Summary

Around the world, institutional trust is declining while democratic discontent is rising. What role do health and health systems play in this crisis? We review decades of interdisciplinary research to describe how health and health systems are linked to democratic trust and engagement. When individuals or communities experience a decline in their health, they feel “let down” by the health system and other public institutions meant to support their well-being. Consequently, they are less likely to vote. Those who continue to vote are increasingly drawn to anti-establishment, anti-democratic parties that promise to radically reform the system. Once in power, however, these parties often weaken public health protections or exclude select populations from the health system. The result can be a self-reinforcing feedback loop between declining health and political discontent. We conclude by offering concrete suggestions for improving population health while rebuilding trust in health systems and democratic institutions more broadly.

Keywords: Health politics, Political determinants of health, Health policy, Trust

Introduction

Democratic backsliding is on the rise across the U.S. and Europe, with anti-democratic political actors and parties rising to power in several countries.1 Many members of the public have lost faith in their public institutions, elections, and even the democratic process. Do health and the health system have a role in this crisis of democracy?

An increasing volume of research suggests that individual and community health influences people’s politics.2 There have been years of studies showing the impact of health status on the economy, educational attainment, and poverty.3,4 Now, they are matched with research on the benefits of better health for political engagement — and the negative impact of declining health on democratic societies. Given that population health improvements in Europe and the U.S. might be leveling off or even declining in some areas, even before the pandemic,5, 6, 7 the political relevance of health should have our attention as we try to understand and learn from seismic political events such as Brexit, the rise of far-right parties in Europe, and the continued popularity of politicians like Donald Trump.

In this Personal View, we review decades of research on the connection between health and politics. When individuals or communities experience a decline in their health, they feel “let down” by the health system and other public institutions meant to support their well-being. Consequently, they are less likely to vote.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Those who continue to vote are increasingly drawn to anti-establishment, anti-democratic parties that promise to radically reform the system.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Once these extremist parties are in power, however, they rarely pursue a health-promoting agenda. Instead, they often weaken public health protections or exclude select populations, such as migrants, from the health system.20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 The result can be a self-reinforcing feedback loop between declining health and political discontent.

The sizes of the effects are impressive, but an even more important message emerges: Poor health appears to drive a loss of overall trust and personal agency, with consequences for politics. It is increasingly clear that poor health and disability reduce people’s trust in institutions, extending from the health system to governments to democracy itself. Worse health does not automatically make people less trusting, but it creates abundant opportunities for health systems and other public institutions to make them less trusting.

To be sure, health is not the primary determinant of most people’s politics. Health is deeply intertwined with social and economic conditions, making it challenging to identify whether health or another influence is the main driver of someone’s politics.4 Researchers have used a variety of methodological approaches to disentangle these influences, some approaches being purely descriptive and others with well-defined counterfactuals, yet uncertainty remains. Even so, across diverse study designs, data sources, and cultural and political contexts, it is clear that health and politics are closely linked to one another.

The research we review suggests a practical remedy that can be prescribed to both medicine and politics. If poor health creates circumstances that can contribute to a loss of trust in institutions that, in turn, spills over into political choices, then medicine and health policy can be part of a twofold solution. First, it is possible to improve health through the actions of clinicians and policy makers alike. Second, it is possible to increase, rather than decrease, the trust of people in poor health by welcoming them into care and providing it in a way that respects their agency and dignity. The magnitude of the relationship between health and politics is impressive, but so is the mechanism, because if the problem is loss of trust, then clinicians and the health system can be part of the solution.

How health status shapes political trust and engagement

People can be politically active in several ways. They can attend rallies, post on social media, give money, vote, and more. Each action requires different resources like time, money, or interest.26 However, a decline in health can change our ability and motivation to engage in these activities. It can limit mobility, making it harder to get to the polls; it can lead us to leave the workforce, restricting income for donating; or it can lead to frustrations with the system, raising the appeal of politicians that promise to fix what is “broken.”

Health is an undercurrent shaping politics in ways that might not be obvious. We begin our discussion by reviewing how health and experiences with health care impact trust in the health system and other public institutions. This trust, in turn, shapes people’s political preferences and behaviors. Consequently, whether the health system does — or doesn’t — meet the needs of the public may contribute to the stability of democratic institutions.

Health, the health system, and trust in public institutions

While many people are healed and affirmed by the health system, others aren’t so lucky. Many patients cannot access the health system due to structural barriers. Of those who do, many encounter stigma and demeaning interactions with clinicians due to their health conditions, including mental illness,27 substance use disorders,28 or weight,29 as well as their social identities, including gender and sexuality,30 race or migrant status,31 and religion.32 These experiences are not just the imaginings of patients; many clinicians openly report prejudice and discriminatory attitudes about patients’ conditions and identities.33,34 Recipients of social programs report similarly unpleasant experiences with administrators as they navigate these programs,35 with worse stigma for those in poorer health.36

Partly due to these experiences, poor health and disability are some of the most robust predictors of negative attitudes about the health system.37 The relationship is consistent across several measures of physical and mental health, national and cultural contexts, and diverse measures of trust, satisfaction, and confidence in the quality and reliability of the system’s care.37, 38, 39 Researchers have extensively documented the negative consequences of mistrust in the health system for people’s willingness to engage with it.40

Interestingly, unlike assessments about the health system, patients tend to report high trust in their individual clinicians.41 As we note below, building on this trust might offer a feasible pathway toward rebuilding trust and confidence in the larger system.

But beyond impacts on the health system itself, an under-appreciated consequence of this mistrust is its effects on other public institutions. For many patients, the health system is the face of the government with which they interact the most. Majorities or near-majorities of respondents across countries identify the government as responsible for providing health care to the sick — and want the government to intervene more on health.42, 43, 44 This is true even in countries with highly privatized health systems, such as the U.S.42

Consequently, negative experiences with the health system can damage perceptions of public and democratic institutions more generally.45 Poorer assessments of health system performance have been linked with decreased trust in government across 38 countries.46 Similarly, a study of 19 European countries found that people in poor health reported less trust in not only the health system but also the political system as a whole.47 In this way, experiences with the health system can have a ripple effect that extends far beyond it.

Health, political attitudes, and democratic participation

Trust is an essential ingredient in the performance of democratic institutions, as people will only engage with a political system they trust to work.45,48, 49, 50 Given the pervasive ways that health and experiences with the health system shape institutional trust, these same forces may shape people’s political attitudes, preferences, and behaviors.

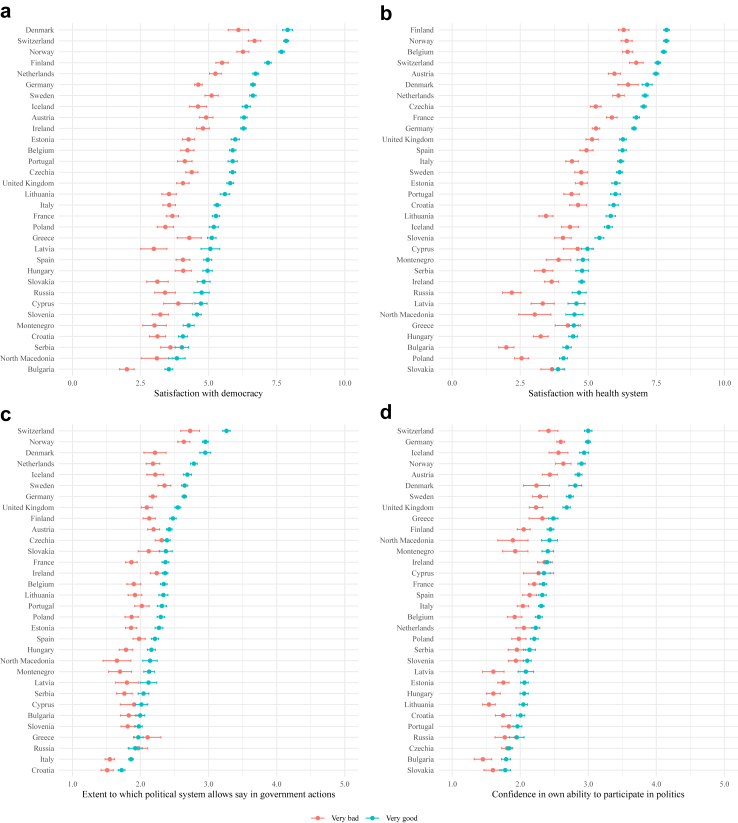

In Fig. 1, we use European Social Survey data from 32 countries between 2016 and 2022 to visualize country averages for satisfaction with democracy, satisfaction with the health system, belief that the political system gives individuals a say in how government works, and confidence in one’s own ability to participate in politics. Fig. 2 examines the relationship between self-reported general health and these political attitudes.51 Across nearly all countries, people in poor health are significantly less satisfied with their institutions and less likely to believe that the government welcomes their input.

Fig. 1.

Country averages of institutional trust and political efficacy for Europeans. Notes: Based on pooled responses to the European Social Survey in 32 countries from 2016 to 2022 (N = 149,386), as all four outcomes were asked in these years. For the top panels, respondents were asked to rate their satisfaction with (a) the way democracy works in their country and (b) the health system of their country from “extremely dissatisfied” (0) to “extremely satisfied” (10). For the bottom panels, respondents were asked to report (c) the extent to which the political system allows them a say in government actions from “not at all” (1) to “a great deal” (5) and (d) their confidence in their own ability to participate in politics from “not at all confident” (1) to “completely confident” (5). Each country is shaded based on the average for each variable calculated using post-stratification weights. Analyses were performed using the “survey” package (v. 4.4-2) in R (v. 4.4.0).

Fig. 2.

Adjusted levels of institutional trust and political efficacy for Europeans reporting “very good” and “very bad” health. Notes: Based on pooled responses to the European Social Survey in 32 countries from 2016 to 2022 (N = 149,386), as all four outcomes were asked in these years. Respondents were asked to rate their general health from “very bad” (1) to “very good” (5). For the top panels, respondents were asked to rate their satisfaction with (a) the way democracy works in their country and (b) the health system of their country from “extremely dissatisfied” (0) to “extremely satisfied” (10). For the bottom panels, respondents were asked to report (c) the extent to which the political system allows them a say in government actions from “not at all” (1) to “a great deal” (5) and (d) their confidence in their own ability to participate in politics from “not at all confident” (1) to “completely confident” (5). We treated all measures as continuous and used OLS models to estimate the association between self-reported general health and each outcome within each country, using post-stratification weights and adjustments for age, gender, and years of education. Then, we plotted predicted levels of the outcomes for men in “very bad” and “very good” health at the mean age and years of education in each country. Horizontal bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Analyses were performed using the “survey” package (v. 4.4-2) in R (v. 4.4.0).

Consequently, people in poor health often disengage from participating in politics, at least in the form of voting. Across numerous studies in diverse sociopolitical contexts, poor health and disability lead to double-digit declines in the rates of voting.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Issues of mobility loom especially large for this population. This disengagement can mean that elected officials do not adequately represent their interests.52 Notably, people in poor health often engage in other forms of political participation, including letter writing, protests, and more.8,53,54 Patient advocacy groups also help indirectly represent this population in the political process.

Among people who continue to participate in politics, declines in health can push their political attitudes toward the extremes. A few decades ago, people with poor health tended to support parties promoting investments in health care and social services.11,55, 56, 57 These parties were typically on the mainstream left. However, recent evidence suggests that this population now gravitates toward the extremes, especially the far right.16 Individuals and communities with poor health or disability are more likely to vote for anti-establishment populist movements, including President Trump, Brexit, and radical right parties like the Alternative for Germany, the Austrian Freedom Party, the Brothers of Italy, Vox in Spain, the National Rally in France, and the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands, among others.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Meanwhile, experiences with COVID-19 made people more likely to support populist policy priorities.58 A similar shift in the political preferences of people with poor health has happened before. During the early twentieth century, rising mortality in Germany and Italy were linked to greater support for the Nazi and Fascist Parties.59,60

Why does illness push some people to sit out of politics and others to radicalize? The literature has yet to answer this question, but it does provide some clues. For example, ill health appears to be mobilizing for younger people and de-mobilizing for older ones.53 Some conditions are more mobilizing than others, such as diabetes and cancer, which have powerful social groups that help organize the political action of patients and their families.61,62 These findings suggest that the specific experiences accompanying an illness and our social identities can intersect to shape our political response to illness.

Taken together, this evidence marks health and the health system as players in the game of politics. Far from being apolitical observers, they help shape people’s trust in public institutions, political priorities, and engagement in democratic processes. As a result, clinicians and policy makers have an opportunity to regain the public’s trust and encourage populations who otherwise would not engage in politics to make their voices heard.

How anti-establishment politics affect health

In the past twenty years, anti-democratic populist movements have risen in popularity by appealing to populations who are dissatisfied with public institutions — including those in poor health.63,64 Parties like those listed above, mostly on the ideological far right, are an increasingly powerful force in Western politics, upending older voting patterns and entering government in more places. What are the health consequences of a rise in these anti-democratic political parties? What do right-wing populists do to health systems?

The most common playbook is that right-wing populist politicians promise better health systems that will exclude select populations, such as migrants, from them.20, 21, 22, 23 Experts call this approach “welfare chauvinistic.” What is then delivered once in office typically follows the more classic, fiscally conservative approach of tightening budgets, weakening health regulations, and redistributing positions of power.24,25 These policies leave unions at a greater disadvantage and erode public health protections.24,25 In addition to this approach to policy, corruption often increases under right-wing populist leadership.24,25

Another common scenario involves right-wing populist politicians' making little effort to strengthen or reform health systems, despite their promising rhetoric, as they do not see health as a winning issue.65 Instead, they prefer to elevate other political issues or reframe health policy debates into discussions focused on their preferred topics, like migration.65 In some cases, they see the health system as an opportunity to reward supporters with contracts and benefits rather than as an opportunity to win over voters.24,66,67

Meanwhile, populist parties can indirectly worsen public health by amplifying conspiracy theories linked to health, such as discredited assertions linking vaccination to negative health outcomes.68,69 These communications might especially resonate with populations that feel alienated by the broader society, further entrenching their mistrust of government and belief that other groups in society are acting against their interests.70 These messages can also shape their health behaviors. For example, many people on the populist right were less likely to engage in preventive behaviors for COVID-19 — and more likely to die from it.71, 72, 73, 74

Regardless of the exact channel through which populist parties degrade public health and the health system, populations in poor health do not get the systemic improvements to the “broken” system that they were promised. Rather, the policies risk creating a “doom loop,” wherein individuals or populations in poor health become increasingly frustrated with their conditions, leading to even more mistrust in the health system and public institutions. This frustration leads them back to anti-establishment and anti-democratic parties.

Of note, this approach poses a political risk for these parties, as worsening health could cost them voters if they are perceived as responsible. However, the critical step is being perceived as responsible. In proportional representation systems, accountability is often obscured by coalition governments. In these contexts, anti-establishment parties can evade responsibility for their policies’ negative public health impacts while continuing to position themselves as champions of the vulnerable and marginalized. In two-party systems, such as the U.S., voters typically only have two choices. Anti-incumbent sentiment among voters can lead them to simply vote against the incumbent government without much thought as to what the opposition plans to do once in power.

What can health systems and policy makers do to promote inclusive politics?

Taken together, evidence from multiple disciplines suggests that people’s health and interactions with the health system inform their politics. When the health of a person or community declines, they are more likely to mistrust the public institutions meant to serve them and disengage from the democratic process, at least in the form of voting. If they continue to vote, they often gravitate toward the political extremes. To be sure, health is closely tied to other socioeconomic and cultural forces, which can make causal identification in this setting challenging. But even so, this literature makes clear that clinicians, policy makers, and political actors must pay more attention to the political needs of people in poor health to maintain an inclusive, functional democracy. We summarize our recommendations for each stakeholder below and in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of recommendations to promote inclusive politics.

| Stakeholder | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Clinicians & health systems |

|

| Policy makers and political actors |

|

For clinicians and health systems, these findings highlight the importance of access to and positive experiences with care, especially for communities that feel the most alienated from the health system (Table 1). Luckily, even when patients have low trust in the overall system, they often retain high trust in their personal clinicians, not unlike how a voter might disapprove of the larger political system but approve of their own elected representative.41 As such, clinicians can help rebuild trust in both the health system and public institutions more generally. When clinicians provide accessible, respectful, and affirming care without discrimination or judgment, they can enhance the inclusivity of their community’s politics. In these ways, clinicians and the health system nurture linking social capital — the vertical social ties that connect patients to structural resources.75 This engagement, in turn, can help patients to better integrate with the world around them and have their needs met.

To be clear, experiences with the health system are not the sole determinants of a person’s politics, nor are clinicians solely responsible for solving our crisis of democracy. Health care is not even the sole determinant of health, as social and economic structures heavily contribute.4 As such, policy action is essential for promoting both health and inclusive politics.

For policy makers and political actors, these findings emphasize the importance of promoting public health and fostering the civic engagement of neglected populations (Table 1). Luckily, there are opportunities to promote health even in policies designed for other purposes, as social programs, educational opportunities, and economic policies can all impact health.76 The public is more likely to reward political actors for health-promoting policies when those policies are universal, rather than means-tested; provide meaningfully large benefits and affirming experiences, rather than stigmatizing ones; and are visible and attributable to the government, rather than buried in complex tax codes.35,77, 78, 79

Structural changes take time, so policy makers and political actors can also act in the nearer term to engage populations that struggle to participate in politics. Leaders can increase the accessibility of voting and, between elections, directly solicit the opinions of people in poor health, patient advocacy groups, and health professional societies on relevant matters.52,61,62,80 Doing so can help ensure that more populations’ needs are represented in government policy.

Importantly, given the greater mistrust of public institutions among marginalized and alienated communities, policy makers should focus on not only improving communities’ access to health care and positive experiences with the health system but also ensuring that such efforts are communicated in a manner that underscores respect for individual dignity and agency. Prioritizing engagement with alienated communities could help to rebuild trust in the health system and government institutions more broadly.

Health and politics exist in a self-reinforcing cycle. Decisions that clinicians and policy makers make about the health system or other health-related policies shape not only patients’ well-being but also their politics, which then “feed back” into the political system via elections and other civic engagement. As such, meeting the needs of patients — or failing to do so — can loom over our democratic institutions. Several crises threaten population health across the world, including the aftermath of COVID-19, climate change, forced migrations, and more. How governments and health systems respond to these crises will be telling, with implications for not only the public’s health but also its engagement in participatory democracy.

Search strategy and selection criteria.

References for this viewpoint were identified through searches of PubMed using the search terms “health and politics”, “health and political engagement”, “health and turnout”, “health and voting”, “health and populism”, “political trust”, “political determinants of health”, and similar terms. Articles were also identified using the reference lists of resulting articles and through searches of the authors’ own files. Only papers published in English were reviewed. The final reference list was generated based on originality and relevance to the broad scope of this Personal View.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the conceptualization of the study, writing of the original draft, review, and editing. AM and NMK contributed to the data curation, formal analysis, and visualization. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Editor note

The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Declaration of interests

None.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- 1.Waldner D., Lust E. Unwelcome change: coming to terms with democratic backsliding. Annu Rev Polit Sci. 2018;21:93–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-050517-114628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kavanagh N.M., Menon A. World Health Organization, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2024. Health as a driver of political participation and preferences: implications for policy makers and political actors.https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/health-as-a-driver-of-political-participation-and-preferences-implications-for-policy-makers-and-political-actors [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woolf S.H., Braveman P. Where health disparities begin: the role of social and economic determinants—and why current policies may make matters worse. Health Aff. 2011;30(10):1852–1859. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braveman P., Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(1_suppl2):19–31. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Case A., Deaton A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(49):15078–15083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518393112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackenbach J.P., Karanikolos M., McKee M. The unequal health of Europeans: successes and failures of policies. Lancet. 2013;381(9872):1125–1134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.OECD. European Union . OECD; 2022. Health at a glance: Europe 2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattila M. Does poor health mobilize people into action? Health, political trust, and participation. Eur Polit Sci Rev. 2020;12(1):49–65. doi: 10.1017/S175577391900033X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schur L., Adya M. Sidelined or mainstreamed? Political participation and attitudes of people with disabilities in the United States. Soc Sci Q. 2013;94(3):811–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2012.00885.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shields T.G., Schriner K.F., Schriner K. The disability voice in American politics: political participation of people with disabilities in the 1994 election. J Disabil Pol Stud. 1998;9(2):33–52. doi: 10.1177/104420739800900203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pacheco J., Fletcher J. Incorporating health into studies of political behavior: evidence for turnout and partisanship. Polit Res Q. 2015;68(1):104–116. doi: 10.1177/1065912914563548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsubayashi T., Ueda M. Disability and voting. Disabil Health J. 2014;7(3):285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burden B.C., Fletcher J.M., Herd P., Jones B.M., Moynihan D.P. How different forms of health matter to political participation. J Polit. 2017;79(1):166–178. doi: 10.1086/687536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bor J. Diverging life expectancies and voting patterns in the 2016 US presidential election. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(10):1560–1562. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bilal U., Knapp E.A., Cooper R.S. Swing voting in the 2016 presidential election in counties where midlife mortality has been rising in white non-Hispanic Americans. Soc Sci Med. 2018;197:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kavanagh N.M., Menon A., Heinze J.E. Does health vulnerability predict voting for right-wing populist parties in Europe? Am Polit Sci Rev. 2021;115(3):1104–1109. doi: 10.1017/S0003055421000265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldman L., Lim M.P., Chen Q., Jin P., Muennig P., Vagelos A. Independent relationship of changes in death rates with changes in US presidential voting. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3):363–371. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4568-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wasfy J.H., Stewart C., Bhambhani V. County community health associations of net voting shift in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. PLoS One. 2017;12(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oude Groeniger J., Gugushvili A., de Koster W., van der Waal J. Population health, not individual health, drives support for populist parties. PNAS Nexus. 2022;1(3) doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen J.G., Bjørklund T. Structural changes and new cleavages: the progress parties in Denmark and Norway. Acta Sociol. 1990;33(3):195–217. doi: 10.1177/000169939003300303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falkenbach M., Greer S.L. Political parties matter: the impact of the populist radical right on health. Eur J Publ Health. 2018;28(suppl_3):15–18. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falkenbach M., Greer S.L., editors. The populist radical right and health: national policies and global trends. 1st ed. 2021 edition. Springer; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rinaldi C., Bekker M.P.M. A scoping review of populist radical right parties’ influence on welfare policy and its implications for population health in Europe. Int J Health Pol Manag. 2021;10(3):141–151. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moise A.D., Scheiring G., Löblová O. In: The populist radical right and health: national policies and global trends. Falkenbach M., Greer S.L., editors. Springer International Publishing; 2021. The populist radical right and health in Hungary; pp. 95–112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zabdyr-Jamróz M., Löblová O., Moise A.D., Kowalska-Bobko I. In: The populist radical right and health: national policies and global trends. Falkenbach M., Greer S.L., editors. Springer International Publishing; 2021. Is the polish ‘law and justice’ (PiS) a typical populist radical right party? A health policy perspective; pp. 113–137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brady H.E., Verba S., Schlozman K.L. Beyond SES: a resource model of political participation. Am Polit Sci Rev. 1995;89(2):271–294. doi: 10.2307/2082425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henderson C., Noblett J., Parke H., et al. Mental health-related stigma in health care and mental health-care settings. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(6):467–482. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Probst C., Manthey J., Martinez A., Rehm J. Alcohol use disorder severity and reported reasons not to seek treatment: a cross-sectional study in European primary care practices. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2015;10(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s13011-015-0028-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puhl R.M., Lessard L.M., Himmelstein M.S., Foster G.D. The roles of experienced and internalized weight stigma in healthcare experiences: perspectives of adults engaged in weight management across six countries. PLoS One. 2021;16(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bränström R., Pachankis J.E. The role of country-level structural stigma on sexual orientation disclosure and discrimination in health care settings among lesbian, gay, and bisexuals across Europe. Eur J Publ Health. 2019;29(Supplement_4) doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckz185.467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pattillo M., Stieglitz S., Angoumis K., Gottlieb N. Racism against racialized migrants in healthcare in Europe: a scoping review. Int J Equity Health. 2023;22(1):201. doi: 10.1186/s12939-023-02014-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samari G., Alcalá H.E., Sharif M.Z. Islamophobia, health, and public health: a systematic literature review. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(6):e1–e9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Boekel L.C., Brouwers E.P.M., van Weeghel J., Garretsen H.F.L. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1):23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paradies Y., Truong M., Priest N. A systematic review of the extent and measurement of healthcare provider racism. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):364–387. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2583-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barnes C., Michener J., Rains E. “It’s like night and day”: how bureaucratic encounters vary across WIC, SNAP, and medicaid. Soc Serv Rev. 2023;97(1):3–42. doi: 10.1086/723365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stuber J., Schlesinger M. Sources of stigma for means-tested government programs. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(4):933–945. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Batbaatar E., Dorjdagva J., Luvsannyam A., Savino M.M., Amenta P. Determinants of patient satisfaction: a systematic review. Perspect Public Health. 2017;137(2):89–101. doi: 10.1177/1757913916634136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kruk M.E., Kapoor N.R., Lewis T.P., et al. Population confidence in the health system in 15 countries: results from the first round of the People’s Voice Survey. Lancet Global Health. 2024;12(1):e100–e111. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00499-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bleich S.N., Özaltin E., Murray C.J. How does satisfaction with the health-care system relate to patient experience? Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(4):271–278. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.050401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKee M., van Schalkwyk M.C.I., Greenley R., Permanand G. World Health Organization, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2024. Trust: the foundation of health systems.https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/trust-the-foundation-of-health-systems-study [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blendon R.J., Benson J.M., Hero J.O. Public trust in physicians — U.S. Medicine in international perspective. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(17):1570–1572. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1407373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hadler M., Eder A., Mayer C. An overview of attitudes and opinions on the role of government. A cross-national comparison covering the period of 1985 to 2016. Int J Sociol. 2019;49(3):171–181. doi: 10.1080/00207659.2019.1605027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Missinne S., Meuleman B., Bracke P. The popular legitimacy of European healthcare systems: a multilevel analysis of 24 countries. J Eur Soc Pol. 2013;23(3):231–247. doi: 10.1177/0958928713480065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.European Parliament . European Parliament; 2017. Eurobarometer: would you like the EU to intervene less than at present or more than at present for the following policy areas?https://www.europarl.europa.eu/infographic/eurobarometer/2017/index_en.html [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hooghe M. Why there is basically only one form of political trust. Br J Polit Int Relat. 2011;13(2):269–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-856X.2010.00447.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rockers P.C., Kruk M.E., Laugesen M.J. Perceptions of the health system and public trust in government in low and middle-income countries: evidence from the world health surveys. J Health Polit Pol Law. 2012;37(3):405–437. doi: 10.1215/03616878-1573076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mattila M., Rapeli L. Just sick of it? Health and political trust in Western Europe. Eur J Polit Res. 2018;57(1):116–134. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fukuyama F. Simon & Schuster; 1996. Trust: the social virtues and the creation of prosperity. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller A.H., Listhaug O. Political parties and confidence in government: a comparison of Norway, Sweden and the United States. Br J Polit Sci. 1990;20(3):357–386. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400005883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rothstein B., Stolle D. The state and social capital: an institutional theory of generalized trust. Comp Polit. 2008;40(4):441–459. doi: 10.5129/001041508X12911362383354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure. Sikt - Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pacheco J., Ojeda C. A healthy democracy? Evidence of unequal representation across health status. Polit Behav. 2020;42(4):1245–1267. doi: 10.1007/s11109-019-09541-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kirbiš A., Mattila M., Rapeli L. Physical health conditions and political participation in Europe: the moderating effects of age. Comp Eur Polit. 2024;22(2):212–242. doi: 10.1057/s41295-023-00347-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Landwehr C., Ojeda C. Democracy and depression: a cross-national study of depressive symptoms and nonparticipation. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S0003055420000830. First View. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huijts T., Perkins J.M., Subramanian S.V. Political regimes, political ideology, and self-rated health in Europe: a multilevel analysis. PLoS One. 2010;5(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bernardi L. Depression and political predispositions: almost blue? Party Polit. 2021;27(6):1132–1143. doi: 10.1177/1354068820930391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ziegenfuss J.K., Davern M., Blewett L.A. Access to health care and voting behavior in the United States. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(3):731–742. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kavanagh N.M., Menon A. The impact of experiences with COVID-19 on the 2020 presidential election and support for health reform. Public Opin Q. 2024;88(4):1269–1282. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galofré-Vilà G., McKee M., Bor J., Meissner C.M., Stuckler D. A lesson from history? Worsening mortality and the rise of the Nazi Party in 1930s Germany. Public Health. 2021;195:18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Galofré-Vilà G., McKee M., Gómez-León M., Stuckler D. The 1918 influenza pandemic and the rise of Italian fascism: a cross-city quantitative and historical text qualitative analysis. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(2):242–247. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McGuire C.M., Rahn W., Gollust S.E. Chronic health conditions and voter turnout: results from the 2012 United States presidential election. World Med Health Pol. 2021;13(2):313–327. doi: 10.1002/wmh3.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gollust S.E., Rahn W.M. The bodies politic: chronic health conditions and voter turnout in the 2008 election. J Health Polit Pol Law. 2015;40(6):1115–1155. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3424450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Inglehart R.F., Norris P. Social Science Research Network; 2016. Trump, Brexit, and the rise of populism: economic have-nots and cultural backlash. HKS Working Paper Series(No. RWP16-026):53. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hochschild A.R. 1 edition. The New Press; 2016. Strangers in their own land: anger and mourning on the American right. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Falkenbach M., Heiss R. In: The populist radical right and health: national policies and global trends. Falkenbach M., Greer S.L., editors. Springer International Publishing; 2021. The Austrian freedom party in government: a threat to public health? pp. 25–45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang D. Draining the Swamp? Populist leadership and corruption. Governance. 2024;37(4):1141–1161. doi: 10.1111/gove.12829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kostadinova T. Do populist governments reduce corruption? East European Politics. 2024;40(1):64–85. doi: 10.1080/21599165.2023.2185226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stoeckel F., Carter C., Lyons B.A., Reifler J. The politics of vaccine hesitancy in Europe. Eur J Publ Health. 2022;32(4):636–642. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckac041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Backhaus I., Hoven H., Kawachi I. Far-right political ideology and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: multilevel analysis of 21 European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2023;335 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Douglas K.M., Uscinski J.E., Sutton R.M., et al. Understanding conspiracy theories. Polit Psychol. 2019;40(S1):3–35. doi: 10.1111/pops.12568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kavanagh N.M., Goel R.R., Venkataramani A.S. County-Level socioeconomic and political predictors of distancing for COVID-19. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(1):13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wallace J., Goldsmith-Pinkham P., Schwartz J.L. Excess death rates for republican and democratic registered voters in Florida and Ohio during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(9):916–923. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barbieri P.N., Bonini B. Political orientation and adherence to social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Econ Polit. 2021;38(2):483–504. doi: 10.1007/s40888-021-00224-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Becher M., Stegmueller D., Brouard S., Kerrouche E. Ideology and compliance with health guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparative perspective. Soc Sci Q. 2021;102(5):2106–2123. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.13035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Szreter S., Woolcock M. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33(4):650–667. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Greer S.L., Falkenbach M., Siciliani L., et al. 2023. Making health for all policies: harnessing the co-benefits of health. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mettler S. University of Chicago Press; 2011. The submerged state: how invisible government policies undermine American democracy. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Watson S. Does welfare conditionality reduce democratic participation? Comp Polit Stud. 2015;48(5):645–686. doi: 10.1177/0010414014556043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Campbell A.L. Policy makes mass politics. Annu Rev Polit Sci. 2012;15(1):333–351. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-012610-135202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.American Public Health Association . American Public Health Association; 2022. Advancing health equity through protecting and promoting access to voting (policy number: 20229) p. 20. [Google Scholar]