Abstract

Importance:

Goals-of-care (GOC) discussions and their documentation are an important process measure in palliative care. However, existing natural language processing (NLP) models for identifying GOC documentation require costly training data that do not transfer to other constructs of interest. Newer large language models (LLMs) hold promise for measuring linguistically complex constructs with fewer or no task-specific training.

Objective:

To evaluate the performance of a publicly available LLM with no task-specific training data (zero-shot prompting) for identifying EHR-documented GOC discussions.

Design, Setting, and Participants:

This diagnostic study compared performance in identifying electronic health record (EHR)-documented GOC discussions of two NLP models: Llama 3.3 using zero-shot prompting, and a task-specific BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers)-based model trained on a corpus of 4,642 manually annotated notes. Models were evaluated using text corpora drawn from clinical trials enrolling adult patients with chronic life-limiting illness hospitalized at a US health system over 2018–2023.

Outcomes and Measures:

The outcomes were NLP model performance, evaluated by the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUC), area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC), and maximal F1 score. NLP performance was evaluated for both note-level and patient-level classification over a 30-day period.

Results:

Across three text corpora, GOC documentation represented <1% of EHR text and was found in 7.3–9.9% of notes for 23–37% of patients. In a 617-patient held-out test set, Llama 3.3 (zero-shot) and BERT (task-specific, trained) exhibited comparable performance in identifying GOC documentation. Llama 3.3 identified GOC documentation with AUC 0.979, AUPRC 0.873, and F1 0.83; BERT identified the same with AUC 0.981, AUPRC 0.874, and F1 0.83. In examining the cumulative incidence of GOC documentation over the specified 30-day period, Llama 3.3 identified patients with GOC documentation with AUC 0.977, AUPRC 0.955, and F1 0.89; and BERT identified the same with AUC 0.981, AUPRC 0.952, and F1 0.89.

Conclusions and Relevance:

A zero-shot large language model with no task-specific training performs similarly to a task-specific supervised-learning BERT model trained on thousands of manually labeled EHR notes in identifying documented goals-of-care discussions. These findings demonstrate promise for rigorous use of LLMs in measuring novel clinical trial outcomes.

Introduction

Advances in natural language processing (NLP) hold great promise for allowing clinical researchers to measure previously inaccessible constructs from unstructured electronic health records (EHR). A significant driver of recent progress in NLP has been the shift from machine learning (ML) models trained on large amounts of labeled data to newer machine models pre-trained on vast quantities of unlabeled text by their developers. These models, known as large language models (LLMs), acquire linguistic patterns, representations, and features of language through their pre-training, allowing them to generalize across a wide range of NLP tasks.1 The latest generation of LLMs has gained widespread attention through their deployment as generative artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots accessible to the public.

Earlier ML models underlying NLP often required training on large manually labeled datasets—a process known as supervised learning—to achieve acceptable task-specific performance. However, acquiring and labeling representative training data can be prohibitively expensive, especially for rare constructs. With the advent of newer LLMs that are pre-trained on vast and diverse corpora, there has been growing interest in using zero-shot or few-shot learning approaches to measure linguistic constructs without incurring the costs of labeling training data.2 In these approaches, LLMs are prompted to perform classification tasks with zero or minimal task-specific training data, instead relying on careful prompting in conjunction with the model’s “out-of-the-box” pre-training to apply previously learned patterns to the task at hand (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of supervised, few-shot, and zero-shot machine learning.

| Learning approach | Description a | Examples and analogies |

|---|---|---|

| Supervised learning | Model is trained (“fine-tuned”) on a labeled dataset, mapping input data to the correct output by minimizing error between predicted and actual labels. |

|

| Few-shot learning | Pre-trained model is fine-tuned to, or prompted with, a small number of labeled examples, relying on the model’s pre-training to apply previously learned patterns to a new task. Examples need not cover full range of variability or noise expected in the target task, as the model leverages prior learning to generalize effectively. |

|

| Zero-shot prompting | Model is prompted to make predictions without any task-specific examples, relying entirely on the model’s pre-training to generalize to the new task. |

|

Abbreviations: ML, machine learning; LLM, large language model; GOC, goals of care.

In machine learning, pre-training refers to the initial process of training a model on a large, general dataset to learn patterns, representations and features that are broadly applicable across tasks. Pre-training is often performed by the model’s creators. Whereas, fine-tuning refers to subsequent adjustment of a pre-trained model on a smaller, task-specific dataset, often performed by those adapting the model for a particular use.

Our research group has focused on using NLP to identify EHR-documented goals-of-care discussions for patients with serious illness—an important process measure in palliative care research and a linguistically complex construct often documented in unstructured text.3–5 We have previously reported on using supervised learning to train BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers)-based models6,7 to identify goals-of-care documentation. While these models perform well, they were trained on task-specific data requiring hundreds of abstractor-hours and months-to-years to acquire.5 These high costs limit researchers’ ability to adapt such models toward measuring other constructs. Furthermore, while the fixed costs of implementing NLP infrastructure may be shared across multiple research projects, the costs of acquiring task-specific training data are unique to each linguistic construct and do not transfer well to other constructs, projects, or even institutions,8 making supervised learning a costly approach for many researchers. To explore the potential of modern LLMs for current and future research tasks, we evaluated the performance of a publicly accessible LLM using zero-shot prompting to identify documented goals-of-care discussions for patients with serious illness.

Methods

This diagnostic study evaluated the zero-shot performance of Llama 3.3 (Meta AI, ai.meta.com), a publicly available pre-trained general-purpose LLM, in predicting the presence of documented goals-of-care discussions in EHR notes of hospitalized patients with serious illness. We compared Llama predictions against gold-standard results from manual abstraction, and also compared Llama performance against the benchmark of a previous BERT-based model that was fitted using supervised ML to manually abstracted training data.5 All study procedures were approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division Institutional Review Board (STUDY00011002).

Data sources

There are three datasets used in this trial (Table 2): (1) a pilot set, consisting of 4,642 EHR notes from 150 patients enrolled in a pilot trial of a patient- and clinician-facing communication-priming intervention;5,9 (2) the Trial 1 test set, consisting of 2,974 EHR notes from a sample of 160 of 2,512 patients enrolled in a pragmatic trial of a clinician-facing-only communication priming intervention;10,11 and, (3) the Trial 2 held-out test set, consisting of 11,574 EHR notes belonging to 617 patients enrolled in a comparative-effectiveness trial of two communication priming interventions.11 The detailed inclusion criteria for patients in each dataset have been previously reported;5,9–11 briefly, all patients were hospitalized at any of 2–3 study hospitals in the UW Medicine health system, Seattle, WA; were of advanced age (≥ 80 years); or, were of age 55 years or older with one or more chronic life-limiting illnesses as defined by diagnosis codes. Each set consisted of all notes for the sampled patients collected over similar time frames that were authored by attending and trainee physicians, advance practice providers, and subinterns. The Trial 1 test set was intentionally enriched for patients with Alzheimer disease and related dementias (ADRD; 80/160 [50%]) to support an interim subgroup analysis in the parent trial. Additionally, the Trial 1 test set is slightly larger here than in previous reports due to the inclusion of notes preceding parent trial randomization and notes from one patient whose records were inadvertently sampled from the wrong index admission. The interventions tested in all three trials (variants of the Jumpstart Guide) did not alter existing clinician EHR documentation processes or templates for documentation of goals-of-care discussions.9–11

Table 2.

Datasets used in this study.

| Pilot set | Trial 1 test set | Trial 2 held-out test set | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Description of patients, and enrollment procedure | All 150 patients enrolled in a 2-hospital pilot trial with informed consent over Nov. 2018 to Feb. 20209 | Sample of 160 patients enrolled in a 2,512-person 3-hospital pragmatic trial under a waiver of informed consent, enriched for ADRD (80 of 160 [50%]), over Apr. 2020 to Mar. 202110,11 | All 617 patients enrolled in a 3-hospital comparative-effectiveness trial with informed consent over Jul. 2021 to Nov. 202311 (trial results not yet published) |

| Description of EHR notes | 4,642 notes from index admission to discharge | 2,974 notes from index admission to 30 days postrandomization | 11,574 notes from randomization to 30 days post-randomization |

| Adjudication of ground truth | Manual whole-chart abstraction by human reviewers, with regular quality assurance applied at the passage level | Manual whole-chart abstraction by human reviewers, with regular quality assurance applied at the passage level | BERT NLP-screened human abstraction of passages scoring over 98.5th percentile, a with principal investigator co-review of all positive abstractions by patient |

| Prevalence of GOC discussions | 0.2% of BERT segments; 340 / 4,642 (7.3%) notes; 34 / 150 (23%) patients | 0.4% of BERT segments; 295 / 2,974 (9.9%) notes; 59 / 160 (37%) patients | 304 / 2,136 notes in case-control sample; b 163 / 617 (26%) patients |

| Role of dataset for each NLP model c | |||

|

Llama 3.3 LLM (zero-shot prompt) |

Development | Testing | Held-out testing |

|

BERT (supervised ML) |

Training and validation | Testing | Held-out testing |

Abbreviations: ADRD, Alzheimer disease and related dementias; EHR, electronic health record; BERT, Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers; GOC, goals of care; NLP, natural language processing; LLM, large language model; ML, machine learning.

In the Trial 1 test set, this screening threshold corresponded with 99.3% note-level sensitivity (95%CI 97.6%, 99.9%) and 100% patient-level sensitivity (one-sided 97.5%CI 97.7%, 100%).

Case-control sample of notes in the Trial 2 held-out test: cases, 304 notes with human-confirmed GOC content; controls, up to three randomly sampled GOC-negative notes per patient. Prevalence in sample (14%) is not expected to represent source data.

In supervised machine learning, “training” refers to fitting a model to labeled data; “validation” refers to tuning model hyperparameters during development; and, “testing” refers to evaluating the performance of the final model after all training and development is complete. A “held-out test set” is a special test set that is kept completely separate from all model development, minimizing possibility of indirect leakage or bias. Because zero-shot prompting does not fit a model to any labeled data, the pilot set is referred to as a “development” set for the Llama model.

By definition, the zero-shot Llama 3.3 LLM (hereafter, Llama 3.3) had no task-specific training dataset, and all LLM prompt engineering and hyperparameter selection was conducted using notes drawn from the pilot set. The Llama model was tested on both the Trial 1 test set and the Trial 2 held-out test set. The reference BERT-based model was trained and validated on the pilot set, and subsequently evaluated on the Trial 1 test set as previously reported.5 For this study, the same model was also tested on the Trial 2 held-out test set.

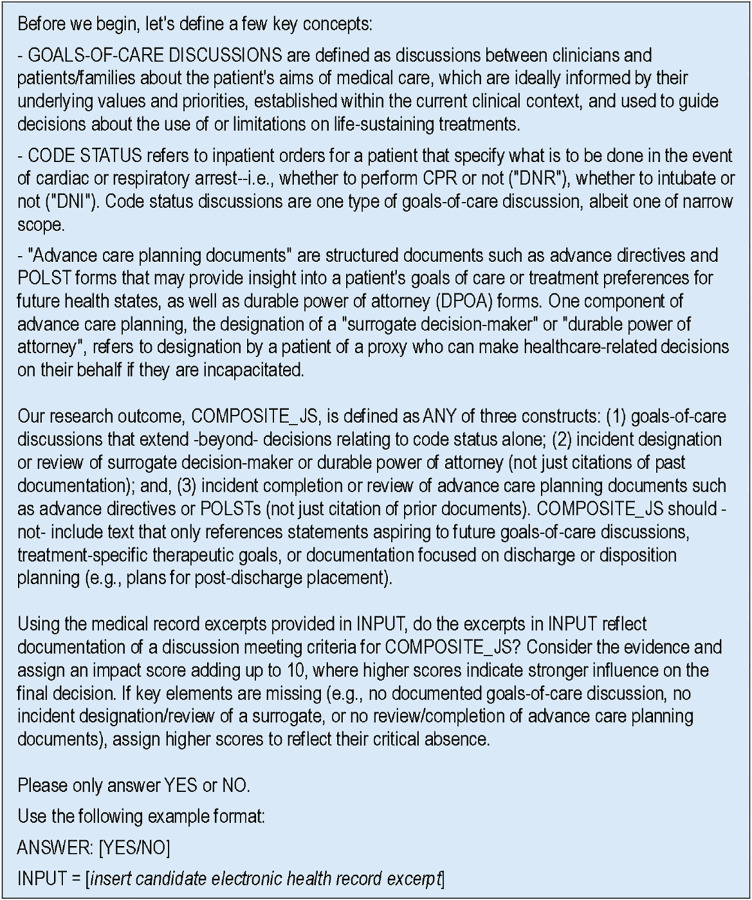

Natural language processing

Llama 3.3 is a 70-billion-parameter generative LLM with a 128,000-token context length, developed and pre-trained by Meta AI on an undisclosed collection of public online data. (Tokens are an NLP term for words and subwords that form the smallest unit of NLP analysis; the context length of a model defines the largest text passage it can analyze at once.) Most EHR notes may be analyzed in their entirety within Llama 3.3’s context length; notes exceeding this context length were partitioned evenly and assigned the highest predicted probability of their constituent partitions. Notes were preprocessed using regular expressions to remove common headers, footers, allergy and medication sections, and a palliative care quality improvement checklist consisting only of discrete data. To predict the probability of documented goals-of-care discussions in each candidate note or partition, we prompted a newly initialized Llama 3.3 model with our operational definition and the candidate text (Figure 1). We then examined the raw scores (logits) underlying the model’s generated response, which were transformed into probabilities that reflect the model’s confidence in predicting an affirmative (“Yes”) vs. negative (“No”) response.

Figure 1.

Prompt for zero-shot Llama 3.3 language model.

The reference BERT-based model for identifying documented goals-of-care discussions5 is an instance of BioClinicalBERT7 that was trained by our team on labeled notes from the pilot set (Table 2). BioClinicalBERT is a publicly-available customization of BERTBASE (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers—base model),6 a 110-million-parameter model with a 512-token context length developed and pre-trained by Google Research (google.com) on the full text of English Wikipedia and BookCorpus (a dataset of 11,000 unpublished books).12 BioClinicalBERT was further pre-trained by Alsentzer et al on 200,000 PubMed abstracts, 270,000 PubMed Central manuscripts, and 2.1 million EHR notes from the MIMIC III database.7,13 Notes were partitioned into BERT passages of ≤ 512 BERT tokens over common whitespace patterns; the BERT-predicted probability for each note was defined by the highest predicted probability of its constituent passages.

Llama 3.3 and other recent Llama models have been released by Meta AI under a licensing agreement and use policy that allows for free non-commercial use by the public. To ensure privacy and prevent model developers from training on protected health information, we ran Llama locally on a secure in-house server. The server was equipped with a 16-core AMD Epyc 9124 processor (Advanced Micro Devices, amd.com), a single Nvidia RTX A6000 graphics processing unit (GPU) (Nvidia Corporation, nvidia.com), and 48 gigabytes of video random-access memory (VRAM). Both BioClinicalBERT and the original BERT family of models have been made open-source and publicly available by their respective developers.14,15

Adjudication of ground truth

Ground-truth for BERT passage- and note-level presence or absence of EHR-documented goals-of-care discussions was determined for all notes in the pilot set and Trial 1 test set using manual human chart abstraction, as previously described.5 During these abstraction efforts, abstractors met regularly as a group to discuss their findings, and instances of disagreement were resolved by consensus. Quality assurance practices, such as co-review of passages by senior research coordinators and investigators, were applied at the passage level.

The Trial 2 held-out test set, which included 617 patients—substantially more than the pilot (150 patients) and Trial 1 (160 patients) test sets—was adjudicated for presence and timing of first human-confirmed documented goals-of-care discussion within 30 days of randomization using BERT NLP-screened human abstraction. In this approach, the BERT model, which was trained on the pilot set and previously tested on the Trial 1 test set, was applied to the Trial 2 held-out test set using a highly-permissive (i.e., sensitive) screening threshold to select passages for human adjudication for goals-of-care content. This approach enabled measurement of a much larger number of patient-level outcomes than would be feasible in a manually-abstracted validation sample. While this use of BERT may lead to overestimation of its own performance in the same dataset, it should not affect evaluation of Llama models; and, setting a permissive screening threshold should mitigate bias in BERT’s performance estimates. For adjudicating the held-out test set, the screening threshold was set to the 98.5th percentile of BERT-predicted passage-level probabilities for goals-of-care content, resulting in 8,952 of 559,596 BERT passages (1.6%) screening positive; 3,718 of 11,574 notes (32%) contained at least one screen-positive passage, and 533 of 617 patients (86%) had at least one screen-positive passage. Evaluation of the selected BERT screening threshold in the Trial 1 test set yielded 99.3% note-level sensitivity (95%CI 97.6%, 99.9%) and 100% patient-level sensitivity (one-sided 97.5%CI 97.7%, 100%).5 Because not all notes in the Trial 2 held-out test set were adjudicated by humans, note-level performance in the Trial 2 held-out test set was evaluated using a 2,136-note case-control sample of all notes containing human-confirmed goals-of-care content (304 notes) and up to 3 randomly selected notes per patient without goals-of-care content (i.e., with BERT score less than 98.5th percentile; 1,832 notes). In addition to the same quality assurance practices applied during abstraction of the pilot and Trial 1 test sets, Trial 2 records coded as positive or possibly-positive by abstractors were further co-reviewed by a single clinician (E.K.) by patient (i.e., reviewing multiple coded passages per patient across multiple notes) to ensure consistency of the outcome measure. Patient-level performance in the Trial 2 held-out test set was evaluated by comparing NLP predictions for all 11,574 notes against patient-level results of NLP-screened human abstraction for all 617 patients.

Statistical analysis

We evaluated the performance of each language model against the reference standard in each testing dataset through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and precision-recall (PR) analysis.16 In all analyses, patient-level probability was defined as the maximal NLP-predicted probability of all constituent notes or passages; and, patient-level ground truth was defined as the union of ground truth for all constituent notes. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata/MP, version 19.0 (StataCorp LLC, stata.com), and areas under ROC and precision-recall curves were calculated using cubic splines.

Results

The composition, inclusion criteria, and adjudication of ground truth for each dataset are described in Table 2. In each dataset, there were between 295 and 340 notes containing goals-of-care discussions corresponding to a variable number of patients, and between 1,832 and 4,302 notes without goals-of-care discussions. In the Trial 1 test set, 59 of 160 patients (37%) had at least one goals-of-care discussion between index admission and 30 days post-randomization. In the Trial 2 held-out test set, 163 of 617 patients (26%) had at least one goals-of-care discussion between index admission and 30 days post-randomization. The note- and patient-level prevalence of goals-of-care discussions is expected to differ between datasets due to differences in note inclusion criteria, enrollment procedures, and interventions tested.

In comparing Llama 3.3 and BERT NLP predictions against manual or NLP-screened manual abstraction in the Trial 1 test set and Trial 2 held-out test set, the zero-shot Llama 3.3 model consistently demonstrated highly comparable performance to the reference BERT model that had been trained on the pilot set. Figure 2 shows ROC and precision-recall curves for note-(panel A) and patient-level (panel B) classifiers across models (Llama vs. BERT) and datasets, and Table 3 shows areas under the ROC and precision-recall curves as well as maximum observed F1 scores for each model and dataset. In the Trial 2 held-out test set, the area under the ROC curve for note-level analysis was 0.979 for Llama, and 0.981 for BERT; and, the area under the precision-recall curve for note-level analysis was 0.873 for Llama, and 0.874 for BERT. The maximum observed note-level F1 score in the held-out test set was 0.83 for both Llama and BERT.

Figure 2.

Performance of zero-shot Llama 3.3 vs. supervised-learning BERT models in detecting documented goals-of-care discussions for hospitalized patients with serious illness.

Table 3.

Performance metrics of zero-shot Llama 3.3 vs. supervised-learning BERT models in identifying documented goals-of-care discussions for hospitalized patients with serious illness.

| Dataset | NLP model (machine learning approach) | AUC | AUPRC | Maximal F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note-level classification | ||||

| Trial 1 test set (n=2,974) | Llama 3.3 (zero-shot ML) | 0.961 | 0.795 | 0.74 |

| BERT (supervised ML) | 0.962 | 0.789 | 0.74 | |

| Trial 2 held-out test set (sample of n=2,136) a | Llama 3.3 (zero-shot ML) | 0.979 | 0.873 | 0.83 |

| BERT (supervised ML) | 0.981 | 0.874 | 0.83 | |

| Patient-level classification over ~30-day period | ||||

| Trial 1 test set (n=160) | Llama 3.3 (zero-shot ML) | 0.912 | 0.885 | 0.80 |

| BERT (supervised ML) | 0.898 | 0.833 | 0.80 | |

| Trial 2 held-out test set (n=617) a | Llama 3.3 (zero-shot ML) | 0.977 | 0.955 | 0.89 |

| BERT (supervised ML) | 0.981 | 0.952 | 0.89 | |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic [ROC] curve; AUPRC, area under the precision-recall curve; BERT, Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers; ML, machine learning; NLP, natural language processing.

The Trial 2 held-out test set contained 11,574 notes, of which 2,136 with known true values were sampled for evaluation of note-level performance. Patient-level performance was evaluated by comparing NLP analysis of all 11,574 notes against the NLP-screened human-abstracted gold standard for all 617 patients.

Notably, we observed higher performance in the Trial 2 held-out test set for both Llama and BERT models than in the Trial 1 test set. The difference in performance between datasets (Figure 2, red vs. blue lines) outweighed differences in performance between models (Figure 2, dark vs. light lines). Although some such differences were expected (as BERT NLP predictions were part of the referent outcome measure in the Trial 2 held-out test set), the fact that these same differences between datasets were observed in zero-shot Llama models suggested that differences in ground truth adjudication between the datasets may have contributed to differential performance.

Discussion

In this report, we demonstrated that with careful prompting, a zero-shot LLM with no task-specific training can achieve comparable performance to a task-specific supervised-learning BERT model trained on thousands of manually labeled EHR notes to identify documented goals-of-care discussions.

Although on first glance it hardly seems noteworthy that a 70-billion-parameter LLM can achieve comparable performance to a 110-million parameter BERT model, the ability to measure linguistically complex outcomes using a zero-shot prompting strategy—which is only possible with LLMs—are of great practical importance to clinical researchers. The training data alone for the referent BERT model was acquired over the course of 287 abstractor-hours over a 4-month period—a ~$20,000 investment to measure a single linguistic construct that must be repeated for any related constructs of interest, and even for different operational definitions of the same construct.5 This cost barrier poses significant challenges for health services researchers interested in measuring multidimensional constructs for which definitions are likely to differ appropriately from study to study.17,18,4 In contrast, iterative development of an LLM prompt is a much faster process that may be quickly replicated or adapted for different linguistic constructs, allowing investigators to pivot to different measures and outcomes while incurring minimal repeated costs. This is particularly important for linguistically complex outcomes such as goals-of-care documentation, which are difficult to measure using widely-accessible rule-based methods19 and were previously only accessible to qualitative review.20 The ability to capture linguistically complex measures at scale also has implications for mixed-methods researchers, in that novel measures that were previously unquantifiable may now be quantifiable.21–24

Despite their advantages, zero-shot methods have their disadvantages as well. First, zero-shot prompting relies heavily on the model’s pre-training from its developers. This dependency may introduce some degree of instability and irreproducibility to a given model, as changes between model versions introduced by the developer may alter the performance of a model for a given task in response to a particular prompt. Second, LLMs are computationally resource-intensive, and at present often require upgraded hardware to deploy at scale, especially for use cases that require real-time results. The inefficiency of these models may limit their use cases, at least until LLM-capable hardware or institutionally-approved secure cloud environments for their use are widely available. Active efforts in the machine learning community to shrink and streamline LLMs may also help improve their efficiency.25 Third, LLMs suffer from the “black box” phenomenon, in which the reasons for a model’s predictions are opaque to their operators. However, this limitation—which is shared by nearly all ML models—is potentially easier to overcome with LLMs than with previous-generation models such as BERT, as prompting strategies that ask LLMs to follow specific patterns of logical reasoning have been shown to both be feasible to implement and also a means to generate more robust model output.26 Related to this problem, LLMs also contain embedded biases that are propagated from their training data.27 However, prompting strategies that guide LLMs through cognitive processes serve as an intriguing potential solution to reduce biases in LLM responses, a strategy that is not available to previous-generational models.28

Our finding of substantial differences in performance between the Trial 1 and Trial 2 datasets, with nearly identical performance of two different models that are related only in their respective developers and operational definition of documented goals-of-care content, was somewhat surprising. We had hypothesized that Llama 3.3 might exhibit better generalizability than BERT to a held-out test set; however, we were unable to evaluate this hypothesis as BERT performance also differed substantially between the two datasets. While differences in AUPRC are expected with datasets with different prevalence, AUC should be a prevalence-independent measure. Furthermore, although it is tempting to blame the presence of BERT NLP screening in the adjudication of ground truth for the Trial 2 dataset, (1) the screening threshold we used was so permissive (i.e., its anticipated sensitivity so high) as to make this explanation for differential performance unlikely; and, most importantly, (2) there is no conceivable reason why bias introduced by the BERT NLP screening instrument would spuriously affect the results of the zero-shot Llama model, which differs markedly in architecture and provenance and shares no task-specific training data whatsoever with the BERT screening model. The fact that the Trial 2 dataset was completely sequestered from developers until all model development was finalized lends further robustness to our findings. Ultimately, we suspect that additional quality assurance measures that were applied to the Trial 2 dataset are likely to lend additional validity to this dataset, and that it is possible that both our Llama and BERT models are nearing a performance ceiling for what can be confidently extracted in dichotomous form from a latent construct that is, in truth, a multidimensional continuous outcome.17,18,4

Our study has multiple important limitations. First, we evaluated a single operational definition of a single linguistically complex outcome. While much of the promise of this work lies in measuring related constructs, our findings and implications may not apply to all other linguistic constructs. Even within the circle of investigators interested in measuring goals-of-care content, other operational definitions of the same construct are more amenable to measurement using rule-based and other methods.29–31 Differences in the performance of rule-based methods across these studies19,31 illustrates how minor differences in operational definitions (e.g., the inclusion vs. exclusion of routine code status discussions) can lead to important differences in the choice of best measurement tools. Second, all data were collected from a series of randomized trials of related interventions performed at a single multi-hospital health system in Washington State, which limits generalizability outside of this setting. Although this study does not account for the trial interventions, our understanding of the interventions (which are all low-touch communication prompting interventions), as well as qualitative work in progress, suggest that the interventions had very little systematic effect on the location and structure of clinicians’ goals-of-care documentation. Third, our held-out test set was incompletely adjudicated by humans due to its sheer size. However, we feel that the high expected sensitivity of our adjudication method for the held-out test set lends advantages in generalizability that far outweigh limitations in fidelity. This tension between scale and fidelity has long been known to the NLP community, and we anticipate that navigating this tension will continue to be an area of great interest in the intersection of NLP and epidemiology.32–34

Conclusion

In measuring documented goals-of-care discussions for hospitalized adults with serious illness, a zero-shot Llama 3.3 large language model with no task-specific training achieved comparable classification performance to a task-specific supervised-learning BERT model that had been trained on thousands of manually labeled EHR notes. The advent of large language models and their facilitation of zero-shot methods have important implications for clinical and health services researchers interested in leveraging the EHR to measure linguistically complex exposures and outcomes.

KEY POINTS.

Question:

Can newer large language AI models accurately measure documented goals-of-care discussions without task-specific training data?

Findings:

In this diagnostic/prognostic study, a publicly available large language model prompted with an outcome definition and no task-specific training demonstrated comparable performance identifying documented goals-of-care discussions to a previous deep-learning model that had been trained on an annotated corpus of 4,642 notes.

Meaning:

Natural language processing allows the measurement of previously-inaccessible outcomes for clinical research. Compared to traditional natural language processing and machine learning methods, newer large language AI models allow investigators to measure novel outcomes without needing costly training data.

Acknowledgement:

The authors are grateful for the contributions of the late J. Randall Curtis, MD, MPH, who was a founding principal investigator of this research program.

Funding/Support:

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (R01AG062441), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23HL161503, K12HL137940, T32HL125195), the National Palliative Care Research Center, and the Cambia Health Foundation. Infrastructure support was provided by the Institute of Translational Health Science (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, UL1TR002319).

Role of the Funder/Support:

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (R01AG062441), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23HL161503, K12HL137940, T32HL125195), the National Palliative Care Research Center, and the Cambia Health Foundation. Infrastructure support was provided by the Institute of Translational Health Science (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, UL1TR002319).

References

- 1.Wang Z, Chu Z, Doan TV, Ni S, Yang M, Zhang W. History, development, and principles of large language models: an introductory survey. AI Ethics. Published online October 14, 2024. doi: 10.1007/s43681-024-00583-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palatucci M., Pomerleau Dean, Hinton Geoffrey E., Mitchell Tom M.. Zero-shot Learning with Semantic Output Codes. In: Bengio Y., Schuurmans D., Lafferty J., Williams C., Culotta A., eds. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 22: 23rd Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2009, Vancouver, BC, Canada. Advances in neural information processing systems. Curran; 2010:1410–1418. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee RY, Brumback LC, Lober WB, et al. Identifying Goals of Care Conversations in the Electronic Health Record Using Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(1):136–142 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uyeda AM, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, et al. Mixed-methods evaluation of three natural language processing modeling approaches for measuring documented goals-of-care discussions in the electronic health record. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(6):e713–e723. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee RY, Kross EK, Torrence J, et al. Assessment of Natural Language Processing of Electronic Health Records to Measure Goals-of-Care Discussions as a Clinical Trial Outcome. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(3):e231204. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. Published online May 24, 2019. Accessed August 29, 2024. http://arxiv.org/abs/1810.04805

- 7.Alsentzer E, Murphy JR, Boag W, et al. Publicly Available Clinical BERT Embeddings. Published online June 20, 2019. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://arxiv.org/abs/1904.03323

- 8.Laparra E, Bethard S, Miller TA. Rethinking domain adaptation for machine learning over clinical language. JAMIA Open. 2020;3(2):146–150. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooaa010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee RY, Kross EK, Downey L, et al. Efficacy of a Communication-Priming Intervention on Documented Goals-of-Care Discussions in Hospitalized Patients With Serious Illness: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e225088. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.5088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtis JR, Lee RY, Brumback LC, et al. Intervention to Promote Communication About Goals of Care for Hospitalized Patients With Serious Illness: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2023;329(23):2028–2037. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.8812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis JR, Lee RY, Brumback LC, et al. Improving communication about goals of care for hospitalized patients with serious illness: Study protocol for two complementary randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2022;120:106879. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2022.106879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bandy Jack, Vincent Nicholas. Addressing “Documentation Debt” in Machine Learning: A Retrospective Datasheet for BookCorpus. In: Vanschoren J., Yeung S., eds. 35th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems Datasets and Benchmarks Track. ; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson AE, Pollard TJ, Shen L, et al. MIMIC-III, a freely accessible critical care database. Sci Data. 2016;3:160035. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alsentzer E. BioClinicalBERT. 2019. https://huggingface.co/emilyalsentzer/Bio_ClinicalBERT

- 15.Devlin Jacob, Chang Ming-Wei. Open Sourcing BERT: State-of-the-Art Pre-training for Natural Language Processing. 2018. https://research.google/blog/open-sourcing-bert-state-of-the-art-pre-training-for-natural-language-processing/

- 16.Cook J, Ramadas V. When to consult precision-recall curves. Stata J Promot Commun Stat Stata. 2020;20(1):131–148. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edmonds KP, Ajayi TA. Do We Know What We Mean? An Examination of the Use of the Phrase “Goals of Care” in the Literature. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(12):1546–1552. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myers J, Kim GL, Bytautas J, Webster F. Differing Conceptualizations of the Goals of Care Discussion: A Critical Discourse Analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(4):495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee RY, Uyeda AM, Li KS, et al. Performance of Predefined Search Patterns for Identifying Documented Goals-of-Care Discussions in Inpatient Electronic Health Records. J Palliat Med. Published online April 4, 2025. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2024.0496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Kruser JM, Benjamin BT, Gordon EJ, et al. Patient and Family Engagement During Treatment Decisions in an ICU: A Discourse Analysis of the Electronic Health Record. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(6):784–791. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhattarai K, Oh IY, Sierra JM, et al. Leveraging GPT-4 for identifying cancer phenotypes in electronic health records: a performance comparison between GPT-4, GPT-3.5-turbo, Flan-T5, Llama-3–8B, and spaCy’s rule-based and machine learning-based methods. JAMIA Open. 2024;7(3):ooae060. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooae060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiang CC, Luo M, Dumkrieger G, et al. A large language model-based generative natural language processing framework fine-tuned on clinical notes accurately extracts headache frequency from electronic health records. Headache. 2024;64(4):400–409. doi: 10.1111/head.14702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guevara M, Chen S, Thomas S, et al. Large language models to identify social determinants of health in electronic health records. NPJ Digit Med. 2024;7(1):6. doi: 10.1038/s41746-023-00970-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patra BG, Lepow LA, Kasi Reddy Jagadeesh Kumar P, et al. Extracting social support and social isolation information from clinical psychiatry notes: comparing a rule-based natural language processing system and a large language model. J Am Med Inform Assoc JAMIA. 2025;32(1):218–226. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocae260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu X, Li J, Liu Y, Ma C, Wang W. A Survey on Model Compression for Large Language Models. Trans Assoc Comput Linguist. 2024;12:1556–1577. doi: 10.1162/tacl_a_00704 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei J, Wang X, Schuurmans D, et al. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. In: Koyejo S, Mohamed S, Agarwal A, Belgrave D, Cho K, Oh A, eds. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Vol 35. Curran Associates, Inc.; 2022:24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gianfrancesco MA, Tamang S, Yazdany J, Schmajuk G. Potential Biases in Machine Learning Algorithms Using Electronic Health Record Data. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1544–1547. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamruzzaman M, Kim GL. Prompting Techniques for Reducing Social Bias in LLMs through System 1 and System 2 Cognitive Processes. Published online 2024. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2404.17218 [DOI]

- 29.Chien I, Shi A, Chan A, Lindvall C. Identification of Serious Illness Conversations in Unstructured Clinical Notes Using Deep Neural Networks. In: Koch Fernando, Koster Andrew, Bichindaritz Isabelle, Herrero Pau, et al. , eds. Artificial Intelligence in Health: First International Workshop, AIH 2018, Stockholm, Sweden, July 13–14, 2018, Revised Selected Papers. Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence. Springer Nature; Switzerland; 2019:199–212. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan A, Chien I, Moseley E, et al. Deep learning algorithms to identify documentation of serious illness conversations during intensive care unit admissions. Palliat Med. 2019;33(2):187–196. doi: 10.1177/0269216318810421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindvall C, Deng CY, Moseley E, et al. Natural Language Processing to Identify Advance Care Planning Documentation in a Multisite Pragmatic Clinical Trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(1):e29–e36. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poibeau T, Messiant C. Do we Still Need Gold Standards for Evaluation? In: Calzolari N, Choukri K, Maegaard B, et al. , eds. Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC ‘08). European Language Resources Association (ELRA); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Himmi A, Irurozki E, Noiry N, Clemencon S, Colombo P. Towards More Robust NLP System Evaluation: Handling Missing Scores in Benchmarks. Published online 2023. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2305.10284 [DOI]

- 34.Hoffman K, Salerno S, Afiaz A, Leek JT, McCormick TH. Do We Really Even Need Data? Published online February 2, 2024. Accessed August 29, 2024. http://arxiv.org/abs/2401.08702