Abstract

The effects of chemical induction of latent Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) with 12-O-tetradecanoyl phorbol-13-acetate (TPA) and n-butyrate on cell viability and induction of latent EBV in Raji and X50-7 B lymphocytes, indicated by expression of the diffuse component of the EBV early antigen (EA-D), were measured by visual immunofluorescence microscopy (of both viable and nonviable cells) and fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) flow cytometry (of viable cells only). Cell viability at 4 days decreased moderately for treated Raji cells (9 to 37%, compared to 55 to 69% for untreated cells) and markedly for X50-7 cells (1-32% compared to 35-44% in untreated cells). The highest EA-D levels in viable cells occurred in Raji cells treated with both TPA and n-butyrate and untreated X50-7 cells. TPA and n-butyrate acted synergistically to induce latent EBV, resulting in increased levels of EA-D production in Raji cells and cell death in X50-7 cells. Methodological differences including the ability to detect antigen in only viable cells by FACS flow cytometry accounted for the higher levels of EA-D observed by FACS analysis compared to the levels observed by immunofluorescence microscopy. FACS analysis may be more objective and reproducible than immunofluorescence microscopy for the detection of EBV induction and also permits viral protein expression to be distinguished in the subpopulation of viable cells.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a human gamma herpesvirus that immortalizes human B lymphocytes and that establishes lifelong infection in the host. In cell culture, EBV may be maintained in vitro in B lymphocytes in perpetuity predominantly as a latent infection with little or no viral replication or with continued production of mature virus at low levels. Chemicals known to induce latent EBV to undergo lytic replication include phorbol esters, including 12-O-tetradecanoyl phorbol-13-acetate (TPA) (50), a direct activator of protein kinase C (18); n-butyrate (21, 28); halogenated pyrimidines such as 5-iododeoxyuridine (14, 16); and nitrosamines (8). The effects of phorbol esters are mediated by protein kinase C activation of the c-jun–c-fos interaction with AP-1 binding sites upstream of promoters of the BZLF1 and BRLF1 immediate-early virus genes (13, 24, 25). Depending on the protein studied, TPA and n-butyrate demonstrate inducer-dependent, cell line-dependent, and protein-specific differences and act in an additive or synergistic manner (1, 7, 31, 40). TPA and n-butyrate induce EBV by different mechanisms, with a peak effect between 1 and 4 days (7, 31, 40). Latent EBV may also be induced by anti-immunoglobulin (42, 44) as well as by superinfection with virus from the P3HR-1 EBV cell line and cell clones of P3HR-1 containing het (heterogeneous)-defective EBV genomes (10).

Several distinct EBV-associated antigen systems and their corresponding antibodies have been characterized and are classified by the phase of the viral replicative cycle during which they are expressed (20). The immediate-early genes (BZLF1, BRLF1, and BI′LF4) are followed sequentially by expression of proteins of the early antigen (EA) complex, viral DNA replication, production of late antigens (e.g., viral capsid antigen), and subsequent cell death with the release of mature virions. The EA complex consists of several viral proteins expressed within the cell and is divided into two components, diffuse (EA-D) and restricted (EA-R), on the basis of cellular localization (after fixation) and susceptibility to denaturation: EA-D is found in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm and is stable in acetone, methanol, and ethanol, and EA-R is found only in the cytoplasm and is stable in acetone but is denatured by methanol or ethanol (19). The EA-D antigen is composed of two moderately abundant nuclear proteins: a 47- to 52-kDa protein transcribed from the BMRF1 open reading frame that is an accessory subunit of the EBV DNA polymerase catalytic subunit that is transcribed from BALF5 (22, 45) and a 44- to 50-kDa protein transcribed from the BSLF2 and BMLF1 open reading frames that is a transactivator of other early EBV genes (9, 47).

The Raji cell line, an EBV genome-positive Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line, harbors approximately 50 to 60 EBV genome equivalents per cell (30, 36). This nonproducer cell line is particularly informative in the study of activation of latent EBV because of an intrinsic block, after expression of EAs, that completely inhibits progression to viral DNA synthesis and late EBV gene expression (32, 43). This block is due to two deletions in the endogenous EBV genome from Raji cells (17, 35, 38) compared to the EBV genome from B95-8 cells (3). A 3.5-kb deletion of BamHI-E results in the complete elimination of BERF4 (EBNA3C) and BZLF2 from EBV in B95-8 cells. A 2.9-kb deletion in BamHI-A removes the complete BALF1 and BARF1 and the N terminus of BALF2, the major EBV DNA binding protein, from EBV in B95-8 cells (48). The BALF2 deletion is responsible for the inability of EBV in Raji cells to complete replication following the induction of latent virus (11). Following chemical induction Raji cells show signs of differentiation into plasma cells but without the morphological changes of EBV lytic replication (1, 2). The late EBV genes are expressed in Raji cells only after lytic induction with P3HR-1 virus containing defective virions of EBV (29) via a mechanism of induction different from the mechanism of chemical induction (24). In contrast to the EBV harbored by the Raji cell line, the EBV harbored by the X50-7 cell line (46) is tightly latent but can be chemically induced to complete virus replication resulting in cell death. The X50-7 cell line was derived by immortalization of human umbilical cord lymphocytes with EBV strain B95-8 (6). The sequence of the subsequent virus from B95-8 cells but not that of virus from X50-7 cells has been shown to have a 12-kb deletion (33) relative to the sequences of other EBV strains. This eliminates one of the origins of lytic replication (oriLyt) (15). The EBV in both Raji and X50-7 cells are subtype A (49).

Experimental detection of the expression of EBV antigens has traditionally been done by immunofluorescence microscopy (20), a time-consuming and labor-intensive method that requires much experience for accurate interpretation of results. The application of fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis or flow cytometry offers semiautomation with the feasibility of counting many more cells than would be practical by conventional immunofluorescence microscopy. In addition, immunofluorescence microscopy necessitates pooling of the results for viable and nonviable cells, whereas FACS analysis permits analysis of viable cells only. In comparison with immunofluorescence microscopy, application of FACS methods in the study of EBV gene expression may contribute to a more precise quantitation of antigen expression, less subjective individual interpretation, greater reproducibility, and faster determination of results, with the additional advantage that EBV gene expression can be studied selectively in viable cells.

The studies described here evaluated the application of FACS analysis to distinguishing viable from nonviable cells and compared FACS analysis to conventional immunofluorescence microscopy for the study of the induction of latent EBV and antigen production in Raji and X50-7 cells with two different chemical induction agents, TPA and n-butyrate, alone and in combination. The effects of TPA and n-butyrate on the induction of EA-D were compared by EBV strain, chemical induction regimen, and the growth rate of the cells at relatively slow or fast rates prior to chemical induction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and virus induction.

The Raji lymphoid cell line (ATCC CCL 86), an EBV-positive cell line derived from a Burkitt’s lymphoma (12, 37), and the X50-7 cell line (46), a human umbilical lymphocyte line immortalized with the EBV from B95-8 cells (6), were used. The cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum with 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 U of streptomycin per ml, 2.5 μg of amphotericin B per ml, and 2 mM glutamine at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Raji and B95-8 cells show a lag in growth for approximately 24 h after splitting, followed by exponential growth peaking at 5 days and, finally, a subsequent decrease in the cell count (4, 5). For these studies two subpopulations of Raji and X50-7 cells were maintained in 25-cm2 flasks for at least 2 weeks prior to chemical induction: cultures designated fast growing were split 1:1 with fresh medium twice per week (1st and 4th days), and cultures designated slow growing were split 1:1 with fresh medium once per week.

Chemical induction of EBV was initiated 24 h after splitting the cultures by the addition to the growth medium of TPA (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) at 20 ng/ml (10 μg/ml in ethanol), n-butyrate (Sigma) at 4 mM (11 mg/ml in water), or both compounds at the same concentrations used individually. The cells were harvested for analysis at 2 and 4 days after induction.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

The cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), resuspended to a concentration of 10,000 cells per 10 ml, prepared as cell smears on eight-well microscope slides (Carlson Scientific, Peotone, Ill.), and allowed to air dry for 1 h. Cell smears were fixed with prechilled acetone for 4 min and were allowed to air dry. Cells smears were stained for EA-D with 20 μl of mouse immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibody (DuPont, Billerica, Mass.) against EA-D (34) for 60 min at 37°C in a humidified chamber, rinsed twice in PBS for 10 min, stained with goat anti-mouse IgG (heavy and light chain specific)–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antibody (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) diluted 1:20 in PBS with 0.002% Evans blue counterstain, rinsed twice in PBS for 10 min, dipped in distilled water, and allowed to air dry. A coverslip was applied with glycerol-PBS (9:1; pH 8.5) as the mounting medium. A total of approximately 1,000 cells were counted by visual microscopy with a Zeiss epifluorescence microscope and were recorded as fluorescing or nonfluorescing.

Flow cytometry.

Cells were fixed and stained by using an adaptation of methanol fixation that allows for flow cytometry analysis (26). Cells were washed three times with PBS, fixed by resuspension in 1 ml of 100% methanol at 4°C for 15 min, washed once with PBS, and washed twice with a FACS buffer (PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 0.01% NaN3). Induction of EBV EA-D was detected by using at 100 μg/ml (diluted in PBS) the same mouse IgG1 monoclonal antibody against EA-D (DuPont) described above. The cells were stained with 50 μl of anti-EA-D antibody for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were rinsed three times with FACS buffer and were counterstained for 30 min at 37°C with goat anti-mouse IgG (heavy and light chain)–FITC conjugated antibody (Boehringer Mannheim) diluted 1:20 with 0.001% Evans blue in PBS. The cells were rinsed three times with FACS buffer and were resuspended in 0.5 ml of FACS buffer for FACS analysis.

Flow cytometry was performed by using a FACStar Plus (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, Calif.) flow cytometer with an argon-ion laser producing 200 mW of 488-nm light for excitation. The principles of flow cytometry have been described previously (27). The percentage of viable cells in each cell sample was determined in a separate aliquot prior to fixation and permeabilization by using propidium iodide staining to identify dead cells. The fluorescence from the propidium iodide was measured through a 630/22-nm bandpass filter. The fluorescence from the FITC (for EA-D) was measured through a 530/30-nm bandpass filter (Oriel Optical, Stamford, Conn.). The fixed cells were gated on the basis of forward-angle light-scatter pulse height, forward-angle light scatter pulse width, and right-angle light scatter pulse height to exclude small debris, cell fragments, and cell aggregates. Single-parameter data were collected for 20,000 intact viable cells by determination of forward- and right-angle light scatter for each experimental group (a total of 16 groups), and the data were displayed as a cell frequency histogram over 512 channels.

The percentage of cells that expressed EA-D as determined by FACS analysis was determined separately for each experimental group at the log relative fluorescence intensity at which 1% of control cells stained only with the secondary antibody (the FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG) showed fluorescence. Additional control cells were stained with mouse isotype-specific IgG1 monoclonal antibody followed by goat anti-mouse IgG (heavy and light chain)–FITC conjugate antibody to control for nonspecific immunoglobulin binding.

Statistical analysis.

FACS analysis data on the percentage of viable cells and the percentage of viable cells expressing EA-D at 4 days after chemical induction (with or without TPA and with or without n-butyrate) for cells growing at a slow rate and a fast rate were analyzed by three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in which the Raji or X50-7 cell type was included as a blocking factor and TPA and n-butyrate were included as treatment factors. Outcome data (percentage of viable cells and percentage of viable cells expressing EA-D) were transformed by using arcsin ( ), a variance-stabilizing transformation appropriate for percentages (41). ANOVA models included Raji or X50-7 cell type, TPA, and n-butyrate as main effects and an interaction for TPA and n-butyrate. Values predicted on the basis of the model and 95% confidence intervals were back-transformed (back-transformation = 100 · sin2 t) for purposes of graphical display (t is a sample statistic from the transformed data set).

), a variance-stabilizing transformation appropriate for percentages (41). ANOVA models included Raji or X50-7 cell type, TPA, and n-butyrate as main effects and an interaction for TPA and n-butyrate. Values predicted on the basis of the model and 95% confidence intervals were back-transformed (back-transformation = 100 · sin2 t) for purposes of graphical display (t is a sample statistic from the transformed data set).

RESULTS

None of the control cells demonstrated nonspecific binding of immunoglobulin by direct immunofluorescence microscopy or FACS analysis.

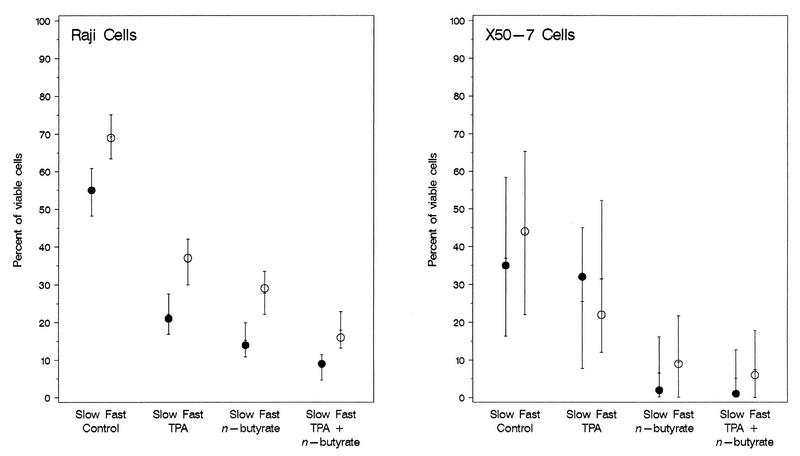

Differences in cell viability and in the induction of latent EBV as determined by the levels of expression of EA-D as a result of the effects of TPA, n-butyrate, and both chemicals were found between EBV-infected Raji and X50-7 cells. The mean percentage of viable cells was higher for untreated Raji cells (55 to 69%) than for untreated X50-7 cells (35 to 44%), although the 95% confidence intervals overlapped. Untreated Raji cells had higher percentages of viable cells than any group of treated Raji cells. Raji cells treated with TPA alone exhibited intermediate viability, with slightly lower viability in cells treated with n-butyrate alone, which was minimally lower with both chemicals (Fig. 1). Regardless of a slow or a fast growth rate, TPA significantly reduced viability (P = 0.001), n-butyrate significantly reduced viability (P = 0.0004), but the effect of the two chemicals combined was not as great as that predicted from the effects of the chemicals used individually (TPA × n-butyrate interaction; P = 0.008). There was also a significant independent effect of growth rate, with uniformly lower rates of cell viability for slowly growing Raji cells than for fast-growing Raji cells (P = 0.003), regardless of the type of chemical induction. For X50-7 cells, the maximal decrease in cell viability occurred with n-butyrate with or without TPA.

FIG. 1.

Observed values (circles) and estimated means and 95% confidence intervals (bars) for viability of Raji cells and X50-7 cells growing at a slow rate and a fast rate following chemical induction of latent EBV by TPA (20 ng/ml), n-butyrate (4 mM), or both compounds measured by FACS analysis at 4 days. Complete viral replication is constitutively inhibited in Raji cells (17, 35, 38), resulting in the accumulation of EA; the increased rates of death for treated cells compared to that for untreated cells is the result of the direct toxicity of TPA and n-butyrate (1, 2). Induction of EBV in X50-7 cells continues to complete viral replication with resultant cell death; increased rates of death for treated cells compared to that for untreated cells is the result of the combination of chemical toxicity plus lytic viral replication. The error bars for X50-7 cells are significantly larger because of the reversal of the results (for slow or fast growth) for TPA treatment alone compared to the results for all other groups (untreated and treated Raji and X50-7 cells).

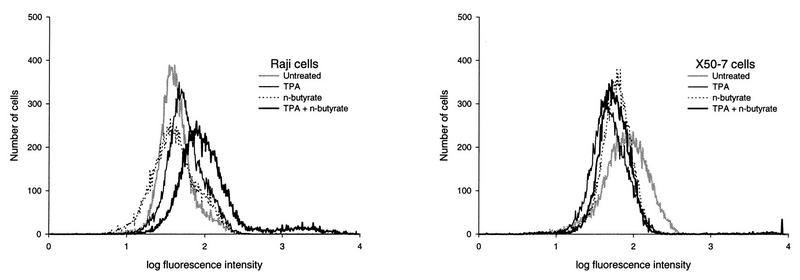

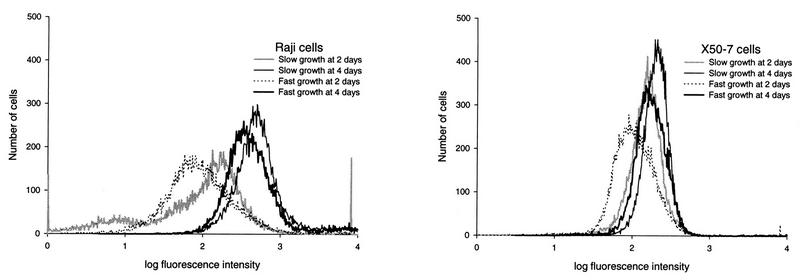

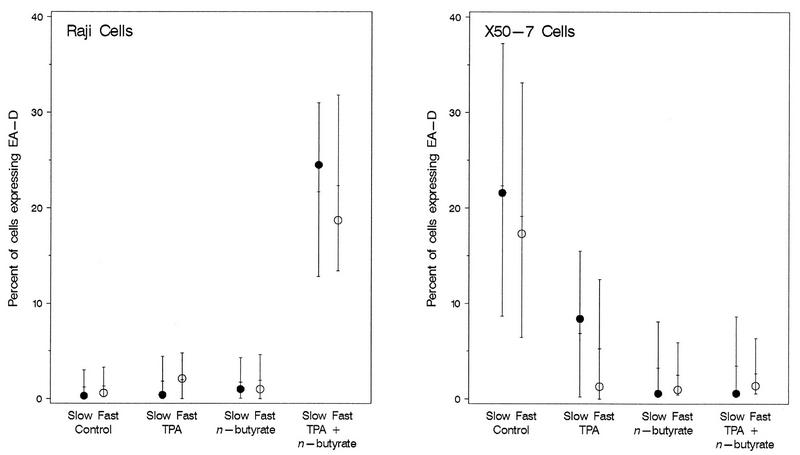

For Raji cells (Fig. 2) the highest level of chemical induction of EA-D as determined by FACS analysis was at 4 days for induction with TPA plus n-butyrate (18.7 to 24.5%), and the level was much higher than the level obtained 2 days after induction with either chemical alone (0.4 to 2.1%) or with both chemicals (2.2 to 3.4%). Substantially higher levels of EA-D were found in Raji cells at 4 days than at 2 days for all chemical treatments (0.4 to 24.5% compared to 0.0 to 3.4%, respectively). EA-D expression did not appear to differ by slow or fast growth rate at 2 days (2.2 and 3.4%, respectively) or at 4 days (24.5 and 18.7%, respectively) (Fig. 3). Statistical analysis showed that at 4 days, the levels of EA-D in Raji cells treated with TPA or n-butyrate alone were statistically similar to those in untreated cells (P > 0.46), while the level of expression in cells treated with TPA plus n-butyrate was significantly increased (P < 0.007) compared to those in all other groups (Fig. 4). There was not a clearly appreciable difference in EA-D levels in Raji cells that grew slowly and those that grew fast (P = 0.8).

FIG. 2.

Effect of chemical induction of EBV in Raji cells and X50-7 cells (both growing at a fast rate) with TPA (20 ng/ml), n-butyrate (4 mM), and both chemicals at 4 days determined by FACS analysis with an EBV EA-D antibody. Each plot represents 20,000 viable lymphocytes (nonviable cells were excluded from FACS analysis). The percentage of cells that expressed EA-D by FACS analysis was determined separately for each experimental group at the log relative fluorescence intensity at which 1% of control cells stained only with the secondary antibody (the FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG) showed fluorescence. For Raji cells, slightly increased levels of expression of EA-D are detectable with each chemical (0.6 to 2.2%) compared to level of expression for untreated cells (0.3 to 0.6%), but the level of EA-D expression is increased 8 to 48 times when both chemicals are used compared to the level of EA-D expression after induction with either chemical alone. For X50-7 cells, the highest levels of EA-D expression detectable by FACS analysis (viable cells only) are those of untreated cells (11.3 to 22.2%) compared to the level of expression after treatment with either chemical alone (0.6 to 8.0%) or both chemicals (0.2 to 1.4%).

FIG. 3.

Effect of rate of cell growth rate (slow or fast) on chemical induction of EBV in Raji cells and X50-7 cells with the combination of TPA (20 ng/ml) and n-butyrate (4 mM) at 2 and 4 days determined by FACS analysis with an EBV EA-D antibody. Each plot represents 20,000 viable lymphocytes (nonviable cells were excluded from FACS analysis). The percentage of cells that expressed EA-D by FACS analysis was determined separately for each experimental group at the log relative fluorescence intensity at which 1% of control cells stained only with the secondary antibody (the FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG) showed fluorescence. For Raji cells, the levels of EA-D are similar for both slowly growing and fast-growing cells at 2 days (2.1 and 3.4%, respectively) and at 4 days (28.5 and 18.3%, respectively; P = 0.8). For X50-7 cells, the levels of EA-D are also similar at 2 days for both slowly growing and fast-growing cells (0.2 and 0.6%, respectively) and are slightly higher at 4 days in cells growing at a fast rate than in cells growing at a slow rate (1.4 and 0.5%, respectively).

FIG. 4.

Observed values (circles) and estimated means and 95% confidence intervals (bars) for EA-D expression in viable cells only following induction of latent EBV in Raji cells and X50-7 cells growing at a slow rate and a fast rate with TPA (20 ng/ml), n-butyrate (4 mM), or both compounds measured by FACS analysis at 4 days. The combination of TPA plus n-butyrate resulted in a synergistic induction of latent EBV as evidenced by the marked decrease in cell viability (Fig. 1) and the increased level of EA-D production in viable cells.

For X50-7 cells (Fig. 2), the highest levels of EA-D by FACS analysis (viable cells only) were found in untreated cells (11.3 to 23.3%) and fell dramatically with treatment with TPA (1.3 to 8.4%), n-butyrate (0.6 to 1.0%), or both chemicals (0.2 to 1.4%).

Comparison of immunofluorescence microscopy (viable and nonviable cells) and FACS analysis (viable cells only) methods for EA-D detection and quantitation revealed generally higher levels by FACS analysis, with greater disparity between the methods for cell populations demonstrating higher EA-D levels (Table 1). The fluorescence intensity by FACS analysis of Raji cells showed a bimodal distribution that was most apparent for the cell populations with the highest EA-D levels (Fig. 2). The only substantial discordance between the two methods was in the results for EA-D levels in untreated X50-7 cells, with no discernible EA-D expression by visual immunofluorescence microscopy compared to 11.3 to 23.3% EA-D expression by FACS analysis. The fluorescence intensity of the untreated X50-7 cells determined by FACS analysis showed a platykurtic distribution compared to that of untreated Raji cells (Fig. 2).

TABLE 1.

Expression of EA-D determined by immunofluorescence of viable and nonviable cells and by FACS analysis of only viable cells in Raji and X50-7 cells after chemical induction of EBV with TPA, n-butyrate, and both chemicals at 2 and 4 daysa

| Cell, growth rate, and day | % Expression

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated

|

TPA

|

n-Butyrate

|

TPA + n-butyrate

|

|||||

| IF (%) | FACS (%) | IF | FACS | IF | FACS | IF | FACS | |

| Raji cells, slow growth | ||||||||

| Day 2 | 0 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 | 2.2 |

| Day 4 | 0 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0 | 1.0 | 11.5 | 24.5 |

| X50-7 cells, slow growth | ||||||||

| Day 2 | 0 | 11.3 | 0 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.2 |

| Day 4 | 0 | 21.6 | 0 | 8.4 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Raji cells, fast growth | ||||||||

| Day 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| Day 4 | 0 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 0 | 1.0 | 6.9 | 18.7 |

| X50-7 cells, fast growth | ||||||||

| Day 2 | 0 | 23.3 | 0 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 0.6 |

| Day 4 | 0 | 17.3 | 0 | 1.3 | 0 | 1.0 | 2.6 | 1.4 |

TPA was used at 20 μg/ml, and n-butyrate was used at 4 mM. Immunofluorescence (IF) assays included both viable and nonviable cells. FACS analyses included only viable cells.

DISCUSSION

The effects of chemical induction for the reduction of cell viability were much greater for X50-7 cells than for Raji cells (Fig. 1). Chemical induction of the strain of EBV in Raji cells results in the production of EAs but without the progression to viral replication and consequent cell death (32, 43). The substantially higher levels of EA-D present in Raji cells at 4 days compared to the levels at 2 days and compared to the levels in X50-7 cells at 4 days was the result of additional induction of latent EBV resulting in the accumulation of intact cells producing EA-D but without progression to viral replication and cell death (32, 43). It is not clear whether EA induction in Raji cells is lethal or hastens cell death (1, 2, 39). The decreased viability of Raji cells following chemical induction is more likely due to direct chemical toxicity rather than cell death resulting from virus replication. Unlike Raji cells, chemical induction of EBV replication in cell lines such as X50-7 results in increased cell death from lytic viral replication, and therefore, the efficiency of chemical induction of EBV replication in X50-7 cells is indicated by decreased cell viability (Fig. 1) rather than increased levels of EA-D expression in intact cells (Fig. 4). The viability of X50-7 cells after chemical induction, as determined by FACS analysis, compared to the viability of P3HR-1 cells (another EBV-producing cell line), as determined by trypan blue exclusion (40), showed the same trends but markedly lower levels by FACS analysis. This may represent some difference in these two EBV-producing cell lines but is more likely the result of methodological differences.

In X50-7 cells EA-D expression is characteristically followed by lytic viral replication and cell death; examination of only the viable cells demonstrates an apparent decrease in the percentage of EA-D expression in this population (Table 1) since those cells initially expressing even low levels of EA-D progress to lysis after induction. The differences between immunofluorescence microscopy and FACS analysis of cells expressing EA-D after chemical induction results from this biologic difference of Raji and X50-7 cells and the inclusion of viable and nonviable cells for immunofluorescence microscopy analysis but the inclusion of only viable cells by FACS analysis.

Treatment with the combination of TPA and n-butyrate resulted in greater decreases in cell viability in both cell lines (Fig. 1) and a significantly higher percentage of Raji cells expressing EA-D (Fig. 4). The synergistic action of n-butyrate and TPA for EA-D expression demonstrated by these results is consistent with the observations of other investigators (31).

Raji cells growing at a slow or a fast rate demonstrated similar patterns of viability, but with significant differences in the magnitude of cell death, and similar levels of EA-D expression. The X50-7 cells growing at a slow or a fast rate demonstrated similar results with regard to cell viability and EA-D expression.

The results of conventional immunofluorescence microscopy and FACS analysis of EA-D expression in Raji cells are internally consistent and are in close agreement. No constitutive EA-D expression was observed by immunofluorescence microscopy for untreated Raji cells, although low levels (x̄ = 0.45%) were detected by FACS analysis. The greatest discrepancy between these methods observed with Raji cells was for the treatment group with the highest level of EA-D expression. This was observed at 4 days for cells treated with both chemicals, with the level of EA-D expression being 6.9 to 11.5% (x̄ = 9.2%) by visual immunofluorescence microscopy compared to 18.7 to 24.5% (x̄ = 21.6%) by FACS analysis (Table 1). The difference between these two techniques is due to the greater sensitivity of FACS analysis for the detection of EA-D at lower levels of expression, most likely resulting from the difficulty of visually discerning, despite the use of very experienced observers, weakly positive cells by immunofluorescence microscopy. This is especially problematic in the visual interpretation of cell smears with significant background fluorescence.

The greatest discrepancy between FACS analysis and visual immunofluorescence microscopy was EA-D expression by untreated X50-7 cells (x̄ values, 18.4 and 0%, respectively). Comparison of the fluorescence curves obtained by FACS analysis demonstrates that untreated X50-7 cells have a platykurtic distribution compared to that for untreated Raji cells (Fig. 2) and suggests that in X50-7 cells and perhaps other EBV-producing cell lines there may be ultralow levels of EA-D present that are detectable by FACS analysis but that are not discernible by conventional visual immunofluorescence microscopy. The low- or intermediate-level transcriptional activity that has been demonstrated for almost the entire EBV genome during latency (23) supports this possibility and suggests that FACS analysis may be more sensitive than conventional methods for the detection of ultralow levels of EBV protein production. This may not be detectable by immunofluorescence microscopy due to the inability to visually discern slightly positive cells in cell smears with significant background fluorescence. The levels of EA-D in X50-7 cells following chemical induction are equivalent by visual microscopy and FACS analysis. This scenario probably represents induction of EBV in the population of the cells expressing ultralow levels of EA-D detected initially only by FACS analysis, with the ultimate culmination in the death of these induced cells and their subsequent exclusion from FACS analysis, which included only viable cells. In support of this interpretation is the difference between the levels of EA-D expression between untreated Raji cells and X50-7 cells at 4 days of approximately 19.0% and the difference in cell viability between untreated Raji cells and X50-7 cells at 4 days of 22.5%. The X50-7 cells with ultralow levels of EA-D, which are indiscernible by conventional immunofluorescence methods but which are detectable by FACS analysis, may indicate a primed viral state with greater susceptibility for virus induction.

Both visual immunofluorescence microscopy (of all cells) and FACS analysis (of viable cells only) demonstrated significant differences in EA-D expression between Raji cells and X50-7 cells. FACS analysis also detected in untreated X50-7 cells EA-D that was not detected by conventional immunofluorescence microscopy. It is likely that study of additional EBV-infected cell lines by FACS analysis may demonstrate even among producer cell lines differences that are less apparent by conventional methods.

The application of FACS analysis in the study of viral protein expression has demonstrated several advantages. FACS analysis facilitates the evaluation of much larger cell sample sizes (20,000 to 100,000 cells) than is routinely feasible by immunofluorescence microscopy. FACS analysis is also more objective and does not require experience and expertise in interpretating the visual appearance of the cells. This could minimize intra- and interlaboratory variability and improve experimental reproducibility. FACS analysis may be more sensitive than visual immunofluorescence microscopy for the detection of ultralow levels of protein and may facilitate correct identification of negative cells when moderate or high levels of protein are present in a significant portion of cells.

The increased sensitivity and increased reproducibility of FACS analysis facilitate the study of viral biology by permitting the selection of only viable cells and also the quantitative determination of viral protein production at different stages of latency and replication. The application of FACS analysis to these biologic questions requires an understanding of the differences in the biology between EBV strains, differences resulting from the method of induction, and possible differences due to growth conditions of the cells prior to induction. The platykurtic distribution of EA-D in untreated X50-7 cells compared to that in Raji cells and the constitutive block in Raji cells that prevents viral DNA synthesis and the production of late EBV gene products indicate the better suitability of Raji cells for studies of EA-D induction by FACS analysis. In these experiments the use of FACS analysis to demonstrate induction of latent EBV in Raji cells by detection of EA-D expression in Raji cells was more sensitive than the use of immunofluorescence microscopy. This suggests that FACS analysis of Raji cells may also be the method of choice for the study of compounds with an unknown or a potentially weak potential to chemically induce latent EBV.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants 0389 and 0200 from the Smokeless Tobacco Research Council and a support grant (5P30 CA54174) to the San Antonio Cancer Center from the National Cancer Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anisimová E, Prachová K, Roubal J, Vonka V. Effects of n-butyrate and phorbol ester (TPA) on induction of Epstein-Barr virus antigens and cell differentiation. Arch Virol. 1984;81:223–237. doi: 10.1007/BF01309995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anisimová E, Saemundsen A K, Roubal J, Vonka V, Klein G. Effects of n-butyrate on Epstein-Barr virus-carrying lymphoma lines. J Gen Virol. 1982;58:163–171. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-58-1-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baer R, Bankier A T, Biggin M D, Deininger P L, Farrell P J, Gibson T J, Hatfull G, Hudson G S, Satchwell S C, Séguin C, Tuffnell P S, Barrell B G. DNA sequence and expression of the B95-8 Epstein-Barr virus genome. Nature. 1984;310:207–211. doi: 10.1038/310207a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benz W C, Siegel P J, Baer J. Effects of adenine arabinoside on lymphocytes infected with Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol. 1978;27:475–482. doi: 10.1128/jvi.27.3.475-482.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bister K, Yamamoto N, zur Hausen H. Differential inducibility of Epstein-Barr virus in cloned, non-producer Raji cells. Int J Cancer. 1979;23:818–825. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910230613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blacklow N R, Watson B K, Miller G, Jacobson B M. Mononucleosis with heterophil antibodies and EB virus infection. Acquisition by an elderly patient in hospital. Am J Med. 1971;51:549–552. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(71)90260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boos H, Berger R, Kuklik-Roos C, Iftner T, Mueller-Lantzsch N. Enhancement of Epstein-Barr virus membrane protein (LMP) expression by serum, TPA, or n-butyrate in latently infected Raji cells. Virology. 1987;159:161–165. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouvier G, Poirier S, Shao Y M, Malaveille C, Ohshima H, Polack A, Bornkamm G W, Zeng Y, de-Thé G, Bartsch H. Epstein-Barr virus activators, mutagens and volatile nitrosamines in preserved food samples from high-risk areas for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. IARC Sci Publ. 1991;105:204–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook I D, Shanahan F, Farrell P J. Epstein-Barr virus SM protein. Virology. 1994;205:217–227. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Countryman J, Jenson H, Seibl R, Wolf H, Miller G. Polymorphic proteins encoded within BZLF1 of defective and standard Epstein-Barr viruses disrupt latency. J Virol. 1987;61:3672–3679. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3672-3679.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Decaussin G, Leclerc V, Ooka T. The lytic cycle of Epstein-Barr virus in the nonproducer Raji line can be rescued by the expression of a 135-kilodalton protein encoded by the BALF2 open reading frame. J Virol. 1995;69:7309–7314. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7309-7314.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epstein M A, Achong B G, Barr Y M, Zajac B, Henle G, Henle W. Morphological and virological investigations on cultured Burkitt tumor lymphoblasts (strain Raji) J Natl Cancer Inst. 1966;37:547–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flemington E, Speck S H. Identification of phorbol ester response elements in the promoter of Epstein-Barr virus putative lytic switch gene BZLF1. J Virol. 1990;64:1217–1226. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.3.1217-1226.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerber P. Activation of Epstein-Barr virus by 5-bromodeoxyuridine in “virus-free” human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:83–85. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammerschmidt W, Sugden B. Identification and characterization of oriLyt, a lytic origin of DNA replication of Epstein-Barr virus. Cell. 1988;55:427–433. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hampar B, Derge J G, Martos L M, Walker J L. Persistence of a repressed Epstein-Barr virus genome in Burkitt lymphoma cells made resistant to 5-bromodeoxyuridine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:3185–3189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.12.3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatfull G, Bankier A T, Barrell B G, Farrell P J. Sequence analysis of Raji Epstein-Barr virus DNA. Virology. 1988;164:334–340. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90546-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashi K. Effect of protein kinase C inhibitors with different action mechanisms on Epstein-Barr virus replication. Intervirology. 1992;33:217–224. doi: 10.1159/000150254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henle W, Henle G, Zajac B A, Pearson G, Waubke R, Scriba M. Differential reactivity of human serums with early antigens induced by Epstein-Barr virus. Science. 1970;169:188–190. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3941.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenson H B, Ench Y, Sumaya C V. Epstein-Barr virus. In: Rose N R, de Macario E C, Folds H, Lane H C, Nakamura R M, editors. Manual of clinical laboratory immunology. 5th ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. pp. 634–643. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kallin B, Luka J, Klein G. Immunochemical characterization of Epstein-Barr virus-associated early and late antigens in n-butyrate-treated P3HR-1 cells. J Virol. 1979;32:710–716. doi: 10.1128/jvi.32.3.710-716.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiehl A, Dorsky D I. Bipartite DNA-binding region of the Epstein-Barr virus BMRF1 product essential for DNA polymerase accessory function. J Virol. 1995;69:1669–1677. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1669-1677.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirchner E A, Bornkamm G W, Polack A. Transcriptional activity across the Epstein-Barr virus genome in Raji cells during latency and after induction of an abortive lytic cycle. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2391–2398. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-10-2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laux G, Freese U K, Fischer R, Polack A, Kofler E, Bornkamm G W. TPA-inducible Epstein-Barr virus genes in Raji cells and their regulation. Virology. 1988;162:503–507. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90496-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee W, Mitchell P, Tjian R. Purified transcription factor AP-1 interacts with TPA-inducible enhancer elements. Cell. 1987;49:741–752. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90612-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levitt D, King M. Methanol fixation permits flow cytometric analysis of immunofluorescent stained intracellular antigens. J Immunol Methods. 1987;96:233–237. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(87)90319-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loken M R, Herzenberg L A. Analysis of cell populations with a fluorescence-activated cell sorter. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1975;254:163–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1975.tb29166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luka J, Kallin B, Klein G. Induction of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) cycle in latently infected cells by n-butyrate. Virology. 1979;94:228–231. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(79)90455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller G, Rabson M, Heston L. Epstein-Barr virus with heterogeneous DNA disrupts latency. J Virol. 1984;50:174–182. doi: 10.1128/jvi.50.1.174-182.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nonoyama M, Pagano J S. Separation of Epstein-Barr virus DNA from large chromosomal DNA in non-virus-producing cells. Nature New Biol. 1972;238:169–171. doi: 10.1038/newbio238169a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nutter L M, Grill S P, Li J S, Tan R S, Cheng Y C. Induction of virus enzymes by phorbol esters and n-butyrate in Epstein-Barr virus genome-carrying Raji cells. Cancer Res. 1987;47:4407–4412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ooka T, Lenoir G M, Decaussin G, Bornkamm G W, Daillie J. Epstein-Barr virus-specific DNA polymerase in virus-nonproducer Raji cells. J Virol. 1986;58:671–675. doi: 10.1128/jvi.58.2.671-675.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker B D, Bankier A, Satchwell S, Barrell B, Farrell P J. Sequence and transcription of Raji Epstein-Barr virus DNA spanning the B95-8 deletion region. Virology. 1990;179:339–346. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pearson G R, Vroman B, Chase B, Sculley T, Hummel M, Kieff E. Identification of polypeptide components of the Epstein-Barr virus early antigen complex with monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 1983;47:193–201. doi: 10.1128/jvi.47.1.193-201.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polack A, Delius H, Zimber U, Bornkamm G W. Two deletions in the Epstein-Barr virus genome of the Burkitt lymphoma nonproducer line Raji. Virology. 1984;133:146–157. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pritchett R, Pendersen M, Kieff E. Complexity of EBV homologous DNA in continuous lymphoblastoid cell lines. Virology. 1976;74:227–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pulvertaft R J V. A study of malignant tumours in Nigeria by short-term tissue culture. J Clin Pathol. 1965;18:261–273. doi: 10.1136/jcp.18.3.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raab-Traub N, Dambaugh T, Kieff E. DNA of Epstein-Barr virus. VII. B95-8, the previous prototype, is an unusual deletion derivative. Cell. 1980;22:257–267. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roubal J, Roubalová K. Effect of n-butyrate on superinfection of Raji lymphoblastoid cell line by Epstein-Barr virus. Acta Virol. 1985;29:162–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sairenji T, Spiro R C, Humphreys R E. Differential effect of TPA and n-butyrate on induction of li and EBV antigens in the P3HR-1 lymphoblastoid cell line. Hematol Oncol. 1984;2:381–389. doi: 10.1002/hon.2900020408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sokal R R, Rohlf F J. Introduction to biostatistics. W. H. New York, N.Y: Freeman & Co.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takada K. Cross-linking of cell surface immunoglobulins induces Epstein-Barr virus in Burkitt lymphoma lines. Int J Cancer. 1984;33:27–32. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910330106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan R S, Li J S, Grill S P, Nutter L M, Cheng Y C. Demonstration of Epstein-Barr virus-specific DNA polymerase in chemically induced Raji cells and its antibody in serum from patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1986;46:5024–5028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tovey M G, Lenoir G, Begon-Lours J. Activation of latent Epstein-Barr virus by antibody to human IgM. Nature. 1978;276:270–272. doi: 10.1038/276270a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsurumi T, Daikoku T, Nishiyama Y. Further characterization of the interaction between the Epstein-Barr virus DNA polymerase catalytic subunit and its accessory subunit with regard to the 3′-to-5′ exonucleolytic activity and stability of initiation complex at primer terminus. J Virol. 1994;68:3354–3363. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3354-3363.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson G, Miller G. Recovery of Epstein-Barr virus from nonproducer neonatal human lymphoid cell transformants. Virology. 1979;95:351–358. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(79)90490-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong K M, Levine A J. Characterization of proteins encoded by the Epstein-Barr virus transactivator gene BMLF1. Virology. 1989;168:101–111. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90408-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang C X, Decaussin G, Daillie J, Ooka T. Altered expression of two Epstein-Barr virus early genes localized in BamHI-A in nonproducer Raji cells. J Virol. 1988;62:1862–1869. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.6.1862-1869.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zimber U, Adldinger H K, Lenoir G M, Vuillaume M, Knebel-Doeberitz M V, Laux G, Desgranges C, Wittmann P, Freese U K, Schneider U, Bornkamm G W. Geographical prevalence of two types of Epstein-Barr virus. Virology. 1986;154:56–66. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90429-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.zur Hausen H, O’Neill F J, Freese U K, Hecker E. Persisting oncogenic herpesvirus induced by the tumour promoter TPA. Nature. 1978;272:373–375. doi: 10.1038/272373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]