Abstract

Inflammasomes are essential regulators of innate immunity, inflammation, and cellular apoptosis, and they have surfaced as significant modulators of cancer progression and regulation. Inflammasomes are macromolecular complexes assembled in response to damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). They induce inflammation via the oligomerization and activation of caspases. These cysteine proteases cleave the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 into their physiologically active mature versions. Recent discoveries reveal that inflammasomes are implicated not only in infections but also in malignancies, suggesting a significant connection between inflammation and tumor development. This article emphasizes that inflammasomes cause pyroptosis in a variety of immune cells, such as dendritic cells, macrophages, T cells, and fibroblasts, in addition to tumor cells. The induction of CD8+ T cells allows inflammasomes to commence an immunological response against the tumor, successfully inhibiting its growth and progression. The inflammasome comprises four main types: NLRP1, NLRP3, NLRC4, and AIM2. Nevertheless, the inflammasomes are activated by infection, injury, or stimulation of host cells, thus triggering the inflammatory response. The essential roles of the NLRP1, NLRP3, NLRC4, and AIM2 inflammasomes are emphasized in both tumors and immune cells. Furthermore, the article provides an overview of inhibitors targeting various tumor inflammasome pathways currently in clinical trials. Here, in this review, we underscore the role of the inflammatory response in cancer progression and highlight the significance of inflammasomes in regulating immune cells within the tumor microenvironment. Targeting these inflammasomes offers novel strategies for cancers.

Keywords: Inflammasome, Immunotherapy, Tumor microenvironment, Immune cells

Introduction

Cancer is one of the most prevalent causes of death worldwide, and its prevalence is continuously increasing [1]. In the process of tumor development, inflammation is widely regarded as a crucial factor. Early in the mid-nineteenth century, researchers first discovered the connection between inflammation and cancer [2]. Inflammation plays a role in the progression of cancer and is closely associated with the efficacy of anticancer treatments [3]. Inflammation has the potential to improve the efficacy of the antitumor immune response by promoting the infiltration and activity of immune cells. The growth and development of malignancies can be regulated by the infiltration and activity of adaptive and innate immune cells [4]. These immune cells may inhibit the progression of tumors through direct killing of tumor cells [5], induction of apoptosis [6], and suppression of angiogenesis [7].

Macrophages, Natural Killer (NK) cells, and dendritic cells (DCs) are essential components of the innate immune system [8]. Innate immune cells serve as the primary defence against pathogens by identifying pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), therefore generating immune responses that restore tissue homeostasis. The inflammasome, a multiprotein complex, is pivotal to this process since it regulates immunological and inflammatory responses [9]. Four well-characterized canonical inflammasome types are NLRP1, NLRP3, NLRC4, and AIM2. Inflammasomes are triggered in response to infections, cellular damage, or stress signals, leading to the maturation and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18 [10]. These cytokines are crucial in activating host defences, encompassing the recruitment of immune cells and the enhancement of anti-pathogen responses.

We have found that tumor immunotherapy is emerging as a new therapy for cancer patients in recent years. Treatment strategies include mainly modifying the tumor microenvironment (TME) and the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors and the like. However, there is a limited understanding of interactions among multiple types of immune cells and molecules associated with immunotherapy. The inflammasome has consequently become a most scrutinized topic in this cutting-edge field. Recent advances in inflammasome biology, particularly the discovery of non-canonical pathways (caspase-4/11 activation by cytoplasmic lipopolysaccharide) and their tumor-specific roles, have redefined its therapeutic potential [11]. Emerging evidence highlights inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis as a novel immunogenic cell death mechanism, bridging innate and adaptive anti-tumor responses [12]. Recent studies have shown that the inflammasome is involved in the inflammatory process and may greatly promote the effect of immunotherapy [13, 14]. Activation of the inflammasome is tightly related to control of immune cells and processes such as cell pyroptosis [15], prompting the investigation of its potential to mediate in tumor immunotherapy.

Not only does incorporating the potential role of inflammasome offer a deeper understanding of immunotherapy mechanisms, but it also provides novel opportunities for future research and clinical practice of immunotherapy. However, it could enable the creation of breakthroughs in personalized treatment, higher response rates to treatment, and overcoming immunotherapy resistance. New and more effective therapeutic approaches for cancer patients are offered by it.

In the present review, we give a complete survey regarding the structures and activation mechanisms of four inflammasomes and the functions of inflammasomes in different immune cells and their interactions within the tumor. We further investigate the function of inflammasome activation in anti-tumor immunity and comment on inflammasome-targeted inhibitors in clinical trials and potential targets for future anti-tumor immunotherapy. While previous reviews have focused on canonical NLRP3 signaling, emerging evidence reveals subtype-specific roles: NLRP1 promotes metastasis in hormone-resistant breast cancers via IL-18-mediated angiogenesis, while AIM2 paradoxically suppresses glioblastoma growth through interferon-γ (IFN-γ)crosstalk [16]. Our work distinctively synthesizes these divergent mechanisms with translational therapeutics, including first-in-class NLRP3 inhibitors in Phase II trials for PD-1 refractory melanoma [17].

Inflammasome biology and activation

The inflammasome concept was first introduced by Dr. Jurg Tschopp in 2002 [18]. Since then, extensive research has been conducted to elucidate the structure, activation mechanisms, and functions of different types of inflammasomes. The inflammasome is an essential element of the innate immune system, tasked with triggering an immune response to diverse microbial infections and danger signals [19]. It is a multi-protein complex consisting of PRRs, such as NOD-like receptors (NLRs) or absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2)-like receptors, adaptor proteins, and caspase-1 [20]. After assembly, the inflammasome facilitates the oligomerization of pro-caspase-1 into its enzymatically active form, which cleaves precursor cytokines (pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18) into their mature, bioactive isoforms [21]. Inflammasome governs pyroptosis, a type of cellular demise characterized by caspase-1/4/5/11-dependent inflammatory programmed cell death. Unlike apoptosis, which is a non-inflammatory planned cell death, pyroptosis is caused by gasdermin family protein-mediated membrane hole creation, which increases innate immune responses by causing cell swelling, lysis, and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18 [22].

Moreover, inflammasomes are categorized into canonical and non-canonical pathways based on their activation mechanisms and effector caspases. Canonical inflammasomes (NLRP1, NLRP3, NLRC4, AIM2) rely on caspase-1 to cleave pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into active cytokines, triggering pyroptosis via gasdermin D (GSDMD) [23]. In contrast, non-canonical inflammasomes are activated by caspase-4/5/11 in response to cytosolic lipopolysaccharide (LPS), directly cleaving GSDMD to induce pyroptosis without processing IL-1β/IL-18 [24, 25]. These pathways differ in structure and function: canonical inflammasomes require sensor proteins (NLRs, AIM2) and adaptor ASC for caspase-1 recruitment, while non-canonical pathways bypass ASC and utilize caspase-4/5/11 as both sensors and effectors [25] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Main differences between canonical and non-canonical inflammasomes

| Feature | Canonical inflammasomes | Non-canonical inflammasomes | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key caspase | Caspase-1 | Caspase-4/5/11 | [20, 24, 25] |

| Activation trigger | PAMPs (bacterial toxins), DAMPs (ATP), K+ efflux, ROS | LPS, oxidized phospholipids (oxPAPC) | |

| Structural components |

NLRs (NLRP1/3, NLRC4) AIM2 |

Caspase-4/5/11 (direct LPS sensing) | |

| Cytokine processing | Cleaves pro-IL-1β/IL-18 | Does not directly process cytokines | |

| Pyroptosis mechanism | GSDMD cleavage pore formation | GSDMD cleavage pore formation | |

| Role in tumor immunity | Dual role (pro-tumorigenic via IL-1β; anti-tumor via pyroptosis) | Amplifies inflammation, promotes metastasis |

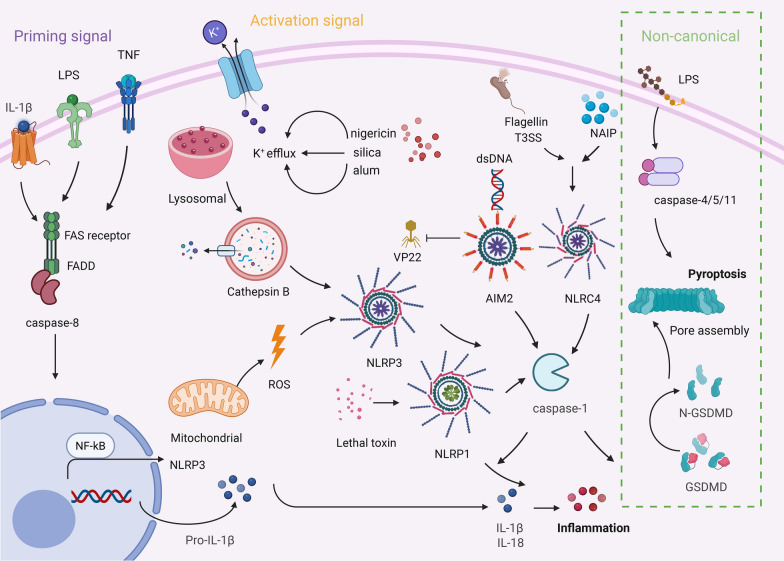

Overall, the inflammasome serves as a vital component of the innate immune system, essential for maintaining immune balance and safeguarding against infections and detrimental stimuli. To enhance comprehension of the inflammasome activation mechanism, we will provide a concise summary of the various categories of inflammasomes (Fig. 1). These activation mechanisms of canonical and non-canonical inflammasomes not only underpin innate immune responses but also critically shape the TME. Their ability to regulate cytokine release and pyroptosis in immune cells positions them as pivotal modulators of anti-tumor immunity, as elaborated in the following sections.

Fig. 1.

Activation mechanism of canonical and non-canonical inflammasome. Canonical inflammasomes are triggered by pattern recognition receptors (NLRP3, NLRC4, AIM2) by the detection of PAMPs or DAMPs. A two-step signaling process is involved: priming signal (the expression of NLRP3 and IL-1β precursor induced by TLR ligands or TNF-α through the NF-κB pathway) and an activation phase (K + efflux and lysosomal degradation triggering NLRP3 oligomerization), followed by the recruitment of the adaptor protein ASC and the activation of caspase-1. Subsequently, IL-1β/IL-18 precursors and the GSDMD were cleaved to liberate mature inflammatory mediators and initiate pyroptosis. Non-canonical inflammasomes are directly activated through the recognition of intracellular LPS by caspase-4/5/11, independent of ASC, leading to pyroptosis via GSDMD cleavage, while also indirectly activating the classical NLRP3 pathway through K+ efflux or mitochondrial ROS, thereby creating a cascade that amplifies the inflammatory response. The green box signifies the non-canonical inflammasome

Canonical inflammasomes

NLRP1

NLRP1 (also known as NALP1), initially identified as a protein containing NACHT, LRR, and PYD domains characteristic of the NLR family, plays a critical role in inflammasome activation [18]. While most NLRP1 is present in mammals, there is one NLRP1 gene in humans and several homologous NLRP1 genes (NLRP1a, NLRP1b, and NLRP1c) in mice [26]. Furthermore, NLRP1 can be activated through various mechanisms, including exposure to anthrax lethal toxin [26], Shigella flexneri [27], DPP9 (dipeptidyl peptidase) [28], viral infection [29], toxoplasma [30], and certain metabolic inhibitors. After activation, NLRP1 has the capacity to release pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and IL-18 [18]. Overall, NLRP1 functions as a crucial sensor protein within the inflammasome, significantly contributing to the immune response against pathogens and the modulation of inflammatory processes.

NLRP3

NLRP3 is widely known as the most characterized and exploited inflammasome in the NLR protein family. It is located mainly in diverse immune cells, such as macrophages and DCs [31]. Moreover, NLRP3 is widely expressed and plays a critical role in the regulation of inflammation and immunity.

For the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, two signals are required, which are called priming signals and activating signals [32]. IL-1β/IL-1R1, lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/Toll like receptor 4 (TLR4), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)/TNF receptor (TNFR) transmit the priming signal, and all these factors activate NF-kB [33]. The upstream regulators of NF-κB include Caspase-8, an apoptotic caspase, and Fas-associated protein with death domain, which in turn leads to the overexpression of NLRP3 and the production of pro-IL-1β [33, 34]. Simultaneously, priming signals promote the assembly of ASC and caspase-1 through various stimuli (such as K+ efflux [35], ROS production [36], release of lysosomal cathepsin B [37], and DAMPs, etc.), resulting in the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex. The primary mode of activation is induced by K+ efflux. Mitochondrial dysfunction [38], disrupting signals leading to ROS production, can mediate NLRP3 activation. Lysosomal rupture results in the cytoplasmic release of cathepsin B, and the phagocytosis of particulate material activates the NLRP3 complex, forming a crystal structure upon engulfment by phagocytes. Common DAMPs include nigericin [39], silica [40], aluminum [41], etc. NLRP3 inflammasome activation induces the production of caspase-1, leading to the maturation and release of IL-1β and IL-18. Upon activation, caspase-1 cleaves the pore-forming protein GSDMD, resulting in its N-terminal region creating pores in the cell membrane [42]. This process promotes the release of IL-1β and IL-18, resulting in lytic types of pyroptosis and inflammation.

NLRC4

NLRC4, often referred to as IPAF, Card12, and CLAN, is a constituent of the NLR family of intracellular receptor proteins. NLRC4 is chiefly linked to bacterial flagellin and the bacterial Type III secretion system (T3SS) [43, 44]. NLRC4 proteins can directly recruit and activate pro-caspase-1 independent of ASC [45]. It can interact with the NLR family apoptosis inhibitor protein (NAIP), activating downstream processes. It can bind to the NLR family inhibitor of NAIP, initiating downstream activation of NLRC4, leading to caspase-1 activation, and subsequently triggering the inflammatory response [45]. Additionally, NLRC4 enlists and activates caspase-8, instigating GSDMD-independent cell death in the presence of caspase-1 or GSDMD inhibition [45]. Pyroptosis not only triggers inflammation in the host but also captures dangerous microorganisms via the cell membrane pore, motivating the host to launch an immune response for the eradication of the pathogens [46].

AIM2

Absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2), which does not belong to the NLR family, is part of the HIN-200 family [47]. AIM2 is a protein composed of a Pyrin domain (PYD) and hematopoietic expression, interferon-inducible nature, and nuclear localization (HIN-200) domain [48]. The HIN-200 domain can bind to dsDNA, and AIM2 plays a crucial role in sensing abnormal dsDNA within the cell [49]. It can recognize dsDNA and recruit caspase-1 in an ASC-dependent fashion [50]. Active caspase-1 facilitates the maturation of precursor forms of IL-1β and IL-18 inside the cell, which are subsequently released into the extracellular space [51]. These two cytokines play essential regulatory roles in immune responses, particularly in the response to inflammation and infection. Viral-encoded protein (VP22) can inhibit the activation of AIM2, thereby suppressing viral proliferation [52]. The formation and activation of AIM2 inflammasomes constitute an important immune and inflammatory response of the immune system to the presence of abnormal dsDNA within cells. This mechanism contributes to clearing infections, maintaining cellular homeostasis, and guiding the immune system to mount appropriate responses.

Non-canonical inflammasomes

Non-canonical inflammasomes (caspase-4/5/11) have garnered increasing attention in tumor immunology in recent years. Unlike canonical inflammasomes, non-canonical inflammasomes directly activate caspase-4/5/11 by recognizing intracellular lipopolysaccharide (LPS), inducing pyroptosis and releasing IL-1α and IL-18, thereby modulating the TME [18]. Other minor activators such as oxPAPC [53], Leishmania lipophosphoglycan [54], and hemin can also serve as activators of non-canonical inflammasomes [55]. For example, in pancreatic cancer, non-canonical activation of caspase-11 promotes tumor cell death via a GSDMD-dependent pathway and enhances chemotherapeutic drug sensitivity [56]. Furthermore, crosstalk between non-canonical inflammasomes and canonical pathways synergistically regulates immune cell infiltration. Inhibitors targeting these pathways have demonstrated anti-tumor potential in melanoma models [57]. When the immune response fails to effectively clear infections and evolves into persistent inflammation, non-canonical inflammasomes can lead to diseases such as sepsis and pulmonary infections. The results of canonical and non-canonical inflammasome activation are analogous. Both processes encourage cells to activate inflammatory programs, including pyroptosis and the secretion of inflammatory cytokines. Future studies should further elucidate cell-specific mechanisms to optimize targeted therapeutic strategies.

Inflammasomes and cancer

In the TME, inflammasomes have multiple functions in either facilitating or suppressing tumor progression, contingent upon the precise kind of inflammasome implicated. Some inflammasomes have been reported to promote tumor growth by enhancing inflammation and contributing to immune evasion mechanisms employed by the tumor [58]. On the other hand, some inflammasomes can inhibit tumor growth by promoting immune responses, activating anti-tumor immune cells, and enhancing tumor cell death [59]. The role of inflammasomes in the TME exhibits highly context-dependent characteristics, governed by the interplay of tumor type, cellular origin, and crosstalk with oncogenic signaling pathways [60]. For instance, in colorectal cancer (CRC), NLRP3 drives inflammation-associated carcinogenesis via the IL-1β/NF-κB signaling axis while suppressing metastasis through GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis [61]. However, NLRP3 activation in breast cancer suppresses tumor progression by promoting immunogenic cell death and enhancing CD8⁺ T cell infiltration [62]. Cellular origin further dictates functional divergence: macrophage-derived NLRP3 recruits myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) via IL-1β secretion to fuel pancreatic cancer growth, while dendritic cell-derived NLRP3 enhances antigen presentation and T-cell activation, thereby inhibiting tumor progression [63]. Additionally, inflammasomes interact dynamically with oncogenic pathways such as hypoxia, metabolic reprogramming, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [12]. Hypoxia-induced NLRP3 promotes glycolysis and angiogenesis in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) through metabolic reprogramming [64]. Besides, NLRP3 inhibition suppresses EMT in non-small cell lung cancer by blocking TGF-β signaling [65]. Clinically, therapeutic outcomes of inflammasome-targeted agents like the NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950 (an NLRP3 inhibitor) are context-dependent: it effectively reduces colitis-associated cancers but fails to inhibit pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, underscoring the necessity for precision-targeted therapies tailored to tumor-specific contexts [66]. These findings highlight the dual roles of inflammasomes in cancer biology and emphasize the importance of dissecting microenvironmental determinants to optimize therapeutic strategies.

Emerging clinical data highlight the interplay between inflammasome activation and systemic inflammatory biomarkers. In addition to IL-1β and IL-18, inflammasomes indirectly elevate C-reactive protein (CRP) levels by stimulating IL-6 secretion, which subsequently activates hepatic CRP production [67]. Elevated serum ferritin, a marker of inflammation and cellular damage, correlates with NLRP3-driven pyroptosis in tumor-associated macrophages and predicts poor prognosis in colorectal and breast cancers [68]. Furthermore, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) have been linked to inflammasome activity in cancer patients, reflecting chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation [69]. These biomarkers provide clinically actionable thresholds for monitoring inflammasome-related therapeutic responses. For instance, in non-small cell lung cancer, pretreatment hyperferritinemia is associated with reduced efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy, suggesting that inflammasome inhibition could be a potential adjuvant strategy [70]. Integrating these markers with inflammasome profiling could refine patient stratification and therapeutic targeting.

Inflammasomes exhibit a more pronounced regulatory role in the TME than in tumor cells themselves, primarily through their activation in immune and stromal compartments. For instance, NLRP3 activation in dendritic cells enhances CD8+ T cell priming, while cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) upregulate NLRP3 to drive IL-1β-dependent immunosuppression and metastasis. Similarly, macrophage-specific NLRP3 signaling polarizes tumor-associated macrophages toward a pro-tumorigenic M2 phenotype, fostering angiogenesis and immune evasion. These findings underscore that inflammasomes shape tumor progression predominantly via TME-mediated immunomodulation rather than tumor cell-autonomous mechanisms. Here, we have summarized the expression levels of inflammasomes in different tumors, indicating whether they contribute to pro-tumorigenesis or anti-tumorigenesis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Tumor-promoting function or anti-tumor effect of the inflammasome

| Types of inflammasome | Types of cancer | Pro-tumorigenesis | Anti-tumorigenesis | Expression of inflammasome in cancer | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLRP1 | Metastatic melanoma | √ | – | [58] | |

| Breast cancer | √ | ↑ | [104] | ||

| Lung adenocarcinoma | √ | ↓ | [77] | ||

| Prostate cancer | √ | ↑ | [78] | ||

| Gastric cancer | √ | ↑ | [79] | ||

| Colitis and Colitis-Associated Tumorigenesis | √ | – | [80] | ||

| NLRP3 | Gastric cancer | √ | ↑ | [79] | |

| Colorectal cancer | √ | ↓ | [61] | ||

| Head and neck cancer | √ | ↑ | [82] | ||

| Oral squamous cell carcinoma | √ | ↓ | [72] | ||

| Prostate cancer | √ | ↑ | [78] | ||

| NLRC4 | Prostate cancer | √ | ↑ | [78] | |

| Breast cancer | √ | – | [85] | ||

| AIM2 | Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma | √ | ↑ | [95] | |

| Colorectal cancer | √ | – | [61] | ||

| Breast cancer | √ | – | [73] | ||

| Non-small-cell lung cancer | √ | ↑ | [96] | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | √ | ↓ | [167] | ||

| Renal carcinoma | √ | ↓ | [192] | ||

| Caspase-11 | Breast cancer | √ | ↑ | [73] | |

| Caspase-4/5/11 | Colorectal cancer | √ | ↑ | [61] | |

| Caspase-4 | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | √ | ↓ | [137] |

√: Indicates a promoting (pro-tumorigenesis) or inhibitory (anti-tumorigenesis) role

↑/↓: Upregulated or downregulated expression in cancer compared to normal tissue

– No available data

Inflammasome abbreviations: NLRP1, NLRP3, NLRC4, AIM2

Recent research has emphasized the suppressive impact of inflammasomes on tumor development. For instance, the research reveals a protective role of NLRP1 in gastrointestinal inflammation and tumorigenesis. NLRP1b−/− mice exhibit significantly increased incidence, inflammation, and tumor burden, correlating with reduced levels of IL-1β and IL-18 [71]. This highlights the involvement of NLRP1 in colonic epithelial cell compartments, mitigating tumor development, with significant implications for host immune responses during IBD and cancer [71]. Furthermore, the significant downregulation of NLRP3 expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells markedly reduced caspase-1 cleavage and IL-1β production, inhibiting cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [72]. This led to heightened E-cadherin expression and diminished N-cadherin expression, ultimately resulting in a significant reduction in the proliferation of oral squamous cell carcinoma [72]. The expression of AIM2 suppresses the proliferation and tumorigenicity of human breast cancer cells [73]. AIM2 gene therapy inhibits the proliferation of breast cancers in an in situ tumor model [73]. AIM2 promotes apoptosis in tumor cells while simultaneously suppressing NF-κB activation, indicating its prospective utility as a therapeutic gene for breast cancer in the future [73]. Here, it is noteworthy that the precise mechanisms of inflammasome function in various cancer types require further investigation.

On the contrary, whereas inflammasomes may have pro-tumorigenic effects in certain situations, they have also been demonstrated to play a tumor-promoting role in the progression of certain cancers. The research indicates that NLRP1 facilitates melanoma proliferation by augmenting inflammasome activation and suppressing apoptotic pathways, highlighting its oncogenic function in cancer cells [74]. NLRP1 is extensively expressed in 83% of initial breast cancer tissues, with expression levels significantly exceeding those in surrounding non-cancerous tissues [75]. Moreover, NLRP1 enhances the proliferation, migration, invasion, and tumorigenicity of the breast cancer cell line MCF-7, and is positively associated with lymph node metastases, TNM staging, and Ki-67 levels, while facilitating EMT [75, 76]. Bioinformatic examination of lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) data obtained from TCGA and GEO indicated that NLRP1 expression is markedly diminished in LUAD compared to normal lung tissue, and it correlates with pathology, T staging, and N staging [77]. Low expression of NLRP1 is an independent adverse prognostic factor in LUAD, and its expression level is positively correlated with immune cell infiltration in the TME, emphasizing the important role of NLRP1 in LUAD prognosis and immune regulation [77]. NLRP1 and NLRC4 expressions in prostate cancer are elevated compared to normal prostate tissues, and NLRP1 and NLRC4 expressions in prostate cancer are favorably correlated with IL-1β and IL-18 levels, also significantly positively correlated with Gleason score and T staging in the Cancer Genome Atlas data [78]. The release of proinflammatory cytokines by inflammasomes [78], seems to play a significant role in the onset and development of prostate cancer.

The most well-studied inflammasome is NLRP3, which controls both the tumor and the TME composition. NLRP1 and NLRP3 are both highly expressed in gastric cancer, and their high expression is closely related to lymph node metastasis, low survival, and increased immune infiltrating cells [79]. NLRP3 shows a stronger association with immune infiltration and gastric cancer prognosis [79]. In particular, its expression is markedly increased in human CRC tissues and positively associated with tumor size, invasion, lymph node metastases, venous invasion, nerve infiltration, and TNM staging [80]. Inhibition of migration and proliferation in CRC cells, both in vitro and in vivo, was found following the knockdown of NLRP3, alongside the reversal of the EMT process in vitro [81]. In head and neck cancer, the upregulation of NLRP3 levels promotes the progression of tumor [82]. An overexpression of NLRP3 facilitates the invasive progression of prostate carcinoma (PCa) cells, whereas the silencing of NLRP3 impedes this advancement via positively modulating caspase-1 [83]. Experimental evidence demonstrates that the overexpression or inhibition of caspase-1 can reverse the effects of NLRP3 in PCa cells, ultimately suppressing tumor growth in PCa [83]. The diminished expression of the NLRP3 protein correlates with susceptibility to Crohn's disease [84]. Obesity-related NLRC4 inflammasome activation and IL-1 signaling promote the progression of breast cancer by inducing infiltrative myeloid cells, activating IL-1β, and facilitating disease development via adipocyte-mediated VEGFA production and angiogenesis [85].

Emerging evidence highlights the critical role of pathogen-associated inflammasome activation in tumorigenesis. For instance, HPV-driven oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) exhibits NLRP3 upregulation, wherein viral oncoproteins E6/E7 perpetuate NF-κB-mediated IL-1β secretion, fueling chronic inflammation and EMT [86, 87]. Similarly, in EBV-associated gastric cancer, the viral latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) activates NLRP3 via TLR/NF-κB signaling, resulting in IL-18 release and immunosuppressive microenvironment formation [88]. These findings exemplify how microbial agents exploit inflammasomes to subvert innate immunity, linking persistent infection to cancer progression. Such mechanisms underscore the therapeutic potential of targeting pathogen-inflammasome crosstalk in infection-related malignancies.

Microbial regulation of inflammasomes in cancer

An important axis in tumor immunomodulation is the interaction between the microbiota and inflammasomes [89]. The NLRP3 inflammasome is activated in CRC cells by dysbiosis, especially the enrichment of pathobionts such as Fusobacterium nucleatum, which promotes IL-1β/IL-18-dependent tumor development and metastasis [89]. Conversely, commensal-derived butyrate inhibits NLRP3 activation in intestinal epithelial cells, restoring mucosal barrier integrity and suppressing colitis-associated carcinogenesis [90]. In the TME, microbial metabolites such as propionate engage the AIM2 inflammasome in dendritic cells, amplifying STING-dependent type I interferon responses and CD8+ T cell infiltration [48]. Notably, enriched cohorts show increased NLRP3-dependent anti-PD-1 responses in melanoma models, suggesting that microbiome-driven inflammasome activation may affect the effectiveness of immunotherapy [91, 92]. These findings position microbial-inflammasome crosstalk as a therapeutic target to reprogram tumor-immune dynamics.

In addition to the NLR family inflammasomes, AIM2 is linked to tumor proliferation. In CRC, AIM2 is typically downregulated [93]. The knockdown of AIM2 enhances CRC proliferation, motility, and EMT, whereas AIM2 overexpression has a contrary effect [93, 94]. AIM2 inhibits the expression of Gli1 and regulates CRC cell proliferation and migration in a Gli1-dependent manner [93]. In cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), AIM2 is upregulated at both mRNA and protein levels [95]. Knockdown of AIM2 leads to decreased cell survival, increased apoptosis, and reduced invasion and angiogenesis in cSCC cells [96, 97]. The results presented here indicate that AIM2 may represent a viable target for therapy for cSCC, impacting the invasive and metastatic growth of the tumor [97]. In NSCLC, elevated AIM2 expression correlates with unfavorable prognosis and enhances tumor cell growth and proliferation irrespective of inflammasome activity [96]. Knockdown of AIM2 enhances mitochondrial fusion, reduces cell proliferation, and influences the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway by regulating MFN2 and ROS production [97]. Low expression of AIM2 is highly correlated with an unfavorable prognosis in RCC [98]. Overexpression of AIM2 inhibits the proliferation, migration, and invasion of 786-O or OSRC-2 cells, and it may suppress the malignant characteristics of RCC through the enhanced induction of autophagy [97]. Aberrant expression of AIM2i-RGs in tumor tissues is closely associated with poor prognosis, and its role in immune regulation may involve tumor immune score, stromal score, CD8+ T cell abundance, and immune checkpoint-related markers [99]. The low expression of AIM2 in CRC was further confirmed by immunohistochemistry results [97].

In summary, the function of inflammasomes in tumor proliferation is dual. In specific cancer forms, inflammasomes can inhibit tumor incidence and progression. The unique role of every given inflammasome in certain contexts is contingent upon multiple elements, including the cancer type and the activation mechanism. After outlining the dual roles of inflammasomes in tumor progression, we now delve into how these mechanisms intersect with immune cell activity to orchestrate anti-tumor responses.

Inflammasomes synergize in anti-tumor immunity

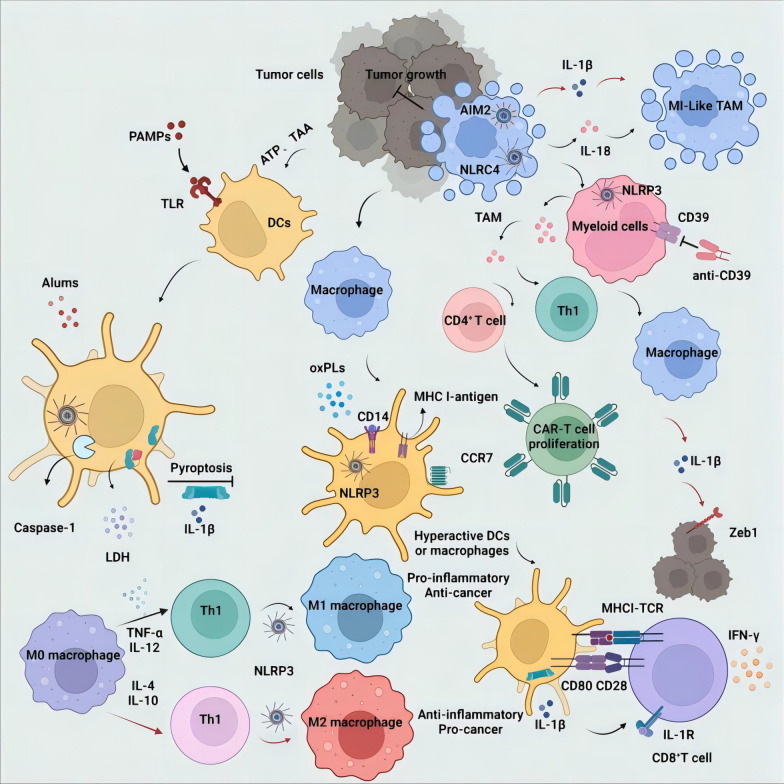

Inflammation can facilitate the onset and advancement of cancer by promoting angiogenesis, enhancing cancer cell proliferation, facilitating tumor aggressiveness, suppressing immune responses, and altering the effectiveness of specific anti-cancer drugs [97]. The key to triggering a robust anti-tumor immune response lies in the active release of tumor cells, such as tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and other intracellular components induced by processes like pyroptosis [100]. Specifically, by activating antigen-presenting cells, such as DC, it stimulates them to capture, process, and present antigens, activating T cells and initiating an immune response [101]. These mechanisms work together to create favorable conditions for the effective initiation of an immune response against tumor cells. However, inflammasomes can also exert anti-tumor effects. Emerging evidence underscores their paradoxical roles in promoting immune suppression and metastasis [102]. Notably, NLRP3 activation within tumor-associated macrophages recruits MDSCs, which dampen cytotoxic T-cell responses and foster an immunosuppressive microenvironment [103]. In breast cancer models, NLRP3-driven IL-1β secretion induces EMT, thus accelerating metastatic dissemination [104]. These findings highlight the tumor-dependent nature of inflammasome signaling and the necessity for cell-type-specific therapeutic targeting. Additionally, NLRP3 activation-induced pyroptosis of tumor cells releases DAMPs and tumor-associated antigens such as ATP and HMGB1 [105]. These chemicals modulate anti-tumor immune responses via two separate pathways: by influencing tumor cells and immune cells, respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The impact of inflammasome activation on immune cells and anti-tumor immunity. Pro-tumor: Chemotherapy triggers NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis in tumor cells, releasing ATP and DAMPs that recruit immunosuppressive CD39+ myeloid cells and M2 macrophages, driving tumor progression via IL-1β-induced EMT and MDSC recruitment. Anti-tumor: NLRP3/AIM2 activation induces pyroptosis and IL-18 release, enhancing NK/CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity (via IFN-γ/PD-L1 suppression) and polarizing M1 macrophages to secrete IL-12 for Th1 activation. Spatial segregation and color-coding (red arrows: pro-tumor; black arrows: anti-tumor)

Mechanisms of pyroptosis evasion in tumor cells and immunotherapeutic implications

In the process of cancer development, tumor cells often have the ability to evade pyroptosis, facilitating their unrestricted growth and spread. Malignant tumor cells can avoid pyroptosis mainly due to functional loss mutations or epigenetic silencing of components in the inflammasome [106]. NLRP3 is presently the most thoroughly examined inflammasome. In some human tumors, the expression of the adaptor protein ASC of the NLRP3 inflammasome is regulated by methylation-induced silencing [107]. The epigenetic control of the NLRP3 inflammasome ASC in malignancies is affected by the presence of the CARD domain [108]. The inactivity of this protein in malignant malignancies is associated with their genesis and growth [109]. Additionally, inflammasomes exhibit a protective role in CRC-associated inflammation (CAC) [61]. By maintaining their components during acute and recurrent colitis and CAC, inflammasomes alleviate disease outcomes and tumor development [110]. At the same time, the lack of the ASC adaptor protein and Caspase-1 promotes disease in mouse models, and the NLRP3 gene in hematopoietic cells demonstrates that the inflammasomes act as attenuators in colitis and CAC [111]. However, it has been reported that studies have found that mice that are lacking NLRP3 or Caspase 1 are highly sensitive to azoxymethane/dextran sodium sulfate induced inflammation, resulting in an increase of the tumor burden in the colon to a significant extent [112]. Increasing IL-18 can prevent colitis associated tumors in IL18−/−, NLRP3−/− and Caspase 1−/− mice [113]. Preventing the development of colorectal tumors is largely dependent on IL-18 downstream.

The cell pyroptosis executor family, GSDM, is the only one in the downstream of the inflammasome [114]. GSDME, or DFNA5, belongs to the GSDM family [115]. GSDME inhibits malignancies, including melanoma, triple negative breast cancer, and CRC, in murine tumor models and human tumor specimens by converting apoptosis to pyroptosis [116]. NK cells during the pyroptosis process release cytotoxic granule enzyme-B onto GSDME in tumor cells, and subsequently lead to the holes forming on the cell membrane of tumor cells and ultimately lead to pyroptosis [117]. Simultaneously, tumor antigens and DAMPs are released [118]. The released chemicals elicit an in situ immunological response, thereby augmenting the cytotoxic effects of CD8+ T cells, NK cells, and natural killer T cells (NKT cells) [119]. This process contributes to strengthening the immune system’s attack against tumors.

The serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), serving as a marker for cell damage and pyroptosis, often signifies a poor prognosis in tumors. Cancer patients with elevated LDH levels, demonstrate diminished T cell infiltration and functionality inside the TME, along with a diminished response to checkpoint inhibitors [120]. Therefore, serum LDH is considered a potential biomarker for patients with impaired immune anti-tumor capabilities [121]. However, in patients with elevated LDH levels, it is still unclear whether pyroptosis of myeloid cells in the TME or draining lymph nodes (dLN) correlates with the attenuation of CD8+ T cell responses [120]. Hence, more accurate clinical markers are required to enhance the understanding of tumor cell pyroptosis in anti-tumor therapy.

Dendritic cell

Inflammasome activation triggers pyroptosis in both tumor and immune cells, but with divergent immunological consequences. In tumor cells, pyroptosis releases DAMPs and tumor-associated antigens, which recruit dendritic cells and enhance cross-presentation to CD8+ T cells, thereby amplifying anti-tumor immunity [122]. Conversely, pyroptosis in immune cells like dendritic cells can disrupt their survival and migration to lymph nodes, impairing their ability to prime T cells and inadvertently suppressing adaptive immune responses [56]. For instance, NLRP3 activation in dendritic cells reduces their CCR7-mediated migration to draining lymph nodes, limiting T-cell activation [123]. This duality underscores the need for cell-type-specific strategies when targeting inflammasomes for immunotherapy [124]. This suggests that GSDMD hole development and cell pyroptosis may be pivotal in modulating the activation of inflammatory dendritic cells in T cells.

Maintaining long-term vitality in DCs is crucial for achieving adaptive immunity. Studies indicate that Conventional Dendritic Cells (cDCs) exhibit greater tolerance under the stimulation of highly pathogenic pathogens or inflammasome activators such as nigericin, ATP, and FlaTox [125]. They can resist pyroptosis mediated by the inflammasome. The expression of crucial parts of the inflammasome system, such as NLRP3, ASC, caspase-1, and pro-IL-1β, is markedly diminished in cDCs [126]. The resistance of DCs to pyroptosis is linked to the transcription factors IRF8 in conventional DC type 1 (cDC1s) and IRF4 in conventional DC type 2 (cDC2s). These factors bind to the promoter sequences of inflammasome-related genes (NLRP3, AIM2), resulting in transcriptional suppression of these genes [127]. Therefore, they are identified as negative regulators of inflammasome activity within cDCs.

The role of inflammasomes is not only to stimulate cells to become hyperactive but also to trigger immune responses. Research has revealed that highly active DCs not only exhibit typical features of activated DCs, such as secreting TNF-α and IL-6, upregulating co-stimulatory molecules, and antigen presentation, but also undergo excessive migration to lymph nodes and provide IL-1β to CD8+ T cells [31]. When the Nlrp3 or Ccr7 genes are knocked out within DCs, this T cell stimulatory capacity is lost [31]. Interestingly, not all NLRP3 agonists demonstrate efficacy in anti-tumor immunity. Alum, for example, diminishes the functioning of dendritic cells, leading to inadequate activation of anti-tumor CD8+ T lymphocytes [31]. The conventional type 2 dendritic cell (cDC2) subset in humans is a primary DC subset, showing no pyroptosis in transcription and function concerning inflammasomes. Upon stimulation with ligands that moderately activate the inflammasome, cDC2 cells do not experience pyroptosis; rather, they produce IL-12 family cytokines and IL-1β [125]. This study presents potential therapeutic options for the treatment of inflammasome-dependent inflammatory illnesses and may introduce innovative strategies for adjuvant and vaccine development.

Macrophages

Macrophages can exert anti-tumor effects, and the activation of inflammasomes within macrophages can promote immune evasion by tumor cells [128]. Research indicates that lactic acid at the site of CRC serves not only as DAMPs to activate inflammasomes within macrophages but also can inhibit inflammasome activation through upregulation of ROS or the action of TGF-β [129]. Such regulatory mechanisms establish a complex interplay between inflammasome activity within macrophages and the occurrence and progression of tumors [130]. Monocyte-derived macrophages, when influenced by LPS or IFN-γ, can differentiate into two functional phenotypes: pro-inflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory M2 [131]. The M1 phenotype exhibits phagocytic and antigen-presenting activities, produces Th1-activating cytokines [132], and demonstrates anti-cancer activity by mediating cytotoxic functions. In contrast, the M2 phenotype is believed to play a role in the establishment of a TME that is conducive to tumor survival and growth by supporting tumors, promoting angiogenesis, and suppressing the immune system.

The polarization of macrophages influences the initiation, advancement, and management of numerous illnesses.TGR5 signaling has been identified as alleviating hepatic steatosis and inflammation, concurrently inhibiting the polarization of M1 macrophages in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) mediated by NLRP3 [133]. Metformin, in regulating the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway, inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and promoting the polarization of M2 macrophages, has demonstrated an accelerating effect on wound healing [134]. The research findings provide new perspectives into the molecular mechanisms of metformin administration and its prospective therapeutic effects on wound healing. The activation of inflammasomes in macrophages can facilitate the polarization of M1 macrophages, therefore producing an anti-tumor immune response. tumor-associated macrophages in the TME primarily have an M2 phenotype. NLRP3 signaling, upon activation in macrophages, can stimulate CD4+ T cells, facilitating the development of Th2 cells, Th17 cells, and regulatory T cells [135]. It can also inhibit the production of Th1 responses and decrease the cytotoxic activation of CD8+ T cells [135]. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) tumor cells produce IL-1β, which is essential for forming the tumor microenvironment because it promotes the infiltration and activation of immunosuppressive cells and M2-polarized macrophages while also activating CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) [136]. T lymphocytes, thereby inhibiting pancreatic tumor growth [137]. Since the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome can be activated under the influence of special cytokines, it can also regulate the polarization direction of macrophages, mediating anti-tumor immunity.

Fibroblasts

The generation and progression of cancer are highly dependent on the TME. Concerning Cancer Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) expression, the progressiveness of breast cancer and patient prognosis are directly associated, and CAFs are significant in tumor stimulation via multiple processes [138]. Additionally, the evidence shows that CAFs have a vital role in orchestrating the immune cell recruitment to participate in inflammation in the TME [139]. This inflammatory response is an important contribution of the NLRP3 inflammasome. The NLRP3 inflammasome comprises a cluster of cytokines that also recognize DAMPs produced by stressed or injured cells [107]. Proinflammatory chemicals such as DAMPs are known to greatly activate the inflammasome, with particular note that tumors are rich sources of DAMPs and aid in inflammasome activation.

Inflammation studies have revealed that the inflammasome pathway is two-faced and both pro- and anti-tumorigenic, depending on the type of tumor. This pathway has been shown to play a role in tumor progression, metastasis, and immune evasion. The activation of the inflammasome in turn will lead to the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and IL-18, resulting in the survival and proliferation of tumor cells.

On the other hand, activation of the inflammasome can itself drive immune cell infiltration to facilitate tumor cell death. Thus, the effects of the inflammasome pathway across various tumor types are intricate and context-dependent. Therefore, further research is needed to comprehensively understand its role in cancer development and expand its potential as a therapeutic target. In fact, the upregulation of NLRP3 in CAFs has been shown in both mouse and human breast cancer [104]. Investigations also noted that fibroblasts can act as receptors of DAMPs, causing the inflammasome to be activated and releasing IL-1β [140]. Previous studies have demonstrated that silencing or reducing the expression of NLRP3 or IL1 in CAFs may inhibit CAF proliferation and breast cancer cell proliferation to an extent that prevents lung metastases [141]. These findings indicate that targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway in CAFs could be a good therapeutic approach to inhibit breast cancer progression and metastasis. Furthermore, CAF secreted IL-1β has been shown to promote recruitment of MDSCs and to express the adhesion molecule, which contributes to tumor development and metastasis [142]. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome contributes to tumor development, which is supported by an analysis of CAFs. Interestingly, IL-1β expression is rather increased in tumor tissues, e.g., melanoma and breast cancer, however, anti-breast cancer effects have been seen in NLRP3 knockout animals [143, 144]. In this context, fibroblasts represent a key receptor for the inflammasome pathway and show the relevance of activating IL 1β in CAFs as a stimulus of the proinflammatory CAF phenotype.

The dual roles of NLRP3/IL-1β in CAFs are critically dependent on tumor type and experimental models. In breast cancer, NLRP3 activation within CAFs promotes metastasis through IL-1β-mediated recruitment of MDSCs, establishing an immunosuppressive TME [142]. Conversely, in CRC models, NLRP3 deficiency exacerbates colitis-associated carcinogenesis by impairing epithelial repair mechanisms [61]. This tumor-type specificity extends to therapeutic interventions: while NLRP3 inhibition with MCC950 suppresses pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma progression, genetic NLRP3 ablation accelerates intestinal tumors [66]. Furthermore, cellular origin dictates functional outcomes—CAF-derived NLRP3 drives pro-tumorigenic inflammation, whereas dendritic cell-specific NLRP3 activation enhances anti-tumor CD8+ T cell responses in melanoma. These paradoxical effects underscore the necessity for precision targeting based on tumor microenvironmental context and cellular compartmentalization.

Our findings provide novel insights into the function of CAFs and the NLRP3 inflammasome in tumor growth and indicate that inhibition of this pathway in CAFs may have therapeutic potential in cancer treatment. However, it is important to study these underlying mechanisms further in greater detail and explore potential therapeutic strategies.

T cell

T lymphocytes are stimulated and collaborate with antigen presenting cells (APC) to induce an effective immune response against malignancies [145, 146]. The T Cell Receptor (TCR) pathway and the co-stimulatory pathway are two main signaling pathways that activate T cells, a type of immune cell crucial for the identification and eradication of tumor cells. When TCR on the T cell surfaces come into contact with a particular antigen with APCs, the TCR pathway is triggered, including a signaling process that causes the T cell to be activated and produce effector chemicals that can directly kill tumor cells [147]. Additionally, co-stimulating molecules such as CD28 on T cells and CD80/60 on APC bind to each other to provide a secondary signal of augmenting T cell activation and proliferation [148]. APCs, like dendritic cells, macrophages, and B cells, are responsible for presenting tumor antigens to T cells [149]. These tumor antigens are sequestered and processed by them, and presented on their surface in association with major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. TCR recognizes the antigen/MHC complex, and the T cell responds to the activation, ensuing the immune response against tumor cells.

NK cells are an important part of the innate immune system, which can recognize and kill tumor cells without prior sensitization. In addition, it can directly lyse neoplastic cells and secrete cytokines that additionally strengthen the anti-tumor immune response. In recent years, utilizing T cells and NK cells for cancer therapy with the notion of growing the function and potency of these immune cells against tumors has been encouraging. Cancer therapeutic strategies include immune checkpoint inhibitors, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy, and NK cell directed therapy. There are targeted therapies that can intervene in the activation and activity of T lymphocytes and NK cells, which can selectively eliminate tumor cells, yielding better outcomes for patients. This axis has recently been further verified by in vivo studies. For instance, NLRP3 activation via ATP enhanced IFN-γ CD8+ T cell infiltration and delayed melanoma progression in mice [123], while AIM2-dependent GSDMD signaling restored CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity in CRC models [150]. Clinically, MCC950 (an NLRP3 inhibitor) combined with anti-PD-1 increased tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells in a Phase I trial, underscoring translational potential.

The regulation of T cell activity by IL-1β is integral and it can play various regulatory roles in T cell differentiation, memory T cell development, and the augmentation of effector T cells which IL-1β does by activation of the transcription factors, such as signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), via myeloid differentiation main response 88 (MyD88) pathway [151, 152]. IL-1R is present on the CD4+ and CD8+ naive and memory T lymphocytes cell surfaces [153], and this activation mechanism allows transforming naive T cells into helper T cells, an essential phase of adaptive immune response. Once bound with IL-1β, the IL-1R will activate existing memory CD4+ T cells to augment their production of IFN-γ and other effector functions [154]. Moreover, IL1β is also able to promote the proliferation and differentiation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells.

Moreover, it is found by research that IL-1β also encourages memory CD8+ T cell activation and stimulates memory CD8+ T cell generation in vivo in mice. The significance of this finding is that IL-1β plays a fundamental part in the generation and maintenance of T cell memory, an essential element of the immune system’s ability to maintain long-term protection against pathogen and tumor challenge. Accumulating in vivo evidence reinforces the role of inflammasomes in CD8+ T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity. For example, NLRP3 activation in DCs enhances CD8+ T cell priming and tumor regression in murine models, while IL-18 deficient mice exhibit exacerbated colitis-associated carcinogenesis due to compromised CD8+ T cell responses [155, 156]. Critically, IL-1β overexpression in B16 melanoma models boosts CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity and suppresses tumor growth [122]. Moreover, NLRP3 ablation accelerates breast cancer progression by polarizing macrophages toward an immunosuppressive phenotype [104]. These in vivo findings validate that inflammasomes orchestrate CD8+ T cell activation to restrict tumorigenesis [157]. IL-1β acts upon T cells and therefore plays an important role in the regulation of the immune response, including the shaping of specific adaptive immunity. Knowing how IL-1β affects T cell function could help in the development of treatment. This pathway may be harnessed to enhance the tumor immune response and result in better cancer treatment outcomes.

Finally, it has also been observed that adjuvants such as alum induce IL-1β production [158]. CD8+ T cells do use IL-1β to organize immunological responses [153]. In a murine model, interestingly, IL-1β greatly increased the cytotoxic effect of CD8+ T cells and inhibited B16 melanoma progression [159]. Interestingly, IL1β is a tumor killer of Th1 cells, possibly resulting in immune suppression and tumorigenesis. These data show that the role of IL-1β in the TME is more complex, with both anti-tumor and pro-tumor activities contingent upon the conditions. In conclusion, IL-1β can be considered a novel immune adjuvant as it provides host recruitment of inflammatory cells to inflammatory sites and helps mature antigen-presenting cells. Also, it increases the ability of dendritic cells to augment T cell mediated immune responses. Here we present results which provide an intriguing possibility for IL-1β, as a target, for modulating immune responses in cancer and promoting anti-tumor immunity.

Other anti-tumor immunity

The NLRP3 inflammasome and the IL-1β pathway it regulates exhibit a dual function in tumor progression, serving as both facilitators and suppressors of cancer. For instance, NLRP3-driven IL-1β enhances immunosuppression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, whereas NLRP1 activation mitigates colitis-associated CRC by maintaining epithelial integrity [71, 160]. Multiple studies have documented increased levels of IL-1β in various cancers, including gastric cancer [161], head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [144], and breast cancer [162]. The expression of IL-1β is closely associated with tumor cell self-renewal and immunosuppression. Within the TME, IL-1β generated by MDSCs from the bone marrow can stimulate tumor angiogenesis. Furthermore, tumor-associated fibroblasts can identify DAMPs and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to the production of IL-1β, which promotes breast cancer cell proliferation and metastasis [104]. Nevertheless, IL-1β can also promote T lymphocyte-mediated tumor destruction and prompt the retreat of distant tumors. Research has demonstrated that introducing the IL-1β gene into a B16 melanoma model elevates the cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells and facilitates tumor regression [163]. Intramuscular injection of IL-1β also significantly reduces the rate of lung metastasis in mice with Lewis lung carcinoma, demonstrating anti-metastatic effects [143]. Furthermore, transplanted DCs can release the inflammasome into the surrounding draining lymph nodes (DLNs) after several days, releasing IL-1β to exert their effects [31]. However, whether IL-1β can migrate into the TME and regulate the tumor immune response is still unclear.

Recent clinical trials targeting inflammasomes demonstrate promising synergy with established immunotherapies. The NLRP3 inhibitor IFM-2427 is currently in Phase I/II trials for advanced solid tumors, showing reduced IL-1β secretion and enhanced infiltration of CD8+ T cells in 65% of patients, with partial responses observed in PD-1-refractory melanoma [164]. Similarly, the IL-1β monoclonal antibody canakinumab reduced lung cancer incidence by 67% in high-risk patients. When combined with the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab in NSCLC, it also improved progression-free survival [165]. In preclinical studies, the NLRP3/IL-1β pathway inhibitor OLT1177 (an oral NLRP3 inhibitor in clinical development) enhanced the efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma models, increasing tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells by 3.5-fold compared to anti-PD-1 monotherapy [166]. These strategies differ from conventional checkpoint inhibitors by simultaneously reprogramming immunosuppressive myeloid populations and activating innate-adaptive crosstalk [166]. A Phase Ib trial evaluating Dapansutrile, an oral NLRP3 inhibitor, in combination with nivolumab demonstrated a 38% objective response rate in refractory hepatocellular carcinoma, outperforming historical anti-PD-1 monotherapy controls [167].

Inflammasome inhibitors

Definitely, since the different regulatory functions exerted by the inflammasome pathway in malignant development, it is necessary to target the inflammasome in specific cell subpopulations to modulate this pathway. Targeting the inflammasome pathway with drugs that either inhibit or activate the inflammasome is also being developed by researchers, who acknowledge that such a pathway is important to provide anti-tumor therapy. By focusing on this targeting strategy, the immune response may be fine-tuned such that anti-tumor effects can be promoted while unintended pro-inflammatory consequences are minimized. These efforts constitute a continuous effort in the development of drugs to manipulate the inflammasome pathway, realizing its significance as a potential avenue for innovative and effective cancer treatment.

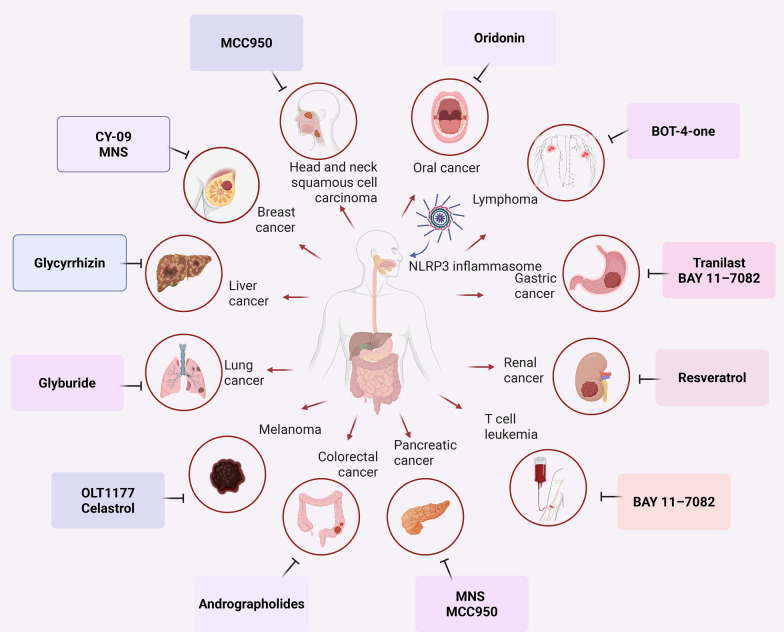

It has also been indicated that both macrophage AIM2 and DCs NLRP3 can contribute to tumorigenesis [168]. This highlights the importance of characterizing the function of the inflammasome in the different cell subsets of the TME. Nevertheless, little is currently known about the triggering of inflammasomes in specific TME subsets. Understanding what subsets of inflammasome contribute to tumor development in particular sets of tumors may also be helpful for the development of more effective therapeutic agents focused on the inflammasome in different types of tumors. Finally, we briefly summarized some tumor-targeted inflammasomes in the clinical trials (Fig. 3). These medicines have the potential to modulate the inflammasome pathway, and are useful for promoting the development of individualized and targeted cancer therapy. While inflammasome inhibitors hold promise for cancer therapy, their systemic suppression of immune pathways raises critical safety concerns. For example, NLRP3 inhibitors like MCC950 disrupt IL-1β/IL-18 signaling, which is essential for host defense against pathogens [169]. Preclinical studies report increased susceptibility to bacterial and fungal infections following NLRP3 blockade [170]. Similarly, clinical trials of IL-1β antagonists in cardiovascular diseases revealed a dose-dependent rise in fatal infections, underscoring the need for targeted delivery systems to minimize off-tissue effects [171]. Furthermore, AIM2 inflammasome inhibition may compromise antiviral immunity, as AIM2 is critical for detecting cytosolic DNA from viruses like HSV-1 [172]. These risks necessitate careful risk–benefit stratification in clinical applications. However, further research and clinical trials are needed to fully assess their effectiveness and safety for such tumor subtypes.

Fig. 3.

Inhibitors of various tumor inflammasomes in the clinical trials. Red arrows: The inflammasome pathway promotes cancer; black arrows: inflammasome inhibitor drugs have been reported to treat these cancers

NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors have been formulated for the management of non-malignant tumors and have demonstrated encouraging outcomes in cancer therapy. One such inhibitor is MCC950 (also known as CRID3), which specifically targets NLRP3 without affecting other inflammasome receptors [173]. MCC950 interacts with the Walker B motif in the NACHT domain, obstructing ATP hydrolysis and limiting NLRP3 activation [174]. This particular blockage has been confirmed in both the wild-type form and mutant NLRP3. Research has shown that MCC950 suppresses the cancer of the pancreas and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [175, 176]. Another inhibitor, CY-09, targets the NACHT domain akin to MCC950 and obstructs NLRP3-mediated tumor drug resistance and the suppression of EMT [177]. Tranilast is an inhibitor targeting the NACHT domain while also inhibiting signaling pathways such as TGF-β, MAPK, and NF-κB [178, 179]. Research has demonstrated that IL-1β displays significant anti-tumor efficacy against NSCLC, gastric cancer, and various other tumor cell types, resulting in reduced tumor proliferation and fibrosis [180, 181]. Other inhibitors that target the NACHT domain include 3,4-ethylene-β-nitrosostyrene (MNS) and oridolin [182]. Aridin, which has significant anti-tumor activity, acts through the PI3K/Akt pathway [183]. NLRP3 inhibitors show potential for the advancement of tailored therapeutics in cancer treatment. Still, additional investigation is necessary to thoroughly assess the effectiveness and safety of these inhibitors in specific subtypes of tumors through further research and clinical trials.

BAY 117082 has been demonstrated to trigger apoptosis in gastric cancer cells. To perform this action, it blocks the NF-κB signaling pathway, an important pathway in cancer cell survival and proliferation. Furthermore, BAY 117082 can successfully trigger apoptosis in gastric cancer cells by inhibiting this pathway and thus cause their death [184]. Additionally, MNS can significantly inhibit tumor cell invasion, migration, and proliferation in pancreatic cancer and breast cancer. These effects demonstrate that MNS may have a therapeutic use for treating cells as such. The underlying mechanism of MNS and its clinical potential for treating pancreatic and breast cancer will need to be further studied [185]. Inhibiting NLRP3, we have found that glyburide reduces inflammation-related lung tumorigenesis [186]. The inflammatory pathway that includes NLRP3 is crucial. Glyburide can effectively reduce inflammation and subsequently inhibit lung tumorigenesis by inhibiting NLRP3. The discovery highlights the potential of blocking the inflammasome pathway as a new approach to creating anti-tumor medications. As shown previously, BAY 117082 kills T cell leukemia cells through the inhibition of the NF-κB pathway [184, 187]. It is widely known that the NF-κB pathway plays an essential role in promoting cell survival and proliferation in cancerous cells. BAY 117082 can induce apoptosis and thus lead to the cell death of T cell leukemia cells via inhibition of this pathway. These include the potential inhibitors and mechanisms of their action and may be valuable to identify when developing anti-tumor therapeutics that target the inflammasome [188, 189]. However, more research is needed to determine if they work and are safe in different cancer types before they can be considered as a potential therapy.

Resveratrol has shown that inhibition of NLRP3 expression in kidney tumor cells, implying that the NACHT domain could be a major site for inhibitory activity [189]. A further potential pathway to targeting the inflammasome pathway is OLT1177. This inhibitor can break the IL-1β/IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway to reduce the immunosuppressive capability of MDSCs, and inhibit tumor cell proliferation [190]. The anti-tumor impact of OLT1177 plus PD1 has been shown as augmented in synergy [191]. In addition to inhibiting kidney tumor cells, resveratrol has shown inhibitory effects on NLRP3 inflammasome activation in many other situations. For example, it showed potential to limit myocardial damage and diminish the systemic inflammatory response by doxorubicin, a chemotherapy drug that, among other toxic effects, is cardiotoxic. It has been shown that resveratrol also has efficacy against radiation therapy induced inflammation of the intestinal mucosa. The results presented herein demonstrate that resveratrol displays profound anti-inflammatory activity, which may be useful as a therapeutic agent for various inflammatory diseases, including renal carcinoma cells [192]. The proliferation and survival of lymphoma cells have been inhibited by BOT-4-one [193]. Investigated so far as an anti-cancer agent, particularly against lymphoma, which is a malignancy of the lymphatic system, this chemical is sought to be used. BOT-4-one also has the potential to inhibit the growth and survival of lymphoma cells, which may be useful in treating this type of cancer. However, further research and analysis are necessary to understand the mechanisms of action and potential therapeutic applications of BOT-4-one in lymphoma treatment. In addition, triptolide has been shown to inhibit the migratory and invasive activity of melanoma cells [194]. Melanoma cells are efficiently inhibited from migrating and invading through targeting the melanoma derived NLRP3/IL-1β pathway from macrophages by triptolide. It is highly influential in the advancement and spread of melanoma. In doing so, triptolide can specifically knock down this pathway and block the migratory and invasive capacity of melanoma cells. Result suggests that triptolide can be a potential therapeutic alternative for melanoma, one of the most aggressive forms of skin cancer.

Emerging evidence suggests that pharmacological interventions such as NSAIDs (aspirin) suppress NLRP3 inflammasome activation by reducing COX-prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production, thereby attenuating tumor-associated inflammation [195]. Conversely, corticosteroids like dexamethasone inhibit inflammasome assembly by downregulating NF-κB dependent priming signals in murine melanoma models [196]. Antibiotics such as vancomycin alter gut microbiota composition, indirectly modulating NLRP3 activity in CRC via microbiota-derived metabolites [197]. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting inflammasomes through existing drugs. However, there has been limited exploration of AIM2 inhibitors relative to NLRP3, only two drugs with a non-specific inhibitory effect have been identified. As a good candidate characterized for its wide range of anti-inflammatory activity, methylene blue can selectively target NLRP3, NLRC4, AIM2, and non-classical inflammasomes [198]. Other non-specific inhibitors, such as andrographolide, inhibit translocation of AIM2 to the nucleus, reduce DNA damage, and decrease the inflammatory response in irradiated lung tissue [199]. The therapeutic effects of several compounds, including compounds such as glycyrrhizin acid [200], andrographolide [201], and methylene blue on breast cancer [202], colon cancer, and liver cancer have been shown. To date, however, there are few specific inhibitors available against NLRC4. There are two identified inhibitors of the inflammasome that are also effective against NLRC4, albeit with weaker specificity. Inhibition of NLRC4 and NLRP3 activation by sulforaphane reduces inflammation [203]. As a broad-spectrum inflammasome inhibitor, methylene blue has the ability to inhibit NLRC4, NLRP3, AIM2, and non-classical inflammasomes. In animal studies, methylene blue administration significantly improved survival rates in mice induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) by inhibiting inflammasome activation. It’s noteworthy that several NLRP3 inhibitors target the NACHT domain, which is also expressed in the NLRC4 inflammasome. Although several inhibitors of NLRP3 have been developed, only a small number of medications have been utilized in clinical studies. The area of targeted drug development for inflammasome activation necessitates additional research and attention. Further studies are needed to identify more specific inhibitors against NLRC4 and explore their therapeutic potential in various inflammatory and disease conditions.

Comparative analysis of inflammasome inhibitors

Recent advances in NLRP3-targeted therapies highlight both promises and challenges. For instance, MCC950, a potent NLRP3 inhibitor, synergizes with anti-PD1 in melanoma by reducing myeloid-derived suppressor cell infiltration [174]. However, its clinical translation is limited by poor oral bioavailability and off-target effects on non-immune cells. In contrast, Tranilast, an anti-fibrotic drug repurposed for NLRP3 inhibition, shows efficacy in pancreatic cancer models by suppressing TGF-β signaling, yet its dose-dependent toxicity necessitates careful optimization [204]. Notably, CY-09 emerges as a promising candidate due to its specificity in blocking NLRP3 ATPase activity, effectively reversing EMT in breast cancer [205]. These findings underscore the need for isoform-selective inhibitors and biomarker-driven patient stratification.

Specific inhibitors targeting NLRC4 are currently limited. Nevertheless, there are a few inflammasome inhibitors that have demonstrated effectiveness against NLRC4, although with weaker specificity. One such inhibitor is sulforaphane, capable of inhibiting both NLRC4 and NLRP3 activation, resulting in a reduction in inflammatory responses [203]. Methylene blue, acting as a broad-spectrum inflammasome inhibitor, has been shown to block the activation of NLRC4, NLRP3, AIM2, and non-classical inflammasomes. The administration of methylene blue in animal studies substantially increased the survival rates of mice that were induced by LPS by inhibiting inflammasome activation [198]. Although numerous inhibitors of NLRP3 and NLRP4 have been created, only a small number of medications have been implemented in clinical trials [198]. The development of targeted drugs for inflammasome activation is an active area of research, with increasing attention being directed towards studying the inflammasome pathways. Further research is imperative to identify more specific inhibitors against NLRC4 and explore their therapeutic potential in various inflammatory and disease conditions.

Recent advances in targeting inflammasomes have yielded promising inhibitors, though clinical translation remains challenging. MCC950 (CRID3), a selective NLRP3 inhibitor, demonstrated efficacy in preclinical models of pancreatic cancer and head/neck squamous cell carcinoma by suppressing IL-1β and tumor growth [206, 207]. However, Phase I trials revealed dose-dependent hepatotoxicity, limiting its therapeutic window [208]. Similarly, CY-09, another NLRP3-targeting compound, showed reduced tumor drug resistance in murine models, but its poor bioavailability and off-target effects on NLRC4 highlight the need for structural optimization [205]. Tranilast, an NLRP3/TGF-β dual inhibitor, reduced fibrosis in NSCLC patients but caused gastrointestinal side effects in 22% of participants [178]. Oltipraz, an AIM2 suppressor, is under evaluation for colitis-associated cancer yet its nonspecific inhibition of NF-κB raises concerns about immunosuppression [209]. While methylene blue broadly inhibits AIM2/NLRC4, its neurotoxicity at high doses underscores the importance of isoform-specific designs [210]. Furthermore, we systematically summarized pharmacologic agents targeting inflammasome pathways (including NLRP3, AIM2, and NLRC4 subtypes) along with their molecular mechanisms such as ATPase inhibition, structural domain blockade, and signaling pathway modulation, which demonstrate therapeutic potential across multiple malignancies including pancreatic, colorectal, breast, and melanoma cancers (Table 3). These findings emphasize the dual challenge of balancing efficacy and safety while addressing inflammasome redundancy in tumors.

Table 3.

Molecules modulating inflammasome function and their mechanisms in cancer

| Interventions | Target inflammasome | Mechanism of action | Cancer type | Clinical status | NCT numbers | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCC950 | NLRP3 | Inhibition of ASC oligomerization | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | Preclinical | N/A | [144] |

| MCC950 | NLRP3 | Inhibits ATPase activity of NLRP3 | Pancreatic, HNSCC | N/A | N/A | [169] |

| CY-09 | NLRP3 | Binds NLRP3 NACHT domain, blocks activation | Colorectal, NSCLC | Preclinical | N/A | [177] |

| Tranilast | NLRP3 | Suppresses NLRP3/IL-1β/TGF-β signaling | Breast, gastric | N/A | N/A | [178, 179] |

| OLT1177 | NLRP3 | Inhibits NLRP3-ASC interaction | Melanoma, breast | Phase II | N/A | [191] |

| Andrographolide | AIM2 | Reduces AIM2 nuclear translocation | Radiation-induced lung injury | Phase II | NCT01993472 | [201] |

| Sulforaphane | NLRC4/NLRP3 | Inhibits NLRC4 oligomerization | Colorectal | Preclinical | NCT01265953 | [203] |

| Sulforaphane | NLRC4/NLRP3 | Inhibits NLRC4 oligomerization | prostate | Preclinical | NCT01228084 | [203] |

| Resveratrol | NLRP3 | Suppresses NLRP3 via SIRT1/AMPK pathways | Renal, melanoma | N/A | N/A | [189] |

| BAY 11-7082 | NLRP3 | Inhibits NF-κB/NLRP3 axis | Gastric, leukemia | Preclinical | N/A | [184] |

| Methylene Blue | NLRP3/NLRC4/AIM2 | Broad-spectrum inflammasome inhibition | Breast | Preclinical | NCT02084784 | [198] |

| Methylene Blue | NLRP3/NLRC4/AIM2 | Broad-spectrum inflammasome inhibition | colorectal | Complete | NCT01694966 | [198] |

| Triptolide | NLRP3 | Inhibits NLRP3/IL-1β in macrophages | Melanoma | Preclinical | N/A | [194] |

Conclusions

Comprehensive summaries of the mechanisms that activate both classical and non-classical inflammasome pathways are provided in this review. We also investigate the synergistic role of inflammasomes in immune cells for antitumor activity. Lastly, we examine inhibitors that are presently in clinical trials and target tumor inflammasome pathways.

Inflammasomes are multiprotein complexes that activate the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and IL-18, which are essential for modulating innate immune responses. Inflammasome activation occurs in two stages: priming, in which immune cells are sensitized by the upregulation of inflammasome components and cytokines via PRRs such as TLRs, and activation, where sensors detect danger signals (PAMPs or DAMPs), triggering an inflammatory response. The activation of inflammasomes recruits additional immune cells to coordinate a robust immune response, as immune cells, such as macrophages, dendritic cells, and T cells, express them.

Inflammasomes can exert both pro-tumor and anti-tumor effects. The dual roles of inflammasomes in cancer progression stem from their cell-type-specific signaling networks and dynamic interactions within the TME. For instance, NLRP3 exhibits pro-tumor effects in breast cancer by fostering immunosuppressive myeloid cell infiltration, whereas it exerts tumor-suppressive functions in colitis-associated CRC through IL-18-mediated epithelial repair. This dichotomy can be exploited therapeutically by developing cell-selective inflammasome inhibitors or combining inflammasome modulation with immune checkpoint blockade. Recent advances in single-cell transcriptomics now enable precise mapping of inflammasome activation states across immune cell subsets, paving the way for biomarker-driven personalized therapies. They can promote tumor progression by creating an immunosuppressive environment, but also enhance anti-tumor immunity by activating cytotoxic immune cells. Inflammasome inhibitors targeting various components, such as sensors, ASC, caspase-1, and GSDMD, are currently in clinical trials. These inhibitors have the potential to enhance anti-tumor immune responses and modulate the TME.

Inflammasomes exhibit cancer-type-specific duality, necessitating precision in therapeutic targeting. NLRP1 promotes melanoma proliferation via anti-apoptotic pathways, yet suppresses gastrointestinal tumorigenesis through IL-18-mediated epithelial protection. NLRP3 accelerates head/neck squamous carcinoma via caspase-1-dependent EMT, while its absence exacerbates colitis-associated carcinogenesis. AIM2 demonstrates tumor-suppressive activity in breast cancer via NF-κB inhibition, paradoxically enhancing cutaneous squamous carcinoma through angiogenesis promotion. Clinical trials with NLRP3 inhibitors underscore the imperative for subtype-stratified approaches. Future research must delineate tumor-microenvironment-specific inflammasome interactomes to optimize immunotherapy regimens.

In summary, understanding the activation mechanisms of inflammasomes and the collaborative roles of immune cells is crucial for developing effective cancer immunotherapies. Recent single-cell RNA sequencing studies reveal that inflammasome activation is spatially heterogeneous within tumors. For example, NLRP1 is upregulated in lung adenocarcinoma-associated fibroblasts, correlating with poor prognosis, while AIM2 silencing in renal carcinoma suppresses metastasis via autophagy induction. Such spatial and cellular specificity underscores the need for cell-type-targeted therapies, a paradigm shift from systemic inflammasome inhibition. Although NLRP3 is the main focus for inflammasome inhibitors, other components of inflammasomes are also important and could offer additional therapeutic possibilities. By enhancing efficacy and addressing drug resistance, inflammasome inhibitors may serve to augment existing cancer therapies, including immunotherapies, chemotherapy, and targeted treatments. Future research may uncover new inflammasome targets, thereby broadening treatment approaches and improving patient outcomes. The burgeoning field of inflammasome immunotherapy presents significant potential for more personalized and effective cancer treatments.

Acknowledgements

The authors recognize the utilization of BioRender for the creation of the schematics in Figs. 1, 2, 3.

Author contributions

LH, XC and RL wrote the manuscript. DN, WB, LY, XD, JT, YL and HZ collected information and prepared figures and tables. All authors edited and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82203377 to Yanwei Lu; 82473238 to Haibo Zhang), Zhejiang Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: LQ22H160036, to Yanwei Lu; LY24H160022, to Haibo Zhang).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors Luanluan Huang, Xiaoyan Chen, and Ruiqi Liu have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jianming Tang, Email: 15900792812@163.com.