Abstract

Background and Aims

Constipation in patients with cystic fibrosis (PwCF) is a debilitating symptom and, in its most severe forms, is associated with distal intestinal obstruction syndrome. This study aims to characterize the relationship between constipation during hospitalization and the symptoms, complications, and associated health-care costs of constipation in the National Inpatient Sample database.

Methods

National Inpatient Sample was queried for discharges in the general population and PwCF from the years 2015–2019. Using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes, hospitalized PwCF were matched with the general population on the Charlson comorbidity index, markers of hospitalization severity, and demographics. Subsequently, both were split into 2 cohorts: one with comorbid constipation and one without. Study outcomes were adjusted for gastrointestinal comorbidities, age, sex, and indication for admission.

Results

Of 135,860 discharges, constipation was present in 14.0% in PwCF and 5.6% in the general population with average total charges of $104,270 and length of stay (LOS) of 8.8 days. Constipation was independently associated with increased LOS (1.22 days, standard error [SE] 0.21) and total charges ($14,280, SE $12,308) among PwCF, despite undergoing a similar number of endoscopic procedures (−0.02 SE 0.06). These findings were unchanged on subgroup analysis for sex and indication for hospitalization. Subgroup analysis showed a persistent association of higher costs with constipation in those with pancreatic insufficiency but not those with pancreatic sufficiency ($22,053 vs $493) despite a similar LOS.

Conclusion

Comorbid constipation in hospitalized PwCF was independently associated with increased LOS and costs. The association worsened in those with pancreatic insufficiency.

Keywords: Cystic Fibrosis, Constipation, Distal Intestinal Obstruction Syndrome, Gender, Pancreatic Insufficiency

Introduction

In patients with cystic fibrosis (PwCF), a systematic review in 2020 using data from 8 observational studies found between 10% and 57% reported constipation during their disease course.1 Stool-specific questionnaire administered during GALAXY trial highlighted 15% of PwCF self-reported constipation, and 11% of PwCF reported Bristol Stool Scale scores of 1–2.2 Risk factors for constipation include a history of meconium ileus, older age, lower total fat absorption, and female sex.3, 4, 2

Constipation increased cost and length of stay (LOS) in hospitalized persons without cystic fibrosis.5 Furthermore, it has increased mortality in patients on mechanical ventilation in intensive care units and has been associated with complications such as bowel obstruction and fecal impaction.6 There remains a paucity of literature on the impact of constipation and risk factors for constipation, such as pancreatic insufficiency (PI) and distal intestinal obstruction syndrome (DIOS, thought to be an interrelated condition with CF-related constipation at its most severe when constipation is not managed effectively) in PwCF on hospitalizations and the role of CF-specific gastrointestinal complications.

To address this research gap, this study aimed to characterize the relationship between constipation and its symptoms, complications, and associated health-care costs. A subgroup analysis was performed to identify risk factors impacting health-care costs. The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) data set was utilized to compare LOS, cost, and number/type of procedures between PwCF with constipation and PwCF without constipation, as well as among the general population with constipation and the general population without constipation.

Materials and Methods

We designed a cross-sectional analysis of hospitalizations of PwCF using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project-NIS data set. Hospitalizations were eligible for inclusion if the patient was older than 18 years of age. NIS was queried for discharges of PwCF from the years 2015–2019. We used previously validated International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes of E84-84.9 for the identification of PwCF in NIS.7,8 Constipation was defined as K59.00, 59.01, 59.03, 59.04, and 59.09.9 A full list of ICD-10 codes used can be found in the Supplemental Materials. NIS weighting procedures are well documented.

PwCF and the general population were matched on income quartile, insurance, race, sepsis, vasopressor use, lung transplant, liver transplant, mechanical ventilation, and Charlson comorbidity index. Use of highly effective modulator therapy (HEMT) was not matched due to smaller proportion of HEMT-eligible patients compared to a post-2019 cohort when elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor was available for the vast majority of PwCF. Propensity score matching was performed employing a nearest neighbor method. Groups were considered balanced when the standard difference between groups was <0.1, which was true for all variables used for matching. Patients were stratified based on documented CF and constipation resulting in a comparison of 4 cohorts (Table 1). Continuous variables were tested using analysis of variance, and categorical variables were tested using Pearson’s chi-square test.

Table 1.

Matched Cohorts of PwCF With and Without Constipation and the General Population With and Without Constipation

| Matching variables | Matched cohorts |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PwCF without constipation |

PwCF with constipation |

General population without constipation |

General population with constipation |

|

| N = 70,895 | N = 11,430 | N = 77,910 | N = 4390 | |

| Race (White) | 60,515 (85.4%) | 9825 (86.0%) | 66,650 (85.5%) | 3730 (85.0%) |

| Median Income lowest Quartiles ($1–$5399) | 35,790 (50.5%) | 5385 (47.1%) | 38,935 (49.9%) | 2240 (51.0%) |

| Primary expected payer (Public) | 37,495 (52.8%) | 6185 (54.1%) | 41,045 (52.7%) | 2600 (59.3%) |

| APR Risk of Mortality (mod– extreme) | 49,930 (70.4%) | 8850 (77.5%) | 34,695 (44.5%) | 2465 (56.1%) |

| APR Severity (major–extreme loss of function) | 48,890 (69.0%) | 8760 (76.6%) | 25,695 (33.0%) | 1910 (43.5%) |

| Sepsis | 7025 (9.9%) | 985 (8.6%) | 7435 (9.5%) | 550 (12.5%) |

| Vasopressor use | 485 (0.7%) | 65 (0.6%) | 510 (0.7%) | 35 (0.8%) |

| Lung Transplant | 4305 (6.1%) | 510 (4.5%) | 4545 (5.8%) | 270 (6.2%) |

| Liver Transplant | 1685 (2.4%) | 270 (2.4%) | 1865 (2.4%) | 95 (2.2%) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 2180 (3.1%) | 225 (2.0%) | 2255 (2.9%) | 135 (3.1%) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 2.6 (1.5) | 2.5 (1.4) | 2.6 (1.5%) | 2.8 (1.8%) |

| Covariates | ||||

| Sex (Female) | 37,680 (53.1%) | 6895 (60.3%) | 39,625 (50.9%) | 2495 (56.8%) |

| Age | 33.0 (13.5) | 32.5 (12.9) | 56.7 (13.1) | 57.5 (14.2) |

| Pancreatic Insufficiency | 37,390 (52.7%) | 7420 (64.9%) | 1055 (1.4%) | 75 (1.7%) |

| Osteoporosis | 4300 (6.1%) | 1120 (9.8%) | 2235 (2.9%) | 200 (4.6%) |

| Obesity | 1765 (2.5%) | 280 (2.5%) | 15,010 (19.3%) | 790 (18.0%) |

| C. difficile colitis | 1360 (1.9%) | 205 (1.8%) | 1085 (1.4%) | 25 (0.6%) |

| Reason For Admission (pulmonary) | 17,900 (25.2%) | 2930 (25.6%) | 6720 (8.6%) | 425 (9.7%) |

Covariates were not used for matching but were adjusted for multivariate analysis. Standard deviations are depicted in parentheses next to mean values.

We used multivariate linear and logistic regression to evaluate study outcomes, adjusting for gastrointestinal comorbidities, age, and sex. The primary analysis was adjusted for sex, age, PI, osteoporosis, obesity, C. difficile-associated colitis, hospital location, and hospital bed capacity. The primary outcome of interest was the LOS. Secondary outcomes of interest included total cost of hospitalization and procedures performed while hospitalized with particular interest in endoscopy, surgeries, and mortality. When indicated, Firth’s bias correction was utilized for multivariate logistic regression for rare outcomes. Lastly, subgroup analyses were performed on subclassification of indication for hospitalization, sex, and pancreatic sufficiency (PS) status. P-values < .05 were considered statistically significant. Data analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R version 4.3.1.

Results

In the general population, there were 174,640,345 discharges from hospitals in NIS between 2015 and 2019, with an average LOS of 4.8 days (standard deviation [SD] 6.4) and average total charges of $54,958 (SD $91,335). Within discharges of adults, 5.6% included patients with comorbid constipation. Of admissions with comorbid constipation, 56.3% were females, the mean age was 65.1 years old, and 0.9% had PI. In comparison, of the general population without constipation, 57.7% were females, the mean age was 57.8 years old, and 1.5% had PI.

In PwCF, there were 135,860 discharges from hospitals in NIS between 2015 and 2019 with an average LOS of 8.8 days (SD 9.3), and the average total charges were $104,270 (SD $206,296). Fourteen percent of discharges included PwCF with comorbid constipation. Of admissions with comorbid constipation, 60.6% were females, mean age was 32.5%, and 64.4% had PI. In comparison, of PwCF without constipation, 53.2% were females, the mean age was 33.1%, and 52.4% had PI.

After matching the general population and PwCF, demographic features were similar between the general population and PwCF. After splitting PwCF into a cohort with and without constipation, PwCF with constipation had numerically higher rates of PI (60.3% vs 52.7%), osteoporosis (9.8% vs 6.1%), and female sex (60.3% vs 53.1%). In PwCF, constipation was independently associated with increased odds of having ICD-10 code for abdominal pain (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.83, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.64–2.04) and nausea/vomiting (aOR 2.18, 95% CI: 2.00–2.39) as well as increased odds of codes for distal intestinal obstructive syndrome (aOR 1.85, 95% CI: 1.76–1.94) and urinary retention (aOR 2.52, 95% CI: 2.06–3.08) (Table 2). Constipation was also associated with lower odds of death (aOR 0.56, 95% CI: 0.45–0.70) and bowel obstruction (aOR 0.69, 95% CI 0.61–0.78).

Table 2.

Multivariate Linear Regression of Outcomes in PwCF and Constipation

| PwCF |

General population |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR or estimate | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P-value | OR or estimate | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P-value | |

| Abdominal Pain | 1.79 | 1.61 | 2.00 | <.01 | 2.08 | 1.75 | 2.48 | <.01 |

| Nausea or Vomiting | 2.18 | 2.00 | 2.39 | <.01 | 1.76 | 1.53 | 2.04 | <.01 |

| Urinary Retention | 2.52 | 2.06 | 3.08 | <.01 | 3.13 | 2.74 | 3.59 | <.01 |

| Bowel Obstruction | 0.69 | 0.61 | 0.78 | <.01 | 0.924 | 0.779 | 1.10 | .36 |

| Distal Intestinal Obstruction Syndrome | 1.85 | 1.76 | 1.94 | <.01 | ||||

| Peritonitis | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.46 | <.01 | 1.76 | 1.23 | 2.52 | <.01 |

| Death | 0.56 | 0.45 | 0.70 | <.01 | 1.05 | 0.80 | 1.36 | .75 |

| Malnutrition | 1.15 | 1.10 | 1.20 | <.01 | 1.90 | 1.71 | 2.12 | <.01 |

| Number of Proceduresa | −0.02 | −0.13 | 0.09 | .71 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.46 | <.01 |

| Procedures of Interesta | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.01 | <.01 | 0.002 | −0.03 | 0.03 | .89 |

| Length of Stay (d) | 1.22 | 1.01 | 1.43 | <.01 | 2.49 | 1.94 | 3.04 | <.01 |

| Total Charges (dollars) | 14,280 | 9538 | 19,021 | <.01 | 10,129 | 5438 | 14,820 | .03 |

Adjusted odds ratios and estimates from multivariate modeling in matched cohorts (matched on income quartile, insurance, race, sepsis, vasopressor use, lung transplant, liver transplant, mechanical ventilation, and CCI) and adjusting for sex, age, pancreatic insufficiency, osteoporosis, obesity, C. difficile colitis, hospital location, and hospital bed size.

Procedures of interest included endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, endoscopy, and colonoscopy.

Constipation was independently associated with increased LOS (1.22 days, standard error [SE] 0.21) and total charges ($14,280 SE $12,308), despite undergoing a similar number of endoscopic procedures (−0.02 SE 0.06). Increased total charges and LOS were both associated with male sex, decreased age, PI, chronic sinusitis, C. difficile colitis, urban setting, larger hospital, and teaching hospital (P < .01), while gastroesophageal reflux, osteoporosis, and overweight/obesity were not.

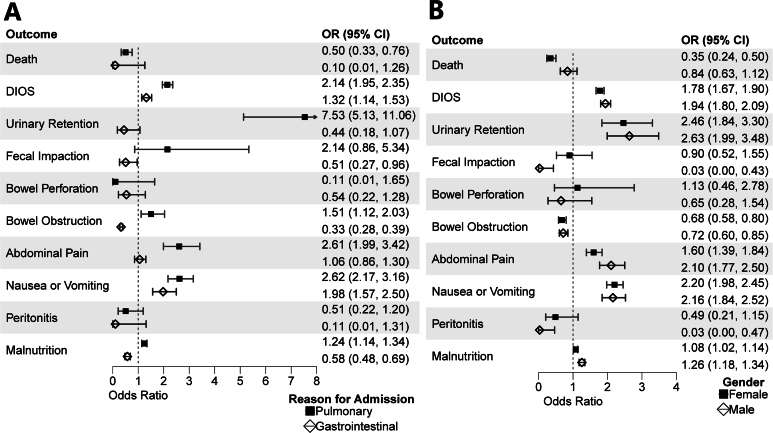

In the subgroup analysis by categorization of ICD-10 coded reason for admission, the relationship between constipation and increased costs and LOS persisted among PwCF admitted for pulmonary indications ($19,659 SE $7324 and 1.80 days SE 0.37) but did not among those admitted for gastrointestinal-related indications (−$4623 SE $8956 and −0.18 days SE 0.69) (Table 3). Subgroup analysis by sex showed increases in cost and LOS for male PwCF ($17,928 SE $7022 and 1.60 days SE 0.32) and an increase in LOS but only a trend toward increased cost for female PwCF ($11,811 SE $6441 and 0.96 days SE 0.27). Lastly, subgroup analysis by PS status revealed increases in cost and LOS for PwCF with PI ($22,053 SE $4407 and 1.10 days SE 0.23) and similarly increased LOS but complete amelioration of the cost difference for PwCF without PI ($493 SE $9766 and 1.39 days SE 0.39). aOR comparison between other outcomes can be visualized in (Figures 1A and B and 2A).

Table 3.

Multivariate Linear Regression of Subgroups of PwCF and Constipation

| Indication for admission |

Sex |

Pancreatic |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI (n = 4255) | Pulmonary (n = 20,830) | Other (n = 57,240) | Male (n = 37,750) | Female (n = 44,575) | Insufficient (n = 44,810) | Sufficient (n = 37,515) | |

| OR or estimate (95% CI or SE, P-value) | |||||||

| Length of Stay (d) | −0.18 (0.67) | 1.8 (0.37) | 1.16 (0.27) | 1.60 (0.32) | 0.96 (0.27) | 1.10 (0.23) | 1.39 (0.39) |

| Total Hospital Charges | −$4623 ($8956) | $19,659 ($7323) | $14,162 ($6357) | $17,929 ($7022) | $11,811 ($6441) | $22,053 ($4407) | $493 ($9766) |

| Abdominal Pain | 1.06 (0.86–1.3) | 2.61 (1.9–3.4) | 2.28 (1.98–2.64) | 2.10 (1.8–2.5) | 1.60 (1.4–1.8) | 1.42 (1.2–1.6) | 2.57 (2.2–3.0) |

| Nausea or Vomiting | 1.98 (1.57–2.5)a | 2.62 (2.2–3.2) | 2.13 (1.9–2.4) | 2.16 (1.8–2.5) | 2.20 (2.0–2.5) | 2.02 (1.8–2.3) | 2.55 (2.2–2.9) |

| Urinary Retention | 0.44 (0.18–1.07)a | 7.5 (5.1–11.1)a | 2.0 (1.6–2.6) | 2.64 (2.0–3.5) | 2.46 (1.8–3.3) | 1.78 (1.3–2.5) | 3.35 (2.6–4.3) |

| Bowel Obstruction | 0.33 (0.28–0.39) | 1.51 (1.1–2.0) | 1.35 (1.1–1.6) | 0.72 (0.6–0.9) | 0.68 (0.6–0.8) | 0.84 (0.7–1.0) | 0.49 (0.4–0.6) |

| Distal Intestinal Obstruction Syndrome | 1.32 (1.14–1.53) | 2.1 (2.0–11.1) | 1.83 (1.7–1.9) | 1.94 (1.8–2.1) | 1.78 (1.7–1.9) | 1.75 (1.6–1.9) | 2.04 (1.9–2.2) |

| Peritonitis | 0.11 (0.01–1.31)a | 0.51 (0.2–1.2)a | 0.04 (0.0–0.6)a | 0.03 (0.0–0.5)a | 0.49 (0.2–1.1)a | 0.34 (0.1–0.8)a | 0.04 (0.0–0.6)a |

| Death | 0.1 (0.01–1.26)a | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 0.62 (0.5–0.8) | 0.84 (0.6–1.1) | 0.35 (0.2–0.5) | 0.51 (0.36–0.72) | 0.62 (0.46–0.82) |

| Malnutrition | 0.58 (0.48–0.69) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 1.19 (1.1–1.3) | 1.26 (1.2–1.3) | 1.08 (1.0–1.1) | 1.07 (1.0–1.1) | 1.34 (1.2–1.4) |

| Procedures of interest | −0.05 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.04 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.03 (0.01) | −0.03 (0.02) |

Adjusted odds ratios and estimates from multivariate modeling in matched cohorts (matched on income quartile, insurance, race, sepsis, vasopressor use, lung transplant, liver transplant, mechanical ventilation, and Charlson comorbidity index) and adjusting for sex, age, pancreatic insufficiency, osteoporosis, obesity, C. difficile colitis, hospital location, and hospital bed size.

Firth bias correction was used for rare outcomes when quasi-complete separation of data points occurred.

Figure 1.

(A) Forest plots among PwCF comparing aOR of the association of constipation with outcomes stratified by primary ICD-10 code categorized by organ system. (B) Forest plots stratified by sex.

Figure 2.

(A) Forest plots stratified by pancreatic sufficiency. (B) Forest plot comparing aOR of the association of constipation with hospitalized general population and PwCF.

Among the general population, constipation was also associated with longer LOS (2.49 days, SE 0.28) and mean total charges ($10,129, SE $4691). Constipation was associated with an increased number of procedures (0.29 SE 0.09), increased odds of having an ICD-10 code for nausea or vomiting (aOR 1.78, 95% CI 1.54–2.05), malnutrition (aOR 1.90, 95% CI 1.71–2.12), and urinary retention (aOR 3.12, 95% CI 2.73–3.58). Mortality was similar between patients with and without constipation (aOR 1.04, 95% CI 0.80–1.36) in the general population. Though no statistical comparisons were made between PwCF and the general population, visual comparison can be seen in Figure 2B.

Discussion

Here, we find that in the general population, the presence of a constipation diagnosis on admission or during hospitalization is associated with longer LOS and increased hospital total charges. To understand these results, it is important to acknowledge the composition of NIS data. First, the unit of comparison is individual hospitalizations—a patient hospitalized multiple times may be overrepresented in either constipation or nonconstipation groups. Second, the presence of constipation can indicate either presence on admission diagnosis or an acute finding during hospitalization.10 Keeping these limitations in mind, we feel our data overwhelmingly suggests an association between the presence of constipation and longer hospital LOS and higher costs in both the general population and PwCF.

These findings are consistent with prior work looking specifically at patients requiring mechanical ventilation on admission, which found increased LOS and total hospital costs in those with comorbid constipation.6 Notably, Ali et al also found decreased mortality in hospitalizations with a constipation diagnosis.6 This effect was seen in our initial models (not matched with the PwCF) in the general population (aOR 0.712, CI: 0.708–0.716) but was not seen after matching the general population to PwCF. In contrast to the general population, the presence of constipation diagnosis in hospitalization was associated with decreased mortality in PwCF in both initial models and after matching.

In PwCF, constipation diagnosis (with and without DIOS) was associated with longer LOS and higher total costs. This was notably adjusted for sex, age, PS status, and indication for admission. These findings were similar in significance and magnitude to the findings in the general population. While no formal statistical comparisons between PwCF and the general population were made, this study may suggest that these effects are present with or without comorbid CF diagnosis.

A constipation ICD-10 code was present in 14.0% of discharges of PwCF. It is unclear how this relates to the true prevalence of constipation in the population of PwCF. Estimates across observational studies range from 10% to 57%, depending on the definition of constipation and the populations studied.1 Even within similar populations, defining constipation can be challenging—in the GALAXY study, 41.3% of patients were on medications for constipation, but only 10.5% self-reported constipation, and 11.5% self-reported alternating diarrhea and constipation.3 Thus, it is difficult to ascertain if PwCF with comorbid constipation are over or underrepresented in these discharges, relative to PwCF without comorbid constipation. Regardless of over or underrepresentation, the rate of presence of constipation in a given hospitalization is 2 to 3 times that of the general population (5.6%).

The presence of comorbid constipation was associated with increased odds of comorbid DIOS (aOR 1.89) on a given hospitalization. Previous work has identified meconium ileus as a risk factor for constipation in pediatric PwCF, an analysis that notably excluded patients with a history of DIOS.1 In neonates, meconium ileus must precede constipation by definition; the relationship between constipation and DIOS in older children and adults in this analysis is more difficult to ascertain. It is possible that constipation and DIOS could be independent comorbid diagnoses in a patient’s chart predating current hospitalization. Further prospective studies should examine whether there is a relationship between DIOS and constipation and investigate its temporality.

Observational studies in adult PwCF have shown a relationship between constipation or other gastrointestinal complaints and PS status.11, 12, 13 Studies in pediatric PwCF showed lower fecal fat absorption is associated with constipation, though the presence of PI only trended toward association with constipation.2 Subgroup analysis identified an association between increased total cost and constipation to be absent in the presence of PS ($493, P = .96) and strengthened in the presence of PI ($22,053, P < .01). Notably, the association between longer LOS and constipation retained significance in both PwCF with and without PI (1.10 days vs 1.39 days). Further work is needed to investigate the interplay between PI and constipation and whether there are aspects to their intersection unique to PwCF. Additional work should also investigate pancreatic enzyme supplementation and dosing in relation to constipation, which was unavailable in NIS.

As for sex, observational studies used patient-reported outcome measures such as Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptoms and found an association between female sex and the presence of constipation3 compared to this study that relied on ICD-10 codes.14 Thus, there may be differences in self-reported symptoms elicited by patient questionnaires compared with elective volunteering of information, as well as differences in translation of the reporting of these symptoms into ICD-10 codes. This study observed a higher rate of hospitalizations of female PwCF with constipation than male PwCF with constipation. This could be in part driven by over/underrepresentation of either sex through recurrent hospitalizations. Alternatively, it may align with the previously reported increased prevalence among women. Despite higher rates of hospitalization in female PwCF, an higher average LOS and cost is seen among male PwCF than female PwCF. These paradoxical findings are challenging to dissect. One contributor could be differences in the ranges of severity of self-reported symptoms—if males tend to underreport their symptoms, it might simultaneously increase LOS and decrease the number of observations in the data, particularly in milder cases. Further work is needed to verify these findings at the individual level.

A strength of this study was that its analysis was adjusted for sex, age, PI, hospital location, and capacity. Furthermore, it used a larger diverse data set representative of the United States population and previously validated ICD-10 codes. It is limited by the nature of the data set, which records ICD-10 and procedure codes but cannot be used to determine temporality. Furthermore, the data set has no longitudinal tracking after discharge and cannot distinguish readmissions from new admissions. Lastly, there is no tracking of medications in NIS, and we were unable to assess differences between patients taking and not taking HEMT, which should be further investigated.15

Conclusion

In this analysis of hospital discharge data from NIS between 2015 and 2019, constipation was present in 14.0% of hospitalizations of PwCF. Constipation is associated with increased LOS and total charges in both the general population and PwCF. In PwCF, the associated increase in total charges was ameliorated on analysis of PwCF without PI and persisted in those with PI. Further work is needed to determine management strategies for constipation in hospitalized PwCF, which may include early identification and treatment of both constipation and its most severe manifestation in PwCF, DIOS.

Acknowledgments

Authors’ Contributions:

Matt Pelton: Study conception, drafting manuscript. Arvind Bussetty: Drafting manuscript. Sarah Abdel-Meguid: Drafting manuscript. Harrison Clement: Data analysis. Natale Mazzaferro: Data analysis. Tae Yang Park: Manuscript writing. Sugeet Jagpal: Manuscript editing. Christopher Vélez: Manuscript editing. Keerthana Kesavarapu: Study conception, drafting manuscript, final approval of manuscript, accountable for the work.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding: The authors report no funding.

Ethical Statement: As this study is a narrative review of existing literature, it did not involve direct research with human participants or animals. Consequently, approval from an institutional review board (IRB) or ethics committee was not required. The review relied exclusively on publicly available data from previously published studies, and no identifiable personal information was used. All efforts were made to ensure the accurate representation and acknowledgment of the original research findings.

Data Transparency Statement: Data, analytic methods, and study materials will be made available to other researchers upon request.

Reporting Guidelines: Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA).

Material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2025.100640.

Supplementary Materials

References

- 1.Stefano M.A., Poderoso R.E., Mainz J.G., et al. Prevalence of constipation in cystic fibrosis patients: a systematic review of observational studies. J Pediatr. 2020;96:686–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Doef H.P., Kokke F.T., Beek F.J., et al. Constipation in pediatric cystic fibrosis patients: an underestimated medical condition. J Cyst Fibros. 2010;9:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moshiree B., Freeman A.J., Vu P.T., et al. Multicenter prospective study showing a high gastrointestinal symptom burden in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2023;22:266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2022.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houwen R.H., van der Doef H.P., Sermet I., et al. Defining DIOS and constipation in cystic fibrosis with a multicentre study on the incidence, characteristics, and treatment of DIOS. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:38–42. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181a6e01d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sethi S., Mikami S., LeClair J., et al. Inpatient burden of constipation in the United States: an analysis of national trends in the United States from 1997 to 2010. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:250–256. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali H., Pamarthy R., Manickam S., et al. Effect of constipation on outcomes in mechanically ventilated patients. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2022;35:284–290. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2022.2035153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rector T.S., Wickstrom S.L., Shah M., et al. Specificity and sensitivity of claims-based algorithms for identifying members of medicare+choice health plans that have chronic medical conditions. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1839–1857. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briesacher B.A., Quittner A.L., Fouayzi H., et al. Nationwide trends in the medical care costs of privately insured patients with cystic fibrosis (CF), 2001-2007. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011;46:770–776. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peery A.F., Dellon E.S., Lund J., et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1179–1187.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khera R., Krumholz H.M. With great power comes great responsibility: big data research from the national inpatient sample. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10 doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.003846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayee B., Watson K.L., Campbell S., et al. A high prevalence of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms in adults with cystic fibrosis is detected using tools already validated in other GI disorders. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:881–888. doi: 10.1177/2050640619841545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Proesmans M., De Boeck K. Evaluation of dietary fiber intake in Belgian children with cystic fibrosis: is there a link with gastrointestinal complaints? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35:610–614. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200211000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker S.S., Borowitz D., Duffy L., et al. Pancreatic enzyme therapy and clinical outcomes in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2005;146:189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank L., Kleinman L., Farup C., et al. Psychometric validation of a constipation symptom assessment questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:870–877. doi: 10.1080/003655299750025327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwarzenberg S.J., Vu P.T., Skalland M., et al. Elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor and gastrointestinal outcomes in cystic fibrosis: report of promise-GI. J Cyst Fibros. 2023;22:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2022.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.