Abstract

Citrinin (CIT) is a widely occurring mycotoxin which exhibits a variety of toxic effects. Only a few countries have legal limitations on CIT content in foods, despite the dangers it presents. The aim of this study is to investigate the effects of CIT on DNA methylation in SH-SY5Y and HK-2 cells and to perform docking studies to explore the possible interactions between CIT and DNMT enzymes. In SH-SY5Y cells, global DNA methylation levels increased by 1.90-fold (p < 0.05) and 1.50-fold (p < 0.05) at 50 and 100 μM of CIT, respectively. In HK-2 cells, the increase was 3.17-fold (p < 0.05) following exposure to 50 μM of CIT. In SH-SY5Y cells, DNMT-1, DNMT-3a, DNMT-3b and TET-3 expressions increased significantly, while TET-1 and TET-2 expressions decreased significantly. In HK-2 cells, no significant change in DNMT-1 expression was observed, while DNMT-3a and DNMT-3b expressions increased significantly. Significant decreases in TET-1, TET-2 and TET-3 expressions were observed in HK-2 cells. The docking results suggest that CIT may interact with DNMTs with a high degree of binding, which could potentially lead to the inhibition of these enzymes. The results of this study indicate that DNA methylation may be involved in CIT-induced toxicity. Epigenetic mechanisms and in silico studies hold great potential for advancing chemical risk assessment by uncovering toxicity mechanisms, and the standardization of these techniques is crucial for their integration into policymaking. Accordingly, this study introduces a novel aspect of the potential mechanism of CIT in the risk assessment process.

Keywords: Citrinin, DNA methylation, SH-SY5Y cells, HK-2 cells, Molecular docking

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

CIT exposure results in global DNA hypermethylation in SH-SY5Y and HK-2 cells.

-

•

CIT alters DNMT and TET expression in SH-SY5Y and HK-2 cells, leading to DNA methylation alterations.

-

•

CIT exhibits good binding to DNMTs in silico which may result in their inhibition.

1. Introduction

Citrinin (CIT, (3R, 4S)-4,6-dihydro-8-hydroxy-3,4,5-trimethyl-6-oxo-3H-2-benzopyran-7-carboxylic acid) is a fungal secondary metabolite produced by several Penicillium, Monascus, and Aspergillus species. CIT mainly contaminates fruits, vegetables, cereals and dairy products during harvest, storage and shipping [21], [92]. CIT content in red fermented rice (RFR) products is particularly important. RFR is produced by fermenting rice with Monascus species and has been traditionally used in East Asian countries as a food coloring, flavoring agent, and preservative. Additionally, RFR is utilized in traditional Chinese medicine and as a dietary supplement due to its health-promoting properties. During the rice fermentation process, various metabolites including pigments, lovastatin and CIT are formed [22]. CIT has been found in food across Asia, Europe, Africa, and North America, with varying levels depending on the region and food type [77]. Cereal-based products in Poland [84], Germany, France [19], Burkina Faso and Mozambique [83] contained CIT levels ranging from 1 to 5074 μg/kg. In Turkey, black olives had CIT contamination at 350 μg/kg [34]. RFR products in Belgium [48], China [88], and the USA [30] had CIT levels between 0.10 and 121,097 μg/kg [46]. Understanding the toxicity mechanisms of CIT is crucial for accurately evaluating the health risks posed by its widespread occurrence in food.

The kidneys are the primary organs affected by CIT. Balkan endemic nephropathy, a chronic disease predominantly observed in middle-aged farmers in rural areas of the Balkans, has been linked to co-exposure to CIT and ochratoxin A (OTA) [68], [79]. Although the neurotoxicity of CIT is not fully understood, recent studies have brought attention to its neurotoxic effects, particularly in SH-SY5Y cells and zebrafish models [1], [81]. CIT has been shown to exhibit a variety of biological activities such as ROS (reactive oxygen species) production [85], induction of apoptosis [37], alteration of mitochondrial membrane potential [59], disruption of oocyte maturation and embryonic development [14], [87], suppression of RNA synthesis and interference with cytokine expression [4]. Previous studies have suggested that epigenetic alterations could play a significant role in mycotoxin-induced toxicity [12]. Epigenetic processes may provide insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the harmful effects of CIT on neurons and kidney cells [52]. DNA methylation is one of the most important epigenetic modifications and plays crucial roles in cancer [42], diabetes [11], aging [44], developmental, neurological and psychiatric disorders [63]. Genotoxic and non-genotoxic carcinogens may exert their toxic effects or promote tumor development through epigenetic mechanisms [35]. CIT has been classified as a Group 3 carcinogen by the International Agency for Cancer Research [40]. The results of CIT genotoxicity assessments are inconclusive, with some test systems yielding positive results while others produce negative outcomes [23]. DNA methylation occurs when the fifth carbon of a cytosine located in a CpG dinucleotide is methylated by DNA methyltransferase enzymes (DNMTs), leading to the formation of 5-methylcytosine (5-mC). DNMT3 enzymes facilitate the methylation reaction, while DNMT-1 is responsible for maintaining DNA methylation patterns [41]. S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) serves as the methyl donor for many methylation reactions, including DNA methylation. Following the methyl transfer, SAM is converted to S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH), which acts as an inhibitor of DNMTs [69]. Ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenase enzymes (TETs) play a role in oxidizing the methyl groups, reversing the methylation of cytosines and forming hydroxymethylcytosine [78]. Previous studies suggest that DNA lesions caused by oxidative stress may disrupt interactions between DNA and the epigenetic machinery, leading to DNA methylation alterations and subsequent cell dysfunction [26]. The interaction between DNA and proteins is modified by alterations in methylation, which in turn affects chromatin structure and ultimately influences transcription [43]. Modifications in DNA methylation may lead to the silencing of tumor-suppressor genes, disruptions in cell cycle regulation, and impairments in DNA repair mechanisms [62]. Aberrant methylation patterns in apoptosis-related genes, including p53, Fas, and caspase-8, play a role in both the initiation and execution of apoptosis [29]. Several studies have associated CIT with changes in miRNA (micro-RNA) levels [28] as well as alterations in histone deacetylase and DNMT expression [67], suggesting that CIT may exert its toxic effects by disrupting epigenetic mechanisms. However, studies on the epigenetic effects of CIT remain limited.

Despite the significance of epigenetic mechanisms in toxicity, the use of such mechanisms for risk assessment is an emerging concept. Risk assessment approaches rely on formal guidelines that require extensive research, time and funding to update [18]. Recently, the incorporation of epigenetic mechanisms in toxicity assessment has received considerable attention, highlighting their potential role in understanding chemical-induced adverse effects [57], [94]. The objective of present study was to examine the global DNA methylation modifications induced by CIT in SH-SY5Y and HK-2 cell lines and integration of molecular docking in DNA methylation assessments, as alterations in DNA methylation may be a contributing factor to the reported neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity of CIT. SH-SY5Y cells are widely used neuronal models for toxicity testing and elucidation of mechanisms involved in neurotoxicity. SH-SY5Y cells used in this study are effective for investigating gene expression and epigenetic alterations resulting from neurotoxicant exposure [55]. HK-2 cells exhibit cellular and molecular activity comparable to primary proximal tubule cells. Toxicity data obtained from studies using HK-2 cells show concordance to in vivo data, thus HK-2 cells provide valuable models for nephrotoxicity testing [65]. Due to their genetic similarity, human cell lines provide great physiological relevance and reproducibility, making them superior to in vivo models for addressing interspecies differences [33]. Green toxicology practices are vital for a sustainable future. This study promotes in silico methods for accelerating toxicity testing [32] and highlights human cell models as alternatives to reduce, refine, and replace animal use in toxicity assessments [56]. We also aimed to contribute to the existing literature on the relationship between toxic outcomes and DNA methylation which could contribute to next-generation risk assessment approaches and the incorporation of epigenetics in adverse outcome pathways [10].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

CIT, purity ≥98 %, was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Michigan, USA). The stock solution of CIT (100 mM) was prepared by dissolving it in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, purity ≥99.9 %), which was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Missouri, USA). Culture media and other supplements were obtained from Wisent Bioproducts (Quebec, Canada). Sterile plastic materials were purchased from Nest Biotechnology (Jiangsu, China). MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) dye used in cytotoxicity tests was obtained from Biomatik (Ontario, Canada). DNA and RNA isolation kits were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Massachusetts, USA). cDNA synthesis kit was purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. (California, USA). 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) DNA quantification kit was purchased from Epigentek Group Inc. (New York, USA). Sybr green master mix was purchased from Bioline (London, UK). Primers used for gene expression analysis were purchased from Sentromer DNA Technologies (Istanbul, Turkey).

2.2. Cell cultures and treatments

Human neuroblastoma cells (SH-SY5Y, CRL-2266) and human adult male proximal tubule kidney cells (HK-2, CRL-2190) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). SH-SY5Y cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium/Ham’s nutrient mixture F-12 (DMEM-F12) and HK-2 cells were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 (RPMI-1640). Media were supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum, and penicillin-streptomycin (100 U–100 mg/mL). Incubation was achieved at 37 ºC and 5 % CO2 in a properly humidified atmosphere. Subculturing was done by trypsinization when cells reached 70–80 % confluence. Only cells between 15 and 25 passage numbers were used to decrease the biological behavior variability and to prevent contamination [39].

For DNA methylation and gene expression analysis, 5 × 105 cells were incubated in 6-well plates for 24 h. SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to CIT at 25, 50 and 100 µM concentrations while HK-2 cells were exposed to CIT at 25 and 50 µM concentrations for 24 h. Exposure duration and doses were determined by evaluating previously published studies and results from our MTT tests [1], [9]. The final concentration of DMSO which was used to dissolve CIT was less than 1 % (v/v) in each exposure well. Every concentration group was evaluated in three separate experiments for every analysis and each analysis was repeated twice.

2.3. Cell viability

MTT test was the preferred method for cell viability assessment. For the test, 1 × 104 cells in 100 µL were seeded on 96-well microplates, incubated for 24 h and cells were exposed to CIT (15.625–500 µM) and DMSO (adjusted to 1 % in culture media as solvent control). After 24 h of exposure of CIT, MTT test was utilized, and the intensity of the formed color was measured in a microplate spectrophotometer at 590 nm wavelength (compared to 670 nm reference wavelength) by using a microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek-Epoch, Winooski, USA). Corrected absorbance values were obtained by subtracting mean absorbance values of blanks (wells containing culture media but no cells) from each solvent control (SC) and exposure group absorbance values [2]. Mean optical densities (OD) of corrected solvent control (corrected ODSC) and samples (corrected ODsample) were calculated. % Relative inhibition (% cell death) was calculated according to the formula given below:

% Relative inhibition = 100- (corrected mean ODsample × 100 /corrected mean ODSC)

2.4. Global DNA methylation analysis

Genomic DNA isolation from cell cultures was performed with Purelink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) by using the guidelines provided by the manufacturer. DNA quantity was measured spectrophotometrically by measuring absorbance levels at a wavelength of 260 nm. DNA purity was analyzed spectrophotometrically by calculating A260/A280. Global DNA methylation assessments were done with MethylFlash™ Methylated 5mC DNA Quantification Kit (Colorimetric) (Epigentek Group Inc., New York, USA) by following the manufacturer’s guides. Briefly, 100 ng sample DNA was placed in each well. Capture antibody and detection antibodies were used to observe the presence of methylated DNA. Finally, absorbances were quantified using a microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek-Epoch, Winooski, USA) at 450 nm. Positive control standard solutions were used to generate a standard curve that was used to measure the methylation levels of DNA samples.

2.5. Gene expression analysis

RNA isolation of cells was performed with Purelink Genomic RNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA), according to the procedures provided by the manufacturer. RNA quantity was measured spectrophotometrically by measuring absorbance levels at 260 nm wavelength. RNA purity was analyzed spectrophotometrically by calculating A260/A280. Reverse transcription was done with iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit’ (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., California, USA) by employing 500 ng total RNA. Expression analyses of DNA methyltransferase genes (DNMT-1, DNMT-3a, DNMT-3b) and ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenase genes (TET-1, TET-2, TET-3) were performed with BioLine SensiFast™ Syber® No-Rox kit (London, UK) [47] and LightCycler® 480 Instrument II (Roche Life Science). Primer sequences of DNMT, TET, reference gene and their annealing temperatures are provided in Table 1. Quantitative Ct (cycle threshold) levels of assessed genes and reference gene β-actin were determined with real time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Relative expressions of genes were assessed with 2-ΔΔCT method by comparing the results to the control group.

Table 1.

Primer sequences and annealing temperatures of DNMT, TET and reference genes.

| Gene | Primer Sequence (5’-3’) | Temperature (ºC) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT-1 | F: CCTCCAAAAACCCAGCCAAC R: TCCAGGACCCTGGGGATTTC |

60 | [3] |

| DNMT-3a | F: GGTCACGCAAAACAGAACCC R: CCTTGGTGAAACCCTTTGCG |

59 | [31] |

| DNMT-3b | F: CTCTTCCTCAGCTGTGTGGG R: CTGTCGGCACTGTGGTTTTG |

59 | [31] |

| TET-1 | F: CCCTTGGAAATGCCATAGGAA R: GAGAGCCTGCTGGAACTGTTG |

58 | [5] |

| TET-2 | F: GGCTGTTGGCCAGAGACTTA R: ATACCTGTAGGTGTTTGCCTGTTTA |

54 | [5] |

| TET-3 | F: GCCAACTTCAACATACCCTGGAC R: CACCTGGATGTGGGACTGTGTAA |

58 | [5] |

| β-actin | F: AACTACCTTCAACTCCAT R: TGATCTTGATCTTCATTGTG |

48 | [72] |

2.6. Molecular docking

In toxicology, molecular docking is used to predict the interaction between a toxicant and its potential targets, helping to identify those involved in toxicity [91]. Crystal structures of DNMT enzymes were obtained from RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/, accessed on October 14, 2024), ligands CIT and SAH were obtained from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on October 14, 2024). CIT (PubChem CID: 54680783) and the co-crystallized endogenous ligand SAH (PubChem CID: 439155) were docked to DNMT-1 (PDB ID: 4WXX, [93]), DNMT-3a (PDB ID: 6W8J, [6]) and DNMT-3b (PDB ID: 6U8V, [27]). Resolution of each crystal structure was equal to or less than 3 Å. Hydrogens were added, and the geometries of ligands were optimized using Avogadro 1.2.0. Initial processing of the macromolecules such as removing non-standard residues and the co-crystallized ligand were done via UCSF ChimeraX 1.7.1, further processing which involved addition of hydrogens and charges were done on MGL Tools 1.5.7. Docking studies were performed on MGL Tools 1.5.7 and AutoDock 4.2. Rotatable bonds on ligands were made rotatable while the macromolecules were rigid. Docking grids were limited and centered on the respective co-crystallized ligand binding site. The search method used in this study, Lamarckian genetic algorithm, was reported to present more reproducible and acceptable results compared to other available search methods in AutoDock such as genetic algorithm and simulated annealing [64]. The binding energies of CIT and the endogenous inhibitor were compared. Conformations with the lowest free binding energy and RMSD (root-mean square deviation) values within < 2.5 Å limit were reported as they represent the highest binding with acceptable accuracy [36], [60], [70]. The docking protocol was optimized according to the RMSD values obtained from re-docking the co-crystallized ligand. 2D and 3D visuals of the selected conformations were generated by Schrödinger- Maestro 13.9 and ChimeraX 1.7.1, respectively.

2.7. Statistical evaluation

Data were provided as “mean value ± standard deviation.” Statistical evaluation of data was done with “SPSS 21.0 for Windows” package program. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality due to the sample size being less than 50. Levene test was used to assess homogeneity of variance. Significance was tested with “one-way analysis of variance” (ANOVA-Post Hoc Dunnet test). p < 0.001 and p < 0.05 values were accepted as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of CIT on cell viability in SH-SY5Y and HK-2 Cells

SH-SY5Y and HK-2 cells were exposed to CIT at 15.625–500 µM concentrations for 24 h and cell viability was analyzed by MTT assay. IC50 values were calculated as 103.47 and 109.16 for SH-SY5Y and HK-2 cells, respectively. In 62.5 µM group, cell viability was >70 % in HK-2 cells while it was > 85 % in SH-SY5Y cells. In 250 µM group, viability of SH-SY5Y cells decreased to approximately 15 % while approximately 25 % of HK-2 cells were still viable.

3.2. Effects of CIT on Global DNA methylation in SH-SY5Y and HK-2 cells

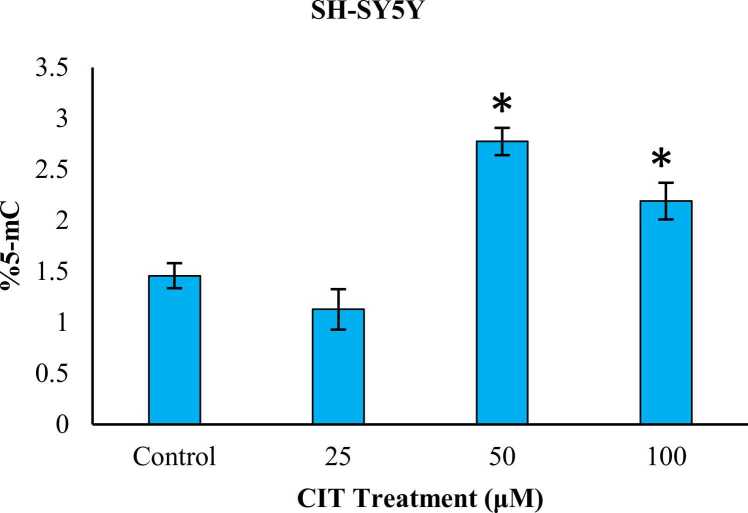

SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to CIT at 25, 50 and 100 μM for 24 hours while HK-2 cells were exposed to CIT at 25, 50 μM concentrations for 24 hours. 5-mC% levels of SH-SY5Y and HK-2 cells were illustrated in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, respectively. 5-mC% levels of SH-SY5Y cells were compared to the control group and an insignificant 22.66 % (p = 0.354) decrease was observed in 25 μM exposure group while a significant 1.90-fold (p < 0.05) and 1.50-fold (p < 0.05) increases were observed in 50 and 100 μM exposure groups, respectively. 5-mC% levels of CIT exposed HK-2 cells were compared to the control group; an insignificant increase of 1.25-fold (p = 0.459) was observed in 25 μM group while a significant 3.17-fold (p < 0.05) increase was observed in 50 μM group. Significant global DNA hypermethylation was observed in both cell lines at their 50 μM exposure groups. However, the change in 50 μM HK-2 group was considerably higher than 100 μM SH-SY5Y group.

Fig. 1.

Effects of CIT (0–100 μM) on 5-mC% levels in SH-SY5Y cells after 24 h exposure. 5-mC content was determined with an ELISA kit. Results from 25, 50 and 100 μM exposure groups were compared to the control group. All values are provided as mean ± standard deviation. * significantly different from control group p < 0.05 (ANOVA-Post Hoc Dunnet test).

Fig. 2.

Effects of CIT (0–50 μM) on 5-mC% levels in HK-2 cells after 24 h exposure. 5-mC content was determined with an ELISA kit. Results from 25 and 50 μM exposure groups were compared to the control group. All values are provided as mean ± standard deviation. * significantly different from control group p < 0.05 (ANOVA-Post Hoc Dunnet test).

3.3. Effects of CIT on DNMT gene expression levels in SH-SY5Y and HK-2 cells

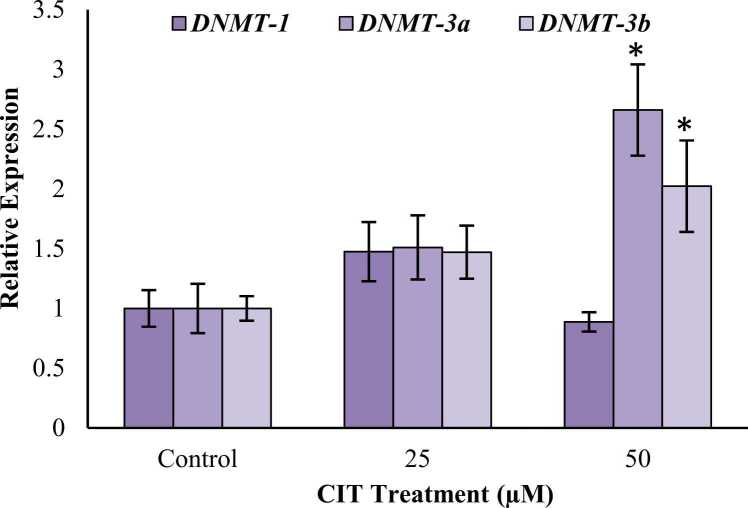

In SH-SY5Y cells, DNMT-1 expression increased significantly by 4.27-fold (p < 0.001) in 100 μM group while statistically insignificant 1.22-fold (p = 0.866) and 1.49-fold (p = 0.440) increases were observed in 25 and 50 μM, respectively. DNMT-3a expressions decreased insignificantly by 21.88 % (p = 0.517) and 4.49 % (p = 0.988) in 25 and 50 μM groups, respectively while the expression increased significantly by 2.73-fold (p < 0.001) in 100 μM group. DNMT-3b expression in 25 μM group decreased insignificantly by 28.46 % (p = 0.838). An insignificant increase of 1.54-fold (p = 0.550) was observed in the 50 μM group. A significant 3.33-fold (p < 0.05) increase was observed in the 100 μM group (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effects of CIT (0–100 μM) on relative expression levels of DNMT genes in SH-SY5Y cells after 24 h exposure. Gene expression was analyzed using RT-PCR. All values are provided as mean ± standard deviation. * significantly different from control group p < 0.05; ** significantly different from control group p < 0.001 (ANOVA-Post Hoc Dunnet test).

In HK-2 cells, expression of DNMT-1 increased insignificantly by 1.47-fold (p = 0.092) in 25 μM group while the levels decreased insignificantly by 11.27 % (p = 0.794) in 50 μM group. Expression of DNMT-3a gene increased insignificantly by 1.51-fold (p = 0.086) in 25 μM group while a significant 2.66-fold (p < 0.05) increase was observed in 50 μM group. Expression of DNMT-3b insignificantly increased by 1.47-fold (p = 0.063) in 25 μM group while a significant increase of 2.02-fold (p < 0.05) was observed in 50 μM group (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effects of CIT (0–50 μM) on relative expression levels of DNMT Genes in HK-2 cells after 24 h exposure. Gene expression was analyzed using RT-PCR. All values are provided as mean ± standard deviation. * significantly different from control group p < 0.05 (ANOVA-Post Hoc Dunnet test).

3.4. Effects of CIT on TET gene expression levels in SH-SY5Y and HK-2 cells

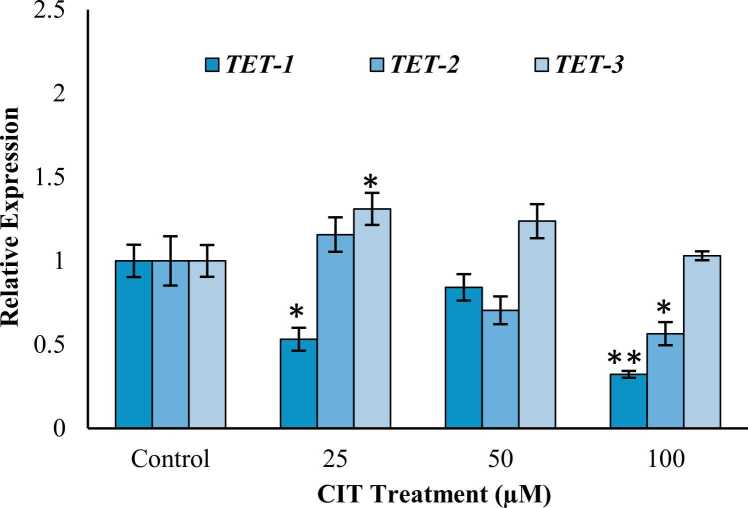

In SH-SY5Y cells expression levels of TET-1 gene decreased significantly by 46.78 % (p < 0.05) and 67.75 % (p < 0.001) in 25 and 100 μM groups, respectively while an insignificant 15.79 % (p = 0.111) decrease was observed in 50 μM group. TET-2 expression increased insignificantly by 1.15-fold (p = 0.265) in 25 μM group and decreased insignificantly by 29.49 % (p = 0.032) in 50 μM group. A significant decrease of 43.45 % (p < 0.05) was observed in 100 μM group. TET-3 levels increased significantly by 1.31-fold (p < 0.05) in 25 μM group, while insignificant increases of 1.23-fold (p = 0.074) and 1.03- fold (p = 0.965) were observed in 50 and 100 μM groups, respectively (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effects of CIT (0–100 μM) on relative expression levels of TET genes in SH-SY5Y cells after 24 h exposure. Gene expression was analyzed using RT-PCR. All values are provided as mean ± standard deviation. * significantly different from control group p < 0.05; ** significantly different from control group p < 0.001 (ANOVA-Post Hoc Dunnet test).

In HK-2 cells, expression levels of TET-1 gene decreased insignificantly by 6.95 % (p = 0.577) in 25 μM group while a significant 88.88 % (p < 0.05) decrease was observed in 50 μM group. TET-2 expression decreased insignificantly by 1.95 % (p = 0.924) in 25 μM group. In 50 μM group a significant decrease of 78.40 % (p < 0.001) was observed. TET-3 expression increased insignificantly by 1.01-fold (p = 0.984) in 25 μM group while a significant decrease of 80.13 % (p < 0.05) was observed in 50 μM group (Fig. 6). HK-2 cells exhibited a greater overall decrease in TET expression compared to SH-SY5Y cells which could contribute to the higher methylation levels observed in HK-2 cells.

Fig. 6.

Effects of CIT (0–50 μM) on relative expression levels of TET genes in HK-2 cells after 24 h exposure. Gene expression was analyzed using RT-PCR. All values are provided as mean ± standard deviation. * significantly different from control group p < 0.05; ** significantly different from control group p < 0.001 (ANOVA-Post Hoc Dunnet test).

3.5. Molecular docking results

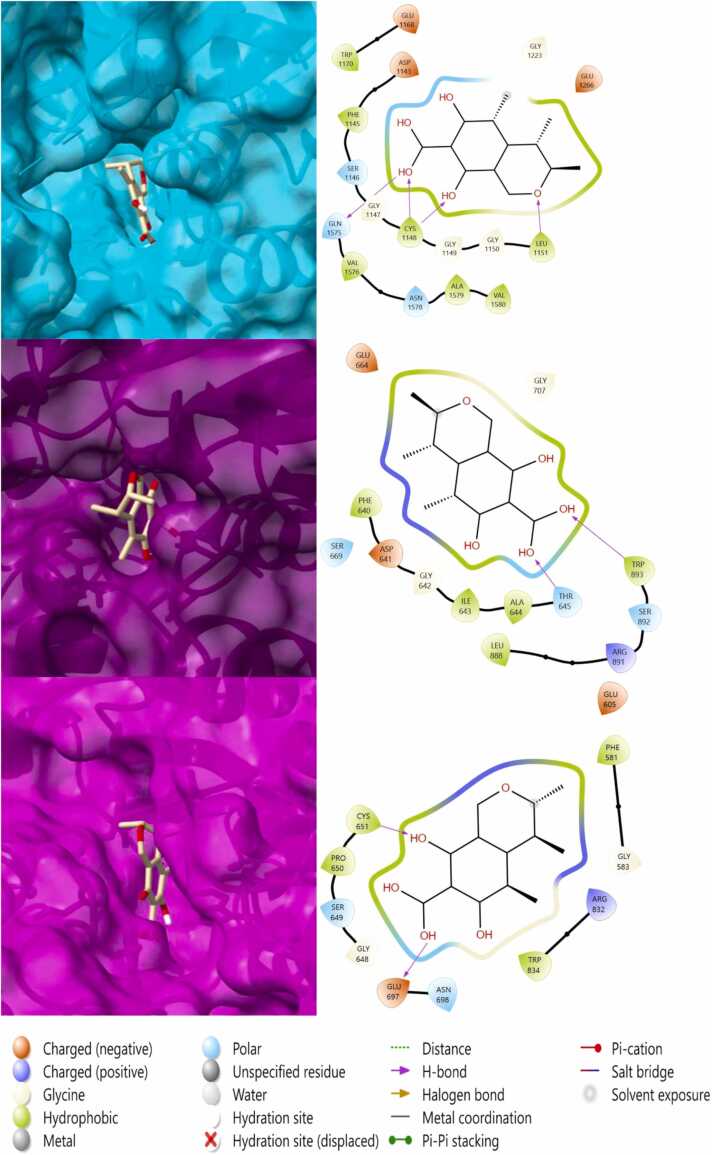

Estimated free binding energies under the cut-off RMSD are provided in Table 2 and 2D/3D illustrations of CIT in its binding sites are provided in Fig. 7. The binding energies of CIT and the endogenous inhibitor SAH were compared. Free binding energy results of less than −6.0 kcal/mol generally indicates that the molecule is active [76]. CIT exhibited higher binding than SAH in DNMT-1 and DNMT-3a while slightly higher but still comparable binding energy was observed in DNMT-3b. CIT formed hydrogen bonds with CYS-1148, LEU-1151 and GLN-1575 residues of DNMT-1; THR-645 and TRP-893 residues of DNMT-3a; CYS-651 and GLU-697 residues of DNMT-3b.

Table 2.

Docking results of CIT and SAH.

| Enzyme | Ligand | Estimated Free Energy of Binding (kcal/mol) | RMSD (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT-1 | CIT SAH |

−9.10 −8.25 |

0.878 2.374 |

| DNMT-3a | CIT SAH |

−7.34 −6.89 |

0.631 2.285 |

| DNMT-3b | CIT SAH |

−7.71 −8.31 |

0.821 2.172 |

Fig. 7.

2D and 3D visuals of CIT docking results. Binding mode and amino acid interactions of CIT within the active sites of DNMT enzymes are provided. DNMT-1, DNMT-3a and DNMT-3b are represented by cyan, purple and magenta proteins, respectively.

4. Discussion

Mycotoxins are fungal secondary metabolites which threaten the health of humans and animals. Exposure to mycotoxins may occur via different routes and consumption of food contaminated by mycotoxins cause “mycotoxicosis” which may cause serious health problems [71]. Several mycotoxin prevention methods have been established over the years, but complete removal is not possible [45]. Since total prevention is not achievable it is crucial to understand the possible toxic effects of mycotoxins and safety limits should be established through regulations. Despite its known harmful effects, maximum permitted CIT levels are only set in a limited number of countries [22]. In the European Union, CIT levels are regulated only in RFR dietary supplements, with a maximum limit of 2000 μg/kg. In Japan and China, CIT limits apply exclusively to RFR, set at 200 μg/kg and 50 μg/kg, respectively [77]. Considering that CIT may contaminate foods beyond just RFR products, it is important to establish regulations for other food categories as well. The use of epigenetics in toxicity assessment is an evolving field, as these mechanisms have been linked to numerous adverse health outcomes. Understanding epigenetic alterations caused by toxicants is promising for novel safety assessment methods as they can be used to develop adverse outcome pathways and other alternative risk assessment approaches [51].

The no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL) for CIT-induced toxicity was calculated as 20 µg/kg b.w. per day after a 90-day toxicity study in rats. After extrapolation to humans, the NOAEL for nephrotoxicity in humans was calculated as 0.2 µg/kg b.w. per day [21]. The lowest level at which epigenetic alterations were first observed in our study was 50 μM. 50 μM CIT is approximately equal to 0.0125 mg/mL (12.5 ppm= 12.5 mg/kg) which is substantially higher than the previously established NOAEL level. However, the previously reported presence of CIT at levels up to 121 mg/kg in red yeast rice products raises concerns about its potential to influence DNA methylation alterations, particularly when combined with other epigenetic toxicants.

In male Sprague Dawley rats, CIT caused renal damage, but no renal tumors were observed. It was shown that oral CIT exposure after N- (3, 5-dichlorophenyl) succinimide) treatment resulted in tumors and CIT potentiated the tumorigenic effect of N-nitrosodimethylamine [75]. Šegvić Klarić et al. [73] have reported that OTA exposure decreased HSP 70 (heat shock protein) and HSP 27 expression while CIT increased their expression in PK-15 (adult pig kidney) cells. The combination of OTA and CIT increased it further. HSPs are expressed in response to stressful conditions. CIT was also shown to cause oxidative stress as observed by thiol and glutathione modifications [73]. 7.5 and 15 μM CIT increased apoptosis induced by OTA, 2.5 and 5 μM CIT lowered apoptosis while 1 μM CIT did not affect OTA induced apoptosis in IHKE cells (immortalized human proximal tubule cells) [49]. 20 mg/kg b.w. daily for 2 days CIT exposure in rats resulted in a decrease of glutathione concentration while no change was observed on malondialdehyde levels in rat plasma, liver, and kidney. Increased tail intensity was observed using Comet assay in rat kidney cells [24]. CIT was shown to alter the locomotor activity and neuronal development of zebrafish larvae. Expression profiles of genes related to differentiation, growth and signaling were altered in SH-SY5Y cells [81]. In SH-SY5Y cells exposed to CIT, G2/M arrest, apoptosis, and changes in mitochondrial membrane potential were reported [59].

In the present study, IC50 values of CIT have been calculated as 103.47 μM for SH-SY5Y and as 109.16 μM for HK-2 cells in our MTT assays. In previous studies, IC50 in V79 cells were measured as 70 and 62 μM after treatment for 24 and 48 hours, respectively [25]. IC50 was calculated as 116.5 µM after being treated for 24 hours in mouse Sertoli cells [9]. IC50 values were identified as 71.93 μM, 77.92 μM, 147.85 μM and 65.93 μM for MCF-7 (human breast adenocarcinoma), LNCaP (androgen-sensitive human prostate adenocarcinoma), LU-1 (human lung carcinoma) and KB (human oral epidermoid carcinoma) cell lines after 72 hours of incubation, respectively [89].

Epigenetic markers have been recognized as indicators and predictors of cancer, neurological and cardiovascular diseases. These discoveries have opened the possibility of utilizing epigenetic markers to assess the toxic effects of environmental contaminants [16]. Our results indicate that in SH-SY5Y cells, DNA methylation levels increased significantly in 50 µM and 100 µM groups. DNMT-1, DNMT-3a and DNMT-3b expressions were increased significantly in 100 µM group while no significant changes were observed in 25 and 50 µM groups. Previous research has reported that DNMT gene expression and DNA methylation levels are increased in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and DNMT-3b may induce apoptosis in motor neuron cells [15]. Global DNA hypermethylation was reported in epileptic rats [90]. Increased global DNA methylation levels in human middle frontal gyrus and middle temporal gyrus have been linked to Alzheimer's disease [17]. In the present study, significant decreases were observed in TET-1 gene expression in 25 μM and 100 μM groups. TET-2 expression levels decreased significantly only in 100 μM group while TET-3 levels increased significantly in 25 μM group. Previously, impairments in brain functions and behavior were observed in TET knockout mice which indicates the importance of TET genes and hydroxymethylcytosine levels in the brain [54].

In our HK-2 cell lines methylation levels increased significantly in 50 µM group. Arai et al. (2006) reported that they observed regional DNA hypermethylation in precancerous renal tissues which highlights the possibility that DNA methylation may be an important biomarker for the prognosis of kidney cancer [7]. In our results, changes in DNMT-1 expressions were insignificant in all exposure groups. DNMT-3a and DNMT-3b expression increased significantly in 50 μM group. In previous studies, significant increases were observed in DNMT-1 and DNMT-3a in oxidative stress induced malignant HK-2 cells which indicate that DNA hypermethylation may be responsible for kidney tumorigenesis [58]. DNMT-3b was observed to be responsible for the methylation of miR-181a-5p which resulted in renal interstitial fibrosis [53]. TET-1, TET-2 and TET-3 expression levels were significantly decreased in 50 μM group. Previously, decreases in TET-1 and TET-2 expressions were observed in response to renal ischemia reperfusion injury in mice [38].

In our study, significant alterations in DNMT and TET expression levels occurred at ~ IC50 value for SH-SY5Y cells while these changes occurred at almost half of IC50 value in HK-2 cells. It appears that kidney cells are more likely to undergo DNA methylation alterations than neuroblastoma cells when exposed to CIT. This indicates that epigenetic mechanisms, specifically DNA methylation status, could be the differential mechanism that contributes to the reported target organ nephrotoxicity of CIT.

Effects of CIT on various epigenetic mechanisms have been studied previously. Gong et al. [28] have shown that miRNA-122–5p, miRNA-1246, miRNA-1290, miRNA-215–5p and miRNA-7–5p levels were increased and hsa-miRNA-1268a, hsa-miR-1–3p and hsa-miR-34c-5p levels were decreased in HEK-293 cells exposed to CIT. Levels of TNFR which causes apoptosis through TNF activation were increased. BCL2-associated athanogene 3 gene was suppressed while BCL2-antagonist/killer 1 and BCL2-like 12 expressions were promoted in samples exposed to CIT. hsa-miR-1–3p was slightly inhibited by CIT which resulted in an increase of its apoptosis related target programmed cell death 10 (PDCD10). Expression of proteins related to cell cycle were also affected which suggested that CIT may cause G2/M arrest. Increase of hsa-miR-122–5p levels decreased the activity of cyclin G1 which interfered with the cell cycle process [28]. miRNAs have the potential to regulate the expression of DNMT and TET enzymes. Conversely, the methylation patterns of miRNA promoters control miRNA expression, which can subsequently alter DNA methylation [8]. Wu et al. [86] have reported that CIT alters the phenotype of the heart, shrinks the heart chambers, and causes pericardial edema in developing zebra fish embryo. The study also showed that CIT increases the levels of aldh1a2, cspg2 and decreased tbx2a levels possibly through the stimulation of retinoic acid pathway by decreasing miRNA-138 expression which resulted in faults in heart and decreased blood flow [86]. In bovine macrophage cells CIT and OTA have not changed gene expression by themselves, but their combination has decreased the expression of genes encoding DNMT-3a, DNMT-3b, histone demethylase (JMJD-3), histone deacetylase (HDAC-3) enzymes. Inhibition of DNMT-3s may result in p53 mediated PCD, the suppression of HDAC-3 may inhibit cell proliferation while the inhibition of JMJD-3 can promote cell proliferation. In the mentioned study, there was no data regarding the status of DNMT-1 [67]. To our knowledge, there are no studies regarding the effects of CIT on TET gene expression.

A previous study reported that CIT exerts inhibitory effects on DNMT activity [80]. Our docking results agree with this finding as CIT showed greater binding to DNMT-1 and DNMT-3a than the endogenous inhibitor while slightly higher but comparable binding energies were observed in DNMT-3b results. In our gene expression studies it was observed that CIT increases the DNMT expressions at different concentrations in both SH-SY5Y and HK-2 cell lines. The upregulation of DNMT gene expression may represent a compensatory response to the DNMT inhibitory effects of CIT. [74]. Increases observed in DNA methylation levels may have occurred as a result of CIT-induced oxidative stress. Fe (II) is a co-factor of TET enzymes. Under oxidative stress, the reduction of Fe (III) back to Fe (II) is impaired, this perturbation in iron cycle leads to TET enzyme inhibition and an increase in 5-mC levels [66]. Campos et al. [13] observed that elevated ROS levels lead to increased expression of DNMT-1 and DNMT-3a. However, they have also observed decreased 5-mC levels which was not seen in the present study [13]. Our findings suggest that DNMTs may not be the primary factor contributing to CIT-induced hypermethylation, as the high binding affinity of CIT to DNMTs could influence enzymatic activity. The observed CIT-induced DNA hypermethylation in the present study may have occurred due to decreased TET gene expression especially in the target organ of CIT which is the kidney. These findings contribute to the existing literature by suggesting that toxicity may result from global DNA methylation alterations, as demonstrated through molecular docking and cell culture studies. Given the high cost of chemicals and animal tests, conventional toxicity testing is financially demanding. Incorporating in silico and in vitro techniques as preliminary studies decrease the cost substantially [95]. Sub-acute, sub-chronic or long-term exposure cannot be accurately assessed with the techniques used in the present study which could be better evaluated through animal models. The high-cost of CIT is a limiting factor in such studies as animals have to be administered a large amount of mycotoxin.

Various epidemiological studies investigating the relationship between environmental exposure and global DNA methylation alterations have been published [20], [82]. DNA methylation alterations were proposed to signify exposure to air pollution, heavy metals, endocrine disrupting chemicals and non-genotoxic carcinogens [61]. Epigenetic alterations are reversible yet heritable changes that regulate gene expression. DNA methylation alterations in children were used to predict prenatal smoking with high accuracy [50]. This suggests that DNA methylation-based assays may serve as long-term biomarkers of exposure. Despite being reversible, epigenetic alterations remain for a considerable amount of time which implies that disruptions in the epigenetic machinery may lead to long-term adverse health outcomes. Therefore, it is critical to consider epigenetic mechanisms when addressing toxicity of environmental toxicants. In our study, the relationship between CIT exposure and global DNA methylation is demonstrated. Future epidemiological studies examining the link between CIT exposure, global DNA methylation, and neurotoxicity/nephrotoxicity could play a significant role in risk assessment and policy development.

5. Conclusions

In this study, exposure to CIT led to elevated global DNA methylation levels in SH-SY5Y and HK-2 cells, due to altered DNMT and TET gene expression. Molecular docking analyses suggest that CIT may interact with DNMT enzymes, potentially affecting their activity. Given this, TET enzymes appear to play a greater role in CIT-induced DNA hypermethylation. These findings indicate that epigenetic mechanisms contribute to CIT-induced toxicity. Additionally, the study suggests that DNA methylation alterations and molecular docking assessments may serve as valuable tools for risk assessment. Further research is needed to fully understand the toxicity mechanisms of CIT, particularly in the context of epigenetics.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Cakir Metin Caner: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Ozden Sibel: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye 2209-A Research Project Support Program (Project No: 1919B012307104).

Data availability

Data is provided by the authors.

References

- 1.Abudayyak M., Karaman E.F., Ozden S. Mechanisms underlying citrinin-induced toxicity via oxidative stress and apoptosis-mediated by mitochondrial-dependent pathway in SH-SY5Y cells. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2023;46(5):944–954. doi: 10.1080/01480545.2022.2113095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abudayyak M., Öztaş E., Özhan G. Assessment of perfluorooctanoic acid toxicity in pancreatic cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2021;72 doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2021.105077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmadnejad M., Amirizadeh N., Mehrasa R., Karkhah A., Nikougoftar M., Oodi A. Elevated expression of DNMT1 is associated with increased expansion and proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells co-cultured with human MSCs. Blood Res. 2017;52(1):25. doi: 10.5045/br.2017.52.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed Adam M.A., Tabana Y.M., Musa K.B., Sandai D.A. Effects of different mycotoxins on humans, cell genome and their involvement in cancer (Review) Oncol. Rep. 2017;37(3):1321–1336. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alrehaili A.A., Gharib A.F., Alghamdi S.A., Alhazmi A., Al-Shehri S.S., Hagag H.M., Alsaeedi F.A., Alhuthali H.M., Raafat N., Etewa R.L., Elsawy W.H. Evaluation of TET family gene expression and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine as potential epigenetic markers in non-small cell lung cancer. Vivo. 2023;37(1):445–453. doi: 10.21873/invivo.13098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anteneh H., Fang J., Song J. Structural basis for impairment of DNA methylation by the DNMT3A R882H mutation. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):2294. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16213-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arai E., Kanai Y., Ushijima S., Fujimoto H., Mukai K., Hirohashi S. Regional DNA hypermethylation and DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) 1 protein overexpression in both renal tumors and corresponding nontumorous renal tissues. International journal of cancer. 2006;119(2):288–296. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aure M.R., Fleischer T., Bjørklund S., Ankill J., Castro-Mondragon J.A., Børresen-Dale A.-L., Tost J., Sahlberg K.K., Mathelier A. Crosstalk between microRNA expression and DNA methylation drives the hormone-dependent phenotype of breast cancer. Genome Med. 2021;13(1):72. doi: 10.1186/s13073-021-00880-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aydin Y., Orta Yilmaz B., Yildizbayrak N., Korkut A., Arabul Kursun M., Irez T., Erkan M. Evaluation of citrinin-induced toxic effects on mouse Sertoli cells. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2021;44(6):559–565. doi: 10.1080/01480545.2019.1614021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahadori T., Bell D., Ceccatelli S., Corvi R., Hogstrand C., Munn S., Nilsson E., Spurgeon D., Vom Brocke J., Wray-Cahen D. EFSA scientific colloquium 22–epigenetics and risk assessment: where do we stand? EFSA Support. Publ. 2016;13(12) doi: 10.2903/sp.efsa.2016.EN-1129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bansal A., Pinney S.E. DNA methylation and its role in the pathogenesis of diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes. 2017;18(3):167–177. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bayoglu S.O., Karaman E., Ozden S. Effects of fumonisin B1 on gene-specific DNA methylation related to cancer pathways of p53 signalling and PI3K/Akt signalling in human kidney cells. World Mycotoxin J. 2024;17(3-4):177–189. doi: 10.1163/18750796-bja10008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campos A.C., Molognoni F., Melo F.H., Galdieri L.C., Carneiro C.R., D'Almeida V., Correa M., Jasiulionis M.G. Oxidative stress modulates DNA methylation during melanocyte anchorage blockade associated with malignant transformation. Neoplasia. 2007;9(12):1111–1121. doi: 10.1593/neo.07712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan W.-H. Effects of citrinin on maturation of mouse oocytes, fertilization, and fetal development in vitro and in vivo. Toxicol. Lett. 2008;180:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chestnut B.A., Chang Q., Price A., Lesuisse C., Wong M., Martin L.J. Epigenetic regulation of motor neuron cell death through DNA methylation. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31(46):16619–16636. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1639-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung F.F.-L., Herceg Z. The promises and challenges of toxico-epigenomics: environmental chemicals and their impacts on the epigenome. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020;128(1) doi: 10.1289/EHP6104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coppieters N., Dieriks B.V., Lill C., Faull R.L., Curtis M.A., Dragunow M. Global changes in DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation in Alzheimer's disease human brain. Neurobiol. Aging. 2014;35(6):1334–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cote I.L., McCullough S.D., Hines R.N., Vandenberg J.J. Application of epigenetic data in human health risk assessment. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2017;6:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cotox.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Čulig B., Bevardi M., Bošnir J., Serdar S., Lasić D., Racz A., Galić A., Kuharić Ž. Presence of citrinin in grains and its possible health effects. Afr. J. Tradit., Complement. Altern. Med. 2017;14(3):22–30. doi: 10.21010/ajtcam.v14i3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Prins S., Koppen G., Jacobs G., Dons E., Van de Mieroop E., Nelen V., Fierens F., Panis L.I., De Boever P., Cox B. Influence of ambient air pollution on global DNA methylation in healthy adults: a seasonal follow-up. Environ. Int. 2013;59:418–424. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2025.119131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.EFSA (European Food and Safety Authority) Scientific opinion on the risks for public and animal health related to the presence of citrinin in food and feed. EFSA J. 2012;10(3):2605. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farawahida A.H., Palmer J., Flint S. Monascus spp. and citrinin: identification, selection of Monascus spp. isolates, occurrence, detection and reduction of citrinin during the fermentation of red fermented rice. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022;379 doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2022.109829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flajs D., Peraica M. Toxicological properties of citrinin. Arch. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol. 2010;60(4):457–464. doi: 10.2478/10004-1254-60-2009-1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flajs, D., Želježić, D., Mladinić, M., & Peraica, M. (2010). Effects of citrinin treatment on oxidative stress in rat kidney. XII International Congress of Toxicology.

- 25.Föllmann W., Behm C., Degen G.H. Toxicity of the mycotoxin citrinin and its metabolite dihydrocitrinone and of mixtures of citrinin and ochratoxin A in vitro. Arch. Toxicol. 2014;88:1097–1107. doi: 10.1007/s00204-014-1216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franco R., Schoneveld O., Georgakilas A.G., Panayiotidis M.I. Oxidative stress, DNA methylation and carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2008;266(1):6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao L., Emperle M., Guo Y., Grimm S.A., Ren W., Adam S., Uryu H., Zhang Z.-M., Chen D., Yin J. Comprehensive structure-function characterization of DNMT3B and DNMT3A reveals distinctive de novo DNA methylation mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):3355. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17109-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gong L., Zhu H., Li T., Ming G., Duan X., Wang J., Jiang Y. Molecular signatures of cytotoxic effects in human embryonic kidney 293 cells treated with single and mixture of ochratoxin A and citrinin. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019;123:374–384. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gopisetty G., Ramachandran K., Singal R. DNA methylation and apoptosis. Mol. Immunol. 2006;43(11):1729–1740. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordon R.Y., Cooperman T., Obermeyer W., Becker D.J. Marked variability of monacolin levels in commercial red yeast rice products: buyer beware. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010;170(19):1722–1727. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gu H., Gao J., Guo W., Zhou Y., Kong Q. The expression of DNA methyltransferases3A is specifically downregulated in chorionic villi of early embryo growth arrest cases. Mol. Med Rep. 2017;16(1):591–596. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamid N., Junaid M., Manzoor R., Sultan M., Chuan O.M., Wang J. An integrated assessment of ecological and human health risks of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances through toxicity prediction approaches. Sci. Total Environ. 2023;905 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawksworth G.M. Advantages and disadvantages of using human cells for pharmacological and toxicological studies. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 1994;13(8):568–573. doi: 10.1177/096032719401300811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heperkan D., Meric B.E., Sismanoglu G., Dalkiliç G., Güler F.K. Mycobiota, mycotoxigenic fungi, and citrinin production in black olives. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2006;571:203–210. doi: 10.1007/0-387-28391-9_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herceg Z., Lambert M.-P., van Veldhoven K., Demetriou C., Vineis P., Smith M.T., Straif K., Wild C.P. Towards incorporating epigenetic mechanisms into carcinogen identification and evaluation. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(9):1955–1967. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holmes S.G., Desai U.R. Assessing genetic algorithm-based docking protocols for prediction of heparin oligosaccharide binding geometries onto proteins. Biomolecules. 2023;13(11):1633. doi: 10.3390/biom13111633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang Y.T., Lai C.Y., Lou S.L., Yeh J.M., Chan W.H. Activation of JNK and PAK2 is essential for citrinin-induced apoptosis in a human osteoblast cell line. Environ. Toxicol.: Int. J. 2009;24(4):343–356. doi: 10.1002/tox.20434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang N., Tan L., Xue Z., Cang J., Wang H. Reduction of DNA hydroxymethylation in the mouse kidney insulted by ischemia reperfusion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;422(4):697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes P., Marshall D., Reid Y., Parkes H., Gelber C. The costs of using unauthenticated, over-passaged cell lines: how much more data do we need? Biotechniques. 2007;43(5):575–586. doi: 10.2144/000112598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Some naturally occurring and synthetic food components, furocumarins and ultraviolet radiation. IARC monographs on the evaluation of the carcinogenic risk of chemicals to humans; 1986, Vol. Lyon: IARC; 40, 67-82.. [PubMed]

- 41.Jeltsch A., Jurkowska R.Z. New concepts in DNA methylation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014;39(7):310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jin B., Li Y., Robertson K.D. DNA methylation: superior or subordinate in the epigenetic hierarchy? Genes Cancer. 2011;2(6):607–617. doi: 10.1177/1947601910393957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones P.A., Takai D. The role of DNA methylation in mammalian epigenetics. Science. 2001;293(5532):1068–1070. doi: 10.1126/science.1063852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jung M., Pfeifer G.P. Aging and DNA methylation. BMC Biol. 2015;13(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s12915-015-0118-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kabak B., Dobson A.D.W., Var I. Strategies to prevent mycotoxin contamination of food and animal feed: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2006;46(8):593–619. doi: 10.1080/10408390500436185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kamle M., Mahato D.K., Gupta A., Pandhi S., Sharma N., Sharma B., Mishra S., Arora S., Selvakumar R., Saurabh V. Citrinin mycotoxin contamination in food and feed: impact on agriculture, human health, and detection and management strategies. Toxins. 2022;14(2):85. doi: 10.3390/toxins14020085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karaman E.F., Doğan E., Alga D., Özden S. The effects of prochloraz on the levels of nuclear receptor genes expressions and global DNA methylation in human prostate carcinoma cells. Istanb. J. Pharm. 2021;51(2):191–197. doi: 10.26650/IstanbulJPharm.2021.850791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kiebooms J., Huybrechts B., Thiry C., Tangni E., Callebaut A. A quantitative UHPLC-MS/MS method for citrinin and ochratoxin A detection in food, feed and red yeast rice food supplements. World Mycotoxin J. 2016;9(3):343–352. doi: 10.3920/WMJ2015.1971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knecht A., Schwerdt G., Gekle M., Humpf H.-U. Combinatory effects of citrinin and ochratoxin A in immortalized human proximal tubule cells. Mycotoxin Res. 2005;21:176–181. doi: 10.1007/BF02959258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ladd-Acosta C., Fallin M.D. DNA methylation signatures as biomarkers of prior environmental exposures. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2019;6:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s40471-019-0178-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LaRocca J., Johnson K.J., LeBaron M.J., Rasoulpour R.J. The interface of epigenetics and toxicology in product safety assessment. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2017;6:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cotox.2017.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li L., He Z., Shi Y., Sun H., Yuan B., Cai J., Chen J., Long M. Role of epigenetics in mycotoxin toxicity: A review. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023;100 doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2023.104154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu H., Deng Y., Luo G., Yang Y., Xie B., Diao H., Chen M., Chen L., Xie P., Kwan H.Y. DNA methylation of miR-181a-5p mediated by DNMT3b drives renal interstitial fibrosis developed from acute kidney injury. Epigenomics. 2024;16(13):945–960. doi: 10.1080/17501911.2024.2370229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu J.-W., Zhang Z.-Q., Zhu Z.-C., Li K., Xu Q., Zhang J., Cheng X.-W., Li H., Sun Y., Wang J.-J., Hu L.-L., Xiong Z.-Q., Zhu Y. Loss of TET activity in the postnatal mouse brain perturbs synaptic gene expression and impairs cognitive function. Neurosci. Bull. 2024 doi: 10.1007/s12264-024-01302-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lopez-Suarez L., Al Awabdh S., Coumoul X., Chauvet C. The SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line, a relevant in vitro cell model for investigating neurotoxicology in human: focus on organic pollutants. Neurotoxicology. 2022;92:131–155. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2022.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maertens A., Luechtefeld T., Knight J., Hartung T. Alternative methods go green!: green toxicology as a sustainable approach for assessing chemical safety and designing safer chemicals. ALTEX - Altern. Anim. Exp. 2024;41(1):3–19. doi: 10.14573/altex.2312291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maffini M.V., Vandenberg L.N. Emerging topics on chemical safety assessment. Front. Toxicol. 2025;6:1542469. doi: 10.3389/ftox.2024.1542469. (https://doi.org/doi:) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mahalingaiah P.K.S., Ponnusamy L., Singh K.P. Oxidative stress-induced epigenetic changes associated with malignant transformation of human kidney epithelial cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8(7):11127. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marti-Quijal F., Barba F., Ruiz M.-J. P15-02: Exploring the impact of citrinin mycotoxin on SH-SY5Y cells: Apoptosis, cell cycle, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial function. Toxicol. Lett. 2023;384:S183–S184. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4274(23)00690-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matossian M., Vangelderen C., Papagerakis P., Zheng L., Wolf G., Papagerakis S. In silico modeling of the molecular interactions of antacid medication with the endothelium: novel therapeutic implications in head and neck carcinomas. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2014;27(4):573–583. doi: 10.1177/039463201402700413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meehan R.R., Thomson J.P., Lentini A., Nestor C.E., Pennings S. DNA methylation as a genomic marker of exposure to chemical and environmental agents. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2018;45:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meng H., Cao Y., Qin J., Song X., Zhang Q., Shi Y., Cao L. DNA methylation, its mediators and genome integrity. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2015;11(5):604. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.11218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moore L.D., Le T., Fan G. DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):23–38. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morris G.M., Goodsell D.S., Halliday R.S., Huey R., Hart W.E., Belew R.K., Olson A.J. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem. 1998;19(14):1639–1662. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19981115)19:14< 1639::AID-JCC10> 3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mossoba M.E., Sprando R.L. In vitro to in vivo concordance of toxicity using the human proximal tubule cell line HK-2. Int. J. Toxicol. 2020;39(5):452–464. doi: 10.1177/1091581820942534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Niu Y., DesMarais T.L., Tong Z., Yao Y., Costa M. Oxidative stress alters global histone modification and DNA methylation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;82:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oh S.-Y., Balch C.G., Cliff R.L., Sharma B.S., Boermans H.J., Swamy H., Quinton V.M., Karrow N.A. Exposure to Penicillium mycotoxins alters gene expression of enzymes involved in the epigenetic regulation of bovine macrophages (BoMacs. Mycotoxin Res. 2013;29:235–243. doi: 10.1007/s12550-013-0174-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Petkova-Bocharova T., Castegnaro M., Michelon J., Maru V. Ochratoxin A and other mycotoxins in cereals from an area of Balkan endemic nephropathy and urinary tract tumours in Bulgaria. IARC Sci. Publ. 1991;(115):83–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pfalzer A.C., Choi S.-W., Tammen S.A., Park L.K., Bottiglieri T., Parnell L.D., Lamon-Fava S. S-adenosylmethionine mediates inhibition of inflammatory response and changes in DNA methylation in human macrophages. Physiol. Genom. 2014;46(17):617–623. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00056.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ramírez D., Caballero J. Is it reliable to take the molecular docking top scoring position as the best solution without considering available structural data? Molecules. 2018;23(5):1038. doi: 10.3390/molecules23051038. 〈https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/23/5/1038〉 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reddy K.R.N., Salleh B., Saad B., Abbas H., Abel C., Shier W.T. An overview of mycotoxin contamination in foods and its implications for human health. Toxin Rev. 2010;29:3–26. doi: 10.3109/15569541003598553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rosa S.C., Gonçalves J., Judas F., Mobasheri A., Lopes C., Mendes A.F. Impaired glucose transporter-1 degradation and increased glucose transport and oxidative stress in response to high glucose in chondrocytes from osteoarthritic versus normal human cartilage. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009;11(3):R80. doi: 10.1186/ar2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Šegvić Klarić M., Medić N., Hulina A., Žanić Grubišić T., Rumora L. Disturbed Hsp70 and Hsp27 expression and thiol redox status in porcine kidney PK15 cells provoked by individual and combined ochratoxin A and citrinin treatments. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014;71:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shilpi A., Parbin S., Sengupta D., Kar S., Deb M., Rath S.K., Pradhan N., Rakshit M., Patra S.K. Mechanisms of DNA methyltransferase–inhibitor interactions: procyanidin B2 shows new promise for therapeutic intervention of cancer. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2015;233:122–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2015.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shinohara Y., Arai M., Hirao K., Sugihara S., Nakanishi K., Tsunoda H., Ito N. Combination effect of citrinin and other chemicals on rat kidney tumorigenesis. GANN Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 1976;67(2):147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shityakov S., Förster C. In silico predictive model to determine vector-mediated transport properties for the blood–brain barrier choline transporter. Adv. Appl. Bioinforma. Chem. 2014;7:23–36. doi: 10.2147/AABC.S63749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Silva L.J., Pereira A.M., Pena A., Lino C.M. Citrinin in foods and supplements: a review of occurrence and analytical methodologies. Foods. 2020;10(1):14. doi: 10.3390/foods10010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Smith Z.D., Meissner A. DNA methylation: roles in mammalian development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14(3):204–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stoev S.D. Balkan endemic nephropathy – still continuing enigma, risk assessment and underestimated hazard of joint mycotoxin exposure of animals or humans. Chem. -Biol. Interact. 2017;261:63–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2016.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sugiyama K.-i, Furusawa H., Honma M. Detection of epigenetic effects of citrinin using a yeast-based bioassay. Mycotoxin Res. 2019;35:363–368. doi: 10.1007/s12550-019-00361-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tsai J.-F., Wu T.-S., Yu F.-Y., Liu B.-H. Neurotoxicity of mycotoxin citrinin: novel evidence in developing zebrafish and underlying mechanisms in human neuron cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023;171 doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2022.113543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang I.-J., Karmaus W.J., Chen S.-L., Holloway J.W., Ewart S. Effects of phthalate exposure on asthma may be mediated through alterations in DNA methylation. Clin. epigenetics. 2015;7:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13148-015-0060-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Warth B., Parich A., Atehnkeng J., Bandyopadhyay R., Schuhmacher R., Sulyok M., Krska R. Quantitation of mycotoxins in food and feed from Burkina Faso and Mozambique using a modern LC-MS/MS multitoxin method. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60(36):9352–9363. doi: 10.1021/jf302003n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wawrzyniak J., Waśkiewicz A. Ochratoxin A and citrinin production by Penicillium verrucosum on cereal solid substrates. Food Addit. Contam.: Part A. 2014;31(1):139–148. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2013.861933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wu J., Yang C., Yang M., Liang Z., Wu Y., Kong X., Fan H., Wang S., Ning C., Xiao W. The role of ER stress and ATP/AMPK in oxidative stress meditated hepatotoxicity induced by citrinin. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022;237 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wu T.-S., Yang J.-J., Yu F.-Y., Liu B.-H. Cardiotoxicity of mycotoxin citrinin and involvement of microRNA-138 in zebrafish embryos. Toxicol. Sci. 2013;136(2):402–412. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu Y., Zhang N., Li Y.-H., Zhao L., Yang M., Jin Y., Xu Y.-N., Guo H. Citrinin exposure affects oocyte maturation and embryo development by inducing oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(21):34525. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Xue-Mei L., Xing-Hai S., Lan X., Zhen-Wen D., Shu-Ren G. A validated RP-HPLC method for the determination of citrinin in Xuezhikang capsule and other monascus-fermented products. J. Chem. 2012;9(1):260–266. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yao G., Sebisubi F.M., Voo L.Y.C., Ho C.C., Tan G.T., Chang L.C. Citrinin derivatives from the soil filamentous fungus Penicillium sp. H9318. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2011;22:1125–1129. doi: 10.1590/S0103-50532011000600018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Younesian S., Yousefi A.-M., Momeny M., Ghaffari S.H., Bashash D. The DNA methylation in neurological diseases. Cells. 2022;11(21):3439. doi: 10.3390/cells11213439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zeng Z., Hu J., Xiao G., Liu Y., Jia D., Wu G., Xie C., Li S., Bi X. Integrating network toxicology and molecular docking to explore the toxicity of the environmental pollutant butyl hydroxyanisole: An example of induction of chronic urticaria. Heliyon. 2024;10(15) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang H., Ahima J., Yang Q., Zhao L., Zhang X., Zheng X. A review on citrinin: its occurrence, risk implications, analytical techniques, biosynthesis, physiochemical properties and control. Food Res. Int. 2021;141 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.110075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang Z.-M., Liu S., Lin K., Luo Y., Perry J.J., Wang Y., Song J. Crystal structure of human DNA methyltransferase 1. J. Mol. Biol. 2015;427(15):2520–2531. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang Y., Song J.-Y., Sun Z.-G. Exploring the impact of environmental factors on male reproductive health through epigenetics. Reprod. Toxicol. 2025;132 doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2025.108832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zink D., Chuah J.K.C., Ying J.Y. Assessing toxicity with human cell-based in vitro methods. Trends Mol. Med. 2020;26(6):570–582. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2020.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Further reading

- 1.Cakir M.C., Ozden S. Effects of Citrinin on DNA Methylation Demonstrated in Vitro and in Silico. Mendeley Data. 2024;V1. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided by the authors.