Abstract

Prokaryotic dioxygenase is known to catalyze aromatic compounds into their corresponding cis-dihydrodiols without the formation of an epoxide intermediate. Biphenyl dioxygenase from Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707 showed novel monooxygenase activity by converting 2(R)- and 2(S)-flavanone to their corresponding epoxides (2-(7-oxabicyclo[4.1.0]hepta-2,4-dien-2-yl)-2, 3-dihydro-4H-chromen-4-one), whereby the epoxide bond was formed between C2′ and C3′ on the B ring of the flavanone. The enzyme also converted 6-hydroxyflavanone and 7-hydroxyflavanone, which do not contain a hydroxyl group on the B-ring, to their corresponding epoxides. In a previous report (S.-Y. Kim, J. Jung, Y. Lim, J.-H. Ahn, S.-I. Kim, and H.-G. Hur, Antonie Leeuwenhoek 84:261-268, 2003), however, we found that the same enzyme showed dioxygenase activity toward flavone, resulting in the production of flavone cis-2′,3′-dihydrodiol. Extensive structural identification of the metabolites of flavanone by using high-pressure liquid chromatography, liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry, and nuclear magnetic resonance confirmed the presence of an epoxide functional group on the metabolites. Epoxide formation as the initial activation step of aromatic compounds by oxygenases has been reported to occur only by eukaryotic monooxygenases. To the best of our knowledge, biphenyl dioxygenase from P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707 is the first prokaryotic enzyme detected that can produce an epoxide derivative on the aromatic ring structure of flavanone.

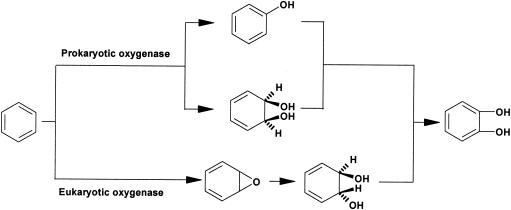

Hydrophobic aromatic hydrocarbons may be metabolized through the initial activation of the aromatic ring by insertion of molecular oxygen using certain oxygenases found in host organisms (4, 8, 31). The consequences of such reactions result in the production of intermediates containing epoxide, phenol, or cis-dihydrodiol functional groups that correspond to the parent aromatic compound from which it was derived (6, 10, 14, 21, 27, 28, 45). Based upon whether a eukaryote or prokaryote is performing the activity (Fig. 1) (7, 8), there are fundamental differences in the initiation reactions for the metabolism of aromatic compounds. Eukaryotes produce aromatic epoxides, followed by the formation of trans-dihydrodiols (35). The key enzyme involved in the reaction has been shown to be cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, which operates over a wide spectrum of substrates (21, 38). Prokaryotes, however, harness different metabolic routes for transforming aromatic compounds, producing either phenols by monooxygenases or cis-dihydrodiols by dioxygenases (4, 14, 33, 41, 42). In addition, prokaryotic dioxygenases have not been shown to catalyze initiation reactions of aromatic ring structures via formation of aromatic epoxide intermediates (44).

FIG. 1.

Pathways for the metabolic initiation of arene ring structures by prokaryotic and eukaryotic oxygenases. (Adapted from reference 44 with the permission of the author and the publisher.)

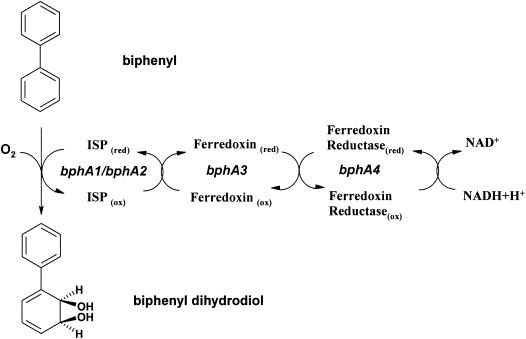

Due to the properties of the prokaryotic oxygenases, which include their substrate diversity and their production of stereo- and regioselective metabolites, there are extensive applications for these enzymes in the fields of environmental pollutant biodegradation and production of value-added novel compounds (4, 10, 16, 42, 43). Among the bacterial dioxygenases, toluene, naphthalene, and biphenyl dioxygenase have been most thoroughly studied in terms of genetic and biochemical characterization as related to aromatic ring activation (14, 18, 20, 40). Bacterial dioxygenase is a three-component enzyme consisting of a terminal dioxygenase and a short electron transport chain (Fig. 2). Terminal dioxygenase, which catalyzes the direct introduction of two oxygen atoms into the biphenyl ring, is composed of an iron sulfur protein forming a Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] cluster and a small subunit. Although the Rieske-type terminal dioxygenases have different substrate specificities, they have identical active centers of the 2His-1-carboxylate triad for substrate oxidation and show a high peptide sequence homology by BLAST peptide sequence matching (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). Generally, the accepted reaction mechanism for the aromatic oxidation of Rieske-type dioxygenases involves substrate binding to the active center, molecular binding of oxygen to the ferrous ion, and one electron reduction of molecular oxygen by the Rieske center, followed by formation of reactive FeV = O(OH) species and cis-dihyroxylation of the aromatic substrate. Recent protein X-ray crystallographic study of naphthalene dioxygenase showed structures of substrate-enzyme and substrate-O2-enzyme complexes (5, 29). The substrate oxidation mechanism in the biomimetic system has also been suggested (11, 15). In addition, bacterial dioxygenase showed unusual monooxygenase activity toward a diverse substrates (4).

FIG. 2.

Organization of biphenyl dioxygenase of P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707.

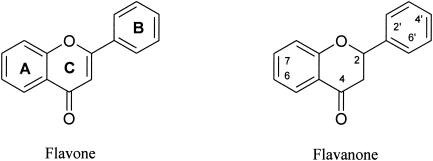

Comparing chemical structures of biphenyl and flavone (Fig. 3), flavones may be a substrate for biphenyl dioxygenase. Flavones have also been implicated in various physiological activities, such as antioxidants, phytoestrogens in controlling breast cancer incidence, and osteogenesis, for example, and in chemotaxis of nitrogen-fixing bacteria (23, 24, 34). Considering this, there has been an increasing interest in the production of novel compounds from flavones using microbial reactions (25, 26, 37). Previously, biphenyl dioxygenase from P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707 was shown to produce cis-2′,3′-dihydrodiol on the B ring of flavone (33). During the biotransformation of flavanone, as a structural analog of flavone, the enzyme produced an epoxide functional group between C2′ and C3′ on the B ring of the flavanone, which has not been reported previously for prokaryotic dioxygenase (31, 36, 39). Here, we report a novel prokaryotic monooxygenase reaction that results in the production of an epoxide on the flavanone B ring by biphenyl dioxygenase rather than producing a cis-dihydrodiol.

FIG. 3.

Structures and nomenclatures of flavone and flavanone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Flavanone, 2′-hydroxyflavanone, 3′-hydroxyflavanone, 4′-hydroxyflavanone, 6-hydroxyflavanone, 7-hydroxyflavanone, and 4′,5,7-trihydroxyflavanone (naringenin) were purchased from Indofine Chemical Company (Somerville, NJ). High-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade organic solvents were purchased from Duksan Co. (Ansan, Korea).

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Escherichia coli JM109(pJHF108) carrying the biphenyl dioxygenase gene from P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707 and E. coli JM109(pJHF3051) carrying the modified toluene dioxygenase gene from P. putida F1 (22) were kindly provided by K. Furukawa at Kyushu University, Japan. Escherichia coli JM109(pJHF108) and E. coli JM109(pJHF3051) were grown from the seed culture in 30 ml of LB medium containing 50 μg of ampicillin/ml overnight. The seed culture was used to inoculate 3 liters of LB medium containing 50 μg of ampicillin/ml in a 5-liter fermentor (Korea Fermentor Co., Seoul, Korea) with shaking at 200 rpm and 1.5-liter/min aeration at 37°C for 8 h. The culture broth was centrifuged using Supra 22K (Hannil Instruments, Inchon, Korea) at 7,000 rpm for 10 min. The cells were washed three times with 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) and resuspended in the same buffer, adjusting the optical density at 600 nm to 10 by using a UVIKON 923 spectrophotometer (Kontro Instrument, Fantoly, Italy). Flavanone was added in final concentration at 100 μM to the resuspended bacterial culture with 400 ml in a 1-liter flask. In addition, glucose as an energy supplier for the reaction was added to the culture in a final concentration of 1 mM. The reaction mixture was incubated on a shaker at 250 rpm at 37°C for 6 h and extracted three times with ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate extract was evaporated in vacuo and redissolved in methanol.

HPLC.

Analytical HPLC was performed by using a Varian ProStar HPLC apparatus (Walnut Creek, CA) equipped with a photodiode array detector. For the analysis of flavanone and its metabolite, a Sumi Chiral OA-7000 column (5-μm particle size, 4.6 mm by 25 cm; Sumika Chemical Analysis Service, Ltd., Osaka, Japan) was used with the mobile phase, which contained 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 3.0) and 100% acetonitrile solution. The elution program for the mobile phase, which was composed of phosphate buffer-acetonitrile solution containing 0.1% acetic acid, was as follows: 10% acetonitrile at 0 min, 30% acetonitrile at 10 min, 60% acetonitrile at 40 min, 90% acetonitrile at 45 min, and 10% acetonitrile at 50 min. The flow rate was 1 ml/min, and UV detection was performed at 270 nm. For the semipreparative HPLC, an HPLC (ThermoSeparation Products, Riviera Beach, FL) equipped with a Beckman ODS C18 column (5-μm particle size, 10 mm by 25 cm; Fullerton, CA) was used. The elution condition was isocratic with the buffer solution, which consisted of 75% methanol with 0.1% acetic acid for 25 min. The flow rate was 2 ml/min, and UV detection was performed at 270 nm. A total of 100 μl with a 100 μM racemic mixture of flavanone or concentrated bacterial metabolites were dissolved in methanol and injected. The metabolite from flavanone produced by biphenyl dioxygenase was eluted at 6 min under the preparative HPLC conditions. The eluted solutions containing the separated 2(R)- and 2(S)-flavanones or metabolites were extracted with ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate layer was evaporated in vacuo and subjected to further analysis.

CD spectroscopy.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra for 2(R)- or 2(S)-flavanone was obtained in methanol with a model 500A spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan). The spectra of the purified compounds were compared to CD spectra published previously (19).

LC/MS.

Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) was carried out by coupling an HP 1100 system to a Quattro LC triple quadruple tandem mass spectrometer (Micromass, Manchester, United Kingdom) in electrospray ionization (ESI+) mode. The source temperature, desolvation temperature, cone voltage, and capillary voltage were kept at 60°C, 180°C, 42 V, and 3.97 kV, respectively. An electron multiplier voltage of 640 V was used. The nebulizer gas and desolvation gas were ultrapure nitrogen set at 87 and 400 liters/h, respectively. LC/MS/MS was performed by the same instrument. The source temperature, desolvation temperature, cone voltage, and capillary voltage were kept at 60°C, 250°C, 33 V, and 3.85 kV, respectively. An electron multiplier voltage of 640 V and a collision energy of 59.9 was used. The nebulizer gas and desolvation gas were ultrapure nitrogen set at 78 and 624 liters/h, respectively. Ions fragmented were detected in a mass range of 50 to 241.

NMR spectroscopy.

All nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments were performed on a Bruker Avance 400 spectrometer system (9.4 T; Bruker BioSpin Gmbh, Karlsruhe, Germany) at a temperature of 298 K. The NMR spectra of 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, DEPT (13), COSY (1), HMQC (2), and HMBC (3) were collected in CHCl3-d with tetramethylsilane as an internal reference. The concentration of the samples was 50 mM. For 1H-NMR analysis, 16 transients were acquired with a 1-s relaxation delay using 32 K datum points. The 90° pulse was 9.7 μs with a spectral width of 4,000 Hz. 13C-NMR and DEPT spectra were obtained for a spectral width of 8,000 Hz, collecting 64 K datum points. The 90° pulse was 9.8 μs. Two-dimensional spectra were acquired with 2,048 datum points for t2 and 256 for t1 increments.

Biotransformation kinetics.

Biotransformation kinetics by whole cells of E. coli expressing biphenyl dioxygenase were performed as follows. The bacterial culture, which was prepared as described above, was resuspended in 50 ml of phosphate buffer containing 1 mM glucose in a 500-ml flask, adjusting to the final culture concentration at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6. This amounted to 63 μg of total protein per ml of cell culture. The bacterial culture was incubated with 200 μM flavanone (final concentration) on a shaker at 250 rpm and 37°C. Then, 2 ml of the bacterial culture was extracted two times with 2 ml of ethyl acetate, and the extract was evaporated in vacuo. Quantification of metabolites and parent material was monitored by using HPLC with time in triplicate experiments.

RESULTS

Biotransformation of flavanones by bacterial dioxygenases.

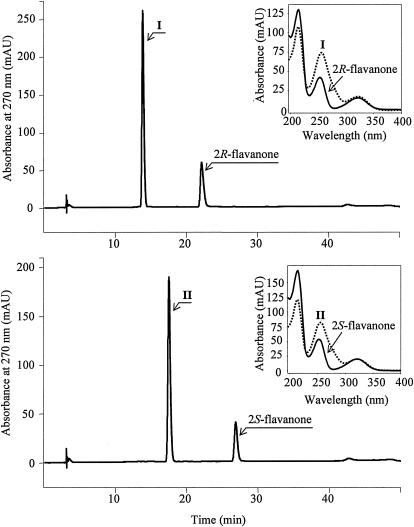

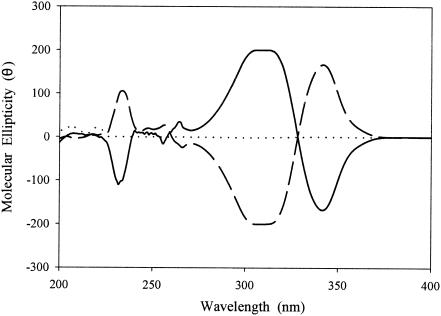

Whole-cell cultures of E. coli expressing biphenyl dioxygenase of P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707 and toluene dioxygenase of P. putida F1 were incubated with flavanone, 6-hydroxyflavanone, 7-hydroxyflavanone, 2′-hydroxyflavanone, 3′-hydroxyflavanone, 4′-hydroxyflavanone, and naringenin, which have a differently substituted hydroxyl group(s) on the flavanone structure. Analysis by HPLC chromatography equipped with a reversed-phase C18 column showed that whole-cell mixtures containing biphenyl dioxygenase underwent reactions to produce two metabolites from each of flavanone, 6-hydroxyflavanone, and 7-hydroxyflavanone (Table 1). The whole-cell mixtures, however, did not produce metabolites from 2′-hydroxyflavanone, 3′-hydroxyflavanone, and naringenin. In addition, the whole-cell mixtures containing toluene dioxygenase did not produce metabolites from all the flavanones tested. Although the reversed-phase C18 column could separate the metabolites produced from the enantiomeric mixtures of flavanone, the column could not separate the starting substrate, flavanone itself (data not shown). Therefore, an HPLC equipped with a chiral column was applied to separate the enantiomeric mixtures of flavanone. The HPLC elution profile using the chiral column showed two discrete peaks that eluted at 22 and 27 min (Fig. 4), which were determined to be 2(R)- and 2(S)-flavanone, respectively, by CD spectroscopy (Fig. 5). Incubations of the whole-cell mixtures containing biphenyl dioxygenase with 2(R)- and 2(S)-flavanone showed a single peak that eluted at 14 min for the metabolite of 2(R)-flavanone and 18 min for the metabolite of 2(S)-flavanone from the chiral column (Table 1). The two peaks eluted at 14 and 18 min showed identical properties with an absorbance maximum at 256 nm and a molecular weight of 240. The molecular weight 240 for the flavanone metabolites could be interpreted to be two different flavanone compounds, which possess either a phenol or an epoxide functional group. By simply comparing these findings with the retention times on the chiral column, the authentic enantiomeric mixtures of 2′-hydroxyflavanone and 3′-hydroxyflavanone, which could be possible metabolites from flavanone, demonstrated retention times at 16 and 17 min and at 19 and 23 min, respectively, which were different from those for metabolites I and II (Table 1 and Fig. 4). In addition, the metabolites were stable at least for 2 weeks at 4°C.

TABLE 1.

Flavanones catalyzed by whole cells of E. coli expressing biphenyl dioxygenase of P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707

| Substrate | Data for the metabolites produced by biphenyl dioxygenase

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC retention times (min) | Absorbance maximum (nm)a | Mass spectrum m/z [M+H]+b | |

| Flavanone | 14 and 18 | 256 | 241 |

| 6-Hydroxyflavanone | 12 and 12.5 | 257 | 257 |

| 7-Hydroxyflavanone | 14 and 14.5 | 274 | 257 |

The value obtained by a photodiode array detector equipped in the HPLC.

The m/z value of the prominent ions of the mass spectra.

FIG. 4.

HPLC chromatograms of biotransformation products produced from 2(R)- or 2(S)-flavanone by whole cells of E. coli expressing biphenyl dioxygenase of P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707. Right inset of each chromatogram are the UV spectra for oxidation intermediates I and II.

FIG. 5.

CD spectra of 2(R)- (cut line) and 2(S)- (solid line) flavanone.

NMR analysis of metabolites I and II.

Based on the molecular mass, 240, of metabolite I, metabolite I (Fig. 4, top panel) was expected to belong to the flavones. The 13C spectrum of the compound showed 15 signals (Table 2). Based on the unsaturation number and at least three oxygenated carbons observed in the 13C spectrum (12), its molecular formula may be C15H12O3. The 13C peak at 191.7 ppm shows the existence of a carbonyl group. According to the interpretation of heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence (HMQC), two 13C peaks at 41.4 and 77.7 ppm are correlated to 1H peaks at 2.93/3.02 and 5.21 ppm, respectively. The 1H peaks are correlated to each other in correlated spectroscopy (COSY). Besides, the 13C peak at 191.7 ppm is long-ranged coupled to the 1H peaks at 2.93/3.02 ppm in heteronuclear multiple bonded connectivity (HMBC). Therefore, three 13C peaks at 191.7, 77.7, and 41.4 ppm should be neighbors. Such three 13C peaks can be found in flavanone, one of the flavones. The structure and nomenclature of flavanone are shown in Fig. 3. Considering this, 77.7, 41.4, and 191.7 ppm are assigned C2, C3, and C4 of the flavanone C-ring, respectively. Based on HMBC, C1′ (136.8 ppm) of its B ring can be determined. C1′ is long-ranged coupled to the 1H peak at 4.38 ppm attached to the 13C peak at 67.1 ppm, which is one of three oxygenated carbons. That is, the 13C peak at 67.1 ppm is assigned C2′ of B ring. The 1H peak at 4.38 ppm is correlated with the 1H peak at 4.43 ppm attached to the 13C peak at 69.1 ppm, which is the other oxygenated carbon. As a result, the 13C peak is assigned C3′. According to the interpretation of COSY and HMBC spectra, C4′, C5′, and C6′ can be determined. Since the chemical shifts of C4′ and C5′ are observed at 131.6 and 123.5 ppm, respectively, there is a double bond between C4′ and C5′. Likewise, the chemical shifts of C1′ and C6′ are 136.8 and 122.9 ppm, respectively, so that there should be a double bond between C1′ and C6′. However, since the chemical shifts of C2′ and C3′ are 67.1 and 69.1 ppm, respectively, C2′ is connected to C3′ through a single bond. Based on COSY, HMBC, and DEPT experiments, C5, C6, C7, C8, C9, and C10 can be determined (Table 2). As mentioned previously, in order to satisfy MS data and the Thirteen Rule, the molecular formula of metabolite I should be C15H12O3. One oxygen is contained in the flavanone C ring, and another oxygen belongs to the carbonyl group. Therefore, there is only one oxygen to be assigned. However, both C2′ and C3′ are oxygenated carbons because of their 13C chemical shifts. As a result, the B ring should include an epoxide between C2′ and C3′. The final structure of the metabolite I is 2-(7-oxabicyclo[4.1.0]hepta-2,4-dien-2-yl)-2,3-dihydro-4H-chromen-4-one, which is shown in Fig. 6. As listed in Table 2, 15 13C chemical shifts of the metabolite II are very similar to those of the metabolite I within 1 ppm. Therefore, both compounds may be isomers. Based on the comparison of the 13C chemical shifts, 15 13C peaks of the metabolite II can be easily assigned as listed in Table 2. Although all 13C chemical shifts of two compounds ranged within 1 ppm, 1H chemical shifts of H2, H2′, and H5′ show differences in their coupling constants. Like the metabolite I, the B ring should include an epoxide between C2′ and C3′.

TABLE 2.

Total assignment of the 1H- and 13C-NMR data of the metabolites produced from 2(R)- and 2(S)-flavanone

| Metabolite from 2R-flavanone

|

Metabolite from 2S-flavanone

|

Assignment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ of 13C | δ of 1H | HMBC | δ of 13C | δ of 1H | HMBC | |

| 40.4 | 2.93 (dd 4.0, 16.8) | 42.3 | 2.97 (dd 8.5, 16.9) | 3 | ||

| 3.02 (dd 11.0, 16.8) | 3.03 (dd 12.6, 16.9) | |||||

| 67.1 | 4.38 (d 6.0) | C2′/H6′ | 67.2 | 4.34 (ddd 1.0, 1.6, 6.0) | C2′/H6′ C2′/H4′ | 2′ |

| 69.1 | 4.43 (m) | C3′/H2′ | 69.1 | 4.44 (m) | C3′/H5′, C3′/H2′ | 3′ |

| 77.7 | 5.21 (dd 3.9, 11.0) | C2/H3, C2/H6′ | 78.5 | 5.17 (ddd 2.5, 3.7, 7.8) | C2/H6′, C2/H2′, C2/H3 | 2 |

| 118.0 | 7.01 (dd 1.1, 8.2) | C8/H6 | 117.9 | 7.02 (td 1.0, 8.4) | C8/H6 | 8 |

| 121.1 | C10/H6, C10/H8 | 120.9 | C10/H6, C10/H8 | 10 | ||

| 121.8 | 7.06 (dd 7.0, 8.0) | C6/H8 | 121.7 | 7.04 (dd 7.1, 8.1) | C6/H8 | 6 |

| 122.9 | 6.12 (td 1.2, 5.3) | C6′/H4′, C6′/H2′ | 122.3 | 6.17 (td 1.4, 5.3) | C6′/H5′, C6′/H4′, C6′/H2, C6′/H2′ | 6′ |

| 123.5 | 6.03 (ddd 1.2, 5.3, 9.5) | C5′/H4′ | 123.8 | 6.05 (ddd 1.8, 5.3, 9.6) | 5′ | |

| 127.1 | 7.91 (dd 1.7, 8.0) | C5/H7 | 127.1 | 7.91 (dd 1.9, 7.9) | C5/H7 | 5 |

| 131.6 | 5.97 (dd 2.7, 9.5) | C4′/H6′, C4′/H3′ | 131.2 | 5.98 (td 2.5, 9.4) | C4′/H6′, C4′/H2′ | 4′ |

| 136.2 | 7.50 (ddd 1.7, 7.0, 8.2) | C7/H5 | 136.2 | 7.50 (ddd 1.8, 7.0, 8.6) | C7/H5 | 7 |

| 136.8 | C1′/H5′, C1′/H2′, C1′/H2 | 137.2 | C1′/H5′, C1′/H2′, C1′/H2, C1′/H3 | 1′ | ||

| 160.8 | C9/H7 | 161.3 | C9/H5, C9/H8, C9/H7 | 9 | ||

| 191.7 | C4/H5, C4/H3 | 191.8 | C4/H5, C4/H3 | 4 | ||

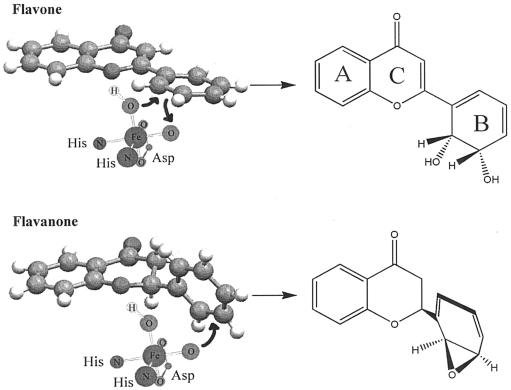

FIG. 6.

Proposed reaction mechanism of flavone (A) and flavanone (B) oxidation by biphenyl dioxygenase. The structures were produced from Molecular Mechanics Calculation using HyperChem, and the X-ray crystallographic structures of flavone and flavanones (CCDC) were approximately the same as the calculated ones.

Biotransformation kinetics of 2(R)- and 2(S)-flavanone by whole cells expressing biphenyl dioxygenase.

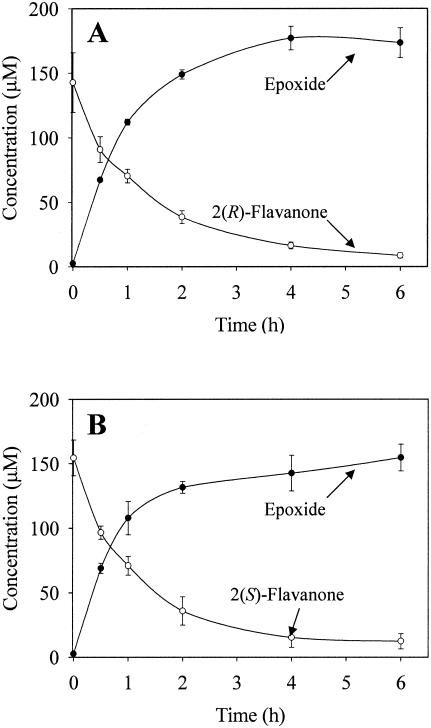

Whole cells expressing biphenyl dioxygenase were incubated with 200 μM 2(R)- and 2(S)-flavanones to examine the catalytic biotransformation efficiency of the enzyme. As biphenyl dioxygenase metabolized 2(R)- and 2(S)-flavanones, the enzyme concomitantly produced the metabolites, as shown in Fig. 7. The substrates 2(R)- and 2(S)-flavanones were biotransformed ca. 73% after 2 h of incubation. The initial rate of production of 2(R)- or 2(S)-flavanone epoxides was 35.3 nmol/min/mg of total protein. The enzyme, however, did not show any catalytic preference to the enantiomeric substrates, 2(R)- and 2(S)-flavanones.

FIG. 7.

Biotransformation kinetics of 2(R)-flavanone (A) and 2(S)-flavanone (B) to the corresponding flavanone epoxides by whole cells of E. coli expressing biphenyl dioxygenase of P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707. Symbols: ○, flavanone; •, flavanone epoxide.

DISCUSSION

Biphenyl dioxygenase of P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707 mediates a reaction to insert two oxygen atoms onto C2 and C3 of the biphenyl ring, resulting in the formation of biphenyl cis-dihydrodiol (17, 18). Our previous report (32) also showed the same dioxygenase activity toward flavone, producing flavone cis-2′,3′-dihydrodiol. When the enzyme was incubated with flavanone, it showed an unusual eukaryotic monooxygenase activity, producing an epoxide functional group between C2′ and C3′ of the flavanone B ring. The same epoxide formation was also observed from 6- and 7-hydroxyflavanone biotransformation. Monooxygenase activity by dioxygenases has been reported before, but they all reported monohydroxylated products (30). Toluene dioxygenase from P. putida F1, however, did not show biotransformation activity toward flavanone. Due to the same molecular mass of epoxide and hydroxyl flavanone flavanone, 240, mass spectral data are not enough to determine the structure for the metabolite. Therefore, the presence of the epoxide functional group on the flavanone B ring of the metabolite was exhaustively determined by different analyses using NMR and HPLC retention times on a chiral column. Unlike the chemical shifts of C1′ and C6′ at 136.8 and 122.9 ppm, respectively, and of C4′ and C5′ at 131.6 and 123.5 ppm, respectively, the chemical shifts of C2′ and C3′ were observed at 67.1 and 69.1 ppm, respectively. Therefore, there should be a single bond between C2′ and C3′, which cannot be shown with phenol structures of the flavanone B ring. The HPLC retention times of 2(R)- and 2(S)-flavanone-2′,3′-epoxide on the chiral column were 14 and 18 min, respectively, which were different from those of authentic enantiomeric mixtures of 2′-hydroxyflavanone that eluted at 16 and 17 min and of 3′-hydroxyflavanone that eluted at 19 and 23 min. However, formation of the epoxide group was not found in the biotransformation of flavanone by DNA-shuffled biphenyl dioxygenase expressed in Streptomyces lividans (9). The recombinant S. lividans expressing the modified biphenyl dioxygenase produced 2′-hydroxyflavanone, 3′-hydroxyflavanone, and 2′,3′-dihydroxyflavanone from flavanone. Until now, biological epoxide formation on the aromatic ring structure has been only found with eukaryotic oxygenases such as in the case of the cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (21, 44). The reaction on the aromatic ring by eukaryotic cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, leading to the production of the epoxide functional group, is well documented (21).

The structure of flavanone was compared to that of flavone, as well as the structures of 2(R)- and 2(S)-flavanone. Figure 7 shows the three-dimensional structure of flavone and flavanone enantiomers, and a marked difference is found between flavone and the flavanones. Interestingly, there was little difference in the orientation of the B ring between the flavanone enantiomers due to inversion of the half-chair conformation at C2 of the C ring. We also used the known protein structures of naphthalene dioxygenase to simulate substrate binding at the active center (5, 29). In the case of flavone, activated oxygen may interact with the substrate in a side-on mode as shown for naphthalene dioxygenase (Fig. 7), but the B ring of flavanone should interact differently with oxygen atoms due to the 90° rotation of the ring. The hydroxyl group of FeV=O(OH) is located too far to interact with C2′ and C3′, and which eventually leads to epoxide formation. Based on the biotransformation kinetics, however, biphenyl dioxygenase, stoichiometrically converted 2(R)- and 2(S)-flavanone to their corresponding epoxide forms in almost equal amounts. This suggested that biphenyl dioxygenase did not recognize the configurational difference at the stereocenter C2 of the flavanone C ring.

In summary, we have shown the first prokaryotic epoxide formation on the aromatic ring structure by biphenyl dioxygenase, which suggests different substrate configurations may react differently with the high valent Fe oxo species of biphenyl dioxygenase.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. J. Cha in the Department of Biotechnology, Chung-Ang University, Anseong, Korea, for criticism of the manuscript.

This study was partly supported by grants from MOST/KOSEF to the Environmental Biotechnology National Core Research Center (grant R15-2003-012-02002-) of Korea and from the Sustainable Water Resources Research Center of 21st Century Frontier R&D program through the Water Reuse Technology Center at Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bax, A., and R. Freeman. 1981. A simple method for suppressing dispersion-mode contributions in NMR spectra: the “pseudo echo.” J. Magn. Reson. 43:333-338. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bax, A., R. Griffey, and B. Hawkins. 1983. Correlation of proton and nitrogen-15 chemical shifts by multiple quantum NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 55:301-315. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bax, A., and M. Summers. 1986. 1H and 13C assignments from sensitivity-enhanced detection of heteronuclear multiple-bond connectivity by 2D multiple quantum NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 108:2093-2094. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd, D. R., N. D. Sharma, and C. C. Allen. 2001. Aromatic dioxygenases: molecular biocatalysis and applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 12:564-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carredano, E., A. Karlsson, B. Kauppi, D. Choudhury, R. E. Parales, J. V. Parales, K. Lee, D. T. Gibson, H. Eklund, and S. Ramaswamy. 2000. Substrate binding site of naphthalene 1,2-dioxygenase: functional implications of indole binding. J. Mol. Biol. 296:701-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerniglia, C. E., and D. T. Gibson. 1980. Fungal oxidation of (+/−)-9,10-dihydroxy-9,10-dihydrobenzo[a]pyrene: formation of diastereomeric benzo[a]pyrene 9,10-diol 7,8-epoxides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:4554-4558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerniglia, C. E., and D. T. Gibson. 1980. Fungal oxidation of benzo[a]pyrene and (+/−)-trans-7,8-dihydroxy-7,8-dihydrobenzo[a]pyrene. Evidence for the formation of a benzo[a]pyrene 7,8-diol-9,10-epoxide. J. Biol. Chem. 255:5159-5163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cerniglia, C. E., J. C. Morgan, and D. T. Gibson. 1979. Bacterial and fungal oxidation of dibenzofuran. Biochem. J. 180:175-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chun, H. K., Y. Ohnishi, K. Shindo, N. Misawa, K. Furukawa, and S. Horinouchi. 2003. Biotransformation of flavone and flavanone by Streptomyces lividans cells carrying shuffled biphenyl dioxygenase genes. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzymatic 21:113-121. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cirino, P. C., and F. H. Arnold. 2002. Protein engineering of oxygenases for biocatalysis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 6:130-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costas, M., M. P. Mehn, M. P. Jensen, and L. J. Que. 2004. Dioxygen activation at mononuclear nonheme iron active sites: enzymes, models, and intermediates. Chem. Rev. 104:939-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crews, P., J. Rodriquez, and M. Jaspars. 1998. Organic structure analysis. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 13.Dodrell, D., D. Pegg, and M. Bendall. 1982. Distortionless enhancement of NMR signals by polarization transfer. J. Magn. Reson. 48:323-327. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ensley, B. D., and D. T. Gibson. 1983. Naphthalene dioxygenase: purification and properties of a terminal oxygenase component. J. Bacteriol. 155:505-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujita, M., M. Costas, and L. J. Que. 2003. Iron-catalyzed olefin cis-dihydroxylation by H2O2: electrophilic versus nucleophilic mechanisms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125:9912-9913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furukawa, K. 2000. Engineering dioxygenases for efficient degradation of environmental pollutants. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 11:244-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furukawa, K., and N. Arimura. 1987. Purification and properties of 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase from polychlorinated biphenyl-degrading Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes and Pseudomonas aeruginosa carrying the cloned bphC gene. J. Bacteriol. 169:924-927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furukawa, K., and T. Miyazaki. 1986. Cloning of a gene cluster encoding biphenyl and chlorobiphenyl degradation in Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes. J. Bacteriol. 166:392-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaffield, W. 1970. Circular dichroism, optical rotatory dispersion and absolute configuration of flavanones, 3-hydroxyflavanones and their glycosides: determination of aglycone chirality in flavanone glycosides. Tetrahedron 26:4093-4108. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibson, D. T., D. L. Cruden, J. D. Haddock, G. J. Zylstra, and J. M. Brand. 1993. Oxidation of polychlorinated biphenyls by Pseudomonas sp. strain LB400 and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707. J. Bacteriol. 175:4561-4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guengerich, F. P. 2003. Cytochrome P450 oxidations in the generation of reactive electrophiles: epoxidation and related reactions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 409:59-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirose, J., A. Suyama, S. Hayashida, and K. Furukawa. 1994. Construction of hybrid biphenyl (bph) and toluene (tod) genes for functional analysis of aromatic ring dioxygenases. Gene 138:27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollman, P. C., and M. B. Katan. 1999. Dietary flavonoids: intake, health effects and bioavailability. Food Chem. Toxicol. 37:937-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hollman, P. C., and M. B. Katan. 1999. Health effects and bioavailability of dietary flavonols. Free Radic. Res. 31(Suppl.):S75-S80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosny, M., K. Dhar, and J. P. Rosazza. 2001. Hydroxylations and methylations of quercetin, fisetin, and catechin by Streptomyces griseus. J. Nat. Prod. 64:462-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ibrahim, A. R., and Y. J. Abul-Hajj. 1990. Microbiological transformation of (+/−)-flavanone and (+/−)-isoflavanone. J. Nat. Prod. 53:644-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jerina, D. M., J. W. Daly, A. M. Jeffrey, and D. T. Gibson. 1971. cis-1,2-Dihydroxy-1,2-dihydronaphthalene: a bacterial metabolite from naphthalene. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 142:394-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jerina, D. M., J. W. Daly, B. Witkop, P. Zaltzman-Nirenberg, and S. Udenfriend. 1968. The role of arene oxide-oxepin systems in the metabolism of aromatic substrates. 3. Formation of 1,2-naphthalene oxide from naphthalene by liver microsomes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 90:6525-6527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karlsson, A., J. V. Parales, R. E. Parales, D. T. Gibson, H. Eklund, and S. Ramaswamy. 2003. Crystal structure of naphthalene dioxygenase: side-on binding of dioxygen to iron. Science 299:1039-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keenan, B. G., T. Leungsakul, B. F. Smets, and T. K. Wood. 2004. Saturation mutagenesis of Burkholderia cepacia R34 2,4-dinitrotoluene dioxygenase at DntAc valine 350 for synthesizing nitrohydroquinone, methylhydroquinone, and methoxyhydroquinone. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3222-3231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim, J. H., K. H. Stansbury, N. J. Walker, M. A. Trush, P. T. Strickland, and T. R. Sutter. 1999. Metabolism of benzo[a]pyrene and benzo[a]pyrene-7,8-diol by human cytochrome P450 1B1. Carcinogenesis 20:515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim, S.-Y., J. Jung, Y. Lim, J.-H. Ahn, S.-I. Kim, and H.-G. Hur. 2003. cis-2′,3′-Dihydrodiol production on flavone B-ring by biphenyl dioxygenase from Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707 expressed in Escherichia coli. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 84:261-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell, K. H., C. E. Rogge, T. Gierahn, and B. G. Fox. 2003. Insight into the mechanism of aromatic hydroxylation by toluene 4-monooxygenase by use of specifically deuterated toluene and p-xylene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:3784-3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nijveldt, R. J., E. van Nood, D. E. van Hoorn, P. G. Boelens, K. van Norren, and P. A. van Leeuwen. 2001. Flavonoids: a review of probable mechanisms of action and potential applications. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 74:418-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oesch, F., D. M. Jerina, J. W. Daly, A. Y. Lu, R. Kuntzman, and A. H. Conney. 1972. A reconstituted microsomal enzyme system that converts naphthalene to trans-1,2-dihydroxy-1,2-dihydronaphthalene via naphthalene-1,2-oxide: presence of epoxide hydrase in cytochrome P-450 and P-448 fractions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 153:62-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Resnick, S. M., K. Lee, and D. T. Gibson. 1996. Diverse reactions catalyzed by naphthalene dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. strain NCIB 9816. J. Ind. Microbiol. 17:438-457. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seeger, M., M. Gonzalez, B. Camara, L. Munoz, E. Ponce, L. Mejias, C. Mascayano, Y. Vasquez, and S. Sepulveda-Boza. 2003. Biotransformation of natural and synthetic isoflavonoids by two recombinant microbial enzymes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5045-5505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selander, H. G., D. M. Jerina, and J. W. Daly. 1975. Metabolism of chlorobenzene with hepatic microsomes and solubilized cytochrome P-450 systems. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 168:309-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spain, J. C., and D. T. Gibson. 1988. Oxidation of substituted phenols by Pseudomonas putida F1 and Pseudomonas sp. strain JS6. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:1399-1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subramanian, V., T. N. Liu, W. K. Yeh, C. M. Serdar, L. P. Wackett, and D. T. Gibson. 1985. Purification and properties of ferredoxinTOL. A component of toluene dioxygenase from Pseudomonas putida F1. J. Biol. Chem. 260:2355-2363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suenaga, H., M. Mitsuoka, Y. Ura, T. Watanabe, and K. Furukawa. 2001. Directed evolution of biphenyl dioxygenase: emergence of enhanced degradation capacity for benzene, toluene, and alkylbenzenes. J. Bacteriol. 183:5441-5444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tao, Y., A. Fishman, W. E. Bentley, and T. K. Wood. 2004. Oxidation of benzene to phenol, catechol, and 1,2,3-trihyroxybenzene by toluene 4-monooxygenase of Pseudomonas mendocina KR1 and toluene 3-monooxygenase of Ralstonia pickettii PK01. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3814-3820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vardar, G., and T. K. Wood. 2004. Protein engineering of toluene-o-xylene monooxygenase from Pseudomonas stutzeri OX1 for synthesizing 4-methylresorcinol, methylhydroquinone, and pyrogallol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3253-3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wackett, L. P., and C. D. Hershberger. 2001. Biocatalysis and biodegradation: microbial transformation of organic compounds. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 45.Whited, G. M., W. R. McCombie, L. D. Kwart, and D. T. Gibson. 1986. Identification of cis-diols as intermediates in the oxidation of aromatic acids by a strain of Pseudomonas putida that contains a TOL plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 166:1028-1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]