Abstract

Tracheo-bronchial compression is a complication of vascular congenital and acquired anomalies, usually associated with double aortic arch, aberrant subclavian artery, pulmonary artery sling, Kommerell’s diverticulum, and with aneurysms of the aortic arch and thoracic aorta.

In this report we present a case of a 75-year-old male with incidental diagnosis of tracheal compression by a thoracic aorta aneurysm combined with anatomical variant of the right subclavian artery, that came up to our attention because of the onset of a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) caused by a bilobar shaped anterior cerebral artery aneurysm rupture.

Keywords: Aberrant subclavian artery, Thoracic aorta aneurysm, Tracheal compression, Vascular anomalies

Introduction

Tracheo-bronchial compression can be congenital or acquired. It is usually associated, indeed, with double aortic arch, aberrant subclavian artery, pulmonary artery sling, whereas it is rarely combined with Kommerell’s diverticulum; aneurysms of the aortic arch and descending thoracic aorta can also be a cause of airway compression [1].

There is a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations associated with tracheo-bronchial compression, ranging from asymptomatic and/or chronic conditions to those pathological abnormalities that may lead to acute respiratory failure [2].

A prompt and systematic diagnosis of underlying vascular and tracho-bronchial anomalies is crucial in symptomatic respiratory obstructions: not only because these conditions can lead to detect their possible vascular disorder origin, but it can also help to focus on associated intrinsic structural anomalies of the airway system that may coexist as separate entities [1,2].

Case report

In this report we present a case of a 75-year-old white male patient, who prompted to the emergency room (ER) presenting with stupor as a single isolated symptom, without any difficult in swallowing, and silent pathological remote history except for hypertension for which he was on a single drug therapy regimen. On physical examination, the patient exhibited normal respiratory rate, cardiac function, and pulse rate, with no signs of edema in the lower limbs. All peripheral pulses were palpable, and lung auscultation was unremarkable. The abdomen was nontender to both superficial and deep palpation, and there were no other notable clinical findings. Neurological assessment revealed no abnormalities. Blood test scores at admission are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Blood test results at ER arrival.

| Results | Normal range | |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 13.3 g/dL | 13.2-16.6 g/dL |

| Erythrocytes | 4.39 × 1012/L | 4.7-6.1 × 1012/L |

| Leucocytes | 15.02 × 109/L | 5-10 × 109/L |

| Neutrophiles | 13.6 × 109/L | 2.5-7 × 109/L |

| Platelets | 233.0 × 103/μL | 150-400 × 103/μL |

| Fibrinogen | 535.0 mg/dL | 200-400 mg/dL |

| Azotemia | 61.0 mg/dL | 15-50 mg/dL |

| LDH | 378.0 mU/mL | 140-280 mU/mL |

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

An initial unenhanced brain CT scan revealed a bilateral subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), primarily affecting the temporo-parietal and frontal lobes, with blood present in the ventricular system, cisterna magna, third ventricle, and occipital horns, which led to the development of hydrocephalus (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pretreatment cranial CT scan image. Unenhanced Axial MDCT Scan showing blood-CSF levels in both lateral ventricles which is consistent with emoventricle. Blood-like hyperdensity in right side subharchnoid spaces of the convexity of fronto-temporal-parietal lobes, cisterna magna and third ventricle are consistent with SAH.

A follow-up CT scan conducted days later revealed a 4-mm bilobed aneurysm along the left anterior cerebral artery (Figs. 2,3).

Fig. 2.

Post-treatment cranial CT scan image. Enhanced Axial MDCT Scan showing blood-CSF levels in both lateral ventricles which are consistent with emventricle.

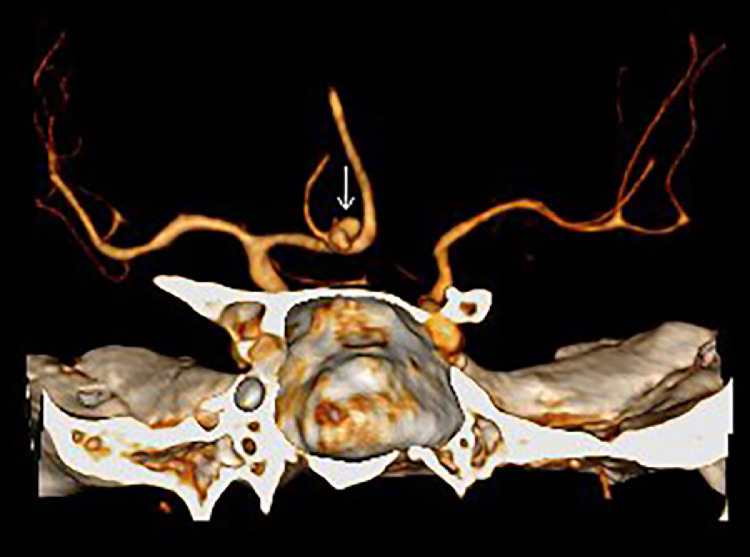

Fig. 3.

Volume rendered image of vascular structures. Ruptured aneurysm of anterior communicating artery is clearly visible.

Given the persistent coma and need for mechanical ventilation, tracheal intubation was performed, followed by percutaneous tracheotomy to facilitate neurosurgical intervention. Postsurgery, a chest CT scan performed on post-op day 10 revealed progressive improvement of the SAH, but also the emergence of pneumomediastinum. In addition, a retro-tracheal and retro-esophageal aneurysm of the aortic arch of almost 6cm was detected (Figs. 4,5). Fiberoptic examination revealed significant tracheal narrowing, with a mass abutting the posterior tracheal wall (Figs. 6,7).

Fig. 4.

Sagittal chest CT scan image. Unhenanced MDCT of the thorax oblique view. A retro-tracheal and retro-esophageal aneurysm of the aortic arch is well detected (white arrow).

Fig. 5.

Axial chest CT scan image. CE-MDCT of the thorax axial view. A huge thoracic aorta aneurysm abutting the esophagus and trachea is visible. Note the tracheal cannula indwell.

Fig. 6.

Fiberoptic evaluation that showed a protruding mass at the posterior wall of the trachea with partial occlusion of the portion of the lumen.

Fig. 7.

Fiberoptic evaluation corresponding to the distal part of the tracheostomy cannula, with sufficient respiratory space revealed.

The partially occluded tracheal lumen at distal end of the tracheostomy cannula was also described. At this point, a surgical intervention to fix the vascular disorder was not considered. It was planned a 3 month radiologic and endoscopic follow-up, and a consequent calendarization on the basis of its findings.

Discussion

Tracheo-bronchial obstruction is usually caused by vascular anomalies, because of the close anatomic relationship between the aortic arch and the trachea and left main stem bronchus [1]; on the other hand, this abnormality is very rare in conjunction with other thoracic aneurysms [3]. Airway compression syndrome is commonly associated with double aortic arch, arteria lusoria, pulmonary artery sling, Kommerell’s diverticulum [2], and thoracic aorta aneurysms; however, patients with these anatomical variants may be usually asymptomatic and incidental diagnosis is carried out at work-up for different purposes. [1]. Symptoms vary according to the size, location, and different changes of the aneurysm shape and enlargement: they can range from asymptomatic compression to the true evidence of chest, back, and abdominal pain.

Wheezing, dyspnea, cough, or hoarseness may arise when vagus nerve or left recurrent laryngeal nerve are compressed [1,2].

The case presented in this report was completely asymptomatic despite the presence of the vascular anomaly. As described in the international literature, this latter anomaly is often asymptomatic and occurs in 0.4%-2-3% of the population. It is due to the persistence of the dorsal segment of the right aortic arch, that give rise to an aberrant origin of the right subclavian artery, passing behind the course of trachea and esophagus and leading to reach the right upper limb [4]. In our reported case, it may be that the patient was predisposed to vascular defect or abnormalities, and this could explain both cranial and chest vascular findings.

At infancy, in particular, thoracic vascular anomalies are potentially life threatening but undoubtedly are the cause of tracheo-bronchial obstruction [4,5]. As said before, compression symptoms rarely appear in adulthood and adult patients may be misdiagnosed for a long period of time [[6], [7], [8]]. In such cases, symptoms may not be relieved by surgical intervention because long-term compression may lead to remodelling of the trachea shape and to tracheomalacia that is very often observed especially when the aortic aneurysm enlargement is able to create a posterior hollow expansion abutting the respiratory tract.

Therefore, in adult cases, optimal treatment decision-making is sometimes difficult [6].

It is crucial to proceed with optimal imaging exams such as CT scan, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Angiography and trans-oesophageal Echocardiography are most often carried out to assess a thoracic aneurysm [9]. In some cases it is also important to enhance diagnostic steps by means of multidisciplinar and endoscopic methods.

Only at a postsurgery chest CT scan we found out that, except for pneumomediastinum, the patient of this report also had a retro tracheal and retro oesophageal course of the aortic arch, together with enlargement of thoracic descending aorta. In this situation, a fiberoptic evaluation helped us to detect the protruding intra-tracheal mass due to the vascular anomaly that seriously restricted the tracheal lumen. An evaluation with flexible bronchoscope, in these cases, may help with the inspection of all the accessible airway tracts, the assessment of intraluminal tissue properties of the airway wall, and the effective direct clearing of retained mucosal fluids in case of decompression [10].

Conclusions

In conclusion, an optimal treatment decision-making is often difficult in cases of airway obstruction due to vascular anomalies which are asymptomatic in most of the cases in adult patients. It is thus important for the physician to be aware of the possibility of an underlying vascular anomaly. In these cases, it is necessary to proceed with a strict diagnostic flowchart, imaging modalities, and fiberoptic evaluation, in order to be able to choose case by case the best treatment strategy. The integration among multidisciplinary approach, radiologic and endoscopic methods, and calendarized follow-up, should be ever pointed-out as fundamental for vascular anomalies involving airways structures.

Patient consent

This to certify on behalf of all authors that we submitted the informed consent to the patient, and that the patient accepted and signed it confirming his consent to use radiologic imagings and endoscopic findings for scientific divulgation of his case. Authors confirmed to the patient that his name will not appear on that paper.

Footnotes

Data generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

Acknowledgments: No fundings to declare.

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Kumar A., Dutta V., Negi S., Puri G.D. Vascular airway compression management in a case of aortic arch and descending thoracic aortic aneurysm. Ann Card Anaesth. 2016;19(3):568–571. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.185568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komarov R., Ismailbaev A., Kurasov N., Ivashov I., Saliba M., Danachev A. Aortic arch aneurysm. Tracheobronchial compression as a vital indication for emergency surgery: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2021;85 doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2021.106218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charrette E.J., Winton T.L., Salerno T.A. Acute respiratory insufficiency from an aneurysm of the descending thoracic aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1983;85(3):467–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malik T.H., Bruce I.A., Kaushik V., Wright N.B., Rothera M.P. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of suspected extrinsic tracheobronchial compression due to vascular anomalies. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(1):52–55. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.070250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lincoln J.C., Deverall P.B., Stark J., Aberdeen E., Waterston D.J. Vascular anomalies compressing the oesophagus and trachea. Thorax. 1969;24(3):295–306. doi: 10.1136/thx.24.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwin F. Aortic arch anomalies–persistent fifth aortic arch remnant. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;12(1):71–72. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2010.246462A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geva T., Ray R.A., Santini F., Van Praagh S., Van Praagh R. Asymptomatic persistent fifth aortic arch (congenital double-lumen aortic arch) in an adult. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65(20):1406–1407. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)91339-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinberg P.M. Aortic arch anomalies. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2006;8(4):633–643. doi: 10.1080/10976640600713756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imanishi N., Takenaka M., Nabe Y., Nishimura Y., Tanaka F. Successful surgical treatment with tracheal resection for a symptomatic vascular ring in an adult. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;67(3):336–339. doi: 10.1007/s11748-018-0962-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sebening C., Jakob H., Tochtermann U., Lange R., Vahl C.F., Bodegom P., et al. Vascular tracheobronchial compression syndromes– experience in surgical treatment and literature review. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;48(3):164–174. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]