Abstract

Comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography-olfactometry-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC × GC-O-TOF-MS) is valued for its high resolution, sensitivity, and odor identification in complex food aroma analysis. However, few studies have combined it with sensomics to identify aroma-active compounds in oriental melons. Key aroma-active compounds of two oriental melons (LONG4 and ZHCG) were characterized using optimized headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME) combined with GC × GC-O-TOF-MS and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS), aroma extraction dilution analysis (AEDA), aroma recombination and omission experiments. 124 volatiles and 32 aroma-active compounds were identified by HS-SPME-GC × GC-O-TOF-MS. Of these, 22 with a high flavor dilution factor (FD > 2) were accurately quantified by HS-SPME-GC–MS. Aroma recombination and omission experiments demonstrated that eight compounds were the key odorants contributing to the fruity and sweet aroma of LONG4, while seven compounds were the key odorants contributing to the grassy and cucumber aroma of ZHCG. This study provides support for aroma-oriented quality control and production of oriental melons.

Keywords: Oriental melons, Climacteric and non-climacteric, Headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME), Aroma-active compounds, Aroma extraction dilution analysis (AEDA), Odor activity value (OAV)

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Aroma-active compounds in oriental melons were identified by GC × GC-O-MS and GC–MS.

-

•

The key aroma-active compounds were determined by GC–MS, AEDA, OAV, and omission recombination experiments.

-

•

The significant odorants were 2 esters with fruity aroma in LONG4.

-

•

The significant odorants were 2 aldehydes and 2 alcohols with green aroma in ZHCG.

1. Introduction

Melon, a highly polymorphic species, is categorized into two subspecies: C. melo ssp. melo and ssp. agrestis (Kirkbride Joseph, 1993), based on the existence of ovary hairs. Among them, ssp. Agrestis, also named oriental melon, is renowned for its richer, distinctive, and diverse aroma (Wang et al., 2023), with an annual production of 7.63 million tons in China (National Bureau of Statistics, 2022) and 10 % larger cultivation area than ssp. melo (Zhang et al., 2022). Aroma profiles vary greatly between climacteric and non-climacteric oriental melon varieties due to different ripening behaviors (Esteras et al., 2018). Consumers often praise climacteric oriental melons for their rich, fruity aroma, and are also known as ‘Xianggua’ in China. Among them, LONG4 is the most representative variety, with an intensely fruity aroma, and is mainly eaten as a fruit. In addition, among non-climacteric oriental melons, ZhongHuaCaiGua (ZHCG) has also attracted attention for its cucumber-like and crisp aroma. Extensive qualitative and quantitative analysis on volatiles (Chen, Zhou, et al., 2016) indicates that esters, alcohols, and aldehydes are the primary volatiles in climacteric oriental melons, while non-climacteric varieties have lower ester levels and higher aldehyde and alcohol concentrations (Chen, Cao, et al., 2016). However, little attention has been given to identifying aroma-active compounds, which significantly influence aroma quality and have substantial commercial potential as essence. Furthermore, almost all studies have focused on ssp. melo varieties such as cantaloupe and muskmelons (Pang, Chen, et al., 2012), neglecting the aroma profiles and key aroma-active compounds of oriental melons.

The sensomics methodology was a range of analytical techniques, including qualitative analysis of aroma-active compounds, aroma extract dilution analysis (AEDA), quantitative analysis, computation of odor activity value (OAV), and aroma recombination, and omission experiments. Headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME), a solvent-free technique with high sensitivity and simplicity, has been enhanced by SPME Arrow technology featuring denser coatings for broader analyte detection (Manousi et al., 2023). When integrated with comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography-olfactometry-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC × GC-O-TOF-MS), this approach effectively resolves co-eluting volatiles while pinpointing odor-active regions through multidimensional separation and olfactory detection. For instance, Studies using GC × GC-O-MS in Zanthoxylum bungeanum (Zhao et al., 2022) and tomato paste (Li et al., 2023) have identified 1.6 - 6fold more volatile compounds and aroma-active compounds than GC-O-MS. By integrating with molecular sensory science techniques such as aroma extract dilution analysis (AEDA), odor activity value (OAV), aroma recombination, and omission tests, GC × GC-O-TOF-MS has been employed for decoding the chemical odor codes of a given food (Shi et al., 2024). However, this method has not been applied to identify and validate the key aroma-active compounds in different aroma types of oriental melon.

The objectives of this study were to (1) optimize the HS-SPME extraction method and analyze the composition of the volatile compounds in two oriental melons using GC × GC-O-TOF-MS; (2) characterize and quantify the aroma-active compounds by GC–MS, AEDA, and OAV; (3) assess their significance in the overall aromatic profile using aroma recombination and omission experiments. The findings can better guide the evaluation of the aroma of oriental melons to provide data to support the breeding of high-quality varieties preferred by consumers.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Samples and reagents

Methanol of high-performance liquid chromatography grade was purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Analytical grade sodium chloride (NaCl) and n-ketones (C7 - C22) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent (Shanghai, China). 2-methylheptan-3-one was the internal standard (First standard, Tianjin, China). The 32 aroma reference standards for quantitative analysis listed in Table S1 were all obtained from Dr. Ehrenstorfer (Augsburg, Germany) and CATO Research Chemicals Inc. (Guangzhou, China) (No. 5, 6, 7, 8, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70). The 8 sugars (analytical pure), 8 organic acids (analytical pure), and 21 amino acids (reference standards) for qualitative analysis listed in Table S2 were all obtained from Acros Organics (Waltham, USA), Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and yuanye Bio-Technology (Shanghai, Beijing).

LONG4 and ZHCG were cultivated in a solar greenhouse in the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Beijing, China) in October 2023. Representative melons of the best edible quality have been harvested according to the experience of melon growers. Mature LONG4 and ZHCG fruits were harvested at 37 and 30 days after anthesis, respectively, with skin color shifting to a lighter shade. The firmness of the mesocarps of LONG4 and ZHCG averaged at 3.93 N and 5.31 N, respectively. The Brix levels were recorded at 8.6 and 5.4, and the weights were determined to be 350 g and 780 g, correspondingly. At least nine fruits in each group were collected, each replicate containing 3.

2.2. Sample preparation

Fruits from each cultivar were separated into 3 replicates and transferred to a 4 °C preparation room for further processing.

One piece was cut into 5–6 slices for the optimization study and volatiles analysis and blended using a juicer. A 20-mL screw-cap bottle was filled with oriental melon juice, sodium chloride, and 10 μL of the internal standard, 2-methylheptan-3-one (32.75 mg/L). Subsequently, the bottle was sealed and stored at 4 °C. All volatiles analyses were completed within two days to ensure that no noticeable changes occurred in a batch.

One piece was chopped into small pieces, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and ground to a fine powder for the analysis of sugars, organic acids, and amino acids. All samples were stored at −80 °C until analysis.

For the sensory analysis, one piece was cut into 5–6 slices. Each slice was cut into trapezoidal-shaped pieces with width ranging from 2 to 3 cm and height ranging from 1.5 to 2.0 cm. The melon pieces were randomly assigned to plastic containers with lids and stored at 5 °C for one day under aerobic conditions. Prior to sensory evaluation, the melon pieces were stored for 2 h at ambient temperature (approximately 22 °C).

2.3. E-nose analysis

An E-nose system (PEN 3.5, Airsense Analytics, GmBH, Schwerin, Germany) equipped with 10 metal-oxide semiconductors (W1C, W5S, W3C, W6S, W5C, W1S, W1W, W2S, W2W, and W3S) was utilized for the analysis (Table S3). 10.0 g oriental melons juice was placed a 20-mL screw-cap bottle, and analyzed according to our previous methods (Wang et al., 2023). Briefly, the sensor cleaning and automatic zero adjustment lasted 180 s and 10 s, respectively. The internal and inlet flow rates were 400 mL/min. The detection time was 80 s, and each sample was measured thrice.

2.4. Optimization of HS-SPME

The optimization of four parameters, each with five levels resulting in 20 experimental designs, was conducted for the HS-SPME technology using univariate analysis. The primary variable was the SPME Arrow fiber, with this study utilizing five distinct fibers: 100 μm polyacrylate (PA), 100 μm polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), 120 μm polydimethylsiloxane-divinylbenzene (PDMS/DVB), 120 μm carbon wide range-polydimethylsiloxane (Carbon WR/PDMS), and 120 μm divinylbenzene‑carbon wide range-polydimethylsiloxane (DVB/Carbon WR/PDMS). Before extraction, each fiber was activated at 260 °C for 30 min to eliminate any trace impurities.

Centrifugation and preparation under low-temperature conditions were employed to ensure the melon juice's distinctive aromatic character retention. A 20 mL screw-top vial was filled with 1–3.0 g of the melon juice, 0–2.0 g of NaCl, and 10 μL of the internal standard 2-methylheptan-3-one (32.75 mg/L). These vials were then securely sealed and placed in an auto-sampler (CTC PAL RTC, Guangzhou Ingenious Laboratory Technology, China) for headspace (HS) volatile extraction using the SPME Arrow fiber. The samples were agitated at 40 °C for a predetermined duration (10–50 min) to achieve equilibrium between the solution and headspace. The SPME Arrow fiber was immersed in the headspace of the sealed vial for 30 min to adsorb volatile compounds, after which it was retracted and inserted into the heated injection port of the GC for desorption at 250 °C for 5 min. While optimizing each parameter, all other variables were held constant. The parameters optimized in the preceding steps were applied in subsequent optimization processes.

2.5. GC × GC-O-TOF-MS analysis

Volatile compounds were analyzed by a GC × GC-TOF-MS (GGT 0620, Guangzhou Hexin Instrument Co., ltd, China) with an autosampler equipped with an agitator, heater stirrer, and SPME arrow conditioning station, and olfactory detection port (275P-1109, GL Sciences Instrument Co. ltd, Japan).

For GC, helium (99.999 % purity) served as the carrier gas at 1 mL/min, with the injector and transfer line at 250 °C. A Hexin HV column was used for modulation (9 s period), complemented by a DB-5MS primary column. The temperature protocol started at 40 °C for 2 min, rose to 200 °C at 2 °C/min, then to 270 °C at 6 °C/min, and held for 5 min. A DB-17 secondary column was employed with oven and modulator offsets at 0 °C and ﹢30 °C, respectively.

For MS, the ion source was set at 250 °C, scanning 10–550 m/z with EI at 70 eV and a detector voltage of 1780 V.

Three trained panelists conducted daily olfactory assessments for 2 h per day in the month preceding the analysis to identify and characterize the aroma of model solutions containing different concentrations of reference compounds. Throughout the experiment, aroma descriptions, intensity values, and retention times were documented. An aroma-active compound in the sample was confirmed if two or more panelists recognized the same aroma attribute.

2.6. GC–MS analysis

A GC–MS system (1000, Guangzhou Hexin Instrument Co., Ltd., China) equipped with a DB-5MS column (30 m × 0.32 mm I.D. ×0.25 μm; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used for analysis. The volatiles were desorbed from the SPME fiber at 250 °C in the injection port. The GC protocol, adapted from Shi et al. (Shi et al., 2020), initiated at 35 °C for 5 min, then ramped to 150 °C at 2.5 °C/min, held for 1 min, advanced to 200 °C at 8 °C/min, and held for another minute, before escalating to 250 °C at 30 °C/min and maintained for 5 min. The ion source and MS transfer line were both set at 250 °C. Helium, as the carrier gas at 1 mL/min, facilitated splitless injection. The mass spectrometer operated in EI mode at 70 eV, scanning from m/z 35 to 400.

2.7. Analysis of sugars, organic acids, and amino acids in oriental melons

Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and external standard methods were employed for quantifying sugar (Xu et al., 2011), organic acid (Flores et al., 2012), and amino acids (Zhao et al., 2021), aligning with precedent studies. The extraction process, modified from a metabolomics approach, involved grinding samples to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen using an IKA tube mill. Subsequently, 200 mg of this powder was aliquoted into 1.5 mL tubes and treated with 1 mL of a 50 % methanol solution, followed by 30 s of vortexing. A multi-tube vortexer extracted samples for 10 min, after which they were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm and 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant (300 μL) was then filtered through a 0.22 μm PTFE membrane and diluted for UPLC-MS/MS analysis.

2.8. Aroma extract dilution analysis (AEDA)

The key aroma compounds in oriental melons were identified by AEDA. Oriental melons were analyzed by GC × GC-O-TOF-MS and scored on a five-point scale (1 = weak, 3 = medium, 5 = strong) for the perceived intensity at the sniffing port. The compounds were sequentially diluted with 2n (n = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5…) by varying the splitting ratio of the GC inlet. The resultant flavor dilution (FD) factors were 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, and 512.

2.9. Qualitative and quantitative analysis

The volatile compounds were tentatively identified when the match quality was ≥700 by comparing their mass spectra and the standard data from the library NIST 14. Then, the actual retention indices (RI) were calculated using n-alkanes (C7 - C22, diluted 10,000-fold with n-hexane) as standards under the same chromatographic conditions. The compounds were determined if the difference between the calculated and published LRI values was <30.

The olfactory signatures of the volatile compounds were assessed by seasoned sensory analysts and correlated with the scent profiles listed on the Professional Aroma Compounds website (https://thegoodscentscompany.com/).

Initial semi-quantification of all identified compounds employed the internal standard 2-methyl-3-heptanone. Subsequently, external standard curve concentrations and aroma-active compounds (FD > 2) were quantified in virtual oriental melon juice, which was prepared based on the actual concentration of sugars, acids, and amino acids in two oriental melons. These target analytes were prepared at seven distinct concentration levels and mixed with the internal standard. Quantitative analysis was executed via GC–MS in the selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode, enhancing each compound's sensitivity and detection threshold. Calibration curves were formulated, predicated on the ratio of peak areas of the ions characteristic of the target compounds to those of the internal standard. Therefore, the concentration of each analyte was derived.

2.10. Calculation of OAV

The OAV of each volatile compound was calculated by the ratio of their concentration to the corresponding odor threshold in water. The odor thresholds in the water of the volatile compounds were referred from the others (Van Gemert, 2011). The volatile compounds with an OAV over 1 are regarded as the aroma-active compounds that contribute to the overall aroma of oriental melon samples.

2.11. Sensory analysis

Quantitative descriptive analysis (QDA) will be used for sensory analysis. Nine panelists underwent six one-hour training sessions over 3 weeks. During the initial training sessions, panelists generated and agreed upon a list of aroma attributes based on the aroma descriptions of the aroma actives, including fruity, grassy, sweet, mushroom, clove, almond, and cucumber. The reference compounds for the aromas are listed below: fruity (mixed fruit juices), grassy (mixed green vegetable juices), sweet (marshmallows), mushroom (2 mg/L 1-octen-3-ol), clove (2 mg/mL eugenol), almond (5 mg/mL benzaldehyde) and cucumber (cucumber slices). Samples were arranged in small weigh boats labeled with three-digit random number codes. The evaluation was repeated three times for each sensory term using a 10-point intensity scale (0 = none, 1 = very low, 9 = very high). Final sensory scores were determined by calculating the average score for the term.

In this study, all the samples were food-grade to ensure safety. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the sensory evaluation. No human ethics committee or formal documentation process is available. However, the appropriate protocols for protecting the rights and privacy of all participants were utilized during the execution of the research, such as no coercion to participate, full disclosure of study requirements and risks, written or verbal consent of participants, no release of participant data without their knowledge, and ability to withdraw from the study at any time.

2.12. Aroma recombination model and omission experiments

To confirm the contribution of 22 aroma-active substances (FD>2) in oriental melons, a recombination aroma model was created by mixing them in a water solution containing the identified sugars, organic acid, and amino acid in the concentrations naturally occurring in two oriental melon juices. The reconstituted sample was evaluated by 12 panelists using the “Sensory Analysis” method.

16 and 12 omission models for LONG4 and ZHCG were prepared to evaluate the contribution of a single compound through omission tests. The odor qualities of the reduced models were evaluated against two complete recombinants with a triangle test. All the tested samples were assigned a random four-digit code, and 12 panelists were asked to sniff the samples and select the different ones.

2.13. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis and data visualization were performed using Excel 2016 and Origin 2021 software. The Venn Diagram was drawn by the website Weishengxin (https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/). The heat map was drawn on the website Chiplot (https://www.chiplot.online/).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. E-nose response

The E-nose was used to rapidly assess the aroma characteristics of oriental melons, simulating human olfaction to provide objective overall aroma profiles and avoid the subjectivity of sensory evaluation (Wu et al., 2021). As per the radar chart shown in Fig. 1a, the response values of the sensors displayed different aroma profiles between LONG4 and ZHCG. On the whole, the response value of the sensor to the volatile smell of LONG4 was higher than that of ZHCG, suggesting that the aroma intensity of LONG4 was stronger than that of ZHCG. In particular, responses of W5S (broad response) and W1W (mainly sensitive to terpene compounds) were significantly higher in LONG4 than in ZHCG.

Fig. 1.

The analyses of E-nose data: (a) Radar fingerprint chart of the overall aroma profile in two oriental melon varieties. (b) Principal components analysis (PCA) of the E-nose data for the two oriental melon varieties.

This study applied principal components analysis (PCA) to analyze the volatile components of two oriental melon varieties, LONG4 and ZHCG. As shown in Fig. 1b, PCA revealed a clear separation between the two varieties, with LONG4 in the first and fourth quadrants and ZHCG in the second and third quadrants. The first two principal components explained 99.99 % and 0.01 % of the variance, respectively. PCA could effectively distinguish two samples, which indicated the significant differences in the aroma composition. Therefore, GC × GC-O-TOF-MS was employed to further investigate the molecular basis of these aroma differences.

3.2. Optimization of HS-SPME

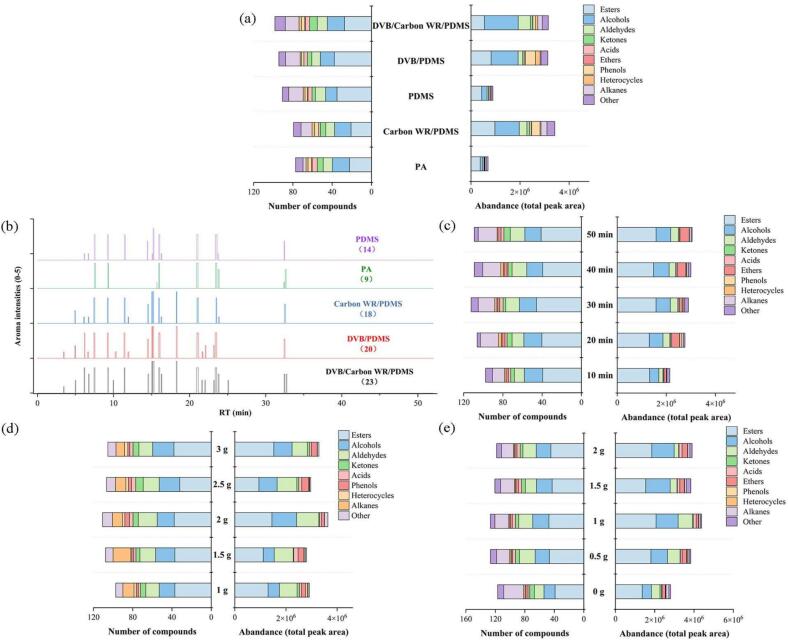

Several variables, such as the coating type of SPME Arrow fiber, sample weight, NaCl addition, and extraction time, may influence the accuracy and reliability of the application results. The optimization experiments were evaluated by examining the total number of compounds (TN) and the total peak area (TA) obtained from the total ion chromatograms. The resulting parameter optimization results are described below.

3.2.1. The effect of SPME arrow

The characteristics of the fiber coating emerged as the paramount determinant of extraction efficacy. Diverse cladding materials possess varying polarities, facilitating the selective absorption of volatile compounds in adherence to the principle of “like dissolves like” (Spietelun et al., 2010). In consideration of the volatile composition of melons, a comparative analysisi was conducted on the extraction effects of five prevalent types with different polarities. Including PA (100 μm Polyacrylate, high polarity), PDMS (100 μm Polydimethylsiloxane, low polarity), PDMS/DVB (120 μm Polydimethylsiloxane-divinylbenzene, low polarity), Carbon WR/PDMS (120 μm carbon wide range-polydimethylsiloxane, medium polarity), and DVB/Carbon WR/PDMS (120 μm divinylbenzene‑carbon wide range-polydimethylsiloxane, medium polarity) (D'Agostino et al., 2015). Regarding TN, the 120 μm DVB/Carbon WR/PDMS fiber captured 146 volatiles (as depicted in Fig. 2a), demonstrating a markedly superior performance compared to the other four types. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fiber's three distinct layers composed of unique materials, thereby enhancing the scope and capability of absorption.

Fig. 2.

Influence of different parameters on the extraction efficiency of volatile compounds in oriental melons. SPME Arrow fiber on (a) TN, TA, and (b) aroma-active compounds; (c) Extraction time; (d) Sample weight; (e) NaCl addition.

However, the carbon WR/PDMS coating had the most substantial TA, surpassing that of other SPME Arrows, particularly PA and PDMS (as shown in Fig. 2a). This could be attributed to the fact that Carbon WR/PDMS is the most apt fiber coating for extracting small molecules and acids, as evidenced in studies on volatile compounds in vegetable oils (Drabi & Jele, 2022). The single-phase coatings (100 μm PA, 100 μm PDMS) exhibit a more limited range of adsorbable fibers due to the reduced content of coating material in these single-phase configurations.

To maximize the overall extraction of aroma compounds from oriental melons without bias against certain pivotal compounds, we initially ascertained that the DVB/Carbon WR/PDMS, which captured the highest number of volatile compounds, as chosen in previous studies (Wei et al., 2021). Concurrently, we conducted an olfactory analysis of the aroma compounds extracted by the various SPME Arrows using GC × GC-O-TOF-MS and discovered that the DVB/Carbon WR/PDMS extracted the highest number of aroma-active compounds (23 species), surpassing the Carbon WR/PDMS by five species (as illustrated in Fig. 2b). This finding further substantiates our selection, which could have led to the omission of certain aroma-active compounds had Carbon WR/PDMS been chosen solely based on maximum TA. Consequently, we opted for the DVB/Carbon WR/PDMS for further HS-SPME optimization.

3.2.2. The effect of extraction time

The extraction time for HS-SPME must be balanced with the enrichment capacity and experimental efficiency (Ferracane et al., 2022). In view of the optimal extraction times for other fruits ascertained by Ma et al. (2024) and Zhang et al. (2021), a range of extraction times (10, 20, 30, 40 and 50 min) were selected for optimisation in present study. Samples were subjected to varying stirring durations to assess the extraction time. The influence of extraction time is depicted in Fig. 2c. The results revealed an initial increase in both TA and TN of compounds, followed by a plateau. It has been noted that an abbreviated extraction time can result in an uneven distribution of volatile aroma compounds across the headspace, homogenized solution, and adsorbent phase (Wang et al., 2017). While an extended extraction time facilitates greater occupancy of fiber sites by volatiles, it does not indefinitely enhance extraction efficiency (Wei et al., 2021). Consequently, a 40-min extraction time was deemed appropriate for further investigation.

3.2.3. The effect of sample weight

The extraction efficacy of HS-SPME technology, which capitalizes on the dynamic equilibrium of analytes across the headspace, sample matrix, and fiber coating, is markedly influenced by the sample quantity within the vial, correlating with the ionic strength and vapor pressure of the volatile analytes (Reyes-Garcés et al., 2018). An increase in the sample weight led to an initial rise in the TN and TA detected by GC × GC-O-TOF-MS, which then declined after reaching a peak at a 2 g sample addition, resulting in 110 species and 4.2 × 106, respectively (Fig. 2d). These findings suggest that an insufficient sample quantity results in certain molecular substances being scarce even not adsorbed by the fiber, preventing the attainment of the necessary concentration for mass spectrometry analysis. Conversely, once the fiber's absorption sites are saturated, further sample increases do not enhance volatile collection; instead, the extraction efficiency diminishes due to analyte competition on the fiber. Hence, a 2.0 g weight of oriental melon sample was selected for subsequent investigations in the forthcoming tests.

3.2.4. The effect of NaCl addition

The experiment aimed to ascertain the optimal NaCl concentration for augmenting the extraction of volatile compounds. Data revealed that extraction efficiency peaked at a 1.0 g NaCl concentration and subsequently waned with escalating NaCl concentrations (Fig. 2e), indicating that an intermediate NaCl concentration promotes the migration of volatiles from the sample matrix to the fiber coating. This enhancement is presumably attributed to volatile compounds' heightened ionic strength and diminished solubility, a phenomenon denoted as the salting-out effect (Raynie, 2023). Conversely, an overabundance of NaCl may impede the diffusion rates of volatile compounds due to electrostatic interactions (Wei et al., 2021). Consequently, a 1.0 g NaCl addition was deemed optimal.

3.3. Volatile compounds identification

The volatile constituents of LONG4 and ZHCG were delineated and characterized via GC × GC-O-TOF-MS, with identifications confirmed by mass spectrometry, retention indices, and olfactory analysis. A total of 124 volatile compounds were identified, as detailed in Table S1 and Fig. 3a, encompassing 42 esters, 29 aldehydes, 21 alcohols, eight ketones, four acids, two furans, one phenol, and four other compounds, marking a substantial increase compared to the number detected through GC–MS analysis (Yang et al., 2012). Fig. 3b reveals that LONG4 and ZHCG share the same 39 volatile compounds, with 53 and 33 unique volatiles, respectively. It indicates that while the two typical oriental melons exhibit some commonalities in their aromatic profiles, each possesses distinct characteristics.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of volatile compounds of the two oriental melon types. (a) Total number of compounds detected; (b)Venn diagram of the volatile compounds; Number (c) and concentration (d) of volatile compounds in each of oriental melon; (e) Heatmap of volatile compounds in oriental melon.

Marked disparities in the number (Fig. 3c) and concentration (Fig. 3d) of volatile compounds were discerned between the two oriental melon varieties. Compared to ZHCG, LONG4 has significantly more compounds than ZHCG, except for a slightly lower number of alcohols, furans, and other compounds and a comparable number of hydrocarbons. Furthermore, LONG4 demonstrated a significantly higher abundance of volatile compounds than ZHCG (3.07–22,770.24 μg/kg), which was markedly surpassing that of ZHCG (1.51–6154.07 μg/kg). The overall aromatic richness of LONG4 was considerably greater than that of ZHCG. The predominant compounds in LONG4 were esters, constituting 58.7 % of the total, with notable concentrations of butane-2,3-diyl diacetate (22,770.24 μg/kg), ethyl butanoate (3359.29 μg/kg), ethyl acetate (3311.11 μg/kg), ethyl hexanoate (2261.68 μg/kg), 2-methylbutyl acetate (1377.55 μg/kg), and oct-1-en-1-yl acetate (1272.77 μg/kg) and so on (Fig. 3e). These esters, ubiquitous in plants and renowned for their agreeable fruity and floral aroma, are extensively utilized in perfumes and food flavorings, potentially lending to LONG4's fruity and sweet aroma. In contrast, ZHCG displayed a more even distribution among esters (37.7 %), alcohols (30.5 %), and aldehydes (28.5 %), with higher concentrations of (E, Z)-3,6-nonadien-1-ol (4775.23 μg/kg), oct-1-en-3-ol (4543.13 μg/kg), ethyl acetate (3887.39 μg/kg), benzaldehyde (3354.52 μg/kg), and isobutyl acetate (2062.17 μg/kg), etc. (Fig. 3e). Alcohols and aldehydes such as (E, Z)-3,6-nonadien-1-ol, oct-1-en-3-ol, and benzaldehyde are recognized for their grassy, cucumber, and mushroom-like aromas. ZHCG's aroma profile, with a balanced array of esters, alcohols, and aldehydes, suggests a more complex and less fruity aroma compared to the predominantly esters-based aroma of LONG4.

3.4. Aroma-active compounds identification and aroma wheel presentation

It is important to recognize that only aroma-active compounds are essential in shaping the distinctive aroma of oriental melons, as not all volatile compounds. This study employed a synergistic approach combining sensory evaluation with GC × GC-O-TOF-MS to discern the aroma-active compounds. The GC × GC-O analysis identified 25 and 14 distinct aroma-active regions in LONG4 and ZHCG, respectively (Fig. 4a and b). A comparison of the 2D (Fig. 4c and d) and 1D (Fig. 4e and f) chromatograms of the two melon varieties reveals a significantly higher number of discernible peaks in the 2D chromatograms. Leveraging the superior resolution and sensitivity of 2D chromatography, we identified 32 aroma-active compounds through mass spectral analysis, retention indices, olfactory descriptions, and standard compound comparisons, as detailed in Table S4. Notably, six and two compounds with unique aromas were detected in LONG4 and ZHCG, respectively (unknown compounds 2, 16, 18, 19, 20, 22 in Fig. 4a; 8 and 14 in Fig. 4b), which were not detected by GC × GC-TOF-MS, potentially due to the heightened sensitivity of human olfaction over instrumental detection. Prior research has also encountered unidentified aroma compounds with chemical structures that could not be definitively elucidated owing to low concentrations and limited information from chromatographic and mass spectrometric data (Ghadiriasli et al., 2018). Future research may require more efficient extraction methods and highly sensitive analytical techniques to characterize these unknown components.

Fig. 4.

Aroma-active compounds screened by GC × GC-O-TOF-MS in two oriental melon types. GC-O aromagram of (a) LONG4 and (b) ZHCG; 2D chromatograms of (c) LONG4 and (d) ZHCG; 1D chromatograms of (e) LONG4 and (f) ZHCG; Aroma wheel of (g) LONG4 and (h) ZHCG.

The aroma profiles of distinct oriental melons were scrutinized by categorizing 32 key aroma compounds into seven groups (fruity, grassy, sweet, mushroom, clove, almond, and cucumber) based on analogous sensory characteristics, with aroma wheels constructed for each melon variety. Fig. 4g and h reveal a higher proportion of fruity and sweet aroma-active compounds in LONG4 than ZHCG, while ZHCG exhibited a greater presence of grassy aroma-active compounds. Clove and almond aromas, represented by eugenol and benzaldehyde, respectively, were detected exclusively in LONG4. Prior research has confirmed the presence of these compounds in melons, especially in aromatic menopause-type melons, where eugenol is predominantly found in the skin (Perpiñá et al., 2021). The cucumber aroma, characterized by (2E,6Z)-nona-2,6-dienal and 6-nonenal, was unique to ZHCG. This analysis underscores the significant divergence in aroma-active compounds between the two oriental melon types. In this work, both oriental melons were grown under uniform conditions in a controlled greenhouse environment and harvested at optimum ripeness, ensuring that any aromatic variation observed was entirely due to genetic differences.

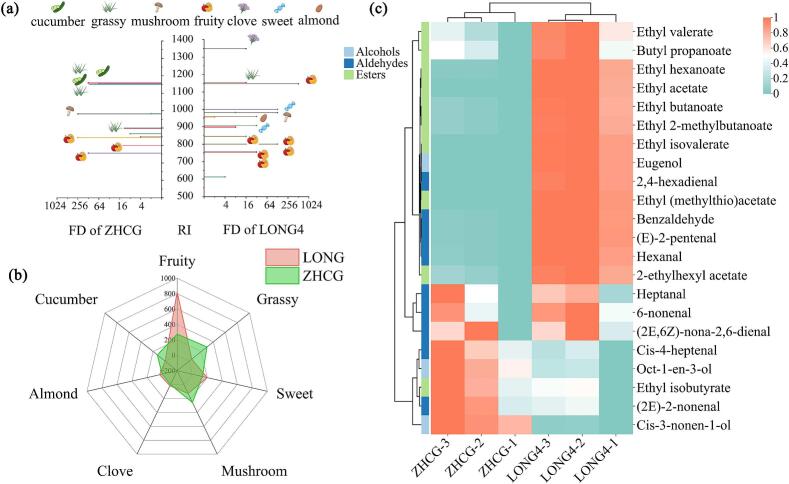

3.5. Characterization of key aroma-active compounds of oriental melons by AEDA

The FD factor quantifies the aroma contribution of each volatile compound, positively correlating with their sensory impact. AEDA analyses, as depicted in Fig. 5a and Table S4, revealed 16 and 12 key aroma-active compounds with FD > 2 in LONG4 and ZHCG, respectively. Notably, 12 aroma compounds in LONG4 exhibited FD factors ≥16, with the majority imparting fruity and sweet aromas. Specifically, 2-ethylhexyl acetate, characterized by a fruity aroma and an FD of 512, is a key contributor to the fruity aroma of oriental melons, despite its low concentration of 33.41 μg/kg. In ZHCG, 10 aroma-active compounds with FD factors ≥16 were identified, predominantly contributing grassy, cucumber, and mushroom aromas, which ultimately shape the aroma profile of ZHCG.

Fig. 5.

(a) FD factors comparison of aroma-active compounds in LONG4 and ZHCG; (b) Radar fingerprint chart (RFC) of total FD of aroma-active compounds; (c) Heat map of the concentration of aroma-active compounds (FD > 2) quantified by external standard method.

The radar fingerprint delineated by total FD factors (Fig. 5b) underscores the predominance of fruity compounds in LONG4, boasting a high total FD factor of 818, signifying a pronounced fruity aroma profile. Conversely, ZHCG exhibits a more equitable distribution of FD factors across various aroma classes, with grassy (FD = 294), fruity (FD = 274), mushroom (FD = 256), and cucumber (FD = 128) notes also substantially contributing. This distribution accentuates the multiplicity of aroma compounds and the pivotal role of their balance and intensity in shaping consumer approval and preference for fruits. Moreover, the FDs of all 8 unknowns fell below 2, implying that these compounds marginally impact the overall aroma of oriental melons.

3.6. Quantitation of key aroma-active compounds and OAV analysis

In the oriental melons, 22 aroma-active compounds with FD > 2 were further quantified using the external standard method (Table 1), with correlation coefficients for the linear equations varying between 0.9583 and 0.9996. Compared to ZHCG, LONG4 exhibited higher levels of ester aroma-active compounds. Among these compounds, ethyl acetate (9425.53 μg/kg), ethyl (methylthio) acetate (571.49 μg/kg), ethyl isobutyrate (52.32 μg/kg), ethyl hexanoate (51.59 μg/kg), ethyl valerate (34.59 μg/kg), ethyl butanoate (29.54 μg/kg), ethyl 2-methylbutanoate (27.71 μg/kg) were identified as the predominant aroma-active compounds in LONG4. These aroma-active compounds mainly contribute to the fruity and sweet aroma of LONG4. In particular, ethyl acetate is the predominant ester in LONG4, consistent with previous research (Chen, Zhou, et al., 2016). In contrast, a higher level of aldehydes and alcohols was observed in ZHCG, with notable concentrations of oct-1-en-3-ol (159.80 μg/kg), (2E)-2-nonenal (65.53 μg/kg), cis-3-nonen-1-ol (41.67 μg/kg), and cis-4-heptenal (14.20 μg/kg), which predominantly contribute to the mushroom and grassy aroma. Besides, aroma-active compounds such as 2,4-hexadienal (1.91 μg/kg), ethyl isovalerate (3.83 μg/kg), eugenol (4.80 μg/kg) were found at low concentrations, which may be due to their lower odor thresholds (Van Gemert, 2011). These compounds may interact synergistically with high-concentration components, potentially shaping the aroma profile of oriental melons and enriching their olfactory complexity.

Table 1.

Concentrations and AOVs of aroma-active compounds (FD > 2) quantified by external standard methods.

| No. | Compound | Calibration equations | R2 | Concentration (μg/kg) |

Threshold (mg/kg) | OAV |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LONG4 | ZHCG | LONG4 | ZHCG | |||||

| 1 | (2E)-2-nonenal | y = 0.5366×-0.01032 | 0.9996 | 58.79 ± 3.4 | 65.53 ± 5.03 | 0.00002 | 2939.67 | 3276.67 |

| 2 | Butyl propanoate | y = 1.5236×-0.002503 | 0.9994 | 12.37 ± 1.1 | 10.5 ± 0.92 | 0.2 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| 3 | Ethyl isovalerate | y = 0.5917×-0.001827 | 0.9986 | 3.83 ± 0.31 | 0 ± 0 | 0.00001 | 383.00 | 0.00 |

| 4 | Oct-1-en-3-ol | y = 3.922×-0.01253 | 0.9986 | 120.55 ± 9.51 | 159.8 ± 14.47 | 0.0015 | 80.37 | 106.53 |

| 5 | Ethyl 2-methylbutanoate | y = 0.6294×-0.002614 | 0.9985 | 27.71 ± 2.19 | 8.6 ± 0.75 | 0.000013 | 2131.54 | 661.54 |

| 6 | Ethyl hexanoate | y = 0.3477×-0.002197 | 0.9966 | 51.59 ± 4.93 | 7 ± 0.82 | 0.0022 | 23.45 | 3.18 |

| 7 | Hexanal | y = 0.3628× + 0.002039 | 0.9965 | 281.55 ± 17.98 | 63.07 ± 5.71 | 0.0045 | 62.57 | 14.01 |

| 8 | Heptanal | y = 0.9456× + 0.00031 | 0.9947 | 26.89 ± 2 | 26.6 ± 2.8 | 0.004 | 6.72 | 6.65 |

| 9 | 2,4-hexadienal | y = 0.7507×-0.000422 | 0.9939 | 1.91 ± 0.14 | 0 ± 0 | 0.000035 | 54.57 | 0.00 |

| 10 | Cis-3-nonen-1-ol | y = 0.8474×-0.005386 | 0.9936 | 12.37 ± 1.1 | 41.67 ± 3.95 | 0.0001 | 123.70 | 416.67 |

| 11 | Ethyl isobutyrate | y = 0.1979×-0.001939 | 0.9914 | 52.32 ± 5.05 | 59.4 ± 5.5 | 0.000089 | 587.83 | 667.42 |

| 12 | Cis-4-heptenal | y = 1.8224×-0.00252 | 0.9905 | 11.48 ± 0.89 | 14.2 ± 1.6 | 0.0000087 | 1319.54 | 1632.18 |

| 13 | Ethyl butanoate | y = 0.1949× + 0.001437 | 0.9904 | 29.54 ± 2.64 | 8.6 ± 0.75 | 0.003 | 9.85 | 2.87 |

| 14 | Benzaldehyde | y = 0.9325× + 0.02212 | 0.9886 | 311.05 ± 18.34 | 54.17 ± 4.77 | 0.75 | 0.41 | 0.07 |

| 15 | Ethyl (methylthio) acetate | y = 0.01894× + 0.000615 | 0.9857 | 571.49 ± 39.22 | 0 ± 0 | 0.025 | 22.86 | 0.00 |

| 16 | Ethyl acetate | y = 0.002712× + 0.009266 | 0.9793 | 59,425.53 ± 6365.91 | 3259.17 ± 283.36 | 0.005 | 11,885.11 | 651.83 |

| 17 | (E)-2-pentenal | y = 0.07836× + 0.00608 | 0.9698 | 394.32 ± 20.46 | 86.4 ± 6.49 | 0.31 | 1.27 | 0.28 |

| 18 | (2E,6Z)-nona-2,6-dienal | y = 0.3917×-0.00288 | 0.9644 | 10.42 ± 0.75 | 10.17 ± 1.17 | 0.00001 | 1042.33 | 1016.67 |

| 19 | Ethyl valerate | y = 0.6871×-0.01723 | 0.96 | 34.59 ± 2.96 | 25.97 ± 2.6 | 0.0058 | 5.96 | 4.48 |

| 20 | 6-nonenal | y = 0.514×-0.002088 | 0.9595 | 21.86 ± 1.2 | 20.43 ± 1.9 | 0.000005 | 4371.33 | 4086.67 |

| 21 | 2-ethylhexyl acetate | y = 0.1532× + 0.000112 | 0.9564 | 14.38 ± 1.03 | 5.07 ± 0.71 | 0.1515 | 0.09 | 0.03 |

| 22 | Eugenol | y = 0.2754×-0.001299 | 0.9583 | 4.8 ± 0.39 | 0 ± 0 | 0.0018 | 2.67 | 0.00 |

The OAVs of 22 aromatic active substances were calculated to explore further their contribution to the overall aroma profile of Oriental melons. As shown in Table 1, 19 compounds exhibited OAV ≥ 1, signifying their substantial contribution to the distinctive aroma of oriental melons. This consistency underscores the complementary validation potential of AEDA and OAV. However, it is worth noting that the FD and OAV for benzaldehyde, 2-ethylhexyl acetate, and butyl propanoate were not consistent; in particular, 2-ethylhexyl acetate showed a very high FD factor (512) in LONG4, but the OAV value was only 0.094. Such inconsistencies between AEDA and OAV or ROAV outcomes have been previously observed in Jiashi muskmelon juice (Pang, Guo, et al., 2012) and coconut water (Li, Wang, Jiang, et al., 2024). The disparities between these two methods may stem from their distinct application principles. OAV, relying on instrumental analysis, swiftly ascertains characteristic aroma components but overlooks the different matrix's influence on aroma compound volatility and thresholds and inter-odorant dynamics within mixtures, such as inhibition, synergy, and antagonism (Li, Wang, Xiao, et al., 2024). AEDA, which combines instrumental and sensory analyses, offers enhanced precision and reliability. Although it relies on professional evaluators, which increases experimental costs and time (Pang, Guo, et al., 2012), it effectively avoids certain key aroma compounds that are missed due to threshold differences or interactions between the compounds, such as 2-ethylhexyl acetate (FD = 512) found in our research.

3.7. Sensory analysis, aroma recombination, and omission experiments

The QDA analysis reveals that LONG4 exhibits significantly higher intensities of fruity and sweet aromas compared to ZHCG, highlighting the prominence of these characteristics in the aroma profile of LONG4 (Fig. 6a). Conversely, ZHCG is characterized by a more pronounced cucumber and grassy aroma, with a comparatively weaker fruity aroma. The significant sensory differences observed between the two are consistent with the variance in the aroma-active compounds identified in the preceding text.

Fig. 6.

(a) Aroma profiles of LONG4 and ZHCG; (b) Overall aroma profile of LONG4 (solid line) and its aroma recombination model (dashed line). (c) Overall aroma profile of ZHCG (solid line) and its aroma recombination model (dashed line).

To confirm the contribution of 22 aroma-active substances (FD > 2) and to identify key differential odorant compounds in oriental melons, aroma recombinants were prepared and then compared with the original oriental melon juices. Previous studies showed that sugars, organic acids, and amino acids significantly affect the release of volatile compounds from fruits such as melons, influencing aroma perception (Aboshi et al., 2022; Baldwin et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2022). Therefore, to maximally replicate the release of aroma-active compounds in oriental melons and ensure precise aroma contribution assessment of aroma-active compounds, we created a virtual oriental melon juice for aroma recombination and omission experiments. It was based on the actual concentrations of eight major sugars (0.78–22.48 mg/g), two acids (0.01–0.12 mg/g), and ten amino acids (0.02–0.27 mg/g) in two oriental melon varieties, as determined by LC-MS/MS. This matrix was used for quantitative analysis, aroma recombination and omission experiments. The detailed list of compounds is presented in Table S2. Despite the minor differences in sensory evaluation, the overall aroma profile of the recombination model closely mirrored the of two original oriental melons, further confirming the accuracy of the identification and quantitation of the main aroma-active compounds of oriental melons. Uncovering whether the subtle differences between the recombined model and real samples stem from non-volatiles' impact on the release of aroma-active compounds is an issue we need to address in the future.

16 and 12 omission models for LONG4 and ZHCG were designed by omitting individual compounds, respectively. Using the recombination model as a guide, they were assessed using triangle test. As shown in Table 2, a total of 8 and 7 omission models for LONG4 and ZHCG respectively showed significant differences (p < 0.05). Specifically, ethyl hexanoate and ethyl valerate were the key odor-active compounds in LONG4 (p < 0.001), imparting “sweet” and “fruity” sensory attributes. 2-ethylhexyl acetate, ethyl acetate, ethyl butanoate, and ethyl isovalerate played a decisive role in the overall aroma (p < 0.01). Furthermore, significant differences (p < 0.05) were also observed when 2,4-hexadienal and hexanal were absent. Despite the limited research on aroma-active compounds in oriental melons, ethyl butanoate and hexanal have been identified as key aroma-active compounds in muskmelons (Pang, Guo, et al., 2012), while ethyl hexanoate, ethyl acetate, and 2,4-hexadienal have been established as significant volatile compounds in climacteric oriental melons with intense aroma (S. Chen, Cao, et al., 2016). Similarly, cis-3-nonen-1-ol, cis-4-heptenal, oct-1-en-3-ol, (2E)-2-nonenal and heptanal demonstrated noticeable impacts on the aroma of ZHCG (p < 0.001), contributing to fresh, green, mushroom and grassy aroma. Ethyl isobutyrate and Ethyl butanoate were also observed with a significant impact (p < 0.05). Among them, (2E)-2-nonenal, heptanal, ethyl butanoate were also reported as the aroma-active compounds in muskmelon (Pang, Chen, et al., 2012; Pang, Guo, et al., 2012). It is evident that ethyl hexanoate, ethyl acetate and 2,4-hexadienal, (2E)-2-nonenal, heptanal, and ethyl butanoate were the representative aroma-active compounds in thin-skinned melons. Interestingly, there were no significant differences when some compounds were omitted, with LONG4 and ZHCG consisting of 8 and 5 species, respectively. This may be attributed to the masking effects of other key aroma-active compounds with similar aromas or the mutual masking among these compounds themselves on each other, which renders them less perceptible to olfactory detection (Li, Wang, Xiao, et al., 2024). The above results are an important guide for developing different aroma types of melon-flavored fragrances for use in the cosmetic and food industries. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that consumer preference is significantly influenced by aroma-active compounds (Li et al., 2025). These compounds can be leveraged to predict consumer preference and serve as molecular markers to guide future aroma - breeding programs in oriental melons.

Table 2.

Results of the omission experiments for recombinant models.

| Model | Odorants omitted from the Recombination model |

No.a | Significanceb | Model | Odorants omitted from the Recombination model |

No.a | Significanceb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LONG4–1 | Ethyl hexanoate | 11 | *** | ZHCG-1 | (2E)-2-nonenal | 10 | *** |

| LONG4–2 | Ethyl valerate | 10 | *** | ZHCG-2 | Cis-3-nonen-1-ol | 10 | *** |

| LONG4–3 | Ethyl butanoate | 9 | ** | ZHCG-3 | Cis-4-heptenal | 10 | *** |

| LONG4–4 | 2-ethylhexyl acetate | 9 | ** | ZHCG-4 | Oct-1-en-3-ol | 10 | *** |

| LONG4–5 | Ethyl isovalerate | 9 | ** | ZHCG-5 | Heptanal | 8 | * |

| LONG4–6 | Ethyl acetate | 9 | ** | ZHCG-6 | Ethyl butanoate | 8 | * |

| LONG4–7 | Hexanal | 8 | * | ZHCG-7 | Ethyl isobutyrate | 8 | * |

| LONG4–8 | 2,4-hexadienal | 8 | * | ZHCG-8 | (2E,6Z)-nona-2,6-dienal | 7 | ns |

| LONG4–9 | (E)-2-pentenal | 7 | ns | ZHCG-9 | Butyl propanoate | 7 | ns |

| LONG4–10 | Cis-3-nonen-1-ol | 6 | ns | ZHCG-10 | 6-nonenal | 6 | ns |

| LONG4–11 | Ethyl isobutyrate | 5 | ns | ZHCG-11 | Ethyl 2-methylbutanoate | 5 | ns |

| LONG4–12 | Ethyl (methylthio) acetate | 4 | ns | ZHCG-12 | Ethyl (methylthio)acetate | 5 | ns |

| LONG4–13 | Cis-4-heptenal | 4 | ns | ||||

| LONG4–14 | Eugenol | 4 | ns | ||||

| LONG4–15 | Benzaldehyde | 3 | ns | ||||

| LONG4–16 | Oct-1-en-3-ol | 2 | ns |

Number of correct responses in the triangle test.

Significance: “*”, significant (p ≤ 0.05); “**”, highly significant (p ≤ 0.01); “***”, very highly significant (p ≤ 0.001); “ns”, no significant difference.

4. Conclusion

In this study, combined HS-SPME extraction parameters optimization and sensomics approaches, 124 volatile compounds were identified in two representative oriental melon varieties, of which 32 were aroma-active compounds, with significant differences in the types and amounts of volatile compounds between the two varieties. We accurately quantified 22 aroma-active compounds with FD > 2 using GC–MS and the external standard method. Three compounds were found with OAV < 1, among which 2-ethylhexyl acetate exhibited an FD value as high as 512, further highlighting the reliability of AEDA. By recombining 16 and 14 aroma-active compounds with FD > 2, and the principal sugars, acids, and amino acids measured in LONG4 and ZHCG, we successfully reconstructed the aroma profiles of the two oriental melon products. Omission tests further confirmed that ethyl hexanoate, ethyl valerate, 2-ethylhexyl acetate, ethyl acetate, ethyl isovalerate, ethyl butanoate, 2,4-hexadienal and hexanal were key active-aroma compounds contributing to the overall fruity and sweet aroma of LONG4, while cis-3-nonen-1-ol, cis-4-heptenal, oct-1-en-3-ol, (2E)-2-Nonenal, heptanal, ethyl isobutyrate and ethyl butanoate were crucial for the overall grassy and cucumber aroma of ZHCG. The results provide essential data for subsequent research and breeding programs to improve or preserve oriental melon quality.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xiaohui Li: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology. Chen Zhang: Validation, Formal analysis. Simeng Li: Validation, Investigation. Hongping Wang: Investigation. Peiwen Yu: Validation, Investigation. Hua Shao: Investigation. ShenhaoWang: Resources, Investigation. Huaisong Wang: Supervision, Resources. Fen Jin: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program of CAAS (CAAS-ASTIP-IQSTAP-02) under the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, the Young Talents Program under the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China, Basic Research Operating Funds (1610072024105), and National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFD1200100).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2025.102517.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Aboshi T., Narita K., Katsumi N., Ohta T., Murayama T. Removal of C9-aldehydes and -alcohols from melon juice cysteine addition. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2022;102(13):6131–6137. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.11965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin E.A., Goodner K., Plotto A. Interaction of volatiles, sugars, and acids on perception of tomato aroma and flavor descriptors. Journal of Food Science. 2008;73(6):S294–S307. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Cao S.X., Jin Y.Z., Tang Y.F., Qi H.Y. The relationship between CmADHs and the diversity of volatile organic compounds of three aroma types of melon (Cucumis melo) Frontiers in Physiology. 2016;7:254. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Zhou X.Z., Wu Y.F., Chen Y., Zhang L., Zhang W.G. Impact of Cucurbita and Cucumis melo rootstocks on aroma volatile compounds in oriental melon fruits. Research on Crops. 2016;17:777. doi: 10.5958/2348-7542.2016.00131.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino M.F., Sanz J., Sanz M.L., Giuffrè A.M., Sicari V., Soria A.C. Optimization of a Solid-Phase Microextraction method for the Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry analysis of blackberry (Rubus ulmifolius Schott) fruit volatiles. Food Chemistry. 2015;178:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabi N., Jele H.H. Optimisation of headspace solid-phase microextraction with comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography-time of flight mass spectrometry (HS-SPME-GC x GC-ToFMS) for quantitative analysis of volatile compounds in vegetable oils using statistical experimental design. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2022;110, Article 104595 doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2022.104595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esteras C., Rambla J.L., Sánchez G., López-Gresa M.P., González-Mas M.C., Fernández-Trujillo J.P.…Picó M.B. Fruit flesh volatile and carotenoid profile analysis within the Cucumis melo L. species reveals unexploited variability for future genetic breeding. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2018;98(10):3915–3925. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.8909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferracane A., Manousi N., Tranchida P.Q., Zachariadis G.A., Mondello L., Rosenberg E. Exploring the volatile profile of whiskey samples using solid-phase microextraction Arrow and comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A. 2022;1676:463241. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2022.463241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores P., Hellín P., Fenoll J. Determination of organic acids in fruits and vegetables by liquid chromatography with tandem-mass spectrometry. Food Chemistry. 2012;132(2):1049–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.10.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghadiriasli R., Wagenstaller M., Buettner A. Identification of odorous compounds in oak wood using odor extract dilution analysis and two-dimensional gas chromatography-mass spectrometry/olfactometry. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2018;410(25):6595–6607. doi: 10.1007/s00216-018-1264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkbride Joseph H. 1993. Biosystematic Monograph of the Genus Cucumis (Cucurbitaceae): Botanical Identification of Cucumbers and Melons. [Google Scholar]

- Li X.H., Wang H.S., Zhang C., Li S., Wang H.P., Yu P.W.…Jin F. Unveiling the key aroma-active volatiles influencing consumer preferences in typical oriental melon varieties by molecular sensory science methods. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2025;143 doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2025.107527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.J., Zeng X.Q., Song H.L., Xi Y., Li Y., Hui B.W.…Li J. Characterization of the aroma profiles of cold and hot break tomato pastes by GC-O-MS, GC x GC-O-TOF-MS, and GC-IMS. Food Chemistry. 2023;405, Article 134823 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.L., Wang R.X., Xiao T., Song L.B., Xiao Y., Liu Z.H.…Zhu M.Z. Unveiling key odor-active compounds and bacterial communities in Fu brick tea from seven Chinese regions: A comprehensive sensomics analysis using GC-MS, GC-O, aroma recombination, omission, and high-throughput sequencing. Food Research International. 2024;196, Article 114978 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.114978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.Z., Wang T., Jiang H.W., Lan T., Xu L.L., Yun Y.H., Zhang W.M. Comparative key aroma compounds and sensory correlations of aromatic coconut water varieties: Insights from GC x GC-O-TOF-MS, E-nose, and sensory analysis. Food Chemistry: X. 2024;21, Article 101141 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D., Lin T.B., Zhao H.Y., Li Y.G., Wang X.Q., Di S.S.…Jiao R. Development and comprehensive SBSE-GC/Q-TOF-MS analysis optimization, comparison, and evaluation of different mulberry varieties volatile flavor. Food Chemistry. 2024;443, Article 138578 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.138578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manousi N., Kalogiouri N., Ferracane A., Zachariadis G.A., Samanidou V.F., Tranchida P.Q.…Rosenberg E. Solid-phase microextraction arrow combined with comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography-mass spectrometry for the elucidation of the volatile composition of honey samples. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2023;415(13):2547–2560. doi: 10.1007/s00216-023-04513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics National per capita consumption of main food products. 2022. https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01&zb=A0D0K&sj=2022 Retrieved from. Accessed April 8, 2024.

- Pang X.L., Chen D., Hu X.S., Zhang Y., Wu J.H. Verification of aroma profiles of Jiashi muskmelon juice characterized by odor activity value and gas chromatography-Olfactometry/detection frequency analysis: Aroma reconstitution experiments and omission tests. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2012;60(42):10426–10432. doi: 10.1021/jf302373g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang X.L., Guo X.F., Qin Z.H., Yao Y.B., Hu X.S., Wu J.H. Identification of aroma-active compounds in Jiashi muskmelon juice by GC-O-MS and OAV calculation. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2012;60(17):4179–4185. doi: 10.1021/jf300149m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perpiñá G., Roselló S., Esteras C., Beltrán J., Monforte A.J., Cebolla-Cornejo J., Picó B. Analysis of aroma-related volatile compounds affected by “Ginsen Makuwa” genomic regions introgressed in “Vedrantais” melon background. Scientia Horticulturae. 2021;276, Article 109664 doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raynie D.E. Enhancing extractions by salting out. LCGC North America. 2023;41(7):262–265. doi: 10.56530/lcgc.na.ax9490j4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Garcés N., Gionfriddo E., Gómez-Ríos G.A., Alam M.N., Boyaci E., Bojko B.…Pawliszyn J. Advances in solid phase microextraction and perspective on future directions. Analytical Chemistry. 2018;90(1):302–360. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b04502. 7b04502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi C.H., Yang F., Yan L.C., Wu J.H., Bi S., Liu Y. Characterization of key aroma-active compounds in fresh and vacuum freeze-drying mulberry by molecular sensory science methods. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2024;133, Article 106387 doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2024.106387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J.D., Wu H.B., Xiong M., Chen Y.J., Chen J.H., Zhou B.…Huang Y. Comparative analysis of volatile compounds in thirty nine melon cultivars by headspace solid-phase microextraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Food Chemistry. 2020;316, Article 126342 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spietelun A., Pilarczyk M., Kloskowski A., Namiesnik J. Current trends in solid-phase microextraction (SPME) fibre coatings. Chemical Society Reviews. 2010;39(11):4524–4537. doi: 10.1039/c003335a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gemert L.J. 2011. Compilations of odour threshold values in air, water and other media (2nd ed). The odour threshold values in water. Chapter 2. [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Duan C.Q., Shi Y., Zhu B.Q., Javed H.U., Wang J. Free and glycosidically bound volatile compounds in sun-dried raisins made from different fragrance intensities grape varieties using a validated HS-SPME with GC-MS method. Food Chemistry. 2017;228:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.01.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Chen X.Y., Zhang C., Li X.H., Yue N., Shao H.…Jin F. Discrimination and characterization of volatile flavor compounds in fresh oriental melon after Forchlorfenuron application using electronic nose (E-nose) and headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (HS-GC-IMS) Foods. 2023;12(6) doi: 10.3390/foods12061272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S.H., Xiao X.M., Wei L.J., Li L.S., Li G.C., Liu F.H.…Zhong Y. Development and comprehensive HS-SPME/GC–MS analysis optimization, comparison, and evaluation of different cabbage cultivars (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata L.) volatile components. Food Chemistry. 2021;340, Article 128166 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S., Yang J., Dong H., Liu Q., Li X., Zeng X., Bai W. Key aroma compounds of Chinese dry-cured Spanish mackerel (Scomberomorus niphonius) and their potential metabolic mechanisms. Food Chemistry. 2021;342 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Zhang H.J., Song H.L. Simultaneous determination of monosaccharide and disaccharide contents in foods by high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Food Science. 2011;32(12):234–238. https://next.cnki.net/middle/abstract?v=NK8hpUzgeRXwgSH8AzBGnjLGXgHWJ9LUoA4LYJzKdxJTU2nPMiucxJAEiiWyzl1NjfCbj1przXw0NF-fpSK-oiGjx_aP8z895a9f03bUC7tsQNTgKVXfomkkybjmghWeO1LqxVbVb-ZbsufFLvsFcwF6QJmC0zuH6cKUTw64OwcBETdt-W_dutR-YmGGvS8I&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS&scence=null [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Yu Z.Y., Xu Y.Q., Shao Q. Analysis of volatile compounds from oriental melons (Cucumis melo L.) using headspace SPME coupled with GC-MS. Advances in Chemistry Research Ii. 2012;Pts 1-3 doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.554-556.2102. 554-556, 2102-2105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Tang C.C., Jiang B.Z., Mo X.Y., Wang Z.Y. Optimization of HS-SPME for GC-MS analysis and its application in characterization of volatile compounds in sweet potato. Molecules. 2021;26(19):5808. doi: 10.3390/molecules26195808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.R., Wu P.Y., Li K., He W., Chang D.M., Peng X.D. Breeding of a new oriental melon cultivar Tianmei 101. Zhongguo Gua-cai. 2022;35(09):104–107. doi: 10.16861/j.cnki.zggc.2022.0221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L.Q., Zhao X.D., Xu Y.P., Liu X.W., Zhang J.R., He Z.Y. Simultaneous determination of 49 amino acids, B vitamins, flavonoids, and phenolic acids in commonly consumed vegetables by ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chemistry. 2021;344, Article 128712 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M., Li T., Yang F., Cui X.Y., Zou T.T., Song H.L., Liu Y. Characterization of key aroma-active compounds in Hanyuan Zanthoxylum bungeanum by GC-O-MS and switchable GC × GC-O-MS. Food Chemistry. 2022;385, Article 132659 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D.D., Zhang Q., Wu C.E., Li T.T., Tu K. Change of soluble sugars, free and glycosidically bound volatile compounds in postharvest cantaloupe fruit response to cutting procedure and storage. Scientia Horticulturae. 2022;295, Article 110863 doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2021.110863. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.