Summary

Background

The cycle of maltreatment theory posits a linkage between mothers' and offspring's exposures to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), and their associations with offspring's early-life mental health; however, such associations in adulthood remain unclear. This study aims to examine the intergenerational association between mothers' ACEs, offspring's ACEs, and offspring's mental health from pregnancy to three years after childbirth, and to explore the potential pathways.

Methods

We used data on 1931 mother-offspring dyads from the longitudinal Grandmothers, Mothers, and Their Children's Health study in Huai'an city, China. ACEs were retrospectively assessed based on the Childhood Trauma Screener. Offspring's symptoms of anxiety and depression were measured through self-reported diagnoses or symptoms and standard questionnaires (the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale for anxiety and the 10-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for depression) during pregnancy, one year and three years after childbirth. Logistic regression models were conducted to estimate the associations. The structural equation model (SEM) was used to examine the potential mediating pathways.

Findings

A total of 367 (19.0%) mothers and 271 (14.0%) female offspring reported the history of ACEs. Female offspring of mothers with ACEs also had higher odds of exposure to ACEs (odds ratio [OR] = 3.37, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.51–4.53). Mothers' and female offspring's exposures to ACEs were both associated with higher odds of offspring experiencing mental disorders during the perinatal period. For example, female offspring with ACEs had 2.05-fold (95% CI: 1.54–2.72), 2.41-fold (95% CI: 1.75–3.33), and 2.30-fold (95% CI: 1.58–3.33) increased odds of the anxious or depressive symptoms during pregnancy, one year, and three years after childbirth, respectively, compared to offspring without ACEs. Results from the SEM indicated that mothers' ACEs and female offspring's perinatal mental health were linked mainly through the mediation role of female offspring's ACEs.

Interpretation

Mothers' and female offspring's likelihood of exposure to ACEs are intergenerationally associated and are both related to offspring's perinatal mental health. Female offspring's ACEs mediate the association between mothers' ACEs and female offspring's adulthood mental health. Our findings highlight the need for policies to break the cycle of maltreatment and promote women's mental health across multiple generations, in particular through family-based interventions.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72474197), China Medical Board Open Competition Program (21-416), Key Medical Program of Jiangsu Health Commission (ZD2021044), and Huai'an Science and Technology Program (HAB2024039).

Keywords: Adverse childhood experiences, Intergenerational association, Mental health, Anxiety, Depression

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We conducted a literature review in PubMed from inception to November 29, 2024, using the search terms “((intergenerational association) OR (intergenerational transmission)) AND ((maternal) OR (offspring)) AND ((adverse childhood experiences) OR (childhood adversity) OR (childhood maltreatment) OR (childhood abuse)) AND ((mental disorders) OR (mental health problems) OR (anxiety) OR (depression) OR (anxiety symptoms) OR (depressive symptoms))”. We also reviewed the reference lists of retrieved articles to identify additional relevant studies. We identified articles addressing the impact of mothers' adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) on their offspring's mental health during early life; however, the impact on the mental health of adult offspring remains unclear. Furthermore, most intergenerational studies on childhood adversity have been conducted in Western or high-income countries, while evidence from diverse cultural and socioeconomic contexts remains limited.

Added value of this study

We used data from the Grandmothers, Mothers, and Their Children's Health study, a cohort that enrolls three biologically related generations of women in family units in China. The study included assessments of ACEs in the first two generations and evaluations of mental health outcomes in the second generation during pregnancy, one year after childbirth, and three years after childbirth. The current study, based on data from the first two generations, revealed that mothers' ACEs have long-lasting impacts on offspring. Specifically, we observed that mothers' and offspring's likelihood of exposure to ACEs were intergenerationally related, and both mothers' and offspring's exposures to ACEs were associated with a higher risk of mental disorders during the perinatal period. Additionally, the offspring's own ACEs primarily mediated the association between their mothers' ACEs and their own mental disorders.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our findings have important implications for long-term public health strategies to mitigate the intergenerational impact of ACEs on women's mental health. Integrating ACEs screening into routine perinatal care could help identify high-risk populations by assessing ACEs exposure in both pregnant women and their mothers. Mental health surveillance for these high-risk groups should extend beyond pregnancy and the immediate postpartum period, ideally lasting throughout life. Moreover, family-based prevention and intervention strategies should target families where women or their mothers have experienced ACEs. Considering the importance of breaking the intergenerational cycle of ACEs for offspring's long-term mental health, public health policies should leverage child health management as a key intervention opportunity. Providers should prioritize families identified through perinatal ACEs screening and offer family-based parenting education to support children's socio-emotional development, thereby reducing the risk of ACEs continuity.

Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), including physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, or neglect before 18 years old, are highly prevalent, with an estimated prevalence ranging from 12.7% to 26.7% worldwide.1,2 ACEs exposure is associated with a wide range of adverse physical and psychological consequences that persist from early adulthood into mid-to-late life.3 Alterations in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis are considered a key mechanism underlying these associations.4 Due to the influence of gonadal hormones on HPA axis responses,5,6 women and girls may experience heightened stress perception in response to ACEs, contributing to an enduring vulnerability to stress-related disorders throughout their life courses.7 This underscores the need to address ACEs-related mental health issues, particularly within the female population.

The cycle of maltreatment hypothesis posits that a parent's history of maltreatment may increase the risk of offspring being exposed to maltreatment.8 A systematic review and meta-analysis of 142 studies found a moderate association between parental and offspring's exposure to ACEs.9 However, most previous studies were based on relatively small sample sizes (median n = 222),9 limiting the representability of the results. Additionally, the majority of prior research has focused on Western or high-income countries, with limited evidence from populations with diverse cultural and socioeconomic contexts. In particular, China places a strong emphasis on collective relationships and family-centered values, raising the question of whether these cultural factors shape the cycle of maltreatment within Chinese families.

Beyond the direct cycle of ACEs, emerging studies have shown that parental ACEs are also associated with offspring's health problems.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 For example, an observational study involving 1293 families from the US revealed that maternal ACEs were linked to early childhood developmental delays in offspring.13 Another prospective study of over 2500 mother-child dyads from the Netherlands reported an association between maternal ACEs and psychotic experiences in offspring.14 Similarly, a cross-sectional study in Korea found that maternal ACEs were related to both internalizing and externalizing problems in offspring.15 To date, most studies have focused on short-term outcomes in offspring, with follow-up periods extending only to adolescence. Research on long-term outcomes, particularly during the reproductive years in adulthood, remains limited.

The period from pregnancy to the first three years after childbirth, often referred to as “the first 1000 days”, is a critical window for brain development and heightened sensitivity to adversity in children.16 During this time, poor maternal mental health may act as a source of stress, triggering frequent and prolonged toxic stress responses in children.17,18 This disrupts normal brain development, architecture, and function, increasing vulnerability to long-term negative health outcomes,17 especially in female offspring.6 These early life adversities may contribute to a harmful intergenerational cycle of health issues within families. Understanding how ACEs in one generation impact the mental health of offspring during the perinatal period is essential for developing strategies to promote health across generations.

Using data from the Grandmothers, Mothers, and Their Children's Health (GMATCH) study—a cohort enrolling three generations of women—this study aims to examine the intergenerational associations between mothers' and female offspring's exposure to ACEs and their long-term effects on female offspring's mental health from pregnancy to three years after childbirth in a Chinese population.

Methods

Study design and population

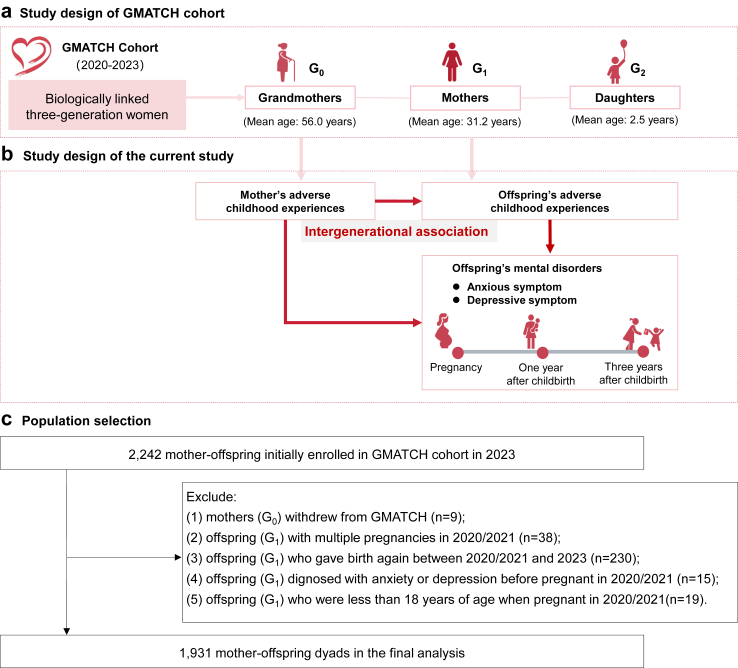

This study used data from the GMATCH study, a cohort enrolling three biologically related generations of women in family units, which was constructed in Huai'an City, Jiangsu Province, China. Huai'an City, located in eastern China, had a permanent population of approximately 4.6 million in 2020, with 65.7% living in urban areas, reflecting a level of urbanization comparable to the national average (above 60%). The per capita gross domestic product (GDP) was 87,507 Chinese Yuan (CNY), modestly above the national average of 72,447 CNY in the same year. Initially, we enrolled all pregnant women (n = 27,923) who gave live birth between July 1, 2020, and June 30, 2021, in Huai'an and collected their basic characteristics and health-related information during pregnancy through linkage to the Maternity Information System (MIS).19 In 2023, a random sample of 2,242 women (G1 generation) from the initial cohort was invited to participate in follow-up surveys, and their biological mothers (G0 generation) and daughters (G2 generation, born between July 1, 2020 and June 30, 2021) were also enrolled in the cohort (Fig. 1a). The distribution of samples in the GMATCH cohort by county/district was similar to that of the total population (Figure S1). Touchscreen questionnaire interviews were conducted to collect information on sociodemographic characteristics, early-life factors, lifestyle behaviors, female-specific reproductive factors, and health status.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of study design and population selection process. (a) Study design of GMATCH cohort. (b) The design framework of the current study. (c) The selection process of study population.

In the current study, two generations of women in mother-offspring pairs (G0 and G1) from GMATCH were included as the study population (n = 2,242 dyads) (Fig. 1b). The exclusion criteria included (1) mothers who withdrew from GMATCH (n = 9), (2) offspring with multiple pregnancies in 2020/2021 (n = 38), (3) offspring who gave birth again between 2020/2021 and 2023 (n = 230), (4) offspring diagnosed with anxiety or depression before pregnancy in 2020/2021 (n = 15), and (5) offspring who were less than 18 years of age when pregnant in 2020/2021 (n = 19). A total of 1,931 mother-offspring dyads were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1c).

Assessment of adverse childhood experiences

The history of ACEs was retrospectively collected using a brief questionnaire modified with reference to the Childhood Trauma Screener (CTS).20 The questionnaire assessed ACEs with five questions representing emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect: (1) Did a parent or other adult in the household often swear at you, insult you, put you down, or humiliate you, or act in a way that made you afraid that you might be physically hurt? (2) Did a parent or other adult in the household often push, grab, slap, or throw something at you, or ever hit you so hard that you had marks or were injured? (3) Did an adult or person at least 5 years older than you ever touch or fondle you, or have you touch their body in a sexual way, or try to or actually have oral, anal, or vaginal sex with you? (4) Did you often feel that no one in your family loved you or thought you were important or special, or that your family didn't look out for each other, feel close to each other, or support each other? (5) Did you often feel that you didn't have enough to eat, had to wear dirty clothes, and had no one to protect you, or that your parents were too drunk or high to take care of you or take you to the doctor if you needed it? For each ACE subtype, participants reported the relevant histories, which were dichotomized as 1. We also constructed a summary score of the five subtypes, ranging from 0 to 5, with a higher score denoting more ACEs.

Assessment of offspring's perinatal mental health

Offspring's perinatal mental health, including anxiety and depression, was measured at three time points: during pregnancy, one year after childbirth, and three years after childbirth. For the assessment during pregnancy and one year after childbirth, participants were asked to retrospectively report any diagnosis or symptoms of anxiety or depression using the following four questions for each period: (1) “Were you diagnosed with anxiety?” (response options: yes or no); (2) “Did you experience symptoms of anxiety?” (response options: never, occasionally, sometimes, or always); (3) “Were you diagnosed with depression?” (response options: yes or no); (4) “Did you experience symptoms of depression?” (response options: never, occasionally, sometimes, or always). Participants who answered “yes” to the diagnostic question or “sometimes” or “always” to the symptom question were classified as having symptoms of anxiety or depression, respectively. For the assessment of mental health within three years after childbirth, anxious symptoms were assessed using the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7),21 and depressive symptoms were assessed using the 10-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10).22 Participants with scores of 10 or greater on the GAD-7 or CESD-10 were classified as having anxious or depressive symptoms, respectively. Both scales have been validated and widely used in Chinese adults.23,24 Mental disorders were defined as the presence of either anxious or depressive symptoms.

Covariates

Covariates assessed in this study included the mothers' and offspring's age, residence region (urban or rural), self-reported family socioeconomic status (SES) before 18 years old (low, medium, or high), employment status (employed or unemployed), annual household income (low, lower-middle, upper-middle, or high), number of siblings, number of children, mothers' educational level (below primary school, primary school, secondary school, technical secondary school and above), and offspring's educational level (secondary school and below, high school and technical secondary school, junior college, bachelor's degree and above). Mothers' and offspring's annual household income was categorized into quartiles as low (quartile 1, the lowest quartile), lower-middle (quartile 2), upper-middle (quartile 3), and high (quartile 4, the highest quartile). Since the mothers' number of children and the offspring's number of siblings were highly correlated, we only adjusted for the offspring's number of siblings in the statistical models.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of participants were described as mean with standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables, according to the history of mothers' and offspring's ACEs. Students' t tests and χ2 tests were used to compare between-group differences.

We used logistic regression models to assess the association of mothers' ACEs and specific ACEs subtypes with offspring's exposures to ACEs, adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics of mothers (residence region, family SES before 18 years old, educational level, employment status, number of siblings) and offspring (family SES before age 18 years, number of siblings). Subsequently, univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were conducted to assess the associations of mothers' and offspring's ACEs, the summed score of ACEs, and specific ACEs subtypes with offspring's mental disorders during pregnancy, one year after childbirth, and three years after childbirth. The aforementioned covariates, in addition to offspring's educational level, employment status, annual household income, and number of children, were adjusted for in the models. For the models of mental disorders after childbirth, the mental disorders occurring at previous time points were also adjusted for. The specific associations of mothers' and offspring's ACEs with offspring's perinatal anxious and depressive symptoms were also assessed using logistic regression models.

A structural equation model (SEM) was then conducted to explore the underlying pathways through which mothers' ACEs link to offspring's mental disorders (Figure S2). Specific ACEs subtypes and symptoms of anxiety and depression were used as indicators for the latent constructs of ACEs and mental disorders, respectively. The following parameters were used to assess model fit: chi-square ratio (χ2/df) ≤3.00, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤0.08, and comparative fit index (CFI) ≥0.95. Given the dichotomous nature of the variables, Weighted Least Squares Mean and Variance Adjusted Estimation (WLSMV) was conducted with 1000 bootstrap samples. Significant indirect effects were considered when the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval (CI) did not include 0. The SEM model was adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics of mothers (age, educational level) and offspring (family SES before age 18 years, educational level, household income, number of children).

A series of additional analyses were conducted to test the robustness of the results. First, subgroup analyses were performed to examine the associations of mothers' and offspring's ACEs with offspring's mental disorders, stratified by sociodemographic characteristics of both generations (i.e., age, residence region, educational level, employment status of mothers and offspring, offspring's household income, and number of siblings and children). An additional subgroup analysis assessed the associations between the type of ACEs (abuse vs. neglect) in both generations and offspring's mental disorders. In this analysis, the abuse group included emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, while the neglect group included emotional and physical neglect. Subsequently, two sensitivity analyses were conducted. One analysis redefined anxious and depressive symptoms during pregnancy and one year after childbirth as self-reported “always” having the symptoms. Another analysis excluded offspring who had mental health outcomes during pregnancy to test the association between ACEs and mental health outcomes at one year and three years after childbirth. In this restricted sample, the SEM was also re-estimated to test the robustness of the pathway results.

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported in this study. Statistical significance was set as P value < 0.05 in a two-tailed test. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., NC, USA), the R package “ggplot2” using for visualization, and Mplus (version 8.3).

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Yangzhou University Huai'an Maternal and Child Health Care Center (Approval Number: 2019056 & 2023030). All participants provided written informed consent.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

Baseline characteristics of participants according to the history of ACEs are presented in Table 1. A total of 1931 mother-offspring dyads were included in this study, of which 367 mothers (19.0%) and 271 offspring (14.0%) reported a history of ACEs. The most prevalent ACE subtype was physical neglect (13.4%) for mothers and emotional neglect (7.7%) for offspring (Table S1). Mothers with a history of ACEs were more likely to be older, have lower family SES before the age of 18, less education, lower household income at baseline, and more children and siblings compared to those without ACEs. Offspring with a history of ACEs tended to have lower family SES before the age of 18. A total of 467 (24.2%), 405 (21.0%), and 226 (11.7%) offspring had mental disorders during pregnancy, one year after childbirth, and three years after childbirth, respectively (Table S2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the two generations according to the history of adverse childhood experiences.

| Characteristics | Mothers, n (%) |

Offspring, n (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 1931) | With ACEs (n = 367) | Without ACEs (n = 1564) | P value | Total (n = 1931) | With ACEs (n = 271) | Without ACEs (n = 1660) | P value | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 56.7 (6.2) | 58.2 (6.6) | 56.4 (6.0) | <0.001 | 31.6 (4.4) | 31.3 (4.5) | 31.7 (4.4) | 0.220 |

| Residence | 0.164 | 0.473 | ||||||

| Urban | 974 (50.4) | 173 (47.1) | 801 (51.2) | 1439 (74.5) | 206 (76.0) | 1233 (74.3) | ||

| Rural | 957 (49.6) | 194 (52.9) | 763 (48.8) | 492 (25.5) | 65 (24.0) | 427 (25.7) | ||

| Family SES before age 18 years | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Low | 1168 (60.5) | 300 (81.7) | 868 (55.5) | 469 (24.3) | 114 (42.1) | 355 (21.4) | ||

| Middle | 636 (32.9) | 56 (15.3) | 580 (37.1) | 1219 (63.1) | 138 (50.9) | 1081 (65.1) | ||

| High | 127 (6.6) | 11 (3.0) | 116 (7.4) | 243 (12.6) | 19 (7.0) | 224 (13.5) | ||

| Educational levela | <0.001 | 0.224 | ||||||

| Low | 728 (37.7) | 182 (49.6) | 546 (34.9) | 610 (31.6) | 84 (31.0) | 526 (31.7) | ||

| Lower middle | 534 (27.7) | 91 (24.8) | 443 (28.3) | 342 (17.7) | 51 (18.8) | 291 (17.5) | ||

| Upper middle | 507 (26.3) | 77 (21.0) | 430 (27.5) | 424 (22.0) | 48 (2.5) | 376 (19.5) | ||

| High | 162 (8.4) | 17 (4.6) | 145 (9.3) | 555 (28.7) | 88 (32.5) | 467 (28.1) | ||

| Employment status | 0.756 | 0.357 | ||||||

| Employed | 1318 (68.3) | 248 (67.6) | 1070 (68.4) | 1307 (67.7) | 190 (70.1) | 1117 (57.9) | ||

| Housewife or unemployed | 613 (31.8) | 119 (32.4) | 494 (31.6) | 624 (32.3) | 81 (29.9) | 543 (32.7) | ||

| Household income | 0.006 | 0.886 | ||||||

| Lower | 510 (26.4) | 118 (32.2) | 392 (25.1) | 424 (22.0) | 58 (21.4) | 366 (22.1) | ||

| Lower middle | 491 (25.4) | 84 (22.9) | 407 (26.0) | 476 (24.7) | 72 (26.6) | 404 (24.3) | ||

| Upper middle | 475 (24.6) | 97 (26.4) | 378 (24.2) | 503 (26.1) | 68 (25.1) | 435 (26.2) | ||

| High | 455 (23.6) | 68 (18.5) | 387 (24.7) | 528 (27.3) | 73 (26.9) | 455 (27.4) | ||

| Number of siblings, mean (SD) | 4.6 (1.6) | 4.9 (1.7) | 4.5 (1.6) | <0.001 | 2.2 (1.0) | 2.3 (1.1) | 2.2 (1.0) | 0.130 |

| Number of children, mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.4 (1.1) | 2.3 (1.0) | 0.007 | 1.6 (0.6) | 1.6 (0.6) | 1.6 (0.6) | 0.292 |

The values in bold in the analysis results represent statistically significant differences.

Mothers' educational levels were classified as follows: low (below primary school), low-middle (primary school), middle–high (secondary school), and high (technical secondary school and above). Corresponding classifications for offspring: secondary school and below, high school and technical secondary school, junior college, and bachelor's degree or above.

Intergenerational association between mothers' and offspring's ACEs

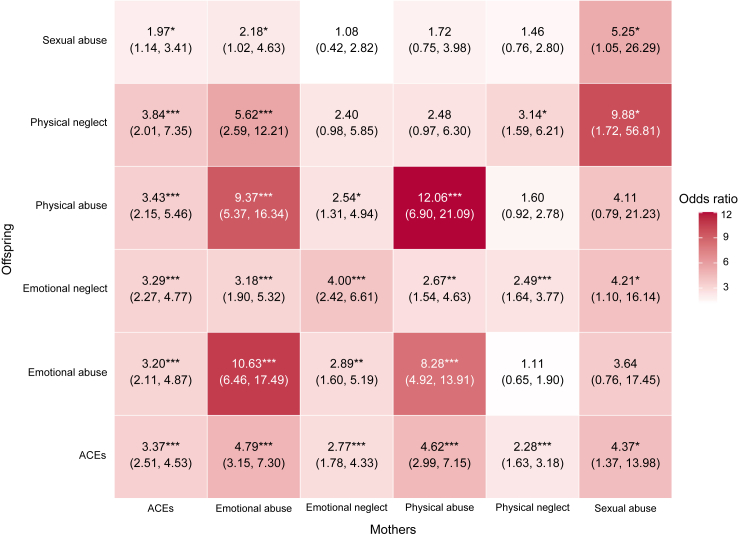

The associations between mothers' and offspring's exposures to ACEs are presented in Fig. 2. Offspring of mothers with a history of ACEs were more likely to be exposed to ACEs themselves (OR = 3.37, 95% CI: 2.51–4.53). For specific ACE subtypes, intergenerational associations were also observed. For example, mothers' exposure to emotional abuse was associated with increased odds of all ACE subtypes in their offspring, including emotional abuse (OR = 10.63, 95% CI: 6.46–17.49), emotional neglect (OR = 3.18, 95% CI: 1.90–5.32), physical abuse (OR = 9.37, 95% CI: 5.37–16.34), physical neglect (OR = 5.62, 95% CI: 2.59–12.21), and sexual abuse (OR = 2.18, 95% CI: 1.02–4.63). When examining intergenerational associations within the same ACE subtypes, offspring of mothers exposed to emotional abuse, emotional neglect, physical abuse, physical neglect, or sexual abuse had 10.63-fold (95% CI: 6.46–17.49), 4.00-fold (95% CI: 2.42–6.61), 12.06-fold (95% CI: 6.90–21.09), 3.14-fold (95% CI: 1.59–6.21), or 5.25-fold (95% CI: 1.05–26.29) increased odds of being exposed to the same subtypes, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Intergenerational association between mothers' ACEs and offspring's ACEs. Offspring's ACEs and their subtypes were dependent variables, while mothers' ACEs and their subtypes were independent variables. The ORs and their 95% CIs were calculated. The results were adjusted for mothers' sociodemographic characteristics (residence region, family SES before age 18 years, educational level, employment status, number of siblings) and offspring's sociodemographic characteristics (family SES before age 18 years, number of siblings). P < 0.0001. ∗∗P < 0.001. ∗P < 0.05. ACEs, adverse childhood experiences; SES, socioeconomic status.

Associations of mothers' and offspring's ACEs with offspring's perinatal mental disorders

As shown in Table 2, mothers' ACEs were associated with higher odds of offspring's mental disorders during pregnancy (OR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.05–1.80) and one year after childbirth (OR = 1.46, 95% CI: 1.07–1.99). We also observed a dose–response relationship between the summed score of mothers' ACEs and offspring's perinatal mental disorders. For example, the odds of offspring experiencing mental disorders one year after childbirth increased from 1.05 (95% CI: 0.71–1.54) for mothers with 1 ACE to 2.56 (95% CI: 1.62–4.04) for mothers with two or more ACEs. Similar results were observed for specific ACEs subtypes.

Table 2.

Associations of mothers' ACEs and offspring's ACEs, with offspring's mental disorders during pregnancy, one year and three years after childbirth.

| During pregnancy |

One year after childbirtha |

Three years after childbirthb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case (%) | OR (95% CI) | Case (%) | OR (95% CI) | Case (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Mothers | ||||||

| History of ACEs | ||||||

| 0 | 361 (23.1) | Ref. | 307 (19.6) | Ref. | 169 (10.8) | Ref. |

| ≥1 | 106 (28.9) | 1.37 (1.05–1.80) | 98 (26.7) | 1.46 (1.07–1.99) | 57 (15.5) | 1.35 (0.93–1.97) |

| Summed score of ACEs | ||||||

| 0 | 361 (23.1) | Ref. | 307 (19.6) | Ref. | 169 (10.8) | Ref. |

| 1 | 65 (27.4) | 1.31 (0.95–1.81) | 49 (20.7) | 1.05 (0.71–1.54) | 33 (13.9) | 1.39 (0.89–2.19) |

| ≥2 | 41 (31.5) | 1.49 (0.99–2.24) | 49 (37.7) | 2.56 (1.62–4.04) | 24 (18.5) | 1.30 (0.75–2.26) |

| P for trend | 0.019 | <0.001 | 0.147 | |||

| Subtype of ACEs | ||||||

| Emotional abuse | 36 (32.1) | 1.48 (0.97–2.27) | 43 (38.4) | 2.48 (1.54–3.97) | 19 (17.0) | 1.47 (0.86–2.51) |

| Physical abuse | 36 (34.6) | 1.66 (1.08–2.56) | 36 (34.6) | 1.93 (1.17–3.19) | 18 (17.3) | 1.50 (0.87–2.60) |

| Sexual abuse | 8 (61.5) | 5.70 (1.81–17.97) | 8 (61.5) | 4.96 (1.34–18.41) | 3 (23.1) | 2.85 (0.75–10.88) |

| Emotional neglect | 36 (33.3) | 1.52 (0.99–2.34) | 36 (33.3) | 1.74 (1.06–2.85) | 24 (22.2) | 2.29 (1.39–3.79) |

| Physical neglect | 65 (25.1) | 1.06 (0.77–1.47) | 57 (22.0) | 1.09 (0.75–1.58) | 36 (13.9) | 1.35 (0.89–2.03) |

| Offspring | ||||||

| History of ACEs | ||||||

| 0 | 366 (22.1) | Ref. | 299 (18.0) | Ref. | 158 (9.5) | Ref. |

| ≥1 | 101 (37.3) | 2.05 (1.54–2.72) | 106 (39.1) | 2.41 (1.75–3.33) | 68 (25.1) | 2.30 (1.58–3.33) |

| Summed score of ACEs | ||||||

| 0 | 366 (22.1) | Ref. | 299 (18.0) | Ref. | 158 (9.5) | Ref. |

| 1 | 54 (34.2) | 1.82 (1.27–2.60) | 50 (31.7) | 1.70 (1.12–2.56) | 32 (20.3) | 2.03 (1.26–3.27) |

| ≥2 | 47 (41.6) | 2.41 (1.60–3.62) | 56 (49.6) | 3.87 (2.45–6.11) | 36 (31.9) | 2.66 (1.61–4.40) |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Subtype of ACEs | ||||||

| Emotional abuse | 42 (38.2) | 1.95 (1.29–2.95) | 51 (46.4) | 3.23 (2.03–5.12) | 31 (28.2) | 3.17 (2.00–5.04) |

| Physical abuse | 34 (37.8) | 1.88 (1.19–2.97) | 42 (46.7) | 3.28 (1.96–5.47) | 24 (26.7) | 2.70 (1.61–4.55) |

| Sexual abuse | 28 (40.6) | 1.97 (1.19–3.27) | 27 (39.1) | 1.83 (1.04–3.24) | 20 (29.0) | 3.21 (1.82–5.64) |

| Emotional neglect | 52 (35.1) | 1.73 (1.20–2.49) | 58 (39.2) | 2.39 (1.59–3.60) | 42 (28.4) | 3.41 (2.26–5.12) |

| Physical neglect | 19 (43.2) | 2.40 (1.28–4.51) | 19 (43.2) | 2.38 (1.19–4.77) | 16 (36.4) | 5.08 (2.59–9.97) |

Model was adjusted for mothers' sociodemographic characteristics (age, residence region, family SES before 18 years old, educational level, employment status, household income, number of siblings) and offspring's sociodemographic characteristics (age, residence region, family SES before 18 years old, educational level, employment status, household income, number of siblings and children). The values in bold in the analysis results represent statistically significant differences.

ACEs, adverse childhood experiences; SES, socioeconomic status.

Additionally adjusted for mental disorders during pregnancy.

Additionally adjusted for mental disorders pregnancy and one year after childbirth.

Additionally, offspring's ACEs were associated with higher odds of mental disorders during their perinatal period, including during pregnancy (OR = 2.05, 95% CI: 1.54–2.72), one year after childbirth (OR = 2.41, 95% CI: 1.75–3.33), and three years after childbirth (OR = 2.30, 95% CI: 1.58–3.33). Dose–response relationships were also found between offspring's summed score of ACEs and perinatal mental disorders. For example, the odds of mental disorders one year after childbirth increased from 1.70 (95% CI: 1.12–2.56) for offspring with 1 ACE to 3.87 (95% CI: 2.45–6.11) for offspring with two or more ACEs. Such associations were observed for specific ACE subtypes.

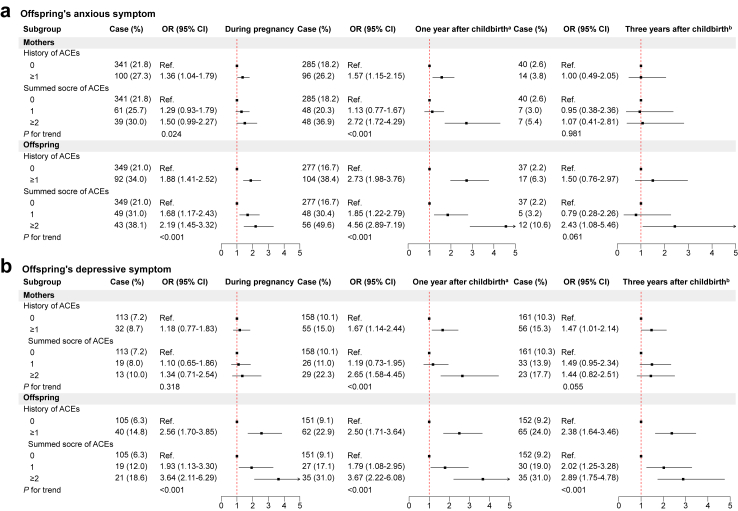

Similar results were observed for associations of mothers' and offspring's ACEs with offspring's anxious and depressive symptoms (Fig. 3 & Table S3).

Fig. 3.

Associations of mothers' and offspring's ACEs with offspring's anxious symptom (a) and depressive symptom (b) during pregnancy, one year and three years after childbirth. Model was adjusted for mothers' sociodemographic characteristics (age, residence region, family SES before age 18 years, educational level, employment status, household income, number of siblings) and offspring's sociodemographic characteristics (age, residence region, family SES before age 18 years, educational level, employment status, household income, number of siblings and children). a additionally adjusted for anxious or depressive symptom during pregnancy. b additionally adjusted for anxious or depressive symptom during pregnancy and one year after childbirth. ACEs, adverse childhood experiences; SES, socioeconomic status.

The role of offspring's ACEs in the association between mothers' ACEs and offspring's perinatal mental disorders

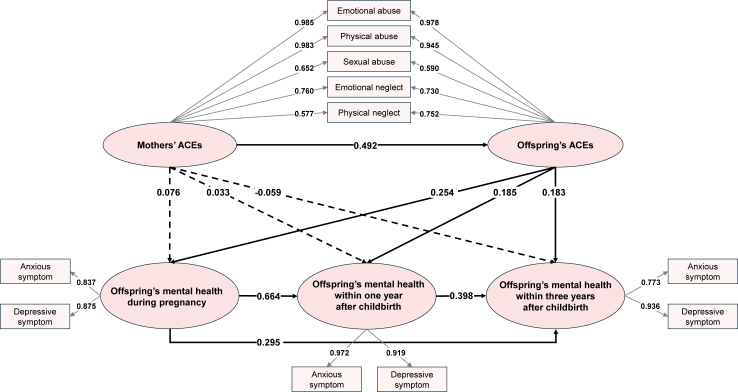

The fit indices for the SEM indicated a good fit (Fig. 4 & Table S4, χ2/df = 2.14, CFI = 0.987, RMSEA = 0.024). According to the SEM, the direct associations between mothers' ACEs and offspring's perinatal mental disorders were relatively weak (b = 0.076, P = 0.412 for mental disorders during pregnancy; b = 0.033, P = 0.674 for mental disorders one year after childbirth; b = −0.059, P = 0.458 for mental disorders three years after childbirth). We observed that the association between mothers' ACEs and offspring's mental disorders might be mainly mediated by offspring's ACEs. When considering the timing sequence of offspring's mental disorders, we found a serial mediating pathway through which the effect of mothers' ACEs on offspring's mental disorders within three years after childbirth was mediated by offspring's ACEs, offspring's mental disorders during pregnancy and one year after childbirth.

Fig. 4.

Pathways of mothers' ACEs on offspring's mental health from pregnancy to three years after childbirth. Standardized coefficients were presented. Solid lines indicate paths with statistical significance, and dashed lines indicate paths with no statistical significance.

Additional analyses

Subgroup analyses suggested that the associations between mothers' ACEs and offspring's mental health were more pronounced among populations with lower SES. Specifically, the associations were stronger among mothers residing in rural areas, offspring residing in rural areas, and offspring with lower educational levels (Table S5). Additionally, the associations between offspring's own ACEs and mental health were significant across all three periods in each subgroup (Table S6), consistent with the main results. When ACEs were categorized into abuse and neglect groups, mothers' exposure to abuse was associated with an increased risk of offspring's mental disorders during pregnancy and one year after childbirth (Table S7). No significant associations were observed in the neglect group of mothers. Meanwhile, both abuse and neglect in the offspring were significantly associated with mental disorders across all three time points (Table S7). Sensitivity analyses, in which anxious and depressive symptoms during pregnancy and one year after childbirth were redefined, yielded results similar to the main findings (Table S8). When offspring with mental health outcomes during pregnancy were excluded, mothers' ACEs remained significantly associated with offspring's mental health at one year after childbirth, and offspring's ACEs also remained significantly associated with mental health outcomes at both one and three years after childbirth (Table S9). Furthermore, SEM results from the restricted sample confirmed the mediating role of offspring's ACEs in the association between mothers' ACEs and offspring's mental health (Figure S3), consistent with the primary findings.

Discussion

Using data from two generations of women in the GMATCH cohort, our study revealed that offspring of mothers with ACEs were at higher risk of experiencing ACEs themselves. Both mothers' and offspring's ACEs were associated with increased odds of offspring's mental disorders during pregnancy, one year, and three years after childbirth. SEM analysis revealed that offspring's ACEs mediated the association between mothers' ACEs and offspring's mental health. These findings enhance our understanding of the long-term health impact of ACEs across multiple generations.

In our study, 19.0% of mothers and 14.0% of offspring reported a history of ACEs. The prevalence was lower than the estimated prevalence in other countries, such as the US and Sweden (ranging from 38.6% to 61.55%).25, 26, 27 This discrepancy may be partly explained by differences in study population, as well as cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds across different countries or regions. For example, the emphasis on endurance and resilience in Chinese culture may lead to the underreporting of less severe adverse experiences.28,29 A recent nationwide cross-sectional study reported that the prevalence of ACEs in adults across China was estimated to be 27.1%.30 The lower prevalence in our study compared to the nationwide estimate might be due to differences in measurement methods; our study only included five subtypes of ACEs, potentially underestimating the prevalence. Another possible reason could be that our study was conducted in Huai'an, Jiangsu Province, a city with a middle-to upper-level SES compared to other regions in China. Socioeconomic variations may also explain the difference in prevalence.

Our findings support the cycle of maltreatment hypothesis by demonstrating an intergenerational association of ACEs across two generations of women in China. Moreover, we observed a stronger association (OR = 3.37) compared to a longitudinal randomized controlled trial in the US (OR = 2.52, n = 417),31 as well as a modest association reported in a systematic review (median n = 222).9 These variations may be partly explained by the larger sample size (n = 1931) in our study, as well as differences in study populations, cultural factors, and social contexts across different countries. Additionally, each ACEs subtype exhibited a significant intergenerational link between the two generations, which aligns with previous findings.9 Our results, in conjunction with prior evidence, highlight the importance of intervention strategies that target not only individuals directly exposed to ACEs but also the intergenerational cycles of exposure within families.

In the current study, individuals directly exposed to ACEs were at increased risk of mental disorders during pregnancy and after childbirth. This finding is aligned with prior research that reported similar associations between ACEs and mental health at specific time points during the perinatal period.32, 33, 34, 35 For example, a cohort study found that women exposed to ACEs were more likely to experience major depressive episodes during pregnancy.33 Another cross-sectional study of 500 women found a significant association between physical and sexual abuse and postpartum mental disorders.35 Our study extended the influence of ACEs beyond a specific time point during the perinatal period by utilizing repeated measurement of mental disorders in the GMATCH cohort. Our results indicated that the health effects of ACEs persist from pregnancy to years after childbirth, underscoring the need for continued mental health surveillance for pregnant women beyond pregnancy, especially for those with a history of ACEs.

Beyond the health effects of ACEs on individuals who were directly exposed, our study provides further insights into the intergenerational associations between mothers' ACEs and offspring's perinatal mental health. While previous studies have highlighted the intergenerational association between mothers' ACEs and offspring's early-life health outcomes,36, 37, 38 our study extends this understanding by confirming that such associations can persist into offspring's adulthood.

For the potential mechanisms linking mothers' ACEs and offspring's health consequences, prior research suggests that mothers' mental health39 and parenting practices40 may mediate the link between ACEs and the next generations' mental health outcomes or behavioral problems. Early childhood, particularly the first three years of life, is a critical developmental period during which biological systems are highly susceptible to negative external influences.17 Exposure to stressors, such as poor parenting following ACEs,41 can lead to maladaptive or toxic responses, disrupting the neuroendocrine and immune systems and laying the foundation for long-term health issues. Furthermore, sex differences in the early-life programming of the HPA axis, especially in females during early childhood,42 contribute to a greater vulnerability to the effects of ACEs. In line with these findings, our study showed that female offspring's ACEs mediated the association between mothers' ACEs and offspring's perinatal mental health, even when excluding offspring with pre-existing mental health issues during pregnancy. Similarly, a cohort study of 398 Latino families identified offspring's ACEs as a mediator linking mothers' ACEs to offspring's psychological issues in young adulthood.43 A longitudinal study with a 21-year follow-up in the US revealed that offspring's ACEs accounted for 30.3% of the association between mothers' ACEs and offspring's mental health from adolescence to young adulthood.44 Taken together, these pathways suggest that breaking the intergenerational cycle of ACEs may reduce the risk of mental illness in adult female offspring, particularly by focusing on sensitive developmental windows.

Aside from the above-mentioned pathways, several other mechanisms may also contribute to the intergenerational association between mothers' ACEs and offspring's mental health. For example, the shared genetic liabilities associated with the susceptibility to stress and psychological illness following ACEs across multiple generations may explain the intergenerational associations.45 Moreover, the environmental consequences of mothers' ACEs, such as mental health issues, lower SES, and disadvantaged caregiving, may foster insecure attachment in offspring, further increasing their vulnerability to similar health issues following adversities.46, 47, 48 Our subgroup analysis showed that the intergenerational association was more pronounced among those with low SES, particularly among those living in rural areas or with lower educational levels. Limited healthcare access, economic stress, and lower social support may heighten offspring's vulnerability to subsequent health issues.47 Notably, when ACEs were classified into abuse and neglect, only mothers' exposure to abuse was associated with offspring's perinatal mental health. One possible explanation is that, in cases of neglect, female offspring might still grow up in families that offer perceived safety and stability, which could mitigate long-term psychological harm. Furthermore, gene–environmental interactions may further shape such intergenerational associations.49 Future research is warranted to use genetic data to disentangle the complex interactions between genetic and environmental factors in these associations.

Implications

Our findings have important implications for long-term public health strategies. First, integrating ACEs screening into routine perinatal care can help identify high-risk women by assessing ACEs exposure in both pregnant women and their mothers. For these women, mental health surveillance should extend beyond pregnancy and the immediate postpartum period, lasting at least three years, and ideally throughout their life course. Second, family-based prevention and intervention initiatives targeting women's mental health should be promoted, particularly for families where grandmothers or mothers experienced early-life adversities. Moreover, breaking the cycle of ACEs is essential to reducing the risk of mental health problems in the next generation. Specifically, healthcare providers should focus on families with positive ACEs screening results during perinatal care, offering family-based parenting education to support children's socio-emotional development and reduce the risk of ACEs continuity.50

ACEs screening among pregnant women has not been widely implemented in antenatal care; some pilot studies have demonstrated its feasibility and acceptability for both healthcare providers and pregnant women.51 In China, approaches should focus on improving both the reporting rate and accuracy, which may be influenced by cultural factors like an emphasis on endurance and resilience. First, a trauma-informed approach should be integrated into routine maternal health assessments,52 along with an introductory letter explaining the survey process. Second, healthcare providers should receive training to enhance their confidence and skills in addressing sensitive topics.51 Third, creating a supportive and culturally safe environment for disclosure (e.g., private examination rooms)53 and using a minimum set of standardized questions are essential. Additionally, incorporating objective measures, such as medical records and clinical assessments, could further improve data accuracy. Before implementing ACEs screening, multiple pilot programs should be conducted to assess the acceptability of the process and identify the best practices.

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of this study include the enrollment of two generations of women within family units, allowing for the exploration of the intergenerational associations of ACEs with health outcomes. Through the SEM analysis, we could explore the pathways linking mothers' ACEs, offspring's ACEs, and offspring's mental health.

There are several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, ACEs were self-reported retrospectively, which is vulnerable to recall bias. However, retrospective reporting of ACEs is a recognized approach, and a meta-analysis found no differences in associations between retrospective and prospective ACEs measures and mental health outcomes.54 Moreover, some individuals may be reluctant to disclose their ACEs or mental health problems, which could lead to an underestimation of the prevalence of ACEs and mental disorders in the current study. Second, ACEs were measured using five subtypes, and other forms of adversity, such as family dysfunction, were not included. While this may limit the comprehensiveness of the ACEs assessment, focusing on a subset of ACEs may reduce potential dilution effects and allow for a clearer examination of their intergenerational impact. A more comprehensive measurement of ACEs could be considered in future studies. Third, using simple questions to assess diagnosis or symptoms of anxiety and depression during pregnancy and one year after childbirth may lead to inaccurate evaluations. Although simple self-report measures have been validated as reliable indicators of anxiety and depression in previous studies,55,56 future research with standardized and repeated assessments across multiple time points is warranted. Fourth, this study lacks data on fathers' ACEs and mental health status, which are also important factors that might contribute to the intergenerational associations. Future research with comprehensive data on both maternal and paternal information is needed. Fifth, due to the retrospective study design, we lacked data on mothers' (G0 generation) mental health during the postpartum period, as well as on parenting behaviors, which have been shown to influence the association between mothers' ACEs and offspring's health. Additionally, genetic factors and their interactions with environmental factors are not assessed in this study. Last, our study was conducted with a Chinese female population, so the findings may not be generalizable to populations in other cultural or policy contexts or to male offspring. However, this focused approach provides valuable insights into the intergenerational impacts within the female group. Future research should include both male and female offspring to assess potential sex-specific moderating effects.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study suggests a significant intergenerational association between mothers' ACEs and offspring's ACEs exposures, both of which are linked to an increased risk of mental disorders during the perinatal period and up to three years after childbirth in female offspring. Importantly, offspring's own ACEs mediate the association between mothers' ACEs and offspring's mental health outcomes. Our findings emphasize that breaking the intergenerational cycle of ACEs and reducing ACEs among Chinese women has the potential for significant improvements in mental health across generations, ultimately alleviating the long-term societal burden of mental disorders. Early and integrated family-based interventions targeting both mothers and their children are crucial for preventing the continuity of ACEs and mental disorders.

Contributors

Xiaolin Xu contributed to the study conceptualization and supervised the whole project. Xiaolin Xu and Xiaoqin Zhu are the principal investigators and are responsible for GMATCH. Hui Wang contributed to the conceptualization of the study, data acquisition, and the statistical analysis, and drafted an initial version of the manuscript. Yue Zhang contributed to specification of the statistical analysis, and manuscript revision. Weijie Ding and Jiyue Dai contributed to the data acquisition. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript. Xiaolin Xu and Xiaoqin Zhu are the corresponding authors, have full access to all the data, and have final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Data sharing statement

The data of GMATCH are not available for sharing.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We thank all interviewers and staff for the implementation and quality control of the study.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: This summary is available in Chinese in the Supplementary Material.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2025.101579.

Contributor Information

Xiaoqin Zhu, Email: zhuxiaoqinha@yzu.edu.cn.

Xiaolin Xu, Email: xiaolin.xu@zju.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Ma X., Biaggi A., Sacchi C., et al. Mediators and moderators in the relationship between maternal childhood adversity and children's emotional and behavioural development: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2022;52(10):1817–1837. doi: 10.1017/S0033291722001775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Lancet Public Health Childhood adversity: a profound determinant of health. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(11) doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson C.A., Scott R.D., Bhutta Z.A., et al. Adversity in childhood is linked to mental and physical health throughout life. BMJ. 2020;371 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dempster K.S., O'Leary D.D., MacNeil A.J., Hodges G.J., Wade T.J. Linking the hemodynamic consequences of adverse childhood experiences to an altered HPA axis and acute stress response. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;93:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bale T.L., Epperson C.N. Sex differences and stress across the lifespan. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(10):1413–1420. doi: 10.1038/nn.4112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gifford R.M., Reynolds R.M. Sex differences in early-life programming of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in humans. Early Hum Dev. 2017;114:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almuneef M., ElChoueiry N., Saleheen H.N., Al-Eissa M. Gender-based disparities in the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult health: findings from a national study in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):90. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0588-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thornberry T.P., Knight K.E., Lovegrove P.J. Does maltreatment beget maltreatment? A systematic review of the intergenerational literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2012;13(3):135–152. doi: 10.1177/1524838012447697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madigan S., Cyr C., Eirich R., et al. Testing the cycle of maltreatment hypothesis: meta-analytic evidence of the intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment. Dev Psychopathol. 2019;31(1):23–51. doi: 10.1017/S0954579418001700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moog N.K., Cummings P.D., Jackson K.L., et al. Intergenerational transmission of the effects of maternal exposure to childhood maltreatment in the USA: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2023;8(3):e226–e237. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00025-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le-Scherban F., Wang X., Boyle-Steed K.H., Pachter L.M. Intergenerational associations of parent adverse childhood experiences and child health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts A.L., Lyall K., Rich-Edwards J.W., Ascherio A., Weisskopf M.G. Association of maternal exposure to childhood abuse with elevated risk for autism in offspring. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(5):508–515. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun J., Patel F., Rose-Jacobs R., et al. Mothers' adverse childhood experiences and their young children's development. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(6):882–891. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolhuis K., Steenkamp L.R., Tiemeier H., et al. A prospective cohort study on the intergenerational transmission of childhood adversity and subsequent risk of psychotic experiences in adolescence. Schizophr Bull. 2023;49(3):799–808. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbac195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang N.R., Kwack Y.S., Song J.K., et al. The impact of maternal adverse childhood experiences on offspring's internalizing and externalizing problems. Psychiatry Investig. 2021;18(11):1050–1057. doi: 10.30773/pi.2021.0343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Q., Xia M., Zeng D., et al. Development of segregation and integration of functional connectomes during the first 1,000 days. Cell Rep. 2024;43(5) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bucci M., Marques S.S., Oh D., Harris N.B. Toxic stress in children and adolescents. Adv Pediatr. 2016;63(1):403–428. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers A., Obst S., Teague S.J., et al. Association between maternal perinatal depression and anxiety and child and adolescent development: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(11):1082–1092. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y., Ding W., Dai X., et al. Burden of multiple high-risk factors in pregnancy before and after the universal two-child policy in Chinese women: an observational study. J Glob Health. 2024;14 doi: 10.7189/jogh.14.04134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grabe H.J., Schulz A., Schmidt C.O., et al. [A brief instrument for the assessment of childhood abuse and neglect: the childhood trauma screener (CTS)] Psychiatr Prax. 2012;39(3):109–115. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1298984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B., Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andresen E.M., Malmgren J.A., Carter W.B., Patrick D.L. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gong Y., Zhou H., Zhang Y., et al. Validation of the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7) as a screening tool for anxiety among pregnant Chinese women. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng S.T., Chan A.C. The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale in older Chinese: thresholds for long and short forms. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(5):465–470. doi: 10.1002/gps.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessler R.C., McLaughlin K.A., Green J.G., et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO world mental health surveys. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(5):378–385. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merrick M.T., Ford D.C., Ports K.A., Guinn A.S. Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011-2014 behavioral risk factor surveillance system in 23 states. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(11):1038–1044. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Danielsdottir H.B., Aspelund T., Shen Q., et al. Adverse childhood experiences and adult mental health outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81(6):586–594. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen R. Adverse childhood experiences, their co-occurrence profiles, and mental disorders in adults in China. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2025;55 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2025.101478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie Q., Wong D.F.K. Culturally sensitive conceptualization of resilience: a multidimensional model of Chinese resilience. Transcult Psychiatry. 2021;58(3):323–334. doi: 10.1177/1363461520951306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu P., Liu Z., Xu Y., et al. The prevalence and profiles of adverse childhood experiences and their associations with adult mental health outcomes in China: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2024;53 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2024.101253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bartlett J.D., Kotake C., Fauth R., Easterbrooks M.A. Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: do maltreatment type, perpetrator, and substantiation status matter? Child Abuse Negl. 2017;63:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young-Wolff K.C., Alabaster A., McCaw B., et al. Adverse childhood experiences and mental and behavioral health conditions during pregnancy: the role of resilience. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2019;28(4):452–461. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LeMasters K., Bates L.M., Chung E.O., et al. Adverse childhood experiences and depression among women in rural Pakistan. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):400. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10409-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kristbergsdottir H., Valdimarsdottir H.B., Steingrimsdottir T., et al. The role of childhood adversity and prenatal mental health as psychosocial risk factors for adverse delivery and neonatal outcomes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2023;85:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2023.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahenge B., Stockl H., Mizinduko M., Mazalale J., Jahn A. Adverse childhood experiences and intimate partner violence during pregnancy and their association to postpartum depression. J Affect Disord. 2018;229:159–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rijlaarsdam J., Stevens G.W., Jansen P.W., et al. Maternal childhood maltreatment and offspring emotional and behavioral problems: maternal and paternal mechanisms of risk transmission. Child Maltreat. 2014;19(2):67–78. doi: 10.1177/1077559514527639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Su Y., D'Arcy C., Meng X. Intergenerational effect of maternal childhood maltreatment on next generation's vulnerability to psychopathology: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2022;23(1):152–162. doi: 10.1177/1524838020933870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doi S., Fujiwara T., Isumi A. Association between maternal adverse childhood experiences and mental health problems in offspring: an intergenerational study. Dev Psychopathol. 2021;33(3):1041–1058. doi: 10.1017/S0954579420000334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Plant D.T., Barker E.D., Waters C.S., Pawlby S., Pariante C.M. Intergenerational transmission of maltreatment and psychopathology: the role of antenatal depression. Psychol Med. 2013;43(3):519–528. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanetz-Gamliel K., Dollberg D.G. Links between mothers' ACEs, their psychopathology and parenting, and their children's behavior problems-A mediation model. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1064915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greene C.A., Haisley L., Wallace C., Ford J.D. Intergenerational effects of childhood maltreatment: a systematic review of the parenting practices of adult survivors of childhood abuse, neglect, and violence. Clin Psychol Rev. 2020;80 doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carpenter T., Grecian S.M., Reynolds R.M. Sex differences in early-life programming of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in humans suggest increased vulnerability in females: a systematic review. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2017;8(2):244–255. doi: 10.1017/S204017441600074X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deardorff J., Borgen N., Rauch S., Kogut K., Eskenazi B. Maternal adverse childhood experiences and young adult Latino children's mental health. Am J Prev Med. 2024;66(1):119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2023.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roberts A.L., Chen Y., Slopen N., et al. Maternal experience of abuse in childhood and depressive symptoms in adolescent and adult offspring: a 21-year longitudinal study. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(10):709–719. doi: 10.1002/da.22395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dalvie S., Maihofer A.X., Coleman J.R.I., et al. Genomic influences on self-reported childhood maltreatment. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):38. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-0706-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berzenski S.R., Yates T.M., Egeland B. In: Handbook of Child Maltreatment. Korbin J.E., Krugman R.D., editors. Springer Netherlands; Dordrecht: 2014. A multidimensional view of continuity in intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment; pp. 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Russotti J., Warmingham J.M., Handley E.D., Rogosch F.A., Cicchetti D. Child maltreatment: an intergenerational cascades model of risk processes potentiating child psychopathology. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;112 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conger R.D., Belsky J., Capaldi D.M. The intergenerational transmission of parenting: closing comments for the special section. Dev Psychol. 2009;45(5):1276–1283. doi: 10.1037/a0016911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Warrier V., Kwong A.S.F., Luo M., et al. Gene-environment correlations and causal effects of childhood maltreatment on physical and mental health: a genetically informed approach. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(5):373–386. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30569-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giunta H., Romanowicz M., Baker A., O'Toole-Martin P., Lynch B.A. Positive impact of education class for parents with adverse childhood experiences on child behavior. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2021;15(4):431–438. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2021.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Flanagan T., Alabaster A., McCaw B., et al. Feasibility and acceptability of screening for adverse childhood experiences in prenatal care. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2018;27(7):903–911. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2017.6649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Narayan A.J., Lieberman A.F., Masten A.S. Intergenerational transmission and prevention of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;85 doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.101997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nguyen M.W., Heberlein E., Covington-Kolb S., et al. Assessing adverse childhood experiences during pregnancy: evidence toward a best practice. AJP Rep. 2019;9(1):e54–e59. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1683407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baldwin J.R., Wang B., Karwatowska L., et al. Childhood maltreatment and mental health problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis of quasi-experimental studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180(2):117–126. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.20220174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O'Donnell S., Vanderloo S., McRae L., et al. Comparison of the estimated prevalence of mood and/or anxiety disorders in Canada between self-report and administrative data. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016;25(4):360–369. doi: 10.1017/S2045796015000463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Le Strat Y., Dubertret C. A single question to screen for major depression in the general population. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(7):831–834. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.