Abstract

We report the cloning of the noisette gene (noi), which encodes the Drosophila melanogaster ortholog of a U2 snRNP-associated splicing factor, SF3a60 (SAP61) in humans and PRP9p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Antibodies raised against human SF3a60 recognized NOI in flies, showing a nuclear localization in all the stages examined, including the embryo, the dividing cells of imaginal discs, and the larval polyploid nuclei. NOI is expressed in somatic and germinal cells of both male and female gonads. By mobilization of P transposons, we have generated a large number of noi mutations. Complete loss of function resulted in lethality at the end of embryogenesis, without obvious morphological defects. Hypomorphic alleles revealed multiple roles of noi for the survival and differentiation of male germ cells, the differentiation of female germ cells, and the development of several adult structures.

The active spliceosome is assembled on pre-mRNAs through an ordered and regulated succession of steps, complexes E, A, B, and finally C, which involve the function of five small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles (U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6 snRNPs), as well as several non-snRNP polypeptides (for a review, see reference 30). Many of the proteins associated with spliceosome intermediates have been identified and called spliceosome-associated proteins (SAPs) (6, 62). Among them, SAP 61, 62, and 114 were isolated in all the splicing complexes containing the U2 snRNP (6). Fractionation of splicing extracts showed that two fractions associated with U2 snRNP, SF3a and SF3b, are required for the binding of U2 snRNP to pre-mRNAs (10, 31). SF3a contains three tightly associated subunits of 60, 66, and 120 kDa. Biochemical, immunological, and sequence analyses have revealed the correspondence of these three polypeptides with SAP 61, 62, and 114, respectively, and their homology to the essential yeast splicing proteins PRP9p, PRP11p, and PRP21p (4, 7, 9, 13, 32, 33). In yeast, evidence of direct interaction of these polypeptides as well as synthetic lethality between several U2 snRNA mutations and prp9, prp11, or prp21 mutations supports the hypothesis that these three polypeptides physically interact with stem-loop IIa of U2 snRNA and act interdependently to mediate the binding of U2 snRNP to pre-mRNA (36, 38, 53, 67). In addition, the invariant nucleotides located between the branchpoint interaction sequence and the beginning of stem IIa may also contribute to splicing via interaction with SF3a (68) instead of by base pairing with U6 snRNA as originally proposed (65). RNA-protein UV-cross-linking assays demonstrated that six U2 snRNP-associated proteins, including the three subunits of SF3a, contact the pre-mRNA around the intron branch site in a sequence-independent manner during assembly of spliceosomal complex A (22). This binding of U2 snRNP appears to allow base pairing between the U2 snRNA and the intron sequence leading to the bulging of the adenosine branch residue (43).

In Drosophila melanogaster, a few proteins involved in splicing have been identified. The gene sans fille (snf) encodes an essential nuclear protein thought to be the homolog of both U1A and U2B", which are associated with the U1 and U2 snRNPs, respectively (17, 24, 48). Genetic analysis of amorphic, hypomorphic, and antimorphic mutations revealed a prominent role of SNF in the regulation of alternative splicing of pre-mRNAs of the sex determination switch gene Sex-lethal (2, 42, 55, 56, 63). Another gene encoding a U1 snRNP polypeptide has been cloned in Drosophila, U1-70K (39). The U2 snRNP auxiliary factor, U2AF, composed of two subunits, assembles with U1 snRNP into prespliceosome complex E and is involved in the recruitment of U2 snRNP into complex A (for a review, see reference 30). The genes encoding both subunits, dU2AF50, homologous to human U2AF65 (26), and dU2AF38, homologous to human U2AF35 (54), have been cloned. Null mutations showed that both genes are essential for viability. Furthermore, a hypomorphic allele of dU2AF38 showed reduced viability and fertility as well as morphological defects (54).

Several genes encoding proteins involved in splice site selection and regulation of spliceosome assembly have also been characterized in Drosophila, including two members of the SR family (for reviews, see references 19 and 66): B52, the homolog of human SRp55 (12, 51), and RBP1, the homolog of human SRp20 (28). B52 is an essential gene (45, 49) whose precise levels of expression appear to be critical for the proper differentiation of various tissues (34). Although it has not been possible to detect splicing defects in null alleles of B52 (45, 49), effects on the splicing of several transcripts, including the alternatively spliced dsx pre-mRNA, were revealed with a dominant allele characterized by a single amino acid substitution in one of the RNA binding domains (45). In vitro, RBP1 was shown to affect both the efficiency of splicing and splice site selection (28). Further analysis in transfected tissue culture cells implicated RBP1 as a coregulator of dsx pre-mRNA alternative splicing, together with the products of the sex determination genes tra and tra-2 (25).

Several other genes encoding polypeptides related to SR proteins have been characterized. Genetic studies of sex determination have led to the detailed analysis of three genes, Sxl, tra, and tra-2, whose products are required in females to control a cascade of alternative splicing events (for reviews, see references 3 and 15). Two genes, which were identified as suppressors of various mutations, have been found to encode RNA binding proteins, which could regulate splice site selection of some pre-mRNAs: Su(s) (18, 41; but see also reference 20) and su(wa), which autoregulates its own expression by alternative splicing (68). In the latter case, a mammalian homolog has also been shown to be a regulator of alternative splicing (16, 57). Finally, the restriction of P elements’ transposition to the germ line occurs by inhibition of removal of the P-element third intron in somatic cells, an inhibition mediated by a ribonucleoprotein complex containing a tissue-specific regulator called PSI (1, 60).

The cloning of the noisette gene (noi) allowed us to isolate the Drosophila homolog of the 60-kDa (SAP 61) subunit of the U2 snRNP-associated splicing factor SF3a. This is the third gene encoding an snRNP-associated polypeptide cloned in Drosophila. Antibodies raised against human SF3a60 (32) showed ubiquitous expression and nuclear localization of NOI during fly development. Analysis of various noi mutations revealed multiple requirements of the gene for fly viability, morphology, and fertility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetics.

The noi1 and noi2 alleles were identified by screening a collection of homozygous male sterile mutations provided by M. Fuller (Stanford University). These mutations had been generated by mobilization of the P-lacW transposon, which is marked with a mini-white+ gene (8). The endogenous white locus was the w1118 allele. Precise and imprecise excisions of the noi1 and noi2 transposons were induced in the presence of the Sb P[ry+ Δ2-3] source of transposase (50) and selected on the basis of the loss of the eye color marker.

Genomic and cDNA clones.

A genomic library from the noi1 mutant was constructed by insertion of genomic DNA partially digested with Sau3A into the BamHI site of the λEMBL3 vector. Phages containing part of the P-lacW transposon were identified using a probe from the white gene, the 1.9-kb SacI fragment from CaSpeR (47), which is deleted in the w1118 allele. Genomic DNA of region 83B from the mutant phages was used to screen a wild-type genomic library (40). Ovarian (64) and 4- to 8-h embryonic (11) cDNA libraries were screened according to the authors’ instructions.

Southern and Northern blotting.

Genomic DNA was isolated as described by Bender et al. (5). RNA extraction and electrophoresis were done according to Cléard et al. (14). Poly(A)+ RNA was purified by using an Oligotex-dT kit (Qiagen). Blotting onto nylon membranes (Hybond-N+; Amersham) and hybridization were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Germ line transformation and rescue of noi mutations.

Germ line transformation was performed with a 3.6-kb PstI genomic fragment subcloned into the transformation vector CaSpeR (47). To test for the rescue of the noi phenotypes, lines with insertions on the X or on the second chromosome were used.

Sequencing.

Sequencing of cDNAs and of the 3.6-kb PstI genomic fragment was performed with Sequenase version 2.0 (U.S. Biochemicals) following the manufacturer’s instructions, either on subclones in pBluescript KS+ with the T3 or T7 primers or with internal oligonucleotide primers. The homology search was carried out with the BLAST program.

The site of the P-element insertion in the noi1 allele was determined by amplification and sequencing of a fragment spanning the insertion site. DNA from one of the mutant phages was digested with BamHI and PCR amplified with a primer from the P element (5′TTCCTTTCACTCGCACTTATTG, position 775 to 796 [52]) and a primer from the noi coding region, 300 bp upstream of the BamHI site (5′GGAGCAGGTAGTCGTTG). The amplified fragment was cloned into pBluescript KS+ and sequenced as described above.

The breakpoints of Df(3R)noi-D were determined by direct sequencing of a PCR-amplified mutant fragment. Amplification was performed with a primer located 400 bp upstream of the P-element insertion site (5′TACTTTTGCCTTCTGCC) and a primer located on the other side, near the stop codon (5′GAACGTCTTTCGGTTGAC). Direct sequencing of the PCR product was performed as above, in the presence of 10% dimethyl sulfoxide and 4 U of pyrophosphatase, by using 5 pmol of the latter primer and about 1 μg of the PCR product.

Antibody stainings.

Embryos and tissues were prepared as described by Pauli et al. (44) and Pennetta and Pauli (46). Methanol washing was omitted for testes stained against NOI. PBTX (phosphate-balanced buffer with 0.3% bovine serum albumin and 0.2% Triton X-100) was used for both primary and secondary antibody incubations. Antibodies preadsorbed on embryos were used at the following dilutions: rat anti-VASA (61), 1:500; and rabbit anti-human SF3a60 (32), 1:2,000. Secondary antibodies coupled to horseradish peroxidase (Bio-Rad) or fluorescein (Jackson Laboratory) were diluted 1:1,000.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence accession number for noi is AJ23042.

RESULTS

Isolation of the noisette (noi) gene.

In our study of germ line sex determination in D. melanogaster, we were interested in mutations with a male-specific germ cell death phenotype. The screening of a collection of P-element-induced male sterile mutations (kindly provided by M. Fuller) allowed us to identify two noncomplementing recessive mutations, noi1 and noi2, in which adult males showed very small testes, almost completely devoid of germ cells (for a detailed description of the phenotype, see below). Homozygous mutant females did not appear affected and were fertile at 25°C. Viability of both sexes was normal. At 18°C, both males and females were sterile.

The noi1 and noi2 had been generated by the mobilization of a mini-white+-marked P-transposon, P-lacW (8). In situ hybridization on polytene chromosomes located a single P-element insertion at 83B on the right arm of the third chromosome for both strains. The two alleles appeared to have an insertion at the same site, or at very close sites, as Southern blotting of genomic DNA showed junction fragments of identical size for the two lines (data not shown). To clone the genomic region encompassing the noi locus, a genomic library of noi1 was generated. Twelve phages with inserts covering the region of interest were isolated by screening the library with a fragment of the white gene. Appropriate fragments from these clones were then used to obtain approximately 38 kb of wild-type genomic DNA flanking the insertion site (Fig. 1).

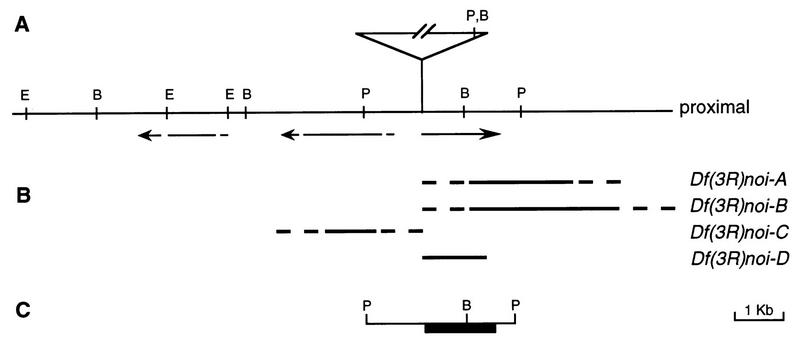

FIG. 1.

Molecular map of the noi region. (A) Thirteen kilobases around the site of the P-lacW insertions in noi1 and noi2, which are indicated by the triangle, is shown. Below the line, the arrows show the three transcription units located in the region. The two left arrows are interrupted to indicate that the position is approximate. (B) The four lines depict the deleted sequences in four imprecise excisions of the P elements. The uncertainties for three of the deletions are indicated by the broken lines. (C) The PstI genomic fragment, which rescues the noi mutations. The black box indicates the position of the open reading frame. B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; P, PstI.

In the next step, the transcript pattern was studied by using Northern blotting of poly(A)+ RNA extracted from ovaries, testes, and carcasses of adult wild-type flies. Genomic probes spanning the region surrounding the P-element insertion site hybridized with several transcripts between 1.5 and 2.5 kb in size. We could classify transcripts into three main groups according to their position, size, and pattern of expression, suggesting the presence of three different genes in the region. A more accurate localization of the three transcription units was obtained after screening of a cDNA library and mapping of those clones onto the noi genomic region. One of the transcription units lies on the proximal side (toward the centromere) of the P-transposon insertion, and the two others are located distally (Fig. 1). The two genes surrounding the insertion site are transcribed in opposite directions away from the transposon. Given that P elements frequently insert at the promoter region of genes, either of the flanking transcription units could be affected by the P-element insertion to yield the noi1 and noi2 male sterile phenotype. None of the three genes showed a testis-limited expression; they were also expressed in ovaries and gonadectomized adults. The identification of noi was pursued by two approaches: the generation and molecular characterization of new alleles, including deletions, and the rescue of the mutations by transformation with a genomic fragment.

Generation of additional alleles of noi.

The transposons in noi1 and noi2 were mobilized by crosses to a strain providing a source of transposase (50). Screening for excision or modification of the transposon was based on the loss of the white+ eye color marker. Over 400 independent lines were generated. They showed a variety of phenotypes. Several broad categories could be defined on the basis of their phenotype at 25°C.

The first class, comprising close to two-thirds of the lines, showed reversion of the male sterility to wild-type fertility in homozygotes. Some lines still showed reduced fertility or sterility when tested over a deficiency. Within the limit of resolution of our Southern analysis (about 50 bp) this class corresponds to the precise excision of the transposon. These revertants confirmed that the insertion of a P element at 83B was the cause of the noi1 and noi2 mutations.

About 15% of the strains fell into the second category, whose strains exhibited a phenotype similar to the original alleles, homozygous male sterility and female fertility. All 10 lines analyzed at the molecular level showed internal deletions of the transposon (both ends still present). An opposite phenotype, male fertility but female sterility (or reduced fertility), was observed for 1% of the lines (class 3). Another 2% of the strains (class 4) were homozygous sterile (or almost sterile) in both sexes. The latter two classes also appeared to bear internal deletions of the P element. In these three categories, viability was good.

A fifth class, composed of close to 15% of the lines, showed homozygous lethality. A variety of molecular alterations was found in these strains. In some cases, part of the P element was still present (both or only one of the extremities). In other lines, we could not detect any obvious alteration such as the presence of a piece of the transposon or the deletion of genomic DNA. Finally, four lines showed deletion of genomic sequences and no remains of the transposon (Fig. 1). Three lines, carrying Df(3R)noi-A, Df(3R)noi-B, and Df(3R)noi-D, had genomic sequences deleted from approximately the insertion site toward the centromere. The fourth line, carrying Df(3R)noi-C, had mainly distal sequences deleted.

The final category of lines, class 6, was quite heterogeneous in terms of viability (good to poor) and fertility (male sterile or sterile in both sexes). In some cases, females were less viable than males. They had visible phenotypes in common, such as a loss of macrochaetes and a reduction in the number of bristles of the male sex combs. These lines have not been analyzed at the molecular level.

Crosses between representative alleles of each class were performed at two temperatures and will be described elsewhere. Data relevant to the present study are presented in Table 1. Several deductions could be made from crosses between alleles of class 2 and the proximal and distal deletions. First, the mutations show clear cold sensitivity, the phenotypes being stronger at 18°C than at 25°C. Second, although male sterile alleles (class 2) show good viability and female fertility at 25°C as homozygotes, they are in fact affected in both aspects. In trans-heterozygotes with a deficiency, viability can be strongly reduced and even null for some crosses at 18°C. Lethality appears polyphasic, with some progeny being lost during the larval stages, others being lost during pupation, and some undergoing death soon after eclosion. In addition, development can be very slow (up to 50% slower) compared to heterozygous siblings. We conclude from these data that the male sterile mutations are hypomorphic and that noisette is an essential gene. Alteration of oogenesis was revealed by comparison of the progeny from heterozygous and homozygous females: phenotypes were always worse in the latter case, suggesting a strong maternal contribution. Similar conclusions could be made from the analysis of class 3, 4, and 6 alleles. Third, slight differences between the three proximal deletions and the distal one were observed at least in some crosses. For instance, viability, lethal phase, rates of development, or fertility were worse when class 2 or class 3 mutations were in trans with Df(3R)noi-A or Df(3R)noi-D (proximal) than with Df(3R)noi-C (distal). This suggested that noi lies proximal to the P-element insertion site.

TABLE 1.

Differences between proximal and distal deletionsa

| Maternal genotype | Temp (°C) | Heterozygous paternal genotype

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Df(3R)noi-D (proximal) | Df(3R)noi-C (distal) | ||

| Heterozygous noi2 | 25 | Slow, sterile | Sterile |

| 18 | sl, vslow, sterile | sl, vslow, sterile | |

| Homozygous noi2 | 25 | sl, vslow, sterile | sl?, sterile |

| 18 | l-late, vslow | sl, vslow, sterile | |

| Heterozygous noi12 | 25 | Slow, sterile | Sterile |

| 18 | l-mid-late, vslow | sl, vslow, sterile | |

| Homozygous noi12 | 25 | l-sl, vslow, sterile | Slow, sterile |

| 18 | l-3rd-early, vslow | l-mid, slow | |

noi2 and noi12 are class 2 alleles (male sterile at 25°C and sterile at 18°C). Slow means that the mutant flies developed about 20% more slowly than the heterozygous siblings; vslow, very slow (>30% slower); l, lethal; sl, semilethal (about 10 to 25% of the expected number of mutant adults); sl?, possible reduction of viability (about 50% of the expected level); l-sl, very rare eclosions; early, mid, and late, approximative stages of pupal lethality; 3rd, lethality during the third larval stage. Growth at 18°C was 2 days of egg laying at 25°C and then transfer at 18°C. Heterozygotes were balanced with TM6B, Hu e Tb.

Rescue of noisette mutations.

We tested the hypothesis that noi corresponded to the transcription unit proximal to the P-transposon insertion site by germ line transformation, to see whether a 3.6-kb genomic fragment could rescue noi mutant phenotypes. This fragment encompasses the entire proximal transcript but only a fraction of the distal transcription unit (Fig. 1). Several independent transformed lines were obtained and crossed to various noi alleles. All the phenotypes described above, lethality, sterility (sex specific or not), and visible defects were rescued by the transgene. The only unrescued phenotype was the lethality caused by homozygosity of the deletions Df(3R)noi-A, Df(3R)noi-B, and Df(3R)noi-C. We have evidence that either these deficiencies uncover additional essential genes or these chromosomes bear another lethal mutation elsewhere (data not shown). These rescue experiments clearly identified noi as the proximal transcription unit.

noi is homologous to the human SF3a60 gene.

cDNA clones corresponding to the 1.8-kb RNA of the proximal transcription unit were isolated from ovarian and 4- to 8-h embryonic libraries. They were found to be essentially the same, except for two polymorphisms in the 3′ untranslated region and different 5′ ends. We assume that the differences at the 5′ ends were likely to be due to incomplete reverse transcription. Differences in the coding region were not found. Comparison of the cDNA and genomic sequences showed an absence of introns. The P-element insertion in noi1 was found to lie 92 nucleotides upstream of the translation initiation codon. The longest three cDNA clones, whose sizes were close to those expected for full-length clones, as judged by comparison to the mRNA length, extended upstream of the insertion site. Another clone stopped one nucleotide downstream of the insertion site. Although we have not mapped more precisely the transcription initiation site(s), these data suggested that the P-element insertion in noi1 (and probably also noi2) was in the 5′ untranslated region.

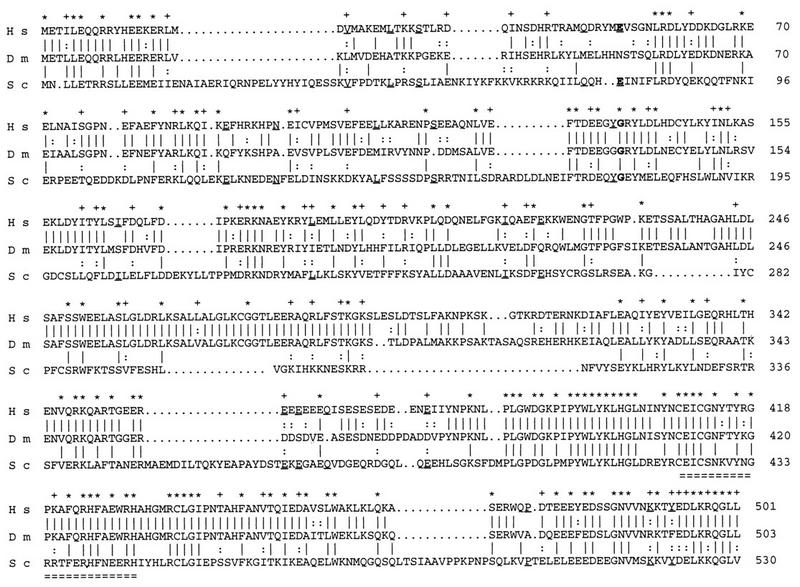

The deduced amino acid sequence revealed a polypeptide of 503 amino acids with extensive homology to an essential U2 snRNP-associated polypeptide, the 60-kDa subunit of human splicing factor SF3a (32), also called SAP 61 (13) (66% identity), and to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae PRP9p protein (37) (26% identity) (Fig. 2). Identity among the three proteins is 23%. Homology runs along the entire length of the polypeptides with a few particularly noticeable regions. The highest conservation, close to 50% identity among the three species, resides in an about-120-residue C-terminal region, which contains a conserved C2H2 zinc finger-like motif. Another putative zinc finger found in PRP9p but not in SF3a60 (32) is also absent in NOI. Instead, this region shows a striking conservation between human and Drosophila (98% identity between amino acids 241 and 292).

FIG. 2.

Alignments of the deduced amino acid sequences of human SF3a60 (H s), Drosophila NOI (D m), and S. cerevisiae PRP9p (S c). Identical amino acids between SF3a60 and NOI or between NOI and PRP9p are indicated by a vertical line, and conservative changes (D and E; K and R; N and Q; I, L, and V; S and T; F and Y) are indicated by a colon. Identities between SF3a60 and PRP9p not found in NOI are underlined. Stars above the sequences indicate identical residues among the three species. Conservative changes are shown by the plus signs. The amino acids substituted in the two yeast prp9 thermosensitive alleles are shown in bold. Residue 78 mutated in prp9-1 (37) is conserved in human but not in Drosophila, while residue 177 mutated in prp9-2 (38) is conserved in the three species. The putative zinc finger is doubly underlined.

Expression pattern of NOI.

Given the high level of conservation described above, a polyclonal antibody raised against human SF3a60 (32) was tested on Drosophila tissues. Immunostainings on wild-type embryos showed a prominent and ubiquitous nuclear localization throughout embryogenesis (Fig. 3), except during the very early syncytial stages, during which strong cytoplasmic staining was also observed. Specificity of the antiserum was verified on embryos which were homozygous mutants for one of the proximal deficiencies. No difference was seen during early embryogenesis, a fact that we attributed to the large amount of protein coming from maternal contribution. However, starting at the beginning of germ band retraction, staining of homozygous embryos started to fade and had almost completely disappeared by the end of germ band retraction (data not shown), thus confirming that the antibody recognized NOI. In addition, Western blots of wild-type embryonic nuclear extracts revealed a single band of about 60 kDa, which is almost exactly the expected size (data not shown).

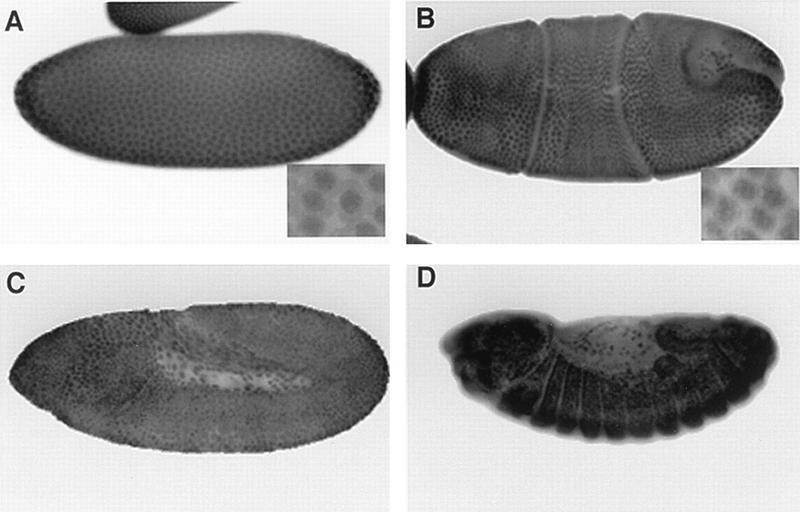

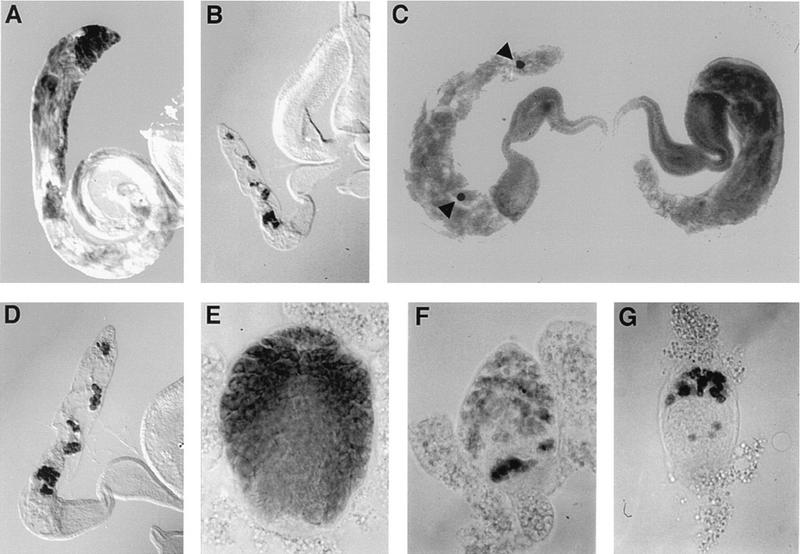

FIG. 3.

Expression of NOI during embryogenesis as revealed by whole-mount immunostaining with an antibody against human SF3a60. Four stages are shown. (A) Syncytial blastoderm, early stage 4. (B) Beginning of gastrulation, stage 6. Note that all the cells contain NOI, including the pole cells. (C) Slow phase of germ band elongation, stage 9. (D) End of germ band retraction, late stage 12 to early stage 13. Insets are fourfold enlargements showing the predominantly nuclear localization.

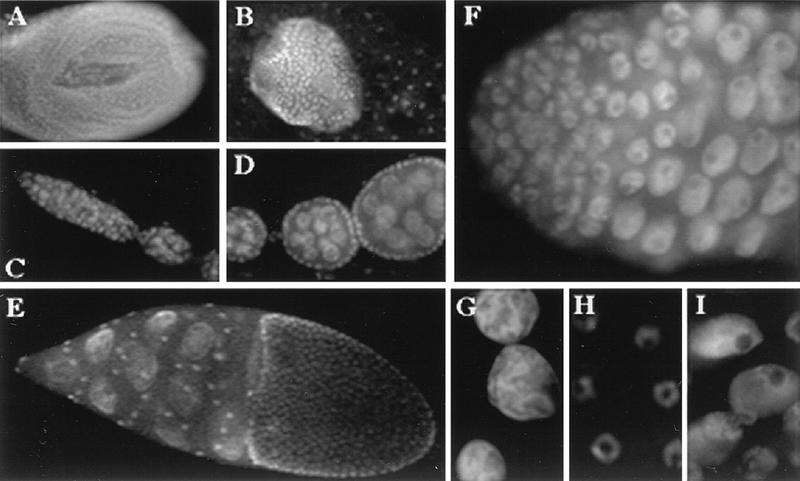

NOI protein was detected in the nuclei of all the cells examined, although the levels of expression were variable. Expression was strong and at a rather uniform level in all the cells of larval imaginal discs (Fig. 4A). Strong staining was observed in the germ cells of larval testes, but expression appeared weaker in fat body cells surrounding the gonads (Fig. 4B). Relatively weak expression was also found in other larval tissues, including the polyploid nuclei of salivary glands and the diploid nuclei of the brain (data not shown). Because of the phenotypes described below, we also examined the expression of NOI in adult gonads. In ovaries, expression was detected in all the germ cells and probably all the somatic cells (Fig. 4C to E). In testes, the protein was also found in somatic and germ line cells. In particular, strong staining was detected in all the premeiotic stages, including the stem cells, the spermatogonia, and the spermatocytes (Fig. 4F). It should be noted that the nuclear staining was not uniform and that NOI appeared to be completely excluded from nucleoli (Fig. 4G to I).

FIG. 4.

Expression of NOI in wild-type third-instar larval tissues and adult gonads. (A) A larval leg imaginal disc. Note that all the nuclei show staining at a similar intensity. (B) A larval testis, surrounded by a piece of fat body. Very intense staining was observed in germ cells. (C to E) Different stages from an adult ovary. (C) A germarium containing the germ line and follicle stem cells and assembling egg chambers. (D) Late previtellogenic egg chambers containing the germ line nurse cells surrounded by a layer of follicle cells. (E) A stage 10 egg chamber. (F) Tip of an adult testis showing the expression of NOI in germ line stem cells, spermatogonia, and primary spermatocytes. (G to I) Enlargements of nuclei from nurse cells (G), follicle cells (H), and primary spermatocytes (I), showing the nonuniform nuclear distribution of NOI and its absence from nucleoli.

Mutant phenotypes.

The null phenotype of noi was determined by using the deletions described in Fig. 1. Combinations of mutations that could be rescued to viability with the noi+ transgene, that is, trans-heterozygotes between proximal and distal deletions or homozygotes Df(3R)noi-D, were used and gave identical results. Embryonic development seemed completely normal, producing embryos of apparently wild-type morphology. Nevertheless, these embryos failed to hatch, although they stayed alive and moved in the egg shell for a few hours. This phenotype certainly corresponds to a complete zygotic loss of function of noisette, since Df(3R)noi-D was found to be a DNA null allele, having 1,485 bp of genomic DNA entirely proximal to the P-element site of insertion deleted, that is, 92 nucleotides upstream of the start codon to 117 nucleotides upstream of the stop codon.

The consequence of loss of noisette in the male germline was studied in detail for three of the male sterile (class 2) alleles, noi1 and noi2, the original mutations, and noi12, one of the derivatives showing an internal deletion of P-element sequences. Homozygous adult males showed small testes of a size comparable to that found in mutants completely devoid of a germ line. By phase-contrast microscopy only rare spermatocytes could be found. Exceptionally, some scarce nonmotile sperm were also present. The phenotype observed in homozygous males was probably close to a complete zygotic loss of function of noi in the male germ line, since it appeared almost as severe as the phenotype observed for the same alleles in hemizygotes.

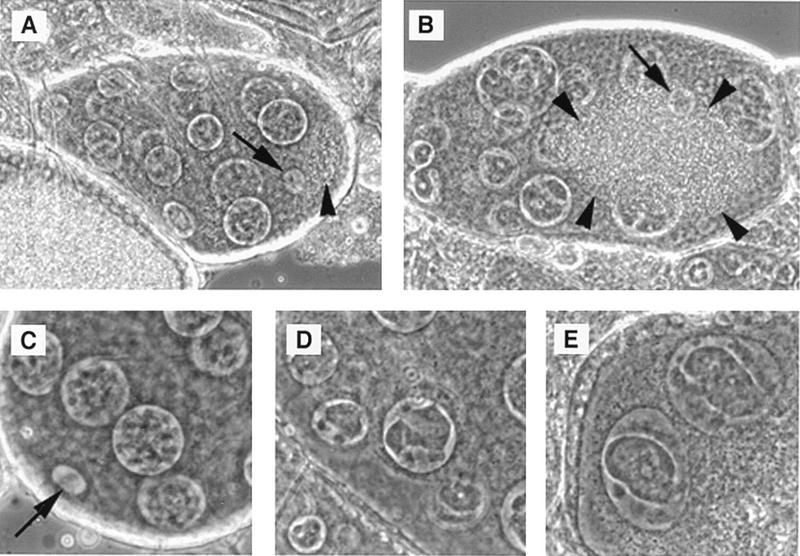

Staining with an antibody against the germ cell-specific VASA protein (35) was used to analyze more precisely the germinal content of the testes. Figure 5 illustrates the phenotype observed in 3- to 4-day-old homozygous adults. In the worst case, germ cells were completely absent. In less defective gonads, stem cells at the tip of the testes were missing, but a few groups of spermatogonia and/or spermatocytes could be found. No complete cysts of 16 spermatocytes or 64 spermatids have been seen, although the occasional presence of sperm suggests that normal cysts probably exist at low frequency, possibly earlier during development. Additional evidence of a degradation of the germ line with aging is provided by the percentage of completely empty gonads. In one experiment at 25°C, homozygous noi2 males showed 32% of empty testes 1 to 2 days after eclosion and 63% after 5 to 6 days. The noi12 allele appeared even more defective, with 88% of testes completely devoid of germ cells at 1 to 2 days and 99% after 5 to 6 days. Cysts of spermatocytes were also less numerous and contained fewer cells in noi12 than noi2 homozygotes. The loss of germ cells is probably due to autonomous lack of noi activity, since testis somatic cells appeared normal. In particular, the cells of the hub, which are in very close contact with the germ line stem cells, were present as revealed by staining with an antibody against fasciclin III, and the hub was slightly larger and displaced from the testis apex, as was shown for gonads completely devoid of germ cells (21) (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

noi male sterile phenotype. Germ cells were stained with an antibody against the VASA protein. (A) Low magnification of a wild-type adult testis. Note the elongated coiled morphology which accommodates the long sperm tails. (B) Same magnification of a mutant adult testis. Note the small size of the gonad, the absence of posterior coiling, and the rare germ cells. (C and D) Higher magnification of mutant adult testes showing the range of germ line defects: one gonad completely empty (C, right), one gonad with two isolated spermatocytes (arrowheads, C, left), and one gonad with several incomplete cysts containing fewer than 16 spermatocytes (D). (E through G) A wild-type (E) and two mutant (F and G) testes from late third-instar larvae (anterior ends up). Mutant genotypes were homozygous w1118;noi2 (B, C, D, and F) and homozygous w1118;noi12 (G).

The effect of these mutations could be detected earlier in development. The size of testes from third-instar larvae was at best half that of a wild type (Fig. 5). The pool of stem cells at the distal tip of the gonad was already depleted or reduced. A reduced number of primary spermatocytes was also observed, and cysts appeared incomplete and more or less disorganized. Like in adults, defects in noi12 were slightly more pronounced than in the original noi1 and noi2 alleles.

Sterility or reduced fertility was observed in females homozygous for a few of the P-element excision derivatives as well as in several trans-allelic combinations, such as the class 2 male sterile mutations over a deficiency. In no case have we observed female germ line death or any evidence of overall decreased numbers of germ cells. However, this does not rule out a requirement of noi for the survival of the female germ cells, because we probably do not have null mutations specific for the female germ line. Oogenic defects ranged from arrest before vitellogenesis to the production of apparently normal eggs, which were laid but did not develop. The strongest phenotype that we observed was a block of oogenesis around stage 6 or 7, leading to the accumulation of egg chambers showing several striking defects. The number of nurse cells per cyst was sometimes reduced and their nuclei contained a few spherical or elongated aggregates, instead of the normal filamentous appearance seen under phase microscopy (Fig. 6). It should be noted that those aggregates did not exactly resemble any of the different types of chromosome condensation seen during the previtellogenic stages of differentiation (27, 29). The oocyte nucleus was sometimes absent or mislocalized, which could lead to yolk accumulation in the middle of the egg chamber (Fig. 6). Late defects included short and/or flaccid eggs, showing fused, short, or no dorsal appendages.

FIG. 6.

noi female sterile phenotype. A stage 8 wild-type egg chamber showing the posterior localization of the oocyte nucleus (arrow) and the beginning of yolk accumulation (arrowhead). (B) A mutant egg chamber with central oocyte nucleus (arrow) and yolk accumulation (delimitated by arrowheads). (C) The posterior end of a stage 7 wild-type egg chamber showing the oocyte nucleus (arrow) and the filamentous aspect of chromatin in nurse cell nuclei. (D and E) Examples of abnormal chromatin condensation in mutant nurse cells. The mutant genotype was w1118;noi22/Df(3R)noi-A.

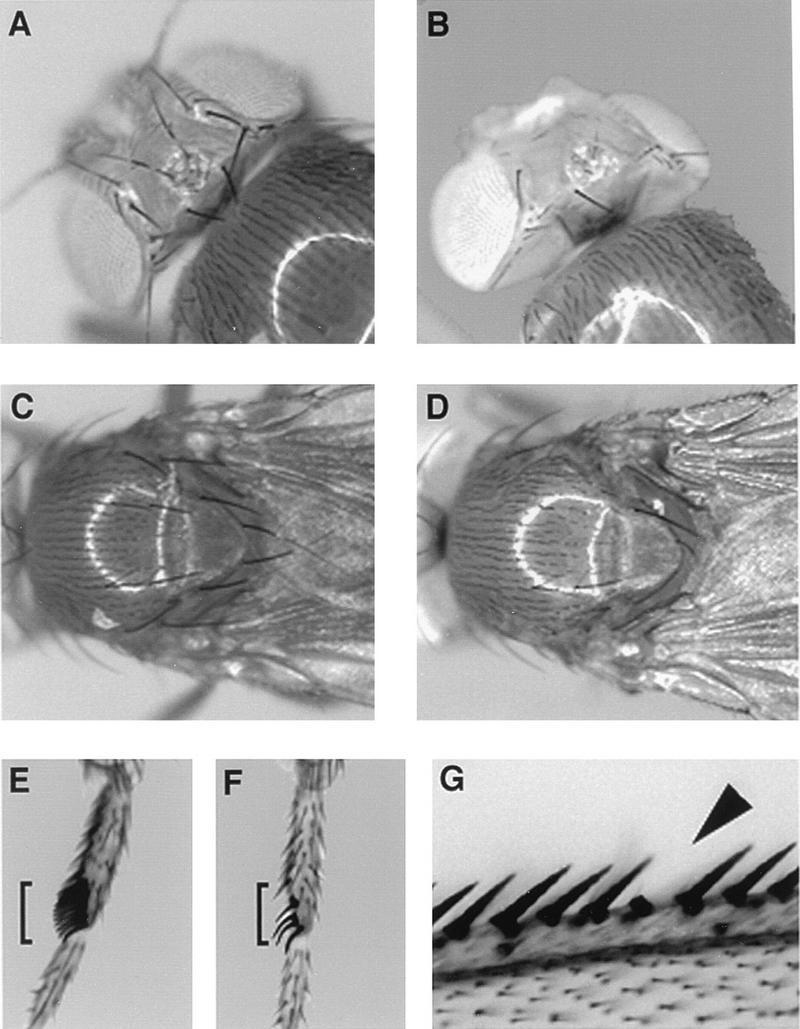

Finally, some homozygous lines showed several morphologic adult abnormalities. A common theme was the partial loss of several types of the largest body bristles (Fig. 7). Typically, a variable number of the head and thoracic macrochaetes were missing. We did not notice a strict order of disappearance, although some bristles appeared to be absent more frequently than others. For example, the posterior scutellar macrochaetes may be more sensitive than the anterior scutellar macrochaetes. The affected bristles were either absent or, occasionally, short and thin. In addition, the socket could also be missing. Another structure showing a striking reduction in the number of bristles was the male sex comb. Finally, medial bristles of the triple row at the anterior wing margin could be absent or short. These alterations were clearly not due to complete loss of function of noi in the affected cells since the frequency of missing bristles increased dramatically when the same alleles were tested in hemizygotes.

FIG. 7.

Bristle loss in homozygous noi20 adults. (A and B) Wild-type and mutant heads, respectively. Note the loss of several macrochaetes on the dorsal side. (C and D) Wild-type and mutant dorsal thoraxes, respectively. (E and F) Wild-type and mutant first legs of males, respectively. Note that this mutant sex comb showed only 4 bristles instead of 12 to 14 (sex combs are indicated with brackets). (G) Part of the anterior margin of a mutant wing. The arrowhead points to a missing bristle from the median row. Note that in this example, the socket was present.

DISCUSSION

While many genes encoding proteins involved in splice site selection in constitutive and/or alternative splicing have been analyzed in Drosophila (see the introduction), only two genes encoding snRNP-associated proteins have been identified so far, U1-70K (39) and snf (17, 24). Close homology to both the U1A and U2B" polypeptides suggested that SNF is one of the tightly associated components of either the U1 snRNP or the U2 snRNP, or both, and recent biochemical analysis indicates that it is part of the U1 and U2 snRNPs (48). We describe the cloning and genetic characterization of a third gene, noi, encoding an snRNP-associated polypeptide.

Drosophila NOI and human SF3a60 have similar sizes and show a high level of homology throughout their entire length. The Drosophila and human polypeptides appear to be equally distant from the yeast homolog PRP9p (26 and 27% identity, respectively). Most of the residues conserved between yeast and Drosophila or between yeast and human are in fact identical in the three species. This comparison may identify a basic structural and functional core. However, we also noticed that the amino acid mutated in one of the yeast mutations, prp9-1 (37), is conserved in SF3a60 but not in NOI. The highest domain of homology among the three species corresponds to the 120 C-terminal residues. This region includes a putative zinc finger, which has been shown by site-directed mutagenesis to be essential (37). Functionality across species was demonstrated by swapping a fragment of 46 amino acids including the putative zinc finger from SF3a60 into PRP9p (32). The role of the putative zinc finger is unknown although binding to the partner SF3a120 (SAP 114)-yeast PRP21p− has been excluded (13, 36, 38). An obvious alternative is the binding to the U2 snRNA or to pre-mRNA. The latter possibility seems particularly attractive since experiments of UV cross-linking of partially purified splicing complexes showed strong binding of SAP 61 at about 15 nucleotides upstream of the branchpoint (22). Strong conservation between Drosophila and human is observed along the entire length of the polypeptides, unlike PRP9, which shows about 50% identity in the C-terminal domain but less than 20% in the rest of the protein. In particular, a domain of 52 amino acids in the middle of the sequence is completely conserved between Drosophila and human, but absent in yeast. It would be interesting to test whether the human protein is functional in Drosophila.

Our genetic analysis suggests a surprising complexity in the requirement for noi during fly development. Complete zygotic loss of function resulted in a simple phenotype, lethality at the end of embryogenesis, without obvious morphological defects. This late stage of lethality is probably due to the large and quite stable maternal contribution. In fact, NOI antigen could be detected in mutant embryos for at least half of embryogenesis. Embryonic lethality was also found in snf null mutants (17), while lethality was observed during the first larval stage in mutants with mutations in other splicing factors, such as dU2AF50 (26), dU2AF38 (54), B52 (49), or hrp48 (23).

Hypomorphic alleles showed a variety of phenotypes, which may reflect different sensitivities of different tissues to partial loss of function of noi. Hints of the existence of variable quantitative requirements were provided by the observation that the level of expression of NOI was not completely uniform. For instance, the male germ cells were found to contain very large amounts of NOI. Our mutation analysis suggested that the survival of the male germ cells may be very sensitive to the lack of noi. One trivial hypothesis would be that this apparent sensitivity of the male germ line is a bias of the mutations that were analyzed. It is possible that the P-element insertions reduce noi activity more strongly in the male germ line than in other tissues. However, it is plausible that the development of the male germ line requires very large amounts of some spliceosomal components. In mammals, extremely high levels of overexpression, close to 3 orders of magnitude, have been found in male germ cells for some components of the transcriptional machinery (58, 59), but it is not known whether this overexpression is functionally significant. A third possibility would be that the processing of some transcripts encoding products required for male germ cell survival is very sensitive to the level of the U2 snRNP.

The morphological phenotypes produced by some noi alleles are reminiscent of those produced by altered expression of other splicing factors. Abnormal sex combs with fewer and thinner bristles have been reported for a partial loss of function of dU2AF38 and has been interpreted to be due to an inability to splice one or more pre-mRNAs needed for sex comb differentiation (54). It is interesting that U2AF is the factor that recruits the U2 snRNP during the transition from the E to the A spliceosomal complexes. Decreased amounts of U2AF could therefore lead to an effect similar to that of reduced U2 snRNP activity.

A hypomorphic mutation of the hrp48 gene, which encodes a heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle protein, was found to cause the absence of one specific macrochaete, the posterior supra alar (23). Alteration of noi activity had a broader effect, deleting more bristles, without evidence of a stronger sensitivity of the posterior supra alar macrochaete. Strong loss of macrochaetes has been produced by overexpression of the SR protein B52 (34). SR proteins have been implicated in splice site selection during spliceosome assembly in both constitutive and alternative splicing, and the balance between various SR proteins in different cell types appears to strongly influence the selection (for reviews, see references 19 and 66). As for the sex combs, the loss of macrochaetes might be due to decreased splicing of one or a few pre-mRNAs encoding key products necessary for bristle differentiation. Alternatively, the occasional thin macrochaetes and the low growth rates could also be explained by a general reduction of metabolism. The fact that the larger bristles in various regions of the body are affected, but not smaller bristles, would support this hypothesis. Of course this idea is compatible with the possibility that some pre-mRNAs could be very sensitive to a decreased activity of U2 snRNP. Finally, it should be noted that the noi morphological defects are unlike the phenotype caused by Minute mutations, which consists of delayed development and short slender bristles, already observed in heterozygous conditions. Further work will be needed to understand the exact effect of particular noi mutations during fly development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant of the Swiss Science Foundation to D.P.

We thank Margaret T. Fuller for allowing us to screen her collection of P-element-induced male sterile mutants. We are grateful to Angela Krämer and Paul Macdonald for antibodies and to Angela Krämer for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams M D, Tarng R S, Rio D C. The alternative splicing factor PSI regulates P-element third intron splicing in vivo. Genes Dev. 1997;11:129–138. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albrecht E B, Salz H K. The Drosophila sex determination gene snf is utilized for the establishment of the female-specific splicing pattern of Sex-lethal. Genetics. 1993;134:801–807. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker B S. Sex in flies: the splice of life. Nature (London) 1989;340:521–524. doi: 10.1038/340521a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behrens S E, Galisson F, Legrain P, Lührmann R. Evidence that the 60-kDa protein of 17S U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein is immunologically and functionally related to the yeast PRP9 splicing factor and is required for the efficient formation of prespliceosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8229–8233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bender W, Spierer P, Hogness D S. Chromosomal walking and jumping to isolate DNA from the Ace and rosy loci and the bithorax complex in Drosophila melanogaster. J Mol Biol. 1983;168:17–33. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80320-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett M, Michaud S, Kingston J, Reed R. Protein components specifically associated with prespliceosome and spliceosome complexes. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1986–2000. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett M, Reed R. Correspondence between a mammalian spliceosome component and an essential yeast splicing factor. Science. 1993;262:105–108. doi: 10.1126/science.8211113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bier E, Vaessin H, Shepherd S, Lee K, McCall K, Barbel S, Ackerman L, Carretto R, Uemura T, Grell E, Jan L Y, Jan Y N. Searching for pattern and mutation in the Drosophila genome with a P-lacZ vector. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1273–1287. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.9.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brosi R, Gröning K, Behrens S E, Lührmann R, Krämer A. Interaction of mammalian splicing factor SF3a with U2 snRNP and relation of its 60-kD subunit to yeast PRP9. Science. 1993;262:102–105. doi: 10.1126/science.8211112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brosi R, Hauri H P, Krämer A. Separation of splicing factor SF3 into two components and purification of SF3a activity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:17640–17646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown N H, Kafatos F C. Functional cDNA libraries from Drosophila embryos. J Mol Biol. 1988;203:425–437. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Champlin D T, Frasch M, Saumweber H, Lis J T. Characterization of a Drosophila protein associated with boundaries of transcriptionally active chromatin. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1611–1621. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiara M D, Champion-Arnaud P, Buvoli M, Nadal-Ginard B, Reed R. Specific protein-protein interactions between the essential mammalian spliceosome-associated proteins SAP 61 and SAP 114. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6403–6407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cléard F, Matsarskaia M, Spierer P. The modifier of position-effect variegation Suvar(3)7 of Drosophila: there are two alternative transcripts and seven scattered zinc fingers, each preceded by a tryptophan box. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:796–802. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.5.796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cline T W, Meyer B J. Vive la difference: males vs females in flies vs worms. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:637–702. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denhez F, Lafyatis R. Conservation of regulated alternative splicing and identification of functional domains in vertebrate homologs to the Drosophila splicing regulator, suppressor-of-white-apricot. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16170–16179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flickinger T W, Salz H K. The Drosophila sex determination gene snf encodes a nuclear protein with sequence and functional similarity to the mammalian U1A snRNP protein. Genes Dev. 1994;8:914–925. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.8.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fridell R A, Searles L L. Evidence for a role of the Drosophila melanogaster suppressor of sable gene in the pre-mRNA splicing pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:859–867. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu X D. The superfamily of arginine/serine-rich splicing factors. RNA. 1995;1:663–680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geyer P K, Chien A J, Corces V G, Green M M. Mutations in the su(s) gene affect RNA processing in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7116–7120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gönczy P, Viswanathan S, DiNardo S. Probing spermatogenesis in Drosophila with P-element enhancer detectors. Development. 1992;114:89–98. doi: 10.1242/dev.114.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gozani O, Feld R, Reed R. Evidence that sequence-independent binding of highly conserved U2 snRNP proteins upstream of the branch site is required for assembly of spliceosomal complex A. Genes Dev. 1996;10:233–243. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammond L E, Rudner D Z, Kanaar R, Rio D C. Mutations in the hrp48 gene, which encodes a Drosophila heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle protein, cause lethality and developmental defects and affect P-element third-intron splicing in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:7260–7267. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harper D S, Fresco L D, Keene J D. RNA binding specificity of a Drosophila snRNP protein that shares sequence homology with mammalian U1-A and U2-B" proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3645–3650. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.14.3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinrichs V, Baker B S. The Drosophila SR protein RBP1 contributes to the regulation of doublesex alternative splicing by recognizing RBP1 RNA target sequences. EMBO J. 1995;14:3987–4000. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00070.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanaar R, Roche S E, Beall E L, Green M R, Rio D C. The conserved pre-mRNA splicing factor U2AF from Drosophila: requirement for viability. Science. 1993;262:569–573. doi: 10.1126/science.7692602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keyes L N, Spradling A C. The Drosophila gene fs(2)cup interacts with otu to define a cytoplasmic pathway required for the structure and function of germ-line chromosomes. Development. 1997;124:1419–1431. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.7.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim Y J, Zuo P, Manley J L, Baker B S. The Drosophila RNA-binding protein RBP1 is localized to transcriptionally active sites of chromosomes and shows a functional similarity to human splicing factor ASF/SF2. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2569–2579. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King R C. Ovarian development in Drosophila melanogaster. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krämer A. The structure and function of proteins involved in mammalian pre-mRNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:367–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krämer A, Utans U. Three protein factors (SF1, SF3 and U2AF) function in pre-splicing complex formation in addition to snRNPs. EMBO J. 1991;10:1503–1509. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07670.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krämer A, Legrain P, Mulhauser F, Gröning K, Brosi R, Bilbe G. Splicing factor SF3a60 is the mammalian homologue of PRP9 of S. cerevisiae: the conserved zinc finger-like motif is functionally exchangeable in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5223–5228. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.24.5223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krämer A, Mulhauser F, Wersig C, Gröning K, Bilbe G. Mammalian splicing factor SF3a120 represents a new member of the SURP family of proteins and is homologous to the essential splicing factor PRP21p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA. 1995;1:260–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kraus M E, Lis J T. The concentration of B52, an essential splicing factor and regulator of splice site choice in vitro, is critical for Drosophila development. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5360–5370. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lasko P F, Ashburner M. Posterior localization of vasa protein correlates with, but is not sufficient for, pole cell development. Genes Dev. 1990;4:905–921. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.6.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Legrain P, Chapon C. Interaction between PRP11 and SPP91 yeast splicing factors and characterization of a PRP9-PRP11-SPP91 complex. Science. 1993;262:108–110. doi: 10.1126/science.8211114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Legrain P, Choulika A. The molecular characterization of PRP6 and PRP9 yeast genes reveals a new cysteine/histidine motif common to several splicing factors. EMBO J. 1990;9:2775–2781. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07465.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Legrain P, Chapon C, Galisson F. Interactions between PRP9 and SPP91 splicing factors identify a protein complex required in prespliceosome assembly. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1390–1399. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mancebo R, Lo P C H, Mount S M. Structure and expression of the Drosophila melanogaster gene for the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle 70K protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:2492–2502. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.6.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maniatis T, Hardison R C, Lacy E, Lauer J, O’Connell C, Quon D, Sim G K, Efstratiadis A. The isolation of structural genes from libraries of eucaryotic DNA. Cell. 1978;15:687–701. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murray M V, Turnage M A, Williamson K J, Steinhauer W R, Searles L L. The Drosophila Suppressor of sable protein binds to RNA and associates with a subset of polytene chromosome bands. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2291–2300. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oliver B, Perrimon N, Mahowald A P. Genetic evidence that the sans fille locus is involved in Drosophila sex determination. Genetics. 1988;120:159–171. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pascolo E, Séraphin B. The branchpoint residue is recognized during commitment complex formation before being bulged out of the U2 snRNA–pre-mRNA duplex. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3469–3476. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pauli D, Tonka C-H, Tissières A, Arrigo A-P. Tissue-specific expression of the heat shock protein HSP27 during Drosophila melanogaster development. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:817–828. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peng X, Mount S M. Genetic enhancement of RNA-processing defects by a dominant mutation in B52, the Drosophila gene for an SR protein splicing factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6273–6282. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pennetta G, Pauli D. stand still, a Drosophila gene involved in the female germline for proper survival, sex determination and differentiation. Genetics. 1997;145:975–987. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.4.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pirrotta V. Vectors for P-mediated transformation in Drosophila. In: Rodriguez R L, Denhardt D T, editors. Vectors: a survey of molecular cloning vectors and their uses. Boston, Mass: Butterworths; 1988. pp. 437–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Polycarpou-Schwarz M, Gunderson S I, Kandels-Lewis S, Seraphin B, Mattaj I W. Drosophila SNF/D25 combines the functions of the two snRNP proteins U1A and U2B" that are encoded separately in human, potato, and yeast. RNA. 1996;2:11–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ring H Z, Lis J T. The SR protein B52/SRp55 is essential for Drosophila development. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7499–7506. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robertson H M, Preston C R, Phillis R W, Johnson-Schlitz D M, Benz W K, Engels W R. A stable genomic source of P element transposase in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1988;118:461–470. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roth M B, Zahler A M, Stolk J A. A conserved family of nuclear phosphoproteins localized to sites of polymerase II transcription. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:587–596. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.3.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rubin G M, Spradling A C. Vectors for P element-mediated gene transfer in Drosophila. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:6341–6351. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.18.6341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruby S W, Chang T H, Abelson J. Four yeast spliceosomal proteins (PRP5, PRP9, PRP11, and PRP21) interact to promote U2 snRNP binding to pre-mRNA. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1909–1925. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rudner D Z, Kanaar R, Breger K S, Rio D C. Mutations in the small subunit of the Drosophila U2AF splicing factor cause lethality and developmental defects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10333–10337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salz H K. The genetic analysis of snf: a Drosophila sex determination gene required for activation of Sex-lethal in both the germline and the soma. Genetics. 1992;130:547–554. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.3.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salz H K, Flickinger T W. Both loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations in snf define a role for snRNP proteins in regulating Sex-lethal pre-mRNA splicing in Drosophila development. Genetics. 1996;144:95–108. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sarkissian M, Winne A, Lafyatis R. The mammalian homolog of suppressor-of-white-apricot regulates alternative mRNA splicing of CD45 exon 4 and fibronectin IIICS. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31106–31114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schmidt E E, Schibler U. High accumulation of components of the RNA polymerase II transcription machinery in rodent spermatids. Development. 1995;121:2373–2383. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmidt E E, Schibler U. Developmental testis-specific regulation of mRNA levels and mRNA translational efficiencies for TATA-binding protein mRNA isoforms. Dev Biol. 1997;184:138–149. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Siebel C W, Admon A, Rio D C. Soma-specific expression and cloning of PSI, a negative regulator of P element pre-mRNA splicing. Genes Dev. 1995;9:269–283. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith J L, Wilson J E, Macdonald P M. Overexpression of oskar directs ectopic activation of nanos and presumptive pole cell formation in Drosophila embryos. Cell. 1992;70:849–859. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Staknis D, Reed R. Direct interactions between pre-mRNA and six U2 small nuclear ribonucleoproteins during spliceosome assembly. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2994–3005. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Steinmann-Zwicky M. Sex determination in Drosophila: the X-chromosomal gene liz is required for Sxl activity. EMBO J. 1988;7:3889–3898. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stroumbakis N D, Li Z, Tolias P P. RNA- and single-stranded DNA-binding (SSB) proteins expressed during Drosophila melanogaster oogenesis: a homolog of bacterial and eukaryotic mitochondrial SSBs. Gene. 1994;143:171–177. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun J S, Manley J L. A novel U2-U6 snRNA structure is necessary for mammalian mRNA splicing. Genes Dev. 1995;9:843–854. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.7.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Valcárcel J, Green M R. The SR protein family: pleiotropic functions in pre-mRNA splicing. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wells S E, Ares M., Jr Interactions between highly conserved U2 small nuclear RNA structures and Prp5p, Prp9p, Prp11p, and Prp21p proteins are required to ensure integrity of the U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6337–6349. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yan D, Ares M., Jr Invariant U2 RNA sequences bordering the branchpoint recognition region are essential for interaction with yeast SF3a and SF3b subunits. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:818–828. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zachar Z, Chou T B, Kramer J, Mims I P, Bingham P M. Analysis of autoregulation at the level of pre-mRNA splicing of the suppressor-of-white-apricot gene in Drosophila. Genetics. 1994;137:139–150. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]