Abstract

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a disease that affects the vision of elderly individuals worldwide. Although current therapeutics have shown effectiveness against AMD, some patients may remain unresponsive and continue to experience disease progression. Therefore, in-depth knowledge of the mechanism underlying AMD pathogenesis is urgently required to identify potential drug targets for AMD treatment. Recently, studies have suggested that dysfunction of mitochondria can lead to the aggregation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and activation of the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)/stimulator of interferon genes (STING) innate immunity pathways, ultimately resulting in sterile inflammation and cell death in various cells, such as cardiomyocytes and macrophages. Therefore, combining strategies targeting mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammatory mediators may hold great potential in facilitating AMD management. Notably, emerging evidence indicates that natural products targeting mitochondrial quality control (MQC) and the cGAS/STING innate immunity pathways exhibit promise in treating AMD. Here, we summarize phytochemicals that could directly or indirectly influence the MQC and the cGAS/STING innate immunity pathways, as well as their interconnected mediators, which have the potential to mitigate oxidative stress and suppress excessive inflammatory responses, thereby hoping to offer new insights into therapeutic interventions for AMD treatment.

Keywords: Age-related macular degeneration, Phytochemicals, Mitochondrial quality control, Mitophagy, Mitochondrial biogenesis, cGAS/STING

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

AMD is a common vision disease which lacks therapeutic strategy.

-

•

Mitochondrial dysfunction and hyperactivation of cGAS/STING pathways are entwisted and involved in AMD pathological process.

-

•

Targeting inflammatory mediators and mitochondrial dysfunction could be effective in managing AMD.

-

•

Natural products targeting MQC and cGAS/STING pathways hold great potential in AMD treatment.

1. Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a multifactorial, chronic, and progressive neurodegenerative disorder that can be affected by many intrinsic and extrinsic stimuli. These include aging, genetic predisposition, epigenetic inheritance, gender, systemic health, and several environmental risk factors, such as smoking and phototoxic exposure [1]. These risk factors can increase oxidative stress or inflammation, leading to retinopathy. The typical manifestations of early AMD include the presence of drusen situated between the Bruch's membrane and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), resulting in RPE degeneration. The advanced stages of AMD can be categorized into two subtypes: dry (atrophic) or wet (neovascular). Atrophic AMD is distinguished by geographic atrophy (GA), whereas neovascular AMD is characterized by choroidal neovascularization (CNV). Both forms ultimately result in compromised central vision or potential blindness in elderly individuals.

The metabolic rate of the retina is notably higher compared to other organs in the body, rendering it more susceptible to continuous photooxidative damage and internal/external stressors [2]. The RPE plays a pivotal role in nutrient transport, supporting photoreceptor cells and participating in the visual cycle. As a result, mitochondria are abundantly present in the RPE and serve as their main energy source. Additionally, both photoreceptors and Müller cells within the outer retina exhibit a high density of mitochondria. Clinical and experimental research indicates that mitochondrial impairment or dysfunction significantly contributes to RPE dysfunction in the pathogenesis of AMD [3]. Therefore, various mechanisms are employed to protect against stress and to maintain the functionality and homeostasis of mitochondria, including DNA repair, antioxidant defense, and mitochondrial quality control (MQC). Mitophagy, mitochondrial dynamics, and mitochondrial biogenesis are important components of MQC, which are crucial for regulating reactive oxygen species (ROS) [4], preserving mitochondrial integrity, and eliminating impaired mitochondria to prevent cell demise or tissue impairment. Hence, gaining a better understanding of MQC in human RPE could be therapeutically important for the prevention and treatment of AMD. Mitochondrial dysfunction and MQC dysregulation can activate damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), thereby amplifying inflammatory signals and precipitating excessive inflammation and immune responses [5]. These processes have been implicated in age-related neurological disorders. A crucial regulator of age-related inflammation is the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)/stimulator of interferon genes (STING) immune pathways [6], which is intricately linked to MQC. Consequently, exploring the link between MQC and the cGAS/STING pathway could provide novel insights into the mechanisms underlying AMD and other age-related conditions.

Dry AMD Currently has no effective treatments, and the therapeutic options for wet AMD are primarily confined to anti-angiogenesis agents [1]. Although anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents are used in the treatment of wet AMD, clinical outcomes are often suboptimal. These agents are unable to fully reverse choroidal neovascular membranes or the progression of atrophy [1]. Phytochemicals derived from natural products demonstrate significant potential in the treatment of age-related neurological disorders modulating mitochondrial dysfunction and chronic inflammation, either directly or indirectly [7]. These compounds exhibit a relatively satisfactory therapeutic effect with minimal side effects. Phytochemicals may, therefore, provide an encouraging resource to develop AMD prevention and treatment strategies. This review provides an overview of the protective roles of natural products against AMD, focusing on their regulation of the MQC and cGAS/STING innate immunity pathways.

2. MQC in the progression of AMD

2.1. Mitochondria dysfunction in the retina

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles integral to a multitude of cellular functions, including ATP production, metabolic regulation, calcium and redox balance maintenance. They are also vitally involved in cellular metabolism, necrotic cell death, programmed apoptosis, and overall cell survival. Moreover, the ROS generated during oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) is physiologically crucial in cellular processes [8]. Nevertheless, elevated ROS levels can inflict damage on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), lipids, and protein, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of numerous human diseases, including those associated with aging [9]. Furthermore, there is an increase in oxygen tension, metabolic rate, and continuous ROS production in the macula during aging, which results in oxidative stress [10]. mtDNA is particularly susceptible to oxidative damage due to its close proximity to the mitochondrial electron transport chain (mtETC) [11]. Like the nucleus, mtDNA damage can restrain the replication, transcription, and expression of mitochondrial genes. If the damage cannot be repaired properly, malfunctions of mtETC may occur. Mitochondrial structures would undergo disruption, and mutations can accumulate in mtDNA during aging. For instance, the accumulation of the ΔmtDNA 4977 deletion has been observed in aging human RPE and neural retina, but not in fetal tissue [12]. Furthermore, studies have revealed that while regular age-related mtDNA deletions are common, extensive damage to mtDNA is caused by AMD [13]. According to these findings, as we age, the level of mtDNA damage escalates, and in the case of AMD, it becomes even more extensive. Several proteins are activated to repair specific types of DNA damage; however, their efficacy decreases with age. Mutations in mtDNA contribute to the generation of defective protein subunits in OXPHOS, leading to electron leak, ROS production, and an energy crisis in the retina eventually [14].

The MQC system is responsible for ensuring the health of mitochondria by initiating molecular and organelle quality control mechanisms. To maintain protein balance, for example, mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) is well-suited. Mitochondrial chaperones and proteases are activated by UPRmt, which helps refold or break down damaged proteins. Additionally, it collaborates with other processes, such as DNA repair machinery and the antioxidant defense system, to restore mitochondrial balance. In cases of UPRmt and DNA repair mechanism failure, cellular processes such as mitochondrial dynamics, mitophagy, and mitochondrial biogenesis can be activated to keep mitochondrial homeostasis. However, if these mechanisms are insufficient in controlling the damage, cell death may occur (Fig. 1). Therefore, it is crucial to investigate the role of MQC in protecting against mitochondrial dysfunction in AMD.

Fig. 1.

Mitochondrial quality control (MQC) in age-related macular degeneration (AMD). In response to stimuli, multiple molecular and organelle quality control mechanisms are implemented to maintain cell homeostasis under normal physiological conditions. In the early stages of AMD, it is subjected to physiological or moderate levels of oxidative stress. Mitochondrial chaperones and proteases are activated by mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt), which helps refold or break down damaged proteins. Additionally, UPRmt collaborates with other processes, such as DNA repair machinery and the antioxidant defense system, to restore mitochondrial balance. In cases of UPRmt and DNA repair mechanism failure, cellular processes such as mitochondrial dynamics, mitophagy, and mitochondrial biogenesis can be activated to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis. Mitofusin 1 (MFN1), mitofusin 2 (MFN2), and optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) to alleviate stress by mixing the damaged and healthy mitochondria. In addition, further damage can trigger dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1)-dependent fission and initiate mitophagy to clear damaged mitochondria simultaneously. The presence of drusen in the retina suggests a failure in autophagy or mitophagy, leading to choroidal neovascularization or atrophy of the retina. The reduced number of mitochondria is replenished by mitochondrial biogenesis. However, if all these mechanisms are insufficient for controlling the damage, cell death may occur. ROS: reactive oxygen species; DAMPs: damage-associated molecular patterns; MOMP: mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization; MDVs: mitochondrial-derived vesicles.

2.2. Mitophagy and mitochondrial-derived vesicles (MDVs)

Generally, autophagy degrades unwanted or damaged molecules and organelles via target-specific lysosomes, recycling them for cellular use. Three types of autophagy have been identified: microautophagy, chaperone-mediated autophagy, and macroautophagy, which is the most studied [15]. Decreased autophagic activity has been strongly linked to AMD, and the drusen in the retina suggests a failure in the lysosome/autophagy pathway [16]. Along with the in-depth study of autophagy, several selective autophagy has been observed, including mitophagy, lipophagy, glycophagy, and ribophagy [2]. Mitophagy, which selectively eliminates dysfunctional mitochondria to prevent damage from ROS, is an essential mechanism of MQC. There are four types of mitophagy: PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin-dependent (non-receptor-mediated) mitophagy (Fig. 2), receptor-mediated mitophagy (Fig. 2), lipid-mediated mitophagy, and autophagy-independent MDVs. Recently, MDVs have emerged as a novel type of mitophagy [17].

Fig. 2.

Molecular mechanisms of PTEN-induced putative kinase1 (PINK1)/Parkin-dependent and receptor-mediated pathways in mitophagy. (1) The PINK1/Parkin-dependent pathway for mitophagy (right, the upper middle). When the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is lost, PINK1 accumulates in the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) and phosphorylates Parkin at Ser65. The autophagy adaptor proteins, including sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1/p62), NDP52, Tax1-binding protein 1 (TAX1BP1), neighbor of BRCA1 gene 1 (NBR1), and optineurin (OPTN), could bind to the ubiquitin (Ub) chains and active the autophagy machinery. In outer mitochondria, the activating molecule in Beclin1-regulated autophagy protein 1 (AMBRA1) could promote the stabilization of PINK1. (2) The receptor-mediated pathway for mitophagy (right, the lower middle). Four main mitochondrial protein receptors, namely B-cell lymphoma-2 ( Bcl-2)/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa-interacting protein-3 (BNIP3), NIP3-like protein X (NIX), FUN14 domain containing 1 (FUNDC1), and activating molecule in Beclin1-regulated autophagy protein 1 (AMBRA1) (on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM)), have microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) interaction region (LIR) sequence that autophagy machinery can recognize. (3) The crosstalk of the PINK1-Parkin and receptors pathways (the left side). NIX and BNIP3 are pivotal in regulating Parkin recruitment for mitochondrial homeostasis during retina development and under hypoxia condition. BNIP3, a Parkin substrate, is ubiquitinated by Parkin to promote mitophagy. Additionally, BNIP3 stabilizes PINK1 by preventing its cleavage. Parkin can also activate BNIP3/NIX-mediated mitophagy, suggesting an interaction between the PINK1-Parkin and receptor pathways. ROS: reactive oxygen species.

2.2.1. PINK1/Parkin-regulated mitophagy

It is generally agreed that the PINK1/Parkin pathway is a vital component of the regulatory pathway of mitophagy. Typically, PINK1 is recruited and imported from the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) into the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM), where it undergoes cleavage by mitochondrial peptidases, including mitochondrial processing peptidase (MPP) and presenilin-associated rhomboid-like (PARL) protein, before ultimately being degraded by the proteasome [18]. When the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is lost, PINK1 accumulates in the OMM and phosphorylates Parkin at Ser65 [19]. The autophagy adaptor proteins: sequestosome-1 (p62/SQSTM1), NDP52, Tax1-binding protein 1 (TAX1BP1), neighbor of BRCA1 gene 1 (NBR1), and optineurin (OPTN) [20,21], could bind to the ubiquitin chains and activate the autophagy machinery [22]. During PINK1/Parkin-regulated mitophagy, PINK1 functions as a mitochondrial damage sensor, Parkin serves as a signal amplifier, and ubiquitin chains act as signal transmitters.

Despite the lack of neuroretinal changes or mitophagy alterations in Pink1−/− mice [23], similarities have been observed with human AMD patients in terms of disrupted mitochondrial homeostasis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in RPE [24]. Additionally, mice with Becn1+/− and Park2 −/− showed greater sensitivity to damage from light despite having no obvious retinal changes under basal conditions [25]. Notably, in outer mitochondria, the activating molecule in Beclin-1 (BECN1)-regulated autophagy protein 1 (AMBRA1) could promote the stabilization of PINK1 [26]. Mutant mice with AMBRA1 haploinsufficiency exhibited accelerated retinal degeneration characterized by photoreceptor loss, impaired vision, and the accumulation of inflammatory factors [27]. The reduction in PINK1 levels in the perifoveal region of AMD patients in the early stages [24] suggested mitophagy insufficiency. Moreover, rapamycin (an autophagy agonist) that inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) has been demonstrated to induce mitophagy in AMD patients’ RPE cells, thereby facilitating the removal of damaged mitochondria and improving mitochondrial function [28] (Table 1). Additionally, rapamycin has been reported to elevate the levels of PINK1, Parkin, and BECN1, thereby promoting anti-aging effects on cells [29].

Table 1.

The effects of chemical compounds on mitochondrial quality control (MQC) and/or cyclic GMP-AMP synthase/stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS/STING) pathway in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) models.

| Agent | Mechanism | Cell types affected or animal models | Administration | Findings | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapamycin | LC3-II↑ | RPE cells from AMD pateints | 100 nM for 16–48 h | Mitochondrial function in RPE cells↑ | [28] |

| Bevacizumab | HIF-1α↑ BNIP3, FUNDC1↑ |

OIR model mice | 1 μL (0.625 mg/mL), IVI | ROS production↓ Enhance the safety of anti-VEGF therapy |

[34] |

| HIF-1α↑ LC3-II/LC3-I↑ p62↓ |

661W photoreceptor cell line | Incubated with 0.625 mg/mL | Mitophagy-related proteins↑ Mitophagosome formation↑ |

||

| Ophthalmology-Müller cell line | |||||

| Human vascular endothelial cells | |||||

| ZYAN1 | HIF-1α↑ BNIP3, FUNDC1↑ |

NaIO3-treated mouse model | 3 μL (3.57 ng/μL), IVI | Retinal lesions↓ The shedding of membrane discs was improved. The axonal cilia structure was relatively intact. Behavior and visual function↑ |

[35] |

| Mdivi-1 | Drp1↓ Mitochondrial fission↓ |

H2O2-treated RPE-19 cells | 1, 10, 50 and 100 μM | Releasing of cytochrome C↓ Mitochondrial function↑ ROS production↓ |

[58] |

| ZLN005 | PGC-1α↑ Mitochondrial genes↑ Antioxidant enzymes↑ |

H2O2, or ox-LDL, or NaIO3-treated RPE-19 cells | 10 μM for 24 or 48 h | Rates of maximal and basal respiration and spare capacity↑ The death of ARPE-19 cell ↓ |

[67] |

| Melatonin | Mitochondria superoxide content↓ Mitochondrial mass↑ |

Nonexudative-AMD mice model | 20 mg subcutaneously implanted and replaced every 10 days | Visual functions↑ Melanin content↑ RPE65 immunoreactivity↓ |

[70] |

| Methotrexate | cGAS/STING↓ Mitigate the disruption of heterochromatin |

Sodium iodate-treated AMD mice model | 1 mg/kg for 3 days (i.p.) | Inflammatory factors↓ Atrophy and degeneration of RPE↓ |

[83] |

| H-151 | STING↓ NF-κB↓ |

H2O2-treated RPE-19 cells | 5 μM | ROS production↓ VEGF↓ |

[84] |

| JQ1 | STING↓ NF-κB↓ |

NaIO3-treated AMD mice model | 50 mg/kg (i.p.) for 3 days | Inflammation in retina↓ Photoreceptor degeneration in the injured retina↓ |

[88] |

| Nicotinamide | Preserve ΔΨm Mitochondrial oxidative metabolism↑ |

hiPSCs-RPE from AMD patients | 10 mM | Ribosomal synthesis genes (including mitochondrial) ↑ Proteins associated with drusen formation↓ Inflammatory factors↓ Complement factors↓ |

[107] |

| SS-31 | Stabilize cristae curvature mtETC↑ Bax↓and Bcl-2↑ |

H2O2-treated RPE-19 cells | 0, 0.1, 1 and 10 μM for 12 and 24 h | Apoptosis↓ Oxidative damage↓ ROS production↓ |

[109] |

The “↑” arrow means upregulation, and the “↓” arrow means downregulation.

LC3: microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; RPE: retinal pigment epithelium; HIF-1α: hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha; BNIP3: Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa-interacting protein-3; FUNDC1: FUN14 domain containing 1; OIR: oxygen-induced retinopathy; IVI: intravitreal injection; ROS: reactive oxygen species; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; p62: sequestosome-1; Mdivi-1: mitochondrial division inhibitor 1; Drp1: dynamin-related protein 1; PGC-1α: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α; ox-LDL: oxidized low-density lipoprotein; RPE: retinal pigment epithelium; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa B; ΔΨm: mitochondrial membrane potential; hiPSC: human induced pluripotent stem cells; mtETC: mitochondrial electron transport chain; BAX: Bcl-2-associated X protein; Bcl-2: B-cell lymphoma-2.

2.2.2. Receptor-mediated mitophagy

As well as PINK1/Parkin signaling, receptor-mediated mitophagy also recognizes targeted mitochondria without ubiquitination. Four main mitochondrial protein receptors, namely B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2)/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa-interacting protein-3 (BNIP3), NIP3-like protein X (NIX), FUN14 domain containing 1 (FUNDC1), and AMBRA1 (on the OMM), have microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) interaction region (LIR) sequence that autophagy machinery can recognize. In normal conditions, NIX, BNIP3, and FUNDC1 are lowly expressed, while under hypoxia, they are highly expressed. This selective mitophagic clearance during hypoxia helps prevent excessive ROS production and supports cell survival [30,31]. Additionally, The BNIP3L/NIX deficiency impacts retinal ganglion cell (RGC) differentiation and metabolism due to impaired mitophagy during development [32]. Consequently, the ubiquitin-independent receptors triggered by developmental cues may contribute to retinal development [33]. Bevacizumab, a drug known for inhibiting of VEGF, has been reported to upregulate the hypoxic cell marker hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α). Notably, bevacizumab mitigated oxidative stress in Müller cells by inducing mitophagy, activating HIF-1α and upregulating BNIP3, thereby enhancing the safety profile of treatments for retinal neovascular diseases [34] (Table 1). In addition, intravitreal injection (IVI) of ZYAN1, a novel inhibitor of prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD), enhanced the expression of HIF-1α, leading to restoration of autophagy and alleviating oxidative stress through activating BNIP3 in degenerating retina [35] (Table 1). This implies that HIF-1α can influence receptor-mediated mitophagy. The mitochondrial homeostasis of AMD patients was preserved mainly by BNIP3/NIX-mediated mitophagy due to diminished levels of PINK1 [36], suggesting that BNIP3/NIX may serve as a compensatory mechanism distinct from PINK1/Parkin in AMD. Furthermore, previous research has indicated that NIX and BNIP3 were involved in regulating PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis through recruiting Parkin [37]. As a substrate of Parkin, BNIP3 undergoes ubiquitination mediated by Parkin, thereby promoting mitophagy [38]. Moreover, BNIP3 contributes to the stabilization of PINK1 by preventing its proteolytic cleavage [39]. Parkin can also activate BNIP3/NIX-mediated mitophagy [40], indicating a potential interaction between the PINK1-Parkin pathway and the receptors pathway (Fig. 2).

2.2.3. MDVs

The production of MDVs is a mitochondrial membrane-like protrusion that transports selected mitochondrial cargo to target organelles. Currently, MDVs are being considered one of a new pattern MQC, which is a part of mitophagy [17]. Healthy mitochondria produce MDVs, which are cargo-specific and can be distinguished from mitochondrial fragments produced by mitochondrial division [41]. The circular vesicular structures of MDVs are a monolayer formed by the OMM or a double layer containing both the IMM and OMM [42]. Specifically, MDVs biogenesis does not require mitophagy-associated proteins [41]. The formation of MDVs is an early response to various stresses and takes part in removing damaged or oxidized contents from mitochondria. The PINK1/Parkin pathway is involved in the biogenesis of MDVs caused by mitochondrial stress, while not all MDVs require them. Additionally, as well as lipopolysaccharides, other stimuli can generate MDVs that are independent of the PINK1/Parkin pathway [43]. Despite this, the formation and fusion mechanisms of different types of MDVs still wait to be further understood. MDV containing TOMM20 can be internalized into the polyvesicular body through the microautophagy pathway [43], while stress-induced PINK1/Parkin-mediated MDVs require soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) protein syntaxin 17 (STX17) for late-endosome/lysosomal delivery [44]. Besides, several studies have revealed that extracellular vesicles (EVs) can transport to neighboring cells and induce innate immunity, potentially hastening the process of cellular senescence [45]. During Parkinson's disease, self-antigens are released from mitochondria through MDVs following cellular stress [46]. This process, known as mitochondrial antigen presentation (MitAP), is inhibited by the proteins PINK1 and Parkin [46]. Moreover, increased intracellular fumarate levels have led to a restructuring of the mitochondrial network and the formation of MDVs. This process enabled mtDNA release into the cytosol, initiating immune response [47]. However, the role of MDVs in the physiological and pathological processes of the retina requires further elucidation.

Adequate mitophagy is prominent for preserving mitochondrial function, whereas inadequate mitophagy results in the buildup of dysfunctional mitochondria, heightened ROS production, and hastened cell death. Research findings indicate that the fragmentation of mitochondria in RPE cells is evident in individuals with AMD, suggesting a deficiency in mitophagy [48]. Conversely, excessive mitophagy can also be a concern, as it may result in excessive mitochondrial loss and subsequent cellular dysfunction. As a result, further research on mitophagy is necessary to clarify its role in various pathological stages and aging processes. Several studies have demonstrated that targeting mitophagy can be a therapeutic approach to treat neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson's disease [49], and renal dysfunction [50]. Therefore, targeting mitophagy may provide novel perspectives for the treatment of AMD.

2.3. Mitochondrial dynamics

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles that continuously undergo fusion and fission, facilitating cellular adaptation to environmental changes. Mitofusin 1 (MFN1) and Mitofusin 2 (MFN2) in the OMM, along with optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) in the IMM, are integral to the regulation of mitochondrial fusion. Conversely, dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) is in charge of controlling mitochondrial fission [51] (Fig. 3). Instabilities of the fusion-fission balance can arise from variations in nutrient availability and metabolic demands, resulting in mitochondrial fragmentation or hypertubulation [52]. Mitochondrial fusion is correlated with enhanced ATP production and mitigates organelle stress by facilitating the exchange of content between damaged and healthy mitochondria. Fusion inhibition is triggered by mitochondrial stress or alterations of cellular energy status, leading to impaired OXPHOS, depletion of mtDNA, and the generation of ROS [53]. Damaged mitochondria undergo asymmetric fission, resulting in the formation of both depolarized and polarized daughter mitochondria. During this process, levels of MFN1 and MFN2 are reduced to prevent further mitochondrial fusion, while OPA1 is cleaved to promote mitophagy [54]. Mitophagy helps maintain normal mitochondrial function by eliminating depolarized mitochondria. Additionally, mitophagy reduces the number of energy-producing mitochondria while simultaneously increasing the ratios of AMP/ATP and oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)/nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) to activate mitochondrial biogenesis [55]. However, excessive mitochondrial fission can lead to mitochondrial fragmentation and mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), ultimately resulting in cell death [52]. Therefore, maintaining mitochondrial function during stress necessitates a coordinated interaction between mitochondrial fission and fusion processes.

Fig. 3.

Mitochondrial dynamics (fusion and fission) and mitochondrial biogenesis. A mitochondrial fusion involves two proteins on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), mitofusin 1 (MFN1) and mitofusin 2 (MFN2), which help alleviate mitochondrial stress. OMM fusion occurs through the interaction between these proteins. Inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) fusion, however, requires the interaction between optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) and cardiolipin to occur. Mitochondrial fusion results in enhanced ATP generation which alleviates organelle stress. Damaged mitochondria undergo asymmetric fission to form depolarized and polarized daughter mitochondria. Downregulation of MFN1 and MFN2 decreases, or upregulation of cleaved OPA1 can prevent fusion, leading to initiation of either repair or mitophagy mechanisms. Mitophagy removes damaged depolarized mitochondria. Additionally, mitophagy reduces the number of energy-producing mitochondria while simultaneously increasing the ratios of AMP/ATP and oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)/nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) to activate mitochondrial biogenesis. This activates mitochondrial biogenesis through the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator (PGC)-1α interaction with nuclear respiratory factors 1 and 2 (NRF1/2) to facilitate the expression of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) for the synthesis of respiratory subunits encoded by mitochondrial DNA. However, excessive mitochondrial fission can result in mitochondrial fragmentation and mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), ultimately causing cell death. ROS: reactive oxygen species; Drp1: dynamin-related protein 1.

In most senescent cells, mitochondria are hyperfused, and the occurrence of dissociated or fragmented mitochondria is relatively infrequent [56]. Nonetheless, the specific roles of mitochondrial fusion and fission in relation to aging remain a subject of debate. Compared to young mice, aged mice displayed reduced vision [57]. Furthermore, Drp1 protein levels increased following aging, resulting in mitochondrial fragmentation and activation of mitophagy in the RPE-choroid complex, while this phenomenon was not observed in the neural retina. Pharmacological inhibition of mitochondrial fission has improved the phagocytic activity of the photoreceptor outer segment (POS) [57]. In RPE, mitochondrial dysfunction and fission may inhibit the phagocytosis of POS and slow down the visual cycle, thereby contributing to the development of AMD as an age-related defect in the retina [57]. Similarly, Fisher et al. 36>have shown that the RPE from AMD patients treated with 2-[2-[4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenyl] hydrazinylidene]-propanedinitrile (FCCP), an uncoupler for mitochondria, showed a notable decrease in three mitochondrial fusion proteins. The recovery processes for fragmented mitochondria in RPE cells were consistently delayed with impaired mitochondrial fusion due to increased stress response associated with AMD development [36]. Moreover, the decline in PINK1 protein levels in RPE cells was linked to diminished mitophagy, leading to increased mitochondrial fragmentation and subsequent cell demise [36]. Further investigations by Yako et al. [58] demonstrated that exposure of ARPE-19 cells to H2O2 resulted in mitochondrial fragmentation, a process effectively inhibited by mitochondrial division inhibitor 1 (Mdivi-1). Mdivi-1 inhibited mitochondrial cytochrome C release and enhanced mitochondrial functionality [58] (Table 1). Additionally, the dynamics of mitochondria and mitophagy are intertwined. Under low oxygen levels, phosphoglycerate mutase family member 5 (PGAM5) disrupts the interaction between FUNDC1 and OPA1, which prevents mitochondrial fusion and promotes mitochondrial fragmentation through FUNDC1-Drp1 interaction [59].

In conclusion, the inhibition of Drp1 represents a potential intervention for AMD by preventing mitochondrial fragmentation induced by elevated oxidative stress. The processes of mitochondrial fission and fusion modulate MQC by influencing both the quantity and quality of mitochondria, which are also linked to mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy. Therefore, modulating mitochondrial dynamics may be a promising pharmacological target for AMD treatment.

2.4. Mitochondrial biogenesis

In the process of mitochondrial biogenesis, existing mitochondria replicate themselves to generate new mitochondrial mass through nuclear-encoded mitochondrial gene synthesis, import, and mtDNA-encoded gene replication and expression [60]. Recently, the role of the visual cycle in advancing dry AMD has attracted significant attention [57]. Similarly, mitochondrial populations in cones may also undergo a daily cycle. During the day, mitochondria with oxidative damage undergo mitophagy, while at night, the mitochondrial biogenesis increases, thereby enhancing the number of active mitochondria [2]. Generally, mitochondrial biogenesis occurs when developmental signals and environmental stressors trigger energy demand. This process is linked with the interaction between peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator (PGC)-1α and several transcription factors, including nuclear respiratory factors (NRFs), estrogen receptor-related receptor 1 (ERR1), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPARα), and transcriptional repressor protein YY1 [61].

PGC-1 family members play key roles in mitochondrial biogenesis, respiration, and antioxidant defense of mitochondria, including PGC-1α, PGC-1β, and PGC-1 related coactivator (PRC) [62]. As a key regulator of ROS levels in mitochondria, PGC-1α affects mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative damage. The depletion of PGC-1α leads to elevated mitochondrial damage and ROS levels, whereas the upregulation of PGC-1α enhances the biogenesis of mitochondria and antioxidant gene activation, including superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) and thioredoxin-1 (TRX-1) [62]. NRFs play a crucial role in regulating the gene expression necessary for the maintenance of the mitochondrial respiratory system [63]. Specifically, NRFs directly influence the transcription of genes encoding cytochrome C [64] and facilitate the expression of vital components in the transcription and translation machinery of mitochondria, such as mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), mitochondrial ribosomal proteins, and tRNA synthetases, which are indispensable for the synthesis of respiratory subunits encoded by mtDNA [64].

An nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF-2)/PGC-1α-double-knockout (dKO) mice model has shown aged RPE degeneration like that seen in AMD patients [65]. The RPE cells showed enlarged size, increased oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, upregulated levels of PINK1, Parkin, LC3 [66], and accumulation of mitochondria and lysosomes which are damaged [65]. Moreover, loss of PGC-1α caused an increase of mitochondrial ROS (mtROS), and NRF-2 deficiency impairs the autophagy-mediated gradation system, speeding up mitochondrial damage aggregation. ZLN005 is a selective PGC-1α agonist that specifically activates PGC-1α, resulting in a significant increase in PGC-1α levels and its related transcription factors. This leads to an amplified expression of genes related to mitochondria and enzymes responsible for antioxidant activity in ARPE-19 cells [67] (Table 1). Metabolic profiling assay has revealed that ZLN005 treatment enhanced mitochondrial function in RPE cells by increasing basal and maximal respiration rates and spare respiratory capacity. Furthermore, without inducing cytotoxic effects, ZLN005 effectively protected ARPE-19 cells from H2O2-oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL)-NaIO3-mediated oxidative stress. Sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) is an NAD+-dependent mitochondrial deacetylase that regulates mitochondrial biogenesis [68]. Melatonin was reported to activate the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-PGC-1α-SIRT3 signaling pathway by promoting the activity of SOD2 [69]. Additionally, melatonin treatment can lead to a decrease in mitochondria superoxide content and an increase mitochondrial mass in the nonexudative-AMD mice model, which in turn recovers visual function [70] (Table 1). Based on these findings, it is believed that promoting mitochondrial biogenesis may protect ARPE-19 cells under oxidative stress and could serve as a potential strategy for AMD therapy. Furthermore, it is important to recognize that insufficient mitophagy can cause the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria, whereas simultaneous mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy help maintain mitochondrial homeostasis and enhance cellular survival under stress conditions (Fig. 3).

3. Implications of cGAS/STING pathway in AMD

Detection of nucleic acid material such as double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), and single-stranded RNA is significant for the immune response of various organisms [71]. In vertebrates, the antiviral immune system recognizes these exogenous DNA/RNA molecules through a variety of receptors [72]. Pathogen and mitochondrial-derived cytosolic dsDNA can activate multiple immune response pathways, including Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) [73], absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) [74], and nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor thermal protein domain-associated protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes [75], as well as the cGAS/STING pathway [76]. These pathways generate proinflammatory cytokines and interferon to combat viral infections.

The cGAS-STING pathway is a unique system that is activated by DNA, regardless of its origin. This makes it effective against various infections [76]. In addition to its protective role against pathogens, cGAS-STING pathway can also be activated by the self-DNA released into the cytosol under oxidative stress [77] (Fig. 4). When binding to DNA, cGAS constitutes a 2 × 2 dimer consisting of two cGAS and two DNA molecules, or more complex structures. This results in the activation of cGAS, which catalyzes ATP and GTP to synthesize cGAMP. cGAMP serves as a secondary messenger molecule that binds to and triggers the activation of the ER-associated adaptor protein STING. This interaction results in the recruitment and activation of TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) [78]. The formation of the STING-TBK1 complex facilitates the recruitment of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), which is subsequently phosphorylated, leading to its dimerization, translocation into the nucleus, and transcription of target genes. The function of IRF3 is indispensable for the transcription of a variety of target genes under different cellular stress conditions, including those involved in the production of inflammatory cytokines, interferon-I (IFN–I), and interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) [79]. Furthermore, activating STING also triggers the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), which leads to the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines [80].

Fig. 4.

Implications of cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)/stimulator of interferon genes (STING) immune pathways in age-related macular degeneration (AMD). DNA from chromosomes or mitochondria can activate the cGAS-STING pathway in retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) when it enters the cytosol. When binding to DNA, cGAS constitutes a 2 × 2 dimer consisting of two cGAS and two DNA molecules or more complex structures. This results in the activation of cGAS, which catalyzes ATP and GTP to synthesize cGAMP. cGAMP serves as a secondary messenger molecule that binds to and triggers the activation of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated adaptor protein STING. This leads to the recruitment and activation of TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), resulting in interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) phosphorylation and transcription of target genes involved in inflammation and immune response. The function of IRF3 is indispensable for the transcription of a variety of target genes under different cellular stress conditions, including those involved in the production of inflammatory cytokines, type I interferons (IFN-I), and interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs). Additionally, STING activation stimulates the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway, leading to the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. ROS: reactive oxygen species.

A variety of retinal cells express the cGAS-STING pathway, including RPE, photoreceptor cells, microglia, and Müller cells [81]. The STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy (SAVI) is a genetic disorder that results from a mutation of the STING gene, leading to abnormal and constant activation of STING [82]. This can cause severe inflammatory symptoms that can ultimately lead to pulmonary fibrosis and death. Constant activation of STING can also induce retinal vasculopathy, including extensive retinal exudates or vitreous hemorrhages with tractional retinal detachment [82], indicating that uncontrolled cGAS-STING pathway is associated with retinal retinopathy. Previous studies have shown that cGAS and STING levels increased in the mouse RPE and retina following oxidative injury, coinciding with a reduction in chromatin compaction [83]. Disruption of heterochromatin by sodium iodate (SI) in mice led to elevated expression of cGAS and STING, resulting in heightened inflammation in the retina. This process was mitigated by the treatment of methotrexate (MTX), a heterochromatin-promoting agent [83] (Table 1). Additionally, oxidative stress impairs DNA clearance and elevates VEGF levels in senescent RPE. The STING antagonist H-151 alleviates HIF-1α overexpression and inhibits the up-regulation of VEGF [84] (Table 1). Alu is a common transposable element in primate genomes, and human genomes contain around 1 million copies, which are localized in the cytosol and cause cytosolic Alu cDNA accumulation [85]. Cytosolic Alu cDNA can be sensed by cGAS to mediate its toxicity [86]. This process can lead to RPE degeneration in mice lacking other cytosolic nucleic acid sensors such as AIM2 and Toll-like receptors. Conversely, mice lacking cGAS or carrying loss-of-function mutations in cGAS are resistant to Alu-induced RPE degeneration [85]. Kerur et al. [87] have identified a non-canonical inflammasome pathway involved in the cause of RPE degeneration in both human and mouse models, which relied on the activation of cGAS-induced IFN by cytosolic mtDNA. The release of mtDNA was facilitated by diminished levels of ribonuclease RNAase the dicer 1, ribonuclease III (DICER1) gene, or Alu-RNA accumulation [87]. Alu-RNA may indirectly activate cGAS by inducing the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), allowing mitochondrial contents, such as mtDNA, to be released [87]. Further analysis has shown increases of STING RNA levels and chromatin accessibility, along with cGAS and STING promoters, in the macular retinas of patients with dry AMD [88]. Treatment with the bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) inhibitor JQ1 result in a reduction in cGAS-STING activation, which mitigated inflammation and photoreceptor degeneration in the injured retina [88] (Table 1). Therefore, cGAS is recognized as a prominent mediator of pathological cytosolic DNA signaling in AMD.

Several factors contribute to the development of AMD, with aging being the most significant. As one age, low-grade inflammation becomes a characteristic of our bodies and plays a principal role in age-related diseases [6]. Recent research showed that an increase in mitophagy levels was observed within the RPE and retina in elderly mice. This increase is concomitant with the activation of the cGAS/STING-mediated type I interferons (IFN-I) response, attributed to the release of cytosolic mtDNA. Moreover, pharmacological activation of mitophagy has been shown to inhibit cytosolic mtDNA accumulation and subsequent neuroinflammation, scotopic (dark) vision improvement, enhanced expression of genes involved in retinal metabolism, reduced indicators of aberrant integration of light stimuli, and glial inactivation in the retina of old mice [89]. Therefore, in the early stages of AMD, age-associated inflammation may represent one of the initial causes of the disease. Aging-associated mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage lead to the cytosolic release of mtDNA, which subsequently activates the cGAS/STING pathway, resulting in consequential inflammation. If MQC mechanisms are not properly regulated, an energetic crisis may precipitate, thereby contributing to the irreversible progression of AMD. These findings suggest that therapeutic strategies aimed at inhibiting the cGAS/STING pathway or promoting mitophagy could be potential therapeutic strategies to decrease cGAS/STING-related inflammation in the retina.

4. The crosstalk between the MQC and cGAS/STING innate immunity pathway in AMD

4.1. The immunogenic role of mitochondria

Originally derived from bacterial symbionts, mitochondria retain certain characteristics of their ancestry. These organelles replicate autonomously in the cytosol, independent of cell division [90]. The double membrane that encloses mitochondria consists of distinctive phospholipids not typically found in other eukaryotic membranes [91]. Furthermore, mtDNA maintains circular characteristics despite the great number of mitochondrial proteins being encoded in the nucleus [92]. Recent research has shown that mitochondria contain DAMPs that are similar to those found in infectious bacteria, shedding new light on the initiation of inflammatory immune reactions [93]. Notably, the PINK1/Parkin pathway has been linked to bacterial infections. Studies on mice lacking the PINK1 gene demonstrated heightened gut infection levels and the manifestation of Parkinsonian symptoms [93], indicating that deficiencies in MQC may trigger innate immune responses through decreased mitophagy, which could potentially contribute to the development of neurodegenerative symptoms.

4.2. mtDNA acts as a key interconnected mediator of cGAS/STING pathway

Mitochondrial damage can lead to the release of DAMPs such as mtDNA, mtRNA, cardiolipin, and N-formyl peptides. These DAMPs are capable of inducing sterile inflammation through various mechanisms [93]. One such mechanisms involves the release of mtDNA, which can occur under multiple cell stresses, including the formation of Bcl-2 antagonist/killer (BAK)/Bcl-2-associated X protein (BAX) pores [94], mPTP and voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) pores [95].

The cGAS-STING pathway is activated by mitochondrial nucleic acids, which can stimulate the IFN-I response for DNA or the retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)/melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5)-mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) pathway for dsRNA, respectively [96]. Recent research has shown that the most prominent gene signature upregulated in response to mitochondrial cristae injury is associated with the IFN-I response [97]. This response is reliant on STING rather than MAVS, suggesting that mtDNA serves as a critical mediator of the inflammatory reaction [97]. Moreover, IVI of mtDNA in rats has been shown to induce decreased wave amplitudes of electroretinogram (ERG) and retinal cell apoptosis, with upregulated protein levels of cGAS, STING, and IFN-β [98]. The IFN-I response in cells with damaged cristae was effectively suppressed upon the elimination of mtDNA [98]. In addition to releasing mtDNA into the cytosol, MDVs can also activate cGAS/STING [47]. Furthermore, a circulating cell-free mtDNA level increase has also been associated with cGAS/STING activation in some metabolic and mitochondrial diseases associated with MDVs [99].

Under oxidative stress or when there is mitochondrial dysfunction, the integrity of mtDNA can be compromised, resulting in the release of oxidized mtDNA into the cytoplasm. This, sequentially, can trigger proinflammatory signaling pathways, including IFN-I [100]. Additionally, extracellular mtDNA can be generated as a byproduct of EVs and extracellular traps (ETs), both of which have been implicated in the elevation of ROS under certain physiological conditions [101]. Notably, cytosolic mtDNA plays a key role in activating the cGAS/STING pathway in senescence by regulating the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) through MOMP [17]. There was strong evidence that mtDNA triggers the cGAS-STING-dependent IFN-I response not only under infectious conditions but also under a wide range of noninfectious conditions.

4.3. MQC restrains cGAS/STING innate immunity pathway

The mtDNA is usually protected by a protein called TFAM, which is present in the mitochondrial matrix and helps to increase its stability and resistance to oxidative stress [102]. Indeed, compared to newly synthesized uncoated mtDNA, mtDNA coated with TFAM is more resistant to oxidation and is less likely to leak into the cytosol [75,95]. Recent studies have suggested that reducing TFAM protein levels can lead to an increase in cytosolic mtDNA, which in turn activates the cGAS-STING pathway and promotes the growth of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) [103]. Moreover, depleting STING or degrading mtDNA can reduce the growth of TFAM-depleted ESCC [103], indicating that TFAM may be a potential target for modulating cGAS-STING pathway activation triggered by mtDNA.

Multiple studies have reported that the presence of hyperfragmented mitochondria, induced by OPA1 ablation and Drp1 overexpression, can promote the release of damaged mtDNA and cause inflammatory reactions in various metabolic disorders [100,104]. In another study, liver-specific Drp1 knockout mice fed with alcohol exhibited an increase in megamitochondria and cytosolic mtDNA, as well as a decrease in mitophagy, consequently leading to the activation of cGAS-STING-interferon signaling pathways and liver injury [105]. However, some studies suggest that mitochondrial hyperfusion during aging could be an adaptive mechanism to prevent MOMP and decrease mtDNA release [56]. Although it is difficult to conclude whether mitochondrial fusion or fission reduces the mtDNA in the cytoplasm, it is evident that abnormal mitochondrial dynamics can certainly impact mtDNA release. A better understanding of how mitochondrial dynamics affect mtDNA in pathological conditions requires further research.

The study of mice with Alzheimer's disease (AD) has revealed that the levels of NAD+, a metabolite that promotes mitophagy in human cells, were significantly decreased. In AD mice, administration of NAD+ precursor nicotinamide riboside (NR) has been found to decrease neuroinflammation, reduce ectopic DNA, and prevent cellular senescence. The cGAS/STING pathway has been implicated in NR treatment [106]. Additionally, a study has shown that nicotinamide (NAM) improved disease-related characteristics in human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) derived from patients with AMD through preserving ΔΨm, enhancing mitochondrial oxidative metabolism, and suppressing druse-associated proteins or factors, as well as components of the complement system [107] (Table 1). Nevertheless, further investigations researches are necessary to elucidate the anti-inflammatory properties of nicotinamide in the context of AMD. Mitochondrion-targeted antioxidant SS-31 has been found to protect neuro cells against postoperative cognitive dysfunction-induced neuroinflammation by promoting prohibitin 2 (PHB2)-mediated mitophagy activation, inhibiting mtDNA release [108]. SS-31 has also been reported to reduce apoptosis and oxidative damage in RPE cells treated with H2O2 by downregulating Bax and upregulating Bcl-2 [109] (Table 1). Immune-related guanosine triphosphatase M protein 1 (IRGM1), one of the IRGs, is involved in the clearance of mtDNA through mitophagy, and its absence can lead to autoimmune characteristics seen in lupus. IRGM1 may, therefore, be a connection between MQC and autoimmune diseases [110]. The aforementioned studies suggest that enhancing mitophagy can alleviate cGAS-induced inflammation by reducing mtDNA release (Fig. 5) in neurodegenerative and autoimmune diseases. Although in vivo evidence is limited in AMD, promoting autophagy can improve mitochondrial function in RPE cells derived from patients [28]. Furthermore, enhanced mitophagy can alleviate age-related inflammation in the retina by reducing mtDNA release [89]. Collectively, these findings indicate that targeting MQC processes may represent a promising approach for mitigating cGAS-induced inflammation in AMD. However, further research is required to validate this strategy prior to clinical implementation.

Fig. 5.

Mitophagy partially alleviates cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-induced inflammation by reducing the release of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) into the cytoplasm. mtDNA is usually shielded by the mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) within the mitochondrial matrix, leading to the stability of mtDNA and resistance against reactive oxygen species (ROS) oxidation. When compared to newly synthesized uncoated mtDNA, mtDNA coated with TFAM is less likely to be oxidized and leak into the cytosol. However, it is still possible to release mtDNA into the cytosol in response to various stresses on a cell through mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP). Mitochondrial-derived vesicles (MDVs) can also mediate the release of mtDNA. mtDNA can activate cGAS-induced innate immunity when released into the cytosol. However, mitophagy can decrease mtDNA release in the cytoplasm and alleviate cGAS-induced inflammation. BAX: Bcl-2-associated X protein; BAK: Bcl-2 antagonist/killer; VDAC: voltage-dependent anion channel; STING: stimulator of interferon genes; IRF3: interferon regulatory factor 3; IFN-I: type I interferons.

4.4. cGAS/STING pathway in turn affect the function of MQC

In addition to its role as a crucial cytosolic DNA sensor, the cGAS molecule has been demonstrated by Liu et al. [111] to exert an influence on the DNA repair mechanism. In mouse models, cGAS inhibited homologous recombination by moving to the nucleus in response to DNA damage, which depends on importin-α and phosphorylation at tyrosine 215 by B-lymphoid tyrosine kinase. Once in the nucleus, cGAS interacted with ADP-ribose to disrupt the poly ADP-ribose polymerase 1 (PARP1)-Timeless complex and suppress homologous recombination. However, it is yet unknown whether cGAS can inhibit the repair mechanisms of mtDNA in the retinal cells of AMD. Knockdown of cGAS has been observed to inhibit tumor growth and reduce DNA damage. Moreover, both in vitro and in vivo models of hepatocellular carcinoma cells have been shown to benefit from mitochondrial cGAS subcellular localization in protecting them from ferroptosis [112]. Specifically, an interaction between cGAS and Drp1 facilitates the oligomerization of cGAS at the OMM. Disruption of this cGAS-Drp1 complex led to increased mtROS and ferroptosis, ultimately inhibiting tumor growth. The study suggests that targeting cGAS-Drp1 interactions within mitochondria may offer novel strategies for cancer intervention [112]. Yet, it is unknown whether the cGAS-Drp1 interaction exists in AMD retinal cells. Besides these findings, the cGAS/STING pathway is also essential for autophagy activation [113]. Specifically, in human cells with extra chromosomes, cGAS was responsible for triggering autophagy [72]. The sea anemone Nematostella vectensis has been shown to induce autophagy without eliciting an interferon response when stimulated by cGAMP, indicating that autophagy is an important effector of cGAS/STING. Additionally, both cGAS and STING interact with LC3 to induce autophagy [114]. This pattern of autophagy is vital for maintaining intracellular homeostasis, regulating immune responses, and limiting tumor growth [113].

5. Natural products for treatment of AMD by targeting the MQC and cGAS/STING innate immunity pathway

As a viable therapeutic approach for AMD, modulating the MQC and cGAS/STING pathways has been widely investigated. Current pharmacotherapeutic agents targeting the MQC and cGAS/STING pathways, such as rapamycin, ZYAN1, MTX, H-151, JQ1, and SS-31, have several limitations. For example, several autophagy activators and immunosuppressants exhibit significant systemic adverse effects. Most cGAS inhibitors exhibit limited biological efficacy and insufficient metabolic stability, hindering their potential as pharmaceutical candidates for clinical use, despite their notable anti-inflammatory properties. Moreover, macromolecules targeting the MQC and cGAS/STING pathways have limited penetration across the blood-retina barrier, limiting their therapeutic efficacy. However, the development of efficient, highly specific, and safe drugs is time-consuming and expensive. For these reasons, alternative therapeutic modalities that are safe and more affordable are urgently needed.

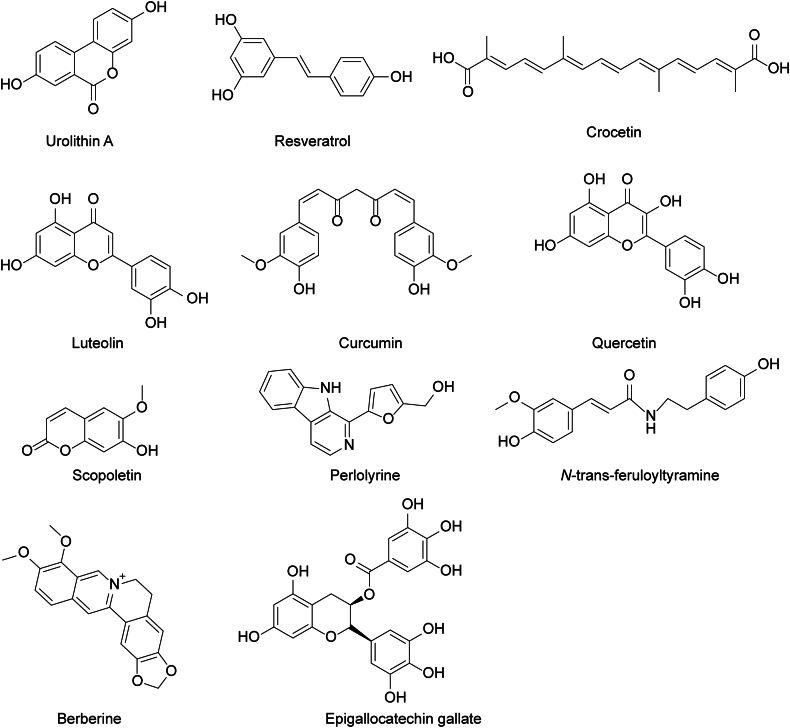

Natural products have emerged as a promising alternative strategy owing to their unique efficacy, diverse chemical structures, long half-lives, ready availability, and lower toxicity. Considering these advantages, here we highlight some natural drugs (Fig. 6) that directly or indirectly target the MQC and cGAS/STING pathways, which may provide novel insights into their therapeutic potential for AMD (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

The chemical structure formula of phytochemicals targeting mitochondrial quality control (MQC) and cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)/stimulator of interferon genes (STING) immune pathways to treat age-related macular degeneration (AMD). The chemical structural formula of urolithin A, resveratrol, crocetin, luteolin, curcumin, quercetin, scopoletin, perlolyrine, N-trans-feruloyltyramine, berberine, and epigallocatechin gallate. The constituents of extracts of L. barbarum berries including scopoletin, perlolyrine, and N-trans-feruloyltyramine.

Fig. 7.

Mechanism of phytochemicals targeting mitochondrial quality control (MQC) and cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)/stimulator of interferon genes (STING) immune pathways to treat age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Sirt1: silent information regulator 1; Nrf2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; LBP: Lycium barbarum polysaccharides; NAD+/NADH: oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide/nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NAM: nicotinamide; BBR: berberine; AMPK: adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; PGC-1α: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α; NRF1/2: nuclear respiratory factors 1/2; TFAM: mitochondrial transcription factor A; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin; ULK: UNC-51-like kinase; UA: urolithin A; HHC: hexahydrocurcumin; Drp1: dynamin-related protein 1; PINK1: PTEN-induced putative kinase1; BNIP3: Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa associated protein 3; NIX: NIP3-like protein X; FUNDC1: FUN14 domain containing 1; mtDNA: mitochondrial DNA; NLRP3: nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3; BAK: Bcl-2 antagonist/killer; BAX: Bcl-2-associated X protein; RSVL: resveratrol; EGCG: Epigallocatechin gallate; MTX: methotrexate; IFN-I: type I interferons; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa B.

5.1. Urolithin A (UA)

Urolithins are metabolites produced in the colon through the microbiome-mediated transformation of the natural polyphenols ellagitannins and ellagic acid, which are found in dietary products such as pomegranates [115]. UA has been demonstrated to upregulate mitochondrial biogenesis genes and OXPHOS [116]. As a natural inducer of mitophagy, UA inhibits the mTOR pathway, promotes the PINK1/Parkin pathway, and reduces the activation of mtDNA-mediated cGAS/STIN in vivo models to mitigate oxidative stress [89]. Additionally, administration of 2.3 mg/kg/day of UA via intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) for 8 weeks in aged mice has been shown to improve night vision and reduce indicators of aberrant integration of light stimuli [89] (Table 2). Therefore, due to its high safety profile and its ability to improve MQC using both in vitro and in vivo methods, along with its potent anti-inflammatory effects, further investigation is warranted for the potential application of UA in AMD treatment [89].

Table 2.

The effects of natural products on mitochondrial quality control (MQC) and/or cyclic GMP-AMP synthase/stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS/STING) pathway in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) models.

| Agent | Mechanism | Cell types affected or animal models | Administration | Findings | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resveratrol | Alu-RNA↓ cGAS↓ | Alu-RNA transfected RPE-19 cells |

40 μM pretreated | Alu-RNA induced RPE death↓cGAS-induced immune responses↓ | [86] |

| Urolithin A | mTOR↓ PINK1/Parkin pathway↑ Mitochondrial biogenesis↑ |

Old mice | 2.3 mg/kg/day (i.p.) for 8 weeks | Scotopic vision and quality↑ Expression of retinol metabolism genes↑ Glial activation in the retina of old mice↓ |

[89] |

| EGCG | Alu-RNA↓ cGAS↓ | Alu-RNA transfected RPE-19 cells |

20, 40 μM pretreated | Alu-RNA induced RPE death↓ cGAS-induced immune responses↓ | [86] |

| Formation of LC3-II↓ Autophagosomes↓ |

UV-B exposure RPE-19 cells |

50 μM for 3 h | Toxic effects of UV-B↓ | [121] | |

| Crocetin | mTORC1↓ VEGF, IL-1β, and HIF-1α↓ |

Endothelial cells | 100, 200 μM | Rate of proliferating cells↓ Cell migration↓ Tube formation↓ |

[125] |

| Cobalt chloride-induced RPE-19 cells |

50, 100 μM | Hypoxic injury↓ | |||

| Laser-induced CNV mouse model | 100 mM/1 μL/eye IVI |

Laser-induced CNV↓ | |||

| Curcumin | LC3-II/LC3-I ratio↑ | Autophagy inhibitor-treated RPE cells from human |

10 μM | Autophagy↑ | [128] |

| HHC | Bcl-2↑, Bax↓ SOD2, Beclin-1, p62 and LC3-II↑ |

Blue light exposure RPE-19 cells Primary RPE cells from blue light exposure mouse |

1, 5 and 15 μM | Autophagic flux↑ Oxidative stress↓ Endoplasmic reticulum stress↓ |

[130] |

| Quercetin | SOD2↓ Catalase, GSH, diacetyl-SOD2↑ LC3↓ |

NaIO3-treated mouse model | 100 mg/kg (i.p.) | ROS production↓ Drusen-like uneven lesions↓ Ameliorated the deformation of the retinal layers Pupillary response↓ |

[134] |

|

p-Nrf2, HO-1, Sirt1, and PGC-1α↓ Beclin-1, LC3B-II, and p62↓ Bcl-2↑ |

NaIO3-treated RPE-19 cells | 1.25, 2.5 and 5 μM pretreated | ROS production↓ Autophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis↓ |

||

| Lycium barbarum L. berry extracts (scopoletin, perlolyrine, and N-trans-feruloyltyramine) | SOD, GSH↑ IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α↓ |

1% hydroquinone diet fed AMD mice model | Water extract: 1105 mg/kg/day for 3 months |

Retinal degeneration↓ ROS production↓ Pro-inflammation cytokines↓ Altered serum metabolite |

[136] |

| Ethanol extract: 173 mg/kg/day for 3 months | |||||

| SOD, GSH↑ Nrf2↑ the heme HO-1↑ |

Sodium iodate-treated RPE cell |

LBW-95E: 1, 3 and 10 μg/mL |

Cell viability↑ Antioxidant capacity↑ |

||

| LBP | Nrf2↑ | Light-induced AMD mice model | 150 or 300 mg/kg | Retinal damage caused by exposure to light↓ ROS production↓ Antioxidative genes↑ Oxidative stress↓ |

[138] |

| Berberine | Preserve ΔΨm; Caspase 3/7↓ Phosphorylation of AMPK↑ |

H2O2-treated D407 cells | 0.3, 1 and 3 μM | ROS production↓ Cell death and apoptosis↓ Abnormal changes in nuclear morphology↓ |

[142] |

| H2O2-treated hRPE cells | |||||

| Caspase 3/7↓ LC3-BII/LC3-BI↑, autophagy↑ Phosphorylation of AMPK and ULK1↑ mTORC1↓ |

H2O2-treated D407 cells | 1, 3 and 6 μM | Cell death and apoptosis↓ | [144] | |

| H2O2-treated hRPE cells | |||||

| Luteolin | Nrf2 nuclear translocation↑ HO-1, SOD and GSH↑ p-AKT, GSK-3β↓ |

H2O2-treated RPE-19 cells |

10, 20 and 40 mM | Cell death and apoptosis↓ Cell migration↓ H2O2-induced EMT↓ |

[150] |

The “↑” arrow means upregulation, and the “↓” arrow means downregulation.

RPE: retinal pigment epithelium; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin; PINK1: PTEN-induced putative kinase1; EGCG: epigallocatechin gallate; LC3: microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; UV-B: ultraviolet b; mTORC1: rapamycin complex 1; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; IL-1β; interleukin 1-beta; HIF-1α: hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha; CNV: choroidal neovascularization; IVI: intravitreal injection; HHC: hexahydrocurcumin; Bcl-2: B-cell lymphoma-2; BAX: Bcl-2-associated X protein; SOD2: superoxide dismutase 2; p62: sequestosome-1; GSH: glutathione; ROS: reactive oxygen species; Nrf2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; HO-1: heme oxygenase-1; Sirt1: silent information regulator 1; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α; LBW-95E: water extracts of L. barbarum berries eluted with 95% ethanol; LBP: Lycium barbarum polysaccharides; ΔΨm: mitochondrial membrane potential; AMPK: adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; ULK1: UNC-51-like kinase 1; hRPE: human retinal pigment epithelial; AKT: protein kinase B; GSK-3: glycogen synthase kinase-3; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

5.2. Resveratrol (RSVL)

RSVL is a non-flavonoid polyphenol that is extracted from grapes and red wine and has been utilized for clinical applications. Biologically, it could trigger autophagy and mitigate ROS. Additionally, RSVL has been shown to increase NRF-1 and TFAM levels and inhibit mitochondrial fusion by modulating the PINK1/Parkin pathway, thereby enhancing mitochondrial turnover [117]. Moreover, RSVL can downregulate NF-κB expression to exhibit anti-inflammatory effects [118]. Recent studies have suggested that RSVL holds promise as a therapeutic option for AMD by reducing the cytotoxic and immunogenic effects of Alu-RNA [86] (Table 2). Pretreatment with 40 μM RSVL inhibited Alu-RNA-induced RPE-19 cell death and reversed the immune response mediated by cGAS [86] (Table 2). The results of these studies further support RSVL's potential role as a potential therapy for AMD.

5.3. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG)

Green tea is known to contain the highest concentration of EGCG, a compound that has various effects on human biology, such as anti-cancer, neuroprotection, and cardio protection [119]. EGCG is recognized as a medicinal agent that targets mitochondria [119], leading to the upregulation of mitochondrial respiratory enzymes and improved activity redox enzymes, such as SOD [120]. When RPE cells were exposed to ultraviolet b (UV-B) radiation, the amount of LC3-II protein was increased in a dose-dependent manner. EGCG treatment has been shown to reduce the formation of LC3-II and autophagosomes, leading to mitigated toxic effects of UV-B radiation on RPE cells [121] (Table 2). Moreover, 40 μM of EGCG has been found to almost block IFN expression triggered by Alu, effectively suppressing the immunogenic effect on RPE cells [86] (Table 2). These findings provide evidence supporting EGCG as a potential intervention for treating AMD. In addition, EGCG was found to increase PGC-1α mRNA expression by enhancing promoter activity in human hepatocellular carcinomas HepG2 cells [122]. Hence, it is needed to further investigate the relationship between MQC and EGCG. Overall, these findings indicate that EGCG holds promising potential to be a valuable therapeutic agent for treating AMD.

5.4. Crocetin

Saffron is one of the spices extracted from the stigmas of Crocus sativus L. flowers. Notably, saffron tablets containing 20 mg of saffron have been shown to enhance visual acuity and focal flash electroretinogram (fERG) sensitivity in patients with AMD following a 12- to 15-week treatment regimen [123]. Recent studies have demonstrated that saffron exhibits several therapeutic properties due to its major components, such as safranal, crocin, and crocetin, all of which are potent antioxidants. The pharmacological activities of crocetin have been extensively demonstrated, encompassing anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, neuroprotective, and anticancer effects [123]. The mTOR pathway has been identified as an essential factor in neovascularization, and mTOR inhibition led to significant suppression of choroidal neovascularization [124]. Crocetin inhibited the proliferation, migration, and tube formation induced by VEGF in vascular endothelial cells, according to recent studies. Additionally, crocetin treatment also suppressed the mechanistic target of the rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway, alleviated hypoxic damage in RPE cells, and inhibited laser-induced CNV formation in mouse models [125] (Table 2). Furthermore, crocetin mitigated the toxicity induced by UV-B and ultraviolet A (UV-A) in human corneal epithelial cell-transformed (HCE-T) cells [126]. Based on these findings, further investigation is warranted to explore the potential of crocetin as a pharmacological intervention for the treatment of AMD.

5.5. Curcumin

Curcumin, a phytochemical compound found in turmeric, has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer properties, attracting wide attention [127]. Research indicated that curcumin significantly contributed to the enhancement of mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy, suggesting its potential therapeutic efficacy in enhancing cellular function and preventing age-related disease [127]. Empirical studies demonstrated that curcumin can stimulate autophagy by reversing the reduction in the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio induced by 3-methyladenine (an autophagy inhibitor in the early-stage of autophagy) in RPE-9 cells [128] (Table 2). These findings imply that curcumin may induce autophagy to mitigate AMD. Another metabolite of curcumin, hexahydrocurcumin (HHC), has demonstrated superior retinal protective capacity compared to curcumin [129]. HHC exhibited increased stability within the human body after metabolism, leading to a prolonged antioxidative stress effect. Blue light-induced oxidative stress, ER stress, and apoptosis were reduced by HHC administration in ARPE-19 cells and primary RPE cells isolated from mice [130] (Table 2). These results suggest that curcumin holds potential as a therapeutic candidate for the prevention and treatment of AMD. However, the limited solubility of curcumin in aqueous environments and its poor bioavailability in both clinical and experimental contexts have hindered its therapeutic application. Therefore, it is imperative to improve the bioavailability of curcumin to attain higher concentrations in target cells.

5.6. Quercetin (QT)

Known for its potential pharmacological applications and antioxidant properties, QT is a flavonoid found naturally in fruits and vegetables. Previous research has demonstrated that QT functioned as a free radical scavenger and exhibited anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, and neuroprotective effects [131]. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that QT can confer protection to RPE cells against ROS-induced cellular damage by upregulating the expression of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2). This upregulation mitigated ER stress and inhibited apoptosis [7]. These results findings highlight the potential therapeutic benefits of QT in combating oxidative stress-related retinal degeneration, presenting a promising strategy for managing AMD. Nrf2, a transcription factor, plays a crucial role in modulating cellular redox equilibrium. Upon exposure to oxidative stress, Nrf2 translocates into the nucleus, leading to the transcription of downstream proteins involved in antioxidant defense mechanisms and autophagy [132]. Furthermore, Nrf2 binds to antioxidant response elements (AREs) sequences within gene promoters related to mitochondrial biogenesis, such as NRFs, TFAM, and PGC-1α, facilitating the synthesis of mitochondria in RPE cells [133].

Recent research conducted by Hsu and colleagues [134] (Table 2) has demonstrated that QT treatment led to the reversal of morphological alterations in the retina, which were associated with oxidative stress due to the downregulation of SOD2 and the upregulation of catalase and glutathione (GSH) levels. The study also revealed that QT reduced mtROS production by inactivating the Nrf2-PGC-1α-silent information regulator 1 (Sirt1) pathway, resulting in increased diacetyl-SOD2 levels. However, these findings are in contradiction to the results of previous studies by Shao et al. [7] and Chang [135]. Furthermore, previous research has shown that autophagic flux is strongly linked to AMD, and the presence of drusen in the retina suggested proteostasis issues due to lysosome/autophagy pathway failure [15,16]. Interestingly, the study by Hsu et al. [134] (Table 2) has found that NaIO3-induced oxidative stress upregulated autophagy-associated proteins. On the other hand, QT suppressed Bcl-2-mediated cellular autophagy by decreasing the expression levels of BECN1, LC3B-II, and p62 and up regulating Bcl-2 in NaIO3-treated mouse models and ARPE19 cells. These findings suggest that the NaIO3-induced model may not comprehensively replicate the pathology of human AMD, or that autophagy may manifest distinct effects at various stages of the disease. Therefore, further investigation is needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying QT's impact on AMD and to ascertain whether the observed alterations in autophagy are advantageous or deleterious.

5.7. Lycium barbarum L. berry extracts and Lycium barbarum polysaccharides (LBP)

The dried, ripe fruit of the Solanaceae plant Lycium barbarum L., commonly known as Lycium barbarum L. berry, is rich in carotenoids, flavonoids, and polysaccharides, all of which exhibit potent antioxidant properties. Emerging research suggests that extracts of Lycium barbarum L. berry can enhance retinal function, reduce oxidative stress, and reduce inflammation in mice to prevent AMD [136] (Table 2). Of note, water extracts of L. barbarum berries eluted with 95 % ethanol (LBW-95E) have been reported to be particularly efficacious in promoting nuclear translocation of Nrf2, increasing SOD and GSH content, and decreasing the accumulation of ROS in SI-damaged RPE cells [136] (Table 2). The constituents of LBW-95E, including scopoletin, perlolyrine, and N-trans-feruloyltyramine, were believed to be responsible for its antioxidant activity [136] (Table 2).

Furthermore, LBP is one of the main bioactive constituents of Lycium barbarum L. berry, which exhibits remarkable efficacy in safeguarding optical receptors against degeneration, apoptosis, and oxidative inflammation in AMD animal models [137]. LBP has been demonstrated to confer protection to photoreceptor cells against light-induced retinal damage by upregulating the expression of antioxidative genes and enhancing overall antioxidant capacity. Notably, the administration of LBP in murine models resulted in a significant upsurge in the levels of Nrf2 and thioredoxin reductase 1 (TrxR1) mRNA [138] (Table 2). Additionally, LBP treatment mitigated hyperglycemia-induced increase in phospho-Drp1 and decrease in OPA1, thereby preserving the balance between mitochondrial fission and fusion, and attenuating hyperglycemia-exacerbated ischemic brain injury [139].

Those findings suggest that Lycium barbarum L. berry holds potential as a promising natural resource for developing pharmaceuticals or dietary supplements to protect the retina. However, further research is necessary to elucidate the link between MQC and inflammation in response to Lycium barbarum L. berry treatment in AMD.

5.8. Berberine (BBR)

In Chinese herbal medicine, BBR has been traditionally used for centuries as an isoquinoline alkaloid derived from Coptidis rhizoma. In addition to hypoglycemic treatment, it also possesses antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory properties [140]. Recent research has shown that BBR has the potential to safeguard the retina against light-induced degeneration in mouse models through mechanisms such as mitigating thinning and disorganization of the photoreceptor layer, reducing oxidative stress, inhibiting infiltration of microglia/macrophages, and preventing cell death to maintain the integrity of photoreceptors [141]. Moreover, it was implicated in protecting H2O2-treated D407 cells and primary cultured human retinal pigment epithelial cells (hRPE cells) by inhibiting oxidative damage and caspase 3/7 activities, preventing the decline in ΔΨm through activating of the AMPK pathway [142] (Table 2). BBR is a well-known activator of AMPK, which plays an important role in autophagy, mitophagy, and mitochondrial biogenesis [143]. Furthermore, the AMPK signaling axis is crucial for RPE cell apoptosis. Recent studies have demonstrated that BBR activated the AMPK/mTOR/UNC-51-like kinase 1(ULK1) signaling pathways and suppressed mTORC1 activity, thereby promoting autophagy in H2O2-induced D407 cells and hRPE cells. This supported the potential use of BBR for the prevention and treatment of AMD [144] (Table 2). In addition to the above, Hang et al. demonstrated that BBR protected cardiomyocyte from high glucose-induced hypertrophy by enhancing mitochondrial function and promoting both mitogenesis and mitophagy. The authors emphasized that the increased removal of dysfunctional mitochondria was facilitated by the AMPK signaling pathway activation [145]. Further investigations focused on the potential role of BBR in promoting mitogenesis and mitophagy through the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 pathways in AMD are required.

5.9. Luteolin

Luteolin exhibits promising therapeutic potential in vitro and in animal models as an anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and neuroprotective agent [146]. Recent studies have demonstrated that luteolin exhibits neuroprotective properties by preventing glutamate-induced neuronal apoptosis and reducing the accumulation of ROS. This protective effect is believed to be mediated through the restoration of mitochondrial function, mitigation of mitochondrial dysfunction, and suppression of excessive autophagy and mitophagy. Specifically, luteolin treatment has been shown to inhibit excessive mitophagy by deactivating BNIP3L/NIX, thereby attenuating autophagy-mediated neuronal cell death via the activation of mTORC1 [146]. In ophthalmological investigations, luteolin has demonstrated protective effects against oxidative stress and inflammation in ARPE-19 cells [147]. Moreover, luteolin has been shown to elevate GSH levels and suppress the expression of NF-κB and interleukin 1beta (IL-1β) in the retina [148]. Subsequent investigations have revealed that the anti-inflammatory properties of luteolin are attributed to its ability to induce AKT (known as protein kinase B or PKB) phosphorylation, leading to the inhibition of NF-κB translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and the suppression of mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) inflammatory pathways in IL-1β-stimulated RPE cells [149]. A separate investigation has demonstrated that luteolin suppressed EMT triggered by oxidative damage in ARPE-19 cells via the AKT/glycogen synthase kinase-3 β (GSK-3β) pathway [150] (Table 2). These results indicate that luteolin may serve as a viable therapeutic option for dry AMD. Nevertheless, additional research is warranted to elucidate the precise mechanism and pharmacological impact of luteolin in the treatment of AMD.

6. Conclusion