Abstract

Background

FAZ053 triggers an antitumor response by targeting programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), thereby activating effector T cells and negatively regulating T cells. This study assessed the safety, tolerability, and preliminary efficacy of FAZ053 monotherapy and in combination with spartalizumab in patients with advanced solid tumors.

Methods

This phase I, multicenter, open-label study (NCT02936102) included dose escalation and dose expansion. The primary objectives were safety and tolerability; secondary objectives were pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and preliminary antitumor activity.

Results

Of the 154 patients treated, 49 (52.7%) patients receiving FAZ053 monotherapy experienced at least one treatment-related adverse event (TRAE), of whom 6 (6.5%) experienced grade ≥3 TRAEs; 35 patients (57.4%) receiving combination therapy experienced TRAEs, of whom 3 (4.9%) experienced grade ≥3 TRAEs. One patient who received FAZ053 1600 mg every 6 weeks (Q6W) and one who received FAZ053 20 mg every 3 weeks (Q3W) with spartalizumab 300 mg Q3W experienced dose-limiting toxicities of grade 4 creatinine increase and grade 3 liver function test increased, respectively. The median duration of exposure was 105 days for monotherapy and 85 days for combination therapy. During dose escalation, response was observed in 3 (5.1%) and 3 (4.9%) patients receiving FAZ053 monotherapy and combination therapy, respectively. In dose expansion, response was observed in 2 (50%) patients with advanced alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS) and 3 (30%) patients with advanced chordoma receiving FAZ053 monotherapy. FAZ053 demonstrated a dose-proportional pharmacokinetic profile with a terminal half-life of 20.6 days at 1200 mg Q3W. Biomarker analysis showed increased immune gene expression following FAZ053 treatment. The recommended dose for expansion was 1200 mg Q3W.

Conclusion

FAZ053 monotherapy was well tolerated and effective in maintaining disease control in various tumors including ASPS and chordoma. The anticipated synergistic effect of combined programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and PD-L1 inhibition was not observed. These findings contribute to the growing evidence that rare, phenotypically ‘immune cold’ sarcomas, such as ASPS and chordoma, can become responsive to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Key words: FAZ053, PD-L1, spartalizumab, advanced alveolar soft part sarcoma, chordoma

Highlights

-

•

This study evaluated FAZ053 with and without spartalizumab.

-

•

FAZ053 with and without spartalizumab was well-tolerated.

-

•

The anticipated synergistic effect of FAZ053 in combination with spartalizumab was not observed.

-

•

FAZ053 monotherapy showed activity in ASPS, chordoma, and triple-negative breast cancer.

-

•

A recommended dose for expansion of 1200 mg Q3W was declared based on the study findings.

Introduction

T-cell activation is regulated by finely tuned interactions between the antigen receptor and immune checkpoints of costimulatory molecules and coinhibitory signals.1 One of these checkpoint pathways, the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway, negatively regulates T cells, thereby controlling local inflammatory responses and maintaining self-tolerance.2, 3, 4 PD-1 is considered a coinhibitory receptor, and PD-L1 (B7-H1) is the primary PD-1 ligand that is upregulated in tumors, wherein it inhibits cytokine production and the cytolytic activity of PD-1+ and tumor-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.5,6

Anti-PD-L1 and anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have demonstrated safety and efficacy clinically in a broad range of tumor types.7,8 Both FAZ053 and spartalizumab are high-affinity, humanized immunoglobulin (Ig) G4 mAbs. FAZ053 binds to human PD-L1 and inhibits its interaction with PD-1 and B7-1 found on monocytes, dendritic cells, and B cells. It enhances interleukin-2 production, as demonstrated in ex vivo lymphocyte stimulation assays, in humans. Spartalizumab binds to human PD-1 and inhibits its interaction with PD-L1 and PD-L2 (B2-DC). As such, PD-1 and PD-L1 mediate overlapping, yet distinct, functions of T cells. While both receptors deliver negative signals to the T cell when engaged, PD-L1 may mediate an immunosuppressive function by potentially blocking B7-1 from activating T cells by binding to CD-28, thus further dampening the immune response.9,10 Given the distinct roles of PD-L1/PD-1 and PD-L1/B7-1 interactions in immune regulation, it is possible that dual immune checkpoint blockade with anti-PD-L1 and anti-PD-1 mAbs is complementary for antitumor immunity and increased activation of T cells. In an MC38 murine model of colon adenocarcinoma, the combination of FAZ053 and an anti-PD-1 mAb demonstrated enhanced antitumor activity when compared with either mAb alone.11 Based on the suggestion that certain malignancies may benefit from simultaneous inhibition of PD-L1 and PD-1, this study aimed to explore the safety and efficacy of this combination in a variety of tumor types.

Herein, we report the findings of a first-in-human study that evaluated the safety, tolerability, preliminary efficacy, pharmacokinetics (PK), and pharmacodynamics (PD) of FAZ053 monotherapy and in combination with spartalizumab.

Patients and methods

Study design and treatment

This was a multicenter, open-label, two-part, phase I study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02936102). Dose escalation of FAZ053 began at 80 mg every 3 weeks (Q3W) as monotherapy and at 20 mg Q3W when combined with spartalizumab at its recommended dose of 300 mg Q3W (combination therapy). The starting doses were selected based on preclinical safety, tolerability, and PK findings of FAZ053 and spartalizumab. The study drugs were administered intravenously until disease progression, intolerable toxicity, or withdrawal of consent. Dose adjustments were permitted for patients who experienced treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs). The protocol included a dose-expansion part to further evaluate the study drugs based on the antitumor activity observed during dose escalation and upon determination of the recommended doses for expansion (RDEs) for FAZ053 as monotherapy and as a combination partner of spartalizumab.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions and the appropriate regulatory authorities. All patients provided written informed consent. The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, as defined by the International Conference on Harmonisation.

Patients

This study enrolled patients aged ≥18 years with advanced/metastatic solid tumors whose disease had progressed despite receiving standard therapy or for whom no standard therapy was available. Eligible patients may or may not have received prior treatment with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) but must possess an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of ≤2, adequate organ function, and a disease site amenable to biopsy. Patients without measurable disease as determined by RECIST version 1.1 were eligible only for the dose-escalation part.12 Key exclusion criteria included symptomatic central nervous system (CNS) metastases or a tumor that required local CNS-directed therapy or increasing doses of corticosteroids within 2 weeks of screening, history of impaired cardiac function, active autoimmune disease, and pneumonitis. Patients who received prior treatment with an anti-PD-L1 inhibitor were not permitted for enrollment in the FAZ053 monotherapy cohorts. Patients who discontinued prior ICI therapies because of treatment-related toxicities were excluded.

Study objectives

The primary objectives were to assess the safety and tolerability of FAZ053 monotherapy and combination therapy and identify RDEs and optimal treatment schedules. The secondary objectives included the characterization of PK and PD profiles of the study drugs, assessment for the emergence of antibodies against FAZ053 and spartalizumab, characterization of changes in the immune infiltrate in tumors, and assessment of preliminary antitumor activity following the administration of the study drugs. Exploratory objectives included the assessment of biomarkers for immunological response in the tumor and the association between tumor surface marker expression and clinical response.

Assessments

Safety assessments were conducted according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) version 4.03. Serologic, histologic, and immunological assessments were carried out by the investigator to elucidate the role of immune mediation in an AE and exclude alternative causalities, where appropriate. Tumor response was assessed locally by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) according to RECIST version 1.1 criteria and immune-related response criteria13 at baseline and then every 3 cycles starting from cycle 4 day 1 (C4D1) until the end of treatment. When a patient attained a response, the findings would be confirmed by a repeat assessment after at least 4 weeks. Patients initially receiving FAZ053 monotherapy in dose escalation or dose expansion who demonstrated a response per RECIST version 1.1 criteria may, upon radiological disease progression, switch to combination therapy at the dose level that had been evaluated in dose escalation and met the escalation with overdose control (EWOC) principle. Newly obtained tumor biopsy samples were collected at baseline, between C3D1 and C3D15, at C11D1, and then every 8 cycles to evaluate the effect of the study drugs and determine how changes in biomarkers may relate to drug exposure and clinical outcomes. An initial assessment of a hematoxylin and eosin-stained slide for tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) counts guided further immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis of the tumor microenvironment. Other biomarkers of immunologic response were assessed by RNA sequencing.

PK analysis was carried out using validated liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry methods. A noncompartmental analysis of PK measurements was carried out to assess the maximum concentration (Cmax), time to reach maximum plasma concentration (Tmax), the area under the plasma concentration–time curve (AUC) from time zero to time to last measurable concentration (AUC0–tlast) and AUCtau (C1D1 and C3D1), time to last measurable concentration (Tlast), Clast, T1/2, and accumulation ratio of FAZ053 monotherapy and FAZ053 in combination with spartalizumab.

Statistical analyses

Dose escalation was guided by emerging safety, tolerability, PK, and PD data and a two-parameter Bayesian logistic regression model employing EWOC criteria under which a dose may be administered only to newly enrolled patients if the risk of excessive toxicity occurring at that dose is <25%.14,15 Definitions of dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) are summarized in Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105051. The incidence of DLTs in the first 21 days of FAZ053 monotherapy and 42 days of combination therapy was summarized by dose. Patients who received at least 1 dose of the study drug and had postbaseline tumor scans were included in the evaluation for antitumor activity. Summary statistics are provided where appropriate.

Results

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

A total of 154 patients were enrolled (Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105051). One patient who initially received FAZ053 monotherapy subsequently switched to the combination therapy. The every 6 weeks (Q6W) schedule was not explored for combination therapy. The median age of all treated patients was 58 years (range 25-79 years). Overall, 87 (56.5%) patients had received three or more lines of prior antineoplastic therapy; 12 (7.7%) received prior ICI therapy. Patient demographics characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105051. As of 18 January 2022, seven (4.6%) patients continued to receive FAZ053 1200 mg Q3W. The reasons for treatment discontinuation were disease progression (n = 112, 72.7%), followed by subject/guardian decision (n = 11, 7.1%), physician decision (n = 10, 6.5%), death (n = 8, 5.2%), and AEs (n = 6, 3.9%). No deaths related to the study drugs were reported (Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105051).

Table 1.

Summary of patient demographic characteristics

| Characteristics | Dose escalation |

Dose expansion |

All patients (N = 154) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAZ053 monotherapy (n = 59) | FAZ053 + spartalizumab (n = 61) | FAZ053 1200 mg Q3W (n = 34) | ||

| Age (years) | ||||

| Median (range) | 58.0 (25-77) | 58.0 (27-77) | 58.0 (26-79) | 58.0 (25-79) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 28 (47.5) | 21 (34.4) | 11 (32.4) | 60 (39.0) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Asian | 23 (39.0) | 19 (31.1) | 9 (26.5) | 51 (33.1) |

| Black | 0 (0) | 4 (6.6) | 1 (2.9) | 5 (3.2) |

| White | 33 (55.9) | 29 (47.5) | 24 (70.6) | 86 (55.8) |

| Other | 1 (1.7) | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.9) |

| Unknown | 2 (3.4) | 7 (11.5) | 0 (0) | 9 (5.8) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 18 (30.5) | 20 (32.8) | 22 (64.7) | 60 (39.0) |

| 1 | 41 (69.5) | 34 (55.7) | 12 (35.3) | 87 (56.5) |

| 2 | 0 (0) | 7 (11.5) | 0 (0) | 7 (4.5) |

| Classification of the primary tumora, n (%) | ||||

| Breast | ||||

| Non-TNBC | 4 (6.8) | 14 (23.0) | 0 (0) | 18 (11.7) |

| TNBC | 3 (5.1) | 0 (0) | 20 (58.8) | 23 (14.9) |

| Gastrointestinal | 16 (27.1) | 15 (24.6) | 0 (0) | 31 (20.1) |

| Genitourinary | 13 (22.0) | 11 (18.0) | 0 (0) | 24 (15.6) |

| Melanoma | 3 (5.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.9) |

| Sarcoma | ||||

| ASPS | 2 (3.4) | 1 (1.6) | 4 (11.8) | 7 (4.5) |

| Chordoma | 5 (8.5) | 4 (6.6) | 10 (29.4) | 19 (12.3) |

| Other | 5 (8.5) | 5 (8.2) | 0 (0) | 10 (6.5) |

| Thoracic | 4 (6.8) | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 6 (3.9) |

| Other | 4 (6.8) | 9 (14.8) | 0 (0) | 13 (8.4) |

| Number of prior antineoplastic therapies, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 7 (11.9) | 3 (4.9) | 8 (23.5) | 18 (11.7) |

| 1 | 9 (15.3) | 7 (11.5) | 8 (23.5) | 24 (15.6) |

| 2 | 7 (11.9) | 11 (18.0) | 7 (20.6) | 25 (16.2) |

| ≥3 | 36 (61.0) | 40 (65.6) | 11 (32.4) | 87 (56.5) |

| Prior immunotherapy, n (%) | ||||

| Anti-PD-L1 | 0 (0) | 3 (4.9) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.9) |

| Anti-PD-1 | 2 (3.4) | 5 (8.2) | 1 (2.9) | 8 (5.2) |

| Anti-CTLA-4 | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) |

ASPS, advanced alveolar soft part sarcoma; CTLA-A, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PD-1, programmed death-1; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; Q3W, every 3 weeks; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

Refer to Supplementary Table S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105051, for a complete list of primary tumors treated in this study.

Dose-escalation and dose-limiting toxicities

Of the 120 patients who underwent dose escalation, 109 (90.8%) were considered assessable for dose-determining analysis, comprising 59 patients (100%) receiving FAZ053 monotherapy and 50 patients (82%) receiving combination therapy. Two patients experienced DLTs. One patient with Merkel cell carcinoma and baseline grade 1 creatinine increase experienced a DLT of grade 4 creatinine increase at C1D8 of FAZ053 1600 mg Q6W. MRI findings suggested extensive retroperitoneal adenopathy. This patient was managed with corticosteroids and hemodialysis, which was subsequently discontinued according to the patient’s decision, and the outcome was fatal. The association between FAZ053 and this DLT could not be excluded. One patient with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving FAZ053 20 mg Q3W and spartalizumab 300 mg Q3W developed a serious AE (SAE) of grade 3 increased liver function test 22 days after C1D1. This was considered a DLT and related to both study drugs, which were interrupted until the patient fully recovered. The maximum tolerated dose was not declared for FAZ053 monotherapy or in combination with spartalizumab.

Safety and tolerability

Overall, 91 of 93 (97.8%) patients receiving FAZ053 monotherapy and 59 of 61 (96.7%) patients receiving combination therapy experienced at least one AE regardless of the causal relationship with the study drugs, of whom 46 (49.5%) and 31 (50.8%), respectively, experienced at least one grade ≥3 AE. Thirty-three (35.5%) patients receiving FAZ053 monotherapy and 27 (44.3%) receiving combination therapy experienced at least one SAE regardless of the causal relationship with the study drug, of whom 27 (29.0%) and 24 (39.3%), respectively, experienced grade ≥3 SAEs.

FAZ053 monotherapy

Forty-nine patients (52.7%) experienced at least one AE suspected to be related to FAZ053 monotherapy, of whom 6 (6.5%) experienced at least one grade ≥3 AE. AEs ≥5% of all grades suspected to be related to FAZ053 were fatigue (n = 14, 15.1%), pruritus (n = 10, 10.8%), rash (n = 8, 8.6%), hypothyroidism (n = 8, 8.6%), diarrhea (n = 7, 7.5%), arthralgia (n = 5, 5.4%), and nausea (n = 5, 5.4%). SAEs of all grades suspected to be related to FAZ053 were experienced by five (5.4%) patients and included arthralgia, increased blood creatinine phosphokinase, decreased appetite, fatigue, hepatic function abnormalities, nausea, renal failure, and vomiting. Four (4.3%) patients experienced at least one grade ≥3 SAE (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S4A, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105051). Overall, patients receiving FAZ053 monotherapy (n = 93) had a median duration of exposure (DOE) of 105 days (range 20-1556 days), with 35 patients (37.6%) exposed to FAZ053 for >126 days.

Table 2.

Summary of adverse events suspected to be related to FAZ053 monotherapy in ≥5% of patients

| Adverse event | Grade | FAZ053 Q3W |

FAZ053 Q6W |

All FAZ053 (N = 93) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80 mg (n = 6) | 240 mg (n = 5) | 800 mg (n = 9) | 1200 mg (n = 50) | 1600 mg (n = 6) | 800 mg (n = 5) | 1200 mg (n = 6) | 1600 mg (n = 6) | |||

| Fatigue, n (%) | Any grade | 3 (50.0) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (22.2) | 4 (8.0) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 14 (15.1) |

| Grade 3/4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Pruritus, n (%) | Any grade | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (22.2) | 5 (10.0) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 10 (10.8) |

| Grade 3/4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Rash, n (%) | Any grade | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (8.0) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 8 (8.6) |

| Grade 3/4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Hypothyroidism, n (%) | Any grade | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (12.0) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (8.6) |

| Grade 3/4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | Any grade | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.0) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 7 (7.5) |

| Grade 3/4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Arthralgia, n (%) | Any grade | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (22.2) | 3 (6.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (5.4) |

| Grade 3/4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Nausea, n (%) | Any grade | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (6.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (5.4) |

| Grade 3/4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

Q3W, every 3 weeks; Q6W, every 6 weeks.

FAZ053 and spartalizumab combination

Thirty-five patients (57.4%) receiving combination therapy experienced at least one AE suspected to be related to the study drugs, of whom 3 (4.9%) experienced at least one grade ≥3 AEs. AEs of ≥5% of all grades suspected to be related to the combination therapy were fatigue (n = 14, 23.0%), diarrhea (n = 8, 13.1%), nausea (n = 7, 11.5%), pruritus (n = 5, 8.2%), anemia (n = 4, 6.6%), increased aspartate aminotransferase (n = 4, 6.6%), and myalgia (n = 4, 6.6%; Table 3 and Supplementary Table S4B, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105051). Overall, patients receiving combination therapy (n = 61) had a median DOE of 85 days (range 11-1421 days), with 23 patients (37.7%) exposed to both study drugs for >126 days.

Table 3.

Summary of adverse events suspected to be related to FAZ053 Q3W in combination with spartalizumab 300 mg Q3W in ≥5% of patients

| Adverse event | Grade | FAZ053 + spartalizumab 300 mg Q3W |

All FAZ053 + spartalizumab (N = 61) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 mg (n = 7) | 60 mg (n = 15) | 200 mg (n = 23) | 600 mg (n = 6) | 800 mg (n = 5) | 1200 mg (n = 5) | |||

| Fatigue, n (%) | Any grade | 1 (14.3) | 2 (13.3) | 6 (26.1) | 3 (50.0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (20.0) | 14 (23.0) |

| Grade 3/4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | Any grade | 0 (0) | 3 (20.0) | 3 (13.0) | 2 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (13.1) |

| Grade 3/4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Nausea, n (%) | Any grade | 1 (14.3) | 2 (13.3) | 3 (13.0) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (11.5) |

| Grade 3/4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Pruritus, n (%) | Any grade | 0 (0) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0) | 5 (8.2) |

| Grade 3/4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Anemia, n (%) | Any grade | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (17.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (6.6) |

| Grade 3/4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased, n (%) | Any grade | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (13.0) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (6.6) |

| Grade 3/4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Myalgia, n (%) | Any grade | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (13.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20.0) | 4 (6.6) |

| Grade 3/4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

Q3W, every 3 weeks.

Pharmacokinetics

The PK of FAZ053 was generally dose proportional, with a terminal half-life of ∼10-22 days (range 2.5-65.4 days). Cmax typically occurred shortly after the infusion was completed. At 1200 mg Q3W, the mean terminal half-life estimated was ∼20.6 days. Plasma concentration profiles (C1/C3 for FAZ053 Q3W and C1/C5 for FAZ053 Q6W) are shown in Supplementary Figure S2A and B, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105051, and the PK parameters are presented in Supplementary Table S5, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105051. Following the dosing of FAZ053, Tmax ranged from 1.5 to 1.8 h across the doses evaluated at both cycles.

Immunogenicity

FAZ053 monotherapy

As many as 80 out of 93 (86.0%) patients treated with FAZ053 monotherapy contributed blood samples to enable the detection of the emergence of antibodies against FAZ053 during treatment. Of the 74 patients who showed no antibody against FAZ053 at baseline, 15 (20.3%) developed antibodies against FAZ053 during treatment. The titer of six patients who harbored antibodies against FAZ053 at baseline remained stable during the study.

FAZ053 and spartalizumab combination

As many as 53 out of 61 (86.9%) patients treated with combination therapy contributed blood samples to enable detection of the emergence of antibodies against FAZ053 and spartalizumab during treatment. Of the 52 patients who showed no antibody against FAZ053 and spartalizumab at baseline, 24 (46.2%) and 6 (11.5%) patients, respectively, developed antibodies against FAZ053 and spartalizumab during treatment. The titer of one patient who harbored antibodies against FAZ053 at baseline increased during the study.

Pharmacodynamics

Total soluble PD-L1 concentrations (sPD-L1; equals free sPD-L1 + sPD-L1-FAZ053 complexes), as measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay-based method, demonstrated high inter-individual variability across the cohorts, although the concentration increased when FAZ053 ≥240 mg Q3W was administered, suggestive of the binding of sPD-L1 to FAZ053. Approximately 84% of the samples collected at baseline fell below the limit of quantitation of 0.25 ng/ml. Samples collected from patients receiving 800 mg Q3W showed more sustained total sPD-L1, whereas those from patients receiving 800 mg Q6W showed a decline in target total sPD-L1 during cycle 2. Doses of ≥800 mg Q3W or ≥1600 mg Q6W appeared to demonstrate a consistent increase in total sPD-L1 throughout the dosing interval (Supplementary Figure S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105051).

Antitumor activity

Dose escalation

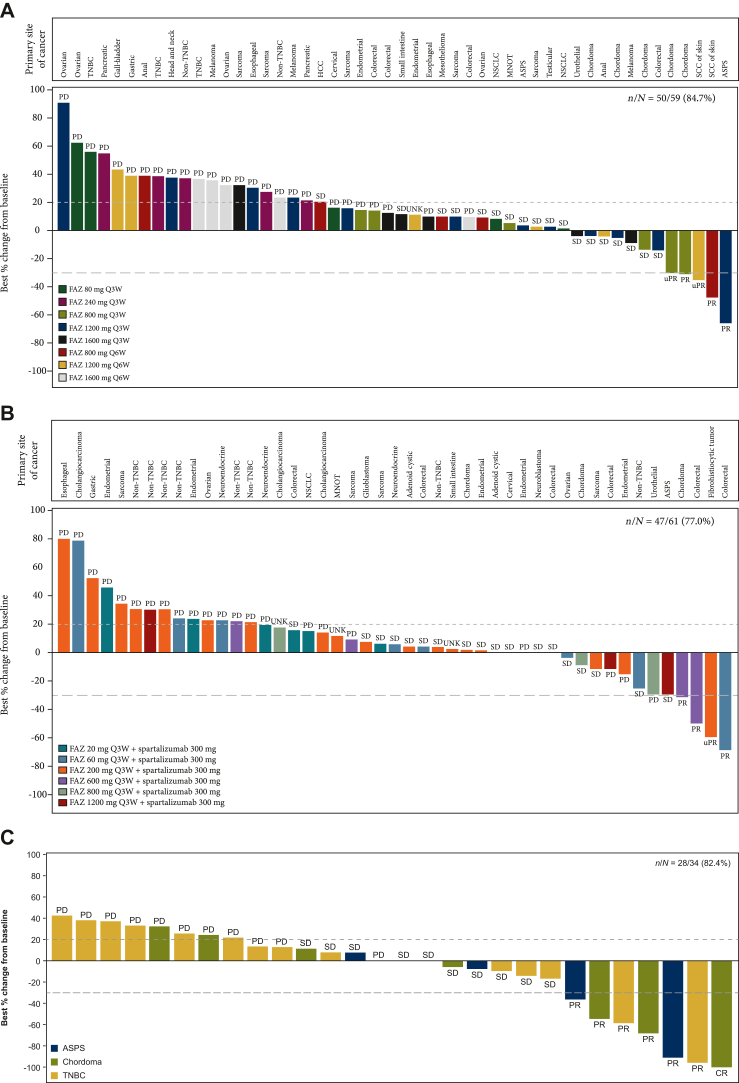

For the 59 patients receiving FAZ053 monotherapy in dose escalation, the overall response rate (ORR) was 5.1% [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.1% to 14.1%] based on investigator assessment. The disease control rate (DCR) was 40.7% (95% CI 28.1% to 54.3%). Patients with advanced alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS) and chordoma attained ORRs of 50% (n = 2; 95% CI 1.3% to 98.7%) and 20% (n = 5; 95% CI 0.5% to 71.6%), respectively. For the 61 patients receiving combination therapy, the ORR was 4.9% (95% CI 1.0% to 13.7%), including in two patients with advanced colon cancer. The DCR was 39.3% (95% CI 27.1% to 52.7%). An RDE of 1200 mg Q3W was declared based on the overall safety profile, tolerability, PK characteristics, and antitumor activity observed (Table 4; Figure 1A and B).

Table 4.

Best overall response per RECIST version 1.1 based on investigator assessment

| Dose escalation |

Dose expansion |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAZ053 monotherapy (n = 59), n (%) | FAZ053 + spartalizumab (n = 61), n (%) | FAZ053 1200 mg Q3W (n = 4) |

FAZ053 1200 mg Q3W (n = 10) |

FAZ053 1200 mg Q3W (n = 20) |

|

| Primary tumor | Mixeda | Mixeda | ASPS | Chordoma | TNBC |

| Patients with measurable disease at baseline, n (%) | 56 (94.9) | 57 (93.4) | 4 (100) | 10 (100) | 19 (95.0) |

| Duration of exposure (days), median (range) | 91.0 (21-1556) | 85.0 (11-1421) | 739.5 (255-1226) | 386.5 (108-1254) | 51.0 (20-1345) |

| Duration of exposure of >126 days, n (%) | 20 (33.9) | 23 (37.7) | 4 (100) | 6 (60.0) | 5 (25.0) |

| Best overall response, n (%) | |||||

| CR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0) |

| PR | 3 (5.1) | 3 (4.9) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (20.0) | 2 (10.0) |

| SD | 20 (33.9) | 19 (31.1) | 2 (50.0) | 4 (40.0) | 4 (20.0) |

| Unconfirmed PR (uPR) | 2 (3.4) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| PD | 29 (49.2) | 25 (41.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (20.0) | 11 (55.0) |

| Non-CR/Non-PD (NCR/NPD) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown | 6 (10.2) | 12 (19.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (10.0) | 3 (15.0) |

| Overall response rate (CR + PR) (95% CI) | 3 (5.1) (1.1-14.1) | 3 (4.9) (1.0-13.7) | 2 (50.0) (6.8-93.2) | 3 (30.0) (6.7-65.2) | 2 (10.0) (1.2-31.7) |

| Disease control rate (CR + PR + SD + NCR + NPDa) (95% CI) | 24 (40.7) (28.1-54.3) | 24 (39.3) (27.1-52.7) | 4 (100.0) (39.8-100) | 7 (70.0) (34.8-93.3) | 6 (30.0) (11.9-54.3) |

ASPS, alveolar soft part sarcoma; CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; NCR, noncomplete response; NPD, nonprogressive disease; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; Q3W, every 3 weeks; SD, stable disease; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer; uPR, unconfirmed partial response.

Refer to Supplementary Table S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105051, for a complete list of primary tumors treated in this study.

Figure 1.

Best percentage change from baseline in the sum of the longest diameters by primary cancer site and study treatment dose across FAZ053 monotherapy, FAZ053 combination with spartalizumab Q3W, and FAZ053 1200 mg Q3W dose-expansion (assessed per RECIST v1.1 by investigators). (A) Best percentage change from baseline in the sum of the longest diameters according to the primary site of cancer and study treatment dose in patients receiving FAZ053 monotherapy in dose escalation, as assessed by investigators per RECIST version 1.1. (B) Best percentage change from baseline in the sum of the longest diameters according to the primary site of cancer and the study treatment dose in patients receiving FAZ053 in combination with spartalizumab every 3 weeks (Q3W) in dose escalation, as assessed by investigators per RECIST version 1.1. uPRs are reported as SDs in Table 3, per RECIST. (C) Best percentage change from baseline in the sum of the longest diameters according to the primary site of cancer and study treatment dose in patients treated with FAZ053 1200 mg Q3W in dose expansion, as assessed by investigators per RECIST version 1.1. ASPS, alveolar soft part sarcoma; CR, complete response; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MNOT, malignant neoplasm of thymus; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SD, stable disease; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer; UNK, unknown; uPR, unconfirmed partial response.

Dose expansion

The dose-expansion part further evaluated patients with advanced ASPS, chordoma, and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) receiving FAZ053 monotherapy at the RDE following the completion of dose escalation. For the four patients with ASPS, the ORR was 50% (95% CI 6.8% to 93.2%) and the DCR was 100% (95% CI 39.8% to 100%). For the 10 patients with chordoma, the ORR was 30% (95% CI 6.7% to 65.2%), including one patient who attained a complete response, and the DCR was 70% (95% CI 34.8% to 93.3%). For the 20 patients with TNBC, the ORR was 10% (95% CI 1.2% to 31.7%) and the DCR was 30% (95% CI 11.9% to 54.3%). The median (range) DOE was 739.5 days (range 255-1226 days), 386.5 days (range 108-1254 days), and 51 days (range 20-1345), respectively, for patients with ASPS, chordoma, and TNBC (Table 4; Figure 1C and Supplementary Figure S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105051).

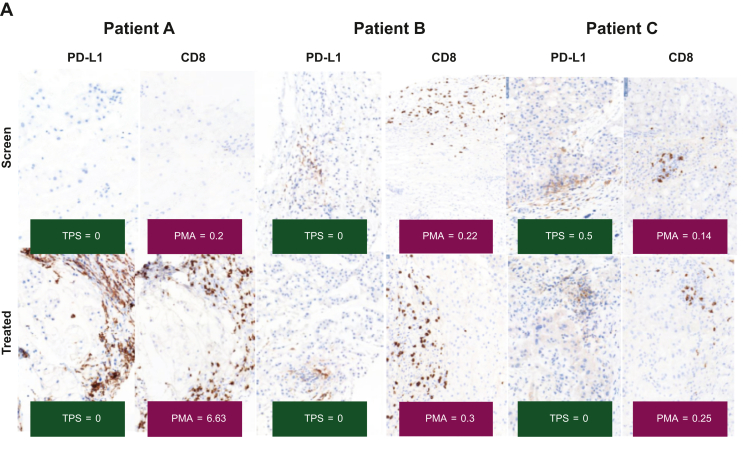

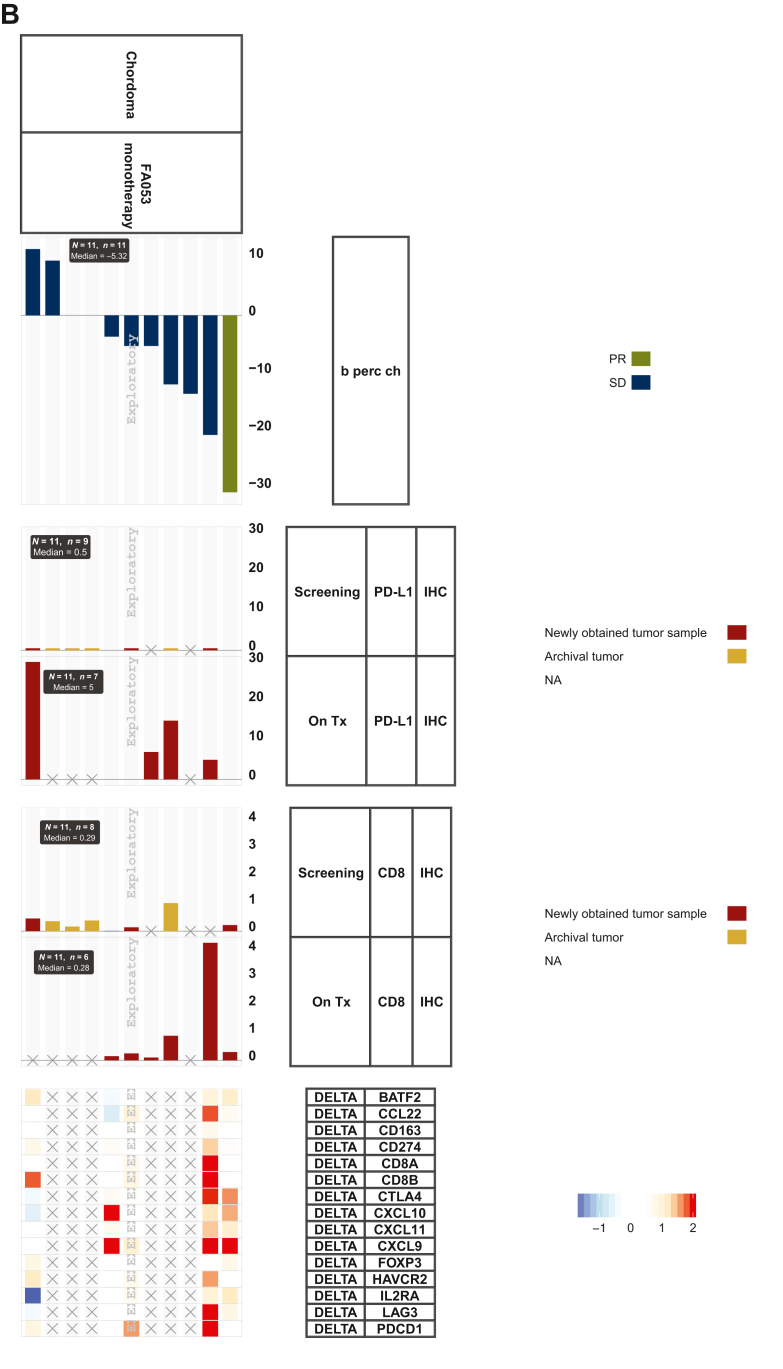

Biomarker analysis

Chordoma tumor biopsy samples showed minimal infiltration and tumor PD-L1 expression overall. Tumor proportion score (TPS) scores for PD-L1 and percent marker area for CD8 were low at baseline and in on-treatment biopsies. However, increases in CD8+ infiltrates at the periphery of tumor nests and in PD-L1 stromal staining were observed in on-treatment samples (Figure 2A). Gene expression analyses demonstrated that FAZ053 treatment resulted in upregulated expression of the immune genes CXCL9, CXCL10, and PD-1 and other immune gene signatures in paired chordoma biopsies (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Analysis of chordoma tumor samples. (A) Chordoma tumors show minimal infiltration and tumor programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression. Patient A’s best overall response (BOR) was stable disease [SD; FAZ053 200 mg + spartalizumab 300 mg every 3 weeks (Q3W)]; patient B’s BOR was partial response (FAZ053 800 mg Q3W); patient C’s BOR was SD [FAZ053 1200 mg Q3W]. PMA, percent marker area; TPS, tumor proportion score. (B) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and RNA-sequencing data derived from tumor samples of patients with chordoma. Tx, treatment.

Both IHC and gene expression analyses demonstrated that most biopsy samples exhibited characteristics of an ‘immune-cold’ tumor microenvironment across all indications. IHC analysis of baseline biopsy samples collected from 76 (63.3%) patients treated during dose escalation showed that only 5 of them had a TPS of ≥50% and that samples collected from 7 of 68 patients demonstrated CD8 staining at levels of ≥2% (Supplementary Figure S5, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105051). Patients treated in dose expansion whose baseline tumor biopsy samples exhibited higher levels of PD-L1 (TPS of >25%) tended to show a better response to FAZ053 monotherapy (Supplementary Figure S6, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105051).

Discussion

This study showed that FAZ053 monotherapy was well tolerated across all dose levels evaluated. The observed PK characteristics of FAZ053 were dose proportional and consistent with those reported in prior IgG4 ICI studies.16,17 As FAZ053 did not show a clear dose relationship with safety or antitumor activity, exploratory modeling was carried out, which predicted >99% PD-L1 receptor occupancy in the tumor. Moreover, a terminal half-life of ∼20.6 days at 1200 mg supported Q3W dosing, and doses of FAZ053 ≥800 mg Q3W resulted in sustained increases in total sPD-L1. Of note, this RDE and dosing regimen are similar to those for the PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab.18

FAZ053 monotherapy demonstrated durable disease control in diverse tumors, including ASPS and chordoma, that are not considered ‘immune hot’, which are characterized by a tumor microenvironment rich in TILs, PD-L1 overexpression, genomic instability, and preexisting antitumor immune responses.19 ASPS originates from a variety of soft tissues, whereas chordoma is classified as a bone sarcoma derived from notochordal remnants of the neuroaxis. ASPS and chordoma are indolent tumors, with a reported incidence of <1/1 000 000 persons per year globally,20 thus fulfilling the definition of ultra-rare sarcomas.21 Most patients with ASPS and chordoma have a local diagnosis that is managed with surgical resection and/or radiotherapy. However, disease relapse and metastases occur in up to 50% of patients.22,23 Because of the rarity of ASPS and chordoma, these tumors have historically been underrepresented in the clinical development of novel agents.

An open-label phase II study that evaluated atezolizumab for the treatment of advanced ASPS in 52 adult and pediatric patients reported an ORR of 37%, a median duration of response of 24.7 months, and a stable disease rate of 54%. Most responses occurred within 6 months of treatment initiation, although partial responses attained in excess of 12 months following treatment initiation were seen. Not all the baseline tumor samples of eventual responders harbored the molecular and cellular characteristics predictive of response to ICIs, as tumor samples of some responders began to show evidence of conversion to a responsive phenotype during atezolizumab therapy.24 These findings formed the basis of the United States Food and Drug Administration’s approval of atezolizumab for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic ASPS.18 To date, there is no approved targeted therapy for advanced chordoma. A systematic review of clinical trials conducted from 1999 to 2022 on advanced chordoma identified 35 interventional studies, of which 14 (27.5%) were completed and one has a study report. Most of the systematic interventional studies in chordoma were early-phase trials that evaluated ICIs and small-molecule inhibitors targeting cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 (CDK4/6), enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), and tyrosine kinase.25 Chordoma could be considered an inherently poor candidate for immunotherapy given the abundance of extracellular matrix and low mutational burden. Mathios et al.26 demonstrated that, although PD-L1 was not expressed at significant levels in chordoma cells, PD-L1 expression was observed on tumor-infiltrating macrophages and TILs. It remains unclear how the PD-1 pathway contributes to the immunosuppressive microenvironment of chordoma. In the chordoma subgroup of the phase II AcSé pembrolizumab study, 34 patients were treated, of whom 4 (12%) attained a partial response and 26 (71%) experienced stable disease. An analysis of immune gene biomarkers suggested that most chordomas were ‘immune cold’ at baseline, with on-treatment immune gene upregulation.27 Despite fewer patients being treated, the clinical activity observed in patients with ASPS and chordoma receiving FAZ053 monotherapy in this study is consistent with that reported previously.28 While caution must be exercised when interpreting data from different studies, these findings add to the body of emerging evidence suggesting that rare, phenotypically ‘immune cold’ sarcomas such as ASPS and chordoma are capable of becoming responsive to ICI treatment.

The presence of tumor-infiltrating immune cells has been shown to have prognostic significance in TNBC in several studies because their presence is predictive of responsiveness to ICI therapy.29 In the randomized phase III study KEYNOTE-119, pembrolizumab monotherapy demonstrated an ORR of 9.6% in patients with chemotherapy-refractory TNBC. This finding is similar to the antitumor activity observed with FAZ053 monotherapy in the present study, with an ORR of 10% (95% CI 1.2% to 31.7%) and a DCR of 30% (95% CI 11.9% to 54.3%). While pembrolizumab monotherapy did not significantly improve overall survival (OS) as a second- or third-line treatment for metastatic TNBC when compared with chemotherapy selected by investigators, pembrolizumab monotherapy resulted in less high-grade AEs, and higher PD-L1 expression was associated with longer median OS. The greatest benefit was seen in a post hoc analysis of patients with a combined positive score of ≥20.30

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first clinical evaluation of an anti-PD-1 mAb in combination with an anti-PD-L1 mAb for the treatment of advanced malignancies. During dose escalation, proportionally more study drug-related AEs were observed in patients receiving combination therapy (Supplementary Figure S7, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105051). Most of these AEs were manageable and did not require study drug interruption or corticosteroid therapy. The hypothesis that simultaneous inhibition of PD-1 and PD-L1 may provide synergistic antitumor activity was not supported by the efficacy observed in patients receiving combination therapy in dose escalation. Specifically, patients who received combination therapy experienced similar ORRs, quality, and duration of response to those receiving FAZ053 monotherapy. Proportionally more patients who received combination therapy developed antibodies against FAZ053 during the treatment compared with patients who received FAZ053 monotherapy, which might have had a negative impact on the efficacy of combination therapy. Consequently, combination therapy was not further evaluated in dose expansion.

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the safety and tolerability of FAZ053 with and without spartalizumab. The inclusion of very rare sarcomas without prespecified sample sizes resulted in the treatment of relatively fewer patients with ASPS and chordoma, which was compounded by the lack of control groups, ultimately limiting the statistical robustness of our findings. However, given the indolent nature of ASPS and chordoma, typical RECIST endpoints may not be the most appropriate outcomes to assess the biological effect of novel agents. As expounded by Van Glabbeke et al.,31 progression-free survival rates at predefined time points could be adopted for studies that assess novel agents for the treatment of soft-tissue sarcomas.

Based on the early efficacy signal observed in patients with advanced chordoma treated with FAZ053 in this study and with pembrolizumab in a separate study, further evaluation with robust predefined correlative science is warranted. Patient selection based on pretreatment PD-1/PD-L1 expression status may exclude patients with chordoma who have the potential to respond to ICI therapy. Given the rarity of chordoma, collaborative efforts are required between academia and the pharmaceutical industry in the development of novel agents, particularly for this condition.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients who participated in this clinical trial, as well as their families. The authors thank the staff at each participating institution that assisted with the study. We thank Jennifer Wheler, MD, and Andrew Stein, PhD, for their significant contributions to the design and conduct of this study. Additionally, the authors extend their gratitude to Masaki Akiyama, Allison Charles, Helen Evans, Kimberly Krueger, Mariya Mazlina, Liza Morgan, Carolyn McGarry, Padma Yerramilli-Rao, and Sarah Slone for their contribution to the study and Subham Das, Dr Anamika Gulati, PhD, and Haritha Nekkanti of Novartis Healthcare Pvt Ltd, Hyderabad, India, for providing medical writing and editorial assistance for this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Novartis Pharmaceuticals was involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and the writing of the manuscript.

Disclosure

FJ is currently an employee with ownership interests (stocks and options) in Monte Rosa Therapeutics. DSPT has received consulting fees and honoraria from AstraZeneca, Roche, Bayer, MSD, Merck Serono, Tessa Therapeutics, and Genmab, as well as research funding from AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Karyopharm Therapeutics. JML has received lecture fees from Astellas Pharma, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, and Roche; advisory fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Highlight Therapeutics, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Roche, Sanofi, and Trialing Health; and travel grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Roche, and Ipsen. ST has received lecture fees from MSD, AstraZeneca, Chugai, Bayer, Ono, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Eisai, as well as grants from MSD, AstraZeneca, Chugai, Bayer, Ono, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Taiho, Novartis, and Daiichi-Sankyo. RG has received honoraria from Roche, MSD, Merck, Medison, Janssen, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Takeda, Novartis, and Gilead; advisory/consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Roche, Bayer, MSD, Oncotest, Pfizer, Neopharm Group, Astellas, Eisai, and J&J Innovative Medicine; has a leadership role and ownership interests in Pyxis; and has received travel, accommodations, and expenses from Roche and Merck. AG received support from Novartis for the present manuscript. AR has received research support from 23andMe, Abbisko, AbbVie, Adaptimmune, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BioNTech, Blueprint Medicines, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cogent Biosciences, Daiichi Sankyo, Deciphera, Frontier Biopharma, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Intensity Therapeutics, Iterion Therapeutics, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Kelun Therapeutics, MedImmune, Medison, Merck, Neoleukin, Novartis, Pfizer, Polaris, Roche/Genentech, Rain Therapeutics, and Symphogen; has provided expert testimony or served on advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Medison, Clinical Research Malaysia, and Alexion; has served on a DSMB for Inhibrx; and has received honoraria from Medison and UpToDate. XC, RR, and KS are former employees of Novartis. RK, CL, JM, and SS are employees of Novartis. PLB has received research funding from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Bicara, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Gilead, Merck, LegoChem, Lilly, Medicenna, Novartis, Sanofi, Seattle Genetics, Servier, Takeda, and Zymeworks, and has provided uncompensated advisory services for Janssen, Lilly, Repare Therapeutics, Roche, Seattle Genetics, and Zymeworks.

Supplementary data

Material

References

- 1.Protti M.P., De Monte L., Di Lullo G. Tumor antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in cancer immunity: from antigen identification to tumor prognosis and development of therapeutic strategies. Tissue Antigens. 2014;83(4):237–246. doi: 10.1111/tan.12329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong H., Strome S.E., Salomao D.R., et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med. 2002;8(8):793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keir M.E., Butte M.J., Freeman G.J., Sharpe A.H. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamazaki T., Akiba H., Iwai H., et al. Expression of programmed death 1 ligands by murine T cells and APC. J Immunol. 2002;169(10):5538–5545. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hino R., Kabashima K., Kato Y., et al. Tumor cell expression of programmed cell death-1 ligand 1 is a prognostic factor for malignant melanoma. Cancer. 2010;116(7):1757–1766. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taube J.M., Anders R.A., Young G.D., et al. Colocalization of inflammatory response with B7-h1 expression in human melanocytic lesions supports an adaptive resistance mechanism of immune escape. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(127) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carretero-González A., Lora D., Ghanem I., et al. Analysis of response rate with ANTI PD1/PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies in advanced solid tumors: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Oncotarget. 2018;9(9):8706–8715. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun L., Zhang L., Yu J., et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors for the treatment of advanced or metastatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):2083. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58674-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butte M.J., Keir M.E., Phamduy T.B., Sharpe A.H., Freeman G.J. Programmed death-1 ligand 1 interacts specifically with the B7-1 costimulatory molecule to inhibit T cell responses. Immunity. 2007;27(1):111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishimura C.D., Pulanco M.C., Cui W., Lu L., Zang X. PD-L1 and B7-1 Cis-interaction: new mechanisms in immune checkpoints and immunotherapies. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27(3):207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2020.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novartis data on file.

- 12.Eisenhauer E.A., Therasse P., Bogaerts J., et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolchok J.D., Hoos A., O’Day S., et al. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteria. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(23):7412–7420. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neuenschwander B., Capkun-Niggli G., Branson M., Spiegelhalter D.J. Summarizing historical information on controls in clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2010;7(1):5–18. doi: 10.1177/1740774509356002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neuenschwander B., Matano A., Tang Z., Roychoudhury S., Wandel S., Bailey S. In: Statistical Methods in Drug Combination Studies. Zhao W., Yang H., editors. Taylor & Francis; 2014. A Bayesian industry approach to phase I combination trials in oncology; p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- 16.KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) injection, for intravenous use. Initial U.S. Approval. 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/125514s162lbl.pdf Available at.

- 17.OPDIVO® (nivolumab) injection, for intravenous use. Initial U.S. Approval. 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/125554s128lbl.pdf Available at.

- 18.TECENTRIQ® (atezolizumab) injection, for intravenous use. Initial U.S. Approval. 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/761034s043lbl.pdf Available at.

- 19.Galon J., Bruni D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18(3):197–218. doi: 10.1038/s41573-018-0007-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salisbury J.R. The pathology of the human notochord. J Pathol. 1993;171(4):253–255. doi: 10.1002/path.1711710404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stacchiotti S., Frezza A.M., Blay J.Y., et al. Ultra-rare sarcomas: a consensus paper from the Connective Tissue Oncology Society community of experts on the incidence threshold and the list of entities. Cancer. 2021;127(16):2934–2942. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdulrauf S.I. Decision-making process for the treatment of intracranial chordomas. World Neurosurg. 2014;82(5):612–613. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2013.07.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh P.C., Xu R., Sciubba D.M., et al. Long-term clinical outcomes following en bloc resections for sacral chordomas and chondrosarcomas: a series of twenty consecutive patients. Spine. 2009;34(20):2233–2239. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b61b90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen A.P., Sharon E., O’Sullivan-Coyne G., et al. Atezolizumab for advanced alveolar soft part sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(10):911–921. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2303383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen S., Ulloa R., Soffer J., et al. Chordoma: a comprehensive systematic review of clinical trials. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15(24):5800. doi: 10.3390/cancers15245800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathios D., Ruzevick J., Jackson C.M., et al. PD-1, PD-L1, PD-L2 expression in the chordoma microenvironment. J Neurooncol. 2015;121(2):251–259. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1637-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blay J.Y., Chevret S., Le Cesne A., et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with rare and ultra-rare sarcomas (AcSé Pembrolizumab): analysis of a subgroup from a non-randomised, open-label, phase 2, basket trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24(8):892–902. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Migliorini D., Mach N., Aguiar D., et al. First report of clinical responses to immunotherapy in 3 relapsing cases of chordoma after failure of standard therapies. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6(8) doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1338235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Debien V., De Caluwé A., Wang X., et al. Immunotherapy in breast cancer: an overview of current strategies and perspectives. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2023;9(1):7. doi: 10.1038/s41523-023-00508-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winer E.P., Lipatov O., Im S.A., et al. Pembrolizumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-119): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(4):499–511. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30754-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Glabbeke M., Verweij J., Judson I., Nielsen O.S. Progression-free rate as the principal end-point for phase II trials in soft-tissue sarcomas. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38(4):543–549. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00398-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Material