Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study is to determine whether “digital flashcard” graphics on a provider's smartphone are helpful in educating adolescents about reproductive health.

Methods

A randomized study compared the understanding of reproductive health topics among adolescents using digital flashcards during a clinical visit vs counseling as usual (control).

Results

There were 197 subjects (99 flashcards, 98 control) with mean age of 14.7 years. Among subjects in the flashcard group, new patients used more flashcards than return patients (3.48 vs 2.40, p = 0.001). The most frequently used flashcards were 7-day placebo birth control pills, the intrauterine device, internal anatomy and 84-day birth control pills. Among the flashcard group 96.9 % reported they “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that flashcards were helpful in understanding the topics discussed, and 98 % would recommend using them in the future. All subjects experienced an increase in understanding of the topics discussed during clinic, and there was no difference between the flashcard group and control.

Conclusion

Subjects using the digital flashcards during their clinical encounter reported high acceptability.

Innovation

Digital flashcards are accessible via smart phone use and can be easily distributed among providers to assist in reproductive health counseling in adolescents.

1. Introduction

Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the ability to understand and use information to inform health-related decisions for themselves. [1] While many studies explore the relationship between health literacy and health outcomes, less attention has been focused specifically on the effects of health literacy on reproductive health. Reproductive health literacy among adolescents is essential to improve menstrual health and also to avoid unwanted pregnancies or sexually transmitted diseases. [2] Many topics addressed during a reproductive health visit, such as contraception, the menstrual cycle, puberty or anatomy may be difficult for younger patients to fully understand [3,4]. Several studies have included adolescents in the evaluation of health literacy involving reproductive health topics. Low health literacy has been associated with decreased knowledge and understanding about the mechanism of oral contraception, decreased knowledge about sexually transmitted infections and difficulty with contraception use. [[5], [6], [7]] Adolescents with lower health literacy have also been shown to have greater difficulty understanding labeling and reproductive health educational brochures. [8]

In a systematic review of health literacy in reproductive health, among 34 articles described, only nine included adolescent subjects and five involved any intervention to improve health literacy. Interventions included toolkits, brochures, infographics and medication labeling on various reproductive health topics. [2]

Providers commonly rely on text (handouts, brochures, or posters) to assist in patient counseling, however, these health information tools may require higher reading skills than possessed by the average adolescent. [9] According to the National Institutes of Health, readability of patient education should be no greater than a sixth grade reading level, but studies assessing patient literature demonstrate that most materials are written at higher reading levels. [10,11] The inclusion of graphics has been shown to have a positive overall effect in reading comprehension regardless of reading level. [12] Pelvic models, contraceptive models and other visual aids can also be used to improve contraceptive knowledge, prevent sexually transmitted disease transmission, and help patients understand the provider thought process. [[13], [14], [15]] A concern with all of these educational tools is that they are not always readily available in every clinical setting.

Smartphone use is ubiquitous, with studies reporting that over 90 % of physicians use a smart phone in clinical practice. [16] Multiple smartphone applications exist to assist providers in contraception education, but a recent analysis found that only a small number of these apps are targeted toward provider use of these services and are limited in quality and comprehensiveness. [17] In contrast, simple graphics or pictures are easily accessible on smartphones without relying on internet use or applications. The use of simple graphic designs have been implemented in many medical settings to improve patient understanding of various disease processes and improve outcomes. [18,19] To our knowledge, there are no published studies utilizing simple digital graphics to counsel adolescents on reproductive health topics.

Given that smart phones have the capability to store and access images easily and disperse them to other providers, this study aimed to develop simple educational graphics focused on reproductive health that could be stored and accessed on a clinician's phone. These images designated “digital flashcards” can be scrolled through, like a photo album, and therefore can easily be incorporated into patient visits to assist with counseling. The purpose of this study was to determine whether these digital flashcards were helpful in the education and understanding of reproductive health topics among adolescents.

2. Materials and methods

This was a prospective study involving adolescent subjects aged 11–17 presenting to the pediatric and adolescent gynecology (PAG) clinic at an academic institution, which is staffed by a single PAG physician. Subjects were included if they were accompanied by a guardian and were able to give assent for participation. Consent by one parent was required by the Institutional Review Board. Assenting subjects were then randomized using opaque envelopes in a 1:1 ratio into two groups: Flashcards and No Flashcards (control). The “No Flashcards” group served as the control group and received counseling from the provider in the typical fashion. Subjects assigned to the “Flashcard” group were counseled with pictorial visual aids, referred hereto forth as digital flashcards on the provider's cellphone. Specific digital flashcards were used that were only relevant to topics addressed during the clinical encounter (ie: contraception, heavy bleeding, anatomical concerns).

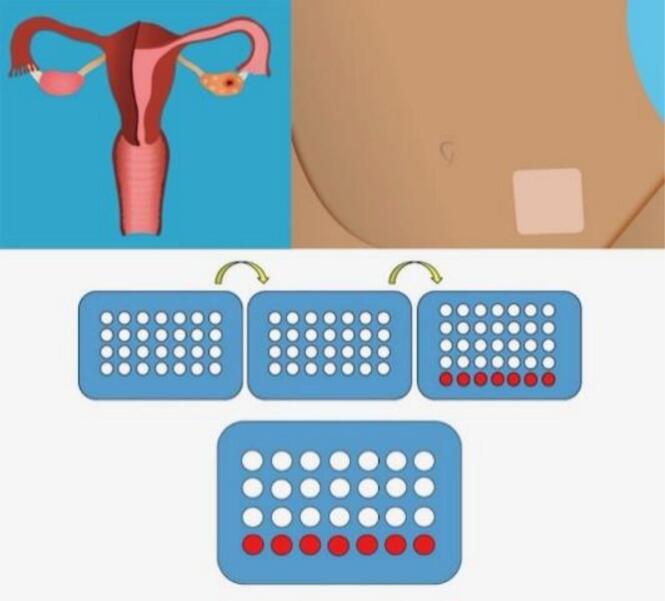

The digital flashcards were designed by a PAG physician in collaboration with a medical graphic design artist at the academic institution. Digital flashcards included graphics of all reversible contraceptive methods, anatomy (internal and external reproductive structures), a menstrual calendar, contraceptive pill stickers, and the phases of the menstrual cycle (Fig. 1). Contraceptive pill graphics included all types of pill packaging including 7-day placebo, 4-day placebo, no placebo, rectangular and circular packaging, and extended cycle (84-day) pills. Digital flashcard images were modeled after actual birth control methods. The PAG physician met with the graphic designer with samples of birth control pills, patches, rings, and depomedroxyprogesterone injection. Pelvic models and tactile models were also provided of progestin containing and copper intrauterine devices, and the subdermal implant. The graphic designer used these materials to develop two-dimensional simplified graphics. These were reviewed and accepted by the PAG physician along with the medical students and resident physician involved in the study. For birth control pills, once a standard format for the 7-day placebo pill pack was developed, this graphic was used as the basis for developing the 4-day placebo, no placebo and extended cycle (84 day) pill pack graphics.

Fig. 1.

Selected digital flashcards used during clinic encounters a)internal anatomy b)contraceptive patch c) 84 day pills d)7 day placebo pill pack. All digital flashcards available for download at: https://www.marshallhealth.org/for-health-professionals/digital-flashcards-for-medical-providers/

All digital flashcards were made available to view and download at: https://www.marshallhealth.org/for-health-professionals/digital-flashcards-for-medical-providers/. Digital flashcards were uploaded to the provider's cellphone as individual photo images and saved in a file under the photo application.

During the clinic visits all subjects received routine counseling, but with the flashcard group, the provider used at least one digital flashcard to accompany the counseling. At the conclusion of each visit an anonymous survey was completed by the patient through RedCap using a provided tablet. The physician also completed a short survey for data collection after the clinical encounter.

The subject survey asked what topics were discussed during the clinical visit. Subjects were also asked two Likert scale questions regarding how well they understood the topics covered before and after the visit: “How well did you understand the topics discussed BEFORE the clinic visit?”(Prior Understanding) and “How well did you understand the topics discussed AFTER the clinic visit?” (Post Understanding). The flashcard group was also asked to evaluate if the digital flashcards helped them understand the explanation by the provider. The control group was asked if they would have learned more if a visual aid or picture was used. Responses to these questions were by Likert scale.

The provider post visit survey recorded patient age, age at menarche, previous birth control use, new or return patient visit, and educational grade of the patient. The survey also had the provider select the digital images that were used during the encounter from a list of all the available options. Tabulations and descriptive statistics were used to quantify topics covered and which digital flashcards were used. Responses to questions regarding understanding of clinical topics before and after the visit were compared between groups. Power analysis calculated 98 individuals in each group to achieve 80 % power. This power was calculated assuming medium effect size of 0.25 with medium correlation among repeated measures (0.5) and equal sample allocation. We implemented two sample t-test to compare the outcomes between new and returned patients, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests to compare the 5 scale Likert type outcomes relevant to understanding of the topics between flashcard and control groups, and Wilcoxon signed rank test to compare the prior and post understandings. Subjects were provided a sports water bottle with the institutional logo as an incentive for participation.

3. Results

A total of 197 subjects (99 flashcards, 98 control) were included in the study with a mean age of 14.7 (SD 1.67). Descriptive data is included in Table 1. Among all subjects, 118/197 (59.9 %) had history of previous contraception use, 74/197 (37.6 %) were new patients, and 123/197 (62.4 %) were established patients in the PAG practice. The primary reasons for clinic visits included menstrual improvement (79.7 %), contraception (27.4 %), and “other” gynecologic concern (22.8 %). The most commonly discussed topics reported by all subjects during the clinic visit (not mutually exclusive) included birth control pills (n = 166), intrauterine devices (n = 91), irregular periods (n = 140), heavy menstrual bleeding (n = 130), dysmenorrhea (n = 132) and internal reproductive organs (n = 89). Less commonly discussed topics included puberty (n = 39), external anatomy (n = 22) and the depomedroxyprogesterone actetate injection (n = 43).

Table 1.

Descriptive data of 197 subjects included in the study.

| Variables | N = 197 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (range, mean in yrs) | 11–17 | |

| 14.7 (SD 1.67) | ||

| Age Menarche (range, mean in yrs) | 9–15 11.3 (SD 1.3) |

|

| Previous Contraception | ||

| Yes | 118 | 59.9 |

| No | 79 | 40.1 |

| New Patient | ||

| Yes | 74 | 37.6 |

| No | 123 | 62.4 |

| Reason for Clinic Visit (not mutually exclusive) | ||

| Birth Control | 54 | 27.4 |

| Menstrual Improvement | 157 | 79.7 |

| Other* | 45 | 22.8 |

| Flashcards | ||

| Yes | 99 | 50.3 |

| No | 98 | 49.7 |

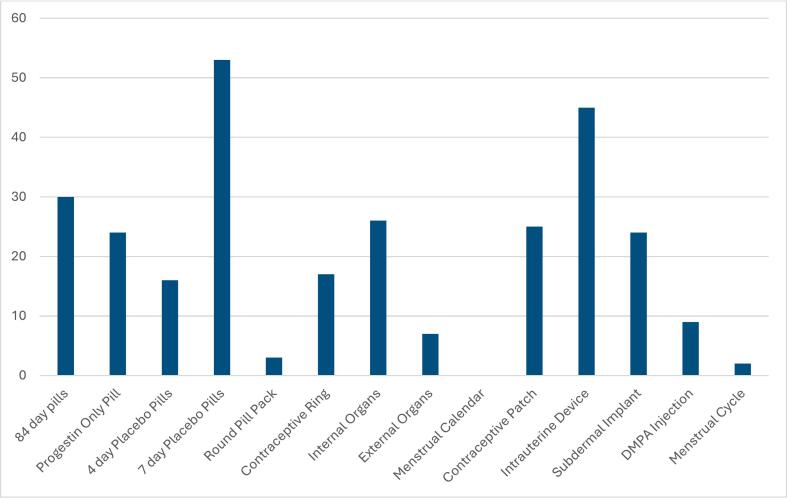

In the flashcard group, the mean number of flashcards used during the encounter was 2.8 (SD 1.69) with a range of 1–7. The most frequently used flashcards among the 99 subjects in this group were the 7-day placebo birth control pills (n = 53), the intrauterine device (n = 45), the 84-day birth control pills (n = 30) and internal anatomy (n = 26) (Fig. 2). The mean number of flashcards used with new patients was higher than with return patients (3.48 SD 1.82 vs 2.40 SD 1.32, p = 0.001). There was no significant difference in mean number of flashcards used among subjects with and without prior contraceptive use (2.77 SD 1.7 vs 3.1 SD 1.6, p = 0.83).

Fig. 2.

Frequency of flashcards used during clinical encounters among 99 subjects in Flashcard group. (DMPA = depomedroxyprogesterone).

Among the flashcard group, 96.9 % of subjects reported they “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that flashcards were helpful in understanding the topics discussed. Additionally, 98 % of the flashcard group reported they would recommend using them in the future. Among the control group, only 22.5 % of subjects reported they would have learned more if flashcards had been used and 61.2 % had a neutral response.

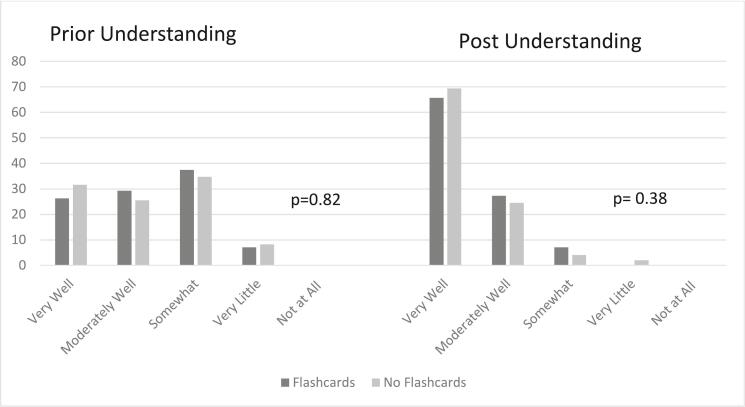

In both groups, the subjects reported an increase understanding of the topics discussed during the clinic visit. The response to the following questions was compared within each group: “How well did you understand the topics discussed BEFORE the clinic visit?”(Prior Understanding) and “How well did you understand the topics discussed AFTER the clinic visit?” (Post Understanding). The “very well” response in both flashcard and control groups increased from prior understanding to post understanding (26.3 % vs 65.7 % in the flashcard group, p ≤0.001, and 31.6 % to 69.4 % in controls, p ≤0.001). However, when comparing responses among both groups there was no overall difference in both prior and post understanding of topics between flashcard and control groups (Fig. 3) The proportional increase in those reporting “very well” was similar among the flashcard and control groups.

Fig. 3.

Responses to question “How well did you understand the topics discussed BEFORE the clinic visit?”(Prior Understanding) and “How well did you understand the topics discussed AFTER the clinic visit?” (Post Understanding).

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

This study evaluated an intervention among adolescent females to improve reproductive health knowledge and understanding. Adolescent subjects exposed to the intervention of digital flashcards during their clinical encounter felt that they were overall helpful in promoting the understanding of the topics discussed during their visit. The most popular flashcards used were the 7-day placebo pills, the IUD, internal anatomy and 84-day pills (extended cycle). These flashcards are representative of common medications used within a pediatric and adolescent gynecology practice, and topics that may be conceptually difficult for younger patients to comprehend. Unsurprisingly, new patients used more flashcards during the clinical encounter than return patients. Compared to the control group, however, there was not an appreciable difference in reported understanding of reproductive health topics following the intervention.

While other studies to date give insight into the relationship between health literacy and reproductive knowledge and related behaviors, there are fewer studies that specifically evaluate health literacy-informed interventions. Findings from a systematic review suggest that health literacy is related to reproductive health knowledge across a number of topics, including contraception, fertility and STI prevention. While there were few interventional studies in this review, results indicated that use of tailored educational materials can increase understanding of reproductive health topics for patients with both limited and adequate health literacy. [2] Another systematic review evaluated thirty one studies that utilized various techniques and tools shown to improve contraception knowledge specifically. [20] These interventions included leaflets, pamphlets, written materials, charts, videos, audio and interactive tools; emphasizing that a range of interventions can increase patient knowledge. There is no study, to our knowledge, that has assessed simple digital graphics for reproductive health among adolescents.

Multiple health organizations acknowledge the need for physicians to consider patient's health literacy skills for clinical care. The Center for Disease Control advocates for a patient-centered approach to counseling and educating individuals about reproductive health using tools that focus on health literacy. [21] The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advocates that provision of reproductive health services is enhanced using educational tools, and that care should be individualized to patients' developmental age and health literacy. [3] ACOG further challenges providers to develop tools and methods to disseminate health information among patients with limited health literacy, taking into account patients' unique circumstances and abilities for comprehending information. [3] This study accomplishes this task by specifically addressing a younger adolescent population and taking into account their developmental age when designing the flashcard intervention.

Strengths of this study include its randomized design and large sample size. It is also reproducible across specialties, and the flashcards are easily accessible and sharable among providers. This could be helpful for other providers involved in reproductive health counseling such as pediatricians and other primary care clinicians. As providers rely on use of their smart phone for other aspects of clinical care, having an educational tool with them that is not dependent on the clinical setting may prompt more use. Hands-on pelvic models or models of birth control methods are available for providers for purchase from several websites. [22] There is a cost to these models, and they are not easily shareable among providers and clinic sites.

There are several weaknesses to the study design. Subjects were asked about their before and after health knowledge at the end of the clinic visit and by Likert scale only. This method of retrospective post-then-pre questioning can control for response shift bias that occurs when subjects use a different framework for answering questions before an intervention, but may not be a reliable measure of pre-intervention knowledge. [23] Both groups showed a positive change in Likert scale response regarding understanding of the topics discussed, but this may be purely reflective of the provider's counseling alone. In addition, 61.2 % of the control group responded neutrally about whether a visual aid would have been helpful. Multiple reproductive health topics were included, and it was not known what topics would be covered in advance prior to the clinic visit, which precluded assessing an objective knowledge score on a specified topic. While knowledge was not objectively assessed in this study, the subjects overwhelmingly responded positively to the use of digital flashcards during their clinic visit. As graphics can improve patient comprehension of written material, future steps include using these digital flashcards to measure objective knowledge scores among subjects seeking reproductive health services.

These future studies could involve a specific topic (ie: birth control use), to allow for quantifiable results or knowledge scores.

An additional weakness was that this study was done by a single provider, as the institution only has one PAG physician. While this is a strength in that patient counseling was consistent with minimal variation, no data could be obtained from the provider's perspective as it would have been affected by significant bias. Future study would involve evaluation of the digital flashcards by other adolescent providers to assess usability within various clinical settings.

4.2. Innovation

This study demonstrates an innovative collaboration between a physician and graphic designer to improve reproductive health literacy among young adolescent females. Medical providers can witness firsthand where better educational tools are needed for patient counseling. In this study, the complexities of reproductive health and contraception were addressed by developing simple graphical pictures so that young adolescent patients could gain a better understanding of their body and medical options.

The digital flashcard design is also innovative in its accessibility and potential for dissemination and use among multiple clinical settings. These digital flashcards stored as individual images in a provider's smartphone are easily accessed during clinical encounters and can be dispersed to multiple providers involved in reproductive health counseling. This has already occurred among multiple providers, both institutionally and nationally, as these digital images are available for download (Fig. 1), and can be texted and emailed. These images are not only helpful, but extremely easy to disseminate to providers that may need them at no cost. As smart phone use is ubiquitous, providers would not need to rely on other reproductive health models, posters or pamphlets that may not be readily available in each clinical setting. In addition, these graphics do not contain text, therefore do not require translation in areas where patients speak different languages. Internet use is not required as these images are saved as a photo file, which is quicker than looking up images online that may not be as medically accurate. Potential clinical settings that may benefit would be mobile clinics, health departments, family planning clinics, shelters or school-based health clinics.

4.3. Conclusion

Of the adolescents using the digital flashcards, the majority responded that they would recommend using them in the future and agreed that they were helpful in understanding various reproductive health topics. These readily accessible tools specific to reproductive health, menstrual health and contraception, can engage adolescents during clinical discussions. This not only contributes to their understanding of these conceptually difficult topics, but could also improve their confidence in future decision making. Medical providers should be encouraged to collaborate with graphic designers to improve educational health tools for patient counseling.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Meghan A. Anderson: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Rachel Price: Project administration, Methodology, Data curation. Tori P. Miller: Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Rajan Lamichhane: Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Jennie L. Yoost: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Disclosure

The authors have no financial disclosures or competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Translational Sciences Core of COBRE/ACCORD, Clinical, and Translational Sciences Department, Joan C Edwards School of Medicine, Marshall University for analytics support.

References

- 1.Nutbeam D., Lloyd J.E. Understanding and responding to health literacy as a social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2021;42:159–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilfoyle K.A., et al. Health literacy and women’s reproductive health: a systematic review. J. Women’s Health (Larchmt) 2016;25(12):1237–1255. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.5810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Committee Opinion No 676: health literacy to promote quality of care. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016;128(4):e183–e186. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Committee Opinion No 710: counseling adolescents about contraception. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;130(2):e74–e80. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis T.C., et al. Patient understanding and use of oral contraceptive pills in a southern public health family planning clinic. South. Med. J. 2006;99(7):713–718. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000223734.77882.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutherford J., et al. Low literacy: a hidden problem in family planning clinics. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2006;32(4):235–240. doi: 10.1783/147118906778586778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yee L.M., Simon M.A. The role of health literacy and numeracy in contraceptive decision-making for urban Chicago women. J. Community Health. 2014;39(2):394–399. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9777-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Needham H.E., et al. Relationship between health literacy, reading comprehension, and risk for sexually transmitted infections in young women. J. Adolesc. Health. 2010;46(5):506–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stossel L.M., et al. Readability of patient education materials available at the point of care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012;27(9):1165–1170. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2046-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rooney M.K., et al. Readability of patient education materials from high-impact medical journals: a 20-year analysis. J Patient Exp. 2021;8 doi: 10.1177/2374373521998847. 2374373521998847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parker R.M., Gazmararian J.A. Health Literacy: essential for health communication. J Health Commun. 2003;8:116–118. doi: 10.1080/713851963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo D., et al. Do you get the picture? A Meta-analysis of the effect of graphics on Reading comprehension. AERA Open. 2020;6(1) 2332858420901696. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson S., et al. Effects of two educational posters on contraceptive knowledge and intentions: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019;133(1):53–62. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Noia J., et al. Evaluation of a brief computer-mediated intervention to reduce HIV risk among early adolescent females. J. Adolesc. Health. 2004;35(1):62–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim N.S., et al. Visual causal models enhance clinical explanations of treatments for generalized anxiety disorder. J. Health Commun. 2013;18 Suppl 1(Suppl. 1):103–117. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.829136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraushaar J., Bohnet-Joschko S. Prevalence and patterns of mobile device usage among physicians in clinical practice: a systematic review. Health Informatics J. 2023;29(2) doi: 10.1177/14604582231169296. 14604582231169296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perry R., Lunde B., Chen K.T. An evaluation of contraception mobile applications for providers of family planning services. Contraception. 2016;93(6):539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeWalt D.A., et al. A heart failure self-management program for patients of all literacy levels: a randomized, controlled trial [ISRCTN11535170] BMC Health Serv. Res. 2006;6:30. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohli E., et al. Promoting community health and understanding of science topics by Reading graphic-style stories aloud together. Health Educ. Behav. 2023;50(5):658–661. doi: 10.1177/10901981231159681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pazol K., et al. Impact of contraceptive education on knowledge and decision making: an updated systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018;55(5):703–715. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gavin L., et al. Providing quality family planning services: recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2014;63(RR-04):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Planned Parenthood. February 17, 2025. plannedparenthood.org/planned-parenthood-southern-new-england/education/teaching-tools#demonstration-tools Available from:

- 23.Nimon K., Allen J. Retrospective pretest: a practical technique for professional development evaluation. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2007;44:27–42. [Google Scholar]