Abstract

Background

Methamphetamine (METH) is a widely abused neurotoxic substance that can lead to neurocognitive disabilities. Recent studies have shown that memantine (MEM), an NMDA receptor antagonist, can improve cognitive function across various disorders. Given that previous studies have revealed that exposure to METH leads to several social and cognitive impairments, this research aimed to investigate the effects of MEM on social memory, social behavior, and novel object recognition impairments caused by chronic METH exposure. Adult male Wistar rats received a regimen of METH, which causes neurotoxicity (four injections of 6 mg/kg, s.c., at 2-h intervals). After one week, the effects of MEM (5 mg/kg, i.p.) on novel object recognition memory and social behaviors in the experimental groups were examined.

Results

Animals exposed to the METH regimen exhibited significant impairments in the acquisition, consolidation, and retrieval stages of novel object recognition memory. However, treatment with MEM ameliorated the detrimental effects of METH on the acquisition, consolidation, and retrieval, but not the reconsolidation, of novel object recognition memory. Additionally, the results revealed that METH-triggered deficits in social interaction and behavior were improved by MEM treatment.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that MEM administration effectively ameliorated memory impairments induced by chronic METH exposure. These findings provide valuable insights into the neuroprotective effects of MEM on novel object memory, social memory, and social behaviors.

Keywords: Methamphetamine, Novel object recognition memory, Social interaction, Memantine, Social memory

Background

Methamphetamine (METH) is a harmful psychostimulant classified as a prohibited substance because of its potential for abuse and detrimental effects on the brain [1, 2]. Chronic METH abuse can lead to long-term brain damage that eventually causes deficits in cognitive performance [3–5]. METH-induced neurotoxicity primarily affects the dopamine system, which plays crucial roles in motivation, reward, and pleasure. However, chronic METH abuse can impair both short-term and long-term cognitive functions such as attention, decision-making, and memory [2, 6]. A growing body of literature has demonstrated that exposing rodents to a neurotoxic dose of METH decreases their ability to recognize novel objects in a novel object recognition (NOR) test [7, 8]. METH administration also causes social behavior impairments, which may underlie certain avoidant signs or adverse cognitions and can be associated with impaired behavioral flexibility [9]. Moreover, recent evidence suggests that cognitive impairments resulting from METH abuse are associated with neurotoxicity and neuronal death in dopaminergic cells, particularly in the hippocampus [10]. Recent studies have revealed that memory impairment caused by METH is associated with a decrease in the binding of NMDA receptor ligands, especially in the hippocampus [11, 12]. Despite extensive research, the specific cellular and molecular mechanisms involved remain unclear. The glutamatergic N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor plays a crucial role in memory and learning ability, and it has been proposed that impaired signaling of these receptors may contribute to METH-induced memory dysfunctions. Memantine (MEM), a noncompetitive antagonist of the NMDA receptor, is widely used to treat dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, and can improve cognitive function and prevent cell death following METH exposure [13]. Nevertheless, there is some controversy about the effectiveness of MEM, as recent animal studies have demonstrated that it may not improve cognitive ability or could even exacerbate impairments [14, 15].

A substantial body of research has shown that METH impairs a wide variety of cognitive functions, including social behavior and recognition memory. It has been proposed that the MEM influences cognitive function and behavior. Importantly, various neurobiological processes are responsible for different stages of memory [16, 17]. Our earlier research demonstrated that METH administration has detrimental effects on different memory stages, including acquisition, consolidation and retrieval of recognition memory, and social memory, in male rodents [18]. Nonetheless, the impact of the MEM on various stages of NOR and social memory remains unclear. Therefore, given the limited research on the function of the MEM as an antagonist of the NMDA receptor in addressing deficits in social and recognition memory caused by METH, the aim of the current study was to determine whether pretreatment with the MEM could counteract the noxious effects of METH on various phases of NOR, social memory, and social behavior.

Materials and methods

Animals

For the experiments, 96 adult male Wistar rats weighing between 200 and 250 g were obtained from the Institute of Laboratory Animal Care at Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences (8 animals in each group). Only male rats were used to avoid potential confounding effects of hormonal fluctuations in females, which can influence behavioral outcomes. During the experiments, the rats were kept in Plexiglas cages with a 12-h light/dark cycle under consistent humidity (50 ± 4%) and temperature (23 ± 2 °C). The animals were socially housed to mimic natural social interactions, which is important for assessing social behaviors. Every effort was made to minimize the number of animals used in this study. Moreover, although anesthesia was not required for the experimental procedures, euthanasia of the animals was performed using CO2 gas in a designated chamber for this purpose. All procedures in this study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences for laboratory animals (Grant No: 3146).

Chemicals and experimental protocols

METH hydrochloride was obtained from Sigma Aldrich (CAS 537-46-2 ,St. Louis, MO, USA) and dissolved in 0.9% physiological saline for subcutaneous injections. The NMDA antagonist MEM was acquired from Sigma Aldrich (CAS 19982-08-2, St. Louis, MO, USA) and dissolved in 0.9% physiological saline for i.p. injection. The male rats were randomly assigned to 12 experimental groups in this study. The animals were first divided into four primary treatment categories: (1) Control group received saline (four at 2-hour intervals); (2) METH group received methamphetamine (6 mg/kg, four subcutaneous injections at 2-hour intervals); (3) MEM intervention groups; and (4) METH + MEM intervention groups. Each primary category contained multiple subgroups for different testing phases. Seven days post-injections, eight animals from each primary category (n = 32 total) underwent social interaction testing as complete groups. For NOR testing, the remaining animals were divided into specialized subgroups (n = 8 per subgroup) that received memantine (5 mg/kg, i.p.) at specific time points relative to memory phases: acquisition (1 h pre-sample), consolidation (immediately post-sample), retrieval (1 h pre-test), and reconsolidation (post-second sample). This comprehensive design enabled simultaneous assessment of social behavior in intact groups while precisely examining phase-specific memory effects during NOR testing across all experimental conditions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comprehensive experimental group structure for both social and NOR tests

| Group Type | Social Test | NOR Test | Pretreatment | MEM in NOR Test | NOR Phase Specifics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ✓ Full test | ✓ Full protocol | Saline (4× s.c.) | None | N/A |

| METH-only | ✓ Full test | ✓ Full protocol | METH (6 mg/kg) | None | N/A |

| MEM Groups | |||||

| ∙ Base | ✓ Full test | Not tested | None | None | N/A |

| ∙ Acquisition | Not tested | ✓ Tested | None | 1 h pre-sample | Acquisition |

| ∙ Consolidation | Not tested | ✓ Tested | None | Post-sample | Consolidation |

| ∙ Retrieval | Not tested | ✓ Tested | None | 1 h pre-test | Retrieval |

| ∙ Reconsolidation | Not tested | ✓ Tested | None | Post-2nd sample | Reconsolidation |

| METH + MEM Groups | |||||

| ∙ Base | ✓ Full test | Not tested | METH (6 mg/kg) | None | N/A |

| ∙ Acquisition | Not tested | ✓ Tested | METH (6 mg/kg) | 1 h pre-sample | Acquisition |

| ∙ Consolidation | Not tested | ✓ Tested | METH (6 mg/kg) | Post-sample | Consolidation |

| ∙ Retrieval | Not tested | ✓ Tested | METH (6 mg/kg) | 1 h pre-test | Retrieval |

| ∙ Reconsolidation | Not tested | ✓ Tested | METH (6 mg/kg) | Post-2nd sample | Reconsolidation |

Novel object recognition memory

The NOR task is a hippocampus-dependent memory model that relies on the natural inclination of an animal to explore novelty. In the NOR test, in a familiar environment, the rodents remembered which object they had previously encountered among the two options. The exploratory task was performed via an open-field device that consisted of a square floor area (40 × 40 cm) enclosed by 30-cm high walls made of clear Plexiglas. The behavior of the animals was monitored via a video tracking system set up at the center and above the maze. One hour prior to the test, the rodents were transferred from the colony area to the observation area. The objects were selected in different shapes and sizes (from 7 × 7 × 7 cm to 12 × 12 × 12 cm) to prevent the animals from displacing them [26, 30]. The NOR task consisted of one or two example stages, followed by a one-day delay and a test stage, as previously explained in our research [30]. To minimize the effect of circadian rhythm on activity and evaluate long-term memory retrieval, the test stage was conducted one day (24 h) after the sample stage. In the beginning, the rodents were accustomed to the vacant device for 10–15 min and were permitted to explore it freely for three consecutive days. The animals were subjected to the sample stage the day after the final habituation day (Fig. 1). The sample stage involved the rats exploring two identical objects (A1 and A2), and they were given the opportunity to investigate them for 5 min. After a 24-h delay, the test stage was conducted to examine the rats’ response to two objects for 5 min—one being a third copy of the original objects (A3) and the other being a novel object (B). (Figs. 2A, 3A, and 4A).

Fig. 1.

Timeline of the experimental protocol of the study. METH, methamphetamine (four injections of 6 mg/kg, s.c., at 2-h intervals); D, day

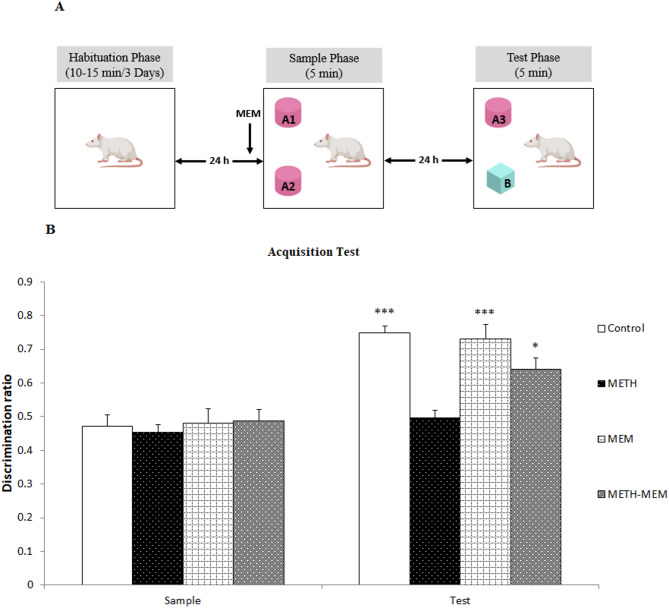

Fig. 2.

Effects of memantine on the acquisition of recognition memory in METH-exposed rats. (A) Schematic representation of the acquisition task. (B) Test phase of the acquisition experiment. The dashed line represents the discrimination ratio of 0.5, which indicates exploration by chance. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 compared with the chance level (DR = 0.5). #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 compared with the test phase of the corresponding control group. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E.M.s (n = 8 rats in each group). A1, A2, and A3 represent familiar objects, and B represents the novel object. METH, methamphetamine; MEM, memantine

Fig. 3.

Effects of memantine on the consolidation of recognition memory in METH-exposed rats. (A) Schematic representation of the consolidation task. (B) Test phase of the consolidation experiment. The dashed line represents the discrimination ratio of 0.5, which indicates exploration by chance. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 compared with the chance level (DR = 0.5). #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 compared with the test phase of the corresponding control group. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E.M.s (n = 8 rats in each group). A1, A2, and A3 represent familiar objects, and B represents the novel object. METH, methamphetamine, MEM, memantine

Fig. 4.

Effects of memantine on the retrieval of recognition memory in METH-exposed rats. (A) Schematic representation of the retrieval task. (B) Test phase of the retrieval experiment. The dashed line represents the discrimination ratio of 0.5, which indicates exploration by chance. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 compared with the chance level (DR = 0.5). #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 compared with the test phase of the corresponding control group. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E.M.s (n = 8 rats in each group). A1, A2, and A3 represent familiar objects, and B represents the novel object. METH, methamphetamine; MEM, memantine

Moreover, the reconsolidation test comprised two sample stages that were separated by 24 h. In the second sample stage, the rodents were subjected to familiar objects. (A3 and A4; Fig. 5A). In the test phase, which was conducted 24 h later, the rats were acquainted with a familiar (A5) or novel (B) object (Fig. 5A). The objects’ positions and roles were evenly distributed among both the groups and the animals. The rats typically spent more time investigating unfamiliar objects. The criteria for object exploration involved interacting with or examining objects from a distance of less than 2 cm, whereas behavior was not considered exploration if an animal was merely chewing, spinning, or sitting on the objects [19].

Fig. 5.

Effects of memantine on the reconsolidation of recognition memory in METH-exposed rats. (A) Schematic representation of the reconsolidation task. (B) Test phase of the reconsolidation experiment. The dashed line represents the discrimination ratio of 0.5, which indicates exploration by chance. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 compared with the chance level (DR = 0.5). #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 compared with the test phase of the corresponding control group. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E.M.s (n = 8 rats in each group). A1, A2, A3, A4, and A5 represent familiar objects, and B represents the novel object. METH, methamphetamine; MEM, memantine

Effects of memantine on different phases of NOR memory

As previously mentioned, the NOR test consisted of a habituation stage (days 1‒3), a sample stage (day 4), and a test stage (day 5; after a 24-h delay). The rats were given a neurotoxic METH regimen (6 mg/kg, at 2-h intervals), saline, or MEM (1 mg/kg, i.p.), and after one week, the animals in the different groups were subjected to acquisition, consolidation, retrieval, and reconsolidation tasks. During the acquisition phase (Fig. 2A), the rats were given either saline or MEM one hour before the sample stage. For consolidation (Fig. 3A), immediately after the sample stage, the interventions were administered, whereas for retrieval (Fig. 4A), they were given one hour prior to the test stage. In the reconsolidation phase (Fig. 5A), the interventions were administered immediately after the second sample phase [18].

Social interaction

The social memory test was performed in different groups via a device for social engagement. The social task comprised a PVC structure (polyvinyl chloride) with three cavities measuring 40 × 25 × 40 cm. The cavities were separated by sliding doors that examined the desire and tendency for social contact and new social interactions. The wire cages in both the left and right chambers were empty and black (Galaxy Pencil/Utility Cup Spectrum Diversified Designs, Inc., Streetsboro, OH) and were placed upside down. The behavior of the rats during the experiment was captured via a camera positioned over the device. The experiment consisted of three 10-minute stages.

During the habituation phase, both sides of the social memory apparatus contained empty wire cages. The animal was positioned in the central compartment for a duration of 10 min when all the doors were closed. The animal was then permitted to investigate all the compartments while the doors were opened. The time spent investigating each wire cage in the chambers was recorded. After the habituation phase, a new rat, named “Stranger 1”, was positioned inside a cage, and the test rat was located in the middle compartment and allowed to investigate the rooms for another 10 min (sociability stage, Fig. 6). In the social novelty stage, the test animal was returned to the center room. Along with Stranger 1, a novel unknown rat named “Stranger 2” was located in another empty cage. The retractable doors between the rooms were removed, and all factors were reassessed for an additional 10 min. Importantly, the Stranger 1 and Stranger 2 rats were the same sex and weight, were housed under the same conditions, and did not have prior interactions with the treated rats [20].

Fig. 6.

Effects of memantine on the sociability phase in the social interaction experiment in METH-exposed rats. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 compared with the time spent exploring the empty cage (in the same group). #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 compared with the time spent exploring stranger 1 in the METH group. METH, methamphetamine; MEM, memantine

Social behavior test (SBT)

Two unfamiliar rats from a separate cage (from the same treatment) were chosen for the social behavior test while under the same treatment and weight conditions. The mutual behavior of the rats was observed and recorded over 5 min in an open field arena measuring 50 cm × 50 cm × 30 cm. After the test, the total number and duration of social interactions, as well as the number and duration of locomotion and rearing, were recorded. The analyzed measures consisted of active social interaction patterns such as mutual sniffing, genital investigation, following, climbing over, crawling under, and allogrooming. Additionally, nonsocial behaviors, including rearing and locomotion, were also measured. Notably, the rats were habituated individually in the open field arena for 10 min 2 days prior to the SBT. For statistical analysis, the total number and total duration spent on specific behaviors were utilized during the experiment [21].

Statistical analysis

The discrimination ratio (DR) was computed as a measure of the inclination toward the unfamiliar item. A DR of 0.5 indicates equal time for exploration of both the familiar and novel items, suggesting that the investigation occurred by chance. A DR greater than 0.5 (DR > 0.5) indicates a strong tendency for the novel item. The DR for the test stages was calculated by dividing the time spent exploring the novel item (T-B) by the total exploration time (T-A3 + T-B) or (T-A5 + T-B). In the sample phases, the DR was calculated by dividing the amount of time spent investigating the familiar item substituted with the novel item (throughout the test stage) by the overall time spent on the investigation: T-A2/(T-A1 + T-A2) or T-A4/(T-A3 + T-A4). To evaluate the DR for each group against the chance level/theoretical mean (DR = 0.5), a Student’s one-sample t test was utilized. The analyses of group differences for the sample and test stages were conducted via the independent samples t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s test. Moreover, one-way ANOVA was used to test differences in the duration and total number of specific types of social and nonsocial behaviors. The data are presented as the means ± SEMs. The threshold for statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Object recognition

Examining the results from the sample stages across the four memory phases (acquisition, consolidation, retrieval, and reconsolidation), the experiments demonstrated that there was no notable variance between the groups and the chance level (DR ≤ 0.5). Furthermore, during the sample stages, there were no notable differences between the groups across all the memory phases (p > 0.05). Nonetheless, for the test stages, there were differences among the groups. In all the experiments (acquisition, consolidation, retrieval, and reconsolidation), the DR for the test stages of both the control and MEM groups was greater than the level of chance (p < 0.001). Further analysis revealed that, compared with the control, the neurotoxic METH regimen impaired the acquisition, consolidation, retrieval, and reconsolidation of recognition memory. (p < 0.01; Figs. 2B, 3B and 4B, and 5B). Thus, for acquisition, consolidation, retrieval, and reconsolidation, compared with the vehicle (saline), the METH regimen reduced the DR. In addition, compared with METH treatment, MEM injection in animals in the METH group (METH + MEM group) increased the DR. The utilization of MEM indeed ameliorated the METH-induced impairments in the acquisition (p < 0.05), consolidation (p < 0.01), and retrieval (p < 0.01) of items, as validated by a notable increase in the preference index in comparison to the level of chance during every experiment (Figs. 2B, 3B, and 4B).

However, MEM had no notable effect on the reconsolidation test results (p > 0.05). The utilization of METH indeed reduced DR in comparison with the use of saline in the reconsolidation test; however, compared with METH, MEM administration in animals exposed to METH did not have any effect on DR. Indeed, MEM had no effect on the exploration index for the reconsolidation test in the METH + MEM group and did not demonstrate notable variance from the level of chance (Fig. 5B).

Social interaction

As demonstrated in Figs. 6 and 7, the results obtained during the sociability stage revealed that in the control and MEM groups, the amount of time spent in proximity to the Stranger 1 cage significantly increased compared with that spent in the empty cage (p < 0.001). Moreover, during the sociability stage, the results from the METH group indicated that the amount of time spent near the stranger 1 cage did not differ significantly from that spent by the empty cage. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 6, compared with METH treatment, MEM administration to animals exposed to METH partially increased the amount of time spent near Stranger 1 (p < 0.05). For Stranger 2, during the social novelty stage, the analysis revealed that the control and MEM groups spent significantly more time in proximity to the wire cage with Stranger 2 than with Stranger 1 (p < 0.001). In contrast, in METH group the amount of time spent near the wire cage with Stranger 1 was not notably different from that spent in the cage with Stranger 2. Moreover, compared with the wire cage with Stranger 1, the MEM treatment in animals exposed to METH (MEM + METH group) led to increased proximity to Stranger 2 (p < 0.05).

Fig. 7.

Effects of memantine on the social novelty phase in the social interaction experiment in METH-exposed rats. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 compared with the time spent exploring stranger 1 (in the same group). #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 compared with the time spent exploring stranger 2 in the METH group. METH, methamphetamine; MEM, memantine

Social behavior test

The total time spent on social behaviors (SBs), as well as the total number of all types of SBs (Table 2), decreased in the METH groups compared with the control groups (p < 0.001) (Table 2; Fig. 8). Additionally, with respect to climbing, genital investigation, and crawling, the time spent and the number of occurrences were lower in the METH groups than in the control group (p < 0.001) (Table 2; Fig. 8A, B, D, E). However, the time and number of sniffing did not differ between the METH-exposed animals and the control animals (p > 0.05) (Table 2; Fig. 8C). Further analysis revealed that exposure to METH led to changes in nonsocial behavior, as shown in Fig. 8F, G ; Table 1. METH injections increased the time spent and the number of locomotion and rearing behaviors relative to those in the control group. Moreover, one-way ANOVA indicated that the total time spent on SB, as well as the total number of all types of SB, was greater in METH + MEM-treated rats than in METH-treated rats (Table 2; Fig. 8A, B, D, E). In climbing, genital investigation, and crawling, the time spent and the number of occurrences were shorter in METH + MEM-treated rats than in METH-treated rats (P < 0.05). However, sniffing did not differ between METH + MEM-treated rats and METH-treated rats (p > 0.05) (Table 2; Fig. 8C). Further analysis revealed that the time spent and the number of rearing but not locomotion behaviors were partially lower in METH + MEM-treated rats than in METH-treated rats (P < 0.05)(Table 2; Fig. 8C).

Table 2.

The effect of treatments on the total number of social behavior

| Groups | Control | METH | MEM | METH + MEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Following | 10.13 ± 0.69 | 2.08 ± 0.31 | 11.65 ± 0.80 | 5.14 ± 0.52 |

| Climbing | 3.58 ± 0.34 | 0.68 ± 0.11 | 4.08 ± 0.41 | 2.23 ± 0.22 |

| Sniffing | 4.08 ± 0.41 | 3.28 ± 0.38 | 4.39 ± 0.56 | 3.41 ± 0.41 |

| Genital investigation | 3.42 ± 0.25 | 0.11 ± 0.09 | 2.82 ± 0.33 | 2.17 ± 0.15 |

|

Crawling Social interaction–total |

2.9 ± 0.36 24.1 ± 1.37 |

0.62 ± 0.15 6.77 ± 0.74 |

2.1 ± 0.41 25.04 ± 1.42 |

1.68 ± 0.27 14.66 ± 1.19 |

Fig. 8.

The effects of memantine on the time spent following, climbing, performing genital investigations, sniffing, and crawling in METH-exposed rats. *p < 0.001, **p < 0.0001 compared with the control group; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 compared with the METH group

Discussion

Behavioral alterations due to methamphetamine exposure

In the present study, we investigated the impact of the MEM on the sociability and object recognition deficits induced by METH. The results revealed that a METH regimen causing neurotoxicity impaired the acquisition, consolidation, retrieval, and reconsolidation of NOR and weakened social interaction and novelty detection in social settings during the social memory test. On the other hand, MEM administration ameliorated the negative effects of METH on these cognitive processes. Moreover, in the social memory test, the MEM improved social interaction and novelty recognition in social settings impaired by METH.

METH is a powerful psychostimulant that causes neurotoxicity, resulting in various cognitive impairments. Although the adverse consequences of METH on cognitive functions have been extensively studied, less attention has been given to the use of neuroprotective drugs such as MEM for social memory deficits. Numerous studies have shown impairments in social memory following chronic METH exposure in both human and animal models. In this context, E. Manning et al. reported that in a three-chamber sociability test, chronic METH administration resulted in deficits in social recognition memory in male rats [22]. More recently, Ghazvini and colleagues reported that a METH regimen that causes neurotoxicity (four injections of 6 mg/kg, s.c., at 2 h intervals) led to impairments in the acquisition, consolidation, retrieval, and reconsolidation of NOR and in social interaction deficits in rats [23]. It should be mentioned that Future studies should consider incorporating the Object Location Task (OLT) to further investigate hippocampal-specific spatial memory impairments in METH-exposed animals, complementing our findings on non-spatial recognition memory.

In addition, the current findings showed that METH injections reduced performance in the social behavior test (SBT). Our results are in agreement with the work of others [25–28]. For example, Slamberová et al. [21] demonstrated that an acute dose of METH decreases performance in SBT in a dose-dependent manner. However, another study showed that SBT increased after the administration of a lower dose (1.25 mg/kg) and decreased after the administration of higher doses (2.5 and 5 mg/kg) of amphetamine [29]. However, the social behavior test involved pairing rats from the same treatment group, which precludes conclusions about interactions between rats from different treatment conditions (e.g., MEM vs. METH). Future studies could address this by incorporating cross-group interactions to better model heterogeneous social contexts. Moreover, as the anxiogenic effects of psychostimulants have been previously reported, our findings showed that exposure to METH leads to increased anxiety-like behavior.

Impact of memantine on methamphetamine -induced behavior deficits

Our results demonstrated that MEM administration effectively ameliorated the deficits in NOR memory and social memory caused by METH-induced neurotoxicity. In line with these findings, Camarasa et al. reported that prior administration of MEM (5 mg/kg, i.p.) restored the ability to differentiate between known and novel METH (10 mg/kg, s.c.) in male rats. However, in this study, they only assessed the impacts of MEM on the performance of NOR tests in METH-exposed rats. The precise processes underlying the effects of MEM on memory deficits induced by METH are not fully understood but may involve its pharmacological properties as an NMDA receptor antagonist. Memantine is proposed as a pre-treatment to prevent neurotoxicity induced by methamphetamine (METH). By blocking excessive glutamate activity, memantine protects neurons from excitotoxicity and oxidative stress, thereby mitigating cognitive and behavioral impairments. Consistent with our work, Camarasa et al. [30] reported that MEM partially decreased rearing behavior in MDMA-exposed rats. However, similar to other studies, our results showed that MEM administration to rats elicited a locomotor stimulant response that was maintained with METH injections [30, 31].

METH neurotoxicity and Memantine’s neurochemical modulation

The specific impact of METH on the neurotoxicity of social memory and novel object memory has not been extensively studied, but this effect may be attributed to its effects on neurotransmitter systems and brain regions involved in these cognitive processes. METH predominantly disrupts dopamine release and depletes dopaminergic neurons, which modulate reward processing, motivation, and learning processes crucial for social recognition and novelty detection. Moreover, considering that glutamate serves as the chief neurotransmitter that enhances the excitability of neurons involved in synaptic plasticity and memory formation, chronic exposure to METH can disrupt glutamatergic transmission, leading to excitotoxicity and oxidative stress [24]. In this point of view, METH induces excitotoxicity by overactivating NMDA receptors, leading to neuronal damage and impaired synaptic plasticity. This overactivation results in excessive calcium influx, oxidative stress, and ultimately, neuronal death. Memantine, as an NMDA receptor antagonist, blocks this excessive activation, thereby protecting neurons from excitotoxicity and preserving cognitive function [1].

MEM blocks open channels in a noncompetitive manner, which results in weak binding and fast separation from the channel, and can reduce the excessive activation of NMDA receptors without affecting their normal physiological activity [32, 33]. Thus, MEM likely blocks excessive activation of NMDA receptors, and by modulating glutamatergic neurotransmission, MEM may restore homeostasis in the glutamatergic system, which can be disrupted by chronic METH exposure. The antagonistic action of memantine on NMDA receptors may indirectly modulate dopamine signaling [34]. Excessive stimulation of NMDA receptors may result in increased dopamine release through various mechanisms [35]. By blocking this excessive activation, MEM may help restore normal dopamine release and alleviate the impairments in memory caused by METH-induced neurotoxicity. Furthermore, MEM has been shown to have neuroprotective effects by reducing excitotoxicity and oxidative stress and has also been found to enhance synaptic plasticity [36]. Chronic METH exposure is known to trigger oxidative stress and neuronal injury, which contribute to memory impairments [24]. By modulating glutamatergic transmission and reducing oxidative stress, MEM may protect against the neurotoxic effects of METH and preserve memory function. Future studies should explore molecular pathways, neurotransmitter interactions, and cellular mechanisms underlying MEM’s protection against METH-induced cognitive deficits and also addressing potential sex differences through inclusion of female subjects.

Conclusion

This study confirms METH’s detrimental effects on social and recognition memory, while demonstrating memantine’s ability to counteract these deficits through NMDA receptor modulation. The findings support MEM’s potential as a neuroprotective agent against METH-induced cognitive impairment, though further research is needed to explore its full therapeutic potential. However, the use of a pre-treatment limits the translatability of this study to clinical settings, where post-treatment interventions are more common. Future studies should investigate the efficacy of memantine as a post-treatment to enhance the clinical relevance of these findings.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Amirreza Tooni-firozkala for critical proofreading of the manuscript.

Author contributions

H.GH. and M.KH. conceived, designed and planned the experiments. H. GH and Y.A. carried out the experiments. M.K. and S.Z. contributed to the interpretation of the results. S.F. took the lead in writing the manuscript. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported financially by the Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran, (Grant NO:3146)

Data availability

The data will be made available upon request.

Declarations

Ethics and consent to participate

All procedures in this study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences for laboratory animals (Grant No: 3146).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ghazvini H, et al. Ovarian hormones prevent methamphetamine-induced anxiety-related behaviors and neuronal damage in ovariectomized rats. Neurosci Lett. 2021;746:135652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghalehnoei H, et al. Effects of Estrogen and progesterone on behavioral impairment and neuronal death in ovariectomized rats induced by methamphetamine. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2020;30(186):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krasnova IN, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine toxicity and messengers of death. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60(2):379–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mousavi T, et al. The effects of testosterone on cognitive function impairments and brain edema induced by methamphetamine in gonadectomized rats. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2024;34(232):12–24. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghazvini H, et al. Investigating facilitatory effects of Lithium on Methamphetamine-induced Spatial memory impairments in rat. Basic Clin Neurosci. 2023;14(5):605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizoguchi H, Yamada K. Methamphetamine use causes cognitive impairment and altered decision-making. Neurochem Int. 2019;124:106–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers J, De Santis S, See R. Extended methamphetamine self-administration enhances reinstatement of drug seeking and impairs novel object recognition in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2008;199:615–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamei H, et al. Repeated methamphetamine treatment impairs recognition memory through a failure of novelty-induced ERK1/2 activation in the prefrontal cortex of mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(1):75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janetsian SS, et al. Methamphetamine-induced deficits in social interaction are not observed following abstinence from single or repeated exposures. Behav Pharmacol. 2015;26(8 0 0):786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabrini S, et al. Methamphetamine induces neuronal death: evidence from rodent studies. Neurotoxicology. 2020;77:20–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee K-W, et al. Methamphetamine-sensitized mice are accompanied by memory impairment and reduction of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor ligand binding in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2011;178:101–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simoes P, et al. Methamphetamine induces alterations on hippocampal NMDA and AMPA receptor subunit levels and impairs Spatial working memory. Neuroscience. 2007;150(2):433–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipton SA. The molecular basis of memantine action in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurologic disorders: low-affinity, uncompetitive antagonism. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2005;2(2):155–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Creeley C, et al. Low doses of memantine disrupt memory in adult rats. J Neurosci. 2006;26(15):3923–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quan M-N, et al. Possible antidepressant effects and mechanisms of memantine in behaviors and synaptic plasticity of a depression rat model. Neuroscience. 2011;182:88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Preston AR, Eichenbaum H. Interplay of hippocampus and prefrontal cortex in memory. Curr Biol. 2013;23(17):R764–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sara SJ. Retrieval and reconsolidation: toward a neurobiology of remembering. Learn Mem. 2000;7(2):73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shahveisi K, et al. Novel object recognition memory in REM sleep-deprived rats: role of the cannabinoid CB(1) receptor. Behav Brain Res. 2020;381:112311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shahveisi K, et al. Role of cannabinoid CB1, receptor in object recognition memory impairment in chronically rapid eye movement Sleep-deprived rats. Chin Med Sci J. 2023;38(1):29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanavi MA, et al. Effects of clozapine and Risperidone antipsychotic drugs on the expression of CACNA1C and behavioral changes in rat ‘ketamine model of schizophrenia. Neurosci Lett. 2022;770:136354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Šlamberová R, et al. The effect of methamphetamine on social interaction of adult male rats. Behav Brain Res. 2010;214(2):423–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manning EE, van den Buuse M. Altered social cognition in male BDNF heterozygous mice and following chronic methamphetamine exposure. Behav Brain Res. 2016;305:181–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khodamoradi M, et al. Role of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor in methamphetamine-induced social and recognition memory impairment. Neurosci Lett. 2022;779:136634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cadet JL, Jayanthi S, Deng X. Speed kills: cellular and molecular bases of methamphetamine-induced nerve terminal degeneration and neuronal apoptosis. FASEB J. 2003;17(13):1775–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clemens KJ, et al. MDMA, methamphetamine and their combination: possible lessons for party drug users from recent preclinical research. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26(1):9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krsiak M. Effects of drugs on behavior of aggressive mice. Br J Pharmacol. 1979;65(3):525–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miczek KA, Tidey JW. Amphetamines: aggressive and social behavior. NIDA Res Monogr. 1989;94(1):68–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vanderschuren LJ, et al. Methylphenidate disrupts social play behavior in adolescent rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(12):2946–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tikal K, Benesova O. The effect of some psychotropic drugs on contact behavior in a group. Activitas Nervosa Superior. 1972;14(3):168–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camarasa J, et al. Memantine prevents the cognitive impairment induced by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;589(1–3):132–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.French E, et al. Effects of competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists on midbrain dopamine neurons: an electrophysiological and behavioral comparison to phencyclidine. Neuropharmacology. 1991;30(10):1039–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen HSV, Lipton SA. The chemical biology of clinically tolerated NMDA receptor antagonists. J Neurochem. 2006;97(6):1611–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schelterns P, Feldman H. Treatment of Alzheimer’s disease; current status and new perspectives. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2(9):539–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu Y-N, Johnson SW. Memantine selectively blocks extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in rat substantia Nigra dopamine neurons. Brain Res. 2015;1603:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newcomer JW, Krystal JH. NMDA receptor regulation of memory and behavior in humans. Hippocampus. 2001;11(5):529–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parsons CG, Stöffler A, Danysz W. Memantine: a NMDA receptor antagonist that improves memory by restoration of homeostasis in the glutamatergic system-too little activation is bad, too much is even worse. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53(6):699–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available upon request.