Abstract

Ferroptosis is one of the most critical biological consequences of glutathione depletion. Excessive oxidative stress, indicated by an elevated oxidized glutathione (GSSG)/reduced glutathione (GSH) ratio, is recognized as a key driver of ferroptosis. However, in glutathione depletion-induced ferroptosis, a marked decrease in total glutathione levels (including both GSH and GSSG) is frequently observed, yet its significance remains understudied. Protein S-glutathionylation (protein-SSG) levels are closely linked to the redox state and cellular glutathione pools including GSH and GSSG. To date, the role of protein-SSG during cell ferroptosis induced by glutathione depletion remains poorly understood. Here, we demonstrated that upregulation of CHAC1, a glutathione-degrading enzyme, acted as a key regulator of protein-SSG formation and exacerbated glutathione depletion-induced ferroptosis. This effect was observed in both in vitro and in vivo models, including erastin-induced ferroptosis across multiple cell lines and acetaminophen overdose-triggered ferroptosis in hepatocytes. Deficiency of CHAC1 resulted in increased glutathione pools, enhanced protein-SSG, improved liver function, and attenuation of hepatocyte ferroptosis upon acetaminophen challenge. These protective effects were reversed by CHAC1 overexpression. Using quantitative redox proteomics, we identified glutathione pool-sensitive S-glutathionylated proteins. As an important example, we discovered that ADP-ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6) was regulated by S-glutathionylation during glutathione depletion-induced ferroptosis. Our findings revealed that CHAC1 upregulation reduced the S-glutathionylation of ARF6, resulting in decreased ARF6 levels in lysosomes. This, in turn, enhanced the localization of the transferrin receptor (TFRC) on the cell membrane and increased transferrin uptake, ultimately compromising the protective role of ARF6 in ferroptosis induced by glutathione depletion. Targeting TFRC using GalNAc-siTfrc mitigated acetaminophen-induced liver injury in vivo. In conclusion, our study provide evidence that availability of glutathione pools affects protein S-glutathionylation and regulates protein functions to influence the process of ferroptosis, which opens an avenue to understanding the cell ferroptosis induced by glutathione depletion.

Keywords: Protein S-Glutathionylation, Ferroptosis, CHAC1, ADP-Ribosylation factor 6, Transferrin

1. Introduction

Glutathione homeostasis plays a pivotal role in progressively regulating a multitude of cellular biological functions and disease pathogenesis. Glutathione deficiency is closely associated with the progression of various human diseases and the aging process [1]. Among the diverse dysfunctions induced by glutathione deficiency, ferroptosis emerges as one of the most critical biological events. Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death driven by lipid peroxidation [2,3]. The discovery of ferroptosis can be traced back to as early as the 1950s, when researchers first identified a distinct form of cell death triggered specifically by cystine deprivation, unlike the effects observed with the deprivation of other amino acids. Subsequent decades of research have demonstrated that cystine deprivation leads to glutathione depletion, ultimately triggering ferroptosis. Consistent with this mechanism, the first identified ferroptosis-inducing compound, erastin, was found to act by inhibiting the cystine/glutamate antiporter, SLC7A11. This inhibition disrupts cysteine-dependent synthesis of reduced glutathione (GSH), thereby inducing ferroptosis [4,5]. The conversion of GSH to oxidized glutathione (GSSG), catalyzed by the glutathione-dependent peroxidase GPX4, represents the central antioxidant reaction scavenge lipid peroxide [6]. The GSSG/GSH ratio is widely recognized as a critical indicator of cellular oxidative status [7]. Excessive oxidative stress is considered a key driver of ferroptosis. Indeed, the cellular content of GSSG is regulated not only by the redox state but also by the availability of GSH as its precursor substrate. In ferroptosis triggered by glutathione depletion across various contexts, the depletion of the total glutathione pool including both GSH and GSSG has frequently been observed [[8], [9], [10]]. This suggests that explaining glutathione depletion-induced ferroptosis solely by the imbalance in the GSSG/GSH ratio might be an oversimplification.

Protein S-glutathionylation (protein-SSG) has been recently shown to play critical roles in regulating enzyme activity, subcellular localization, protein interactions, and stability, thereby impacting on the onset and progression of various diseases [[11], [12], [13], [14]]. As a reversible and dynamic oxidative posttranslational modification that forms a disulfide bond between glutathione and a cysteine residue in the target protein, protein-SSG can occur spontaneously with or without enzymes. The thiol groups of proteins are first oxidized into such high-oxidation groups as sulfenic acid (P–SOH) and sulfinic acid (P–SOOH) by reactive oxygen species (ROS), as well as S-nitrosothiols (P–SNO) by reactive nitrogen species. These high-oxidation groups react with GSH to form S-glutathionylation, or GSSG can directly modify the proteins [[14], [15], [16]]. Protein-SSG can be reversed to protein-SH upon resolution of oxidative status. ROS serve as crucial signalling molecules and play essential physiological roles at basal levels within cells; however, excessive ROS accumulation leads to oxidative stress [17]. Thus, protein-SSG is closely associated with cellular oxidative status. However, the role of protein-SSG during cell ferroptosis induced by glutathione depletion remains unclear.

Protein S-glutathionylation can occur spontaneously in the presence of ROS and is closely linked to glutathione availability, as both GSH and GSSG serve as substrates for this modification. The maintenance of GSH homeostasis requires the coordinated regulation of GSH biosynthesis, transport, efflux, peroxidases (GPX4), reductases, consumption, and degradation [18]. CHAC1 is an enzyme that catalyzes the degradation of intracellular GSH. Inactivation of CHAC1 effectively preserves GSH levels in mouse models [19]. Importantly, CHAC1 is significantly upregulated under GSH-depletion induced ferroptosis and has been widely considered as a reliable biomarker for ferroptosis [3,20]. To date, how CHAC1 upregulation impacts on ferroptosis has not been understood. Whether CHAC1 regulates the glutathione pool (GSH + GSSG) to coordinate closely with protein-SSG and thus affects cell ferroptosis induced by glutathione depletion becomes a pressing question.

In ferroptosis, iron acts as a catalyst for lipid peroxidation via Fenton reactions. The transferrin receptor (TFRC), the primary cellular iron transporter, has recently been identified as a detection marker for ferroptosis due to its membrane clustering [21]. Suppressing TFRC expression reduces ferroptosis and significantly mitigates hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury in older livers [22]. Conversely, TFRC upregulation exacerbates ferroptosis during coxsackievirus B3 infection [23]. Additionally, TGF-β elevates intracellular Fe2+ levels by upregulating TFRC, thereby activating fibroblasts. Notably, TFRC deficiency in fibroblasts inhibits bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis [24]. ADP-ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6) regulates clathrin-mediated endocytosis, clathrin-independent endocytosis, and endosomal recycling [25]. A classic example of clathrin-dependent receptor-mediated endocytosis is the internalization and recycling of the transferrin (TF)/transferrin receptor (TFRC) complex [26].

Here, we demonstrate that CHAC1 upregulation aggravates glutathione depletion-induced cell ferroptosis. We identify CHAC1 as an important regulator of protein-SSG in both in vitro and in vivo models including erastin-induced ferroptosis in multiple cell lines and acetaminophen (APAP)-triggered ferroptosis in hepatocytes. Using a quantitative redox proteomics approach, we identified 482 proteins that were glutathionylated under homeostatic conditions, of which the modification of 221 proteins was subsequently altered by CHAC1 during ferroptosis. As an important example, we discovered that ARF6 is regulated by S-glutathionylation during glutathione depletion-induced ferroptosis. The S-glutathionylation of ARF6 modulates TFRC and transferrin uptake, which exerts an inhibitory effect on the ferroptosis process. Our study provides evidence that availability of glutathione pools affects protein S-glutathionylation and regulates protein functions to influence the process of ferroptosis, which opens an avenue to understanding the cell ferroptosis induced by glutathione depletion.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animal studies

C57BL/6J mice, aged six to eight weeks, were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Shanghai SLAC (Shanghai, China). Chac1 knockout mice (Chac1−/− mice; C57BL/6 N) were constructed using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome engineering and were provided by Cyagen Biosciences (Suzhou, China). In this strain, exons 1–3 of the Chac1 gene were removed, and gene expression was abolished. Male and female homozygous Chac1−/− mice were viable and fertile. Littermate mice were used as wild-type controls (Chac1+/+). The mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility with 12-h light/dark cycle at 22 °C in Fudan University Experimental Animal Center (Shanghai, China), were fed on a normal diet, and had ad libitum access to water. All mice were fasted overnight for approximately 12 h before APAP administration. Acetaminophen (APAP, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in saline at 37 °C just before the experiments were conducted. The mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with saline or 300 mg/kg APAP and then euthanised to collect blood and liver samples after 6 h or at other indicated times. GalNAc-conjugated siRNA targeting TFRC (GalNAc siTfrc, 20 mg/kg) and GalNAc siNC (20 mg/kg) were administered to mice via subcutaneous injection three days to induce Tfrc knockdown in hepatocytes. The sequences of GalNAc siTfrc was listed in Table S1. The protocols used in all studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Fudan University.

2.2. Human sample collection

The specimens consisted of nine needle biopsies obtained from patients with drug-induced liver injury (DILI) caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. For healthy controls, liver tissues were obtained from the livers of transplant donors. The clinical data of the patients with DILI are shown in Table S2, numbered from patient 1 to 9. All the patients provided informed consent to participate in this study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Jiaotong University Renji Hospital in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

2.3. Adenovirus infection

The CHAC1 (Ad-CHAC1) and control (Ad-GFP) adenoviruses were purchased from GeneChem Technologies Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Ad- CHAC1 or Ad-GFP was injected via the tail vein of each Chac1−/− mouse at a dose of 1 × 108 viral titres. After 48 h, the mice were injected i.p. with APAP (300 mg/kg) and subsequently euthanised after 6 h. For in vitro experiments, primary mouse hepatocytes (PMHs) were incubated with Ad-CHAC1 or Ad-GFP for 12 or 36 h, followed by treatment with APAP at the indicated time intervals.

2.4. Cell cultures

Primary mouse hepatocytes (PMHs) were isolated via in situ liver perfusion with type IV collagenase (Gibco, Cat. # 17104019), following established protocols [27]. The PMHs were then passed through a 70-μm cell strainer and centrifuged in 50 % Percoll (Yeasen, China, Cat. # 40501ES60) at 50×g for 5 min to separate the viable and nonviable hepatocytes. The hepatocytes were resuspended in DMEM/high glucose (VivaCell, China, Cat. #C3103-0500) supplemented with 10 % FBS (ExCell Bio, China, Cat. # FSD500) and plated onto gelatin-coated dishes (Cell Biologics, Cat. # 6950).

Mouse hepatoma (Hepa1-6), human embryonic kidney (293T), human colonic adenocarcinoma lung metastasis (T84), human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2), human oesophageal carcinoma (TE-1), human prostate cancer (DU145), human non-small cell lung cancer (H1299), human ovarian cancer (A2780), human ovarian cancer (SKOV3), and human gastric cancer (HGC27) cells were cultured in DMEM or RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10 % FBS (ExCell Bio, Cat. # FSD500), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B.

2.5. Transfection

SiRNA and negative controls (siNCs) were purchased from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The target sequences of the siRNAs are listed in Table S3. The plasmids including pCDH-CMV-ARF6-3xMyc, pCDH-CMV-ARF6-mCherry, pCDH-CMV-ARF6-C90A-3xMyc, pCDH-CMV-ARF6-C90A-mCherry, pCDH-CMV-ARF6-C90D-3xMyc, pCDH-CMV-ARF6-C90D-mCherry, and pCDH-CMV-ARF6-C90D-Myc were generated by standard cloning methods. All plasmids were verified by sequencing the entire coding region. The in vitro transfection with siRNAs or plasmids was performed using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, USA).

2.6. Construction of the ARF6−/− H1299 and Arf6−/− hepa1-6 cell line

We employed CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing to achieve gene knockout through lentivirus-mediated gene expression. Small guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting human ARF6 (Target DNA sequence: AACTGGGCCTGACCCGGATT, PAM sequence: TGG) and mouse Arf6 (Target DNA sequence: CGTATGGGATGTGGGCGGCC, PAM sequence: AGG) were inserted into the lenti-CRISPR-puro plasmid. Lentiviral particles were generated in the 293T packaging cell line. H1299 cells and Hepa1-6 cells were infected with the lentivirus and subsequently subjected to ARF6/Arf6 knockout (KO) screening. The ARF6−/− H1299 and Arf6−/− hepa1-6 cell line were generated through puromycin selection, and successful knockout was confirmed by Western blot analysis and gene sequencing.

2.7. RNA extraction and real time-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Cat. # 12183555). Subsequently, cDNA synthesis was performed using a ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Kit (TOYOBO, Cat. # QPK-201). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using a SYBR Green PCR Kit (Yeasen, Cat. # 11203ES03). For each sample, the expression of each target gene was normalized to the expression of 36b4 or β-actin. The relative expression of genes was measured using the 2 (−ΔΔCt) method. The primer sequences are listed in Table S4.

2.8. Isolation of lysosome and plasma membrane fractions from cells

Lysosome and plasma membrane fractions were isolated from cells using the Minute™ Lysosome Isolation Kit (Invent Biotechnologies, Minnesota, USA, Cat. No. LY-034), following a modified protocol. Briefly, 3 × 106 cells, treated as indicated, were collected, pelleted, resuspended, and lysed in 500 μL of buffer A. The lysate was transferred to a filter cartridge. Following centrifugation at 16,000×g for 30 s, the filter was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended. The sample was then centrifuged at 2000×g for 3 min to remove nuclei, large cell debris, and un-ruptured cells. The resulting supernatant was transferred to a fresh 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged at 11,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C. The pellet obtained primarily contained mitochondria and cell debris.

Carefully transfer 400 μL of the supernatant to a fresh 1.5 mL tube, and centrifuge at 16,000×g for 30 min at 4 °C. Transfer the supernatant to a new 2 mL tube. Add 1.5 mL PBS buffer and centrifuge again at 16,000×g for 30 min at 4 °C. The final pellet represents the plasma membrane fraction. This pellet was resuspended in 30 μL of NP40 buffer containing 0.4 % SDS for Western blot analysis.

For lysosome isolation, resuspend the remaining pellet after removing the 400 μL supernatant containing the plasma membrane fraction in 200 μL of cold buffer A and vortex vigorously. Centrifuge the sample at 2000×g for 4 min. Transfer the supernatant to a fresh 1.5 mL tube, add 100 μL of buffer B (giving a 2:1 ratio of supernatant to buffer B), and mix well. Incubate the tube on ice for 30 min before centrifuging at 11,000×g for 10 min. The resulting pellet contains the lysosome fraction, which was resuspended in 80 μL of NP40 buffer containing 0.4 % SDS for Western blot analysis.

2.9. Western blot analysis

The cells treated as indicated were lysed using NP40 buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein levels were determined using a BCA protein assay. For Western blot, lysates were probed with specific antibodies against CHAC1 (Proteintech, Cat. # 15207-1-AP, 1:1000), glutathione (Virogen, Cat. # 101-A, 1:1000), ARF6 (Affinity, Cat. # DF6170, 1:1000), TFRC (Abcam, Cat. # ab269513, 1:2000), 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE, Abcam, Cat. # ab46545), FLAG-tag (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. #F1804, 1:3000), and Myc-tag (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat. # sc-40, 1:1000). β-actin (Proteintech, Cat. # 66009-1-Ig, 1:10000), and GAPDH (Proteintech, Cat. # 10494-1-AP, 1:5000) were used as loading control. For membrane proteins, Na+/K+ ATPase ((Proteintech, Cat. # 55187-1-AP, 1:1000) was used as an internal reference. For lysosomal proteins, LAMP1 (Abclonal, Cat. #21194, 1:1000) was used as an internal reference. For the Western blot analysis targeting glutathione and 4-HNE, the sample preparation did not include the addition of reducing agent β-mercaptoethanol (non-reducing loading buffer). Goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP (Affinity, Cat. #S0001, 1:3000) and goat anti-mouse IgG HRP (Affinity, Cat. #S0002, 1:3000) were used as secondary antibodies. Proteins were visualised using an ECL kit (Tanon, Cat. # 180–501) and a Tanon-4200 gel imaging system.

2.10. Biochemical assays and histopathological analyses

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were measured using commercial assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng, Cat. #C009-2-1, C010-2-1) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded liver tissue sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and analyzed. Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were measured using the appropriate assay kit (Dojindo, Japan, Cat. #M496) and normalized to the protein concentration according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.11. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded liver tissue sections. Sections were incubated with an anti-CHAC1 (Proteintech, Cat. # 15207-1-AP) and anti- 4-HNE (Abcam, Cat. # ab46545) antibody at 4 °C overnight. Subsequently, tissues were incubated with a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Tissue sections were counterstained with DAB and haematoxylin. IHC staining for CHAC1 and 4-HNE was analyzed using histological scoring. The scoring criteria were as follows: score = 0, no staining; score = 1, 1–25 %; score = 2, 26–50 %; score = 3, 51–75 %; and score = 4, 76–100 %. The intensity scores represented the average value: 0 (none), 1 (weak), 2 (moderate), and 3 (strong). Each sample was evaluated in a blinded manner by a senior pathologist and two researchers. The final score for each sample was the average of three scores from the researchers. The quantity and intensity scores were then multiplied to obtain a total score ranging from 0 to 12, representing the histological score.

2.12. GSH and GSSG concentration determination

GSH and GSSG levels were quantified using a GSSG/GSH Quantification Kit (Dojindo, Cat. #G263) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In addition, GSH and GSSG levels were normalized to the protein concentration.

2.13. Cell viability

The cells were seeded in 96-well microplates and exposed to the specified treatments. Cell viability was assessed using the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay Kit (Promega, Cat. #G7570) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Luminescence intensity from each well was measured with the Synergy™ H1 Hybrid Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek, USA).

Calcein-AM/PI Double Staining Kit was also used to assess cell viability. Cells were washed twice with PBS before staining and then incubated with staining solution at 37 °C for 30 min, following the manufacturer's protocol (Dojindo, Cat. #C542). After three washes with PBS, the cells were imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Nexcope, China), and Image J software (version 1.53c) was used to count fluorescent cells.

2.14. Lipid peroxides determination

Cellular lipid peroxidation levels were determined using a C11 BODIPY 581/591 fluorescent probe (Dojindo, Cat. #L267) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.15. Measurement of Fe2+ level

FerroOrange (Dojindo, Cat. #F374) was used to assess the Fe2+ levels. PMHs were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well. After cell adhesion, the cells were transfected with Arf6 siRNA for 48 h or infected with AdGFP or AdCHAC1 adenovirus for 36 h, and then treated with 20 mM APAP for 6 h. Following the removal of the previous culture medium, the cells were washed twice with PBS. Subsequently, a working solution of FerroOrange fluorescent probe at a concentration of 1 μmol/L was added to the cells. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in the dark for 30 min, and then incubated with DAPI for 10 min for nuclear staining. Finally, the cells were observed and images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope (Nexcope). Image J software was used to quantify the fluorescence intensity of the FerroOrange.

2.16. Fluorescent transferrin uptake assay

Cells treated as described were placed on ice for 10 min, washed twice with pre-chilled wash solution (HBSS containing 1 % BSA), and then incubated with a final concentration of 25 μg/mL Alexa Fluor® 546 (Invitrogen, Cat. #T23364) or Alexa Fluor® 647 transferrin (Invitrogen, Cat. #T23366) at 37 °C for 15 min. After incubation, the cells were washed twice with wash solution. They were then fixed and stained with DAPI for 10 min to visualize the nuclei. Fluorescence images were captured using a confocal microscope (NOVEL NCF950, Ningbo, China), and transferrin levels in the cells were quantified using Image J software.

2.17. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and data analysis

RNA purified from the cultured cells was converted into cDNA libraries and assessed for quality using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Sequencing was performed using a BGI DNBSEQ-T7 sequencer (OE Biotech Co., Ltd., (Shanghai, China). Raw RNA sequencing data were deposited in the NCBI SRA database under the accession number PRJNA1086892. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using Cuffdiff and defined as P < 0.05. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses of DEGs was performed using the DAVID online analysis system (https://davidbioinformatics.nih.gov/home.jsp).

2.18. Enrichment of protein-SSG and LC–MS/MS

PMHs in 10-cm dishes treated as indicated were scraped using cell scrapers and pelleted by centrifugation. The cell pellets were heated at 95 °C for 10 min, and then lysed in four times the volume of lysis buffer (1 % SDS, 1 % protease inhibitor cocktail, and 25 mM iodoacetamide) under ultrasonication on ice. Iodoacetamide (25 mM) was added, and the alkylation reaction was performed at room temperature in the dark for 1 h. The samples were centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min at 12,000×g to remove the cell debris, and the supernatant was transferred to a new centrifuge tube for protein concentration determination using a BCA kit.

For the reduction reaction, 480 μg of proteins (1 μg/μL) were treated in 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) with 1 M urea, 2.5 μg/mL Glrx 1 M, 0.25 mM GSSG, 1 mM NADPH, and 4 U/mL Glutathione Reductase, and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min, immediately placed on ice, and transferred to a 0.5-mL Amicon Ultra 10 K filter. Excess reagents were removed by buffer exchanged with 3 × 8 M urea (pH 7.0) resulting in a final volume of 30–40 μL. Next, each protein channel was labeled with its respective iodo-TMT reagent and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. DTT (final concentration: 20 mM) was added and the cells were incubated for another 15 min in the dark.

Proteins were precipitated with acetone, centrifuged, washed, and resuspended in 200 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate buffer for overnight digestion with trypsin at a 1:50 enzyme-to-substrate ratio. Digested samples were reduced at 37 °C for 60 min using 5 mM dithiothreitol and subsequently alkylated in the dark at room temperature with 11 mM iodoacetamide for 45 min. The peptides were purified using Strata X SPE columns and vacuum-dried before resuspension in 1X TBS. The samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-TMT resin in an end-to-end mixture. Following incubation, the supernatant was removed and the resin was washed eight times with one column volume of TBS (5 min per wash), followed by three washes with one column volume of water. The components were then eluted with four column volumes of TMT elution buffer (50 % acetonitrile and 0.4 % trifluoroacetic acid), and the eluates were dried under vacuum. The peptides were desalted using C18 ZipTips prior to LC-MS/MS analysis.

MS/MS analysis was conducted using MaxQuant software (version 1.6.15.0) to search 17,132 sequences, incorporating a reverse decoy database and contaminant database to manage the false discovery rate (FDR) and contamination issues. The settings included trypsin/P enzyme allowing up to two missed cleavages, peptide criteria with a minimum length of seven amino acids and a maximum of five modifications, mass tolerances of 20 ppm for precursor ions in the first search and 4.5 ppm in the main search, and 20 ppm for fragment ions. The quantification method was set to iodoTMT-6plex, with both protein and PSM identification FDRs set to 1 %, requiring at least one unique peptide for protein identification. IodoTMT-based proteomics and analyses were performed by Jingjie PTM Biolab Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China).

2.19. Pulldown assay and detection of ARF6-SSG by LC-MS/MS

Cell lysates were prepared from 293T cells (1 x 107) overexpressing Myc-tagged ARF6 and incubated with Anti-Myc magnetic beads at 4 °C for 3 h. After washing the beads five times with PBS containing 0.1 % Tween 20, the beads were boiled in non-reducing loading buffer. The protein mixtures were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the ARF6 band was excised for in-gel digestion. Proteins were then identified by mass spectrometry. Briefly, gel digestion was performed using sequencing grade-modified trypsin in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate at 37 °C overnight. The peptides were extracted twice with 1 % trifluoroacetic acid in 50 % acetonitrile aqueous solution for 1 h. The peptide extracts were then centrifuged in a SpeedVac to reduce the volume. The peptides were resuspended in 20 μL of 0.1 % TFA, followed by centrifugation at 20,000×g at 4 °C for 15 min to remove any particulate impurities.

For LC-MS/MS analysis, peptides were separated by a 40 min gradient elution at a flow rate 0.300 μL/min with a Thermo-Dionex Ultimate 3000 HPLC system, which was directly interfaced with a Thermo Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer. The analytical column was a homemade fused silica capillary column (75 μm ID, 150 mm length; Upchurch, Oak Harbor, WA) packed with C-18 resin (300 A, 5 μm; Varian, Lexington, MA). Mobile phase A consisted of 0.1 % formic acid, and mobile phase B consisted of 100 % acetonitrile and 0.1 % formic acid. An LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent acquisition mode using Xcalibur 4.0.27.10 software and there is a single full-scan mass spectrum in the Orbitrap (300–1500 m/z, 120,000 resolution) followed by 3 s data-dependent MS/MS scans in an Ion Routing Multipole at 40 % normalized collision energy (HCD).

MS/MS spectra from each LC-MS/MS run were searched against the human database using Proteome Discoverer (Version 1.4) searching algorithm. The search criteria were as follows: full tryptic specificity was required; two missed cleavages were allowed; carbamidomethylation was set as fixed modification; oxidation (M) and Glutathione (SSG) were set as variable modifications; precursor ion mass tolerance was 10 ppm for all MS acquired in the Orbitrap mass analyzer; and fragment ion mass tolerance was 0.8 Da for all MS2 spectra acquired in the LTQ. High confidence score filter (FDR <1 %) was used to select the “hit” peptides and their corresponding MS/MS spectra were manually inspected.

2.20. Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± SEM. GraphPad Prism software (version 9.0; San Diego, CA, USA) was used for the calculations, statistical analyses, and graphics generation. Two-parameter comparisons were performed using a two-tailed Student's t-test. Multiple-group analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the recommended post hoc tests using GraphPad Prism software (version 9.0). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Reduced protein-SSG is associated with decreased glutathione pools by CHAC1 induction in multiple cell types undergoing glutathione deprivation-induced ferroptosis

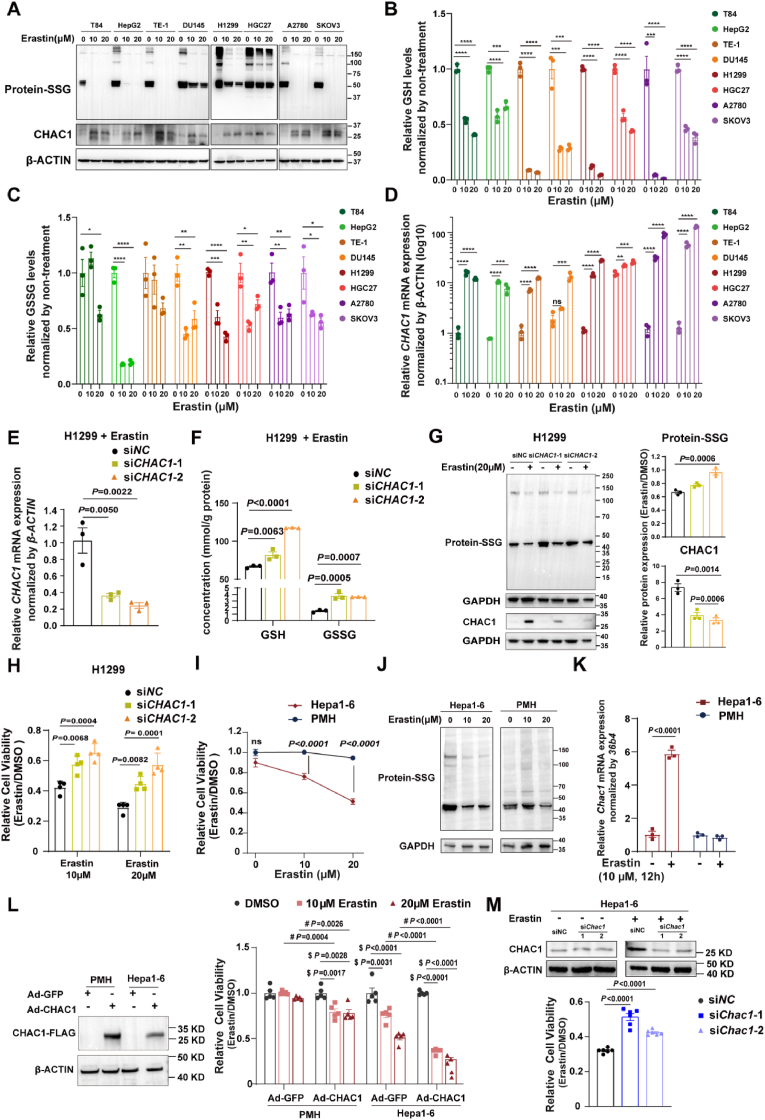

To investigate the pattern of protein-SSG in ferroptotic cells induced by glutathione depletion, we treated multiple human cell lines (human colonic adenocarcinoma [T84], hepatocellular carcinoma [HepG2], human oesophageal cancer [TE1], human prostate carcinoma [DU145], human lung adenocarcinoma [H1299], human ovarian cancer [A2780 and SKOV3], and human gastric cancer [HGC27]) with erastin. In these cells undergoing ferroptosis induced by erastin (Fig. S1A), the overall protein-SSG was significantly decreased (Fig. 1A). Given that glutathione pools are strongly associated with protein-SSG, we measured the levels of GSH and GSSG in these cell lines. Although the GSSG/GSH ratio was elevated in most of these cell lines (Fig. S1B), both GSH and GSSG were markedly depleted in erastin-induced ferroptotic cells (Fig. 1B and C). Considering that CHAC1 is responsible for glutathione degradation and GLRX is the most well-studied catalytic enzyme for deglutathionylation, we examined the expression levels of CHAC1 and GLRX in these cells. CHAC1 was significantly upregulated in all cell lines at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 1A and D). We found that in cells such as HepG2, TE-1, and H1299, where protein-SSG levels were significantly reduced after erastin treatment, GLRX levels remained unchanged (Fig. 1D and Fig. S1C). Even in cells, such as T84, DU145, HGC27, A2780, and SKOV3 with slightly higher GLRX levels, the induction of CHAC1 was much more substantial than that of GLRX (Fig. 1D and Fig. S1C). These findings suggest that the overall availability of glutathione, encompassing both GSH and GSSG, plays a crucial role in determining protein-SSG levels. In addition to GLRX-regulated deglutathionylation, CHAC1-mediated alterations in the glutathione pool may be pivotal in regulating protein-SSG during cell ferroptosis induced by glutathione depletion.

Fig. 1.

Reduced protein-SSG is associated with decreased glutathione pools by CHAC1 induction in multiple cell types undergoing glutathione deprivation-induced ferroptosis. (A) Western blot analysis of S-glutathionylated proteins and CHAC1 in eight human cell lines treated with DMSO or erastin (10 μM, 20 μM). β-actin was used as an internal reference. (B) Quantification of GSH level (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biologically independent samples, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001, by one-way ANOVA). (C) Quantification of GSSG levels (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biologically independent samples, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA). (D) RT-qPCR analysis of CHAC1 mRNA and Western blot analysis of CHAC1 protein levels. mRNA values were compared to those of DMSO-treated T84 cells (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biologically independent samples, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA). (E) RT-qPCR analysis of CHAC1 mRNA levels in H1299 cells transfected with CHAC1 siRNA and then treated with 10 μM erastin (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biologically independent samples, one-way ANOVA). (F) Quantification of GSH and GSSG levels in H1299 cells transfected with CHAC1 siRNA and then treated with 10 μM erastin (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biologically independent samples, one-way ANOVA). (G) Western blot analysis of CHAC1 and S-glutathionylated proteins in H1299 cells transfected with CHAC1 siRNA and treated with 20 μM erastin. GAPDH was used as an internal reference. The relative expression levels of these proteins were normalized by their respective DMSO controls (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biologically independent experiments, one-way ANOVA). (H) Relative cell viability of H1299 cells treated with erastin (10 μM, 20 μM) for 24 h, normalized by DMSO control, as measured by the CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 4 biologically independent samples, t-test). (I) Cell viability of PMHs and Hepa1-6 cells treated with erastin (10 μM, 20 μM) for 24 h, normalized by DMSO control (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 5 biologically independent samples, one-way ANOVA). (J) Western blot analysis of S-glutathionylated proteins in PMHs and Hepa1-6 cells treated with DMSO, or 10 μM or 20 μM erastin. GAPDH was used as an internal reference. (K) RT-qPCR analysis of Chac1 mRNA levels in PMHs and Hepa1-6 cells treated with DMSO, or 10 μM erastin for 12 h. (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biologically independent samples, t-test). (L) Western blot analysis of CHAC1-FLAG protein levels in PMHs and Hepa1-6 cells infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-CHAC1 adenoviruses. β-ACTIN was used as an internal reference. Cell viability of PMHs and Hepa1-6 cells infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-CHAC1 adenoviruses and treated with DMSO or erastin (10 μM, 20 μM) for 24 h (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 5 biologically independent samples, $ for one-way ANOVA and # for t-test). (M) Western blot analysis of CHAC1 protein levels in Hepa1-6 cells were transfected with NC siRNA and Chac1 siRNA and treated with DMSO or 10 μM erastin. β-ACTIN was used as an internal reference. Cell viability of Hepa1-6 cells infected with NC siRNA and Chac1 siRNA and treated with DMSO or 10 μM erastin for 24 h (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 6 biologically independent samples, one-way ANOVA).

PMH, primary mouse hepatocyte; GSH, glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione.

We also examined changes in CHAC1 expression and protein-SSG levels during GPX4 inactivation-induced ferroptosis. As a result, RSL3 (a GPX4 inhibitor) induced ferroptosis in H1299 cells (Fig. S1D), but unlike erastin, it did not significantly upregulate CHAC1 mRNA or protein levels (Fig. S1E and S1G). During RSL3-induced ferroptosis, while the GSSG/GSH ratio increased significantly, the total glutathione pool (GSH + GSSG) remained largely unchanged (Fig. S1F). Notably, we observed a modest increase in protein-SSG levels, likely attributable to oxidative stress (Fig. S1G). In contrast, ferroptosis induced by glutathione depletion triggered dramatic CHAC1 upregulation, leading to a subsequent decrease in both the glutathione pool and protein-SSG levels.

Next, we knocked down CHAC1 expression using siRNA in H1299 cells exposed to erastin (Fig. 1E) to investigate the role of glutathione availability in protein-SSG and ferroptosis. As expected, CHAC1 knockdown increased the levels of both GSH and GSSG in ferroptotic H1299 induced by erastin (Fig. 1F). CHAC1-mediated GSH degradation may lead to reduced GSSG levels, since GSH serves as its substrate. Therefore, CHAC1 reduces the overall availability of glutathione, which serves as the substrate for protein-SSG. Notably, CHAC1 knockdown partially suppressed the reduction of protein-SSG (Fig. 1G) and cell death (Fig. 1H) induced by erastin in H1299 cells.

We also investigated this phenomenon in primary cells, including primary mouse hepatocytes (PMHs). Surprisingly, PMHs showed no response to erastin (Fig. 1I). In contrast, Hepa1-6 cells (mouse hepatocellular carcinoma cells) were sensitive to erastin (Fig. 1I). We hypothesized that this discrepancy might be related to differences in protein-SSG levels. Indeed, erastin induced a more pronounced decrease in protein-SSG levels in Hepa1-6 cells compared to that in PMHs (Fig. 1J). Notably, CHAC1 expression was not induced in PMHs upon erastin treatment, whereas it was significantly upregulated in Hepa1-6 cells (Fig. 1K). Furthermore, overexpression of CHAC1 resulted in reduced cell viability following erastin treatment in both PMHs and Hepa1-6 cells (Fig. 1L). In contrast, CHAC1 knockdown increased cell viability upon erastin treatment in Hepa1-6 cells (Fig. 1M).

Overall, our findings indicate that CHAC1-mediated modulation of glutathione pools and protein S-glutathionylation play a crucial role in ferroptosis induced by glutathione deprivation across multiple cell types.

3.2. Decreased glutathione pools by CHAC1 reduces protein-SSG and aggravates APAP-induced hepatotoxicity and ferroptosis in primary mouse hepatocytes

As described above, erastin failed to induce CHAC1 upregulation, reduce protein-SSG levels, or trigger ferroptosis in primary mouse hepatocytes. Instead, we and other groups revealed that hepatocyte ferroptosis substantially contributes to APAP-induced liver injury (AILI) in mouse models [8,28,29]. AILI is initiated by the formation of N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), a metabolite derived from cytochrome P450 enzymes. NAPQI depletes liver GSH, forms adducts with cellular proteins, and ultimately leads to liver damage [30]. In the AILI mouse model, both GSH and GSSG levels in livers were significantly depleted 2 h after APAP overdose but were fully restored by 8 h [9]. Therefore, APAP-induced hepatotoxicity serves as an appropriate model for studying glutathione depletion-induced ferroptosis in PMHs.

We revisited our published RNA sequencing data ([31], SRA database of NCBI: PRJNA731100) and found that Chac1 is one of the top upregulated genes in liver tissues from mice challenged with 300 or 750 mg/kg APAP (Fig. 2A and B and Fig. S2A). The significant induction of Chac1 mRNA in the liver tissues of mice 3, 6, and 12 h after 300 mg/kg or 750 mg/kg APAP challenge was validated using RT-qPCR (Fig. 2C). We detected CHAC1 expression in the liver tissues of patients with AILI and healthy controls using IHC. Consistently, CHAC1 expression (presented as H-scores in IHC sections) was significantly higher in liver tissues from patients with AILI than in those from healthy controls (Fig. 2D). The mRNA level of Chac1 was also time-dependently induced by APAP challenge in PMHs (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Decreased glutathione pools by CHAC1 reduces protein-SSG and aggravates APAP-induced hepatotoxicity and ferroptosis in primary mouse hepatocytes. (A) The heatmap shows the relative levels of upregulated and downregulated genes in the liver tissues of mice treated with 300 mg/kg APAP for 3 h, 750 mg/kg APAP for 3 h, 300 mg/kg APAP for 6 h, and 750 mg/kg APAP for 6 h compared to the saline group. The heatmap was ranked by fold change of 750 mg/kg APAP for 3 h group versus the saline group for 3 h. (Fold change ≥1.5, P < 0.05) (n = 3 mice/group). (B) Volcano plots shows upregulated and downregulated genes from RNA transcriptome data of the group treated with 750 mg/kg APAP for 6 h compared to the saline group (Fold change ≥1.5, P < 0.05; n = 3 mice/group). (C) RT-qPCR analysis of Chac1 mRNA levels in mouse liver tissues treated with saline or 300 and 750 mg/kg APAP for 3, 6, or 12 h. (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 7 mice/group, one-way ANOVA). (D) Immunohistochemical staining of CHAC1 in liver sections from healthy controls (n = 9) and patients with AILI (n = 9), with quantification of immunohistochemical scores (Data are mean ± SEM, t-test). The black arrow indicates positive staining. Scale bar = 100 μm. (E) RT-qPCR analysis of Chac1 mRNA levels in PMHs with or without 20 mM APAP challenge for 1, 3, 6, and 12 h (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biologically independent samples, t-test). (F) Western blot analysis of S-glutathionylated proteins in PMHs from Chac1+/+ and Chac1−/− mice treated with 20 mM APAP for 3 h. GAPDH was used as an internal reference. The statistical chart shows the relative expression levels of S-glutathionylated proteins (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 mice, t-test). (G) Western blot analysis of S-glutathionylated proteins in PMHs infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-CHAC1 at multiplicities of infection (MOI) of 0.1, 1, 2.5, 5, and 10 for 12 h and, followed by treatment with 20 mM APAP for 6 h. GAPDH was used as an internal reference. (H) Quantification of GSH and GSSG levels and ratio of GSSG/GSH in PMHs infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-CHAC1 adenovirus at MOIs of 1 and 10 for 12 h, followed by treatment with 20 mM APAP for 6 h (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 4 biologically independent samples, t-test). (I) PMHs isolated from Chac1+/+ and Chac1−/− mice were treated with 20 mM APAP for 12 h. Relative cell viability was measured using the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay and normalized by DMEM control (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 5 biologically independent samples, t-test). (J) MDA levels in PMHs infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-CHAC1 adenovirus at MOI = 10 for 36 h and then treated with 20 mM APAP for 12 h (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biologically independent samples, t-test). (K) PMHs from Chac1+/+ and Chac1−/− mice were treated with 20 mM APAP for 12 h. Representative images of C11 Bodipy 581/591 fluorescence. Red fluorescence represents non-lipid oxidation, and green fluorescence represents lipid oxidation. The statistical chart shows the ratio of green to red fluorescence (Scale bars = 200 μm, data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biologically independent samples, t-test).

APAP, acetaminophen; AILI, APAP-induced liver injury; PMH, primary mouse hepatocyte; GSH, glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; MDA, determination of malondialdehyde; Chac1−/−, Chac1-deficient; Chac1+/+, wild-type controls.

To investigate the correlation among glutathione pools, protein-SSG, and glutathione depletion-induced ferroptosis in PMHs, we generated Chac1-deficient mice (Chac1−/−) and their littermate wild-type controls (Chac1+/+) (Fig. S2B–C), isolated and cultured PMHs from Chac1+/+ and Chac1−/− mice. The mRNA expression of Chac1 was induced in a time-dependent manner by APAP in the PMHs from Chac1+/+ mice, but not in those from Chac1−/− mice (Fig. S2D). Deletion of Chac1 in PMHs increased SSG protein levels (Fig. 2F). Next, we studied the effects of CHAC1 on glutathione pools and protein-SSGs in wild-type PMHs using Ad-CHAC1 or Ad-GFP adenoviruses. After 12 or 36 h of infection (Fig. 2G and Fig. S2E), the PMHs were treated with or without 20 mM APAP for 6 h. As a result, CHAC1 overexpression dose-dependently reduced protein-SSG in APAP-challenged PMHs (Fig. 2G and Fig. S2E).

Meanwhile, in the Ad-GFP control group, APAP treatment resulted in GSH depletion, elevated GSSG levels, and an increased GSSG/GSH ratio (Fig. 2H). In contrast, CHAC1 overexpression led to a reduction in both GSH and GSSG, without decreasing the GSSG/GSH ratio (Fig. 2H). The GSSG/GSH ratio, a key indicator of cellular oxidative stress, is typically associated with protein-SSG formation. Our findings suggest that during glutathione depletion-induced ferroptosis, the CHAC1-mediated reduction in protein-SSG was due to decreased GSH and GSSG availability, rather than changes in the GSSG/GSH ratio.

Next, we assessed the effects of the CHAC1-mediated glutathione depletion and protein-SSG reduction on APAP-induced hepatotoxicity and ferroptosis. The viability of PMHs was significantly increased upon APAP challenge in the Chac1−/− group compared with that in the Chac1+/+ group (Fig. 2I). Upon APAP challenge, overexpression of CHAC1 increased the levels of the lipid peroxidation product malondialdehyde (MDA) in Chac1−/− PMHs (Fig. 2J). BODIPY 581/591C11 (BODIPY) probes are commonly used to detect lipid peroxidation in living cells. Upon oxidation, the fluorescence of the probe shifts from red to green. Consistently, lipid peroxidation was markedly decreased in Chac1−/− PMHs compared with that in Chac1+/+ PMHs (Fig. 2K).

Collectively, the decreased glutathione pools caused by CHAC1 reduced protein-SSG levels and aggravated APAP-induced hepatotoxicity and ferroptosis in primary mouse hepatocytes.

3.3. Decreased glutathione pools by CHAC1 reduces protein-SSG and aggravates APAP-induced hepatotoxicity and ferroptosis in APAP-injured mice liver

To investigate the role of the CHAC1-mediated glutathione depletion and protein-SSG reduction in glutathione deprivation-induced ferroptosis in vivo, we administered APAP to Chac1+/+ and Chac1−/− mice. Both mice exhibited normal growth and development. The mRNA level of Chac1 in the liver was induced by APAP in Chac1+/+ mice, but not in Chac1−/− mice (Fig. S3A). We also rescued CHAC1 expression in Chac1−/− mice by injecting Adenovirus (Ad)-CHAC1 via the tail vein. We found that the levels of GSH and GSSG did not differ between Chac1−/−and Chac1+/+ mice in terms of homeostatic status. Upon APAP overdose, the concentrations of both GSH and GSSG in the liver markedly decreased after 2 h and then started to increase in mice of both genotypes (Fig. 3A and B and Fig. S3B). Notably, the level of GSH was restored faster in Chac1−/− mice, than in Chac1+/+ mice, after 6 h (Fig. 3A). As predicted, although the overall protein-SSG in the liver tissues of mice of both genotypes decreased after 2 h, it increased 6 h after APAP administration (Fig. 3C and Fig. S3C). At 6 h, the levels of protein-SSG in the livers of Chac1−/− mice were higher than those in Chac1+/+ mice (Fig. 3C), suggesting that CHAC1 deficiency accelerated the recovery of liver glutathione depletion and increased liver protein-SSG levels in AILI mice. Moreover, the concentrations of glutathione and the levels of protein-SSG in the liver were decreased by the overexpression of CHAC1 in Chac1−/− mice (Fig. 3A–D), suggesting that CHAC1 overexpression retarded the recovery of liver glutathione depletion and reduced liver protein-SSG in AILI mice.

Fig. 3.

Decreased glutathione pools by CHAC1 reduces protein-SSG and aggravates APAP-induced hepatotoxicity and ferroptosis in APAP-injured mice liver. (A) Quantification of GSH in the liver tissues of Chac1+/+ Ad-GFP, Chac1−/− Ad-GFP, and Chac1−/− Ad-CHAC1 mice treated with saline or 300 mg/kg APAP for 2 and 6 h (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 and 5 mice/group, t-test). (B) Quantification of GSSG in the liver tissues of Chac1+/+ Ad-GFP, Chac1−/− Ad-GFP, and Chac1−/− Ad-CHAC1 mice treated with saline or 300 mg/kg APAP for 2 and 6 h (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 and 5 mice/group, t-test). (C) Western blot analysis of S-glutathionylated proteins in the liver tissues of Chac1+/+ Ad-GFP and Chac1−/− Ad-GFP mice treated with 300 mg/kg APAP for 2 and 6 h. GAPDH was used as an internal reference, followed by quantification of relative levels of S-glutathionylated proteins after 6 h of APAP treatment (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 mice/group, t-test). (D) Western blot analysis of S-glutathionylated proteins and CHAC1-FLAG protein in the liver tissues of Chac1−/− Ad-GFP and Chac1−/− Ad-CHAC1 mice treated with 300 mg/kg APAP for 6 h. GAPDH was used as an internal reference. Statistical chart shows the relative expression levels of S-glutathionylated proteins 6 h after APAP treatment (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 4 mice/group, t-test). (E) Serum levels of ALT and AST in Chac1+/+ Ad-GFP, Chac1−/− Ad-GFP, and Chac1−/− Ad-CHAC1 mice treated with 300 mg/kg APAP for 6 h (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 5 mice/group, t-test). (F) H&E staining, 4-HNE protein adduct staining in liver tissues of Chac1+/+ Ad-GFP, Chac1−/− Ad-GFP and Chac1−/− Ad-CHAC1 mice treated with 300 mg/kg APAP for 6 h. Scale bars = 200 μm. The area of liver injury and immunohistochemical score for 4-HNE protein adduct staining were quantified (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 5 mice/group, t-test). APAP, acetaminophen; GSH, glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; H&E, haematoxylin and eosin; Chac1−/−, Chac1-deficient; Chac1+/+, wild-type controls.

Next, we assessed the effects of the CHAC1-mediated glutathione depletion and protein-SSG reduction on APAP-induced hepatotoxicity and ferroptosis. As a result, the serum levels of ALT and AST were significantly decreased in Chac1−/− mice than those in Chac1+/+ mice following the administration of 300 mg/kg APAP for 6 h (Fig. 3E). Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) showed that Chac1 deficiency markedly attenuated APAP overdose-induced centrilobular liver injury (Fig. 3F). We tested whether CHAC1 contributed to hepatocyte ferroptosis. Staining with 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), a reliable indicator of endogenous lipid peroxidation in vivo, revealed that compared with Chac1+/+ mice, Chac1−/− mice showed a clear reduction in 4-HNE protein adduct-positive cells in liver histological sections (Fig. 3F). Further, we found that the improvement of hepatotoxicity in Chac1−/− mice upon APAP challenge could be retarded by CHAC1 overexpression (Fig. 3E and F).

Together, the depletion of glutathione pools induced by CHAC1 reduced protein-SSG levels and exacerbated APAP-induced hepatotoxicity and ferroptosis in APAP-injured mouse livers.

3.4. Redox proteomic analysis reveals that the S-glutathionylation of Cys90 on ARF6 is regulated by CHAC1 in ferroptotic PMHs induced by APAP

To identify the S-glutathionylated proteins involved in APAP-induced hepatocyte ferroptosis in the presence and absence of CHAC1 overexpression, we conducted a quantitative redox proteomic analysis. PMHs for glutathionylomic analysis were infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-CHAC1 for 36 h and then challenged with 20 mM APAP for 3 h (Fig. 4A). We identified 1105 unique glutathionylated peptides from 482 proteins (Fig. S4A). Oxidative state induced by APAP challenge markedly enhanced (Fold change ≥1.2, P < 0.05) cysteine S-glutathionylation in both Ad-GFP and Ad-CHAC1 groups (Fig. 4B and Fig. S4B). Compared with the Ad-GFP group, CHAC1 overexpression markedly decreased cysteine S-glutathionylation, especially after APAP treatment (Fig. 4C), which was consistent with the above Western blot data. A total of 221 cysteine sites were found to undergo increased S-glutathionylation in response to APAP, while simultaneously reduced by CHAC1 overexpression (Fig. 4D and E). GO analysis revealed that these proteins were enriched in biological processes, such as lipid metabolism, mitochondrial respiratory chain, and arachidonic acid metabolism, which are all potentially relevant to hepatotoxicity and ferroptosis (Fig. S4C).

Fig. 4.

Redox proteomic analysis reveals that the S-glutathionylation of Cys90 on ARF6 is regulated by CHAC1 in ferroptotic PMHs induced by APAP. (A) Flowchart outlining the key experimental procedures for proteomic analysis of S-glutathionylation. (B) Scatter plot illustrating the distribution of differential modification sites, sorted by the ratio of Ad-GFP + APAP/Ad-GFP. Red dots indicating up-regulation of significant differences, blue dots indicating down-regulation of significant differences, and grey dots indicating no significant differences (CV < 0.1, fold change ≥1.2). (C) Scatter plot showing the distribution of differential modification sites, sorted by the ratio of Ad-CHAC1 + APAP/Ad-GFP + APAP. Red dots indicating up-regulation of significant differences, blue dots indicating down-regulation of significant differences and grey dots indicating no significant differences (CV < 0.1, fold change ≥1.2). (D) Venn diagram showing differentially modified sites under both APAP stimulation and CHAC1 overexpression (Fold change ≥1.2). (E) The heat map illustrating the union of differential modification sites in Ad-GFP, Ad-GFP + APAP, Ad-CHAC1, and Ad-CHAC1 + APAP comparison groups (CV < 0.1, fold change ≥1.2). (F) Scatter plot showing differentially modified sites under both APAP stimulation and CHAC1 overexpression; the order was sorted by the ratio of Ad-GFP + APAP/Ad-GFP (CV < 0.1, fold change ≥1.2). (G) Two-stage mass spectrometry of the glutathionylated peptide from ARF6 in PMHs. The secondary mass spectrum shows fragment ion information of the ARF6 C90 peptide segment. (H) Histogram showing the relative modification abundance of ARF6 C90 in different treatment groups, with glutathionylated peptides identified and quantified by LC-MS/MS (All values were normalized by the mean of the AdGFP-CON group, data are mean ± SEM of n = 2 biologically independent samples). (I) IP assay showing the expression of S-glutathionylated ARF6 in 293T cells overexpressing Myc-tagged ARF6. Whole cell lysates were used to confirm the expression of ARF6. (J) Two-stage mass spectrometry of the glutathionylated peptide from ARF6 in 293T cells overexpressing Myc-tagged ARF6. The secondary mass spectrum shows fragment ion information of the ARF6 C90 peptide segment. PMH, primary mouse hepatocyte; IP, immunoprecipitation.

Among the proteins showing decreased S-glutathionylation due to CHAC1 overexpression, we identified ARF6 as one of the top five proteins upregulated by APAP treatment in PMHs (Fig. 4F). ARF6 is a member of the small GTPase ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF) family. Redox proteomic analysis revealed that ARF6 is glutathionylated at Cys90 (Fig. 4G), which was increased upon APAP treatment in Ad-GFP PMHs, and effect blunted in Ad-CHAC1 PMHs (Fig. 4H).

The protein sequence of ARF6 is completely identical between humans and mice. We collected lysates from 293T cells overexpressing Myc-tagged ARF6 and performed an immunoprecipitation using an anti-Myc antibody to pull down ARF6. Western blot analysis with anti-glutathione revealed that ARF6 could be S-glutathionylated (Fig. 4I). After separation by SDS-PAGE, the ARF6-myc band was excised, digested, and analyzed by LC–MS/MS. We identified a peptide at m/z 686.66 corresponding to the triply charged peptide (HYYTGTQGLIFVVDCADR), which was converted into a peptide at m/z 788.35, corresponding to the triply charged glutathionylated form (Fig. 4J). To further validate the peptide's identity, fragmentation analysis produced ions that matched the predicted b and y ions, confirming the glutathionylation of Cys90 (Fig. 4J).

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that ARF6 undergoes S-glutathionylation at Cys90 in both mouse and human cells.

3.5. ARF6 serves the protective role in ferroptosis

A few reports mentioned that ARF6 suppressed ferroptosis in pancreatic and gastric cancer cells [32,33]. To determine the role of ARF6 in APAP-induced hepatocyte ferroptosis, we knocked down Arf6 in PMHs using siRNA and treated the cells with APAP (Fig. S5A). Both CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability assays and Live & Dead cell staining assays revealed the aggravated cell death following the Arf6 knock down in PMHs exposed to APAP overdose (Fig. 5A and B). Lipid peroxidation was markedly increased by Arf6 siRNA compared to that with control siRNA (Fig. 5C and Fig. S5B). We then detected the labile iron pool using the FerroOrange probe. Arf6 knockdown significantly increased intracellular Fe2+ levels in PMHs upon APAP challenge (Fig. 5D and Fig. S5C). These results suggest that ARF6 plays a protective role in APAP-induced hepatocyte ferroptosis.

Fig. 5.

ARF6 serves the protective role in ferroptosis. (A) PMHs were transfected with Arf6 siRNA and treated with 20 mM APAP. Relative cell viability was measured using the CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay and normalized by DMEM control (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 6 biologically independent samples, one-way ANOVA). (B) PMHs were transfected with Arf6 siRNA and treated with 20 mM APAP. Representative images of calcein-AM/PI live/dead cell staining (Green: live cells; Red: dead cells, Scale bars = 200 μm). Followed by ratio of dead to living cells (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biologically independent samples, one-way ANOVA). (C) Representative images of the C11 Bodipy 581/591 fluorescent probe used to detect the formation of lipid peroxides (Red: non-oxidized lipids; Green: oxidized lipids; Scale bars = 200 μm). The statistical chart shows the ratio of green to red fluorescence (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biologically independent samples, one-way ANOVA). (D) Representative images of the FerroOrange fluorescent probe used to detect labile ferrous ions (Red: FerroOrange; Blue: DAPI; Scale bars = 200 μm). The statistical chart shows the relative Fe2+ fluorescence intensity (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biologically independent samples, one-way ANOVA). APAP, acetaminophen.

3.6. S-glutathionylation of ARF6 at Cys90 enhances its trafficking to lysosomes, resulting in reduced plasma membrane localization of TFRC and diminished transferrin uptake

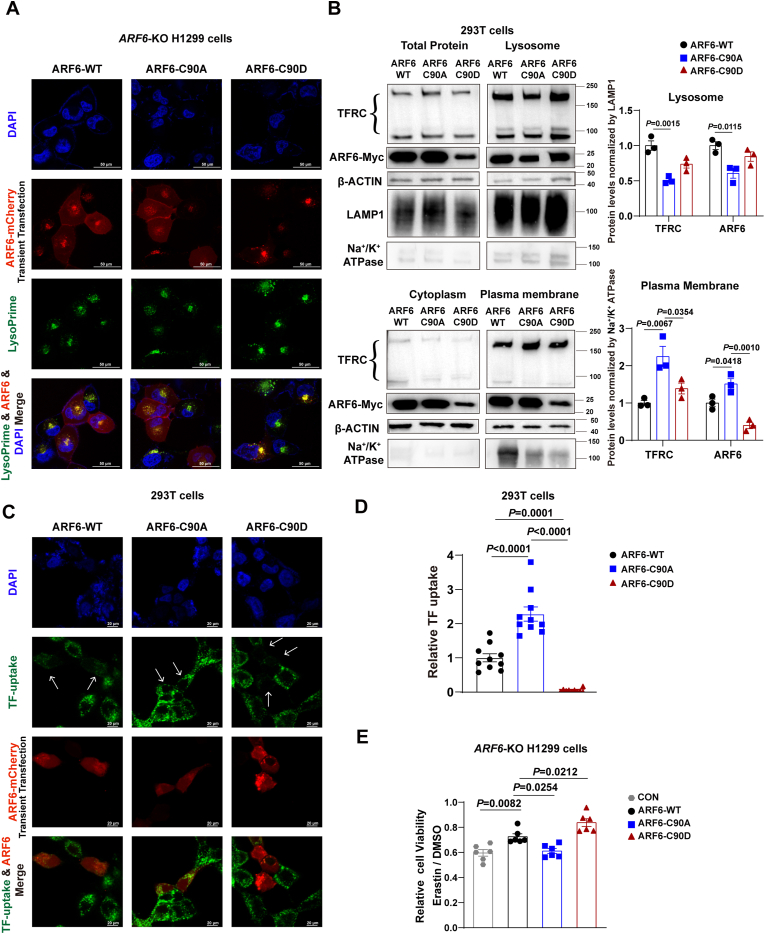

To investigate the impact of S-glutathionylation of ARF6 at Cys90 on its expression or subcellular localization, we constructed the plasmids encoding ARF6-WT-mCherry, ARF6-C90A-mCherry mutants (mimicking the unglutathionylated form of ARF6), and ARF6-C90D-mCherry mutants (mimicking the glutathionylated form of ARF6 [[34], [35], [36]]. These plasmids were transfected into ARF6 knockout H1299 cells and Arf6 knockout Hepa1-6 cells (Fig. S6A–B). We observed that ARF6-C90A-mCherry accumulated less, while ARF6-C90D-mCherry accumulated more in the lysosomes indicated by LysoPrime probe staining (Fig. 6A and Fig. S6C).

Fig. 6.

S-glutathionylation of ARF6 at Cys90 enhances its trafficking to lysosomes, resulting in reduced plasma membrane localization of TFRC and diminished transferrin uptake. (A) Representative fluorescence images of ARF6-KO H1299 cells expressing ARF6-WT-mCherry, ARF6-C90A-mCherry, or ARF6-C90D-mCherry (Blue: DAPI, Red: mCherry, Green: LysoPrime probe. Scale bars = 50 μm). (B) Subcellular fractionation of HEK293T cells expressing ARF6-WT-Myc, ARF6-C90A-Myc, or ARF6-C90D-Myc. Western blot analysis of TFRC and ARF6 protein levels in total cell lysates, lysosomal, cytoplasmic and plasma membrane fractions. β-ACTIN, LAMP1, Na+/K+-ATPase were used as internal references. Relative TFRC and ARF6 protein levels in those fractions were quantified (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biologically independent experiments, one-way ANOVA). (C) Representative fluorescence images of 293T cells expressing ARF6-WT-Myc, ARF6-C90A-Myc, or ARF6-C90D-Myc. (Blue: DAPI, Green: Alexa Fluor® 647-labeled transferrin probe, Red, ARF6-mCherry. Scale bars = 20 μm). (D) Relative transferrin uptake (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 10 biologically independent samples, one-way ANOVA). (E) Relative cell viability of ARF6-KO H1299 cells treated with erastin (10 μM) for 24 h, normalized by DMSO control, as measured by the CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 6 biologically independent samples, t-test). TFRC, transferrin receptor.

Considering the internalization and recycling of TFRC is a classic example of clathrin-dependent receptor-mediated endocytosis regulated by ARF6, we hypothesized that ARF6 glutathionylation might affect TFRC localization and transferrin uptake. We isolated lysosomal and plasma membrane fractions from 293T cells transfected with ARF6-WT-Myc, ARF6-C90A-Myc, and ARF6-C90D-Myc. Compared to the ARF6-WT group, ARF6-C90A-overexpressing cells exhibited decreased TFRC and ARF6 levels in the lysosome, with an increase in both proteins at the plasma membrane. In contrast, ARF6-C90D-overexpressing cells showed increased TFRC and ARF6 levels in the lysosome and decreased levels at the plasma membrane (Fig. 6B). The identity of the TFRC bands was confirmed using TFRC siRNA (Fig. S6D). Further, consistent with the findings in ARF6 knockout H1299 cells and Arf6 knockout Hepa1-6 cells, we observed more ARF6-C90A-mCherry localized at the plasma membrane and more ARF6-C90D-mCherry in the lysosomes in 293T cells (Fig. 6C).

The availability of TFRC at the plasma membrane may affect transferrin uptake. To test this, we measured transferrin uptake using Alexa Fluor® 647-labeled transferrin. As a result, compared to the untransfected cells in the same microscopic field, cells transfected with ARF6 WT took up less transferrin. Consistent with the observed localization patterns, ARF6-C90A-overexpressing cells showed increased transferrin uptake, while ARF6-C90D-overexpressing cells took up less transferrin compared with the ARF6-WT group (Fig. 6C and D).

Considering that transferrin uptake may influence labile iron pools and consequently affect ferroptosis, we examined the effect of ARF6-Cys90-SSG on ferroptosis induced by erastin. Our results showed that overexpression of ARF6-C90A exacerbated, while overexpression of ARF6-C90D mitigated, erastin-induced ferroptosis in ARF6 knockout H1299 cells (Fig. 6E). To further observe the molecular alterations caused by ARF6 glutathionylation at Cys90, we performed RNA-seq using ARF6-myc (WT) or ARF6-C90A-myc transfected H1299 cells, with or without erastin treatment. Using GO or KEGG pathway enrichment analyses, we found that the 443 genes upregulated only in the ARF6-C90A group but not in the WT group were enriched in cholesterol biosynthesis, lipid metabolic process, autophagy, and ferroptosis. However, the 853 genes downregulated only in the ARF6-C90A group but not in the WT group, as well as 720 genes upregulated only in WT group but not in the ARF6-C90A group, were mainly involved in RNA splicing, cell division, cell cycle, DNA repair, and vesicle organization (Fig. S6E and S6F).

Collectively, S-glutathionylation of ARF6 at Cys90 facilitates its trafficking to lysosomes, resulting in reduced plasma membrane localization of TFRC, diminished transferrin uptake, and attenuated ferroptosis induced by glutathione depletion.

3.7. TFRC mediates the exacerbation of APAP-induced hepatocyte ferroptosis caused by CHAC1 upregulation

To elucidate the crucial role of TFRC-mediated transferrin uptake in CHAC1-exacerbated hepatocyte ferroptosis, we conducted transferrin uptake assays. Our results demonstrated that Chac1−/− PMHs exhibited significantly reduced transferrin probe uptake compared to wild-type PMHs following APAP treatment (Fig. 7A). In contrast, overexpression of CHAC1 led to an increase in transferrin uptake compared to control cells infected with the control-GFP virus (Fig. 7B). Meanwhile, CHAC1 overexpression increased intracellular Fe2+ levels in PMHs upon APAP challenge (Fig. 7C). Moreover, the knockdown of Tfrc attenuated the increased cell death induced by CHAC1 overexpression following APAP treatment (Fig. 7D and Fig. S7A–B).

Fig. 7.

TFRC mediates the exacerbation of APAP-induced hepatocyte ferroptosis caused by CHAC1 upregulation. (A) Representative fluorescence images showing transferrin uptake in Chac1+/+ and Chac1−/− PMHs treated with 20 mM APAP. (Blue: DAPI, Green: Alexa Fluor® 647-labeled transferrin probe. Scale bars = 20 μm). The statistical chart shows the relative transferrin uptake (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 10 biologically independent samples, one-way ANOVA). (B) Representative fluorescence images showing transferrin uptake in PMHs infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-CHAC1 adenoviruses (MOI = 10), followed by treatment with 20 mM APAP. (Red: Alexa Fluor® 546-labeled transferrin probe, Blue: DAPI, Scale bars = 50 μm).The statistical chart shows the relative transferrin uptake (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 10 biologically independent samples, one-way ANOVA). (C) Representative fluorescence images showing Fe2+ in PMHs infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-CHAC1 adenoviruses (MOI = 10), followed by treatment with or without 20 mM APAP (Red: FerroOrange fluorescent probe, Green: GFP, Scale bars = 200 μm). The statistical chart shows the relative Fe2+ fluorescence intensity (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biologically independent samples, t-test). (D) PMHs were transfected with NC siRNA or Tfrc siRNA, followed by infection with Ad-GFP or Ad-CHAC1 adenoviruses (MOI = 10) and treatment with 20 mM APAP. Representative images of PI dead cell staining (Green: GFP, Red: dead cells, Scale bars = 100 μm). The statistical chart shows the ratio of dead cells (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 4 biologically independent samples, t-test). (E) RT-qPCR analysis of Tfrc mRNA levels in WT mice transfected with GalNAc-siNC or GalNAc-siTfrc, followed by treatment with 300 mg/kg APAP for 6 h, normalized by Saline control (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 and 6 mice/group, one-way ANOVA). (F) Western blot analysis of TFRC proteins in WT mice transfected with GalNAc-siNC or GalNAc-siTfrc and treated with 300 mg/kg APAP for 6 h. GAPDH was used as an internal reference. Followed by quantification of relative levels of TFRC, normalized by saline control (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 and 6 mice/group, one-way ANOVA). (G) Serum levels of ALT in WT mice transfected with GalNAc-siNC or GalNAc-siTfrc and treated with 300 mg/kg APAP for 6 h (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 and 6 mice/group, one-way ANOVA). (H) Serum levels of AST in WT mice transfected with GalNAc-siNC or GalNAc-siTfrc and treated with 300 mg/kg APAP for 6 h (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 and 6 mice/group, one-way ANOVA). (I) H&E staining, in liver tissues of WT mice transfected with GalNAc-siNC or GalNAc-siTfrc and treated with 300 mg/kg APAP for 6 h. The area of liver injury were quantified (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 and 6 mice/group, one-way ANOVA). (J) Western blot analysis of 4-HNE proteins adduct levels in WT mice transfected with GalNAc-siNC or GalNAc-siTfrc and treated with 300 mg/kg APAP for 6 h. GAPDH was used as an internal reference. Followed by quantification of relative levels of 4-HNE proteins adduct, normalized by saline control (Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 and 6 mice/group, one-way ANOVA). PMH, primary mouse hepatocyte; APAP, acetaminophen; TFRC, transferrin receptor.

To investigate the therapeutic potential of targeting TFRC in treating ferroptosis induced by glutathione depletion, we tried to knock down TFRC in hepatocytes using an APAP-induced liver injury mouse model. Given that N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) specifically binds to the asialoglycoprotein receptor on hepatocytes, GalNAc-conjugated siRNA technology is by far the most successful approach for delivering siRNAs to treat liver-related diseases [37]. C57BL/6 mice pretreated with Tfrc-targeted GalNAc siRNA (GalNAc-siTfrc) or control GalNAc-siNC via subcutaneous injection were challenged with APAP (300 mg/kg) for 6 h. The efficiency of TFRC knockdown in the liver was confirmed by a significant reduction in both mRNA and protein levels of TFRC (Fig. 7E and F). Our results demonstrated that GalNAc-siTfrc pretreatment significantly attenuated APAP-induced liver injury, as evidenced by reduced serum ALT (Fig. 7G) and AST (Fig. 7H) levels, decreased areas of liver injury (Fig. 7I), and lower levels of 4-HNE protein adducts in the liver compared to the GalNAc-siNC group (Fig. 7J).

Together, TFRC mediates the exacerbation of APAP-induced hepatocyte ferroptosis caused by CHAC1 upregulation, and targeting TFRC using GalNAc-siTfrc represents a promising therapeutic strategy for mitigating APAP-induced liver injury and ferroptosis induced by glutathione depletion in vivo.

4. Discussion

Ferroptosis is one of the most critical biological events caused by glutathione deficiency. Protein S-glutathionylation is closely linked to the redox state and cellular glutathione pools. In the present study, we investigated the involvement of protein S-glutathionylation in ferroptosis induced by glutathione depletion using both in vivo and in vitro models, including erastin-induced ferroptosis in multiple cell lines and APAP-triggered ferroptosis in hepatocytes. Our findings clarify that the reduction in protein-SSG may underlie the mechanism by which glutathione deficiency accelerates ferroptosis.

Consistent with previous studies identifying CHAC1, which mediates glutathione degradation, as one of the most significantly upregulated genes during ferroptosis [3,20], we observed a dramatic upregulation of CHAC1 in both erastin-treated cell lines and APAP-challenged hepatocytes. Previous studies have shown that ATF4 and ATF3 bind to two conserved DNA elements (ATF/CRE and CARE) in the CHAC1 promoter to regulate its expression. In addition, the transcriptional regulation of CHAC1 is also modulated by several other transcription factors, including NRF2, p63, STAT3, FOXO1, and p53 [38,39]. The induction of CHAC1 at the transcriptional level by erastin or APAP may be associated with the above mechanisms. In the context of glutathione depletion-induced ferroptosis, CHAC1—an acute-phase response protein regulated by the ATF3/ATF4 transcription factor—exhibits rapid and dramatic upregulation, while glutathione levels and protein-SSG decline sharply. This upregulation of pro-death genes, including CHAC1, occurs when cellular priorities shift from survival to death, suggesting that our proposed mechanism may specifically explain the toxicological basis of ferroptosis induced by APAP overdose or erastin, as well as late-stage ferroptosis triggered by glutathione depletion.

The role of CHAC1 in ferroptosis has been previously explored. CHAC1 enhances cystine-starvation-induced ferroptosis through degradation of GSH and activated GCN2-eIF2α-ATF4 pathway in human triple negative breast cancer cells [38]. CHAC1 facilitates ferroptosis by accelerating GSH deprivation in retinal pigment epithelial cells with oxidative damage [40]. Dihydroartemisinin effectively induces ferroptosis in primary liver cancer cells by upregulating CHAC1 expression [41]. Anti-CHAC1 exosomes from adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells inhibit neuronal ferroptosis and alleviate cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice [42]. CHAC1 decreased cell viability and increased the sensitivity of prostate cancer cells to docetaxel by inducing ferroptosis [43]. We and other groups have reported that ferroptosis is involved in APAP-induced hepatotoxicity [8,28,29]. The APAP-induced liver injury mouse model is a valid in vivo model of ferroptosis. In this study, except for erastin-induced ferroptosis, we verified the role of CHAC1 in accelerating ferroptosis in an AILI mouse model.

The underlying mechanisms by which CHAC1 promotes ferroptosis have previously been limited to its role in enhancing GSH degradation. Our study provides new insights into the consequences of reduced glutathione levels induced by CHAC1 upregulation. Specifically, CHAC1 decreases the total glutathione pool (GSH + GSSG), which closely coordinates with protein-SSG levels and subsequently influences ferroptosis triggered by glutathione depletion. Under cellular oxidative status, protein-SSG formation can occur either when GSSG exchanges thiol groups with protein cysteine thiolate groups or when already oxidized protein sulfenic acid groups react with GSH [44]. Although CHAC1 is not the enzyme responsible for catalyzing deglutathionylation, our findings show that CHAC1 upregulation significantly reduces protein-SSG levels. This reduction in protein-SSG may represent a key mechanism through which glutathione deficiency promotes ferroptosis. We propose that the overall availability of glutathione, encompassing both GSH and GSSG, plays a critical role in determining the extent of protein S-glutathionylation. By reducing the total glutathione pool, CHAC1 diminishes the substrate availability for protein-SSG formation, thereby contributing to ferroptosis.

Although a recent study reported that glutaredoxin (GLRX) attenuated glutathione levels via deglutathionylation of deubiquitinase Otub1 and subsequent destabilization of cystine/glutamate transporter SLC7A11 [45], the precise role of protein-SSG in ferroptosis remains unclear. Few studies have focused on the protein-SSG in APAP-induced hepatotoxicity. Yang et al. observed that glutathionylated regions were present in the liver sections of mice challenged with APAP [46]. Chan et al. performed a proteome-wide screening of HepaRG cells treated with APAP and characterised 898 glutathionylated peptides corresponding to 588 proteins. Glutathionylated proteins are involved in the well-known toxic effects of APAP, including energy metabolism, oxidative stress, cytosolic calcium, and mitochondrial dysfunction [47]. Here, we further demonstrated aberrant protein glutathionylation upon APAP treatment in primary mouse hepatocytes, which could better preserve hepatocyte features. We identified 1105 glutathionylated peptides from 482 proteins. Consistent with the data of Chan et al. in hepatic cell lines [47], many proteins related to mitochondrial function, lipid metabolism, and energy metabolism were glutathionylated in APAP-challenged PMHs. In this study, we demonstrated that S-glutathionylation plays a crucial role in maintaining the protective function of ARF6 in ferroptosis. The reduction in glutathione pools caused by CHAC1 decreased the level of ARF6 S-glutathionylation at Cys90, thereby impairing the protective effect of ARF6 in ferroptosis induced by glutathione depletion.

ARF6 activates lipid-modifying enzymes (PIP5-kinase and phospholipase D), stimulates actin polymerization, participates in both clathrin-dependent and clathrin-independent endocytosis, and is involved in the recycling of endosomal cargo back to the membrane [25]. Numerous studies have shown that the activation of ARF6 is essential for cancer cell invasion, metastasis, and proliferation. Overexpression of ARF6 has been observed in several cancers and may serve as a promising therapeutic target in cancer treatment [48,49]. Our data suggest that ARF6 suppresses APAP-induced ferroptosis in PMHs, which is consistent with previous studies showing that ARF6 suppresses ferroptosis in pancreatic and gastric cancer cells [32,33]. Previous studies have shown that ARF6 undergoes myristoylation, a post-translational modification essential for its intracellular localization and endocytic function [50,51]. In the present study, we observed an additional posttranslational modification of ARF6: glutathionylation. Glutathionylation of other Ras family members has been reported. Pimentel et al. demonstrated that mechanical strain induces ROS-dependent S-glutathionylation of Ras at Cys118, activating the Raf/Mek/Erk pathway and ultimately leading to hypertrophy in cardiac myocytes [52].

ARF6 plays a crucial role in the endocytosis and recycling of the transferrin receptor (TFRC). On the plasma membrane, TFRC binds to two Fe3+-laden transferrins (TFs), which then concentrate in clathrin-coated pits. Upon endocytosis, the acidic environment of the endosomes triggers the release of iron. The Fe3+ is subsequently reduced to Fe2+, after which it is transported into the cytoplasm to form the labile iron pool. From early endosomes, the TF-TFRC complexes are either directed to the late endosome/lysosome for degradation, or recycled back to the plasma membrane, either directly or via the endocytic recycling compartment. Once the TFRC-TF complex is returned to the cell surface, iron-free transferrin is released from the TFRC at the neutral extracellular pH, allowing the TFRC to bind and internalize new transferrin [53,54]. ARF6 is a Ras-related small GTPase that cycles between an active form (GTP-ARF6) and an inactive form (GDP-ARF6) [55,56]. Previous studies have shown that overexpression of EFA6A, an ARF6-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factor, inhibits transferrin uptake [57]. Additionally, ectopic expression of a constitutively active form of ARF6 (ARF6 Q67L) also inhibits transferrin internalization [58]. Coherently, in the context of our study, cells transfected with ARF6 WT (wild type) vectors exhibited reduced transferrin uptake compared to untransfected cells (Fig. 6C), which may represent a key mechanism underlying the protective role of ARF6 in ferroptosis.

The protein sequence of ARF6 is 100 % identical between humans and mice, and it contains two cysteine residues: Cys90 and Cys155. When we assessed the glutathionylation of immunoprecipitated ARF6 from 293T cells overexpressing ARF6-Myc, only the glutathionylation of Cys90 was detectable. Therefore, we focused on investigating the S-glutathionylation of ARF6 at Cys90 rather than at Cys155. In our study, we mutated Cys90 to Ala (A) to mimic the absence of glutathionylation on ARF6. Castro-Torres et al. mutated AtcTPI-Cys13 to aspartic acid (D), which mimics the irreversible chemical modification of cysteine to sulfinic acid [35]. Similarly, Permyakov et al. mutated recoverin-Cys39 to Asp (D), mimicking the oxidative conversion of Cys39 to sulfenic, sulfinic, or sulfonic acids [34]. Yi et al. demonstrated that overexpression of the PRMT5-C42D mutant, a mimic of glutathionylated PRMT5, inhibited cell proliferation [36]. Inspired by these studies, we also mutated Cys90 to Asp (D) to mimic the glutathionylation on ARF6. Using fluorescent fusion protein plasmids, we observed that ARF6, when mimicking glutathionylation, traffics more readily to the lysosome. Once in the lysosome, ARF6 may undergo further degradation. Our data showed that the C90D mutant reduced TFRC expression on the plasma membrane, decreased transferrin uptake, and promoted the protective role of ARF6 in ferroptosis. In contrast, the ARF6 C90A mutant, mimicking the unglutathionylated form, enhanced TFRC expression on the plasma membrane, increased transferrin uptake, and attenuated the protective role of ARF6 in ferroptosis.

In conclusion, protein S-glutathionylation plays a crucial role in conferring cellular resistance to ferroptosis induced by glutathione depletion. This study offers new insights into how glutathione deficiency disrupts protein oxidative post-translational modifications and enhances transferrin uptake, thereby promoting ferroptosis. Targeting TFRC using GalNAc-siTfrc can be a promising therapeutic strategy for mitigating ferroptosis induced by glutathione depletion.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yi Ju: Visualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Yuting Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Investigation. Xiaolin Tian: Visualization, Methodology. Nanbin Zhu: Visualization, Investigation, Formal analysis. Yufan Zheng: Writing – review & editing. Yiming Qiao: Investigation. Tao Yang: Investigation. Baolin Niu: Investigation. Xiaoyun Li: Investigation. Liu Yu: Investigation. Zhuolin Liu: Methodology. Yixuan Wu: Investigation. Yang Zhi: Investigation. Yinuo Dong: Investigation. Qingling Xu: Investigation. Xiaoming Yang: Resources. Xuening Wang: Resources. Xiaokai Wang: Resources, Funding acquisition. Haiteng Deng: Methodology. Yimin Mao: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Xiaobo Li: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Resources, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

5. Data access statement

-

F095