Abstract

Background: Physician burnout has become a critical issue in healthcare, particularly among emergency medicine physicians, who face unique stressors that can compromise their well-being and quality of life. This study investigates the relationship between burnout and quality of life in emergency medicine physicians and how these factors influence their intent to remain in practice. Methods: In August 2024, a survey was distributed to 103 emergency physicians to assess burnout using the Maslach Burnout Inventory and quality of life using the World Health Organization Quality of Life—BREF survey. Demographic information and intentions regarding their continued practice in emergency medicine were also collected. Statistical analyses, including independent samples t-test, Pearson’s correlation and multiple regression, were performed to examine relationships among variables. Results: Most respondents (77.7%) were identified as being at high risk for burnout. Most physicians reported a high quality of life despite significant burnout rates, with the lowest score being psychological health (M = 66.24, SD = 18.97) while the highest being physical health (M = 76.06, SD = 13.38). There was a statistically significant association between all burnout domains and the quality of life subgroups. Emotional exhaustion showed a strong negative correlation with psychological health (r = −0.634, P < 0.01) and social relationships (r = −0.358, P < 0.01). At the same time, personal accomplishment correlated positively with both psychological health (r = 0.525, P < 0.01) and social relationships (r = 0.317, P < 0.01). A statistically significant negative correlation existed between emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and the physician’s years of intended practice (r = −.127, P = .010). Using multiple linear regression, physical and psychological health significantly predicted emotional exhaustion and psychological health significantly predicted depersonalization. Conclusion: This study highlights the high prevalence of burnout among emergency medicine physicians and its significant impact on their quality of life and professional intentions. Furthermore, physical and psychological quality of life substantially influences emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. The findings underscore the need for comprehensive interventions to address burnout and enhance well-being in this demanding specialty to promote retention and improve patient care.

Keywords: physician burnout, quality of life, career longevity

“Quality of life was evaluated across four primary domains: physical health, psychological well-being, social relationships, and environmental factors.”

Introduction

Burnout and diminished quality of life (QOL) have become pervasive concerns within the medical profession, significantly impacting not only physicians but also the broader healthcare system, including patient care and institutional efficiency. 1 Physicians are increasingly confronted with various occupational stressors that exacerbate the imbalance between professional responsibilities and their ability to recover from work-related stress. 2 This imbalance has contributed to the growing prevalence of physician burnout, a syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a diminished sense of personal achievement. 3

The consequences of burnout extend beyond individual physicians, leading to increased medical errors, decreased clinical productivity, lower quality of patient care, and reduced patient satisfaction. Moreover, burnout contributes to physician workload reduction, early retirement, and an increasing trend of professionals leaving the medical field.4,5 The escalating burden of burnout necessitates a comprehensive understanding of its underlying causes and potential interventions to mitigate its impact on healthcare delivery and physician well-being.

The Interrelationship Between Quality of Life and Burnout

Low QOL is closely intertwined with burnout, functioning both as a contributing factor and a consequence.5,6 Physicians frequently encounter personal and professional stressors that negatively affect life satisfaction, including prolonged working hours, inadequate sleep, emotional and physical exhaustion, holiday and weekend shifts, and the disruption of occupational, social and familial relationships.5,7-9 The high-pressure nature of medical practice, where decisions often have life-or-death consequences, further exacerbates these stressors. As a result, the same factors that deteriorate physicians’ QOL simultaneously serve as catalysts for burnout.

Among all medical specialties, emergency medicine (EM) physicians are particularly vulnerable to burnout due to the demanding nature of their work, frequent night and weekend shifts, and exposure to high-acuity patients in chaotic and unpredictable environments. Emergency physicians must continuously make rapid clinical decisions while managing critically ill or injured patients, creating significant physical and emotional strain. Recent studies indicate that up to 62% of EM physicians experience burnout, making it one of the most affected specialties. 10

Interestingly, despite high burnout rates, some emergency physicians report high job satisfaction and a positive perception of their QOL. 7 This apparent paradox suggests that mitigating factors—such as strong social support networks, a sense of purpose, and perceived work-life balance—may help buffer the negative effects of burnout. 11 Burnout is a multidimensional construct, where physicians may experience high personal accomplishment yet simultaneously struggle with emotional exhaustion. Consequently, an in-depth examination of the specific components of burnout and QOL is necessary to develop targeted interventions that enhance physician well-being.

The Bidirectional Influence of Burnout and Lifestyle

Physician burnout and lifestyle factors are deeply interconnected, with each influencing the other in significant ways. Burnout is frequently driven by demanding schedules, high-stakes decision-making, and the emotional toll of patient care. 5 These work-related demands limit opportunities for essential lifestyle habits, including regular exercise, adequate sleep, and proper nutrition. 12 The resulting lifestyle compromises exacerbate burnout by heightening stress levels, reducing resilience, and impairing overall physical and mental health. 13

Conversely, a healthy lifestyle has been shown to mitigate burnout by enhancing emotional resilience, improving energy levels, and promoting psychological well-being. For example, regular physical activity lowers cortisol levels, improves mood regulation, and enhances sleep quality, all of which serve as protective factors against burnout. 14 However, despite the well-documented benefits of self-care, many physicians struggle to prioritize these behaviors due to professional obligations, long working hours, and a medical culture that undervalues work-life balance. 15 This dynamic creates a self-perpetuating cycle in which poor lifestyle habits exacerbate burnout symptoms, further hindering physicians’ ability to engage in self-care practices.

To break this cycle, systemic changes are required within medical institutions. These changes include prioritizing wellness programs, fostering supportive work environments, and actively promoting healthy behaviors. By addressing lifestyle factors, physicians can develop greater resilience against burnout, ensuring career longevity and professional fulfillment.

Distinguishing Between Burnout and Quality of Life

Although closely related, burnout and QOL are generally described as distinct constructs. Burnout primarily arises from chronic occupational stress, whereas QOL encompasses a broader framework of personal well-being, including physical, emotional, social, and psychological domains. 16 Notably, physicians may experience high burnout yet still report good QOL, owing to effective coping mechanisms or external factors that enhance life satisfaction. Conversely, a poor QOL may contribute to burnout, further eroding professional fulfillment and personal well-being.

One of the most significant components of QOL is psychological well-being, which strongly influences emotional engagement in the workplace. Physicians with high stress levels, anxiety, or depression are more likely to experience emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, leading to detachment and cynicism toward patients and colleagues.3,5 Given the emotional intensity of medical practice, physicians who struggle with psychological distress are more susceptible to disengagement, increasing the risk of professional dissatisfaction and burnout. 5

In contrast, a high psychological QOL serves as a protective factor by enhancing emotional resilience, promoting adaptive coping strategies, and fostering sustained workplace engagement. Physicians who maintain strong psychological well-being are better equipped to handle stressors and manage difficult patient interactions. 12 Emotional resilience enables physicians to preserve empathy and maintain professional dedication, even in high-stress environments. 5 Implementing targeted interventions to strengthen psychological QOL is thus essential for reducing depersonalization and improving physician job satisfaction.

Depersonalization, a core component of burnout, manifests as emotional detachment and cynicism toward patients and colleagues, often developing as a maladaptive response to chronic occupational stress. 17 While depersonalization can provide temporary psychological relief, prolonged detachment is associated with increased physician burnout, lower job satisfaction, and diminished quality of life. 18 The relationship between depersonalization, burnout, and QOL is bidirectional—physicians experiencing poor psychological well-being and excessive workload often resort to depersonalization as a coping mechanism. At the same time, persistent detachment further exacerbates occupational dissatisfaction and reduces overall life satisfaction. 5

This conceptual framework identifies four physician subgroups to illustrate how depersonalization interacts with burnout and QOL. The vulnerable group (high burnout, low QOL) struggles with emotional exhaustion, heavy workloads, and reduced professional fulfillment, increasing turnover risk. 19 The resilient group (high burnout, high QOL) experiences workplace stress yet maintains life satisfaction through resilience, social support, and work-life balance. The disengaged group (low burnout, low QOL) avoids burnout but struggles with work disengagement, personal dissatisfaction, or economic stress. Lastly, the optimal group (low burnout, high QOL) represents physicians with strong professional fulfillment, balanced workloads, and psychological resilience. 19

The interaction between burnout and quality of life (QOL) among physicians is complex, with some individuals exhibiting high burnout yet maintaining high QOL. In contrast, others demonstrate low burnout but poor QOL.3,18 Physicians who report high burnout but maintain high QOL often rely on intrinsic motivation, strong coping mechanisms, and social support to sustain their well-being. Their sense of purpose in patient care, emotional resilience, and structured recovery periods help buffer the negative effects of burnout, allowing them to find fulfillment despite occupational stress.20,21 Conversely, physicians with low burnout but low QOL may avoid professional exhaustion but struggle with social isolation, work disengagement, health neglect, and financial strain, ultimately leading to diminished well-being.5,22 These findings challenge the traditional assumption that burnout and QOL correlate directly, underscoring the need for multidimensional, personalized interventions. 19

The Challenge of Burnout Interventions

Efforts to mitigate physician burnout have faced significant challenges, with burnout rates continuing to rise despite institutional initiatives. Many workplace-focused interventions, such as reducing administrative burdens, increasing staffing levels, and promoting work-life balance, have demonstrated limited success in reversing burnout trends. This suggests that a more comprehensive, multifaceted approach is required—one that not only addresses external workplace stressors but also prioritizes internal resilience-building strategies, such as mindfulness training, psychological well-being programs, and personal development initiatives.23,24

Furthermore, the implications of burnout and low QOL extend beyond individual well-being, affecting healthcare institutions and patient care. Physician disengagement, reduced professional commitment, and increased intent to leave clinical practice are directly linked to high burnout rates. 25 Given the global physician shortage, these workforce challenges exacerbate staffing difficulties, increase patient wait times, and reduce overall healthcare quality.

Emergency medicine is particularly affected by physician retention issues, as the specialty is characterized by high attrition rates and workforce shortages. Studies indicate that female physicians in EM are at an even greater risk of burnout and work-life imbalance, leading to higher rates of career dissatisfaction and exit from the field. 26 These findings emphasize the urgent need for tailored interventions that specifically address burnout in high-risk medical specialties.

Burnout and diminished QOL remain critical challenges in the medical profession, significantly impacting physicians, patients, and healthcare institutions. The interrelationship between burnout, lifestyle behaviors, and psychological well-being underscores the need for targeted, evidence-based interventions. Addressing burnout requires systemic workplace reforms, including workload management, enhanced institutional support, and policy-driven wellness initiatives. Simultaneously, physicians must be empowered to prioritize self-care, cultivate resilience, and engage in health-promoting behaviors.

By adopting a multidimensional approach that integrates both institutional and personal well-being strategies, the medical community can effectively mitigate burnout, enhance physician quality of life, and improve long-term healthcare outcomes.

Therefore, this study seeks to investigate the relationship between burnout and quality of life among emergency medicine physicians and examine how these variables influence their intent to leave their current practice. While extensive research has been conducted on burnout and quality of life in various medical specialties, there is a notable gap in the literature regarding how these factors interact specifically within the field of emergency medicine. Addressing this knowledge gap is crucial for developing effective strategies to improve physician well-being, enhance career satisfaction, and reduce attrition within this critical medical specialty.

Methods

Study Design

In August 2024, 103 emergency physicians were recruited through various channels, including email, word of mouth, social media, and text messaging, to participate in a quantitative, cross-sectional, survey-based study. The primary aim of this study was to assess the relationship between burnout and quality of life among emergency physicians. After obtaining informed consent, participants provided demographic information such as age, gender, weekly work hours, years in practice, and the number of years they intend to remain in their current occupational setting.

To evaluate participants’ perceptions of occupational stress, they were asked to complete the Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel (MBI-HSS MP). 27 This survey includes 22 items designed to assess the dimensions of burnout, specifically emotional exhaustion (EE), professional accomplishment (PA), and depersonalization (DP). Responses were recorded using a Likert scale ranging from zero to six, where zero represents “never” and six signifies “every day.” The total scores for EE, DP, and PA were calculated, and participants were classified as being at high risk for burnout based on standard criteria (EE score ≥ 27, DP score ≥ 10, and PA score < 33).3,28

Participants also completed the World Health Organization Quality of Life – BREF (WHOQOL-BREF), a validated, self-administered questionnaire comprising 26 items. This instrument assesses individuals’ perceptions of their health and well-being over the preceding two weeks. The survey evaluates four domains of wellness: physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environmental factors. Two additional questions inquire about participants' overall perception of their health and quality of life.29,29 Responses were recorded on a Likert scale, where a score of one indicates “disagree” or “not at all,” and a score of five means “completely agree” or “extremely.” The psychometric properties of the WHOQOL-BREF have been extensively validated across various populations, including healthcare professionals. 29 It is derived from the longer 100-item WHOQOL survey. It is instrumental in studies requiring a brief evaluation of quality of life, especially among healthcare personnel. 16 Standardized scoring procedures outlined in the WHOQOL manual were used to convert responses into a 0-100 scale. A score of 0-45 is classified as low quality of life, 46-65 as moderate, and above 65 as high quality of life. 29

Data was collected electronically via Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Upon completion, the data was securely transferred to IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 29.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) for analysis. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables, including means, medians, standard deviations, and frequencies. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to evaluate the strength of the associations between quality of life and the individual domains of burnout (EE, DP, and PA). Additionally, Pearson correlations were employed to assess the relationship between burnout, quality of life, and physicians’ intended duration of practice in emergency medicine. Multiple regression analyses were conducted to determine the relative influences of the dimensions of quality of life on each burnout domain.

All data were anonymized, kept confidential, and stored in a password-protected environment. The study protocol received approval from the Institutional Review Board at Concordia University Chicago, ensuring that the study complied with ethical guidelines for human subject research.

Results

One hundred and three emergency medicine physicians completed the survey. The response rate is unknown due to the recruiting method used, primarily with social media posts and indirect requests for participation, and all responses being anonymous and confidential.

Participant Demographics

Approximately half (51.5%) of the survey respondents were male, with an average age of 43. Many participants were married (83.5%), 11% were never married, and 3.9% divorced. Nineteen percent of the physicians had practiced less than five years, with the most significant portion (28.2%) practicing 6-10 years and 16.5% having practiced for more than 20 years. Forty-five percent of the physicians worked between 31-40 h weekly, 36.9% worked less than 30 h weekly, and 16.7% worked greater than 40 h per week (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants.

| n | % | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n = 103) | 103 | 100 | ||

| Male | 53 | 51.5 | ||

| Female | 50 | 48.5 | ||

| Marital Status (n = 102) | 102 | |||

| Married | 86 | 83.5 | ||

| Widowed | 1 | 1.0 | ||

| Divorced | 4 | 3.9 | ||

| Never married | 11 | 10.7 | ||

| Age (years) (n = 91) | 91 | 43.50 | 7.516 | |

| <35 | 11 | 10.7 | ||

| 36-40 | 27 | 26.2 | ||

| 41-45 | 20 | 19.4 | ||

| 46-50 | 16 | 15.5 | ||

| >51 | 17 | 16.5 | ||

| Years in practice (n = 103) | 103 | 12.77 | 7.884 | |

| <5 | 20 | 19.4 | ||

| 6-10 | 29 | 28.2 | ||

| 11-15 | 21 | 20.4 | ||

| 16-20 | 16 | 15.5 | ||

| >20 | 17 | 16.5 | ||

| Hrs worked weekly (n = 103) | 103 | 35.12 | 11.026 | |

| <30 | 38 | 36.9 | ||

| 31-40 | 47 | 45.6 | ||

| >41 | 17 | 16.5 |

Physician Burnout

Of the 103 emergency physicians surveyed, 55.4% met the criteria for high emotional exhaustion (47.2% for males and 64.0% for females) (Table 2). An equal number of men and women met the criteria for high on the depersonalization scale, 66.0% and 69.0%, respectively. Physicians scored somewhat better on personal accomplishment, with 43.4% of men and 28% of women registering low levels of personal accomplishment. In total, 77.7% of surveyed participants met at least one criterion for physician burnout.

Table 2.

Emergency Physician Burnout.

| Burnout sub-scores | Total | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Emotional Exhaustion | 103 (M = 29.5, SD = 13.07) | 53 | 50 |

| Low | 23 (22.3) | 16 (30.2) | 7 (14.0) |

| Intermediate | 23 (22.3) | 12 (22.6) | 11 (22.0) |

| High | 57 (55.4) | 25 (47.2) | 32 (64.0) |

| Depersonalization | 103 (M = 13.95, SD = 7.34) | 53 | 50 |

| Low | 15 (14.6) | 8 (15.1) | 7 (14.0) |

| Intermediate | 19 (18.4) | 10 (18.9) | 9 (18.0) |

| High | 69 (67.0) | 35 (66.0) | 34 (68.0) |

| Personal Accomplishment | 103 (M = 36.89, SD = 6.47) | 53 | 50 |

| Low | 37 (35.9) | 23 (43.4) | 14 (28.0) |

| Intermediate | 36 (35.0) | 18 (34.0) | 18 (36.0) |

| High | 30 (29.1) | 12 (22.7) | 18 (36.0) |

Of the physicians meeting the criteria for high levels of burnout, women were more likely to report high levels of emotional exhaustion with an odds ratio of 1.991 (95% CI, .904 to 4.388). Age was less of a factor, with no significant correlation between chronological age and emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment (r = .063, P = .552; r = −.161, P = .127; r = .116, P = 272). The highest percentage of burnout occurred in physicians under 35 years old and those who worked more than 41 h per week (Table 3).

Table 3.

Emergency Physician With High Levels of Burnout by Demographic.

| Emotional exhaustion | Depersonalization | Personal accomplishment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Total | 57 (55.3) | 69 (67.0) | 30 (29.1) |

| Gender (n = 103) | |||

| Male | 25 (47.0) | 35 (66.0) | 12 (22.6) |

| Female | 32 (64.0) | 34 (68.0) | 18 (36.0) |

| Age (n = 91) | |||

| <35 | 8 (72.7) | 10 (90.9) | 7 (63.6) |

| 36-40 | 12 (44.4) | 21 (77.8) | 9 (33.3) |

| 41-45 | 11 (55.0) | 13 (65) | 2 (10.0) |

| 46-50 | 10 (62.5) | 11(68.8) | 7 (43.8) |

| >51 | 11 (64.7) | 7 (41.2) | 2 (11.8) |

| Years in practice (n = 103) | |||

| <5 | 10 (50) | 17 (85.0) | 8 (40.0) |

| 6-10 | 18 (62.1) | 21 (72.4) | 10 (34.5) |

| 11-15 | 10 (47.6) | 15 (71.4) | 5 (23.8) |

| 16-20 | 9 (56.3) | 9 (56.3) | 5 (31.3) |

| >20 | 10 (58.8) | 7 (41.2) | 2 (11.8) |

| Hrs worked weekly (n = 103) | |||

| <30 | 19 (50.0) | 27 (71.1) | 11 (28.9) |

| 31-40 | 26 (55.3) | 30 (63.8) | 13 (27.7) |

| >41 | 12 (70.6) | 12 (70.6) | 5 (29.4) |

Physician Quality of Life

Overall, emergency medicine physicians have a high quality of life. Over three-quarters of physicians rated their QOL in the physical domain to be high (Table 4). Similarly, they also rated their environmental quality of life high, with 87.9% scoring within the upper tier. The lowest score as a group was psychological health (M = 66.24, SD = 18.97), with female physicians fairing slightly worse than males (M = 64.76, SD = 14.35 vs M = 69.31, SD = 16.7). The lowest percentage of physicians meeting a high quality of life was in social relationships (57.1%). Age had no association with any of the domains of quality of life (physical - r = −.122, P = .262; psychological – r = .054, P = .619; social – r = −.098, P = .413; environmental – r = −.278, P = .278; overall – r = −.029, P = .789). Similarly, the number of hours worked weekly had no statistically significant association with the varied domains of quality of life (physical – r = .091, P = .376; psychological – r = −.046, P = .656; social – r = −.186, P = .068; environmental – r = −.186, P = .491; overall – r = −.011, P = .914).

Table 4.

Emergency Physician Quality of Life.

| Quality of Life sub-scores | Total | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Physical health | 98 (M = 76.06, SD = 13.38) | 52 (M = 77.47, SD = 13.81) | 46 (M = 74.45, SD = 12.84) |

| Low | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) |

| Moderate | 23 (23.5) | 13 (25) | 10 (21.7) |

| High | 74 (75.5) | 39 (75) | 35 (76.1) |

| Psychological health | 95 (M = 67.18, SD = 15.76) | 49 (M = 69.31, SD = 16.7) | 46 (M = 64.76, SD = 14.35) |

| Low | 8 (8.4) | 4 (8.2) | 4 (8.7) |

| Moderate | 32 (33.7) | 12 (24.5) | 20 (43.5) |

| High | 55 (57.9) | 33 (67.3) | 32 (69.5) |

| Social Relationships | 98 (M = 66.24, SD = 18.97) | 52 (M = 67.15, SD = 18.11) | 46 (M = 65.21, SD = 20.05) |

| Low | 12 (12.2) | 4 (7.7) | 8 (17.4) |

| Moderate | 30 (30.1) | 18 (34.6) | 12 (26.1) |

| High | 56 (57.1) | 30 (57.7) | 26 (56.5) |

| Environmental Health | 91 (M = 78.73, SD = 13.66) | 49 (M = 79.10, SD = 14.61) | 42 (M = 78.32, SD = 12.65) |

| Low | 2 (2.2) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.4) |

| Moderate | 9 (9.9) | 6 (12.2) | 3 (7.1) |

| High | 80 (87.9) | 42 (85.7) | 38 (90.5) |

Burnout and Quality of Life Correlation

There was a statistically significant correlation across all domains of burnout with all domains of quality of life (Table 5). There was a negative correlation between emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and all four domains of quality of life, suggesting that as the quality of life went up, burnout went down, or as emotional exhaustion and depersonalization went up, quality of life went down. There was a significant positive correlation with personal accomplishment across all domains of QOL, suggesting that as quality of life went up, personal accomplishment also went up, or as personal accomplishment went up, quality of life went up.

Table 5.

Pearson Correlations of Burnout and Quality of Life Domains.

| Emotional exhaustion | Depersonalization | Personal accomplishment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Health | r = −.548, P < .001* | r = −.383, P < .001* | r = .454, P < .001* |

| Psychological Health | r = −.641, P < .001* | r = −.486, P < .001* | r = .528, P < .001* |

| Social Relationships | r = −.419, P < .001* | r = −.355, P < .001* | r = .239, P = .018* |

| Environmental Health | r = −.440, P < .001* | r = −.231, P = .022* | r = .394, P < .001* |

| Overall | r = −.496, P < .001* | r = −.356, P < .001* | r = .342, P < .001* |

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

A multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine the effect of the four domains of quality of life on the three dimensions of burnout: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment. The model predicting emotional exhaustion was significant, F = 20.654, P < .001, with an R2 of .470, indicating that 47% of the variance in emotional exhaustion could be explained by the four domains of quality of life (Table 6). The model predicting depersonalization was also significant, F = 9.159, P < .001, with an R2 of .283, showing that the model accounted for 28.3% of the variance in depersonalization. Additionally, the model predicting personal accomplishment was significant, F = 10.351, P < .001, with an R2 of .308, explaining 30.8% of the variance in personal accomplishment. These findings suggest that the domains of quality of life significantly impact various facets of burnout among the sample (Table 6).

Table 6.

Multiple Regressions for Physician Burnout and Quality of Life.

| 95% CI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | Lower | Upper | β | P | |

| Dependent Variable: Emotional Exhaustion | ||||||

| Physical | −.300 | .096 | −.491 | −.109 | −.314 | .002* |

| Psychological | −.350 | .098 | −.545 | −.156 | −.433 | <.001* |

| Social | −.064 | .062 | −.187 | .060 | −.095 | .307 |

| Environmental | .064 | .098 | −.132 | .259 | .068 | .519 |

| Dependent Variable: Depersonalization | ||||||

| Physical | −.099 | .065 | −.227 | .028 | −.182 | .125 |

| Psychological | −.206 | .065 | −.335 | −.076 | −.444 | .002* |

| Social | −.055 | .041 | −.138 | .027 | −.144 | .184 |

| Environmental | .124 | .066 | −.006 | .254 | .232 | .061 |

| Dependent Variable: Personal Accomplishment | ||||||

| Physical | .090 | .055 | −.020 | .199 | .188 | .199 |

| Psychological | .176 | .056 | .064 | .287 | .433 | .287 |

| Social | −.030 | .036 | −.101 | .040 | −.090 | .040* |

| Environmental | .019 | .056 | −.093 | .130 | .040 | .130 |

*Significant at the 0.05 level.

In this analysis, only physical and psychological health significantly predict emotional exhaustion, both with negative effects (Table 6). Social and environmental health factors do not significantly affect emotional exhaustion in this model. Only psychological health significantly predicts depersonalization, with a notable negative effect. In this analysis, physical, social, and environmental health does not show significant relationships with depersonalization. Only social health shows a statistically significant impact on personal accomplishment, with a weak negative relationship. In this model, physical, psychological, and environmental health do not significantly affect personal accomplishment.

Physician Burnout and Intent to Practice

All domains of burnout affected the physician’s intent to practice (Table 7). A statistically significant negative correlation existed between emotional exhaustion and the physician’s years of intended practice (r = −.127, P = .010). Similarly, a significant negative relationship existed between depersonalization and years of intended practice (r = −.230, P = .020). Personal accomplishment had a statistically significant positive relationship with years of intended practice (r = .391, P < .001).

Table 7.

Pearson Correlations of Intent to Practice and Physician Burnout.

| Emotional exhaustion | Depersonalization | Personal accomplishment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intent to practice (years) | r = −.127, P = .010* | r = −.230, P = .020* | r = .391, P < .001* |

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Physician Quality of Life and Intent to Practice

There was a statistically significant negative association between psychological health and years of intended practice (r = −.210, P = .047). The remaining quality of life domains had no significant correlation with years of intended practice (Table 8).

Table 8.

Pearson Correlations of Intent to Practice and Physician Quality of Life.

| Physical | Psychological | Social | Environmental | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intent to practice (years) | r = .038, P = .708 | r = −.210, P = .047* | r = −.010, P < .921 | r = .026, P < .800 | r = .078, P = .445 |

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

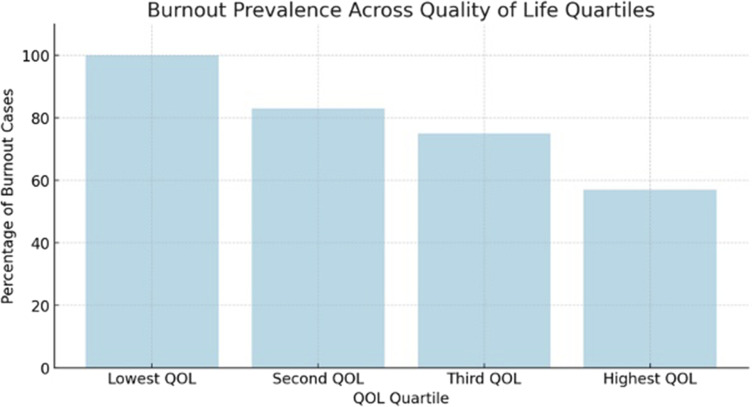

Quartile Assessments for Burnout and Quality of Life

This study demonstrates a clear inverse correlation between the two variables. As quality of life improves, burnout rates decline. Specifically, 100% of individuals in the lowest quartile for quality of life met the criteria for burnout, compared to 83% in the second quartile, 75% in the third quartile, and 57% in the highest quartile (Table 9).

Table 9.

Burnout Prevelence Across Quality of Life Quartiles.

|

Further categorization of individuals based on burnout and quality of life revealed that 32.7% experienced high burnout alongside low quality of life, while 46.0% reported high burnout despite high quality of life. Meanwhile, only 3.1% exhibited both low burnout and low quality of life, whereas 18.4% reported low burnout with high quality of life (Table 10). These findings highlight the complex interplay between burnout and quality of life, underscoring the need for targeted interventions to enhance well-being and reduce burnout among high-risk populations.

Table 10.

Distribution of Individuals Across Burnout & Qualtiy of Life Categories.

|

Discussion

Physician burnout continues to be a widespread issue in the healthcare sector despite considerable efforts and resources dedicated to alleviating the prevalence of this debilitating syndrome. Institutional and policy-based interventions, while well-meaning, have yielded inconsistent results and often fall outside the immediate control of physicians themselves.30,31 These interventions typically address systemic issues such as workload, administrative burdens, and organizational culture, yet they fail to fully mitigate the complex, multifactorial causes of burnout. On the other hand, individual-based approaches, such as mindfulness training, communication skills enhancement, and educational programs, offer limited reductions in burnout, typically producing only modest improvements in physicians’ well-being. 23 These findings suggest the need for more targeted strategies that address both organizational and personal factors contributing to physician burnout.

This study, involving 103 emergency medicine physicians, examines the relationship between burnout and quality of life, two closely intertwined yet distinct phenomena. Quality of life was evaluated across four primary domains: physical health, psychological well-being, social relationships, and environmental factors. Each of these domains was found to have a significant impact on burnout levels, highlighting the multifaceted nature of both constructs. Previous research has consistently demonstrated the link between burnout and quality of life,24,32-34 but this study contributes novel insights by focusing on emergency medicine physicians, a group that is frequently exposed to high levels of occupational stress and thus at greater risk for burnout.

The relationship between burnout and quality of life is symbiotic; high levels of burnout negatively impact personal and professional quality of life, while poor quality of life exacerbates burnout. The psychological and emotional toll of burnout can manifest in numerous ways, including physical health decline, anxiety and depression, diminished job satisfaction, strained interpersonal relationships, and increasing social isolation.5,8 These factors collectively contribute to a cycle of disengagement and dissatisfaction that not only affects the physician’s well-being but also compromises patient care. 8 The current study’s findings provide further empirical evidence supporting the strong association between quality of life and burnout, reinforcing the importance of improving physicians’ overall well-being to mitigate occupational stress.

A key finding from this study is the significant role that different domains of quality of life play in predicting various aspects of burnout. The analysis reveals that both physical and psychological health significantly predict emotional exhaustion. This suggests that individuals experiencing poor physical and psychological health are more likely to feel emotionally drained and exhausted by their work. Physical health could include factors such as energy levels, physical ailments, and overall physical wellness, while psychological health encompasses stress, mental clarity, and emotional resilience. Addressing these factors, possibly through physical health programs, stress management workshops, or mental health support, could reduce emotional exhaustion among professionals. This finding aligns with existing literature indicating that when individuals are physically unwell or psychologically distressed, they have fewer resources to cope with demanding work environments, making them more susceptible to emotional exhaustion.3,35

The results also indicate that psychological health significantly predicts depersonalization. Depersonalization, a feeling of detachment or impersonal response toward others, can be exacerbated by poor psychological well-being. When individuals struggle with mental health challenges, they may find it more challenging to engage empathetically with others, potentially leading to a more detached or cynical approach to their work. This finding suggests that strategies to support psychological well-being, such as counseling services, mindfulness training, or cognitive behavioral interventions, might help reduce feelings of depersonalization. Addressing psychological health appears especially crucial in roles that require high levels of interpersonal engagement, as poor mental health can directly impact one’s ability to maintain compassionate and connected interactions.

Environmental health and social relationships also appear to have a clear influence on each of the domains of burnout. Social relationships play a crucial role in mitigating or exacerbating burnout by influencing emotional resilience, providing support, and fostering a sense of connection. Strong social support systems, including personal relationships, peer networks, and workplace camaraderie, are protective against burnout as they help individuals manage stress, feel valued, and maintain emotional well-being. For example, physicians with strong workplace relationships report lower levels of emotional exhaustion and higher job satisfaction, as positive interactions with colleagues provide opportunities for emotional processing and collaborative problem-solving. 5 Conversely, poor social support or workplace isolation can intensify feelings of depersonalization and emotional exhaustion, key components of burnout, by leaving individuals without a sense of community or shared purpose. 3

Outside the workplace, environmental health and social relationships with family and friends are equally important. Engaging in meaningful interactions outside of work can help individuals decompress, provide a sense of balance, and reinforce a sense of identity beyond their professional roles. Without these relationships, physicians may struggle to recover from the demands of their work, increasing their risk of burnout. Interventions aimed at strengthening workplace relationships, such as team-building programs or mentorship initiatives, have been shown to improve workplace satisfaction and reduce burnout rate. 12

These complex interactions are a critical insight, particularly for emergency medicine physicians who work in high-pressure environments where quick decision-making, exposure to trauma, and life-or-death situations are commonplace. These stressors take a significant psychological toll, contributing to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, two core dimensions of burnout. 3 Given this, interventions that focus on enhancing psychological resilience and coping strategies may offer the greatest potential for alleviating burnout. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), resilience training, and mindfulness-based stress reduction have demonstrated efficacy in improving psychological well-being and reducing burnout in healthcare professionals.31,36

Moreover, this study suggests that improving any area of physical, psychological, social and environmental health may not only reduce burnout but also enhance other aspects of quality of life. For instance, better mental health can lead to improved social relationships, as physicians may be more engaged and emotionally available in their personal and professional interactions. Furthermore, psychological well-being will likely influence physical health, including cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal issues, and sleep disturbances. 37 Addressing the causes of psychological distress may create a ripple effect that improves multiple facets of a physician’s life, both inside and outside the workplace.

In this study, burnout levels closely aligned with quality of life, with all individuals classified as having low quality of life meeting the criteria for high burnout. Conversely, physicians in the highest quality of life quartile exhibited the lowest rates of burnout. Notably, the largest proportion of EM physicians fell within the high burnout/high quality of life category. This distribution likely reflects the inherently high rates of burnout within this specialty, alongside a relatively high reported quality of life.

This paradoxical coexistence of high burnout and high quality of life highlights the complexity of physician well-being and the dynamic interplay of the constructs. The observed relationship between burnout and quality of life among physicians, particularly in emergency medicine (EM), can possibly be attributed to several factors:

1. Demanding work environment: EM physicians frequently face high-intensity, time-sensitive clinical situations, long shifts, and unpredictable workloads, all of which contribute to elevated burnout rates. The environment may also provide a sense of purpose and identity that anchors the physicians sense of worth and contribution.

2. Emotional and cognitive load: The nature of emergency medicine requires constant decision-making under pressure, exposure to critical illness, and frequent encounters with patient death and suffering. These stressors contribute to emotional exhaustion, a key component of burnout but may also stimulate physician empathy and compassion that is essential to emotional health.

3. Work-life trade-offs: Despite high burnout levels, EM physicians may report relatively high quality of life due to scheduling flexibility, shift-based work that allows for extended time off, and competitive compensation. These factors can mitigate the negative effects of burnout, allowing for periods of recovery and work-life balance.

4. Professional fulfillment: Many EM physicians find intrinsic reward in their work, particularly in fast-paced, high-impact clinical settings. The ability to make immediate, life-saving interventions may enhance professional satisfaction, even in the presence of significant stressors.

5. Resilience and coping strategies: Physicians in high-burnout specialties often develop adaptive coping mechanisms, such as strong peer support networks and structured time off, which may contribute to maintaining a high quality of life despite workplace challenges.

The present study highlights the significant influence of burnout and select quality of life (QOL) domains on physicians’ intent to continue practicing in their current occupational setting. Notably, all three dimensions of burnout—emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment—demonstrated meaningful correlations with the projected years of practice. Consistent with existing literature, higher levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were associated with a reduced intent to practice, underscoring the detrimental impact of chronic occupational stress and emotional detachment on career longevity. 38 Conversely, a heightened sense of personal accomplishment correlated positively with extended career intentions, suggesting that fostering professional fulfillment may serve as a protective factor against premature workforce attrition.

Interestingly, within the QOL domains, only psychological health exhibited a significant negative relationship with intent to practice. This finding is somewhat paradoxical, as better psychological health would typically be expected to support longer career sustainability. One possible explanation is that physicians with improved psychological well-being may possess greater self-awareness and autonomy, allowing them to make proactive decisions about career transitions, retirement, or role modifications in favor of preserving long-term wellness. The absence of significant associations between physical health, social relationships, environmental factors, and intent to practice suggests that intrinsic psychological resilience and occupational experiences may weigh more heavily in career decision-making than external or physical considerations.

These findings emphasize the critical need for targeted interventions aimed at mitigating emotional exhaustion and depersonalization while enhancing personal accomplishment among physicians. Institutional strategies fostering supportive work environments, promoting professional development, and addressing the root causes of burnout could contribute to improved retention and prolonged career satisfaction. Furthermore, the nuanced relationship between psychological health and practice intentions warrants further investigation to better understand the motivational factors driving physicians’ career trajectories.

In conclusion, this study highlights the multifaceted interplay between burnout and quality of life, with physical and psychological health emerging as the most significant factors influencing burnout. Future interventions aimed at reducing burnout should prioritize physical and psychological well-being, offering emergency physicians the tools and knowledge they need to cope with the unique challenges of their profession. By addressing both organizational and individual factors, healthcare establishments can create a more supportive environment that promotes physician well-being, reduces burnout, and ultimately improves the quality of care provided to patients. As the findings suggest, enhancing the quality of life for emergency physicians is not only beneficial for their personal and professional satisfaction but also for the long-term sustainability of the healthcare workforce.

Limitations

This investigation presents several notable limitations that may affect the generalizability and reliability of its findings. Firstly, the study’s focus is exclusively on emergency physicians, which restricts the applicability of the results to other medical specialties and professions. This narrow scope may overlook the unique challenges and stressors faced by healthcare providers in different fields, limiting the potential for broader insights into the relationship between exercise and burnout across various medical environments.

Furthermore, social desirability bias may have influenced participants to under- or over-report burnout and quality of life, reflecting a tendency to present oneself in a favorable light, which could further distort the findings. Additionally, the response rate was unknown due to the recruiting methods being primarily via social media, and the represented cohort may not accurately represent the general population of emergency physicians, thus introducing selection bias. Physicians experiencing significant burnout may have been more likely to respond to requests for participation in the study.

Moreover, the burnout and quality of life surveys were administered at random intervals, which may have been affected by seasonal variations in patient volume, acuity, and complexity. Consequently, this timing could fail to capture a representative picture of burnout, as responses may fluctuate with the demands of the clinical and personal environment. Finally, the culture within the medical profession often discourages open discussions about emotional and mental health concerns due to fears of stigma and professional repercussions. This cultural barrier may lead to underreporting of burnout and related issues, ultimately impacting the reliability and comprehensiveness of the findings. Addressing these limitations in future research is essential to develop a more nuanced understanding of burnout and its contributors across diverse medical specialties.

Future Research

Future research on physician burnout presents an opportunity to identify innovative strategies and mechanisms tailored to reduce occupational stress, particularly those that address the unique challenges faced by practicing physicians outside traditional academic and training environments. Comparative studies examining various aspects of quality of life and physician burnout would further clarify the impact of lifestyle on occupational stress. Such investigations would assess whether specific lifestyle interventions effectively influence key burnout components, including emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and feelings of personal accomplishment.

Additionally, it is vital to conduct studies that identify individuals at the highest risk of burnout, particularly those who may benefit most from targeted interventions. This focused approach ensures that resources are appropriated efficiently and that interventions are customized to meet the needs of vulnerable populations.

Furthermore, multi-specialty investigations should be initiated to evaluate whether the findings of the current study are consistent across various medical disciplines. Such an inclusive approach would enhance our understanding of burnout in diverse contexts and facilitate the development of tailored strategies.

While there is a high correlation between quality of life and burnout, physicians can experience high quality of life (QOL) but high burnout if their personal lives, encompassing strong social relationships, physical health, and fulfilling activities, are robust, while their professional lives are highly stressful. Workplace stressors such as administrative burdens, long hours, or inadequate resources can lead to burnout despite an overall positive life outside work. Conversely, physicians with low QOL but low burnout may lack personal well-being due to poor physical health or social isolation yet experience supportive workplace environments that protect against burnout. This disconnect highlights the complex interplay between professional stressors and personal well-being in determining burnout and QOL. More research is needed into the significance of these subgroups and to what degree these subgroups exist.

Lastly, exploring the relationship between quality of life and physician burnout could provide deeper insights into effective methods for leveraging lifestyle as a preventive and mitigative measure. Investigating the barriers that impede higher quality of life will be instrumental in shaping future guidelines and interventions. Addressing these barriers is necessary for fostering a culture of wellness among physicians, which, in turn, can lead to improved outcomes, enhanced job satisfaction, and greater overall productivity within the medical profession. By prioritizing research in this area, we can contribute to the wellness of healthcare professionals and promote a healthier work environment.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Gregory M. Gibbons https://orcid.org/0009-0004-2044-9371

Helen W. Bland https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7822-9206

Bridget Melton https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2063-4356

References

- 1.Williams ES, Rathert C, Buttigieg SC. The personal and professional consequences of physician burnout: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2020;77(5):371-386. doi: 10.1177/1077558719856787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayer T. Battling Healthcare Burnout: Learning to Love the Job You Have, While Creating the Job You Love. San Franciso: Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding burnout. In: The Handbook of Stress and Health. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhardwaj A. COVID-19 pandemic and physician burnout: ramifications for healthcare workforce in the United States. J Healthc Leadersh. 2022;14:91-97. doi: 10.2147/JHL.S360163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516-529. doi: 10.1111/joim.12752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao SM, Yu HM, Ai YM, Song PP, Meng SY, Li W. Job-related burnout and the relationship to quality of life among Chinese medical college staff. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2015;70(1):27-34. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2013.859120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lall MD, Chang BP, Park J, et al. Are emergency physicians satisfied? An analysis of operational/organization factors. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021;2(6):e12546. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians during the first 2 years of the covid-19 pandemic. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(12):2248-2258. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azam K, Khan A, Alam MT. Causes and adverse impact of physician burnout: a systematic review. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2017;27(8):495-501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berg S. These 6 Physician Specialties Have the Most Burnout. American Medical Association; 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/these-6-physician-specialties-have-most-burnout. Accessed September 17, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kase J, Doolittle B. Job and life satisfaction among emergency physicians: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2023;18(2):e0279425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-146. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dyrbye LN, Satele D, Shanafelt TD. Healthy exercise habits are associated with lower risk of burnout and higher quality of life among U.S. medical students. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):1006-1011. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverman MN, Deuster PA. Biological mechanisms underlying the role of physical fitness in health and resilience. Interface Focus. 2014;4(5):20140040. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2014.0040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirby JM, Milligan PD, Conradie HH, McIntosh BM. A mindful approach to physician self-care. S Afr Fam Pract. 2024;66(1):5836. doi: 10.4102/safp.v66i1.5836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gholami A, Jahromi LM, Zarei E, Dehghan A. Application of WHOQOL-BREF in measuring quality of life in health-care staff. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4(7):809-817. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maslach C. Burnout: The Cost of Caring. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA. 2017;317(9):901-902. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York, NY: Guilford Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epstein R. Attending: Medicine, Mindfulness, and Humanity. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayo Clinic, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, et al. Burnout among health care professionals: a call to explore and address this underrecognized threat to safe, high-quality care. NAM Perspect. 2017;7(7):1-11. doi: 10.31478/201707b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-533. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamidi MS, Bohman B, Sandborg C, et al. Estimating institutional physician turnover attributable to self-reported burnout and associated financial burden: a case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):851. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3663-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gettel CJ, Courtney DM, Agrawal P, et al. Emergency medicine physician workforce attrition differences by age and gender. Acad Emerg Med. 2023;30(11):1092-1100. doi: 10.1111/acem.14764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory. Lanham: Scarecrow Education; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun H, Zhang T, Wang X, Wang C, Zhang M, Song H. The occupational burnout among medical staff with high workloads after the COVID-19 and its association with anxiety and depression. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1270634. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1270634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harper A, Power M, WHOQOL Group . Development of the World health organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):551-558. doi: 10.1017/S0033291798006667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Simone S, Vargas M, Servillo G. Organizational strategies to reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33(4):883-894. doi: 10.1007/s40520-019-01368-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haslam A, Tuia J, Miller SL, Prasad V. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials testing interventions to reduce physician burnout. Am J Med. 2023;137(3):249.e1-257.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barros DdS, Tironi M, Sobrinho C, et al. Burnout syndrome and quality of life in intensivists. Crit Care. 2007;11(3):P95. doi: 10.1186/cc5882 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pulcrano M, Evans SRT, Sosin M. Quality of life and burnout rates across surgical specialties: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(10):970-978. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weight CJ, Sellon JL, Lessard-Anderson CR, Shanafelt TD, Olsen KD, Laskowski ER. Physical activity, quality of life, and burnout among physician trainees: the effect of a team-based, incentivized exercise program. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(12):1435-1442. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Sanz-Vergel AI. Burnout and work engagement: the JD-R approach. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2014;1:389-411. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levine GN, Cohen BE, Commodore-Mensah Y, et al. Psychological health, well-being, and the mind-heart-body connection: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation (New York, N Y). 2021;143(10):e763-e783. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim R, Alvarez A, Cameron B, Gray S. Breaking point: the hidden crisis of emergency physician burnout. Can J Emerg Med. 2024;26:297-301. doi: 10.1007/s43678-024-00659-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]