Abstract

Background

– Identifying children with a high risk of developing future obesity could enable timely targeted prevention strategies. The study’s objective was to develop prediction models that could detect if young children at very early age, from birth to age six, have an increased risk of being obese in early adolescence.

Methods

– We analyzed a subset of data (N = 4,309) from the Generation R study, a population-based prospective cohort study of pregnant women and their children from fetal life to young adulthood in the Netherlands. Parental, household, and birth/child characteristics were considered as predictors. We developed separate models for children at age zero (three months), two, four, and six years that predict obesity at age 10 to 14 years. Per age we fitted an optimal prediction model (full model) and a more practical model with less predictors (restricted model). For the development of the prediction models we used regularized regression models with a least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) penalty to avoid overfitting.

Results

– Parental body mass index (BMI), parental education level, latest child BMI measurements, ethnicity of the child, breakfast consumption, cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) of the child were included as predictors in all models when considered as candidate predictor. The models for all age groups performed well (lowest area under the curve (AUC) 0.872 for the age 0 restricted model), with the highest performance for the 6-year model (AUC 0.954 and 0.949, full and restricted model). Sensitivity and specificity of models varied between ages with ranges 0.80–0.90 (full model); 0.79–0.89 (restricted model) and 0.80–0.88 (full model); 0.79–0.87 (restricted model).

Conclusions

– These obesity prediction models seem promising and could be used as valuable tools for early detection of children at increased risk of being obese at adolescence, even at an early age.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12887-025-05661-1.

Keywords: Prediction model, Obesity, Early age, Generation R study

Background

Obesity is a worldwide prevalent risk for adverse physical and mental health outcomes. It is associated with noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes mellitus type 2, cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, and certain types of cancer [1–3]. Globally, 6% (girls) to 8% (boys) of children aged 5 to 19 years and 13% of adults were obese in 2016, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. The prevalence of obesity in the Netherlands was 3.5% in children aged 4 to 17 years and 14.3% in adults in 2021 [4, 5]. Obesity and overweight are a leading risk factor of 4.8% of deaths worldwide [2].

Obesity not only negatively affects the health of adults. Also, children with obesity are at increased risk of having additional cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance) and orthopedic and psychosocial problems [1, 3, 6–9]. In addition, children with obesity have a higher chance of becoming adults with obesity [1, 7, 10, 11]. The likelihood of childhood obesity persisting into adulthood depends on factors such as age, degree of obesity, the childhood trajectory of BMI, and obesity of parents [7, 11]. Treatment of obesity is generally not very effective in achieving sustainable weight changes [12, 13]. As such, monitoring and prevention at an early age is essential to prevent obesity and may provide a window of opportunity to promote sustainable lifestyle changes for children and their families. To provide timely interventions for those at-risk of becoming obese, it is essential to detect children at-risk for obesity at an early age.

A prediction model detecting children at-risk that could be easily implemented in the field is paramount to its effect. The nationally organized Dutch Preventive Child Health Care is offered free of charge, has a reach of up to 95%, and monitors and promotes optimal child growth and development for all children from 0 to 19 years with several check-ups at very early age and by working with guidelines, for example a guideline to signal and prevent childhood overweight [14, 15]. The Dutch Preventive Child Health Care is an ideal setting for targeted primary prevention of obesity in young children in the Netherlands.

Two previous studies by Steur et al. [16] and Welten et al. [17] have developed prediction models in a Dutch birth cohort for the outcome overweight at the age of eight years. Steur et al. developed a model to be applied at birth and Welten et al. developed a single model that could be applied at all ages between 3 months and 6 years using data available soon after birth combined with longitudinal growth data. To our knowledge, no prediction models for obesity at adolescence for use in Dutch Preventive Child Health Care have been developed that both utilize the repeatedly measured growth data and are optimized for age at risk assessment by having separate models for specific ages.

To facilitate early detection and timely treatment and prevention of obesity by Dutch Preventive Child Health Care, the main objective of this study is to develop and internally validate models that predict obesity at adolescence (10–14 years) from an early age using data from The Generation R study [18], a population-based prospective cohort study in the Rotterdam area in the Netherlands. This data allows us to develop multiple age specific models to be used for children at age 3 months (infant/3m/0y model), two years (2y), four years (4y), and six years (6y), resembling the different periods of consultation in Dutch Preventive Child Health Care [15]. By creating separate models for the different ages, instead of a single model, we are allowing for age-specific predictors to be included. Using the more extensive data from the Generation R study also allows us to include predictors that are currently not monitored by Dutch Preventive Child Health Care and that might be valuable to include. Some of the predictors, such as cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) at age 6 years, require invasive blood sampling and should prove to be of great added value before they are considered to be added to a preventive monitoring setting. To further facilitate practical use in Dutch Preventive Child Health Care, a full model and a more restricted model, with less variables due to stricter selection criteria, are fitted per age.

Methods

The study’s objective is to develop and internally validate prediction models that can detect if young children at very early age, from birth to age six, have an increased risk of being obese in early adolescence.

Study design and population: the generation R study

To develop the obesity prediction models, data from the Generation R Study [18] was used. The Generation R Study is a multi-ethnic population-based prospective cohort study from fetal life until adulthood and is conducted in Rotterdam, the second largest city in the Netherlands. Pregnant women with an expected delivery date between April 2002 and January 2006 living in Rotterdam were eligible for participation in the study. Enrolment was aimed at early pregnancy but was possible until the child’s birth. In total, 9,153 mothers were enrolled in the study with a total of 9,778 pregnancies and who gave birth to 9.749 live-born children. An overall response rate of pregnant women was not obtained, as it was difficult to precisely estimate the number of eligible pregnant women in the study area due to a lack of satisfactory registry of pregnancies [19]. Since the children form a prenatally recruited birth-cohort, the overall response of the study has been established at birth and is 61% [19]. At enrolment, the mothers included in the Generation R cohort had a mean age similar to all pregnant women in the study area [20]; compared to the population in the study area the distribution of ethnicity differed only moderately [21]; a selection towards a higher socio-economic status is suggested by both household income and highest followed educational level in mothers and fathers in the study cohort, a pattern similar as in other large scale cohort studies [21]. However, selective missing values of ethnicity and socio-economic status in the questionnaires might also have been the cause of differences between the population and cohort characteristics. [21] Extensive assessments were performed on mothers, fathers, and their children. The Medical Ethical Committee of Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam, has approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants [18]. See the design papers of the Generation R Study [18–25] for more detailed information on the cohort, including enrolment, response and representativeness. See the Declarations section of this paper for more information on ethics approval, consent and data availability in the Generation R study.

For this study we excluded participating children who did not have a recorded BMI score between age 10 and 14.

Outcome of obesity in adolescence

The outcome for all prediction models is obesity at age 10 to 14 (median 13.48 years), based on international sex- and age-based cut-off values of BMI by Cole et al. 2000 [26].

Participants were invited to the research center at the ages of 10 and 13 years, where the research staff obtained weight and height measurements [18]. Height and weight were measured without shoes and heavy clothing. We calculated the BMI in kg/m2 and converted it into BMI z-scores using the 1997 Dutch reference growth charts (sex- and age-dependent BMI values from the Fourth Dutch Growth Study) [27]. Within the age range of 10 to 14 years our participants usually had one, but sometimes two measurements available. For participants with two measurements available, the BMI corresponding to the highest BMI z-score measured within this age range was selected as the indicator of obesity status in adolescence. Then, for each participant the BMI measurement at adolescence was categorized into obesity yes/no using the sex and age specific cut-offs by Cole et al. [26].

Candidate predictors from birth to age 6

The obesity prediction models were created by carefully selecting a range of potential predictors based on literature, available data, and author consensus [17, 28–33]. These predictors can be grouped into two categories. Baseline predictors available at birth and time dependent predictors available later in life. Baseline predictors were: mother’s pre-pregnancy BMI; father/partner’s BMI; mother’s educational level; father/partner’s educational level; maternal smoking during pregnancy; mother’s age at birth; parity; maternal gestational weight gain; delivery type; gestational age; child’s birthweight z-score; child’s sex; child’s ethnicity. Time-dependent predictors were: mother’s current BMI (age 6y); family/household income (age 0/2/3/6y); family/household size (age 6m/2/3/6y); mother’s marital/living status (age 0/2/3/6y); smoking exposure in parental house (age 3m/2/3/6y); child’s BMI z-score at (age 3m/6m/9m/1.15y/2y/4y/6y); breastfeeding of child (age 3m/1y); age of fruit/vegetable introduction (age 6m); sleep (age 3m/2y); screen time (age 2/4/6y); playing outside (age 3/4/6y); playing sports (age 6y); snack/soda consumption during screen time (age 3y); snack consumption (age 4/6y); sweet drinks consumption (age 4/6y); breakfast consumption (age 4/6y); cholesterol level (age 6y); HDL level (age 6y); LDL level (age 6y); triglycerides level (age 6y).

For the non-baseline variables we only included the variable of the corresponding age in the model, except for child’s BMI z-score, breastfeeding and fruit/vegetable introduction. Breastfeeding (never/ever) assessed at age 1 and age fruit/vegetable introduction (< 4; 4–6;6 > months) assessed at age 6 months were included in the 2, 4 and 6y model. For BMI z-score we included in the models all the measurements up till age of assessment.

Please see Table 1 for the units and categories each candidate predictor consists of. For detailed information on the predictors, please see supplemental Text S1 and Tables S1-5.

Table 1.

Pooled descriptive values of the candidate predictors and outcome for the population for analysis N = 4,309 from the 20 imputed datasets

| Baseline variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s prepregnancy BMI | kg/m2 | 23.54 (4.18) | |||

| Father/partner’s BMI | kg/m2 | 25.30 (3.44) | |||

| Mother’s educational level | Primary | 275.65 (6.4%) | |||

| Secondary | 1820.35 (42.25%) | ||||

| Higher education | 2213.00 (51.36%) | ||||

| Father/partner’s educational level | Primary | 300.30 (6.97%) | |||

| Secondary | 1768.85 (41.05%) | ||||

| Higher education | 2239.85 (51.98%) | ||||

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy | Never | 3334.25 (77.38%) | |||

| Until pregnancy was known | 354.50 (8.23%) | ||||

| Continued during pregnancy | 620.25 (14.39%) | ||||

| Mother’s age (birth) | years | 31.53 (4.92) | |||

| Parity (birth) | Number of times given birth | 0.59 (0.82) | |||

| Maternal gestational weight gain (birth) | kg/wk | 0.35 (0.16) | |||

| Delivery type (birth) | Vaginal | 3742.15 (86.84%) | |||

| Cesarean | 566.85 (13.16%) | ||||

| Gestational age (birth) | weeks | 39.77 (1.90) | |||

| Birthweight z-score (birth) | z-score | -0.04 (1.35) | |||

| Sex of child (birth) | Male | 2151.00 (49.92%) | |||

| Female | 2158.00 (50.08%) | ||||

| Ethnicity of child (birth) | Dutch | 2703.65 (62.74%) | |||

| Cape Verdean | 120.25 (2.79%) | ||||

| Dutch Antilles | 131.20 (3.04%) | ||||

| Morroccan | 211.30 (4.9%) | ||||

| Turkish | 204.50 (4.75%) | ||||

| Surnamese-Creole | 110.30 (2.56%) | ||||

| Surinamese-Hindustani | 122.65 (2.85%) | ||||

| Other | 705.15 (16.36%) | ||||

| Outcome variables at adolesence | |||||

| BMI | kg/m2 | 19.56 (3.42) | |||

| Obesity | Non-obese | 4167.00 (96.70%) | |||

| Obese | 142.00 (3.30%) | ||||

| Time-dependent variables | Age 0 | Age 2 | Age 4 | Age 6 | |

| Mother’s current BMI (age 6) | kg/m2 | - | - | - | 25.48 (4.92) |

| Household income (age 0/2/3/6) | Moderate/High | 3566.40 (82.77%) | 3449.65 (80.06%) | 3478.20 (80.72%) | 3650.75 (84.72%) |

| Low | 742.60 (17.23%) | 859.35 (19.94%) | 830.80 (19.28%) | 658.25 (15.28%) | |

| Household size (age 6m/2/3/6) | Number of household members | 3.64 (1.00) | 3.68 (0.93) | 3.91 (1.03) | 4.08 (0.96) |

| Mother’s marital/living status (age 0/2/3/6) | Married/registered partner/living together | 3812.30 (88.47%) | 3807.20 (88.35%) | 3749.75 (87.02%) | 3696.60 (85.79%) |

| No partner/not living together | 496.70 (11.53%) | 501.80 (11.65%) | 559.25 (12.98%) | 612.40 (14.21%) | |

| Smoking exposure in parental house (age 3m/2/3/6) | No smoking | 3768.50 (87.46%) | 3465.85 (80.43%) | 3602.35 (83.60%) | 3834.45 (88.99%) |

| Smoking | 540.50 (12.54%) | 843.15 (19.57%) | 706.65 (16.40%) | 474.55 (11.01%) | |

| Child’s BMI z-score | age 0.25 | - | 0.35 (0.89) | 0.35 (0.89) | 0.36 (0.85) |

| age 0.5 | - | 0.10 (0.87) | 0.11 (0.86) | 0.11 (0.83) | |

| age 0.75 | - | 0.18 (0.86) | 0.18 (0.86) | 0.18 (0.82) | |

| age 1.15 | - | 0.17 (0.89) | 0.17 (0.88) | 0.18 (0.86) | |

| age 2 | - | 0.24 (0.91) | 0.23 (0.91) | 0.23 (0.88) | |

| age 4 | - | - | 0.08 (0.82) | 0.08 (0.81) | |

| age 6 | - | - | - | 0.22 (0.78) | |

| Breastfeeding of child (age 3m/1/1/1) | No, never | 1372.50 (31.85%) | 336.95 (7.82%) | 336.95 (7.82%) | 336.95 (7.82%) |

| Yes, ever | 2936.50 (68.15%) | 3972.05 (92.18%) | 3972.05 (92.18%) | 3972.05 (92.18%) | |

| Age fruit/vegetable introduction (age 6m) | < 4 months | - | 268.25 (6.23%) | 268.25 (6.23%) | 268.25 (6.23%) |

| 4–6 months | - | 3914.40 (90.84%) | 3914.40 (90.84%) | 3914.40 (90.84%) | |

| > 6 months | - | 126.35 (2.93%) | 126.35 (2.93%) | 126.35 (2.93%) | |

| Sleep day (3m) | 0–4 h | 831.55 (19.30%) | - | - | - |

| 4–6 h | 1193.85 (27.71%) | - | - | - | |

| 6–8 h | 1385.65 (32.16%) | - | - | - | |

| > 8 h | 897.95 (20.84%) | - | - | - | |

| Sleep night (3m) | < 6 h | 824.35 (19.13%) | - | - | - |

| ≥ 6 h | 3484.65 (80.87%) | - | - | - | |

| Sleep (age 2) | h/day | - | 10.95 (1.02) | - | - |

| Screen time (age 2/4/6) | h/day | - | 0.70 (0.48) | 1.02 (0.74) | 1.67 (1.23) |

| Playing outside (age 3/4/6) | h/day | - | 1.61 (0.85) | 1.00 (0.78) | 1.58 (1.12) |

| Playing sports (age 6) | No | - | - | - | 2324.75 (53.95%) |

| Yes | - | - | - | 1984.25 (46.05%) | |

| Snack/soda during screen time (age 3) | No, almost never | - | 1501.40 (34.84%) | - | - |

| Sometimes | - | 2537.45 (58.89%) | - | - | |

| Often or almost always | - | 270.15 (6.27%) | - | - | |

| Snack consumption (age 4/6) | Number of snacks per day (age 6) | - | - | - | 1.43 (0.82) |

| Never (age 4) | - | - | 435.95 (10.12%) | - | |

| Once per day (age 4) | - | - | 2462.85 (57.16%) | - | |

| 2 or more times per day (age 4) | - | - | 1410.20 (32.73%) | - | |

| Sweet drinks consumption (age 4/6) | Number of sweet drinks per day (age 6) | - | - | - | 2.34 (1.26) |

| Less than 1 glass per day (age 4) | - | - | 596.85 (13.85%) | - | |

| 1 glass per day (age 4) | - | - | 738.60 (17.14%) | - | |

| 2 glasses per day (age 4) | - | - | 1331.70 (30.91%) | - | |

| 3 glasses per day (age 4) | - | - | 1057.40 (24.54%) | - | |

| 4 glasses per day (age 4) | - | - | 393.00 (9.12%) | - | |

| More than 4 glasses per day (age 4) | - | - | 191.45 (4.44%) | - | |

| Breakfast consumption (age 4/6) | Number of days per week (age 6) | - | - | - | 6.87 (0.64) |

| Every day of the week (age 4) | - | - | 3916.80 (90.90%) | - | |

| 6 days per week or less (age 4) | - | - | 392.20 (9.10%) | - | |

| Cholesterol (age 6) | mmol/L | - | - | - | 4.21 (0.76) |

| HDL (age 6) | mmol/L | - | - | - | 1.34 (0.32) |

| LDL (age 6) | mmol/L | - | - | - | 2.37 (0.65) |

| Triglycerides (age 6) | mmol/L | - | - | - | 1.04 (0.49) |

Descriptive values of the 20 imputed datasets are pooled using Rubin’s rule for point estimation [38]. The descriptives are provided as mean (SD) for continuous values and frequency (%) for categorical values. The descriptive values of the time-dependent variables are given for each age accordingly. For more information on the variables please see Text S1 in the supplemental files

Statistical analysis

Data pre-processing

The data were pre-processed and analysed using the statistical software R version 4.0.3 [34]. Pre-processing included constructing a broken stick model to estimate BMI growth at fixed intervals (see supplemental Text S1, paragraph 2.2 for more detailed information) [35], imputing missing data, adding synthetic cases using random over-sampling examples (ROSE) to address the low prevalence of obesity in our sample, and finally normalizing all non-standardized continuous predictors and dummy coding categorical predictors.

Missing data were imputed using multiple imputation through chained equations with the mice package in R [36]. Continuous outcomes were imputed using predictive mean matching, dichotomous variables with logistic regression, and categorical variables using random forests. As our data contained missing values, between 16.7% and 20.4% total missingness for each model, we used the imputation model to create 20 imputed data sets. This is in line with recommendations for moderate amounts of missing values [37, 38]. The model was iterated 20 times to achieve final imputation values. Resulting predicted probabilities are pooled using Rubin’s rules [38]. Reported performance metrics are based on pooled results.

In our data, only 3.3% of cases (N = 142) had obesity in early adolescence. We used the ROSE oversampling technique to address this class imbalance [39]. Additional synthetic children with obesity were created based on the observed data and added to the original data to train the model on data with perfect class balance. The model is then applied to the original data without any synthetic cases to test the model’s predictive performance.

Statistical model

To predict obesity, we used a regularized regression model with a least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) penalty to avoid overfitting [40]. This shrinks coefficients and omits them from the model when they become too small. The omitting of variables from the model does not necessarily mean they are unrelated to obesity, only that they do not improve the model’s predictive power. There are a variety of ways to perform a LASSO model on multiple imputed data. We opted for a so-called stacked approach, as it is computationally the most efficient method, and has been shown to give good results in simulations [41]. All 20 imputations are combined into a single data set. Weights are used so that all imputed observations for a case sum up to one.

We used 5-fold cross-validation to determine the appropriate penalty value for our data. The data was partitioned into five parts, randomly and stratified by the outcome variable. We ensured that each subject’s imputations were assigned to the same fold. In each round, the model was trained on 80% of the data and applied to the remaining 20%. This process was repeated ten times, testing 100 penalty values. The penalty value that resulted in the highest average out-of-sample receiver operating characteristic (ROC) AUC was selected and used to train a final model on the complete data.

To create a more suitable model for use in primary care, we fit a second series of more restricted models with fewer variables. We used the one standard error rule to select a more conservative penalty, resulting in a simpler model [42]. Results from the restricted models are shown alongside those from the full models.

Model performance

Models are assessed using ROC AUC. This metric represents the model’s ability to distinguish obese and non-obese cases [43]. ROC AUC tends to be too optimistic when the outcome is highly imbalanced. For this reason, we also report the positive predictive value, which tells us what proportion of positive predictions truly had obesity in adolescence. Sensitivity and specificity of the models are also calculated. Sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive values are dependent on a cut-off value of the predicted risk to categorize someone at high or low risk of becoming obese. The reported performance measures in this study were calculated using a risk threshold set at 0.5.

Each model was internally validated using 10-fold cross-validation. We chose this model validation method over data splitting methods, as it does not require a sacrifice in sample size [44]. The data is randomly divided into 10 parts. In each round, the data pre-processing steps, including the broken stick model and imputation model, and the prediction model, are developed on 90% of the data. The remaining 10% of the data is then used to assess out-of-sample performance. The average and the range of the resulting performance metrics are reported alongside the within-sample results. An average cross-validated metric that is similar to the within-sample metrics indicates that the model performs equally well on new data as it did on the training data. A narrow range indicates these results are stable and the model is not strongly affected by the selected sample.

Sensitivity analyses

Additional sensitivity analyses were performed to look into differences between participants from the Generation R Study that were included and excluded from our population for analysis. Also, we provided the performance estimates of the models for additional cut-off values for the predicted risk at 0.25 and 0.75. To assess if the prediction models are able to identify children becoming obese at adolescence, but whom are not obese yet at time of risk prediction, we assessed the sensitivity of the model in this group of children.

Results

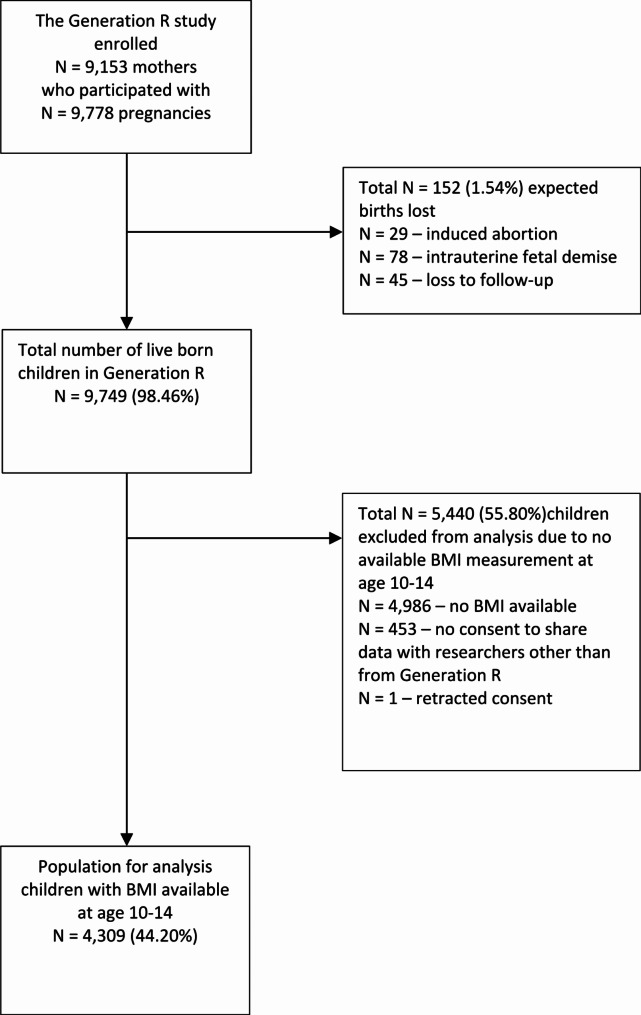

The Generation R study gathered information on a total of 9,749 live-born children. Children who did not have a recorded BMI score when they were between 10 and 14 years old were excluded. This left 4,309 cases for the final analysis (Fig. 1), and out of these, 142 (3.3%) were classified as obese during early adolescence (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the population of analysis. (The overall response of the Generation R Study established at birth was 61%)

The broken stick model was utilized to estimate BMI z-scores at specific points in time for all cases. The estimated BMI z-scores closely matched the observed data (R2 = 0.936). Multiple imputations were checked for accuracy through visual inspections of the data, including trace plots and density plots. The results showed that convergence was achieved within 20 iterations, and no problematic imputed values were found.

Table 1 shows the descriptive information of the population for analysis.

Table 2 presents the full and restricted models for age 0, 2, 4, and 6 years to predict obesity during adolescence. Predictors that were included in all the models that they were considered a candidate predictor for were the baseline variables mother’s prepregnancy BMI, father’s BMI at enrolment, mother’s and father’s educational level, ethnicity of the child; and the time-dependent variables mother’s current BMI, the two most recent child BMI z-score measurements, child’s breakfast consumption, child’s cholesterol level and child’s LDL levels. Other predictors that were included in more than half of all full models were: mother’s age, sex of the child, household income, household size, smoking exposure in parental house, age fruit/vegetable introduction and playing outside. Please see supplemental Text S2, for a detailed explanation on how to calculate the predicted risk for an individual using our prediction model including an example.

Table 2.

Prediction models for obesity at age 10–14 in children aged 0, 2, 4 and 6. Pooled odds ratios (exponential values of the beta (b) coefficients*) from the logistic regression models with LASSO penalty in the population for analysis N = 4,309 from the 20 imputed datasets

| Age 0 | Age 2 | Age 4 | Age 6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline variables | Unit/categories | Full exp(b)* | Restricted** exp(b)* | Full exp(b)* | Restricted** exp(b)* | Full exp(b)* | Restricted** exp(b)* | Full exp(b)* | Restricted** exp(b) |

| Intercept | 0.640 | 0.565 | 0.442 | 0.631 | 0.437 | 0.570 | 0.201 | 0.272 | |

| Mother’s prepregnancy BMI | kg/m2 | 1.632 | 1.510 | 1.458 | 1.384 | 1.414 | 1.346 | 1.146 | 1.107 |

| Father/partner’s BMI | kg/m2 | 1.497 | 1.332 | 1.308 | 1.225 | 1.276 | 1.193 | 1.202 | 1.125 |

| Mother’s educational level | Primary | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Secondary | 0.660 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Higher education | 0.345 | 0.470 | 0.440 | 0.440 | 0.439 | 0.449 | 0.406 | 0.414 | |

| Father/partner’s educational level | Primary | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Secondary | 0.740 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Higher education | 0.520 | 0.755 | 0.704 | 0.768 | 0.663 | 0.735 | 0.694 | 0.768 | |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy | Never | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Until pregnancy was known | 0.924 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Continued during pregnancy | 1.442 | 1.034 | 1.220 | 1.003 | — | — | — | — | |

| Mother’s age (birth) | years | 0.899 | 0.957 | 0.947 | 0.987 | 0.982 | — | 0.967 | — |

| Parity (birth) | Number of times given birth | 0.972 | — | — | — | — | — | 1.003 | — |

| Maternal gestational weight gain (birth) | kg/wk | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.989 | — |

| Delivery type (birth) | Vaginal | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Cesarean | 1.365 | 1.000 | 1.119 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Gestational age (birth) | weeks | 1.032 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Birthweight z-score (birth) | z-score | 1.025 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Sex of child (birth) | Male | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Female | 1.293 | 1.044 | 1.140 | — | 1.037 | — | — | — | |

| Ethnicity of child (birth) | Dutch | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Cape Verdean | 3.429 | 1.495 | 1.651 | 1.048 | 1.628 | 1.086 | 1.262 | — | |

| Dutch Antilles | 2.456 | 1.268 | 1.786 | 1.234 | 1.398 | 1.006 | 1.427 | 1.000 | |

| Morroccan | 1.700 | 1.011 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Turkish | 3.118 | 1.727 | 1.498 | 1.102 | 1.267 | — | 1.595 | 1.199 | |

| Surnamese-Creole | 2.438 | 1.021 | 1.194 | — | 1.297 | — | 1.017 | — | |

| Surinamese-Hindustani | 4.482 | 1.712 | 2.657 | 1.423 | 2.496 | 1.434 | 4.722 | 2.642 | |

| Other | 1.373 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Time-dependent variables | Full exp(b)* | Restricted** exp(b)* | Full exp(b)* | Restricted** exp(b)* | Full exp(b)* | Restricted** exp(b)* | Full exp(b)* | Restricted** exp(b) | |

| Mother’s current BMI (age 6) | kg/m2 | 1.305 | 1.275 | ||||||

| Household income (age 0/2/3/6) | Moderate/High | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Low | 1.149 | 1.443 | 2.313 | 2.254 | 1.722 | 1.697 | — | — | |

| Household size (age 6m/2/3/6) | Number of household members | 1.040 | — | — | — | 0.976 | — | 0.944 | 0.998 |

| Mother’s marital/living status (age 0/2/3/6) | Married/registered partner/living together | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| No partner/not living together | 2.168 | 1.833 | — | — | — | — | 1.401 | 1.337 | |

| Smoking exposure in parental house (age 3m/2/3/6) | No smoking | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Smoking | 1.879 | 1.769 | — | — | 1.350 | 1.234 | 1.632 | 1.411 | |

| Child’s BMI z-score | age 0.25 | 1.000 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| age 0.5 | — | — | — | — | 0.960 | — | |||

| age 0.75 | — | — | — | — | 0.887 | — | |||

| age 1.15 | 1.071 | 1.043 | — | — | 0.998 | — | |||

| age 2 | 1.406 | 1.327 | 1.158 | 1.095 | — | — | |||

| age 4 | 1.948 | 1.812 | 1.676 | 1.477 | |||||

| age 6 | 3.335 | 2.864 | |||||||

| Breastfeeding of child (age 3m/1/1/1) | No, never | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Yes, ever | 1.098 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Age fruit/vegetable introduction (age 6m) | < 4 months | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||

| 4–6 months | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| > 6 months | 0.642 | — | 0.777 | — | 0.604 | — | |||

| Sleep day (3m) | 0–4 h | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| 4–6 h | 1.525 | 1.354 | |||||||

| 6–8 h | 0.681 | 0.862 | |||||||

| > 8 h | 0.714 | 0.992 | |||||||

| Sleep night (3m) | < 6 h | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| ≥ 6 h | 0.864 | 0.986 | |||||||

| Sleep (age 2) | h/day | — | — | ||||||

| Screen time (age 2/4/6) | h/day | 1.023 | — | — | — | 1.071 | 1.038 | ||

| Playing outside (age 3/4/6) | h/day | 0.942 | — | 0.814 | 0.876 | 0.956 | — | ||

| Playing sports (age 6) | No | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 0.897 | — | |||||||

| Snack/soda during screen time (age 3) | No, almost never | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Sometimes | — | — | |||||||

| Often or almost always | 1.795 | 1.356 | |||||||

| Snack consumption (age 4/6) | Number of snacks per day (age 6) | — | — | ||||||

| Never (age 4) | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| Once per day (age 4) | — | — | |||||||

| 2 or more times per day (age 4) | — | — | |||||||

| Sweet drinks consumption (age 4/6) | Number of sweet drinks per day (age 6) | 1.016 | — | ||||||

| Less than 1 glass per day (age 4) | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| 1 glass per day (age 4) | — | — | |||||||

| 2 glasses per day (age 4) | — | — | |||||||

| 3 glasses per day (age 4) | — | — | |||||||

| 4 glasses per day (age 4) | — | — | |||||||

| More than 4 glasses per day (age 4) | — | — | |||||||

| Breakfast consumption (age 4/6) | Number of days per week (age 6) | 0.946 | 0.981 | ||||||

| Every day of the week (age 4) | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| 6 days per week or less (age 4) | 1.474 | 1.273 | |||||||

| Cholesterol (age 6) | mmol/L | 1.065 | 1.019 | ||||||

| HDL (age 6) | mmol/L | — | — | ||||||

| LDL (age 6) | mmol/L | 1.047 | 1.002 | ||||||

| Triglyceride (age 6) | mmol/L | — | — | ||||||

*. Exponential value of b coefficients (Odds Ratios) that contribute to the model (< 1: lower value predicts lower chance of obesity at adolescence; >1: higher value predicts higher chance of obesity at adolescence)

**. Restricted model; with less variables so the model becomes more suited to use in primary care; ‘one standard error rule’ was applied to select a more conservative penalty, resulting in a simpler model [42]

Empty cell: variable is not available for that timepoint

— does not contribute to model

Ref: reference category

Predictors Cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and triglyceride at age 6 are often unavailable in practice. Models were rerun without these candidate predictors and did not yield large changes in estimator coefficients or model performance. Variable selection remained unchanged

Please see supplemental Text S3, for a detailed explanation on how to calculate the predicted risk for an individual using the prediction models

Table 3 contains an overview of the model performance metrics. All reported metrics range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating better performance. Unsurprisingly, models incorporating data from later ages give better predictions than models for younger ages. All age models perform well (the lowest ROC AUC is 0.872 for the restricted infant model). There is improvement with increasing age until the age six years models, which have a ROC AUC of 0.954 (full model) and 0.949 (restricted model). Our models have high sensitivity and specificity, so they classify both true positives and negatives well. For our full infant model, only 12% of individuals predicted to become obese are correctly predicted, while age six years has the highest positive predictive value at 19.8%. The performance metrics of the restricted models are, although slightly lower, comparable to that of the full models.

Table 3.

Model performance metrics. Pooled within-sample performance is given for 20 imputed data sets (N = 4,309), alongside the mean and range of out-of-sample performance from 10-fold cross validation

| Age 0 | Age 2 | Age 4 | Age 6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metric | Full | Restricted | Full | Restricted | Full | Restricted | Full | Restricted | |

| ROC AUC | Within-sample | 0.883 | 0.872 | 0.887 | 0.876 | 0.909 | 0.903 | 0.954 | 0.949 |

| Out-of-sample | 0.862 (0.746–0.909) | 0.852 (0.752–0.903) | 0.869 (0.754–0.925) | 0.863 (0.754–0.925) | 0.891 (0.798–0.946) | 0.890 (0.804–0.946) | 0.937 (0.858–0.974) | 0.938 (0.846–0.975) | |

| Sensitivity | Within-sample | 0.802 | 0.792 | 0.826 | 0.812 | 0.840 | 0.823 | 0.897 | 0.890 |

| Out-of-sample | 0.737 (0.597–0.875) | 0.738 (0.622–0.908) | 0.777 (0.581–0.896) | 0.756 (0.572–0.912) | 0.794 (0.639–0.937) | 0.796 (0.668–0.960) | 0.872 (0.683–0.992) | 0.870 (0.667–0.992) | |

| Specificity | Within-sample | 0.800 | 0.791 | 0.798 | 0.788 | 0.823 | 0.817 | 0.876 | 0.871 |

| Out-of-sample | 0.801 (0.781–0.834) | 0.792 (0.761–0.828) | 0.802 (0.782–0.829) | 0.791 (0.771–0.820) | 0.823 (0.797–0.848) | 0.819 (0.798–0.838) | 0.872 (0.851–0.904) | 0.869 (0.850–0.903) | |

| Pos. Pred. Value | Within-sample | 0.120 | 0.114 | 0.122 | 0.115 | 0.139 | 0.133 | 0.198 | 0.190 |

| Out-of-sample | 0.112 (0.086–0.146) | 0.108 (0.080–0.147) | 0.118 (0.089–0.163) | 0.110 (0.084–0.154) | 0.133 (0.104–0.183) | 0.130 (0.101–0.174) | 0.189 (0.125–0.250) | 0.186 (0.117–0.249) | |

Sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value based on a cut-off value of 0.5

Additionally, the cross-validation ranges show that our model performance metrics are sensitive to the sample selected.

Please see supplemental Tables S6, S7, and S8 for the results of the sensitivity analyses.

Discussion

This study aimed to predict the risk of children being obese at adolescence (10–14 years of age) with data available at age 0, 2, 4, and 6 years. The study created eight models that predict obesity, including full and restricted models for the different age groups. The final models included not only predictors measured at time of risk prediction, but also predictors collected at previous ages, e.g. parental BMI (prepregnancy/at enrolment), parental education level, ethnicity of the child, and the child’s previous BMI z-score. While the models showed high sensitivity and specificity, the positive predictive value was low due to the small number of obesity cases in the sample. The combination of a high ROC AUC and a low positive predictive value indicates that the models were effective in predicting low obesity risk but produce a sizeable number of false positives when predicting those with an increased risk.

Findings in relation to other studies

Previous studies have developed childhood overweight and obesity prediction models for various ages (assessment and outcome) and populations. The relevant predictors found are generally concurrent with our findings. In addition, the AUC of our model seems to indicate that it has a good performance/discriminative ability, also when considering other models.

A review from Ziauddeen et al. [32] on prediction models for childhood overweight and obesity included eight studies [16, 45–51] that developed prediction models in populations from Germany, Greece, Finland, the Netherlands, UK, and USA (Latino). Predictors that were included in half or more of the prediction models were gender, birthweight, maternal BMI, maternal smoking during pregnancy and child growth measurements (weight change or standardized BMI). In addition, paternal BMI was included in all the three studies that had considered it as a predictor. The majority of our prediction models (both restricted and full models) also include maternal BMI, paternal BMI and child growth measurements. Sex is included in three of our four full models, but only made it into the age 0 restricted model. Birthweight z-score is only included in our full model for age 0, this is probably because the most recent growth/BMI z-score measurements are more indicative of future obesity for the models for age 2, 4, and 6. Smoking during pregnancy is only included in our full and restricted models for age 0 and 2. Like one study in the review, we also considered smoking in the parental house as a predictor and it is included in the full and restricted models for age 0, 4 and 6. This could be an indication that not solely the smoking of the mother is of importance for the risk prediction of childhood obesity, but also that of other household members.

Predictors that are included in all of our (full and restricted) models beside parental BMI, are maternal and paternal education level and ethnicity of the child. These predictors were not as frequently selected in the study’s in Ziauddeen’s review [32]. Maternal education was only included in one of three studies considering the variable; paternal education was considered in one, but was not included in the model; and parental education was considered and included in one study. Ethnicity of the child was included only in one of three studies considering the variable as candidate predictor. The model development ROC AUC of the studies ranged from 0.64 to 0.91 (median 0.78, interquartile range (IQR) 0.70 to 0.81) [32], showing that our (restrictive) models had good performance metrics with ROC AUC values of 0.872–0.949.

A review on prediction models for early Childhood Obesity by Butler et al. [52] included seven studies of which five [16, 47, 49–51] were included in the previously mentioned review by Ziauddeen et al. The two studies not included in the previous review were by Levine et al. [30] and Zhang et al. [53] and were both performed in UK populations. Levine et al. developed a model to predict obesity at 5 years of age and preselected the predictors parental obesity, early weight gain, ethnicity, birthweight and maternal education, but had no further selection process during modeling and had not reported an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) [30, 52]. Zhang et al. aimed to compare data mining methods with logistic regression in childhood obesity prediction. They developed models to predict overweight/obesity at 3 years using data by 6 weeks and 8 months including birthweight z-score, time of gestation, sex, BMI, height z-score, length z-score, weight gain z-score. AUC’s ranged from 0.68 to 0.84 [52, 53].

A narrative review of machine learning studies that identify key determinants of childhood obesity by LeCroy et al. [54] concluded that during early to middle childhood, child’s weight history and parental overweight/obesity (current or prior) are key determinants of childhood obesity risk, whereas social factors and physical inactivity appear to be important risk factors for obesity during middle childhood to adolescence. In our study we used predictor information from early childhood to middle childhood, showing similar results: key predictors were child weight history (inclusion of at least the two most recent child BMI measurement in all models; except, the infant model where only birthweight is available and included in the full model, see Table 2) and prior or current parental BMI (where the models for age 6 included the mother’s current BMI in addition to pre-pregnancy BMI and father’s BMI at enrollment). Unfortunately, we did not have father’s current BMI measurement available to include as candidate predictor to see if a more recent BMI of the father could still have contributed to the model.

Two previous studies by Steur et al. [16] (included in the Ziauddeen review) and Welten et al. [17] had also developed prediction models in a Dutch birth cohort. Both the prediction models for overweight at the age of eight years were developed in the PIAMA (Prevention and Incidence of Asthma and Mite Allergy) study. The model by Steur et al. can be applied at birth and the model by Welten et al. at every age between three months and six years. Predictors included in both these models were parental BMI, birthweight, sex, and smoking in the house. Predictors included in either of the models were hospital delivery (Steur et al.), ethnicity (Welten et al.), and growth characteristics at the time of risk prediction (Welten et al.) (Steur et al. could not take this into account as it was a model to be applied to newborns)). A difference between our model and their models is that Steur et al.’s and Welten et al.’s models predict overweight at the age of eight years, while our model predicts obesity at the age of 10–14 years. Like the study by Welten et al., we also found parental BMI, parental educational level, and child growth to be important predictors. Where Welten et al. developed one model to be applied at all ages between 3m-6y, we have created multiple models to be applied at set ages (0,2,4,6 years), allowing for age-specific predictors (and not only growth, longitudinally included in Welten et al.’s model) to be included in the model to resemble the different periods of consultation in Dutch Preventive Child Health Care [15]. The AUC after internal validation were 0.754 (Steur et al.) and 0.845 (Welten et al.). The AUC of the models by Welten et al. before validation were also given per age group and ranged from 0.822 to 0.942, with the highest AUC for the oldest age of assessment, this is similar to our models, but for a different outcome age.

See supplemental Text S3, for a further discussion on some remaining studies that developed prediction models, but were not included in the reviews or part of the Dutch cohort studies discussed above.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that we were able to use data from the Generation R Study, a population-based birth cohort. We could include many participants (N = 4,309) in this study over a long age range. Due to loss to follow-up over time, with generally a higher proportion of lower socioeconomic status (SES) participants being lost, our sample may underrepresent low SES participants. The general characteristics of the mothers who were enrolled in the Generation R study at baseline, and who remained in the study until the child’s age of 13 years are shown in the design and cohort paper and compared to the baseline characteristics, the mothers who still participated in the Generation R study at follow up were older, more frequently of Dutch nationality and higher educated [18]. The results of the sensitivity analysis comparing the population for analysis with the excluded participants seem to be in line with this, see supplemental Table S6. This is, as mentioned earlier, a pattern similar as in other large scale cohort studies. This selection towards a higher socio-economic status may have resulted in more conservative estimates of the prediction model and reduced generalizability towards groups of a lower socio-economic position. Although, there is a selection towards a higher socio-economic status we believe the study population was still diverse. In addition, external validation of the model is still needed before applying the model in practice. Performing such external validations in a sample representative of the Dutch population and looking at specific subgroups could further enlighten if the model might be less generalizable for certain groups. Our study sample included children who were part of the same families. To look into the effects this could possibly have had on the study results we had conducted sensitivity analyses. From our study sample, we selected at random one participating child per mother to be included in the new study sample. We ran our analyses again on the imputed dataset using this new sample. This resulted in similar findings.

Our outcome was obesity according to the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) definition using age and sex specific cut-off values [26]. These cut-off values do not account for puberty stage. As our outcome was obesity assessed at age 10 to 14, it may be that puberty has affected our results. The number of obesity cases in the analysis sample was only 142 (3.3%). We used ROSE oversampling to focus prediction on the obesity/non-obesity difference, but due to the low obesity prevalence, we found positive predictive values ranging from 11.4 to 19.8%. The prevalence of obesity in the sample is similar to the population for all children in the Netherlands, where the prevalence was 3.5% in 2021 [4]. Within the children at 6 years who were incorrectly predicted as obese, there is a larger proportion of children (51.0%) with actual overweight at 10–14 years of age, compared to the proportion with overweight within the whole group (13.5%). Since overweight is a pre-condition for obesity, preventive measures aimed at reducing obesity risk by promoting a healthy life style might also benefit these children classified as false positive. However, it is then important that preventive measures are non-invasive and avoid stigmatization or the development of eating problems.

We chose to develop a prediction model that could be applied to all children (obese and non-obese at time of prediction). This way risk estimates for future obesity can be provided for all children visiting the Dutch Preventive Child Health Care, supporting health professionals in their decision making. For this purpose the model would not only need to perform well in children who are already obese at time of risk estimation, but also in those children that are not yet obese at time of risk estimation but will be in the future. Therefore, we have performed sensitivity analyses to assess the sensitivity of the full model at age 6 in children without obesity at time of risk prediction. Using a threshold of 0.5, the sensitivity of the model as previously assessed in all children was 0.897 (Table 3) and in the subsample of children without obesity at time of risk assessment it was 0.854 (Table S8). This would indicate that the sensitivity is not only good in children that are already obese at time of risk prediction.

Practical implications

Prevention of obesity, rather than treatment, is the more effective strategy [52]. Evidence suggests that greatest reduction in obesity is likely when targeting children at-risk at very early age (< 5 years), as reductions are more difficult to achieve at later age [55–57]. Multicomponent interventions that focus on lifestyle changes, targeting physical activity, nutrition, behaviour change, as well as parental involvement are key to the treatment of obesity. The model presented could be used to early detect children at-risk and provide timely support.

External validation is needed before the model is to be used in practice. Assuming such validation does not uncover inherent weaknesses, the model is suitable for application in the Dutch Preventive Child Health Care. A personalized risk prediction can support preventive child health care professionals in their decision making, enhance the registration and monitoring of important predictors for obesity, and enable preventive care targeted to the child [52]. External validation would also be needed to determine how well generalizable the prediction models are for other populations than the Dutch children or specific subgroups.

The performance of the prediction models improves with later age. This is logical since the duration between predictor measurements and the outcome becomes shorter, making it easier to estimate more reliable risk estimates. However, at later ages the possibilities for intervention strategies decrease. It is therefore important that health care professionals take into account at what ages to apply the prediction model, taking into consideration the intervention or course of action they want to take for children identified as being at increased risk for being obese in the future.

The sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive values of the model are dependent on the risk threshold that is chosen, see supplemental Table S7 for the models’ predictive performance using cut-off values of 0.25 and 0.72 instead of the 0.5 as reported in Table 3. It is important that users of the prediction model carefully consider the potential impact of false-positive versus false-negative predictions when choosing a risk threshold. These consequences of false-positives and false-negatives will be dependent on the intended course of action after a positive/negative risk prediction. Health care professionals could therefore set different risk thresholds depending on the intended intervention to be taken after a positive risk prediction. These interventions or courses of action will preferably be included in (clinical) guidelines with information on the risk threshold and specified for different ages and target populations.

In addition, as Levine et al. [30] argued, it is important that health care professionals perform the risk assessment with sensitivity to the parent’s concerns and perceptions. For older ages, this would also include those of the child. The introduction of a risk prediction tool might call for training of health care practitioners on the appropriate usage of the prediction tool, explaining the concept of risk to the parents and the difference in individual and population risk [30]. Also, professionals should anticipate the different types of possible responses by the parents such as: seeking guidance and reassurance; feeling stigmatized or antagonized possibly resulting in refusal to cooperate with the health care professional and disregarding advice; or becoming so alarmed that they will take inappropriate course of action [30]. Some strategies, when communicating with parents, include focusing on understandability of risk using comparative risk information (e.g., comparing to the average risk of a person of that age) [58], emphasizing risk mitigation in actionable steps [59] and using positive framing by shifting communication from weight to health [60]. The application of these models can be embedded in the Dutch Preventive Child Health Care (DPCHC) guideline on childhood overweight [14]. This study already shows that the invasive blood samples at age 6 years to measure cholesterol, HDL and LDL did not add to the predictive value of the model, while monitoring maternal and paternal BMI alongside the child’s BMI does add predictive value. However, further exploration is needed to show how exactly the application of predictive risk models will improve decision-making in a preventive care setting, for example in a predictive tool. The advantages of predictive modelling include objectivity, explicitness, and repeatability. But these alone are not enough. We need more insight into the role of predictive models in the counselling process. Predictive models could help communicate risks, gain insight into the effect of various treatments, and monitor the realized gains resulting from such interventions. The development of a predictive risk model, as in this paper, provides a sensible starting point for such explorations.

Conclusions

In this study, prediction models were developed for prediction of obesity at adolescence using data available at age 0, 2, 4, and 6 years for early monitoring and preventive purposes in Dutch Preventive Child Health Care. Predictors that were included in all the models that they were considered a candidate predictor for, were the baseline variables mother’s prepregnancy BMI, father’s BMI at enrolment, mother’s and father’s educational level, ethnicity of the child; and the time-dependent variables mother’s current BMI, the two most recent child BMI z-score measurements (BMI as monitored in Dutch Preventive Child Health Care), child’s breakfast consumption, child’s cholesterol level and child’s LDL levels. The models showed high sensitivity and specificity. However, the positive predictive value was low due to the small number of obesity cases in the sample. The restricted model contained less variables than the full model, making it more practical for use in daily practice, while being comparable in model performance. These models could be a valuable tool in Dutch Preventive Child Health Care for predicting obesity in adolescence. The practical application of these models, for example in a predictive tool, should include weighing the harms and benefits of correct and incorrect predictions in the context of tailored advice and interventions that are applied.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The Generation R Study is conducted by the Erasmus Medical Center in close collaboration with the School of Law and Faculty of Social Sciences of the Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Municipal Health Service Rotterdam area, Rotterdam, the Rotterdam Homecare Foundation, Rotterdam, and the Stichting Trombosedienst & Artsenlaboratorium Rijnmond (STAR- MDC), Rotterdam. We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of children and parents, general practitioners, hospitals, midwives, and pharmacies in Rotterdam.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the curve

- AUROC

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- BMI

Body mass index

- DPCHC

Dutch Preventive Child Health Care

- HDL

High-density lipoprotein

- IOTF

International Obesity Task Force

- IQR

Interquartile range

- LASSO

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- LDL

Low-density lipoprotein

- m

Months

- PIAMA

Prevention and Incidence of Asthma and Mite Allergy

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- ROSE

Random over-sampling examples

- SES

Socioeconomic status

- UK

United Kingdom

- USA

United States of America

- WHO

World Health Organization

- y

Years

Author contributions

PE, SB, YS, VJ and RG worked on the idea conception; MW, VJ and RG shared the data; MW prepared the data; AH analyzed the data; AH, MW, YS, SP, PE and SB wrote the article; all authors revised the article and had final approval of the submitted and published versions.

Funding

The general design of the Generation R Study is made possible by financial support from the ErasmusMC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport and Ministry of Youth and Families. This project received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (LIFECYCLE, grant agreement No 733206, 2016; EUCAN-Connect grant agreement No 824989; ATHLETE, grant agreement No 874583, LongITools grant agreement No 874739). VJ received funding from a Consolidator Grant from the European Research Council (ERC-2014-CoG-648916). R.G. received funding from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (NWO, ZonMw VIDI 09150172110034, and NWO, ZonMW, grant number 05430052110007) and a European Research Council Starting Grant (ERC-2024-STG-101161004). The study sponsors had no role in the study design, data analysis, interpretation of data, or writing of this report.

Data availability

The data used in this study is derived from the Generation R Study based in Rotterdam. Individual researchers do not have the right to distribute this data from Generation R. For the purpose of verification/validation/replication/meta-analyses, the external researcher can contact our data managers (datamanagementgenr@erasmusmc.nl) and the Director of Generation R, Vincent Jaddoe (v.jaddoe@erasmusmc.nl). Data will be made available via these contact persons after a written agreement about the use of the data has been made.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The general design, all research aims and the specific measurements in the Generation R Study have been approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. New measurements will only be embedded in the study after approval of the Medical Ethical Committee. The reference numbers of the ethical documents are as follows: phase 1 (fetal period) MEC 198.782/2001/31; phase 2 (0–4 years) MEC 217.595/2002/202; phase 3 (6 and 10 years) MEC-2007-413; MEC-2010-084; MEC-2012-165; phase 4 (13 and 17 years) MEC 2015 − 749. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants need to give written informed consent for each phase of the study (fetal, preschool, childhood and adolescence period). For participants under the age of 16, written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardian. From the age of 12 years onwards, children must sign their own consent form, in accordance with Dutch Law. At the start of each phase, children and their parents receive written and oral information about the study. Even with consent, when the child or the parents are not willing to participate actively, specific measurements are skipped or no measurements at all are performed.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Arjan Henryk Jonathan Huizing and Marieke Welten contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity and overweight: World Health Organization (WHO); 09-06-2021 [Available from: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- 2.World Health Organization. Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. World Health Organization; 2009.

- 3.Gezondheidsraad (Health Council of the Netherlands). Overgewicht En obesitas. Den Haag: Gezondheidsraad; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plasmans MHD, van Diest BEPSR, Zantinge EM. Overgewicht| Leeftijd en geslacht jongeren: National Institute of Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) [updated 04-07-2022. Available from: https://www.vzinfo.nl/overgewicht/leeftijd-en-geslacht-jongeren

- 5.Plasmans RvD MHD, Zantinge EM. Overgewicht| Leeftijd en geslacht volwassenen: National Institute of Public Health and the Environment (RIVM); [Available from: https://www.vzinfo.nl/overgewicht/leeftijd-geslacht

- 6.Joseph A, Skelton WJK. Overview of the health consequences of obesity in children and adolescents. In: Post TW, editor. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reilly JJ, Methven E, McDowell ZC, Hacking B, Alexander D, Stewart L, Kelnar CJ. Health consequences of obesity. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88(9):748–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wabitsch M. Overweight and obesity in European children: definition and diagnostic procedures, risk factors and consequences for later health outcome. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159(Suppl 1):S8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardy LR, Harrell JS, Bell RA. Overweight in children: definitions, measurements, confounding factors, and health consequences. J Pediatr Nurs. 2004;19(6):376–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2008;9(5):474–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joseph A, Skelton WJK. Definition, epidemiology, and etiology of obesity in children and adolescents. In: Post TW, editor. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordlund S, McPhee PG, Gabarin R, Deacon C, Mbuagbaw L, Morrison KM. Effect of obesity treatment interventions in preschool children aged 2–6 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4):e053523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peirson L, Douketis J, Ciliska D, Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Ali MU, Raina P. Treatment for overweight and obesity in adult populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ Open. 2014;2(4):E306–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chest-of Holthe JE, Bulk-Bunschoten AMW, Renders CM, Hirasing RA, Beltman M, Timmermans-Leenders EP, et al. JGZ-richtlijn Overgewicht. JGZ Tijdschrift Voor Jeugdgezondheidszorg. 2012;44(4):62–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vanneste YTM, Lanting CI, Detmar SB. The preventive child and youth healthcare service in the Netherlands: the state of the Art and challenges ahead. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Steur M, Smit HA, Schipper CM, Scholtens S, Kerkhof M, de Jongste JC, et al. Predicting the risk of newborn children to become overweight later in childhood: the PIAMA birth cohort study. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6(2–2):e170–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welten M, Wijga AH, Hamoen M, Gehring U, Koppelman GH, Twisk JWR, et al. Dynamic prediction model to identify young children at high risk of future overweight: development and internal validation in a cohort study. Pediatr Obes. 2020;15(9):e12647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kooijman MN, Kruithof CJ, van Duijn CM, Duijts L, van Franco OH. The generation R study: design and cohort update 2017. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(12):1243–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaddoe VW, van Duijn CM, van der Heijden AJ, Mackenbach JP, Moll HA, Steegers EA, et al. The generation R study: design and cohort update until the age of 4 years. Eur J Epidemiol. 2008;23(12):801–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaddoe VW, Mackenbach JP, Moll HA, Steegers EA, Tiemeier H, Verhulst FC, et al. The generation R study: design and cohort profile. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21(6):475–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaddoe VW, van Duijn CM, van der Heijden AJ, Mackenbach JP, Moll HA, Steegers EA, et al. The generation R study: design and cohort update 2010. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(11):823–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hofman A, Jaddoe VW, Mackenbach JP, Moll HA, Snijders RF, Steegers EA, et al. Growth, development and health from early fetal life until young adulthood: the generation R study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2004;18(1):61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaddoe VW, van Duijn CM, Franco OH, van der Heijden AJ, van Iizendoorn MH, de Jongste JC, et al. The generation R study: design and cohort update 2012. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012;27(9):739–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaddoe VW, Bakker R, van Duijn CM, van der Heijden AJ, Lindemans J, Mackenbach JP, et al. The generation R study biobank: a resource for epidemiological studies in children and their parents. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22(12):917–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kruithof CJ, Kooijman MN, van Duijn CM, Franco OH, de Jongste JC, Klaver CC, et al. The generation R study: biobank update 2015. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(12):911–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320(7244):1240–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fredriks AM, van Buuren S, Burgmeijer RJ, Meulmeester JF, Beuker RJ, Brugman E, et al. Continuing positive secular growth change in the Netherlands 1955–1997. Pediatr Res. 2000;47(3):316–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weng SF, Redsell SA, Swift JA, Yang M, Glazebrook CP. Systematic review and meta-analyses of risk factors for childhood overweight identifiable during infancy. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(12):1019–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woo Baidal JA, Locks LM, Cheng ER, Blake-Lamb TL, Perkins ME, Taveras EM. Risk factors for childhood obesity in the first 1,000 days: A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(6):761–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine RS, Dahly DL, Rudolf MC. Identifying infants at risk of becoming obese: can we and should we? Public Health. 2012;126(2):123–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monasta L, Batty GD, Cattaneo A, Lutje V, Ronfani L, Van Lenthe FJ, Brug J. Early-life determinants of overweight and obesity: a review of systematic reviews. Obes Rev. 2010;11(10):695–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ziauddeen N, Roderick PJ, Macklon NS, Alwan NA. Predicting childhood overweight and obesity using maternal and early life risk factors: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2018;19(3):302–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monzani A, Ricotti R, Caputo M, Solito A, Archero F, Bellone S, Prodam F. A systematic review of the association of skipping breakfast with weight and cardiometabolic risk factors in children and adolescents. What Should We Better Investigate Future? Nutrients. 2019;11(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.R Core Team. R: A Language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Buuren S. Broken stick model for irregular longitudinal data. J Stat Softw. 2023;106(7):1–51.37138589 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prev Sci. 2007;8(3):206–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Buuren S. Flexible imputation of missing data. CRC; 2018.

- 39.Menardi G, Torelli N. Training and assessing classification rules with imbalanced data. Data Min Knowl Disc. 2014;28(1):92–122. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the Lasso. J Roy Stat Soc: Ser B (Methodol). 2018;58(1):267–88. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du J, Boss J, Han P, Beesley LJ, Kleinsasser M, Goutman SA, et al. Variable selection with multiply-imputed datasets: choosing between stacked and grouped methods. J Comput Graph Stat. 2022;31(4):1063–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Wainwright M. Statistical learning with sparsity. Monogr Stat Appl Probab. 2015;143(143):8. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fawcett T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2006;27(8):861–74. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies. Bios. 2017;330(2018):14. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Druet C, Stettler N, Sharp S, Simmons RK, Cooper C, Smith GD, et al. Prediction of childhood obesity by infancy weight gain: an individual-level meta-analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26(1):19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manios Y, Birbilis M, Moschonis G, Birbilis G, Mougios V, Lionis C, et al. Childhood obesity risk evaluation based on perinatal factors and family sociodemographic characteristics: CORE index. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172(4):551–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morandi A, Meyre D, Lobbens S, Kleinman K, Kaakinen M, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Estimation of newborn risk for child or adolescent obesity: lessons from longitudinal birth cohorts. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e49919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pei Z, Flexeder C, Fuertes E, Thiering E, Koletzko B, Cramer C, et al. Early life risk factors of being overweight at 10 years of age: results of the German birth cohorts GINIplus and LISAplus. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(8):855–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robson JO, Verstraete SG, Shiboski S, Heyman MB, Wojcicki JM. A risk score for childhood obesity in an urban Latino cohort. J Pediatr. 2016;172:29–34. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santorelli G, Petherick ES, Wright J, Wilson B, Samiei H, Cameron N, Johnson W. Developing prediction equations and a mobile phone application to identify infants at risk of obesity. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e71183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weng SF, Redsell SA, Nathan D, Swift JA, Yang M, Glazebrook C. Estimating overweight risk in childhood from predictors during infancy. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):e414–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Butler EM, Derraik JGB, Taylor RW, Cutfield WS. Prediction models for early childhood obesity: applicability and existing issues. Horm Res Paediatr. 2018;90(6):358–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang S, Tjortjis C, Zeng X, Qiao H, Buchan I, Keane J. Comparing data mining methods with logistic regression in childhood obesity prediction. Inform Syst Front. 2009;11(4):449–60. [Google Scholar]

- 54.LeCroy MN, Kim RS, Stevens J, Hanna DB, Isasi CR. Identifying key determinants of childhood obesity: A narrative review of machine learning studies. Child Obes. 2021;17(3):153–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown T, Moore TH, Hooper L, Gao Y, Zayegh A, Ijaz S, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7(7):CD001871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Szczyrska J. Pediatric obesity - time to act as early as possible Otylosc dziecieca - czas, by Dzialac Jak Najszybciej. Pediatr Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2023;29(4):267–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Hedges LV, Cyr C, Young-Hyman D, Khan LK, Magnus M, et al. Childhood obesity evidence base project: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis of a new taxonomy of intervention components to improve weight status in children 2–5 years of age, 2005–2019. Child Obes. 2020;16(S2):S221–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA. Helping patients decide: ten steps to better risk communication. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(19):1436–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Floyd DL, Prentice-Dunn S, Rogers RW. A Meta-Analysis of research on protection motivation theory. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30(2):407–29. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rothman AJ, Salovey P. Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behavior: the role of message framing. Psychol Bull. 1997;121(1):3–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study is derived from the Generation R Study based in Rotterdam. Individual researchers do not have the right to distribute this data from Generation R. For the purpose of verification/validation/replication/meta-analyses, the external researcher can contact our data managers (datamanagementgenr@erasmusmc.nl) and the Director of Generation R, Vincent Jaddoe (v.jaddoe@erasmusmc.nl). Data will be made available via these contact persons after a written agreement about the use of the data has been made.