry (identified as Dapi−CD45+Ly6G–CD64+CD11b+ cells) on saline- or bleomycin-treated control and Yap/Taz double knockout (dKO) mice (n=5) as indicated time points. Quantification of indicated proteins relative to β-actin. SSC: side scatter; FSC: forward scatter; A: area; W: width; H: height; Dapi: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; D7: day 7; D14: day 14; Ctgf: connective tissue growth factor; Il: interleukin; TNF: tumour necrosis factor. Data are presented as mean±sem; comparison by two-tailed unpaired t-test. Significance levels are indicated with p-value (significant at p<0.05). *: p<0.05; ***: p<0.001.

Inactivation of Yap/Taz impairs bleomycin-induced inflammation in the lung

In various biological contexts, YAP and TAZ often exhibit redundant functions, including in macrophages [18–23]. However, their context-specific, nonredundant roles cannot be ruled out [24]. To examine the role of YAP/TAZ in macrophage-mediated inflammation and fibrosis in the lung, we generated myeloid cell-specific Yap/Taz double knockout mice by crossing Yapflox/flox;Tazflox/flox mice with lysozyme-cre (LysMcre) mice that drive Cre recombinase activity in myeloid lineages, including macrophages. The resulting genotypes are referred to as control (Yapflox/flox;Tazflox/flox) and Yap/Taz double knockout (dKO; LysMcre;Yapflox/flox;Tazflox/flox) mice. To investigate the role of YAP/TAZ in bleomycin-induced inflammation, we treated both control and dKO mice with bleomycin for 7 and 14 days and compared them to saline-treated controls. Immunohistological analysis of bleomycin-injured lung sections revealed reduced expression of YAP and TAZ in CD68+ cells of LysMcre;Yapflox/flox;Tazflox/flox mice, indicating effective deletion of YAP/TAZ in macrophages (supplementary figure S2a and b, and figure 1i). We then harvested bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and perfused lungs for further analysis.

To determine if the deletion of Yap/Taz impacted the number of macrophages at baseline or following bleomycin-induced injury, we quantified CD68+ macrophages in the lungs of control and dKO mice. There was no change in the number of CD68+ macrophages in saline-treated control versus dKO lungs. However, under bleomycin-induced injury conditions, we observed a significant reduction in the number of CD68+ macrophages in the dKO lungs at both 7 and 14 days, compared to their respective controls (figure 2a and b). Next, we measured the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in BALF using ELISA. No differences were observed between saline-treated control and dKO lung samples. However, under bleomycin-induced injury conditions, we observed significantly reduced levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in the BALF of dKO mice compared to their respective controls (figure 2c). To further explore the role of YAP/TAZ in inflammatory responses, we examined the mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in lung tissue. Quantitative reverse-transcriptase (qRT)-PCR analysis revealed that several pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines-including Il6, Il1β, nitric oxide synthase-2 (Nos2), hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α (Hif1α), Ccl2, C-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (Ccr2), C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (Cx3cl1), C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1 (Cx3cr1), and Ccl17 were downregulated in the dKO lungs compared to controls at 14 days after bleomycin instillation (figure 2d). Additionally, the expression of pro-fibrotic macrophage genes such as Arginase 1 (Arg1), Resistin-like molecule α (Fizz1), and the YAP/TAZ target gene Ctgf was also reduced in the dKO lungs relative to controls. No differences were detected between control and dKO lungs for these genes under saline-treated conditions (figure 2d).

FIGURE 2.

Macrophage-specific Yap/Taz inactivation impairs bleomycin-induced inflammation in mouse lungs. a, b) Immunostaining and quantification of CD68-positive macrophage infiltration in control and double knockout (dKO) lungs treated with saline (day 0 (D0)) or bleomycin for 7 (D7) and 14 days (D14) (n=5). c) ELISA to measure the protein levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from control and dKO mice (n=5–6) treated with saline (D0) or bleomycin (D7 and D14). d) Real-time quantitative PCR to check the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines including Il6, Il1β, Nos2, Hif1α, Ccl2, Ccr2, Cx3cl1, Cx3cr1, Ccl17, as well as pro-fibrotic markers Arg1 and Fizz1, and the YAP/TAZ target gene Ctgf using lung tissue RNA from control and dKO mice (n=5–8) treated with saline (D0) or bleomycin (D14). Ccl: C-C motif chemokine ligand Nos: nitric oxide synthase; Hif: hypoxia-inducible factor; Ccr: C-C motif chemokine receptor; Cx3cl: C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand; Cx3cr: C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor; Arg: arginase; Fizz: resistin-like molecule-α; Ctgf: connective tissue growth factor; ns: nonsignificant. Data are presented as mean±sem, with statistical comparisons made using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. Significance levels are indicated with p-values (significant at p<0.05).

Growing evidence highlights that macrophages are key regulators of bleomycin-induced lung inflammation. Consequently, we hypothesised that YAP/TAZ might modulate the pro-inflammatory behaviour of lung macrophages. In the lung, two major macrophage populations have been identified: AMs and IMs. Both AMs and IMs increase following lung injury, and circulating monocytes are believed to be a primary source of these newly infiltrating macrophages, which contribute to the AM and IM phenotypes. Both of these macrophage populations play a critical role in both inflammation and inflammation-mediated fibrogenesis [7–10]. Therefore, we investigated whether Yap/Taz deficiency affects the recruitment and function of Mo-AMs following bleomycin administration in mice. Flow cytometry analyses of enzymatically digested lung tissue revealed a marked increase in Mo-AMs, identified as CD45+Ly6G−CD64+CD11blowSiglec-Flow in control lungs following bleomycin-induced injury at both day 7 and day 14. In contrast, the number of Mo-AMs was significantly reduced in dKO lungs compared to controls (figure 3a and b). Interestingly, the number of TR-AMs, identified as CD45+Ly6G−CD64+CD11blowSiglec-Fhigh, was decreased at day 7 in both control and dKO groups due to bleomycin treatment. However, at day 14, this population remained unaffected by bleomycin-induced injury and showed no significant differences between control and dKO mice (figure 3c). The number of IMs, identified as CD45+Ly6G−CD64+CD11bhighSiglec-F−, exhibited a time-dependent response following bleomycin injury. At day 7, the IM population was significantly reduced in both control and dKO lungs, with no differences observed due to the loss of Yap/Taz. By day 14, while there was a modest increase in the IM population in control lungs, this population remained significantly lower in the dKO lungs compared to controls (figure 3d). Overall, the inactivation of Yap/Taz specifically in myeloid cells leads to a reduction in both Mo-AMs and IMs populations in bleomycin-treated mice. The recruitment of another immune cell population, neutrophils (identified as CD45+Ly6G+), increased significantly following bleomycin-induced injury, peaking around day 7 in both control and dKO lungs. By day 14 post-injury, neutrophil levels declined, but remained elevated compared to saline controls. However, no significant differences in neutrophil populations were observed between control and dKO lungs at either time point (figure 3e). Since Yap/Taz deficiency did not impact the numbers of TR-AMs following bleomycin injury, we next characterised the gene expression patterns of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cytokines and chemokines in FACS-sorted Mo-AMs and IMs (figure 3f and g). The expression profiling revealed a marked upregulation of Il6 (∼10-fold), Il1β (∼15-fold), Ccl2 (∼18-fold), and Cx3cr1 (∼14-fold) in Mo-AMs following bleomycin treatment in control lungs compared to saline-treated lungs. However, Yap/Taz deficiency prevented the elevation of these pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic factors after bleomycin-induced injury. No differences were observed in the number of Mo-AMs between saline-treated control and dKO mice (figure 3b). In IMs, the mRNA levels of Il6 (∼1.5-fold), Il1β (∼1.4-fold), Ccl2 (∼1.6-fold) and Cx3cr1 (∼2.5-fold) were significantly elevated in the control lungs following bleomycin injury. However, the fold-induction of these cytokines/chemokines was lower compared to Mo-AMs. In IMs from dKO lungs, expression of Il6, Il1β and Cx3cr1 was reduced, while Ccl2 expression remained unaffected. In the saline-treated group, Yap/Taz-deficient IMs showed no significant differences in the expression of Il6, Il1β, Ccl2 and Cx3cr1 compared to controls (figure 3g). These findings suggest that YAP/TAZ plays a novel role in regulating the heterogeneity of lung macrophages during injury.

FIGURE 3.

Macrophage-specific Yap/Taz inactivation leads to decrease in monocyte-derived alveolar macrophage (Mo-AM) and interstitial macrophage (IM) population after bleomycin-induced injury. a–e) Gating strategy and flow cytometry analysis to sort Mo-AMs (identified as CD45+Ly6G−CD64+CD11blowSiglec-Flow), tissue-resident alveolar macrophages (TR-AMs) (identified as CD45+Ly6G−CD64+CD11blowSiglec-Fhigh), IMs (CD45+Ly6G−CD64+CD11bhighSiglec-F−) and neutrophils (identified as CD45+Ly6G+) using lung from control and double knockout (dKO) mice (n=5–9) treated with saline or bleomycin for 7 (D7) and 14 days (D14). f, g) Real-time quantitative PCR for pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as Il6, Il1β, Ccl2 and Cx3cr1 on sorted Mo-AMs or IMs from control and dKO mice (n=5) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. h, i) Immunoblot analysis of YAP, TAZ, cleaved caspase-1, cleaved interleukin (IL)-1β, nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain-like receptor containing pyrin domain (NLRP)3, pro-caspase-1, pro-IL-1β and ASC using cell lysates or supernatants as indicated from cultured lung macrophages isolated through flow cytometry (identified as Dapi−CD45+Ly6G−CD64+CD11b+ cells) on bleomycin-treated control and dKO mice (n=5–6). Quantification of indicated proteins relative to β-actin. SSC: side scatter; FSC: forward scatter; A: area; W: width; H: height; Dapi: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Ccl: C-C motif chemokine ligand; Cx3cr: C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor; ns: nonsignificant. Data are presented as mean±sem, with statistical comparisons made using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. Significance levels are indicated with p-value (significant at p<0.05).

To further investigate macrophage-mediated lung inflammation, we evaluated the role of YAP/TAZ in inflammasome activation by specifically analysing the activation of the NLRP3 (nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain-like receptor containing pyrin domain 3). NLRP3 activation in AMs significantly contributes to lung inflammation and injury by releasing the inflammatory mediator IL-1β via caspase-1 [25]. We cultured sorted lung macrophages, identified as Dapi−CD45+Ly6G−CD64+CD11b+ cells, from control and dKO mice that had been treated with bleomycin for 14 days. We then assessed the expression of inflammasome components NLRP3, caspase-1, IL-1β and ASC. Immunoblot analysis revealed that the absence of YAP/TAZ in lung macrophages resulted in a marked reduction in the release of cleaved caspase-1 and cleaved IL-1β in the culture supernatant. Additionally, in cell lysates, the protein levels of NLRP3, pro-caspase-1, cleaved caspase-1, pro-IL-1β, cleaved IL-1β and ASC were significantly diminished due to the deletion of Yap/Taz (figure 3h and i). Since NLRP3 is critical for the caspase-1-dependent maturation of IL-1β during inflammasome activation [26], these results suggest that YAP/TAZ are essential for the full activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in lung macrophages during inflammation.

Inactivation of Yap/Taz attenuates bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis

To understand the YAP/TAZ-dependent functions of macrophages in lung fibrosis, we conducted a comprehensive analysis involving histochemical, immunohistological, immunoblot, and qRT-PCR techniques on lung sections from both bleomycin-treated control and dKO mice. The analysis was performed at 7 and 14 days post-bleomycin administration to assess the progression of lung fibrosis (supplementary figure S3a and b) [27]. The deletion of Yap/Taz in macrophages significantly attenuated fibrosis in the dKO mice compared to their littermate controls, as demonstrated by reduced Sirius red staining and lower Ashcroft scores at both day 7 and day 14 post-injury (figure 4a and b). To further quantify the extent of fibrosis, we measured collagen content in lung tissue using a hydroxyproline assay. Bleomycin treatment significantly increased hydroxyproline levels in control lungs, indicating enhanced collagen deposition. However, at 14 days post-injury, the hydroxyproline content was notably decreased in the dKO lungs compared to the control group (figure 4c). Consistent with these findings, we examined the expression of key fibrogenic markers, including Collagen type I (collagen I) and the myofibroblast marker α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), in lung tissue. We observed a pronounced increase in collagen I and α-SMA expression in control lungs following bleomycin administration compared to saline treatment. In contrast, levels of collagen I and α-SMA were significantly reduced in dKO lungs, as determined by both immunofluorescence and immunoblot analysis at day 14 post-injury. No significant differences were observed between saline-treated control and dKO lungs (supplementary figure S4a–c). Gene expression analyses revealed that pro-fibrotic ECM-related genes, including collagen type I (Col1a1), collagen type III (Col3a1) and fibronectin 1 (Fn1), as well as myofibroblast-related genes such as smooth muscle actin-α2 (Acta2), were significantly downregulated in dKO lungs compared to controls at 14 days after bleomycin instillation (figure 4d). While bleomycin treatment markedly increased the expression of these genes compared to saline treatment, no significant differences were observed between saline-treated control and dKO lungs (figure 4d). These results strongly suggest that YAP/TAZ are enriched in lung macrophages during bleomycin-induced fibrosis and play a crucial role in regulating macrophage heterogeneity and functions that promote lung fibrosis.

FIGURE 4.

Macrophage-specific Yap/Taz inactivation reduces lung fibrosis after bleomycin-induced injury. a, b) Sirius Red/Fast Green staining and quantification (presented as Ashcroft score) on lung sections from control and double knockout (dKO) mice (n=6–7) treated with saline or bleomycin for 7 (D7) and 14 days (D14), respectively. c) Quantification of hydroxyproline content using lung tissue from control and dKO mice (n=5–7) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. d) Real-time quantitative PCR for pro-fibrotic genes Acta2, Col1a1, Col3a1 and Fn1 on lung tissue from control and dKO mice (n=5–8) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. e, f) Immunostaining and quantification of pro-surfactant protein C (SPC)+alveolar epithelial type-2 (AT2)-cells in control versus dKO mouse lung (n=5) treated with saline or bleomycin for 7 and 14 days. g) Flow cytometry analysis to determine the changes in the number of AT2-cells identified as CD45−CD31−CD326+MHCII+ in dKO lungs compared to controls (n=5) after saline or bleomycin treatment for 7 and 14 days. h, i) Immunostaining and quantification of Hopx+ AT1-cells in dKO lungs compared to controls (n=5) after saline or bleomycin treatment for 7 and 14 days. Dapi: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; MHC: major histocompatibility complex; Acta: smooth muscle actin-α; Col: collagen; Fn: fibronectin; ns: nonsignificant. Data are presented as mean±sem, with statistical comparisons made using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. Significance levels are indicated with p-value (significant at p<0.05).

Inactivation of Yap/Taz protects against bleomycin-induced alveolar epithelial cell damage

In the lung alveoli, alveolar epithelial type-2 cells (AT2 cells) are essential for maintaining alveolar integrity and function. They act as resident stem cells capable of proliferating and differentiating into alveolar epithelial type-1 cells (AT1 cells), which are crucial for efficient gas exchange and for the regeneration of new alveoli after injury [28, 29]. Dysfunction or damage to AT2 cells can significantly contribute to the progression of pulmonary fibrosis, as their impaired ability to regenerate and repair can exacerbate the fibrotic process [30, 31]. To evaluate the regenerative potential of alveolar epithelial cells in response to Yap/Taz inactivation in macrophages during bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, we compared dKO mice with their littermate controls. Both groups were subjected to bleomycin injury for 7 and 14 days. Post-injury, lung tissues were analysed using immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry and qRT-PCR. Our analysis revealed significant epithelial cell damage in the bleomycin-treated lungs, with notable loss of AT1 and AT2 cells at both 7 and 14 days compared to saline-treated controls (figure 4e–i). Despite this damage, the bleomycin treatment consistently increased the population of damage-associated transient progenitors (DATPs), which are AT2-derived cells capable of differentiating into AT1 cells. This was indicated by elevated expression of Keratin-8 (Krt8), a marker for these progenitors, in the lungs of bleomycin-treated mice at both time points. Interestingly, although Krt8 expression was increased due to bleomycin injury, there was no significant difference in Krt8 levels between dKO and control mice. This suggests that the inactivation of Yap/Taz in macrophages does not significantly affect the transition of AT2-derived DATPs or their differentiation into AT1 cells, as indicated by the unchanged Krt8 expression in the absence of Yap/Taz (supplementary figure S5).

Immunofluorescence analysis revealed a marked reduction in surfactant protein C (SPC)-expressing AT2 cells, as identified by pro-SPC antibody staining, at both day 7 and day 14 post-injury in both control and dKO lungs. There were no significant differences in AT2 cell loss between the control and dKO groups at day 7. However, by day 14, the dKO lungs exhibited a higher number of pro-SPC+ AT2 cells compared to the control lungs (figure 4e and f). Consistent with these findings, flow cytometry analysis also revealed a significant reduction in the number of AT2 cells, identified as CD45−CD31−CD326+MHCII+ cells, in both control and dKO lungs following bleomycin injury at days 7 and 14. However, at day 14 post-injury, the dKO lungs showed a notable increase in the CD45−CD31−CD326+MHCII+ cell population compared to the control lungs (figure 4g and supplementary figure S6a). This rise in AT2 cells in the dKO lungs correlated with elevated mRNA levels of Sftpc, a specific marker for AT2 cells, at day 14 post-injury (supplementary figure S6b). We next quantified the damage to AT1 cells and observed a reduction in AT1 cell numbers following bleomycin injury compared to saline treatment. This was detected through immunofluorescence staining of Hopx-positive cells, which serve as a marker for AT1 cells. We observed an increase in Hopx+ nuclei in dKO lungs compared to control lungs at 14 days post-injury. However, there was no significant difference between control and dKO lungs at 7 days after injury (figure 4h and i).

To determine if YAP is also activated in the AT2 cell population, we performed immunostaining for nuclear YAP and pro-SPC and quantified YAP+pro-SPC+ AT2 cells. At day 14 post-bleomycin injury, we observed an increase in the number of YAP+pro-SPC+ AT2 cells in both control and dKO lungs. Our findings are in line with a recent study that reported an increase in YAP+pro-SPC+ AT2 cells, particularly notable at 7 and 14 days after bleomycin-induced injury [32]. However, there was a notable reduction in YAP+pro-SPC+ AT2 cells in the dKO lungs compared to the control lungs after bleomycin injury (supplementary figure S7). This reduction may be attributable to the activity of LysMCre in a subset of alveolar epithelial cells [33, 34]. Despite this, the total population of pro-SPC+ AT2 cells was higher in the dKO lungs at day 14 post-injury (figure 4e and f). Collectively, these findings suggest that mice with Yap/Taz deletion in macrophages exhibit an enhanced epithelial regenerative response in the lung following bleomycin-induced injury.

Macrophage-specific YAP activation augments bleomycin-induced inflammatory response and fibrosis in the lung

To further investigate the role of YAP in inflammation-induced fibrosis, we activated YAP in myeloid cells using a conditional Rosa26 allele, R26YAP5SA, crossed with LysMCre mice. This genetic approach (LysMCre;R26YAP5SA) allowed us to express a constitutively active form of YAP in macrophages. We observed a strong nuclear localisation of YAP in CD68+ macrophages within the lungs of LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice, indicating effective YAP activation in these cells (supplementary figure S8). To assess the impact of YAP on macrophage-mediated inflammation and fibrosis, we treated the mice with either saline or bleomycin for 14 days and subsequently harvested their lungs for analysis using qRT-PCR, flow cytometry, immunoblotting and immunostaining. We examined whether macrophage presence was influenced by YAP overexpression following bleomycin-induced injury. In the saline-treated R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs, there were no significant changes in the number of CD68+ macrophages. As anticipated, bleomycin-induced injury increased the number of CD68+ macrophages in the R26YAP5SA lungs 14 days post-injury. Notably, the number of CD68+ macrophages rose even further in the LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs, indicating that YAP enhances macrophage infiltration following injury (figure 5a and b). Next, we assessed the expression of pro-inflammatory markers. qRT-PCR analysis indicated that YAP overexpression influenced the levels of various pro-inflammatory macrophage cytokines, including Il6 and Il1β; chemokines such as Ccl2, Ccr1, Cx3cl1 and Cx3cr1; the pro-fibrotic macrophage gene Arg1; the hypoxia regulator Hif1α; and the Hippo pathway target gene Ctgf in the lung (figure 5c and d). In saline-treated mice, LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs exhibited elevated levels of Il6, Arg1, Ccl2, Ccr2, Cx3cr1 and Ctgf compared to R26YAP5SA lungs. However, there were no significant differences in Il1β, Cx3cl1 or Hif1α levels. Following bleomycin administration, the gene expression of Il6, Il1β, Arg1, Ccl2, Ccr2, Cx3cr1 and Ctgf increased in R26YAP5SA lungs, with further enhancement observed in LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs. In contrast, while Hif1α and Cx3cl1 expression also rose after bleomycin-induced injury in R26YAP5SA mice, their levels were not significantly affected by YAP overexpression at the tissue level (figure 5c and d).

FIGURE 5.

Macrophage-specific Yap overexpression augments bleomycin-induced inflammatory response in mice lung. a, b) Immunostaining and quantification of CD68+ macrophage infiltration on the lung from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice (n=5) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. c, d) Real-time quantitative (q)PCR for pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as Il6, Il1β, Hif1α, Arg1, Ccl2, Ccr2, Cx3cl1 and Cx3cr1; with hippo target gene connective tissue growth factor (Ctgf) using lung tissue RNA isolated from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice (n=5) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. e–g) Flow cytometry analysis to sort the alveolar macrophages (Mo-AMs) (identified as CD45+Ly6G−CD64+CD11blowSiglec-Flow), tissue-resident alveolar macrophages (TR-AMs) (identified as CD45+Ly6G−CD64+CD11blowSiglec-Fhigh) and interstitial macrophages (IMs) (CD45+Ly6G−CD64+CD11bhighSiglec-F−) using lung from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice (n=5–6) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. h, i) Real-time qPCR for pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as Il6, Il1β, Cx3cr1 and Ccl2 on sorted Mo-AMs or IMs from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice (n=5) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. Il: interleukin; Hif: hypoxia-inducible factor; Arg: arginase; Ccl: C-C motif chemokine ligand; Ccr: C-C motif chemokine receptor; Cx3cr: C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor; Ctgf: connective tissue growth factor; ns: nonsignificant. Data are presented as mean±sem, with statistical comparisons made using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. Significance levels are indicated with p-value (significant at p<0.05).

To investigate whether YAP overexpression is linked to macrophage infiltration, we sorted lung macrophages using a method similar to that employed for the dKO model (figure 3a). Flow cytometry analysis revealed a significant increase in the Mo-AM population in LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs compared to R26YAP5SA lungs. However, the numbers of TR-AMs and IMs remained unchanged between the two groups (figures 5e–g). To identify the molecular changes associated with YAP activation, we assessed the mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cytokines and chemokines in sorted Mo-AMs and IMs. We observed that in Mo-AMs from LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs, Il6, Il1β, Ccl2 and Cx3cr1 expression was significantly increased compared to R26YAP5SA lungs following bleomycin injury, although no changes were observed in the saline-treated group (figure 5h). In IMs, bleomycin also induced higher expression levels of Il6, Il1β, Ccl2 and Cx3cr1 in R26YAP5SA lungs. However, no significant differences in the expression of these genes were observed between R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs. In the saline-treated group, only Ccl2 expression was increased in LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs compared to R26YAP5SA lungs, with no changes in Il6, Il1β or Cx3cr1 (figure 5i).

Next, we investigated the impact of macrophage-specific YAP activation on lung fibrosis both at baseline and following injury. Sirius red staining revealed increased fibrosis, as indicated by higher Ashcroft scores, in LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs compared to R26YAP5SA lungs, both at baseline and 14 days after bleomycin injury (figure 6a–c). This observation was supported by hydroxyproline assays, which showed elevated collagen content in LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs under both baseline and post-injury conditions (figure 6d). We also examined the expression of pro-fibrotic genes in lung tissue to assess the effects of YAP overexpression. YAP overexpression led to increased levels of the myofibroblast marker Acta2 and ECM genes Col1a1 and Col3a1 in bleomycin-treated LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs compared to R26YAP5SA lungs. Additionally, Col1a1 and Col3a1 were upregulated in saline-treated LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs compared to controls, although Acta2 expression did not change in these saline-treated groups (figure 6e). Immunoblot analysis confirmed these findings, showing that bleomycin treatment increased the protein levels of collagen I and α-SMA in LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs compared to R26YAP5SA lungs, indicating that YAP mediates the upregulation of these proteins following injury. In the saline-treated group, elevated collagen I levels were observed in LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs compared to R26YAP5SA lungs, although no significant difference in α-SMA expression was noted between these groups (figure 6f–h). Overall, these results suggest that YAP overexpression in lung macrophages during bleomycin-induced injury may influence macrophage recruitment, heterogeneity and functions related to lung fibrosis.

FIGURE 6.

Macrophage-specific Yap overexpression augments bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in mice. a–c) Sirius Red/Fast Green staining and quantification (presented as Ashcroft score) on lung sections from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice (n=5–7) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. d) Quantification of hydroxyproline content using lung tissue from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice (n=5–7) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. e) Real-time quantitative (q)PCR for pro-fibrotic genes Acta2, Col1a1, and Col3a1 on lung tissue from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice (n=5) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. f–h) Immunoblot analysis and quantification of collagen I and α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) protein using lung tissue from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mouse (n=5) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. i, j) Immunostaining and quantification of pro-surfactant protein C (SPC)+ alveolar epithelial type-2 (AT2) cells in R26YAP5SA versus LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice lung (n=5) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. k) Flow cytometry analysis to determine the changes in the number of AT2-cells identified as CD45−CD31−CD326+MHCII+ in LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs compared to R26YAP5SA lungs (n=5) after saline or bleomycin treatment for 14 days. l, m) Immunostaining and quantification of Hopx+ AT1-cells in LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs compared to R26YAP5SA lungs (n=5) after saline or bleomycin treatment for 14 days. Acta: smooth muscle actin-α; Col: collagen; Dapi: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; MHC: major histocompatibility complex; ns: nonsignificant. Data are presented as mean±sem, with statistical comparisons made using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. Significance levels are indicated with p-values (significant at p<0.05).

YAP overexpression augments bleomycin-induced alveolar epithelial cell damage

To determine whether YAP overexpression affects alveolar epithelial regeneration in vivo, we exposed R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice to either saline or bleomycin for 14 days. We then analysed lung tissues using immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry and qRT-PCR. In the saline-treated group, qRT-PCR analysis revealed a significant downregulation of the AT2 cell marker Sftpc in LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs compared to controls. Bleomycin treatment further reduced Sftpc expression in both groups, but in LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs, Sftpc levels dropped to baseline levels (supplementary figure S6c). Immunofluorescence analysis of AT2 cells showed that bleomycin treatment caused substantial damage to epithelial cells, evidenced by a decrease in pro-SPC-expressing AT2 cells. YAP overexpression led to a pronounced loss of AT2 cells in both saline and bleomycin-treated groups (figures 6i and j). Flow cytometry supported these findings, showing a significant reduction in AT2 cells, identified as CD45−CD31−CD326+MHCII+ population, in LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs compared to R26YAP5SA lungs (figure 6k). In contrast, AT1 cells, marked by Hopx, were similarly affected by bleomycin-induced injury, with no significant difference between R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs (figure 6l and m). This indicates that YAP activation in macrophages results in a loss of AT2 cells, but does not significantly affect the AT1 cell population after injury. Overall, these findings highlight the critical role of macrophage-specific YAP activation in regulating epithelial regeneration following injury.

Blocking of CCL2 using CCL2-neutralising antibody suppresses YAP-mediated pulmonary fibrosis after bleomycin injury

Macrophage infiltration is critical to the development of IPF/pulmonary fibrosis. Following lung injury, macrophage migration to inflammatory sites is primarily regulated by the chemokine CCL2, also known as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 [35, 36]. Increased CCL2 expression has been observed in pre-clinical models [36, 37] as well as in patients with IPF and other inflammatory lung diseases [38–42]. Studies have shown that blocking CCL2 with neutralising antibodies or genetically deleting its receptor, CCR2, reduces pulmonary fibrosis, highlighting CCL2's significant role in lung fibrogenesis [35, 36, 43]. In the current study, we investigated whether macrophage-specific deletion of Yap/Taz or overexpression of Yap affects CCL2 expression and function. qRT-PCR analysis showed that Yap/Taz deficiency led to reduced Ccl2 mRNA expression in bleomycin-injured lungs (figure 2d). Similarly, Ccl2 expression was diminished in Mo-AMs, but not in IMs (figure 3e and f). Conversely, Yap overexpression increased Ccl2 gene expression in both the lungs (figure 5d) and sorted Mo-AMs after bleomycin injury (figure 5h). Immunoblot analysis revealed decreased CCL2 protein levels in dKO lungs compared to controls after bleomycin treatment (figure 7a). However, CCL2 expression was higher in LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs compared to R26YAP5SA lungs, both in saline and bleomycin-treated animals at 14 days (figure 7b). These results suggest that YAP/TAZ may regulate lung fibrosis through CCL2 activation. Further analysis identified multiple predicted TEAD binding motifs in the ∼5 kb genomic region upstream of the Ccl2 promoter (supplementary figure S9a–c). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays using bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) treated with LPS confirmed that YAP and TAZ were enriched at Ccl2 promoter regions, specifically at sites 1 and 2, as verified by PCR amplification and sequencing (figure 7c).

FIGURE 7.

YAP/TAZ modulates C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL)2 expression and neutralising of CCL2 attenuates YAP-induced pulmonary fibrosis after bleomycin-injury. a) Immunoblot analysis and quantification of CCL2 protein using lung tissue from control and double knockout (dKO) mice (n=5–6) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. b) Immunoblot analysis and quantification of CCL2 protein using lung tissue from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice (n=5) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. c) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay performed on Ccl2 promoter using chromatin from wild-type bone marrow derived macrophages exposed to lipopolysaccharide (100 ng·mL−1) using IgG and YAP or TAZ antibody. d) Graphical presentation of experimental design; R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice were challenged to intratracheal administration of bleomycin (as 2.5 mg·kg−1 bodyweight (BW)) followed by intraperitoneal injection of CCL2 neutralising antibody or IgG (as 2 mg·kg−1 BW) as indicated time points. e) Immunostaining and quantification of CD68-positive macrophage infiltration in R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mouse lung (n=5) treated with bleomycin followed by IgG or CCL2 neutralising antibody treatment for 14 days. f) Quantification of flow cytometry analysis to sort alveolar macrophages (Mo-AMs), tissue-resident alveolar macrophages (TR-AMs) and interstitial macrophages (IMs) using lung from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice (n=7–9) treated with bleomycin followed IgG or CCL2 neutralising antibody treatment for 14 days. g, h) Sirius Red/Fast Green staining and quantification (presented as Ashcroft score) on lung sections from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice (n=5) treated with bleomycin following IgG or CCL2 neutralising antibody treatment for 14 days. i) Immunoblot analysis and quantification of collagen III protein in lung tissue from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice (n=5) treated with bleomycin followed by IgG or CCL2 neutralising antibody treatment for 14 days. j) mRNA analysis of Il6, Il1β, Acta2, Col1a1 and connective tissue growth factor (Ctgf) on lung tissue from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice (n=5) treated with bleomycin followed IgG or CCL2 neutralising antibody treatment for 14 days. k, l) Immunostaining and quantification of Hopx+ AT1-cells in R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs (n=5) treated with bleomycin following IgG or CCL2 neutralising antibody treatment for 14 days. m, n) Immunostaining and quantification of pro-surfactant protein C (SPC)+ alveolar epithelial type-2 (AT2) cells in R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice (n=5) treated with bleomycin followed with IgG or CCL2 neutralising antibody treatment for 14 days. o) Flow cytometry analysis to determine the changes in the number of AT2-cells identified as CD45−CD31−CD326+ major histocompatibility complex (MHC)II+ in R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs (n=7–9) treated with bleomycin followed IgG or CCL2 neutralising antibody treatment for 14 days. D: day; Dapi: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Il: interleukin; Acta: smooth muscle actin-α; Col: collagen; Ctgf: connective tissue growth factor; ns: nonsignificant. Data are presented as mean±sem, with statistical comparisons made using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. Significance levels are indicated with p-value (significant at p<0.05).

To evaluate the role of YAP-dependent CCL2 signalling in pulmonary fibrosis, we treated R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice with either IgG or CCL2-neutralising antibody following bleomycin administration for 14 days (figure 7d). CCL2 neutralisation reduced CD68+ macrophage infiltration in both R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA fibrotic lungs (figure 7e). Flow cytometry showed no significant changes in Mo-AM, TR-AM or IM populations in R26YAP5SA fibrotic lungs post-treatment, but a reduction in Mo-AMs was observed in LysMCre;R26YAP5SA fibrotic lungs, with TR-AMs and IMs remaining unaffected (figure 7f). Sirius red staining revealed lower Ashcroft scores in R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs treated with anti-CCL2 compared to IgG-treated controls (figure 7g and h). Additionally, immunoblot analysis showed reduced collagen III expression in response to anti-CCL2 treatment (figure 7i). Gene expression analysis indicated decreased levels of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic genes Il1β and Col1a1 in R26YAP5SA fibrotic lungs after anti-CCL2 treatment, with no changes in Il6, Acta2, or Ctgf. In LysMCre;R26YAP5SA fibrotic lungs, anti-CCL2 treatment led to downregulation of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic genes, including Il6, Il1β, Acta2, Col1a1 and Ctgf (figure 7j).

Furthermore, CCL2-neutralisation affected AT1 and AT2 cell populations. In bleomycin-treated R26YAP5SA lungs, the number of AT1 cells (Hopx+ nuclei) did not change significantly, while an increase in Hopx+ nuclei was observed in LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs with anti-CCL2 treatment (figure 7k and l). Anti-CCL2 treatment also improved the number of pro-SPC+ AT2 cells, as determined by immunofluorescence, and CD45−CD31−CD326+MHCII+ AT2 cells, as determined by flow cytometry, in both R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs (figure 7m–o). These findings suggest that YAP activation in macrophages enhances inflammation, fibrosis, and epithelial damage, likely through CCL2-mediated pro-inflammatory macrophage recruitment.

MBD2 is activated in lung macrophages of bleomycin-treated mice and acts as a downstream target of YAP during pro-fibrotic macrophage polarisation

Recent studies have revealed that methyl-CpG-binding domain 2 (MBD2) plays a role in driving the polarisation of resting macrophages into pro-fibrotic macrophages in the context of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis [44]. MBD2 is notably expressed in macrophages from both patients with IPF and in mice with bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis [44]. To investigate whether YAP/TAZ regulate MBD2 expression and function in macrophages during pulmonary fibrosis, we examined lung tissue samples from pulmonary fibrosis patients and from bleomycin-treated mice, alongside their respective controls. As anticipated, MBD2 was prominently expressed in macrophages in the lungs of pulmonary fibrosis patients, as evidenced by the increased number of CD68+MBD2+ cells compared to control human lung samples (figure 8a). Similarly, in the mouse pulmonary fibrosis model, bleomycin treatment led to a significant increase in CD68+MBD2+ cells compared to saline treatment (figure 8b). Co-immunostaining for MBD2, YAP and TAZ revealed that MBD2 predominantly colocalised with YAP/TAZ in CD68+ macrophages during pulmonary fibrosis in both humans and mice (supplementary figure S10a and b). We then explored the impact of macrophage-specific deletion of Yap/Taz or Yap overexpression on MBD2 expression in bleomycin-treated mouse lungs. Remarkably, genetic deletion of Yap/Taz resulted in a decrease in MBD2 protein levels, whereas overexpression of Yap led to an increase in MBD2 levels following bleomycin injury, compared to saline-treated controls (figure 8c–f). Immunostaining supported these findings, showing that Yap/Taz deletion significantly reduced the number of CD68+MBD2+ macrophages, whereas Yap overexpression increased their number in bleomycin-challenged lungs (supplementary figure S10c and d). Additionally, the protein expression of the pro-fibrotic macrophage marker ARG1 was diminished in Yap/Taz-deleted dKO lungs, whereas it was enhanced in Yap-overexpressing LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lungs (figure 8c–f). These results suggest a potential link between YAP/TAZ and MBD2 in regulating macrophage polarisation during bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. We next analysed ∼3 kb of genomic sequence upstream of the Mbd2 promoter and identified multiple predicted TEAD-binding sites (supplementary figure S9a, b and d). To determine if YAP and TAZ bind directly to the Mbd2 promoter, we performed a ChIP assay using LPS-treated BMDMs. The results revealed that YAP and TAZ-immunoprecipitated samples were enriched for Mbd2 promoter DNA (figure 8g). Sequencing of the PCR-amplified fragments confirmed this interaction, indicating that YAP/TAZ may regulate MBD2-mediated macrophage functions. Further analysis using qRT-PCR on sorted Mo-AMs revealed that Mbd2 expression, along with the pro-fibrotic macrophage genes Arg1 and Tgfβ1, was downregulated in dKO lungs following bleomycin treatment (figure 8h).

FIGURE 8.

Loss of Yap/Taz attenuates methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD)2 expression in mouse fibrotic lung and MBD2 acts downstream of YAP during pro-fibrotic macrophage polarisation. a) MBD2 is highly expressed in CD68+ lung macrophages of a patient with pulmonary fibrosis (PF) compared to normal adult human (healthy adult) subject (n=3). b) MBD2 is highly expressed in CD68+ lung macrophages after bleomycin treatment compared to saline treatment in wild-type mice (n=5). c, d) Immunoblot analysis and quantification of MBD2 and arginase (ARG)1 protein using lung tissue from control and double knockout (dKO) mice (n=5) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. e, f) Immunoblot analysis and quantification of MBD2 and ARG1 protein using lung tissue from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice (n=5) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. g) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay performed on Mbd2 promoter using chromatin from wild-type bone marrow-derived macrophages exposed to lipopolysaccharide LPS (100 ng·mL−1) using IgG and YAP or TAZ antibody. h) Real-time quantitative (q)PCR for Mbd2, Arg1 and Tgfβ1 on sorted alveolar macrophages (Mo-AMs) from control and dKO mice (n=5) treated with saline or bleomycin for 14 days. i, j) Immunoblot analysis and quantification of MBD2, ARG1, pAKT (S473), AKT, mature-transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 and YAP using total lung macrophages (CD45+Ly6GCD64+CD11b+) isolated using flow cytometry and subsequently cultured derived from LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mouse lung (n=5) treated with bleomycin or saline to perform the knockdown experiment with Mbd2 siRNA or control (Ctr) siRNA. k, l) R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice were challenged to intratracheal administration of bleomycin (as 2.5 mg·kg−1 bodyweight) and the total lung macrophages were harvested and cultured to collect the conditioned medium (CM). k) Immunofluorescence staining and quantification of α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) and collagen I using wild-type mouse lung (n=5) fibroblasts treated with either DMEM or CM collected from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lung macrophages challenged to bleomycin-injury. l) Immunofluorescence staining and quantification of α-SMA and collagen I using wild-type mouse lung (n=5) fibroblasts treated with IgG or TGFβ1-neutralising antibody (neu ab; 1 μg·mL−1) under the exposure of CM collected from LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lung macrophages challenged to bleomycin-injury. m) Immunofluorescence staining and quantification of α-SMA and collagen I using LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lung (n=5) fibroblasts treated with CM collected from LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lung macrophages challenged to bleomycin-injury followed by Mbd2 siRNA or control siRNA exposure. n) Immunoblot analysis and quantification of pSMAD2 using LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lung fibroblasts treated with either DMEM or CM collected from LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lung macrophages challenged to bleomycin-injury followed by Mbd2 siRNA or control siRNA exposure. The data are represented as mean±sem; comparison by two-tailed unpaired t-test. Significance levels are indicated with p-values (significant at p<0.05). *: p<0.05; ***: p<0.001.

To further investigate the role of YAP-mediated MBD2 regulation in macrophages, we used LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice. After treating these mice with bleomycin or saline, we isolated total lung macrophages (CD45+Ly6G−CD64+CD11b+) using flow cytometry, cultured the cells, and performed knockdown experiments with Mbd2 siRNA or control siRNA (figure 8i–k). We also collected the conditioned medium from these cultured lung macrophages, transfected with control or Mbd2 siRNA. Bleomycin treatment increased the protein levels of ARG1, mature TGFβ1, pAKT (S473) and YAP in primary lung macrophages compared to saline treatment. Notably, Mbd2 knockdown significantly reduced bleomycin-induced expression of ARG1, pAKT (S473) and mature TGFβ1 in lung macrophages, while levels of YAP and total AKT remained unchanged (figure 8i and j). These findings suggest that MBD2 operates downstream of YAP to promote pro-fibrotic macrophage polarisation during bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis.

It is well established that macrophage secretome, rich in pro-fibrotic mediators, plays a crucial role in activating neighbouring fibroblasts in pulmonary fibrosis [45]. To assess whether YAP-dependent functions of MBD2 in macrophages impact pro-fibrotic processes in fibroblasts, we collected conditioned medium from lung macrophages harvested from R26YAP5SAand LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice treated with bleomycin. We then exposed wild-type lung fibroblasts to either normal DMEM as a control or conditioned medium from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lung macrophages and evaluated myofibroblast formation and collagen I production.

Compared to DMEM control, conditioned medium from R26YAP5SA macrophages significantly increased α-SMA and collagen I expression in fibroblasts, and this effect was further enhanced with conditioned medium from LysMCre;R26YAP5SA macrophages (figure 8k). These results suggest that the secretome from YAP-overexpressing macrophages promotes fibroblast activation and myofibroblast formation. To further investigate whether YAP activation in macrophages regulates fibroblast transition, we treated primary human lung fibroblasts with conditioned medium from R26YAP5SA or LysMCre;R26YAP5SA lung macrophages for 16 h. Fibroblasts treated with DMEM control exhibited mainly cytoplasmic YAP and fewer αSMA-positive cells. In contrast, fibroblasts exposed to conditioned medium from R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA macrophages showed ∼50% and ∼70% nuclear YAP and α-SMA double-positive cells, respectively (supplementary figure S11). These findings suggest that YAP in macrophages may promote fibroblast transition during lung injury.

Given the increased TGFβ1 expression in lung macrophages after bleomycin injury and the impairment of this expression upon Yap/Taz loss (figure 8h), we investigated whether neutralising TGFβ1 affects the LysMCre;R26YAP5SA macrophage-secretome-induced myofibroblast formation and collagen production. Treatment of wild-type lung fibroblasts with a TGFβ1-neutralising antibody abolished the LysMCre;R26YAP5SA secretome-induced myofibroblast formation and collagen I expression compared to IgG treatment (figure 8l). To determine if Mbd2 knockdown in LysMCre;R26YAP5SA macrophages impacts YAP-mediated pro-fibrotic effects in fibroblasts, we treated LysMCre;R26YAP5SA fibroblasts with conditioned medium from lung macrophages that had been treated with either control or Mbd2 siRNA. We observed that conditioned medium from Mbd2 siRNA-treated macrophages was less effective in promoting myofibroblast formation and collagen production compared to conditioned medium from control siRNA-treated macrophages. This reduced effectiveness is likely due to decreased TGFβ1 secretion from the Mbd2 siRNA-treated macrophages (figure 8m). To further investigate whether this effect results from impaired TGFβ1 signalling between macrophages and fibroblasts, we performed an immunoblot analysis for pSMAD2, a downstream effector of TGFβ1 signalling, using cell lysates from LysMCre;R26YAP5SA fibroblasts treated with either DMEM or conditioned medium from macrophages treated with control or Mbd2 siRNA. We observed a significant reduction in pSMAD2 levels in fibroblasts exposed to conditioned medium from Mbd2 siRNA-treated macrophages compared to those exposed to control siRNA-treated macrophages (figure 8n). These results suggest that YAP promotes pro-fibrotic functions through the MBD2-TGFβ1-pSMAD2 axis in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis (figure 9).

FIGURE 9.

Graphical model for the macrophage-mediated role of YAP/TAZ during pulmonary fibrosis. Schematic representation showing that development of fibrosis associated with the homing of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic macrophages through the CCL2–CCR2 axis after bleomycin treatment. Pulmonary fibrosis augments the activation of YAP and TAZ in alveolar macrophages (Mo-AMs) and interstitial macrophages (IMs), which induces the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, etc., as well as pro-fibrotic cytokine transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 through the MBD2-pAKT-pSMAD2-ARG1 axis that activate the transition of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts leading to pulmonary fibrosis as featured by the expressive production of collagen I, α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) and fibrotic score. Macrophage-specific genetic ablation of Yap/Taz reduces the homing of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic macrophages and defective myofibroblasts formation with impaired pulmonary fibrosis. CCL: C-C motif chemokine ligand; CCR: C-C motif chemokine receptor; MBD: methyl-CpG-binding domain; ARG: Arginase.

Discussion

Macrophages are pivotal cells of the innate immune system, essential for pathogen defence, development, homeostasis and tissue repair. In IPF and pre-clinical models of pulmonary fibrosis, macrophages are the predominant immune cells in the lungs, playing a critical role in immune responses and airway remodelling [46–49]. While the presence of multiple macrophage subsets in pulmonary fibrosis/IPF is well established, their specific contributions and regulatory mechanisms in the pathogenesis of lung fibrosis and remodelling remain poorly understood. Furthermore, the mechanisms through which macrophage-mediated pro-inflammatory responses impact fibrosis and their potential as therapeutic targets in pulmonary fibrosis/IPF are not well defined. Although YAP/TAZ are generally reported to have minimal roles in haematopoietic cells under normal conditions, consistent with their low expression levels in macrophages [50], we observed a significant increase in YAP/TAZ expression and nuclear localisation in macrophages from patients with pulmonary fibrosis and in mice after bleomycin-induced injury. This increased nuclear localisation of YAP/TAZ is associated with enhanced responsiveness to injury signals [17, 18, 22]. Together, our data highlight the role of YAP/TAZ in regulating the recruitment of specific macrophage populations, macrophage polarisation, pro-inflammatory responses, and the cross-talk between macrophages and lung fibroblasts, driving the fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition and contributing to tissue fibrosis.

The lungs are continually exposed to external environmental factors that influence their cellular environment, with macrophages playing a crucial role in maintaining respiratory homeostasis. Pulmonary tissue macrophages, including both AMs (Mo-AMs and TR-AMs) and IMs, are categorised according to their anatomical locations. Mo-AMs are derived post-natally from circulating monocytes, which are recruited to sites of injury, whereas TR-AMs originate from the embryonic yolk sac and are long-lived, self-renewing cells that maintain homeostasis. In contrast, IMs are generated from both yolk sac macrophages and bone marrow-derived monocytes. Pre-clinical studies have shown that following lung injury, circulating monocytes differentiate into specific macrophage subpopulations (Mo-AMs and IMs), known for their inflammatory and pro-fibrotic role in inducing pulmonary fibrosis [7–10, 48, 51–53]. In this study, we observed an increase in pro-fibrotic Mo-AMs during bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis, which correlated with elevated Yap/Taz expression in macrophages. Genetic deletion of Yap/Taz specifically in myeloid cells reduced the number of Mo-AMs and IMs, but did not affect TR-AMs, in the bleomycin-treated lungs. In addition to the reduced numbers of Mo-AMs and IMs, we observed a decrease in the gene expression of pro-inflammatory/pro-fibrotic cytokines and chemokines, including Il6, Il1β, Ccl2 and Cx3cr1, in isolated Mo-AMs and IMs. Notably, these changes were more pronounced in Mo-AMs than in IMs, indicating that Mo-AMs play a more significant role in the development of pulmonary fibrosis compared to IMs. Moreover, activation of Yap led to an increase in the number of Mo-AMs in the lung following bleomycin induction, without affecting TR-AMs or IMs. This increase in Mo-AMs was associated with elevated gene expression levels of Il6, Il1β, Ccl2 and Cx3cr1. Consistent with the low expression and minimal role of Yap/Taz under baseline conditions, we did not observe any significant changes in the numbers of Mo-AMs, IMs or TR-AMs in uninjured lungs. In line with our findings, previous studies have shown that depleting circulating monocytes, either through the use of Ccr2−/− mice or liposomal clodronate, significantly reduces the severity of pulmonary fibrosis [36]. Similarly, targeted depletion of Mo-AMs via necroptosis during their differentiation, using Casp8flox/flox mice, improved pulmonary fibrosis [7, 10]. Consistent with our observations in Yap/Taz knockout lungs, the depletion of TR-AMs did not impact the development of pulmonary fibrosis [7]. Unlike Mo-AMs, Yap/Taz deletion in IMs decreased the expression of Il6, Il1β and Cx3cr1, but did not affect Ccl2 expression. A recent study identified two distinct subpopulations of monocyte-derived IMs: Lyve1lowMHCIIhighCX3CR1high (Lyve1lowMHCIIhigh) and Lyve1highMHCIIlowCX3CR1low (Lyve1highMHCIIlow). Inducible depletion of the Lyve1highMHCIIlow IMs was found to exacerbate bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, highlighting the importance of functional diversity among IM subsets in pulmonary fibrosis pathogenesis [9]. Further research is needed to explore the differential roles of YAP/TAZ in regulating these IM subpopulations and their contributions to pulmonary fibrosis. Our previous work, along with that of others, has demonstrated that YAP/TAZ can either directly or indirectly influence inflammatory and fibrotic responses depending on the pathological context [18, 22]. Previous studies have shown that Yap regulates NLRP3 inflammasome function in macrophages across various biological contexts, including LPS-induced systemic inflammation and ischaemia-induced cardiac inflammation [54, 55]. To investigate whether YAP/TAZ plays a similar role in IPF, we analysed the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway in a bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis model. We observed reduced levels of caspase-1 and IL-1β in Yap/Taz-deficient macrophages, indicating impaired activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, which is crucial for the caspase-1-mediated maturation of IL-1β [26, 56]. Our findings suggest that Yap/Taz deletion significantly mitigates the severity of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by affecting both macrophage infiltration and the macrophage-dependent secretion of inflammatory and fibrotic factors.

The CCL2-CCR2 pathway is crucial for driving macrophage infiltration following lung injury [35, 36]. Elevated CCL2 expression is associated with fibrosis in both pre-clinical models and patients with inflammatory lung diseases, including IPF [36–42]. Conversely, disrupting this pathway (either by inhibiting CCL2 with neutralising antibodies or by genetically ablating its receptor CCR2), results in impaired macrophage recruitment, reduced expression of pro-fibrotic cytokines, and diminished myofibroblast formation, ultimately leading to improved lung fibrosis in mice [35, 36, 43]. These findings suggest that CCL2-CCR2 signalling plays an important role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis/IPF by regulating fibrotic cytokine expression and fibroblast activation. In this study we found that YAP/TAZ directly binds to the Ccl2 promoter and regulates its expression in macrophages. Macrophages-specific modulation of Yap/Taz expression (Yap/Taz deletion or Yap overexpression) affects Ccl2 expression, interestingly, only in isolated Mo-AMs but not in IMs from bleomycin-injured lungs. A single-cell analysis also found elevated levels of Ccl2 in both the intermediate alveolar epithelial cells and the activated fibroblasts of AT-2 cell-specific Yap/Taz knockouts lungs post-bleomycin treatment, promoting Mo-AMs recruitment and fibroblasts proliferation and activation [32]. Blocking the CCL2-CCR2 pathway in Yap-activated (LysMCre;R26YAP5SA) mice using a neutralising CCL2 antibody resulted in reduced infiltration of CD68+ macrophages and Mo-AMs, and impaired pro-inflammatory responses following bleomycin-induced injury, leading to improved pulmonary fibrosis. These findings suggest that the YAP/TAZ-CCL2 signalling axis regulates macrophage recruitment and the inflammatory/pro-fibrotic response, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis.

Pro-fibrotic macrophage-polarisation mediators present a promising target for preventing the progression of IPF. Studies have shown that YAP/TAZ interact with chromatin-remodelling complex proteins, which modify chromatin structure and, consequently, influence the accessibility and activity of target genes [18, 57–60]. We have shown that YAP/TAZ are associated with chromatin-remodelling complex proteins, which regulate macrophage polarisation [18]. In a candidate-based screen, we identified Mbd2 as a downstream target of YAP/TAZ that affects macrophage polarisation during pulmonary fibrosis. Recent studies have implicated MBD2 in organ fibrosis, including pulmonary fibrosis [44, 61, 62]. MBD2 is predominantly expressed by infiltrating macrophages in the lungs of IPF patients and in mice following bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. MBD2 promotes the polarisation of resting macrophages into pro-fibrotic macrophages, as indicated by the reduced expression of ARG1 in macrophage-specific Mbd2 knockout lungs following bleomycin treatment [44]. Macrophage-specific Yap/Taz deficiency led to reduced MBD2 expression, while Yap overexpression resulted in increased MBD2 expression in bleomycin-induced lungs. Consistently, ARG1 expression was significantly lower in Yap/Taz knockout lungs and higher in lungs with Yap overexpression. Furthermore, Mbd2 knockdown in sorted lung macrophages (CD45+Ly6G−CD64+CD11b+) from LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice abolished bleomycin-induced ARG1 expression, suggesting that YAP/TAZ modulate ARG1 expression in lung macrophages through an MBD2-dependent mechanism, probably involving the MBD2–pAKT–ARG1 signalling axis. The reduced expression of ARG1 in Yap/Taz knockout lung macrophages differs from our observations in cardiac macrophages after ischaemic injury, where ARG1 expression was upregulated in the absence of Yap/Taz. In cardiac macrophages, YAP/TAZ repress ARG1 expression by binding to its promoter and recruiting the histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3)-nuclear receptor corepressor 1 (NCoR1) repressor complex. In contrast, in lung macrophages, YAP/TAZ promote ARG1 expression through the regulation of MBD2 expression. Together, our results illustrate that YAP/TAZ modulate macrophage polarisation in a tissue-specific manner, acting as either transcriptional coactivators or corepressors depending on the biological context.

Macrophages are located near fibrogenic sites and play a crucial role in chronic inflammation and the progression of fibrosis. Studies have shown that aberrant activation, infiltration and polarisation of pro-fibrotic Mo-AMs, and their interaction with fibroblasts, are major factors driving the development of pulmonary fibrosis [7, 10, 43, 49, 53, 63]. Pro-fibrotic Mo-AMs are a primary source of TGFβ1, which promotes the differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, initiating pulmonary fibrosis. Macrophage-specific deletion of TGFβ1 attenuated lung fibrosis in the bleomycin-induced model [64]. Similar to YAP activation following bleomycin induction, we observed increased TGFβ1 expression in lung macrophages. However, this increase in TGFβ1 was abolished when MBD2 expression was reduced using siRNA knockdown. Furthermore, conditioned media from Mbd2 knockdown macrophages was less fibrotic compared to controls, evident by reduced α-SMA+ myofibroblast formation and collagen synthesis in lung fibroblasts. These results suggest that YAP regulates TGFβ1 expression in an MBD2-dependent manner in bleomycin-induced lung macrophages. Furthermore, the reduced levels of pSMAD2 in lung fibroblasts treated with conditioned medium from Mbd2 siRNA-treated macrophages suggest that the diminished fibrotic effect is attributable to impaired TGFβ1 signalling between macrophages and fibroblasts. Consistent with this, a recent study also reported that Mbd2 deletion in macrophages led to decreased TGFβ1 production and reduced bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice [44]. Consistent with these studies, our findings highlight the critical role of the YAP/TAZ–MBD2–TGFβ1–pSMAD2 signalling axis in macrophage–fibroblast cross-talk, which significantly contributes to the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis.

Macrophage-mediated inflammation and fibrosis can also impact the regenerative potential of the lung by affecting AT1/AT2 cells. AT2 cells play a critical role in the progression of pulmonary fibrosis/IPF [30, 31]. In the lung, AT2 cells serve as resident stem cells that can proliferate and differentiate into AT1 cells through DATPs, crucial for the regeneration of damaged lung tissue following injury [28, 29]. Consequently, genetic loss of Yap/Taz impaired the development of fibrosis by weakening the macrophage-mediated inflammatory response and enhancing the repair capacity of alveolar epithelial cells, as indicated by the increased number of AT1 and AT2 cells following bleomycin-induced injury. In contrast, Yap activation in macrophages exacerbated the inflammatory response, leading to worsened fibrosis and greater damage to alveolar epithelial cells, evidenced by a reduced number of AT1 and AT2 cells after bleomycin injury. Additionally, Yap/Taz deletion or Yap activation in macrophages resulted in decreased and increased IL-1β expression, respectively. Typically, injury-induced IL-1β signalling promotes the differentiation of AT2 cells into AT1 cells [65]. However, chronic inflammation driven by sustained IL-1β signalling impedes the terminal differentiation of AT2 cells into mature AT1 cells, resulting in an abnormal accumulation of DATPs and impaired alveolar regeneration [65]. Growing evidence indicates that increased myofibroblast activity can lead to the loss of alveolar niche fibroblasts by disrupting the local microenvironment, altering cellular interactions, and promoting fibrosis [66–70]. This disruption impairs the alveolar niche's ability to support proper alveolar differentiation and function, ultimately compromising lung health [66–68]. In contrast, reduced fibrosis observed in Yap/Taz dKO models may positively influence the alveolar niche, enhancing both alveolar differentiation and function. This is consistent with the observed increase in the number of AT1 and AT2 cells following bleomycin-induced injury. Additionally reduced TGFβ1 production observed in Yap/Taz dKO lungs can also directly affect AT1/AT2 cells. A recent study, using conditional deletion of TGFβRII in AT1 and AT2 cells demonstrated the cell intrinsic requirement of the TGFβ1 signalling in modulating AT1/AT2 cell proliferation and cell fate [71]. These findings suggest that the cross-talk between macrophages, myofibroblasts and alveolar epithelial cells is crucial in shaping a favourable local microenvironment, essential for AT1 and AT2 cell-mediated lung regeneration and repair following injury.

In summary, we have demonstrated that YAP/TAZ are key regulators of macrophage infiltration, polarisation, and their interactions with lung fibroblasts and alveolar epithelial cells in the bleomycin-induced lung injury model. The Hippo-YAP/TAZ signalling pathway also influences lung fibroblasts by promoting their proliferation and ECM synthesis, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of IPF. Lung macrophages and fibroblasts are two crucial cell types involved in the progression of IPF. Given the significant role of Hippo-YAP/TAZ signalling in both of these cell types, targeting this pathway pharmacologically may provide a promising approach for treating IPF.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material: Materials and methods.

ERJ-01544-2023.Supplement

Supplementary figure S1: Increased macrophage numbers in human fibrotic lungs. Immunofluorescence staining and quantification of CD68+ macrophages within collagen I+ areas were performed on lung sections from patients with pulmonary fibrosis and compared to normal adult human lungs (n=3). Data are presented as mean±SEM, with statistical comparisons made using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. Significance levels are indicated with p-value (p<0.05: significant; NS: not significant).

ERJ-01544-2023.Figure_S1

Supplementary figure S2: Bleomycin treatment activates YAP/TAZ expression in lung macrophages. a, b) Representative images of lung tissue sections following bleomycin-induced injury, stained for CD68 (green), YAP (red), TAZ (pink), and DAPI (blue). In control mice, macrophages exhibited increased nuclear localisation and activity of YAP and TAZ, 7 days post-bleomycin treatment. In dKO lungs, YAP and TAZ expression was inactivated in CD68+ macrophages. White arrows indicate CD68+ cells that also express YAP or TAZ in control lung sections. In dKO lungs, white arrows point to CD68+ cells that lack YAP and TAZ expression.

ERJ-01544-2023.Figure_S2

Supplementary figure S3: Bleomycin induces lung fibrosis model. a) In this study, various mouse models were used to examine bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. The models included Yapflox/flox;Tazflox/flox, LysMCre;Yapflox/flox;Tazflox/flox, R26YAP5SA and LysMCre;R26YAP5SA mice, which were treated with either saline or bleomycin for 7 or 14 days. Lung tissues were collected for sectioning and immunohistochemical analysis. b) Sirius red and Trichrome staining were employed to evaluate lung fibrosis. Representative sections from control mice (Yapflox/flox;Tazflox/flox) illustrate the development of bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis at both day 7 and day 14, in comparison to saline-treated controls.

ERJ-01544-2023.Figure_S3

Supplementary figure S4: Loss of Yap/Taz in macrophage attenuates myofibroblasts and collagen production induced by bleomycin. a, b) Immunofluorescence staining and quantification of α-SMA and collagen I in lung sections from control and dKO mice (n=5), treated with either saline or bleomycin for 14 days. Fluorescence intensity was measured using ImageJ software. c) Immunoblot analysis and quantification of α-SMA and collagen I protein levels in lung tissue from control and dKO mice (n=5), following saline or bleomycin treatment for 14 days. Data are presented as mean±SEM, with statistical comparisons made using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. Significance levels are indicated with p-value (p<0.05: significant; NS: not significant).

ERJ-01544-2023.Figure_S4

Supplementary figure S5: Macrophage-specific Yap/Taz inactivation shows no alteration in damage-associated transient progenitors (DAPTs) after bleomycin-induced injury. Immunostaining and quantification of Krt8+ DAPTs in lung sections from control and dKO mice (n=5), treated with saline or bleomycin for 7 days (D7) and 14 days (D14). The data are shown as mean±SEM, with statistical comparisons performed using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. Significance levels are indicated with p-value (p<0.05: significant; NS: not significant).

ERJ-01544-2023.Figure_S5