Abstract

The prevalence of tattoos in western countries is about 20%. Tattoo ink may contain carcinogenic compounds. The aim of this study was to investigate if tattoo exposure is associated with an increased risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in individuals. In this population-based case-control study, 2857 cases aged 20 to 60 years, diagnosed between 2014 and 2017, were identified in the Swedish Cancer Registry. Statistics Sweden identified 3 random age- and sex-matched controls per case from the Swedish Total Population Register using incidence-density sampling. In 2019, participants answered a questionnaire regarding lifestyle factors, including tattoos and sun habits. We used logistic regression to investigate if tattoo exposure was associated with the relative risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. 61% of the cases and 53% of the controls replied to the questionnaire. Among the 1600 cases and the 4551 controls that participated, 15.1% and 17.6% had at least one tattoo before the index date. We found no increased risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in tattooed compared with non-tattooed individuals (incidence rate ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.78–1.15). Tattoo exposure was not associated with the risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in this first study of the association. However, more epidemiologic studies are needed before consensus regarding a lack of association can be reached.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10654-025-01230-z.

Keywords: Tattoo, Keratinocyte cancer, Non-melanoma skin cancer, Risk factors, Lifestyle factors, Health risks

Introduction

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second most common cancer in Sweden [1, 2], and the second most common skin cancer type in the United States [3]. The incidence has been increasing steadily since the 1980s. In Sweden, the incidence of primary cSCC was 97 per 100,000 individuals in 2021 [2] compared with around 30 per 100 000 in the early 2000s [4]. Suggested explanations for this increase include better access to care, changing sunbathing habits, and an aging population. Lifestyle-related risk factors are less well studied.

The prevalence of tattoos was recently reported to be > 20% in some European countries, and > 30% in the United States and numbers are reported to be even higher in younger age groups [5–9]. Possible evidence for having a cosmetic tattoo at the site of an early onset basal cell cancer tumour compared to other sites was observed in an American study [10]. Yet, the potential association between tattoos and cSCC has never been investigated.

Traditionally, the colour in tattoo ink comes from various pigments such as azo pigments, carbon black and metal salts, and may contain possible and probable human carcinogens such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [11, 12], aromatic amines [13–16], and metals [17–21]. In a recent study, the authors showed that the declaration of ingredients in tattoo ink was often incorrect [22]. Another study found forged labels on tattoo ink bottles; permitted pigments were declared instead of the banned ones present in the ink [23]. Risk analysis or testing for the safety of lifelong intradermal exposure to tattoo ink has not been performed, and the long-term health implications are broadly unknown. However, recent evidence suggest that tattoo exposure may be associated with increased cancer risk [24, 25].

Here, we hypothesize, based on the presence of carcinogenic compounds in tattoo ink and the local exposure and potentially systemic exposure over time, that tattoos may be a risk factor for cSCC both locally and systemically, possibly through direct and indirect mechanisms such as DNA-adduct formation and by contributing to an inflammatory environment [26].

The aim of this study was to investigate if tattoo exposure was associated with an increased risk of cSCC. We have included cases aged 20–60 years when diagnosed with cSCC, because the prevalence of tattoos is higher in younger people.

Materials and methods

Setting

We aimed to investigate if tattoo exposure is associated with an increased risk of cSCC. Using a population-based case-control design, we identified cases of cSCC diagnosed between 2014 and 2017 in the Swedish National Cancer Register. Controls were identified in the Total Population Register using incidence-density sampling matching on age and sex. We assessed self-reported exposure using a structured questionnaire distributed by Statistics Sweden between February and April 2021. In a case-control study with incidence-density sampling, the odds ratio offers an unbiased estimate of the incidence rate ratio (IRR), which is interpreted as a relative risk [27]. This study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2019–03138).

Participants

The inclusion criterion was a primary diagnosis of cSCC at the age of 20–60 years. The most recent data at the time of sampling (in 2019) was used, and resulted in cases diagnosed between 2014 and 2017. The date of diagnosis was the index date. The next-of-kin of deceased individuals on January 2021 were contacted according to a prespecified hierarchy (i.e. spouse, common-law spouse, child, parent or sibling) to avoid survivorship bias in case tattoos were associated with a more lethal form of cSCC.

Three random controls of the same age and sex per case were identified by Statistics Sweden using incidence-density sampling. Controls were all free of cSCC at the index date, but individuals with other malignancies were eligible for inclusion. Individuals with psychiatric disorders (diagnosis codes F20-29 in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision) were excluded due to the risk of psychological distress from participation by cross-referencing the study population with the National Patient Register.

Statistics Sweden performed a descriptive dropout analysis on aggregated data regarding the sociodemographic characteristics of responders and non-responders at the time of the survey. Participants were informed that they consented to participate in the study by answering the questionnaire. Next-of-kin were first given information about the study and asked to consent to participate via post, after which they received the questionnaire.

Variables

Outcome: cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

Incident primary cSCC was defined according to the ICD-O-3.2 (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd Edition, 2nd Update) typography code C44 (i.e. non-melanoma skin cancer) in combination with any of the morphology codes listed in Table S1.

Exposure: tattoos

We defined exposure as permanent tattoos acquired for decorative, cosmetic, or medical purposes. Cosmetic tattoos entail permanent or semi-permanent makeup, and medical tattoos are used in procedures such as breast reconstruction after mastectomy. Respondents were asked to include tattoos that had been removed; the age they got their first tattoo; and participants were classified as unexposed if they had their first tattoo after their index date.

We powered the study to assess tattoo exposure as the presence or absence of tattoos (dichotomous variable). We also assessed the total area of the body covered with tattoos to investigate crude dose-response relationships by asking participants to estimate the area of tattooed body surface on a categorical scale (< 1 palm/1–5 palms/>5 palms), as well as number of received tattoo sessions (1; 2–3; 4–5; 6–9; >=10). We asked participants to indicate the anatomic location of their tattoos on a body manikin and about the colours used in their tattoos (black, grey, brown, red, blue, green, yellow, white, purple, pink, orange, turquoise, skin colour, or other).

Confounders and effect modifiers

Using a directed acyclic graph (dagitty.net, v3.0), we visualized the relationships between exposure and outcome to identify potential confounders (Figure S1). Based on our assumptions, UV exposure and socioeconomic status (SES) constitute the minimal sufficient adjustment set to control for confounding in the relationship between tattoos and cSCC.

The most established risk factor for cSCC is cumulative sun exposure. Low-grade, long-term sun exposure is well described in the literature [28, 29]. We assume that UV exposure may confound the association between tattoo exposure and cSCC through an unmeasured common cause reflecting a general interest in one’s appearance. In addition, we anticipated that UV exposure may be an effect modifier of the association between tattoos and cSCC because UV exposure can induce the release of potentially carcinogenic aromatic amines from azo pigments in the tattoo [15, 16]. We used self-reported information about occupational and recreational UV exposure from questionnaires using validated questions [30].

We constructed a new variable, a UV exposure index, to account for cumulative UV exposure from multiple exposure sources according to the following factors: “occupational sun exposure (April–September)”, “recreational sun travel” and “sunbed use”. Respondents were considered to have high UV exposure if they provided ≥ 1 positive response in the high exposure category for any of these factors; medium UV exposure if they did not provide a positive response to any of the high categories and ≥ 1 response in a medium category; and low UV exposure if they provided positive response only in the lowest categories. For details on the construction of the UV exposure index, see Table S2.

We assumed that skin characteristics might affect an individual’s inclination to get a tattoo, and fair skin is an established risk factor for cSCC [31]. To investigate the association between tattoo exposure and cSCC among participants with such genetic risk factors for cSCC, we created a phenotypic risk index (high risk/medium risk/low risk) according to the Fitzpatrick scale [32], with skin pigmentation (Fitzpatrick skin types I-VI) and skin reaction after sun exposure (derived from Fitzpatrick skin types I-IV). Participants who reported “skin reaction to first sun exposure: burns (sometimes with blisters) and pain for at least 48 h” or “burns with pain that disappears within 24 h”, regardless of their skin tone, were classified as high risk. Participants who reported “skin reaction to first sun exposure: first burn, then tan”, regardless of skin tone, were classified as medium risk. Participants who reported a “very fair” or fair” skin tone and reported “skin reaction to first sun exposure: tan immediately” were classified as medium risk. Participants who reported “medium”, “olive”, “brown” or “dark brown” skin tone and reported “skin reaction to first sun exposure: tan immediately” were classified as low risk.

Although the direction of the association is unclear, SES seems to be related to cSCC [33–35] and is also associated with the prevalence of tattoos [36, 37]. We retrieved information about respondents’ educational attainment at the index date (categorized as primary and lower secondary/upper secondary/postsecondary education) and primary income source the year before the index date (categorized as [employed, student, parental leave, care of ill child or relative]/[unemployed, retired, sick leave, no income, financial aid]) from registers. We reasoned that the primary income source the year before diagnosis would better represent the SES because a cancer diagnosis may lead to sick leave and a lower income. Self-reported information about smoking (a proxy for SES) was obtained via the questionnaire; smoking was categorized as never smoker/ex-smoker/current smoker.

We hypothesized that lifelong diseases requiring immunosuppressive therapy, indicating a more severe stage of disease, may confound the association between tattoos and cSCC, particularly in the case of inflammatory skin diseases, such as psoriasis. With the background of the Koebner phenomenon, whereby insults to the skin such as tattoos can trigger, for example, psoriasis [38], we hypothesized that inflammatory skin disease may affect an individual’s likelihood of getting a tattoo. Patients on immunosuppressive medication, such as patients with psoriasis or patients with a transplanted organ, have a higher risk for cSCC [39, 40].

Data sources

Registry data

Cases were identified in the National Cancer Register (National Board of Health and Welfare). Health care providers in Sweden are obliged to report all primary neoplasms using both clinical and morphological diagnostic codes, and the register coverage of skin cancers is 99% [41]. In addition, 99% of skin tumours are confirmed morphologically [42]. Statistics Sweden identified controls in the Total Population Register, and if patients were deceased, their next-of-kin was identified in the Total Population Register or the Multi-Generation Register. The National Patient Register (National Board of Health and Welfare) was used to exclude individuals at risk of psychological distress from participation and to retrieve data on conditions associated with immunosuppression. The National Prescribed Drug Register (National Board of Health and Welfare) was used to retrieve data on prescribed and filled immunosuppressive medication. Information about SES, including income source and education level, was retrieved from the Longitudinal Integrated Database for Health Insurance and Labor Market Studies (LISA, Statistics Sweden).

Questionnaire

A questionnaire designed to assess exposure to tattoos and other lifestyle factors was sent to the participants. The questionnaire has been described in detail elsewhere [7]. The next-of-kin of deceased individuals received a shorter questionnaire with less detailed questions. We piloted the questionnaire to assess the reliability of the exposure assessment by having 28 tattooed individuals assess their tattooed body surface on the same occasion as a trained research assistant. The weighted Cohen’s kappa for the ordinal variable was 0.79 [7]. The overall questionnaire was reviewed for content and clarity by (a) participants in the pilot study and (b) survey experts at Statistics Sweden.

Study size

We used an a priori statistical power analysis to determine the sample size. We considered tattoo status as a dichotomous variable and assumed the tattoo prevalence to be 17% among the controls, as reported in the Swedish environmental health report in 2017 [6]. We wanted to be able to detect a risk ratio of 1.3 with 80% power. To achieve this, we would have to include 1300 cases with 2 controls per case. To account for the relatively low response rate of questionnaires, we aimed to include 3000 cases with 3 controls per case.

Statistical methods

We used non-parametric statistics for descriptive analysis because our variables did not follow a normal distribution. We had few missing data and decided to perform complete case analyses.

We used logistic regression models to investigate the potential association between tattoos and cSCC. In a case-control study with incidence-density sampling, the odds ratio offers an unbiased estimate of the incidence rate ratio (IRR). To align with study protocol, we used conditional logistic regression in our primary analysis. To maximize the use of the available data and optimize precision, we also ran analyses using unconditional logistic regression, where we broke matching sets [43, 44]. Because we introduced selection bias by using balanced matching (case: control ratio 1:3) we made basic adjustments for age (5-year categories from < 40 years) with a term for residual age and sex to account for the original confounding and the introduced selection bias [45]. We also adjusted for time (index year in quartiles) in unconditional analysis to account for the bias introduced by breaking the matching [45]. The fully adjusted models were in addition to basic adjustments adjusted for education level, primary income source, smoking, phenotypic risk index and UV exposure index. We investigated potential effect modification by UV exposure by including an interaction term (tattoo × UV exposure index) in the model. For the interaction analysis we merged the UV-index categories “low” and “medium” for sufficient statistical power. A potential crude dose-response relationship between the area of tattooed body surface and cSCC was investigated. We categorized the tattooed body surface as < 1 palm;>1 palm; no tattoo, and number of sessions as 1 session;2–3 sessions;>4 sessions.

Sensitivity analysis

We limited the cases to individuals receiving their first ever cSCC diagnosis in a sensitivity analysis. Secondly, we explored the potential modifying role of immunosuppression on the association between tattoo exposure and cSCC in the fully adjusted model by considering the use of immunosuppressive drugs (a) an effect modifier by inclusion of an interaction term, and (b) a confounder by inclusion of a fixed effect. We used registry data on ≥ 1 filled prescription of immunosuppressive drugs before the index date (i.e. ATC code L04). Finally, the next-of-kin of deceased individuals (n = 19) and their controls (n = 206) were included in a sensitivity analysis, where UV exposure index was based only on questions included in the questionnaire sent to relatives: “sunbed use” and “occupational sun exposure (April–September)”, and phenotypic risk index were not included.

Results

Study population

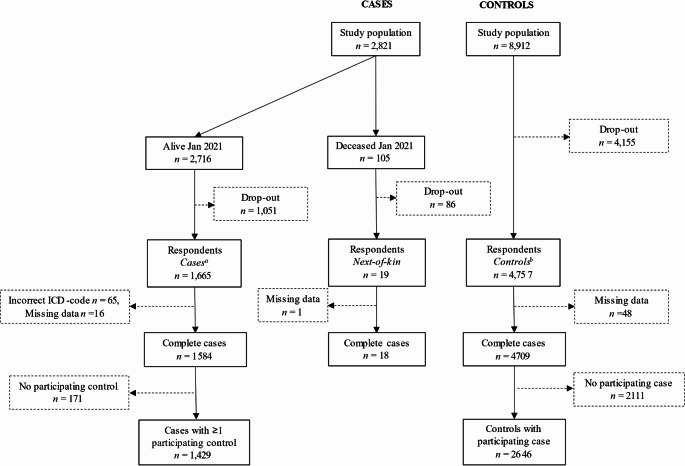

In January 2021, 95% (n = 2716) of the identified cases were alive (Fig. 1). A total of 1665 cases, 4757 controls, and 19 next-of-kin responded to the questionnaire, giving response rates of 61%, 53% and 16%, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of cases, controls and next-of-kin from the sampling frame to the statistical analysis. All available cases aged 20–60 years during 2014–2017 were included in the sampling frame. aNumber of respondents included in crude unmatched analysis were n = 1600, due to the 65 incorrect ICD-codes. bNumber of respondents included in crude unmatched analysis were n = 4551. The remaining n = 206 controls were from risk sets with deceased cases and therefore only included in the next-of-kin sensitivity analysis

Dropout analysis

The descriptive dropout analysis (Table S3) showed that respondents were more often women, older, married, of higher SES, with a higher level of education, and born in Sweden. We also found that responders among the cases had slightly higher income and education levels and were born in Sweden to a greater extent than the responders among the controls.

Descriptive characteristics

The median age was 56 years (interquartile range, 9 years) for the cases and 56 years (interquartile range, 10 years) for the controls. Participating cases and controls were fairly similarly distributed with regard to sex, educational attainment and marital status. Cancer cases had a higher household disposable income than controls. Cancer cases had a lower frequency of current smokers than the control group, but a higher proportion of previous smokers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participating cases and controls

| Cases, n (%) | Controls, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 653 (41) | 1756 (39) |

| Female | 947 (59) | 2795 (61) |

| Educational attainment, index date | ||

| Primary and lower secondary | 111 (7) | 407 (9) |

| Upper secondary | 683 (43) | 2073 (46) |

| Postsecondary | 804 (50) | 2060 (45) |

| Missing | 2 | 11 |

| Disposable income, household (SEK) | ||

| < 340,800 | 353 (22) | 1135 (25) |

| 340,800–538,200 | 364 (23) | 1136 (25) |

| 538,300–737,500 | 392 (25) | 1137 (25) |

| ≥ 737,600 | 488 (31) | 1137 (25) |

| Missing | 3 | 6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/registered partnership | 925 (58) | 2665 (59) |

| Divorced/widowed | 305 (19) | 780 (17) |

| Unmarried | 369 (23) | 1105 (24) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 |

| Smoking | ||

| Yes, current | 120 (8) | 516 (11) |

| Yes, previously | 621 (39) | 1583 (35) |

| No, never | 854 (54) | 2447 (54) |

| Missing | 5 | 5 |

Cases were more exposed to UV radiation from recreational exposure such as holidays in sunny destinations and sunbeds, and thus had a higher frequency in the highly exposed category of the UV exposure index (Table 2). Unexpectedly, cases were working outside to a lesser extent than controls, but the proportion of time outside for those who worked outside was similar between the groups.

Table 2.

Self-reported UV exposure at the time of the survey

| Cases, n (%) | Controls, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Occupational sun exposure (April–September) | ||

| Yes | 255 (16) | 945 (21) |

| No | 1078 (68) | 2860 (63) |

| I don’t work | 261 (16) | 724 (16) |

| Missing | 6 | 22 |

| Occupational sun exposure (April–September), time outside | ||

| >20 h/week | 67 (25) | 292 (29) |

| 6–20 h/week | 125 (47) | 450 (45) |

| ≤5 h/week | 74 (28) | 253 (25) |

| Recreational sun travel < 13 years of age | ||

| Yes, every year | 397 (25) | 851 (19) |

| Yes, occasionally | 1005 (63) | 2882 (64) |

| No, never | 183 (12) | 786 (17) |

| Missing | 15 | 32 |

| Sunbed use > 13 years of age | ||

| Several times per year | 355 (22) | 587 (13) |

| Occasionally | 888 (56) | 2462 (54) |

| Never | 349 (22) | 1476 (33) |

| Missing | 8 | 26 |

| UV exposure index | ||

| Ever high exposure | 656 (41) | 1486 (32) |

| Never high exposure, ever medium exposure | 871 (55) | 2697 (59) |

| Never high exposure, never medium exposure | 67 (4) | 362 (8) |

| Missing | 6 | 6 |

Cases were to a higher extent blue-eyed with a very fair skin type, as is to be expected for cSCC as fair skin is a risk factor, and many more reported freckles after sun exposure (Table 3). More cases than controls stated that they had eczema during childhood. Cases were less prone to tan immediately after sun exposure; rather their skin burned to a higher extent, reflecting the higher proportion of participants with fair skin among cases. Cases were overrepresented in the high-risk category of the phenotypic risk index. 15% (n = 235) of the cases and 3% (n = 126) of the controls received immunosuppressive therapy before the index date.

Table 3.

Phenotypic characteristics of the cases and controls

| Cases, n (%) | Controls, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Natural eye colour | ||

| Blue | 883 (56) | 2143 (47) |

| Grey | 32 (2) | 138 (3) |

| Green | 138 (9) | 485 (11) |

| Yellow | 0 (0) | 5 (0.1) |

| Light brown | 73 (5) | 283 (6) |

| Dark brown | 88 (6) | 439 (10) |

| Mixed (green, blue, grey) | 369 (23) | 1000 (22) |

| Different coloured eyes | 6 (0.4) | 32 (0.7) |

| Missing | 11 | 26 |

| Natural skin tone | ||

| Very light | 192 (12) | 196 (4) |

| Light | 911 (58) | 2287 (51) |

| Medium | 461 (29) | 1890 (42) |

| Olive/light brown | 16 (1) | 100 (2) |

| Brown | 2 (0.1) | 35 (0.8) |

| Dark brown | 1 (0.1) | 5 (0.1) |

| Missing | 17 | 38 |

| Freckles after sun exposure | ||

| Yes, many | 274 (17) | 357 (8) |

| Yes, a few | 570 (36) | 1358 (30) |

| No, I don’t get freckles | 745 (47) | 2818 (62) |

| Missing | 11 | 18 |

| Skin reaction to first sun exposure | ||

| Burns (sometimes with blisters) and pain/sting for at least 48 h | 45 (3) | 79 (2) |

| Burns with pain/sting that disappears within 24 h | 596 (37) | 1163 (26) |

| Initially burns, then tans | 855 (54) | 2783 (62) |

| Tan immediately | 95 (6) | 494 (11) |

| Missing | 9 | 32 |

| Childhood eczema | ||

| Yes | 310 (20) | 754 (17) |

| No | 1108 (70) | 3241 (72) |

| I don’t know | 170 (11) | 527 (12) |

| Missing | 12 | 29 |

| Phenotypic risk index | ||

| High risk | 644 (40) | 1258 (28) |

| Medium risk | 885 (55) | 2890 (64) |

| Low risk | 69 (4) | 401 (9) |

| Missing | 2 | 2 |

| Immunosuppressive therapy | ||

| Yes | 235 (15) | 126 (3) |

| No | 1375 (85) | 4425 (97) |

The cases were slightly less tattooed than the controls (15% vs. 18%; Table 4). The median age at first tattoo was 30 years for both cases and controls, and the area of tattooed body surface and the choice of colours were similar. Cases stated that they sunbathed less after tattooing or covered their tattoos while sunbathing, to a higher extent than controls. The majority of cases (76%) and controls (84%) had not changed their tanning habits after getting tattooed.

Table 4.

Tattoo characteristics among tattooed cases and controls

| Tattoo characteristics | Cases, n (%) | Controls, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Tattoo | ||

| Yes | 236 (15) | 802 (18) |

| No | 1364 (85) | 3749 (82) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 |

| Tattoo type | ||

| Decorative | 220 (93) | 753 (94) |

| Cosmetic | 22 (9) | 53 (7) |

| Medical | 11 (5) | 30 (4) |

| Missing | 14 | 31 |

| Size of tattoo | ||

| >5 palm | 14 (6) | 52 (7) |

| 1—5 palms | 76 (32) | 262 (33) |

| < 1 palm | 146 (62) | 481 (60) |

| Missing | 0 | 7 |

| Colour of tattoo | ||

| Only black/grey | 81 (34) | 271 (34) |

| Both black/grey and colour | 107 (45) | 393 (49) |

| Only colour | 48 (20) | 135 (17) |

| Missing | 0 | 3 |

| Number of sessions | ||

| 1 | 100 (42) | 384 (48) |

| 2–3 | 88 (37) | 261 (33) |

| 4–5 | 28 (12) | 78 (10) |

| 6–9 | 9 (4) | 44 (6) |

| >=10 | 11 (5) | 29 (4) |

| Missing | 0 | 6 |

| Tattooist | ||

| Professional, studio | 192 (81) | 662 (83) |

| Professional, other facility | 31 (13) | 96 (12) |

| Cosmetic tattooist, in studio or clinic | 20 (8) | 38 (5) |

| Healthcare professional, in clinic | 12 (5) | 29 (4) |

| Nonprofessional, irrespective of location | 18 (8) | 72 (9) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 |

| Geographical regionb | ||

| Sweden | 203 (86) | 687 (86) |

| Nordics, except Sweden | 25 (11) | 91 (11) |

| Rest of Europe | 15 (6) | 48 (6) |

| Asia | 14 (6) | 39 (5) |

| Oceania | 2 (1) | 1 (0.001) |

| USA | 7 (3) | 17 (2) |

| Other | 3 (1) | 18 (2) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 |

| Changed tanning habits since first tattoo | ||

| Yes, I sunbathe more | 0 (0) | 5 (0.6) |

| Yes, I sunbathe less | 30 (13) | 51 (6) |

| Yes, I sunbathe as before, but cover tattooed skin or protect it with SPF* | 25 (11) | 75 (9) |

| No | 179 (76) | 669 (84) |

| Missing | 2 | 2 |

*Sun protection factor

Anatomical location of tattoos and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

Among 78% (n = 194) of the tattooed cases, we had information about the side and anatomical location of the malignancy. Among 23% of those cases, the tattoo was placed on the same anatomical location as the cancerous lesion, although not statistically correlated (Spearman’s rho = 0.04, p-value = 0.58).

Tattoos and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

We did not find an increased risk for cSCC among tattooed individuals. The point estimates did not indicate an increased risk (IRR = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.78–1.15; Table 5), but in unmatched analysis, they were suggestive of lower risk (IRR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.74–1.04) although the CI included 1. We did not find evidence of effect modification by UV exposure (overall P[interaction] = 0.65; Table S4). Neither did we find any evidence for effect modification by immunosuppressive drugs (overall P[interaction] = 0.47; Table S5), and we did not find any risk increase when adjusting for immunosuppressive drugs or for different exposure durations, or when including next-of-kin of deceased cases (Table 5 and Table S6).

Table 5.

Basic and fully adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRRs) of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in tattooed individuals relative to non-tattooed individuals

| Matched | Unmatched | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic adjustmenta | Fully adjustedb | Basic adjustmentc | Fully adjustedd | |||||||||

| Cases, n | Controls, n | IRR (95% CI) | Cases, n | Controls, n | IRR (95% CI) | Cases, n | Controls, n | IRR (95% CI) | Cases, n | Controls, n | IRR (95% CI) | |

| Main analyses | ||||||||||||

| Tattoo status | 1429 | 2609 | 1415 | 2595 | 1600 | 4551 | 1584 | 4526 | ||||

| Tattooed | 213 | 418 | 0.88 (0.74–1.06) | 211 | 414 | 0.95 (0.78–1.15) | 236 | 802 | 0.83 (0.71–0.97) | 234 | 798 | 0.88 (0.74–1.04) |

| Non-tattooed | 1216 | 2191 | 1.00 | 1204 | 2181 | 1.00 | 1364 | 3749 | 1.00 | 1350 | 3728 | 1.00 |

| Tattooed body surface | 1429 | 2607 | 1415 | 2593 | 1600 | 4544 | 1544 | 4519 | ||||

| Tattooed body surface > 1 palm | 79 | 145 | 0.92 (0.69–1.23) | 78 | 145 | 0.98 (0.72–1.34) | 90 | 314 | 0.82 (0.64–1.05) | 89 | 314 | 0.85 (0.66–1.10) |

| Tattooed body surface < 1 palm | 134 | 271 | 0.87 (0.70–1.09) | 133 | 267 | 0.93 (0.74–1.17) | 146 | 481 | 0.85 (0.70–1.03) | 145 | 477 | 0.88 (0.72–1.08) |

| Non-tattooed | 1216 | 2191 | 1.00 | 1204 | 218 | 1.00 | 1364 | 3749 | 1.00 | 1350 | 3728 | 1.00 |

| Ordinal exposure variable | 1429 | 2607 | 1415 | 2593 | 1600 | 4545 | 1584 | 4520 | ||||

| 1 tattoo session | 92 | 215 | 0.76 (0.59–0.98) | 92 | 211 | 0.83 (0.63–1.08) | 100 | 384 | 0.73 (0.58–0.92) | 100 | 380 | 0.77 (0.61–0.98) |

| 2–3 tattoo sessions | 80 | 133 | 1.06 (0.78–1.43) | 79 | 133 | 1.07 (0.78–1.47) | 88 | 261 | 0.95 (0.74–1.22) | 87 | 261 | 0.98 (0.76–1.27) |

| >4 tattoo sessions | 41 | 68 | 1.00 (0.67–1.49) | 40 | 68 | 1.12 (0.73–1.73) | 48 | 151 | 0.93 (0.66–1.29) | 47 | 151 | 1.02 (0.72–1.44) |

| Non-tattooed | 1216 | 2191 | 1.00 | 1204 | 2181 | 1.00 | 1364 | 3749 | 1.00 | 1350 | 3728 | 1.00 |

| Colour | 1429 | 2608 | 1415 | 2594 | 1600 | 4548 | 1584 | 4523 | ||||

| Black/grey | 71 | 138 | 0.90 (0.67–1.22) | 70 | 136 | 0.97 (0.71–1.33) | 81 | 271 | 0.86 (0.68–1.12) | 80 | 269 | 0.92 (0.70–1.20) |

| Black/grey + colour | 98 | 201 | 0.85 (0.66–1.10) | 97 | 199 | 0.91 (0.69–1.20) | 107 | 393 | 0.77 (0.61–0.96) | 106 | 391 | 0.80 (0.63-1.00) |

| Colour only | 44 | 78 | 0.96 (0.66–1.41) | 44 | 78 | 1.01 (0.67–1.51) | 48 | 135 | 0.96 (0.69–1.35) | 48 | 135 | 0.98 (0.69–1.38) |

| No tattoo | 1216 | 2191 | 1.00 | 1204 | 2181 | 1.00 | 1364 | 3749 | 1.00 | 1350 | 3728 | 1.00 |

| Exposure duration | 1424 | 2595 | 1410 | 2581 | 1594 | 4530 | 1578 | 4505 | ||||

| 0–5 years | 22 | 46 | 0.91 (0.54–1.53) | 22 | 46 | 0.90 (0.52–1.54) | 22 | 84 | 0.75 (0.47–1.21) | 22 | 84 | 0.78 (0.48–1.26) |

| 6–10 years | 21 | 40 | 0.94 (0.55–1.63) | 21 | 38 | 1.18 (0.67–2.10) | 22 | 92 | 0.70 (0.43–1.12) | 22 | 90 | 0.81 (0.50–1.31) |

| 11–15 years | 25 | 56 | 0.79 (0.48–1.29) | 25 | 56 | 0.85 (0.52–1.41) | 30 | 106 | 0.83 (0.55–1.25) | 30 | 106 | 0.84 (0.55–1.27) |

| > 15 years | 140 | 262 | 0.90 (0.72–1.12) | 138 | 260 | 0.96 (0.75–1.22) | 156 | 499 | 0.87 (0.72–1.06) | 154 | 497 | 0.92 (0.75–1.13) |

| Non-tattooed | 1216 | 2191 | 1.00 | 1204 | 2181 | 1.00 | 1364 | 3749 | 1.00 | 1350 | 3728 | 1.00 |

| Restriction: first ever diagnosis only | 1204 | 2609 | 1192 | 2595 | 1357 | 4551 | 1343 | 4526 | ||||

| Tattooed | 187 | 418 | 0.94 (0.77–1.15) | 185 | 414 | 1.04 (0.84–1.29) | 208 | 802 | 0.86 (0.73–1.02) | 206 | 798 | 0.92 (0.77–1.10) |

| Non-tattooed | 1017 | 2191 | 1.00 | 1007 | 2181 | 1149 | 3749 | 1.00 | 1137 | 3728 | 1.00 | |

| Sensitivity analysis: immunosuppressive drugs | 1429 | 2609 | 1415 | 2595 | 1600 | 4551 | 1584 | 4526 | ||||

| Tattooed | 213 | 418 | 0.88 (0.74–1.06) | 211 | 414 | 0.97 (0.79–1.20) | 236 | 802 | 0.83 (0.71–0.97) | 234 | 798 | 0.88 (0.74–1.04) |

| Non-tattooed | 1216 | 2191 | 1.00 | 1204 | 2181 | 1.00 | 1364 | 3749 | 1.00 | 1350 | 3728 | 1.00 |

aEstimates obtained from conditional regression models adjusted for sex and age.

bEstimates obtained from conditional regression models adjusted for age, sex, educational attainment, household disposable income, marital status, phenotypic risk index, UV-exposure index, and smoking.

cEstimates obtained from unconditional regression models adjusted for sex, age, and index year.

dEstimates obtained from unconditional regression models adjusted for age, sex, index year, educational attainment, household disposable income, marital status, phenotypic risk index, UV-exposure index, and smoking.

Discussion

In this study of tattoos as a possible risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma, we found no evidence of an association. In the unmatched analysis, we found that tattooed individuals had a slightly lower risk than non-tattooed individuals in contrast to our hypothesis that a tattoo could be a risk factor for cSCC. However, confidence intervals (CIs) were wide and included 1, and in combination with the matched results we interpret this as a null result.

We assumed that UV exposure was a confounder for the association between tattoo exposure and cSCC through an unmeasured common cause reflecting a general interest in one’s appearance. Moreover, we expected UV exposure to modify the effect of the association between tattoos and cSCC, because of the possible release of potentially carcinogenic aromatic amines from azo pigments in the tattoo when exposed to UV radiation [15, 16]. However, we found no evidence of UV exposure as an effect modifier of the association between tattoos and cSCC, but further investigation is warranted for this and other skin malignancies in settings with higher UV exposure, because of the relatively low level of UV exposure in our setting. The analysis using exposure duration as exposure confirmed that too short latency periods did not mask an association with cSCC. Excluding individuals with immunosuppressive therapy did not affect the results. 15% of cases versus 3% of controls were on immunosuppressive therapy, indicating that the case group may have worse overall health than controls; this perhaps explains why cases were tattooed to a lesser extent than controls. We did not find that the results changed when including next-of-kin, although they were very few. We can therefore not draw any conclusions on survivorship bias in this study. The robust effect estimate suggests that the results were not sensitive to analytical decisions.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to address tattoos as a risk factor for cSCC and it includes a large population-based sample with sufficient statistical power to detect associations; 51% of invited participants replied to the questionnaire. We have access to National Administrative Registers with full population coverage and valid data on both the outcome and sociodemographic confounders [46, 47]. Thus, we have a low risk of loss-to-follow up, and with that a low risk for information bias and a low risk for selection bias with respect to register data [48]. The access to registers also facilitates the study of rare outcomes, which would be more difficult in longitudinal cohort studies where the inclusion of enough cases is a limitation.

We found higher frequencies of conventional risk factors for cSCC among cases, such as high UV exposure and fair skin and we did not find this same pattern for tattoos.

To reduce the risk of selection bias, the study population was informed that the purpose of the study was to investigate associations between several lifestyle factors on multiple outcomes to avoid conditioning participation based on both exposure and outcome status. We consider the risk of recall bias regarding the exposure variable to be low. According to the dropout analysis, respondents were of higher SES and more often born in Sweden. Additionally, response rates were higher among cases than controls. As both lower SES and occupational UV exposure from bluecollar work likely are associated with a higher risk for cSCC as well as with a higher tattoo prevalence, our results may be an underestimation of the true effect. Making causal assumptions based on the results of one single study is premature and it remains to be seen if our results can be replicated by further research.

One limitation is that some of our data, including information about one confounding factor (UV exposure) are based on self-reported information. There is always a risk for recall bias, and in this study, there was a risk that cases over-reported their sun exposure because it is a well-known risk factor for cSCC. However, recall bias only seemed to have a minor effect on risk estimates in a large nested case-control study of skin cancer [49, 50]. The authors did find minor indications of recall bias but patterns were inconsistent, and they did not observe recall bias for sun bed use, and other UV radiation related exposures, the variables most relevant for the UV exposure index in the present study.

The proportion of deceased cases was low, and we therefore consider the risk of survivorship bias to be low. Nonetheless, we tried to avoid survivorship bias by including answers from relatives of deceased individuals; however, this analysis was of limited value due to a low participation rate among next-of-kin.

Our study focused on cSCC developing in mid-life. Thus, the results may not be generalizable to older populations because the risk factors may be different. In addition, we cannot generalize our results to more UV-intense regions of the world. Also, our cases and controls came from a Nordic country with limited variation in skin pigmentation. Populations with melanin-rich skin are not at high risk for developing UV-related cSCC; human papillomavirus is a bigger risk factor [51]. Hence, the association between tattoos and cSCC may be different in other populations with melanin-rich skin.

Conclusion

This study of tattoos as a risk factor for cSCC found no evidence of an association. However, more epidemiologic studies are needed before consensus regarding a lack of association can be reached. In addition, the results cannot be extrapolated to other malignancies and further research is warranted to clarify the role of tattoos as a risk factor for other cancer types.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Christel Nielsen and Anna Jöud; Methodology, Christel Nielsen, Anna Jöud and Emelie Rietz Liljedahl; Validation, Christel Nielsen, Anna Jöud and Emelie Rietz Liljedahl; Formal Analysis, Emelie Rietz Liljedahl.; Investigation, Emelie Rietz Liljedahl, Malin Engfeldt, Kari Nielsen, Christel Nielsen and Anna Jöud; Resources, Christel Nielsen; Data Curation, Emelie Rietz Liljedahl; Writing– Original Draft Preparation, Emelie Rietz Liljedahl; Writing– Review & Editing, Emelie Rietz Liljedahl, Kari Nielsen, Malin Engfeldt, Anna Jöud and Christel Nielsen; Visualization, Emelie Rietz Liljedahl; Supervision, Christel Nielsen and Anna Jöud; Project Administration, Emelie Rietz Liljedahl and Christel Nielsen; Funding Acquisition, Christel Nielsen.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lund University.

This research was funded by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE) grant number 2018 − 00864, the Crafoord foundation (20180659) and the Magnus Bergvall foundation (2018–02669).

Data availability

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and legal restrictions (GDPR). Data sharing is not possible.

Declarations

Ethical approval

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2019–03138, date of approval 2019-06-05).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Competing interests

The work was supported by research funding to CN from the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, The Crafoord Foundation, and Magnus Bergvalls Foundation, to KN from the Southern health care region, Sweden, the S.R. Gorthon foundation, the Welander Finsen foundation (Hudfonden), the LMK foundation, grants from the Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the county councils (the ALF agreement), the Inga and John Hain Foundation for medical research, and the Gyllenstiernska Krapperup Foundation. KN has received speaker honoraria from Galderma Sweden, LEO Pharma Sweden, Novartis Sweden and UCB Pharma Sweden. KN has 2021 served on one advisory board for Merck Sharp and Dohme (MSD), and finally KN is President of the Board for the National Melanoma Guidelines and President for the Swedish Society of Dermatological Surgery and Oncology. The authors declare no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cancerfonden. Statistik hudcancer [Skin cancer statistics]. 2023 Available from: https://www.cancerfonden.se/om-cancer/statistik/hudcancer (accessed 20 August 2023).

- 2.Socialstyrelsen. Socialstyrelsens statistikdatabas [Statisical databases]. 2021. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/en/statistics-and-data/statistics/statistical-databases/ (accessed 20 August 2023).

- 3.Waldman A, Schmults C. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33(1):1–12. 10.1016/j.hoc.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wassberg C, Thörn M, Johansson AM, Bergström R, Berne B, Ringborg U. Increasing incidence rates of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin in Sweden. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81(4):268–72. 10.1080/00015550152572903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kluger N, Seité S, Taieb C. The prevalence of Tattooing and motivations in five major countries over the world. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(12):e484–6. 10.1111/jdv.15808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folkhälsomyndigheten. Miljöhälsorapport 2017 [Environmental health report 2017]. 2017. Available from: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/contentassets/c44fcc5df7454b64bf2565454bbdf0e3/miljohalsorapport-2017-02096-2016-webb.pdf (accessed 5 September 2023).

- 7.Nielsen C, Andréasson K, Olsson H, Engfeldt M, Jöud A. Cohort profile: the Swedish tattoo and body modifications cohort (TABOO). BMJ Open. 2023;13(5):e069664. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-069664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaeffer K, Dinesh S. 32% of Americans have a tattoo, including 22% who have more than one. 2023. Available from: https://pewrsr.ch/3QFg5w1 (accessed 5 September 2023).

- 9.Sagoe D, Pallesen S, Andreassen CS. Prevalence and correlates of Tattooing in Norway: a large-scale cross-sectional study. Scand J Psychol. 2017;58(6):562–70. 10.1111/sjop.12399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barton DT, Zens MS, Marmarelis EL, Gilbert-Diamond D, Karagas MR. Cosmetic Tattooing and early onset basal cell carci-noma: a population-based case-control study from new Hampshire. Epidemiology. 2020;31(3):448–50. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobsen NR, Clausen PA. Carbon black nanoparticles and other problematic constituents of black ink and their potential to harm tattooed humans. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:170–5. 10.1159/000369319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Some non-heterocyclic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and some related exposures, IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans volume 92. Lyon; IARC; 2010. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Some aromatic amines, organic dyes, and related exposures. IARC monographs on the evaluations of carcinogenic risks to humans volume 99. Lyon: IARC; 2010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawakami T, Obama T, Tahara M, Ikarashi Y. Determination of carcinogenic primary aromatic amines contained as impurities in synthetic organic colorants. J AOAC Int. 2022;106(1):49–55. 10.1093/jaoacint/qsac095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vasold R, Naarmann N, Ulrich H, Fischer D, König B, Landthaler M, et al. Tattoo pigments are cleaved by laser light-the chemical analysis in vitro provide evidence for hazardous compounds. Photochem Photobiol. 2004;80(2):185–90. 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2004.tb00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engel E, Vasold R, Santarelli F, Maisch T, Gopee NV, Howard PC, et al. Tattooing of skin results in transportation and light-induced decomposition of tattoo pigments–a first quantification in vivo using a mouse model. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19(1):54–60. 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Carbon black, titanium dioxide, and Talc. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans volume 93. Lyon; IARC; 2010. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Petersen H, Lewe D. Chemical purity and toxicology of pigments used in tattoo inks. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:136–41. 10.1159/000369647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manso M, Pessanha S, Guerra M, Reinholz U, Afonso C, Radtke M, et al. Assessment of toxic metals and hazardous substances in tattoo inks using Sy-XRF, AAS, and Raman spectroscopy. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2019;187(2):596–601. 10.1007/s12011-018-1406-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bocca B, Senofonte O, Petrucci F. Hexavalent chromium in tattoo inks: dermal exposure and systemic risk. Contact Dermat. 2018;79(4):218–25. 10.1111/cod.13051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Chromium, nickel and welding. IARC Mono-graphs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Volume 49. Lyon, IARC: 1990. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Wang X, Josefsson L, Meschnark S, Lind ML, Emmer Å, Goessler W, et al. Analytical survey of tattoo inks - a chemical and legal perspective with focus on sensitizing substances. Contact Dermat. 2021;85(3):340–53. 10.1111/cod.13913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niederer M, Hauri U, Kroll L, Hohl C. Identification of organic pigments in tattoo inks and permanent make-up using laser desorption ionisation mass spectrometry. F1000Res. 2017;6:2034. 10.12688/f1000research.13035.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nielsen C, Jerkeman M, Jöud AS. Tattoos as a risk factor for malignant lymphoma: a population-based case–control study. eClinicalMedicine. 2024;72:102649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clemmensen SB, Mengel-From J, Kaprio J, Frederiksen H, Von Bornemann Hjelmborg J. Tattoo ink exposure is associated with lymphoma and skin cancers– a Danish study of twins. BMC Public Health. 2025;25(1):170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bose R, Sibley C, Fahim S. Granulomatous and systemic inflammatory reactions from tattoo ink: case report and concise review. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2020;8:2050313x20936036. 10.1177/2050313x20936036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Labrecque JA, Hunink MMG, Ikram MA, Ikram MK. Do Case-Control studies always estimate odds ratios?? Am J Epidemiol. 2021;190(2):318–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leiter U, Eigentler T, Garbe C. Epidemiology of skin cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;810:120–40. 10.1007/978-1-4939-0437-2_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmitt J, Haufe E, Trautmann F, Schulze HJ, Elsner P, Drexler H, et al. Is ultraviolet exposure acquired at work the most important risk factor for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma? Results of the population-based case–control study FB-181. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(2):462–72. 10.1111/bjd.15906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Westerdahl J, Anderson H, Olsson H, Ingvar C. Reproducibility of a self-administered questionnaire for assessment of melanoma risk. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25(2):245–51. 10.1093/ije/25.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jorgenson E, Choquet H, Yin J, Hoffmann TJ, Banda Y, Kvale MN, et al. Genetic ancestry, skin pigmentation, and the risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in Hispanic/Latino and non-Hispanic white populations. Commun Biol. 2020;3(1):765. 10.1038/s42003-020-01461-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124(6):869–71. 10.1001/archderm.1988.01670060015008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corazza M, Ferretti S, Scuderi V, Borghi A. Socioeconomic status and skin cancer incidence: a population-based, cohort study in the Province of Ferrara, Northern Italy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46(7):1285–9. 10.1111/ced.14599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Azimi S, Rafieian N, Manifar S, Ghorbani Z, Tennant M, Kruger E. Socioeconomic determinants as risk factors for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a case-control study in Iran. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;56(4):304–9. 10.1016/j.bjoms.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alfonso JH, Martinsen JI, Pukkala E, Weiderpass E, Tryggvadottir L, Nordby KC, et al. Occupation and relative risk of cu-taneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC): a 45-year follow-up study in 4 nordic countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(3):548–55. 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borkenhagen A, Mirastschijski U, Petrowski K, Brähler E. [Tattoos in Germany: prevalence, demographics, and health ori-entation]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2019;62(9):1077–82. 10.1007/s00103-019-02999-7. [in German]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kluger N. Epidemiology of tattoos in industrialized countries. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:6–20. 10.1159/000369175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orzan OA, Popa LG, Vexler ES, Olaru I, Voiculescu VM, Bumbăcea RS. Tattoo-induced psoriasis. J Med Life. 2014;7(2):65–8. Spec 2(Spec Iss. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pouplard C, Brenaut E, Horreau C, Barnetche T, Misery L, Richard MA, et al. Risk of cancer in psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(Suppl 3):36–46. 10.1111/jdv.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seviiri M, Law MH, Ong JS, Gharahkhani P, Nyholt DR, Olsen CM, et al. Polygenic risk scores allow risk stratification for keratinocyte cancer in organ-transplant recipients. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141(2):325–e3336. 10.1016/j.jid.2020.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cehajic A, Petterson D, Frisell T. Bortfall i cancerregistret vid jämförelse med dödsorsaksintyg [Losses in the cancer register when compared with cause of death certificates]. 2021. Available from; https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/statistik/2021-9-7530.pdf (accessed 01 Nov 2023).

- 42.Socialstyrelsen. Bortfall och kvalitet om cancerregistret [Loss and quality of the cancer registry]. 2023. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik-och-data/register/cancerregistret/bortfall-och-kvalitet/ (accessed 01 Nov 2023).

- 43.Pearce N. Analysis of matched case-control studies. BMJ. 2016;352:i969. 10.1136/bmj.i969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuo CL, Duan Y, Grady J. Unconditional or conditional logistic regression model for age-matched case-control data? Front Public Health. 2018;6:57. 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheung YB, Ma X, Lam KF, Li J, Milligan P. Bias control in the analysis of case-control studies with incidence density sampling. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(6):1981–91. 10.1093/ije/dyz116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy AK, Ljung R, Michaëlsson K, Neovius M, et al. Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(2):125–36. 10.1007/s10654-016-0117-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish National inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Howe CJ, Cole SR, Lau B, Napravnik S, Eron JJ Jr. Selection bias due to loss to follow up in cohort studies. Epidemiology. 2016;27(1):91–7. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parr CL, Hjartåker A, Laake P, Lund E, Veierød MB. Recall bias in melanoma risk factors and measurement error effects: a nested case-control study within the Norwegian women and cancer study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(3):257–66. 10.1093/aje/kwn363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gefeller O. Invited commentary: Recall bias in melanoma -- much ado about almost nothing? Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(3). 10.1093/aje/kwn362. 267– 70;discussion 271-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Nadhan KS, Chung CL, Buchanan EM, Shaver C, Shipman S, Allawh RM, et al. Risk factors for keratinocyte carcinoma skin cancer in nonwhite individuals: a retrospective analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(2):373–8. 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and legal restrictions (GDPR). Data sharing is not possible.