Abstract

Background

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a chronic progressive disease affecting the central nervous system (CNS) because of persistent measles virus (MeV) infection. The disease presents with a range of symptoms, starting with gradual cognitive and motor decline, progressing to coma, vegetative state, and typically resulting in death within 3–4 years of clinical onset. The incidence of SSPE is inversely related to vaccination coverage and its pathogenesis remains poorly understood. The primary risk factor is infection by the wild type of measles virus, particularly in individuals who may be predisposed to infection due to a lack of herd immunity or immunosuppressed states. Furthermore, the risk of developing SSPE increases with the younger age at which a person contracts measles.

Case presentation

We provide a description of the disease, characterizing its clinical course, diagnostic work-up and treatment options. We will also present a series of cases observed at the Santobono-Pausilipon Children’s Hospital, in Naples, Italy, highlighting both typical and atypical presentations, with a particular emphasis on the pharmacological and neurosurgical treatments for the condition.

Conclusions

The objective of this study is to raise awareness about the increasing prevalence of conditions following the SARS-Cov2 pandemic, with an emphasis on the importance of vaccination adherence as the only effective prevention method for SSPE.

Keywords: Measles, Vaccine, SSPE, Seizures, Interferon alpha

Background

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a chronic, slowly progressive and often fatal neurodegenerative disease caused by persistent measles virus (MeV) infection [1]. SSPE is characterized by gradual cognitive and motor decline with variable progression and high mortality rates. Death can typically occur from 1 to 3 years after clinical onset [2]. The disease usually occurs 7–10 years after measles infection but the latency period varies from 1 month to 27 years [3]. It predominantly affects children and young adolescents. There is no clear gender prevalence, but males tend to be more affected than females at a ratio of 2.8:1 [4]. Since the MeV vaccine is approved from 12 months of life, is when the patient is most vulnerable to infections due to lack of immunity [5]. The worldwide incidence of SSPE changes with geographic disparity in terms of vaccination coverage [5]; ranges from approximately 0.2 to 40 cases per million people per year. The incidence was reduced by approximately 82–96% between 2000 and 2016 in countries achieving a sustained high level of vaccination coverage [6]. However, the global elimination of measles virus infection has declined significantly in recent years, peaking at 120 cases per million in 2019 [5, 7]. In addition to vaccine refusal, reduced vaccination programs during the COVID-19 has increased the risk of SSPE [8]. The incidence, according to US data, is 4–11 per 100,000 cases of measles [5, 9]. Children under one year have a measles rate 18 times higher than those over five [3, 10]. The younger a child is when infected with measles, the higher the risk of developing SSPE [10, 11]. The main risk factors that make children more vulnerable to contracting measles and then to the risk developing of SSPE are also a low parental education level, lack of measles vaccination, low socioeconomic status, more siblings and higher birth order (a higher probability of being exposed to someone with measles before the age of 5 years) [12, 13]. In addition, children with HIV infection or those who are born to infected mothers have an increased risk of developing SSPE after measles infection [14, 15]. Its pathogenesis is not well understood but may involve hypermutated MeVs combined with an inadequate cellular response [5, 16]. Mutations that alter viral envelope glycoproteins, particularly the F protein and the M protein, are thought to be responsible for neurovirulence [17, 18]. After primary measles infection, the virus enters the central nervous system (CNS). Since human neurons do not express receptors for measles virus, mutations in envelope glycoproteins allow it to enter neurons, help the replicating virus persist in neuronal cells, spread through synapses and evade neutralizing antibodies [19]. SSPE can develop in particularly susceptible hosts [1]. Susceptibility, according to some studies [20], may be due to the imbalance between high levels of cytokines promoted by Th2 cells (IL-4 and IL-1b) and low levels of cytokines promoted by Th1 cells (IFN-α, IL-2, IL-10 and IL-12), which promote a humoral response rather than a cytotoxic response and allow virus self-replication and persistence in neuronal cells. Persistent virus replication causes progressive neuronal destruction. The virus targets not only gray matter neurons but also oligodendrocytes and, to a lesser extent, astrocytes [21–23].

Clinical features and diagnosis

SSPE typically begins with progressive cognitive deterioration (e.g. low school performance), personality changes and behaviour abnormalities [19, 24]. This is followed by paroxysmal movements, myoclonic jerks (involving the head, trunk and limbs) and/or negative myoclonia (head drops). Periodic myoclonus can also lead to gait disturbances or repeated falls. The disease progresses to motor decline, focal paralysis, seizures, autonomic failure and rigidity, then to akinetic mutism and death [5, 25–27]. The clinical course of the disease is divided into four stages [28] (see Table 1). On average, clinical onset is 6 years after MeV infection, usually between 8 and 11 years [29]. With respect to the rates of clinical manifestations in individuals with SSPE, motor regression occurs in 100% of cases, cognitive impairment in 86%, myoclonus in 74%, generalized seizures in 16%, and focal seizures in 10% of affected children [1, 23, 30–32]. Symptoms that represent an atypical onset include isolated psychiatric disorders, difficulty in walking, isolated extrapyramidal signs, drug-resistant seizures or ophthalmological abnormalities (optic atrophy) [33]. Atypical presentations account for 10% of cases and does not follow the classical course of the disease [34].

Table 1.

SSPE’s staging: the clinical course is divided into four stages from behavioural changes to motor impairment and finally to vegetative state/coma and death

| Stage | Clinical manifestations |

|---|---|

| Stage I | Personality changes, strange behaviour, failure in school |

| 1 A | Mild mental and/or behavioural changes |

| 1B | Marked mental changes |

| Stage II | Massive, repetitive and frequent myoclonic jerks, seizures and dementia |

| 2 A | Myoclonus and/or other involuntary movements and epileptic seizures |

| 2B | Focal deficits (speech disorders, loss of vision, and limb weakness) |

| 2 C | Marked involuntary movements, severe myoclonus, or focal deficits enough to impair full daily activities |

| 2D | Akinetic mutism, vegetative state, decerebrated, decorticated rigidity, or coma |

| Stage III | Rigidity, extrapyramidal symptoms and progressive unresponsiveness |

| Stage IV | Coma, vegetative state, autonomic failure and akinetic mutism |

Diagnosis is suspected based on clinical presentation and corroborated by immunological evidence of raised cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) measles virus antibodies. Electrophysiological and neuroimaging exams may be useful during the diagnostic work-up; however, they do not always correlate with the clinical stage of the disease and have low sensitivity and specificity for SSPE [35, 36]. Brain biopsy is rarely performed (only in exceptional cases where CSF is not diagnostic) [19]. Diagnosis typically requires two major and one minor criterion according to Dyken’s modified criteria (see Table 2). Major markers include clinical history and elevated measles antibody titer in the CSF. Minor markers consist of a typical EEG, increased CSF IgG, brain biopsy, and molecular diagnostic tests for the mutated measles virus genome [37].

Table 2.

Dyken’s diagnostic criteria: two major plus one minor criteria are usually needed. If the presentation is atypical, 5 and/or 6 criteria May be needed

| SSPE diagnostic criteria | Major |

|---|---|

| 1 | Elevated CSF measles antibody titers |

| 2 |

Typical or atypical clinical history Typical: acute rapidly progressive; subacute progressive, chronic progressive, chronic relapsing–remitting Atypical: seizures, prolonged stage I, unusual age (infancy/adult) |

| Minor | |

| 3 | Typical EEG (periodic complexes) |

| 4 | Elevated CFS globulin levels |

| 5 | Brain biopsy |

| 6 | Molecular diagnostic test to identify the MeV mutated genome |

Laboratory investigations

Compared to other techniques, measles antibody detection in CSF using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) has demonstrated superior performance, with 100% sensitivity, 93.3% specificity, and a 100% positive predictive value in patients with SSPE [38]. Since the measles virus is not released extracellularly into the CNS, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for measles in CSF is typically negative. As a result, relying solely on CSF PCR for measles may lead to a delayed diagnosis. Conversely, oligoclonal bands in CSF are usually positive. While this finding is not specific to SSPE, the IgG index in CSF is markedly elevated in this disease [38].

Electrophysiological investigations

Electroencephalography (EEG) has great utility in diagnosis because it shows a typical pattern, which is found in approximately 65–83% of individuals with SSPE [39]. The pathognomonic pattern consists of periodic, generalized, bilaterally symmetrical and synchronous complexes. As the disease progresses, the complexes become periodic and the background activity becomes poorly configured, with the amplitude progressively decreasing. Some features of the electroencephalographic pattern overlap with those of epilepsy syndromes, such as Lennox–Gastaut syndrome (LGS), electrical status epilepticus during slow-wave sleep (ESES) and epileptic spasms [40]. Thus, a differential diagnosis is essential. Some experts propose that EEG patterns change with disease stages as in the table below (see Table 3) [40]:

Table 3.

Clinical staging matched to EEG: the EEG background also correlates with the clinic starting from a normal background with over-inscription of the periodic complexes up to a de-structuring of the EEG activity

| Stages 1 A, 1B | Normal background, more common presence of periodic complexes and anterior delta |

|---|---|

|

Stages 2 A, 2B, 2 C, 2D |

Normal background, much more common presence of periodic complexes and anterior delta Focal slowing in 50% of cases Epileptogenic activity increasing from stages 2 A to 2 C, less evident by stage 2D |

| Stage 3 | Abnormal background, less common presence of periodic complexes and anterior delta |

| Stage 4 | Abnormal background, absence of periodic complexes and anterior delta |

Neuroimaging

While brain MRI is not definitive for diagnosis, it remains valuable, particularly in the intermediate and final stages of the disease. An initial MRI might be negative but does not exclude the condition. As the disease advances, the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, brainstem, and ventricular white matter may be involved. In the latter stages, the thalamus and corpus callosum are affected, leading to widespread cortical atrophy [41, 42]. MRI findings can progress independently of clinical symptoms [32].

Treatment options

At present, there is no clear evidence on treatment for SSPE [43, 44]. Standard treatments include isoprinosine monotherapy and/or isoprinosine in combination with ribavirin (for their immunostimulant, anti-viral properties and good tolerability), as well as intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, intrathecal α-interferon (α-IFN) and amantadine.

Isoprinosine, also known as methisoprinol, is an antiviral agent which restore deficient responses in immunosuppressed patients enhancing T-cell lymphocyte proliferation and activity of natural killer cells, increasing levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. It has been demonstrated that inhibit growth of several viruses, affecting viral RNA levels. In support of the above-listed treatments, symptomatic antiseizure medications should be mentioned. Interferon alpha is used as an immunomodulatory drug. Interferon alpha therapy has historically been administered intrathecally or intravenously, though its efficacy remains in question [45]. In 1986, Panitch performed the first intraventricular administration using an Ommaya reservoir connected to a catheter placed within the frontal horn of the right lateral ventricle, achieving satisfactory results [1]. Following this initial report, additional studies have utilized the same surgical technique and have been documented in the literature [45]. Interferon alpha therapy is currently administered via the intrathecal route every week for symptom reduction [45, 46].

Case presentation

This presentation includes four clinical cases followed up at at Santobono-Pausilipon Children’s Hospital of Naples and retrospectively enrolled after being diagnosed with SSPE based on Dykens’ criteria.

All patients underwent diagnostic lumbar puncture, EEG and brain MRI. CSF, blood, urine and oral fluid of all patients were sent to the WHO/LabNet National Reference Laboratory (NRL) for serological and molecular diagnosis. The level of specific measles IgM and IgG was tested by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), the level of neutralizing antibody by plaque reduction neutralisation test (PRNT80) and the presence of measles RNA by Real Time RT-PCR for measles were tested. Of those presented, only one patient was diagnosed at another centre and was followed up at our hospital (Patient 2).

Patient 1

A 5-year-old Ukrainian boy presented with gait disturbance, stumbling, and occasional falls over the past month, along with left upper limb motor impairment and speech difficulties. His medical history was unremarkable, and he had not been regularly vaccinated. Neurological examination showed reduced spontaneous movement on the left side, increased muscle tone, and an exhausted Achilles reflex on the left. Speech could not be fully assessed due to a language barrier but was reportedly impaired by the mother.

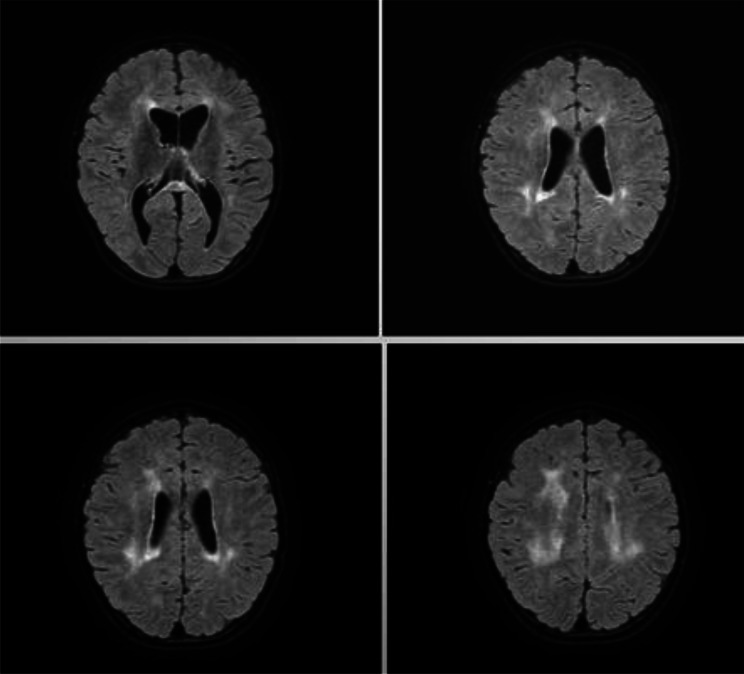

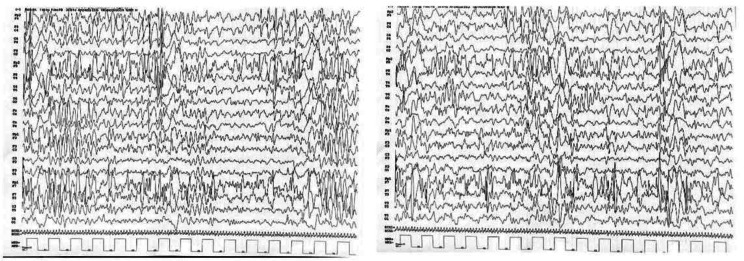

The results of laboratory investigations, including inflammatory indices and serology data for EBV IgM, EBV VCA, EBNA, EA IgG and the TORCH complex, were all within normal limits. A brain and spinal cord MRI revealed T2 FLAIR hyperintense signal alteration of the periventricular white matter, corona radiata and semioval centers with bilateral distribution involving U-shaped fibers; similar signal alteration was observed at the level of the corpus callosum, which was globally thinned; this blurred alteration was also present at the putamen, caudates, thalami and mesencephalic regions; reduction in encephalic tissue trophism of the midbrain, pons and upper and middle cerebellar peduncles, associated with enlargement of the ventricular system. (see Fig. 1). The EEG showed synchronous and sub-continuous multifocal epileptiform abnormalities prevalent in the frontal and temporal areas (> left side), accentuated during sleep (see Fig. 2). Based on the clinical/neurophysiological findings, valproic acid therapy was started.

Fig. 1.

First brain MRI performed in patient 1: Hyperintense in T2 FLAIR signal alteration of the periventricular white matter, corona radiata and semioval centres with bilateral distribution involving U-shaped fibers; similar signal alteration was observed at the level of the corpus callosum, which was globally thinned; this blurred alteration was also present at the putamen, caudates, thalami and mesencephalic regions; reduction in encephalic tissue trophism of the midbrain, pons and upper and middle cerebellar peduncles, associated with enlargement of the ventricular system

Fig. 2.

SSPE’s typical EEG: EEG showing periodic complexes

During in-depth analysis, the following exams were also performed: -nerve conduction studies, - SNP array and NGS panel for leukodystrophies, -metabolic examinations, including urinary amino acid assays, urinary organic acid and acylcarnitine levels, Barry’s test (glycosaminoglycans), very long-chain fatty acid (VLCFA) levels, and urinary oligosaccharide levels, all of which were within normal limits.

At follow-up, there was a slight improvement in walking, but worsening behavior and stable speech difficulties. The psychiatric evaluation showed hyperactivity, impulsivity, inattention, executive function deficits, easy distractibility, low motivation, reduced adaptability to frustration, and impulsive, defiant traits. The new MRI matched previous results, showing the same T2 and FLAIR hyperintense signal changes. Serial EEGs revealed a deconstruction of electrical background activity, with sub-continuous epileptiform anomalies prevailing over the left frontal and temporal regions, which were structured in periodic complexes of spikes and waves of 2–4 Hz.

The child was readmitted to the emergency department due to a reported visual disturbance, described as difficulty recognizing objects, which had begun 7–10 days earlier, leading to a critical episode. During his new hospital stay, he underwent brain MRI, which revealed progression of hyperintense signal alterations in T2-FLAIR, with bilateral involvement of the lower occipital lobes. A particular subcortical location was observed in the left calcarine region, with extension to the Gratiolet optical radiation bilaterally. There was also evidence of shaded altered hypersignals in the long TRs at the subcortical deep white matter levels in the left frontal and left temporal-opercular regions. Compared with the controls, the occipital and frontal regions presented signs of progressive atrophy, with consequently greater amplitudes of equal-level CSF spaces (see Fig. 3). For suspected mitochondrial disease, a muscle biopsy was also performed, with histopathological findings within normal limits.

Fig. 3.

Second Brain MRI perfomed in patient 1: The exam revealed bilateral involvement of the lower occipital lobes and particular subcortical localization in the left calcarine region with extension to the Gratiolet optical radiation bilaterally, especially on the left

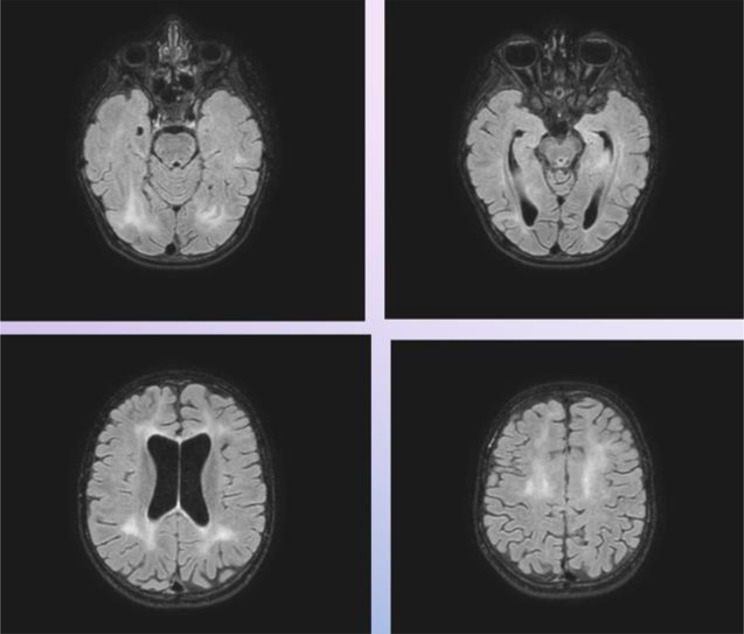

An anamnestic investigation showed the patient had measles in their first year. A spinal tap with cytochemical examination, film array for meningoencephalitis, and CSF culture revealed elevated measles immunoglobulin in both CSF and serum. Diagnosed with SSPE, the child received a neurosurgical pump for intrathecal interferon alpha at 250,000 IU/day alongside antiseizure therapy. Measles genome was not detected in CSF specimens; RT-PCR for measles is rarely positive in CSF. The serological profile shows no measles infection but the high measles IgG titer in blood and CSF may be indicative of a reactivation of the virus [39]. The level of neutralizing antibody by plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) confirms that both blood and CSF have high levels of IgG neutralizing antibodies against measles. After treatment, there was a progressive improvement in the neuroradiological and clinical findings (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Last brain MRI performed in patient 1: Brain MRI performed after neurosurgical treatment revealed resolution of the previously reported cortical and subcortical cytotoxic alterations in both occipital lobes and in the left middle-inferior frontal area, where signs of glial atrophy occurred

Patient 2

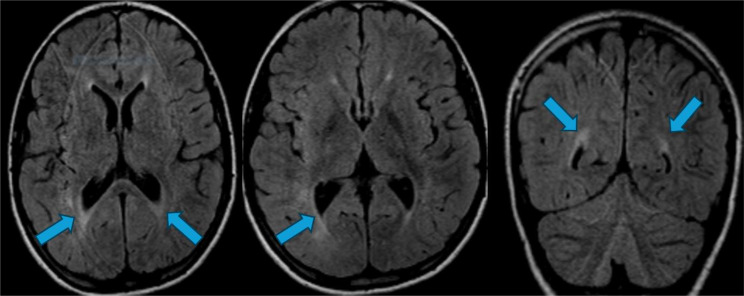

The second clinical case involved a 15-year-old boy admitted for treatment and follow-up after a diagnosis elsewhere. He had a sudden generalized tonic-clonic seizure. His family history was unremarkable, and he received the MPR vaccination on schedule. He had measles between ages 3 and 5, and normal psychomotor development until the first seizure. After the seizures began, he experienced progressive cognitive decline. A neurological exam revealed severe gait impairment, only manageable with double support. Serial EEGs showed slow periodic complexes in the context of poorly organized background activity. In correspondence with the EEG abnormalities, the child manifested ballistic high-amplitude movements. Following the diagnostic lumbar puncture, the presence of positive measles IgG in the CSF was detected. Based on clinical history, electrophysiological and neuroimaging findings, and measles antibody positivity, a diagnosis of SSPE was confirmed. The patient subsequently received an intrathecal infusion of Interferon-alpha 2b via an Ommaya-type reservoir. The patient underwent surgery to remove the Ommaya-type reservoir, an electronic pump implant was inserted for intraventricular delivery of interferon (see Fig. 5). The patient uses a monthly pump supplemented with 9 million IU of interferon.

Fig. 5.

Brain CT: Examination performed after electronic pump implantation for intraventricular delivery of interferon

Patient 3

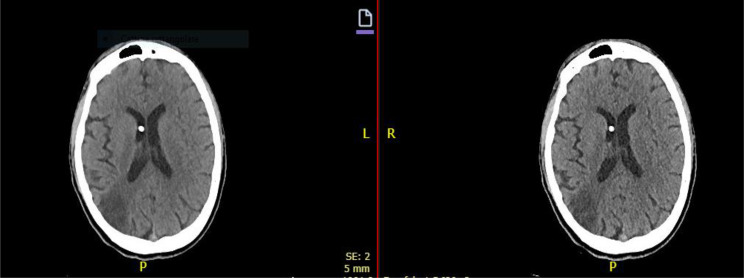

An 11-year-old girl was followed at our hospital for drug-resistant epilepsy and was treated with phenobarbital, levetiracetam and vagus nerve stimulator implantation. The patient was admitted again for increased seizure frequency and psychomotor regression associated with visual hallucinations. The neurological examination on admission revealed continuous clonic seizures involving the face and four limbs. Therefore, the patient underwent EEG, which revealed periodic complexes of generalized burst epileptic abnormalities. Based on the evolution of the EEG picture, the presence of clonic seizures and visual hallucinations and the suspicion of epileptogenic encephalopathy due to slow viruses, she was subjected to diagnostic spinal tap. Measles IgG was detected in the CSF and serum. The patient then underwent brain and spinal MRI with contrast: FLAIR sequence shows elevated signal areas in the deep frontal and right paratrigonal white matter. Modest hyperintensity of the white matter is also present in the posterior periventricular area” (see Fig. 6). Carbamazepine was then added. At the subsequent follow-up evaluation, the patient presented with marked asthenia and adynamia. She alternated moments of vigilance to torpor. She was unable to walk and her speech was limited to a few words. Her comprehension level was low, even for simple tasks.

Fig. 6.

Brain MRI performed in patient 3: T2 FLAIR hyperintensity of the white matter in the posterior periventricular area (see blue arrows)

She was subsequently readmitted to the hospital and underwent neurosurgery, which involved using an interferon alpha infusion pump for intrathecal administration with the proximal catheter positioned in the spinal subarachnoid space.

Patient 4

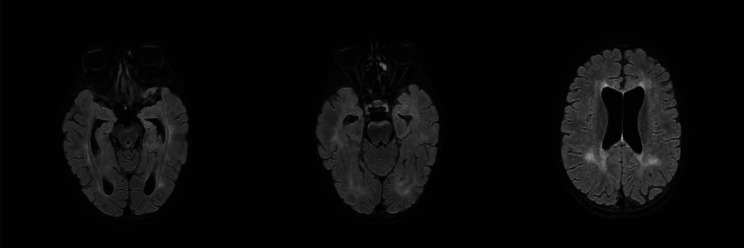

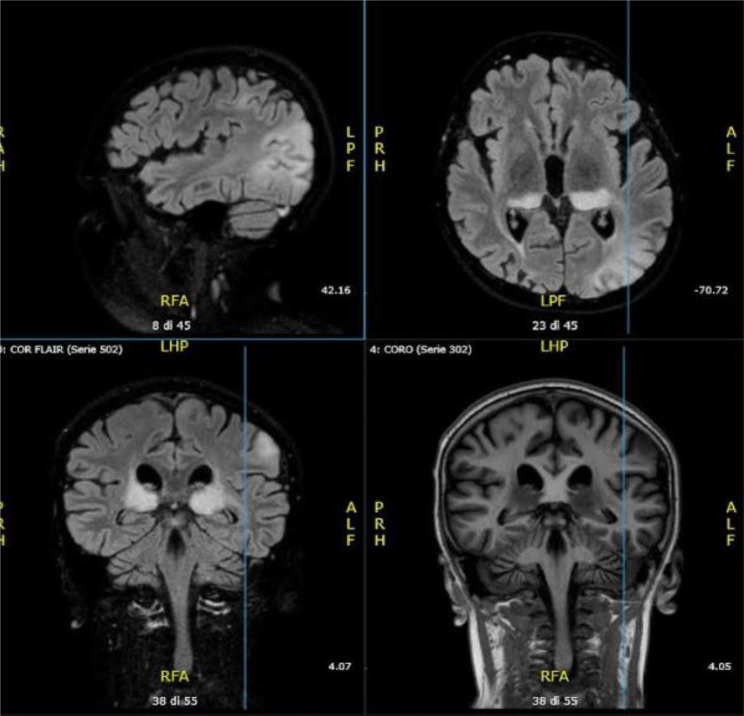

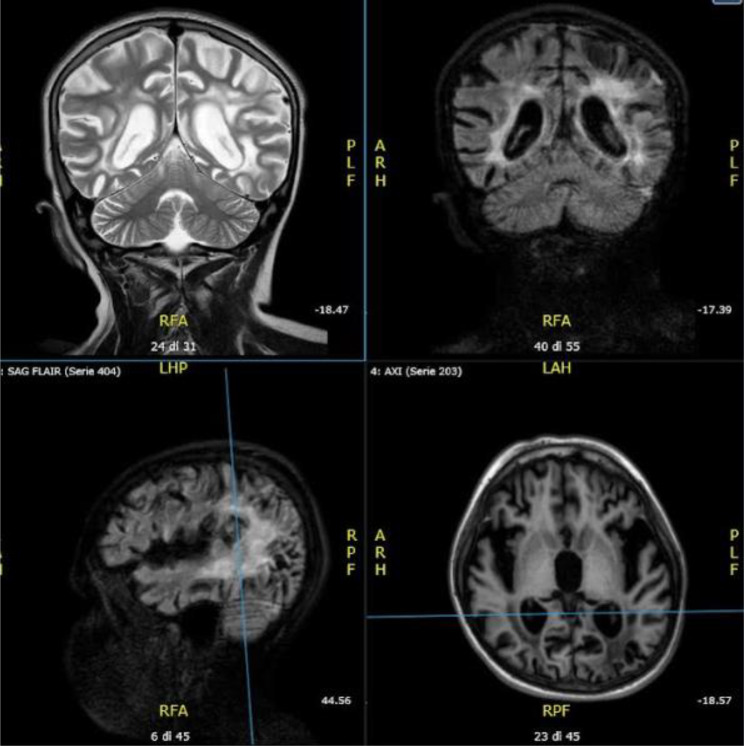

The fourth clinical case involves an 11-year-old boy from Ukraine. Family and personal history were unknown until adoption at the age of 6-year-old. Clinical onset was with epileptic seizures in sleep; brain MRI at the time was within normal limits. The neurological examination at the time was unremarkable, with uncertain intellectual impairment. Epilepsy progressively worsened with atonic seizures and frequent falls. Eventually, visual deficits like cortical blindness, hallucinations, motor stereotypies, cognitive impairment, and extrapyramidal and cerebellar signs appeared, until the onset of bed rest. Brain MRI revealed multiple areas with altered signals in the bilateral thalamic, left frontal-parietal and bilateral temporal-occipital cortical areas. These areas showed a high signal in long TR and DWI sequences, without abnormal enhancement (see Fig. 7). EEG revealed inscription of triphasic complexes with a periodic pattern, especially in the left central and temporal areas. Investigations ruled out neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis and prion disease. A spinal tap revealed a high titer of measles antibodies in the CSF. Follow-up brain MRI revealed marked and diffuse supratentorial glial atrophy with prominent ex vacuo enlargement of the ventricular system and periventricular spaces. (see Fig. 8). The analysis of visual evoked potentials (VEPs) revealed severe impairments in both latency and amplitude in the visual conduction pathway. An intrathecal delivery system of interferon alpha and baclofen was then placed, which, in combination with drug therapy, allowed dystonic symptoms to be controlled. At the last follow-up, the patient exhibited effective control of seizures and dystonia. The neurological objective examination indicated spontaneous eye opening, responsiveness to the surrounding environment, and voluntary movements in response to painful stimuli. Unfortunately, the patient died approximately two years after the onset of symptoms.

Fig. 7.

Follow-up Brain MRI performed in patient 4: The exam revealed multiple areas with altered signals in the bilateral thalamic, left frontal, parietal and bilateral temporal-occipital cortical areas

Fig. 8.

Brain MRI (last performed in patient 4): The exam revealed diffuse supratentorial glial atrophy involution

Discussion and conclusions

The global measles vaccination coverage has stagnated in recent years, partly due to disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Currently, the coverage rate for the first dose of the vaccine is 83%, while for the second dose, it is 74%. These levels are below the 95% threshold required to prevent epidemic outbreaks, contributing to a significant increase in measles cases worldwide. In 2023, as many as 57 countries reported large or disruptive measles outbreaks, nearly a 60% increase compared to the 36 countries affected in the previous year. Nearly half of these outbreaks occurred in the African region. This surge in cases is attributed to gaps in vaccination coverage, exacerbated by the interruptions in immunization programs during the pandemic [47, 48]. Regarding SSPE, its incidence is closely linked to measles infection rates. Although specific data on SSPE resurgence are not always available, an increase in SSPE cases is expected over the next 5–10 years, in line with the recent rise in measles cases. This underscores the critical importance of maintaining and improving vaccination coverage to prevent both measles and its severe complications [48, 49].

Without a contributory medical history or previous measles infection, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is not immediately suspected. The first case described could suggest leukodystrophy or a metabolic/mitochondrial disease. However, as the clinical course unfolded, typical SSPE symptoms emerged: gait disturbance with frequent falls indicative of periodic myoclonus, followed by psychomotor regression, cognitive and motor decline, language regression, comprehension deficits, psychiatric symptoms, seizures, and visual disturbances. The confounding factors were the young age and the initial absence of a reported measles infection. The later discovery of a lack of vaccination coverage and a prior measles infection would account for the early onset of symptoms. The other three clinical cases have a typical clinical presentation, age of onset, and progression with a straightforward medical history. In the second and third cases, the initial seizures were followed by rapid psychomotor regression. The fourth patient experienced progressive symptoms leading to a vegetative state; the progression and outcome were negative despite initial treatment with interferon alpha. In this case, the previous clinical history was not available due to the inability to reconstruct it; however, the typical clinical presentation, the presence of anti-measles antibodies in the CSF, and the characteristic EEG and brain MRI findings supported the diagnosis. The common element in all four cases was behavioural regression, which is even more suggestive of progressive motor decline and seizures. Essential diagnostic tools include brain MRI, electroencephalogram, and CSF analysis, which were key in our first and fourth clinical cases. While there is no definitive treatment for SSPE, we observed survival benefits and clinical stabilization using interferon alpha infusion in three cases. Our hospital employs a rechargeable pump connected to a catheter in the intraventricular/intrathecal space for continuous drug release, enhancing therapeutic effects with reduced toxicity. The surgeries were uneventful in all patients except for the last patient, who was complicated by a subcutaneous fluid collection with a fistula and suspected infection of the abdominal surgical wound that required surgical revision and prophylactic antibiotic therapy.

All patients underwent follow-up at our center (except for patient 4): approximately 2½ years after diagnosis for the first case, 7 years after diagnosis for the second case, 10 years after diagnosis for the third case, and 2 years after diagnosis for the fourth case. Given the average mortality rate of approximately 1 to 3 years from clinical onset, these treatments and follow-up data appear favorable in terms of prognosis within the limits of this small case series.

The main clinical characteristics of our patients are summarized below (see Table 4):

Table 4.

Main clinical features of the reported series of patients: A small summary of the main clinical features such as onset and progression, anamnestic history, EEG, presence of measles antibodies and radiological evidence

| Onset age | Clinical history | Vaccination for measles | Previous measles infection | Presence of measles antibody in serum and CSF | EEG | Brain MRI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 5 y.o |

-Gait disturbance with tendency to stumble -dysarthia -Cognitive and motor regression with seizures |

Unpractised | Reported in the first year of life | Detected | Deconstruction of the electrical background activity with subcontinuous focal epileptiform anomalies, structured in periodic complexes of spike and wave 2–4 Hz. |

Hyperintensity in T2 FLAIR in paratrigonal area and corpus callosum, caudate, putamen, thalamus, midbrain Progressive cortical atrophy |

| Case 2 | 15 y.o |

-Generalized tonic-clonic seizures -Psychomotor regression |

Practised | Reported between 3 and 5 y.o | Detected | Slow periodic complexes in the context of a poorly organized background activity | Not available |

| Case 3 | 10 y.o |

-Drug-resistant epilepsy -Cognitive regression and motor decline with visual hallucinations |

Not known | Not known | Detected | Periodic complexes of generalized burst epileptic abnormalities | Hyperintensity in T2 FLAIR in paratrigonal and periventricular areas |

| Case 4 | 11 y.o |

-Seizures in sleep and then atonic seizures -Visual deficit up to cortical blindness -Visual hallucinations -Motor stereotypies -Cognitive deterioration -Extrapyramidal and cerebellar signs |

Not known | Not known | Detected | Triphasic complexes with periodic pattern |

-Altered signal at bilateral thalamic, left frontal-parietal and bilateral temporal-occipital cortical sites -marked and diffuse supratentorial glial-atrophic involution with marked ex-vacuo enlargement of the ventricular system and peri-encephalic spaces |

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis is a rare and fatal disease characterized by progressive neurological deterioration. Diagnosing SSPE is challenging due to its multifaceted clinical presentation. Since vaccines were introduced, disease incidence has gradually declined, though rates vary by region and vaccine coverage. However, false beliefs and nonadherence to vaccination campaigns have recently increased disease cases. The only effective prevention remains vaccination. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted global vaccination efforts, leading to a general decline in measles vaccination coverage [49]. As vaccine adherence decreases, there is a higher incidence of adverse outcomes and complications of preventable diseases [50–52]. Therefore, an increase in SSPE cases is expected over the next 5 to 10 years. Six World Health Organization regions, including Europe, have set measles elimination goals [49]. In this evolving scenario, as measles becomes rarer, it is essential to promptly recognize psychomotor regression as a key symptom, even without a clear medical history, and to promote routine vaccination in young children. At present, the only effective strategy to combat this devastating disease remains vaccination—a safe, effective, and cost-efficient intervention.

Acknowledgements

In addition to the above-mentioned contribution of the reported authors, Drs. Serena Troisi, Celeste Tucci and Ersilia Savastano also contributed to the collection of clinical data and the follow-up of the patients.

Author contributions

We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors and that there are no other people who satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed. We further confirm that the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been approved by all of us. This work was supported by Dr. FM, Dr. SG, Dr. PB and Dr. EdU from the Istituto Superiore di Sanità in Rome for the epidemiological and infectivological description, in particular the laboratory investigations; by Dr. FT and Dr. CR from the Paediatric Neurosurgery Unit for the detailed description of the new neurosurgical approaches; and finally by the corresponding authors Dr. GE and Dr. AV, Dr. GB, Dr. SG and Dr. M DL from the Paediatric Neurology Unit for the description of the case reports and for following up the patients during the years.

Funding

Fondazione Santobono Pausilipon.

Data availability

All clinical data and materials are available in Paediatric Neurology and Paediatric Neurosurgery Units of Santobono-Pausilipon Children’s Hospital in Naples.

Declarations

Ethical approval

No experimental procedure was performed, but only the investigations required by clinical practice. Therefore, it was not needed to submit the case to the approval of the Ethics Committee. Clinical Investigations were conducted according to the principles expressed in Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was acquired from parents of the patients both for the diagnostic procedures required for diagnosis and for the use of data for scientific purposes in respect of privacy.

Author information

We understand that the Corresponding Author is the sole contact for the Editorial process (including Editorial Manager and direct communications with the office). She is responsible for communicating with the other authors about progress, submissions of revisions and final approval of proofs. We confirm that we have provided a current, correct email address which is accessible by the Corresponding Author.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Gabriella Errichiello and Francesco Tengattini contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Garg RK. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. J Neurol. 2008;255(12):1861–71. 10.1007/s00415-008-0032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liko J, Guzman-Cottrill JA, Cieslak PR. Notes from the field: subacute sclerosing panencephalitis Death - Oregon, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(1):10–1. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6501a3. Published 2016 Jan 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jafri SK, Kumar R, Ibrahim SH. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis - current perspectives. Pediatr Health Med Ther. 2018;9:67–71. 10.2147/PHMT.S126293. Published 2018 Jun 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papetti L, Amodeo ME, Sabatini L, et al. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis in children: the archetype of Non-Vaccination. Viruses. 2022;14(4):733. 10.3390/v14040733. Published 2022 Mar 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bester JC. Measles and measles vaccination: A review. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(12):1209–15. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell H, Andrews N, Brown KE, Miller E. Review of the effect of measles vaccination on the epidemiology of SSPE. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(6):1334–48. 10.1093/ije/dym207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lebon P, Gelot A, Zhang SY, Casanova JL, Hauw JJ. Measles Sclerosing Subacute PanEncephalitis (SSPE), an intriguing and ever-present disease: Data, assumptions and new perspectives [published correction appears in Rev Neurol (Paris). 2022;178(6):634. 10.1016/j.neurol.2022.04.002]. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2021;177(9):1059–1068. 10.1016/j.neurol.2021.02.387. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bellini WJ, Rota JS, Lowe LE, et al. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: more cases of this fatal disease are prevented by measles immunization than was previously recognized. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(10):1686–93. 10.1086/497169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schönberger K, Ludwig MS, Wildner M, Weissbrich B. Epidemiology of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) in Germany from 2003 to 2009: a risk estimation. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68909. Published 2013 Jul 9. 10.1371/journal.pone.0068909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Wendorf KA, Winter K, Zipprich J, et al. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: the devastating measles complication that might be more common than previously estimated. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(2):226–32. 10.1093/cid/cix302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onal AE, Gurses C, Direskeneli GS, et al. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis surveillance study in Istanbul. Brain Dev. 2006;28(3):183–9. 10.1016/j.braindev.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi S, Metcalf CJ, Ferrari MJ, et al. Reduced vaccination and the risk of measles and other childhood infections post-Ebola. Science. 2015;347(6227):1240–2. 10.1126/science.aaa3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kija E, Ndondo A, Spittal G, Hardie DR, Eley B, Wilmshurst JM. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis in South African children following the measles outbreak between 2009 and 2011. S Afr Med J. 2015;105(9):713–8. 10.7196/SAMJnew.7788. Published 2015 Sep 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McQuaid S, Cosby SL, Koffi K, Honde M, Kirk J, Lucas SB. Distribution of measles virus in the central nervous system of HIV-seropositive children. Acta Neuropathol. 1998;96(6):637–42. 10.1007/s004010050945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hübschen JM, Gouandjika-Vasilache I, Dina J, Measles. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):678–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sato Y, Watanabe S, Fukuda Y, Hashiguchi T, Yanagi Y, Ohno S. Cell-to-cell measles virus spread between human neurons is dependent on hemagglutinin and hyperfusogenic fusion protein. J Virol. 2018;92(6):e02166-17. Published 2018 Feb 26. 10.1128/JVI.02166-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Watanabe S, Ohno S, Shirogane Y, Suzuki SO, Koga R, Yanagi Y. Measles virus mutants possessing the fusion protein with enhanced fusion activity spread effectively in neuronal cells, but not in other cells, without causing strong cytopathology. J Virol. 2015;89(5):2710–7. 10.1128/JVI.03346-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutierrez J, Issacson RS, Koppel BS. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: an update. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(10):901–7. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue T, Kira R, Nakao F, et al. Contribution of the Interleukin 4 gene to susceptibility to subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(5):822–7. 10.1001/archneur.59.5.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Budka H, Lassmann H, Popow-Kraupp T. Measles virus antigen in panencephalitis. An Immunomorphological study stressing dendritic involvement in SSPE. Acta Neuropathol. 1982;56(1):52–62. 10.1007/BF00691182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen IV, McQuaid S, McMahon J, Kirk J, McConnell R. The significance of measles virus antigen and genome distribution in the CNS in SSPE for mechanisms of viral spread and demyelination. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55(4):471–80. 10.1097/00005072-199604000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plumb J, Duprex WP, Cameron CH, Richter-Landsberg C, Talbot P, McQuaid S. Infection of human oligodendroglioma cells by a Recombinant measles virus expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein. J Neurovirol. 2002;8(1):24–34. 10.1080/135502802317247785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erturk O, Karslıgil B, Cokar O, et al. Challenges in diagnosing SSPE. Childs Nerv Syst. 2011;27(12):2041–4. 10.1007/s00381-011-1603-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mekki M, Eley B, Hardie D, Wilmshurst JM. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: clinical phenotype, epidemiology, and preventive interventions. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61(10):1139–44. 10.1111/dmcn.14166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jabbour JT, Garcia JH, Lemmi H, Ragland J, Duenas DA, Sever JL. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. A multidisciplinary study of eight cases. JAMA. 1969;207(12):2248–54. 10.1001/jama.207.12.2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orey FAH, Sahal AO, Garba B. Fatal subacute sclerosing panencephalitis in an 8-year-old male: a case report. Pan Afr Med J. 2023;45:37. 10.11604/pamj.2023.45.37.38601. Published 2023 May 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Praticò AD, Saporito M, Iacono O, Castellano-Chiodo D, Pavone P. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: a case report. Minerva Pediatr. 2011;63(1):73–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guler S, Kucukkoc M, Iscan A. Prognosis and demographic characteristics of SSPE patients in istanbul, Turkey. Brain Dev. 2015;37(6):612–7. 10.1016/j.braindev.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dyken PR. Neuroprogressive disease of post-infectious origin: a review of a resurging subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2001;7(3):217–25. 10.1002/mrdd.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kissani N, Ouazzani R, Belaidi H, Ouahabi H, Chkili T. Crises épileptiques et épilepsie Dans Le cadre d’une panencéphalite sclérosante Subaiguë (à Propos de 30 cas) [Epileptic seizures and epilepsy in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (report of 30 cases]. Neurophysiol Clin. 2001;31(6):398–405. 10.1016/s0987-7053(01)00278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berker N, Batman C, Guven A, Ozalp S, Aslan O, Zilelioglu O. Optic atrophy and macular degeneration as initial presentations of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(5):879–81. 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.05.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garg RK, Pandey S, Nigam H, et al. Case report: an unusual case of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis with distinctive clinical and neuroimaging features. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2023;108(5):1025–7. 10.4269/ajtmh.22-0731. Published 2023 Mar 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kayal M, Varghese ST, Balhara YP. Psychiatric manifestation of SSPE. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;18(4):560. 10.1176/jnp.2006.18.4.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobi C, Lange P, Reiber H. Quantitation of intrathecal antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, herpes simplex encephalitis and multiple sclerosis: discrimination between microorganism-driven and polyspecific immune response. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;187(1–2):139–46. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Häusler M, Aksoy A, Alber M, et al. A multinational survey on actual diagnostics and treatment of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Neuropediatrics. 2015;46(6):377–84. 10.1055/s-0035-1564618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dyken PR. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Current status. Neurol Clin. 1985;3(1):179–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Magurano F, Baggieri M, Marchi A, Rezza G, Nicoletti L, Eleonora B, Concetta F, Stefano F, Maedeh K, Paola B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection: the environmental endurance of the virus can be influenced by the increase of temperature. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:e2895–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magurano F, Baggieri M, Fortuna C, et al. Measles elimination in italy: data from laboratory activity, 2011–2013. J Clin Virol. 2015;64:34–9. 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Demir N, Cokar O, Bolukbasi F, et al. A close look at EEG in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;30(4):348–56. 10.1097/WNP.0b013e31829ddcb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gürses C, Oztürk A, Baykan B, et al. Correlation between clinical stages and EEG findings of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Clin Electroencephalogr. 2000;31(4):201–6. 10.1177/155005940003100409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cece H, Tokay L, Yildiz S, Karakas O, Karakas E, Iscan A. Epidemiological findings and clinical and magnetic resonance presentations in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. J Int Med Res. 2011;39(2):594–602. 10.1177/147323001103900228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yilmaz K, Yilmaz M, Mete A, Celen Z. A correlative study of FDG PET, MRI/CT, electroencephalography, and clinical features in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Clin Nucl Med. 2010;35(9):675–81. 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181e9fa5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kannan L, Garg SK, Arya R, Sankar MJ, Anand V. Treatments for subacute sclerosing panencephalitis [retraction of: 10.1002/14651858.CD010867]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;2021(7):CD010867. Published 2021 Jul 28. 10.1002/14651858.CD010867.pub2

- 44.Hashimoto K, Hosoya M. Advances in antiviral therapy for subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Molecules. 2021;26(2):427. 10.3390/molecules26020427. Published 2021 Jan 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Norris FH, Panitch HS, Denys EH, Downes K, Cantell K, Smith RA. The treatment of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis with interferon: a case report. J Neurol. 1986;233(2):102–7. 10.1007/BF00313855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kwak M, Yeh HR, Yum MS, Kim HJ, You SJ, Ko TS. A long-term subacute sclerosing panencephalitis survivor treated with intraventricular interferon-alpha for 13 years. Korean J Pediatr. 2019;62(3):108–12. 10.3345/kjp.2018.06730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rocke Z, Belyayeva M. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. StatPearls. Volume 19. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Minta AA, Ferrari M, Antoni S, et al. Progress toward measles Elimination - Worldwide, 2000–2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(46):1262–8. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7246a3. Published 2023 Nov 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raghunathan PL, Orenstein W. Investing in global measles and Rubella elimination is needed to avert deaths and advance health equity. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10(10):e1363–4. 10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00388-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giordano S, Serra G, Dones P, et al. Acute pancreatitis in children and rotavirus infection. Description of a case and minireview. New Microbiol. 2013;36(1):97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Costantino C, Conforto A, Bonaccorso N, et al. Safety of rotavirus vaccination in preterm infants admitted in neonatal intensive care units in sicily, italy: A multicenter observational study. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11(4):718. 10.3390/vaccines11040718. Published 2023 Mar 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Serra G, Lo Scalzo L, Giordano M, et al. Group B streptococcus colonization in pregnancy and neonatal outcomes: a three-year monocentric retrospective study during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Ital J Pediatr. 2024;50(1):175. 10.1186/s13052-024-01738-2. Published 2024 Sep 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All clinical data and materials are available in Paediatric Neurology and Paediatric Neurosurgery Units of Santobono-Pausilipon Children’s Hospital in Naples.