Abstract

Background

Several clinical trials support the efficacy of Whole Systems Traditional Chinese Medicine (WS-TCM) modalities, including acupuncture, for improving outcomes among women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF), but few studies have described its real-world integration within an academic medical setting or its immediate effects on pain, stress, and anxiety.

Objective

To characterize the clinical delivery of WS-TCM and assess its effects on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) among patients receiving WS-TCM while undergoing IVF.

Methods

A retrospective review of patients who received ≥1 WS-TCM treatment associated with ≥1 embryo transfer at a single center was conducted. A linear mixed model adjusting for the random effect of patients seen over multiple treatments was used to calculate PRO changes among those with pre-treatment PROs ≥1 on a 0-10 numeric rating scale.

Results

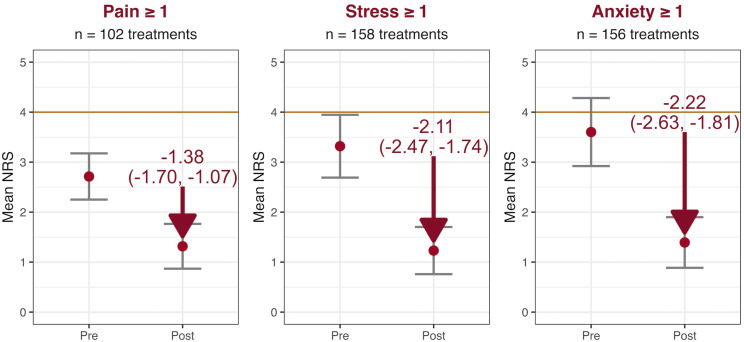

1896 WS-TCM treatments were provided during 202 embryo transfers among 146 patients. Patients (mean age 35.76 ± 4.37) were predominantly white (79.5%), and 26.7% had a documented mental health diagnosis. Of the 202 embryo transfers, 64.9% included pre-transfer treatment, 88.6% included day-of-transfer treatment, and 32.2% included post-transfer treatment. Patients reporting pre-treatment PROs ≥1 reported clinically significant mean [95% CI] reductions in pain (−1.38 [−1.70, −1.07]), stress (−2.11 [−2.47, −1.74]), and anxiety (−2.22 [−2.63, −1.81]) within a single treatment.

Conclusions

This study supports the integration of WS-TCM within IVF and its benefits for reducing acute pain, stress, and anxiety. WS-TCM may improve patient experiences and be a useful treatment for psychosocial concerns that often accompany IVF.

Keywords: traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture, pregnancy

Introduction

Infertility, defined as the inability to become pregnant after one year of regular, unprotected intercourse, affects one in five nulliparous people in the United States (US). 1 Treatment includes artificial reproductive technology (ART), of which the most common is in vitro fertilization (IVF). 2 Despite rapid growth in ART utilization, only 37% of ART cycles conclude with a healthy, live birth.3-5 Cost constitutes a significant barrier to IVF care in the US, with estimates ranging from $12,000 to over $25,000 per IVF cycle.6,7 As a result, IVF presents multiple psychosocial stressors. 8 In a cross-sectional study among 893 women who had completed one IVF cycle but did not return for treatment, nearly 40% reported discontinuing due to treatment-related stressors. 9 In addition, patients often have comorbid symptoms of psychological distress, including depression and anxiety. 10 There is an established link between stress and infertility, and reducing psychological stress is associated with improved pregnancy outcomes. 11 Thus, innovative strategies are needed to address the emotional and allostatic burdens of infertility care.

Integrative health and medicine (IHM) modalities are often pursued within this population. 12 Provided in conjunction with conventional medical treatments, IHM modalities can promote a whole health approach to care delivery to address psychosocial concerns in addition to physical conditions. 13 One such strategy that has demonstrated benefits for women undergoing IVF is Whole Systems Traditional Chinese Medicine (WS-TCM). 14 WS-TCM uses therapeutic modalities including a combination of acupuncture, lifestyle and dietary modifications, and herbal medicines. Within infertility care, IHM has been increasingly used in conjunction with conventional Western fertility treatment, with a 2023 cross-sectional study of 1460 patients reporting that 80.4% had used at least one IHM therapy, such as acupuncture.12,15 In particular, people with infertility often seek out WS-TCM approaches to improve IVF outcomes and address IVF-related stressors, with an estimated 38.5% doing so in 2019. 16

One of the most studied and reported WS-TCM modalities is acupuncture. There is prior literature to support acupuncture’s effectiveness for improving fertility outcomes among those undergoing IVF; however, the data is not completely consistent. 17 In a meta-analysis of 25 trials, women undergoing IVF had higher rates (relative risk [RR] 95% confidence interval [CI]) of clinical pregnancy (RR 1.33 [1.23, 1.43]) and live births (RR 1.33 [1.19, 1.49]) as compared to control (ie, no intervention or sham acupuncture). 18 However, as acupuncture has been utilized and studied over the years, delivery and dose utilized within IVF has varied. A 2006 randomized controlled trial (RCT) (n = 228) found no significant difference in pregnancy rate when using acupuncture pre-embryo transfer and post-embryo transfer compared to sham acupuncture. 19 A 2022 non-randomized study (n = 99) found no statistical difference in pregnancy rate when comparing weekly acupuncture before transfer to acupuncture on day of transfer. 20 A more recent 2023 retrospective study concluded WS-TCM improves live birth rates of patients undergoing IVF with a 60.5% live birth rate vs 52.7% (P = 0.045). 21 A systematic review of 10 RCTs hypothesized that effect inconsistencies may be due to the lack of consistent treatment administration and performance by licensed acupuncturists, limiting the generalization of results to clinical practice. 22 This is further demonstrated in two 2024 systematic reviews that found differing doses and timing of acupuncture often yielded differing outcomes for live birth rate (RR 1.75, P = 0.03) and clinical pregnancy rate (RR = 1.71, P < 0.01).23,24 In addition, diverse applications of acupuncture, including electro-acupuncture and acupuncture integrated as part of WS-TCM delivery, have more recently evolved as modern medicine integrates with traditional modalities. 25 Thus, it is necessary to characterize present-day, real-world clinical practice of acupuncture within the context of both WS-TCM and modern infertility care.

When considering the psychosocial burdens of infertility care, a 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 RCTs found adjuvant acupuncture during infertility treatment led to improvements in anxiety and depression as measured by the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (SMD −1.02 [−1.52, −0.52]) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SMD −4.31 [−7.52, −1.11]). 26 In a 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis of eight studies, adjuvant acupuncture administered during IVF led to small but significant improvements in anxiety (SMD −0.21 [−0.39, −0.04]) with no meaningful differences in stress and quality of life. Anxiety symptoms in these studies were primarily assessed longitudinally after embryo transfer, while stress was assessed after embryo transfer or egg retrieval. 27 With regards to short-term pain management, results from a 2021 meta-analysis support the effectiveness of acupuncture as an adjuvant analgesic to reduce postoperative pain following oocyte retrieval as compared to conscious sedation (SMD −1.11 [−1.51, −0.71]) or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs alone (SMD −1.76 [−2.08, −1.44]). 28 Though prior studies provide encouraging preliminary data for its benefit upon post-embryo transfer anxiety,29-31 stress,32,33 and wellbeing, 34 few studies have examined the immediate and acute impact of adjuvant WS-TCM upon emotional symptoms.

To address these gaps, the purpose of this study was to characterize the clinical delivery of WS-TCM and assess its immediate effects on pain, anxiety, and stress among patients undergoing IVF within a large academic medical center.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Design

This study is a retrospective review of all individualized WS-TCM treatments provided at University Hospitals (UH) Connor Whole Health to female patients aged 18 to 50 years who received ≥1 WS-TCM treatment associated with ≥1 embryo transfer at the UH Fertility Center between January 03, 2019 and December 22, 2022.

Setting and Care Delivery

The UH Fertility Center is a multidisciplinary center that involves collaboration between board-certified reproductive endocrinology and infertility physicians, an IVF High Complexity Laboratory Director (HCLD), andrologists and embryologists, nurse practitioners, nurses, and administrators. The UH Fertility Center care model involves close collaboration between the medical IVF providers and the integrative WS-TCM providers at UH Connor Whole Health, allowing the two treatments to be integrated and coordinated.

UH Connor Whole Health, a center for IHM embedded within the UH Health System, offers modalities including acupuncture, massage therapy, chiropractic medicine, naturopathic medicine, expressive therapies, yoga therapy, and lifestyle medicine consultations. The WS-TCM providers at UH Connor Whole Health provide WS-TCM treatments including acupuncture to patients undergoing ART at the UH Fertility Center in outpatient facilities during the weeks and months leading up to transfer and following transfer, as well as on-site acupuncture in the UH Fertility Center procedure area on the day of embryo transfer, when requested.

Care offered includes a regimen of four to six WS-TCM treatments delivered once weekly to prepare for embryo transfer and acupuncture on the day of transfer, with either one treatment before transfer in the outpatient office or one treatment before and one treatment after transfer on-site depending on patient preference. Patients have the option to follow up with weekly treatment after embryo transfer throughout the first trimester of pregnancy. Appointments are scheduled for 90 minutes for the initial visit and 60 minutes for follow up visits with a total needle retention time of 25-30 minutes. Reimbursement involves a mix of self-pay and commercial insurance. All practitioners are board certified by the National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (NCCAOM) and hold an Acupuncture License from the State Medical Board. The lead fertility practitioner has additional board certification from The Acupuncture and TCM Board of Reproductive Medicine (ABORM). Patients receive acupuncture, counseling and guidance with herbs, supplements, and lifestyle medicine as part of WS-TCM delivery. Acupuncture and electro-acupuncture are both provided by a licensed and experienced WS-TCM practitioner.

Ethics and Permissions

This study was approved by the UH Cleveland Medical Center Institutional Review Board as a retrospective chart review (STUDY20221610) of a data repository (STUDY20221381) of WS-TCM treatments. Given that this study analyzed retrospective electronic health record (EHR) data, a waiver of informed consent was granted.

Record Identification

Electronic Medical Record Search Engine (EMERSE) 35 was used to identify all female patients meeting eligibility criteria. The EMERSE implementation at UH covers over 1.7 million patients and over 46 million searchable clinical notes (2018 to present) which are updated via nightly feeds from the EHR. A specific search query was developed to identify the presence of “fertility” within EHR documentation among all WS-TCM practitioners working with patients from the UH Fertility Center during the study period. EMERSE generated a list of patients that was then cross-verified with a registry database maintained by the UH Fertility Center.

Data Collected

We extracted the following data from all records meeting eligibility criteria: (1) demographic information including age, sex, race, and ethnicity; (2) clinical characteristics including ICD-10 codes for all relevant diagnoses, chief complaints, and pain locations listed in providers’ notes; and (3) treatment documentation data including treatment dates, specific techniques utilized (eg, body points, auricular points, cupping), and numeric rating scale [NRS] measures of pain, stress, and anxiety. NRS measures were collected on paper as part of a project conducted at UH Connor Whole Health from January 2019 through July 2020. 36 Thus, NRS measures were only available for a subset of treatments. Pain, stress, and anxiety were selected as PROs as they are common among women undergoing infertility treatment. 9 Pain was a frequently reported concern among women presenting to WS-TCM and is often associated with co-occurring conditions such as endometriosis. 37

All EHR data, including full note documentation, were extracted via a single structured query language script from the UH Electronic Data Warehouse. Regular expressions functions including str_extract_all from the stringr package 38 and regmatches, gregexpr, sub, and gsub from base R version 4.4.1 were used to extract clinical information from the free-text note. We extracted fertility-related diagnoses, transfer dates, and transfer type (ie, Fresh or Frozen) for each embryo transfer from the registry database maintained by the UH Fertility Center.

Data Analysis

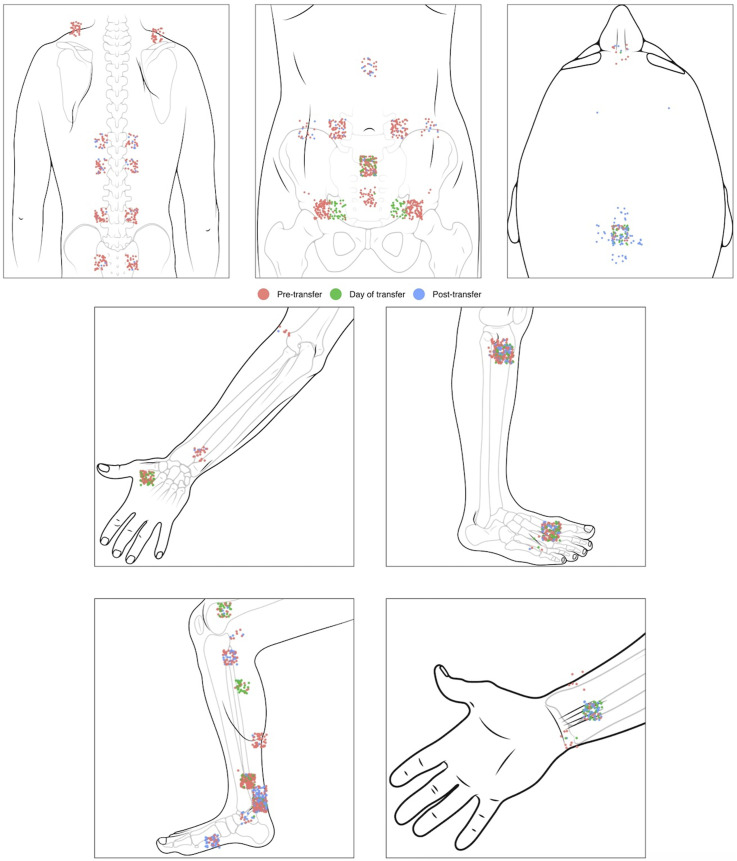

Descriptive statistics were calculated for patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and treatment characteristics. WS-TCM treatments were classified into three categories based on distance from day of transfer: (1) pre-transfer (between 120 days before day of transfer to the day before transfer; (2) day of transfer; and (3) post-transfer (between the day after transfer to 70 days post-transfer). 39 To summarize the distribution of acupuncture body points used within treatments, the authors collaborated with a medical illustrator who drafted images of the body regions where acupuncture body points were used. Appropriate coordinates were applied to a random sample of 30% of the acupuncture points to improve legibility and plotted on these images using tools from the ggplot2 package. 40 Points were color-coded based on when in IVF treatment they were utilized (ie, pre-, post-, or day of transfer).

Means and 95% CI were used to examine WS-TCM’s clinical effectiveness on pain, stress, and anxiety rated ≥1 on the NRS (ie, at least mild symptoms). Given that some patients rating their symptoms ≥1 on the NRS were seen over multiple treatments, we used the “lmer” function within the “lme4” package 41 in R to fit a linear mixed model examining changes in PROs after adjusting for the random effect of patients appearing more than once in the data. We extracted data from clinical narratives, analyzed descriptive statistics, fit models, and generated tables and plots using R Version 4.4.1 42 and RStudio Version 2024.04.21 + 764. 43

Results

Sample Demographics

Between January 03, 2019 and December 22, 2022, WS-TCM practitioners provided 1896 treatments to 146 patients who underwent a total of 202 embryo transfers. Of these 202, 167 (82.7%) were frozen embryo transfers and 35 (17.3%) were fresh embryo transfers. Among the 146 patients, 104 (71.2%) underwent just one embryo transfer with WS-TCM, while 42 (28.8%) underwent more than one (max 4 transfers). Table 1 presents demographic characteristics. Patients predominantly identified as white (79.5%), followed by Black/African American (6.2%), and Non-Hispanic (82.9%). Most patients were ≤38 years (67.1%), with an overall mean ± standard deviation (SD) age of 35.76 ± 4.37.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics.

| Variable | N = 146 |

|---|---|

| Patient age (years), mean±SD | 35.76 ± 4.37 |

| Patient age (years), range | 27 - 48 |

| Patient age ≤38 years | |

| ≤38 years | 98 (67.1%) |

| >38 years | 48 (32.9%) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 146 (100.0%) |

| Race, n (%) a | |

| White | 116 (79.5%) |

| Black/African American | 9 (6.2%) |

| Other race | 9 (6.2%) |

| Declined/missing/unknown | 12 (8.2%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) a | |

| Non-hispanic | 121 (82.9%) |

| Declined/missing/unknown | 20 (13.7%) |

| Hispanic or latino | 5 (3.4%) |

aRace and ethnicity are reported exactly as they were entered into the EHR and may not reflect patients’ racial or ethnic identities.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation.

Clinical Characteristics

Across 202 transfers, infertility-related diagnoses included: male infertility (22.3%), idiopathic infertility (20.8%), diminished ovarian reserve (17.3%), and polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) (10.9%). Among 146 patients within the study sample, 39 (26.7%) had a mental health diagnosis within their medical record. Common mental health diagnoses included anxiety disorder (20.5%), reaction to severe stress or adjustment disorder (8.2%), and depressive disorder (6.8%). More than a quarter (28.1%) of patients reported pain at some point during treatment, with common pain sites across treatments including the lower back (8.9%), neck (8.1%), upper back (5.5%), and knee (3.4%).

Treatment Characteristics

Table 2 summarizes WS-TCM characteristics across the 202 embryo transfers. A median (interquartile range [IQR]) of 4 (2-9) treatments were provided per transfer with a range of 1-42 treatments. Of all transfers, 131 (64.9%) included pre-transfer treatment, and 65 (32.2%) included post-transfer treatment. Among the 131 that featured pre-transfer treatment, patients received a median of 4 (2-8) treatments with a median (IQR) start date of 69 (19-112) days prior to transfer. Most embryo transfers (88.6%) included day-of-transfer treatment.

Table 2.

Transfer Treatment Characteristics.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| All transfers | N = 202 |

| Total treatments, median (IQR) | 4 (2, 9) |

| Total treatments, range | 1 - 42 |

| Received pre-transfer treatment, n (%) | 131 (64.9%) |

| Total pre-transfer treatments, median (IQR) | 2 (0, 6) |

| Total pre-transfer treatments, range | 0 - 25 |

| Days prior to transfer when treatment started, median (IQR) | 19 (0, 91) |

| Received day-of-transfer treatment, n (%) | 179 (88.6%) |

| Total day-of-transfer treatments, median (IQR) | 2 (1, 2) |

| Total day-of-transfer treatments, range | 0 - 2 |

| Received post-transfer treatment, n (%) | 65 (32.2%) |

| Total post-transfer treatments, median (IQR) | 0 (0, 1) |

| Total post-transfer treatments, range | 0 - 15 |

| Transfers with pre- transfer treatments | N = 131 |

| Total treatments, median (IQR) | 7 (4, 11) |

| Total treatments, range | 1 - 42 |

| Received pre-transfer treatment, n (%) | 131 (100.0%) |

| Total pre-transfer treatments, median (IQR) | 4 (2, 8) |

| Total pre-transfer treatments, range | 1 - 25 |

| Days prior to transfer when treatment started, median (IQR) | 69 (19, 112) |

| Received day-of-transfer treatment, n (%) | 108 (82.4%) |

| Total day-of-transfer treatments, median (IQR) | 2 (1, 2) |

| Total day-of-transfer treatments, range | 0 - 2 |

| Received post-transfer treatment, n (%) | 62 (47.3%) |

| Total post-transfer treatments, median (IQR) | 0 (0, 3) |

| Total post-transfer treatments, range | 0 - 15 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range.

Supplemental Table 1 lists common body points used across all 1896 acupuncture treatments, while Figure 1 provides a graphical depiction of these points. Across all treatments, common points included KD3 (80.0%), ST36 (69.1%), LIV3 (67.3%), SP6 (65.3%), and R6 (62.5%). WS-TCM practitioners used a mean of 19.24 ± 4.01 needles. Other WS-TCM techniques provided alongside acupuncture included administering stainless steel ear seeds (89.0%), a Teding Diancibo Pu (TDP) lamp (83.0%), auricular points (54.0%), electro-acupuncture (30.0%), and cupping (4.6%).

Figure 1.

Acupuncture body points. Dots represent the distribution of the most prevalent acupuncture points provided across 1896 acupuncture treatments. Points were plotted after taking a random sample of 30% of these points to improve legibility.

Effects on Patient-Reported Outcomes

Supplemental Table 2 summarizes means and 95% CI among patients reporting scores ≥1 on the NRS, while Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of single-treatment changes. These patients reported mild (ie, <4/10) 44 overall mean pre-treatment scores for pain intensity (2.71), stress (3.32), and anxiety (3.60) as well as clinically significant mean [95% CI] single-treatment reductions in pain intensity (−1.38 [−1.70, −1.07]), stress (−2.11 [−2.47, −1.74]), and anxiety (−2.22 [−2.63, −1.81]).

Figure 2.

Effects on patient-reported outcomes. Red dots represent means, while error bars represent 95% confidence intervals after adjusting for the random effect of patient. The downward arrow represents the magnitude of the immediate change in PRO scores from pre-to post-encounter. The orange line at 4 represents the threshold for at least moderate symptoms rated 4/10 on the numeric rating scale. Abbreviations: NRS, numeric rating scale.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to characterize the clinical delivery of WS-TCM and assess its single-treatment effects on pain, anxiety, and stress among patients undergoing IVF within a large academic medical center. In doing so, our work represents some of the first efforts to assess the immediate impact of such therapies upon patient-reported psychosocial symptomatology, in a population for whom improved mental health may ultimately impact IVF outcomes. 45 Thus, these efforts represent a novel, whole health approach to addressing quality of life outcomes during infertility care.

Of 146 patients, 39 (26.7%) had a documented mental health diagnosis. The most frequent diagnosis was “anxiety disorder” at 30 participants (20.5%). Following anxiety disorder, “reaction to severe stress or adjustment disorder” (12, 8.2%) and “depressive disorder” (10, 6.8%) were frequent. This is consistent with the well-established psychological stressors associated with infertility and prior research suggesting that women seeking infertility treatment are more likely than the general population to report symptoms of depression and anxiety.8,9 Our data were limited in that they did not indicate whether mental health diagnoses preceded IVF treatment. However, they are consistent with literature estimating the prevalence of psychiatric symptomatology among individuals with infertility to be 25–50% with approximately 35% having an anxiety or depression diagnosis.11,46 One 2024 cross-sectional study points out that women undergoing fertility treatment have health needs beyond their infertility: they require mental health support, often addressed in an interdisciplinarity approach that includes integrative medicine. 47 Integrating WS-TCM modalities within fertility care may provide a means of addressing the psychosocial stressors that can accompany infertility.

The number of WS-TCM treatments delivered per transfer varied greatly with a median of 4 and a range of 1-42 treatments. Most treatment protocols in prior studies have reported 2 treatments, with a small minority including 3-6 treatments. 27 Given that our patients received WS-TCM within the Fertility Center, some may have increased utilization due to proximity. Other reasons for increased delivery within our sample may include increasingly positive attitudes towards IHM therapies by providers – a systematic review of 26 studies found that 92% of health care providers reported supporting the integration of acupuncture into Western medical care 48 – and patients’ desire to address pain and stress. Some patients may have hoped for more treatments but faced barriers including cost, inability for time off, and other competing responsibilities. Pursuing IVF is an already costly endeavor; adding WS-TCM treatment may not always be feasible. 7

WS-TCM utilizes constitutional diagnosis to support the treatment approach. Patients with the same Western infertility diagnosis may have different TCM diagnoses and therefore different treatments. This constitutional approach creates challenges for studying protocols and standardized care for acupuncture because the protocol may or may not fit the patient’s presentation and diagnosis. Some commonly used acupuncture points are seen frequently in the fertility acupuncture literature, such as LI 4, PC 6, CV 6, ST 29, GV 20, SP 10, ST 36, SP 6, LV 3, KI 3, and auricular Shenmen and Uterus. 49 The Paulus protocol has been a foundational treatment for day of transfer acupuncture. 50 Paulus protocol day of embryo transfer acupuncture points before transfer include: GV 20, CV 6, ST 29, SP 8, PC 6, LV 3; Shenmen and Brain on the left ear; and Uterus and Endocrine on the right ear. Day of embryo transfer acupuncture points after transfer include: LI 4, SP 10, ST 36, SP 6; Uterus and Endocrine on the left ear; and Shenmen and Brain on the right ear. 50 These points are consistent with the points treated during our review with potential point modification based on patient presentation and needs. However, though most treatments in our study included a day-of-transfer treatment (88.6%), patients also received care far in advance of embryo transfer. The concordance across points used in infertility and IVF care may provide the basis for developing standardized acupuncture approaches and WS-TCM protocols within the medical infertility treatment setting.

Pre-treatment pain intensity, stress, and anxiety scores within our sample were in the mild range (eg, <4 on 10-point NRS) at 2.71, 3.32, and 3.60 respectively. Few studies have explored these acute symptoms as measured by 10-point NRS, preferring to use other scales including the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), and Fertility Quality of Life Questionnaire (FertiQOL) that are better suited toward capturing mood and quality of life states over longer time periods. 51 The pre-infertility care scores in these studies presented mean scores reflecting moderate-to-high anxiety per these instruments, of apparently greater severity than this sample. However, differences in measurement instruments limit comparison to prior literature.

Patients within this study reported clinically meaningful single-treatment reductions in pain intensity (−1.38 [−1.70, −1.07]), stress (−2.11 [−2.47, −1.74]), and anxiety (−2.22 [−2.63, −1.81]). Direct comparisons to prior studies are challenging given few studies exploring the short-term impact of acupuncture upon IVF-related psychosocial measures. Nonetheless, our observed mean changes in pain scores are comparable to those reported among patients receiving adjuvant acupuncture with conscious sedation during oocyte retrieval as measured by simple self-rating scales (SMD −1.11 [−1.51, −0.71]) per a 2022 systematic review. 28 Expanding comparison to other conditions, the mean pain reduction observed within this sample was comparatively less (1.38 units) than a prior observational study of post-surgical acupuncture among 1977 adults undergoing hip or knee replacement surgery (1.91 units). 52

Regarding anxiety, our observed mean reductions appear to be consistent with those from previous trials of single-treatment acupuncture, though comparison is limited due to different scales used. In comparison to trials investigating acupuncture in adults with cancer, we observed a smaller effect on pain (1.38 units) but a greater effect on anxiety (2.22 units) than that reported by Miller et al 53 (n = 68, mean pain reduction 1.90 units, mean anxiety reduction 0.90 units) and Thompson et al 54 (n = 87 for pain, mean pain reduction 1.39 units, n = 85 for anxiety, mean anxiety reduction 1.26 units).

In examining effects on patients’ perceived stress, our results are consistent with those of similar trials demonstrating a clinically significant decrease in stress following acupuncture treatment, though direct comparison is limited due to the use of different measurement scales. Balk et al 32 (n = 17) reported a mean decrease in stress of 0.94 ± 3.1 points using the Perceived Stress Scale while Stener-Victorin et al 33 (n = 136) reported a change in median (IQR) scores on the 100-unit VAS from 11 during oocyte aspiration to 1 two hours after oocyte aspiration. Additionally, Balk et al 32 had a limited patient population in comparison to our study, while Stener-Victorin et al 33 used a different treatment modality altogether (assessing electroacupuncture in combination with a paracervical block compared to alfentanil with a paracervical block). Our conclusions are consistent with a 2025 qualitative study that demonstrated integrative therapies were helpful factors to address patient challenges both via acupuncture and the formation of positive provider relationships throughout an often stressful treatment process. 55

Limitations of this study include lack of PRO data collection within the entire sample; the use of observational data among a convenience sample without a control group as PROs were not available for patients receiving IVF treatment who did not receive WS-TCM; the potential for response bias among patients providing post-treatment PROs; and the use of single-item NRS scores rather than more comprehensive instruments for pain, stress, and anxiety. Future observational studies could consider embedding PROs within their fertility centers and using propensity score matching to minimize selection bias in evaluating WS-TCM’s real-world effects on pain, stress, and anxiety. Acupuncture treatments were provided in concert with other WS-TCM modalities that included dietary and lifestyle modifications. Thus, acupuncture’s effects could not be separated from other interventions. Given that real-world WS-TCM practice often includes mixed modalities, this was representative of how patients receive care in the true clinical setting. Furthermore, this study was conducted within a single academic medical center specializing in fertility care, so generalizability of findings to other facilities may be limited. However, the collaborative service model applied within the UH Fertility Center may be representative of tertiary care centers seeking to embrace interdisciplinary patient care. Despite these limitations, strengths of this study include the use of EMERSE to identify eligible patients, collection of PROs immediately before and after treatments within an academic fertility center, and our ability to characterize an abundance of treatment characteristics using EHR documentation.

Conclusions

This retrospective study helps to characterize real-world WS-TCM delivery alongside IVF treatment within a single academic medical center. Our findings suggest that patients receiving WS-TCM while undergoing IVF report clinically significant single-treatment improvements in pain, stress, and anxiety, which is especially important given the high prevalence of psychosocial stressors and mental health conditions within this population. The descriptive analysis may also help inform WS-TCM implementation strategies within other academic medical centers. While future research is needed to further characterize and define WS-TCM’s real-world effectiveness on IVF outcomes such as live birth rate, this study demonstrates that modern WS-TCM may be a useful adjuvant in supporting the clinical experience of infertility treatment.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Clinical Delivery of Whole Systems Traditional Chinese Medicine and Impacts Upon Patient Reported Outcomes During IVF by Rebecca Lu, Samuel N. Rodgers-Melnick, Rebecca Flyckt, Sung Tae Kim, Roshini Srinivasan, Jeffery A. Dusek, and Christine M. Kaiser in Global Advances in Integrative Medicine and Health.

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to Tracy L Segall, MSHS, for study coordination; Regan Stevens for producing the medical illustrations; and biostatisticians from the Cleveland Center for Computational Biology including Mark Beno, MSM, Harry Menegay, PhD, Paola Saroufim, PharmD, MPH, and Sunah Song, PhD. We especially appreciate the support of the Elisabeth Severance Prentiss Foundation, Francoise Adan, MD, and the generous financial support of the Connor Family Foundation (Chris, Sara, and Erin).

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: We appreciate The Connor Foundation for the financial support that helped fund the delivery of reproductive well-being at UH.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Ethical Statement

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the UH Cleveland Medical Center Institutional Review Board as a retrospective chart review (STUDY20221610) of a data repository (STUDY20221381) of WS-TCM treatments.

Informed Consent

Given that this study analyzed retrospective electronic health record (EHR) data, a waiver of informed consent was granted by the UH Cleveland Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

ORCID iDs

Rebecca Lu https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8529-7402

Samuel N. Rodgers-Melnick https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0886-253X

Jeffery A. Dusek https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9581-0564

Data Availability Statement

Data regarding any of the subjects in the study has not been previously published unless specified. Data will be made available to the editors of the journal pre and/or post publication for review or query upon request. The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions as the databases contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. However, the de-identified datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.*

References

- 1.CDC . National ART summary. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/art/reports/2020/summary.html

- 2.Jain MSM. Assisted reproductive technology (ART) techniques. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sunderam S, Kissin DM, Zhang Y, et al. Assisted reproductive technology surveillance - United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2022;71(4):1-19. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7104a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sunderam S, Kissin DM, Zhang Y, et al. Assisted reproductive technology surveillance - United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020;69(9):1-20. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6909a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC . ART success rates. https://www.cdc.gov/art/artdata/index.html

- 6.Zegers-Hochschild F, Schwarze JE, Crosby JA, Musri C, Urbina MT, Latin American Network of Assisted Reproduction REDLARA . Assisted reproductive techniques in Latin America: the Latin American Registry, 2013. Reprod Biomed Online. 2016;32(6):614-625. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2016.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peipert BJ, Montoya MN, Bedrick BS, Seifer DB, Jain T. Impact of in vitro fertilization state mandates for third party insurance coverage in the United States: a review and critical assessment. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2022;20(1):111. doi: 10.1186/s12958-022-00984-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasch LA, Holley SR, Bleil ME, Shehab D, Katz PP, Adler NE. Addressing the needs of fertility treatment patients and their partners: are they informed of and do they receive mental health services? Fertil Steril. 2016;106(1):209-215. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domar AD, Rooney K, Hacker MR, Sakkas D, Dodge LE. Burden of care is the primary reason why insured women terminate in vitro fertilization treatment. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(6):1121-1126. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.02.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nik Hazlina NH, Norhayati MN, Shaiful Bahari I, Nik Muhammad Arif NA. Worldwide prevalence, risk factors and psychological impact of infertility among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12(3):e057132. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rooney KL, Domar AD. The relationship between stress and infertility. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(1):41-47. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2018.20.1/klrooney [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sehgal S, Dyer A, Warren C, Galic I, Jain T. Integrative medicine utilization among infertility patients. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2023;21(1):71. doi: 10.1186/s12958-023-01121-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dyer NL, Surdam J, Srinivasan R, Agarwal A, Dusek JA. The impact of individualized complementary and integrative health interventions provided in clinical settings on quality of life: a systematic review of practice-based research. J Integr Complement Med. 2022;28(8):618-640. doi: 10.1089/jicm.2021.0413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Lacey S, Smith CA, Paterson C. Building resilience: a preliminary exploration of women’s perceptions of the use of acupuncture as an adjunct to In Vitro Fertilisation. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2009;9:50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-9-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie ZY, Peng ZH, Yao B, et al. The effects of acupuncture on pregnancy outcomes of in vitro fertilization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Compl Alternative Med. 2019;19(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2523-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hullender Rubin LE, Opsahl MS, Wiemer KE, Mist SD, Caughey AB. Impact of whole systems traditional Chinese medicine on in-vitro fertilization outcomes. Reprod Biomed Online. 2015;30(6):602-612. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cochrane SSC, Possamai-Inesedy A, Bensoussan A. Acupuncture and women's health: an overview of the role of acupuncture and its clinical management in women's reproductive health. Int J Womens Health. 2014;6:313-325. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S38969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu M, Zhu M, Zheng C. Effects of acupuncture on pregnancy outcomes in women undergoing in vitro fertilization: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;2023:775-788. doi: 10.1007/s00404-023-07142-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith C, Coyle M, Norman RJ. Influence of acupuncture stimulation on pregnancy rates for women undergoing embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(5):1352-1358. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang YR, Wang SZ, Robert K, Zhao JP. [Effect of acupuncture intervention at different time points on the pregnancy rate of frozen embryo transfer]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2022;42(9):987-990. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.20210625-0005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song J-Y, Dong F-Y, Wu Z-J, Ma Y-X, Sun Z-G. Impact of whole-systems traditional Chinese medicine therapy on in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. European Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2023;60:102246. doi: 10.1016/j.eujim.2023.102246 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Shen X, Hu YF, Sodders R. The limitation of randomized control trials on the influence of acupuncture and in vitro fertilization: a literature review. Med Acupunct. 2022;34(1):24-33. doi: 10.1089/acu.2021.0019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Xu HM, Wang QL, et al. The timing and dose effect of acupuncture on pregnancy outcomes for infertile women undergoing in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Integr Complement Med. 2024;30(11):1031-1046. doi: 10.1089/jicm.2023.0478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li YT, Li CL, Yang H, et al. Correlation between acupuncture dose and pregnancy outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer: a systematic review. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2024;24(1):407. doi: 10.1186/s12906-024-04695-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hao JJ, Mittelman M. Acupuncture: past, present, and future. Glob Adv Health Med. 2014;3(4):6-8. doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2014.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang SI, Yoon YJ, Sung SH, Cho SJ, Park JK. Acupuncture treatment for emotional problems in women with infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(20):2704. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11202704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hullender Rubin LE, Smith CA, Schnyer RN, Tahir P, Pasch LA. Effect of acupuncture on IVF-related anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2022;45(1):69-80. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2022.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu LY, Tian ZL, Zhu FT, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of acupuncture for pain management in women undergoing transvaginal oocyte retrieval. J Pain Res. 2021;14:2833-2849. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S319923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guven PG, Cayir Y, Borekci B. Effectiveness of acupuncture on pregnancy success rates for women undergoing in vitro fertilization: a randomized controlled trial. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;59(2):282-286. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2020.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.So EW, Ng EH, Wong YY, Lau EY, Yeung WS, Ho PC. A randomized double blind comparison of real and placebo acupuncture in IVF treatment. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(2):341-348. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Domar AD, Meshay I, Kelliher J, Alper M, Powers RD. The impact of acupuncture on in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(3):723-726. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balk J, Catov J, Horn B, Gecsi K, Wakim A. The relationship between perceived stress, acupuncture, and pregnancy rates among IVF patients: a pilot study. Compl Ther Clin Pract. 2010;16(3):154-157. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2009.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stener-Victorin E, Waldenstrom U, Wikland M, Nilsson L, Hagglund L, Lundeberg T. Electro-acupuncture as a peroperative analgesic method and its effects on implantation rate and neuropeptide Y concentrations in follicular fluid. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(7):1454-1460. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gejervall AL, Stener-Victorin E, Moller A, Janson PO, Werner C, Bergh C. Electro-acupuncture versus conventional analgesia: a comparison of pain levels during oocyte aspiration and patients' experiences of well-being after surgery. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(3):728-735. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanauer DA, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Beno MF, et al. Electronic medical record search engine (EMERSE): an information retrieval tool for supporting cancer research. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2020;4:454-463. doi: 10.1200/cci.19.00134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Srinivasan R, Rodgers-Melnick SN, Rivard RL, et al. Implementing paper-based patient-reported outcome collection within outpatient integrative health and medicine. PLoS One. 2024;19(5):e0303985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0303985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buisman E, Grens H, Wang R, et al. Trends in research on pain relief during oocyte retrieval for IVF/ICSI: a systematic, methodological review. Hum Reprod Open. 2022;2022(1):hoac006. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoac006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wickham WH. Stringr: simple, consistent wrappers for common string operations. 2022. htps://cran.r.project.org/web/packages/stringr/index.html.

- 39.Guo J, Li D, Zhang QF. [Acupuncture intervention combined with assisted reproductive technology: its different effects at different time points during the in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer course]. Zhongxiyi Jiehe Xuebao. 2008;6(12):1211-1216. doi: 10.3736/jcim20081201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wickham H, Chang W, Wickham MH. Package ‘ggplot2. Create elegant data visualisations using the grammar of graphics Version. 2016;2(1):1-189. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Software. 2015;67:1-48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 43.R Studio Team . RStudio: Integrated Development for R. Boston, MA: RStudio, PBC; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paice JA, Cohen FL. Validity of a verbally administered numeric rating scale to measure cancer pain intensity. Cancer Nurs. 1997;20(2):88-93. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199704000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou R, Cao YM, Liu D, Xiao JS. Pregnancy or psychological outcomes of psychotherapy interventions for infertility: a meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:643395. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.643395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Berardis D, Mazza M, Marini S, et al. Psychopathology, emotional aspects and psychological counselling in infertility: a review. Clin Ter. 2014;165(3):163-169. doi: 10.7417/CT.2014.1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maunder A, Arentz S, Armour M, Costello MF, Ee C. Health needs, treatment decisions and experience of traditional complementary and integrative medicine use by women with diminished ovarian reserve: a cross-sectional survey. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2024;64(4):390-398. doi: 10.1111/ajo.13805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang NM, Vesty G, Zheng Z. Healthcare professionals' attitudes to integration of acupuncture in western medicine: a mixed-method systematic review. Pain Manag Nurs. 2021;22(6):684-693. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2021.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ng EH, So WS, Gao J, Wong YY, Ho PC. The role of acupuncture in the management of subfertility. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(1):1-13. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hullender Rubin LE, Opsahl MS, Taylor-Swanson L, Ackerman DL. Acupuncture and in vitro fertilization: a retrospective chart review. J Alternative Compl Med. 2013;19(7):637-643. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aarts JW, van Empel IW, Boivin J, Nelen WL, Kremer JA, Verhaak CM. Relationship between quality of life and distress in infertility: a validation study of the Dutch FertiQoL. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(5):1112-1118. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crespin DJ, Griffin KH, Johnson JR, et al. Acupuncture provides short-term pain relief for patients in a total joint replacement program. Pain Med. 2015;16(6):1195-1203. doi: 10.1111/pme.12685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller KR, Patel JN, Symanowski JT, Edelen CA, Walsh D. Acupuncture for cancer pain and symptom management in a palliative medicine clinic. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(4):326-332. doi: 10.1177/1049909118804464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thompson LM, Osian SR, Jacobsen PB, Johnstone PA. Patient-reported outcomes of acupuncture for symptom control in cancer. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2015;8(3):127-133. doi: 10.1016/j.jams.2015.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li A, Scalise AL, Mayette E, McGeorge N, James K, Mahalingaiah S. Considerations on optimizing the patient experience during assisted reproductive technology treatment: a qualitative analysis. F S Rep. 2025;6(1):25-30. doi: 10.1016/j.xfre.2025.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Clinical Delivery of Whole Systems Traditional Chinese Medicine and Impacts Upon Patient Reported Outcomes During IVF by Rebecca Lu, Samuel N. Rodgers-Melnick, Rebecca Flyckt, Sung Tae Kim, Roshini Srinivasan, Jeffery A. Dusek, and Christine M. Kaiser in Global Advances in Integrative Medicine and Health.

Data Availability Statement

Data regarding any of the subjects in the study has not been previously published unless specified. Data will be made available to the editors of the journal pre and/or post publication for review or query upon request. The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions as the databases contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. However, the de-identified datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.*