Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a common neurodegenerative disorder among the elderly, and BuChE has emerged as a potential therapeutic target. In this study, we reported the development of compound 8e, a selective reversible BuChE inhibitor (eqBuChE IC50 = 0.049 μmol/L, huBuChE IC50 = 0.066 μmol/L), identified through extensive virtual screening and lead optimization. Compound 8e demonstrated favorable blood–brain barrier permeability, good drug-likeness property and pronounced neuroprotective efficacy. Additionally, 8e exhibited significant therapeutic effects in zebrafish AD models and scopolamine-induced cognitive impairments in mice. Further, 8e significantly improved cognitive function in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Proteomics analysis demonstrated that 8e markedly elevated the expression levels of very low-density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR), offering valuable insights into its potential modulation of the Reelin-mediated signaling pathway. Thus, compound 8e emerges as a novel and potent BuChE inhibitor for the treatment of AD, with significant implications for further exploration into its mechanisms of action and therapeutic applications.

Key words: Alzheimer's disease, Selective BuChE inhibitor, Pharmacokinetic studies, Pharmacodynamic studies, Mechanism of action

Graphical abstract

Compound 8e is a selective, reversible BuChE inhibitor identified through virtual screening and SAR studies, showing favorable blood–brain barrier permeability and neuroprotective effects. It significantly improves cognitive function in various Alzheimer's disease models and offers insights into potential mechanisms involving the Reelin-mediated signaling pathway.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's Disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that primarily affects older adults, leading to declines in memory, cognition, and other essential brain functions1. Currently, over 55 million individuals worldwide are diagnosed with AD, a figure projected to rise to 139 million by 2050. The global economic impact of dementia is substantial, currently estimated at approximately $1.3 trillion2. The increasing prevalence of AD not only poses a significant burden on healthcare systems but also strains societal resources, as the aging population continues to grow3.

Despite considerable research efforts, the precise etiology of AD remains elusive. Observed pathological changes in the brains of AD patients include decreased levels of acetylcholine (ACh), the accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) deposits, heightened oxidative stress, hyperphosphorylated tau neurofibrillary tangles, biometal ion dysregulation, and inflammation4,5. Based on these pathological features, several classes of therapeutic agents have been developed and approved by the FDA: cholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., rivastigmine, donepezil, galantamine), NMDA receptor antagonists (e.g., memantine), and monoclonal antibodies (e.g., aducanumab, lecanemab)6. While these drugs demonstrate partial efficacy over prolonged clinical use, they cannot prevent, halt, or reverse the disease's progression. Furthermore, AD patients often experience significant adverse effects from these treatments, including gastrointestinal disturbances, dizziness, and more severe events such as heart failure, convulsions, or infusion-related reactions associated with monoclonal antibodies7, 8, 9. Thus, the urgent need for more effective and safer therapeutic agents has never been more pressing.

The etiology of AD is complex, involving multiple signaling pathways. The strategy of employing multi-target-directed ligands (MTDLs)—single chemical entities that can engage two or more AD-relevant targets—has gained traction10,11. However, identifying suitable targets and achieving a balanced and synergistic interaction among multiple targets in vivo presents a significant challenge for current MTDLs strategy. Therefore, the identification of specific targets that can simultaneously regulate multiple AD-related signaling pathways offers new hope for the development of effective treatments for AD.

ACh, the first neurotransmitter discovered, has been the focus of research for over a century due to its critical role in learning and memory. Abnormally reduced levels of ACh in the hippocampus and neocortex have been directly associated with cognitive decline in AD12. Most FDA-approved AD therapies aim to enhance ACh levels, highlighting the enduring relevance of the classical cholinergic hypothesis in AD pathogenesis. Two critical esterases, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE), play significant roles in this context. Typically, BuChE serves as a backup to AChE within the cholinergic system. However, in AD patients, AChE levels decrease to approximately 62%–67% of physiological levels, while BuChE levels increase to around 165%13,14. This compensatory rise in BuChE has been evidenced in AChE-knockout mouse models, suggesting its involvement in the hydrolysis of ACh in the context of AD15,16. Research utilizing various AD mouse models has demonstrated that either BuChE knockout (using BuChE−/− mice) or BuChE inhibition can yield neuroprotective effects13,17. Importantly, BuChE has been recognized as a safe therapeutic target; BuChE-knockout mice do not exhibit physiological defects, and individuals with silenced BuChE genes can maintain good health18,19. Therefore, selectively inhibiting BuChE presents a promising strategy to mitigate peripheral cholinergic side effects while effectively treating advanced AD. In addition to its cholinergic functions, histochemical studies have linked BuChE accumulation in senile plaques to the aggregation of Aβ. Notably, fibrillar Aβ deposits are significantly reduced in BuChE-knockout mice, while wild-type mice exhibit cognitive impairments when exposed to neurotoxic Aβ25–35, a response not observed in BuChE-knockout mice20,21. These findings suggest that BuChE inhibition may also effectively address abnormal Aβ aggregation, reinforcing the rationale for targeting BuChE in AD treatment. However, further research is needed to explore the potential mechanisms through which BuChE inhibitors may exert anti-AD effects via additional signaling pathways.

Herein, we conducted a virtual screening utilizing a pharmacophore model and identified a novel BuChE inhibitor (Fig. 1), hit compound V1 (eqBuChE IC50 = 0.66 μmol/L). Subsequent structural modifications and structure–activity relationship (SAR) analyses led to the optimization of 8e (eqBuChE IC50 = 0.049 μmol/L, huBuChE IC50 = 0.066 μmol/L). Docking simulations and dynamic studies provided a rational explanation for its enhanced activity. The remarkable potency of compound 8e prompted comprehensive investigations into its selectivity, reversible inhibition, neuroprotective effects, drug-likeness, pharmacokinetics, and safety profiles. In vivo studies employing AD zebrafish models, scopolamine-induced mice, and APP/PS1 mice further substantiated the therapeutic potential of 8e for treating AD. To explore the underlying mechanisms of action, we applied proteomics analysis, revealing significant insights into the pathways influenced by compound 8e. These findings represent a substantial advancement in the design and development of highly specific and potent reversible BuChE inhibitors, positioning the newly developed inhibitor as a promising candidate for AD treatment while simultaneously indicating its potential to modulate additional signaling pathways.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of rational design of selective BuChE inhibitor for treating AD.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. SBP-based virtual screening

In this study, a highly selective BuChE inhibitor EC-7f (eqBuChE IC50 = 0.07 μmol/L) reported previously22 was selected as the temple for structure-based pharmacophore (SBP) virtual screening (Supporting Information Fig. S1A). Firstly, a redocking study on the human BuChE crystal structure (PDB ID = 4TPK) was conducted by CDOCKER. The results indicated that the highest-scoring conformation could accurately reproduce the original docking structure, with an RMSD of 0.82 Å. Subsequently, molecular docking studies on EC-7f were performed and six pharmacophore models were constructed based on its binding mode (Supporting Information Table S1). Based on the selectivity score, the Pharmacophore_01 with five chemical features was selected as the optimal model, which effectively captured the ligand–BuChE interactions observed at the center of the catalytic cavity. The chemical features identified were positive ionizable (PI), hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA), ring aromatic (RA) and two hydrophobic (HYP) (Fig. S1B and S1C). To further validate the accuracy of the pharmacophore model, we assessed the reliability of the SBP using 20 active compounds collected from PubChem and previous literature. The optimal model exhibited excellent sensitivity in predicting active compounds, with an accuracy rate of 80% for positive compounds.

After validating the 3D pharmacophore, the SBP-based virtual screening was conducted on six commercial compound databases: ChEMBL (33,750 compound), PubChem (22,320 compounds), DruglikeDiverse (5384 compounds), MinMaybridge (2000 compounds), Sample (81 compounds), and sc-PDB (5465 compounds). Initially, compounds that passed through the pharmacophore filter were ranked according to their pharmacophore fit value, only those scoring greater than 3 were retained. Drug-like descriptors following Lipinski's rules were applied to eliminate compounds with unfavorable physicochemical properties (Fig. S1D and S1E). After the initial screening, the virtual hits that were retained were docked into the BuChE active site using the CDOCKER to evaluate the binding modes, particularly focusing on the π–π interactions with Trp82, a crucial catalytic residue of BuChE. Considering binding modes and a structural similarity, six candidate compounds were selected and purchased or synthesized for biological evaluation (Supporting Informaiton Table S2). The results indicated that most of the hit compounds demonstrated inhibitory activity against BuChE, with the hit compound V1 showing the highest inhibitory activity (eqBuChE IC50 = 0.66 μmol/L) and making it a suitable lead compound (Fig. S1F and S1G).

2.2. Chemical synthesis and structure modification

Based on the results of virtual screening, the hit compound V1 was identified from six commercial databases. Subsequent structural modifications were undertaken to enhance its inhibitory potency against the target enzyme. V1 demonstrated a notable BuChE inhibitory effect, with an IC50 value of 0.66 μmol/L. As presented in Fig. 2A, analysis of the binding mode of V1 to BuChE revealed that the compound effectively occupied the target cavity, engaging with several critical amino acid residues including Trp82, Asp70, Trp231, Leu286, Val288, Ser198 and His438. Notably, the benzene ring of amine-alkoxy side chain (Moiety A) interacted with Trp82 through a π–π stacking interaction within the choline-binding pocket, suggesting its significance as the primary active site. Additionally, the piperidine component of amine-alkoxy side chain (Moiety A) interacted with His438 via a π–alkyl interaction, which was integral to the catalytic site. The benzamide moiety (Main modification site) occupied the acyl-binding pocket and might contribute to the selectivity of BuChE over AChE due to the subtle differences in residue composition between the two enzymes. Moreover, the benzylpiperidine group (Moiety B) projected into a solvent-exposed region and did not establish strong intermolecular interactions with key residues within the peripheral anionic site (PAS). This observation indicated that the hit compound V1 deserved for further compounds 7a–7j, 8a–8k, 9a–9c and 10a–10f mentioned in this study have been prepared through the synthetic pathways as shown in Scheme 1, Scheme 2, Scheme 3, Scheme 4. To investigate the significance of the benzoic acid skeleton and the methoxy group on the benzene ring, the synthetic routes for derivatives 7a–7j are outlined in Scheme 1. The commercially available 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoic acid (1a), or syringic acid (1b), was reacted with various secondary amines (2a–2c) in the presence of EDCI and HOBT to yield compounds 3a–3d. These intermediates were subsequently treated with 1,4-dibromobutane (4a) in the presence of K2CO3 in CH3CN to produce compounds 5a–5d. Finally, target compounds 7a–7j were synthesized by reacting 5a–5d with different secondary amines (6a–g) in the presence of CH3CN and K2CO3.

Figure 2.

Computational chemistry revealed the binding modes of 8e. (A) Key residues of human BuChE (PDB code: 4TPK) and modification strategy for derivative design based on hit compound V1 structure. (B) The performance of the optimal QSAR model on the training and test dataset. Experimental vs. predicted –log10 (IC50) of the 19 training (left) and 13 test (right) samples. (C) Key molecular fragments derived from permutation feature importance. (D) Chemical structures of the top 8 fragments. (E) Key molecular fingerprints are shown in color in a 2D schematic. (F) The root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) of protein Cα during 50 ns MD simulations. Error bars represent standard deviation of three experiments. (G) The lowest energy binding mode of 8e–BuChE complex. The compound is shown in yellow stick mode. Key residues of BuChE are depicted in cyan stick mode. The hydrogen bond and π–π interactions were represented as dark and orange dashed line, respectively. (H) Total binding free energy and its component. (I) Residue contribution of hot residues for receptor–ligand combination.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of target compounds 7a–7j. Reagents and conditions: (i) EDCI, HOBt, THF, room temperature, overnight; (ii) K2CO3, CH3CN, reflux, for 8–12 h; (iii) K2CO3, CH3CN, reflux, for 6–10 h.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of target compounds 8a–8k. Reagents and conditions: (i) EDCI, HOBt, THF, room temperature, overnight; (ii) K2CO3, CH3CN, reflux, for 8–12 h; (iii) K2CO3, CH3CN, reflux, for 6–12 h.

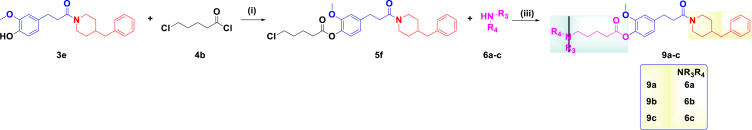

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of target compounds 9a–9c. Reagents and conditions: (i) K2CO3, CH3CN, reflux, for 8 h; (ii) K2CO3, CH3CN, reflux, for 8–12 h; (iii) K2CO3, CH3CN, reflux, for 6–12 h.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of target compounds 10a–10f. Reagents and conditions: (i) K2CO3, CH3CN, reflux, for 8–12 h; (ii) K2CO3, CH3CN, reflux, for 6–12 h.

To further explore the structure–activity relationships (SAR), we introduced the 3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)propanoic amide skeleton, detailing the synthesis of target compounds 8a–8k and 9a–9c in Scheme 2, Scheme 3. In Schemes 2, 3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)propanoic acid (1c) served as the starting material, and compounds 8a–8k were synthesized following the routes established for derivatives 7a–7j. Scheme 3 outlines the preparation of compounds 9a–9c, where compound 3e was reacted with 5-chlorovaleryl chloride (4b) in the presence of DMF and Cs2CO3 to afford compound 5f. This intermediate was then treated with various secondary amines (6a–c) in the presence of CH3CN and K2CO3 to yield the target compounds.

To assess the impact of the CH2 linker length, the synthesis of target derivatives 10a–f was presented in Scheme 4. Starting from compound 3f, various dibromo derivatives (4c–4h) were reacted in the presence of CH3CN and K2CO3 to produce compounds 5g–5l. These intermediates were then treated with N-ethylbenzylamine (6e) in the presence of K2CO3 and CH3CN, resulting in the desired derivatives 10a–10f.

2.3. In vitro AChE/BuChE inhibition by target compounds

All synthetic compounds were evaluated for their AChE and BuChE inhibitory potency using Ellman's assay, with the marketed drugs donepezil and rivastigmine serving as positive controls22. AChE was sourced from Electrophorus electricus (eeAChE) and human (huAChE), while BuChE was obtained from equine serum (eqBuChE) and human serum (huBuChE). In the evaluation of derivatives 7a–7j, it was observed that both the 3-methoxybenzoic amide skeleton and the number of methoxy groups significantly influenced AChE and BuChE inhibitory activities, as summarized in Table 1. Compounds 7a–7j exhibited moderate eeAChE inhibitory activity, with IC50 values ranging from 7.9 to 1.9 μmol/L. Notably, the amino fragment of the aminoalkoxy side chain had a minor impact on eeAChE inhibitory potency, following this trend: 3,5-dimethylpiperidine (7g, IC50 = 2.3 μmol/L) > N-ethylbenzylamine (7e, IC50 = 2.8 μmol/L) > 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline (7d, IC50 = 3.1 μmol/L) > 4-(3-phenylpropyl)piperidine (7c, IC50 = 3.4 μmol/L) > 4-benzylpiperidine (7a, IC50 = 5.9 μmol/L)> benzylpiperazine (7b, IC50 = 7.9 μmol/L) > diethylamine (7f, IC50 = 8.6 μmol/L). Moreover, compounds 7a, 7d, and 7e exhibited strong eqBuChE inhibitory potency with IC50 values of 0.66, 0.85, and 0.47 μmol/L, respectively. In contrast, compounds 7b (IC50 = 8.6 μmol/L), 7c (IC50 = 1.1 μmol/L), 7f (IC50 = 6.4 μmol/L), and 7g (IC50 = 3.7 μmol/L) demonstrated moderate eqBuChE inhibitory activity. Notably, compound 7e displayed the most potent eqBuChE inhibition (IC50 = 0.47 μmol/L). Building upon this, compound 7e was selected for further modification. When a methoxy group was added to the benzene ring of 7e to produce compound 7h, eqBuChE inhibitory activity slightly decreased to 0.77 μmol/L. Subsequently, replacing the 4-benzylpiperidine (NR1R2 fragment) of 7h with 4-amino-1-benzylpiperidine and 1-(4-fluorophenyl)piperazine yielded compounds 7i and 7j, which exhibited decreased eqBuChE inhibitory activities of 2.6 μmol/L and 6.3 μmol/L, respectively. Meanwhile, the compounds 7h–7j maintained moderate eeAChE inhibitory potencies, with IC50 values of 1.9, 5.7, and 6.9 μmol/L, respectively.

Table 1.

The AChE/BuChE inhibition by target compounds and the positive drugs.

| Compound | IC50 ± SDa (μmol/L) |

SId | IC50 ± SDa (μmol/L) |

SId | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eeAChEb | eqBuChEc | huAChEe | huBuChEf | |||

| 7a (V1) | 5.9 ± 0.36 | 0.66 ± 0.03 | 8.9 | – | – | |

| 7b | 7.9 ± 0.25 | 3.1 ± 0.12 | 2.5 | – | – | |

| 7c | 3.4 ± 0.13 | 1.1 ± 0.06 | 3.1 | – | – | |

| 7d | 3.1 ± 0.15 | 0.85 ± 0.02 | 3.6 | – | – | |

| 7e | 2.8 ± 0.13 | 0.47 ± 0.05 | 6.0 | 3.9 ± 0.44 | 0.87 ± 0.23 | 4.5 |

| 7f | 8.6 ± 0.32 | 6.4 ± 0.24 | 1.3 | – | – | |

| 7g | 2.3 ± 0.12 | 3.7 ± 0.24 | 0.6 | – | – | |

| 7h | 1.9 ± 0.07 | 0.77 ± 0.05 | 2.5 | – | – | |

| 7i | 5.7 ± 0.03 | 2.6 ± 0.12 | 2.2 | – | – | |

| 7j | 6.9 ± 0.04 | 6.3 ± 0.32 | 1.1 | – | – | |

| 8a | 1.7 ± 0.01 | 0.093 ± 0.005 | 18 | 5.9 ± 0.26 | 0.16 ± 0.43 | 37 |

| 8b | 5.8 ± 0.35 | 3.3 ± 0.13 | 1.8 | – | – | |

| 8c | 4.2 ± 0.26 | 0.063 ± 0.005 | 67 | 6.7 ± 0.16 | 0.082 ± 0.007 | 82 |

| 8d | 6.2 ± 0.12 | 0.087 ± 0.002 | 71 | 8.6 ± 0.33 | 0.097 ± 0.52 | 89 |

| 8e | 4.6 ± 0.03 | 0.049 ± 0.003 | 94 | 5.7 ± 0.08 | 0.066 ± 0.003 | 86 |

| 8f | 8.4 ± 0.53 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 30 | – | – | |

| 8g | 6.5 ± 0.33 | 0.75 ± 0.02 | 8.7 | – | – | |

| 8h | 4.7 ± 0.28 | 0.13 ± 0.08 | 36 | 6.9 ± 0.14 | 0.19 ± 0.19 | 36 |

| 8i | 7.6 ± 0.22 | 0.89 ± 0.03 | 8.5 | – | – | |

| 8j | 4.9 ± 0.18 | 0.31 ± 0.12 | 16 | – | – | |

| 8k | 5.5 ± 0.23 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 22 | – | – | |

| 9a | 7.1 ± 0.15 | 0.82 ± 0.03 | 8.7 | – | – | |

| 9b | 1.9 ± 0.11 | 1.7 ± 0.06 | 1.1 | – | – | |

| 9c | 8.1 ± 0.43 | 0.73 ± 0.23 | 11 | – | – | |

| 10a | 3.6 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 16 | – | – | |

| 10b | 8.7 ± 0.01 | 0.068 ± 0.005 | 128 | 5.9 ± 0.26 | 0.091 ± 0.008 | 65 |

| 10c | 6.2 ± 0.12 | 0.077 ± 0.002 | 81 | 8.6 ± 0.33 | 0.11 ± 0.52 | 78 |

| 10d | 4.6 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.003 | 38 | – | – | |

| 10e | 8.4 ± 0.53 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 30 | – | – | |

| 10f | 4.7 ± 0.28 | 0.59 ± 0.08 | 8.0 | – | – | |

| Donepezil | 0.013 ± 0.0009 | 6.3 ± 0.27 | 0.002 | 0.016 ± 0.0006 | 8.7 ± 0.35 | 0.002 |

| Rivastigmine | 8.9 ± 0.27 | 5.6 ± 0.14 | 1.6 | 12.6 ± 0.34 | 6.2 ± 0.21 | 2.0 |

IC50 values represent the concentration of inhibitor required to decrease enzyme activity by 50% and each performed in triplicate (SD = standard deviation).

eeAChE from electrophorus electricusc.

eqBuChE from equine serum.

SI = Selectivity Index = IC50 (BuChE)/IC50 (AChE).

huAChE from human erythrocytes.

huBuChE from human BuChE.

To further investigate the influence of the 3-(3-methoxyphenyl)propionic amide skeleton and the NR3R4 fragment, compounds 8a–8k and 9a–9c were synthesized and evaluated for their inhibitory activities. As listed in Table 1, compounds 8a–8k exhibited good to excellent inhibitory activity against eqBuChE, with IC50 values ranging from 0.049 to 3.3 μmol/L, indicating that the 3-(3-methoxyphenyl)propionic amide skeleton significantly contributed to the eqBuChE inhibitory potency. Notably, the NR3R4 fragments also impacted the inhibitory efficacy, compounds 8a, 8c, 8d, and 8e demonstrated exceptional eqBuChE inhibitory activities with IC50 values of 0.093, 0.063, 0.087, and 0.049 μmol/L, respectively. Compounds 8f, 8g, 8h, 8i, 8j, and 8k exhibited good eqBuChE inhibitory potency, with IC50 values of 0.28, 0.75, 0.13, 0.89, 0.31, and 0.25 μmol/L, while compound 8b showed moderate inhibitory activity with an IC50 of 3.3 μmol/L. Additionally, compounds 8a–8k displayed moderate inhibition of eeAChE, with IC50 values ranging from 1.7 to 8.4 μmol/L. Furthermore, the modification of the alkoxy side chain to an ester linkage in compounds 9a–9c yielded promising eqBuChE inhibitory potency, with IC50 values of 0.82, 1.7, and 0.73 μmol/L, alongside moderate eeAChE inhibition. Overall, compound 8e emerged as the most promising selective eqBuChE inhibitor, demonstrating exceptional potential in this category of compounds.

To further investigate the significance of the CH2 linker length (n), compounds 10a–10f were synthesized and evaluated based on compound 8e. As shown in Table 1, eqBuChE inhibitory potency improved progressively as the CH2 linker length increased from 2 to 4, with the following IC50 values: 10a (n = 2, IC50 = 0.22 μmol/L) < 10b (n = 3, IC50 = 0.068 μmol/L) < 8e (n = 4, IC50 = 0.049 μmol/L). However, eqBuChE inhibitory activity decreased as the CH2 linker length further increased from 4 to 10, with the observed IC50 values being: 10f (n = 10, IC50 = 0.59 μmol/L) < 10e (n = 9, IC50 = 0.28 μmol/L) < 10d (n = 6, IC50 = 0.12 μmol/L) < 10c (n = 5, IC50 = 0.077 μmol/L) < 8e (n = 4, IC50 = 0.049 μmol/L). These results indicated that the optimal linker length was n = 4. Additionally, compounds 10a–10f displayed moderate eeAChE inhibition, with IC50 values ranging from 8.7 to 3.6 μmol/L.

In summary, SAR analysis revealed that the 3-(3-methoxyphenyl)propionic amide skeleton was advantageous for eqBuChE inhibition, with the preferred NR1R2 fragment being 4-benzylpiperidine and the optimized NR3R4 fragment identified as N-ethylbenzylamine. The optimal CH2 linker length for the alkoxy side chain was confirmed as n = 4. Furthermore, the representative compounds 7e, 8a, 8c, 8d, 8e, 8h, 11b, and 11c were selected for further evaluation against huAChE and huBuChE. As indicated in Table 1, these compounds displayed slightly weaker huBuChE inhibitory potency compared to their eqBuChE inhibition. Notably, compound 8e demonstrated the highest huBuChE inhibitory activity (IC50 = 0.066 μmol/L), deserving for further investigations.

2.4. Computational chemistry revealed the binding modes of 8e

Herein, quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) analyses were performed to elucidate the critical structural determinants of BuChE inhibitors23. A total of 31 BuChE inhibitors were divided into training and test sets at a ratio of 6:4 to ensure robust model validation and generalizability. Prior to QSAR modeling, each molecular structure was encoded using 128-bit Morgan fingerprints. Support vector machine (SVM) regression was then employed to delineate the relationship between molecular descriptors and inhibitory potency. Hyperparameter optimization was executed via grid search with 3-fold cross-validation to maximize predictive accuracy. The optimal model demonstrated outstanding performance, with coefficient of determination (R2) values of 0.77 and 0.65 for the training and test sets, respectively (Fig. 2B). This high correlation across both datasets underscored the model's capability to effectively capture the underlying structure–activity relationships.

Subsequently, the permutation feature importance algorithm was utilized to identify the most significant molecular fingerprints contributing to BuChE inhibition. This methodology evaluated the impact of individual features on model performance through iterative randomization of the training set. Fig. 2C and D illustrates eight fragments that significantly contribute to the anti-BuChE activity of the compounds within the training samples. The analysis revealed that molecular fragments containing aromatic rings and ester moieties were essential for inhibitory activity. Notably, phenyl rings (No. 54), piperidine (No. 117/120), and phenyl ester (No. 3 and No. 96/120) groups emerged as the most impactful structural elements in inhibiting BuChE (Fig. 2E).

The binding stability between compound 8e and BuChE was assessed in GROMACS 2022.5. During the 50 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, the system remained in a stable state (Supporting Information Fig. S2). The root mean square deviation (RMSD) of complex and protein fluctuation remained less than 2 Å during last 20 ns, suggesting the binding of 8e with BuChE had stabilized (Fig. 2F and Supporting Information Fig. S3). The lowest energy conformation revealed that the compound 8e snugly fits into a hydrophobic pocket formed by residues Trp82, Pro285, Ile441, and Tyr332, establishing π–π stacking interactions with Trp82. Notably, the aromatic fragments (Nos. 3 and 88) predominantly acted as hydrophobic groups, while the carbonyl and piperidine fragments (Nos. 96 and 120), exposed to solvent-accessible regions, facilitate polar interactions (Fig. 2E–G). The total binding free energy was −36.13 kcal/mol, and the van der Waals energy (−51.91 kcal/mol) played a central role in ligand-receptor binding (Fig. 2H). Moreover, it was worth noting that Trp82 (−2.56 kcal/mol), Pro285 (−1.25 kcal/mol) and Gly439 (−1.60 kcal/mol) contributed significantly to the interaction of 8e with the BuChE (Fig. 2I).

2.5. Compound 8e is a selective BuChE inhibitor

The selectivity of compound 8e towards huBuChE was evaluated against several key human serine hydrolases, including human acetylcholinesterase (huAChE), human carboxylesterase 1 (huCES1A), human carboxylesterase 2 (huCES2A), human Notum (huNotum), human pancreatic lipase (huPL), and human thrombin (huThrombin)24. As presented in Supporting Information Table S3, 8e exhibited moderate inhibitory activity against huAChE (IC50 = 5.7 μmol/L), huCES1A (IC50 = 21.8 μmol/L), and huCES2A (IC50 = 0.8 μmol/L). Notably, this compound demonstrated negligible inhibitory effects on huNotum, huPL, and huThrombin at a concentration of 100 μmol/L. These findings indicated that 8e exhibited high specificity towards huBuChE.

2.6. Compound 8e is a reversible BuChE inhibitor

To determine whether compound 8e was a reversible BuChE inhibitor, we assessed the recovery of BuChE activity following dilution over time25. As shown in Fig. 3A, the BuChE activity at 0.1 × IC50 of rivastigmine remained relatively unchanged over 120 min. In contrast, 0.1 × IC50 of donepezil significantly restored BuChE activity from 51.3% to 68.2% as the time progressed, indicating its reversible inhibition of BuChE. Similarly, compound 8e demonstrated a comparable recovery, restoring BuChE activity from 50.4% to 71.8% over the same period. These results conclusively demonstrated that compound 8e was a reversible BuChE inhibitor.

Figure 3.

(A) The recovery of BuChE inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine and 8e) inhibition after dilution with time monitoring. (B) The cell viability (%) of 8e on HT22 cells, PC12 cells and SH-SY5Y cells. (C) Neuroprotective effects of 8e and donepezil on Glu-induced HT22 cell injury. (D) Neuroprotective effects of 8e and donepezil on Aβ25–35-induced HT22 cell injury. (E) Neuroprotective effects of 8e on Aβ25–35-induced PC12 cell injury. (F) The chemical stability of 8e in artificial gastrointestinal fluid. (G) The metabolic stability of 8e in human/rat liver microsomes. (H) The CYP inhibition effects of 8e. (I) In vivo PET-CT images of [11C]8e in mice brain after intravenous administration and time–activity curve. Values are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ##P < 0.01 vs. control group; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. model group.

2.7. Compound 8e exhibits notable neuroprotecitve effects

The cytotoxicity of compound 8e was evaluated using the CCK-8 assay across HT22, PC12, and SH-SY5Y cell lines. As illustrated in Fig. 3B, compound 8e demonstrated a favorable in vitro safety profile, exhibiting low cytotoxicity at concentrations below 20 μmol/L.

Emerging evidence indicated that glutamate-mediated neurotoxicity played a critical role in neuronal loss associated with AD26. As presented in Fig. 3C, preincubation with 8e (16, 8, and 4 μmol/L) significantly rescued l-Glu-induced HT22 cell injury in a dose-dependent manner, outperforming established positive controls such as donepezil and rivastigmine. Additionally, Aβ25–35, a fragment derived from Aβ1–42, exhibited neurotoxic properties similar to its full-length counterpart and was frequently employed to model the pathological changes of AD in vitro27. As shown in Fig. 3D and E, compound 8e exhibited substantial neuroprotective effects against Aβ25–35-induced cellular injury in HT22 and PC12 cells, also in a dose-dependent manner.

2.8. Compound 8e shows favorable druggability

The stability and potential drug–drug interactions of compound 8e were systematically investigated to assess its druggability. The chemical stability and metabolic resilience of 8e were evaluated under simulated gastrointestinal and liver conditions. As shown in Fig. 3F and G, compound 8e exhibited good chemical stability in artificial gastric fluid and demonstrated strong resistance to metabolism by human/rat liver microsomes28,29. Furthermore, as listed in Fig. 3H, 8e mildly inhibited CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 at 1 μmol/L, while did not significantly inhibit other key cytochrome P450 enzymes, including CYPs 1A2, 2A6, 2C8, 2C9, 2D6, and 2E130.

2.9. Compound 8e presents good blood–brain barrier permeability

To evaluate the BBB permeability of 8e, we conducted both the parallel artificial membrane permeation assay of the blood–brain barrier (PAMPA–BBB) and in vivo PET-CT imaging assays31, 32, 33. For the PAMPA–BBB assay, our previous research established a method indicating that derivatives with permeability (Pe) > 3.44 × 10−6 cm/s exhibited high BBB permeation31. The results presented in Supporting Information Table S4 indicated that the permeability of 8e was 8.62 × 10−6 cm/s, suggesting good BBB permeability. Furthermore, PET-CT imaging (Fig. 3I) was conducted in mice using [11C]8e34,35. Details regarding the radiosynthesis of [11C]8e are provided in the Supporting Information. The uptake of [11C]8e in the mice brain reached a maximum of 7% ID/cc at around 2 min after injection, and sustained binding over the scanning time (60 min), suggesting that [11C]8e exhibited excellent permeability across the BBB and showed rapid uptake following intravenous administration. Therefore, both the PAMPA–BBB assay and PET-CT imaging strongly indicated that 8e possessed commendable BBB permeability, underscoring its potential as an effective therapeutic candidate for central nervous system targeting.

To comprehensively evaluate the in vivo anti-AD efficacy of compound 8e, we used zebrafish, Kunming mice, and APP/PS1 transgenic mice as model organisms.

2.10. 8e significantly alleviates cognitive impairment on zebrafish AD models

2.10.1. Knockdown of the BuChE gene significantly enhanced the zebrafish AD model

Utilizing zebrafish for the rapid screening of drug candidates allows for the efficient assessment of both efficacy and side effects, thereby mitigating development risks in the early stages of drug discovery36. Firstly, to evaluate the therapeutic potential of BuChE as a target for AD, we successfully established both an AlCl3-induced zebrafish AD model and a BuChE-overexpression zebrafish model. Behavioral assessments were conducted over a 60-min timeframe, alternating between light (10 min) and dark (10 min) conditions (Fig. 4A). Specially, as exhibited in Fig. 4B–G, knocking down the BuChE gene in the two models significantly enhanced the swimming distance and swimming speed under light and dark conditions, respectively. Moreover, Fig. 4H and I exhibited that knocking down the BuChE gene significantly improved reaction capacity during the light environment transitioned to dark environment, suggesting that dark conditions contributed positively to reaction capacity. Further, Fig. 4J demonstrated a significant reduction in BuChE activity following the knockdown of the BuChE gene in both AlCl3-induced and BuChE-overexpression models, corroborating the behavioral outcomes observed. These findings confirmed that reducing BuChE activity was an effective strategy for treating AD.

Figure 4.

Effects of knocking down BuChE gene on the zebrafish AD model. (A) Behavioral changes in the zebrafish larvae per minute. (B–D) The swimming distance under light, dark or total conditions. (E–G) The swimming speed under light, dark or total conditions. (H, I) Reaction capacity changes during the transitions between light and dark conditions. (J) BuChE activity changes in the various zebrafish models. (K) Effects of 8e on the survival rate of zebrafish embryos. (L) Effects of 8e on morphological changes in zebrafish. Scale bar = 200 μm. (M) Pericardial edema/body length changes after treatment with 8e. (N) Swim bladder area changes. (O) Liver fluorescence area changes. (P) Fluorescence intensity changes. (Q) Effects of 8e on morphological changes in liver. Values are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Scale bar = 200 μm ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 vs. control group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. zebrafish AD model group.

2.10.2. Compound 8e exhibits a favorable safety profile in zebrafish

To investigate the safety profile of compound 8e, we assessed its effects using six concentrations (0.3, 0.6, 1.6, 2.5, 5.0, and 10.0 μg/mL) to determine percent survival (%), as displayed in Fig. 4K, there was no zebrafish died at concentrations below 5.0 μg/mL. Subsequently, as presented in Fig. 4L–N, the safe concentration was less than 2.5 μg/mL through evaluating pericardial edema/body length, and swim bladder area. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 4O–Q, the liver fluorescence area and fluorescence intensity did not exhibit significant changes at concentrations of 0.25, 1.25, and 2.5 μg/mL. Collectively, these results suggest that the maximum tolerable concentration (MTC) of compound 8e was 2.5 μg/mL.

To evaluate the in vivo efficacy of 8e, we successfully constructed BuChE-overexpression and AlCl3-induced zebrafish AD model, respectively. Based on the established MTC of 2.5 μg/mL for 8e, we selected three concentrations (0.1, 0.25, and 0.5 μg/mL) for further assessment after preliminary screening.

2.10.3. Efficacy of 8e in the BuChE-overexpression zebrafish model

Behavioral tests results of 8e in the BuChE-overexpression model were presented over a 60-min period of alternating light and dark conditions (Fig. 5A). As shown in Fig. 5B–G, compound 8e, especially the dose of 0.25 μg/mL, significantly improved swimming distance/swimming speed under light and dark conditions, respectively, which was better that donepezil (3.0 μg/mL). Moreover, Fig. 5H and I exhibited that 8e significantly enhanced reaction capacity compared to the BuChE-overexpression zebrafish group during the transition from light to dark. Furthermore, Fig. 5J illustrated that 8e markedly decreased BuChE activity, demonstrating superior efficacy compared to donepeizl. This enhanced reduction in BuChE activity might be attributed to the fact that donepezil primarily functioned as a selective AChE inhibitor, whereas 8e exhibited a more pronounced inhibitory effect on BuChE. Overall, these findings confirmed that compound 8e effectively enhanced the behavioral performance in BuChE-overexpression zebrafish AD models by inhibiting BuChE.

Figure 5.

Effects of 8e in the BuChE-overexpression zebrafish model. (A) Behavioral changes in the zebrafish larvae per minute. (B–D) The swimming distance of 8e in the BuChE-overexpression model under light, dark or total conditions. (E–G) The swimming speed of 8e in the BuChE-overexpression model under light, dark or total conditions. (H, I) Reaction capacity changes during the transitions between light and dark conditions. (J) BuChE activity changes in the various groups. Values are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. control group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. BuChE-overexpression zebrafish group.

2.10.4. Compound 8e significantly improved AlCl3-induced zebrafish AD model

The effects of 8e on AlCl3-induced zebrafish AD model were presented in Fig. 6A over a 60-min period of alternating light and dark conditions. As demonstrated in Fig. 6B–G, donepezil (3.0 μg/mL) and 8e (0.1 and 0.25 μg/mL) significantly increased the swimming distance/swimming speed compared with the AlCl3-induced zebrafish AD group under light and dark conditions, respectively. Furthermore, Fig. 6H and I showed that donepezil (3.0 μg/mL) and 8e (0.1 and 0.25 μg/mL) significantly enhanced reaction capacity compared to the AlCl3-induced zebrafish AD group during the transition from dark to light.

Figure 6.

Effects of 8e in the AlCl3-induced zebrafish model. (A) Behavioral changes in the zebrafish larvae per minute. (B–D) The swimming distance of 8e in the AlCl3-induced zebrafish model under light, dark or total conditions. (E–G) The swimming speed of 8e in the AlCl3-induced zebrafish model under light, dark or total conditions. (H, I) Reaction capacity changes during the transitions between light and dark conditions. (J) The apoptotic body/normal cells in the various zebrafish models were statistically analyzed after HE staining. (K) Apoptotic body changes in the brain of zebrafish were performed using HE staining. Scale bar = 10 μm. (L) BuChE activity changes in various zebrafish group. (M) ACh level changes in various zebrafish group. (N) IL-6 mRNA expression changes in various zebrafish group. (O) TNF-α mRNA expression changes in various zebrafish group. (P) IL-1β mRNA expression changes in various zebrafish group. (Q) APP mRNA expression changes in various zebrafish group. (R) PS1 mRNA expression changes in various zebrafish group. (S) APOE mRNA expression changes in various zebrafish group. Values are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. control group. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. AlCl3-induced zebrafish model group.

After the behavioral tests, the brains of the zebrafish were processed to measure the concentration of the compounds. HPLC results indicated that the concentration of donepezil and compound 8e (low, medium, high dose) in the zebrafish brains was 328.6, 92.4, 336.0, and 666.5 ng/mL, respectively. Moreover, the HE staining results in Fig. 6J and K displayed that donepezil (3.0 μg/mL) and 8e (0.1, 0.25, and 0.5 μg/mL) significantly reduced the number of apoptotic cells, compared to model group. Furthermore, Fig. 6L and M suggest that 8e elevated the level of ACh by inhibiting BuChE, thereby exerting anti-AD effects. Additionally, 8e demonstrated significant anti-inflammatory effects (Fig. 6N–P), evidenced by reduced levels of IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β. Compound 8e was also found to lower the levels of APP, PS1 and APOE (Fig. 6Q–S).

In summary, these findings suggest that the BuChE inhibitor 8e held promise as a potential therapeutic agent in the zebrafish AD models, with significant implications for further exploration of its mechanisms of action.

2.11. In vivo assay in scopolamine-induced mice

2.11.1. Safety profile of compound 8e

To further evaluate the safety profile of compound 8e, acute toxicity studies were conducted using Kunming mice (18–22 g) at doses of 1000, 1500, and 2000 mg/kg. Following the administration of 2000 mg/kg, two mice exhibited drowsiness, one mouse experienced fluid loss and watery stool, and another mouse died one day after treatment. Importantly, after 14 consecutive days of daily gavage administration of 1500 mg/kg 8e, no significant effects were observed on body weight, mental state, or movement behaviors. These findings indicated that compound 8e exhibited no obvious toxicity at doses ≤1500 mg/kg.

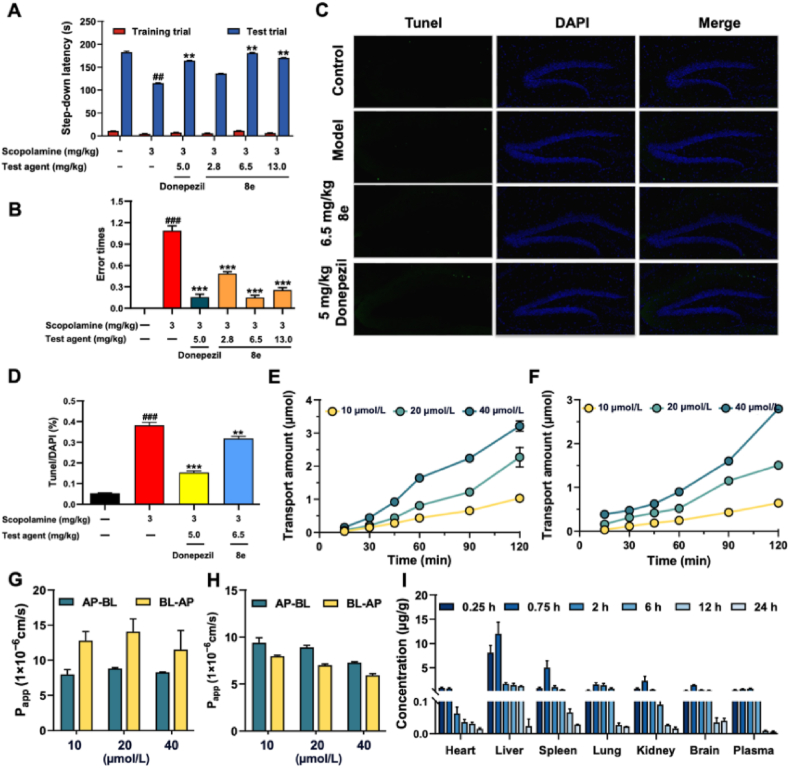

2.11.2. Compound 8e significantly improved scopolamine-induced mice dysmnesia

The step-down passive avoidance task was employed to assess the effects of 8e on scopolamine-induced dysmnesia model31,37,38. As illustrated in Fig. 7A and B, donepezil (5.0 mg/kg) and 8e (2.8, 6.5, and 13.0 mg/kg) markedly improved the latency time to 163.87 s (P < 0.01), 135.2 s, 180 s (P < 0.01), and 169.71 s (P < 0.01), respectively, compared with model group (114.51 s). And the number of errors also decreased to 0.1 (P < 0.001), 0.5 (P < 0.001), 0.1 (P < 0.001), and 0.3 (P < 0.001), respectively, compared with model group. Especially, the medium dose of 8e (6.5 mg/kg) significantly reversed scopolamine-induced cognitive deficits, similar to the effects observed with donepezil.

Figure 7.

Effects of 8e on scopolamine-induced mice dysmnesia using the step-down passive avoidance task. (A) The step-down lantancy changes in various group. (B) Error times changes in various group. (C, D) Neuronal apoptosis in the hippocampus was conducted and analyzed using TUNEL staining. (E, F) The cumulative transport of 8e on the AP-BL/BL-AP side was evaluated. (G, H) The permeability of compound 8e was evaluated using the Papp values. (I) The tissue distribution of compound 8e in SD mice (220–250 g) following oral administration at a dose of 25 mg/kg at various time points. Values are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Values are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. control group; ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. model group.

Histopathological studies in the hippocampus were conducted using TUNEL staining to assess neuronal apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 7C and D, donepezil (5.0 mg/kg) and 8e (6.5 mg/kg) significantly reduced neuronal apoptosis. Furthermore, as indicated in Supporting Information Fig. S4, immunohistochemical analyses revealed no significant inflammatory response, as indicated by the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Whereas, in the cerebral cortex, donepezil (5.0 mg/kg) and 8e (6.5 mg/kg) resulted in a significant reduction in the levels of these inflammatory markers compared to the control group.

2.12. Pharmacokinetic profile, absorption, distribution and metabolism of 8e

2.12.1. Pharmacokinetic properties of compound 8e

To investigate the pharmacokinetic properties of compound 8e, a preliminary pharmacokinetic analysis was conducted in SD rats39,40. The results in Table 2 indicate that 8e demonstrated a half-life (t1/2) of 12.699 h, a time to reach maximum concentration (Tmax) of 1.667 h (with Tmax < 1.0 h indicating rapid absorption), a maximum concentration (Cmax) of 847.948 μg/L, and a low absolute bioavailability (F) of 2.522%.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic profile of 8e in SD rats.

| Item | i.v.a (5 mg/kg) | i.g.b (25 mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| AUC0–t (μg/L·h) | 26316.837 ± 2047.419 | 3306.081 ± 203.384 |

| AUC0–∞ (μg/L·h) | 26324.634 ± 2043.348 | 3319.892 ± 203.289 |

| MRT0–t (h) | 1.476 ± 0.016 | 3.593 ± 0.041 |

| MRT0–∞ (h) | 1.492 ± 0.022 | 3.840 ± 0.041 |

| t1/2 (h) | 5.539 ± 0.797 | 12.699 ± 1.968 |

| CL (L/h/kg) | 0.001 ± 0.000 | 0.006 ± 0.000 |

| Vd (L/kg) | 0.006 ± 0.002 | 0.112 ± 0.015 |

| Cmax (μg/L) | 25807.432 ± 1697.585 | 847.948 ± 24.519 |

| tmax (h) | – | 1.667 ± 0.289 |

| F (%) | – | 2.522 |

i.v. = intravenous administration, n = 6.

i.g. = intragastrical administration, n = 6.

2.12.2. Absorption characteristics of 8e

The toxicity of compound 8e was evaluated in Caco-2 cells41. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S5, 8e did not exhibit significant toxicity to Caco-2 cells at a concentration of 80 μmol/L. As indicated in Supporting Information Table S5 and Fig. 7G, the Papp values of 8e at A→B side was (7.99–8.84) × 10−6 cm/s, suggesting that 8e possessed good permeability. Additionally, Fig. 7H indicate that the transport mechanism of 8e during absorption was primarily passive diffusion. Furthermore, as displayed in Fig. 7E and F, the cumulative transport of 8e on the AP-BL side was lower than that observed on the BL-AP side, with the efflux ratio (ER) consistently greater than 1.2. After co-incubation with Verapamil, a known P-glycoprotein (P-gp) inhibitor, the ER values decreased to below 1. These findings suggest that P-gp may mediated the efflux transport of 8e. Consequently, it was inferred that 8e demonstrated good permeability, with the majority being absorbed into the bloodstream following intragastric administration. However, a significant portion appeared to be excreted via the efflux protein P-gp post-absorption.

2.12.3. Tissue distribution of 8e in mice

The tissue distribution of compound 8e was investigated in SD mice (220–250 g) following oral administration at a dose of 25 mg/kg at various time points40. As illustrated in Fig. 7I, 8e exhibited rapid and widespread distribution across tissues, with the highest concentration observed in the liver. Importantly, 8e was able to penetrate the blood–brain barrier, and its concentration in the brain tissue was slightly higher than that in plasma. Additionally, the clearance rate of 8e in brain tissue was low following oral administration. Specifically, the concentration of 8e in brain tissue was 1400.55 ng/g after 0.75 h and remained at 300.799 ng/g after 6 h. These findings suggest that 8e effectively exerted its BuChE effects in the brain, potentially aiding in the treatment of AD.

2.12.4. Metabolism of 8e

The in vivo metabolism of 8e was examined in SD mice (220–250 g) after oral administration25,31. Supporting Information Table S6 summarizes the excretion rates in feces and urine over a 48-h period following intragastric administration of 8e (25 mg/kg). The results indicate a gradual decrease in urinary excretion accompanied by a corresponding increase in fecal excretion. However, the cumulative excretion rates in both feces and urine were very low, totaling only 1.4593% over the 48-h period. This suggests that 8e might primarily be excreted in the form of metabolites. Further analysis revealed that there was a total of 22 metabolites in feces, urine, and plasma (Supporting Information Fig. S6 and Table S7), including 15 phase I metabolites and 7 phase II metabolites.

2.13. In vivo effects of 8e in APP/PS1 mice

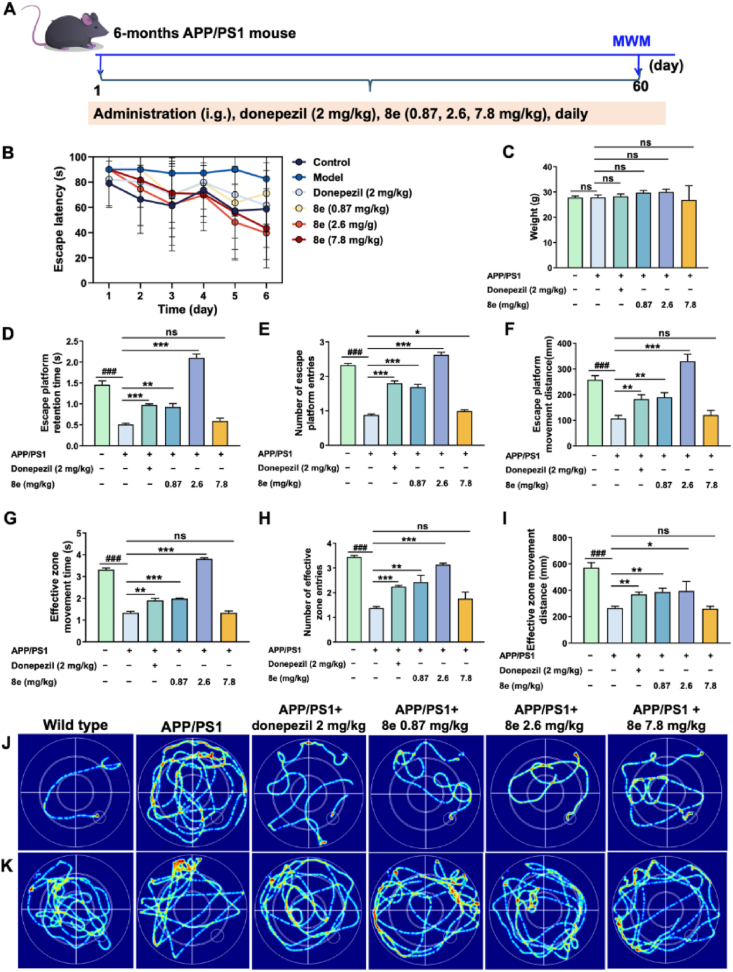

Based on the aforementioned in vivo results, compound 8e was further evaluated for its anti-AD effects in APP/PS1 double-transgenic mice using the Morris Water Maze (MWM) assay42,43. As exhibited in Fig. 8A, the learning abilities of the 6-month-old APP/PS1 mice, following oral administration of 8e (0.87, 2.6, and 7.8 mg/kg) or saline for two months, were assessed using the MWM. The donepezil group (2 mg/kg) served as the positive control, and wild-type C57BL/6 mice were included as the negative control. During the final week of treatment, we recorded the escape latency for the various experimental groups in the MWM assay (Fig. 8B). The results indicate that donepezil and 8e significantly decreased the escape latency compared with the model group. And Fig. 8C suggests that body weights remained unchanged compared to age-matched vehicle-treated controls. Moreover, Fig. 8D–I, compound 8e, especially the dose of 2.6 mg/kg, significantly improved escape platform retention times (P < 0.001), number of escape platform entries (P < 0.001), escape platform movement distance (P < 0.001), effective zone movement times (P < 0.001), number of effective zone entries (P < 0.001), and effective zone movement distance (P < 0.05) compared to APP/PS1 mice. And escape latency trace (Fig. 8J) and effective zone movement distance trace (Fig. 8K) were consistent with the results. Collectively, these observations and data indicated that compound 8e significantly enhanced spatial memory and cognitive function compared to donepezil at the tested dosages.

Figure 8.

In vivo effects of 8e in APP/PS1 mice. (A) The learning abilities of the 6-month-old APP/PS1 mice were assessed using the MWM. (B) The escape latency changes were recorded in various groups. (C) Weight changes were recorded in various experimental groups. In the MWM assay were recorded. (D–I) The effects of 8e to evaluate spatial memory and long-term memory by observing and recording escape platform retention times, number of escape platform entries, escape platform distance, effective zone movement times, number of effective zone entries and effective zone movement distance. (J) Escape latency trace in various group. (K) Effective zone movement distance trace in various group. Values are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ###P < 0.001 vs. wild-type C57BL/6 mice group; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. APP/PS1 mice group.

After the behavioral tests, the mice were euthanized, and various tissues were analyzed. As presented in Supporting Information Fig. S7, brain weight, brain index, liver weight, and liver index of compound-treated mice did not significantly differ from those of age-matched vehicle-treated controls. Tissues from the hippocampus and cerebral cortex were collected for further examination. HE staining (Fig. 9A and B) revealed that donepezil (2 mg/kg) and compound 8e (2.6 mg/kg) resulted in a marked decrease in the neuronal abnormalities within both the cerebral cortex and hippocampus compared to the APP/PS1 mice. Additionally, as illustrated in Fig. 9C–F, both qPCR and immunofluorescence staining exhibited that there were no significant differences in the relative expression levels of BuChE in the hippocampus across the various groups. However, compared to the wild-type mice, the relative expression levels of BuChE in the cerebral cortex of APP/PS1 mice were significantly elevated, which decreased after treatment with donepezil (2 mg/kg) and compound 8e (2.6 mg/kg). Given these results, we had chosen to focus our investigation on the cerebral cortex to further elucidate the efficacy and underlying mechanisms of the selective BuChE inhibitor 8e.

Figure 9.

In vivo effects of 8e in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex. (A, B) The expression of the neuronal abnormalities in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex were examined using HE staining. Scale bar = 50 μm. (C, D) The expression of BuChE in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex of APP/PS1 mice were examined using Immunofluorescence staining. Scale bar = 200 μm. (E) The expression of Aβ1–42 in the cerebral cortex were performed using immunofluorescence staining. (F) BuChE activity in hippocampus and cerebral cortex were analysed using qPCR. (G–K) The levels of ACh, Aβ1–42, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β in the cerebral cortex using ELISA kits were quantified. Values are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. APP/PS1 mice group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. wild-type C57BL/6 mice group.

Furthermore, Fig. 9E indicated that donepezil (2.0 mg/kg) and compound 8e (2.6 mg/kg) resulted in a significant reduction in Aβ1–42 levels. Fig. 9G displayed that donepezil and compound 8e led to a remarkable increase in ACh levels compared to the APP/PS1 model group. Moreover, as presented in Fig. 9H–K, both donepezil and compound 8e significantly reduced the levels of Aβ1–42, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β compared to the APP/PS1 mice. Further, blood samples were collected, and plasma was obtained for analysis. The levels of triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) were measured in the plasma. As illustrated in Supporting Information Fig. S8A, TG levels were significantly elevated in APP/PS1 mice compared to the control group. Treatment with donepezil and 8e led to a significant decrease in TG levels. Fig. S8B and S8C exhibites that the TC and LDL-c levels of APP/PS1 mice did not produce significant obvious compared to control group. When treated with donepezil and 8e, compound 8e (2.6 mg/kg) did not produce significant change, while donepezil (2.0 mg/kg) significantly reduced the levels of TC and LDL-c. Given the promising effects of 8e, we further explored its mechanism of action through a proteomic analysis of the cerebral cortex.

2.14. Proteomics analysis of 8e in the cerebral cortex

To identify the differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) regulated by 8e in the cerebral cortex tissues of mice, we conducted a 4D-label-free proteomics analysis on the collected samples44,45. A total of proteins were identified using a screening threshold, with a fold change (FC) ≥ 1.2 or FC ≤ 1/1.2 and a P value < 0.05. Compared to the control group, the model group exhibited an upregulation of 104 proteins and a downregulation of 130 proteins. When the medium dose group was compared to the control group, 91 proteins were found to be upregulated and 135 downregulated. Upon treatment with the medium dose (0.25 μg/mL) of compound 8e, 131 proteins were upregulated while 122 proteins were downregulated in comparison to the model group (Supporting Information Fig. S9A). These results were visualized through Volcano Plots (Fig. 10A–C). To gain further insights into the DEPs, we employed the Mfuzz clustering algorithm to categorize them into ten subclusters (Fig. 10D–N). Clusters 5 and 8 were selected to further investigate. Cluster 5 included 57 proteins that were downregulated in the model group but showed restored expression upon 8e treatment (Fig. S9B). Conversely, Cluster 8 comprised 67 proteins that were upregulated in the model group (Fig. S9C), which also exhibited attenuated expression after treatment with 8e (2.6 mg/kg). Further analysis of the proteins in Clusters 5 and 8 was performed through Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses. In Cluster 5, among the top 30 GO functional enrichment categories (Fig. S9D), we identified 10 categories linked to biological processes (BP), including protein localization to the nuclear envelope, dopamine biosynthesis, and negative regulation of amyloid fibril formation. Additionally, 10 cellular component (CC) categories were enriched, including cytosol, mitochondrion, and myelin sheath. Ten molecular function (MF) categories included protein-containing complex binding, unfolded protein binding, and 3′–5′ exonuclease activity. KEGG analysis indicated that treatment with 8e (2.6 mg/kg) influenced several signaling pathways associated with human diseases (Fig. S9E), such as Parkinson's disease, alcoholism, diabetic cardiomyopathy, Salmonella infection, and prion diseases. In Cluster 8, we similarly identified 10 biological process categories (Fig. S9F), including glutathione metabolic processes, responses to peptide hormones, and cellular responses to glucose stimuli. Consistent with Cluster 5, there were 10 enriched categories for cellular components and molecular functions, including identical protein binding, protein serine/threonine kinase activity, and protein kinase activity. The top 20 KEGG enrichment results (Fig. S9G), with a P-value <0.05 as the cutoff, revealed pathways related to drug metabolism, glutathione metabolism, autophagy, apelin signaling, and insulin signaling.

Figure 10.

The differentially expressed proteins were visualized through Volcano. (A) Compared with control group, the model group exhibited an upregulation of 104 proteins and a downregulation of 130 proteins; (B) 91 proteins were found to be upregulated and 135 downregulated between the 8e and control group; (C) 131 proteins were upregulated while 122 proteins were downregulated in comparison to the model group; (D–N) Plots Cluster analysis of all proteins based on their expression level change patterns using Mfuzz and hierarchical clustering.

Further investigation identified specific proteins from Clusters 5 and 8 that were differentially expressed and closely associated with the progression of AD. As listed in Fig. 11A–G, notable proteins included P56565 (S100A1), which modulated neuroinflammation and histopathology in AD mouse models46; Q9CWM4 (Pfdn1), identified as a novel AD locus47; P09470 (ACE), implicated as a causal factor in AD48; P18894 (DAO), which regulated NMDA receptor function and exhibited increased levels in relation to cognitive deficits49; P98156 (VLDLR), which played critical roles in brain development and adult synaptic plasticity through Reelin signaling50; Q04736 (YES1), shown to be upregulated in AD51; Q61176 (ARG1), serving as a marker for microglial M2-type polarization52 and Q8BFP9 (PDK1), activated in AD53. To validate our findings, we performed qPCR (Fig. 11H) and Western blot analyses (Fig. 11I) on seven DEPs extracted from the cerebral cortex of rats. The results corroborated the proteomic data, indicating that the proteins P98156 (VLDLR), and Q9CWM4 (Pfdn1) aligned with the proteomic analysis. Notably, Q9CWM4 (Pfdn1) was recognized as a novel AD locus, yet lacked documented associated signaling pathways. Additionally, P98156 (VLDLR) was closely linked to the onset and progression of AD, primarily through mediation of Reelin signaling, which was involved in neurodevelopment, neurogenesis, and neuronal plasticity. Accumulating evidence suggests that the Reelin pathway interconnected ApoE4, Aβ, and Tau—key proteins implicated in the pathogenesis of AD50. Therefore, we proposed that the mechanism of action for compound 8e might involve modulation of the Reelin-mediated PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (Fig. 11J), warranting further investigation.

Figure 11.

The mechanism of action of 8e. (A–G) The expression of identified differentially expressed proteins (Pfdn1, Ace, Dao, Vldlr, Yes1, Arg1, and Pdk1) closely related to the progression of AD. (H) The expressions of pfdn1 and VLDLR in cerebral cortex were determined by qPCR. (I) The expressions of pfdn1 and VLDLR in cerebral cortex were detected by Western blot. (J) The schematic diagram of the possible mechanism of action for compound 8e. Values are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. control group; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 vs. model group.

3. Conclusions

AD is a prevalent, chronic, and progressive neurodegenerative disorder predominantly affecting the elderly population. Its complex etiology poses significant challenges, and currently, there are no effective therapeutics available. BuChE is thought to play a compensatory role in the hydrolysis of acetylcholine ACh, and the positive correlation between BuChE activity and Aβ deposition may contribute to the disease's progression, positioning BuChE as a promising therapeutic target for AD. In this study, we identified the selective BuChE inhibitor, compound 8e (eqBuChE IC50 = 0.049 μmol/L, huBuChE IC50 = 0.066 μmol/L), through a combination of virtual screening and structural optimization. Compound 8e was a reversible BuChE inhibitor that exhibits favorable BBB permeability, good metabolic stability, and weak CYP inhibition. We further demonstrated that knockdown of the BuChE gene significantly enhanced therapeutic efficacy in zebrafish AD model. Specifically, compound 8e showed potent effects in both BuChE-overexpression and AlCl3-induced zebrafish AD models, as well as notable alleviation of scopolamine-induced cognitive impairments in murine models. However, pharmacokinetic studies revealed that compound 8e had limited oral bioavailability. Importantly, compound 8e significantly improved cognitive function in APP/PS1 double transgenic mice. Proteomic analyses indicated that treatment with 8e led to an increase in VLDLR protein levels, suggesting that 8e might modulate the reelin-mediated PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. These findings collectively suggest that compound 8e was a potent reversible BuChE inhibitor that exhibited high specificity, improved drug-like properties, and a favorable safety profile, demonstrating significant therapeutic effects in vivo. Moreover, proteomic analysis revealed that 8e modulated additional signaling pathways, reinforcing its potential as a promising drug candidate for the amelioration of AD, and warranting further in-depth investigation.

4. Experimental

4.1. Chemistry

The available reagents and solvents were purchased from Shanghai Titan Scientific Co., Ltd., Energy Chemical, Bidepharm and Sigma–Aldrich. All the reactions were monitored by TLC and the mixture was treated to obtain residue after the reaction completed. The crude was purified by column chromatography using silica gel (230–400 mesh) purchased from Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co., Ltd. (China). MS spectra were obtained on an Agilent-6210 TOF LC–MS spectrometer. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian INOVA spectrometer, using TMS as an internal standard at 400 and 100 MHz, respectively.

The purity of target compounds was over 96% by HPLC analysis. To a mixture of the corresponding secondary amines NR3R4 6 (6a–6k) (1.1 mmol) and anhydrous K2CO3 (1.2 mmol) in anhydrous CH3CN (12 mL) were added the appropriate intermediates 5a–5l (1.0 mmol). The reaction mixture was then heated at 85 °C for 6–12 h. After complete reaction, the mixture and filtrated. The filtrate was concentrated to get the crude product, which was further purified on a silica gel chromatography using petroleum ether/acetone (50:1) as eluent to afford the target compounds 7a–7j, 8a–8k, 9a–c and 10a–10f.

The synthesis of compounds 3a–3e, 5a–5l, 7a–7j, 8a–8k, 9a–9c and 10a–10f could be found in Supporting Information.

4.2. SBP-base virtual screening and QSAR studies

Pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening were performed using the SBP module in Discovery Studio (DS2024). Pharmacophore models were built from the EC-7f and BuChE complex, capturing key chemical features and spatial arrangements for binding. Virtual screening was conducted across six chemical databases (ChEMBL, PubChem, DruglikeDiverse, MinMaybridge, Sample, and sc-PDB), selecting compounds with a fit value > 3 for further analysis. Top compounds were evaluated for binding affinity and interactions using molecular docking in DS. For QSAR modeling of BuChE inhibition, a dataset of 32 synthesized compounds was divided into training and test sets (6:4 ratio). A SVM regression model was built using the Scikit-Learn toolkit, with 128-bit Morgan fingerprints as input features and negative logarithmic IC50 values (pIC50) as the target. Model performance was assessed with cross-validated R2 and mean squared error (MSE).

4.3. Molecular docking

Molecular docking was performed using the CDOCKER tool in Discovery Studio (DS) 2024, employing grid-based docking and the CHARMM force field. Ligand conformations were generated via high-temperature molecular dynamics and random rotations, followed by grid-based simulated annealing for optimization. The human BuChE protein structure (PDB ID: 4TPK) was prepared with DS's “Prepare Protein” tool. The binding site was defined as a 10 Å sphere around the original ligand in the enzyme's active site. After docking, the top 10 ligand–receptor conformations were selected and analyzed using PyMOL to visualize binding interactions.

4.4. Molecular dynamics simulation and binding free energy calculation

MD simulations were conducted using GROMACS (2022.5) to study the protein-ligand complex dynamics. The system was solvated in a 10 Å buffer cubic box with TIP3P water and counterions to neutralize the charge. Energy minimization was performed for 5000 steps, followed by equilibration: 100 ps NVT at 310 K, then 100 ps NPT at 1 atm. Production was carried out over 50 ns at 310 K and 1 atm, recording trajectories every 2 fs. The binding free energy of the protein–ligand complex was calculated using the G_MMPBSA tool, following the MD simulation. Frames from the last 20 ns of the MD trajectory were extracted for this analysis. The MM-PBSA (Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area) method was employed to compute the binding free energy by considering van der Waals, electrostatic, polar solvation, and nonpolar solvation contributions.

4.5. Inhibition experiments of AChE and BuChE

AChE, derived from electric eel (eeAChE) and human erythrocytes (huAChE), and butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) obtained from equine serum (eqBuChE) and human serum (huBuChE), were used in this study. The reagents used included 5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (Ellman's reagent, DTNB), acetylthiocholine chloride (ATC), and butyrylthiocholine chloride (BTC), all purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. The inhibition assays for AChE and BuChE were conducted spectrophotometrically, following a modified version of Ellman's protocol. The final assay mixture comprised 100 μL of DTNB (0.5 mmol/L), 50 μL of either hAChE (0.75 U/mL) or hBuChE (0.75 U/mL), and the corresponding substrates: 20 μL of ATC (3.75 mmol/L) for AChE or 20 μL of BTC (3.75 mmol/L) for BuChE. Absorbance changes at 405 nm were recorded every 30 s over a period of 3 min using a microplate reader (ThermoFisher).

4.6. Study on the reversibility of BuChE inhibition

The recovery of BuChE activity in the presence of rivastigmine, donepezil, and compound 8e, each diluted to 0.1 IC50, was monitored over time at room temperature. For specific detection methods. According to the Ellman assay, 10 μL of compound 8e, donepezil and rivastigmine (at the concentration corresponding to 50% inhibition of BuChE) was added to 90 μL of PBS buffer. The absorbance at 405 nm (OD value) was measured using a microplate reader at the following time points: 0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, 90 and 120 min. Each compound at each concentration was assessed in triplicate. The BuChE inhibition rate (%) was calculated according to Eq. (1):

| Inhibition rate (%) = [1–(ODsample–ODblank)/(ODcontrol–ODblank)] × 100% | (1) |

Other biological activity experiments could be found in the Supporting Information.

4.7. The effects of 8e on zebrafish models

Adult zebrafish were maintained under controlled conditions with a 14-h light/10-h dark cycle, optimal temperature, pH, and conductivity. Before experiments, healthy male and female zebrafish were selected for breeding, and fertilized embryos were collected, cleaned, and cultured. At 4 h post-fertilization, embryos were exposed to different concentrations of compound 8e to determine its safety, with observations and measurements, including body length and fluorescence, conducted over time. To model AD, embryos were treated with AlCl3 at 72 hpf, and experimental groups, including controls, 8e, and donepezil treatments, were established. Behavioral recovery in AD zebrafish was assessed through swimming tests under alternating light and dark conditions. BuChE overexpression and knockdown were achieved using mRNA and morpholino injections, and movement behavior was evaluated at multiple stages. Histological analysis involved HE staining of larvae, and ACh content and BuChE activity were measured using a microplate assay. RNA was extracted, reverse-transcribed, and quantified via RT-PCR to analyze gene expression changes, with results indicating the effects of 8e on AD zebrafish models. More experimental details are provided in the Supporting Information.

4.8. The effects of 8e on APP/PS1 mice

The study explored the effects of 8e on APP/PS1 mice. Materials included donepezil hydrochloride tablets, corn oil, and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose. Ten C57 mice served as the negative control group, while fifty APP/PS1 mice were divided into model, low-dose, medium-dose, high-dose, and positive control groups. The model group received solvent, and the treatment groups received 8e at 0.87, 2.6, or 7.8 mg/kg, or donepezil at 2 mg/kg, administered orally for nine weeks. In the ninth week, cognitive performance was assessed using the Morris water maze, where escape latency and platform retention were recorded. Afterward, blood, brain, and liver tissues were collected. Plasma lipid profiles were measured, and brain tissues underwent histological and biochemical analysis. HE staining showed pathological changes, immunofluorescence visualized proteins, and ELISA quantified ACh, Aβ1–42, and inflammatory markers. These findings highlighted the potential neuroprotective effects of 8e in AD disease models. All experimental procedures were executed according to the protocols approved by Sichuan Academy of Chinese Medicine Sciences Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee (Resolution No.: SYLL (2022-040). More experimental details are provided in the Supporting Information.

Author contributions

Zhipei Sang, Shuheng Huang, Wanying Tan and Yujuan Ban contributed equally to this work, they conducted the experiments and performed data analysis. Keren Wang, Yufan Fan, Hongsong Chen, Qiyao Zhang, Chanchan Liang, Jing Mi, Yunqi Gao, Ya Zhang, Wenmin Liu and Jianta Wang performed the chemical and biological tests. Haibin Luo provided guidance on the structure of the article. Zhipei Sang, Wu Dong, Zhenghuai Tan and Lei Tang supervised the entire research with conceptualization, analysis and resources. Zhipei Sang and Shuheng Huang were responsible for writing the manuscript and responding to comments. All of the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022M712153); The National Natural Science Foundation of China (22367007, 82304384); The Fundamental Research Funds for Hainan University (KYQD(ZR)23002, China); Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (824RC500); National-Local Joint Engineering Research Center for Innovative & Generic Chemical Drug, and Guizhou High-level Innovative Talents Supporting Program (2016–4015, China); The State Key Laboratory of Functions and Applications of Medicinal Plants, Guizhou Medical University (Grant number FAMP202107K, China); Guizhou Science and Technology Platform Talents (QKHRCPT[2019]5627, China); Program for Innovative Research Team in Universities of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (NMGIRT2216, China); Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China (2020MS08103).

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting information to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2025.02.030.

Contributor Information

Wu Dong, Email: dongwu@imun.edu.cn.

Zhenghuai Tan, Email: tanzhh616@163.com.

Lei Tang, Email: tlei1974@163.com.

Appendix A. Supporting information

The following is the Supporting Information to this article.

References

- 1.Hodson R. Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2018;559:S1. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-05717-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer’s Disease International Dementia facts and figures. https://www.alzint.org/about/dementia-facts-figures/ Available from:

- 3.Long S., Benoist C., Weidner W. Alzheimer’s Disease International; London, England: 2023. World Alzheimer Report 2023: reducing dementia risk: never too early, never too late. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jia J.P., Ning Y.Y., Chen M.L., Wang S.H., Yang H., Li F.Y., et al. Biomarker changes during 20 years preceding Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:712–722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2310168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasb M., Tao W., Chen N. Alzheimer's disease puzzle: delving into pathogenesis hypotheses. Aging Dis. 2024;15:43–73. doi: 10.14336/AD.2023.0608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cummings J., Zhou Y., Lee G., Zhong K., Fonseca J., Cheng F. Alzheimer's disease drug development pipeline: 2024. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2024;10 doi: 10.1002/trc2.12385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haake A., Nguyen K., Friedman L., Chakkamparambil B., Grossberg G.T. An update on the utility and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2020;19:147–157. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2020.1721456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Couzin-Frankel J. Side effects loom over Alzheimer's drugs. Science. 2023;381:466–467. doi: 10.1126/science.adk0830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu W.X., Ji Y., Wang Z.L., Wu X.X., Li J.X., Gu F., et al. The FDA-approved anti-amyloid-β monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Med Res. 2023;28:544. doi: 10.1186/s40001-023-01512-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turgutalp B., Kizil C. Multi-target drugs for Alzheimer's disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2024;45:628–638. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2024.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sang Z.P., Wang K.R., Dong J.H., Tang L. Alzheimer's disease: updated multi-target therapeutics are in clinical and in progress. Eur J Med Chem. 2022;238 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giacobini E., Cuello A.C., Fisher A. Reimagining cholinergic therapy for Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2022;145:2250–2275. doi: 10.1093/brain/awac096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xing S.S., Li Q., Xiong B.C., Chen Y., Feng F., Liu W.Y., et al. Structure and therapeutic uses of butyrylcholinesterase: application in detoxification, Alzheimer's disease, and fat metabolism. Med Res Rev. 2021;41:858–901. doi: 10.1002/med.21745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darvesh S., Hopkins D.A., Geula C. Neurobiology of butyrylcholinesterase. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:131–138. doi: 10.1038/nrn1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Girard E., Bernard V., Minic J., Chatonnet A., Krejci E., Molgó J. Butyrylcholinesterase and the control of synaptic responses in acetylcholinesterase knockout mice. Life Sci. 2007;80:2380–2385. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li B., Stribley J.A., Ticu A., Xie W., Schopfer L.M., Hammond P., et al. Abundant tissue butyrylcholinesterase and its possible function in the acetylcholinesterase knockout mouse. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1320–1331. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.751320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duysen E.G., Li B., Lockridge O. The butyrylcholinesterase knockout mouse: a research tool in the study of drug sensitivity, bio-distribution, obesity and Alzheimer's disease. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2009;5:523–528. doi: 10.1517/17425250902915555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brimijoin S., Chen V.P., Pang Y.P., Geng L., Gao Y. Physiological roles for butyrylcholinesterase: a BChE–ghrelin axis. Chem Biol Interact. 2016;259:271–275. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manoharan I., Boopathy R., Darvesh S., Lockridge O. A medical health report on individuals with silent butyrylcholinesterase in the Vysya community of India. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;378:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reid G.A., Darvesh S. Butyrylcholinesterase-knockout reduces brain deposition of fibrillar beta-amyloid in an Alzheimer mouse model. Neuroscience. 2015;98:424–435. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maurice T., Strehaiano M., Siméon N., Bertrand C., Chatonnet A. Learning performances and vulnerability to amyloid toxicity in the butyrylcholinesterase knockout mouse. Behav Brain Res. 2016;296:351–360. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sang ZP, Pan WL, Wang KR, Ma QG, Yu LT, Yang Y, et al. Design, synthesis and evaluation of novel ferulic acid-O-alkylamine derivatives as potential multifunctional agents for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;130:379–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin X, Liu XF, Wu X, Liu XY, Tian QQ, Luo QQ, et al. Design, synthesis, and 3D-QASR of 2-Ar-1,2,3-triazole derivatives containing hydrazide as potential fungicides. J Agric Food Chem. 2024;72:12415–12424. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c08951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zou LW, Li YG, Wang P, Zhou K, Hou J, Jin Q, et al. Design, synthesis, and structure–activity relationship study of glycyrrhetinic acid derivatives as potent and selective inhibitors against human carboxylesterase 2. Eur J Med Chem. 2016;112:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sang ZP, Wang KR, Shi J, Cheng XF, Zhu GF, Wei RR, et al. Apigenin–rivastigmine hybrids as multi-target-directed ligands for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;187:111958. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soares C., Da Ros L.U., Machado L.S., Rocha A., Lazzarotto G., Carello-Collar G., et al. The glutamatergic system in Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2024;29:2261–2273. doi: 10.1038/s41380-024-02473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen L.Z., Ou S.S., Zhou L.Q., Tang H., Xu J., Guo K.H. Formononetin attenuates Aβ25–35-induced cytotoxicity in HT22 cells via PI3K/Akt signaling and non-amyloidogenic cleavage of APP. Neurosci Lett. 2017;639:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cui X., Cao D.Y., Qu C.H., Zhang X.Y., Zheng A.P. A study of the chemical and biological stability of vasoactive intestinal peptide. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2013;39:1907–1910. doi: 10.3109/03639045.2012.693503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin X., Wang S., Zhao L.M., Huang W.J., Zhang Y.X., Pannecouque C., et al. Development of fluorine-substituted NH2-biphenyl-diarylpyrimidines as highly potent non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors: boosting the safety and metabolic stability. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13:1192–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]