Summary

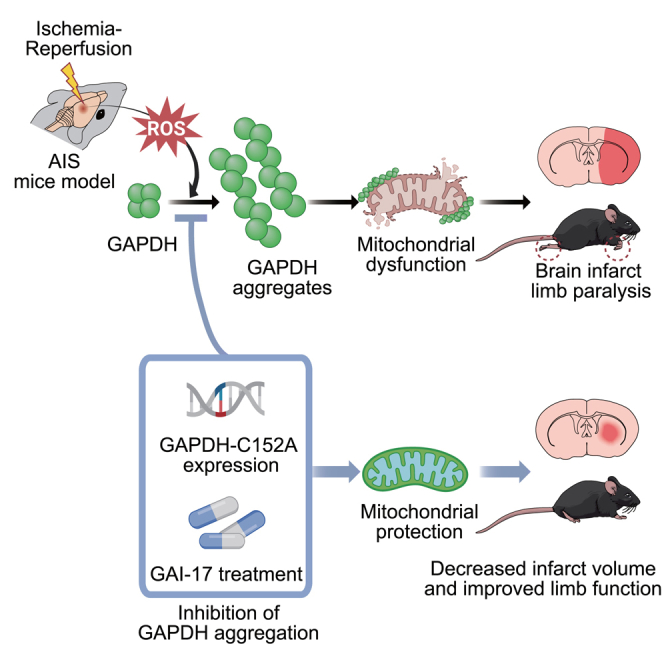

Neuronal death in acute ischemic stroke (AIS) is largely caused by the neurotoxic mechanism of oxidative/nitrosative stress, which is responsible for ischemia-reperfusion injury. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is a multifunctional protein that mediates cell death under oxidative/nitrosative stress. The active site of GAPDH, residue cysteine-152 (Cys-152), is oxidized and forms intermolecular disulfide bonds that induce GAPDH aggregation, which causes mitochondrial dysfunction and eventually leads to cell death. A GAPDH-C152A mutant dominant-negatively suppresses GAPDH aggregation. Herein, we report that neuron-specific expression of GAPDH-C152A in conditional transgenic mice decreased GAPDH aggregation and brain damage induced by ischemia-reperfusion injury in an AIS mouse model. Furthermore, GAPDH aggregation inhibitor peptide-17, developed by our peptide-screening-methods, ameliorated brain infarction and neurological deficits, even after 6 h of reperfusion. These findings suggest that inhibition of GAPDH aggregation may be a potential therapeutic target for AIS. Further efforts are warranted to translate these findings to treatment with AIS.

Subject areas: Genetics, Molecular biology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Neuron-specific expression of C152A-GAPDH decreased GAPDH aggregation in mice

-

•

Decreased GAPDH aggregation reduced brain damage induced by ischemia-reperfusion

-

•

A GAPDH aggregation inhibitor reduced infarct volume and neurological deficits

-

•

Inhibiting GAPDH aggregation may be a therapeutic target for acute ischemic stroke

Genetics; Molecular biology

Introduction

Stroke is the second leading cause of death, accounting for 11.6% of deaths worldwide.1 Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator is the only effective thrombolytic drug and is recognized as one of the most biologically effective treatments for acute ischemic stroke (AIS). However, its acceptability is limited.2 Other medications such as anticoagulants are merely symptomatic treatments and also have a short therapeutic time window (within 4.5 h for thrombolytic strategies and within 6 h for thrombectomy strategies after ischemic attacks).3,4 Therefore, a novel therapeutic approach, especially for potent neuroprotectants and stem cell therapies, is urgently needed to identify alternative strategies for treating AIS.5,6 Several lines of evidence suggest that, in addition to deprivation from oxygen and glucose due to the obstruction of blood flow, ischemia-reperfusion injury also plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of AIS.7,8,9,10 Robust oxidative/nitrosative stress occurs in the brain during ischemia-reperfusion, eventually leading to neuronal death.9 Accordingly, understanding the damage triggered by oxidative/nitrosative stress may shed light on the mechanisms underlying neurotoxic signaling pathways and help uncover potential therapies for AIS.

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is a glycolytic enzyme that is responsible for the sixth step of glycolysis. In addition to its metabolic function, it is now recognized as a multifunctional protein that exhibits various functions, such as DNA repair,11 tRNA export,12 transcription,13 membrane trafficking,14 heme metabolism,15,16 regulation of kinases,17,18 and apoptosis and necrosis.19,20,21,22 Two mechanisms have been proposed for GAPDH-mediated cell death: GAPDH nuclear translocation and GAPDH aggregation.20,21 Under oxidative/nitrosative stress, GAPDH binds to Siah and undergoes nuclear translocation.20 Nuclear GAPDH then induces p53-dependent transcription of apoptotic genes, resulting in apoptotic cell death.23,24 GAPDH also forms aggregates in response to oxidative/nitrosative stress via intermolecular disulfide bonds formed by the cysteine-152 residue (Cys-152) in the active site, followed by the formation of amyloid-like fibrils and cell death in vitro.25,26 GAPDH-overexpressing mice treated with methamphetamine, which causes robust oxidative/nitrosative stress in the brain, also display abundant GAPDH aggregates and neuronal cell death in vivo.26 Additionally, both oxidative/nitrosative stress-induced cell death and GAPDH aggregation are attenuated by a GAPDH mutant with a substitution of Cys-152 to alanine (GAPDH-C152A) in a dominant-negative manner in vitro.27 Furthermore, oxidative/nitrosative stress-induced GAPDH aggregation specifically induces mitochondrial dysfunction via opening of permeability transition pores, leading to necrotic cell death.28

In this context, it is thought that two distinct pathways of GAPDH-mediated cell death are involved in the brain damage and neurological deficits elicited by AIS. The difference between the pathways appears to be due to the degree of oxidative/nitrosative stress; GAPDH nuclear translocation is an initial event triggered by low to moderate oxidative/nitrosative stress-induced apoptotic cell death, whereas increasing stress promotes GAPDH aggregation, resulting in more severe (necrotic) cell death.26 Because a large amount of oxidative/nitrosative stress is generated during ischemia-reperfusion in AIS, GAPDH aggregation is suspected to be involved in stroke, especially considering the previous observation of GAPDH overexpression and accumulation under conditions of ischemia-reperfusion in a rat model of stroke.22,29 Thus, the contribution of GAPDH aggregation to AIS pathogenesis seems plausible.

Here, we investigated whether ischemia-reperfusion-induced GAPDH aggregation participates in the pathogenesis of AIS using conditional transgenic mice in which a dominant-negative GAPDH mutant decreases GAPDH aggregation in neurons. Our results demonstrated that GAPDH aggregation plays a critical role in ischemia-reperfusion-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequent neuronal cell death in AIS. Moreover, we developed a GAPDH aggregation inhibitor peptide and demonstrated its therapeutic potential. These results not only deepen our understanding of the mechanism of AIS pathology but also provide a potential therapy for AIS.

Results

GAPDH aggregation precedes the onset of infarction in a mouse model of AIS induced by MCAO

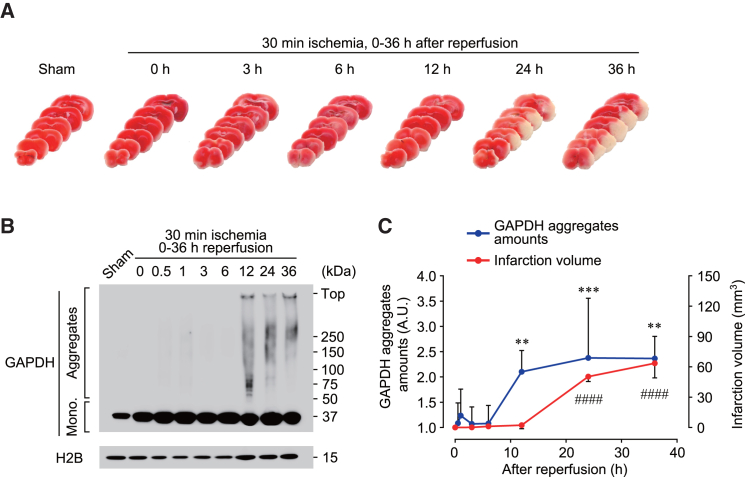

To examine the pathological role of GAPDH aggregation in AIS, we created a mouse model of AIS induced by transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). Mice were subjected to 30 min of ischemia and subsequent periods of reperfusion of various durations, and the brain infarct area in six coronal sections was measured (Figures 1A and 1C). Brain infarction was observed 24 h after reperfusion, and the infarct volume increased in a time-dependent manner (Figures 1A and 1C). GAPDH aggregation was evaluated by western blotting using an insoluble fraction from the striatum (ischemic core region) of mice that underwent MCAO, and GAPDH aggregates were detected 12 h after reperfusion (Figure 1B). Comparison of the infarct volume and the amount of GAPDH aggregates indicated that GAPDH aggregation preceded brain infarction after ischemia-reperfusion (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Development of brain infarction induced by MCAO is preceded by GAPDH aggregation

Mice were subjected to ischemia for 30 min followed by 0–36 h of reperfusion.

(A) Images of mouse coronal sections stained with TTC.

(B) Formation of GAPDH aggregates in the brain assessed by non-reduced western blotting.

(C) Quantification of the infarct volume (red line) and amount of GAPDH aggregates (blue line) in the indicated time. n = 3–8. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗∗p < 0.01 and ##p < 0.01, as determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s multiple range test.

Generation and characterization of neuron-specific GAPDH-C152A-overexpressing transgenic mice

We hypothesized that GAPDH aggregation plays a detrimental role in ischemia-reperfusion injury and that inhibiting GAPDH aggregation in transgenic mice resistant to GAPDH aggregation would prevent neuronal damage. Therefore, we generated a construct encoding human GAPDH-C152A, which decreases GAPDH aggregation in a dominant-negative manner, under the control of a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter containing a tetracycline response element (TRE).27,28 The inhibitory effect of human GAPDH-C152A on mouse GAPDH aggregation was confirmed in vitro (Figure S1A). Next, to assess the temporal and spatial regulation of GAPDH aggregation, we created transgenic mice carrying the inducible GAPDH-C152A construct, injected them with adeno-associated virus serotype 2 vector harboring tetracycline transactivator (tTA-AAV2), and then controlled the expression of GAPDH-C152A by doxycycline (Dox) treatment (Dox-off system, Figure S1B). In the absence of Dox, tTA bound to the TRE in the transgene, and transgenic mice expressed GAPDH-C152A under the control of the CMV promoter (Figure S1B, top); in contrast, in the presence of Dox, Dox-bound tTA could not bind to TRE, resulting in failure to express GAPDH-C152A (Figure S1B, bottom). The presence of the transgene encoding GAPDH-C152A was confirmed by genotyping PCR using primers specific for the indicated regions (Figure S1C). After tTA-AAV2 was injected at three sites in the striatum and cerebral cortex (Figure S1D, left), immunofluorescence staining revealed the expression of myc-tagged GAPDH-C152A in C152A-Tg mice only in the absence of Dox (Figure S1D, right). Furthermore, after co-immunostaining with specific antibodies against a neuronal marker (microtubule-associated protein 2; MAP2) and an astrocyte marker (glial fibrillary acidic protein; GFAP), myc signals were observed in MAP2-positive cells but not in GFAP-positive cells, indicating neuron-specific expression of GAPDH-C152A (Figure S1E). Importantly, GAPDH-C152A lacks glycolytic enzyme activity,26 which raises concerns regarding disruption of brain energy metabolism. Hence, we assessed whether GAPDH-C152A expression affected glycolytic enzyme activity in the mouse brain and found no significant difference in endogenous GAPDH activity regardless of the presence or absence of GAPDH-C152A (Figure S1F). Therefore, we successfully generated Dox-regulated conditional transgenic mice with neuronal GAPDH-C152A expression.

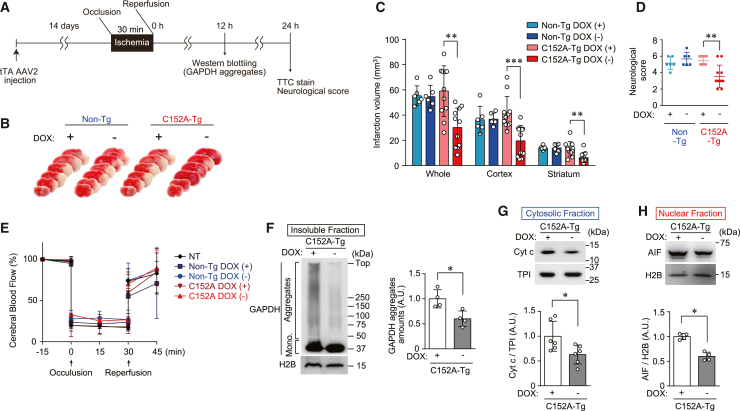

GAPDH-C152A expression mitigates ischemic brain damage by decreasing GAPDH aggregation

We next examined whether ischemia-reperfusion injury is mediated by GAPDH aggregation in non-Tg and C152A-Tg mice. Mice were injected with tTA-AAV2 and treated with either vehicle- or Dox-containing water for 14 days until they were subjected to MCAO. Both brain infarction and neural deficits were assessed 24 h after reperfusion, while GAPDH aggregate formation was evaluated 12 h after reperfusion (Figure 2A). The volume of the infarct area as determined by 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining was almost the same in all non-Tg mice, regardless of Dox treatment (Figure 2B) (infarction volume 55.4 ± 7.8 mm3 and 54.7 ± 9.0 mm3 in vehicle- and Dox-treated mice, respectively; Figure 2C). In contrast, C152A-Tg mice not treated with Dox had a significantly smaller infarct volume (30.2 ± 15.4 mm3) than those treated with Dox (59.1 ± 20.0 mm3, Figures 2B and 2C). Furthermore, the infarct area was significantly smaller in the cortex (known as the penumbra area) and striatum (known as the ischemic core, Figures 2B and 2C). Similarly, the neurological score, an index of unilateral paralysis, was significantly improved in C152A-Tg mice treated with Dox compared with those that were not treated with Dox (Figure 2D), indicating that GAPDH-C152A expression relieved the brain damage caused by ischemia-reperfusion. We then generated another strain of C152A-Tg mice (C152A-Tg strain 2) using the same strategy described previously to confirm these findings. The results showed that, similar to the C152A-Tg mice, C152A-Tg strain 2 mice exhibited smaller infarct areas and improved neurological scores compared with their non-Tg counterparts (Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Expression of C152A-GAPDH mitigates ischemic stroke damage by decreasing GAPDH aggregation and subsequent mitochondrial dysfunction

(A) Study design for the expression of C152A-GAPDH. Non-Tg or C152A-Tg mice were injected with tTA-AAV2, treated with the vehicle alone or Dox for 14 days, and then subjected to MCAO.

(B) Typical images of TTC-stained brain sections from non-Tg or C152A-Tg mice subjected to MCAO.

(C) Quantification of the infarct volume in the whole brain (left), cortex (middle), and striatum (right). n = 6–11.

Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗p < 0.01, relative to Dox (+), as determined by Student’s t test.

(D) Neurological scores at 24 h after reperfusion. n = 3–8. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, relative to Dox (+), as determined by the Mann-Whitney test.

(E) Change in the cerebral blood flow. Levels 15 min before occlusion per group are defined as 100%. n = 3–4, mean ± S.D.

(F) Formation of GAPDH aggregates, with graph showing the values calculated as the ratio of GAPDH aggregates to H2B.

(G) Cytosolic release of Cyt c, with graph showing the values calculated as the ratio of cytosolic Cyt c to TPI.

(H) Nuclear translocation of AIF with graph showing the values calculated as the ratio of nuclear-translocated AIF to nuclear H2B.

(F), (G), and (H) are assessed by western blotting in the striatum of C152A-Tg mice treated with the vehicle alone or Dox 12 h after ischemia-reperfusion as. These graphs showing the values calculated as the ratio of band intensities to each comparative band intensities with n = 4–6. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗p < 0.01, relative to Dox (+), as determined by Student’s t test.

To rule out the possibility that GAPDH-C152A expression resulted in phenotypic changes affecting AIS outcomes, several physiological parameters, namely mean blood pressure (MBP), heart rate (HR), blood gasses, pH, and rectal temperature (RT), were measured (Table S1). In addition, cerebral blood flow was monitored by Doppler flowmetry throughout the MCAO procedure, with no significant changes noted between the mice not injected with tTA-AAV2, non-Tg mice, and C152A-Tg mice, regardless of Dox treatment (Figure 2E). To determine the mechanism underlying the improvements in brain damage in C152A-Tg mice, we examined GAPDH aggregation. Western blotting of the insoluble fraction from the striatum showed a 60.2% reduction in GAPDH aggregates in Dox-untreated C152A-Tg mice compared with Dox-treated C152A-Tg mice (Figure 2F). Based on our previous study showing that GAPDH aggregates elicit mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequent cell death in vitro,28 we explored the possibility that mitochondrial dysfunction was caused by MCAO-induced GAPDH aggregation (Figures 2G and 2H). Mitochondrial dysfunction was assessed by the release of two cell death mediators from the mitochondria: cytochrome c (Cyt c), which enters the cytosol, and apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), which translocates into the nucleus. Cytosolic Cyt c and nuclear AIF levels were significantly decreased by 36.8% and 40.2%, respectively, in C152A-Tg mice that were not treated with Dox compared with those treated with Dox (Figures 2G and 2H). Taken together, these findings indicated that GAPDH-C152A expression decreased GAPDH aggregation, attenuated mitochondrial dysfunction, and mitigated brain damage induced by MCAO.

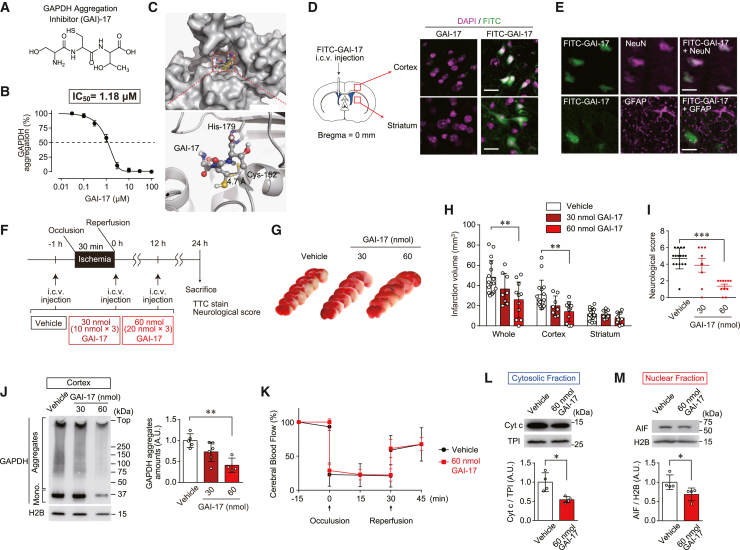

Pretreatment with GAPDH aggregation inhibitor-17 ameliorates brain damage and neurological deficits in a mouse model of MCAO

To further investigate whether pharmacological inhibition of GAPDH aggregation could prevent ischemic brain damage and be a therapeutic approach for AIS, we developed and optimized a GAPDH aggregation inhibitor (GAI). We previously reported that a decapeptide (GAI-1) that is largely complementary to a fragment of GAPDH containing the active site Cys-152 inhibits GAPDH aggregation30 but has a low potency that appears to be insufficient for its application in vivo. Thus, a series of peptides with various numbers and/or types of amino acids was designed and evaluated regarding their ability to inhibit GAPDH aggregation and affect cell viability and GAPDH enzymatic activity in vitro (Table 1). Among them, the serine-cysteine-threonine tripeptide GAI-17 showed the most potent inhibitory activity (97.2% at 50 μM) against GAPDH aggregation without any adverse effects such as loss of cell viability and disturbance of GAPDH enzymatic activity (Table 1). The chemical structure of GAI-17 is shown in Figure 3A. The inhibitory potency of GAI-17 against GAPDH aggregation was measured. GAI-17 displayed potent inhibitory activity in a concentration-dependent manner (IC50 = 1.18 μM, Figure 3B). A docking model of GAI-17 on the surface of GAPDH was constructed using AutoDock Vina to elucidate the inhibitory mechanism of GAI-17 (Figure 3C). The model suggested that GAI-17 could fit into a pocket near the Cys-152 residue of GAPDH, a critical residue that mediates GAPDH aggregation by forming intermolecular disulfide bonds.21,26 To evaluate GAI-17 distribution in the brain, mice were intracerebroventricularly (i.c.v.) injected with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated GAI-17 (Figure 3D, left). Green fluorescent signals were observed intracellularly in both the cortex and striatum of mice injected with FITC-conjugated GAI-17 but not in mice injected with GAI-17 without FITC (Figure 3D, right). To further identify the types of cells into which GAI-17 was incorporated, immunohistochemical staining in the cortex was performed for either neuron-specific nuclear protein (NeuN) or GFAP as specific markers for neurons or astrocytes, respectively. Interestingly, the results clearly showed that the fluorescent signals of FITC-conjugated GAI-17 were observed in neurons but not in astrocytes (Figure 3E). Together, these results indicate that GAI-17 was specifically incorporated into neurons following i.c.v. injection.

Table 1.

Screening of GAIs

| GAI | Sequence | Potency |

Cytotoxicity |

Side effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggregation inhibitory activity (%) | Cell viability (%) | Effect on GAPDH activity (%) | ||

| 1 | SNASCTTNAL | 53.1 2.87 | 100 2.43 | 104 2.73 |

| 2 | SLKIISNASCTTNALAPLAK | 70.8 1.89 | 16.2 2.91∗,∗∗ | |

| 3 | SVKIISNASCTTNALAPLAK | 80.1 2.78 | 2.60 0.22∗,∗∗ | |

| 4 | SLKIISNASCTTNALAPVAK | 72.0 2.11 | 9.06 2.73∗,∗∗ | |

| 5 | SNASCTTNAL | |||

| 6 | SNASCTTNSL | 25.0 2.87 | 100 3.52 | 94.5 9.77 |

| 7 | SNASATTNCL | |||

| 8 | SNASCTTNDL | 58.7 2.55 | 102 3.68 | 99.5 2.68 |

| 9 | SNASCTTNFL | 22.8 2.44 | 101 3.18 | 104 1.60 |

| 10 | SNASCTTNGL | 56.4 2.77 | 102 1.28 | 97.0 3.32 |

| 11 | SCTTNAL | 48.3 1.06 | 101 3.28 | 106 3.32 |

| 12 | SNASCTT | 46.2 2.91 | 100 3.01 | 98.8 5.01 |

| 13 | SCTT | 89.6 2.79 | 101 3.05 | 97.6 6.14 |

| 14 | NASC | 74.9 3.00 | 101 1.44 | 96.5 6.15 |

| 15 | ASCT | 72.2 2.49 | 102 1.12 | 98.0 4.49 |

| 16 | CTTN | 70.8 2.10 | 101 1.24 | 96.1 10.6 |

| 17 | SCT | 97.2 1.88 | 101 2.95 | 100 1.19 |

| 18 | ASC | 80.3 2.18 | 102 2.95 | 109 4.57 |

| 19 | CTT | 89.7 2.56 | 101 2.15 | 108 4.80 |

| 20 | ACT | 83.4 1.84 | 102 1.85 | 103 9.17 |

| 21 | SCA | 86.5 2.56 | 101 0.90 | 93.6 8.71 |

| GSH | ECG | 43.3 2.55 | 101 3.17 | 98.5 3.60 |

Twenty peptides (GAI-2–21) based on the amino acid sequence of GAI-1 were synthesized and evaluated with GAPDH aggregation inhibitory effect (potency), the effect on cell viability (cytotoxicity), and GAPDH activity (side effect). n = 4, mean ± S.D. ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗p < 0.01, relative to the treatment with vehicle, as determined by Student’s t test. Endogenous cysteine-containing tripeptide glutathione (GSH) was examined (bottom row), as compared with GAI-17. () means “not determined.”

Figure 3.

GAI-17 is effective against ischemic brain injury

(A) Chemical structure of GAI-17.

(B) Inhibitory effect of GAI-17 in vitro and the calculated IC50 value.

(C) Structural model of GAI-17 and the GAPDH complex obtained by AutoDock Vina. GAPDH is represented as a cartoon drawing and surface model (gray). The Cys-152 and His-179 of GAPDH and GAI-17 are shown as sticks.

(D) Injection site of FITC-GAI-17 (left) and fluorescent images of FITC and DAPI staining (right). Brain sections from the cortex of mice i.c.v. treated with either GAI-17 or FITC-labeled GAI-17 (green) stained with DAPI (nuclear marker, magenta). Scale bar, 40 μm.

(E) Immunohistochemical images for NeuN, GFAP, and FITC-labeled GAI-17. Brain sections from the cortex of mice i.c.v. treated with FITC-labeled GAI-17 stained immunohistochemically for either NeuN (neuron marker, magenta) or GFAP (astrocyte marker, magenta). Scale bar, 20 μm.

(F) Study design for i.c.v. injection (pre-treatment) with the vehicle or GAI-17 (30 or 60 nmol) at three time points (1 h prior to reperfusion, immediately after reperfusion, and 12 h after reperfusion).

(G) Typical images of TTC-stained brain sections from mice subjected to MCAO and pre-treated with GAI-17.

(H) Quantification of the infarct volume in the whole brain (left), cortex (middle), and striatum (right). n = 8–16. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗p < 0.01, as determined by Dunnett’s test.

(I) Neurological scores at 24 h after reperfusion. n = 8–16. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗∗p < 0.01, as determined by the Mann–Whitney test.

(J) Formation of GAPDH aggregates, with graph showing the values calculated as the ratio of GAPDH aggregates to H2B.

(K) Change in the cerebral blood flow. Levels 15 min before occlusion per group are defined as 100%. n = 4, mean ± S.D.

(L) Cytosolic release of Cyt c, with graph showing the values calculated as the ratio of cytosolic Cyt c to TPI.

(M) Nuclear translocation of AIF with graph showing the values calculated as the ratio of nuclear-translocated AIF to nuclear H2B.

(J), (L) and (M) are assessed by western blotting in the cortex of mice treated with the vehicle or GAI-17 (30 and 60 nmol in J, 60 nmol in L and M) 12 h after ischemia-reperfusion as assessed by western blotting, with (J), (L), and (M) graph showing the values calculated as the ratio of band intensities to each comparative band intensities. n = 4–6. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗p < 0.01, relative to treatment with the vehicle, as determined by Student’s t test.

To assess the therapeutic effect of GAI-17 in the MCAO model, mice were treated with 10 or 20 nmol GAI-17 three times (totaling 30 or 60 nmol/mouse, respectively): 1 h before, immediately after, and 12 h after reperfusion (Figure 3F). In the vehicle treatment group, MCAO induced extensive injury in both the cortex and striatum, resulting in infarct volumes of 30.8 ± 14.4 mm3 and 11.7 ± 5.5 mm3, respectively (Figures 3G and 3H). However, pretreatment with GAI-17 reduced the infarct volumes in a dose-dependent manner. In the high-dose-treated group (60 nmol GAI-17), the infarct volume was significantly decreased by 14.1 ± 9.8 mm3 in the cortex but was not reduced in the striatum (7.9 ± 5.4 mm3, Figures 3G and 3H). In addition, the neurological score was significantly improved by treatment with 60 nmol of GAI-17 (Figure 3I). We next examined the levels of GAPDH aggregation in the cortex to determine whether these improvements in MCAO-induced neurological dysfunction induced by GAI-17 depended on its GAI activity. Treatment with GAI-17 dose-dependently inhibited the levels of GAPDH aggregation in the cortex (Figure 3J) but not in the striatum (Figure S3), which is consistent with the findings regarding both the infarct volume and neurological score. After treatment with 60 nmol GAI-17, there were no changes in physiological parameters, namely MBP, HR, blood PaO2, PaCO2, pH, RT, (Table S2) and cerebral blood flow (Figure 2K), during ischemia-reperfusion. Finally, we investigated the effects of GAI-17 on mitochondrial dysfunction, as determined by cytosolic Cyt c and nuclear AIF levels. The cytosolic Cyt c and nuclear AIF levels were significantly decreased by 54.3% and 68.5%, respectively, in mice treated with 60 nmol GAI-17 compared with those treated with the vehicle (Figures 3L and 3M). These results indicate that pretreatment with GAI-17 ameliorated brain damage and neurological deficits by improving mitochondrial dysfunction in a mouse model of AIS.

Post-treatment with GAI-17 alleviates brain infarction and neurological deficits in a mouse model of AIS

To determine the therapeutic time window for GAI-17, we examined the effects of post-treatment with GAI-17 in a mouse model of AIS. Mice were treated with vehicle (vehicle group) or GAI-17 3 h after reperfusion (post-3-h group), 6 h after reperfusion (post-6-h group), or 9 h after reperfusion (post-9-h group) and were then treated again 12 h after reperfusion (Figure 4A). The infarct volume was significantly decreased to 27.7 ± 26.0 mm3 and 27.8 ± 18.1 mm3 in the post-3-h and post-6-h groups, respectively, compared with the vehicle group (54.8 ± 26.5 mm3, Figures 4B and 4C); furthermore, the reductions were observed in the cortex but not in the striatum (Figures 4B and 4C). In addition, the neurological deficits were substantially recovered by 3 and 6 h after treatment with GAI-17 (Figure 4D); however, treatment at 9 h after reperfusion did not result in any protective effect (Figure 4D). These results demonstrate that treatment with GAI-17 improved the brain damage induced by ischemia-reperfusion, even at 6 h after reperfusion.

Figure 4.

Post-treatment with GAI-17 ameliorates brain damage and neurological deficits in a mouse model of AIS elicited by MCAO

(A) Study design for GAI-17 intracerebroventricular injection of the vehicle or GAI-17 (60 nmol) at two time points (3 and 12 h after reperfusion, 6 and 12 h after reperfusion, or 9 and 12 h after reperfusion).

(B) Typical images of TTC-stained brain sections from mice subjected to MCAO and post-treatment with GAI-17.

(C) Quantification of the infarct volume in the whole brain (left), cortex (middle), and striatum (right). n = 8–13. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, as determined by Dunnett’s test.

(D) Neurological scores assessed at 24 h after reperfusion. n = 8–13. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗∗p < 0.01, as determined by the Mann-Whitney test.

Discussion

The present study first demonstrated that GAPDH aggregates were observed earlier than the onset of brain infarction after ischemia-reperfusion in a mouse model of AIS elicited by MCAO (Figure 1). Oxidative/nitrosative stress is known to be strongly induced by ischemia-reperfusion in the MCAO brain,22,31 which may oxidize GAPDH and form GAPDH aggregates. Thus, GAPDH aggregation is likely a causal mechanism for neuronal death in AIS. We found that decreasing GAPDH aggregation by expressing GAPDH-C152A in C152A-Tg mice mitigated mitochondrial dysfunction and improved both brain damage and neurological deficits (Figure 2), indicating that inhibition of GAPDH aggregation may be neuroprotective in AIS. As we reported previously, GAPDH-C152A appears to prevent GAPDH aggregation by forming enzymatically active heterotetramers with wild-type GAPDH that are not prone to forming amyloid-like fibrils.27 Furthermore, we identified GAI-17 using our peptide-screening method (Table 1 and Figure 3A) and demonstrated its therapeutic efficacy in a mouse model of AIS (Figures 3 and 4). These genetic and pharmacological approaches revealed the significance of GAPDH aggregation in AIS pathogenesis.

GAPDH-C152A expression does not seem to interfere with GAPDH nuclear translocation. The active site Cys-152 is essential not only for GAPDH aggregation, but also for the nuclear translocation of GAPDH.20,25 Accordingly, we evaluated whether GAPDH-C152A expression affected GAPDH nuclear translocation in C152A-Tg mice subjected to MCAO (Figure S4). Western blotting of the nuclear fraction of the striatum showed no difference in the amount of nuclear GAPDH between Dox-treated and untreated C152A-Tg mice (Figure S4A). Moreover, we used deprenyl, an inhibitor of GAPDH nuclear translocation,32 to examine whether nuclear translocation of GAPDH participated in the development of brain infarction caused by MCAO. Treatment with deprenyl had no significant effect (Figure S4B), indicating less involvement of GAPDH nuclear translocation in the pathogenesis, at least in part, in the AIS model. Taken together, these findings suggest that GAPDH-C152A expression specifically decreased GAPDH aggregation, which exerted beneficial effects in the AIS model.

Experiments with C152A-Tg mice may help elucidate the pathophysiological role of GAPDH aggregation in vivo. Dox-regulated conditional C152A-Tg mice were generated that expressed GAPDH-C152A specifically in neurons (Figure S1E). It has been reported that AAV2 efficiently delivers exogenous genes to neurons22,33,34; therefore, this property of AAV2 appears to be the reason for neuronal specificity in C152A-Tg mice. Importantly, to retain its glycolytic activity, GAPDH must form a homotetramer.35 Considering that our previous study showed that GAPDH-C152A interacts with endogenous GAPDH to form a heterotetramer,27 it is possible that exogenous GAPDH-C152A expression inhibits endogenous GAPDH enzymatic activity in C152A-Tg mice. Thus, we measured GAPDH enzyme activity in the brains of Tg mice expressing GAPDH-C152A and found no significant differences between groups (Figure S1F). Furthermore, no other physiological parameters differed significantly between non-Tg and C152A-Tg mice (Figure 2E; Table S1). Therefore, given that there is currently a lack of approaches to specifically inhibit GAPDH aggregation, C152A-Tg mice might be useful for investigating the pathophysiological significance of GAPDH aggregation in ischemia-reperfusion–induced disorders, such as AIS.

GAI-17 suppressed GAPDH aggregation without inhibiting its glycolytic activity and without affecting cell viability (Table 1). We designed GAIs based on the concept that interaction with the active cysteine site (Cys-152), a critical residue for GAPDH aggregation, could interfere with intermolecular disulfide bond formation among GAPDH molecules and their subsequent aggregation. Although Cys-152 is also essential for GAPDH enzyme activity,26 GAI-17 did not affect GAPDH enzyme activity (Table 1). To investigate the residues of GAPDH involved in binding to GAI-17, we performed a docking simulation of GAPDH and GAI-17 using AutoDock Vina software.36,37 The in silico analysis demonstrated that GAI-17 bound near Cys-152 in GAPDH (Figure 3C). The intermolecular interactions in the structural model were analyzed using the LigPlot+ program38 (Figure S5). Eight residues, including Cys-152 in GAPDH, were involved in hydrophobic interactions with GAI-17. Moreover, Thr-211 and Arg-234 in GAPDH formed hydrogen bonds with GAI-17. However, the calculated distance between the β-carbon of cysteine in GAI-17 and that of Cys-152 in GAPDH was 4.7 Å (Figure 3C), which is not close enough to form a disulfide bond.39 Furthermore, the formation of a hydrogen bond between Cys-152 and His-179, which leads to de-protonation of Cys-152 and is responsible for the production of thiohemiacetal tetrahedral intermediate from gleceraldehyde-3-phosphate in the glycolytic reaction,40 is not likely to be interfered with by GAI-17 binding (Figure 3C). These observations suggest that reversible binding and suitable configuration of GAI-17 near Cys-152 in GAPDH makes it possible to achieve both inhibition of GAPDH aggregation and retention of enzyme activity. This phenomenon requires further investigation via structural analysis using X-ray crystallography.

The experiment using FITC-labeled GAI-17 showed that i.c.v.-injected GAI-17 strictly localized to neurons (Figures 3D and 3E) but was nearly absent from astrocytes. This characteristic is thought to be beneficial in elucidating GAPDH aggregation-related neuronal disorders. Although the precise mechanisms responsible for this property are yet to be determined, it might be due to the participation of peptide transporters. The proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter PEPT2 is a well-known intestinal and renal peptide carrier. In addition to these classical roles, PEPT2 has been detected in the cerebral cortex, olfactory bulb, basal ganglia, cerebellum, and hindbrain sections of the adult rat brain by immunoblot analysis, with the strongest signals in the cerebral cortex.41 Interestingly, double-labeling experiments have also revealed that PEPT2 immunoreactivity in the brain colocalizes with NeuN, a neuronal marker, but not with GFAP, an astrocyte marker.41 Taking these findings into account, it is possible that the neuronal specificity and therapeutic efficacy in the cerebral cortex of GAI-17 in the present study may have been mediated by PEPT2. However, further studies are required to elucidate the mechanisms underlying GAI-17 incorporation.

The present study demonstrated that i.c.v. pretreatment with GAI-17 before ischemia attenuated brain infarction and neurological failure in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 3G–3I), concomitant with a reduction in cortical GAPDH aggregation (Figure 3J). However, GAI-17 pretreatment did not appear to reduce GAPDH aggregation in the striatum (Figure S3). This is not surprising, given that the striatum represents the ischemic core of MCAO-induced injury, and no drugs or treatments that reduce this damage have been reported to date. Notably, post-treatment with GAI-17 also decreased brain damage, even after 6 h of reperfusion (Figures 4B–4D). Although GAI-17 had no therapeutic effect when administered 9 h after reperfusion, its therapeutic time window appears to be longer than that of t-PA42,43,44 and other neuroprotectants.45,46 Recently, it was reported that a Tat-cold-inducible RNA binding protein (CIRP) peptide is capable of perturbing myeloid differentiation protein 2 (MD-2) in cortical neurons, functions as a neuroprotectant via a TLR4-independent, Sam68-related cascade, and exerts a strong neuroprotective effect in a mouse model of AIS, even after 6 h of reperfusion.47 However, the effects are no longer seen when Tat-CIRP is administered 9 h after reperfusion.47 These results are almost equivalent to the results obtained from the present study in terms of therapeutic time windows (Figure 4). Similar to the treatment of MD-2 signaling disturbance by Tat-CIRP, the wide therapeutic time window determined by our experiments has the potential to inhibit GAPDH aggregation and be developed into a novel AIS therapy, especially with the increasing clinical use of thrombolytic or mechanical reperfusion therapies in patients with AIS. However, there are still unresolved issues regarding the application of GAI-17 and of Tat-CIPR. For AIS treatment, it is desirable to administer drugs via bolus injection and subsequent infusion. However, GAI-17 is predicted to be unstable in mouse blood serum because of endopeptidase cleavage upon peripheral injection. To eliminate this problem, there is a need to develop a peptide-mimicking small molecule that inhibits GAPDH aggregation based on the chemical structure of GAI-17. We have synthesized a small organic compound mimicking GAI-17 (WO2016199796A1) that results in robust reductions in both brain damage and neurological deficits via systemic administration in a mouse model of AIS elicited by MCAO (these details are tentatively under preparation for another report). Another GAI called RX624 (hydrocortisone-21-hemisuccinate) has neuroprotective effects in the context of both oxidative/nitrosative stress-induced neuronal death and traumatic brain injury in a rodent model.48,49,50,51 RX624 binds to the pocket near Cys-152 in the active site of GAPDH and exhibits potent GAPDH aggregation inhibitory activity without inhibiting GAPDH enzyme activity, similar to the effects of GAI-17.52 However, given its hydrocortisone-derived chemical structure, it is possible that RX624 exerts its therapeutic effects not through its GAPDH aggregation inhibitory activity but via off-target effects (e.g., anti-inflammatory activity). Further research and development of various types of GAIs might lead to a new therapeutic strategy for AIS by inhibiting GAPDH aggregation. Future studies should investigate the longer-term effects of GAIs on GAPDH aggregation in the striatum, as well as other brain regions, and on neurological function in the chronic phase of stroke.

In contrast to GAPDH-C152A expression in the MCAO-treated brain, GAI-17 treatment at 60 nmol reduced not only insoluble GAPDH aggregate formation but also the quantity of insoluble GAPDH monomers (Figures 2F and 3J). Specifically, GAPDH-C152A expression in neurons decreased insoluble GAPDH aggregate formation (the high molecular smear blots) but did not affect the contents of insoluble GAPDH monomer (Figure 2F), whereas GAI-17 reduced both insoluble GAPDH forms in the AIS model (Figure 3J). Although insoluble GAPDH monomers are known to be present even in unstimulated neurons,26,27,28,53 the mechanisms driving their insolubilization and pathophysiological roles remain entirely unknown. It has been reported that structural change of monomers of polyglutamine protein induced neurotoxicity, suggesting that the toxic conformational changes in the monomer are possibly responsible for neurodegeneration.54 In this regard, our comparative analysis of genetic and pharmacological interventions in the current study may facilitate future investigations into the unresolved issue of insoluble GAPDH monomer function.

In summary, we demonstrated that both expression of the dominant-negative molecule GAPDH-C152A and administration of GAI-17 decreased brain infarction/neurological deficits via improvement of mitochondrial dysfunction by interfering with GAPDH aggregation, thereby leading to robust neuroprotection in a mouse model of AIS. Our study suggests that a GAI such as GAI-17 shows promise as a neuroprotectant against AIS without affecting physiological function. These results warrant further studies on the translation of GAIs for the treatment of AIS in humans.

Limitations of the study

This study had some limitations. First, we only studied the neuroprotective effects of GAI-17 using a transient MCAO model in mice; however, this model is only representative of a small proportion of patients with AIS.47 Hence, it remains unclear whether the administration of GAIs would improve brain damage/neurological deficits in the absence of reperfusion. Further studies investigating the neuroprotective effects of GAIs (such as GAI-17 or RX624) in a permanent MCAO model are needed. Second, we only examined the effects of GAI-17 in the acute phase of the MCAO model (up to 48 h). Further studies are warranted to elucidate whether the neuroprotective effects of GAIs like GAI-17 are maintained in the subacute (approximately 7 days) and chronic (approximately 30 days) phases of ischemic stroke. Third, the present study could not comprehensively investigate the off-target effects of GAI-17, which should be addressed because of the therapeutic applications of GAIs such as GAI-17 in patients with AIS. The present study showed that GAPDH-C152A expression and GAI-17 treatment did not affect the levels of pyruvate, an index of physiological metabolic turnover, in the brain (data not shown); therefore, it does not appear to exert neuroprotective effects via anti-inflammatory activity, as is the concern with outcomes achieved using RX624. The present study seemed to show no sex differences in either the effects of GAI-17 or the expression of GAPDH-C152A in a mouse model of AIS, although females were less susceptible to brain damage than males (see Mendeley Data in key resources table), consistent with previous reports.55,56

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Hidemitsu Nakajima (h_nakajima@omu.ac.jp or hnakajima@vet.osakafu-u.ac.jp).

Materials availability

No new reagents were generated as part of this study.

Data and code availability

-

•

All raw data, including uncropped images of the western blots and agarose gels (Data S1), are publicly accessible through Mendeley Data (see DOI listed in the key resources table). Microscopy data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report unique code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Andreas Pluckthum and Dr. Peter Lindner (Zurich University) for providing the gap (−) Escherichia coli strain W3CG and Syusaku Higashida, Akinori Kita, and Mitsuki Nagayama (Osaka Prefecture University) for excellent assistance with some of the in vitro and in vivo experiments. Finally, we thank Dr. Kelly Zammit, BVSc, and Dr. Emily Crow, PhD, from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for providing writing support for this manuscript. This work was supported by MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI in a Grant-in-Aid to H.N. (JP25450428, JP19580346, and JP16H05029) and T.H. (JP23K24205 and JP25K02547), a Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research to H.N. (Exploratory; JP17K19330) and to H.T. (Exploratory; JP23K18163), and the Collaborative Research Program of Institute for Protein Research, the University of Osaka, to T.H. (ICR-24-03), and by AMED to H.N. (grant number JP23ym0126815) and T.H. (grant numbers JP21wm0425010 and JP21gm1510006).

Author contributions

M.I., T.K., and A.K. contributed equally to this work. H.N., M.I., T.K., T.I., and T.H. designed the study. T.K. contributed to the generation of conditional transgenic mice expressing C152A-GAPDH without Dox. T.K. and T.H. contributed to the preparation of AAV2 particles harboring the tTA gene. A.K. performed the MCAO surgery in mice. M.I. conducted the neurological tests and measured the infarct volumes. T.K. prepared the GAI-17 and vehicle solutions for treatments, and M.I. separately performed the i.c.v. injections of the vehicle or GAI-17 to ensure that the researchers were blinded to the drug treatments. T.K., M.I., A.K., and H.N. performed the peptide-screening assay and other biochemical/immunohistochemical studies. M.N. and T.I. performed the molecular docking simulation study. N.H., R.Y., and H.N. contributed to the revised manuscript. M.I. performed the statistical analysis and summarized all raw data. H.N. wrote the manuscript. H.N. and T.H. contributed to the funding acquisition. M.I., A.K., and H.N. contribute major revisions in accordance with submitting policies of iScience. H.N. supervised and coordinated the research. All authors have given their final approval of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit anti-AIF polyclonal antibody | R&D Systems | Cat# AF1457, RRID: AB_2224516 |

| Mouse anti-cytochrome-c monoclonal antibody | BD Biosciences | Cat# 556432, RRID: AB_396416 |

| Mouse anti-GAPDH monoclonal antibody (clone 6C5) | Millipore | Cat# MAB374 RRID: AB_2107445 |

| Rabbit anti-GAPDH polyclonal antibody | Yamaji et al. 2003, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016748890200397X?via%3Dihub | N/A |

| Mouse anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) monoclonal antibody (Clone 6F2) | Agilent Technologies (DAKO) | Cat# M0761 RRID: AB_2109952 |

| Rabbit anti-H2B polyclonal antibody | Sigma-Aldrich (Upstate) | Cat# SAB4503276 RRID: AB_10747200 |

| Rabbit anti-MAP2 rabbit polyclonal antibody | Millipore | Cat# AB5622 RRID: AB_91939 |

| Rabbit anti-myc polyclonal antibody (A-14) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-789 RRID: AB_631274 |

| Rabbit anti-myc monoclonal antibody (Clone 9E10) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-40 RRID: AB_627268 |

| Mouse anti-NeuN monoclonal antibody (Clone A60) | Millipore | Cat# MAB377 RRID: AB_2298772 |

| Rabbit anti-TPI polyclonal antibody | Yamaji et al. 2003, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016748890200397X?via%3Dihub | N/A |

| Mouse anti-CIV (OxPhos Complex IV) monoclonal antibody (Clone 1D6E1A8) | Invitrogen | Cat# 459600 N/A |

| Secondary (western blotting): goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L), HRP-conjugated | BIO-RAD | Cat #172-1011 RRID: AB_11125936 |

| Secondary (western blotting): goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L), HRP-conjugated | BIO-RAD | Cat #172-1019 RRID: AB_11125143 |

| Secondary (immunohistochemistry): donkey anti-mouse IgG, Alexa-Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Invitrogen) | Cat # A32723 RRID: AB_2633275 |

| Secondary (immunohistochemistry): donkey anti-mouse IgG, Alexa-Fluor 568 | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Invitrogen) | Cat# A10037 RRID: AB_11180865 |

| Secondary (immunohistochemistry): donkey anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa-Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Invitrogen) | Cat# A32790 RRID: AB_2762833 |

| Secondary (immunohistochemistry): donkey anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa-Fluor 568 | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Invitrogen) | Cat# A10042 RRID: AB_2534017 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| W3CG (K5 strain) | Ganter et al. 1990, https://doi.org/10.1021/bi00492a013 | N/A |

| pTRE2 | Clontech (TAKARA) | https://www.addgene.org/vector-database/4412/ Cat#6241-1 |

| pTRE2-GAPDH-C152A | Present study | N/A |

| pAAV-FtTA | Hikida et al. 2010, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.011 | N/A |

| pAAV-MCS | Agilent Technologies | Cat #240071 |

| pAAV-RS | Agilent Technologies | Cat #240071 |

| pHelper | Agilent Technologies | Cat #240071 |

| tTA-AAV2 | Hikida et al. 2010, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.011 | N/A |

| pBAD-HisA | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Invitrogen) | Cat # V430-01 |

| pBAD-HisA-human GAPDH | Nakajima et al. 2009, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.027698 | N/A |

| pBAD-HisA-mouse GAPDH | Nakajima et al. 2015, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.635607 | N/A |

| pBAD-HisA-human C152A-GAPDH | Nakajima et al. 2009, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.027698 | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Doxycycline (Dox) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # D3447 |

| 2,3,5-Triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # T8877 |

| 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) | DOJINDO | Cat # D523 |

| Protease inhibitor cocktail | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Roche) | Cat # 11836145001 |

| Blocking One | Nakalai Tesque | Cat # 03953-95 |

| Isoflurane | DS Pharm | Cat # 59272 |

| Paraformaldehyde | MERK-Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # 158127 |

| NOR3 | DOJINDO | Cat # N390 |

| Fluorescence Mounting Medium | Agilent Technologies (Dako) | Cat # S3023 |

| Deprenyl | Fujimoto Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse (M. musculus), C57BL/6J | Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 000664 RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664 |

| C57BL/6J C152A-Tg mice | Present study | N/A |

| C57BL/6J C152A-Tg strain 2 mice | Present study | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| C152A (mutagenesis) sense 5′-ATCAGCAATGCCTCCGCCACCACCAAC-3′ | Present study | N/A |

| C152A (mutagenesis) antisense 5′-GTTGGTGGTGGCGGAGGCATTGCTGAT-3′ | Present study | N/A |

| pBAD-HisA sequencing primer (forward) 5′- ATGCCATAGCATTTTTATCC -3′ |

Thermo Fisher Scientific (Invitrogen) | Cat #V430-01 |

| pBAD-HisA sequencing primer (reverse) 5′- GATTTAATCTGTATCAGG -3′ |

Thermo Fisher Scientific (Invitrogen) | Cat #V430-01 |

| pTRE2 sequencing primer (forward) 5′-GACCTCCATAGAAGACACCG-3′ |

Clontech (TAKARA) | Cat# 6241-1 |

| pTRE2 sequencing primer (reverse) 5′-TACAAGGGACATCTTCCCATTC-3′ |

Clontech (TAKARA) | Cat# 6241-1 |

| Primer-A forward (genotyping) 5′-GGTACCCGGGTCGAGGTAGGCGTGT-3′ |

Present study | N/A |

| Primer-A reverse (genotyping) 5′-GAATTCGGGGCCGCGGAGGCT-3′ |

Present study | N/A |

| Primer-B forward (genotyping) 5′-CCGTCAGATCGCCTGGAGACGCCAT-3′ |

Present study | N/A |

| Primer-B reverse (genotyping) 5′-TGGTGACCAGGCGCCCAATACGACC-3′ |

Present study | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pTRE2-C152A-GAPDH-myc | Present study | N/A |

| Cells | ||

| PC12 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1721 RRID:CVCL_0481 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Mendeley data | Present study | https://doi.org/10.17632/r63n4pk94p.3 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Agilent (Stratagene) | Cat # 200518 |

| QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit | Qiagen | Cat # 28706 |

| Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Invitrogen) | Cat # 11668019 |

| VIRA TRAP AAV Purification Kit | Omega Bio-Tek | Cat #V1169-00 |

| AAV2 Titration ELISA Kit | Progen | Cat # PRATV |

| Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kits | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Pierce) | Cat # 23225 |

| Pierce™ ECL Plus Western Blotting Substrate | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Pierce) | Cat # 32132 |

| CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay | Promega | Cat #G7573 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| AutoDock Vina | The Scripps Research Institute |

https://vina.scripps.edu RRID:SCR_011958 |

| Ligplot+ | European Bioinformatics Institute | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/software/LigPlus/RRID:SCR_018249 |

| Pymol 3.0 | Schrödinger |

https://pymol.org RRID:SCR_000305 |

| GraphPad Prism 10.2.2 | GraphPad Software | RRID:SCR_002798 |

| BioRender (Preparation of Graphical Abstract) | © 2024 BioRender. | https://www.biorender.com/RRID: SCR_018361 |

| ImageJ 1.51j8 (western blotting, TTC) | Wayne Rasband, NIH |

http://imagej.nih.gocij RRID:SCR_003070 |

| SoftMax® Pro software | Molecular Devices Japan |

https://www.moleculardevices.com/products/microplate-readers/acquisition-and-analysis-software/softmax-pro-software RRID:SCR_014240 |

| EZ-C1 Free viewer Gold Version 3.90 (immunohistochemistry) | Nikon | RRID:SCR_014277 |

| Multigauge (western blotting) | FUJI-FILM | RRID:SCR_014299 |

| Other | ||

| GAI-1 | Itakura et al.53, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.09.150. | N/A |

| GAI-2 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-3 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-4 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-5 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-6 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-7 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-8 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-9 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-10 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-11 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-12 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-13 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-14 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-15 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-16 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-17 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-18 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-19 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-20 | Present study | N/A |

| GAI-21 | Present study | N/A |

| GSH | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #G4251 |

Experimental model and study participant details

Animals

All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Ethical Committee of Osaka Prefecture/Metropolitan University (approval number: S-09-23-085, S-09-23-088, S-18-23-08), and were performed according to the animal ethical guidelines of Osaka Prefecture/Metropolitan University. C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. C152A-Tg mice were generated as described below. Mice were housed in a temperature-controlled (23 ± 2°C) and humidity-controlled (50% ± 5%) animal facility with a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. Food (CLEA Japan, catalog number: CD-8) and ultrafiltered water were available ad libitum. Information regarding mouse sex, body weight (g), and age (w) is provided in the publicly accessible Mendeley Data (see https://doi.org/10.17632/r63n4pk94p.2 in the key resources table).

Generation of transgenic mice

The Tet-off expression vector pTRE2-GAPDH-myc, constructed by subcloning a Not I - Xba I fragment of GAPDH cDNA into the pTRE2-myc vector, was prepared from pTRE-GAPDH-myc as a template using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with the following oligonucleotides: sense 5′-ATCAGCAATGCCTCCGCCACCACCAAC-3′, antisense 5′-GTTGGTGGTGGCGGAGGCATTGCTGAT-3′. Successful point mutation was confirmed by sequencing. To generate the transgenic mice, pTRE-C152A-GAPDH-myc was digested with Xho I and Ase I, and the fragment containing the transgene was purified using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). The purified transgene was then injected into C57BL/6J mouse embryos by Oriental Bio Service (https://orientalbioservice.com/index.files/home_eng.htm) to generate the C152A-Tg mouse strain. Incorporation of the transgene was confirmed by PCR amplification with transgene-specific primers, using genomic DNA as the template. A second transgenic mouse strain, C152A-Tg strain 2, was generated using the same strategy to confirm our findings.

Method details

Chemicals, reagents, and peptide synthesis

Unless otherwise noted, chemicals were analytical grade.

GAPDH aggregation inhibitors

A series of GAPDH aggregation inhibitors was synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich-Japan-Genosys. The purity is over 95% assessed by a HPLC and a LC-MS.

Middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model

Right MCAO was performed as described previously with minor modifications.22 Mice were anesthetized with 1.0%–1.5% isoflurane in air and the rectal temperature was monitored using a rectal probe and maintained around 37°C by a thermostatically controlled heating pad and an overhead lamp (Fine Science Tools). Under an operating microscope, a silicon-coated 8-0 nylon thread was inserted into the right internal carotid artery through the right external carotid artery. Nylon thread was advanced 10 mm and middle cerebral artery was subjected to occlusion (ischemia), and then mice were recovered from anesthesia. Successful occlusion of middle cerebral artery was confirmed by the presence of neurological deficits including their paralysis of ipsilateral fore- and hind limb and asymmetric behavior during tail suspension. After 30 min-ischemia, mice were re-anesthetized and reperfusion of blood flow was achieved by the withdrawal of the thread.

Measurement of infarct volume

The assessment of infarct volume was performed 24 h after reperfusion as described previously.22 In brief, brain was removed rapidly and coronal slices (1 mm) were made using brain matrix (Neurosearch). Brain sections were immersed in 2% 2,3,5,-tripenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC, Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min, and then incubated with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, overnight. The infarct region which was not stained with TTC was measured using an ImageJ ver.1.51j8 (https://imagej.net/ij/index.html).

Fractionation and western blotting

To detect the GAPDH aggregates in the striatum of mice, fractionation of Triton-insoluble fraction was prepared as described previously.53 Mouse brains were quickly removed after decapitation and the striatum was dissected. The striatum was homogenized on ice for 30 s, three times with a sonicator (model Q-125, Qsonica LLC) in tissue lysis buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, 2 mM PMSF, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM NaF and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics). The samples were centrifuged at 20,400 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellets were resuspended with modified solubilization buffer containing 10 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, 3 mM DTT and protease inhibitor cocktail. The samples were sonicated and then centrifuged at 20,400 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellets were resuspended with 2× low sample buffer (final concentrations: 62.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 0.5% SDS and 10% glycerol). To detect both cytosolic cytochrome c and nuclear apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), cytosolic and nuclear fraction were prepared. The striatum was homogenized on ice with glass homogenizer in hypotonic buffer containing 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.5], 3 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitor cocktail. The homogenates were passed through a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Falcon), and the flow-through was then centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C; this produced both crude cytosolic supernatants and crude nuclear pellets. The crude cytosolic supernatants were further centrifuged at 20,400 × g for 10 min and the supernatants were used as cytosolic fraction. The crude nuclear pellets were resuspended and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 5 min in wash buffer containing 25 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.5], 3 mM MgCl2, 300 mM sucrose, 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitor cocktail. This washing step was repeated 3 times. The resultant pellets were resuspended with wash buffer, sonicated on ice for 10 s, and used as nuclear fraction. Protein concentrations were determined by BCA assay (Pierce). These samples were heated at 100°C for 5 min, separated by 5%–20% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore Japan, Tokyo, Japan). The membrane was incubated for 1 h with Blocking One (Nacalai Tesque) to block nonspecific binding. The membrane was then incubated overnight at 4°C with an anti-GAPDH monoclonal antibody (1:300), an anti-cytochrome c monoclonal antibody (1:500), an anti-AIF polyclonal antibody (1:10,000), an anti-triosephosphate isomerase (TPI) polyclonal antibody (1:5,000) or an anti-H2B polyclonal antibody (1:5000) in 10% Blocking One-PBST (0.05% Tween 20 and 0.02% NaN3 in PBS) followed by the incubation for 1 h at room temperature with a horseradish peroxide-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000 anti-mouse for GAPDH and cytochrome c or anti-rabbit for TPI and H2B IgG). Detection was performed using ECL plus and LAS3000 (FUJI-FILM). The intensity of the bands was measured by Multi Gauge Ver. 3.0 (FUJI-FILM).

Purification of tTA-AAV2

Recombinant AAV2 vectors for the expression of tTA were constructed as described previously.22,33 Briefly, the three plasmids (pAAV-MCS inserted with tTA cDNA: pAAV-FtTA, pAAV-RS, and pHelper; Agilent Technologies) were co-transfected to HEK293 cells at a ratio of 1:1:1 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The AAV2 particles were purified with a VIRA TRAP AAV Purification Maxi kit (Omega Bio-Tek) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The titer was determined with the AAV2 Titration ELISA Kit (PROGEN).

Intra-striatal/-cortical tTA-AAV2 injections

Injections were performed according to our previous report.22 The viral particles (2 × 1014/ml, 3 μl/site) were injected using a Hamilton syringe at the following sites: (I) AP: 0 mm, ML: 2.5 mm, DV: 3.5 mm, (II) AP: 1.0 mm, ML: 2.0 mm, DV: 3.5 mm, (III) AP: 1.5 mm, ML: 1.5 mm, DV: 3.2 mm at an injection rate of 1 μl/min. Two weeks after the viral injection, animals were continuously treated with Dox or left untreated.33

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were deeply anesthetized with 1.0%–1.5% isoflurane and transcardially perfused with ice-cold PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The brain was removed and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4°C overnight, stored in 30% sucrose in PBS at 4°C for 2–3 days, and then frozen at −80°C until sectioning. The frozen tissue was cut on a cryostat into 10 μm coronal sections. Sections were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS three times for 5 min each, then were incubated with 10% goat serum in PBS for 1 h at room temperature for blocking. Sections were incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-myc antibody (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by the incubation with Alexa 488-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:1000; Invitrogen) after washing three times. Stained sections were coverslipped in Fluorescein Mounting Medium (Dako) containing DAPI (DOJINDO), and fluorescent images were obtained using a confocal scanning microscope (model C1si-TE2000-E, Nikon). For identification of cells expressing C152A-GAPDH-myc derived from AAV2 infection, double immunostaining with mouse monoclonal anti-myc antibody (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and rabbit polyclonal anti-MAP2 antibody (1:500, Millipore) or with rabbit polyclonal anti-myc antibody (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and mouse monoclonal anti-GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) (1:500, Dako) was conducted.

Scoring of neurological deficits

Neurological deficits were assessed according to a published protocol with minor modification (normal score = 0, maximum score = 6).22 Briefly, the paralysis of both contralateral fore- and hindlimb were tested using the following criteria: 0 = absence of the paralysis, 1 = incomplete paralysis, and 2 = complete paralysis. Regarding asymmetric behavior, tail suspension test was performed using the following scale: 0 = contralateral forelimb touch to floor, 1 = some touch, 2 = no touch.

GAI-17 inhibition of GAPDH aggregation

The solution of GAPDH (5 μM) containing 0, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30, or 100 μM GAI-17 were added to each well of 96-well plate, followed by the incubation for 48 h at 37°C. The turbidity was measured spectrophotometrically by absorbance at 405 nm using VERSAMAX microplate reader (Molecular Devices Japan), and IC50 was calculated using GraphPad Prism (ver.10.2.2, GraphPad Software, Inc.).30

Docking simulation of GAI-17 and GAPDH

A structural model of human GAPDH (PDB code 1U8F) and GAI-17 (Ser-Cys-Thr) complex was generated using the data-driven docking program AutoDock Vina. The distance between cysteine residues was calculated by ‘wizard’ option for measuring distance in PyMol program.

Intracerebroventricular injection with GAI-17

For i.c.v. injection, mice were anesthetized with 1.0%–1.5% isoflurane in air and GAI-17 was manually injected into the right lateral ventricle (coordinate: 0 mm anterior to bregma, +0.8 mm lateral to midline, - 2.0 mm ventral to the skull surface) over 30 s through an infusion cannula (26-gauge stainless steel tubing, Eicom) connected to 10 μl Hamilton syringe. In the pre-treatment experiment, mice were i.c.v. injected with 10 or 20 nmol GAI-17 three times: 1 h before reperfusion, just after reperfusion, and 12 h after reperfusion. In the post-treatment experiment, mice were i.c.v. injected 30 nmol GAI-17 two times: 3, 6 or 9 h after reperfusion, and 12 h after reperfusion.

Recombinant GAPDH expression and purification

The pBAD-HisA vector (Invitrogen) carrying mouse GAPDH or human C152A-GAPDH cDNA was transformed into gap (−) Escherichia coli strain W3CG.26 Expression and purification of these recombinant GAPDH proteins were carried out as described previously.2 Protein concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically assuming a ε0.1% at 280 nm = 1.0.

GAI peptide inhibition of GAPDH aggregation

Human recombinant GAPDH solutions (5 μM) containing 0 or 50 μM GAI peptide were added to individual wells in a 96-well plate. The plates were incubated for 48 h at 37°C. The turbidity was measured spectrophotometrically by determining the absorbance at 405 nm on a VERSAmax microplate reader (Molecular Devices Japan).30

The effect of GAIs on cell viability

PC12 cells in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) were plated at a cell density of 3.13×105 cells/cm2 into a 96-well plate coated with 0.5 mg/ml poly-D-lysine hydrobromide. The cells were incubated for 72 h at 37°C with 1 mM of GAI peptide.30 The cell viability was measured using a Cell Titer Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay kit (Promega, WI) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

In vitro GAPDH aggregation assay

The GAPDH aggregation assay in vitro for purified proteins was performed basically according to published methods.26 Purified His-tagged mouse GAPDH (0.3 mg/ml) with His-tagged human C152A-GAPDH (0.3, 0.5, or 0.75 mg/ml) were mixed with or without pre-incubation for 24 h at 4°C, and then the mixtures were treated with 100 μM NOR3 (a NO generator, DOJINDO) for 24 h at 37°C. To measure the turbidity of the solutions, the absorbance at 405 nm was recorded using a VERSA Max microplate reader and SoftMax® Pro software (Molecular Devices Japan).

Genotyping of C152A-GAPDH transgenic mice

Transgenic founders were screened with two primer pairs (Primer-A and -B pairs) that amplified either a 200 bp DNA fragment within the TRE-CMV coding region (Primer-A pair; Forward; 5′-GGTACCCGGGTCGAGGTAGGCGTGT-3′ and Reverse; 5′-GAATTCGGGGCCGCGGAGGCT-3′) or a 200 bp DNA fragment within the GAPDH-C152A coding region (Primer-B pair; Forward; 5′-CCGTCAGATCGCCTGGAGACGCCAT-3′ and Reverse; 5′-TGGTGACCAGGCGCCCAATACGACC-3′).

Measuring GAPDH enzyme activity in the brain

GAPDH enzymatic activity was measured according to our published protocols.53 Brains were quickly removed after decapitation, and the striatum was dissected. The striatum was homogenized on ice for 30 s, 3 times with a sonicator (model Q-125, Qsonica LLC) in homogenizing buffer containing 10 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 8.0], 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitor cocktail. The homogenates were passed through a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Falcon), and the flow-through was then centrifuged at 900 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatants were further centrifuged at 20,400 × g for 10 min and the resultant supernatants were collected as enzyme extracts and used for the measurements of GAPDH enzyme activity. One mM NAD+, 2 mM glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, and 1 mg/ml enzyme extracts were mixed in Assay Mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.9], 0.2 mM EDTA/2Na, and 50 mM K2HPO4, and then monitoring the change in absorbance at 340 nm for 2 min using a VERSAMAX microplate reader (Molecular Devises, Japan).

Physiological characteristics

Mice were anesthetized with 1.0%–1.5% isoflurane in air and physiological parameters described below were analyzed 30 min before ischemia (pre) and just before reperfusion (post). The rectal temperature was measured using a rectal probe (Fine Science Tools). A non-invasive blood pressure monitor (Model MK-200ST, Muromachi Kikai) was used for the measurement of mean blood pressure and heart rate. Arterial blood samples withdrawn through PE-10 cannula inserted into the left femoral artery were analyzed with a gas analyzer (i-STAT 1, Abbot Point of Care Inc.) for PaO2, PaCO2, and pH. Regional cerebral blood flow was monitored by a laser tissue blood flowmeter (FLO-N1, Omegawave) with a probe fixed to the intact skull over the territory supplied by middle cerebral artery.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. from independent experiments as indicated the numbers (n) in each figure legend. Statistical analyses were carried out using Student’s t-test, one-way analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett’s multiple range test, and Mann–Whitney test (for neurological scoring) using GraphPad Prism (version 10.2.2, GraphPad Software, Inc.). Results with p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Published: May 2, 2025

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2025.112564.

Supplemental information

Each sheet is involved in these raw data in the related figures and tables (e.g., the designation “Figure 1C” on the sheet encompasses all the data presented in Figure 1C, including the sex and weight of each mouse).

References

- 1.GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20:795–820. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00252-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powers W.J., Rabinstein A.A., Ackerson T., Adeoye O.M., Bambakidis N.C., Becker K., Biller J., Brown M., Demaerschalk B.M., Hoh B., et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50:e344–e418. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung S., Gralla J., Fischer U., Mono M.L., Weck A., Lüdi R., Heldner M.R., Findling O., El-Koussy M., Brekenfeld C., et al. Safety of endovascular treatment beyond the 6-h time window in 205 patients. Eur. J. Neurol. 2013;20:865–871. doi: 10.1111/ene.12069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schellinger P.D., Thomalla G., Fiehler J., Köhrmann M., Molina C.A., Neumann-Haefelin T., Ribo M., Singer O.C., Zaro-Weber O., Sobesky J. MRI-based and CT-based thrombolytic therapy in acute stroke within and beyond established time windows: an analysis of 1210 patients. Stroke. 2007;38:2640–2645. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.483255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donnan G.A., Fisher M., Macleod M., Davis S.M. Stroke. Lancet. 2008;371:1612–1623. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qin C., Yang S., Chu Y.H., Zhang H., Pang X.W., Chen L., Zhou L.Q., Chen M., Tian D.S., Wang W. Signaling pathways involved in ischemic stroke: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022;7:215. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01064-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eltzschig H.K., Eckle T. Ischemia and reperfusion--from mechanism to translation. Nat. Med. 2011;17:1391–1401. doi: 10.1038/nm.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.George P.M., Steinberg G.K. Novel Stroke Therapeutics: Unraveling Stroke Pathophysiology and Its Impact on Clinical Treatments. Neuron. 2015;87:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White B.C., Sullivan J.M., DeGracia D.J., O'Neil B.J., Neumar R.W., Grossman L.I., Rafols J.a., Krause G.S. Brain ischemia and reperfusion: molecular mechanisms of neuronal injury. J. Neurol. Sci. 2000;179:1–33. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(00)00386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang M., Liu Q., Meng H., Duan H., Liu X., Wu J., Gao F., Wang S., Tan R., Yuan J. Ischemia-reperfusion injury: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024;9:12. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01688-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer-Siegler K., Mauro D.J., Seal G., Wurzer J., deRiel J.K., Sirover M.A. A human nuclear uracil DNA glycosylase is the 37-kDa subunit of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:8460–8464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh R., Green M.R. Sequence-specific binding of transfer RNA by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Science. 1993;259:365–368. doi: 10.1126/science.8420004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng L., Roeder R.G., Luo Y. S phase activation of the histone H2B promoter by OCA-S, a coactivator complex that contains GAPDH as a key component. Cell. 2003;114:255–266. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00552-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tisdale E.J. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate Dehydrogenase Is Required for Vesicular Transport in the Early Secretory Pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:2480–2486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007567200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai Y., Sweeny E.A., Schlanger S., Ghosh A., Stuehr D.J. GAPDH delivers heme to soluble guanylyl cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:8145–8154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.013802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Islam S., Jayaram D.T., Biswas P., Stuehr D.J. Functional maturation of cytochromes P450 3A4 and 2D6 relies on GAPDH- and Hsp90-Dependent heme allocation. J. Biol. Chem. 2024;300 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2024.105633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itakura M., Kubo T., Kaneshige A., Nakajima H. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase regulates activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase under oxidative stress. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023;657:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2023.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tristan C.A., Ramos A., Shahani N., Emiliani F.E., Nakajima H., Noeh C.C., Kato Y., Takeuchi T., Noguchi T., Kadowaki H., et al. Role of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) as an activator of the GAPDH-Siah1 stress-signaling cascade. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:56–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.596205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colell A., Ricci J.E., Tait S., Milasta S., Maurer U., Bouchier-Hayes L., Fitzgerald P., Guio-Carrion A., Waterhouse N.J., Li C.W., et al. GAPDH and Autophagy Preserve Survival after Apoptotic Cytochrome c Release in the Absence of Caspase Activation. Cell. 2007;129:983–997. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hara M.R., Agrawal N., Kim S.F., Cascio M.B., Fujimuro M., Ozeki Y., Takahashi M., Cheah J.H., Tankou S.K., Hester L.D., et al. S-nitrosylated GAPDH initiates apoptotic cell death by nuclear translocation following Siah1 binding. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:665–674. doi: 10.1038/ncb1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakajima H., Amano W., Fujita A., Fukuhara A., Azuma Y.T., Hata F., Inui T., Takeuchi T. The active site cysteine of the proapoptotic protein glyceraldehyde-3- phosphate dehydrogenase is essential in oxidative stress-induced aggregation and cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:26562–26574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704199200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakajima H., Kubo T., Ihara H., Hikida T., Danjo T., Nakatsuji M., Shahani N., Itakura M., Ono Y., Azuma Y.T., et al. Nuclear-translocated glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase promotes Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 activation during oxidative/nitrosative stress in stroke. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:14493–14503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.635607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sen N., Hara M.R., Ahmad A.S., Cascio M.B., Kamiya A., Ehmsen J.T., Agrawal N., Hester L., Doré S., Snyder S.H., Sawa A. GOSPEL: a neuroprotective protein that binds to GAPDH upon S-nitrosylation. Neuron. 2009;63:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sen N., Hara M.R., Kornberg M.D., Cascio M.B., Bae B.-I., Shahani N., Thomas B., Dawson T.M., Dawson V.L., Snyder S.H., Sawa A. Nitric oxide-induced nuclear GAPDH activates p300/CBP and mediates apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:866–873. doi: 10.1038/ncb1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakajima H., Amano W., Fukuhara A., Kubo T., Misaki S., Azuma Y.T., Inui T., Takeuchi T. An aggregate-prone mutant of human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase augments oxidative stress-induced cell death in SH-SY5Y cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;390:1066–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakajima H., Amano W., Kubo T., Fukuhara A., Ihara H., Azuma Y.T., Tajima H., Inui T., Sawa A., Takeuchi T. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase aggregate formation participates in oxidative stress-induced cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:34331–34341. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.027698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kubo T., Nakajima H., Nakatsuji M., Itakura M., Kaneshige A., Azuma Y.T., Inui T., Takeuchi T. Active site cysteine-null glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) rescues nitric oxide-induced cell death. Nitric Oxide. 2016;53:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakajima H., Itakura M., Kubo T., Kaneshige A., Harada N., Izawa T., Azuma Y.-T., Kuwamura M., Yamaji R., Takeuchi T. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH) Aggregation Causes Mitochondrial Dysfunction during Oxidative Stress-induced Cell Death. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:4727–4742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.759084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka R., Mochizuki H., Suzuki A., Katsube N., Ishitani R., Mizuno Y., Urabe T. Induction of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression in rat brain after focal ischemia/reperfusion. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:280–288. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Itakura M., Nakajima H., Semi Y., Higashida S., Azuma Y.T., Takeuchi T. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase aggregation inhibitor peptide: A potential therapeutic strategy against oxidative stress-induced cell death. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;467:373–376. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.09.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu G., Liang Y., Huang Z., Jones D.W., Pritchard K.A., Jr., Zhang H. Inhibition of myeloperoxidase oxidant production by N-acetyl lysyltyrosylcysteine amide reduces brain damage in a murine model of stroke. J. Neuroinflammation. 2016;13:119. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0583-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hara M.R., Thomas B., Cascio M.B., Bae B.I., Hester L.D., Dawson V.L., Dawson T.M., Sawa A., Snyder S.H. Neuroprotection by pharmacologic blockade of the GAPDH death cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:3887–3889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511321103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hikida T., Kimura K., Wada N., Funabiki K., Nakanishi S. Distinct roles of synaptic transmission in direct and indirect striatal pathways to reward and aversive behavior. Neuron. 2010;66:896–907. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klein R.L., Meyer E.M., Peel A.L., Zolotukhin S., Meyers C., Muzyczka N., King M.A. Neuron-specific transduction in the rat septohippocampal or nigrostriatal pathway by recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. Exp. Neurol. 1998;150:183–194. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tristan C., Shahani N., Sedlak T.W., Sawa A. The diverse functions of GAPDH: Views from different subcellular compartments. Cell. Signal. 2011;23:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eberhardt J., Santos-Martins D., Tillack A.F., Forli S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021;61:3891–3898. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R.K., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]