Abstract

The intestine is exposed constantly to mechanical stimuli, including blood flow or peristalsis. Recently, gut-on-a-chip models have been developed to recapitulate these physiological stresses. In such models, blood flow and peristalsis are simulated by perfusing culture medium through microchannels and applying cyclic suction to vacuum chambers. With these gut-on-a-chips, the effects of mechanical stimuli on the intestinal structure and function have been elucidated. Additionally, gut-on-a-chip models are used to study intestinal diseases, such as infectious diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, and colorectal cancer. Because they accurately recapitulate the pathophysiology of intestinal diseases, research leveraging their use has revealed mechanisms underlying disease onset and progression in the intestine. In this review, we summarize the development of gut-on-a-chip systems and highlight recent research on intestinal diseases using these models.

Keywords: Gut-on-a-chip, Microphysiological system, Organ-on-a-chip, Intestinal organoid

1. Introduction

The intestine plays important roles in nutrient absorption and host defense against pathogens. It receives an abundant blood supply, which provides nutrients and oxygen to support the intestinal barrier composed of epithelial and immune cells [1]. Intestinal peristalsis is essential for the efficient absorption and excretion of intestinal contents. Despite such dynamics, intestinal homeostasis is maintained. Furthermore, the intestine is directly exposed to foreign antigens entering by the oral route, thus increasing disease risks. Pathogens can breach the intestinal barrier system and trigger inflammation in the intestine, with prolonged inflammation increasing the risk of cancer. Various intestinal models have been developed to recapitulate the functions of healthy intestinal tissues and investigate the pathophysiology of intestinal diseases.

Colorectal adenocarcinoma-derived cell lines and intestinal organoids are widely used to recapitulate intestinal functions. However, replicating mechanical stimuli such as blood flow and peristalsis has been a major challenge. Organ-on-a-chip technology—in vitro models culturing cells on a microfluidic device—was developed to overcome those obstacles. Blood flow and peristalsis in the intestine can be reproduced by perfusing the culture medium through microchannels and stretching the device. Thus, gut-on-a-chip is a valuable tool for investigating the effects of mechanical signals on intestinal functions and to elucidate the mechanism of intestinal disease onset and progression. Here, we will examine the development of gut-on-a-chip systems and summarize the latest research on intestinal diseases using these models.

2. Gut-on-a-chip for mimicking the intestinal characteristics

Intestinal cells are continuously exposed to mechanical stimuli, such as blood flow and peristalsis (Fig. 1A) [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]]. In addition, because the crypt-villus structure is a key feature of the intestinal epithelium, gut-on-a-chip has been developed to recapitulate the mechanical stress and 3D structure of the intestine.

Fig. 1.

Gut-on-a-chip for mimicking mechanical stress and intestinal topography

(A) Intestinal epithelial cells that form the crypt-villus structure are continuously exposed to mechanical stress, such as luminal flow, blood flow, and peristalsis. (B) An example of a two-channel microfluidic device is shown, with the upper and lower channels colored red and green, respectively. (C) OrganoPlate containing 40 microfluidic channel networks is shown (left), with a magnified view of a single microfluidic channel network displayed (right). Reprinted from Ref. [9], which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. (D) The mini-gut that recapitulates the intestinal topography is shown. Reprinted from Ref. [11], which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Two-channel microfluidic devices have been constructed to emulate the fluidic flow and peristalsis in the intestine (Fig. 1B). This device consists of two parallel microchannels separated into upper and lower parts by a porous membrane. Body fluid flow can be recapitulated using a syringe pump to perfuse the culture medium into the microchannels. Additionally, peristaltic motion can be reproduced by applying cyclic suction to vacuum chambers adjacent to the microchannel in the microfluidic device. It has been reported that exposing intestinal cells to mechanical stimulation in two-channel microfluidic device promotes their maturation. The Intestine-Chip was developed by culturing intestinal epithelial cells derived from human pluripotent stem cell (hPSCs) into a two-channel microfluidic device [4]. A polarized ZO-1 expression and a villus-like 3D structure were developed in the Intestine-Chip when cultured under fluidic flow, whereas epithelial cells remained a monolayer in the static condition. Similarly, fluidic flow-induced morphological changes were observed in the Gut-on-a-Chip, which cultured Caco-2 cells, a human colorectal adenocarcinoma-derived cell line, or biopsy-derived intestinal organoids in microfluidic devices [5]. Mechanical forces have additionally been reported to alter the characteristics of intestinal epithelial cells in a gut-on-a-chip. The Small Intestine-on-a-Chip was generated by culturing duodenal organoids generated from biopsied samples in a two-channel microfluidic device [6]. Notably, the gene expression profile of the Small Intestine-on-a-Chip, cultured under fluidic flow and cyclic suction, more closely resembled that of human duodenum than duodenal organoids from which Small Intestine-on-a-Chip was derived. The protein expression profile of intestinal epithelial cells was reportedly altered in the Intestine-Chip—based on jejunal enteroids and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)—by flow and peristalsis-like motion [7]. Moreover, we recently reported that fluidic flow changes the alignment of intestinal fibroblasts on gut-on-a-chip [8]. The micro-small intestine system was developed by simultaneously differentiating hPSCs into intestinal epithelial cells and fibroblasts in the presence of interstitial flow. To reproduce interstitial flow, the movement of body fluid percolating from capillaries, we perfused the culture medium from the lower channel of a two-channel microfluidic device. In the micro-small intestine system, intestinal epithelial cells became polarized, with fibroblasts aligned perpendicularly in response to the interstitial flow. Thus, the 3D structure and characteristics of the in vivo intestine were recapitulated using a gut-on-a-chip to mimic mechanical stimuli such as fluid flow and peristalsis. A high-throughput microfluidic device has also been developed to recreate these mechanical stimuli. OrganoPlate is a 384-well plate format device containing 40 microfluidic channel networks (Fig. 1C) [9]. Each network consists of three channels—top, middle, and bottom—separated by phaseguides. With an extracellular matrix (ECM) gel introduced in the middle channel, cells in the top and bottom channels were separated without an artificial membrane. The gut tube was developed by culturing Caco-2 cells in the OrganoPlate and placed on an interval rocker to simulate flow from body fluid.

Gut-on-a-chip can replicate not only mechanical stress but also the topographical features of the intestine. For example, a mini-gut was developed that simulates the crypt-like structure of the human colon (Fig. 1D) [10]. A biomimetic hydrogel was loaded into the microdevice and laser-ablated to generate a microchannel resembling the intestinal topography. Using the mini-gut, a culture medium containing different growth factors can be applied to both the apical and basolateral sides of cells. Furthermore, Mitrofanova et al. cultured human colon organoids in the mini-colon to reproduce the spatial arrangement of the human colon. In their mini-colon, proliferative and differentiated cells were localized at the bottom and top of crypts, respectively [11]. The tissue polarity of the small intestine was also replicated using a cross-linked collagen scaffold that mimics the crypt-villus structure [12]. Additionally, a 3D gut-chip that recapitulates villi movement was created using a two-channel microfluidic device with carbon nanofibers villi fabricated by photolithography and chemical vapor deposition [13]. The structure and movement of villi were reproduced by culturing Caco-2 cells in the 3D gut-chip and perfusing culture medium at 100 μL/h in the upper channel. Thus, with proper stimulation, intestinal architecture can be recapitulated using a gut-on-a-chip.

Intestinal cells exhibit in vivo-like characteristics when exposed to mechanical stimuli, such as fluid flow and peristalsis, in a gut-on-a-chip. However, the mechanism by which intestinal epithelial cells and fibroblasts sense mechanical stimuli remains unclear. We hope continued research using gut-on-chip systems will help identify mechanosensory molecules or elucidate mechano-transduction mechanisms in the intestine.

3. Gut-on-a-chip for studying intestinal infectious diseases

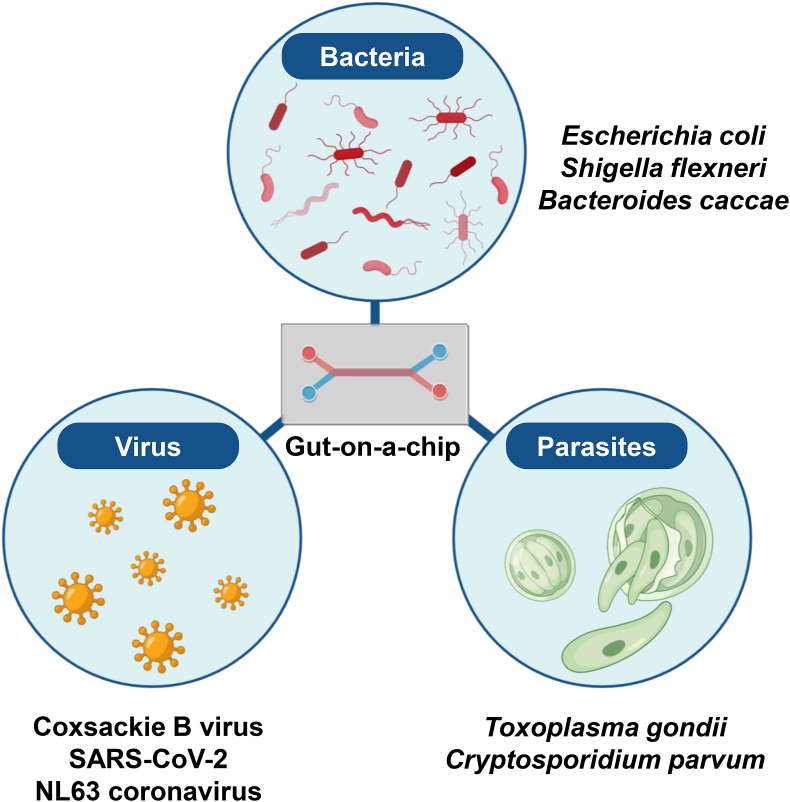

The intestine is frequently exposed to pathogens, such as bacteria, viruses, and parasites, that enter through the mouth, which pose a risk of infectious diseases. A gut-on-a-chip has been used to accurately recapitulate the pathophysiology of transmittable diseases (Fig. 2, Table 1). Additionally, a gut-on-a-chip emulating fluid flow and peristalsis aids in elucidating the relationships between mechanical stimuli and the infectivity of pathogens.

Fig. 2.

Gut-on-a-chip for researching intestinal infection diseases

A gut-on-a-chip has been used to recapitulate the pathophysiology of infections caused by bacteria, viruses, and parasites.

Table 1.

Gut-on-a-chip systems for infectious disease research.

| Pathogen | Name | Cell types | Findings | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterium | Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) | Colon chip | Colon organoids Human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells (HIMECs) |

|

[14] |

| Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) |

Gut-on-a-chip | Caco-2 BBe cells |

|

[15] | |

| Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli-derived heat-stable enterotoxin A | Human Enteroid intestine-chip model | Jejunal enteroids |

|

[16] | |

| E. coli Hu734 | Gut-on-a-chip | Caco-2 BBe1 cells |

|

[17] | |

| Bifidobacterium breve (B. breve) | |||||

| Shigella flexneri (S. flexneri) | Intestine-chip | Caco-2/TC7 cells |

|

[18] | |

| Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) | Gut-on-a-chip | Caco-2 BBe cells |

|

[2] | |

| Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus (L. rhamnosus) | Intestine-on-chip | Caco-2 cells Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) |

|

[19] | |

| Lactiplantibacillus plantarum HY7715 (HY7715) | Gut-on-a-chip | Caco-2 cells HUVECs |

|

[20] | |

| LGG | HuMiX model | Caco-2 cells |

|

[21] | |

| Bacteroides caccae (B. caccae) | |||||

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (F. prausnitzii) | GuMI physiome platform | Colon organoids |

|

[22] | |

| Eubacterium rectale (E. rectale) | |||||

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (B. thetaiotaomicron) | |||||

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis (B. adolescentis) | Oxygen gradient device | Colon organoids |

|

[23] | |

| Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) | |||||

| B. adolescentis | AOI chip | Caco-2 BBe cells |

|

[24] | |

| Eubacterium hallii (E. hallii) | |||||

| Gut microbiota isolated from human stools | Intestine chip | Caco-2 cells HIMECs |

|

[25] | |

| Gut microbiota isolated from human stools | 3D bioengineered intestinal tissue | Intestinal enteroids Intestinal myofibroblasts |

|

[26] | |

| Virus | Coxsackievirus B1 (CVB1) | Gut-on-a-Chip | Caco2 BBe cells |

|

[27] |

| Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Gut-on-chip | Caco-2 cells HT-29 cells HUVECs Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) |

|

[28] | |

| NL63 coronavirus (NL63) | Intestine chip | Duodenal organoids HIMECs PBMCs |

|

[29] | |

| Parasite | Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii) | Intestinal tissue MPS | Caco-2 cells or jejunal organoids HUVECs PBMCs or neutrophils |

|

[30] |

| Cryptosporidium parvum(C. parvum) | Mini-gut | Intestinal organoids |

|

[10] | |

| Tritrichomonas muris (T. muris) | Caecal transgel organoids | Caecum organoids |

|

[31] | |

3.1. Gut-on-a-chip for studying bacterial infections

Intestinal microbiota includes facultative and obligate anaerobes. The former can grow under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, while the latter cannot survive in aerobic conditions. A gut-on-a-chip was used to co-culture intestinal epithelial cells with these bacteria for a long duration and to investigate their effects on the intestine.

3.1.1. Gut-on-a-chip for studying facultative anaerobe infections

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a facultative anaerobe that lives in the intestine. While many E. coli strains are non-pathogenic, some cause diarrhea and abdominal pain. Infectious diseases caused by pathogenic E. coli have been recapitulated using a gut-on-a-chip. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC), a pathogenic E. coli strain, produces the potent Shiga toxin. A gut-on-a-chip was utilized to elucidate the mechanisms underlying species differences in sensitivity to EHEC infection between humans and mice. The Colon Chip was generated by culturing colon organoids in the upper channel of a two-channel microfluidic device and human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells (HIMECs) in the lower channel [14]. EHEC was introduced into the upper channel after the Colon Chip was treated with human or murine microbiome metabolites (Hmm or Mmm) from the luminal side. The area of epithelial cell loss in the Colon Chip exposed to Hmm was five times larger than in that exposed to Mmm, suggesting that microbiome metabolites influence susceptibility to EHEC. Enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) attaches to and invades colonic epithelial cells, causing epithelial cell necrosis and ulceration. A gut-on-a-chip was used to recapitulate intestinal damage caused by EIEC infections. Kim et al. developed the gut-on-a-chip by culturing Caco-2 cells on a two-channel microfluidic device under continuous fluid flow and peristalsis-like motions [15]. The introduction of EIEC into the upper channel of the gut-on-a-chip resulted in bacterial colony formation, epithelial barrier dysfunction, and intestinal villus damage. EIEC-induced intestinal damage was ameliorated by treatment with VSL#3 formulation containing eight strains of probiotic bacteria. Moreover, the effect of heat-stable enterotoxin A produced from Enterotoxigenic E. coli on intestinal epithelial cells was elucidated using the Human Enteroid Intestine-Chip Model [16]. Other research using a gut-on-a-chip has also revealed that Bifidobacterium breve, a probiotic bacterium, protects the intestinal epithelial cells from E. coli-induced damage [17]. Thus, the intestinal pathophysiology of E. coli infection can be replicated using a gut-on-a-chip.

Shigella, a facultative anaerobe transmitted via the oral route, causes shigellosis. Similar to EIEC, Shigella invades intestinal epithelial cells and propagates to adjacent cells. Research using a gut-on-a-chip clarified that the mechanical stimuli modulated the Shigella infectivity in intestinal epithelial cells. Grassart et al. generated the Intestine-Chip by incorporating Caco-2 cells within a two-channel microfluidic device and introduced Shigella flexneri (S. flexneri) into the upper channel [18]. The colony-forming unit count of S. flexneri invading the epithelium was higher in the Intestine-Chip under stretching conditions than in those under static or flow-only conditions, suggesting that the invasion capacity of S. flexneri is enhanced by peristalsis. Notably, the propagation capacity of S. flexneri was promoted by both flow and stretching conditions, indicating that mechanical forces increase the infectivity of S. flexneri in a gut-on-a-chip.

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are commensal facultative anaerobes that ferment sugars into lactic acid. To co-culture intestinal cells with Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG), a probiotic strain of LAB, the gut-on-a-chip was generated by seeding Caco-2 cells on the upper channel of a two-channel microfluidic device [2]. LGG co-cultured with intestinal epithelial cells for over a week led to improve intestinal barrier functions in the gut-on-a-chip under fluidic flow and cyclic strain. By contrast, the barrier integrity of Caco-2 cells cultured in Transwell plates under static conditions was compromised by exposure to LGG for 48 h. These results suggest mechanical forces are important for co-culturing intestinal epithelial cells and LGG. Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus (L. rhamnosus) can protect the intestine against opportunistic pathogens. Maurer et al. developed the intestine-on-chip by incorporating Caco-2 cells in the lower channel of a two-channel microfluidic device and HUVECs in the upper channel [19]. L. rhamnosus and Candida albicans (C. albicans) were introduced into the lower channel of the intestine-on-chip. The overgrowth of C. albicans and its translocation from the epithelial to the endothelial side were suppressed by L. rhamnosus colonization in the intestine-on-a-chip. Another study using a gut-on-a-chip revealed that Lactiplantibacillus plantarum HY7715, a member of LAB, mitigated LPS-induced intestinal damage [20]. Therefore, a gut-on-a-chip is useful for long-term culture of LAB without damaging intestinal cells and for evaluating their intestinal protective effects.

3.1.2. Gut-on-a-chip for culturing obligate anaerobes

It has been challenging to co-culture obligate anaerobes with intestinal cells that require oxygen for survival. To overcome this problem, a gut-on-a-chip mimicking the oxygen gradient in the intestine has been developed. Shah et al. developed the HuMiX model by seeding Caco-2 cells on a device consisting of three co-laminar microchannels: a medium perfusion microchamber, a human epithelial cell culture microchamber, and a microbial culture microchamber [21]. By perfusing oxic and anoxic media in the medium perfusion and microbial culture microchambers, dissolved oxygen concentrations of 5.4 % and 0.8 % were achieved, respectively. LGG, a facultative anaerobe, and Bacteroides caccae (B. caccae), an obligate anaerobe, were successfully co-cultured with Caco-2 cells using the HuMiX model replicating the oxygen gradient. The gene expression and intracellular metabolite profiles of Caco-2 cells were altered by co-culturing with LGG and B. caccae. Zhang et al. established the gut microbiome (GuMI) physiome platform using a device that consists of apical and basolateral units separated by a flexible membrane [22]. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (F. prausnitzii), an obligate anaerobe, was co-cultured with primary colonic epithelial cells in the GuMI physiome platform. F. prausnitzii changed the expression of genes associated with HDAC and TLR–NF–κB signaling in epithelial cells. In particular, TLR3 and TLR4 expression was reduced by the butyrate produced by F. prausnitzii. Other obligate anaerobes, including Bifidobacterium adolescentis, Clostridium difficile, and Eubacterium hallii, were co-cultured with intestinal epithelial cells in a gut-on-a-chip [23,24]. Moreover, a complex human intestinal microbiota can be partially preserved using a gut-on-a-chip. Gut microbiota isolated from human stools were cultured in the Intestine Chip [25], which cultures Caco-2 cells and HIMECs, and in the 3D bioengineered intestinal tissue [26], containing human intestinal enteroids and myofibroblasts. Thirteen and 69 genera were maintained in these models, respectively. The interaction between obligate anaerobes and intestinal cells can be investigated using gut-on-a-chip systems that could replicate an anaerobic environment. While intestinal cells can be co-cultured with intestinal microbiota using a gut-on-a-chip, maintaining the microbial diversity within such systems remains challenging. In addition to developing a gut-on-a-chip that recapitulates the intestinal oxygen gradient, it is also necessary to optimize the components of a common culture medium to support the proliferation of intestinal cells and microbiota.

3.2. Gut-on-a-chip for studying viral infections

Coxsackievirus B (CVB) infection causes myocarditis or aseptic meningitis. Because CVB primarily replicates in the intestine, a gut-on-a-chip was used to study coxsackievirus B1 (CVB1) infection. The Gut-on-a-Chip was developed by seeding Caco-2 cells on a two-channel microfluidic device [27]. Caco-2 cells were exposed to CVB1 from the apical side and cultured under unidirectional flow and stretch conditions. The number of CVB1 virions replicated and released from intestinal cells was higher in the upper than in the lower channel at 24 h post-infection (hpi). CVB1-induced cytopathic effects were more severe at the flow outlet than at the inlet of the Gut-on-a-Chip. These results suggest that the polarized infection of CVB1 and the influence of fluid flow on its pathogenicity can be investigated using the Gut-on-a-Chip.

Coronaviruses, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and NL63 coronavirus (NL63), can infect not only the respiratory tract but also the intestine, causing gastrointestinal symptoms. To study SARS-CoV-2 infection, the gut-on-chip was generated by culturing Caco-2 and HT-29 cells in the upper channel of a two-channel microfluidic device, and HUVECs and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in the lower channel [28]. After introducing SARS-CoV-2 into the upper channel of the gut-on-chip, the virus infected intestinal epithelial cells and disrupted the E-cadherin-based adherens junctions. Although the viral Spike protein was not detected in HUVECs, VE-cadherin-based adherens junctions in HUVECs were damaged. Thus, intestinal epithelial and vascular endothelial damage was recapitulated in the SARS-CoV-2-infected gut-on-chip. In addition to recapitulating the infectious pathophysiology, Bein et al. evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of anti-viral drugs using NL63-infected gut-on-a-chip [29]. The Intestine Chip was developed by culturing biopsy-derived duodenal organoids in the upper channel of a two-channel microfluidic device and HIMECs in the lower channel. After introducing NL63 into the upper channel of the Intestine Chip, viral RNA expression increased between 24 and 48 hpi, coinciding with impaired intestinal barrier function at 48 hpi. The NL63-infected Intestine Chip was treated with nafamostat, an inhibitor of a protease crucial for NL63 infection, to evaluate its therapeutic efficacy. Nafamostat treatment reduced viral RNA expression in the Intestine Chip by approximately 50 %. These findings suggest that a gut-on-a-chip is useful for recapitulating virus-mediated intestinal damage and evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of drugs. Gut-on-a-chip models incorporating PBMCs are expected to be used for evaluating the efficacy of not only antiviral drugs but also vaccines. By elucidating the infectious pathophysiology and assessing the effect of therapeutic drugs and vaccines using a gut-on-a-chip, infection control measures can be promptly prepared in the event of emerging or re-emerging viral infections.

3.3. Gut-on-a-chip for studying parasite infection

Gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhea and bloody stool, are caused by ingesting food or water contaminated with parasites. Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii) is an intracellular protozoan parasite that causes toxoplasmosis. Although most individuals infected with T. gondii are asymptomatic or exhibit mild symptoms, immunocompromised patients can develop severe symptoms. A gut-on-a-chip was used to recapitulate the pathophysiology of T. gondii infections. A microdevice containing two hollow tubes within an ECM gel was fabricated [30]. Caco-2 cells or jejunal organoids were cultured in one tube, and HUVECs were cultured in the other to generate the intestinal tissue microphysiological system (MPS). T. gondii was introduced into the intestinal epithelial tube, while immune cells, such as PBMCs or neutrophils, were added to the endothelial tube. T. gondii infection increased the percentage of PBMCs adhering to endothelial cells in the intestinal tissue MPS two-fold. When neutrophils were added to the endothelial tube, they migrated to the T. gondii-infected epithelial tube and expressed high levels of genes involved in innate immune responses. These results suggest that immune responses caused by T. gondii infections can be recapitulated using the intestinal tissue MPS.

Cryptosporidium parvum (C. parvum) infects the intestine and causes cryptosporidiosis, leading to diarrhea. A gut-on-a-chip was generated to culture C. parvum for a long time and mimic its life cycle. The mini-gut was developed by culturing intestinal organoids in a device reproducing the topography and dimensions of the colon [10]. The mini-gut was infected with C. parvum by loading oocysts or sporozoites into its luminal side. Meronts, microgamonts containing microgametes, and newly formed oocysts were detected within epithelial cells. The production of new oocysts continued for at least four weeks in the mini-gut infected with C. parvum. The expression of interferon response genes was upregulated in intestinal epithelial cells of the mini-gut by C. parvum infection. Thus, C. parvum life cycle and the pathophysiology of cryptosporidiosis were recapitulated using the mini-gut. A gut-on-a-chip was also used to investigate the morphological changes in intestinal epithelial cells caused by Tritrichomonas muris, a parasite residing in the caecum of mice and rats [31]. Immune responses or the parasite life cycle in human cells can be recapitulated using a gut-on-a-chip. By utilizing this parasite infection model, it is anticipated that the mechanisms underlying the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms will be revealed.

A gut-on-a-chip is a valuable tool for understanding the pathophysiology of infectious diseases. Many other pathogens, such as Campylobacter, Norovirus, and Rotavirus, can infect the intestine and cause gastrointestinal symptoms. A gut-on-a-chip is expected to contribute to elucidating intestinal infectious diseases and developing effective therapeutic drugs.

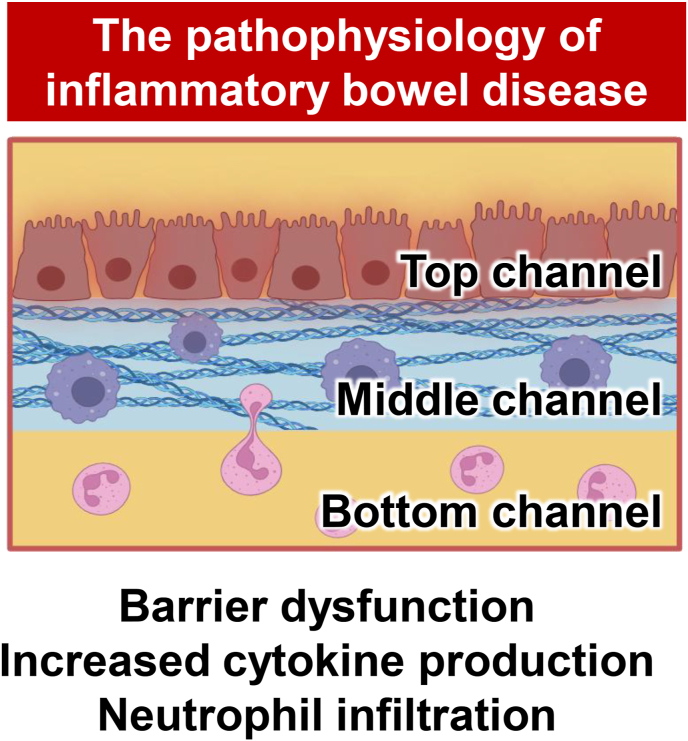

4. Gut-on-a-chip for recapitulating the pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the intestine. The global incidence of IBD increased by 88.30 % in 2021 compared to 1990 [32]. The onset mechanism remains unclear, and there is no curative treatment. Gut-on-a-chip has been developed to elucidate IBD pathophysiology (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Gut-on-a-chip for researching inflammatory bowel disease

A gut-on-a-chip has been used to mimic the pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease. The interaction between intestinal epithelial and immune cells can be investigated using a gut-on-a-chip.

The responses of intestinal epithelial and immune cells to excessive cytokines are associated with IBD progression. Inflammatory reactions in IBD were reproduced by treating a gut-on-a-chip with inflammatory cytokines. Apostolou et al. developed the Colon Intestine-Chip by seeding colonic biopsy-derived organoids in the upper channel of a two-channel microfluidic device and colon-specific microvascular endothelial cells in the lower channel [33]. Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) treatment decreased the epithelial layer confluency, altered the localization of tight junction proteins, such as ZO-1 and claudin 4, and increased the intestinal permeability in the Colon Intestine-Chip. These results suggest that intestinal barrier dysfunction can be recapitulated using the Colon Intestine-Chip treated with IFN-γ. It has also been reported that tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 1-beta (IL-1β) can induce IBD pathophysiology, including inflammatory responses and barrier dysfunction, in a gut-on-a-chip [34,35]. Other gut-on-a-chip systems were used to identify inflammation-associated signals. A Gut-on-a-Chip was generated by culturing Caco-2 cells on the OrganoPlate [36]. Combined treatment with IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1β increased the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 8 (IL-8) and C–C motif chemokine ligand 20 (CCL-20). RELA and MYD88 knockdown in Caco-2 cells within the Gut-on-a-Chip prevented the secretion of these inflammatory cytokines, suggesting that RELA and MYD88 are involved in IBD-associated inflammation.

Resident immune cells, activated by pathogens such as gut microbiota, generate an inflammatory milieu and enhance the recruitment of circulating immune cells, such as neutrophils, to the inflammation site. A gut-on-a-chip was used to recapitulate immune cell responses to bacterial components. The gut-on-a-chip was generated by seeding Caco-2 cells in the upper channel of a two-channel microfluidic device, with dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a bacterial component, injected into the upper channel and PBMCs introduced into the lower channel [37]. The intestinal barrier was disrupted, and PBMCs were recruited to the basal surface of Caco-2 cells in the gut-on-a-chip exposed to DSS and LPS, suggesting that immune cell recruitment can be recapitulated in the gut-on-a-chip.

Moreover, the interaction between resident and circulating immune cells was reproduced using a gut-on-a-chip by culturing Caco-2 cells in the top channel of the OrganoPlate and injecting an ECM gel containing THP1-derived macrophages into the middle channel [38]. After THP1-derived macrophages were activated by exposure to the bacterial components, LPS and N-formylmethionine-leucyl-phenylalanine, primary neutrophils were introduced into the bottom channel of the gut-on-a-chip. Neutrophils migrated to macrophages in the middle channel and induced the morphological change and cell death of Caco-2 cells. The epithelial damage was more severe when both THP1-derived macrophages and neutrophils were present than when only neutrophils were present. Thus, intestinal epithelial damage caused by the interaction between bacterial components-activated resident macrophages and neutrophils was recapitulated in the gut-on-a-chip.

While the crosstalk between intestinal epithelial and immune cells has been reproduced in a gut-on-a-chip treated with cytokines or bacterial components, genetic background is known to also play a role in the onset of IBD. A gut-on-a-chip incorporating IBD patient-derived intestinal organoids can help reveal the relationship between genetic mutations and IBD pathophysiology. These models may facilitate the elucidation of IBD etiology and the development of effective drugs.

5. Gut-on-a-chip for modeling oncogenesis

Colorectal cancer (CRC) has a high incidence and mortality rate, ranking second in incidence and third in mortality among all cancers [39]. CRC research has been performed using a gut-on-a-chip (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Gut-on-a-chip for researching oncogenesis

A gut-on-a-chip has been used to reproduce the progression of colorectal cancer. Abnormal cells harboring CRC driver gene mutations actively proliferate and form tumors.

A Gut-on-a-chip was previously generated to recapitulate CRC pathophysiology and evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of anticancer drugs. Lorenzo-Martín et al. developed the CRC mini-colon by seeding healthy colon organoids, along with CRC cells isolated from CRC biopsies, at a 99:1 ratio on a microfluidic device that mimics the topography and dimensions of colonic crypts [40]. Healthy colonic epithelial cells formed a monolayer, and CRC cells were integrated into the healthy epithelium. CRC cells proliferated, forming hyperplastic structures and full-blown tumors within 1 week, suggesting that tumor dynamics can be recapitulated in the CRC mini-colon. The combined treatment of SN-38, an irinotecan active metabolite, and AZD7762, a checkpoint kinase inhibitor, successfully eradicated CRC cell-derived tumors without damaging healthy epithelium. Conversely, treatment with 5-fluorouracil, known to induce gastrointestinal toxicity, suppressed CRC expansion but failed to eliminate tumors completely and caused damage to the healthy epithelium. These results indicate that the CRC mini-colon is useful for evaluating both the therapeutic efficacy and toxicity of anticancer drugs.

Oncogenesis was recapitulated by integrating gut-on-a-chip technology with optogenetics. The mini-colon was generated by culturing genetically engineered colon organoids that acquire CRC driver gene mutations in response to blue light exposure on microfluidic devices [41]. Blue light-exposed cells in the mini-colon accelerate proliferation, leading to tumor formation. Dense or cystic internal tumors developed when cells in the crypt or lumen area of the mini-colon, respectively, were targeted by blue light to induce mutations. Organoids were then established from tumors in the crypt or lumen area of the mini-colon, with crypt tumor-derived organoids exhibiting a higher proliferation rate than lumen tumor-derived organoids, suggesting that tumor-initiating cell niche may affect tumor characteristics.

The effects of anticancer drugs on healthy cells and CRC cells were recapitulated using a gut-on-a-chip co-culturing both cell types. By applying this system to pharmaceutical research, it is expected that anticancer drugs with a low risk of side effects—selectively targeting cancer cells without affecting healthy cells—can be developed. Moreover, the initiation and progression of CRC were recapitulated using a gut-on-a-chip in which an oncogenic mutation was induced. The transition from adenoma to CRC is driven by the stepwise accumulation of oncogenic mutations in healthy cells over more than 10 years [42,43]. By culturing a gut-on-a-chip long-term and gradually introducing genetic mutations, the CRC transition could be reproduced in vitro to provide insights into how genetic mutations affect oncogenesis and drug susceptibility.

6. Challenges and future perspectives

To investigate intestinal functional changes induced by mechanical stimulation and the progression of intestinal diseases in more detail, it is necessary to develop a gut-on-a-chip capable of monitoring the cell state continuously. Recently, gut-on-a-chip systems with electrodes [44] or oxygen sensors [45] have been developed to evaluate intestinal epithelial barrier function and oxygen concentrations in the culture medium. Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology for imaging analysis has also advanced significantly. By analyzing massive amounts of image data obtained from gut-on-a-chip models that recapitulate intestinal diseases, AI can be used to more precisely characterize disease-mediated histological changes. A gut-on-a-chip designed to monitor various parameters longitudinally and simultaneously is expected to aid in building a comprehensive understanding of the pathophysiology of intestinal diseases.

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), a silicone elastomer, is widely used to fabricate various microfluidic devices—such as two-channel microfluidic devices—due to its low cost and ease of processing. However, to apply gut-on-a-chip models in pharmaceutical research, it is crucial to fabricate microfluidic devices using materials other than PDMS. PDMS is hydrophobic and easy to absorb small molecule compounds. To avoid the absorption of small molecule drugs into the PDMS, we recently developed a microfluidic device from perfluoropolyether (PFPE) and generated a Gut-Liver-on-a-Chip by culturing Caco-2 cells and primary human hepatocytes for pharmaceutical research [46]. We hope that drug development against intestinal diseases will be promoted by using gut-on-a-chip models.

Moreover, a gut-on-a-chip incorporating intestinal cells derived from patients with intestinal diseases will help determine the relationship between genetic mutations and diseases and advance personalized medicine. We believe that gut-on-a-chip systems can accurately recapitulate intestinal function and model disease pathophysiology in vitro, thereby facilitating the development of therapeutic agents.

7. Conclusion

In this review, we examined the development of the gut-on-a-chip and its application in recapitulating intestinal functions and disease pathophysiology. The relationship between intestinal disease and mechanical stimulation, such as body fluid flow and peristalsis, has been elucidated using a gut-on-a-chip. The interaction between intestinal epithelial and immune cells was also reproduced in a gut-on-a-chip. We believe that gut-on-a-chip systems can accurately recapitulate intestinal function and model disease pathophysiology in vitro, thereby facilitating the development of therapeutic agents.

Author contributions

Writing - original draft; F.Y. and S.D.

Writing - review & editing; F.Y., S.D. and K.T.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Kelvin Hui (Kyoto University) for critical reading of the manuscript. Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4 were created with BioRender.com. This research was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (JP21gm1610005, JP23jf0126002), Japan Science and Technology Agency, ACT-X (JPMJAX222A) and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number 24K23052.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of the Japanese Society for Regenerative Medicine.

This article is written by the recipient of The JSRM Young Investigator’s Awards (Basic Researches) 2024.

References

- 1.Hasibeder W. Gastrointestinal microcirculation: still a mystery? Br J Anaesth. 2010;105:393–396. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim H., Huh D., Hamilton G., Ingber D. Human gut-on-a-chip inhabited by microbial flora that experiences intestinal peristalsis-like motions and flow. Lab Chip. 2012;12:2165–2174. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40074j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim H., Ingber D. Gut-on-a-Chip microenvironment induces human intestinal cells to undergo villus differentiation. Integr Biol. 2013;5:1130–1140. doi: 10.1039/c3ib40126j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Workman M., Gleeson J., Troisi E., Estrada H., Kerns S., Hinojosa C., et al. Enhanced utilization of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived human intestinal organoids using microengineered chips. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;5:669–677.e662. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin W., Hinojosa C., Ingber D., Kim H. Human intestinal morphogenesis controlled by transepithelial morphogen gradient and flow-dependent physical cues in a microengineered gut-on-a-chip. iScience. 2019;15:391–406. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2019.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasendra M., Tovaglieri A., Sontheimer-Phelps A., Jalili-Firoozinezhad S., Bein A., Chalkiadaki A., et al. Development of a primary human Small Intestine-on-a-Chip using biopsy-derived organoids. Sci Rep. 2018;8:2871. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21201-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yin J., Sunuwar L., Kasendra M., Yu H., Tse C., Talbot C., et al. Fluid shear stress enhances differentiation of jejunal human enteroids in Intestine-Chip. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2021;320:G258–G271. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00282.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deguchi S., Kosugi K., Takeishi N., Watanabe Y., Morimoto S., Negoro R., et al. Construction of multilayered small intestine-like tissue by reproducing interstitial flow. Cell Stem Cell. 2024;31:1315–1326.e1318. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2024.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trietsch S., Naumovska E., Kurek D., Setyawati M., Vormann M., Wilschut K., et al. Membrane-free culture and real-time barrier integrity assessment of perfused intestinal epithelium tubes. Nat Commun. 2017;8:262. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00259-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nikolaev M., Mitrofanova O., Broguiere N., Geraldo S., Dutta D., Tabata Y., et al. Homeostatic mini-intestines through scaffold-guided organoid morphogenesis. Nature. 2020;585:574–578. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2724-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitrofanova O., Nikolaev M., Xu Q., Broguiere N., Cubela I., Camp J., et al. Bioengineered human colon organoids with in vivo- like cellular complexity and function. Cell Stem Cell. 2024;31:1175–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2024.05.007. E1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y., Gunasekara D., Reed M., DiSalvo M., Bultman S., Sims C., et al. A microengineered collagen scaffold for generating a polarized crypt-villus architecture of human small intestinal epithelium. Biomaterials. 2017;128:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jang Y., Kim H., Oh J. An array of carbon nanofiber Bundle_Based 3D in vitro intestinal microvilli for mimicking functional and physical activities of the small intestine. Small. 2024;20 doi: 10.1002/smll.202404842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tovaglieri A., Sontheimer-Phelps A., Geirnaert A., Prantil-Baun R., Camacho D., Chou D., et al. Species-specific enhancement of enterohemorrhagic E-coli pathogenesis mediated by microbiome metabolites. Microbiome. 2019;7:43. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0650-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim H., Li H., Collins J., Ingber D. Contributions of microbiome and mechanical deformation to intestinal bacterial overgrowth and inflammation in a human gut-on-a-chip. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E7–E15. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522193112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sunuwar L., Yin J., Kasendra M., Karalis K., Kaper J., Fleckenstein J., et al. Mechanical stimuli affect Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin-cyclic GMP signaling in a human enteroid intestine-chip model. Infect Immun. 2020;88 doi: 10.1128/IAI.00866-19. 00819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan L., de Haan P., Peterson B., de Jong E., Verpoorte E., van der Mei H., et al. Visualization of bacterial colonization and cellular layers in a gut-on-a-chip system using optical coherence tomography. Microsc Microanal. 2020;26:1211–1219. doi: 10.1017/S143192762002454X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grassart A., Malardé V., Gobba S., Sartori-Rupp A., Kerns J., Karalis K., et al. Bioengineered human organ-on-chip reveals intestinal microenvironment and mechanical forces impacting Shigella infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;26:435–444.e434. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maurer M., Gresnigt M., Last A., Wollny T., Berlinghof F., Pospich R., et al. A three-dimensional immunocompetent intestine-on-chip model as in vitro platform for functional and microbial interaction studies. Biomaterials. 2019;220 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeon M., Choi Y., Mo S., Ha J., Lee Y., Lee H., et al. Contributions of the microbiome to intestinal inflammation in a gut-on-a-chip. Nano convergence. 2022;9:8. doi: 10.1186/s40580-022-00299-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah P., Fritz J., Glaab E., Desai M., Greenhalgh K., Frachet A., et al. A microfluidics-based in vitro model of the gastrointestinal human-microbe interface. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J., Huang Y., Yoon J., Kemmitt J., Wright C., Schneider K., et al. Primary human colonic mucosal barrier crosstalk with super oxygen-sensitive faecalibacterium prausnitzii in continuous culture. Méd Sur. 2021;2:74–98.e79. doi: 10.1016/j.medj.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim R., Attayek P., Wang Y., Furtado K., Tamayo R., Sims C., et al. An in vitro intestinal platform with a self-sustaining oxygen gradient to study the human gut/microbiome interface. Biofabrication. 2019;12 doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/ab446e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin W., Wu A., Massidda M., Foster C., Thomas N., Lee D., et al. A robust longitudinal Co-culture of obligate anaerobic gut microbiome with human intestinal epithelium in an anoxic-oxic interface-on-a-chip. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2019;7:13. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2019.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jalili-Firoozinezhad S., Gazzaniga F., Calamari E., Camacho D., Fadel C., Bein A., et al. A complex human gut microbiome cultured in an anaerobic intestine-on-a-chip. Nat Biomed Eng. 2019;3:520–531. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0397-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y., Rudolph S., Longo B., Pace F., Roh T., Condruti R., et al. Bioengineered 3D tissue model of intestine epithelium with oxygen gradients to sustain human gut microbiome. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2022;11 doi: 10.1002/adhm.202200447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villenave R., Wales S., Hamkins-Indik T., Papafragkou E., Weaver J., Ferrante T., et al. Human gut-on-A-chip supports polarized infection of coxsackie B1 virus in vitro. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo Y., Luo R., Wang Y., Deng P., Song T., Zhang M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 induced intestinal responses with a biomimetic human gut-on-chip. Sci Bulletin. 2021;66:783–793. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2020.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bein A., Kim S., Goyal G., Cao W., Fadel C., Naziripour A., et al. Enteric coronavirus infection and treatment modeled with an immunocompetent human intestine-on-A-chip. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.718484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humayun M., Ayuso J., Park K., Di Genova B., Skala M., Kerr S., et al. Innate immune cell response to host-parasite interaction in a human intestinal tissue microphysiological system. Sci Adv. 2022;8:eabm8012. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abm8012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hofer M., Duque-Correa M., Lutolf M. Patterned gastrointestinal monolayers with bilateral access as observable models of parasite gut infection. Nat Biomed Eng. 2024 doi: 10.1038/s41551-024-01313-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin D., Jin Y., Shao X., Xu Y., Ma G., Jiang Y., et al. Global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease, 1990-2021: insights from the global burden of disease 2021. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2024;39:139. doi: 10.1007/s00384-024-04711-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Apostolou A., Panchakshari R., Banerjee A., Manatakis D., Paraskevopoulou M., Luc R., et al. A novel microphysiological colon platform to decipher mechanisms driving human intestinal permeability. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;12:1719–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gijzen L., Marescotti D., Raineri E., Nicolas A., Lanz H., Guerrera D., et al. An intestine-on-a-chip model of plug-and-play modularity to study inflammatory processes. Slas Technology. 2020;25:585–597. doi: 10.1177/2472630320924999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naumovska E., Aalderink G., Valencia C., Kosim K., Nicolas A., Brown S., et al. Direct on-chip differentiation of intestinal tubules from induced pluripotent stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:4964. doi: 10.3390/ijms21144964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beaurivage C., Naumovska E., Chang Y., Elstak E., Nicolas A., Wouters H., et al. Development of a gut-on-a-chip model for high throughput disease modeling and drug discovery. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:5661. doi: 10.3390/ijms20225661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shin W., Kim H. Intestinal barrier dysfunction orchestrates the onset of inflammatory host-microbiome cross-talk in a human gut inflammation-on-a-chip. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E10539–E10547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1810819115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gjorevski N., Avignon B., Gérard R., Cabon L., Roth A., Bscheider M., et al. Neutrophilic infiltration in organ-on-a-chip model of tissue inflammation. Lab Chip. 2020;20:3365–3374. doi: 10.1039/d0lc00417k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bray F., Laversanne M., Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R., Soerjomataram I., et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Ca Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229–263. doi: 10.3322/caac.21834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorenzo-Martin L., Broguiere N., Langer J., Tillard L., Nikolaev M., Coukos G., et al. Patient-derived mini-colons enable long-term modeling of tumor-microenvironment complexity. Nat Biotechnol. 2024 doi: 10.1038/s41587-024-02301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lorenzo-Martín L., Hübscher T., Bowler A., Broguiere N., Langer J., Tillard L., et al. Spatiotemporally resolved colorectal oncogenesis in mini-colons ex vivo. Nature. 2024;629:450–457. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07330-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fearon E., Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao C., Yamada H. Genomic instability and colon carcinogenesis: from the perspective of genes. Front Oncol. 2013;3:130. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Henry O., Villenave R., Cronce M., Leineweber W., Benz M., Ingber D. Organs-on-chips with integrated electrodes for trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEER) measurements of human epithelial barrier function. Lab Chip. 2017;17:2264–2271. doi: 10.1039/c7lc00155j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grant J., Lee E., Almeida M., Kim S., LoGrande N., Goyal G., et al. Establishment of physiologically relevant oxygen gradients in microfluidic organ chips. Lab Chip. 2022;22:1584–1593. doi: 10.1039/d2lc00069e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang M., Sasaki Y., Sakagami R., Minamikawa T., Tsuda M., Ueno R., et al. Perfluoropolyether-based gut-liver-on-a-chip for the evaluation of first-pass metabolism and oral bioavailability of drugs. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2024;10:4635–4644. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.4c00605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]