Abstract

Background

First Nations Australians experience poorer cancer outcomes than other Australians. This is attributable to multidimensional factors, including disparities in access to cancer services and treatments. Radiotherapy (RT) is an important component of cancer treatment yet evidence of its utilisation among First Nations Australians is limited. We aimed to examine RT utilisation, time to the treatment, and associated factors in First Nations Peoples diagnosed with cancer in Queensland, Australia.

Methods

First Nations Queenslanders (N = 1884) and other Queenslanders (N = 104,204) diagnosed with any cancer between 1st July 2011 and 30th June 2015 and their RT details between 1st July 2011 and 30th June 2018 were identified using the Cancer CostMod dataset, comprising Queensland Cancer Registry data linked with Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data Collection (QHAPDC) and Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS). Analysis was limited to those with non-missing Indigenous status who linked to MBS and/or QHAPDC records (N = 105, 983). Differences in RT utilisation and waiting times by First Nations status were tested using logistic regressions, non-parametric tests, and quantile regression.

Results

Among 105, 983 people with a cancer diagnosis in Queensland, 28.6% had RT, with external Beam RT(EBRT) as the predominant type (n = 29,387, 96.9%). One-third (33.5%) of First Nations cancer patients received RT at least once, compared to 28.5% of other Queensland cancer patients (P < 0.001). After adjustment for covariates, First Nations cancer patients had a greater likelihood of RT utilisation than other Queenslanders (adjusted odds ratio(aOR): 1.15; 95% (confidence-interval (CI): 1.04–1.27) and more pronounced within the first year after diagnosis (aOR: 1.23: 95% CI:1.11–1.37). Among those receiving any RT, the median time from cancer diagnosis to first RT was 118 days (Interquartile-range (IQR): 55–232) for First Nations and 132 days (IQR: 59–258) for other Queenslanders (P = 0.034).

Conclusions

A higher proportion of First Nations cancer patients received RT than other Queensland cancer patients, particularly in the first year following diagnosis. However, RT utilisation for all cancer patients was notably lower (28.6%) than the national optimal RT(EBRT) rate of 48%. This finding highlights the need for RT to align with optimal care standards, which is crucial for improving cancer outcomes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13690-025-01638-9.

Keywords: Radiotherapy, Cancer, Utilisation, Time to initial treatment, Indigenous, Queensland

| Text box 1. Contributions to the literature |

|---|

| • RT is a critical component of cancer care in Australia, yet population-level comprehensive data on its use are scarce, limiting equity-focused cancer planning. |

| • This study uniquely integrates registry and administrative data to provide a comprehensive picture of RT use and timing for cancer patients across Queensland. |

| • It challenges the notion that higher service use necessarily indicates better cancer care, suggesting instead that increased RT utilisation may reflect later-stage diagnoses, highlighting the need for earlier detection. |

| • The study highlights gaps in meeting optimal RT benchmarks and calls for culturally safe, guideline-aligned models of cancer care. |

Background

Cancer is responsible for a high disease burden in Australia, with an estimated 169,000 new cases and 52,700 deaths in 2024 [1]. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (henceforth respectfully referred to as First Nations peoples) are disproportionately affected by cancer [2, 3], with cancer mortality rates 1.4 times higher than those of other Australians [3]. In Queensland, the state with the second largest First Nations population, cancer incidence and mortality in 2017–2021 were higher among First Nations Queenslanders than other Queenslanders (618 vs. 533 and 237 vs. 158 per 100,000, respectively). In addition, the 5 − year survival rate for First Nations was 63% compared to 76% for other Queenslanders [4]. This survival gap is partly attributable to inequities in access to cancer treatment and care [5–7].

Cancer treatment in Australia includes surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy (RT). RT is a non-invasive treatment modality [3, 8] that can potentially cure up to 40% of all cancers, including lung, breast, and prostate cancers, which are the most prevalent among First Nations Peoples [9–11]. RT is cost-effective, accounting for only 6 cents of every dollar invested by the Australian Government in cancer treatment [9]. It can be curative or palliative and may be administered externally (external beam radiation therapy (EBRT)) or internally (brachytherapy) and may continue for several weeks [12]. The latest (2012) RT utilisation benchmark suggests that ideally, 48% of all registered cancer patients in Australia would receive EBRT at some point during their treatment [13, 14]. However, a substantial number of cancer patients who should have received RT did not [15], contributing to preventable morbidity and mortality [13, 16]. While RT utilisation in Australia has improved in recent years (from 32% in 2014 to 39% in 2018), it is still below the recommended level [15]. In Queensland, the RT utilisation for patients with invasive cancer was 31% in 2009-18, lower than the global benchmarks of 44–48% [17, 18].

In Australia, there has been a significant investment in improving RT availability, particularly in regional areas [19]. Despite these efforts, cancer patients in rural and regional areas continue to face significant challenges in accessing RT [9, 10, 15, 20]. Besides distance to treatment centres [15, 21–23], RT utilisation in Australia is influenced by various factors, including age, socio-economic status, and disease characteristics [22–24]. While not consistently observed, older age, living in the most disadvantaged areas, and localised compared to metastatic disease have all reportedly been associated with lower RT utilisation [22–25]. Although timely access to RT is crucial for optimal outcomes—often requiring initiation within four weeks or 28 days of the ready-for-care date (i.e., the date on which a patient is clinically prepared and available to commence RT) − regional and rural patients frequently experience longer RT waiting times in Queensland [26]. This may be due, among other factors, to rural patients having to travel longer distances and having limited availability of accommodation near RT centres, thus delaying the commencement of RT.

First Nations peoples in Australia also encounter barriers to accessing RT, including the financial burden of travelling long distances and lower rates of private health insurance [25]. Comprehensive data on RT utilisation and waiting times of First Nations peoples with cancer are lacking, and existing evidence is inconsistent. For instance, a study conducted in New South Wales (NSW) found comparable RT utilisation between First Nations and other Australians for lung and breast cancer but higher utilisation for First Nations peoples for bowel cancer [25]. Another study in South Australia that included all cancers indicated lower RT utilisation among First Nations patients (40% versus 46%, respectively) [27]. Studies conducted in Queensland over a decade ago also reported disparities in cancer care and treatment, documenting lower RT utilisation among First Nations cancer patients, even after adjusting for factors such as cancer stage at diagnosis [7, 28, 29]. Recent in-depth evidence on RT utilisation trends and the time between diagnosis and treatment is lacking for First Nations Queenslanders. In this context, this study aims to investigate RT utilisation and waiting times among First Nations cancer patients in Queensland using linked administrative data.

Methods

Study setting and population

The study was conducted in Queensland, Australia, using the Queensland Cancer CostMod dataset, previously described elsewhere [30, 31]. In brief, Cancer CostMod is a population-based dataset containing all cancer diagnoses (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) recorded in the Queensland Cancer Registry (QCR) [31], originally for the period from 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012 and later expanded to 30 June 2015 [32, 33]. These records were linked to administrative healthcare data sources, including the Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data Collection (QHAPDC), and Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) for the period between 1 July 2011 and 30 June 2018 [31].

A total of 106,749 cancer patients were registered in QCR in 2011-15 and included in Cancer CostMod. Information about the patients such as cancer diagnosis date, International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O) code, morphology, differentiation, and vital status was recorded in the QCR dataset, in addition to socio-demographic information such as sex, postcode at the time of diagnosis, and First Nations status (reported for 99.4% of QCR record). Since 1996, Indigenous status has been consistently documented in the patient administration systems of Queensland public hospitals [29, 34]. The cancer registry collects this information through the cancer notification process from these hospitals [29].

Sample size considerations

Among the registered cancer cases (N = 106,749), 106,088 had non-missing Indigenous status, and of these, 105,983 were linked to MBS and/or QHAPDC and used for final data analysis.

Study outcome: radiotherapy

RT information was obtained from the linked MBS and QHAPDC data using MBS item numbers and/or the Australian Classification of Health Interventions (ACHI)) codes, respectively. These codes were identified through an extensive review of the MBS and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) websites and previous publications [25, 35, 36], coupled with consultations with radiation oncology specialists. The types of RT recorded were mainly EBRT, such as Megavoltage, and brachytherapy (internal RT).

The QHAPDC procedure (or ACHI) data include codes for various types of RT, along with the dates on which patients receive the RT. The MBS item numbers for RT include the dates on which the Medicare claims were submitted.

In this study, the commencement of RT is defined as the first recorded instance of any RT procedure or MBS claim for RT following a cancer diagnosis. These records are identified within the QHAPDC procedure (or ACHI code) data, within the MBS data using item numbers, or within both datasets. When records appeared in both datasets, we chose the earliest RT date. The waiting time (in days) was calculated as the duration between the diagnosis date and the first RT date. This serves as a proxy measure, consistent with the approach used in a previous Queensland study [37]. RT use was assessed up to the end of follow-up (30 June 2018). All included patients had a minimum of three years of follow-up.

Sociodemographic and clinical factors

Demographic factors included age at diagnosis, sex, area-level socio-economic status, and residential remoteness. Patients’ comorbidity (excluding cancer as a comorbidity) was also included using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), a weighted score reflecting patient comorbidities, as detailed in a prior study on the Cancer CostMod dataset [32]. A CCI score of 0 indicates no comorbidity, while 1 + denotes one or more comorbidities. Socioeconomic status was classified by residential postcode at diagnosis using area-based indicators from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage (IRSD) [38]. IRSD quintile 1 indicates the most disadvantaged, and quintile 5 the least disadvantaged. Remoteness was classified using the Australian Statistical Geography Standard—Remoteness Area (ASGS-RA). The ASGS has five remoteness area (RA) categories: metropolitan, inner regional, outer regional, remote, and very remote [32, 39]. For the analysis, we combined inner and outer regional categories into one ‘regional’ category and remote and very remote into one ‘remote’ category.

The Queensland Cancer Registry (QCR) did not provide sufficient information to assess cancer stage at diagnosis, and therefore, this study could not account for this variable.

Statistical analysis

Socio-demographic characteristics were described and compared by First Nations status using frequency (%) and median (IQR: Interquartile Range). RT utilisation by First Nations status and sociodemographic or clinical factors were tested using the Pearson Chi-squared test or Fisher exact test used for categorical data (proportions), time to RT commencement (in days) was compared using non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis) by First Nations status, and other covariables.

The likelihood of RT utilisation by First Nations status (odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI)) was estimated using logistic regression and adjusted for demographic, socioeconomic, and co-morbidity variables. A sensitivity analysis examining the likelihood of RT utilisation by First Nations status, stratified by cancer types, was conducted as a post-hoc analysis. Furthermore, quantile or median regression was used to quantify the difference in median time to the first RT between First Nations and other Queensland cancer patients, adjusting for relevant measured factors.

All analyses were performed using STATA version 18 (Stata Statistical Software. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC). A two-sided P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approvals

Approval was obtained from the following Human Research Ethics Committees (HRECs): Townsville Hospital and Health Service (HREC/16/QTHS/110); Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (EO2017/1/343); James Cook University (H6678); and The University of Queensland (2022/HE002538: 23/01/2023). Queensland Health waived the requirement for individual consent under the Public Health Act 2005. No identifiable information was disclosed to the study team.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

Between 1 July 2011 and 30 June 2015, a total of 105,983 individuals with non-missing Indigenous status, who were linked to the MBS/QHAPDC dataset, were diagnosed with cancer and registered in Queensland. This includes 1,879 First Nations Australians. Compared to other Queensland cancer patients, First Nations cancer patients were younger at diagnosis (median age 60 vs. 67 years) (Table 1). Females accounted for just over half (51%) of First Nations cancer patients, while males accounted for the majority (56%) of other Queensland patients. Most First Nations patients (74%) lived in regional or remote areas, while 91% of other Queenslanders lived in major cities or regional areas. A greater proportion of First Nations patients were from the most disadvantaged areas (20% vs. 9%) and had comorbidities (36% vs. 29%). Common cancers among First Nations patients were lung (n = 292, 16%), breast (n = 229, 12%), and prostate (n = 180, 10%), while prostate (n = 15,746, 15%), melanoma (n = 15,124, 15%), and breast (n = 13,310, 13%) were more common among other Queenslanders. The number of First Nations people diagnosed with cancer increased consistently from 2011 to 12 to 2014-15 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of cancer patients registered in Queensland, 1 July 2011–30 June 2015 by First Nations status (N = 105,983)

| Variable name | Variable group | First Nations N = 1879 (1.8%) |

Other Queenslanders N = 104, 104 (98.2%) |

P-values* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, median (IQR) | Age continuous | 60 (49–68) | 67 (57–76) | |

| n (%) n (%) | ||||

| Age group in years | 0–24 | 79 (4.2) | 1,376 (1.3) | < 0.001 |

| 25–49 | 397 (21.1) | 12,688 (12.2)) | ||

| 50–64 | 735 (39.1) | 29,994 (28.8) | ||

| 65+ | 668 (35.6) | 60,046 (57.7) | < 0.001 | |

| Gender | Male | 923 (49.1) | 57,924 (55.6) | |

| Female | 956 (50.9) | 46,180 (44.4) | ||

| Remoteness | Major city | 435 (23.2) | 49,059 (47.1) | < 0.001 |

| Regional | 876 (46.6) | 46,090 (44.2) | ||

| Remote | 516 (27.5) | 8,229 (7.9) | ||

| Missing | 52 (2.8) | 726 (0.7) | ||

| Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage | Quintile 1 (most disadvantaged) | 377 (20.1) | 9,105 (8.8) | < 0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 154 (8.2) | 4,493 (4.3) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 413 (21.9) | 16,708 (16.1) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 619 (32.9) | 48,090 (46.2) | ||

| Quintile 5 (least disadvantaged) | 264 (14.1) | 24,982 (24.0) | ||

| Missing | 52 (2.8) | 726 (0.7) | ||

| Common cancer types | All cancers | 1879 (1.8) | 104, 104 (98.2) | |

| Lung | 292 (15.5) | 8,512 (8.2) | < 0.001 | |

| Breast | 229 (12.2) | 13,310 (12.8) | ||

| Prostate | 180 (9.6) | 15,746 (15.1) | ||

| Colon | 101 (5.4) | 8,010 (7.7) | ||

| Melanoma | 79 (4.2) | 15,124 (14.5) | ||

| Uterine | 76 (4.0) | 1,754 (1.7) | ||

| Non-hodgkin lymphoma | 60 (3.2) | 3,709 (3.6) | ||

| Other sites | 862 (45.9) | 37,939 (36.4) | ||

| Year of diagnosis** | 2011-12 | 406 (21.6) | 25,820 (24.8) | < 0.001 |

| 2012-13 | 419 (22.3) | 25,604 (24.6) | ||

| 2013-14 | 472 (25.1) | 26,279 (25.2) | ||

| 2014-15 | 582 (30.9) | 26,401 (25.4) | ||

| Comorbidity | No | 1,166 (62.1) | 71,402 (68.6) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 679 (36.1) | 30,225 (29.0) | ||

| Missing | 34 (1.8) | 2,477 (2.4) | ||

*p-values are from X2 test. The test did not include missing (unknown) values

**The year of diagnosis is for the period between 1 July and 30 June

Radiotherapy utilisation

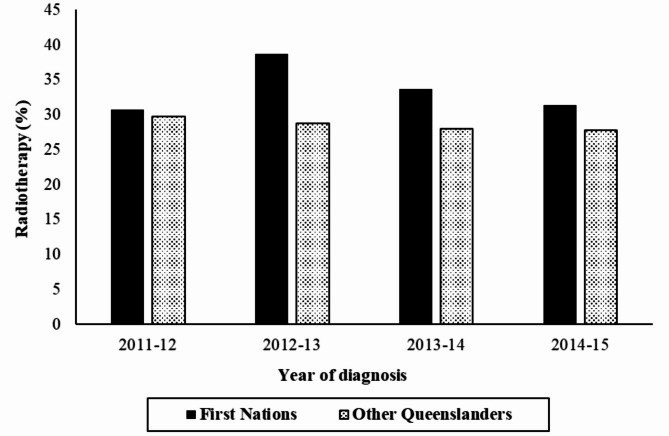

Among the 105,983 patients included in the study, 30,329 (28.6%) received RT at least once (Table 2). RT utilisation was 33.5% in First Nations patients, higher than 28.5% in other Queensland cancer patients (P < 0.001) (Table 2). RT utilisation was higher in patients aged 25–49 (30%) and 50–64 (34%) than in other age groups, higher for females (32%) than for males, and higher for those with comorbidities (34%) than without (Ps < 0.001). However, RT utilisation was similar across residential remoteness categories (P = 0.513) (Table 2). RT utilisation varied by cancer type, with relatively high utilisation among people with breast cancer (63%), lung cancer 42%), and prostate cancer (33%) (Table 2). The RT utilisation among First Nations cancer patients increased markedly between 2011-12 (31%) and 2012-13 (39%), then declined steadily to 31% in 2014-15. In contrast, it decreased steadily from 30% in 2011-12 to 28% in 2014-15 among other Queenslanders (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Radiotherapy utilisation among cancer patients diagnosed in Queensland, 1 July 2011–30 June 2015 (N = 105,983)

| Variable name | Variable group | RT yes N = 30,329 (28.6) n (%) |

RT no N = 75, 654 (71.4) n (%) |

P-values* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Nations status | First Nations | 629 (33.5) | 1,250 (66.5) | < 0.001 |

| Other Queenslanders | 29,700 (28.5) | 74,404 (71.5) | ||

| Age group in years | 0–24 | 351 (24.1) | 1,104 (75.9) | < 0.001 |

| 25–49 | 3,930 (30) | 9,155 (70) | ||

| 50–64 | 10,309 (33.5) | 20,420 (66.5) | ||

| 65+ | 15,739 (25.9) | 44,975 (74.1) | < 0.001 | |

| Gender | Male | 15,343 (26.1) | 43,504 (73.9) | |

| Female | 14,986 (31.8) | 32,150 (68.2) | ||

| Remoteness | Major city | 14,287 (28.9) | 35,207 (71.1) | 0.513 |

| Regional | 13,446 (28.6) | 33,520 (71.4) | ||

| Remote | 2,478 (28.3) | 6,267 (71.7) | ||

| Missing | 118 (15.2) | 660 (84.8) | ||

| Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage | Quintile 1 (most disadvantaged) | 2,632 (27.8) | 6,850 (72.2) | < 0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 1,290 (27.8) | 3,357 (72.2) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 5,137 (30) | 11,984 (70) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 14,001 (28.7) | 34,708 (71.3) | ||

| Quintile 5 (least disadvantaged) | 7,151 (28.3) | 18,095 (71.7) | ||

| Missing | 118 (15.2) | 660 (84.8) | ||

| Common cancer types | All cancers | 30, 329 (28.6) | 75, 654 (71.4) | |

| Lung | 3,651 (41.5) | 5,153 (58.5) | < 0.001 | |

| Breast | 8,566 (63.3) | 4,973 (36.7) | ||

| Prostate | 5,239 (32.9) | 10,687 (67.1) | ||

| Colon | 552 (6.8) | 7,559 (93.2) | ||

| Melanoma | 1,270 (8.4) | 13,933 (91.7) | ||

| Uterine | 492 (26.9) | 1,338 (73.1) | ||

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 771 (20.5) | 2,998 (79.5) | ||

| Other sites | 9,788 (25.2) | 29,013 (74.8) | ||

| Year of diagnosis** | 2011-12 | 7,784 (29.7) | 18,442 (70.3) | < 0.001 |

| 2012-13 | 7,518 (28.9) | 18,505 (71.1) | ||

| 2013-14 | 7,526 (28.1) | 19,225 (71.9) | ||

| 2014-15 | 7,501 (27.8) | 19,482 (72.2) | ||

| Comorbidity | No | 19,502 (26.9) | 53,066 (73.1) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 10,634 (34.4) | 20,270 (65.6) | ||

| Missing | 193 (7.7) | 2,318 (92.3) |

*p-values are from X2 test. The test did not include missing (unknown) values

**The year of diagnosis is for the period between 1 July and 30 June

Fig. 1.

Proportion of cancer patients starting radiotherapy by year of diagnosis and First Nations status in Queensland, 1 July 2011–30 June 2015

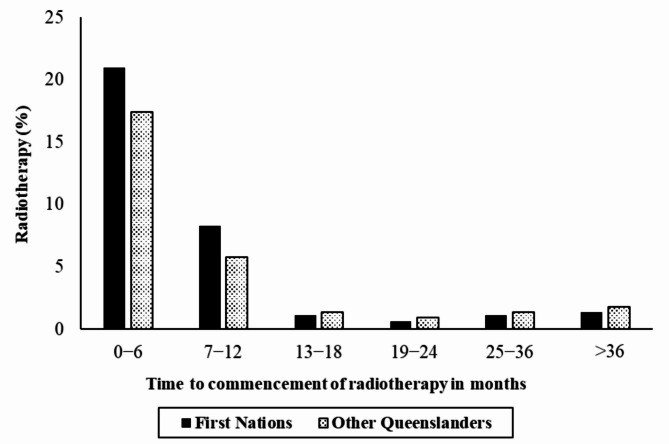

The majority of RT (n = 24,698, 81.4%) began within the first year following a cancer diagnosis. During this period, the proportion of RT utilisation was higher among First Nations cancer patients (29%) than among other Queensland cancer patients (23%) (P < 0.001) (Table S1 and Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Proportion of cancer patients starting radiotherapy at different time points following diagnosis by First Nations status in Queensland, 1 July 2011–30 June 2015

Among those with any RT, EBRT was the predominant treatment for both First Nations (98.7%) and other Queensland cancer patients (97.1%) (P = 0.014) (Table S2). The overall EBRT use was 27.7% among all cancer patients, while brachytherapy use was only 0.8%. The majority of all brachytherapy was used to treat prostate cancer (69%) followed by uterine cancer (7.5%) (Table S2).

Radiotherapy and associated factors

After adjusting for covariates, First Nations cancer patients were more likely to receive RT than other Queensland cancer patients (aOR: 1.15: 95% CI:1.04–1.27). This pattern was more pronounced within the first year after diagnosis (aOR: 1.23: 95% CI:1.11–1.37). RT utilisation was also associated with socio-demographic characteristics. For example, female gender was associated with an increased likelihood of RT utilisation, while residing in remote areas was associated with a decreased likelihood (Table 3). Patients with comorbidity had a greater likelihood of receiving RT than those with no comorbidity (aOR: 1.54: 95% CI:1.49–1.58), and the odds of RT utilisation decreased steadily from 2011-12 to 2014-15 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with radiotherapy among cancer patients in Queensland, 1 July 2011–30 June 2015 (N = 105,983)

| Variable name | Variable group | cORa | aORb |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Nations status | First Nations | 1.26 (1.14–1.39) * | 1.15 (1.04–1.27) * |

| Other Queenslanders | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Age group in years | 0–24 | 0.91 (0.80–1.03) | 0.99 (0.88–1.12) |

| 25–49 | 1.23 (1.18–1.28) * | 1.29 (1.24–1.35) * | |

| 50–64 | 1.44 (1.40–1.49) * | 1.52 (1.47–1.56) * | |

| 65+ | 1:00 | 1.00 | |

| Gender | Male | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 1.32 (1.28–1.35) * | 1.33 (1.29–1.36) * | |

| Remoteness | Major city | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Regional | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | |

| Remote | 0.97 (0.93–1.02) | 0.94 (0.89–0.99) * | |

| Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage | Quintile 1 (most disadvantaged) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.94–1.06) |

| Quintile 2 | 0.97(0.90–1.04) | 1.00 (0.93–1.08) | |

| Quintile 3 | 1.08 (1.04, 1.13) * | 1.09 (1.04–1.14) * | |

| Quintile 4 | 1.02 (0.99–1.06) | 1.04 (1.00-1.08) * | |

| Quintile 5 (least disadvantaged) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Year of diagnosis** | 2011-12 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2012-13 | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) * | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) * | |

| 2013-14 | 0.93 (0.89–0.96) * | 0.93 (0.89–0.96) * | |

| 2014-15 | 0.91 (0.88–0.95) * | 0.91 (0.88–0.95) * | |

| Comorbidity | No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.43 (1.39–1.47) * | 1.54 (1.49–1.58) * |

Odds ratio (OR) from logistic regression analysis;acOR: unadjusted odds ratio;baOR: adjusted odds ratio. *p < 0.05. **The year of diagnosis is for the period between 1 July and 30 June. Note: A separate model replacing age group with cancer type: First Nations: aOR: 1.149 (1.04–1.27)

The sensitivity analysis revealed variations in the magnitude and direction of associations by cancer type. Breast, prostate, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma exhibited higher odds of RT, while colon, melanoma, and uterine cancers showed lower odds of RT among First Nations peoples (Table S3 and Figure S1).

Time to initial RT following cancer diagnosis

Among all cancer patients who had RT (n = 30,329), the median time to initial RT following diagnosis was 132 days (IQR: 59–258). For First Nations cancer patients, the median time was 118 days (IQR: 55–232), compared to 132 days (IQR: 59–258) for other Queensland cancer patients (P = 0.034) (Table 4). Among First Nations cancer patients, females started RT on average 145 days after diagnosis (IQR: 67–236), while males started 92 days after diagnosis (IQR: 46–223.5). On the contrary, among other Queensland cancer patients, females started RT on average 125 days (IQR: 63–217), sooner than males of 139 days (IQR: 53–377) following a cancer diagnosis.

Table 4.

Time (in days) to first radiotherapy following cancer diagnosis among patients in Queensland, 1 July 2011–30 June 2015 (N = 30,329)

| Variable name | Variable group | Waiting time, Median (IQR) | Adjusted Beta-coefficientc |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Nations statusa | First Nations | 118 (55–232) | -17 [-35.30, 1.30] |

| Other Queenslanders | 132 (59–258) | Ref | |

| Age group in yearsb | 0–24 | 147 (64–250) | 22 [-2.29, 46.29] |

| 25–49 | 163 (69–229) | 48 [39.74, 56.26] * | |

| 50–64 | 126 (56–243) | 7 [1.22, 12.78] * | |

| 65+ | 124 (57–293) | Ref | |

| Gendera | Male | 139 (53–373) | Ref |

| Female | 125 (63–217) | -18 [-23.34, -12.66] * | |

| Remotenessb | Major city | 125 (58–250) | Ref |

| Regional | 137 (59–264) | 8 [1.63, 14.37] * | |

| Remote | 136 (60–257) | 12 [1.49, 22.51] * | |

| Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantageb | Quintile 1 (most disadvantaged) | 137 (56–276) | 5 [-6.64, 16.64] |

| Quintile 2 | 143 (62–270) | 8 [-6.66, 22.66] | |

| Quintile 3 | 126 (61–256) | -3 [-11.97, 5.97] | |

| Quintile 4 | 134 (59–258) | 6 [-1.08, 13.08] | |

| Quintile 5 (least disadvantaged) | 125 (57–246) | Ref | |

| Year of diagnosisb** | 2011-12 | 140 (62–284) | Ref |

| 2012-13 | 132 (60–258) | -8 [-15.27, -0.73] * | |

| 2013-14 | 133 (59–258) | -5 [-12.27, 2.27] | |

| 2014-15 | 119 (54–243) | -18 [-25.28, -10.72] * | |

| Comorbiditya | No | 131 (62–236) | Ref |

| Yes | 133 (51–357) | 5 [-0.47, 10.47] | |

| Common cancer typesb | All cancers | 132 (59–258) | |

| Lung | 57 (29–161) | ||

| Breast | 152 (83–213) | ||

| Prostate | 244 (151–511) | ||

| Colon | 637 (188–1199) | ||

| Melanoma | 563 (162–1098) | ||

| Uterine | 152 (105–242) | ||

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 187 (120–363) | ||

| Other sites | 66 (39–175) |

aMann–Whitney U test and bKruskal–Wallis test showed P < 0.05 for all the variables in the table

cAdjusted beta-coefficient from median (quintile) regression, including variables in the table (N.B. cancer type not included because of multicollinearity)

**The year of diagnosis is for the period between 1 July and 30 June

Cancer patients in major cities (median: 125 days, IQR: 58–250) received RT sooner than those in regional (median: 137 days, IQR: 59–264) and remote areas (median: 136 days, IQR: 60–257) (P < 0.001), with median regression showing that patients in remote areas, on average, wait 12 days longer to commence RT compared to those in major cities (P = 0.025) after adjusting for other factors (Table 4). Cancer patients residing in areas classified as IRSD Quintile 5 (least disadvantaged) (median: 125 days, IQR: 57–246) and IRSD Quintile 3 (median: 126 days, IQR: 61–256) experienced relatively shorter RT waiting times (P = 0.016). Cancer patients aged 25–49 years waited 48 days longer on average to commence RT compared to those aged 65 years and older (P < 0.001) (Table 4).

The average waiting time for RT dropped substantially from 2011-12 to 2014-15 for both First Nations (from 172 to 94 days) and for other Queensland cancer patients (from 140 to 119 days) (Figure S2). The decline in the median waiting time for First Nations cancer patients was particularly marked between 2011-12 (172 days) and 2012-13 (108 days).

Discussion

This study examined RT utilisation and waiting times among First Nations and other Queenslanders following a diagnosis of any cancer between 1 July 2011, and 30 June 2015, using linked administrative data. RT utilisation was higher among First Nations cancer patients (33.5%) compared to other Queensland cancer patients (28.5%, P < 0.001), with an increased likelihood of RT use (aOR: 1.15, 95% CI: 1.04–1.27). On average, RT was initiated sooner for First Nations cancer patients (within a median of 118 days) than for other Queensland cancer patients (132 days) (P = 0.034). The most common type of RT used was EBRT such as Megavoltage (97%).

First Nations Queenslanders with cancer diagnosis were more likely to receive RT, especially in the first year after diagnosis, compared to other Queensland cancer patients. This may suggest that cancer is diagnosed at more advanced stages in First Nations patients, where RT is an integral component of curative treatment. RT is often considered one treatment option for advanced cancer and plays an important role in palliative care [10]. Studies from NSW and Victoria also found increased RT use in metastatic cases compared to localised cancers. In advanced cases, surgery may no longer be an option due to metastasis, making RT more beneficial for First Nations patients, who are more likely to be diagnosed late [40, 41]. In contrast, other Australian patients tend to undergo surgery more frequently [7, 25, 28]. Consistent with our findings, Métis cancer patients in Manitoba, Canada, showed higher RT use [42]. A study in NSW reported significantly higher RT use for First Nations bowel cancer patients (aOR 1.48, 95% CI 1.00–2.19, P = 0.05) [25]. However, several studies from Queensland, South Australia, NSW, Canada, and New Zealand indicated lower RT utilisation among First Nations patients compared to others [7, 27–29, 43, 44]. This could be due to differences in analyses that adjust for cancer stage at diagnosis, which could not be done in our study because staging information was not widely available. More data are needed to explore these variations and other contributing factors.

Evidence suggests that in Australia, the optimal RT utilisation rate (O-RUR)—the proportion of patients who should receive RT at least once during their illness—is key for planning and monitoring RT services [18]. Globally, modelled O-RUR ranges from 44 to 48% [17, 18]. In Australia, the overall O-RUR for EBRT was 48.3% in 2012 [13, 14]. However, actual “real-life” RT rates (the proportion of cancer patients within a jurisdiction undergoing RT during a specified time frame) consistently fall short of this benchmark. Average RT utilisation varied across countries and states [15, 21, 45–49], ranging from 26% in the USA (2010–2012) to 39% in Australia (2018) and Ontario, Canada (2015–2016). In our study, EBRT use in Queensland was 27.7% for all cancer patients and 32.9% for First Nations patients, both below O-RUR estimates [13, 14, 17, 18]. Additionally, the likelihood of RT utilisation in remote areas was revealed to be lower compared to those in major cities, which may result in patients missing clinically appropriate treatment. The RT rates in this study are compared to Australian and global O-RUR models only as a general guide—as done in the Radiation Oncology Report in Queensland [49]. Therefore, these comparisons should be interpreted with caution, as the methods and sample used to derive the rates differ from those in our study [26]. Given the heightened mortality and poorer survival rates among First Nations people with a cancer diagnosis, efforts should focus on ensuring access to RT when clinically appropriate.

The time between diagnosis and receiving RT is critical, as delays can negatively affect outcomes [10, 50, 51]. Most cancer patients should start RT within 28 days of being ready for treatment, with those needing high-priority care starting within 14 days [10]. In Queensland, 54% of First Nations cancer patients in 2009–2013 and 46% in 2014–2018 began RT more than 45 days after diagnosis [26]. Our study found that the median time from diagnosis to first RT for First Nations patients was 118 days, highlighting the need to assess whether this meets optimal care standards by accounting for the patient’s ready-for-care date, which is based on various patient or system-level factors. While RT preparation (including pre-treatment imaging or medical testing) is necessary, it usually should not take more than a few months. Our study also revealed that cancer patients in remote areas of Queensland waited 12 days longer for RT compared to those in major cities (P = 0.025), highlighting that these delays may be influenced by various factors, including accessibility to RT facilities, availability of radiation oncology experts, referral pathways, patient preferences, and the healthcare system’s efficiency in preparing patients for RT, along with treatment history and other system or patient-level factors [10, 26, 47, 52–55].

Acknowledging the unique needs of First Nations Australians in radiation oncology is crucial due to their distinct cancer profiles, delayed diagnoses, limited access to treatments, and lower survival rates [10, 56]. Our study showed greater RT utilisation among First Nations patients, at least some of which may be due to more advanced diseases. This highlights the importance of understanding and overcoming barriers to routine healthcare and improving the timeliness of diagnosis among First Nations people. Importantly, RT utilisation was lower than O-RURs, with a sizable waiting time before RT initiation. To address these issues, priority actions include ensuring culturally competent care, offering culturally appropriate educational resources, building trust in mainstream health services, and providing person-centered approaches [10, 57–63]. Preliminary evaluations show that culturally safe initiatives have increased RT utilisation among First Nations Australians [64]. Collaborative efforts, such as increasing the presence of First Nations health professionals and integrating culturally competent care into training, are essential [56–61, 63]. Expanding Indigenous-led health services, like Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs), is vital for improving cancer care access, including RT. Through their trusted networks, ACCHOs can help streamline referrals, coordinate timely access to radiation oncologists, and support patients throughout their treatment [57]. Improving RT utilisation and reducing waiting times, especially in the face of access and service availability challenges, require enhanced service delivery, optimised referral pathways, and broader access to specialty care. Overall, the key findings of this study warrant critical interpretation. The higher RT use observed among First Nations patients may reflect later-stage diagnoses—a commonly reported issue in this population group—where curative treatments such as surgery are no longer feasible. Thus, rather than merely indicating improved access to RT, the increased utilisation may instead signal delays in diagnosis, thereby limiting treatment options.

Strengths and limitations

The primary strength of this study lies in its population-based approach and the integration of hospital and MBS data, ensuring a comprehensive capture of RT utilisation, which may be inadequately represented in studies relying solely on hospital records. A key strength is the use of Cancer CostMod, a population-based dataset that includes all cancer diagnoses from the Queensland Cancer Registry (QCR) and links with several key administrative healthcare data sources [31–33]. This study is the first to comprehensively examine RT use in Queensland, analysing cancer type, socio-demographic factors, time to RT initiation, and RT utilisations by different time points, types, and First Nations status. Data linkage has also improved the identification of First Nations status [34]. Since 1996, Indigenous status has been consistently recorded in Queensland public hospitals, and the cancer registry collects this data via hospital notifications [29]. In our study, First Nations status was recorded for 99.4% of QCR observations. However, it remains essential to sustain and enhance the inclusion of First Nations status in cancer registries and explore methods for verifying its accuracy.

A key limitation of this study is its reliance on administrative data. While such databases offer population-based insights into cancer care, they lack important variables like cancer stage at diagnosis, a critical factor in treatment decision-making [65, 66]. This highlights the need for efficient strategies to capture clinical data [7, 28, 29]. Establishing research-focused databases with comprehensive longitudinal data would be a long-term solution. Importantly, while we acknowledge the limitation of missing cancer stage information, higher RT utilisation among First Nations patients may reflect true underlying differences in disease presentation and treatment pathways. First Nations Australians are more likely to be diagnosed with cancer at later stages, when surgery may not be feasible, and RT becomes the primary or palliative treatment option. The persistence of our findings after adjusting for key demographic, geographic, and comorbidity variables strengthens the likelihood that the observed differences are real and reflect systemic differences in cancer care delivery rather than artefacts of unmeasured confounding. Additionally, the consistency of our findings with related studies [25, 42], both in Australia and internationally, strengthens the plausibility that our results reflect real disparities.

The study could not evaluate whether treatments follow guidelines or assess treatment approaches (neo- or adjuvant) and prior treatments (surgery, chemotherapy). The actual RT utilisation rate estimated in our study may not reflect the clinical appropriateness of care as opposed to O-RUR. Therefore, our study findings reflect real-world patterns and should not be interpreted as indicators of optimal or guideline-concordant care. Although the time to first RT treatment offered useful insights, it did not account for the patient’s ready-for-care date, requiring careful interpretation. Including First Nations status in the AIHW − Radiotherapy Waiting Time National Minimum Data (RWT NMDS), a dataset designed to monitor and report on the waiting times for radiotherapy across Australia, could help address this [67]. Additionally, incomplete hospital procedure dates affected the accuracy of calculating the time to treatment for some observations. While the data covers an older period, the findings provide essential insights for policy, practice, and future research with more up-to-date and nationwide data.

Conclusion

First Nations cancer patients were more likely to receive RT than other Queensland cancer patients, especially within the first year of diagnosis. However, the proportion of RT utilisation remains considerably lower than the O-RUR for both groups. Our findings highlight the need to explore the gap in RT utilisation by accounting for factors like cancer stage, as well as the importance of critically assessing the time between cancer diagnosis and the start of RT by considering the patient’s ready-for-care date. This evaluation is essential to determine if the timeline aligns with optimal care standards, which is vital for achieving better treatment outcomes. The unique needs of First Nations Australians in the context of radiation oncology should be considered due to their distinct cultures, cancer incidence patterns, delayed diagnosis, lower survival rates, and ongoing challenges in accessing treatments. Such an approach is needed to ensure timely and equitable access to lifesaving health services and improved cancer outcomes for First Nations Australians.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Table S1: Radiotherapy commencement at different time points after cancer diagnosis in QLD, 1 July 2011 and 30 June 2015 (N = 30, 329).

Supplementary Material 2: Table S2: The distribution of different types of radiotherapy across socio-demographic characteristics of patients diagnosed with cancer in QLD, 1 July 2011 and 30 June 2015 (n = 30, 268).

Supplementary Material 3: Table S3: Stratification analysis by cancer type (top 12 cancers in First Nations Peoples) to examine the radiotherapy among First Nations compared to other Queenslanders with a cancer diagnosis, 1st July 2011-30th June 2015.

Supplementary Material 4: Fig. S1: Stratification analysis for selected cancer types (number of cases at least 100 for First Nations Peoples) to examine the radiotherapy among First Nations compared to other Queenslanders with a cancer diagnosis, 1st July 2011-30th June 2015.

Supplementary Material 5: Fig. S2: Average waiting time in days among First Nations and other Queenslanders with a cancer diagnosis in QLD, 1 July 2011 and 30 June 2015

Abbreviations

- ACCHOs

Aboriginal community-controlled health organisations

- ACHI

Australian classification of disease

- AIHW

Australian institute of health and welfare

- aOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- CCI

Charlson comorbidity index

- CI

Confidence interval

- cOR

Crude odds ratio

- EBRT

External beam radiation therapy

- IRSD

Index of relative socio-economic disadvantage

- ICD

International classification of disease

- IQR

Interquartile range

- MBS

Medicare benefits schedule

- NSW

New south wales

- O-RUR

Optimal radiation utilisation rate

- QCR

Queensland cancer registry

- QLD

Queensland

- RA

Residential area

- RT

Radiotherapy

Author contributions

SAB led the conceptualisation, design, and planning of the study, conducted the data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. GG and ML contributed to the study’s conceptualisation, design, and supervision. JC offered critical feedback on the manuscript. All authors participated in data interpretation, and revision of the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) funded Centre of Research Excellence (CRE) in Targeted Approaches to Improve Cancer Services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians (TACTICS; #1153027). JC was funded by an NHMRC Research Fellowship (#1058244). GG was funded by a NHMRC Investigator Grant (#2034453). The funders had no direct or indirect role in the conception of the study design, data synthesis and interpretation, or manuscript writing.

Data availability

The datasets utilised in the present study are not accessible to the public because of privacy constraints outlined in our ethics approval, which explicitly prohibits data sharing. The corresponding author had complete access to all the data and bore the final responsibility to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval was obtained from the following Human Research Ethics Committees (HRECs): Townsville Hospital and Health Service (HREC/16/QTHS/110); Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (EO2017/1/343); James Cook University (H6678); and The University of Queensland (2022/HE002538: 23/01/2023). Queensland Health waived the requirement for individual consent under the Public Health Act 2005. No identifiable information was disclosed to the study team.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer data in Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Apr. 20]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-data-in-australia.

- 2.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in aboriginal & Torres strait islander people of Australia. (2018). Canberra: AIHW. [Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-in-indigenous-australians/contents/table-of-contents]

- 3.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia 2021. Canberra: AIHW. 2021. [Available from: 10.25816/ye05-nm50]

- 4.Queensland Health. 2024, Achieving health equity in cancer care with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Queenslanders.

- 5.Anderson K, Diaz A, Parikh DR, Garvey G. Accessibility of cancer treatment services for Indigenous Australians in the Northern territory: perspectives of patients and care providers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilroy J, Henningham M, Meehan D, Nila F, McGlone J, McAtamney A, et al. Systematic review of aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ experiences and supportive care needs associated with cancer. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore SP, Green AC, Bray F, Garvey G, Coory M, Martin J, et al. Survival disparities in Australia: an analysis of patterns of care and comorbidities among Indigenous and non-indigenous cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis M. Radiation oncology areas of need: Cancer incidence projections 2014–2024. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2014.

- 9.Beardmore RMC, Rizvi F, Hillen J. Shining a light: Radiotherapy cancer treatment in Australia 2022.

- 10.Radiation Oncology Tripartite Committee. Planning for the best: tripartite National strategic plan for radiation oncology 2012–2022. Sydney: The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shukla N, Wickramasuriya R, Miller A, Perez P. An approach to plan and evaluate the location of radiotherapy services and its application in the new South Wales, Australia. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2015;122(2):245–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Understanding Radiation Therapy. A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends. Cancer Council 2021 [Available from: https://www.cancer.org.au/assets/pdf/understanding-radiation-therapy-booklet

- 13.Barton MB, Jacob S, Shafiq J, Wong K, Thompson SR, Hanna TP, et al. Estimating the demand for radiotherapy from the evidence: a review of changes from 2003 to 2012. Radiother Oncol. 2014;112(1):140–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong K, Delaney GP, Barton MB. Evidence-based optimal number of radiotherapy fractions for cancer: a useful tool to estimate radiotherapy demand. Radiother Oncol. 2016;119(1):145–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ROHPG. Radiation Oncology Health Program Grants (ROHPG) Scheme. 2020 review report 2021 [Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/05/radiation-oncology-health-program-grants-rohpg-scheme-2020-review-report-rohpg-scheme-2020-review-report.pdf]

- 16.Chen HHW, Kuo MT. Improving radiotherapy in cancer treatment: promises and challenges. Oncotarget. 2017;8(37):62742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scotland NHS. Cancer in Scotland– Radiotherapy Activity Planning for Scotland 2011–2015 [Available from: https://webarchive.nrscotland.gov.uk/20170717082622/http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2006/01/24131719/28]

- 18.Barton MB, Jacob S, Wong KHW. Review of optimal radiotherapy utilisation rates: Collaboration for cancer outcomes research and evaluation. Australian Government. 2013 Mar. 2013.

- 19.Butler SM. Changes to radiotherapy utilisation in Western NSW after the opening of a local service. J Med Radiat Sci. 2017;64(4):251–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Royal Australian. and New Zealand College of Radiologists Submission to Australian Cancer Plan 2023–2033 Consultation. 2022.

- 21.Gabriel G, Barton M, Delaney GP. The effect of travel distance on radiotherapy utilization in NSW and ACT. Radiother Oncol. 2015;117(2):386–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackenzie P, Vajdic C, Delaney G, Gabriel G, Agar M, Comans T, et al. Factors affecting radiotherapy utilisation in geriatric oncology patients in NSW, Australia. Tech Innovations Patient Support Radiation Oncol. 2020;16:17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merie R, Gabriel G, Shafiq J, Vinod S, Barton M, Delaney GP. Radiotherapy underutilisation and its impact on local control and survival in new South Wales, Australia. Radiother Oncol. 2019;141:41–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ong WL, Finn N, Te Marvelde L, Hornby C, Milne RL, Hanna GG, et al. Disparities in radiation therapy utilization for cancer patients in Victoria. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2022;66(6):830–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitzadam S, Lin E, Creighton N, Currow DC. Lung, breast and bowel cancer treatment for aboriginal people in new South Wales: a population-based cohort study. Intern Med J. 2021;51(6):879–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Queensland Government. Radiation oncology in Queensland, indicators of safe, quality cancer care delivered by public and private services, 2009–2018. Brisbane: Queensland Health. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banham D, Roder D, Eckert M, Howard NJ, Canuto K, Brown A, et al. Cancer treatment and the risk of cancer death among aboriginal and non-Aboriginal South Australians: analysis of a matched cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coory MD, Green AC, Stirling J, Valery PC. Survival of Indigenous and non-indigenous Queenslanders after a diagnosis of lung cancer: a matched cohort study. Med J Aust. 2008;188(10):562–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valery PC, Coory M, Stirling J, Green AC. Cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survival in Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians: a matched cohort study. Lancet. 2006;367(9525):1842–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bates N, Callander E, Lindsay D, Watt K. CancerCostMod: a model of the healthcare expenditure, patient resource use, and patient co-payment costs for Australian cancer patients. Health Econ Rev. 2018;8(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Callander E, Topp SM, Larkins S, Sabesan S, Bates N. Quantifying Queensland patients with cancer health service usage and costs: study protocol. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e014030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindsay D, Bates N, Diaz A, Watt K, Callander E. Quantifying the hospital and emergency department costs for women diagnosed with breast cancer in Queensland. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(3). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Lindsay D, Callander E. Quantifying the costs to different funders over Five-Years for women diagnosed with breast Cancer in Queensland, Australia: A data linkage study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(24):12918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Cancer Control Indicators. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identification in national cancer data. https://ncci.canceraustralia.gov.au/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-identification-national-cancer-data.

- 35.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Procedures data cubes. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Apr. 29]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/hospitals/procedures-data-cubes.

- 36.MBS Online. Medicare benefits schedule. Radiation oncology. cfm?type=item&q=15103&qt=ItemID. 2024. https://www9.health.gov.au/mbs/fullDisplay

- 37.Burmeister BH, Zarate DD, Burmeister EA, Harden HE, Colquist SP, Cossio DL, et al. Lung cancer patients in Queensland suffer delays in receiving radiation therapy–but not as a result of distance. Intern Med J. 2010;40(2):126–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia. Canberra: ABS. 2021 [cited 2024 December 19]. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/socio-economic-indexes-areas-seifa-australia/latest-release.

- 39.Baade PD, Turrell G, Aitken JF. Geographic remoteness, area-level socio-economic disadvantage and advanced breast cancer: a cross-sectional, multilevel study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(11):1037–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & National Indigenous Australians Agency. Measure 1.08 Cancer, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework website. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & National Indigenous Australians Agency. 2023 [cited 20 December 2024]. Available from: https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/1-08-cancer.

- 41.Cunningham J, Rumbold AR, Zhang X, Condon JR. Incidence, aetiology, and outcomes of cancer in Indigenous peoples in Australia. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(6):585–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bartlett JG, Sanguins J, Carter S, Turner D, Demers A, Kliewer E, Mehta P, Hoeppner N, Musto G, Morgan B. Cancer and related health care utilization in the Manitoba Metis population. Winnipeg, MB: Manitoba Metis Federation. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seneviratne S, Campbell I, Scott N, Lawrenson R. A cohort study of ethnic differences in use of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for breast cancer in new Zealand. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheppard AJ, Chiarelli AM, Marrett LD, Nishri ED, Trudeau ME. Stage at diagnosis and comorbidity influence breast cancer survival in first nations women in Ontario. Can Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(10):2160–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.The Cancer Quality Council of Ontario, Cancer System Quality Index (CSQI). 2017 Available from: https://www.csqi.on.ca/en/indicators/access-radiation-treatment.

- 46.England NHS, Commissioning Board NHS. 2013Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/b01-radiotherapy.pdf.

- 47.Barton MB, Delaney GP. A decade of investment in radiotherapy in new South Wales: why does the gap between optimal and actual persist? J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2011;55(4):433–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pan HY, Haffty BG, Falit BP, Buchholz TA, Wilson LD, Hahn SM, et al. Supply and demand for radiation oncology in the united States: updated projections for 2015 to 2025. Int J Radiation Oncology* Biology* Phys. 2016;96(3):493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yap ML, O’Connell DL, Goldsbury DE, Weber MF, Barton MB. Actual versus optimal radiotherapy utilisation for metastatic Cancer patients in the 45 and up study cohort, new South Wales. Clin Oncol. 2021;33(10):650–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen Z, King W, Pearcey R, Kerba M, Mackillop WJ. The relationship between waiting time for radiotherapy and clinical outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Radiother Oncol. 2008;87(1):3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mackillop WJ. Killing time: the consequences of delays in radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2007;84(1):1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barton MB, Allen S, Delaney GP, Hudson HM, Hao Z, Allison RW, et al. Patterns of retreatment by radiotherapy. Clin Oncol. 2014;26(10):611–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khor R, Bressel M, Tai KH, Ball D, Duchesne G, Rose W, et al. Patterns of retreatment with radiotherapy in a large academic centre. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2013;57(5):610–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Radiotherapy in Australia 2018–19. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2020 [cited 2024 Apr. 29]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/radiotherapy/radiotherapy-in-australia-2018-19.

- 55.Halkett GKB, McKay J, Hegney DG, Breen LJ, Berg M, Ebert MA, et al. Radiation therapists’ and radiation oncology medical physicists’ perceptions of work and the working environment in Australia: a qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care. 2017;26(5):e12511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan J, Griffiths K, Turner A, Tobias J, Clarmont W, Delaney G, et al. Radiation therapy and Indigenous peoples in Canada and Australia: Building paths toward reconciliation in Cancer care delivery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2023;116(2):421–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Campbell MA, Hunt J, Scrimgeour DJ, Davey M, Jones V. Contribution of aboriginal Community-Controlled health services to improving aboriginal health: an evidence review. Aust Health Rev. 2017;42(2):218–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Clifford A, McCalman J, Bainbridge R, Tsey K. Interventions to improve cultural competency in health care for Indigenous peoples of Australia, new Zealand, Canada and the USA: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;27(2):89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jongen C, McCalman J, Campbell S, Fagan R. Working well: strategies to strengthen the workforce of the Indigenous primary healthcare sector. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nolan-Isles D, Macniven R, Hunter K, Gwynn J, Lincoln M, Moir R, et al. Enablers and barriers to accessing healthcare services for aboriginal people in new South Wales, Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6):3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Quilty S, Wood L, Scrimgeour S, Shannon G, Sherman E, Lake B, et al. Addressing profound disadvantages to improve Indigenous health and reduce hospitalisation: a collaborative community program in remote Northern territory. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22):4306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cultural safety in health care for Indigenous Australians: monitoring framework. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Apr. 29]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-australians/cultural-safety-health-care-framework.

- 63.Naidoo T, Chamunyonga C, Burbery J, Rutledge P. Cultural safety in radiation therapy education: identifying knowledge deficits to improve Indigenous health practice. J Med Radiat Sci. 2024;8. 10.1002/jmrs.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Summers A. Closing the gap in Indigenous Australian cancer care: initiatives to foster cultural safety and improve access to radiation therapy. J Med Imaging Radiation Sci. 2023;54(4):S38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee B, Gately L, Lok SW, Tran B, Lee M, Wong R, et al. Leveraging comprehensive cancer registry data to enable a broad range of research, audit and patient support activities. Cancers. 2022;14(17):4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ramsey I, Corsini N, Hutchinson A, Marker J, Eckert M. Challenges and opportunities for using population health data to investigate cancer survivors’ quality of life in Australia. Qual Life Res. 2022;31(10):2977–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.National Cancer Control Indicators. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cancer Control Indicators. Radiotherapy waiting times. https://ncci.canceraustralia.gov.au/treatment-and-support/treatment/radiotherapy-waiting-times.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Table S1: Radiotherapy commencement at different time points after cancer diagnosis in QLD, 1 July 2011 and 30 June 2015 (N = 30, 329).

Supplementary Material 2: Table S2: The distribution of different types of radiotherapy across socio-demographic characteristics of patients diagnosed with cancer in QLD, 1 July 2011 and 30 June 2015 (n = 30, 268).

Supplementary Material 3: Table S3: Stratification analysis by cancer type (top 12 cancers in First Nations Peoples) to examine the radiotherapy among First Nations compared to other Queenslanders with a cancer diagnosis, 1st July 2011-30th June 2015.

Supplementary Material 4: Fig. S1: Stratification analysis for selected cancer types (number of cases at least 100 for First Nations Peoples) to examine the radiotherapy among First Nations compared to other Queenslanders with a cancer diagnosis, 1st July 2011-30th June 2015.

Supplementary Material 5: Fig. S2: Average waiting time in days among First Nations and other Queenslanders with a cancer diagnosis in QLD, 1 July 2011 and 30 June 2015

Data Availability Statement

The datasets utilised in the present study are not accessible to the public because of privacy constraints outlined in our ethics approval, which explicitly prohibits data sharing. The corresponding author had complete access to all the data and bore the final responsibility to submit the manuscript for publication.