Abstract

Protein polysulfidation (Pr–S n H, n ≥ 2) is a type of post-translational modification that plays multiple physiological functions. Detecting Pr–S n H remains challenging due to the high reactivity of −S n H groups and their similarity to other thiol-based modifications. Here, we report the development of a new biotinylated tag, HPB, which is derived from β-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethyl iodoacetamide (HPE-IAM). HPB demonstrates superior performance over the traditional iodoacetamide (IAM)-derived biotin tag IAB, especially in minimizing off-target alkylation and preserving polysulfide chains. After protocol optimization, we achieved a 73.3% accuracy rate in proteomic scale Pr–S n H detection. Further, we found that polysulfides can modify other amino acids besides cysteine, including histidine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan, by introducing −SH or −SSH groups into their heterocyclic/phenyl rings. This leads to the detection accuracy rate of all current methods being less than 100%. Nonetheless, this study provides a reliable tool for detecting protein polysulfidation from complex cellular backgrounds.

1. Introduction

Polysulfides, including hydrogen polysulfides (HS n H, n ≥ 2), glutathione polysulfides (GS n H, n ≥ 2), and organic polysulfides (RS n R, n ≥ 2), are essential cellular metabolites that play important physiological and pathological roles in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. − As antioxidants, polysulfides can directly scavenge lipid radicals, reducing the risk of ferroptosis. − Polysulfides also can react with cysteine thiols of proteins (−SH) to form polysulfidated proteins (Pr–S n H, n ≥ 2). − This post-translational modification (termed as protein sulfhydration or polysulfidation) not only prevents irreversible oxidation of protein thiols but also regulates protein functions, thereby influencing various biological processes, such as metabolism, , transcription network, , ion channel functionality, , and others.

Several methods have been developed to detect protein polysulfidation. However, the highly reactive and degradable nature of polysulfidated thiol (−S n H), combined with its chemical similarities to thiol (−SH), sulfenic acid (−SOH), S-nitrosothiol (−SNO), and disulfide (−S–S−), poses significant challenges for distinguishing protein polysulfidation from other modifications. , Initially, Mustafa et al. applied S-methylmethanethiosulfonate (MMTS) and N-(6-(biotinamido)hexyl)-3′-(2′-pyridyldithio)propionamide (Biotin–HPDP) to detect protein polysulfidation. The assumption was that MMTS exclusively blocks −SH, while Biotin-HPDP can tag −SSH. However, later studies found that MMTS also blocks −S n H, which leads to low selectivity of this method. Subsequently, Zhang et al. and Zivanovic et al. proposed two tag-switch methods. They utilized electrophilic reagents such as methylsulfonyl benzothiazole (MSBT) or 4-chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan (NBF–Cl) to tag both −SH and −S n H groups, followed by a switching step during which only tagged −SSH is selectively labeled by CN–Biotin (a biotinylated cyanoacetic acid tag) or DCP–Bio1 (a biotinylated dimedone-based probe). While the efficiency of these methods is improved to some extent, the specificity of electrophilic reagents toward −S n H and the efficiency of label switching may require further validation and improvement. ,, Gao et al. and Dóka et al. introduced BTA and ProPerDP methods, respectively. Both methods utilize alkylating agents, N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) or iodoacetamide (IAM)-derived biotin tags (IAB and NEB), to label Pr–S n H, followed by capturing biotinylated proteins (Pr–SS–biotin) with streptavidin affinity magnetic beads. The last step is using dithiothreitol (DTT) or tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) to break the disulfide bond of Pr–S n –biotin to release captured proteins with −S n H. Questions on these two methods mainly focus on selectivity or efficiency of NEM and IAM. ,−

Recently, the IAM derivative β-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethyl iodoacetamide (HPE-IAM) was shown to significantly outperform NEM and IAM in preserving the −S n H groups. This improved performance is likely due to the hydroxyphenyl residue in HPE-IAM, which can inhibit the alkaline hydrolysis of labeled −S n H. Building on this advancement, we developed a new biotin tag termed HPB (β-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethyl iodoacetamide-derived biotin), which is synthesized by conjugating HPE-IAM with biotin. Our results demonstrate that HPB outperforms traditional reagents such as IAB (iodoacetamide-derived biotin) in both preserving and efficiently labeling polysulfidated proteins, offering high specificity in the analysis of proteomic Pr–S n H. By optimizing the labeling protocol and incorporating a precipitation–resolubilization step, we further enhanced the detection accuracy rate of polysulfidated proteins. This study provides a reliable tool for detecting and investigating protein polysulfidation in complex cellular backgrounds.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Strains, Cell Lines, and Reagents

All strains, human cells, and plasmids are listed in Table S1. Escherichia coli strains were cultured in lysogeny broth (LB) at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. The HT29 cell line (from ATCC) was maintained in McCoy’s 5A medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Biotin, 1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl) carbodiimide (EDCI), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), tert-butoxycarbonyl-tyrosine (BOC-l-tyrosine), dichloromethane (DCM), ethyl acetate (EAC), diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), chloroacetyl chloride (DMF), potassium iodide (KI), reduced glutathione (GSH), S8 (99.9% purity), sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS), 5,5′-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), and HPE-IAM were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai, China). EZ-Link Iodoacetyl-PEG2-Biotin (IAB) was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Shanghai, China). S8 solution was prepared as reported previously. Briefly, a saturated solution was made by dissolving excess sulfur powder in acetone. The concentration of saturated acetone sulfur was determined as 17 mM. Polysulfide (H2S n ) solution was prepared following the established protocol. GSSH was synthesized using the method outlined in Ref .

2.2. Synthesis of HPB

Step 1: biotin (2.0 mM), EDCI (3.0 mM), and DMAP (20 mM) were successively added to a round-bottom flask containing anhydrous DCM at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred overnight until biotin had fully reacted. A solution of BOC-l-tyrosine (2.4 mM) in DCM was then added dropwise at room temperature. Reaction progress was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Upon completion, the mixture was diluted and extracted with DCM. The organic phase was washed with saturated sodium bicarbonate and saturated brine, combined, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography.

Step 2: under argon, the intermediate (1.5 mM) was dissolved in 5 mL of ethyl acetate in a round-bottom flask. Subsequently, 3 mL of 3 N HCl was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature. Progress was checked by TLC. When complete, the reaction mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate, washed with saturated sodium bicarbonate and brine, dried over sodium sulfate, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by fast column chromatography.

Step 3: under argon, the resulting intermediate (1.0 mM) was dissolved in DCM, and DIPEA (2.0 mM) was added. The solution was cooled to 0 °C, and chloroacetyl chloride (1.2 mM) was slowly added, keeping the temperature between 0 and 10 °C. The mixture was then diluted, extracted with ethyl acetate, washed with saturated sodium bicarbonate and brine, dried over sodium sulfate, and concentrated. The product was purified by fast column chromatography.

Step 4: the final intermediate (0.5 mM) was dissolved in 2 mL of DMF under argon, and KI (1.0 mM) was added. The reaction proceeded at room temperature until the starting material was fully consumed. After dilution with water, the mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate, washed with saturated sodium bicarbonate and brine, dried, and concentrated. The crude product was purified by fast column chromatography to yield the target product HPB.

2.3. Reaction of HPB, HPE-IAM and IAB with GSSH

GSSH was prepared by mixing equal amounts of 17 mM GSH in 100 mM potassium phosphate (KPi) buffer (pH 7.4) with a saturated sulfur solution (17 mM) determined by cold cyanidation. To 100 μL of 0.5 mM GSSH, 30 μL of 10 mM IAB (dissolved in KPi, pH 8.0), HPB (dissolved in methanol), or HPE-IAM (dissolved in methanol) was added. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 40 min in the dark. Following the reaction, the samples were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 3 min, and the supernatant was analyzed by liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (LC–ESI-MS).

To quantify the reaction products, we employed external standards. LC–MS calibration curves were constructed using different concentrations of HPE-IAM (10 μM, 50 μM, 100 μM, and 500 μM) and GSSG (10 μM, 50 μM, 100 μM, and 200 μM). The reaction products GS-Alk, GSS-Alk, and GSSS-Alk, as well as reduced-IAB, were quantified by using the HPE-IAM calibration curve. The reaction product GS4G was quantified using the GSSG calibration curve.

2.4. LC–ESI-MS Analysis

The analysis procedure was performed as previously described. In summary, the samples underwent liquid chromatography (LC) using an InertSustain C18 column (Shimadzu, Japan) interfaced with a high-resolution Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Ultimate 3000, Bruker impact HD, Germany). The samples were introduced into the LC system via the loading pump, with 0.25% acetic acid serving as mobile phase A and 100% methanol as mobile phase B. Over the initial minute, the concentration of mobile phase B was ramped up from 7.5% to 52.5% and held constant for 15 min. At the 15 min mark, the concentration of mobile phase B was further increased to 55%, then to 100%, and sustained for an additional 5 min. At 20.1 min, mobile phase B was reduced to 7.5% and maintained at this level until the completion of the analysis at 31 min. The electrospray ionization (ESI) source temperature was set to 200 °C, and the ion spray voltage was set at 4.5 kV. Nitrogen was employed as a nebulizer and drying gas. The acquired data were processed using Data Analysis 4.2 software.

2.5. Reaction of IAB/HPB with Peptides

Peptides 1 (P1) and 2 (P2) were synthesized by GenScript (China, Nanjing). First, 1 mg of peptide powder was dissolved in 1 mL of ddH2O to give a 0.3 mM solution, which was further diluted to 0.1 mM with PBS. Next, 0.4 μL of TCEP was added to 200 μL of the peptide solution (final concentration: 0.2 mM), and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min to ensure that the peptides remained in a reduced state.

Without H2S n treatment: the peptide solution was divided into two 100 μL portions. To each portion, 12 μL of either 25 mM IAB or 25 mM HPB (final concentration: 3 mM) was added. The mixtures were then incubated for 40 min at 37 °C in the dark.

With H2S n treatment: 10 μL of 20 mM H2S n was added to 200 μL of the 0.1 mM peptide solution and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h in the dark. The sample was then divided into two portions. Next, 20 μL of 25 mM IAB or HPB was added (final concentration: 5 mM), and the mixtures were incubated under the same conditions (40 min at 37 °C in the dark).

After the reactions, salts and other small molecules were removed by using a C18 spin column (Thermo Fisher Scientific, China). The purified peptides were finally dissolved in ddH2O and analyzed by LC–MS.

2.6. Protein Expression and Purification

E. coli BL21(DE3) strains containing the expression plasmid pET30-Trx1m were cultivated in a LB medium supplemented with 100 μg/mL kanamycin. Upon reaching an optical density (OD600) of 0.6–0.8, isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was introduced to a final concentration of 0.3 mM to induce protein expression, and the culture was continued for an additional 18 h at 20 °C. The bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation and then resuspended in a lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 0.5 mM DTT, and pH 8.0). Cell lysis was achieved using a high-pressure homogenizer, model SPCH-18 (Stansted), and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 g for 15 min. The supernatant was subsequently applied to a Ni-NTA agarose affinity resin for protein purification, following the manufacturer’s protocol. The purified protein was desalted using a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare) that had been pre-equilibrated with a desalination buffer (0.5 mM DTT, 50 mM Tris-HCl, and 10% glycerin, pH 7.4). The finally obtained protein solutions were stored in an icebox in the anaerobic incubator before reacting with HSSH and other reagents. The purity of the protein was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), and the protein concentration was quantified using a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China).

2.7. Reactions of HPB, HPE-IAM, or IAB with Trx1m

For reactions with Trx1m (100 μM), 0.5 μL of 100 mM TCEP was added to 250 μL of Trx1m and the mixture was incubated for another 10 min. Next, 10 μL of 20 mM H2S n was introduced and left at room temperature for 30 min. After this, the protein sample was split into two portions, each receiving 30 μL of 25 mM IAB or HPE–IAM or HPB. The mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 40 min, and unreacted alkylating reagents were removed using 3K Amicon Ultra centrifugation filters (Sigma-Aldrich, China). Finally, molecular weight changes were determined by LC–MS.

To investigate the effect of the precipitation–solubilization process on persulfidation, Trx1m was divided into two portions after H2S n treatment. One portion was treated with HPB at 37 °C for 40 min, avoiding light exposure. Then, three volumes of cold acetone were added, and the mixture was incubated at −20 °C for 1 h. The sample was centrifuged to remove the supernatant, and the protein was resuspended in 100 μL of 8 M urea (pH 7.4–8.0). The protein was desalted using 3K Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters. The second portion of Trx1m was treated by adding three volumes of cold acetone and incubating at −20 °C for 1 h. After centrifugation to remove the supernatant, 100 μL of 8 M urea and 20 μL of HPB (25 mM) were added to resuspend the protein. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 40 min with gentle shaking (600 rpm) and then desalted using ultrafiltration tubes. Molecular weight changes were analyzed by LC–MS.

2.8. Peptides and Protein ESI-MS Analysis

The molecular weight of the whole protein was analyzed using ESI-MS. High-resolution Q-TOF mass spectrometry (Ultimate 3000, Burker impact HD, GER) was used. Mobile phase A consisted of 0.1% formic acid (FA), while mobile phase B was a mixture of acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid (FA). Initially, the concentration of mobile phase B was set at 5% for the first 7 min of the analysis. At the 7 min mark, the mobile phase composition was dynamically adjusted to a blend comprising 10% of 0.1% FA and 90% of the acetonitrile/0.1% FA mixture. This mixture was maintained for a duration of 3 min, after which mobile phase B was reduced back to 5%, and this condition was sustained for an additional 3 min. The flow rate throughout the process was meticulously controlled at 0.5 mL/min. The Q-TOF mass spectrometer was equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source operating in a positive ion mode, with a capillary voltage set to 3500 V. The acquired data were subjected to deconvolution and comprehensive analysis using Data Analysis 4.2 software.

2.9. Reaction Kinetic Experiments of HPB with GSSH, Peptides, and Proteins

The reaction kinetics of HPB were determined by monitoring the residual thiol groups. For the reaction kinetics assay with GSSH, different concentrations of GSSH (0.25, 0.5, and 1 mM) were mixed with HPB (100 mM) in KPI buffer (100 mM, pH 7.4) with a total volume of 1 mL. At various time points (0, 30, 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 20, 30, and 40 min), 100 μL of the reaction mixture was sampled, and 10 μL of DTNB (200 mM) was added. The absorbance at 412 nm was measured using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek, USA) to determine the remaining GSSH concentration.

For the kinetic assay with peptide P1, different concentrations of P1 (150 μM, 200 μM, and 300 μM) were mixed with HPB (100 mM) in KPI buffer (100 mM, pH 7.4) with a total volume of 1 mL. At the same time points, 100 μL of the reaction mixture was sampled, and 5 μL of DTNB (200 mM) was added. The absorbance at 412 nm was measured to determine the remaining thiol concentration in the peptide.

For the kinetic assay with protein Trx1m, different concentrations of Trx1m (62.5 μM, 125 μM, and 250 μM) were mixed with HPB (100 mM) in Tris-HCl buffer (100 mM, pH 7.4) with a total volume of 1 mL. At the same time points, 100 μL of the reaction mixture was sampled, and 5 μL of DTNB (200 mM) was added. The absorbance at 412 nm was measured to determine the remaining thiol concentration in the protein.

The apparent rate constant (k obs) was calculated by plotting the ln[−SH0/–SH t ] values against the reaction time.

2.10. Detection of Polysulfidated Proteins from HT29 Cells

HT29 cells in 10 cm dishes were harvested at 80–90% confluence. After the culture medium was discarded, cells were washed with PBS, digested with trypsin for approximately 3 min, and the resulting suspension was transferred to 2 mL tubes (∼1 × 107 cells per dish). Cells were spun down at 200 g for 5 min at 4 °C, washed three times with PBS, and then resuspended in 400 μL of RIPA lysis buffer (containing 1% protease inhibitor and 5 mM IAB or HPB, pH 7.6). The suspension was incubated on ice for 5 min. Next, 1.6 mL of precooled acetone was added, and samples were placed at −20 °C for 1 h. After centrifugation at 13,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was washed twice with 100% acetone. Acetone was evaporated for ∼3 min, and 400 μL of redissolution buffer (8 M urea, 250 mM HEPES, 5 mM IAB or HPB, pH 7.6–8.0) was added. The sample was incubated at 37 °C with shaking for 50 min in the dark. The reaction was then desalted in a 10 kDa ultrafiltration tube, with the buffer replaced by TBS (20 mM Tris, 0.137 M NaCl, pH 7.6). Protein concentration was measured by the Bradford method (Beyotime Biotechnology, China).

Streptavidin affinity magnetic beads (2 mL) were divided into two tubes; the supernatant was removed on a magnetic rack, and 1 mL of TBS was used to wash the beads. Then, 350 μg of protein was incubated with 2 mL of the magnetic beads for 1 h at room temperature while being shaken (170 μg of protein per 1 mL of beads). The supernatant was discarded using a magnetic rack, and the beads were washed six times with TBS. Next, 100 μL of 8 mM TCEP (diluted in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0) was added, and the mixture was shaken for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. The eluted supernatant was collected by using a magnetic rack. Samples were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE and visualized using a Fast Silver Stain Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.11. Detection of Persulfide-Modified Peptides

Cell collection, lysis, and protein precipitation with acetone were performed as described above. After reacting proteins with IAB or HPB, the samples were desalted using 3K Amicon Ultra centrifugation filters (Sigma-Aldrich, China), and 25 mM NH4HCO3 was used as the replacement buffer. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method, and 350 μg of protein was digested overnight (12–16 h) with trypsin at 37 °C (enzyme-to-protein ratio of 1:25). On the second day, the digested samples were heated at 95 °C for 10 min and then incubated with 2 mL of streptavidin affinity magnetic beads for 1 h at room temperature with shaking (170 μg of peptide per 1 mL of beads). The supernatant was removed on a magnetic rack, and the beads were washed six times with TBS. Next, 100 μL of 8 mM TCEP (in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0) was added, and the mixture was shaken for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. The eluted supernatant was collected, and 15 mM iodoacetamide (IAM) was added, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 30 min in the dark. Salts were removed using a C18 spin column, and peptides were eluted with 70% acetonitrile, dried, and reconstituted in 10 μL of deionized water for LC–MS analysis.

2.12. LC–MS/MS

LC–MS/MS analysis was performed using the Prominence nano-LC system (Shimadzu, Shanghai, China) equipped with a custom-made silica column (75 μm × 15 cm) packed with 3 μm Reprosil-Pur 120 C18-AQ. The elution process involved a 100 min gradient ranging from 0% to 100% of solvent B (0.1% formic acid in 98% acetonitrile) at a flow rate of 300 nL/min. Solvent A was composed of 0.1% formic acid in 2% acetonitrile. The eluent was ionized and electrosprayed via an LTQ-Orbitrap Velos Pro CID mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Shanghai, China), which operated in a data-dependent acquisition mode using Xcalibur 2.2.0 software (Thermo Scientific). Full-scan MS spectra (ranging from 400 to 1800 m/z) were detected in the Orbitrap with a resolution of 60,000 at 400 m/z. The acquired data were subjected to comprehensive analysis using Proteome Discoverer 3.2 software.

2.13. Reaction of Amino Acids with H2S n

An aqueous solution of histidine, proline, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan was prepared at 1 mM each and then diluted to 0.1 mM with Kpi buffer (100 mM, pH 7.4). Next, 2.5 μL of 20 mM H2S n was added to 100 μL of the 0.1 mM amino acid solution, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h in the dark. Afterward, 8 μL of 25 mM mBBr or HPE-IAM was added, and the reaction was continued for 30 min at room temperature, also in the dark. The products were analyzed by LC–MS/MS.

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis and Structure Confirmation of HPB

HPB was synthesized through a four-step process (Figure A). Step 1: biotin, 1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl) carbodiimide (EDCI), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), and tert-butoxycarbonyltyrosine were mixed and reacted to produce intermediate I, which was purified using silica gel fast column chromatography. Step 2: intermediate I was reacted with hydrochloric acid (HCl) to remove the Boc protecting group. The product was intermediate II. Step 3: intermediate II was reacted with diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) and chloroacetyl chloride to produce intermediate III, which contains a chlorine atom. Step 4: the chlorine atom in intermediate III was replaced by an iodine atom through reaction with potassium iodide (KI). The final product was named HPB.

1.

Synthesis and structure confirmation of HPB. (A) Step of HPB synthesis. (B–C) LC–MS/MS analysis of the synthesized HPB. (D) 1H NMR spectrum of HPB. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker spectrometer with a 5 mm probe at 600 MHz, and the NMR data were processed and analyzed using Mestrelab Mnova version 10.

Mass spectrometry (ESI-Q-TOF) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analyses were performed to verify the structure of synthesized HPB. Mass spectrometry showed an m/z value of 532.0745 in a positive ion mode (Figure B,C), which is consistent with the theoretical value of HPB. NMR analysis further confirmed its structural features (Figures D and S1).

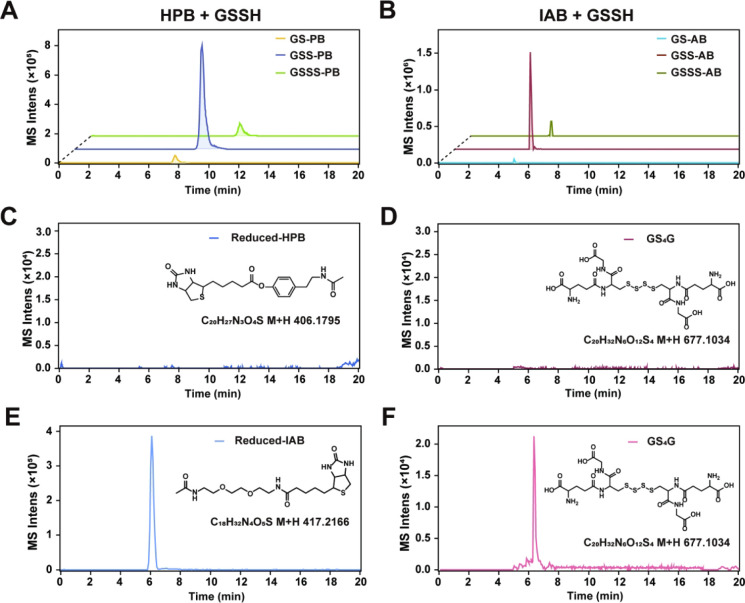

3.2. Alkylation of Glutathione Persulfide by HPB and IAB

We applied glutathione persulfide (GSSH) as a model compound to evaluate the alkylation effect of HPB. First, we analyzed the reaction kinetics of HPB with GSSH. Results showed that the reaction reached more than 95% completion within 10 min at 37 °C (Figure S2A,B). GSSH (0.5 mM) was mixed with redundant HPB (3 mM). The alkylation reaction was conducted at 37 °C for 40 min. The products were analyzed using LC–MS. Results showed that after alkylation, GSS-HPB was the major product (Figures A and S3). Since GSSH was prepared through mixing glutathione (GSH) with elemental sulfur (primarily present as S8) and GSSH is inherently unstable, GSH and GSSSH are inevitably present in the GSSH aqueous solution. Consequently, we also observed GS-HPB and GSSS-HPB products, but both of them were minor components (Figures A and S3).

2.

Identification of reaction products of HPB or IAB with GSSH. (A) Reaction products of HPB (3 mM) with GSSH (0.5 mM). The main product was GSS-PB, and the byproducts were GS-PB and GSSS-PB. (B) Reaction products of IAB (3 mM) with GSSH (0.5 mM). The main product was GSS-AB, and the byproducts were GS-AB and GSSS-AB. (C, E) Identification of potential reduction products from the reaction of HPB with GSSH. (D, F) Identification of reduced IAB and GS4G as byproducts of the IAB-GSSH reaction.

To verify whether the addition of biotin affects the reactivity of the parent compound, we compared HPB with its precursor HPE-IAM. Both reagents showed similar product distributions when reacted with 0.5 mM GSSH under the same conditions (37 °C, 40 min) (Figure S3). In addition, we performed control experiments using IAB (the IAM-derived biotin tag). Similarly, GS-AB was the major product and GSS-AB and GSSS-AB were two minor components (Figures B and S3).

A previous study indicated that halogenated alkylation agents, especially IAM derivatives, can be reduced by low molecular weight polysulfides (reductive dehalogenation), thereby decreasing the alkylation efficacy of such agents. We checked the production of reduced agents after the alkylation reaction. For HPB and HPE-IAM + GSSH reactions, no reduced HPB/HPE-IAM and oxidized GSSH (GS4G) was detected (Figures C,D and S3), whereas quite amount of reduced IAB and GS4G was produced from the IAB + GSSH reaction (Figure E,F). These results indicate that HPB and HPE-IAM show no redox activity toward polysulfides, and HPB retains the alkylation features of HPE-IAM, which is more efficient at alkylation than IAB.

3.3. Alkylation of Synthesized Peptide by HPB and IAB

Previous studies reported that iodinated alkylation agents also can derivatize amino acid residues other than cysteine. These side reactions caused unspecific alkylation. , To evaluate the alkylation specificity of HPB and IAB, we synthesized a 21-amino-acid peptide, designated as P1 (Figure A), which contains a single cysteine residue at position 15 (Cys15). The reaction kinetics of HPB with P1 was analyzed. Results showed that the reaction reached 95% completion within 15 min at 37 °C (Figure S2C,D). Next, P1 was reacted with HPB and IAB for 40 min at 37 °C in the dark, and then, ESI-MS was performed to analyze the molecular weight change of P1. The HPB-reacted P1 displayed a major peak of 3,782.8 Da, corresponding to one molecule HPB alkylation at the Cys15 location (P1–S–HPB), and a minor peak of 4,185.9 Da, corresponding to two molecule HPB alkylation at P1 (Figure A). In contrast, the IAB-reacted P1 exhibited a major peak of 3,793.8 Da, corresponding to one molecule IAB alkylation at the Cys15 location (P1–S–IAB), and three minor peaks of 4,208.1 Da, 4,623.2 Da, and 5,038.4 Da, corresponding to two, three, and four molecule IAB alkylation, respectively (Figure B). These results indicate that HPB causes less unspecific alkylation than does IAB.

3.

HPB exhibits higher specificity toward the cysteine residue of P1 than does IAB. (A) Mass spectrum of P1 (100 μM) after labeled by HPB (3 mM). (B) Mass spectrum of p1 (100 μM) after labeled by IAB (3 mM).

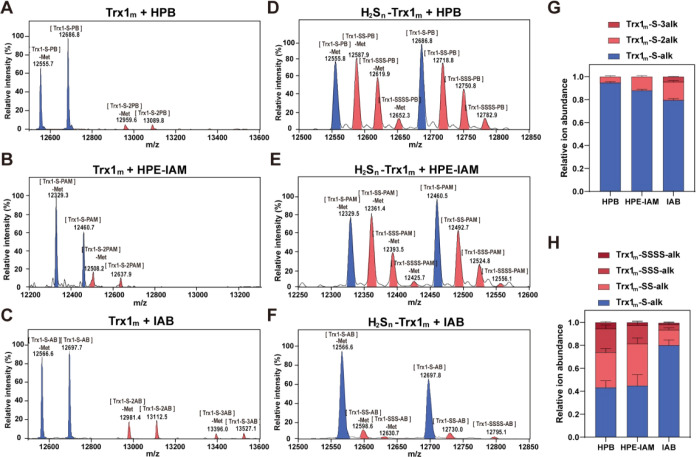

3.4. Alkylation of Thioredoxin 1 by HPB and IAB

Saccharomyces cerevisiae thioredoxin 1 (Trx1) can react with polysulfides to form both disulfide bonds (at Cys30 and Cys33 positions) and persulfidation (at Cys30 residues). , We mutated its Cys33 to serine and keep Cys30 so that only persulfidation can be formed. The mutant (Trx1m) was fused with an N-terminus His-tag and expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3), and it was purified by using a nickel column. First, the reaction kinetics of HPB with the protein Trx1m was analyzed. Results showed that HPB rapidly sealed the thiol group of Trx1m within 10 min at 37 °C (Figure S2E,F). Next, the purified Trx1m (in the reduced form) was reacted with HPB, HPE-IAM, or IAB and then subjected to ESI-MS analysis. HPB-reacted Trx1m showed a major molecular weight of 12 686 Da (+403 Da, corresponding to one molecule HPB alkylation), HPE-IAM-reacted Trx1m showed a major molecular weight of 12 460 Da (+177 Da, corresponding to one molecule HPE-IAM alkylation), and IAB-reacted Trx1m showed a major molecular weight of 12 697 Da (+414 Da, corresponding to one molecule IAB alkylation) (Figure A–C). In addition, a minor peak of 13 089 Da corresponding to two molecules of HPB alkylation was detected and a minor peak of 12 637 Da corresponding to two molecules of HPE-IAM alkylation was detected. Two minor peaks of 13,112 and 13 526 Da corresponding to two and three molecules of IAB alkylation were detected. Since the N-terminal methionine residue is frequently removed during the ESI-MS analysis process, a methionine-less version (Trx1m-Met–1) of each above-mentioned peak was also observed. The one molecule HPB-alkylated protein (Trx1m-S-PB and Trx1m-Met–1-S-PB) accounted for 95.0%, and the one molecule HPE-IAM-alkylated protein (Trx1m-S-PAM and Trx1m-Met–1-S-PAM) accounted for 87.6%. In comparison, the one molecule IAB-alkylated protein (Trx1m-S-AB and Trx1m-Met–1-S-AB) accounted for 79.5% (Figure D). These results were consistent with the results of peptide experiments, confirming that HPB causes more specific alkylation than does IAB.

4.

Different ability of HPB and IAB in preserving the polysulfides group of Trx1m. (A) Full mass spectra of HPB-labeled Trx1m. (B) Full mass spectra of HPE-IAM-labeled Trx1m. (C) Full mass spectra of IAB-labeled Trx1m. (D) Relative proportion of Trx1m with different alkylations (n = 24, error bars represent SD). (E) Full mass spectrum of Trx1m (100 μM) persulfided with H2S n (1 mM) and alkylated with HPB (5 mM). (F) Full mass spectrum of Trx1m (100 μM) persulfided with H2S n (1 mM) and alkylated with HPE-IAM (5 mM). (G) Full mass spectrum of Trx1m (100 μM) persulfided with H2S n (1 mM) and alkylated with IAB (5 mM). (H) Relative proportions of H2S n -treated Trx1m with different alkylations (n = 26, error bars represent SD).

The purified Trx1m was reacted with hydrogen polysulfides (H2S n ) for 30 min to form polysulfidation. The reacted Trx1m was then labeled by HPB, HPE-IAM, or IAB and analyzed by using ESI-MS. Both Trx1m and Trx1m-Met–1 derived peaks were detected. For the HPB-labeled protein, the reduced form (−SH is directly alkylated by HPB), including Trx1m-S-PB and Trx1m-Met–1-S-PB, was the most abundant. Polysulfidation forms, including −SS-PB, −SSS-PB, and −SSSS-PB, were detected, which were generated from HPB alkylating −SSH, −SSSH, and −SSSSH, respectively (Figure E). The amount of polysulfidation forms accounted for 66% of all labeled proteins (Figure H). HPE-IAM exhibited polysulfide chain-stabilizing activity similar to that of HPB, evidenced by −SS-PAM, −SSS-PAM, and −SSSS-PAM accounting for about 55% (Figure F,H). For the IAB-labeled protein, the reduced form (−SH is directly alkylated by IAB), including Trx1m-S-AB and Trx1m-Met–1-S-AB, was the most abundant. Although polysulfidation forms, including −SS-AB, −SSS-AB, and −SSSS-AB, were also detected; totally, they only accounted for 20% of all labeled proteins (Figure G,H). These results indicate that the biotin moiety did not affect the binding of HPB to proteins and HPB is more effective than IAB in tagging and stabilizing polysulfidated proteins.

3.5. Application of HPB in Proteomic Analysis of Polysulfidated Proteins

When performing proteomic analysis of polysulfidated proteins, adding alkylation labels into cell lysis solution and letting the alkylation reaction happen during cell lysis are common practices (workflow 1, Figure A). However, this results in low alkylation efficacy because there are high amounts of low molecular thiols (such as GSH) and polysulfides (such as GSSH) inside cells that can consume or reduce the alkylation reagents. To address this issue, we optimized the protocol. After the cell lysis step, a protein precipitation step was performed to remove low molecular thiols and polysulfides. Precipitated proteins were resolubilized and subsequently alkylated by tagging agents (workflow 2, Figure A).

5.

Application of HPB in proteomic Pr–S n H analysis. (A) Workflows 1 and 2 were used to separate polysulfided proteins from proteome. The difference is Workflow 2 contains a precipitation–resolubilization step to remove low molecular thiols and polysulfides. Workflow 3 was used to separate polysulfided peptides from trypsin-digested proteome. (B) Full mass spectrum of H2S n -reacted Trx1m alkylated with HPB. (C) Full mass spectrum of H2S n -reacted Trx1m, precipitated and resolubilized by acetone and urea, and alkylated with HPB. (D) Relative proportions of alkylated Trx1m; 1 is calculated from (B), 2 is calculated from (C) (n = 2, error bars represent SD). (E) IAB and HPB labeling resulted in different protein yields. Workflow 2 was used. (F) IAB and HPB labeling resulted in different percentage of cysteine-containing peptides. Workflow 3 was used (n = 2, error bars represent SD).

To test whether the precipitation–resolubilization step influences the stability of Pr–S n H and disturbs the alkylation, we passed the HSSH-reacted Trx1m protein through the precipitation–resolubilization step and then alkylated the resolubilized Trx1m with HPB. Compared with HSSH-reacted Trx1m that was directly alkylated by HPB, the precipitated and resolubilized Trx1m showed no decreased but increased contents of Trx-S n -PB (Figure B,C). The Trx-S n -PB accounted for 44.3% in the directly alkylated sample and 55.4% in the resolubilized sample (Figure D), proving that the precipitation–resolubilization step does not disturb the screening of alkylated Pr–S n H. We then applied workflow 2 in proteomic analysis of Pr–S n H. The target proteome was from colon cancer cell HT29. Both HPB and IAB were used. HPB resulted in a higher amount of finally obtained, potentially polysulfidated proteins than did IAB (Figure E).

Considering that unspecific alkylation reactions can happen, the finally obtained proteins may not all be polysulfidated ones. We cannot distinguish polysulfidated proteins from unspecifically alkylated ones when using workflow 2. To address this issue, we changed the workflow again. The labeled proteins were first digested and then passed through streptavidin beads (workflow 3, Figure A). In this case, the finally obtained peptides can be categorized into two groups: cysteine-containing and non-cysteine peptides. The former are from correctly polysulfidated proteins, while the latter are from unspecific alkylation. Using workflow 3, we analyzed the proteome of HT29 with both the HPB and IAB labels. For HPB labeling, the cysteine-containing peptides accounted for 73.3% of all finally obtained peptides. In contrast, IAB labeling yielded 67.4% cysteine-containing peptides (Figure F), indicating that IAB labeling results in more false-positive results.

3.6. Heterocyclic and Aromatic Amino Acids React with Polysulfides and Compromise Protein Polysulfidation Detection

When using HPB to alkylate Trx1m, 95% of Trx1m was specifically labeled on the cysteine residue, and the unspecific alkylation only accounted for 5% (Figure C). However, when using HPB in proteomic analysis, cysteine-containing peptides only accounted for 73.3%. The gap indicates that there are additional factors compromising the specificity of our method. Lawrence et al. reported that N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine can react with hydrogen sulfide to form a thiol group in its benzene ring. This finding led us to hypothesize that amino acids with heterocyclic or phenyl ringsnamely, histidine, proline, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan (Figure A)can similarly react with polysulfides to form thiol groups, thereby disturbing protein polysulfidation detection. A study of Burn et al. also demonstrated that histidine can form a C–S bond in its imidazole ring via the persulfide attack, which proves that our hypothesis is reasonable.

6.

Reaction of heterocyclic and aromatic amino acids with H2S n . (A) Five amino acids with heterocyclic or aromatic rings. (B) LC–MS analysis showed that Phe-SH (the −SH group was blocked by monobromobimane to form Phe-S-mB) was generated from phenylalanine (100 μM) and H2S n (0.5 mM) reaction. (C) Product proportions of phenylalanine reacting with H2S n (n = 2). (D) LC–MS analysis showed that His-SSH (the −SSH group was blocked by monobromobimane to form His-S-S-mB) was generated from histidine (100 μM) and H2S n (0.5 mM) reaction. (E) Product proportions of histidine reacting with H2S n (n = 2). (F) LC–MS analysis showed that Trp-SSH (the −SSH group was blocked by monobromobimane to form Trp-S-S-mB) was generated from tryptophan (100 μM) and H2S n (0.5 mM) reaction. (G) Product proportions of tryptophan reacting with H2S n (n = 2).

To test this hypothesis, we incubated histidine, proline, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan (0.1 mM) with H2S n (0.5 mM) at 37 °C for 1 h and then used 2 mM mBBr to stabilize possibly formed thiol groups. LC–MS/MS analysis was performed to analyze the resulting products. We found that phenylalanine reacted with H2S n to form thiolated-phenylalanine, in which the benzene ring gained the −SH group (Figures B and S2A). Approximately 8.8% of phenylalanine had such modification (Figure C). Histidine and tryptophan did not form thiolated products but formed persulfated-histidine/tryptophanheterocyclic rings carrying −SSH groups (Figures D,F, S2B,C). The percentages of modified histidine and tryptophan were 11.9% and 6.8%, respectively (Figure E,G). Tyrosine and proline showed no thiolated or persulfated derivatives.

In order to further verify that phenylalanine, histidine, and tryptophan can react with polysulfides to generate C–S bonds, we again chose HPE-IAM as an electrophilic trapping agent to enclose the possible thiol groups. Results showed that H2S n was able to react with phenylalanine, histidine, and tryptophan to generate the corresponding thiolated products (Phe-SH, His-SSH, and Trp-SSH), respectively, which were able to be labeled by HPE-IAM (Figure S5A-F). Unlike the mBBr-labeled products, the low peak intensities of these products may reflect the low reactivity of HPE-IAM toward these thiolated products.

To test whether such modifications can happen on peptides, we synthesized a 20-amino-acid peptide that does not contain a cysteine residue (P2). P2 was reacted with H2S n at 37 °C for 1 h, and then was alkylated with HPB or IAB. LC–MS analysis was performed to check the molecular weight change of P2. The control was unreacted P2 that was directly alkylated by HPB or IAB. Compared with the unreacted control, H2S n -reacted P2 showed more peaks with additional alkylation in its MS spectrum (Figure ). In addition, IAB resulted in more such additional peaks than HPB. Although pinpointing the exact location of such additional alkylation was challenging, these results clearly indicate that polysulfides can modify amino acids other than cysteine. Such modifications can be targeted by HPB and IAB, which then disturb protein polysulfidation detection.

7.

Alkylation of peptide 2 before and after reaction with H2S n . (A) Mass spectrum of P2 after labeling with HPB. (B) Mass spectrum of P2 after labeling with IAB. (C) Mass spectrum of P2, persulfided with H2S n (1 mM) and then alkylated with HPB (5 mM). (D) Mass spectrum of P2 (100 μM), persulfided with H2S n (1 mM) and then alkylated with IAB (5 mM).

4. Discussion

In this study, we successfully synthesized a polysulfidation detection tag HPB through a four-step process. This tag is HPE-IAM-derived and contains biotin. When reacting with GSSH, HPB showed only alkylation activity. No production of the reduced HPB was detected. In contrast, IAB showed apparent redox activity toward GSSH, evidenced by the production of a reduced IAB tag. When reacting with peptides, HPB showed fewer off-target alkylation positions compared with IAB. Finally, when using HPB and IAB to label and screen polysulfidated proteins from the HT29 cell proteome, HPB led to fewer false-positive peptides than IAB. Therefore, HPB exhibits significant advantages over the commonly used alkylating reagent IAB, particularly in terms of reaction specificity and retention of polysulfide chains.

Due to the complexity of intracellular biological processes, the high reactivity of the polysulfide group (−S n H) and its similarity to thiols (−SH), developing suitable reagents for polysulfidation analysis, remain a considerable challenge. Zivanovic et al. used NBF–Cl and DCP-Bio1 to react with −S n H. While this approach is highly specific and avoids nonspecific binding associated with IAB, NBF–Cl also reacts with −NH2, sulfenic acid (−SOH), and other functional groups, potentially leading to high background signals. Therefore, using appropriate reagent doses is critical to avoid such issues. The “low-pH” method proposed by Fu et al. enhanced the reactivity of RSSH by lowering the pH (pH < 5), which improves the alkylation reagent’s specificity. However, this method employs an IAM-based tag (iodo-N-(prop-2-yn-1-yl) acetamide, IPM), and further tests are needed to assess the ability of IPM in stabilizing the polysulfide chain.

The degree of polysulfidation detected by different methods varies significantly, making it difficult to accurately determine the extent of this modification. For instance, Fu et al. and Longen et al. used QTRP (low-pH quantitative thiol reactivity profiling) and QPerS-SID (Quantitative Persulfide Site Identification) methods, respectively, to detect protein polysulfidations in the same cell line but found only a 0.05% overlap in identified proteins. Previous studies by Yang and Attygalle and Müller and Winter indicate that IAM not only reacts with cysteine but also with lysine, methionine, and peptide amines. In addition, chemical artifacts also appeared when using it to detect other post-translational modifications. Compared with IAB, HPB showed obviously lower unspecific alkylation activity and, hence, less off-target alkylation positions. This should be a significant advantage when using it to screen polysulfidated proteins from cell proteomes.

While HPB shows significant improvements over IAB in terms of reaction specificity and preservation of polysulfide chains, it currently has poor water solubility. We solubilized it in organic solvents, such as methanol, acetone, and DMSO, to make an HPB solution before use. The organic solution may decrease its alkylation efficacy. Future work could focus on enhancing its water solubility by adding phosphate groups or oxygen atoms to its structure, thereby further expanding its applicability. In addition, the unspecific alkylation is obviously decreased but is not totally avoided. Nonetheless, the current version of HPB already showed great potential in protein polysulfidation analysis, and its further optimization is highly expected.

In addition, we observed that polysulfides can modify histidine, phenylalanine, and tyrosine by introducing the −SH or −SSH group into their heterocyclic/phenyl rings. Given that polysulfides are highly nucleophilic and these amino acids’ heterocyclic or phenyl rings are electrophilic, polysulfides may attack the aromatic ring under specific conditions, forming new C–S bonds or persulfide linkages. This behavior is akin to how N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine reacts with hydrogen sulfide to form a thiol group in its benzene ring. These findings help explain why the proportion of cysteine-containing peptides did not exceed 90% in our proteomic analysis, suggesting that polysulfides may have broader reactivity than the current understanding.

5. Conclusion

Understanding the complexities of protein persulfidation and developing tools to detect such modifications are crucial for elucidating their role in cellular processes. The development of HPB, a novel biotinylated reagent, offers a significant advancement in the detection of persulfidated proteins, improving upon traditional reagents such as IAB in terms of specificity and retention of polysulfide chains. This work highlights the challenges of selectively labeling persulfidated proteins within the intricate landscape of cellular proteomes, where off-target reactions and chemical artifacts can obscure true modifications. Moreover, the identification of persulfide reactivity with noncysteine amino acids, such as histidine and phenylalanine, opens new avenues for exploring polysulfide-mediated post-translational modifications beyond cysteine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Guannan Lin, Jingyao Qu, Jing Zhu, and Yuyu Guo from the Analysis and Testing Center of the State Key Laboratory for Microbial Technology (Shandong University) for assistance with the LC–MS/MS analysis.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.analchem.5c00712.

1H NMR spectrum of HPB (Figure S1); the kinetic profile of the reaction of HPB with GSSH, P1, and Trx1m (Figure S2); identification of reaction products of HPE-IAM with GSSH (Figure S3); mass spectra of Phe-S-mB, His-SS-mB, and Trp-SS-mB that were produced from the Phe/His/Trp + H2S n reaction (Figure S4); and identification of heterocyclic and aromatic amino acid reaction products with H2S n (Figure S5) (PDF)

H.L.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision. L.X.: conceptualization, supervision. Y.X and X.Z.: investigation. Q.W. and L.D.: methodology. X.Z.: resources and data curation. Y.X.: validation. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3401301) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32300076).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Fukuto J. M.. The Biological/Physiological Utility of Hydropersulfides (RSSH) and Related Species: What Is Old Is New Again. Antioxid Redox Sign. 2022;36(4–6):244–255. doi: 10.1089/ars.2021.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl S., Xian M.. Recent development of polysulfides: Chemistry and biological applications. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2023;75:102325. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2023.102325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedroc D. P., Antelo G. T., Fakhoury J. N., Capdevila D. A.. Sensing and regulation of reactive sulfur species (RSS) in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2023;76:102358. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2023.102358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange M., Olzmann J. A.. Hydropersulfides are endogenous antioxidants that inhibit ferroptosis. Cell Chem. Biol. 2022;29(12):1661–1663. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2022.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. J., Khodade V. S., Chauvin J. P. R., Rodriguez D., Toscano J. P., Pratt D. A.. Hydropersulfides Inhibit Lipid Peroxidation and Protect Cells from Ferroptosis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144(34):15825–15837. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c06804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barayeu U., Schilling D., Eid M., da Silva T. N. X., Schlicker L., Mitreska N., Zapp C., Gräter F., Miller A. K., Kappl R., Schulze A.. et al. Hydropersulfides inhibit lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis by scavenging radicals. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2023;19(1):28–37. doi: 10.1038/s41589-022-01145-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolluru G. K., Shen X. G., Kevil C. G.. Reactive Sulfur Species: A New Redox Player in Cardiovascular Pathophysiology. Arterioscl. Throm. Vas. 2020;40(4):874–884. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.314084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaike T., Ida T., Wei F. Y., Nishida M., Kumagai Y., Alam M. M., Ihara H., Sawa T., Matsunaga T., Kasamatsu S.. et al. Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase governs cysteine polysulfidation and mitochondrial bioenergetics. Nat. Commun. 2017;8(1):1177. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01311-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. J., Liu H. W., Chen Z. G., Zhao R., Wang Q. D., Ran M. X., Xia Y. Z., Hu X., Liu J. H., Xian M.. et al. Using resonance synchronous spectroscopy to characterize the reactivity and electrophilicity of biologically relevant sulfane sulfur. Redox Biol. 2019;24:101179. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H. J., Xiong S. P., Cao X., Cao L., Zhu M. Y., Wu Z. Y., Bian J. S.. Polysulfide-mediated sulfhydration of SIRT1 prevents diabetic nephropathy by suppressing phosphorylation and acetylation of p65 NF-κB and STAT3. Redox Biol. 2021;38:101813. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji D. Y., Luo C. H., Liu J., Cao Y., Wu J. X., Yan W. J., Xue K., Chai J. Y., Zhu X. Y., Wu Y.. et al. Insufficient S-Sulfhydration of Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase Contributes to the Progress of Hyperhomocysteinemia. Antioxid Redox Sign. 2022;36(1–3):1–14. doi: 10.1089/ars.2021.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S., Chakraborty P. K., Xiong X. H., Dwivedi S. K. D., Mustafi S. B., Leigh N. R., Ramchandran R., Mukherjee P., Bhattacharya R.. Cystathionine β-synthase regulates endothelial function protein S-sulfhydration. Faseb J. 2016;30(1):441–456. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-278648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z., Altaf N., Li C., Chen M., Pan L. H., Wang D., Xie L. P., Zheng Y., Fu H. L., Han Y.. et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates oxidative stress-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation via S-sulfhydrating c-Jun at Cys269 in macrophages. BBA-Mol. Basis. Dis. 2018;1864(9):2890–2900. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa A. K., Sikka G., Gazi S. K., Steppan J., Jung S. M., Bhunia A. K., Barodka V. M., Gazi F. K., Barrow R. K., Wang R.. et al. Hydrogen Sulfide as Endothelium-Derived Hyperpolarizing Factor Sulfhydrates Potassium Channels. Circ. Res. 2011;109(11):1259–1268. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.240242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha J., Xu Y., Kawano T., Hendon T., Baki L., Garai S., Papapetropoulos A., Thakur G. A., Plant L. D., Logothetis D. E.. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits Kir2 and Kir3 channels by decreasing sensitivity to the phospholipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP) J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293(10):3546–3561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S. S., Kong C. Y., Ye D. Y., Liu X. G., Wang Y., Meng G. L., Han Y., Xie L. P., Ji Y.. Protein Persulfidation: Recent Progress and Future Directions. Antioxid Redox Sign. 2023;39(13–15):829–852. doi: 10.1089/ars.2022.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignane T., Filipovic M. R.. Emerging Chemical Biology of Protein Persulfidation. Antioxid Redox Sign. 2023;39(1–3):19–39. doi: 10.1089/ars.2023.0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa A. K., Gadalla M. M., Sen N., Kim S., Mu W. T., Gazi S. K., Barrow R. K., Yang G. D., Wang R., Snyder S. H.. H2S Signals Through Protein S-Sulfhydration. Sci. Signaling. 2009;2(96):72. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J., Carroll K. S.. Persulfide Reactivity in the Detection of Protein S-Sulfhydration. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8(6):1110–1116. doi: 10.1021/cb4001052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. H., Macinkovic I., Devarie-Baez N. O., Pan J., Park C. M., Carroll K. S., Filipovic M. R., Xian M.. Detection of Protein S-Sulfhydration by a Tag-Switch Technique. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53(2):575–581. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivanovic J., Kouroussis E., Kohl J. B., Adhikari B., Bursac B., Schott-Roux S., Petrovic D., Miljkovic J. L., Thomas-Lopez D., Jung Y.. et al. Selective Persulfide Detection Reveals Evolutionarily Conserved Antiaging Effects of S-Sulfhydration. Cell Metab. 2019;30(6):1152–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdándi V., Ida T., Sutton T. R., Bianco C., Ditrói T., Koster G., Henthorn H. A., Minnion M., Toscano J. P., van der Vliet A.. et al. Speciation of reactive sulfur species and their reactions with alkylating agents: do we have any clue about what is present inside the cell? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019;176(4):646–670. doi: 10.1111/bph.14394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X.-H., Krokowski D., Guan B.-J., Bederman I., Majumder M., Parisien M., Diatchenko L., Kabil O., Willard B., Banerjee R.. et al. Quantitative H2S-mediated protein sulfhydration reveals metabolic reprogramming during the integrated stress response. Elife. 2015;4:e10067. doi: 10.7554/eLife.10067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dóka E., Pader I., Bíró A., Johansson K., Cheng Q., Ballagó K., Prigge J. R., Pastor-Flores D., Dick T. P., Schmidt E. E.. et al. A novel persulfide detection method reveals protein persulfide- and polysulfide-reducing functions of thioredoxin and glutathione systems. Sci. Adv. 2016;2(1):e1500968. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling D., Barayeu U., Steimbach R. R., Talwar D., Miller A. K., Dick T. P.. Commonly Used Alkylating Agents Limit Persulfide Detection by Converting Protein Persulfides into Thioethers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022;61(30):e202203684. doi: 10.1002/anie.202203684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling D., Ditroi T., Barayeu U., Juranyi E. P., Nagy P., Dick T. P.. The influence of alkylating agents on sulfur-sulfur bonds in per- and polysulfides. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2023;76:102368. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2023.102368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. H., Xin Y. P., Wang Q. D., Xia Y. Z., Xun L. Y., Liu H. W.. A Caveat When Using Alkyl Halides as Tagging Agents to Detect/Quantify Reactive Sulfur Species. Antioxidants-Basel. 2022;11(8):1583. doi: 10.3390/antiox11081583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid H. A., Tanaka A., Ida T., Nishimura A., Matsunaga T., Fujii S., Morita M., Sawa T., Fukuto J. M., Nagy P.. et al. Polysulfide stabilization by tyrosine and hydroxyphenyl-containing derivatives that is important for a reactive sulfur metabolomics analysis. Redox Biol. 2019;21:101096. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser J. M., Robertson L. A., VanVerseveld H. W., Kuenen J. G.. Sulfur production by obligately chemolithoautotrophic Thiobacillus species. Appl. Environ. Microb. 1997;63(6):2300–2305. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2300-2305.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamyshny A., Borkenstein C. G., Ferdelman T. G.. Protocol for Quantitative Detection of Elemental Sulfur and Polysulfide Zero-Valent Sulfur Distribution in Natural Aquatic Samples. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 2009;33(3):415–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-908X.2009.00907.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luebke J. L., Shen J. C., Bruce K. E., Kehl-Fie T. E., Peng H., Skaar E. P., Giedroc D. P.. The CsoR-like sulfurtransferase repressor (CstR) is a persulfide sensor in Staphylococcus aureus . Mol. Microbiol. 2014;94(6):1343–1360. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. H., Attygalle A. B.. LC/MS characterization of undesired products formed during iodoacetamide derivatization of sulfhydryl groups of peptides. J. Mass Spectrom. 2007;42(2):233–243. doi: 10.1002/jms.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller T., Winter D.. Systematic Evaluation of Protein Reduction and Alkylation Reveals Massive Unspecific Side Effects by Iodine-containing Reagents. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2017;16(7):1173–1187. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M116.064048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. G., Parrott A. M., Fu C. X., Liu T., Marino S. M., Gladyshev V. N., Jain M. R., Baykal A. T., Li Q., Oka S.. et al. Thioredoxin 1-Mediated Post-Translational Modifications: Reduction, Transnitrosylation, Denitrosylation, and Related Proteomics Methodologies. Antioxid Redox Sign. 2011;15(9):2565–2604. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence N. S., Davis J., Jiang L., Jones T. G. J., Davis S. N., Compton R. G.. Selective determination of thiols: a novel electroanalytical approach. Analyst. 2000;125(4):661–663. doi: 10.1039/b000985g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burn R., Misson L., Meury M., Seebeck F. P.. Anaerobic Origin of Ergothioneine. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017;56(41):12508–12511. doi: 10.1002/anie.201705932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L., Liu K. K., He J. Y., Tian C. P., Yu X. B., Yang J.. Direct Proteomic Mapping of Cysteine Persulfidation. Antioxid Redox Sign. 2020;33(15):1061–1076. doi: 10.1089/ars.2019.7777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longen S., Richter F., Köhler Y., Wittig I., Beck K.-F., Pfeilschifter J.. Quantitative Persulfide Site Identification (qPerS-SID) Reveals Protein Targets of H2S Releasing Donors in Mammalian Cells. Sci. Rep. 2016;6(1):29808. doi: 10.1038/srep29808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.