Abstract

Sm core proteins play an essential role in the formation of small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles (snRNPs) by binding to small nuclear RNAs and participating in a network of protein interactions. The two-hybrid system was used to identify SmE interacting proteins and to test for interactions between all pairwise combinations of yeast Sm proteins. We observed interactions between SmB and SmD3, SmE and SmF, and SmE and SmG. For these interactions, a direct biochemical assay confirmed the validity of the results obtained in vivo. To map the protein-protein interaction surface of Sm proteins, we generated a library of SmE mutants and investigated their ability to interact with SmF and/or SmG proteins in the two-hybrid system. Several classes of mutants were observed: some mutants are unable to interact with either SmF or SmG proteins, some interact with SmG but not with SmF, while others interact moderately with SmF but not with SmG. Our mutational analysis of yeast SmE protein shows that conserved hydrophobic residues are essential for interactions with SmF and SmG as well as for viability. Surprisingly, we observed that other evolutionarily conserved positions are tolerant to mutations, with substitutions affecting binding to SmF and SmG only mildly and conferring a wild-type growth phenotype.

Five evolutionarily conserved small nuclear RNAs (U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6 snRNAs) packaged in small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles (snRNPs) are essential components of the eukaryotic splicing machinery (31). The protein components of the snRNPs are divided into two classes, the specific proteins associated with one particular U snRNP and the common (or core) proteins shared by the U1, U2, U4, and U5 snRNPs. In humans, this last group is composed of eight proteins (B, B′, D1, D2, D3, E, F, G), also called Sm proteins, which bind to a highly conserved structural motif called the Sm site (28). The demonstration that yeast snRNPs are immunoprecipitated by anti-Sm antibodies and the observation that yeast snRNAs are able to assemble with the Xenopus Sm proteins upon microinjection into oocytes suggest that yeast snRNPs contain a set of proteins homologous to the metazoan Sm proteins (38, 51, 53). Biochemical studies with yeast indicated that the different yeast snRNPs contain polypeptides with sizes similar to those of the human core proteins (9). Some of these proteins (SmD1, SmD3, and SmE) were identified in the yeast genome sequence by homology to their human counterparts (3, 39, 41, 47). Independently, a conserved Sm motif was identified in the known Sm proteins (5, 18, 47). Scanning the yeast genomic database revealed the presence of several putative Sm proteins, some of which turned out to represent canonical snRNP core proteins (47, 48). Additional proteins from plants, animals, and fungi harboring the Sm motif were called Sm-like proteins (47). Some of them were shown to be components of the yeast U6 snRNP (5, 47). While the present work was in progress, the sequencing of the protein components from the yeast U1 snRNP was published (34). This confirmed the identity of some of the previously characterized Sm proteins, even though in this study, surprisingly, no SmB homolog was found in the U1 snRNP (or U2 snRNP) particles.

The Sm motif consists of two blocks of conserved amino acids separated by a nonconserved region. Of the 70 residues encompassing the Sm domain, only asparagine at position 55 is invariable. At many positions, the physicochemical property of the amino acid, not the primary sequence, is conserved (47). The Sm motif appears to be an important element for Sm protein function. Indeed, truncation of the Sm motif in either the SmB′ or the SmD3 protein abolishes SmB′-SmD3 complex formation (18). This result was probably predictable because for most proteins of the family, the Sm domain covers almost all the polypeptide chain.

Assembly of the polymerase II-transcribed U1, U2, U4, and U5 snRNPs is a multistep process following an ordered pathway in higher eukaryotes (12, 20, 30, 36, 37). These snRNAs are transcribed and exported to the cytoplasm. Sm proteins, which are stored in the cytoplasm (29, 44), then assemble on the snRNA Sm site. This binding allows hypermethylation of the snRNA 7-methyl cap by a methylase to form a methyl-2,2,7-guanosine cap structure (29). The assembled snRNP now possesses a bipartite nuclear localization signal composed of the Sm proteins and the cap structure. This signal will permit the transport of the snRNP to the nucleus. Addition of snRNP-specific proteins to the core snRNP, in the cytoplasm and/or the nucleus, completes the assembly of functional snRNP (22, 33, 35). The importance of studying snRNP biogenesis is emphasized by two recent reports showing that defects in this process may be the cause of a genetic disease, spinal muscular atrophy (13, 27).

The stoichiometry of different Sm proteins in Sm core particles has not been precisely determined. Available data suggest that each canonical Sm protein is present as a single copy in every snRNP although the existence of a dimer of an E-F-G subcomplex has been reported (37). Assembly of the Sm core will therefore require many different heterologous protein-protein interactions as well as protein-RNA interactions. The presence of a conserved sequence motif in Sm proteins suggests that they will have similar secondary and tertiary structures (47). It is therefore likely that the Sm core particle forms a pseudoregular structure where distinct but related interactions will take place between different Sm protein pairs.

Most of the studies on snRNP biogenesis have been performed with metazoan systems. Recent studies on the yeast Sm proteins SmD1, SmD3, SmE, and SmG demonstrated that the four corresponding genes are essential for viability (3, 39, 41, 47). Moreover, depletion of the SmD1 and SmD3 proteins results in decreased levels of U1, U2, U4, and U5 snRNAs and in undermethylation of the U snRNA (39, 41). These results suggest that snRNP biogenesis in yeast and mammals may occur by very similar pathways. However, the extent of similarity at the various steps of snRNA biogenesis is unclear. To obtain further insight into the mechanisms of yeast snRNP biogenesis, we have analyzed interactions between all yeast Sm proteins by using the two-hybrid system. Our goal was initially to define new potential partners of yeast Sm core proteins, to identify interacting partners among the Sm core proteins, and to precisely map the residues involved in Sm-Sm protein interactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, media, and genetic methods.

Two-hybrid screening and assays were performed with the Y190 strain (7) obtained from S. Elledge. The strain, containing pAS2-SmE, was cotransformed with a yeast cDNA library (constructed by M. White, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory) inserted in the pGAD vector. Putative interacting clones were identified on selective plates containing 40 mM 3-aminotriazole and screened for β-galactosidase activity. Positive clones were recovered in bacteria and retransformed in yeast strain Y190. Clones activating the reporter on their own were eliminated. Clones interacting specifically in combination with SmE were partially sequenced, and genes in the yeast genome were identified by using the Blast program (1).

The YRB15 strain (a ura3-52 lys2-801 ade2-101 trp1-Δ63 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 sme1::HIS3 [pUN-SME1 (URA3 CEN)]) (3) and YRB21 strain (a ura3-52 lys2-801 ade2-101 trp1-Δ63 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 sme1::HIS3 [pGAL1::SME1U (URA3 CEN)]) were used for plasmid shuffling to determine SmE mutant phenotypes.

Yeast strains were propagated in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose and SD media by standard methods (10). Yeast transformations were performed by the lithium acetate method as described previously (19, 46).

Plasmids.

Plasmids were constructed by standard methods (43). The SmE protein (3) (accession no. X92449 and U55020) used in the two-hybrid system was cloned into the pACTII vector (7, 17) by PCR amplification of the Sm protein coding region by using 5′ and 3′ oligonucleotides containing BamHI (BAM5, 5′-GAAAAACAAGAGGATCCGAATGTCGAAC-3′) and EcoRI (ECO3, 5′-ACTTGCGAATTCTCTATTTCTCTCG-3′) restriction sites, respectively. The sequence of the coding region was verified after cloning. A BamHI-EcoRI fragment (blunt ended by Klenow treatment at the EcoRI site) was isolated from pACTII-SmE and cloned into the pAS2 vector (7, 17) digested with SalI, blunt ended by Klenow treatment, and cut with BamHI. The resulting plasmid was named pAS2-SmE.

The SmF and SmG protein coding sequences (47) (accession no. U25842 and P40204) were amplified by PCR with the following oligonucleotides: for SmF, EM191 (5′-ACAGGATCCTCATGAGCGAGAGCAGT-3′) and EM192 (5′-GGACTCGAGCACAGTCGTCTTAGT-3′); for SmG, EM193 (5′-CCAGGATCCCCATGGTTTCTACCCCTGAA-3′) and EM194 (5′-TATCTCGAGTTATATGGCATCTAGAGC-3′).

The amplified fragments were inserted between the BamHI and XhoI sites of the pACTII vector, giving plasmids pBS1104 (for SmF) and pBS1105 (for SmG). The inserts were sequenced to ensure the absence of unwanted mutations. These inserts were then transferred into the pAS2 vector, giving plasmids pBS1106 (SmF) and pBS1107 (SmG). The SmB, SmD1, SmD2, and SmD3 coding sequences (and intron in the case of SmD2) were identified by database searches (47, 48) (accession no. P40018, Q02260, U17245, and P43321, respectively) and amplified by PCR with the following oligonucleotides: for SmB, EB4 (5′-GTCCCATGGTAATGAGCAAAATACAGGTG-3′) and EB5 (5′-GTCGGATCCACTATATTAGACTACACTAC-3′); for SmD1, EB6 (5′-GTCCCATGGTTATGAAGTTGGTTAACTTT-3′) and EB7 (5′-GTCGGATCCAGTGAAGATGACAACGACA-3′); for SmD2, EB8 (5′-GTCCCATGGAAATGAAAATTATCTTAC-3′) and EB9 (5′-GTCGGATCCTTTTACTCAACAGGGGTTT-3′); and for SmD3, EB10 (5′-GTCCCATGGCAATGACTATGAATGGAA-3′) and EB11 (5′-GTCGGATCCATTATCACCTTCTCTTAG-3′).

The amplified fragments were inserted between the BamHI and EcoRV sites of the pRS403 vector (50), giving plasmids pBS1245 (SmB), pBS1249 (SmD1), pBS1258 (SmD2), and pBS1250 (SmD3). The inserts were sequenced to ensure the absence of unwanted mutations. NcoI-BamHI fragments from these plasmids were then transferred into the pACTII vector, giving plasmids pBS1280 (SmB), pBS1282 (SmD1), pBS1284 (SmD2), and pBS1286 (SmD3), and into the pAS2 vector, giving plasmids pBS1281 (SmB), pBS1283 (SmD1), pBS1285 (SmD2), and pBS1287 (SmD3).

Residues corresponding to the N- and C-terminal halves of the SmE coding sequence (residues 1 to 66 and 67 to 94, respectively) were amplified by PCR with the following oligonucleotides: for SmE-N, BAM5 (5′-GAAAAACAAGAGGATCCGAATGTCGAAC-3′) and EB12 (5′-GTGCTCGAGTCAATCGGCACTATTCACAGGAA-3′); for SmE-C, EB13 (5′-GTGTGGATCCATGGTAAAGAAGATGTGGA-3′) and EB14 (5′-GTGCTCGAGTATGCCCATGTATATACGT-3′).

The amplified fragments were inserted between the BamHI and XhoI sites of the pRS403 vector (50), giving plasmids pBS1246 (SmE-N) and pBS1247 (SmE-C). The inserts were sequenced to ensure the absence of unwanted mutations. BamHI-XhoI fragments from these plasmids were then transferred into the pACTII vector, giving plasmids pBS1288 (SmE-N) and pBS1290 (SmE-C), and into the pAS2 vector, giving plasmids pBS1289 (SmE-N) and pBS1291 (SmE-C).

The SmX5 protein coding sequence (47) (accession no. Z35787 and Y13134) was amplified from the yeast cDNA library constructed by M. White (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory) by PCR with 5′ and 3′ oligonucleotides containing EcoRI (5′-GCAGGAATTCGGCACGAGATACTTTCGAACAC-3′) and XhoI (5′-CCCCCTCGAGGTCGACGGTATCG-3′) restriction sites, respectively. An EcoRI-XhoI fragment was purified and cloned into EcoRI-XhoI-digested vector pGAD, yielding plasmid pGAD-SmX5.

To place the SME1 gene under the GAL1 promoter, a BamHI-EcoRI fragment containing the SmE wild-type coding region was isolated from pACTII-SmE and cloned into BamHI-EcoRI-digested vector pGAL1 (URA3 CEN) (32), yielding plasmid pGAL1::SME1U.

The wild-type and mutant SmE genes were isolated from pACTII containing vector and subcloned as a BamHI-EcoRI fragment into pUN-PrE containing the 5′ noncoding region of the SmE wild-type gene. This 5′ noncoding region was amplified by PCR with oligonucleotides CES5 (5′-GATCTGTCGACGAGTATTTTCATGCC-3′) and CEB3 (5′-CATTCGGATCCTCTTGTTTTTCGCTC-3′ containing SalI and BamHI restriction sites, respectively, and cloned as a SalI-BamHI fragment into plasmid pUN10 (TRP1 CEN) (8).

pGST-SmE containing the SmE coding sequence in frame with glutathione S-transferase (GST) was obtained by subcloning a XmaI-EcoRI fragment isolated from plasmid pACTII-SmE into the pGEX-2T vector (Pharmacia) previously cut with XmaI-EcoRI. pGST-Q22L containing the SmE-Q22L mutant was obtained by cloning a XmaI-EcoRI fragment isolated from the pACTII-Q22L plasmid into XmaI-EcoRI-cut pGEX-2T. To generate GST-SmB, plasmid pBS1245 containing SmB was cut with NcoI, blunt ended by Klenow enzyme, and cut with NotI. The SmB-containing fragment was purified and inserted into pGEX-4T3 previously cut with BamHI, blunt ended with Klenow enzyme, and cut with NotI.

XmaI-XhoI fragments obtained by digestion of the pACTII-SmF and pACTII-SmG vectors were placed under the T7 promoter by cloning the fragments into pBluescript M13−. pBS1250 containing the gene coding for SmD3 under the T7 promoter was used for in vitro transcription and translation of SmD3 protein gene.

Screening for SmE mutants.

To create a library of SmE point mutants, the SmE coding region was amplified by PCR using pACTII-SmE as the DNA source and the BAM5 and ECO3 oligonucleotides (see above). Extension was done under normal conditions to minimize the occurrence of multiple mutations in the same molecule. BamHI-EcoRI fragments were then gel purified on a 6% acrylamide gel and cloned into the pACTII vector. After amplification in Escherichia coli, the library was used to transform strain Y190 containing pAS2-SmF or pAS2-SmG. Transformants were selected on SC-Trp-Leu plates (SC is synthetic complete medium), replicaplated on nitrocellulose filters, and regrown on selective medium. The filters were then used for the assay of β-galactosidase activity. White, noninteracting SmE mutants were recovered, plasmid was extracted, and DNA was sequenced (see Results for further analyses).

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis of the SmE gene was performed by using the megaprimer strategy (15, 49) with appropriate primers. The following mutagenic oligonucleotides were synthesized for this study (5′-3′): D47A, CATGAACTCAGCAAATCCAA; M50A, ACAACATTAGCGAACTCATC; N51A, GATGACAACAGCCATGAACT; E59A, CACAGGAATTGCCACGGCTT; K83V, TTATCGCCTACCAACAGGAT; G84A, GATATTATCGGCTTTCAACA; N86A, CAATGTGATAGCATCGCCTT.

All mutants were verified by DNA sequencing. The mutant obtained with oligonucleotide E59A contained a second mutation leading to the change of residue N63 to an asparagine (D). This mutant was analyzed further and is referred to as E59A N63D.

Production of recombinant SmE protein, preparation of anti-SmE antibodies, and Western blot analysis.

pGEX-2T- and pGST-containing fusion proteins were transformed in E. coli and induced by the addition of 0.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). Recombinant GST and GST fusion proteins were purified by using glutathione-Sepharose beads (Sigma) essentially as described previously (52). Anti-SmE antiserum was prepared in rabbits by using E. coli-produced SmE protein purified by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) after thrombin cleavage of the GST-SmE fusion protein.

To analyze the stability of GAL4 activation domain (GAD)-SmE mutant fusion proteins, protein extracts were prepared from cells (amount corresponding to an optical density of 5) by disruption with glass beads in lysis buffer (10% trichloroacetic acid, 10 mM Tris [pH 8], 25 mM NH4 acetate, 1 mM EDTA). The protein precipitates were resuspended in 300 μl of trichloroacetic acid-Laemmli loading buffer (15% glycerol, 60 mM Tris base, 3.4% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, 120 mM dithiothreitol) and heated for 10 min at 100°C. After centrifugation, 20 μl was loaded onto denaturing SDS-polyacrylamide gels (24). After transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane by electroblotting, the immunoblots were probed with anti-SmE antibodies and then incubated with goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibodies conjugated to peroxidase (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.). The blots were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vitro binding assays.

In vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase and translation of Sm protein genes by using rabbit reticulocyte lysate was done as described in the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega-Biotech) in the presence of [35S]methionine. For in vitro protein-protein interaction studies, 1 μg of purified GST fusion proteins or GST alone as a negative control was incubated with 10 μl of glutathione agarose and 20 μl of in vitro-translated [35S]methionine-labeled Sm protein in 200 μl of binding buffer (50 mM Tris HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 100 μg of bovine serum albumin/ml). After 20 min of incubation at 25°C followed by 20 min of incubation at 4°C with constant rotation, the beads were pelleted and washed five times with 1 ml of binding buffer. Bound proteins were fractionated on a Tricine–13% polyacrylamide gel (45). The gel was then dried and analyzed by fluorography.

Northern blots.

Total yeast RNA was prepared by using the guanidinium thiocyanate method (54). Electrophoresis, transfer, and hybridization conditions were performed as described previously (2).

β-Galactosidase assays.

Assays of β-galactosidase activity on plates were done as described previously (4). For quantitative analyses in liquid, strains carrying the two-hybrid plasmids were grown to mid-log phase at 26°C in SC-Trp-Leu medium to an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0 to 1.5. Cells were then prepared and β-galactosidase activity was measured by using ONPG (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) as described previously (21, 23). Results obtained independently in our collaborating laboratories were consistent even though some slight variations in values of β-galactosidase activity were observed (e.g., compare Tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 1.

Analysis of SmE interactions in the two-hybrid systema

| Fusion protein

|

Filter colorb | β-Galactosidase activity (U)c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gal4DBD | Gal4AD | ||

| SmE | SmF | ++ | 12 ± 1.5 |

| SmF | SmE | ++ | 11.4 ± 1.5 |

| SmE | SmG | ++ | 22 ± 1.5 |

| SmG | SmE | ++ | 15 ± 1.4 |

| SmE | SmX4 | + | 0.4 ± 0.05 |

| SmX4 | SmE | + | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| SmE | SmX5 | ± | 0.55 ± 0.1 |

| SmF | SmX4 | − | 0.069 ± 0.01 |

| SmX4 | SmF | − | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

| SmG | SmX4 | − | 0.014 ± 0.01 |

| SmX4 | SmG | − | 0.021 ± 0.02 |

| pAS2 | SmE | − | 0.0033 ± 0.001 |

| SmE | pACTII | − | 0.004 ± 0.001 |

| SNF1 | SNF4 | ++ | 0.33 ± 0.1 |

Interaction strength was determined both on filters and in liquid. Gal4DBD, Gal4p DNA binding domain; Gal4AD, Gal4 activation domain.

Intensity of the blue color on filters was assessed on a qualitative scale from − (white) to ++ (strong).

β-Galactosidase activities correspond to averages of two independent transformants assayed in duplicate. Values are means ± standard errors.

TABLE 2.

Two-hybrid assay of interaction between the Sm proteins and fragments thereof

| Protein, fragment, or vector | β-Galactosidase activity

(U)a of fusion with:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pAS2 | SmB | SmD1 | SmD2 | SmD3 | SmE | SmG | SmE-N | SmE-C | |

| pACTII | 0.058 ± 0.008 | 0.019 ± 0.001 | 0.019 ± 0.001 | 0.020 ± 0.001 | 0.013 ± 0.001 | 0.014 ± 0.002 | 0.019 ± 0.003 | 0.013 ± 0.001 | 0.045 ± 0.027 |

| SmB | 0.033 ± 0.007 | 0.022 ± 0.002 | 0.015 ± 0.004 | 0.018 ± 0.001 | 15 ± 1.4 | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 0.026 ± 0.005 | NTb | NT |

| SmD1 | 0.087 ± 0.026 | 0.036 ± 0.001 | 0.019 ± 0.0014 | 0.040 ± 0.014 | 0.014 ± 0.003 | 0.021 ± 0.004 | 0.013 ± 0.001 | NT | NT |

| SmD2 | 0.059 ± 0.018 | 0.028 ± 0.002 | 0.023 ± 0.001 | 0.030 ± 0.006 | 0.014 ± 0.002 | 0.015 ± 0.001 | 0.020 ± 0.004 | NT | NT |

| SmD3 | 0.055 ± 0.001 | 2.5 ± 0.84 | 0.022 ± 0.001 | 0.045 ± 0.009 | 0.019 ± 0.001 | 0.029 ± 0.006 | 0.031 ± 0.008 | NT | NT |

| SmE | 0.025 ± 0.004 | 0.022 ± 0.004 | 0.017 ± 0.003 | 0.020 ± 0.005 | 0.021 ± 0.001 | 0.99 ± 0.032 | 34 ± 2.4 | 0.018 ± 0.004 | 0.014 ± 0.001 |

| SmF | 0.025 ± 0.004 | 0.047 ± 0.006 | 0.041 ± 0.016 | 0.017 ± 0.003 | 0.024 ± 0.001 | 14 ± 1.2 | 0.031 ± 0.004 | 0.020 ± 0.001 | 0.019 ± 0.002 |

| SmG | 0.022 ± 0.004 | 0.020 ± 0.006 | 0.020 ± 0.001 | 0.028 ± 0.010 | 0.019 ± 0.001 | 19 ± 5.7 | 0.042 ± 0.016 | 0.010 ± 0.001 | 0.016 ± 0.007 |

| SmE-N | 0.039 ± 0.004 | NT | NT | NT | NT | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 0.018 ± 0.002 | 0.018 ± 0.004 | 0.039 ± 0.018 |

| SmE-C | 0.044 ± 0.010 | NT | NT | NT | NT | 0.019 ± 0.001 | 0.013 ± 0.001 | 0.014 ± 0.002 | 0.0090 ± 0.002 |

β-Galactosidase activities generated by combinations of various Sm proteins, fragments thereof, and control vectors in a two-hybrid assay are given. The values represent the averages of three assays with different transformants ± standard errors (except for pAS2-SmE and pACTII-SmF combination, where only two transformants were analyzed). Activity values above 1 are in boldface type.

NT, not tested.

Immunoprecipitations and quantitation of cap hypermethylation.

Immunoprecipitations were performed as previously described (2). Quantitation was performed by scanning Northern autoradiography and by determining the intensities for each band by using MacBass software. The value, representing cap hypermethylation efficiency, was determined by the formula (PRNA/SRNA)t = 12/(PRNA/SRNA)t = 0 where PRNA and SRNA represent intensities of bands in the pellet and supernatant, respectively, 12 h after (t = 12) or before (t = 0) shift to glucose-containing medium.

RESULTS

Isolation of proteins interacting with SmE.

To characterize new factors implicated at various steps in snRNP biogenesis and function, we decided to use the two-hybrid assay to screen a library of yeast cDNA for sequences interacting with the yeast SmE protein (3). We constructed a plasmid harboring the SmE coding sequence fused to the Gal4p DNA binding domain (GBD) of the pAS2 backbone. We determined that a gene fusion encoding the Gal4p DNA binding domain and the yeast SmE protein complements the lethal disruption of the chromosomal copy of the SmE gene, suggesting that the fusion protein is stable and active and could therefore be used in a screen (data not shown). A strain containing the GBD-SmE fusion protein was transformed with a yeast cDNA library inserted in the pGAD vector. From 2 × 105 transformants, we isolated candidates which coded for fusion proteins that interacted specifically with SmE. We recovered cDNA clones encoding two other Sm core proteins, SmF and SmG. The GAD-SmF and GAD-SmG fusions isolated from the cDNA library start, respectively, 50 and 7 nucleotides upstream of the ATG codon of the corresponding open reading frames. In addition, we recovered a clone encoding the Sm-like protein SmX4, which is a U6-associated protein (47). The GAD-SmX4 fusion isolated starts 32 nucleotides upstream of the ATG codon of the SmX4 coding sequence. All GAD-Sm fusions contained complete coding sequences, with additional amino acids encoded by the 5′ nontranslated region at the N terminus—2 amino acids for SmG, 16 for SmF, and 10 for SmX4. As a first test to verify that the selected proteins interact, we inverted the orientation of the two-hybrid assay. The SmE protein was fused to the GAD (in the pACTII vector), while the coding sequences for the SmF, SmG, and SmX4 proteins were cloned into the pAS2 vector (see Materials and Methods). Interactions between SmE, SmF, SmG, and SmX4 were quantified by measuring β-galactosidase activities for the different combinations. As shown in Table 1, the interactions between SmE and SmF and between SmE and SmG are relatively strong (10 to 20 U) in comparison to that of other known interacting proteins, SNF1 and SNF4 (0.33 U). In contrast, the interaction between SmE and SmX4 appears weak since we obtained only 0.4 to 0.5 U of β-galactosidase activity. This value is, however, higher than the value obtained for the SNF1-SNF4 control usually used to test interactions in the two-hybrid system (7). No interactions between SmX4 and SmF or SmG could be detected (Table 1). To verify the specificity of the interaction between SmX4 and SmE, we tested whether SmE also interacts with SmX5, another known Sm-like U6 protein. As shown in Table 1, SmX5 also interacts weakly (0.55 U) with SmE. This result suggests that the putative interaction between SmX4 and SmE may not be specific (see Discussion).

Matrix of protein-protein interactions.

The analysis described above demonstrated that Sm-Sm protein interactions can be identified with the two-hybrid assay. We therefore decided to extend this approach to include all Sm proteins. The remaining Sm protein coding sequences, identified by database searches (47, 48), were cloned by PCR from genomic DNA, and the sequences were verified to ensure that no mutation was present before these fragments were transferred to the pAS2 and pACTII vectors. All pairwise combinations of the resulting plasmids, including the control vectors without insert, were introduced into yeast cells. Three independent transformants were picked from each transformation and used to determine what level of β-galactosidase is produced under the control of a given combination of Sm proteins. The strain carrying the pAS2-SmF fusion grew very poorly and gave consistently variable results with some combinations of pACTII-derived plasmids, probably owing to the toxicity of this particular hybrid protein. It was therefore excluded from this analysis. Our results are summarized in Table 2. We observed an interaction between the yeast SmD3 and SmB proteins as well as interactions between the SmE and SmG proteins and the SmF and SmE proteins as already described above. SmE-SmG and SmB-SmD3 were tested in two orientations in this particular experiment, and they were positive in both assays. The other combinations of Sm proteins did not induce the production of significant β-galactosidase activity (see Discussion), demonstrating the specificity of the assay.

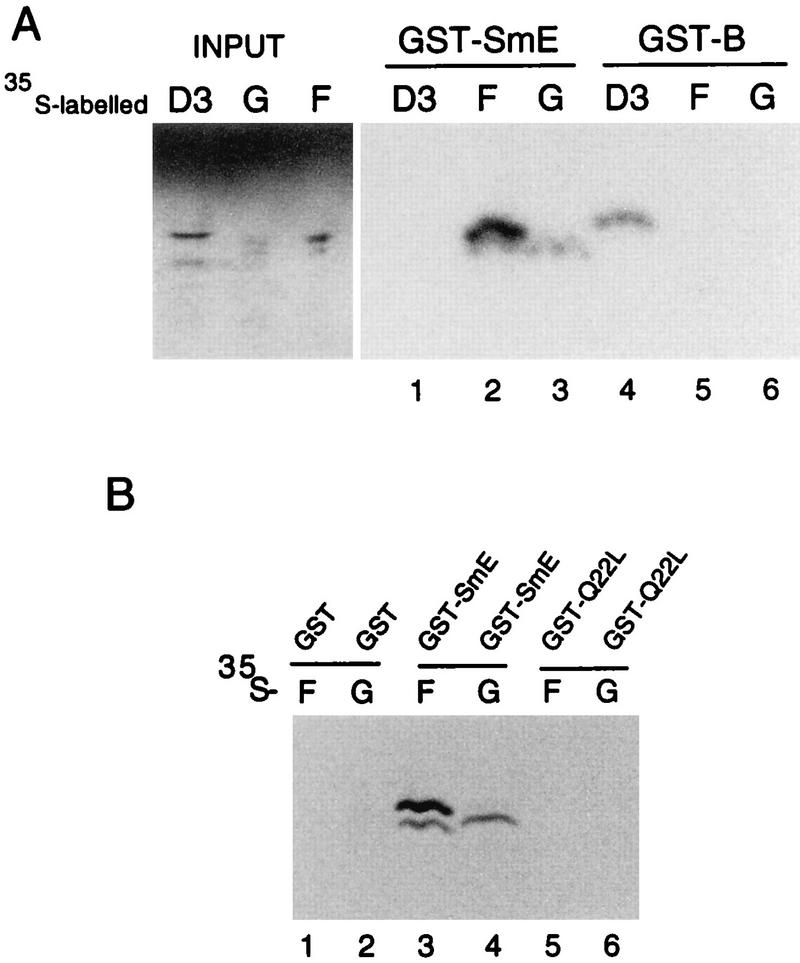

To prove that the observed interactions of SmE with SmF, SmE with SmG, and SmB with SmD3 are due to direct interactions rather than in vivo artifacts, we tested the ability of SmE and SmB fusion proteins to bind to their respective partners in vitro. The SmE and SmB coding sequences were fused to the C terminus of the carrier GST protein and expressed in bacteria. The purified recombinant proteins were incubated with [35S]methionine-labeled SmD3, SmF, and SmG proteins prepared by transcription and translation in vitro. This assay was performed with the proteins in the presence of bovine serum albumin to prevent nonspecific binding. Bound proteins recovered on glutathione agarose beads were analyzed by electrophoresis on polyacrylamide-Tricine gels. As shown in Fig. 1A, SmF and SmG interacted strongly with the GST-SmE fusion protein (lanes 2 and 3), whereas no labeled SmD3 bound to GST-SmE (lane 1). Moreover, SmD3 interacted with GST-SmB (lane 4) but neither SmF (lane 5) nor SmG (lane 6) bound to GST-SmB. No labeled SmF and SmG proteins (Fig. 1B, lanes 1 and 2) or SmD3 protein (data not shown) bound to GST alone. The specificity of this in vitro protein interaction assay is further shown by the behavior of SmE mutant Q22L (for a description of this mutant, which is unable to interact with SmF and SmG, see below). As shown in Fig. 1B, whereas GST-SmE interacts with both SmF (lane 3) and SmG (lane 4), the GST-Q22L mutant is unable to bind SmF and SmG (lanes 5 and 6).

FIG. 1.

In vitro binding of yeast Sm proteins. (A) [35S]methionine-labeled SmD3, SmF, and SmG prepared by in vitro transcription and translation were mixed with GST-SmE or GST-SmB produced in E. coli. Proteins bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads were washed, denatured, and separated on gels in Tricine buffer. Input represents aliquots of radioactive proteins corresponding to 25% of that used in each of the binding reactions. The predicted molecular sizes of the proteins are as follows: SmD3, 11.2 kDa; SmG, 8.4 kDa; SmF, 9.6 kDa. Additional bands observed in input lanes correspond to readthrough and premature translation termination products. Exposure times were identical for both panels. (B) [35S]methionine-labeled SmF and SmG were mixed with GST, GST-SmE, and SmE mutant Q22L fused to GST (GST-Q22L) produced in E. coli. Proteins bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads were treated as described for panel A.

Dissection of the SmE protein.

The results presented above demonstrate that the two-hybrid system is an assay of choice to study Sm-Sm protein interactions. We decided to analyze these interactions in detail. We chose to study the SmE protein because it interacts with both the SmF and the SmG proteins. We first tested whether the SmE protein could be divided into independent domains. The Sm motif is composed of two conserved regions separated by a variable number of residues with no sequence conservation and which are probably part of a loop (5, 18, 47). We decided to test whether the two conserved regions would be able to function independently in interaction with Sm proteins. The SmE protein was divided in the middle of the loop into N (residues 1 to 66)- and C (residues 67 to 94)-terminal fragments. These fragments (designated SmE-N and SmE-C, respectively) were cloned independently in the pAS2 and pACTII vectors and introduced in yeast in combination with constructs containing either SmE, SmF, SmG, or no insert. The β-galactosidase produced by these transformants was then assayed. Interestingly, we did not detect any interaction between the SmE-N and SmE-C fragments in this assay (Table 2), suggesting that the two halves of the Sm domain are not able to function independently.

Isolation of SmE interaction mutants.

The results presented above suggest that the Sm domain cannot be divided into smaller functional units. Nevertheless, only a limited number of residues can be involved in Sm-Sm protein contacts. We decided to find residues of the SmE protein which, when mutated, affect protein interaction. SmE was a good candidate for this study because it allowed us to look for mutants defective in interaction with SmF but still able to interact with SmG and vice-versa. We mutagenized the SmE coding region by PCR amplification under mild conditions (see Materials and Methods) to minimize the production of multiple mutants. The amplified DNA was subcloned as a BamHI-EcoRI fragment in pACTII vector to generate a library of GAD-SmE mutant fusion proteins. Y190 yeast strains carrying either pAS2-SmG or pAS2-SmF were transformed with this library. Transformants were replica plated onto nitrocellulose filters that were incubated on SC-Trp-Leu plates for one night before a β-galactosidase test was performed. On average, of the colonies obtained, approximately 15% were white on each tested filter. Plasmids were recovered from colonies displaying a white phenotype and sequenced. Plasmids carrying a mutation(s) leading to a single amino acid change were transformed back into Y190 strains carrying either pAS2-SmF or pAS2-SmG and reanalyzed for the corresponding β-galactosidase activities on plates. All single mutants and all multiple missense mutants obtained in this experiment were analyzed further. For each mutant, two transformants were used to quantify β-galactosidase activities. Sequencing a limited number (i.e., 60) of randomly selected clones from the library also allowed us to identify four additional SmE mutants carrying a single amino acid change. Finally, we used site-directed mutagenesis to substitute seven evolutionarily conserved residues which, with the exception of residue D47, were not found mutated by the two previous strategies (see above). These mutants were also analyzed in the two-hybrid system for interaction with the SmF and SmG proteins.

As shown in Table 3, the 26 SmE mutants analyzed were grouped into four classes based on their phenotypes. The first class includes eight mutants which are unable to interact with SmF or SmG protein. The second class contains two lethal SmE mutants interacting moderately with SmF but not with SmG. The third group is composed of three lethal mutants interacting with SmG but not SmF. The last group contains mutants with substitutions in positions which do not interfere or which interfere only moderately with SmE binding to SmF and SmG. A description of each class of the SmE mutants is given below.

TABLE 3.

Properties of amino acid substitution mutants of yeast SmE

| SmE mutanta | Method of iso- lationb | In vivo interaction

withc:

|

Viability as fusion proteind | Fusion protein stabilitye | Viability of WT promoterf | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SmF | SmG | |||||

| Class I | ||||||

| Q22L | i.v. | − | − | − | + | − |

| V27E | i.v. | − | − | − | − | − |

| I29K | i.v. | − | − | − | + | − |

| W30Stop | i.v. | − | − | − | − | NDg |

| G41D | i.v. | − | − | − | − | ND |

| G45Stop | i.v. | − | − | − | − | ND |

| I54N | i.v. | − | − | + | + | − |

| L82Stop | i.v. | − | − | − | + | − |

| Class II | ||||||

| L89Stop | i.v. | + | − | − | + | − |

| I90R | i.v. | + | − | − | + | − |

| Class III | ||||||

| D47A | s.d.m. | − | + | − | + | − |

| D47H | i.v. | − | + | − | ND | − |

| L81P | i.v. | − | ++ | − | + | − |

| Class IV | ||||||

| N3T | i.v. | ++ | ++ | + | ND | + |

| K6E | i.v. | ++ | ++ | + | ND | + |

| M10V | i.v. | ++ | ++ | + | ND | + |

| L31S | r.s. | ++ | ++ | + | ND | + |

| G45V | r.s. | ++ | ++ | − | + | TSh |

| M50A | s.d.m. | + | + | + | ND | + |

| N51A | s.d.m. | + | ++ | + | ND | + |

| E59A N63D | s.d.m. | ++ | ++ | + | ND | + |

| P76S | r.s. | ++ | ++ | + | ND | + |

| I80F | r.s. | + | ++ | + | ND | + |

| K83V | s.d.m. | ++ | ++ | + | ND | + |

| G84A | s.d.m. | + | ++ | + | ND | + |

| N86A | s.d.m. | ++ | + | + | ND | + |

The designation for each mutant indicates the wild-type amino acid and its position, followed by the mutated amino acid that was introduced in place of the wild-type amino acid. In one case, two amino acids were substituted in the same mutant.

The mutants were obtained by in vivo selection (i.v.), random sequencing (r.s.), or site-directed mutagenesis (s.d.m.).

Interaction with pAS2-SmF or pAS2-SmG is scored as equal to that of wild type (++; >60%), moderate (+; 20 to 60%), or none (−; <20%).

Plasmids containing the mutant fusion proteins were transformed in an sme1::HIS3 strain carrying a wild-type SME1 gene on a pUN60-URA3 plasmid. The viability of mutants was determined by streaking cells on 5-FOA-containing plates.

Equal amounts of extracts prepared from cells carrying the GAD-SmE mutant fusion proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-SmE antibodies (see Fig. 3).

Plasmids containing the SmE mutants under wild-type (WT) flanking regions (pUN-PrE) were transformed in ansme1::HIS3 strain carrying a wild-type SME1 gene on a pUN60-URA3 plasmid. Viability of mutants was determined by streaking cells on 5-FOA-containing plates.

ND, not determined.

TS, temperature sensitive.

(i) SmE mutants unable to interact with SmF and SmG (class I).

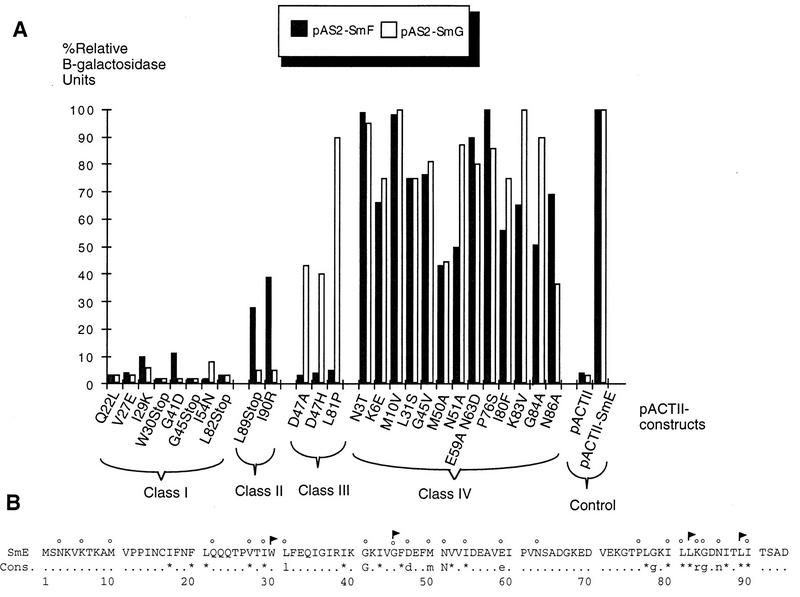

Eight SmE mutants were unable to interact with SmF and SmG both by the plate assay (Table 3) and by quantitative measurement of β-galactosidase (Fig. 2). Of these, three mutants are nonsense mutants (W30Stop, G45Stop, and L82Stop) while the others harbor single amino acid substitutions. The mutation in one mutant, Q22L, affects a residue that is not conserved in the Sm protein family, while four other mutants have substitutions in evolutionarily conserved positions: the mutations in mutants V27E, I29K, and I54N change hydrophobic residues into negatively charged, positively charged, and polar amino acids, respectively, while the mutation in mutant G41D changes the highly conserved uncharged glycine at position 41 into a negatively charged aspartic acid. As mentioned above, the GST-Q22L mutant fusion protein is unable to bind SmF and SmG in vitro (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 2.

Protein-protein interactions of mutant SmE fusion proteins. (A) β-Galactosidase activities shown correspond to averages of two independent transformants assayed in duplicate and are presented relative to those of the wild-type pACTII-SmE interactions with pAS2-SmF and pAS2-SmG. (B) The amino acid sequence of SmE protein is given. Cons., consensus inferred from Sm and Sm-like protein sequences (47). The positions of the point mutants are indicated above the sequence by small circles. Stop mutants are represented by flags.

(ii) SmE mutants interacting with SmF but not with SmG (class II).

We recovered a single point mutant (I90R) of the SmE protein that still interacted with SmF but that had lost the ability to interact with SmG (Table 3). This mutant harbors a substitution at a conserved hydrophobic position that replaces a nonpolar isoleucine with a positively charged arginine near the C terminus of the SmE protein. This mutant reduces β-galactosidase production to background levels when in combination with pAS2-SmG, while in the presence of pAS2-SmF it reduces β-galactosidase levels only to 40% of the value obtained with the wild-type protein (Fig. 2). A multiple mutant producing a similar phenotype resulted from the presence of a stop codon at residue 89, producing a deletion of the last 5 amino acids (Table 3). Quantitative β-galactosidase assays indicate that this mutant retains some ability to interact with SmF (30% of the wild-type β-galactosidase level) but is totally unable to interact with SmG (Fig. 2).

(iii) SmE mutants interacting specifically with SmG but not with SmF (class III).

Two SmE mutants with mutations in conserved residues at positions D47 and L81 were recovered from our genetic screen as specifically interacting with SmG (Table 3). Mutant D47H carries a change of aspartic acid at position 47 to a positively charged histidine, whereas mutant L81P possesses a nonpolar proline in place of leucine at position 81. We also characterized the D47A mutant created by site-directed mutagenesis. Both D47H and D47A SmE mutants have identical phenotypes when tested for interaction properties and viability (Table 3). Quantitation of β-galactosidase activities indicates that mutant L81P retains almost a wild-type interaction capacity for SmG whereas mutants D47H and D47A reduce β-galactosidase levels in the presence of pAS2-SmG to 40% of the value obtained with the wild-type protein (Fig. 2). In all three cases, no interaction above background could be observed with SmF (Fig. 2).

(iv) SmE mutants unaffected in SmF and SmG binding (class IV).

Class IV is the largest group, with 13 mutants: 6 mutants were obtained by site-directed mutagenesis of residues at conserved positions in SmE, 4 mutants were isolated by random sequencing, and 3 mutants, which were selected by the in vivo screen, were actually not affected in their interaction properties after retransformation into pAS2-SmF- and pAS2-SmG-containing strains. As shown in Table 3, mutants with mutations in residues that are poorly conserved in the Sm protein family, such as M3T, KE6, M10V, G45V, and P76S, are still able to interact with both SmF and SmG. Interestingly, mutants with mutations in residues that are evolutionarily conserved, such as L31S, M50A, N51A, I80F, G84A, and N86A as well as the double mutant E59A-N63D, are able to bind to their partners. This is also the case for mutant K83V, which has a mutation at the SmE specific position 83. We noticed nevertheless that the levels of β-galactosidase produced in the presence of pAS2-SmF were somewhat lower for most of these mutants than for the wild type (Fig. 2).

Growth phenotypes of SmE mutants.

We next tested the ability of the mutated GAD-SmE fusion proteins to complement yeast strain YRB15 disrupted at the SME1 locus and carrying a wild-type copy of the SME1 gene on a URA3-marked plasmid (3). After transformation with SmE mutant fusion protein constructs, cells were grown on plates containing 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) to select against the URA3-marked plasmid. As shown in Table 3, all mutant fusion proteins in classes I, II, and III, with the exception of I54N, are unable to support growth. Of the class IV mutants, which are able to interact with SmF and SmG, all complement the SME1 disruption, with the single exception of the G45V substitution mutant. Interestingly, the mutant G45V is lethal as a GAD fusion protein, although it is able to interact with both SmF and SmG (Fig. 2).

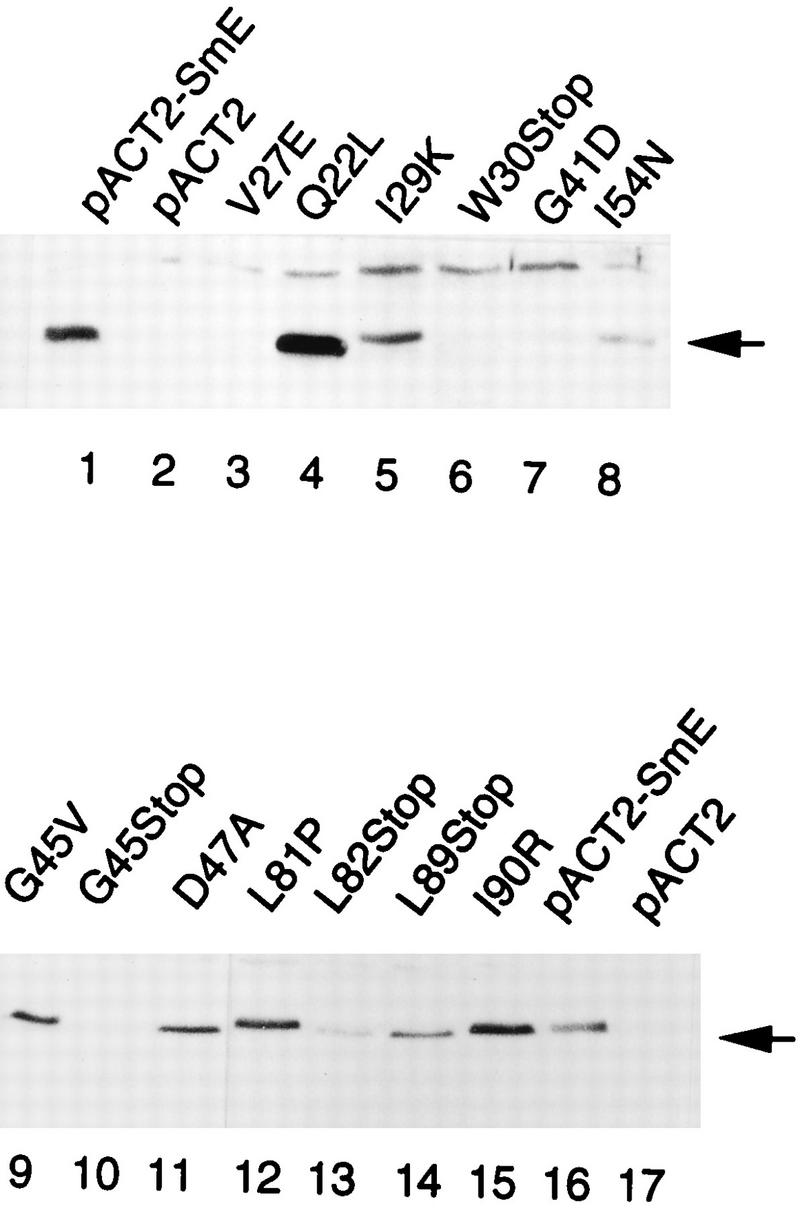

The recessive lethal phenotype observed with almost all mutants of classes I to III could be due to a lack of interaction with Sm proteins. However, at least in the case of the class I mutants, the lack of interaction with the SmF and SmG proteins might be a secondary phenotype resulting from the instability of the mutated SmE protein (or its mRNA). To test this possibility, we assessed expression levels of the GAD-SmE mutant proteins by Western blot analyses with anti-SmE antibodies. These antibodies, whose preparation will be described elsewhere, recognize wild-type SmE (data not shown) and the GAD-SmE fusion protein (Fig. 3, lane 1), whereas no band is visible in extracts obtained from cells carrying only the pACTII vector (GAD) (Fig. 3, lane 2). The Western blot analysis of the mutant SmE proteins is depicted in Fig. 3 and summarized in Table 3. The GAD-SmE mutant fusion proteins Q22L, I29K, I54N, and L82Stop (class I), I90R and L89Stop (class II), D47A and L81P (class III), and G45V (class IV) are expressed to detectable levels (similar to that of the wild-type fusion protein or a few-fold lower) (Fig. 3 and Table 3). This suggests that the phenotypes observed (lack of interaction with SmF and/or SmG and inability to complement an SME1 gene disruption) are due to functional defects and not stability problems. In contrast, we detected only a very low level of protein or no protein at all for the class I GAD-SmE mutant fusion proteins V27E, W30Stop, G41D, and G45Stop (Fig. 3; Table 3). This suggests that these proteins are unstable, even though we cannot formally rule out (particularly for the W30Stop and G45Stop mutants) that mutations prevent recognition of the proteins by our polyclonal serum. Interestingly, for the mutants tested, the results of the Western blot analysis are entirely compatible with the results of the two-hybrid assay. Indeed, class II to IV mutants that interact at least with another Sm protein express stable SmE fusion proteins. As expected, all mutants from classes II to IV are expressed stably whereas class I mutants are heterogeneous, with some mutations leading to protein instability and hence to a lack of protein interaction and others resulting in stable but nonfunctional proteins.

FIG. 3.

Western analysis of mutant GAD-SmE fusion proteins. Similar amounts of cell extracts from Y190 transformants carrying the indicated mutated SmE fusion proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-SmE antibodies. Control extracts were made from cells carrying the wild-type SmE fusion protein pACTII-SmE (lanes 1 and 16) or pACTII vector alone (lanes 2 and 17).

Although cells carrying the wild-type GAD-SmE fusion protein have no obvious growth defects (3), we were concerned that the growth phenotypes observed for the mutant GAD-SmE fusion proteins expressed from the pACTII vector may differ from phenotypes of mutant proteins with the same mutation if expressed as an SmE protein (i.e., nonfused) from its own promoter. Indeed, the pACTII vector contains a 2 μm origin of replication and a strong promoter driving a high level of expression. In addition, the GAD fusion protein contains a nuclear localization signal that will target the fusion proteins to the nucleus (7). To determine the phenotypes of the SmE mutant genes, the mutated genes flanked by wild-type chromosomal regions (Materials and Methods) were inserted in a TRP1 centromeric plasmid. These constructs were transformed into strain YRB15 containing the wild-type gene on a URA3 plasmid. Transformants were streaked on 5-FOA plates, and the phenotypes of the resulting strains were analyzed. As shown in Table 3, the phenotypes observed for SmE mutants placed under the control of their natural promoter are identical to those observed for the mutated fusion proteins, with two exceptions, those for mutants I54N and G45V. The mutated fusion protein GAD-I54N supports growth, while this is not the case when it is expressed in its chromosomal context. Conversely, for mutant G45V, the fusion protein is unable to support growth whereas the corresponding mutated gene in its wild-type chromosomal context confers a temperature-sensitive phenotype (Table 3).

Characterization of SmE mutant defects.

The lethality of the SmE mutants producing normal protein levels may be a consequence of defects in snRNP stability and/or formation. Alternatively, the mutated protein might allow snRNP biogenesis but prevent snRNP function in the spliceosome or intranuclear snRNP localization. To distinguish these possibilities, we analyzed the snRNA levels in strains expressing the mutated alleles.

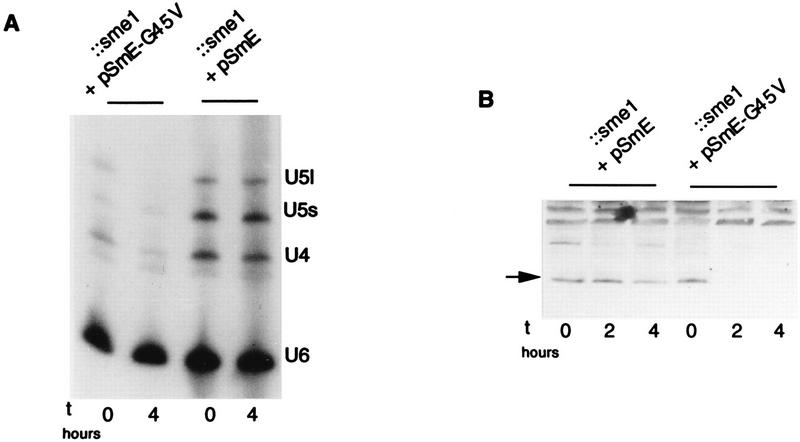

Of all the mutants, the analysis of the G45V mutant was the easiest because its mutation involves a conditional allele. A strain containing the SmE-G45V mutant allele on a centromeric plasmid as the sole source of SmE protein was grown at 25°C and then shifted for 4 h to the restrictive temperature of 37°C. RNA was extracted, and a Northern blot analysis with probes directed against the U4, U5, and U6 snRNAs was performed. As shown in Fig. 4A, the amounts of U4 and U5 snRNAs decrease in the mutated strain after shift to the restrictive temperature whereas U6 snRNA quantities remain stable. This result is identical to that observed for an SmE depletion (3) and can be explained if the G45V protein becomes unstable or nonfunctional upon shift to 37°C. To discriminate between these possibilities, we performed Western analysis on protein extracts made after shift to 37°C by using anti-SmE antibodies to monitor the behavior of the mutated protein. As shown in Fig. 4B, shift of the G45V mutant to the restrictive temperature for 2 and 4 h led to a decrease in the G45V protein level whereas wild-type SmE protein remained stable. Thus, the mutation in mutant G45V confers a conditional instability to the protein.

FIG. 4.

Defects of SmE mutant G45V. (A) Amounts of spliceosomal snRNAs are decreased after shift of SmE mutant G45V to the restrictive temperature. Northern analysis was performed on RNA isolated from strains carrying wild-type (pSmE) or mutant G45V (pSmE-G45V) SmE genes before and 4 h after shift to 37°C. Probes were oligonucleotides complementary to U4, U5, and U6 snRNAs. The US snRNA is represented by two bands corresponding to a long (U5l) and a short (U5S) form. (B) Stability of SmE mutant G45V protein is affected at the restrictive temperature. Strains carrying wild-type (pSmE) or mutant G45V (pSmE-G45V) genes under the natural promoter as the sole source of SmE protein were grown and shifted for the indicated times at 37°C. Similar amounts of cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE in Tricine buffer and immunoblotted with anti-SmE antibodies.

Other interesting SmE mutants (for example, Q22L, V27E, I29K, I54N, I90R, D47A, and L81P) are lethal. To analyze the biochemical consequences of the corresponding mutations, strain YRB21 containing a disruption of the SME1 gene complemented by the wild-type SmE gene under the galactose promoter was transformed with SmE mutant genes under the wild-type promoter carried on the centromeric pUN-PrE plasmid. The resulting strains grow on medium containing galactose because the wild-type SME1 gene is expressed. When the strains are shifted to medium containing glucose, the wild-type gene is repressed, allowing examination of the mutant phenotype. As expected, tested transformants carrying mutants Q22L, V27E, I29K, I54N, L82Stop, L89Stop, I90R, D47A, and L81P die after transfer to repressive medium (glucose), confirming the lethal phenotypes observed on 5-FOA plates.

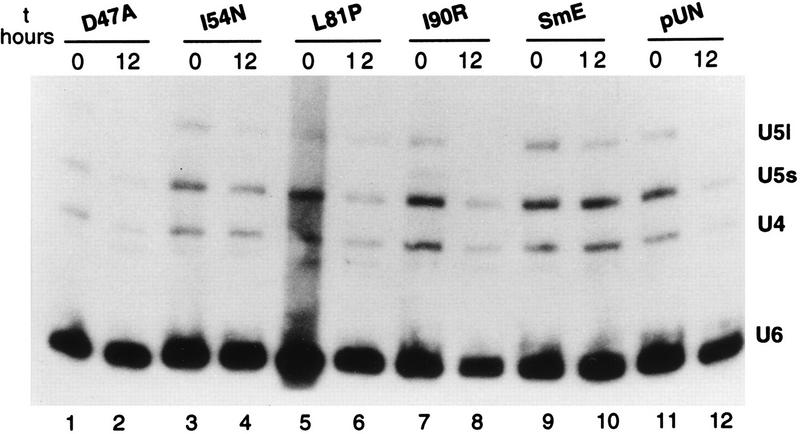

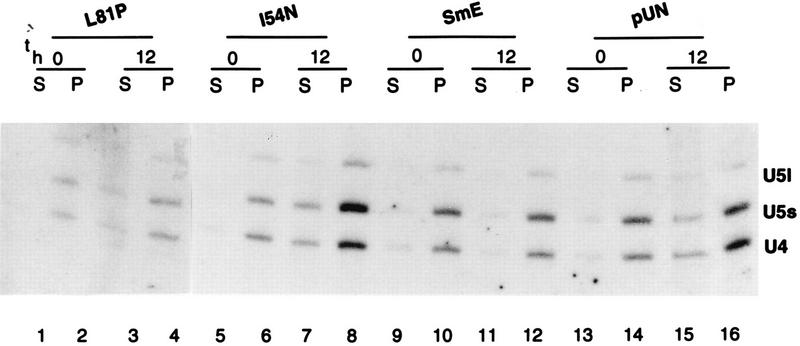

To examine the effect of the SmE mutant proteins on spliceosomal snRNAs, we performed Northern analysis with RNA isolated from cells grown in the presence of galactose and cells shifted to glucose-containing medium for 12 h. As shown in Fig. 5, whereas the U6 snRNA level remained constant upon GAL1::SME1 repression, the abundance of U4 and U5 snRNAs decreased in cells containing the pUN10 vector alone (compare lanes 11 and 12) and remained approximately constant in cells containing vector with a wild-type SmE gene (compare lanes 9 and 10). The level of spliceosomal snRNAs also decreases in mutant D47A (compare lanes 1 and 2) as well as in nonsense stop mutants L82Stop and L89Stop (data not shown). In contrast, a moderate effect on snRNA levels is observed for mutants I54N (compare lanes 3 and 4), L81P (lanes 5 and 6), and I90R (lanes 7 and 8), which possess more U5 and U4 snRNAs after a 12-h shift to glucose-containing medium than the negative control does (lane 12). These results suggest that the majority of SmE mutants are prevented from correct assembly of snRNPs although mutants I54N, L81P, and I90R are probably able to associate with snRNAs and form stable snRNPs. The slight decrease in snRNA levels observed for these two mutants may be a consequence of cell death occurring 12-h after shift to glucose-containing medium.

FIG. 5.

snRNA stability in SmE mutants. RNA was extracted from endogenous sme1-disrupted strains bearing theGAL1::SME1 allele and either the indicated mutant SmE genes under the natural promoter (plasmid pUN-PrE) (lanes 1 to 8), the wild-type SmE gene (lanes 9 and 10), or vector pUN alone (lanes 11 and 12) before and 12 h after shift to glucose (GAL1-repressing conditions). RNA was separated on a 6% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gel, subjected to Northern analysis, and hybridized with probes specific for the yeast U4, U5, and U6 snRNAs. The poor transfer of the U1 and U2 snRNAs precluded their analyses in this experiment.

Cap hypermethylation in SmE mutants.

In higher eukaryotes, it has been shown that the core complex is necessary for cytoplasmic cap trimethylation and nuclear localization of snRNPs (11, 29, 36). Since our previous results suggest that the I54N, L81P, and I90R mutants are able (at least in part) to assemble into snRNPs, the defect of these mutants may be explained by a deficiency in cap hypermethylation. To test this hypothesis, total RNA extracted from cells carrying a given SmE mutant gene before and after depletion of wild-type SmE protein was immunoprecipitated with antitrimethylguanosine (TMG) antibody and subjected to Northern analysis. As shown in Fig. 6, in a wild-type strain, essentially all the snRNAs are recovered in the pellet independently of the growth medium (containing galactose [lane 10] or glucose for 12 h [lane 12]) whereas very few snRNAs remain in the supernatant (lanes 9 and 11). Quantitation of the results shown in Fig. 6 is given in Table 4. For the wild type, the hypermethylation efficiency, which represents the relative proportion of snRNAs present in the pellet versus that in the supernatant after (t = 12) and before (t = 0) shift to glucose, is 0.97 to 1.17, indicating no effect on hypermethylation. In contrast, Fig. 6 shows that after depletion of the SmEp (cells carrying the pUN10 vector alone), some snRNAs remain in the supernatant 12 h after shift to glucose (lane 15). As shown in Table 4 (row 2), the efficiency of hypermethylation is around 0.51 to 0.61, indicating that depletion of SmE protein affects the snRNA hypermethylation process. Similar results have been obtained following depletion of the yeast SmD1 and SmD3 core proteins (39, 41). Concerning the SmE mutants and as shown in Fig. 6 and Table 4, analysis of the relative proportions of U5 and U4 snRNAs present after and before depletion of wild-type SmE protein in L81P and I54N SmE mutants reveals that hypermethylation is affected in the L81P mutant (efficiency of 0.49 to 0.53) but not in the I54N mutant strain (efficiency of 0.89 to 1.05). These results suggest that hypomethylation of snRNAs may be the defective step in SnRNP assembly in SmE mutant L81P but not in mutant I54N.

FIG. 6.

Decreased 5′ cap hypermethylation of spliceosomal U snRNAs in SmE mutant L81P. RNA blot analysis after immunoprecipitation with anti-TMG antibody. Endogenoussme1-disrupted strains containing theGAL1::SME1 allele and plasmids carrying the wild-type SmE gene, the mutant L81P and I54N genes, or the vector pUN alone were shifted to glucose-containing medium for 0 and 12 h. RNA was extracted and immunoprecipitated with anti-TMG antibodies. Supernatants (S) and pellets (P) were subjected to Northern analysis using U4 and U5 as probes. For mutants I54N and L81P, the amounts of snRNA were increased twofold to compensate for the observed slight decrease in U snRNAs 12 h after shift to glucose (see Fig. 5). Quantitation of the results is presented in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Relative proportion of hypermethylated snRNAs

| snRNA | Relative

proportiona in:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SmE | pUN | I54N | L81P | |

| U5l | 0.97 | 0.61 | 0.89 | 0.53 |

| U5s | 1.17 | 0.51 | 1.05 | 0.50 |

| U4 | 1.05 | 0.58 | 0.89 | 0.49 |

The relative proportions of hypermethylated snRNAs represent the fractions of RNA (Fig. 6) present in the pellet versus those in the supernatant after and before shift to glucose-containing medium.

DISCUSSION

We have utilized the two-hybrid technique to examine protein-protein interactions between yeast Sm proteins. Our results can be summarized as follows. First, we identified SmE interacting partners in a two-hybrid screen. Second, we analyzed the interaction between Sm core proteins, giving us information about the protein-protein contacts occurring inside the Sm complex. Finally, we selected mutants of the SmE protein unable to interact with SmF and/or SmG and completed this analysis by mutating conserved positions in the SmE protein. This allowed us to identify residues of the SmE protein involved in various functions and protein-protein interactions.

SmE interacting partners.

We have isolated potential binding partners for the spliceosomal core SmE protein by screening a yeast cDNA library by use of the yeast two-hybrid system. The three clones (SmX4, SmF, and SmG) that we isolated are members of the Sm and Sm-like protein families (5, 18, 47). The interaction detected between SmX4 and SmE was the most unexpected since these proteins reside on different snRNPs (47). One explanation for this result is that because all Sm and Sm-like proteins are likely to have similar shapes (47) and because Sm proteins interact with other Sm proteins, members of the family will display a low affinity for each other. This interpretation suggests that the SmX4-SmE interaction detected is nonspecific. This may be the case since we detected an equivalent weak interaction between SmE and SmX5, another Sm-like U6-associated protein (Table 1). The detection of a low level of interaction of the SmE protein with itself (Table 2) further supported the possibility that the two-hybrid system allows the detection of weak nonspecific interactions between Sm proteins. On the other hand, we did not detect interaction of yeast SmX4 with either SmF or SmG. Furthermore, the levels of β-galactosidase detected in the two-hybrid system with the SmE-SmX4, SmE-SmX5, and SmE-SmE combinations exceeded by far the background levels observed with any combination of different Sm core proteins (Table 2). However, although potential interactions between these proteins could take place in the U4/U6 and U4/U6.U5 particles, the biological relevance of these interactions, if any, are presently unclear.

Protein-protein interactions inside the Sm core complex.

We originally identified interactions of the yeast SmE with both SmF and SmG in a two-hybrid screen. To extend this observation, we identified the remaining yeast core Sm proteins in the database and analyzed interactions between all possible pairwise combinations of these proteins. Our results are consistent with previous data indicating the existence of multimeric complexes of mammalian Sm proteins such as D1.D2, E.F.G, D1.D2.E.F.G, and B/B′.D3 (18, 25, 37). Indeed, we show here the existence in vivo and in vitro of specific interactions between yeast Sm proteins SmE-SmF, SmE-SmG, and SmB-SmD3. Furthermore, no interaction between yeast SmF and SmG could be detected either in vivo (Table 2) or in vitro by using in vitro-translated SmF protein and purified GST-SmG fusion protein (data not shown). The SmB-SmD3 interaction has also been identified recently in an exhaustive two-hybrid screen by using yeast SmD3 as bait (14). Interestingly, the yeast SmB protein was not found in purified yeast U1 and U2 snRNPs (34). Our interaction results suggest that the yeast SmB protein would be part of the Sm core complex. This has been confirmed by showing that the yeast SmB protein coimmunoprecipitates the U1, U2, U4, and U5 snRNAs (40). We failed to detect an interaction between SmD1 and SmD2 (Table 2). This does not mean that SmD1-SmD2 interaction does not occur in yeast, and our failure to detect such a complex in vivo might be explained by poor folding of the SmD1 and/or SmD2 fusion proteins. Indeed, the yeast SmD1 is highly divergent (41, 42), with the insertion of 27 residues in the variable region separating two main conserved blocks of the Sm motif (47) (see below). Because of this insertion, the yeast SmD1 protein might be able to fold or stably interact with other proteins only in the presence of its cognate RNA binding site. Further studies will address this possibility. However, taken together, our results indicate a conservation of the protein-protein interaction sites in the yeast and mammalian Sm proteins. This suggests that the snRNP structure will be conserved and that snRNP assembly will follow similar pathways in the two species.

Mapping interaction surfaces of the yeast SmE protein.

All the Sm proteins contain a conserved structural domain which extends over 100 conserved residues interrupted by a nonconserved region of up to 30 amino acids (18, 47). A previous analysis of the human SmB′-SmD3 complex suggested that the Sm domain may be involved in protein-protein interactions (18). However, these studies were limited since the mutants used therein were truncation mutants which might have prevented the folding of an independent interaction domain. Our results support this idea. Indeed, we first analyzed the interaction properties of the two conserved regions of the Sm domain of the SmE protein expressed independently. Neither of these two domains were able to interact with other Sm proteins, and they did not interact with each other (Table 2). These data support the results from structure prediction that suggest that the nonconserved residues are located in a loop at the surface of a single globular domain (47). Further support for this model came from sensitive database searches which indicated that the two conserved regions are always associated in cis (47). These data suggest that the Sm domain should not be divided into two substructures (14, 18) but rather should be regarded as a single entity (47).

Since deletion analysis was unlikely to be successful in identifying residues important for Sm protein-Sm protein interaction, we turned to a detailed mutagenic study of the yeast SmE protein. By combining genetic in vivo selection of noninteracting mutants and site-directed mutagenesis, we identified 26 point mutants of the SmE protein. Our mutagenesis analysis first showed that residues located in the N-terminal nonconserved region (residues 1 to 10) of SmE are required neither for interaction with SmF and SmG nor for function of SmE. We did not recover lethal mutations in the SmE region from positions 59 to 76: two mutants, mutant E59A N63D and mutant P76S, are located in this region and possess nearly wild-type interaction and growth capabilities (Table 3 and Fig. 2). This region is 7 amino acids smaller in the human SmE protein. The fact that this latter protein is functional in yeast (3) supports the view that this region might be tolerant to mutations. We also analyzed the SmE-specific residue located at position 83 (Fig. 2B). The SmE protein sequences from all organisms differ from the core sequence at this position, where the arginine found in all Sm and Sm-like proteins is replaced by a lysine (18, 47). As shown in Fig. 2, replacement of the positively charged lysine by a nonpolar valine (mutant K83V) produces a moderate effect on SmF binding but does not affect SmG interaction and viability.

Residues of the Sm domain which were good candidates for a role in the interaction between Sm proteins are represented by the conserved residues. However, with the exceptions of residues G41 and D47, where mutations affect viability, analysis of conserved residues like M50, N51, E59, I80, G84, and N86 revealed, surprisingly, that amino acid substitutions at these positions produce only moderate phenotypes. For example, the mutant M50A interacts only at 50% of the wild-type level with its partners and retains its ability to grow. Likewise, mutants N51A, I80F, G84A, and N86A are also affected in binding with either SmF or SmG without obvious growth phenotypes. The fact that the conserved residues at these positions are tolerant to mutation suggests that the functions of these amino acids in Sm protein folding and/or interaction are redundant. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the highly evolutionarily conserved nucleotides from the U5 snRNA Sm binding site are also tolerant to mutation, suggesting redundancy in their function (16).

Our study shows that many positions not conserved at the amino acid level but conserved in physicochemical property are important for interaction between Sm proteins and for viability. With the exception of one amino acid substitution, that in mutant V27E, which leads to a nonstable protein fusion, our results show that hydrophobic conserved residues in the Sm domain of the SmE protein are essential for interactions with SmF and/or SmG and for cell viability. This is the case for residues I29, I54, L81, and I90. Q22 and D47 can probably be included since they are located next to conserved hydrophobic residues (L21 and F46) which might be affected in their positioning. These results indicate that all the hydrophobic residues may participate in the contact between Sm proteins. The observation that the Sm complex is stable at high salt concentrations further suggests that Sm-Sm protein interactions are mediated at least in part by hydrophobic contacts (26). Hydrophobic amino acids have been proposed to be important for other types of protein-protein interactions, for example, those between activators and the general transcriptional machinery (6).

Concerning specific binding, we have identified residues D47 and L81 in SmE as determinants of SmF binding. Mutants with mutations at either of these positions retain some ability to bind SmG, although the interaction of SmG with a mutant containing a mutation at position 47 is more affected. For SmG binding, our results suggest that the region of SmE starting at position 86 represents an interaction domain for SmG. Indeed, a comparison of the mutants N86A, L89Stop, and I90R indicates that mutants with mutations closer to the C terminus have a lower interaction level.

In conclusion, our mutational analysis shows that specific and highly conserved residues of SmE are dispensable for growth and play only a moderate role in the interaction of SmE with SmF and SmG. The SmE amino acids essential for interactions with SmF and SmG and for cell viability are represented by conserved hydrophobic residues dispersed over the Sm domain. Taken together, our results suggest that the SmE protein could bind SmF and SmG proteins at the same time. This view is consistent with the results showing that equimolar amounts of SmE, SmF, and SmG are present in the multimeric E.F.G complex (37).

Assembly of snRNPs in the SmE mutants.

We have shown that the mutations in only four SmE mutants (V27E, W30Stop, G41D, and G45Stop) give rise to unstable proteins and that mutants I54N, L81P, and I90R are assembled into snRNPs. Our results also suggest that hypomethylation may be the defective step in snRNP assembly for mutant L81P but not for mutant I54N. In addition, with two exceptions (G45V and I54N), we have shown a perfect correlation between the viability phenotypes observed for GAD-SmE mutant fusion proteins and those for mutant proteins produced from their natural promoter, suggesting that properties carried by the GAD domain do not interfere with SmE function in the majority of the mutants. This is not the case for the G45V and I54N mutants. Indeed, the presence of the GAD domain in the G45V mutant impairs function of the fusion protein, whereas the G45V mutant produced from its natural promoter is functional at a permissive temperature (Table 3). For mutant I54N, the GAD fusion protein is functional, in contrast to the protein produced from its natural promoter. This is surprising since in the two-hybrid system, this mutant shows background-level interaction with SmF and interacts only very poorly (10% of wild-type level) with SmG (Table 3 and Fig. 2). The fact that the GAD-I54N fusion protein is functional suggests that it is assembled into snRNPs able to follow a complete assembly pathway. Therefore, the GAD-I54N protein must present residual low interactions with both SmF and SmG which must be sufficient to allow core assembly. How can we explain the lethality of the SmE-I54N protein produced from its natural promoter? An explanation is that the GAD fusion positively influences the folding of the I54N mutant. Another possibility is that the I54N mutant protein is unstable in contrast to the GAD-I54N fusion protein. This does not seem to be the case, since our studies suggest that, at least in part, the I54N mutant assembles into snRNPs (Fig. 5). If snRNP biogenesis proceeds in yeast and mammals in similar manners, the low residual interaction with SmF and SmG of this mutant may not be sufficient to allow the formation of the bipartite signal for nuclear localization. Hence, nuclear targeting of the snRNPs would be impossible, explaining the lethality of the cells carrying the I54N mutant. Conceivably, the nuclear localization signal present in the GAD-I54N fusion protein could help to target the fusion protein to the nucleus. Further analysis is needed to resolve this issue.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. Walczak, P. Legrain, R. Lührmann, I. Mattaj, I. Palacios, and members of our groups for valuable discussions and/or comments on the manuscript. We appreciate the gift of anti-TMG antibodies from R. Lührmann. We also thank the reviewers for helpful suggestions. We are grateful for the excellent technical assistance of L. Brubacher, C. Burgard, and S. Kandels-Lewis.

This work was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and EMBL. B.S. is on leave from CNRS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Meyer E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bordonné R, Banroques J, Abelson J, Guthrie C. Domains of yeast U4 spliceosomal RNA required for PRP4 protein binding, snRNP-snRNP interactions, and pre-mRNA splicing in vivo. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1185–1196. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.7.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bordonné R, Tarassov I. The yeast SME1 gene encodes the homologue of human E core protein. Gene. 1996;176:111–117. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breeden L, Nasmyth K. Regulation of HO gene. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1985;50:643–650. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1985.050.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper M, Johnston L H, Beggs J D. Identification and characterization of Uss1p (Sdb23p): a novel U6 snRNA-associated protein with significant similarity to core proteins of small nuclear ribonucleoproteins. EMBO J. 1995;14:2066–2075. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cress W D, Triezenberg S J. Critical structural elements of the VP16 transcriptional activation domain. Science. 1991;251:87–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1846049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durfee T, Becherer K, Chen P-L, Yeh Y, Yang Y, Kilburn A E, Lee W-H, Elledge S J. The retinoblastoma protein associates with the protein phosphatase type I catalytic subunit. Genes Dev. 1993;7:555–569. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elledge S J, Davis R W. A family of versatile centromeric vectors designed for use in the sectoring-shuffle mutagenesis assay in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1988;70:303–312. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fabrizio P, Esser S, Kastner B, Lührmann R. Isolation of Saccharomyces cerevisiaesnRNPs: comparison of U1 and U4/U6.U5 to their human counterparts. Science. 1994;264:261–265. doi: 10.1126/science.8146658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fink G R, Guthrie C. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:3–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer U, Sumpter V, Sekine M, Satoh T, Lührmann R. Nucleocytoplasmic transport of U snRNPs: definition of a nuclear location signal in the Sm core domain that binds a transport receptor independently of the m3G cap. EMBO J. 1993;12:573–583. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05689.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer U, Heinrich J, Van Zee K, Fanning E, Lührmann R. Nuclear transport of U1 snRNP in somatic cells: differences in signal requirement compared with Xenopus laevisoocytes. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:971–980. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.5.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher U, Liu Q, Dreyfuss G. The SMN-SIP1 complex has an essential role in spliceosomal snRNP biogenesis. Cell. 1997;90:1023–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80368-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fromont-Racine M, Rain J C, Legrain P. Toward a functional analysis of the yeast genome through exhaustive two-hybrid screens. Nat Genet. 1997;16:277–282. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Good L, Nazar R N. An improved thermal cycle for two-step PCR-based targeted mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4934–4935. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.18.4934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haltiner Jones M, Guthrie C. Unexpected flexibility in an evolutionarily conserved protein-RNA interaction: genetic analysis of the Sm binding site. EMBO J. 1990;9:2555–2561. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harper J W, Adami G R, Wei N, Keyomarsi K, Elledge S J. The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell. 1993;75:805–816. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90499-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hermann H, Fabrizio P, Raker V A, Foulaki K, Hornig H, Brahms H, Lührmann R. snRNP Sm proteins share two evolutionarily conserved sequence motifs which are involved in Sm protein-protein interactions. EMBO J. 1995;14:2076–2088. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill J, Ian K A, Donald G, Griffiths D E. DMSO-enhanced whole cell yeast transformation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5791. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.20.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Izaurralde E, Mattaj I W. Transport of RNA between nucleus and cytoplasm. Semin Cell Biol. 1992;3:279–288. doi: 10.1016/1043-4682(92)90029-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarvis E E, Hagen D C, Sprague G F., Jr Identification of a DNA segment that is necessary and sufficient for α-specific gene control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: implication for regulation of α-specific and a-specific genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:309–320. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.1.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kambach C, Mattaj I W. Intracellular distribution of the U1A protein depends on active transport and nuclear binding to the U1 snRNA. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:11–21. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kandels-Lewis S, Séraphin B. Involvement of U6 snRNA in 5′ splice site selection. Science. 1993;262:2035–2039. doi: 10.1126/science.8266100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural protein during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehmeier T, Raker V, Hermann H, Lührmann R. cDNA cloning of the Sm proteins D2 and D3 from human snRNPs: evidence of a direct D1-D2 interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12317–12321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liautard J P, Sri-Widada J, Brunel C, Jeanteur P. Structural organization of ribonucleoproteins containing small nuclear RNAs from HeLa cells. J Mol Biol. 1982;162:623–643. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90392-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Q, Fisher U, Wang F, Dreyfuss G. The spinal muscular atrophy disease gene product, SMN, and its associated protein SIP1 are in a complex with spliceosomal snRNP proteins. Cell. 1997;90:1013–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lührmann R, Kastner B, Bach M. Structure of spliceosomal snRNPs and their role in pre-mRNA splicing. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1087:256–292. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(90)90001-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mattaj I W. Cap trimethylation of U snRNA is cytoplasmic and dependent on U snRNP protein binding. Cell. 1986;46:905–911. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mattaj I W. UsnRNP assembly and transport. In: Birnstiel M L, editor. Structure and function of the major and minor small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1988. pp. 100–114. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore M J, Query C C, Sharp P A. Splicing of precursors to mRNA by the spliceosome. In: Gesteland R F, Atkins J F, editors. The RNA world. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 303–357. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mumberg D, Müller R, Funk M. Regulatable promoters of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: comparison of transcriptional activity and their use for heterologous expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5767–5768. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.25.5767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelissen R L H, Will C L, von Venrooij W J, Lührmann R. The association of the U1-specific 70K and C protein with U1 snRNPs is mediated in part by common U snRNP proteins. EMBO J. 1994;13:4113–4125. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06729.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neubauer G, Gottschalk A, Fabrizio P, Séraphin B, Lührmann R, Mann M. Identification of the proteins of the yeast U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex by mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:385–390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patton J R. Formation of pseudouridine in U5 small nuclear RNA. Biochemistry. 1994;33:10423–10427. doi: 10.1021/bi00200a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plessel G, Fisher U, Lührmann R. m3G cap hypermethylation of U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP) in vitro: evidence that the U1 small nuclear RNA-(guanosine-N2)-methyltransferase is a non-snRNP cytoplasmic protein that requires a binding site on the Sm core domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4160–4172. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raker V A, Plessel G, Lührmann R. The snRNP core assembly pathway: identification of stable core protein heterometric complex and an snRNP subcore particule in vitro. EMBO J. 1996;15:2256–2269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riedel N, Wolin S, Guthrie C. A subset of yeast snRNAs contains functional binding sites for the highly conserved Sm antigen. Science. 1987;235:321–328. doi: 10.1126/science.2948278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy J, Zheng B, Rymond B C, Woolford J L., Jr Structurally related but functionally distinct yeast Sm D core small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:445–455. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rutz, B., J. Salgado, and B. Séraphin. Unpublished data.

- 41.Rymond B C. Convergent transcripts of the yeast PRP38-SMD1locus encode two essential splicing factors including the D1 core snRNP polypeptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:848–852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rymond B C, Rokeach L A, Hoch S O. Human snRNP polypeptide D1 promotes pre-mRNA splicing in yeast and defines nonessential yeast Smd1p sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3501–3505. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.15.3501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sauterer R, Goyal A, Zieve G W. Cytoplasmic assembly of small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles from 6S and 20S RNA-free intermediates in L929 mouse fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1048–1058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schägger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schiestl R H, Gietz R D. High efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells using single stranded nucleic acids as a carrier. Curr Genet. 1987;16:339–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00340712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]