Abstract

Background

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has significantly reshaped Primary Health Care (PHC), offering various possibilities and complexities across all functional dimensions. The objective is to review and synthesize available evidence on the opportunities, challenges, and requirements of AI implementation in PHC based on the Primary Care Evaluation Tool (PCET).

Methods

We conducted a systematic review, following the Cochrane Collaboration method, to identify the latest evidence regarding AI implementation in PHC. A comprehensive search across eight databases- PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Science Direct, Embase, CINAHL, IEEE, and Cochrane was conducted using MeSH terms alongside the SPIDER framework to pinpoint quantitative and qualitative literature published from 2000 to 2024. Two reviewers independently applied inclusion and exclusion criteria, guided by the SPIDER framework, to review full texts and extract data. We synthesized extracted data from the study characteristics, opportunities, challenges, and requirements, employing thematic-framework analysis, according to the PCET model. The quality of the studies was evaluated using the JBI critical appraisal tools.

Results

In this review, we included a total of 109 articles, most of which were conducted in North America (n = 49, 44%), followed by Europe (n = 36, 33%). The included studies employed a diverse range of study designs. Using the PCET model, we categorized AI-related opportunities, challenges, and requirements across four key dimensions. The greatest opportunities for AI integration in PHC were centered on enhancing comprehensive service delivery, particularly by improving diagnostic accuracy, optimizing screening programs, and advancing early disease prediction. However, the most challenges emerged within the stewardship and resource generation functions, with key concerns related to data security and privacy, technical performance issues, and limitations in data accessibility. Ensuring successful AI integration requires a robust stewardship function, strategic investments in resource generation, and a collaborative approach that fosters co-development, scientific advancements, and continuous evaluation.

Conclusions

Successful AI integration in PHC requires a coordinated, multidimensional approach, with stewardship, resource generation, and financing playing key roles in enabling service delivery. Addressing existing knowledge gaps, examining interactions among these dimensions, and fostering a collaborative approach in developing AI solutions among stakeholders are essential steps toward achieving an equitable and efficient AI-driven PHC system.

Protocol.

Registered in Open Science Framework (OSF) (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HG2DV).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12875-025-02785-2.

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence, Primary Health Care, AI in Primary Health Care, AI in Health, AI in PHC, Systematic review

Introduction

Primary Health Care (PHC) has been a central focus of global health initiatives since the Alma-Ata declaration in 1978 [1, 2], which recognized it as the foundation for achieving universal health coverage and addressing primary health needs equitably [3]. This vision, reinforced by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2008 [1, 2], promotes PHC as essential for providing comprehensive care, including prevention, health promotion, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliation [4, 5]. Despite its political endorsement, implementing PHC in practice has faced significant challenges [6]. These include limited resources, unequal access to care, and increasing workloads for healthcare providers [7, 8]. The rapid pace of technological advancements further exacerbates these challenges [9, 10], while simultaneously offering opportunities to enhance the delivery of PHC and advance universal health coverage [11–13].

Among these advancements, the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in healthcare, particularly within PHC, is both undeniable and transformative [14, 15]. PHC is uniquely positioned to drive and benefit from the AI revolution due to its interconnectedness with the entire health system and continuous patient relationships [15, 16]. AI has evolved from an academic concept to a practical tool that is reshaping various sectors, including healthcare [17]. AI, a field within computer science, simulates human cognitive functions, including learning, reasoning, and knowledge storage [18, 19]. Its key branches include Machine Learning (ML), Deep Learning (DL), and Natural Language Processing (NLP) [20, 21]. These enable systems to learn from data, make decisions, and perform tasks traditionally requiring human intelligence [22, 23]. For example, ML can predict patient outcomes from electronic health records (EHR), DL can analyze medical images to assist in diagnostics, and NLP can automate clinical documentation [24–26].

AI has significant potential to address PHC challenges by improving clinical decisions, enhancing diagnosis accuracy, and supporting disease surveillance [27–30]. For instance, AI can improve access to care, facilitate early disease detection, automate routine clinical workflows, and support personalized treatment plans [23, 28, 31–34]. This technology can improve the quality, efficiency, and effectiveness of healthcare services [35], while it has also posed considerable challenges [11, 36]. Ethical concerns, privacy issues, professional liability, data quality, and integration difficulties have been highlighted as major obstacles [32, 37–39]. Overcoming these challenges requires interdisciplinary collaboration, developing a concrete plan by policymakers and administrators, dedicated healthcare professional education, and ongoing research and development to support effective AI integration into PHC [30, 37, 39–42].

Recent reviews, such as those by [27, 43–45], have explored the challenges and benefits of AI implementation in PHC settings. While these studies emphasize the transformative potential of AI and highlight the importance of addressing its challenges [27, 43–45], they lack a comprehensive framework for evaluating AI integration across core functions of PHC. To the best of our knowledge, no systematic review comprehensively addresses the challenges, opportunities, and requirements associated with AI implementation within PHC using a structural and standard framework.

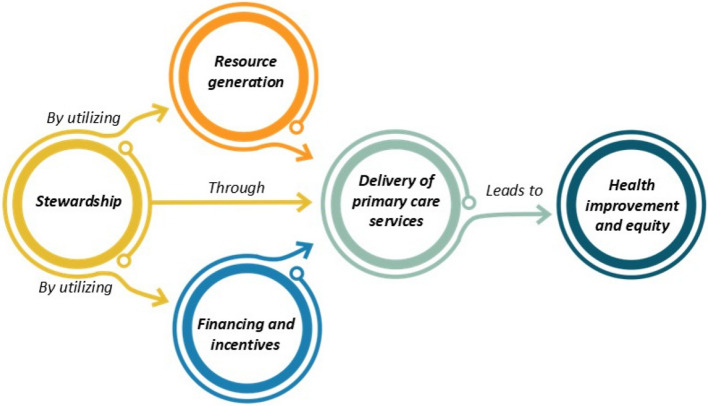

This study filled this gap by mapping current evidence on AI implementation in PHC and providing structured insights based on the Primary Care Evaluation Tool (PCET). Developed by the WHO, PCET evaluates PHC systems across four core dimensions—stewardship, resource generation, financing, and service delivery—and four key service characteristics: access to services, continuity of services, coordination of delivery, and comprehensiveness [46] (See Fig. 1). The interaction between these functions ultimately leads to health improvement and equity, with stewardship playing a leadership role in utilizing financing and resource generation to create conditions for effective service provision [47, 48]. PCET offers a holistic perspective on healthcare systems, capturing organizational, policy-related, and service-level functions essential for understanding the complex dynamics of PHC. By applying this framework, this study systematically identifies and organizes opportunities, challenges, and requirements for AI integration into PHC. This structured approach enhances the contextual relevance of the findings and provides actionable insights for policymakers and healthcare providers, distinguishing this study from previous reviews.

Fig. 1.

The framework of the Primary Care Evaluation Tool (PCET)

Research question

In this context, this review aims to answer the following question: What are the key opportunities, challenges, and requirements associated with AI implementation in PHC systems across the core dimensions of stewardship, resource generation, financing, and service delivery?

Methods

A systematic review was conducted, following the Cochrane methods for systematic reviews [49] and adhering to the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis” (PRISMA 2020) guidelines [50, 51]. We registered the protocol in the Open Science Framework (OSF) (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HG2DV).

Search strategy

A comprehensive list of search terms and MESH terms, along with a structured search strategy, was formulated under the guidance of the SPIDER framework (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, and Research type) [52, 53]. This process was carried out in consultation with an experienced academic librarian (ES). SPIDER is an alternative search strategy tool that is better suited for qualitative and exploratory research compared to the PICO framework [53, 54]. Unlike PICO, which is primarily designed for clinical and interventional studies and focuses on Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome [53], SPIDER is tailored to capture diverse perspectives and experiences, particularly in social sciences and healthcare settings where contextual factors are critical. The flexibility and specificity of SPIDER make it a valuable tool for identifying relevant studies in exploratory research [54, 55]. Given the nature of our review, which explores opportunities, challenges, and requirements for AI integration in PHC, SPIDER offered a more inclusive and appropriate approach for identifying relevant studies.

Following pilot searches, we conducted the main search across eight databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Science Direct, Embase, CINHAL, IEEE, and Cochrane, in January 2024. The search covered studies published between 2000 and 2024. While the core search terms remained consistent across all databases, minor adjustments were made to account for the unique indexing and functionality of each database. For instance, some databases prioritize MESH terms, while others use broader keyword indexing. These adjustments were necessary to optimize the search strategy for each database and ensure comprehensive and unbiased results. (The detailed search strategy is presented in Supplemental file S1.)

Study selection/ study screening

All citations retrieved during the search were exported to the Covidence online collaborative tool [56] where duplicates were removed using both automated and manual functions. The initial screening of titles and abstracts was conducted independently by three reviewers (FY, MN, NA) working in pairs, using clearly defined inclusion criteria. Full-text assessments of potentially eligible studies were performed by the same reviewer pairs. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using Cohen’s kappa for different reviewer pairs. The weighted average kappa score across all screening phases was κ = 0.7245, indicating substantial agreement, while for full-text screening, Cohen’s kappa was κ = 0.92, demonstrating almost perfect agreement. Discrepancies at any stage were discussed, and unresolved conflicts were adjudicated by a fourth reviewer (RD) to ensure consistent decision-making throughout the process.

As part of this review, opinion-based publications, including editorials and commentary articles, were included alongside empirical studies. These sources provided unique value by capturing expert insights and highlighting current challenges, research gaps, and future directions for AI integration in PHC. These sources offered nuanced perspectives on complex and emerging issues, such as ethical considerations and policy and social implications of AI, which may not always be fully addressed in empirical research [57, 58]. Including these sources enriched our review by providing a broader understanding of the discourse surrounding AI integration in PHC, including both empirical evidence and expert analysis. However, these sources were not weighted equally in the analysis. While empirical studies were the primary basis for identifying themes and drawing conclusions, expert opinions were used to selectively complement and contextualize findings, particularly in areas where empirical evidence was scarce or evolving. This approach ensured that the conclusions were driven primarily by empirical data while benefiting from additional expert insights where relevant.

To mitigate potential biases in the inclusion of qualitative studies, several measures were implemented. First, a comprehensive search strategy was developed in consultation with an experienced academic librarian to ensure that no relevant studies were overlooked. Second, inclusion and exclusion criteria were clearly defined and rigorously applied during the screening process (the eligibility criteria are presented in Table 1). Third, any discrepancies in the screening process were resolved through discussion among multiple reviewers, with conflicts adjudicated by a fourth reviewer (RD). These measures ensured consistency and transparency throughout the selection process, minimizing subjective bias and enhancing the reliability of the findings.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria guided by SPIDER

| SPIDER | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| S: Sample | Any kind of sample of the population | No limitation |

| PI: Phenomenon of Interest |

Studies that used AI, AI-based technologies (e.g. websites, platforms, initiatives, devices, etc.), AI-related algorithms (e.g., machine learning, deep learning, natural language processing, etc.), as an intervention, in the PHC systems (e.g. Health Posts, Community Health Centers), Primary-level clinics (e.g., Public Health Networks, Rural Health Clinics, Family Physicians’ Offices) |

Studies that used AI or AI algorithms for analysing health records or that delivered care in specialist or hospital settings or non-health settings |

| D: Design |

The studies, including questionnaires or surveys, interviews, observation, focus groups, case studies, cohort studies, longitudinal, cross-sectional, randomized controlled trials, pilot or feasibility studies, text, and opinion (e.g., editorial, commentary) Published in English |

Using AI in developing the study methodology and framework Published in a language other than English and no translation readily available |

| E: Evaluation | Results related to the concept of “Challenges”, “Opportunities”, and “Requirements” of AI Implementation in PHC, including outcomes related to practice efficiency and patient outcomes (both clinical and service utilization), where available | No relevant outcome from the list |

| R: Research Type | Research types, including qualitative studies, quantitative studies, and mixed methods studies | No development methodology, including study protocol, reviews (e.g., systematic, scoping, rapid, etc.), blog publication, conference publication (e.g., congress, annual meeting, symposium, workshops), abstract poster, thesis, and dissertation |

Regarding the textual expert opinions, in addition to the mentioned measures, we applied strict inclusion criteria to ensure that only expert commentaries published in reputable, peer-reviewed journals were considered. Additionally, these sources were assessed for relevance and alignment with the study’s objectives, and their contributions were critically analyzed rather than directly equated with empirical findings. This distinction was maintained throughout the thematic synthesis to preserve methodological rigor.

Data extraction and synthesis

A structured extraction grid, designed to align with the objectives of this review, was used to guide the data extraction process. To ensure reliability and comprehensiveness, a pilot test was conducted on 10% of the articles (n = 11), as a common practice in systematic reviews to refine the extraction process and achieve consistency across reviewers [59]. This approach allowed the reviewers to identify and address any ambiguities or inconsistencies in the data extraction. Two reviewers (FY, RD) independently tested the Excel form, compared their results, and reached a consensus before proceeding with the remaining extraction. The remaining data extraction was performed by a single reviewer (FY) under the direct supervision of a senior researcher (RD) to ensure accuracy and consistency [49]. The entire process of data extraction, including the pilot test and the final review, was closely monitored by the senior researcher to maintain rigor. The extracted data elements included descriptive information (authors, year of publication, title, aim, study location, study design, study population, and intervention type) and qualitative information (opportunities, challenges, and requirements).

Additionally, we synthesized extracted qualitative data through a combination of a framework approach and thematic analysis. Initially, key themes were identified and subsequently organized within the PCET. This framework, as described in the introduction, was selected due to its capacity to provide a comprehensive understanding of PHC systems by addressing their core functions and characteristics. By mapping the identified themes to the dimensions and characteristics outlined in the PCET framework, we were able to systematically categorize the opportunities, challenges, and requirements for AI integration into PHC. Additionally, an extra category was considered to account for items that did not align with the predefined dimensions of the PCET framework. This ensured that all relevant data were appropriately categorized, contributing to a more inclusive and comprehensive synthesis.

Study quality assessment

The methodological quality of the included publications was assessed by applying the Johanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Checklist critical appraisal tool, which is designed to evaluate various study types. Each checklist is tailored to a specific research design and includes the research question, appropriateness of the methodology, data collection processes, and interpretation of the findings. The checklists aim to ensure the internal validity, reliability, and applicability of the included studies across multiple domains. For empirical studies, relevant JBI tools were applied according to their respective study designs (e.g., qualitative, cross-sectional, cohort). Additionally, for textual expert opinions, we utilized a specific JBI checklist designed for assessing text and opinion-based sources. This approach ensured that all included sources, whether empirical or expert-driven, were critically appraised for methodological rigor. Although expert opinion pieces were not weighted equally with empirical studies, applying a structured quality assessment process enabled a more systematic evaluation of their credibility and relevance. Each checklist item was scored as ‘Yes,’ ‘No,’ or ‘Unclear,’ depending on whether the study met the specified criteria [60, 61].

To ensure consistency, two researchers (RD, FY) independently assessed 20% of the included studies (n = 22) and resolved any discrepancies through discussion. The remaining studies were appraised by a single reviewer (FY) under the direct supervision of a senior researcher (RD). This approach, commonly employed in systematic reviews, allowed us to balance the thoroughness of the quality assessment process while maintaining the rigor and reliability of the process [49].

Results

Selection of publications

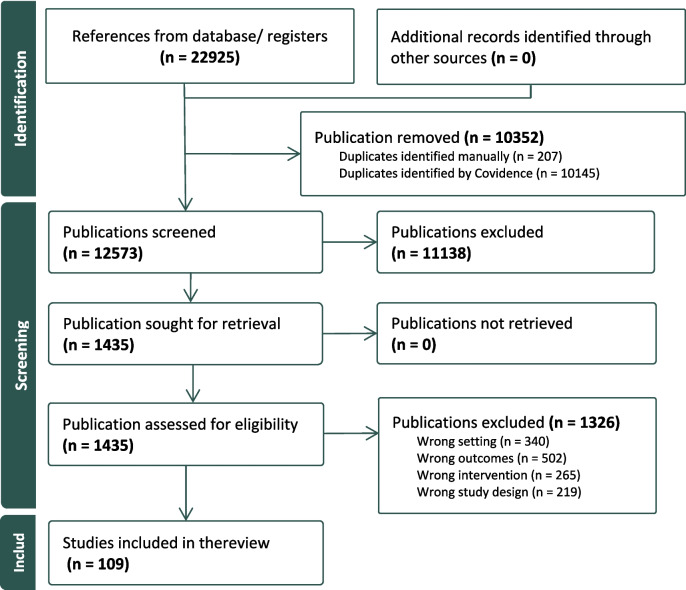

The study selection process is illustrated in Fig. 2, which presents the PRISMA flow diagram. A total of 22,925 references were identified through databases. After removing duplicates, 12,573 publications were eligible for title and abstract screening. Full texts were retained and consecutively assessed on eligibility from 1,435 publications. Based on the inclusion criteria, a total of 109 publications were included in the data analysis and synthesis of this review.

Fig. 2.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Diagram

Characteristics of studies

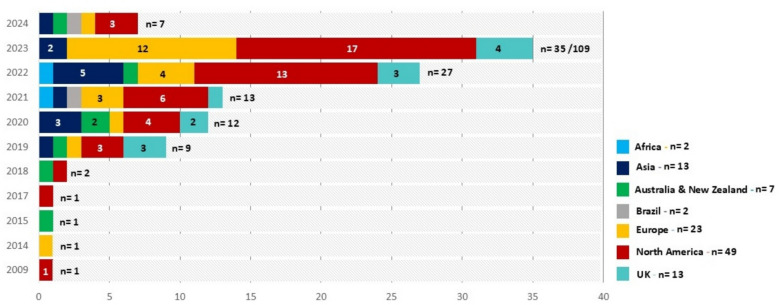

The characteristics of the 109 included publications are outlined in the supplemental file (Supplemental file S2). Although the study period spanned from 2000 to 2024, no studies published between 2000 and 2009 met the inclusion criteria. For the publications in 2009 [62], 2014 [63], 2015 [64], and 2017 [65], only one study was included for each respective year. In 2018, the number of publications increased to two [66, 67], and a significant rise has been observed since 2019 (n = 9, 8%) [23, 28, 68–74]. We observed an escalation in total publications from 2020 (n = 12, 11%) [75–86] up until 2023, which accounted for the highest number of publications (n = 35, 32%) [87–121]. For 2024 (up to January), we identified 7 (6.5%) publications [122–128]. This growing trend reflects the increasing interest and development in the integration of AI into PHC systems, particularly in recent years.

Geographically, the majority of articles were published in North America (n = 49, 44%), with contributions from the United States (n = 39) [15, 16, 23, 34, 62, 65, 66, 68, 72, 78, 80–82, 87, 88, 91, 93, 94, 96, 103, 106, 111, 116, 118, 123, 125, 126, 129–139] and Canada (n = 10) [33, 95, 105, 113, 114, 121, 140–143]. Europe followed as the second-largest contributor (n = 36, 33%), with publications originating from the European Union (n = 23) [63, 70, 75, 89, 90, 99–102, 108, 110, 115, 117, 119, 120, 127, 144–150] and the United Kingdom (n = 13) [28, 69, 71, 77, 83, 92, 98, 107, 109, 151–154]. Asia also contributed a notable share (n = 13, 12%) [74, 76, 79, 84, 104, 112, 122, 155–160], while Australia and New Zealand accounted for 7 studies [64, 67, 73, 85, 86, 124, 161]. Limited contributions were also observed from Brazil (n = 2) [128, 162], and Africa (n = 2) [163, 164].

This distribution may reflect a publication bias, where research from high-income countries is more frequently published in indexed journals, or it may indicate that AI adoption in PHC is less extensively studied or implemented in certain regions, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Or this might reflect differences in resource availability, research priorities, or technological readiness in adopting AI in PHC systems. Figure 3 visually represents the distribution of publications across regions and years, highlighting the dominance of North America and Europe in the literature. The observed increase in publications underscores a growing recognition of AI’s potential to enhance PHC systems and the accelerating pace of research and implementation in this field.

Fig. 3.

The distribution of publications across regions and years

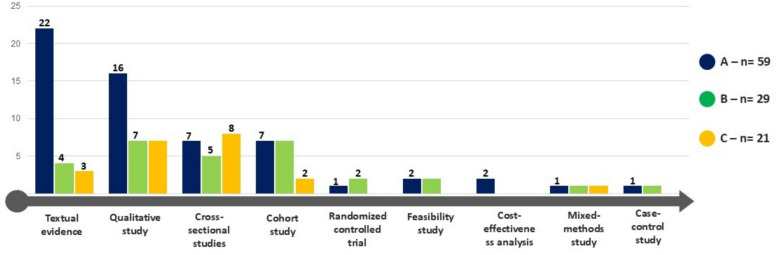

The included studies employed a diverse range of study designs, reflecting the methodological breadth of the research field (see Fig. 4). These designs included qualitative studies (n = 30) [28, 62, 68, 70, 81, 82, 85, 86, 91, 95, 97, 100, 103, 107, 109, 110, 112, 113, 115, 121, 125, 128, 136, 138, 140, 142, 143, 148–150], textual expert opinion (n = 29) [15, 16, 23, 33, 34, 66, 69, 73, 76, 78–80, 90, 93, 94, 101, 117, 118, 131, 132, 135, 139, 145–147, 151, 152, 161, 164], cross-sectional studies (n = 19) [63, 64, 67, 74, 88, 102, 106, 111, 116, 120, 122, 123, 137, 141, 157–159, 162, 163]. Additional designs included cohort studies (n = 16) (65, 71, 72, 83, 84, 87, 96, 98, 99, 114, 129, 134, 144, 153, 155, 156), feasibility studies (n = 5) [77, 89, 105, 119, 130], randomized trials (n = 3) [127, 133, 160], mixed-methods (n = 3) [92, 104, 108], cost evaluation (n = 2) [124, 154], and case–control studies (n = 2) [75, 126]. The number of participants in these studies varied widely, ranging from the smallest study (n = 5) [115], to the largest study (n = 175 million) [163].

Fig. 4.

Visual summary of the study designs and their corresponding methodological quality assessments

The methodological quality of the studies

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the JBI Checklist, with scores of all 109 studies provided in the online supplemental table S3. Overall, the majority of the publications (n = 59, 54%) were classified as high-quality (“A”), with scores exceeding 70%. for 29 publications (26%), while 21 studies (19%) were classified as low quality (“C”), with scores below 50%. Importantly, no studies were excluded based on quality scores. To ensure that lower-quality studies did not disproportionately influence key findings, we critically examined whether major themes emerged primarily from high-quality sources. Our analysis confirmed that the most frequently cited themes were predominantly supported by high- and moderate-quality studies. While lower-quality studies contributed to some aspects of the synthesis, their impact was carefully considered, and their findings were interpreted with caution.

Figure 4 provides a comprehensive visual summary of the study designs and their corresponding methodological quality assessments. This visualization underscores the diversity in study types and the overall quality distribution within the selected publications.

Framework- thematic analysis

To address the study’s objectives, opportunities, challenges, and requirements for AI integration in PHC were extracted and analyzed from 109 studies. The PCET framework was utilized to organize PHC into four core dimensions: stewardship, resource generation, financing and incentives, and service delivery. The findings were further refined through thematic analysis, which enabled the identification of key themes and sub-themes within each dimension. Out of the 109 studies, 103 explored opportunities, identifying 15 main themes and 40 sub-themes across the PCET dimensions. Similarly, 82 studies highlighted challenges, classified into 16 main themes and 38 sub-themes. Additionally, 102 studies investigated requirements for AI implementation, which were grouped into 17 main themes and 46 sub-themes. The detailed results of the thematic analysis are provided in Supplemental Tables S4, S5, and S6.

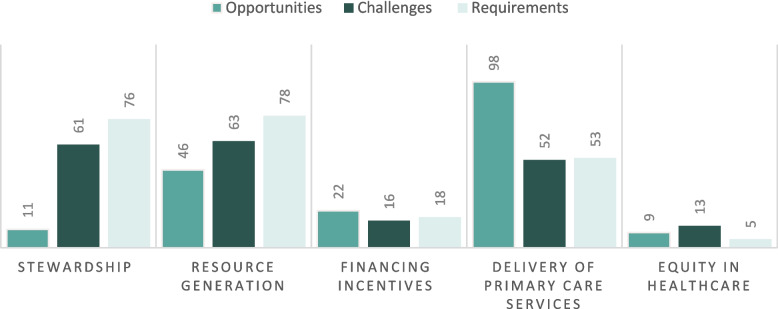

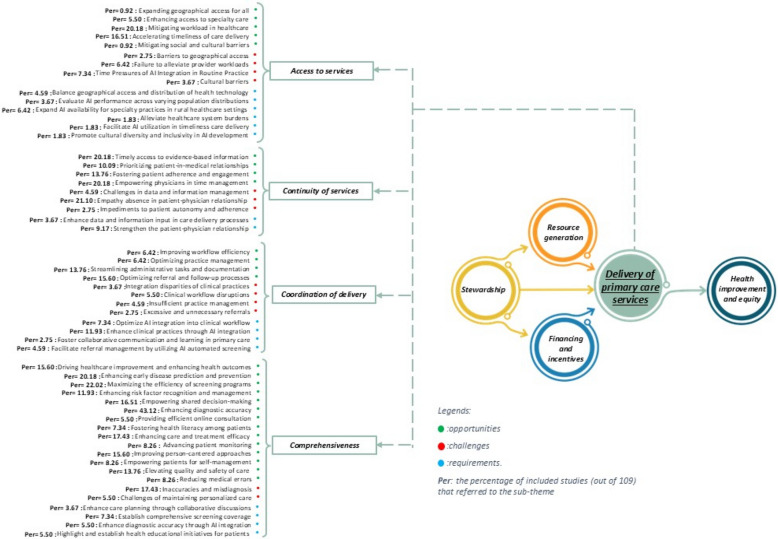

Figure 5 illustrates the numerical distribution of studies across these dimensions, classified into opportunities, challenges, and requirements. The findings show that the “Delivery of primary care services” garnered the most attention, with 98 studies emphasizing opportunities, 52 addressing challenges, and 53 outlining requirements. In contrast, “Equity in healthcare” was the least explored, with only 9 studies discussing opportunities, 13 addressing challenges, and 5 focusing on requirements. These variations reflect differing levels of research focus and interest across the dimensions.

Fig. 5.

The numerical findings of the study

In the following sections, the results are presented by dimension, each accompanied by visualizations that summarize the key findings and the distribution of themes. These visualizations provide a clear depiction of the thematic structure, illustrating how the main themes and sub-themes are organized within each PCET dimension. We acknowledge the potential overlaps in the results due to the interconnected nature of PHC dimensions, the cross-cutting impact of AI-driven interventions, and the way studies report their findings. Since AI applications in PHC often influence multiple domains simultaneously, some themes inherently span more than one dimension. As a result, categorizations were made based on the most dominant and contextually relevant aspect of each sub-theme. This structured presentation ensures a comprehensive understanding of how AI-related opportunities, challenges, and requirements align with the core dimensions of PHC.

Stewardship

As a key governance function, stewardship involves regulation, health policy, priority setting, performance evaluation, and consumer protection at various levels of the health system [46, 165]. Given its fundamental role in overseeing and guiding AI adoption in PHC, this dimension includes aspects related to policy formulation, regulatory frameworks, ethical considerations, and public engagement. The opportunities, challenges, and requirements were mapped based on their relevance to governance and oversight mechanisms.

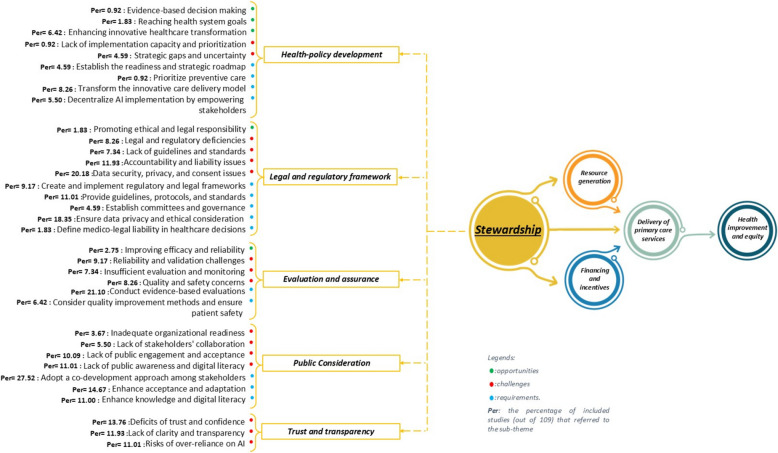

A small proportion of studies (n = 11, 10%) highlighted the opportunities within the stewardship dimension, categorized into three main themes and five sub-themes. The most prominent opportunity was Health policy development, emphasizes innovative healthcare transformation [28, 70, 78, 105, 112, 145, 146] (6.42%), which includes integrating PHC and public health through AI, personalized medicine, and clinical data [70, 145, 146]. Additionally, it was linked to achieving health system goals [112, 158] (1.83%), and promoting evidence-based decision-making [145] (0.92%). The legal and regulatory framework emphasized fostering ethical and legal responsibility [112, 138] (1.83%), while evaluation and assurance highlighted improving the efficacy and reliability of healthcare processes [116, 120, 146] (2.75%).

A substantial number of studies (n = 61, 56%) highlighted challenges related to this dimension, categorized into five main themes and 16 sub-themes. The legal and regulatory framework accounted for the highest proportion, highlighting critical issues such as data security, privacy, and consent [66, 68, 80, 81, 86, 90, 92, 95, 104–107, 117, 125, 135, 139, 140, 146, 148, 150, 151, 164] (20.18%). Other major legal challenges included accountability and liability [68, 79, 85, 90, 95, 108, 120, 125, 135, 139, 150, 151, 164] (11.93%), legal and regulatory deficiencies [16, 68, 69, 79, 81, 85, 90, 121, 153] (8.26%), and the absence of clear guidelines and standards [16, 69, 79, 81, 99, 123, 156, 162] (7.34%). Trust and transparency emerged as the second most significant, emphasizing deficits in trust and confidence [69, 78, 82, 89–92, 107, 108, 125, 135, 138, 140, 149, 151] (13.76%), lack of clarity and transparency in AI decision-making processes [68, 69, 76, 79, 86, 90, 117, 138–140, 143, 146, 164] (11.93%), and risks of over-reliance on AI [28, 66, 73, 82, 85, 88, 95, 113, 115, 118, 150, 162] (11.01%). Furthermore, the consideration and preparation highlighted barriers such as a lack of public awareness and digital literacy[34, 69, 74, 78, 81, 82, 91, 113, 118, 132, 138, 153] (11.01%), insufficient public engagement and acceptance [34, 73, 77, 80, 100, 101, 109, 138, 140, 151, 162] (10.09%) and limited stakeholders’ collaboration [16, 68, 109, 113, 152, 153] (5.50%).

A significant proportion of studies (n = 76, 70%) concentrated on the requirements needed to address challenges and support AI integration in PHC, classified into five main themes and 17 sub-themes. The most frequently cited requirement was public consideration, with adopting a co-development approach among stakeholders [15, 16, 33, 34, 62, 69, 71, 78, 80, 92, 93, 95, 97, 101, 105, 109, 110, 115, 117, 120, 121, 124, 125, 132, 133, 139, 140, 143, 146, 150] being the most emphasized strategy(27.52%). Complementary requirements included enhancing acceptance and adaptation (74, 82, 85, 90, 91, 95, 97, 100, 104, 108, 112, 121, 128, 133, 139, 157) (14.67%) and improving public knowledge and digital literacy [16, 69, 74, 78, 80, 81, 91, 102, 109, 125, 140, 146] (11.00%). The evaluation and assurance highlighted conducting evidence-based evaluations [28, 72, 74, 83, 86, 89–91, 98, 101, 104, 106, 109, 117, 118, 121, 125, 127, 137, 140, 143, 148, 153] (21.10%) as a critical requirement, alongside adopting quality improvement methods while ensuring patient safety [15, 28, 86, 98, 118, 149, 153] (6.42%). Within the legal and regulatory framework, key requirements included ensuring data privacy and ethical considerations [16, 28, 33, 66, 68, 69, 73, 78, 86, 90, 92, 95, 117, 118, 142, 143, 146, 148, 151, 164] (18.35%), developing guidelines, protocols, and standards [28, 34, 69, 78, 79, 86, 97, 109, 118, 123, 134, 146] (11.01%), and creating robust regulatory and legal frameworks [79, 86, 90, 95, 109, 118, 121, 146, 150, 164] (9.17%). Requirements within trust and transparency included establishing trust and confidence [28, 74, 78–80, 86, 92, 95, 101, 103, 107, 108, 116, 117, 143] (12.84%), fostering human-centered approaches [66, 68, 69, 78, 79, 82, 85–87, 91, 95, 108, 121, 123, 125, 149, 151] (14.68%). (For more details, see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Opportunities, challenges, and requirements of AI implementation within the stewardship

Resource generation

Resource generation sustains health services by balancing diverse resources (e.g., physical infrastructure, human resources, and knowledge/ information) across different levels and geographical areas of the health system [46]. Thematic analysis identified opportunities, challenges, and requirements within this dimension, classified into three main themes and multiple sub-themes.

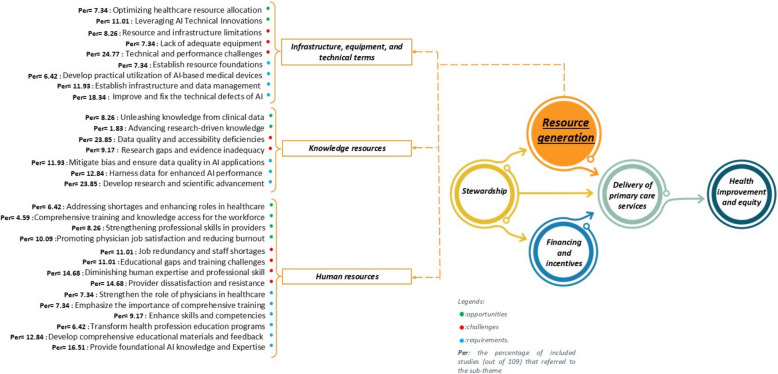

Emphasis on resource generation opportunities was evident in 42% of studies (n = 46), organized into 3 main groups and 9 sub-groups. Infrastructure, equipment, and technical terms emerged as a key theme, emphasizing leveraging AI technical innovations [15, 34, 64, 77, 85, 101, 118, 123, 135, 140, 148, 163] (11.01%) and the potential of AI to optimize resource allocation [34, 77, 78, 101, 108, 117, 122, 149] (7.34%). In the knowledge resources domain, AI was identified as a powerful tool for extracting knowledge from clinical data [62, 68, 69, 78, 79, 110, 112, 123, 145] (8.26%) and advancing research-driven knowledge [147, 149] (1.83%). Under the theme of human resources, AI presents opportunities to enhance physician job satisfaction while reducing burnout [23, 79, 89, 92, 95, 102, 105, 111, 132, 133, 135] (10.09%), improving provider skills [69, 72, 99, 110, 124, 132, 146, 156, 162] (8.26%), and addressing workforce shortages [63, 69, 81, 105, 107, 124, 127] (6.42%).

Challenges in resource generation were discussed in 58% of studies (n = 63), classified into 3 main themes and 9 sub-themes. Infrastructure, equipment, and technical terms were a major concern, including technical performance issues [15, 16, 28, 73, 76, 77, 80–83, 85, 86, 93, 105, 107, 115, 117, 120, 121, 136, 138–140, 143, 144, 146, 150] (24.77%) with the existence of potential bias in AI algorithms impacting AI tool functions[15, 28, 73, 80–83, 85, 86, 93, 117, 121, 138–140, 143, 144, 146]. Additionally, resource and infrastructure limitations [81, 93, 105, 125, 133, 148, 154, 156, 162] (8.26%) and insufficient equipment availability[108, 122, 125, 140, 148, 153, 156, 161] (7.34%) were identified as significant barriers to AI implementation. In the knowledge resources category, deficiencies in data quality and accessibility[16, 28, 69, 78–80, 86, 87, 90, 93, 95, 118, 122, 127, 135, 138, 140–144, 151, 153, 156, 163, 164] (23.85%) were among the most frequently cited challenges, along with research gaps and evidence inadequacy [66, 91, 105, 107, 122, 127, 135, 140, 153, 162] (9.17%). The human resources theme underscored critical barriers such as diminishing human expertise and professional skills [28, 66, 68, 73, 79, 81, 85, 89, 103, 113, 117, 129, 135, 140, 148, 157] (14.68%) and provider dissatisfaction and resistance [68, 73, 79, 82, 85, 91, 105, 117, 121, 139, 140, 146, 148, 150, 153, 157] (14.68%). Job redundancy and staff shortages [69, 79, 85, 93, 113, 127, 135, 138, 148, 150, 152, 157] (11.01%), and educational gaps [79–81, 102, 103, 105, 121, 124, 130, 139, 150, 157] (11.01%) were also cited.A slightly higher number of studies (n = 78, 72%) addressed the requirements of enhancing this dimension, which were organized into 3 main themes and 13 sub-themes. Within infrastructure, equipment, and technical terms, addressing technical defects and improving AI systems [16, 62, 73, 77, 86, 90, 92–94, 101, 106, 115, 117, 122, 125, 133, 146, 153, 155, 156] (18.35%), emerged as the most critical requirement. Establishing infrastructure and data management systems [16, 28, 34, 78, 83, 93, 101, 109, 113, 128, 141, 143, 146] (11.93%) and developing utilization strategies for AI-based medical devices [76, 84, 127–129, 150, 153] (6.42%) were also highlighted as other priorities. In the knowledge resources category, developing research and scientific advancements [16, 75, 77, 80, 86, 89, 90, 92, 93, 97–99, 107, 123, 124, 126–132, 134, 135, 144, 153, 161] (23.85%), harnessing data for enhanced AI performance [28, 75, 86, 90, 91, 102, 112, 122, 125, 141, 143, 146, 163, 164] (12.84%), and ensuring data quality and mitigating bias [28, 34, 78, 86, 118, 121, 125, 140, 143, 146, 153, 162, 164] (11.93%). Finally, human resources emphasized providing foundational AI knowledge and expertise [33, 34, 68, 78, 82, 93, 95, 100–102, 109, 110, 133, 139, 147, 153, 157, 161] (16.51%), developing comprehensive educational materials and feedback mechanisms [16, 33, 95, 97, 108, 112, 113, 121, 133, 139, 148–150, 166] (12.84%), enhancing skills and competencies [69, 79, 113, 123, 132, 133, 135, 139, 146, 150] (9.17%), transforming health professional education programs (79, 81, 113, 139, 146, 161, 164) (6.42%) to prepare the workforce for effective AI integration. (For more details, see Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Opportunities, challenges, and requirements of AI implementation within the resource generation

Financing and incentives

Financing and incentives refer to the mobilization, accumulation, and allocation of funds to meet both individual and collective health needs within the system [46].

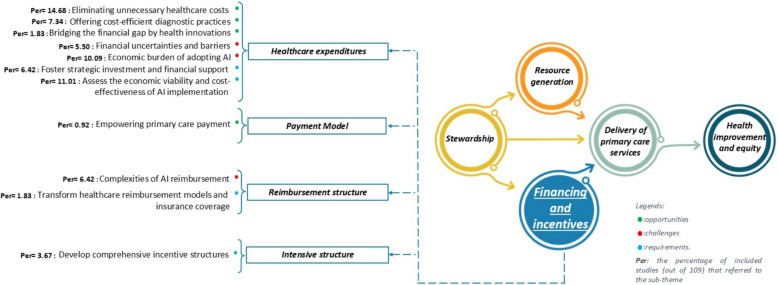

A small proportion of studies (n = 22, 20%) explored AI opportunities for financing and incentives in PHC, leading to 2 main and 4 sub-themes. Healthcare expenditures emerged as the most significant area of focus, highlighting AI’s potential to eliminate unnecessary healthcare costs [68, 72, 105, 112, 120, 124, 129, 137, 142, 146, 149, 150, 155, 156, 158, 167] (14.68%) and support cost-efficient diagnostic practices [72, 103, 112, 122, 124, 129, 149, 154, 156] (7.34%). These advancements contribute to enhancing the cost-effectiveness of PHC services [72, 103, 122, 124, 129] and reducing financial waste [68, 105, 112, 146, 158, 167], facilitating a more sustainable financial model for PHC.

The challenges within this dimension were least frequently discussed in included studies (n = 16, 15%), encompassing 2 primary and 2 sub-themes. Under healthcare expenditures, concerns were raised regarding the economic burden of adopting AI technologies [73, 76, 81, 90, 93, 105, 120, 131, 135, 149, 161] (10.09%) and financial uncertainties and barriers [69, 76, 120, 125, 131, 135] (5.50%). These challenges primarily stem from the high costs of integrating advanced systems into existing infrastructures [69, 120, 131, 135]. Within the reimbursement structure, studies pointed to the complexity of AI reimbursement processes [16, 28, 73, 120, 131, 135, 150] (6.42%) as a critical issue.

A limited number of studies (n = 18, 17%) addressed the requirements for addressing financial and incentive-related challenges, categorized into 3 primary and 4 sub-themes. Within healthcare expenditures, fostering strategic investment and financial support [15, 34, 73, 91, 95, 120, 121, 128, 131, 140, 148, 164] (11.01%) was identified as a critical requirement for enabling a sustainable environment for AI adoption in PHC. Additionally, assessing the economic viability and cost-effectiveness of AI implementation [73, 90, 91, 98, 103, 112, 148, 150] (7.34%) was emphasized as a key step to ensuring affordability and feasibility. Under the incentive structure theme, developing comprehensive incentive structures [78, 112, 128, 150] (3.67%) was noted as an important step in motivating stakeholders and aligning their goals with AI adoption strategies [131]. Finally, within the reimbursement structure, studies highlighted the necessity of transforming healthcare reimbursement models and insurance coverage [73, 131] (1.83%) to accommodate AI-driven. (For more details, see Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Opportunities, challenges, and requirements of AI implementation within the financing and incentives

Delivery of primary care services (see Fig. 9)

Fig. 9.

Opportunities, challenges, and requirements of AI implementation within the delivery of primary care services

Service delivery involves the production and provision of health interventions, covering preventive, curative, and rehabilitative care for individuals, as well as population-level services like health education through public and private institutions. It consists of four key components: access to services, ensuring patients receive timely care at the right place; continuity, enabling coordinated short-term and sustained long-term care across providers; coordination, promoting collaboration within and across care levels; and comprehensiveness, ensuring the provision or arrangement of a full spectrum of care services [46].

A substantial majority of studies (n = 98, 90%) underscored opportunities in the delivery of primary care services, categorized into 4 main themes and 27 sub-themes. Comprehensiveness emerged as the most significant theme, emphasizing AI’s role in enhancing diagnostic accuracy [15, 23, 28, 34, 65, 66, 69, 71–73, 75, 79, 81, 83, 84, 87–89, 91, 96, 99, 101, 105, 108, 110, 116–118, 120, 122, 124, 129, 131–133, 135, 138, 141, 148, 149, 151–154, 163, 166, 168] (43.12%), maximizing the efficiency of screening programs [15, 72, 84, 87, 92, 97, 98, 103, 105, 110, 114, 122, 124, 126, 129, 137, 142, 145, 150, 151, 154–156, 159] (22.02%), improving early disease prediction and prevention [28, 64, 66, 71, 72, 76, 78, 87, 112, 113, 117, 122, 126, 137, 140, 143, 145, 151, 158, 161, 166] (20.18%), and enhancing patient care and treatment efficacy [34, 66, 71, 79, 94, 96, 99, 100, 105, 110, 112, 118, 124, 137, 145, 146, 152, 163, 168] (17.43%). Opportunities within the access to services focused on mitigating workload in healthcare [28, 62, 67, 68, 72, 73, 77, 87, 89, 92, 101, 104, 106, 112, 118–120, 135, 145, 146, 148, 159] (20.18%) and accelerating the timeliness of care delivery [33, 68, 79, 89, 92, 96, 100, 101, 108, 120, 126, 132, 137, 146, 150, 159, 162, 163] (16.51%). The continuity of services revealed the importance of timely access to evidence-based information [15, 28, 62, 69, 73, 79, 81, 89, 92, 93, 98, 100, 101, 108, 110, 111, 115, 118, 123, 138, 140, 162] (20.18%), empowering physicians in time management[15, 23, 33, 63, 68, 77, 79, 92, 96, 100, 101, 113, 115, 117, 120, 123, 126, 135, 138, 146, 150, 162] (20.18%), and fostering patient adherence and engagement [15, 70, 79, 82, 89, 97, 112, 113, 129, 135, 142, 145, 146, 156, 158] (13.76%). Lastly, coordination of delivery included AI’s role in optimizing referral and follow-up processes [15, 23, 33, 72, 92, 100, 110, 116, 122, 125, 129, 132, 150, 151, 153, 156, 159] (15.60%) and streamlining administrative tasks and documentation [15, 23, 34, 62, 77, 79, 85, 94, 101, 110, 111, 113, 118, 132, 135] (13.76%).

Fifty-two studies (48%) discussed the challenges of this dimension, which were categorized into 4 main groups and 13 sub-groups. The continuity of services theme highlighted the lack of empathy in patient-physician relationships [15, 34, 66, 68, 76, 78, 79, 82, 85, 89–91, 93, 95, 100, 113, 121, 125, 130, 140, 148, 150, 151] (21.10%) as a major concern, alongside difficulties in managing data and information [80, 82, 100, 115, 119] (4.59%). The comprehensiveness theme underscored inaccuracies and misdiagnoses in AI systems [28, 68, 71, 82, 85, 87, 88, 93, 95, 99–101, 107, 115, 118, 132, 148, 149, 157] (17.43%) and challenges in maintaining personalized care [66, 68, 121, 138, 143, 151] (5.50%). Under the access to services theme, key barriers included the time pressures of integrating AI into routine practice [81, 89, 123–125, 127, 148, 153] (7.34%) and the failure to alleviate provider workloads [68, 81, 89, 105, 117, 125, 127] (6.42%). Disruptions in clinical workflows [73, 100, 107, 118, 128, 156] (5.50%) and clinical workflow disruptions (5.5%) were discussed as problematic issues in delivering coordinated services.

Requirements for improving primary care service delivery were highlighted in 53 studies (49%), categorized into 4 main groups and 16 sub-groups. The coordination of delivery theme emphasized enhancing clinical practices through AI applications [28, 85, 91, 95, 98, 99, 115, 120, 148–151, 161] (11.93%) and optimizing AI integration into clinical workflows[28, 96, 97, 108, 143, 144, 146, 153] (7.34%). Within the continuity of services theme, strengthening the patient-physician relationship [80, 86, 87, 95, 107, 113, 125, 140, 143, 147] (9.17%) was noted as a key requirement. In the comprehensiveness category, establishing comprehensive screening coverage [74, 98, 103, 126, 128, 144, 155, 156] (7.34%) and enhancing diagnostic accuracy [65, 100, 107, 108, 117, 166] (5.50%) were identified as critical steps. Finally, under access to services, expanding AI availability in rural healthcare settings [97, 99, 122, 125, 129, 150, 156] (6.42%) and balancing geographical access and distribution of health technologies [76, 92, 93, 120, 161] (4.59%) were highlighted as essential. (For more details, see Fig. 9).

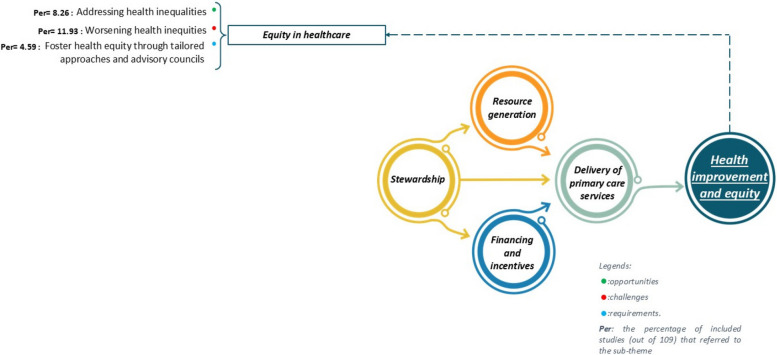

Health improvement and equity

Equity in healthcare is a fundamental principle of the WHO’s Health for All policy, which aims to address unnecessary and unjust health disparities among populations [169]. Although this dimension was not initially included in the PCET model, thematic analysis revealed its critical importance, leading to its incorporation into the framework. While equity is not explicitly defined as a core objective of PHC systems, it aligns closely with their overarching goals of ensuring fair and just access to healthcare services.

A small number of studies (n = 9, 8%) identified opportunities for addressing health inequities through AI [16, 28, 93, 107, 109, 113, 118, 127, 145](8.26%). These studies highlighted AI’s potential to combat global poverty and reduce disparities [93, 109, 113, 118, 145, 170, 171]. Challenges were noted in thirteen studies (12%) including worsening equity in healthcare [15, 66, 68, 69, 81, 98, 109, 119, 121, 132, 135, 146, 164](11.93%). These studies emphasized the risk of exacerbating existing disparities and inequities [69, 98, 109, 119, 121, 135] stemming from algorithmic biases[68, 164]. Requirements for fostering health equity were identified in five studies (5%), which proposed strategies such as developing tailored approaches and establishing advisory councils [15, 109, 117–119] (4.59%). These measures advocate for the integration of equity-focused strategies across healthcare systems and the creation of diverse, interdisciplinary advisory bodies to guide AI policy development [109, 118]. Additionally, promoting inclusive governance frameworks was identified as essential to advancing health equity in AI adoption [15]. For more details, see Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Opportunities, challenges, and requirements of AI implementation within the health improvement and equity

Discussion

Overview of findings

This systematic review synthesized the existing evidence from 109 studies on AI implementation in PHC, analyzing challenges, opportunities, and requirements using the PCET model. While the majority of studies highlighted AI’s potential in comprehensive service delivery, these opportunities can only be fully realized if key challenges are addressed. The most frequently cited barriers were within resource generation, where technical and performance issues, along with data quality and accessibility deficiencies, posed significant limitations. Additionally, in the stewardship, data security, privacy, and consent concerns emerged as critical risks, while the absence of empathy in patient-physician interactions raised concerns about AI’s impact on continuity of care.

Effectively leveraging AI’s potential in PHC requires a robust stewardship function that not only addresses regulatory and ethical barriers but also facilitates the necessary investments in resource generation. Studies strongly emphasized the need for a collaborative approach in co-developing AI solutions. Furthermore, scientific advancements and continuous evaluation were identified as essential for generating reliable evidence and refining AI applications, particularly in addressing performance inconsistencies and data-related limitations. Given that stewardship plays a central role in guiding both policy development and resource allocation, its capacity to drive these improvements will be crucial in translating AI-driven innovations into tangible benefits for PHC delivery.

Overview of findings based on PCET

Stewardship plays a fundamental role in guiding AI integration in PHC, ensuring effective policy development, regulatory oversight, and public trust. AI presents transformative opportunities [28, 70, 78, 105, 112, 145, 146] for innovative healthcare provision [112, 158] and facilitating data-driven decision-making [145]. However, governance-related barriers pose substantial challenges [16, 68, 69, 79, 81, 85, 90, 95, 99, 108, 120, 121, 123, 125, 135, 139, 150, 151, 153, 156, 162, 164], particularly regarding data security, privacy, and consent issues [66, 68, 80, 81, 86, 90, 92, 95, 104–107, 117, 125, 135, 139, 140, 146, 148, 150, 151, 164] — which emerged as the most frequently cited concern in our review. Unlike technical or operational challenges (which fall under Resource Generation), data security and privacy fall under Stewardship because they require regulatory oversight, ethical governance, and public trust. In parallel, deficits in trust and confidence [68, 69, 76, 78, 79, 82, 86, 89–92, 107, 108, 117, 125, 135, 138–140, 143, 146, 149, 151, 164], coupled with low public engagement and acceptance [34, 69, 73, 74, 77, 78, 80–82, 91, 100, 101, 109, 113, 118, 132, 138, 140, 151, 153, 162], further complicate the seamless adoption of AI-driven interventions in PHC. These findings indicate that while AI has the potential to enhance healthcare governance, gaining stakeholder trust and ensuring regulatory clarity remain critical obstacles. In this context, stewardship is responsible for ensuring that trust-building measures—such as ethical guidelines, public awareness, and legal accountability—are in place.

Addressing these issues requires a multi-pronged approach that includes strengthening legal and regulatory frameworks [28, 34, 69, 78, 79, 86, 90, 95, 97, 109, 118, 121, 123, 134, 146, 150, 164], safeguarding data privacy and ethical considerations [16, 28, 33, 66, 68, 69, 73, 78, 86, 90, 92, 95, 117, 118, 142, 143, 146, 148, 151, 164], and implementing rigorous, evidence-based evaluations [28, 72, 74, 83, 86, 89–91, 98, 101, 104, 106, 109, 117, 118, 121, 125, 127, 137, 140, 143, 148, 153] to ensure AI’s reliability, transparency, and accountability [28, 74, 78–80, 86, 92, 95, 101, 103, 107, 108, 116, 117, 143]. Furthermore, our findings underscore the necessity of a co-development approach, actively involving policymakers, healthcare professionals, AI developers, and the public in AI design and governance [15, 16, 33, 34, 62, 69, 71, 78, 80, 92, 93, 95, 97, 101, 105, 109, 110, 115, 117, 120, 121, 124, 125, 132, 133, 139, 140, 143, 146, 150]. Enhancing acceptance and adaptation strategies [74, 82, 85, 90, 91, 95, 97, 100, 104, 108, 112, 121, 128, 133, 139, 157] is equally vital, as AI adoption in PHC depends not only on technological advancements but also on public trust, physician confidence, and ethical oversight.

Compared to previous reviews, our findings align with Ramezani et al. [172], who highlighted AI’s potential to transform healthcare governance through adaptive regulatory frameworks and strategic policymaking. Similarly, recent studies have emphasized AI’s potential to support decision-making and optimize healthcare processes while facing challenges in implementation, governance, and stakeholder trust [27, 35, 173]. However, our study provides a more structured and comprehensive thematic analysis, identifying policy innovation as a key opportunity, regulatory deficits as major barriers, and stakeholder engagement as a crucial requirement for successful AI integration. For sustainable and ethical AI implementation, PHC systems require a governance model that balances innovation with accountability. Regulatory bodies should develop adaptive policies, ensure ethical compliance, and actively engage diverse stakeholders to foster a collaborative, inclusive, and trustworthy AI ecosystem in PHC.

AI has the potential to enhance resource generation in PHC by introducing technical innovations, improving human resource management, and optimizing knowledge utilization. Our findings highlight that leveraging AI-driven advancements in infrastructure and technology can optimize resource allocation [15, 34, 64, 77, 78, 85, 101, 108, 117, 118, 122, 123, 135, 140, 148, 149, 163]. Additionally, enhancing physician job satisfaction and reducing burnout emerged as a significant opportunity[23, 79, 89, 92, 95, 102, 105, 111, 132, 133, 135], as AI can automate routine tasks [15, 23, 34, 62, 77, 79, 85, 94, 101, 110, 111, 113, 118, 132, 135], facilitate decision-making, and provide data-driven support to healthcare providers [15, 28, 66, 70, 79, 81, 90, 99, 108, 116, 118, 126, 132, 135, 140, 148, 149, 153]. If effectively integrated, these benefits can contribute to a more sustainable and efficient PHC system. Despite these advantages, significant barriers hinder AI adoption in resource generation. Among the most cited challenges are technical and performance issues associated with AI systems [15, 16, 28, 73, 76, 77, 80–83, 85, 86, 93, 105, 107, 115, 117, 120, 121, 136, 138–140, 143, 144, 146, 150], raising concerns about reliability, interoperability, and scalability. Additionally, poor data quality, algorithmic bias, and limited accessibility [16, 28, 69, 78–80, 86, 87, 90, 93, 95, 118, 122, 127, 135, 138, 140–144, 151, 153, 156, 163, 164], were identified as key obstacles, as AI applications rely heavily on high-quality datasets for effective decision-making. Unlike regulatory and ethical challenges (discussed in Stewardship), Resource Generation focuses on technical capacity. Furthermore, AI integration poses risks to human expertise and professional skill development [28, 66, 68, 73, 79, 81, 85, 89, 103, 113, 117, 129, 135, 140, 148, 157]. Concerns about provider dissatisfaction and resistance [68, 73, 79, 82, 85, 91, 105, 117, 121, 139, 140, 146, 148, 150, 153, 157] due to fears of job displacement, increased workload [81, 89, 123–125, 127, 148, 153] in adapting to AI and potential disruptions in clinical practice.

Addressing these challenges requires a multi-faceted approach that strengthens technological, knowledge, and workforce foundations of AI in PHC. Studies emphasized the need for continued research and scientific advancement [16, 75, 77, 80, 86, 89, 90, 92, 93, 97–99, 107, 123, 124, 126–132, 134, 135, 144, 153, 161] to improve AI methodologies [28, 75, 86, 90, 91, 102, 112, 122, 125, 141, 143, 146, 163, 164], ensuring they align with the complexities of PHC. Additionally, enhancing AI system reliability by addressing technical defects and performance inconsistencies is critical [16, 62, 73, 77, 86, 90, 92–94, 101, 106, 115, 117, 122, 125, 133, 146, 153, 155, 156]. From a workforce perspective, equipping healthcare professionals with foundational AI knowledge and expertise [33, 34, 68, 78, 82, 93, 95, 100–102, 109, 110, 133, 139, 147, 153, 157, 161] and developing comprehensive educational materials and feedback mechanisms [16, 33, 95, 97, 108, 112, 113, 121, 133, 139, 148–150, 166] are essential steps to facilitate AI integration. By enhancing professional competencies and fostering a culture of continuous learning, AI can serve as a valuable tool rather than a disruptive force in PHC settings.

Findings from previous studies support these insights. Research has linked AI’s effectiveness in resource optimization to data quality, AI performance, and workforce adaptation [174–176]. Likewise, studies underscore the importance of ongoing training programs and robust data governance to ensure that AI-generated insights are accurate, ethical, and actionable [39, 174, 177]. A related study highlighted that successful implementation of AI in healthcare requires organizations to be “AI-capable”, with appropriate infrastructures, resource allocation, and competency-building for health professionals [178]. For successful AI integration in PHC, a strategic and structured approach is necessary. Policymakers and healthcare organizations should prioritize investments in AI infrastructure, establish data governance frameworks, and implement comprehensive capacity-building programs for healthcare professionals. Engaging providers early in AI adoption processes, addressing their concerns through transparent communication, and ensuring interdisciplinary collaboration between AI developers, clinicians, and policymakers can help mitigate resistance and enhance trust in AI applications.

The financial and incentives dimension plays a crucial role in determining the feasibility and sustainability of AI implementation in PHC. Our findings highlight that reducing unnecessary healthcare costs [68, 72, 105, 112, 120, 124, 129, 137, 142, 146, 149, 150, 155, 156, 158, 167] is one of the most frequently cited opportunities. AI-driven automation, predictive analytics, and precision diagnostics can help reduce inefficiencies, prevent redundant procedures, and optimize resource utilization, leading to cost savings [72, 103, 112, 122, 124, 129, 149, 154, 156].

These benefits align with global healthcare trends that emphasize efficiency and value-based care [182]. However, the economic burden of adopting AI [69, 73, 76, 81, 90, 93, 105, 120, 125, 131, 135, 149, 161] poses a significant challenge, as the high costs of infrastructure, data management, regulatory compliance, and workforce training may create financial barriers, particularly in resource-limited settings [183]. Without adequate financial planning, AI adoption risks being restricted to well-funded healthcare institutions, exacerbating existing disparities in access to advanced health technologies. To address these concerns, the need for strategic investment and financial support [15, 34, 73, 90, 91, 95, 98, 103, 112, 120, 121, 128, 131, 140, 148, 150, 164] has been widely emphasized. Targeted funding mechanisms, reimbursement frameworks, and public–private partnerships are essential to facilitate AI integration while ensuring financial sustainability.

Comparisons with previous research further support these findings. Several cost-effectiveness analyses have demonstrated that AI adoption can significantly reduce operational costs in healthcare settings, particularly through decision-support systems in dermatology, dentistry, and ophthalmology [179, 180], as well as screening programs in diabetic retinopathy and retinopathy of prematurity in PHC settings [124, 181]. While these findings suggest AI’s financial benefits in specific healthcare domains, their generalizability to broader PHC services, such as preventive care, chronic disease management, and community-based healthcare, remains uncertain. Furthermore, comprehensive real-world studies evaluating the economic impact of AI in PHC remain limited. Given the unique challenges and financial structures of PHC, future research should specifically assess AI-driven cost savings in primary care settings, ensuring that financial benefits extend beyond specialized medical fields.

Studies in other healthcare contexts have reported that AI has the potential to reduce costs through automation and workflow optimization [184, 185]. However, reviews indicate that while AI adoption can enhance long-term cost efficiency, the initial implementation costs remain prohibitively high, especially in PHC settings [184, 186]. In line with our review, a systematic review of AI in healthcare financing suggested that while AI can streamline administrative processes and optimize spending, without proper investment models, its benefits may remain inaccessible to many health systems [186]. These findings suggest that cost-saving potential alone is not sufficient to drive AI adoption; rather, structured financing strategies must be in place to manage upfront costs and long-term sustainability. To effectively leverage AI’s financial potential while mitigating its cost-related barriers, health systems should prioritize strategic investment mechanisms that support AI development and implementation. Establishing funding pools for AI-driven innovation, integrating AI-friendly reimbursement policies, and aligning financial incentives with AI-enabled services can create a more supportive economic environment. Additionally, policies should focus on ensuring equitable financial access to AI tools, preventing their adoption from being limited to wealthier healthcare institutions.

The integration of AI into primary care service delivery presents substantial opportunities, particularly in enhancing the comprehensiveness, continuity, and accessibility of care. Our findings indicate that improving diagnostic accuracy, optimizing screening programs, and advancing early disease prediction and prevention [15, 23, 28, 34, 64–66, 69, 71–73, 75, 76, 78, 79, 81, 83, 84, 87–89, 91, 92, 96–99, 101, 103, 105, 108, 110, 112–114, 116–118, 120, 122, 124, 126, 129, 131–133, 135, 137, 138, 140–143, 145, 148–156, 158, 159, 161, 163, 166, 168] are among the most significant opportunities in providing comprehensive primary care by AI. These advancements not only enhance patient outcomes but also strengthen preventive care strategies within PHC settings. Additionally, AI contributes to timely access to evidence-based information [15, 28, 62, 69, 73, 79, 81, 89, 92, 93, 98, 100, 101, 108, 110, 111, 115, 118, 123, 138, 140, 162], supporting healthcare providers in making more informed decisions and improving patient adherence in the care process [15, 70, 79, 82, 89, 97, 112, 113, 129, 135, 142, 145, 146, 156, 158]. AI-driven automation can also mitigate workload pressures in healthcare [28, 62, 67, 68, 72, 73, 77, 87, 89, 92, 101, 104, 106, 112, 118–120, 135, 145, 146, 148, 159], addressing one of the long-standing concerns regarding provider burnout and inefficiencies in PHC workflows.

Despite these advantages, several key challenges hinder AI adoption in primary care service delivery. A critical concern in AI-assisted service delivery is the potential disruption of patient-physician interactions, particularly due to the lack of empathy in automated systems [15, 34, 66, 68, 76, 78, 79, 82, 85, 89–91, 93, 95, 100, 113, 121, 125, 130, 140, 148, 150, 151]. While AI enhances efficiency, it cannot replicate the relational aspects of patient care, which remain essential for trust, adherence to treatment, and shared decision-making. The human aspect of care—essential for fostering relationships, shared decision-making, and patient-centered services—cannot be easily replaced by AI, posing a persistent challenge in AI-assisted consultations. Furthermore, the risk of inaccuracies and misdiagnosis [28, 68, 71, 82, 85, 87, 88, 93, 95, 99–101, 107, 115, 118, 132, 148, 149, 157] due to bias, flawed algorithms, or data inconsistencies raises concerns about patient safety and reliability, requiring cautious implementation strategies. Addressing these challenges demands a multi-faceted approach to enhance AI integration into PHC workflows [28, 96, 97, 108, 143, 144, 146, 153]. Strengthening AI-driven clinical practices [28, 85, 91, 95, 98, 99, 115, 120, 148–151, 161] can improve diagnostic support, reduce errors, and optimize care pathways. However, a human-centered approach to AI implementation is essential to ensure that AI tools complement rather than replace physician–patient interactions [80, 86, 87, 95, 107, 113, 125, 140, 143, 147]. Additionally, ongoing evaluations and quality assurance mechanisms should be implemented to monitor AI accuracy, ensure ethical application, and refine AI algorithms to minimize errors.

In line with these findings, prior research has emphasized AI’s capacity to improve efficiency, accessibility, and diagnostic precision while also cautioning against its limitations in replicating human empathy and potential risks in automated decision-making[187–189]. A recent review by Saif-Ur-Rahman et al. underscored AI’s potential to transform primary care service delivery, particularly in resource-limited settings, by optimizing workflow efficiency and expanding access to underserved populations [29]. Given these considerations, future implementation strategies should focus on balancing AI-driven efficiency gains with human-centered care principles. Ensuring that AI complements rather than replaces human expertise by incorporating explainable AI models that provide transparent reasoning behind recommendations and seamlessly integrating AI tools into EHRs and decision-support systems are crucial steps toward maximizing AI’s contributions to PHC service delivery. Continuous monitoring and refinement of AI-driven diagnostic tools will further enhance accuracy and reliability, ensuring their safe and effective application in primary care.

The role of AI in health equity within PHC remains a subject of considerable debate. On one hand, AI presents a promising opportunity to address health inequalities [16, 28, 93, 107, 109, 113, 118, 127, 145], particularly by improving access to healthcare services, enhancing early detection of diseases in underserved populations, and reducing disparities in clinical decision-making. However, concerns persist regarding the risk of worsening health inequities through AI adoption [15, 66, 68, 69, 81, 98, 109, 119, 121, 132, 135, 146, 164]. One of the most pressing concerns is algorithmic bias, where AI systems trained on non-representative datasets may inadvertently perpetuate or exacerbate existing disparities in healthcare delivery. To ensure AI promotes health equity rather than reinforcing disparities, tailored strategies must be implemented. A key requirement is the development of structured advisory councils within health systems and technology companies [15, 109, 117–119], dedicated to identifying and mitigating bias in AI models. These councils can provide oversight on AI-driven decision-making processes, ensuring that algorithmic fairness and inclusivity are prioritized in AI development.

Findings from prior research align with these concerns and recommendations. A scoping review by Sasseville et al. emphasized that the biases affecting diverse groups are more easily mitigated when data are open-sourced, multiple stakeholders are engaged, and ethical principles guide decision-making [190]. Similarly, Obermeyer et al. highlighted how AI algorithms, if not carefully designed, can unintentionally disadvantage racial and socioeconomically marginalized groups [191]. These studies reinforce the notion that AI’s potential to advance health equity depends on proactive strategies to prevent bias and ensure equitable access to AI-driven tools. Beyond technical solutions, adopting a health equity lens in AI policymaking and implementation is essential. This involves incorporating ethical considerations, promoting inclusive governance frameworks, and ensuring regulatory oversight that actively monitors for disparities.

The thematic analysis revealed that certain dimensions, such as service delivery, were more frequently examined, while others, such as financing and equity, had comparatively fewer studies. This imbalance likely reflects the current focus of AI research in PHC, where applications in diagnostics, screening, and patient management are more developed compared to AI’s role in financial management and health equity. However, this may also highlight a research gap, suggesting that AI’s impact on financial sustainability and equitable access to healthcare is underexplored and warrants further investigation. Future studies should aim to bridge this gap by assessing AI-driven financing models and their implications for equitable healthcare delivery.

Potential impact and future directions

We believe the successful integration of AI in PHC depends on a coordinated, structured, and multidimensional approach, recognizing the interconnected nature of stewardship, resource generation, financing, and service delivery. This review highlights that AI’s transformative potential in PHC can only be fully realized when regulatory frameworks, financial mechanisms, technological resources, and clinical workflows are aligned. Stewardship must ensure ethical AI governance, public trust, and policy coherence. Resource generation should focus on workforce adaptation, infrastructure improvements, and data optimization. Financing models need to support AI investment, affordability, and sustainability. Service delivery must enhance accessibility, efficiency, and patient-centered care while mitigating risks such as automation biases and loss of empathy in healthcare interactions.

Given these complex interdependencies, future research should move beyond siloed investigations and adopt systems-thinking approaches to explore how AI-driven changes in one domain influence others. Understanding these interactions will provide valuable insights for developing integrated AI implementation strategies that promote equitable and effective PHC transformation. Moreover, considering the rapid advancements in AI and the evolving healthcare landscape, future research remains continuously updated, ensuring that emerging policy changes, technological developments, and implementation challenges are systematically addressed. Longitudinal studies will be crucial to assess AI’s long-term impact on healthcare efficiency, equity, and quality of care in PHC settings.

Additionally, qualitative and mixed-methods research should capture stakeholder perspectives, including those of patients, healthcare providers, AI developers, and policymakers, to refine AI governance models and ensure that AI solutions align with real-world PHC needs. To navigate emerging ethical dilemmas and regulatory complexities, fostering cross-disciplinary collaborations between healthcare professionals, AI researchers, social scientists, and policymakers will be essential. A proactive, evidence-informed approach is required to ensure that AI not only enhances PHC services but also aligns with fundamental principles of equity, accessibility, and patient-centered care.

Strengths and limitations

This review provides valuable insights into the implementation of AI in PHC. One of the key strengths of this study is the use of the PCET model, which offers a structured framework to analyze AI-related opportunities, challenges, and requirements across multiple dimensions. Additionally, the inclusion of diverse studies from multiple databases strengthens the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, the methodological quality assessment indicated that most of the included studies were of high or moderate quality, with rigorous methodologies and clear reporting. However, 19% were classified as low quality due to methodological limitations, particularly in areas such as sample representativeness, transparency in data collection, and risk of bias. A key concern was whether lower-quality studies influenced any major findings. While these studies contributed to some identified themes, our analysis showed that the most frequently cited and emphasized themes were primarily derived from high-quality sources. Additionally, no formal sensitivity analysis was conducted in the traditional statistical sense. Instead, we assessed the robustness of our findings through the frequency distribution of studies across themes and sub-themes. This alternative approach provided a structured way to assess consistency in the literature, reinforcing the reliability of the thematic synthesis. To further ensure methodological rigor, each study’s contribution was critically assessed within the thematic framework, prioritizing findings supported by robust methodologies to minimize potential biases.

Despite these strengths, this review has limitations. The exclusion of non-English publications may have restricted the scope of the findings, potentially leading to a Western-centric perspective on AI integration in PHC. Future research should consider multilingual approaches to capture a more comprehensive global perspective. Additionally, the broad inclusion criteria, while beneficial for capturing a wide range of AI applications, introduced heterogeneity across studies, making direct comparisons more challenging. Moreover, the geographic distribution of the included studies suggests that AI adoption in PHC may be underrepresented in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in Africa and South America. This could reflect either a publication bias favoring high-income countries or a genuine gap in AI implementation and research in these regions. Future studies should focus on expanding AI research in underserved areas to ensure a more globally representative understanding of AI’s role in PHC. Furthermore, the predominance of qualitative studies, although valuable for understanding contextual factors and implementation challenges, limits the ability to draw quantitative conclusions regarding AI’s effectiveness in PHC settings.

Finally, given the rapid advancement of AI technologies and the continuous publication of new studies, this review only includes studies up to January 2024. AI applications in PHC evolve rapidly, necessitating frequent updates to ensure that emerging evidence is captured and that policy recommendations remain relevant and aligned with the latest technological and regulatory developments.

Given these limitations, future research should focus on addressing gaps in methodological rigor and standardization, ensuring more consistent and comparable evidence across AI applications in PHC. Additionally, there is a pressing need to explore AI implementation in underrepresented and resource-limited settings, where digital health innovations may have the greatest impact. In addition, future systematic reviews should reassess newly published evidence to refine guidance on AI adoption in PHC. Strengthening research efforts in these areas will be essential for guiding equitable and effective AI integration into PHC systems worldwide.

Conclusion

This systematic review provides a comprehensive synthesis of the opportunities, challenges, and requirements associated with AI implementation in PHC. The findings highlight both the potential and complexities of AI across various functional dimensions, emphasizing the need for a coordinated, multidimensional approach to ensure its effective integration. Additionally, the review underscores the critical role of health system functions—particularly stewardship, resource generation, and financing—in supporting service delivery and maximizing AI’s impact within PHC. To translate these findings into practical advancements, future research should focus on addressing existing knowledge gaps, examining the interactions among different dimensions, and developing strategies that optimize AI’s benefits for all PHC stakeholders. Strengthening collaborative efforts between policymakers, healthcare providers, and AI developers will be essential in shaping an equitable, efficient, and patient-centered AI-driven PHC system.

Supplementary Information

Supplementay Material 1: S1 and S3: Search Strategy and Quality Assessment

Supplementay Material 2: S2: Characteristics of studies

Supplementay Material 3: S4, S5, S6: Opportunities, challenges, and requirements

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Elham Sharifpoor, an information specialist at the Kerman University of Medical Sciences, for her support in developing and validating the search strategy across seven databases.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in this study.

Abbreviations

- PHC

Primary Health Care

- WHO

World Health Organization

- AI

Artificial Intelligence

- ML

Machine Learning

- DL

Deep Learning

- NLP

Natural Language Processing

- EHR

Electronic Health Records

- PCET

Primary Care Evaluation Tool

- SPIDER framework

Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, and Research type, Frameworks

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- OSF

Open Science Framework

- Mesh

Medical Subject Headings

- JBI

Johanna Briggs Institute

Authors’ contributions

FY, MN, and NA contributed to the study selection, data extraction, and data synthesis under the supervision of RD. FY wrote the first version of the manuscript. RD, ML, and MPG critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. MMG contributed significantly during the revision phase of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This paper synthesizes evidence from other published studies; thus, ethics approval was not required.

Consent for publication

No datasets were generated or analyzed for this study, so consent for publication does not apply.

Competing of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gillam S. Is the declaration of Alma Ata still relevant to primary health care? BMJ. 2008;336(7643):536–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehrolhassani MH, Dehnavieh R, Haghdoost AA, Khosravi S. Evaluation of the primary healthcare program in Iran: a systematic review. Aust J Prim Health. 2018;24(5):359–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathur MR. Revitalizing Alma-Ata: Strengthening primary oral health care for achieving universal health coverage. Indian J Dent Res. 2019;30:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Health–Europe TL. Strengthening primary health care to achieve universal health coverage. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2024;39:100897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Primary Health Care: Transforming Vision into Action: Operational Framework: Geneva: World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017832.

- 6.Morley DC, Rohde JE, Williams G. Practising health for all. J Policy Anal Manage. 1985;4:612. [Google Scholar]