Abstract

The basal activity of Src family kinases is readily detectable throughout the cell cycle and increases by two- to fivefold upon acute stimulation of cells with growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor. Previous reports have demonstrated a requirement for Src activity for the G1/S and G2/M transitions. With a chimeric α-β PDGF receptor (PDGFR) expressed in fibroblasts, we have investigated the importance of the PDGF-mediated increase in Src activity at the G0/G1 transition for subsequent cell cycle events. A mutant PDGFR chimera that was not able to detectably associate with or activate Src was compromised in its ability to mediate tyrosine phosphorylation of receptor-associated signaling molecules and initiated a submaximal activation of Erk. In contrast to these early cell cycle events, later responses such as entry of cells into S phase and cell proliferation proceeded normally when Src activity did not increase following acute stimulation with PDGF. We conclude that the initial burst of Src activity is required for efficient tyrosine phosphorylation of receptor-associated proteins such as PLCγ, RasGAP, Shc, and SHP-2 and for maximal activation of Erk. Surprisingly, these events are not required for PDGF-dependent cell proliferation. Finally, later cell cycle events do not require that Src be activated at the G0/G1 transition and leave open the possibility that events such as the G1/S transition require the basal Src activity and/or activation of Src at later times in G1.

Several lines of evidence implicate the Src family members as playing an indispensable role in biology. Mice homozygous for a null allele of the src gene are deficient in osteoclast formation (29), and mice homozygous for deletion of a gene that encodes both Src and either of its close family members, Fyn or Yes, exhibit a high rate of neonatal lethality (30).

The importance of Src in platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-dependent cell cycle progression has recently been investigated. PDGF-dependent entry into the S phase could be largely eliminated when fibroblasts were microinjected with neutralizing antibodies or catalytically inactive forms of Src and Fyn or Src SH3 domain mutants (8, 31). By using a panel of Src mutants overexpressed in cells lacking endogenous Src, Broome and Hunter also identified Src’s SH3 domain as a key element in epidermal growth factor (EGF) or PDGF-dependent DNA synthesis (4). A requirement for Src was also shown for both EGF- and CSF-1-dependent initiation of DNA synthesis (25). In addition, Src activity is essential for mitosis. Src family members are phosphorylated by p34cdc2 during mitosis (21, 28), and microinjection of neutralizing antibodies to the Src family members late in the cell cycle G2-to-M prevent progression (24). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that Src is required for G1/S and G2/M transitions.

The studies described above clearly demonstrate a role for Src in the cell cycle, yet a number of important questions need to addressed. In a PDGF-stimulated cell, Src is activated minutes after exposure to PDGF, and it is possible that this initial burst of Src activity initiates other Src-dependent events occurring later in the cell cycle. Yet unlike basal Src activity, the initial burst of Src activity largely subsides after several hours (11). Surprisingly, injection of antibodies that neutralize the kinase activity of Src family members long after the initial burst of Src activity had receded to the basal level (6 h post-PDGF stimulation) was also able to prevent the majority of PDGF-dependent DNA synthesis (31). These observations suggest that basal Src activity and/or a second increase in Src activity late in G1 are essential for G1/S transition. Furthermore, since the half-life of the microinjected antibodies is thought to be long and because there is a Src activity-dependent step in mid-G1, the importance of Src activation at the G0/G1 transition was not addressed by the previous studies. Thus, the relative contribution of the initial increase in Src activity to subsequent cell cycle events in PDGF-stimulated cells remains an open question.

An alternative approach to study the importance of signaling enzymes in signal transduction cascades initiated by receptor tyrosine kinases is to use mutant receptors that selectively fail to activate a given signaling enzyme. Binding of Src to the PDGF β receptor (βPDGFR) requires two tyrosines in the receptor’s juxtamembrane domain (22). Unfortunately, mutant βPDGFRs in which these two tyrosines are substituted with phenylalanine have an impaired kinase activity when expressed in several different cell types (22, 32). In contrast, the αPDGFR will tolerate mutation of these two juxtamembrane tyrosines without a reduction in receptor kinase activity (10, 12). We have constructed a chimeric PDGFR in which the extracellular, transmembrane, and juxtamembrane domains are αPDGFR and the remainder of the intracellular portion is βPDGFR. When introduced into Ph cells, an NIH 3T3-like cell line that does not express the endogenous αPDGFR, the chimera could be selectively activated with PDGF-AA (6, 37). The chimeric PDGFR in Ph cells is a model system with which we can study the signaling pathways of the βPDGFR in a fibroblast. We have constructed an additional chimera (N2F72/74) in which the two juxtamembrane tyrosines required for Src binding have been mutated to phenylalanine. By comparing the signal relay events of the wild-type (N2WT) and the N2F72/74 receptors, we were able to assess the importance of the initial burst of Src kinase activity for PDGF-dependent signal relay and for initiating mitogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of chimeric PDGFRs.

The strategy to construct the chimeric receptor has been previously described (6). Briefly, a unique SacII site was introduced in the human αPDGFR at position 1972 just upstream of the kinase domain. The chimera was constructed by substituting the entire kinase, kinase insert, and tail of the αPDGFR with the corresponding portion of the human βPDGFR, which has a naturally occurring SacII site at the analogous position. The N2F72/74 chimera was constructed by subcloning a Not/SacII (5′ end of the αPDGFR up to and including the SacII site at position 1975) fragment of the F72/74 αPDGFR (10) into the Not/SacII-cut WT chimeric receptor. The chimeras were subcloned into the pLXSN2 retroviral vector (6, 20), virus was generated with the 293T system (16), and the resulting virus was used to infect Ph cells. Receptor-expressing cells were selected in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s (DME) medium plus 5% calf serum plus 1 mg of G418 per ml. Periodic assessment of the level of receptor expression by Western blot analysis indicated that the levels of expression were stable for at least 12 months.

Cell lines.

The Ph cell line was kindly provided by Dan Bowen-Pope and was obtained from Ph/Ph mice embryos, which are homozygous for a deletion that includes the αPDGFR gene. These cells do not express αPDGFR but do express normal levels (approximately 105 receptors/cell) of βPDGFR (3). They were maintained in DME medium supplemented with 5% calf serum. The Ph cells expressing the chimeric receptors were subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis with an antibody against the extracellular domain of the αPDGFR (PR292) followed by staining with an anti-mouse secondary antibody coupled to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) fluorescent dye. Both the N2WT and the N2F72/74 cell lines were sorted to obtain populations cells that were homogenous with respect to receptor expression. The level of the introduced chimera was comparable to the level of the endogenous βPDGFR in both cell types.

Antibodies.

PR292 is a mouse monoclonal antibody which recognizes an epitope in the extracellular domain of the αPDGFR. 80.8 is a crude rabbit polyclonal antiserum raised against a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein including a portion of the first immunoglobulin domain (residues 52 to 94). The Src-2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) used for immunoprecipitation of Src family members is an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against a peptide corresponding to amino acids 509 to 533 of c-Src. This antibody recognizes all Src family members expressed in fibroblasts (Src, Fyn, and Yes). The Src antibody used for Western blotting, 327, was a mouse monoclonal raised against the SH3 domain of c-Src and v-Src and is used at a 1:1,000 dilution (17). The immunoprecipitating antiphosphotyrosine antibody used in these studies is PY20, a monoclonal antibody commercially available from Transduction Labs. For anti-phosphotyrosine Western blot analysis, a combination of PY20 (Transduction Labs) and 4G10 (UBI) was used, each at a 1:1,000 dilution. PLCγ Western blot analysis was performed with a mixture of monoclonal PLCγ1 antibodies (UBI) at 0.25 μg/ml. SHP-2 was immunoprecipitated with a crude polyclonal rabbit serum (34.2) raised against a GST fusion protein that included the last 44 amino acids of the carboxyl terminus of human SHP-2 as previously described (15). To blot for SHP-2, a combination of 34.2 and anti-Syp (9) was used. RasGAP was immunoprecipitated with the previously described GAP antibody (33) and subjected to Western blot analysis as previously described (34). Shc was immunoprecipitated and blotted (at a 1:100 dilution) with a rabbit polyclonal antibody (UBI) raised against a recombinant fusion protein corresponding to amino acids 366 to 473 of Shc coupled to GST. The phospho-Erk antibody (New England Biolabs) is a rabbit polyclonal immunoglobulin G affinity-purified antibody raised against a synthetic phosphopeptide corresponding to amino acid residues 196 to 209 of human p44 Erk. It recognizes both the p42 and the p44 phosphorylated forms of Erk and is used at a 1:500 dilution.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis.

Subconfluent (85 to 90%) Ph cells were starved for 18 to 24 h in DME medium plus 0.1% calf serum and stimulated with 50 ng of PDGF-AA per ml for 5 min. The cells were washed and lysed in EB (13), and the chimeric receptors were immunoprecipitated with a mouse monoclonal antibody (PR292). The immunoprecipitates were bound to sorbin (formalin-fixed Staphylococcus aureus membranes) and washed as previously described (14). Src was immunoprecipitated from Ph cells, which were cultured and arrested as described above and stimulated with buffer (10 mM acetic acid plus 2 mg of bovine serum albumin [BSA]) or 50 ng of PDGF-AA for 5 min per ml. The cells were lysed in 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethyl-ammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) lysis buffer, i.e., 5 mM CHAPS in TBS (10 mM Tris base [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 2 mM sodium orthovanadate), and washed twice in CHAPS lysis buffer and twice in PAN (13). Src immunoprecipitates used for Src activation experiments were obtained from RIPA lysates (13), bound to sorbin, and washed twice in RIPA and twice in PAN.

To examine tyrosine phosphorylation of the receptor-associated proteins, Ph cells expressing the chimeric receptors were starved in DME medium plus 0.1% calf serum for 18 to 24 h. The cells were left resting or stimulated with 50 ng of PDGF-AA per ml for 5 min, washed, lysed in EB, and centrifuged as previously described (6). The various receptor-associated proteins were immunoprecipitated with the corresponding antibody, washed as previously described (34), and resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The resulting gel was transferred to Immobilon and probed first with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies, stripped, and reprobed with antibodies against the various proteins to determine the amount of protein immunoprecipitated. Proteins were detected with the ECL system (Amersham). The membranes were stripped by incubation of the membrane at 56°C for 1 h in 12.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.7)–100 mM 2-mercaptoethanol–2% SDS.

In vitro kinase assay.

Intrinsic tyrosine kinase activities of the PDGFR mutants were analyzed exactly as previously described (6). Receptor immunoprecipitates representing approximately 2 × 105 cells were incubated in the presence of 20 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES; pH 7.0)–10 mM MnCl2–20 μg of aprotinin per ml–10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP for 10 min at 30°C in the presence or absence of 0.5 μg of an exogenous substrate, GST-PLCγ, which included amino acid residues 550 to 850 of rat PLCγ. The reaction was stopped by adding an equal volume of 2× sample buffer (10 mM EDTA, 4% SDS, 5.6 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol, 200 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 1% bromophenol blue). The samples were incubated for 3 to 5 min at 95°C, centrifuged, and resolved by SDS-PAGE. The resulting gel was stained to ensure that equal amounts of the exogenous substrate were present in all samples, and the radiolabeled proteins were detected by autoradiography. To measure Src activity, the in vitro kinase assay was carried out as described above with Src immunoprecipitates representing 3 × 104 cells and 0.5 μg of acid-denatured rabbit muscle enolase (Boehringer Mannheim) as the exogenous substrate (5).

Cell proliferation.

Subconfluent cultures of Ph cells expressing the introduced chimeras were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), trypsinized briefly, resuspended in DME medium plus 1.0% plasma-derived serum (Cocalico Biologicals) and plated in triplicate at 1.25 × 105 cells per 6-cm dish. The cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 0.5 to 1.0 h, at which time buffer (10 mM acetic acid plus 2 mg of BSA per ml), PDGF-AA (25 ng/ml), or 10% calf serum was added to the cultures. The culture medium was replaced with fresh medium containing the indicated mitogens every 2 days, and the numbers of cells were quantitated daily with a hemacytometer until the cultures reached confluence.

Growth of cells in soft agar.

Soft agar growth was assayed as previously described (6).

[3H]thymidine uptake.

PDGF-stimulated [3H]thymidine uptake was assayed as follows. Cells were plated at 8 × 104 cells/ml in DME medium plus 5% calf serum in 24-well dishes and incubated at 37°C for 1.0 h, at which time they were washed twice in PBS and place in DME medium containing 0.1% calf serum. Cultures were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 48 h, at which time they were washed twice in PBS and incubated for an additional 48 h at 37°C in DME medium containing 2 mg of BSA per ml. Buffer (10 mM acetic acid and 2 mg of BSA ml), 50 ng of PDGF-AA per ml, or 50 ng of PDGF-BB per ml was added, the cultures were incubated for 18 to 20 h, the medium was replaced by DME medium plus 5% calf serum and 0.8 μCi of [3H]thymidine per ml, and the incubation was prolonged for 4 h. The peak of S phase in cells expressing the WT or F72/74 chimera stimulated with either serum or PDGF-AA started at 18 h and lasted for 6 to 8 h. Including 5% calf serum in the medium during the thymidine pulse did not alter the DNA synthesis response (data not shown). The cells were washed with ice-cold 5% trichloroacetic acid and lysed in 0.25 N NaOH, and the trichloroacetic acid precipitate was harvested and quantitated with a scintillation counter.

Erk activation.

Ph cells expressing the chimeric receptors were grown to 85 to 90% confluence, serum starved in DME medium plus 0.1% calf serum for 18 to 24 h, and left resting or stimulated with PDGF-AA for 5 min at 37°C. The cells were washed with H/S (13), lysed in EB (13) without BSA, and centrifuged to remove insoluble debris. The lysates were subjected to a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Pierce), and equal amounts of protein were resolved on an SDS-10% PAGE gel. The resolved proteins were subjected to phosphoErk and RasGAP Western blot analysis as described above.

RESULTS

Construction of the WT and F72/74 chimeric PDGFRs.

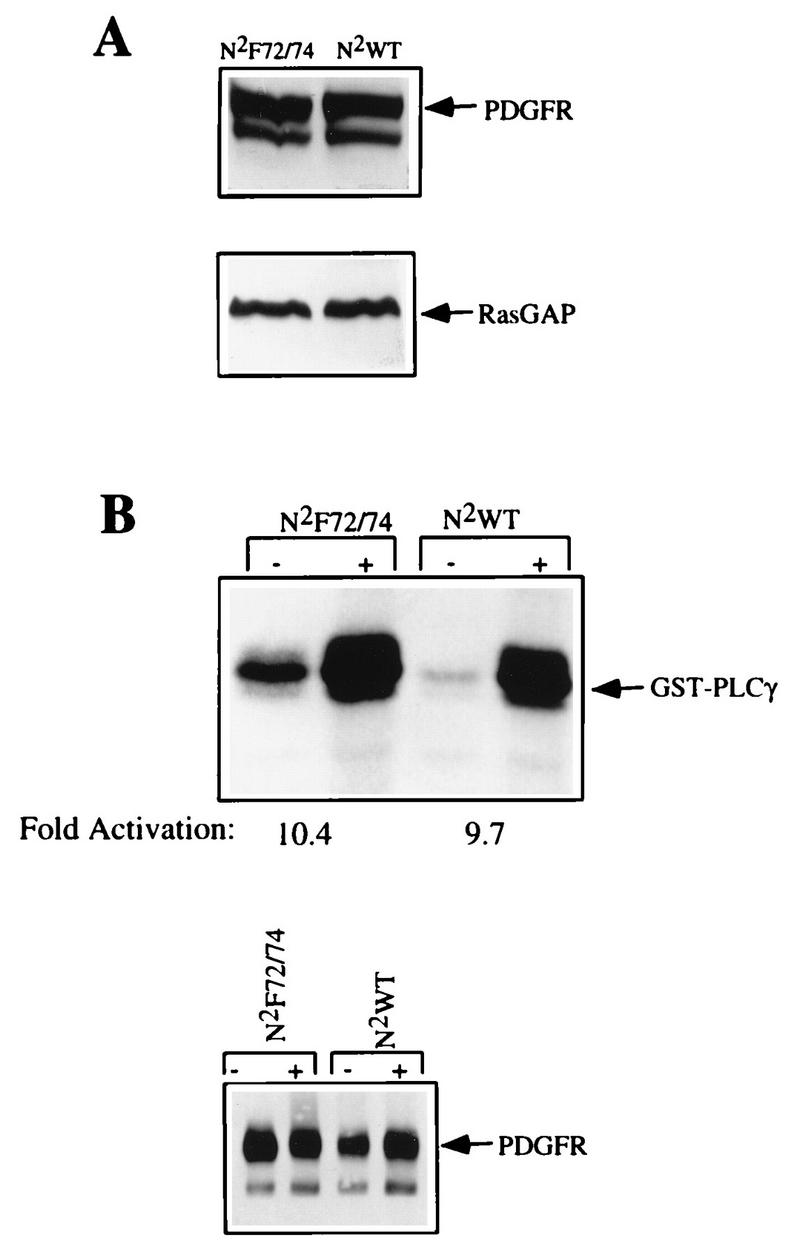

Both the αPDGFR and the βPDGFR contain two tyrosine residues in the juxtamembrane region of the receptor which are required for stable association of Src with the PDGFR and activation of Src kinase activity in PDGF-stimulated cells (10, 12, 22, 32). Substitution of these two tyrosine residues (Tyr 572 and 574) in the αPDGFR eliminates PDGF-dependent activation of Src and association of Src with the αPDGFR without any detectable effect on the αPDGFR’s kinase activity (10). Mutation of the analogous tyrosines (Tyr 579 and 581) in the βPDGFR leads to a dramatic decrease in the PDGF-stimulated receptor tyrosine phosphorylation (2, 22), and, consequently, the binding of many of the receptor-associated proteins is eliminated or severely reduced (2). To study the contribution of Src family members in βPDGFR signal relay, we needed a receptor mutant that selectively failed to associate with Src family members but retained its PDGF-dependent kinase activity and ability to recruit the other receptor-associated proteins. To accomplish this, we used a previously created and characterized chimeric PDGFR (6, 37) as a model for βPDGFR signaling. The chimera was constructed by fusing the extracellular, transmembrane, and juxtamembrane regions of the αPDGFR to the intracellular domain of the βPDGFR. In addition, using the previously described WT chimeric receptor (N2WT), we constructed an additional chimeric receptor (N2F72/74) in which the tyrosines required for Src binding (tyrosines 572 and 574) were mutated to phenylalanine residues. These receptor constructs were subcloned into the retroviral expression vector pLXSN2 (6, 20), and virus was obtained with the 293T system (16). The resulting virus was used to infect Ph cells, which are a fibroblast cell line derived from mouse embryos homozygous for the Ph/Ph deletion that includes the αPDGFR gene (27). Ph cells express normal levels of the endogenous βPDGFR (approximately 105 βPDGFRs/cell) but no αPDGFRs. Mass populations of cells were selected on the basis of resistance to G418, and drug-resistant cells were subjected to FACS analysis with a monoclonal antibody that recognizes the extracellular domain of the αPDGFR (PR292). The resulting cells were homogenous with respect to receptor expression, which was comparable to the endogenous level of βPDGFRs in Ph cells (27). Receptor expression in the resulting cell lines was verified by Western blot analysis of total cell lysates by using a polyclonal antibody, 80.8, against the extracellular domain of the αPDGFR. Figure 1A shows that both the N2WT and the N2F72/74 receptors were expressed in the Ph cells at similar levels. The lower panel of Fig. 1A is a RasGAP Western blot of the same samples and demonstrates that similar amounts of protein were present in both samples.

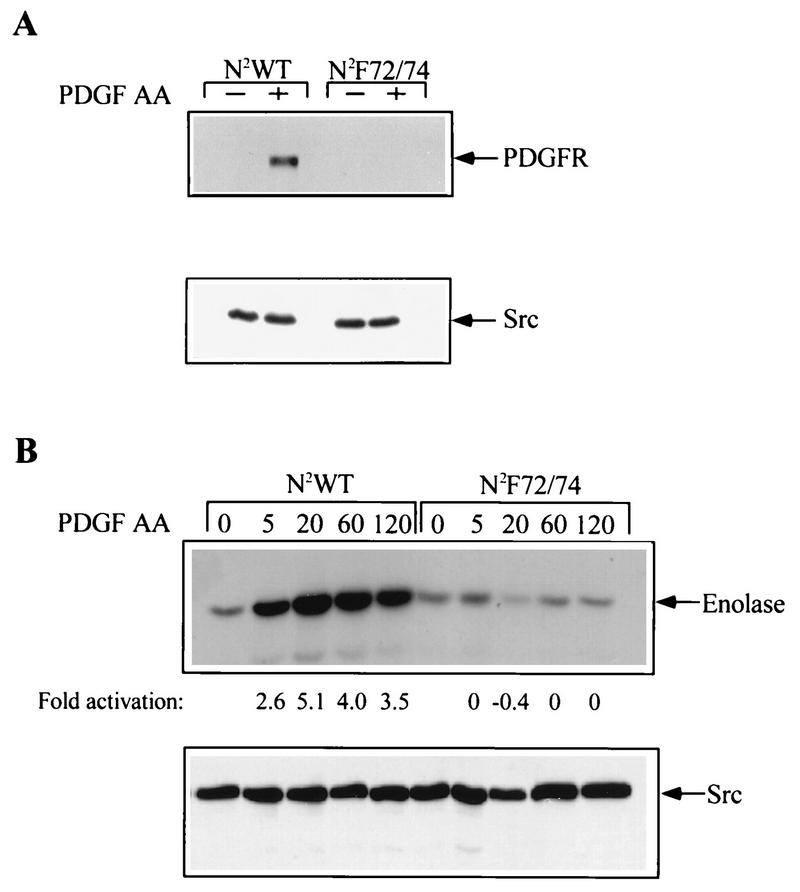

FIG. 1.

Characterization of the chimeric receptors. (A) Cell lysates representing 4.0 × 104 cells were subjected to anti-αPDGFR Western blot analysis. N2WT and N2F72/74 are Ph cells expressing the WT and F72/74 receptors, and the N2 prefix indicates a chimeric receptor. The bottom panel is a RasGAP Western blot performed on the same samples and indicates that there were similar amounts of cell lysate present in the samples. (B) Ph cells expressing the chimeric constructs were grown to 85 to 90% confluence and were left resting (−) or stimulated (+) with 50 ng of PDGF-AA per ml for 5 min. The Ph cells were lysed, and the chimeric receptors were immunoprecipitated with an antibody directed against the extracellular portion of the chimera. Immunoprecipitates, presenting approximately 1.5 × 105 cells, were subjected to an in vitro kinase assay in the presence of an exogenous substrate, GST-PLCγ. The proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the gel was subjected to autoradiography. The bottom panel is a PDGFR Western blot (the antibody is directed against the C terminus of the chimera) performed on the same immunoprecipitates.

Characterization of the WT and F72/74 chimeric PDGFRs.

Given that the chimeras were a combination of the αPDGFR and βPDGFR, which vary in their abilities to tolerate mutations in the juxtamembrane domains and retain PDGF-dependent kinase activity, we first examined the kinase activity of the N2F72/74 chimera by performing the following experiments. Ph cells expressing the chimeric receptors were grown to 85 to 90% confluence, starved in DME medium plus 0.1% calf serum for 18 to 24 h, stimulated for 5 min with 50 ng of PDGF-AA per ml, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with PR292. The immunoprecipitates were subjected to an in vitro kinase assay in the presence of the exogenous substrate GST-PLCγ, the proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the gel was exposed to film. The immunoprecipitates from both cell lines had readily detectable and comparable levels of kinase activity, as reflected by phosphorylation of the exogenous substrate (Fig. 1B). The kinase activity of the chimeric receptors was approximately ninefold greater in samples isolated from PDGF-stimulated cells as opposed to unstimulated cells. The lower basal level of kinase activity in the WT receptor was not routinely observed and probably reflects the slightly reduced amount of receptor in this sample (lower panel of Fig. 1B). The kinase activities of the N2WT and N2F72/74 receptors were compared by using an additional substrate, a GST–SHP-2 fusion protein, and we found that this substrate was phosphorylated by the two receptors equally well (data not shown). These findings indicate that mutating tyrosines 572 and 574 in the juxtamembrane domain of the chimeric receptor did not compromise its kinase activity.

Association with Src family members.

To evaluate the effect of mutating tyrosines 572 and 574 on the ability of Src family members (collectively referred to as Src unless otherwise indicated) to associate with the chimeric PDGFR, we examined coimmunoprecipitation of the receptor with Src. Ph cells expressing the N2WT and the N2F72/74 chimeras were grown to 85 to 90% confluence, starved for 18 to 24 h in DME medium plus 0.1% calf serum, and left resting or stimulated with PDGF-AA (50 ng/ml) for 5 min. The cells were then washed and lysed, and Src was immunoprecipitated with an antibody (Src 2) that recognizes all Src family members expressed in fibroblasts. The immunoprecipitates were then analyzed by Western blotting with an antibody that recognizes the intracellular domain of the chimera (30A). Note that this approach will detect a complex between the chimeric PDGFR and any of the Src family members expressed in fibroblasts. In response to PDGF, the chimeric N2WT PDGFR associated with Src, whereas binding of the N2F72/74 chimeric PDGFR to Src was undetectable (upper panel of Fig. 2A). The lower panel of Fig. 2A shows that there were comparable amounts of Src in the immunoprecipitates from N2F72/74- and N2WT-expressing cells. These findings demonstrate that mutation of the juxtamembrane tyrosines 572 and 574 severely compromised the ability of the N2F72/74 receptor to bind Src kinase family members.

FIG. 2.

Association and activation of Src. (A) Cells expressing the N2WT and N2F72/74 chimeras were grown to 85 to 90% confluence and then incubated in DME medium containing 0.1% calf serum. The cells were left resting (−) or stimulated (+) with 50 ng of PDGF-AA per ml and lysed, and Src was immunoprecipitated with an antibody that recognizes Src, Fyn, and Yes. The Src immunoprecipitates were washed, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and subjected to Western blot analysis with an antibody that recognizes the PDGFR (upper panel) or Src (lower panel). (B) Cells expressing the N2WT and N2F72/74 chimeras were arrested and then left resting (0) or stimulated (50-ng/ml PDGF-AA) for 5 to 120 min. Src was immunoprecipitated and subjected to an in vitro kinase assay with rabbit muscle enolase as the substrate. Equal amounts of enolase were present in each lane when the gel was stained with Coomassie blue (not shown). Phosphorylation was visualized by autoradiography, and the extent of phosphorylation was quantitated by excising the stained bands from the gel and counting them in a scintillation counter. The experiment and quantitation of bands were performed at least three times with similar results. The lower panel is a Src Western blot of these same samples.

We then assessed whether Src could be activated by the mutant receptor which failed to associate with Src. To this end, Src was immunoprecipitated from resting or PDGF-stimulated cells and the Src immunoprecipitates were subjected to an in vitro kinase assay with enolase as the substrate. We examined PDGF-dependent Src kinase activation over a 2-h time period and found that the N2WT chimera was able to induce rapid activation of Src kinase, which peaked at 20 min after PDGF stimulation and persisted for 2 h (Fig. 2B). We did observe some variability from experiment to experiment regarding the time at which Src activation peaks, but we have consistently observed the peak activation to occur between 5 and 20 min after PDGF stimulation. In contrast, the N2F72/74 chimera did not detectably activate Src during this entire time period. Later time points were not tested, since we do not expect the chimeric receptor to persist on the cell surface more than 1 to 2 h after addition of PDGF. Note that the chimeric receptor is present in Src immunoprecipitates from activated cells expressing the N2WT chimera (Fig. 2A) and could contribute to the phosphorylation of enolase seen in Fig. 2B. This is unlikely to be the case for the following reasons. The Src immunoprecipitates used in the experiment shown in Fig. 2B were prepared from RIPA lysates and washed with RIPA buffer instead of the milder lysis buffer used in the experiment shown in Fig. 2A. This procedure greatly reduced that amount of PDGFR that coprecipitated with Src (data not shown). Moreover, enolase is a very poor substrate for the chimeric receptor (data not shown). These findings indicate that the mutant receptor was not able to activate Src within the first 2 h following PDGF stimulation of cells and that binding of Src to the PDGFR via the juxtamembrane domain is required for activation of Src’s kinase activity.

Association of other receptor-associated proteins.

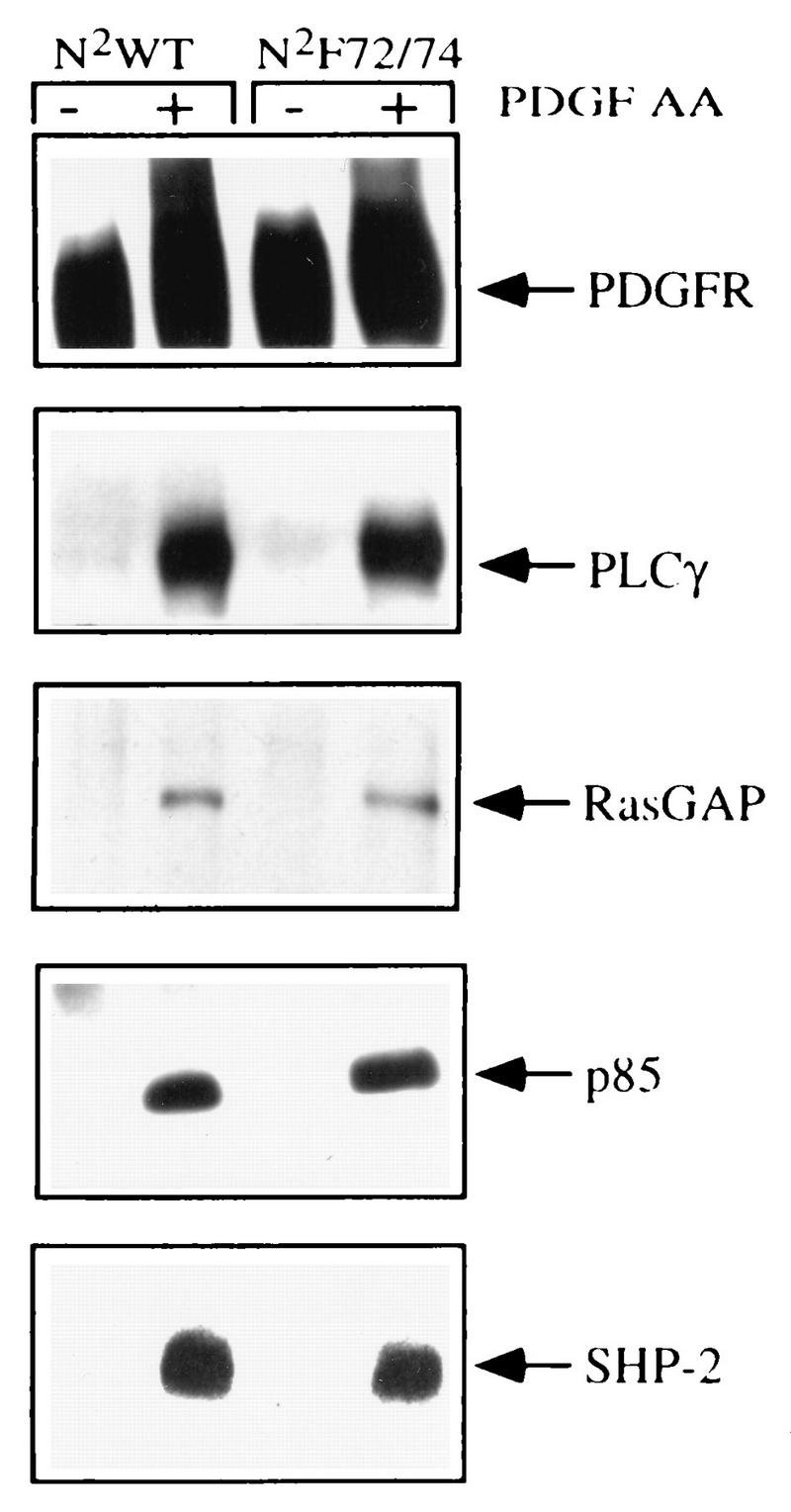

To determine if the N2F72/74 receptor was selectively impaired in its ability to associate with Src, we assayed the binding of some of the other receptor-associated proteins. The N2WT and N2F72/74 chimeras were immunoprecipitated from resting or PDGF-AA-stimulated cells, and samples were assayed by Western blotting with antibodies to the receptor as well as to the receptor-associated proteins indicated in the right-hand margin of Fig. 3. We found that PDGF stimulated the association of similar levels of PLCγ, RasGAP, p85, and SHP-2 to both the N2WT and the N2F72/74 receptors. Hence, mutating the juxtamembrane tyrosines in the chimeric receptor eliminates binding and activation of Src but does not affect the association of many of the other proteins that bind to the PDGFR.

FIG. 3.

Characterization of the proteins that associated with the PDGFR chimeras. Quiescent, 85 to 90% confluent cells expressing the N2WT and N2F72/74 receptors were left resting (−) or stimulated (+) with 50 ng of PDGF-AA per ml for 5 min and immunoprecipitated with PR292. The receptor immunoprecipitates representing approximately 1.0 × 106 cells were resolved on an SDS-7.5% PAGE gel, transferred to Immobilon, and immunoblotted with the indicated antisera. The associated proteins are indicated.

DNA synthesis and cell proliferation.

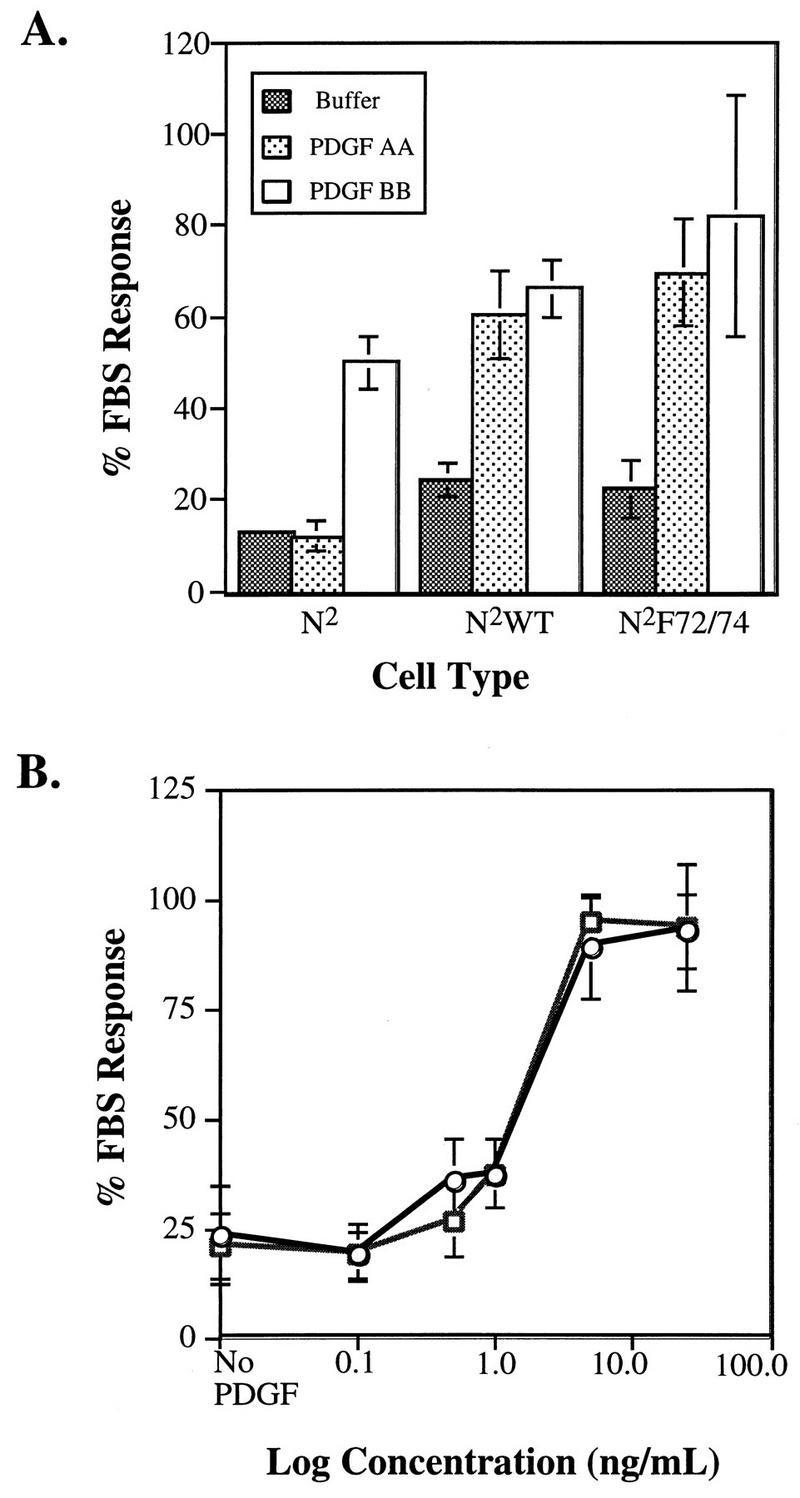

To determine whether the inability to activate Src during the G0/G1 transition affected PDGF-dependent cell cycle progression, we compared the abilities of the N2WT and N2F72/74 chimeras to initiate PDGF-dependent DNA synthesis and cell proliferation. To assay the ability of the chimeras to initiate DNA synthesis, Ph cells expressing an empty vector or the chimeric N2WT or N2F72/74 receptors were arrested by serum deprivation and then exposed to buffer or 50 ng of PDGF-AA or 40 ng of PDGF-BB per ml, pulsed with [3H]thymidine, and then harvested. Exposure to PDGF-AA increased DNA synthesis (60 to 70% of 10% fetal bovine serum) in cells expressing the N2WT or N2F72/74 receptors but not in the empty vector-expressing cells (Fig. 4A). DNA synthesis was stimulated in all three cell types following exposure to PDGF-BB, and we consistently observed that the response initiated by PDGF-BB was somewhat higher in the N2WT- and N2F72/74-expressing cells, compared to the empty-vector-expressing cell line (Fig. 4A). This is probably due to the ability of PDGF-BB to activate the introduced chimeric receptor as well as the endogenous receptor.

FIG. 4.

DNA synthesis. (A) Cells expressing an empty vector (N2) or the N2WT or N2F72/74 chimera were plated at a low cell density and allowed to become quiescent. Buffer, 10% FBS, or 50 ng of PDGF-AA or 40 ng of PDGF-BB per ml was added, and after 20 h the cells were pulsed with [3H]thymidine and then harvested. The data are expressed as a percentage of the response observed with FBS, which routinely stimulated a four- to fivefold increase over the samples treated with buffer. (B) Ph cells expressing the N2WT (○) or N2F72/74 (□) mutant chimera were plated, arrested by serum deprivation, and then exposed to buffer (No PDGF) or stimulated with 10% FBS or increasing concentrations of PDGF-AA. After 18 h, the cells were pulsed with [3H]thymidine for 4 h and then harvested. The experiment was performed three times; the graph is representative of one of these three trials. Each condition was assayed in triplicate, and the data are the means ± standard deviations.

These studies indicate that both N2WT- and N2F72/74-expressing Ph cells were able to initiate a comparable DNA synthesis response at a saturating dose of PDGF-AA, but it is possible that at subsaturating doses there are differences between the two cell types. To address this issue, we compared the abilities of the WT and mutant cell lines to induce DNA synthesis at submaximal concentrations of PDGF. The DNA synthesis responses of the two cell lines were assayed as described above. Both the N2WT- and N2F72/74-expressing Ph cells induced a PDGF-dependent entry into S phase in a dose-dependent manner, and there was no difference in their abilities to initiate the response at subsaturating doses of PDGF (Fig. 4B). These studies show that the chimeric receptor is able to stimulate progression of cells into the S phase and that activation of Src within the first 2 h is not required for this event.

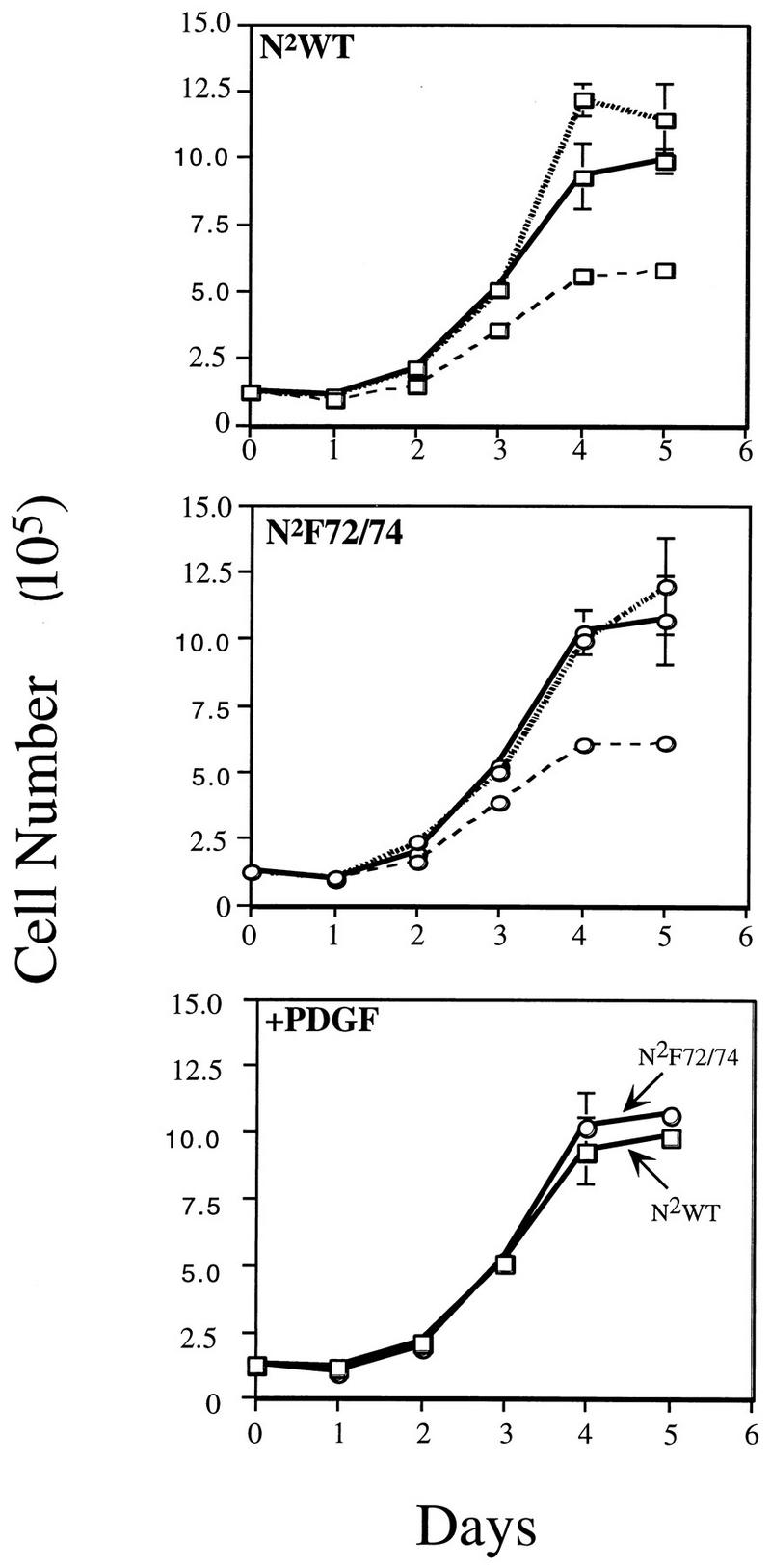

The DNA synthesis assays employed did not provide information regarding progression to later stages of the cell cycle or proliferation of cells. To address these issues, we compared the cell lines for their abilities to proliferate in a monolayer culture and to grow in soft agar. Cell doubling in a monolayer assay was assessed by plating the N2WT- and N2F72/74-expressing Ph cells at low density in DME medium plus 1.0% plasma-derived serum in the presence of buffer, 5% calf serum, or 25 ng of PDGF-AA per ml. The cultures were incubated at 37°C for 5 days, and the numbers of cells were counted daily. PDGF-AA stimulated the growth of N2WT- and N2F72/74-expressing Ph cells to comparable extents (Fig. 5, lower panel), and the number of cells approximately doubled each day until a plateau was reached at about 5 days. Five percent calf serum also stimulated growth of both cell types, while there was significantly less growth in cultures exposed to buffer (Fig. 5, top and middle panels). These data show that activation of Src at the start of the cell cycle was not required for cell proliferation.

FIG. 5.

Cell proliferation. Ph cells expressing the N2WT (top panel) or N2F72/74 (middle panel) receptors were plated at 1.25 × 105 cells per well in DME medium plus 1.0% plasma-derived serum in the presence of buffer (– – –), 5% calf serum (shaded line), or 25 ng of PDGF-AA (———) per ml. The cells were counted every day, and the data are the means of triplicate samples ± standard deviations. The bottom panel compares the responses of N2WT (○) and N2F72/74 (□) to PDGF-AA.

The ability of the N2WT- and N2F72/74-expressing Ph cells to proliferate was also assessed by measuring growth in soft agar. Ph cells expressing empty vector (N2), chimeric N2WT, or N2F72/74 PDGFR were plated in soft agar containing buffer alone, PDGF-AA, or PDGF-BB. PDGF-AA was employed to measure focus formation in response to activation of the introduced chimeric receptors, whereas since PDGF-BB activates both the endogenous and the introduced PDGF receptors, the resulting PDGF-dependent soft agar growth reflected the contribution of all PDGFRs. Foci in soft agar were photographed and quantitated after an 8- to 10-day incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells expressing the empty vector did not grow in agar containing buffer or PDGF-AA, whereas an average of 5,236 colonies were detected in a 35-mm plate of cells supplemented with 200 ng of PDGF-BB per ml (Table 1). The N2WT and N2F72/74 cells were both able to grow in soft agar when it contained PDGF-AA or -BB, but not buffer alone (Table 1). The data presented in Fig. 4 and 5 and Table 1 indicate that activation of Src during the G0/G1 transition is dispensable for cell cycle progression and proliferation of cells.

TABLE 1.

Growth of cells in soft agara

| Cell type | No. of colonies (mean ± SD)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Buffer | PDGF-AA | PDGF-BB | |

| N2 | 0 | 0 | 5,236 ± 671 |

| N2WT | 0 | 10,428 ± 460 | 14,788 ± 437 |

| N2F72/74 | 0 | 11,231 ± 119 | 13,939 ± 953 |

Cells expressing an empty vector (N2), the WT chimera (N2WT), or the F72/74 chimera (N2F72/74) were plated in DME medium plus 5% calf serum in the presence of buffer or 200 ng of PDGF-AA or PDGF-BB per ml, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 8 to 10 days. Soft agar assays were performed at least three times. Foci of more than eight cells were scored as a colony, and the morphologies of the colonies in both N2WT and N2F72/74 cells were similar.

The observation that constitutive expression of c-myc rescued PDGF-dependent DNA synthesis in cells microinjected with reagents that neutralize Src activity suggested that Src is required for c-myc expression (1). While activation of Src early in the cell cycle did not appear to be required for cell proliferation (Fig. 2B, 4, and 5; Table 1), we were curious to see if the N2F72/74 chimera was capable of activating c-myc. Quiescent cells expressing the N2WT or N2F72/74 chimera were left unstimulated or exposed to PDGF-AA for 20 to 240 min, and RNA was harvested and subjected to Northern blot analysis. We found that the chimeric receptors were comparable in their abilities to activate c-myc (data not shown), and this result is reminiscent of our findings that the αPDGFR mutant that does not activate Src is fully capable of activating c-myc (10). These findings suggest that activation of Src early in the cell cycle is not required for PDGF-dependent induction of c-myc.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of proteins in PDGF-stimulated cells.

The data in Fig. 2B, 4, and 5 and Table 1 demonstrate that an increase in Src activity during the G0/G1 transition is not required for cell cycle progression. These findings beg the question of why Src is activated at the G0/G1 transition in a PDGF-stimulated cell. Previous studies with βPDGFR mutants indicated that recruitment of RasGAP to the receptor inhibited activation and tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ (35). Attempts to understand the underlying mechanism for these events suggested that RasGAP functionally sequesters Src and thereby prevents PLCγ tyrosine phosphorylation (26). These observations also lead to the hypothesis that Src is involved in tyrosine-phosphorylating proteins that have been previously considered direct substrates of the PDGFR. We tested this hypothesis by comparing the extents of PDGF-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of proteins in cells expressing the N2WT or N2F72/74 chimeras. To this end, Ph cells expressing the empty vector or the N2WT or N2F72/74 chimera were arrested by serum starvation and then left resting or stimulated with 50 ng of PDGF-AA per min for 5 min. Total cell lysates or antiphosphotyrosine immunoprecipitates were subjected to an antiphosphotyrosine Western blot. PDGF stimulation of the N2WT cells led to increased recovery of numerous tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins, including a 180-kDa species which was most probably the receptor itself. With the exception of this 180-kDa species, the PDGF-dependent phosphorylation of most other species was markedly reduced in samples from N2F72/74 cells (data not shown). These data indicated that the phosphorylation level of proteins was diminished in cells expressing the PDGFR mutant that does not activate Src.

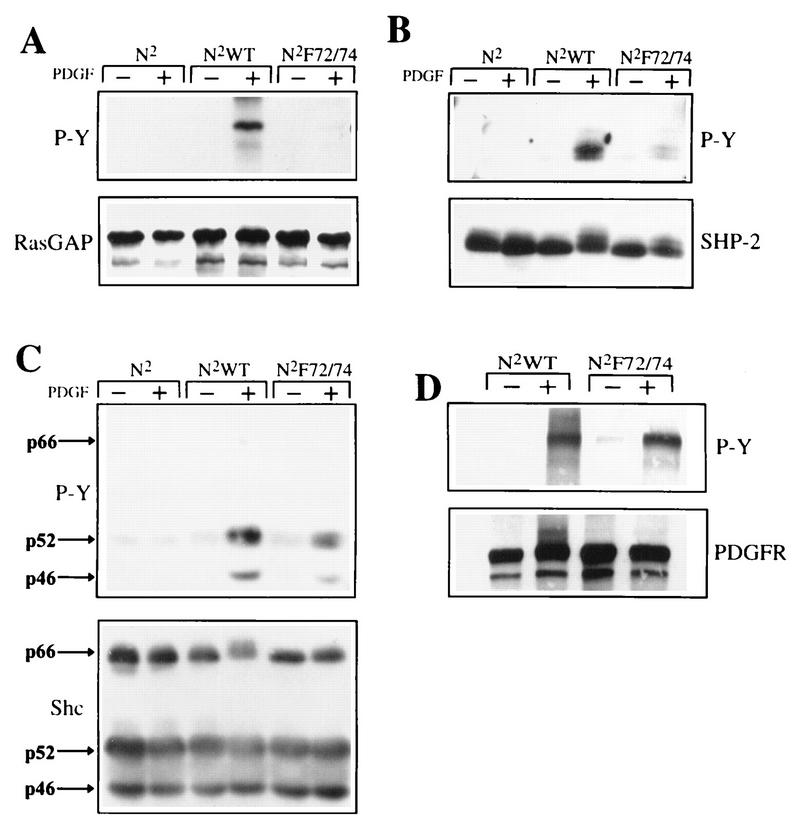

We further investigated this possibility by examining the phosphorylation state of a number of proteins that either stably associated with the βPDGFR and/or were tyrosine phosphorylated in response to PDGF stimulation. Ph cells expressing the empty vector or the N2WT or N2F72/74 chimera were left resting or stimulated with PDGF-AA for 5 min and were lysed, and RasGAP, SHP-2, and Shc were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against each of these proteins. The immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to Immobilon, and probed with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies. To determine whether the amounts of immunoprecipitated protein in the samples were similar, the antiphosphotyrosine blots were stripped and then reprobed with the immunoprecipitating antiserum (lower panel in each pair in Fig. 6). Stimulation of the empty-vector-expressing cells (N2) did not increase the tyrosine phosphorylation of any of the proteins tested. Upon stimulation of the N2WT-expressing Ph cells with PDGF-AA, RasGAP, Shc, and SHP-2 were all tyrosine phosphorylated. The N2F72/74 receptor was also able to drive tyrosine phosphorylation of all of these proteins; however, the extent of phosphorylation was dramatically reduced compared with that of the N2WT receptor. The levels of phosphorylation of RasGAP and SHP-2 were consistently reduced by at least 97 and 81%, respectively, whereas the level of Shc phosphorylation of the p46 isoform was reduced by 65% and that of the p52 isoform was reduced by 47% of that of the WT. We have also found that PLCγ tyrosine phosphorylation is dramatically reduced in N2F72/74-expressing cells (26).

FIG. 6.

PDGF-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of proteins. Cells were left resting (−) or stimulated (+) with 50 ng of PDGF-AA per ml and then lysed and immunoprecipitated with antibodies against RasGAP (A), SHP-2 (B), Shc (C), or the chimeric βPDGFR (D). The immunoprecipitates representing approximately 1.5 × 106 cells were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon, and antiphosphotyrosine Western blot analyses were performed (top panels). The Western blots were then stripped and reprobed with antibodies against the immunoprecipitated proteins (bottom panels). All experiments were repeated at least three times.

An explanation for inefficient tyrosine phosphorylation of receptor-associated proteins is that the receptor itself is not tyrosine phosphorylated well. To examine the levels of tyrosine phosphorylation of the N2WT and N2F72/74 chimeras, the chimeric receptors were immunoprecipitated as described above and subjected to antiphosphotyrosine Western blot analysis. In response to PDGF-AA stimulation, both the N2WT and the N2F72/74 chimeras were tyrosine phosphorylated to similar extents (Fig. 6D). The lower panel in Fig. 6D is the same blot reprobed with a receptor antibody and shows that there were comparable amounts of receptors in the immunoprecipitates. Furthermore, Fig. 3 shows that the N2WT and N2F72/74 receptors associated with comparable amounts of a panel of SH2 domain-containing proteins, whose binding requires that the receptor be phosphorylated at several different tyrosines. Thus, the inability of the mutant receptor to efficiently phosphorylate the receptor-associated proteins does not appear to be due to a defect in the extent of receptor phosphorylation or to a problem with recruiting these proteins to the receptor.

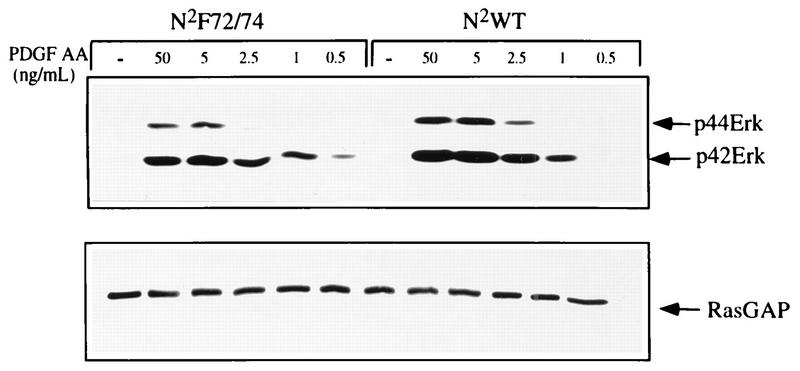

The consequence of inefficiently phosphorylating receptor-associated proteins for downstream signaling pathways was assessed by comparing the abilities of the N2WT- and N2F72/74-expressing Ph cells to induce Erk activation at various doses of PDGF. To this end, total cell lysates were harvested from serum-starved Ph cells expressing the two chimeras which were left unstimulated or treated for 5 min with a series of PDGF-AA concentrations. The total cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies which recognize phosphorylated p42 and p44Erk. Both the N2WT- and the N2F72/74-expressing Ph cells were able to activate Erk to comparable extents at a low dose (1.0 ng/ml) of PDGF-AA (Fig. 7). In contrast, the N2WT chimera was better able to activate both p42 and p44 Erk at higher doses (2.5, 5, and 50 ng/ml) of PDGF-AA (Fig. 7). The RasGAP Western blot in the bottom panel indicates that these differences are not due to differences in the level of protein present in each lane. We also examined Erk activation as a single dose (50 ng/ml) of PDGF but varied the duration of stimulation and found that there were no differences between the two cell types at 5 to 40 min after PDGF stimulation (data not shown). These findings suggest that efficient phosphorylation of receptor-associated proteins via Src or a Src-activated kinase is needed to drive maximal activation of pathways downstream of the receptor such as Erk activation.

FIG. 7.

Erk activation. Ph cells expressing the introduced receptors were left resting (−) or stimulated (+) with the indicated concentrations of PDGF-AA for 5 min at 37°C. Total cell lysates were harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies which recognize phospho-Erk (top panel). The bottom panel is a RasGAP Western blot of the same lysates indicating the levels of protein present.

DISCUSSION

We have used a chimeric βPDGFR to investigate the role of Src in βPDGFR signal relay. The advantage of such a chimera is that unlike the βPDGFR, its kinase activity was not compromised when the two tyrosines residues required for stable association with Src were mutated. Characterization of the WT and F72/74 chimeras suggested that the initial burst of Src kinase activity that occurred when the βPDGFR was activated was necessary for efficient tyrosine phosphorylation of many of the signaling enzymes that associate with the βPDGFR. In contrast, activation of Src at the beginning of the cell cycle was not required for later cycle events such as entry into the S phase or cell proliferation.

The chimeric βPDGFR which does not detectably activate Src is fully competent to autophosphorylate and to phosphorylate exogenous substrates in an in vitro kinase assay, yet it is unable to mediate efficient phosphorylation of many of the receptor-associated proteins. One interpretation of these data is that Src contributes to the phosphorylation of the receptor-associated proteins. In this scenario, Src is recruited to the receptor, Src’s kinase is activated, and then Src either directly phosphorylates the receptor-associated proteins or activates additional kinases which phosphorylate these proteins. The observations that Src or Src family members are able to phosphorylate many of the receptor-associated proteins (Shc, PLCγ, and RasGAP) (7, 19, 23, 36) indirectly supports this idea.

Since Src is activated upon engagement of many different receptor tyrosine kinases (for a review, see reference 8), does Src play a role in the phosphorylation of intracellular substrates for other receptor tyrosine kinases as well? We have begun to address this question with the αPDGFR. Like the chimeric βPDGFR, a mutant αPDGFR that cannot activate Src fails to efficiently phosphorylate Shc (10). In contrast, activation of Src does not seem to be necessary for the αPDGFR to drive phosphorylation of SHP-2 or PLCγ. Thus, the αPDGFR does not need to activate Src in order to phosphorylate some of the signaling molecules that associate with the αPDGFR. Whether the αPDGFR is able to directly phosphorylate these receptor-associated proteins or whether there is some other cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase contributing to these events is currently being investigated.

Recent contributions from several labs have indicated that Src is required for cell cycle progression. By a microinjection approach, Courtneidge’s lab demonstrated that there was a Src-dependent phase late in G1 and that microinjection of reagents that neutralize all Src activity (basal as well as stimulated) inhibited PDGF-dependent entry of cells into the S phase (31). Similarly, constitutive expression of mutant forms of Src in cells that lack endogenous Src blocked PDGF-dependent DNA synthesis (4). Finally, the microinjection approach was also used to demonstrate that Src activity was essential for the G2/M transition (24). These findings reveal that the elimination of all Src activity prevents cell cycle progression at several stages in the cell cycle.

Our results are consistent with these previous findings and make a number of additional contributions. By manipulating the PDGFR instead of Src, we were able to selectively eliminate the increase in Src activity occurring in response to PDGF stimulation. By this approach, we found that an increase in Src activity at the G0/G1 transition in PDGF-stimulated cells is not required for entry into S phase or cell proliferation. Together with the work of other groups, our findings suggest that the G1/S transition requires basal Src activity and/or an increase in Src activity later in G1. The findings that phosphorylation of cortactin, a likely Src substrate, is robustly tyrosine phosphorylated in late G1 in FGF-treated cells (38, 39) indirectly supports the idea that Src is activated later in G1.

The observation that activation of Src and robust phosphorylation of signaling enzymes are not required for PDGF-dependent transition through the cell cycle raises a number of interesting issues regarding the importance of phosphorylating these molecules for cell cycle progression. One possibility is that phosphorylation of signaling molecules is not required for PDGF-dependent mitogenic signaling. Alternatively, only a low level of signaling events is required for initiating a biological response, as has been suggested by the spare receptor hypothesis. Since βPDGFR is capable of triggering multiple, apparently redundant signaling pathways, eliminating or partially reducing the input of these pathways may not prevent mitogenic signaling. Note that the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway does not seem to require tyrosine phosphorylation to be activated in this system and appears to be fully activated by the N2F72/74 chimera. Since the PI3K pathway drives growth of Ph cells (6), it is likely that the mutant receptor uses PI3K to initiate the observed biological responses. Finally, there may be alternative and/or compensatory pathways by which the N2F72/74 chimera triggers cell proliferation.

While efficient phosphorylation of signaling proteins is not required to drive a mitogenic response from the chimeric PDGFR, Erk activation is modestly suppressed when Src is not activated. These observations indicate that an increase in Src activity leads to enhanced Erk activation. Given that Erk activation is observed prior to almost any biological response, it is difficult to immediately appreciate the significance of this observation. One possibility is that an increase in Src activity at the G0/G1 transition serves to amplify the ensuing signaling pathway. Such a role for Src has come forth from the observations that expression of v-src or overexpression of c-src potentiates EGF-dependent transformation of cells (18). It is also possible that the increase in Src activity in a PDGF-stimulated cell alters the nature instead of the amplitude of the response. This possibility is currently under investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Charlie Hart for the PDGF, Gen Shen Feng for the anti-Syp antibody, and Dan Bowen-Pope for the Ph cells and the PR292 antibody. We also thank Eglè Balčiünaite, Amy Bernard, Steven Jones, Nader Rahimi, and Stephan Rosenkranz for critical comments regarding the manuscript. K.D. thanks Julie Gelderloos for support and encouragement during the evolution of this project.

This work was supported by NIH grants GM48339 and EY11693.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barone M V, Courtneidge S A. Myc but not Fos rescue of PDGF signalling block caused by kinase-inactive Src. Nature. 1995;378:509–512. doi: 10.1038/378509a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baxter, R. M., J. P. Secrist, R. R. Vaillancourt, and A. Kauzlauskas. Full activation of the PDGF β receptor kinase involves multiple events. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bazenet C, Kazlauskas A. The PDGF receptor alpha subunit activates p21ras and triggers DNA synthesis without interacting with rasGAP. Oncogene. 1994;9:517–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broome M A, Hunter T. Requirement for c-Src catalytic activity and the SH3 domain in platelet-derived growth factor BB and epidermal growth factor mitogenic signaling. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16798–16806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper J A, King C S. Dephosphorylation or antibody binding to the carboxy terminus stimulates pp60c-src. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:4467–4477. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.12.4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeMali K A, Whiteford C C, Ulug E T, Kazlauskas A. PDGF-dependent cellular transformation requires either PLC γ or PI3K. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9011–9018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis C, Moran M, Mccormick F, Pawson T. Phosphorylation of GAP and GAP-associated proteins by transforming and mitogenic tyrosine kinases. Nature. 1990;343:377–381. doi: 10.1038/343377a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erpel T, Alonso G, Roche S, Courtneidge S A. The Src SH3 domain is required for DNA synthesis induced by platelet-derived growth factor and epidermal growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16807–16812. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng G-S, Hui C-C, Pawson T. SH2-containing phosphotyrosine phosphatase as a target of protein-tyrosine kinases. Science. 1993;259:1607–1611. doi: 10.1126/science.8096088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelderloos, J. A., S. Rosenkranz, C. Bazenet, and A. Kazlauskas. A role for Src in signal relay of the PDGF α receptor. J. Biol. Chem., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Gould K, Hunter T. Platelet-derived growth factor induces multisite phosphorylation of pp60c-src and increases its protein tyrosine kinase activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:3345–3356. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.8.3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hooshmand-Rad R, Yokote K, Heldin C-H, Claesson-Welsh L. PDGF alpha receptor mediated cellular responses are not dependent on src family kinases. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:607–614. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.5.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kazlauskas A, Bowen-Pope D, Seifert R, Hart C E, Cooper J A. Different effects of homo- and heterodimers of platelet-derived growth factor A and B chains on human and mouse fibroblasts. EMBO J. 1988;7:3727–3335. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03256.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kazlauskas A, Kashishian A, Cooper J A, Valius M. GTPase-activating protein and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase bind to distinct regions of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor β subunit. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2534–2544. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.6.2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klinghoffer A R, Kazlauskas A. Identification of a putative Syp substrate, the PDGF beta receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22208–22217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landau N R, Littman D R. Packaging system for rapid production of murine leukemia virus vectors with variable tropism. J Virol. 1992;66:5110–5113. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.5110-5113.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipsich J A, Lewis A J, Brugge J S. Isolation of monoclonal antibodies that recognize the transforming proteins of avian sarcoma viruses. J Virol. 1983;48:352–360. doi: 10.1128/jvi.48.2.352-360.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luttrell D K, Luttrell L M, Parsons S J. Augmented mitogenic responsiveness to epidermal growth factor in murine fibroblasts that overexpress pp60c-src. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:497–501. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.1.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGlade J, Cheng A, Pelicci G, Pelicci P G, Pawson T. Shc proteins are phosphorylated and regulated by the v-Src and v-Fps protein tyrosine kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8869–8873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.8869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller A D, Rosman G J. Improved retroviral vectors for gene transfer and expression. BioTechniques. 1989;7:980–990. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan D O, Kaplan J M, Bishop J M, Varmus H E. Mitosis-specific phosphorylation of p60c-Src by p34cdc2-associated protein kinase. Cell. 1989;57:775–786. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90792-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mori S, Rönnstrand L, Yokote K, Engström A, Courtneidge S A, Claesson-Welsh L, Heldin C-H. Identification of two juxtamembrane autophosphorylation sites in the PDGF β-receptor: involvement in the interaction with src family tyrosine kinases. EMBO J. 1993;12:2257–2264. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park D J, Rho H W, Rhee S G. CD3 stimulation causes phosphorylation of phospholipase C-γ on serine and tyrosine residues in a human T-cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5453–5456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roche S, Fumagalli S, Courtneidge S A. Requirement for src family protein tyrosine kinases in G2 for fibroblast cell division. Science. 1995;269:1567–1569. doi: 10.1126/science.7545311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roche S, Koegl M, Varone M V, Roussel M F, Courtneidge S A. DNA synthesis induced by some but not all growth factors requires Src family protein tyrosine kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;15:1102–1109. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.2.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlesinger, T. K., K. A. DeMali, G. L. Johnson, and A. Kazlauskas. Unpublished data.

- 27.Seifert R A, van Koppen A, Bowen-Pope D F. PDGF-AB requires PDGF receptor α-subunits for high-affinity, but not for low-affinity, binding and signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4473–4480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shenoy S, Choi J-K, Bagrodia S, Copeland T D, Maller J L, Shalloway D. Purified maturation promoting factor phosphorylates pp60c-src at the sites phosphorylated during fibroblast mitosis. Cell. 1989;57:763–774. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90791-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soriano P, Montgomery C, Geske R, Bradley A. Targeted disruption of the c-src proto-oncogene leads to osteopetrosis in mice. Cell. 1991;64:693–702. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90499-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stein P L, Vogel H, Soriano P. Combined deficiencies of src, fyn, and yes tyrosine kinases in mutant mice. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1999–2007. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.17.1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Twamlay-Stein G M, Pepperkok R, Ansorge W, Courtneidge S A. The Src family tyrosine kinases are required for platelet-derived growth factor-mediated signal transduction in NIH 3T3 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7696–7700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaillancourt R R, Heasley L E, Zamarripa J, Storey B, Valius M, Kazlauskas A, Johnson G L. Mitogen-activated protein kinase activation is insufficient for growth factor receptor-mediated PC12 cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3644–3653. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valius M, Bazenet C, Kazlauskas A. Tyrosines 1021 and 1009 are phosphorylation sites in the carboxy terminus of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor β subunit and are required for binding of phospholipase Cγ and a 64-kilodalton protein, respectively. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:133–143. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valius M, Kazlauskas A. Phospholipase C-γ1 and phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase are the downstream mediators of the PDGF receptor’s mitogenic signal. Cell. 1993;73:321–334. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90232-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valius M, Secrist J P, Kazlauskas A. The GTPase-activating protein of Ras suppresses platelet-derived growth factor β receptor signaling by silencing phospholipase C-γ1. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3058–3071. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiss A, Koretzky G, Schatzman R C, Kadlecek T. Functional activation of the T-cell antigen receptor induces tyrosine phosphorylation of phospholipase C-γ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5484–5488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whiteford C C, Best C, Kazlauskas A, Ulug E T. D-3 phosphoinositide metabolism in PDGF-treated cells. Biochem J. 1996;319:851–860. doi: 10.1042/bj3190851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhan X, Hu X, Hampton B, Burgess W H, Friesel R, Maciag T. Murine cortactin is phosphorylated in response to fibroblast growth factor-1 on tyrosine residues late in the G1 phase of the BALB/c3T3 cell cycle. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24427–24431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhan X, Plourde C, Hu X, Friese R, Maciag T. Association of fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 with c-Src correlates with association between c-Src and cortactin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20221–20224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]