Abstract

Background

Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) is a common type of hair loss that affects a large segment of the global population, significantly influencing individuals' appearance and mental health. Existing treatments like minoxidil and finasteride have limited effectiveness and can cause side effects, highlighting the need for alternative therapies.

Objective

This study aims to explore the effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma-derived exosomes (PRP-Exos) in stimulating hair follicle growth and the proliferation of human dermal papilla cells (DPCs), as well as to investigate the mechanisms involved.

Methods

PRP-Exos were isolated and characterized using techniques such as nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and Western blotting. The impact of PRP-Exos on DPC proliferation was measured using CCK-8 assays, while their migration was assessed through Transwell migration and scratch wound healing assays. Flow cytometry was used to analyze cell cycle progression. Hair follicle organ culture was employed to examine the effects of PRP-Exos on hair follicle growth, and in vivo experiments were conducted in a mouse model to assess the influence of PRP-Exos on hair follicles.

Results

DPCs internalized PRP-Exos, which significantly boosted their proliferation and migration, as shown by CCK-8, Transwell migration, and scratch wound healing assays. Flow cytometry revealed that PRP-Exos facilitated cell cycle progression in DPCs. Furthermore, treatment with PRP-Exos resulted in increased levels of β-Catenin and Lef-1, along with decreased expression of SFRP1, indicating activation of the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway. Hair follicle organ culture indicated enhanced hair follicle growth and a prolonged anagen phase, delaying the transition to the telogen phase. In vivo studies demonstrated increased skin thickness, hair follicle diameter, and a favorable anagen-to-telogen ratio in mice, promoting hair growth during the telogen phase.

Conclusions

PRP-Exos show promise as a therapeutic option for AGA by stimulating hair follicle growth through the activation of the Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway. These findings suggest that PRP-Exos could enhance hair follicle regeneration both in vitro and in vivo.

Keywords: Androgenetic alopecia, Platelet-rich plasma, Exosomes, Regeneration

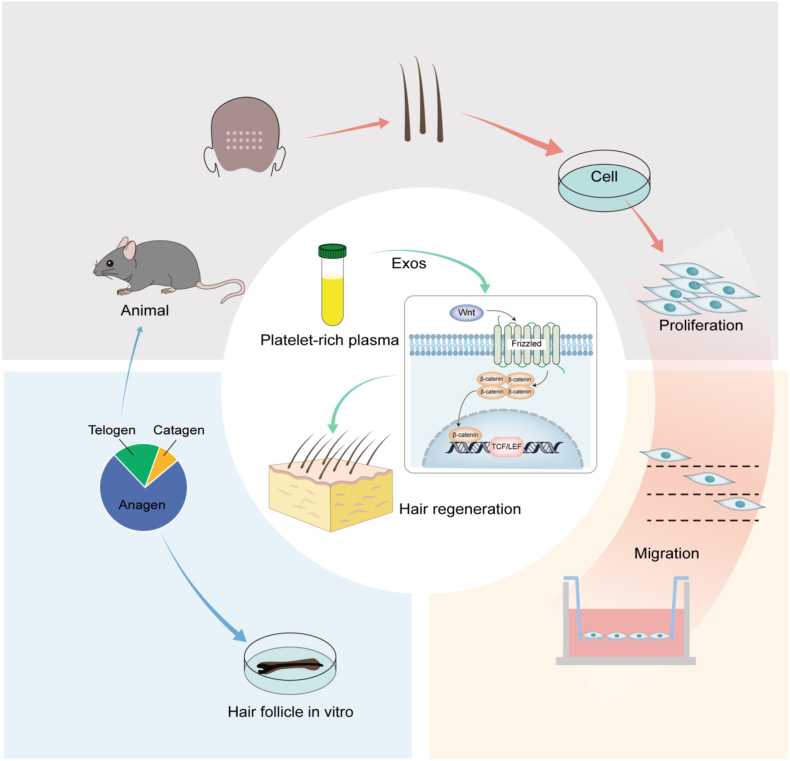

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

First Comprehensive Study on PRP-Exos in Hair Restoration: This research is the first to explore the therapeutic effects of platelet-rich plasma-derived exosomes (PRP-Exos) on hair follicle growth, addressing a significant gap in the current literature.

-

•

Activation of the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway: The study reveals that PRP-Exos stimulate hair follicle growth by activating the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway, a key mechanism in hair regeneration.

-

•

Holistic Experimental Approach: The research employs a multi-faceted design, including in vitro studies on dermal papilla cells (DPCs), ex vivo hair follicle organ cultures, and in vivo animal models, providing a comprehensive understanding of PRP-Exos' effects.

-

•

Clinical Relevance and Potential Impact: The ability of PRP-Exos to stimulate hair follicle growth and prolong the anagen phase presents a promising therapeutic avenue for AGA patients, especially those seeking alternatives to traditional treatments like minoxidil and finasteride, which are often associated with side effects.

1. Introduction

Most hair loss type occurs due to androgenetic alopecia (AGA). Affecting around 30 %–70 % of the global population [1,2]. In men, it typically presents as thinning hair on the crown and a receding hairline, while in women, it is characterized by diffuse thinning. The condition progresses chronically, leading to significant changes in appearance, which can substantially impact self-esteem and social interactions and frequently result in anxiety and depression [3,4]. The exact causes and processes of AGA are still not fully understood, but it is commonly thought to be linked to genetic influences, high levels of androgens, and increased activity of androgen receptors [5,6]. Apoptosis of follicular cells occurs when dihydrotestosterone (DHT) binds to androgen receptors in the dermal papilla with the help of 5α-reductase, inhibition of cell proliferation, and differentiation of matrix cells, ultimately leading to follicular miniaturization [7].

Androgenetic alopecia is only treated with minoxidil and finasteride approved by the FDA. These drugs have a slow onset of action, require continuous use, and discontinuation often results in relapse, significantly reducing patient adherence. Adverse effects include sexual dysfunction, depression, and allergies. Hair transplantation is an invasive procedure limited by the availability of donor follicles and high costs. These treatments alone do not provide satisfactory outcomes or permanent cures [[8], [9], [10]]. Therefore, there is a need to explore alternative therapies for treating AGA.

The extracellular vesicles (EVs) that cells release play an important role in physiological and pathological processes by facilitating intercellular communication [11]. Exosomes, which range from 30 to 150 nm in diameter, belong to a subcategory of extracellular vesicles along with microvesicles and apoptotic bodies, containing microRNA, DNA, mRNA, lipids, metabolites, and cell surface proteins, all encapsulated within a lipid bilayer [[12], [13], [14], [15]] In addition to reflecting the characteristics of the parent cells, these vesicles also interact with neighboring cells and the extracellular matrix. Various clinical applications have been demonstrated for exosomes, including maintain and alter stem cells, serving as biomarkers, enhancing chemotherapy, delivering drugs, and accelerating wound healing by promoting angiogenesis [12,16,17]. Despite their multifunctional potential, the precise mechanisms of exosomes remain incompletely understood. In dermatology, exosomes are widely studied, with recent high-quality research exploring their roles in mediating wound repair, scar formation, photoaging, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and melanoma [[18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]].

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) contains a high concentration of platelets and a variety of components, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), insulin-like growth factor (IGF), serotonin, and dopamine. These components promote cell differentiation, proliferation, and regeneration [24]. PRP is widely used in dermatology for tissue regeneration, scar repair, wound healing, and hair loss [[25], [26], [27], [28]]. Recent research has shown that when PRP is locally injected, it activates and releases VEGF, IGF, and Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF) through α-granules. These substances bind to hair follicle stem cell receptors and activate the MAPK/ERK pathway, encouraging hair follicle growth, differentiation, and extension of the anagen phase [29,30]. Moreover, exosomes have gained attention as they possess low immunogenicity and are easy to store, stable, and controllable, making them a significant focus of research [31]. There is no comprehensive research on PRP-derived exosomes (PRP-Exos) in hair growth. Consequently, our goal is to examine how PRP-Exos influence human hair follicles and to delve into the molecular processes that contribute to hair growth.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Isolation of human PRP

PRP was obtained using a two-step centrifugation method [32]. Blood was drawn from healthy volunteers into anticoagulant tubes. The tubes were then placed in a centrifuge at 200 g for 10 min, resulting in three layers. Plasma and platelet layers were separated and centrifuged for 10 min at 1000 g. A three-quarters volume of platelet-poor plasma was removed, leaving the remainder as PRP. The obtained PRP from each group was analyzed for platelet concentration using an automated blood analyzer. All blood samples used in this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Jiangsu Hospital (Ethics number: 2023-SR-524).

2.2. Exosomes isolation from PRP

The exosomes were isolated using the ultracentrifugation method described by Théry et al. [33]. The procedure is as follows: Centrifuge at 300 g for 10 min, then at 1500 g for 15 min, and finally at 3200 g for 20 min. Retain the supernatant after each step to remove cell debris. Subsequently, centrifuge at 20,000 g for 30 min to remove the pellet, retaining the supernatant to eliminate large vesicles and subcellular units. Filter the supernatant through a 0.22 μm filter for sterilization. Centrifuge at 100,000 g for 70 min, discard the supernatant, and the exosomes will be located at the bottom and sidewalls of the centrifuge tube. Wash the exosomes with sterile 1× PBS, then centrifuge the collected exosomes again at 100,000 g for 70 min. Thoroughly resuspend the exosomes in 50 μL of sterile PBS, to determine the concentration of protein.

2.3. Identification of PRP-Exos

Diluted exosomes were analyzed using a nanoparticle tracking analyzer to determine size distribution (Malvern, UK). The exosomes were fixed, negatively stained with 2 % uranyl acetate, and air-dried at room temperature. Images were captured by electron microscope (HT7700, Nanjing, China). The surface protein markers CD9, CD63 and TSG101 were confirmed by Western blot analysis [34].

2.4. Cells and cell culture

The human dermal papilla cells (DPCs) were isolated from hair follicles obtained from patients who had undergone hair transplants and provided informed consent. During the isolation process, excess fatty tissue and long hair shafts were removed, leaving a 2 mm region containing the hair bulb. Dermal papillae were then isolated using a two-step enzymatic digestion method. First, 2 % collagenase D was added to the specimen and incubated at 37 °C in a cell culture incubator for 2.5–3 h. The release of dermal papillae was monitored every 30 min, and when over 80 % of the dermal papillae were detached or semi-detached, the digestion was stopped by adding three times the volume of high-glucose DMEM. The mixture was then centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 5 min, and the resulting pellet, containing dermal papillae, fibrous tissue, residual hair, and other cells, was resuspended in PBS and centrifuged again. The final pellet was cultured in 20 % medium at 37 °C in a cell culture incubator with 95 % air and 5 % CO2. DPC growth was observed after three days, with cells typically adhering within seven days. The stably growing dermal papilla cells were sent to Xinrun Bio (Wuxi, China) for immortalization. The cells were passaged upon reaching 80–90 % confluence, with medium changes every 2–3 days.

2.5. Identification of HDPCs

The DPCs were characterized using alkaline phosphatase staining. Coverslips were placed in a 24-well plate, with each well seeded with 2.0 × 104 cells. The cells were fixed with a 4 % paraformaldehyde solution. Then, a BCIP/NBT (Beyotime; C3206, China) staining working solution was prepared and incubated at 37 °C in the absence of light for 48 h. Following this, the plates were carefully transferred for microscopic examination, and the staining results were recorded.

2.6. Labeling and uptake of exosomes by DPCs

In the cell uptake experiment, we used the Dil Cell Membrane Red Fluorescence Staining Kit (Servicebio; G1750, China) to label the extracted exosome precipitate. The precipitate was suspended in Dil staining working solution, incubated, and then subjected to the exosome extraction procedure outlined earlier to remove excess dye. This resulted in Dil-labeled exosomes, which were co-incubated with DPCs for 24 h. DAPI staining was followed by fixing the cells with 4 % paraformaldehyde and imaging (Leica Thunder DMi8; Leica, Nanjing, China).

2.7. Cell proliferation, scratch wound-healing assays, transwell migration, and flow cytometry analysis

Seed dermal papilla cells (DPCs) at a density of 3000 cells per well. After overnight incubation, replace the medium with media containing various concentrations of exosomes or PBS, following the CCK-8 Kit instructions (MCE, USA). Incubate at 37 °C for 2 h, then measure absorbance at 450 nm using an enzyme-labeled instrument (Thermo Scientific, USA). The cells were seeded and cultured for 24 h to allow them to fully cover the 6-well plate. Create a scratch perpendicular to the horizontal axis using a 200 μL pipette tip. Wash cells thrice with PBS, add serum-free medium with different exosome concentrations and an equal volume of PBS. Capture cell images under an optical microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Analyze images with Image J software by randomly drawing three horizontal lines to calculate the average cell migration distance. After digestion and centrifugation of dermal papilla cells, resuspend them in serum-free medium. Distribute 20,000 cells evenly in Transwell inserts with 8 μm pores (Corning, NY, USA) placed in a 24-well plate. Add DMEM containing 10 % FBS to the lower chamber and different exosome concentrations (5, 10, 50 μg/mL) or PBS to the upper chamber. Incubate at 37 °C for 24 h. Fix cells with 4 % paraformaldehyde, stain with 0.1 % crystal violet, air dry, and observe under a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Quantify migrated cells with three replicates per group. Dissolve PRP-Exos (5, 10 and 50 μg/mL) in exosome-free FBS medium and co-incubate with DPCs for 48 h. Use the Cell Cycle and Apoptosis Analysis kit (Yeasen; 40301, China) and a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, USA) to detect the cycle of DPCs.

2.8. Quantitative real-time PCR

1000 ng of total RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed into cDNA with HiScript III Supermix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) (Vazyme; R323,China). The qRT-PCR experiments were performed using Taq Pro Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2(−ΔΔCT) method, and normalized using GAPDH as the housekeeping gene. The primer sequences used for qRT-PCR were as follows: All the primers used in the real-time quantitative PCR were as follows: β-Catenin, 5′-CTGGGACTCTGCACAACCTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGTGTCGTGATGGCGTAGA-3′ (reverse); Lef1, 5′-CACTCCTGTTGGTGGTCACA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGGGTTCGCTCAAAGGAGAT-3′ (reverse); Wnt5a, 5′-AAAGGGAACGAATCCACGCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGCACGTCTTGAGGCTACA-3′ (reverse); Wnt10b,5′-TAGCAGGCATTGTGTGGAGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAGGTTCTGGGCTGTAGTGG-3′ (reverse); p-GSK3β,5′-GCTGGAGTACACACCTACCG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGAGGGATAAGGATGGTGGC-3′ (reverse).

2.9. Western blot analysis

The DPCs from different treatment groups were fully lysed in lysis buffer containing RIPA and PMSF. The lysates were centrifuged, and the protein supernatant was collected. Loading buffer was added, and the samples were heated in a water bath at 95 °C for 5 min. Subsequently, the samples were loaded onto a 10 % SDS-PAGE gel for electrophoresis (Bio-Rad, USA). Proteins were then transferred onto a PVDF membrane (0.22 μm pore size; Millipore, Waltham, MA, USA). The membrane was blocked in quick block solution for 1 h and briefly rinsed in TBST. The membrane was then incubated with primary antibodies against β-Catenin (1:1000 dilution, CST, 8480, USA), Lef1 (1:1000 dilution, CST, 2230, USA), SFRP1 (1:3000 dilution, Proteintech, 26460-1-AP, Chicago, IL, USA), and β-actin (1:5000 dilution, Servicebio, 15003-100, China), CD9 (1:1500, 20597-1-AP, Proteintech), CD63 (1:1000, 25682-1-AP, Proteintech) and TSG101 (1:2000, 28283-1-AP, Proteintech) at 4 °C for 15 h. β-actin was used as a loading control. Following incubation with the secondary antibody, Protein bands were revealed with an enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (NCM Biotech, China). The bands were visualized using a Tanon 5200 Multi instrument (Tanon, Shanghai, China).

2.10. Experimental animals and dosage protocol

C57BL/6 mice at the age of six weeks were obtained and granted a week to become accustomed to a normal feeding routine. In order to synchronize their hair regrowth patterns, the mice's dorsal hair was uniformly trimmed on a specific day under anesthesia, and then treated with liquid rosin. The mice were randomly categorized into three different segments, with one segment designated as the PBS group (subcutaneous injection, total volume of 1 mL), the exosome group (subcutaneous injection, total volume of 200 μg), and a group treated with 3 % minoxidil, applied topically once daily. Photographic records of the mice were obtained on days 0, 7, 14, 18, and 21 following hair shaving. Utilizing ImageJ software, the shaved area was measured to evaluate the percentage of hair regrowth coverage. Animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Nanjing Medical University (Animal Ethics No: IACUC2307014).

2.11. Histopathological examination via HE staining

The dorsal skin from the mice was removed and cleansed with PBS, thereafter being preserved in 4 % paraformaldehyde for 24 h for fixation purposes. Subsequently, the skin underwent dehydration through a series of ethanol concentrations, escalating from 50 % to 75 %, 85 %, 95 %, and ultimately 100 %.This was followed by clearing with xylene and embedding in paraffin. The paraffin-embedded skin underwent precision slicing, yielding 5 μm-thick sections that were aligned with the longitudinal axis of the hair follicles. Following deparaffinization, the sections underwent rehydration by sequential immersion in ethanol solutions with diminishing concentrations. Subsequently, Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) staining was performed. Images were observed and captured using an Olympus microscope. The thickness of the skin was measured by quantifying the interval separating the granular and basal epidermal layers, as referenced in Ref. [35]. For each sample, three distinct regions were assessed, and their mean thickness was documented per mouse. The diameter of at least 20 visible hair follicles was measured, and the largest diameter was noted for each sample. The anagen phase hair follicles were classified based on their morphology under the microscope [36,37].

2.12. Immunofluorescence analysis

During immunofluorescence staining, the specimens underwent permeabilization using 0.1 % Triton X-100 solution and were subsequently blocked with 5 % bovine serum albumin (BSA). They were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with antibodies against β-Catenin (1:500, GB11015, Servicebio) and Ki67(1:500, GB111141, Servicebio), Subsequently, the samples were incubated with the respective secondary antibodies at ambient temperature for an hour. Following this, the cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. TUNEL staining was executed utilizing a TUNEL apoptosis detection kit (Servicebio, G1504, China), adhering to the manufacturer's guidelines. Finally, the sections were visualized and captured using a fluorescence microscope (Leica THUNDER DMi8, Leica, Nanjing, China).

2.13. Human hair follicles organ

Hair follicles were taken from the back of the scalp of patients who were undergoing hair transplantation (Ethics Approval Number: 2023-SR-524). The follicles were cultured in 24-well plates. The experiment included PBS and exosome groups, with cultures maintained at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 atmosphere. Hair shaft length was measured on days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8, and micrographs were captured using a Zeiss stereomicroscope and an Olympus microscope. The growth phases of the hair follicles were determined. Immunofluorescence staining for β-Catenin, Ki67, and TUNEL followed the procedures outlined in the previous section on immunofluorescence analysis.

2.14. Statistical analysis

All data are reported in the form of mean ± SD. For statistical comparisons among groups, t-tests or one-way ANOVA were applied. The analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism 9, with a significance level set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Preparation and characterization of PRP-Exos and DPCs

Exosomes extracted from PRP were assessed for compliance with international standards through Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and Western blotting. The platelet content in PRP was determined to be 5.24 ± 1.91 times higher than in normal whole blood using an automated blood cell counter (Table 1). The detailed procedures for PRP extraction and activation, along with the isolation of exosomes derived from PRP, were illustrated in Fig. 1A. NTA indicated a peak particle size of 114.4 nm (Fig. 1B). TEM revealed typical cup-shaped or spherical morphology of PRP-Exos (Fig. 1C). Western blotting confirmed elevated expression of exosomal surface biomarkers CD9, CD63, and TSG101 (Fig. 1D). Collectively, these experiments validate the successful isolation and characterization of exosomes from PRP according to established criteria. During microscopic dissection of hair follicles (Fig. 1E and F), the process of hair papilla cell migration was observed, where initially the hair papilla exhibited a garlic bulb-like structure (Fig. 1G). Subsequently, short spindle-shaped hair papilla cells gradually emerged and migrated out (Fig. 1H), eventually transforming into elongated spindle-shaped cells that displayed aggregative growth patterns (Fig. 1I).

Table 1.

Quantitative analysis of platelet concentration before and after centrifugation of whole blood.

| Number | Whole blood (×109/L) | PRP (×109/L) | Fold |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 212 | 621 | 2.93 |

| 2 | 234 | 1269 | 5.47 |

| 3 | 245 | 1014 | 4.14 |

| 4 | 206 | 1660 | 8.06 |

| 5 | 232 | 1295 | 5.58 |

| Mean ± SD | 225.80 ± 16.25 | 1171.80 ± 384.46 | 5.24 ± 1.91 |

PRP: Platelet-Rich Plasma.

Fig. 1.

Preparation and Characterization of Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) and PRP-derived exosomes (PRP-Exos). (A) Flowchart illustrating the preparation of PRP and the isolation of PRP-derived exosomes. (B) Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) showing the size distribution of exosomes. (C) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of PRP-Exos. Scale bar: 100 nm. (D) Western blot analysis of surface protein markers in activated and unactivated PRP-Exos. (E and F) Hair follicles isolated from the scalp. (G–I) Microscopic observation of hair papilla cell migration process. Scale bar: 100 μm. (J) Uptake of Dil-labeled PRP-Exos by DPCs. Scale bar: 100 μm. (K) Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining for the identification of DPCs. Scale bar: 100 μm.

3.2. Internalization and characterization of PRP-Exos in DPCs

Human dermal papilla cells were incubated with PRP-Exos labeled with the fluorescent dye Dil (red) for 24 h, followed by DAPI staining. Fluorescence microscopy confirmed the internalization of PRP-Exos by the dermal papilla cells (Fig. 1J). The DPCs demonstrated positive alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining, indicating their characteristic clustered and vortex-like growth patterns. ALP, a specific marker associated with hair follicle induction, exhibited positive expression (Fig. 1K).

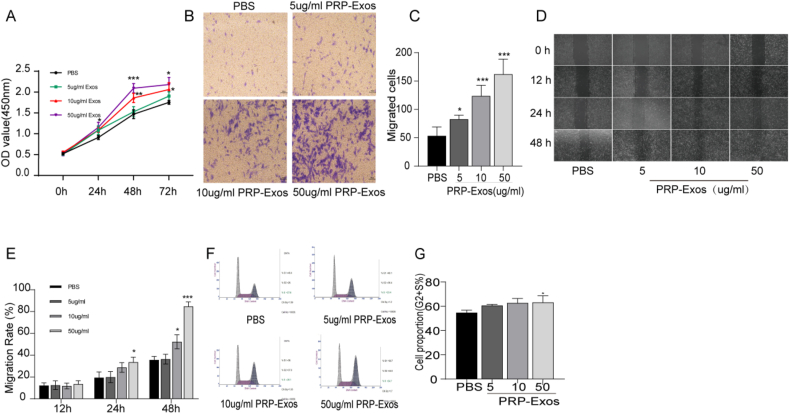

3.3. PRP-Exos promotes proliferation and migration of DPCs

Co-culturing DPCs with PRP-Exos at varying concentrations was used to assess cell proliferation and migration. The CCK-8 assay demonstrated that PRP-Exos significantly enhanced DPC proliferation at 24, 48, and 72 h (Fig. 2A). Significant differences were observed at 24 h in the 50 μg/mL PRP-Exos group compared to the PBS group, and at 48 h in the 10 μg/mL PRP-Exos group, with the 50 μg/mL concentration showing the most pronounced effects. Transwell migration assays revealed a dose-dependent increase in DPC migration with PRP-Exos (Fig. 2B and C). Scratch wound healing assays indicated that PRP-Exos markedly improved wound closure, with the 50 μg/mL treatment exhibiting the most significant effect (Fig. 2D and E). Cell cycle analysis quantified the proliferative index (PI) = (S + G2/M)/(G0/G1 + S + G2/M), showing that 50 μg/mL PRP-Exos significantly promoted DPC proliferation (Fig. 2F and G).

Fig. 2.

Effects of PRP-Exos on DPCs proliferation and migration. (A) Proliferation of DPCs treated with PBS and PRP-Exos. (B) Migration of DPCs treated with PBS and PRP-Exos. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Quantitative analysis of the number of migrated cells from (B). (D) Scratch wound assay of DPCs treated with PBS and varying concentrations of PRP-Exos. Scale bar: 100 μm. (E) Quantitative analysis of migration rates from (D). (F and G) Flow cytometry profiles of the cell cycle distribution in DPCs with quantification of cells in the S and G2 phases. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. n ≥ 3; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

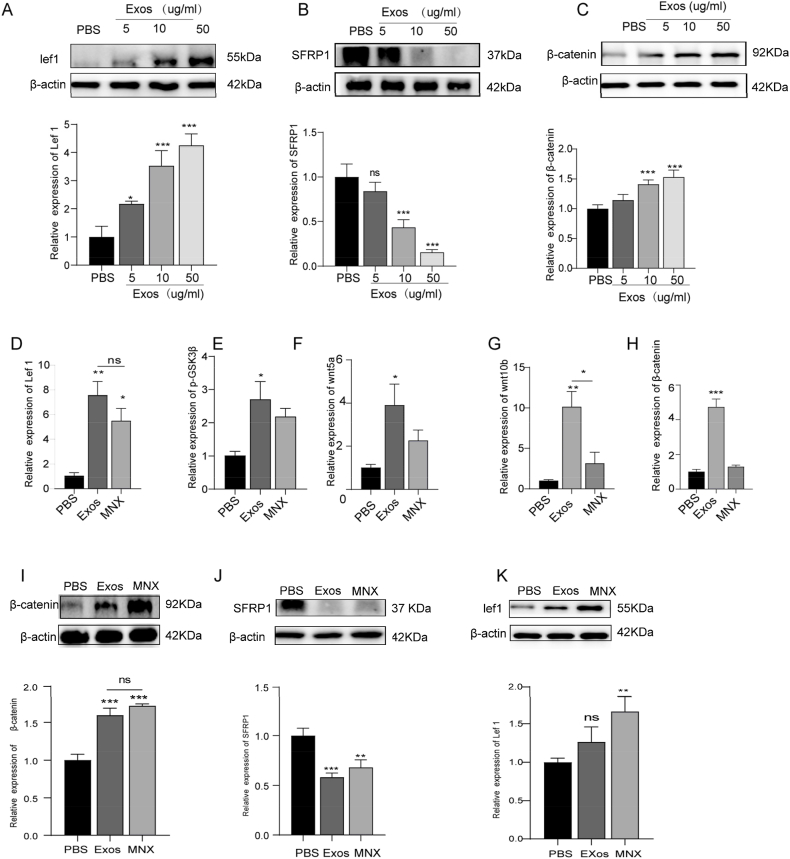

3.4. PRP-Exos enhance DPC proliferation and hair follicle growth via the Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway

The Wnt/β-Catenin pathway is integral to hair morphology and growth, while Secreted Frizzled-Related Protein 1 (SFRP1) attenuates Wnt/β-Catenin signaling by inhibiting Wnt protein binding and signal transduction, thereby influencing the proliferation and differentiation of hair follicle-associated cells. This study aimed to determine whether the Wnt signaling pathway is pivotal in the hair growth promotion induced by PRP-Exos. Following PRP-Exos treatment, SFRP1 levels in dermal papilla cells were reduced, whereas β-Catenin and its downstream target Lef-1 were significantly upregulated in a dose-dependent manner, with notable effects at 10 μg/mL and 50 μg/mL concentrations (Fig. 3A–C). Moreover, qRT-PCR analysis of dorsal skin samples revealed a significant increase in mRNA expression of p-GSK3β, Wnt5a, Wnt10b, β-Catenin, and Lef-1 following PRP-Exos treatment (Fig. 3D–H). Western blot analysis further demonstrated a substantial elevation in protein levels of β-Catenin and Lef-1 (Fig. I–K), alongside a concurrent reduction in SFRP1 protein levels, suggesting that PRP-Exos facilitate SFRP1 downregulation, p-GSK3β and β-Catenin upregulation, and the activation of β-Catenin nuclear translocation within the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway.

Fig. 3.

PRP-Exos increased DPCs' proliferation and hair follicle growth by Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway. (A-C) Western blot analysis of protein levels of Lef1, β-Catenin, SFRP1 in DPCs subjected to different treatments. (D–H) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mRNA levels for Lef1, p-GSK3β, Wnt5a, Wnt10b, and β-Catenin in animal skin tissues. (I–K) Western blot analysis of the relative protein levels of Lef1, β-Catenin, and SFRP1 in DPCs 14 days after treatment with PBS, PRP-Exos, or Minoxidil. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 n = 3.

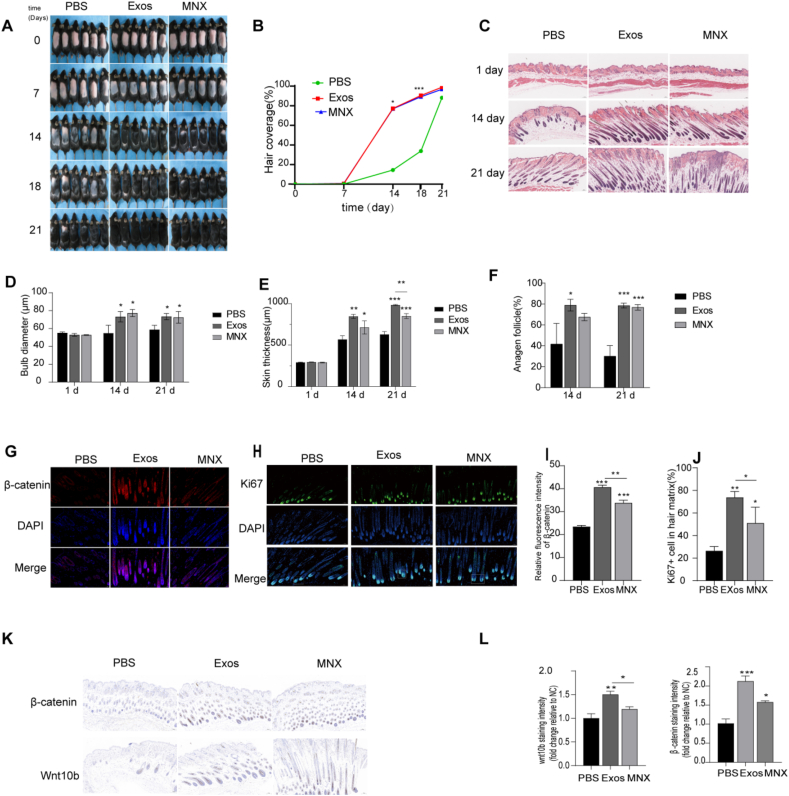

3.5. PRP-Exos enhance skin thickness and follicle diameter, accelerating the transition from telogen to anagen phase

At 7 weeks of age, C57BL/6 mice entered a synchronized telogen phase following depilation, marked by pink skin. As new hair growth began, the skin gradually darkened. Mice were treated with either 3 % minoxidil, PRP-Exos, or were treated with PBS as negative controls. By day 7, the PRP-Exos group displayed diffuse gray skin, while the minoxidil group showed significant graying, indicating the onset of the anagen phase. In contrast, the negative control group retained pink skin. By day 14, visible hair regrowth was observed in both the PRP-Exos and minoxidil groups, surpassing that of the negative control group. By day 21, the dorsal skin of mice in the PRP-Exos and minoxidil groups was nearly fully covered with hair (Fig. 4A). The extent of hair coverage in the PRP-Exos-treated mice was comparable to that in the minoxidil group (Fig. 4B). Histological examination at various time points revealed increased skin thickness, follicle diameter, and a higher proportion of anagen-phase follicles in the PRP-Exos and minoxidil groups compared to the negative control group. Notably, PRP-Exos treatment led to greater increases in skin thickness, surpassing both the negative control and minoxidil groups (Fig. 4C–F). Ki67 is a nuclear antigen reflecting cellular proliferation, predominantly expressed in rapidly proliferating hair matrix keratinocytes [38]. During the early stages of hair growth, Ki67-positive hair matrix cells proliferate and differentiate into various follicular cells, facilitating hair shaft elongation. Conversely, during the resting phase, Ki67 expression is minimal. Therefore, the proportion of Ki67-positive cells in the hair matrix serves as a critical indicator for assessing follicular proliferation. The PRP-Exos therapy group exhibited a markedly increased number of Ki67-positive cells, differing significantly from the minoxidil and non-treated control groups (Fig. 4H and J). It displayed a substantial increase in the mean fluorescence intensity of β-Catenin, a protein associated with hair growth, when compared to both the negative control and minoxidil groups (Fig. 4G and I). Immunohistochemical staining showed the average staining intensity of Wnt10B in the PRP-Exos group showed significant differences compared to both the negative control and minoxidil groups. The expression of β-Catenin, a protein associated with hair growth, was significantly higher in both the minoxidil and PRP-Exos treatment groups compared to the negative control group, with the PRP-Exos group exhibiting the highest expression levels (Fig. 4K and L). The observed outcomes imply that PRP-Exos effectively stimulate the transformation of mouse dorsal hair follicles, shifting them from the resting (telogen) phase to the active growth (anagen) phase, thus promoting hair regrowth.

Fig. 4.

PRP-Exos effects on hair regrowth and follicle morphology in mice. (A) Representative images of dorsal skin at 0, 7, 14, 18, and 21 days post-treatment. (B) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of hair regrowth areas on the backs of mice at days 0, 7, 14, 18, and 21. (C) HE staining of skin sections from mice treated with PBS, PRP-Exos, or minoxidil. Scale bars: 100 μm. (D–F) Quantitative measurements of hair bulb diameter, dermal thickness, the proportion of anagen-phase hair follicles in the PBS, PRP-Exos, minoxidil groups at specified time points. (G) Immunofluorescence staining for β-Catenin (red) in hair follicles from mice after 14 days of treatment. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 100 μm. (I) Quantification of β-Catenin fluorescence intensity in the hair matrix. (H) Immunofluorescence images of Ki67 (green) in hair follicles. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 100 μm. (J) Percentage of Ki67-positive cells in the hair matrix. (K–L) Quantitative analysis of immunohistochemical staining for β-Catenin and Wnt10b in dorsal skin samples from mice treated for 14 days, expressed as fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units). Scale bar: 100 μm. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n ≥ 3). Statistical significance: ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA.

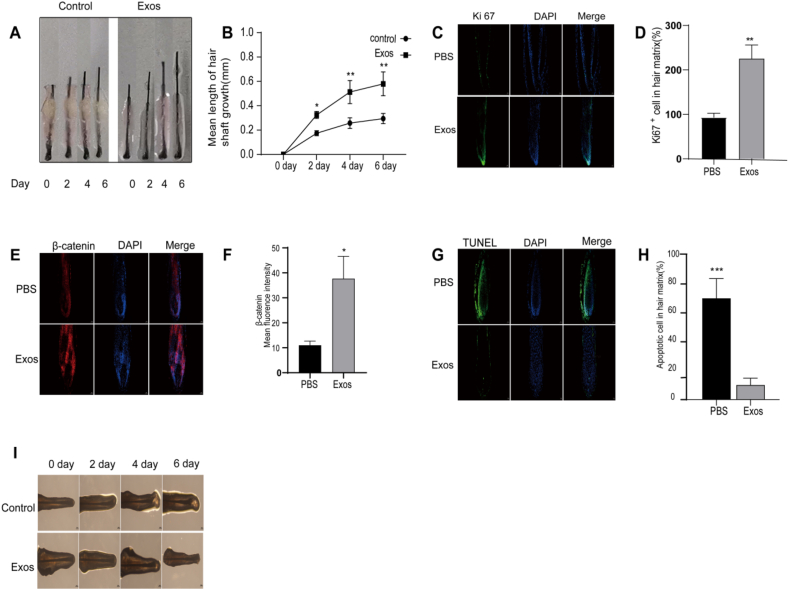

3.6. PRP-Exos promotes hair follicle growth and extends the anagen phase

The utilization of human scalp hair follicle organ cultures serves as an outstanding preclinical platform for hair-related investigations, enabling sustained growth of follicles over multiple days while preserving their structural integrity and epithelial-mesenchymal crosstalk. To enhance our understanding of PRP-Exos’ effects on follicular functionality and hair growth potential, we exposed cultured hair follicles to 100 μg/mL of PRP-Exos in vitro, employing PBS as a negative control. Our data indicated a pronounced increase in hair shaft lengthening in the PRP-Exos-treated group versus the control on days 2, 4, and 6. (Fig. 5A and B). Following PRP-Exos treatment, a significant increase in Ki67 expression within the follicles was observed, suggesting that exosomes promote follicular proliferation (Fig. 5C and D).

Fig. 5.

PRP-Exos Promote hair shaft elongation and delay transition from anagen to catagen phase. (A, B) Photographs of hair follicles cultured in vitro with PRP-Exos or PBS, showing elongation recorded every other day for 6 days. (C, D) Representative images of Ki67 immunofluorescence staining and quantitative analysis of the proportion of Ki67-positive cells in hair follicles. Scale bars: 50 μm. (E, F) β-Catenin immunofluorescence staining and quantitative analysis of β-Catenin fluorescence intensity in hair follicles treated with PRP-Exos or PBS. Scale bars: 50 μm. (G, H) TUNEL fluorescence staining and the proportion of TUNEL-positive cells in hair follicles. Scale bars: 50 μm. (I) Representative images of hair follicle bulbs under different treatment conditions. n = 4 in each group. Scale bars: 200 μm. Statistical significance: ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

β-Catenin is a key protein involved in maintaining the inductive activity and proliferative function of dermal papilla cells in hair follicles. It plays a crucial role in signaling pathways, cell adhesion, and communication. By modulating gene expression, β-Catenin supports the normal function and healthy growth of dermal papilla cells, promoting overall follicular development and regeneration. Immunofluorescence analysis showed that follicles in the Exos group had higher fluorescence intensity of β-Catenin compared to the control group, indicating that exosomes enhance the activity and proliferation of dermal papilla cells (Fig. 5E and F).

The TUNEL assay is a commonly used method for detecting cellular apoptosis by identifying DNA fragments generated during apoptotic signaling cascades. In the control group, there was a significant increase in apoptotic cells within the hair follicles. However, treatment with Exos resulted in a decrease in the proportion of apoptotic cells (Fig. 5G and H).

Morphological changes in the dermal papilla and hair matrix regions are critical indicators for distinguishing between the growth and regression phases of hair follicles. During the early stages of regression, notable morphological changes occur, such as thinning of the hair matrix, an oval-shaped dermal papilla, and a significant decrease in melanin content. These changes serve as important criteria for identifying the hair follicle growth cycle stage [39]. In the control group, regression began from day 4 onwards, characterized by thinning of the hair matrix, reduced melanin content, and partial detachment of the dermal papilla from the hair matrix by day 6, gradually leading to a woolly appearance (Fig. 5I). In contrast, the Exos group maintained a favorable growth phase status on day 6, with a lower incidence of regression compared to the control group.

In conclusion, PRP-Exos treatment stimulates hair growth in scalp follicles and delays their progression toward the regression phase.

4. Discussion

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are essential mediators of intercellular communication, carrying miRNAs, long non-coding RNAs, bioactive lipids, proteins, and DNA. These components are transferred from donor to recipient cells, thereby influencing the function and behavior of the recipient cells [40,41]. Recently, EVs from various sources have been extensively utilized in treating osteoarthritis, uveitis, sepsis, tissue repair, wound healing, and as drug delivery vectors, impacting the progression of multiple diseases [[42], [43], [44], [45]]. PRP is rich in a variety of growth factors, notably VEGF, EGF, and TGF-β that play pivotal roles in promoting tissue repair and regeneration processes. PRP-Exos have been shown to facilitate chronic wound healing by activating YAP [46], prevent femoral head necrosis via the Akt/Bad/Bcl-2 signaling pathway [47], and promote wound healing in diabetic mice by activating the Akt signaling pathway and enhancing chronic diabetic wound remodeling [48]. Additionally, the bioactive factors released by PRP can be encapsulated and concentrated within PRP-Exos [49]. Studies have demonstrated that these extracellular vesicles retain the biological functions of their source cells, offering advantages such as stability, ease of storage, and low immunogenicity when applied directly [50,51]. However, there is a lack of comprehensive research on PRP-Exos in the field of hair growth, underscoring the need to explore their potential in treating androgenetic alopecia (AGA) as a critical area of investigation.

This study investigates the role of PRP-Exos in promoting hair growth, elucidating their mechanisms and potential applications. Initially, we successfully isolated and characterized PRP-Exos, which exhibited a peak particle size of 114.4 nm and displayed a typical cup-shaped or spherical morphology. The expression levels of exosomal surface markers such as CD9, CD63, and TSG101 were significantly elevated. These findings confirm the successful isolation and characterization of PRP-Exos, laying a solid foundation for subsequent research.

The results of our study demonstrate that PRP-Exos significantly enhance the proliferation and migration of dermal papilla cells (DPCs), which are crucial for hair follicle development and hair growth. Our fluorescence microscopy data confirmed the internalization of PRP-Exos by DPCs. This cellular uptake supports the notion that PRP-Exos can deliver active cargoes directly into DPCs, initiating downstream signaling cascades that promote cellular functions. Furthermore, the positive expression of alkaline phosphatase (ALP), a marker associated with hair follicle induction, alongside the characteristic clustering and whorl-like growth of the cells, underscores the potential of PRP-Exos to modulate the hair follicle microenvironment and facilitate the transition to anagen. CCK-8 assay results indicated that various concentrations of PRP-Exos significantly enhanced DPC proliferation, with notable differences at different time points. Transwell migration and scratch wound healing assays confirmed that PRP-Exos promote DPC migration, a key factor in wound healing and tissue regeneration. Additionally, cell cycle analysis confirmed that PRP-Exos significantly stimulated DPC proliferation. These findings align with existing literature on the role of exosomes from other sources in promoting cell proliferation and migration [[52], [53], [54]].

This study systematically examines the promotive effects of PRP-Exos on DPCs. The Wnt/β-Catenin pathway is pivotal for hair growth [55,56]. Our research demonstrated that PRP-Exos treatment decreased SFRP1 levels in DPCs, while the protein levels of β-Catenin and its downstream effector Lef-1 significantly increased. This suggests that PRP-Exos can enhance hair follicle growth by downregulating SFRP1 and activating the Wnt/β-Catenin. qRT-PCR analysis of mouse dorsal skin under various treatment conditions showed elevated expression of Wnt5a, Wnt10b, p-GSK3β, Lef1, and β-Catenin. Western blotting further confirmed these findings, indicating that PRP-Exos can downregulate SFRP1 expression and activate the Wnt/β-Catenin, promoting hair follicle growth and regeneration (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Schematic illustration of PRP-Exos for stimulating hair follicle growth.

In vivo experiments, mice entered a synchronized telogen phase, during which their dorsal skin gradually turned gray, indicating the onset of the anagen phase [37,57]. The PRP-Exos treatment group demonstrated notable hair regrowth on days 14 and 21, in contrast to the minimal or absent growth observed in the negative control group. The efficacy of PRP-Exos in inducing hair regeneration was comparable to the current gold standard, minoxidil, but without the adverse effects associated with minoxidil, such as contact dermatitis and allergies [58]. Furthermore, histological analysis revealed that PRP-Exos treatment significantly increased skin thickness, hair follicle diameter, and the proportion of anagen hair follicles. PRP-Exos contain angiogenic factors such as VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) and FGF (fibroblast growth factor), which stimulate the formation of microvessels in the dermis. This enhances local blood circulation and nutrient delivery to the skin, leading to increased skin thickness in mice. This mechanism may also be beneficial in improving scalp blood supply in clinical settings, which could promote hair growth in patients, particularly those with androgenetic alopecia [46]. Immunohistochemical staining showed significant increases in p-GSK3β, Wnt10B, and β-Catenin levels following PRP-Exos treatment. Immunofluorescence analysis revealed a substantial increase in Ki67-positive cells and β-Catenin expression levels within the PRP-Exos treatment group, in comparison to the control group. These findings provide additional evidence that PRP-Exos stimulate hair growth through enhanced proliferation of hair follicle cells. To more closely mimic clinical conditions, we obtained hair follicle organs and found that PRP-Exos treatment significantly increased hair shaft elongation in cultured hair follicles. Furthermore, PRP-Exos treatment led to an upregulation of Ki67 and β-Catenin expression, concurrently diminishing the number of apoptotic cells, as indicated by a decrease in TUNEL-positive staining. These results indicate that PRP-Exos facilitate hair growth by enhancing hair follicle cell proliferation and reducing apoptosis.

This study systematically validates through experimental verification and mechanistic analysis that PRP-Exos significantly enhance the proliferation of DPCs and promote hair growth. It provides a novel and effective strategy for hair loss treatment by elucidating the mechanism through which PRP-Exos activate the Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway to stimulate hair follicle growth, thereby addressing existing gaps in the research on PRP-Exos in the field of hair growth. As a therapeutic agent, PRP-Exos offer advantages such as low immunogenicity and high biocompatibility, suggesting promising applications in hair loss treatment and post-hair transplantation care. Additionally, PRP-Exos may have potential applications in other areas of tissue regeneration and repair.

This study focuses on the role of the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway in PRP-Exos-mediated hair follicle regeneration, primarily due to its central regulatory function in the hair growth cycle. The Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway promotes the survival, proliferation, and secretory function of DPCs by regulating downstream factors such as Lef-1, Cyclin D1, and Axin2, thereby activating hair follicle stem cells. Our findings demonstrate that PRP-Exos significantly enhances DPC proliferation and migration, upregulates β-Catenin and Lef-1, and downregulates the Wnt inhibitor SFRP1, indicating its involvement in activating the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that DPC-derived exosomes (DPC-Exos) promote hair follicle stem cell proliferation through the Wnt3a/β-Catenin pathway, further underscoring the pivotal role of this signaling cascade in hair follicle regeneration [59,60].

Although TGF-β/BMP, Shh, Notch, and ERK pathways also play roles in hair follicle regulation, their mechanisms are more complex. For example, TGF-β can both promote hair follicle growth and induce the transition to the telogen phase, while the role of Shh in androgenetic alopecia (AGA) remains unclear. Additionally, Notch and ERK primarily regulate DPC status rather than directly mediating hair follicle cycling [[61], [62], [63]]. Given the fundamental role of Wnt/β-Catenin signaling in hair follicle growth and its direct involvement in PRP-Exos-induced regeneration, this study prioritizes its investigation. Future studies will further explore whether PRP-Exos also modulates the TGF-β/BMP, Shh, Notch, and ERK pathways and elucidate their potential interactions with Wnt/β-Catenin signaling to comprehensively uncover the molecular mechanisms underlying PRP-Exos-mediated hair follicle regeneration.

5. Conclusion

In summary, PRP-Exos exhibit substantial potential in intercellular communication and regulation. By thoroughly exploring the mechanisms and effects of PRP-Exos in treating AGA, this research paves the way for developing novel insights and methods for hair loss treatment, providing patients with additional therapeutic options and hope. Future research will focus on investigating the safety and efficacy of PRP-Exos in clinical applications, further elucidating their specific mechanisms in hair regeneration.

Informed consent

Written informed consent have been provided by the patients and their legal guardians. They have also consented to the publication of their case details.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

IRB approval status

Reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (Approval Number: 2023-SR-354).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Changpei Lu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing-Original Draft. Yunbu Ding: Investigation, Data Curation, rewriting. Rongshuang Zhang: Date Curation, Investigation and resources, rewriting. Min Zhao: Resources, supervision. Yimei Du: Investigation and resources. Lingbo Bi: Modify tables and Review. Chaofan Wang: date collection and analysis. Qiaofang Wu: Software, Validation. Haixia Jing (Corresponding Author): Resources, rewriting, Supervision. Weixin Fan (Corresponding Author): Funding Acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing.

Funding sources

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81972954). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of the Japanese Society for Regenerative Medicine.

Contributor Information

Haixia Jing, Email: jinghaixia1210@163.com.

Weixin Fan, Email: hairmanfwx@163.com.

References

- 1.Lolli F, Pallotti F, Rossi A, Fortuna MC, Caro G, Lenzi A., et al. Androgenetic alopecia: a review. Endocrine. 2017 Jul;57(1):9–17. doi: 10.1007/s12020-017-1280-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams D.J., Timothy G.B., Dirk M.E. Andrew's diseases of the skin: clinical dermatology. Elsevier Inc; Philadelphia: 2011. Disorders of skin appendages; pp. 741–747. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elsaie L.T., Elshahid A.R., Hasan H.M., Soultan F.A.Z.M., Jafferany M., Elsaie M.L. Cross sectional quality of life assessment in patients with androgenetic alopecia. Dermatol Ther. 2020 Jul;33(4) doi: 10.1111/dth.13799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aukerman E.L., Jafferany M. The psychological consequences of androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023 Jan;22(1):89–95. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inui S., Itami S. Molecular basis of androgenetic alopecia: from androgen to paracrine mediators through dermal papilla. J Dermatol Sci. 2011 Jan;61(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stenn K.S., Paus R. Controls of hair follicle cycling. Physiol Rev. 2001 Jan;81(1):449–494. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paus R., Cotsarelis G. The biology of hair follicles. N Engl J Med. 1999 Aug 12;341(7):491–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908123410706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gentile P., Garcovich S. Systematic review of platelet-rich plasma use in androgenetic alopecia compared with Minoxidil®, Finasteride®, and adult stem cell-based therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Apr 13;21(8):2702. doi: 10.3390/ijms21082702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devjani S., Ezemma O., Kelley K.J., Stratton E., Senna M. Androgenetic alopecia: therapy update. Drugs. 2023 Jun;83(8):701–715. doi: 10.1007/s40265-023-01880-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta A.K., Bamimore M.A., Foley K.A. Efficacy of non-surgical treatments for androgenetic alopecia in men and women: a systematic review with network meta-analyses, and an assessment of evidence quality. J Dermatol Treat. 2022 Feb;33(1):62–72. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1749547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mittelbrunn M., Sánchez-Madrid F. Intercellular communication: diverse structures for exchange of genetic information. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012 Apr 18;13(5):328–335. doi: 10.1038/nrm3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalluri R., LeBleu V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020 Feb 7;367(6478) doi: 10.1126/science.aau6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehryab F., Rabbani S., Shahhosseini S., Shekari F., Fatahi Y., Baharvand H., et al. Exosomes as a next-generation drug delivery system: an update on drug loading approaches, characterization, and clinical application challenges. Acta Biomater. 2020 Sep 1;113:42–62. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X., He X., Wang J., Wang D., Cong P., Zhu A., et al. The regulation of exosome-derived miRNA on heterogeneity of macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques. Front Immunol. 2020 Sep 10;11:2175. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foo J.B., Looi Q.H., How C.W., Lee S.H., Al-Masawa M.E., Chong P.P., et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes and microRNAs in cartilage regeneration: biogenesis, efficacy, miRNA enrichment and delivery. Pharmaceuticals. 2021 Oct 28;14(11):1093. doi: 10.3390/ph14111093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rashed M.H., Bayraktar E., Helal G.K., Abd-Ellah M.F., Amero P., Chavez-Reyes A., et al. Exosomes: from garbage bins to promising therapeutic targets. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Mar 2;18(3):538. doi: 10.3390/ijms18030538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang M., Wang C., Chen M., Xi Y., Cheng W., Mao C., et al. Efficient angiogenesis-based diabetic wound healing/skin reconstruction through bioactive antibacterial adhesive ultraviolet shielding nanodressing with exosome release. ACS Nano. 2019 Sep 24;13(9):10279–10293. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b03656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li D., Wu N. Mechanism and application of exosomes in the wound healing process in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022 May;187 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2022.109882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan R., Dai X., Li Y., Li C., Liu L. Exosomes from miR-29a-modified adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells reduce excessive scar formation by inhibiting TGF-β2/Smad3 signaling. Mol Med Rep. 2021 Nov;24(5):758. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2021.12398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim S.R., Zou X., Tang H., Puranik A.S., Abumoawad A.M., Zhu X.Y., et al. Increased cellular senescence in the murine and human stenotic kidney: effect of mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2021 Feb;236(2):1332–1344. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boo Y.C. Metabolic basis and clinical evidence for skin lightning effects of thiol compounds. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022 Mar 4;11(3):503. doi: 10.3390/antiox11030503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kost Y., Muskat A., Mhaimeed N., Nazarian R.S., Kobets K. Exosome therapy in hair regeneration: a literature review of the evidence, challenges, and future opportunities. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Aug;21(8):3226–3231. doi: 10.1111/jocd.15008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y., Su J., Ma K., Li H., Fu X., Zhang C. Photobiomodulation promotes hair regeneration in injured skin by enhancing migration and exosome secretion of dermal papilla cells. Wound Repair Regen. 2022 Mar;30(2):245–257. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin M.Y., Lin C.S., Hu S., Chung W.H. Progress in the use of platelet-rich plasma in aesthetic and medical dermatology. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020 Aug;13(8):28–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebrahimi Z., Alimohamadi Y., Janani M., Hejazi P., Kamali M., Goodarzi A. Platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of scars, to suggest or not to suggest? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2022 Oct;16(10):875–899. doi: 10.1002/term.3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pixley J.N., Cook M.K., Singh R., Larrondo J., McMichael A.J. A comprehensive review of platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of dermatologic disorders. J Dermatol Treat. 2023 Dec;34(1) doi: 10.1080/09546634.2022.2142035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X., Ji Y., Zhou M., Zhou X., Xie Y., Zeng X., et al. Platelet-rich plasma for androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Cutan Med Surg. 2023 Sep-Oct;27(5):504–508. doi: 10.1177/12034754231191461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cruciani M., Masiello F., Pati I., Marano G., Pupella S., De Angelis V. Platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of alopecia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Transfus. 2023 Jan;21(1):24–36. doi: 10.2450/2021.0216-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stevens J., Khetarpal S. Platelet-rich plasma for androgenetic alopecia: a review of the literature and proposed treatment protocol. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018 Sep 21;5(1):46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta A.K., Cole J., Deutsch D.P., Everts P.A., Niedbalski R.P., Panchaprateep R., et al. Platelet-rich plasma as a treatment for androgenetic alopecia. Dermatol Surg. 2019 Oct;45(10):1262–1273. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Brien K., Breyne K., Ughetto S., Laurent L.C., Breakefield X.O. RNA delivery by extracellular vesicles in mammalian cells and its applications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020 Oct;21(10):585–606. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0251-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shin H.S., Woo H.M., Kang B.J. Optimisation of a double-centrifugation method for preparation of canine platelet-rich plasma. BMC Vet Res. 2017 Jun 26;13(1):198. doi: 10.1186/s12917-017-1123-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Théry C., Amigorena S., Raposo G., Clayton A. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2006;Chapter 3:Unit 3.22. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb0322s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rikkert L.G., Nieuwland R., Terstappen L.W.M.M., Coumans F.A.W. Quality of extracellular vesicle images by transmission electron microscopy is operator and protocol dependent. J Extracell Vesicles. 2019 Jan 9;8(1) doi: 10.1080/20013078.2018.1555419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andreasen E. Cyclic changes in the skin of the mouse. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1953;32(1):157–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1953.tb00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jing J., Wu X.J., Li Y.L., Cai S.Q., Zheng M., Lu Z.F. Expression of decorin throughout the murine hair follicle cycle: hair cycle dependence and anagen phase prolongation. Exp Dermatol. 2014 Jul;23(7):486–491. doi: 10.1111/exd.12441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Müller-Röver S., Handjiski B., van der Veen C., Eichmüller S., Foitzik K., McKay I.A., et al. A comprehensive guide for the accurate classification of murine hair follicles in distinct hair cycle stages. J Invest Dermatol. 2001 Jul;117(1):3–15. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fulton R. Getting a grip on Ki-67. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2021 Feb 1;29(2):83–85. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kloepper J.E., Sugawara K., Al-Nuaimi Y., Gáspár E., van Beek N., Paus R. Methods in hair research: how to objectively distinguish between anagen and catagen in human hair follicle organ culture. Exp Dermatol. 2010 Mar;19(3):305–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malkin E.Z., Bratman S.V. Bioactive DNA from extracellular vesicles and particles. Cell Death Dis. 2020 Jul 27;11(7):584. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-02803-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo X., Tan W., Wang C. The emerging roles of exosomal circRNAs in diseases. Clin Transl Oncol. 2021 Jun;23(6):1020–1033. doi: 10.1007/s12094-020-02485-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiong M., Zhang Q., Hu W., Zhao C., Lv W., Yi Y., et al. The novel mechanisms and applications of exosomes in dermatology and cutaneous medical aesthetics. Pharmacol Res. 2021 Apr;166 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gangadaran P., Ahn B.C. Extracellular vesicle- and extracellular vesicle mimetics-based drug delivery systems: new perspectives, challenges, and clinical developments. Pharmaceutics. 2020 May 11;12(5):442. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12050442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee J.Y., Kim H.S. Extracellular vesicles in regenerative medicine: potentials and challenges. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2021 Aug;18(4):479–484. doi: 10.1007/s13770-021-00365-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oh E.J., Gangadaran P., Rajendran R.L., Kim H.M., Oh J.M., Choi K.Y., et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from fibroblasts promote wound healing by optimizing fibroblast and endothelial cellular functions. Stem Cells. 2021 Mar;39(3):266–279. doi: 10.1002/stem.3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo S.C., Tao S.C., Yin W.J., Qi X., Yuan T., Zhang C.Q. Exosomes derived from platelet-rich plasma promote the re-epithelization of chronic cutaneous wounds via activation of YAP in a diabetic rat model. Theranostics. 2017 Jan 1;7(1):81–96. doi: 10.7150/thno.16803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tao S.C., Yuan T., Rui B.Y., Zhu Z.Z., Guo S.C., Zhang C.Q. Exosomes derived from human platelet-rich plasma prevent apoptosis induced by glucocorticoid-associated endoplasmic reticulum stress in rat osteonecrosis of the femoral head via the Akt/Bad/Bcl-2 signal pathway. Theranostics. 2017 Jan 15;7(3):733–750. doi: 10.7150/thno.17450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jere SW, Abrahamse H, Houreld NN. Interaction of the AKT and β-catenin signalling pathways and the influence of photobiomodulation on cellular signalling proteins in diabetic wound healing. J Biomed Sci. 2023 Sep 21;30(1):81. doi: 10.1186/s12929-023-00974-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Torreggiani E., Perut F., Roncuzzi L., Zini N., Baglìo S.R., Baldini N. Exosomes: novel effectors of human platelet lysate activity. Eur Cell Mater. 2014 Sep 22;28:137–151. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v028a11. discussion 151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burger D., Viñas J.L., Akbari S., Dehak H., Knoll W., Gutsol A., et al. Human endothelial colony-forming cells protect against acute kidney injury: role of exosomes. Am J Pathol. 2015 Aug;185(8):2309–2323. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xin H., Li Y., Chopp M. Exosomes/miRNAs as mediating cell-based therapy of stroke. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014 Nov 10;8:377. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rajendran R.L., Gangadaran P., Kwack M.H., Oh J.M., Hong C.M., Sung Y.K., et al. Human fibroblast-derived extracellular vesicles promote hair growth in cultured human hair follicles. FEBS Lett. 2021 Apr;595(7):942–953. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.14050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen Y., Huang J., Chen R., Yang L., Wang J., Liu B., et al. Sustained release of dermal papilla-derived extracellular vesicles from injectable microgel promotes hair growth. Theranostics. 2020 Jan 1;10(3):1454–1478. doi: 10.7150/thno.39566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang X., Cao C., Liang Y., Han L., Tu B., Yu M., et al. Adipose-derived stem cell exosomes antagonize the inhibitory effect of dihydrotestosterone on hair follicle growth by activating Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Stem Cell Int. 2023 Sep 27;2023 doi: 10.1155/2023/5548112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kishimoto J., Burgeson R.E., Morgan B.A. Wnt signaling maintains the hair-inducing activity of the dermal papilla. Genes Dev. 2000 May 15;14(10):1181–1185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006 Nov 3;127(3):469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jing J., Wu X.J., Li Y.L., Cai S.Q., Zheng M., Lu Z.F. Expression of decorin throughout the murine hair follicle cycle: hair cycle dependence and anagen phase prolongation. Exp Dermatol. 2014 Jul;23(7):486–491. doi: 10.1111/exd.12441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aktas H., Alan S., Türkoglu E.B., Sevik Ö. Could topical minoxidil cause non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy? J Clin Diagn Res. 2016 Aug;10(8):WD01–WD02. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/19679.8250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vasserot A.P., Geyfman M., Poloso N.J. Androgenetic alopecia: combing the hair follicle signaling pathways for new therapeutic targets and more effective treatment options. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2019 Sep;23(9):755–771. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2019.1659779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li J., Zhao B., Dai Y., Zhang X., Chen Y., Wu X. Exosomes derived from dermal papilla cells mediate hair follicle stem cell proliferation through the Wnt3a/β-catenin signaling pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022 Nov 7;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/9042345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee J., Tumbar T. Hairy tale of signaling in hair follicle development and cycling. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012 Oct;23(8):906–916. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hsu Y.C., Pasolli H.A., Fuchs E. Dynamics between stem cells, niche, and progeny in the hair follicle. Cell. 2011 Jan 7;144(1):92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang B., Hsu Y.C. Emerging roles of transit-amplifying cells in tissue regeneration and cancer. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2017 Sep;6(5) doi: 10.1002/wdev.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.