Abstract

Although a single nucleotide polymorphism for N-acetyltransferase 10 (NAT10) has been identified in patients with early-onset stroke, the role of NAT10 in ischemic injury and the related underlying mechanisms remains elusive. Here, we provide evidence that NAT10, the only known RNA N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) modification “writer”, is increased in the damaged cortex of patients with acute ischemic stroke and the peri-infarct cortex of mice subjected to photothrombotic (PT) stroke. Pharmacological inhibition of NAT10 with remodelin on Days 3–7 post-stroke or astrocytic depletion of NAT10 via targeted virus attenuates ischemia-induced infarction and improves functional recovery in PT mice. Mechanistically, NAT10 enhances ac4C acetylation of the inflammatory cytokine tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (Timp1) mRNA transcript, which increases TIMP1 expression and results in the accumulation of microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) and progression of astrocyte autophagy. These findings demonstrate that NAT10 regulates astrocyte autophagy by targeting Timp1 ac4C after stroke. This study highlights the critical role of ac4C in the regulation of astrocyte autophagy and proposes a promising strategy to improve post-stroke outcomes via NAT10 inhibition.

Key words: Ischemic stroke, ac4C, NAT10, Timp1, Neuroprotection, Functional recovery, Astrocyte, Autophagy

Graphical abstract

NAT10 regulates astrocyte autophagy by catalyzing Timp1 mRNA acetylation and engages in functional recovery after ischemic stroke.

1. Introduction

Ischemic stroke, now classified as a neurological disease, is the main cause of permanent, disabling motor and neurophysiological deficits in adults worldwide1,2. To date, there are few therapeutic agents available to enhance stroke recovery. Intravenous administration of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator to break up blood clots is the most frequently adopted treatment. Still, such thrombolytic therapy has a narrow therapeutic window as well as some side effects, limiting its usefulness3,4. Thus, how to repair damaged brain tissue or extend the therapeutic time window of treatment remains an urgent clinical question.

The pathophysiology of ischemic stroke is very complex, involving a cascade of events initiated by the lack of blood supply resulting from a blocked blood vessel5. A key element throughout this process is autophagy in the peri-infarct region. Autophagy regulates multiple physiological functions in cells and has been extensively studied in multiple cell types after stroke, particularly astrocytes6, 7, 8. Astrocytes are the most widely distributed glial cells in the mammalian brain and play many important roles in maintaining normal brain function, including supporting and nourishing neurons, regulating ionic concentrations, promoting the integrity of the blood–brain barrier, and so on9, 10, 11. After ischemic stroke, autophagy-regulated astrocytes become reactive, exacerbating inflammatory reactions and neuronal tissue damage in the peri-infarct region12. Recent studies demonstrate that inhibition of autophagic astrocytes correlates with decreased infarct size and treatments capable of decreasing infarct size are often accompanied by attenuated astrocyte autophagy13, 14, 15. Therefore, careful manipulation of the specific pathways regulating astrocyte autophagy may be a valid therapeutic approach for stroke.

Epigenetic modifications to mRNA play a vital role in central nervous system disorders. N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) was originally characterized in eukaryotic transfer RNAs and 18S ribosomal RNA and functions to increase the fidelity of protein translation16. Recently, ac4C has been reported to be active at mRNA wobble sites, maintaining mRNA stability and promoting translation efficiency17,18. N-Acetyltransferase 10 (NAT10) is the only known “writer” enzyme for catalysis of ac4C production in mammals and is linked to the biogenesis of small ribosomal subunits16. NAT10 participates in a diverse array of disorders—such as neuropathic pain, cancer, and aging—by regulating ac4C modification of mRNA19, 20, 21. Analysis of clinical ischemic stroke data indicates that NAT10 in exosomes derived from peripheral blood exhibits single nucleotide polymorphism22, suggesting that it may be a genetic risk variant for ischemic stroke outcomes. However, it remains to be determined whether NAT10 is involved in the regulation of functional recovery after stroke through modulation of ac4C.

In the present study, we show that NAT10 regulates astrocyte autophagy after ischemia injury: NAT10 directly catalyzes ac4C acetylation of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (Timp1) mRNA, leading to upregulation of TIMP1 and an increase in TIMP1-dependent activation of autophagy. Our study reveals that NAT10-mediated RNA ac4C modification contributes to astrocyte autophagy in ischemic stroke. Thus, NAT10 may be an efficient potential target for attenuating infarction and promoting functional recovery after ischemic injury.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethics statement

The human experiments were approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University (approval No. XYFY2023-KL125-01). All mouse experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Xuzhou Medical University (approval ID 2022075038).

2.2. Study population

This was a retrospective case–control study, and participants or their legally authorized representatives provided written informed consent to participate in the study. With aggravating cerebral edema or occurring brain herniation, craniotomy, and decompressive hemicraniectomy were performed to maintain the patient's vital signs, and some patients have necrotic brain tissue removed. The necrotic brain tissues were recruited from the Emergency Department or Neurology Department of the Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University. The non-stroke relative normal controls with brain cancer or massive bleeding were recruited from the Emergency Department or Neurosurgery Department of the Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University. The enrollment period was from May 2023 to January 2024. Abandoned damaged cortex samples were collected immediately upon removal from the patients or controls during surgery, then pre-treated with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further processing. The diagnosis of ischemic stroke was based on clinical presentation in combination with the identification of a lesion via diffusion-weighted imaging, a form of magnetic resonance imaging, or the identification of a new lesion on a delayed computed tomography scan. National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale scores were assessed by a professional neurologist. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the samples are provided in Supporting Information Table S1.

2.3. Animals

We used male mice in our experiments to eliminate variations due to female physiological cycles and to minimize the factors that might influence the results. Adult male C57BL/6J mice (24.0–26.0 g, 8–10 weeks old) were obtained from the Animal Science Center of Xuzhou Medical University. Mice were housed in rooms with a temperature of 25 ± 1 °C, humidity 50%–60%, and a 12 h:12 h light: dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Xuzhou Medical University and performed according to the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments guidelines Guidelines. The sample sizes required for the animal study were calculated based on results from previous experiments and are similar to those generally used in the field. A total of 344 mice were included in this study, and 20 mice were excluded due to death (n = 14) or failed stroke induction (n = 6).

2.4. Photothrombotic (PT) stroke model in mice

As previously described23, focal cortical ischemia was induced in mice by photothrombosis of cortical microvessels. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane (26675-46-7, Keyuanpharm, Shandong, China) and placed on a homeothermic blanket to avoid hypothermia. Rectal temperature was monitored during surgery. The skull surface was exposed and kept dry. Rose Bengal (30 mg/kg, i.v., 330000, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was administered via the tail vein. Light (12,000 lux illumination) was delivered to the brain for 5 min through the intact skull via an opaque template with a 2-mm diameter opening positioned 1.5 mm lateral from bregma. When illuminated in this manner, Rose Bengal generates singlet oxygen, damaging and occluding the vascular endothelium, leading to focal cortical stroke. Sham mice received an equal dose of Rose Bengal and had their skull surface exposed but did not receive the illumination.

2.5. Mouse behavioral tests

The mice were coded and randomly divided into experimental or control groups. Behavioral tests were carried out by an independent, blinded investigator and the data were analyzed by a separate investigator.

An elevated grid area of 32 cm × 20 cm made of 12-mm square wire mesh was used for the grid-walking task24. Mice were placed individually and allowed to move freely on the wire grid until a minimum of 100 steps were recorded for the left forelimb. Two cases were considered faults: (i) the foot was not supported by the grid but went through the grid hole; (ii) the mouse wrist was at the level of the grid when resting. The ratio of foot faults was calculated as Eq. (1):

| Percentage of foot faults = The frequency of foot faults/(Frequency of foot faults + Frequency of non-faults) × 100 | (1) |

A plastic cylinder (15 cm tall, 10 cm diameter) was used for the cylinder test. This test encourages the use of the forelimbs for vertical wall exploration/press25. Mice were placed inside the cylinder and recorded for 5 min. The ratio was calculated as Eq. (2):

| The ratio = (Frequency of right front paw − Frequency of left front paw)/(Frequency of right front paw + Frequency of left front paw + Frequency of both front paws) | (2) |

Two equal small pieces of adhesive-backed paper dots (25 mm2) were used as bilateral tactile stimuli in the adhesive-removal somatosensory test26. Paper-dot pieces occupied the distal-radial region on the wrist of each forelimb. The time for mice to remove each piece from the forelimb was recorded. The result was calculated as the time for the left paw – the time for the right paw, with time measured in seconds.

2.6. Reagents

Remodelin (1622921-15-6), a specific inhibitor of NAT10, was purchased from TopScience, Shanghai, China. Remodelin was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and diluted in sterile Tween 80 and 45% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin solution. The final formulation was 20% DMSO, 65% (45% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin solution), and 15% Tween 80 as a previous study27. The adenoviral vector carrying mRFP-GFP-LC3 was purchased from HanBio (HB-AP2100001, Shanghai, China). AAV-gfaABC1D-shNat10, AAV-gfaABC1D-shTimp1, and AAV-gfaABC1D-shAtg5 were constructed and packaged by HanBio.

2.7. CRISPR vector specifically targeting the ac4C site in Timp1 CDS

The dCasRx and NAT10 fusion vector construction was conducted as previously described with a few modifications28,29. Briefly, full-length Nat10 amplified from mouse cDNA was ligated into the BamHI-treated EF1a-dCasRx-2A-EGFP vector with a ClonExpress II One Step Cloning kit (C112, Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Lentivirus gRNA including gRNA-511 (targeting 511 to 530 of the Timp1 CDS), gRNA-612 (targeting 612 to 631 of the Timp1 CDS), or negative control gRNA were constructed through ligating to pLH-sgRNA. The lentivirus package and titer identification were performed as described previously29,30. Lentivirus-dCasRx-Nat10 and Lenti-gRNA were co-microinjected into the mouse cerebral cortex and then used in experiments after validation of efficiency. The forward and reverse oligos are listed in Supporting Information Table S2.

2.8. Stereotaxic injection

Eight-week-old C57BL/6J mice were microinjected with the described virus. The stereotaxic injection site was as follows (from bregma): anteroposterior, 0 mm; mediolateral, 1.5 mm; dorsoventral, 1.3 mm. After injection, the needle was left in situ for 10 min to allow for the distribution of the virus.

2.9. Nissl staining and infarction measurement

Mouse brains were cut into 50-μm thick sections. Infarct volume was determined via Nissl staining according to the manufacturer's protocol (C0117, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Infarct volume was quantified in ImageJ as Eq. (3):

| Infarction volume (mm3) = Infarct area of one section (mm2) × Section thickness × Section interval (3) | (3) |

Infarct area of one section (mm2) was calculated as the size of the contralateral hemisphere minus that of the ipsilateral non-infarct hemisphere.

2.10. Triphenyl tetrazolium chloride staining and infarction measurement

The infarction was examined at 6 h, 24 h, Days 5 and 7 after PT surgery. Each brain was coronally sectioned into five 1-mm slices. Then the slices were incubated with 2% triphenyltetrazolium chloride (T8877, Sigma–Aldrich) at 37 °C for 5 min to display the size and extent of infarct volumes. Images were analyzed using ImageJ 2.0. The measurement for infarction was similar to Nissl staining.

2.11. Ribosome nascent-chain complex sequencing (RNC-seq) analysis

Peri-infarct cortex from PT stroke mice was pre-treated with 100 μg/mL cycloheximide for 15 min, followed by 1 mL of lysis buffer [1% Triton X-100 in ribosome buffer (RB buffer): 20 mmol/L HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4), 15 mmol/L MgCl2, 200 mmol/L KCl, 100 μg/mL cycloheximide, and 2 mmol/L dithiothreitol] with 1% PMSF and 2% 400U RNase inhibitor (R301-01, Vazyme). After incubating for 30 min, lysates were scraped and transferred to pre-chilled 1.5-mL tubes. Debris was removed by centrifuging at 12,000 rpm (Beckman, Optima XE-90, Brea, CA, USA) for 10 min at 4 °C. 100-μL supernatants were used as the input for total RNA, and the remainder was transferred to the surface of 9 mL of sucrose buffer (30% sucrose in RB buffer). Ribosome nascent-chain complexes (RNCs) were pelleted after ultra-centrifugation at 36,000 rpm (Beckman, Optima XE-90) for 4 h at 4 °C. RNC-RNA and total RNA were collected and sequenced in MajorBio (Shanghai, China). RNC-seq reads were aligned to the mouse genome (GRCh37/hg19) via Hisat2 (2.0.4) software. Transcript abundance was quantified as fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM). Differentially expressed RNC-mRNAs were determined by DESeq231.

2.12. ac4C dot blot

As described previously17,29, for ac4C dot-blot analysis, 500 ng of RNA was denatured at 75 °C for 5 min, then immediately placed on ice for 1 min followed by loading onto HybondN1 membrane and then crosslinked with UV254 for 10 min. After blocking with 5% nonfat milk for 2 h at room temperature, the membrane was incubated with a specific antibody for ac4C (1:1000; A18806, ABclonal, Wuhan, China) at 4 °C overnight. After washing 3 times with 0.05% Tween 20 PBS, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit IgG antibody for 2 h at room temperature. The signal was visualized by ECL (P0018S, Beyotime). Equal total RNA loading was examined with 0.2% methylene blue staining of the membrane. The intensity of each dot was normalized to the total RNA.

2.13. Polyribosome fractionation assay

The polyribosome fractionation assay was conducted as described previously, with few modifications32,33. Briefly, 5 gradient sucrose solutions (7%, 17%, 27%, 37%, and 47% in Tris–HCl) were gently added to a 10.4 mL tube (355603, Beckman), using 2 mL for each gradient solution and with a progressively decreasing gradient from the bottom of the tube. After washing 3 times with ice-cold 1 × PBS, astrocytes were digested with freshly prepared lysis buffer. After centrifugation, 400 mL of supernatant was added to the tube and centrifuged again using Beckman Optima XE-90 (36,000 rpm for 2 h at 4 °C with max break), and then the solutions in the tube were split into 12 equal fractions. For each fraction, the total RNA was extracted with 1.5 mL TRIzol (R401-01, Vazyme) for Timp1 mRNA qPCR.

2.14. Cell culture

Primary astrocyte cultures were obtained from newborn C57BL/6J mice within 3 days of birth, according to a previous study34. Briefly, after removal of visible blood vessels and meninges, mouse brain tissue was dissected and incubated in trypsin–EDTA (25200056, Gibco, New York, NY, USA) for 10 min; next, astrocytes were dissociated and plated into a poly-d-lysine-precoated cell culture flask (25 cm2) loaded with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, 10-013-CVR, Corning, New York, NY, USA) supplemented with dialyzed fetal bovine serum (10% v/v, 26400044, Gibco) and penicillin-streptomycin (1% v/v, P4333, Sigma–Aldrich). Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2). The medium was changed every 3 days.

Primary neurons of the cerebral cortex were isolated from C57BL/6J mouse embryos (E15–E16) as described previously25. Briefly, mouse cortex from embryos was dissected and incubated in trypsin–EDTA for 10 min; then neurons were dissociated and plated at 1.5 × 104 cells per well in neurobasal medium (21103049, Gibco) supplemented with 0.5% GlutaMAX supplement (35050061, Gibco) and 2% B27 supplement (17504044, Gibco). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in humidified air containing 5% CO2. The medium was changed every 3 days.

2.15. Oxygen glucose deprivation (OGD) treatment

OGD treatment was performed as previously described25,35. Briefly, cells were cultured with deoxygenated DMEM without glucose (11966-025, Gibco) in an incubator with premixed gas (95% N2 and 5% CO2) for 6 h. The control group was cultured with normal DMEM for the same incubation time.

2.16. Lentiviral transduction of astrocytes

After cultured for 24 h in plates, astrocytes were transduced with lentivirus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. Infection was performed by directly adding lentivirus to the growth medium. After incubation with lentivirus for 2 days, the astrocytes were subjected to OGD treatment.

2.17. Immunostaining and image analysis of sections

Sections were cut into 30-μm coronal slices, and then incubated with 0.3% Triton X-100 in 1 × PBS for 15 min and blocked with 10% normal goat serum (ZLI-9056, ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China) in 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation with a rabbit anti-NAT10 antibody (1:300, 17721-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), mouse anti-NeuN antibody (1:200, ab104224, Abcam, Cambridge, Britain), mouse anti-GFAP antibody (1:200, G3893, Sigma–Aldrich), goat anti-Iba-1 antibody (1:200, ab5076, Abcam), or rabbit anti-LC3B antibody (1:200, L7543, Sigma–Aldrich), the sections were incubated with the corresponding fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. After a final washing step with PBS, the sections were mounted onto glass slides. Images were captured by confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM, Leica STELLARIS 5, Hesse, Germany).

2.18. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

qPCR was performed according to our previous study with a QuantStudio 7 Flex system29. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (15596026, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). RNAs were reverse transcribed by a HiScript II Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) (R223-01, Vazyme) and quantified with SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Q331-02, Vazyme). β-Actin was used as an internal control. The primers used to amplify mRNA transcripts were synthesized by Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China. The sequences of the primers are listed in Table S2.

2.19. Western blot analysis

Proteins were extracted in RIPA lysis buffer (P0013B, Beyotime). After separation on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels (10% and 12%), the proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes with electrophoretic equipment and incubated overnight at 4 °C with rabbit anti-NAT10 antibody (1:1000), mouse anti-NeuN antibody (1:1000), mouse anti-GFAP antibody (1:1000), rabbit anti-C3 antibody (1:1000, ab200999, Abcam), rabbit anti-p62 antibody (1:1000, 18420-1-AP, Proteintech), rabbit anti-LC3B antibody (1:1000, L7543, Sigma–Aldrich), rabbit anti-TIMP1 antibody (1:1000, 26847-1-AP, Proteintech), rabbit anti-β-tubulin antibody (1:3000, 66240-1-Ig, Proteintech) or mouse anti-β-actin antibody (1:3000, 66009-1-lg, Proteintech). On the second day, membranes were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse/rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:2000, 7076P2/7074P2, Cell Signaling, Boston, MA, USA). Signals were visualized with ECL reagent and detected by a UVITEC System (Q9 Alliance, UVITEC, Cambridge, Britain) image scanner. Quantification of individual protein bands was performed by densitometry in ImageJ 2.0.

2.20. Cell counting kit-8

Neurons were pretreated with remodelin for 1 h, and subjected to OGD for 3 h, then incubated with cell counting kit-8 (HY–K0301, MCE, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) for 2 h and examined the values of OD at 450 nm according to the instructions.

2.21. Statistics

All data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Significance was assessed by a Student's t-test (two-tailed) for comparisons between 2 groups (all data were tested and found to be normally distributed). One-way ANOVAs followed by the Holm–Sidak test were used for the comparison of 3 or more groups. Behavioral data collected at sequential time points were analyzed with two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs, followed by the Holm–Sidak post hoc test. Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism (v8.0). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Patients with acute ischemic stroke and stroke model mice show increased NAT10 expression

NAT10 has a single nucleotide polymorphism in stroke, as characterized by gene burden testing of peripheral blood-derived exosomes collected from patients with early-onset stroke22. To investigate the potential involvement of NAT10 in functional recovery during ischemic stroke, we collected necrotic cortex from patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) and non-stroke controls; detailed information was included in Table S1. Western blot analysis demonstrated higher NAT10 expression in AIS patients than in control subjects (Fig. 1A). We further assessed the expression of NAT10 via immunofluorescent staining of brain-tissue sections from patients and control subjects. We found increased NAT10 staining intensity in sections from patients with ischemic stroke (Fig. 1B and C).

Figure 1.

Upregulation of NAT10 in patients with acute ischemic stroke and mice subjected to photothrombotic stroke. (A) Western blot analysis of NAT10 expression in the cortex of patients with AIS and the corresponding controls. n = 4 individuals/group. ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. Control, Student's t-test. (B) Representative immunostaining of NAT10 in the cortex of a patient with AIS and a corresponding control. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Analysis of NAT10 immunostaining in the cortex of AIS patients and controls. n = 4 individuals/group. ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. Control, Student's t-test. (D) Western blot analysis of NAT10 expression in the peri-infarct cortex of mice subjected to PT stroke. The damaged cortex was collected on Days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 14 after the PT stroke induction. n = 4 animals/group. ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the Sham group, one-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. (E) Confocal image showing NAT10 immunostaining in the peri-infarct cortex on Day 5 after the PT stroke. Scale bar, 50 μm. All data are represented as the mean ± SEM.

In the mouse photothrombotic (PT) stroke model, NAT10 was increased in the peri-infarct cortex on Days 5 and 7 (Fig. 1D). Immunostaining was performed on Day 5 after PT, and an accumulation of NAT10 in the peri-infarct cortex was also observed (Fig. 1E). Moreover, we accessed the infarction at multiple time points, including 6 h, Days 1, 5 and 7 after PT. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S1A and S1B, the infarct volume progressed to the maximum on Day 5. Taken together, these findings from human AIS patients and the murine stroke model suggest that stroke increases the expression of NAT10 in the peri-infarct cortex, and a similar pattern of evolution of infarction after ischemia, indicating that NAT10 may be involved in the pathological processes that occur after stroke.

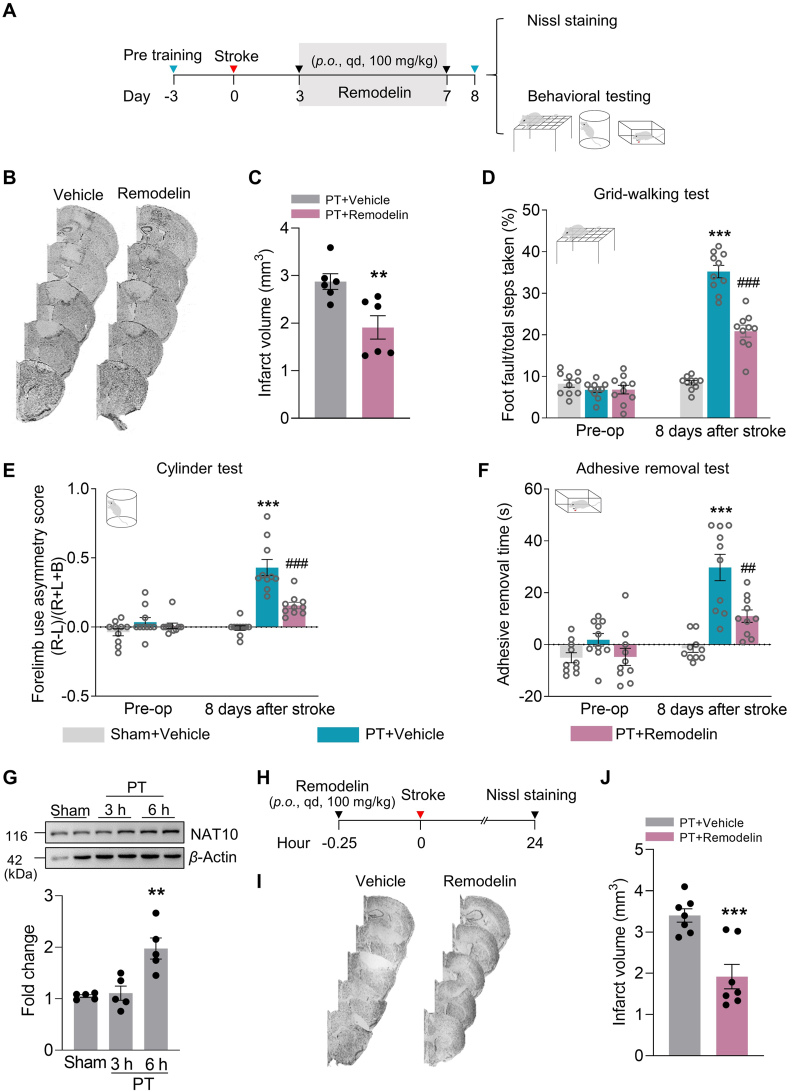

3.2. Pharmacological inhibition of NAT10 reduces the infarction and enhances functional recovery in PT mice

Next, we examined the effect of NAT10 on functional recovery in PT mice. Although the increase in NAT10 on Day 3 after PT did not reach significance, we decided to initiate treatment at this time point since P = 0.0616. Pre-trained male mice were subjected to PT followed by a once daily oral administration of remodelin (an inhibitor targeting NAT10) on Days 3–7 after surgery. Nissl staining and behavioral testing were performed on Day 8 after PT (Fig. 2A). As shown in Fig. 2B and C, Nissl staining shows a marked decrease in infarct volume in the remodelin-administered group compared with the vehicle-administered group. We then assessed the animals’ functional recovery according to our previous study25 and found that compared with the vehicle group, the remodelin group showed improved performance on the grid-walking test (reduced foot faults) on Day 8 after PT surgery (Fig. 2D). Similar results were recorded with the cylinder test: animals injected with remodelin showed lower bias than the vehicle group on Day 8 after PT (Fig. 2E). Similarly, the adhesive removal test also showed a significant therapeutic effect of remodelin (Fig. 2F). Collectively, these results show that inhibition of NAT10 on Days 3–7 after stroke reduced infarction and promoted motor recovery.

Figure 2.

NAT10 inhibition enhances functional recovery in PT mice. (A) Timeline of the experiment. NAT10 was inhibited by administration of remodelin on Days 3–7 after stroke induction; functional studies and tissue collection were conducted on Day 8. (B, C) Representative Nissl-stained sections from PT + Vehicle or PT + Remodelin mice on Day 8 post-stroke. n = 6 animals/group. ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. the PT + Vehicle group, Student's t-test. (D–F) NAT10 inhibition from Day 3 to Day 7 after stroke improved behavioral recovery on Day 8 after stroke, as measured by the grid-walking test (D), the cylinder test of forelimb function (L indicates the left forepaw, R indicates the right forepaw) (E), and the adhesive removal test (F). n = 10 animals/group. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the Sham + Vehicle group, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. the PT + Vehicle group, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. (G) Western blot analysis of NAT10 expression in the peri-infarct cortex. The damaged cortex was collected 3 and 6 h after the PT stroke induction. n = 5 animals/group. ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. Sham, one-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. (H) Timeline of the experiment. NAT10 was inhibited by pretreatment of remodelin at 0.25 h before stroke induction; tissue collection was conducted at 24 h after stroke induction. (I, J) Representative Nissl-stained sections from PT + Vehicle or PT + Remodelin mice at 24 h post-stroke. n = 7 animals/group. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the PT + Vehicle group, Student's t-test. All data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

To comprehensively determine the therapeutic window of NAT10 in ischemic stroke, we also examined the expression of NAT10 at 3 and 6 h after PT. Western blot analysis showed increased NAT10 expression in the peri-infarct zone at 6 h (Fig. 2G). Additionally, pre-inhibition of NAT10 with remodelin reduced the infarct volume, as analyzed by Nissl staining (Fig. 2H–J). Given the consensus that the narrow therapeutic window limits thrombolytic treatments and thus neuroprotection for most stroke patients and that widening the therapeutic window remains a critical need, we used pharmacological inhibition of NAT10 on Days 3–7 after PT in all of the following experiments.

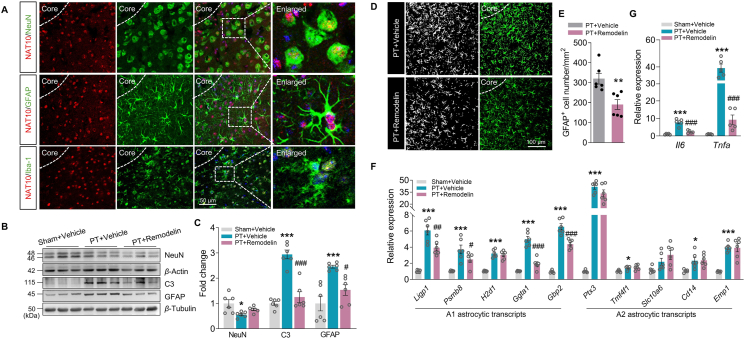

3.3. Pharmacological inhibition of NAT10 weakens post-stroke astrocyte activation in the peri-infarct cortex

Given that modulating NAT10 affects functional outcomes after stroke, we next investigated the cellular mechanism(s) by which these effects of NAT10 are exerted. We used immunofluorescence staining to examine the distribution of NAT10 in multiple types of central nervous system cells, including neurons, astrocytes, and microglia, in the peri-infarct cortex after PT. NAT10 was almost undetectable in microglia but was abundant in neurons and astrocytes (Fig. 3A). Next, we administered remodelin on Days 3–7 after PT surgery and then performed a Western blot. As shown in Fig. 3B and C, there were no significant differences in NeuN (a marker for neurons) between the groups, but remodelin significantly rescued the stroke-induced increase in GFAP (a marker for astrocytes) and complement C3 (a marker for neurotoxic astrocytes). The effect of NAT10 inhibition on astrocytes was further confirmed by immunofluorescent staining: on Day 8 following stroke, remodelin significantly decreased astrocytic reactivity in the peri-infarct cortex compared with the vehicle group (Fig. 3D and E).

Figure 3.

NAT10 inhibition decreases the neurotoxic astrocyte response in the peri-infarct cortex. (A) Colocalization of NeuN, GFAP, or Iba-1 (green) with NAT10 (red) in the peri-infarct cortex of mice. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B, C) Representative immunoblots (B) and a bar graph (C) showing Western blot analyses of NeuN, GFAP, and C3 expression in the peri-infarct cortex of mice on Day 8 after PT under remodelin treatment. n = 6 animals/group. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the Sham + Vehicle group; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 vs. the PT + Vehicle group; one-way ANOVA followed by the Holm–Sidak test. (D, E) Immunoreactivity for astrocytic marker GFAP under different treatment conditions on Day 8 after stroke. The dotted line denoted the infarct border. n = 6 animals/group. ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. PT + Vehicle group, Student's t-test. Scale bar, 100 μm. (F) The effects of NAT10 inhibition on A1 neurotoxic or A2 neuroprotective astrocyte transcripts. Relative expression of specific transcripts was analyzed by qPCR on Day 8 after PT surgery. n = 6 animals/group. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the Sham + Vehicle group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. the PT + Vehicle group; one-way ANOVA followed by the Holm–Sidak test. (G) The effects of NAT10 inhibition on the expression of cytokines in PT stroke mice. n = 5 animals/group. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the Sham + Vehicle group; ###P < 0.001 vs. the PT + Vehicle group; one-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. All data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

Since different astrocytic phenotypes are associated with either cytotoxic or neuroprotective effects, we next examined the effects of NAT10 on stage-specific switching of astrocytic phenotype. As shown in Fig. 3F, PT stroke led to upregulation of A1-astrocyte-specific transcripts (Ligp1, Psmb8, H2d1, Ggta1, and Gbp2) in the peri-infarct zone, and NAT10 inhibition with remodelin resulted in significant downregulation of these A1 transcripts with no change in A2-astrocyte-specific transcripts (Ptx3, Tm4sf1, Slc10a6, Cd14, and Emp1). We further identified the effects of NAT10 inhibition on microglia based on the consensus that microglia are the main immune cells in the brain and are associated with either cytotoxic or neuroprotective effects. We observed that the level of M1 microglia-specific transcripts (Il1b and Nos2), M2a microglia-specific transcripts (Tgfb and Arg1), and M2c microglia-specific transcripts (Il10 and Socs3) were increased in the peri-infarct region on Day 8 in PT mice. NAT10 repression caused downregulation of Il1b and Nos2, clearly indicating a reduced proportion of M1-type cells. Further, NAT10 inhibition partly promoted the cells to M2a phenotypes (i.e., upregulation of Tgfb) (Supporting Information Fig. S2). Furthermore, NAT10 inhibition significantly decreased the levels of Il6 and Tnfa in the peri-infarct region of PT mice compared with vehicle-administered mice (Fig. 3G). These findings indicate that inhibition of NAT10 eased reactive-astrocyte neurotoxicity in the peri-infarct cortex of mice with PT stroke.

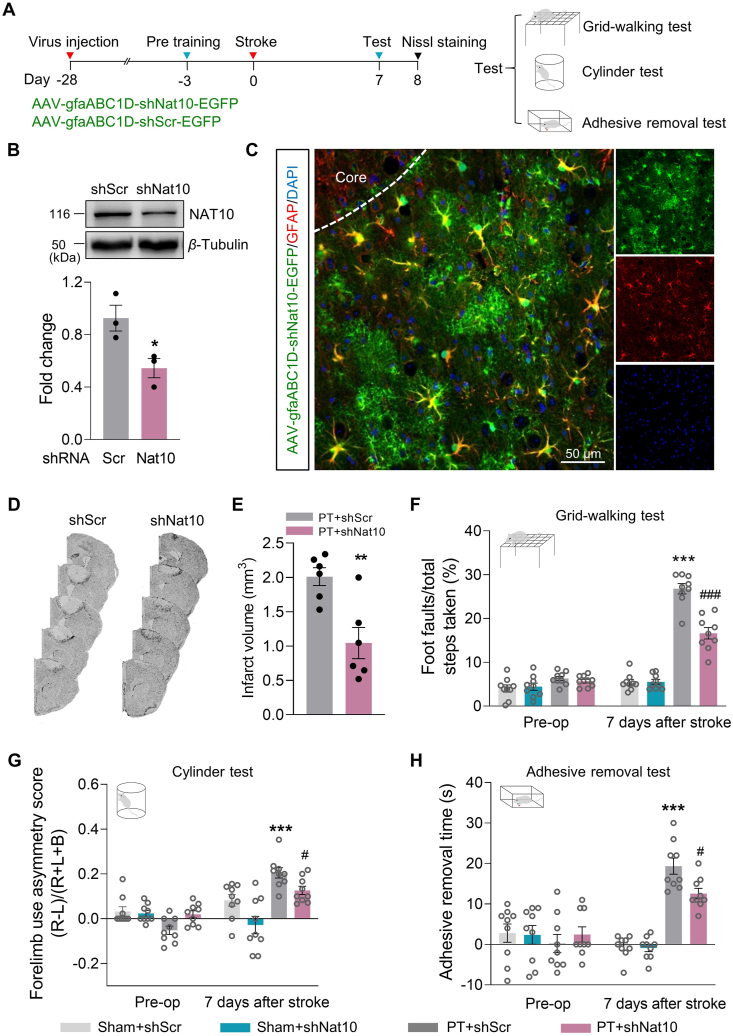

3.4. Astrocyte-targeted NAT10 depletion enhances post-stroke functional improvement

Because inhibiting NAT10 lessened stroke-induced astrocyte reactivity and the proportion of A1 astrocyte transcripts, we next investigated the impact of astrocytic NAT10 on functional recovery after the PT stroke. AAV-gfaABC1D-shNat10 (a virus that specifically reduces expression of NAT10 in astrocytes) or AAV-gfaABC1D-shScr (a viral control) was microinjected into the prospective stroke site 28 days before stroke; functional recovery of mice was tested on Day 7 after stroke followed by Nissl staining, as illustrated in Fig. 4A. The efficacy of AAV transduction was examined by Western blot (Fig. 4B), with specific transduction in astrocytes observed in the peri-infarct region (Fig. 4C and Supporting Information Fig. S3). We then determined the effect of the downregulation of astrocytic NAT10 on the infarct induced by ischemia. As shown in Fig. 4D and E, administration of AAV-gfaABC1D-shNat10 significantly decreased the PT infarct volume compared with AAV-gfaABC1D-shScr. Moreover, pre-treatment with AAV-gfaABC1D-shNat10, but not the control virus, significantly alleviated ischemic functional impairments, as assessed by foot faults in the grid-walking task, forelimb asymmetry scores in the cylinder task, and removal time in the adhesive removal test (Fig. 4F–H).

Figure 4.

Downregulation of NAT10 in astrocytes improves functional recovery in PT mice. (A) Experimental procedure and timeline. The astrocyte-targeting adeno-associated virus (AAV) shRNA-Nat10 or shRNA-Scr was injected into the prospective stroke site in the cortex on Day 28 before stroke. Behavioral performance was examined at the pre-stroke baseline and on Day 7 after stroke followed by Nissl staining. (B) NAT10 expression was measured by Western blot. The cortex was collected on Day 28 after microinjection. n = 3 animals/group. ∗P < 0.05 vs. the shRNA-Scr group, Student's t-test. (C) Representative images of AAV-shRNA-Nat10 (green) infection of astrocytes (red) on Day 8 after stroke. Scale bar, 50 μm. (D, E) Representative Nissl-stained sections from PT + shRNA-Scr or PT + shRNA-Nat10 mice on Day 8 post-stroke. n = 6 animals/group. ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. the PT + shRNA-Scr group, Student's t-test. (F–H) NAT10 inhibition in astrocytes improved behavioral recovery on Day 7 after stroke as measured by the grid-walking test (F), the cylinder test of forelimb function (G), and the adhesive removal test (H). n = 9 animals/group. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the Sham + shRNA-Scr group; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 vs. the PT + shRNA-Scr group; two-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. All data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

Given that NAT10 was highly expressed in neurons (Fig. 3A), we also explored the effects of neuronal NAT10 on ischemic brain injury. LV-hSyn-shNat10 (a lentivirus that specifically reduces expression of NAT10 in neurons) or LV-hSyn-shScr (a lentiviral control) was microinjected into the prospective stroke site 7 days before stroke; infarct volumes of mice were tested on Day 7 after stroke, as illustrated in Supporting Information Fig. S4A. The efficacy of LV transduction was examined by Western blot (Fig. S4B), with specific transduction in neurons observed in the cerebral cortex (Fig. S4C). We next examined the effect of the downregulation of neuronal NAT10 on the infarction. Nissl staining showed no significant difference in infarct size between LV-hSyn-shNat10 and LV-hSyn-shScr (Fig. S4D and S4E). Moreover, our in vitro experiments with cultured primary neurons from mice showed that OGD treatment for 3 h significantly decreased neuronal viability and this decreased phenotype was not rescued by incubation with remodelin (Fig. S4F), indicating that silencing neuronal NAT10 did not show a neuroprotective effect. These pieces of evidence for NAT10 function in astrocytes and neurons indicate that NAT10 depression in astrocytes promotes neuroprotection and functional recovery in PT induction of stroke mice.

3.5. Inhibition of NAT10 decreases the level of ac4C and autophagy

NAT10 has been shown to promote ac4C modification of RNAs and is the only known “writer” for ac4C16; thus, we hypothesized that ischemia may alter the level of ac4C in the peri-infarct zone. We therefore examined the potential effect of NAT10 on ac4C modification of RNA after the PT stroke. Dot-blot results showed that ischemia significantly increased the ac4C levels in the peri-infarct region, and this increase was reversed by pharmacological inhibition of NAT10 (Fig. 5A). Given the known involvement of NAT10 in autophagy during aging21, we next collected tissue from the peri-infarct cortex. Higher level of LC3B-II and lower level of p62 (markers for autophagy) were examined in the peri-infarct region, and NAT10 inhibition markedly ameliorated the changes on Day 8 after PT (Fig. 5B). Immunofluorescence for LC3B in astrocytes in the peri-infarct area further confirmed the influences (Supporting Information Fig. S5A and S5B). Tissue examined at the acute stage after the onset of PT also showed a reduction in LC3B-II expression with remodelin treatment (Supporting Information Fig. S6).

Figure 5.

NAT10 is involved in autophagy via ac4C modification. (A) The effect of NAT10 inhibition on the total ac4C level in PT mice. The total RNA was extracted from the peri-infarct cortex on Day 8 after the PT stroke. n = 6 animals/group. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the Sham + Vehicle group; ##P < 0.01 vs. the PT + Vehicle group; one-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. (B) The effect of NAT10 inhibition on LC3B-II and p62 expression. The protein was extracted from peri-infarct cortex on Day 8 after the PT stroke. n = 6 animals/group. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the Sham + Vehicle group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. the PT + Vehicle group; one-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. (C) Expression of NAT10 in primary mouse astrocyte culture exposed to OGD. The lysis was collected at 3, 6, or 12 h after OGD. n = 3. ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. Con, one-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. (D) The effect of NAT10 inhibition on the total ac4C level in cultured astrocytes. Primary mouse astrocytes were treated with 10-μm remodelin for 1 h before OGD. The total RNA was extracted at 6 h post-OGD induction. n = 3. ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. the Con + Vehicle group; #P < 0.05 vs. the OGD + Vehicle group; two-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple comparisons test. (E) Representative immunoblots of LC3B-II and p62 expression in cultured astrocytes. Primary mouse astrocytes were treated with 10-μm remodelin for 1 h before OGD exposure. LC3B-II and p62 were examined at 6 h post-OGD induction. n = 3. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the Con + Vehicle group; #P < 0.05 vs. the OGD + Vehicle group; two-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. (F, G) Inhibition of NAT10 alleviated autophagic flux after OGD. Primary mouse astrocytes were infected with mRFP-GFP-LC3 adenovirus and exposed to OGD for 6 h. The number of yellow puncta (autophagosomes) and red puncta (autolysosomes) per cell were counted. Data were obtained from 3 independent experiments. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the Con + Vehicle group; ###P < 0.001 vs. the OGD + Vehicle group; two-way ANOVA followed by the Holm–Sidak test. Scale bar, 20 μm. All data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

Next, we sought to examine whether NAT10 affected ac4C or/and autophagy in astrocytes after OGD. First, we used Western blot to examine changes in NAT10 in primary mouse astrocytes at different time points after OGD treatment and observed a time-dependent increase in NAT10 (Fig. 5C). Also, OGD-induced astrocyte autophagy was verified as the increase of LC3B-II and the decrease of p62 in the Supporting Information Fig. S7A and S7B. Dot-blot analysis showed that OGD also led to an increase in ac4C and that this increase was inhibited by remodelin but not by vehicle control (Fig. 5D). Meanwhile, an increase in LC3B-II and decrease in p62 in the OGD group were also rescued by remodelin (Fig. 5E). Similar to the results for LC3B-II of the pharmacological manipulations, transducing cells with Lenti-shRNA-Nat10 significantly inhibited OGD-induced autophagy in primary mouse astrocytes, as determined by Western blot analysis of LC3B-II (Supporting Information Fig. S8A and S8B). Conversely, transfecting primary mouse astrocytes with Lenti-Nat10 to overexpress NAT10 increased the expression of LC3B-II after OGD in primary mouse astrocytes (Fig. S8C and S8D). Together, these results indicate that NAT10 modulated the level of ac4C and LC3B accumulation in vivo and in vitro.

However, increased levels of autophagosomes can signify either an increase in autophagy or a block in downstream lysosomal processing of the autophagosomes. Thus, primary mouse astrocytes were transduced with tandem fluorescent mRFP-GFP-LC3-adenovirus to assess the effect of NAT10 on autophagic flux. GFP fluorescence is quenched by the acidic environment of the lysosome, while RFP fluorescence is relatively stable under acidic conditions. Therefore, yellow puncta, reflecting combined GFP and RFP fluorescence, indicate autophagosomes that have not fused with lysosomes, whereas red puncta (RFP only) indicate autolysosomes. As shown in Fig. 5F and G, OGD treatment of primary mouse astrocytes significantly increased the number of yellow puncta per cell with a concomitant increase in RFP-only puncta. Remodelin-treated cells displayed baseline levels of autophagic flux after OGD, with fewer red puncta, suggesting that remodelin may decrease LC3 expression through a reduction in autophagic flux rather than by blocking lysosomal processing of the autophagosomes.

3.6. NAT10 positively regulates TIMP1 expression in the peri-infarct cortex of PT mice

Having determined that NAT10 inhibition decreased the level of ac4C in the PT stroke model, we next explored downstream genes that may be the targets of acetylation. A previous study showed that ac4C modification improves mRNA translation efficiency17. Thus, we performed ribosome nascent-chain complex sequencing (RNC-Seq) to screen the inactively translated mRNAs in the peri-infarct cortex of remodelin-treated PT mice (Fig. 6A). mRNA bound to ribosome nascent-chain complex (RNC-mRNA) was isolated from the total mRNA (input-mRNA) by centrifugation. The translation efficiency of mRNA was calculated by dividing the FPKM of input-mRNA by the FPKM of RNC-mRNA. We found 1535 transcripts with a significant increase in translation efficiency after PT compared with Sham (fold change ≥2; P < 0.05); of those, 75 transcripts had a significant decrease in translation efficiency with remodelin treatment compared with vehicle (fold change ≤0.5; P < 0.05) (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

NAT10 enhances Timp1 mRNA translation via ac4C modification. (A) Experimental procedure and timeline for RNC-seq experiment. Peri-infarct cortex for RNC-seq was pooled from 8 animals and defined as one sample. There were 3 samples for each group. (B) Venn diagram showing the number of genes with significant changes in expression (up: fold change ≥2, P < 0.05; down: fold change ≤0.5, P < 0.05). (C) Relative expression of Timp1 in the peri-infarct cortex as determined by qPCR. NAT10 was inhibited by remodelin administration on Days 3–7 after stroke and the level of Timp1 was examined on Day 8 after the PT stroke. n = 6 animals/group. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. Sham + Vehicle group, one-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. (D) Representative immunoblots of TIMP1 expression in peri-infarct cortex. NAT10 was inhibited by remodelin administration on Days 3–7 after stroke and the expression of TIMP1 was examined by Western blot on Day 8 after stroke. n = 6 animals/group. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. Sham + Vehicle group; ###P < 0.001 versus PT + Vehicle group; one-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. (E) Polysome assay showing the translation state of Timp1 mRNA in primary mouse astrocytes. The vehicle or remodelin pre-treated astrocytes were subjected to OGD for 6 h. n = 3. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the Con + Vehicle group; ###P < 0.001 vs. the OGD + Vehicle group; two-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. (F) The predicted ac4C motif (CXXCXXCXX, where X represents A, G, C, or U) location in the CDS of Timp1 mRNA. The forward and reverse arrows represented paired qPCR primers. a–c indicated the 3 ac4C motif regions in the Timp1 CDS. F and R indicate the designed PCR primer pairs for amplifying the specific ac4C motifs. (G) Detection of the 3 corresponding ac4C motifs via RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)-PCR using the 3 PCR primer pairs. M indicated marker. (H) The effect of NAT10 upregulation on the ac4C level of Timp1 CDS (c motif sites). Cultured primary mouse astrocytes were transduced with lentivirus expressing Nat10 or the Gfp control for 48 h and the enrichment of ac4C on Timp1 CDS was examined via RIP-qPCR with anti-ac4C. n = 3. ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. the Gfp group, Student's t-test. (I) The effect of NAT10 downregulation on the ac4C level of Timp1 CDS (c motif sites). Cultured primary mouse astrocytes were transduced with lentivirus expressing shNat10 or shScr control for 48 h and the enrichment of ac4C on Timp1 CDS was examined via RIP-qPCR with anti-ac4C. n = 3. ∗P < 0.05 vs. the shScr group, Student's t-test. All data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

To investigate the role of NAT10 in the association between ac4C-modified mRNAs and autophagy, these 75 transcripts were assessed for matches with autophagy-related genes36, and 3 target transcripts (Timp1, Thpo, and Pkd1) were identified (Fig. 6B). Given the involvement of TIMP1 in autophagy37 and the FPKM enrichment of RNC-Timp1, we selected Timp1 as our candidate target transcript. Our first step was to investigate whether the changes in ac4C acetylation affected the level of Timp1. Using qPCR, we found that the expression of Timp1 was significantly increased after PT, and this increase was not reversed by remodelin-induced NAT10 inhibition (Fig. 6C). However, we did observe a reversal with remodelin treatment when we assessed the protein expression of TIMP1 with a Western blot (Fig. 6D), indicating that NAT10 may regulate TIMP1 expression by accelerating Timp1 mRNA translation efficiency. To verify this, we used a polysome fractionation assay and found that OGD enhanced ribosomal binding to Timp1 mRNA in cultured primary mouse astrocytes (mainly in the polysomal fraction) and that NAT10 inhibition blocked this increase, with Timp1 mRNA detected mainly in the monosomes or light polysomes in this condition (Fig. 6E).

We next sought to establish the Timp1 mRNA acetylated sites. ac4C has frequently been identified at specific repeated “CXXCXXCXX” motifs (“X” represents A, G, C, or U) in mRNA, especially in the gene coding domain sequence (CDS)18. We identified 3 potential regions containing the ac4C motif and designated these as the “a”, “b”, and “c” motif sites. Three pairs of primers were designed to cover the predicted motif regions [PCR primer pair 1 for the “a” motif site (+16 to +35), pair 2 for the “b” motif site (+213 to +232) and pair 3 for the “c” motif site (+536 to +555), with the first nucleotide of the CDS designated as +1] (Fig. 6F). The CDS fragment containing the “c” motifs was amplified from primary mouse astrocytes immunoprecipitated with the ac4C antibody (Fig. 6G). Given that NAT10 serves as a “writer,” bringing ac4C onto mRNA, we next measured the binding of NAT10 to the c motif region of Timp1 under conditions where the expression of NAT10 was manipulated. NAT10 upregulation by Lenti-Nat10 enhanced the level of ac4C in the “c” motif in primary mouse astrocytes, compared with the Gfp control (Fig. 6H). Lenti-shRNA-Nat10, but not the control, reversed the increase in NAT10–c motif binding (Fig. 6I), indicating that NAT10 likely regulates the ac4C modification of Timp1 mRNA.

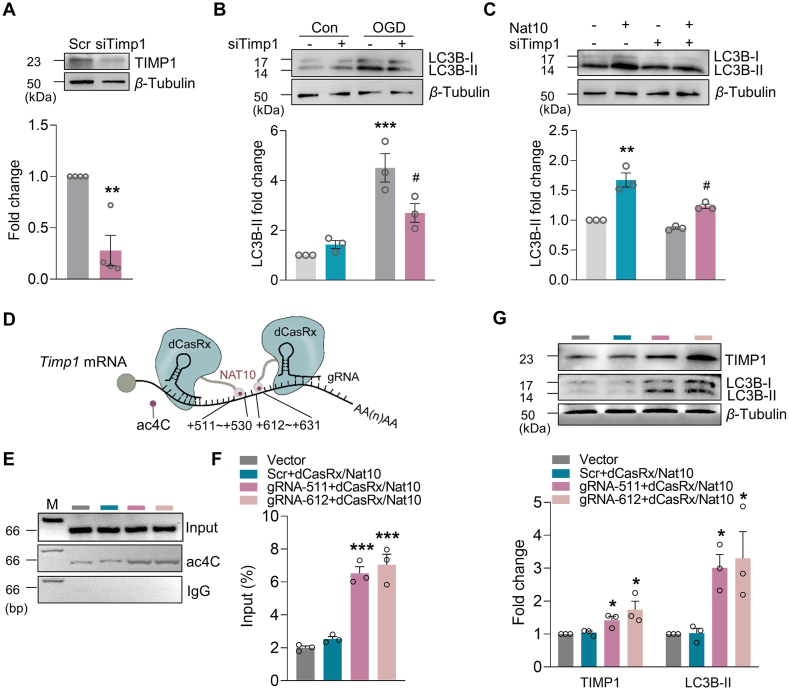

3.7. NAT10 regulates OGD-evoked autophagy via TIMP1 in primary mouse astrocytes

To confirm that TIMP1 modulates autophagy in ischemia, we transduced primary mouse astrocytes with Timp1 siRNA. Knockdown of Timp1 efficiently decreased TIMP1 expression (Fig. 7A) and significantly reversed the OGD-induced increase in LC3B-II and TIMP1 (Fig. 7B and Supporting Information Fig. S9A). Moreover, the transduction of astrocytes with Nat10 lentivirus resulted in enhanced LC3B-II expression, and this effect was inhibited in cells co-transduced with lentiviral vectors that expressed Nat10 and Timp1 siRNA (Fig. 7C). The efficiency of co-transduced with Lenti-Nat10 and Timp1 siRNA in cultured primary astrocytes was confirmed by a Western blot (Fig. S9B). Together, these data demonstrate that depression of TIMP1 expression may suppress astrocyte autophagy induced by NAT10 upregulation. We next used the CRISPR gene-editing system38 to further confirm the specific regulatory role of ac4C in TIMP1 protein expression. NAT10 was fused with inactivated CasRx protein (dCasRx/NAT10 fusion protein, identified in our previous study29) to specifically “write” ac4C to the c motifs via guide RNA (gRNA; Fig. 7D). We designed 2 gRNAs near the “c” motifs: gRNA-511 (+511 to +530) and gRNA-612 (+612 to +631), with the first nucleotide in the CDS designated as +1. The Timp1 ac4C level was significantly increased by co-transduction of CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 and either gRNA-511 or gRNA-612 (Fig. 7E and F). Furthermore, co-transduction of CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 with gRNA-511 or gRNA-612 significantly increased the expression of TIMP1 and LC3B-II in cultured primary astrocytes (Fig. 7G). Taken together, these data suggested that NAT10 regulates OGD-evoked autophagy by upregulating TIMP1 expression via ac4C modification of Timp1 mRNA.

Figure 7.

NAT10 regulates astrocyte autophagy via TIMP1. (A) Representative immunoblots of TIMP1 expression in cultured astrocytes with/without Timp1 siRNA transfection. Cultured primary mouse astrocytes were transfected with siRNA for 24 h. n = 4. ∗∗P < 0.01 versus the Scr group, Student's t-test. (B) The effect of Timp1 siRNA on the expression of LC3B-II in OGD-treated cells. n = 3. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the Con + Scr group; #P < 0.05 vs. the OGD + Scr group; two-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. (C) The effect of Nat10 and Timp1 siRNA on the expression of LC3B-II under OGD treatment. Lentiviruses expressing Nat10 and Timp1 siRNA were co-transduced into primary mouse astrocytes. After 48 h, the cells were subjected to OGD for 6 h. n = 3. ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. the Gfp + Scr group; #P < 0.05 vs. the Nat10+Scr group; two-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. (D) Cartoon showing CRISPR-dCasRx “writing” ac4C to the given CDS in Timp1 mRNA. gRNA, small guide RNA. 511 to 530 (gRNA-511) or 612 to 631 (gRNA-612) represented the location of the c ac4C motif sites in the Timp1 CDS. (E, F) Analysis of ac4C levels in the Timp1 CDS 48 h after co-transduction of CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 and gRNA-511 or gRNA-612 into primary mouse astrocytes. n = 3. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the Vector group, one-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. (G) The effect of CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 and gRNA-511 or gRNA-612 on the expression of TIMP1 and LC3B-II. CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 and gRNA-511 or gRNA-612 were co-transduced into primary mouse astrocytes for 48 h before collection for analysis. n = 3. ∗P < 0.05 vs. the Vector group, one-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. All data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

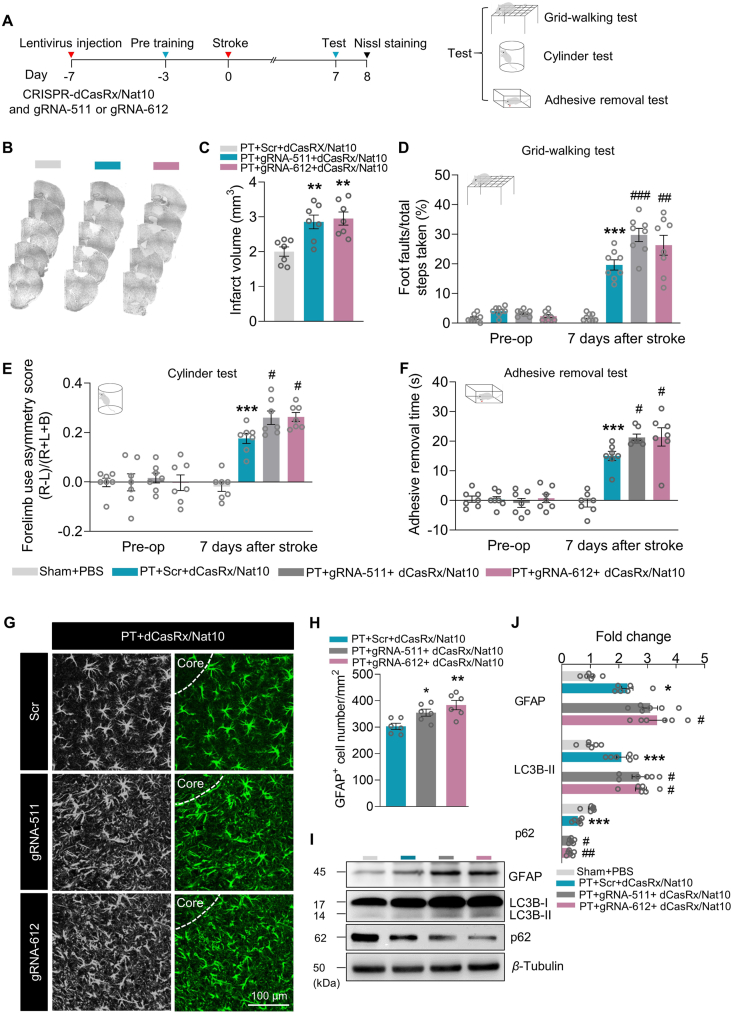

3.8. NAT10-regulated TIMP1 functions to brain recovery in the PT stroke model

Finally, we sought to examine whether NAT10 alters functional recovery in PT stroke mice through its effects on TIMP1. As shown in Fig. 8A, we co-microinjected CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 and gRNA-511 or gRNA-612 into the cortex 7 days before stroke and tested the functional recovery of mice on Day 7 after stroke. The co-microinjection led to the upregulation of TIMP1 in naïve mice, as demonstrated by Western blot (Supporting Information Fig. S10). Nissl staining showed that administration of CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 and gRNA-511 or gRNA-612 significantly increased the infarct volume in PT mice compared with administration of CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 and scrambled gRNA (Fig. 8B and C). Moreover, pre-treatment with CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 and gRNA-511 or gRNA-612 significantly aggravated ischemia-induced functional impairments compared with CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 and scrambled gRNA, as assessed by foot faults in the grid-walking task, forelimb asymmetry scores in the cylinder task, and removal time in the adhesive removal test (Fig. 8D–F). Next, we performed immunofluorescence staining to investigate the manipulation influence on ischemia-induced activity of astrocytes. As shown in Fig. 8G and H, microinjection of CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 and gRNA-511 or gRNA-612 significantly increased the GFAP+ cells in PT mice compared with administration of CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 and scrambled gRNA. Further, the level of autophagy in the peri-infarct area was also examined and the data showed that administration of CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 and gRNA-511 or gRNA-612 worsened the stroke-induced autophagy (Fig. 8I and J). Together, our results indicate that, after the PT stroke, NAT10 upregulates TIMP1 by enhancing the acetylation of Timp1 mRNA, and this upregulation of TIMP1 inhibits recovery of the injured brain.

Figure 8.

TIMP1 mediates the detrimental effect of NAT10 on functional recovery in PT mice. (A) Schematic of the experimental timeline. Lentivirus (LV; LV-CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 plus LV-gRNA-511 or LV-gRNA-612) was injected into the prospective stroke site in the cortex 7 days prior to stroke. Behavioral performances were examined at the pre-stroke baseline and on Day 7 after stroke. Nissl staining was performed on Day 8 after stroke. (B, C) Representative Nissl-stained sections from PT + scrambled + CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10, PT + gRNA-511+CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10, or PT + gRNA-612+CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 mice on Day 8 post-stroke. n = 7 animals/group. ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. the PT + Scr + CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 group, one-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. (D–F) The effect of co-microinjection of CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 and gRNA-511 or gRNA-612 on behavioral recovery on Day 7 after stroke, as measured by the grid-walking test (D), cylinder test of forelimb function (E), and adhesive removal test (F). n = 7 or 8 animals/group. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the Sham + PBS group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. the PT + Scr + dCasRx-Nat10 group; two-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. (G, H) Immunoreactivity for astrocytic marker GFAP under different treatment conditions on Day 8 after stroke. n = 6 animals/group. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. PT + Scr + CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 group, one-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. Scale bar, 100 μm. (I, J) The effect of co-microinjection of CRISPR-dCasRx-Nat10 and gRNA-511 or gRNA-612 on the expression of GFAP, LC3B-II and p62. The tissue in the peri-infarct region was collected on Day 8 after injury. n = 6 animals/group. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the Sham + PBS group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. the PT + Scr + dCasRx-Nat10 group; two-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. All data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

To further examine the effect of astrocytic TIMP1 depletion on brain repair, we used AAV- gfaABC1D-shTimp1 to knock down TIMP1 in astrocytes. As illustrated in Fig. 9A, AAV-gfaABC1D-shTimp1 or AAV-gfaABC1D-shScr was microinjected into the prospective stroke site 28 days before stroke; functional recovery of mice was tested on Day 7 after stroke followed by Nissl staining. The efficacy and specificity of AAV transduction were examined by Western blot and immunofluorescence, respectively (Fig. 9B and C). We then determined the effect of the downregulation of astrocytic TIMP1 on the infarct induced by ischemia. As shown in Fig. 9D and E, administration of shTimp1 significantly decreased the infarct volume compared with shScr; however, the benefits of infarction were deprived in astrocytic-specific autophagy-deficient mice induced by AAV-gfaABC1D-shAtg5 (Supporting Information Fig. S11A and S11B). Moreover, inhibition TIMP1 in astrocytes significantly alleviated ischemic impairments, evidenced by the decreased foot faults in the grid-walking task, the lowered forelimb asymmetry scores in the cylinder task, and diminished time spent in the adhesive removal test (Fig. 9F–H). Together, these results suggest that Timp1 mRNA may be one of the targets of NAT10-mediated brain outcomes after stroke.

Figure 9.

Downregulation of astrocytic TIMP1 promotes functional recovery in PT mice. (A) Experimental procedure and timeline. The astrocyte-targeting AAV-shRNA-Timp1 or AAV-shRNA-Scr was microinjected into the prospective stroke site in the cortex on Day 28 before stroke. Behavioral performance was examined at the pre-stroke baseline and on Day 7 after stroke followed by Nissl staining. (B) The level of TIMP1 was measured by Western blot. The cortex was collected on Day 28 after microinjection. n = 3 animals/group. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the shRNA-Scr group, Student's t-test. (C) Representative images of AAV-shRNA-Timp1 (red) infection of astrocytes (green). Scale bar, 50 μm. (D, E) Representative Nissl-stained sections from PT + shRNA-Scr or PT + shRNA-Timp1 mice on Day 8 post-stroke. n = 6 animals/group. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the PT + shRNA-Scr group, Student's t-test. (F–H) TIMP1 inhibition in astrocytes improved behavioral recovery on Day 7 after stroke as measured by the grid-walking test (F), the cylinder test of forelimb function (L indicated the left forepaw, R indicated the right forepaw) (G), and the adhesive removal test (H). n = 9 animals/group. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. the sham + shRNA-Scr group; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 vs. the PT + shRNA-Scr group; two-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak post hoc multiple-comparisons test. All data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that inhibiting NAT10, either pharmacologically or via an astrocyte-targeted adeno-associated virus, significantly reduces infarction and improves functional recovery after stroke, via inhibition of neurotoxic astrocyte reactivity and autophagy. Examination of the underlying mechanism revealed that NAT10 catalyzes Timp1 mRNA acetylation and thereby increases the expression of TIMP1 in the peri-infarct region in a PT model of stroke.

The therapeutic effects of NAT10 inhibitors have been studied in multiple diseases, including aging, cancer, and myocardial infarction21,39,40. A previous study using clinical gene burden testing of peripheral blood-derived exosomes collected from patients with early onset stroke showed that NAT10 has a single nucleotide polymorphism22; however, there has been comparatively little research on the potential benefits of inhibiting NAT10 in ischemic stroke. Here, we demonstrated that NAT10 is increased both in stroke patients and in a PT mouse model of stroke, which led us to further dissect the role of NAT10 in functional recovery after ischemic stroke. We should note that the sample size of the human part in our study is comparatively small, making it susceptible to a higher rate of false positives41. Therefore, we also utilized randomized experimental designs in mice to reinforce our findings on the expression and function of NAT10 in ischemic stroke.

ac4C is a widespread reversible modification in mammalian mRNA42,43 that participates in the improvement of mRNA translation efficiency and the stability of mRNA18,44. To date, there have been no reports about the effect(s) of ac4C on damage after ischemic stroke. Our results showed that the total amount of ac4C was significantly increased in the peri-infarct cortex and that this increase resulted from ischemia-induced upregulation of NAT10. As the only known “writer” enzyme for ac4C production in mammals45, overexpression of NAT10 deposits ac4C in sequence motifs in mRNA; conversely, NAT10 downregulation significantly reduces ac4C levels in HeLa cells18. Consistent with a previous report46, our study showed increased expression of NAT10 and increased levels of ac4C in cultured astrocytes and the peri-infarct cortex after ischemic stroke. Furthermore, inhibiting NAT10 ameliorated the increase in ac4C acetylation in cultured astrocytes and the peri-infarct cortex, thereby attenuating neurotoxic reactivity in astrocytes and autophagy.

Ischemic stroke often triggers maladaptive autophagy7 that continues through the post-ischemic period. Thus, exploring ischemia-related autophagy in neural tissue may provide novel information for treatment of stroke. Recent studies have demonstrated that inhibiting autophagy correlates with a decreased infarct size and treatments capable of decreasing infarct size are often accompanied by attenuated autophagy7,47,48. Using RNC sequencing in the peri-infarct cortex of remodelin-administrated PT mice, we identified 3 candidate ac4C-modified genes that were also associated with autophagy (Timp1, Thpo, and Pkd1). Given that (i) significant changes and enrichment in Timp1 were detectable in the remodelin-treated PT group compared with the vehicle-treated PT group and (ii) no previous studies had been conducted on NAT10 and TIMP1, we explored the potential link between NAT10 and TIMP1 regulation after stroke. NAT10 inhibition alleviated the increase in TIMP1 expression in the peri-infarct cortex and cultured astrocytes subject to OGD, but did not attenuate the increased expression of Timp1 mRNA, implying that NAT10 may affect TIMP1 through posttranscriptional modifications. Consistent with previous studies19,49, we demonstrated that NAT10 catalyzed and enhanced the translation of Timp1 mRNA, resulting in an increased level of astrocyte autophagy after ischemic stroke. In addition to stroke, a better understanding of the role of NAT10 in astrocyte autophagy may facilitate the identification of novel therapeutic targets for the treatment or control of other diseases related to astrocyte autophagy. In the present study, our results suggest that TIMP1 is regulated by NAT10, and prompt that TIMP1 likely participates in astrocyte activation and autophagy. However, the specific regulatory mechanism of TIMP1 in astrocyte activation or autophagy is not clear in ischemic stroke: gain- and loss-of-function studies in conditioned astrocytic TIMP1 knockout animals would help to uncover the specific contributions of TIMP1-mediated genetic programs to poststroke astrocytes.

Despite technological and biological advances in cerebrovascular research, tissue plasminogen activator is the only agent approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and remains the major treatment for ischemia50,51. However, many patients with ischemic stroke are at high risk of serious cerebral damage because of the narrow therapeutic window during which tissue plasminogen activator is effective, reperfusion damage, and hemorrhagic complications4,52. By contrast, NAT10-based therapies would have a relatively wide therapeutic window: Remodelin (a specific inhibitor for NAT10) could be administered on Day 3 after stroke onset, providing a more practical treatment window than current therapies, which have a treatment window of hours rather than days. The clinical significance of this is already clear, but future studies focused on the specific time course in various mammalian stroke models will reveal the precise temporal scope for these new potential post-stroke interventions.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrated here that ischemic stroke increases both NAT10 expression and the total level of ac4C in the peri-infarct cortex. Reversing this abnormal increase reduced the infarction and promoted functional recovery in mice with PT stroke in a Timp1-ac4C-dependent manner. Our data indicate that NAT10 should be viewed as a promising therapeutic target for functional post-stroke recovery, with great potential for clinical applications.

Author contributions

Li Yang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Xiaotong Li: Validation, Methodology, Investigation. Yaxuan Zhao: Validation, Investigation. Hao Chen: Supervision, Resources. Can Wang: Validation, Investigation. Angrong Wu: Validation, Funding acquisition. Xintong Guo: Validation, Investigation. Yue Huang: Visualization, Methodology. Qihui Wang: Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Lingyun Hao: Visualization, Methodology. Xiaowen Li: Resources. Ying Ji: Resources. Jin Ban: Resources. Guangtian Wang: Methodology, Funding acquisition. Junli Cao: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Zhiqiang Pan: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32200818 to Ling Yang, 82371243, 82171234 and 81971041 to Zhiqiang Pan, 82201391 to Qihui Wang, 82104147 to Guangtian Wang), the Jiangsu Provincial Association of Science and Technology Youth Science and Technology Talent Recruitment Project (Ling Yang, China), the Jiangsu-Specially Appointed Professor Project, the Jiangsu Province 333 High-Level Talent Cultivation Project, Key Project of Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Education Department (22KJA320008 to Zhiqiang Pan, China), Jiangsu Training Program of Innovation and Entrepreneurship for Undergraduates (202310313014Z to Angrong Wu, China), and the Starting Grants of Excellent Talents of Xuzhou Medical University (Ling Yang, China). The experiments in this study were partly completed in the Public Experimental Research Center of Xuzhou Medical University. We sincerely thank Dr. Fuxing Dong (Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou, China) for his enthusiastic help with the laser scanning confocal microscopy experiments. We also sincerely thank Wuyang Wang from Xuzhou Medical University for providing us with the interference sequence of mouse ATG5.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting information to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2025.03.042.

Contributor Information

Li Yang, Email: Yangli2021@xzhmu.edu.cn.

Junli Cao, Email: caojl0310@aliyun.com.

Zhiqiang Pan, Email: zhiqiangp2002@aliyun.com.

Appendix A. Supporting information

The following is the Supporting Information to this article.

References

- 1.Dimyan M.A., Cohen L.G. Neuroplasticity in the context of motor rehabilitation after stroke. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:76–85. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saini V., Guada L., Yavagal D.R. Global epidemiology of stroke and access to acute ischemic stroke interventions. Neurology. 2021;97:S6–S16. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed N., Kellert L., Lees K.R., Mikulik R., Tatlisumak T., Toni D., et al. Results of intravenous thrombolysis within 4.5 to 6 hours and updated results within 3 to 4.5 hours of onset of acute ischemic stroke recorded in the safe implementation of treatment in stroke international stroke thrombolysis register (SITS-ISTR): an observational study. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:837–844. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell B.C.V., Ma H., Parsons M.W., Churilov L., Yassi N., Kleinig T.J., et al. Association of reperfusion after thrombolysis with clinical outcome across the 4.5- to 9-hours and wake-up stroke time window: a meta-analysis of the EXTEND and EPITHET randomized clinical trials. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78:236–240. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.4123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qin C., Yang S., Chu Y.H., Zhang H., Pang X.W., Chen L., et al. Signaling pathways involved in ischemic stroke: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct Targeted Ther. 2022;7:215. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01064-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuo Q.Z., Zhang S.T., Lei P. Mechanisms of neuronal cell death in ischemic stroke and their therapeutic implications. Med Res Rev. 2022;42:259–305. doi: 10.1002/med.21817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ajoolabady A., Wang S., Kroemer G., Penninger J.M., Uversky V.N., Pratico D., et al. Targeting autophagy in ischemic stroke: from molecular mechanisms to clinical therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. 2021;225 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai W., Hu M., Li C., Wu R., Lu D., Xie C., et al. FOXP3+ macrophage represses acute ischemic stroke-induced neural inflammation. Autophagy. 2023;19:1144–1163. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2022.2116833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jha M.K., Kim J.H., Song G.J., Lee W.H., Lee I.K., Lee H.W., et al. Functional dissection of astrocyte-secreted proteins: implications in brain health and diseases. Prog Neurobiol. 2018;162:37–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliveira J.F., Araque A. Astrocyte regulation of neural circuit activity and network states. Glia. 2022;70:1455–1466. doi: 10.1002/glia.24178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Candelario-Jalil E., Dijkhuizen R.M., Magnus T. Neuroinflammation, stroke, blood–brain barrier dysfunction, and imaging modalities. Stroke. 2022;53:1473–1486. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.036946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sims N.R., Yew W.P. Reactive astrogliosis in stroke: contributions of astrocytes to recovery of neurological function. Neurochem Int. 2017;107:88–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aswendt M., Wilhelmsson U., Wieters F., Stokowska A., Schmitt F.J., Pallast N., et al. Reactive astrocytes prevent maladaptive plasticity after ischemic stroke. Prog Neurobiol. 2022;209 doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2021.102199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choudhury G.R., Ding S. Reactive astrocytes and therapeutic potential in focal ischemic stroke. Neurobiol Dis. 2016;85:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ni X.C., Wang H.F., Cai Y.Y., Yang D., Alolga R.N., Liu B., et al. Ginsenoside Rb1 inhibits astrocyte activation and promotes transfer of astrocytic mitochondria to neurons against ischemic stroke. Redox Biol. 2022;54 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito S., Akamatsu Y., Noma A., Kimura S., Miyauchi K., Ikeuchi Y., et al. A single acetylation of 18S rRNA is essential for biogenesis of the small ribosomal subunit in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:26201–26212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.593996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arango D., Sturgill D., Alhusaini N., Dillman A.A., Sweet T.J., Hanson G., et al. Acetylation of cytidine in mRNA promotes translation efficiency. Cell. 2018;175 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.030. 1872-86.e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arango D., Sturgill D., Yang R., Kanai T., Bauer P., Roy J., et al. Direct epitranscriptomic regulation of mammalian translation initiation through N4-acetylcytidine. Mol Cell. 2022;82 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.06.022. 2797-814.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu T., Wang J., Wu Y., Wu J.Y., Lu W.C., Liu M., et al. Ac4C enhances the translation efficiency of Vegfa mRNA and mediates central sensitization in spinal dorsal horn in neuropathic pain. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2023;10 doi: 10.1002/advs.202303113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liao L., He Y., Li S.J., Yu X.M., Liu Z.C., Liang Y.Y., et al. Lysine 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation of NAT10 promotes cancer metastasis in an ac4C-dependent manner. Cell Res. 2023;33:355–371. doi: 10.1038/s41422-023-00793-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balmus G., Larrieu D., Barros A.C., Collins C., Abrudan M., Demir M., et al. Targeting of NAT10 enhances healthspan in a mouse model of human accelerated aging syndrome. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1700. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03770-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaworek T., Ryan K.A., Gaynor B.J., McArdle P.F., Stine O.C., Td O.C., et al. Exome array analysis of early-onset ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2020;51:3356–3360. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.031357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joy M.T., Ben Assayag E., Shabashov-Stone D., Liraz-Zaltsman S., Mazzitelli J., Arenas M., et al. CCR5 is a therapeutic target for recovery after stroke and traumatic brain injury. Cell. 2019;176 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.044. 1143-57.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ni H.Y., Song Y.X., Lin Y.H., Cao B., Wang D.L., Zhang Y., et al. Dissociating nNOS (neuronal NO synthase)-CAPON (carboxy-terminal postsynaptic density-95/discs large/zona occludens-1 ligand of nNOS) interaction promotes functional recovery after stroke via enhanced structural neuroplasticity. Stroke. 2019;50:728–737. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.022647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang L., Han B., Zhang Z., Wang S., Bai Y., Zhang Y., et al. Extracellular vesicle-mediated delivery of circular RNA SCMH1 promotes functional recovery in rodent and nonhuman primate ischemic stroke models. Circulation. 2020;142:556–574. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.045765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li B., Xi W., Bai Y., Liu X., Zhang Y., Li L., et al. FTO-dependent m6A modification of Plpp3 in circSCMH1-regulated vascular repair and functional recovery following stroke. Nat Commun. 2023;14:489. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36008-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tao W., Tian G., Xu S., Li J., Zhang Z., Li J. NAT10 as a potential prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target for HNSCC. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:413. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-02124-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J., Chen Z., Chen F., Xie G., Ling Y., Peng Y., et al. Targeted mRNA demethylation using an engineered dCas13b-ALKBH5 fusion protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:5684–5694. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang M., Yang K., Wang Q.H., Xie L., Liu Q., Wei R., et al. The cytidine N-acetyltransferase NAT10 participates in peripheral nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain by stabilizing SYT9 expression in primary sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2023;43:3009–3027. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2321-22.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tao Y., Wang Q.H., Li X.T., Liu Y., Sun R.H., Xu H.J., et al. Spinal-specific super enhancer in neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2023;43:8547–8561. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1006-23.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan Z., Zhang Q., Liu X., Zhou H., Jin T., Hao L.Y., et al. Methyltransferase-like 3 contributes to inflammatory pain by targeting TET1 in YTHDF2-dependent manner. Pain. 2021;162:1960–1976. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panda A.C., Martindale J.L., Gorospe M. Polysome fractionation to analyze mRNA distribution profiles. Bio Protoc. 2017;7 doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang R., Zhang Y., Bai Y., Han B., Ju M., Chen B., et al. N6-Methyladenosine modification of fatty acid amide hydrolase messenger RNA in circular RNA STAG1-regulated astrocyte dysfunction and depressive-like behaviors. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;88:392–404. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han B., Zhang Y., Zhang Y., Bai Y., Chen X., Huang R., et al. Novel insight into circular RNA HECTD1 in astrocyte activation via autophagy by targeting MIR142–TIPARP: implications for cerebral ischemic stroke. Autophagy. 2018;14:1164–1184. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1458173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang M., Xu Y., Zhang Y., Chen Y., Chang G., An G., et al. Deciphering the autophagy regulatory network via single-cell transcriptome analysis reveals a requirement for autophagy homeostasis in spermatogenesis. Theranostics. 2021;11:5010–5027. doi: 10.7150/thno.55645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu S.Y., Wang Y.C., Zuchini R., Lan K.Y., Liu H.S., Lan S.H. Secretory autophagy-promoted cargo exocytosis requires active RAB37. Autophagy. 2024;20:933–934. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2023.2210446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lorsch Z.S., Hamilton P.J., Ramakrishnan A., Parise E.M., Salery M., Wright W.J., et al. Stress resilience is promoted by a Zfp189-driven transcriptional network in prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:1413–1423. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0462-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie R., Cheng L., Huang M., Huang L., Chen Z., Zhang Q., et al. NAT10 drives cisplatin chemoresistance by enhancing ac4C-associated DNA repair in bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 2023;83:1666–1683. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-22-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang K., Zhou L.Y., Liu F., Lin L., Ju J., Tian P.C., et al. PIWI-interacting RNA HAAPIR regulates cardiomyocyte death after myocardial infarction by promoting NAT10-mediated ac4 C acetylation of Tfec mRNA. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2022;9 doi: 10.1002/advs.202106058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mar R.A., Spreng R.N., Deyoung C.G. How to produce personality neuroscience research with high statistical power and low additional cost. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2013;13:674–685. doi: 10.3758/s13415-013-0202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiener D., Schwartz S. The epitranscriptome beyond m6A. Nat Rev Genet. 2021;22:119–131. doi: 10.1038/s41576-020-00295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]