Abstract

Background

Juvenile hormone (JH) is synthesized by the corpora allata (CA) and controls development and reproduction in insects. We recently used CRISPR/Cas9 to establish a line lacking the enzyme that catalyzes the final step of JH biosynthesis in mosquitoes, a P450 epoxidase. The CA of the epox−/− mutants do not synthesize epoxidized JH III but methyl farneosate (MF), a weak agonist of the JH receptor. Female epox−/− mosquitoes have reduced JH signaling and show a substantial loss of reproductive fitness. To understand the molecular basis of this loss of fitness, we constructed ovarian mRNA libraries of Ae. aegypti of the Orlando strain wild-type (WT) and epoxidase null mutants (epox−/−) and investigated differential expression of reproductive genes.

Results

We performed triplicate RNA-seq analyses of female WT and epox−/− ovaries dissected at four critical stages of oogenesis: Ovaries from newly eclosed females (0h), sugar-fed females at 4 days post-eclosion (4d SF), females 16h (16h BF), and 48 h after a blood meal (48h BF). Silencing of epoxidase resulted in a drastic change in the expression of thousands of genes.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that epoxidase deficiency leads to a reduction in JH signaling that has significant effects on Ae. aegypti ovarian transcriptome profiles. Ecdysteroid titers are dysregulated in the mutants, leading to a significant delay in the expression of vitelline membrane genes and other transcripts. We discovered changes in the expression of 230 long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) that may play an important role in the regulation of ovarian genes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12915-025-02266-z.

Keywords: Aedes aegypti, Ovaries, Juvenile hormone, Transcriptome, Ecdysteroids, lncRNA

Highlights

Identifying expression patterns in the ovaries of wild-type females during previtellogenesis (PVG) and vitellogenesis (VG) maturation.

Reporting genes affected by the knock-down of the epoxidase gene in the ovarian transcriptomes at four critical stages of oogenesis.

Describing misregulated DNA binding proteins and long non-coding RNAs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12915-025-02266-z.

Background

Mosquitoes are vectors of diseases such as dengue, Zika, chikungunya and malaria, which pose a critical threat to public health in many parts of the world [1]. Ovarian development is a crucial factor in the fitness of female mosquitoes and thus their ability to transmit diseases. Understanding mosquito biology [2], and in particular the mechanisms that control mosquito reproductive physiology [3], is fundamental to the development of novel control methods to eliminate mosquito-borne diseases. The meroistic ovary of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes contains about 120 ovarioles. Each ovariole consists of two parts, a distal germarium and a vitellarium proximal to a common oviduct through which the eggs migrate during oviposition [4]. Three main periods can be distinguished in the development of the ovaries during a gonotrophic cycle in adult Ae. aegypti mosquitoes: Previtellogenesis (PVG), ovarian resting stage (ORS) and vitellogenesis (VG) [5]. In the first 3 days after emerging of the adults, the primary follicles reach the mature size of PVG of about 100 µm; thereafter, the oocytes remain in a dynamic “state of arrest” and only enter VG after a blood meal [5, 6].

Juvenile hormone (JH) is a key regulator of many aspects of reproductive biology in mosquitoes [3]. In the corpora allata (CA) of mosquitoes, JH is synthesized from the inactive precursor farnesoic acid (FA) by methylation to methyl farneosate and subsequent epoxidation to epoxidized JH III [7]. To investigate the evolutionary significance of MF epoxidation, we generated Ae. aegypti mosquitoes that completely lack the enzyme that catalyzes the epoxidation of MF, the MF epoxidase [8]. The CA of our epoxidase mutants synthesize MF instead of JH III [8]. MF is a “weak” agonist of the JH receptor [9, 10]. This weak JH signaling leads to delay in normal development, completion of oogenesis, and thus a drastic reduction in reproductive output, with females laying only half as many eggs as wild-type females [8]. To understand the molecular basis of this reproductive fitness cost of epox−/− females, we generated ovarian mRNA libraries and analyzed differential gene expression between mutants and wild types. The results of these studies indicate that epoxidase knockdown causes a drastic change in the expression of thousands of genes, including long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), a class of functional ncRNA transcripts that are expressed in a species- and tissue-specific manner [11]. The study also shows a delay in the ecdysteroid titer in the mutant, which leads to a significant delay in the expression of critical ovarian genes after a blood meal. In the future, these genes could be functionally evaluated to confirm their role in mediating reproductive performance. Overall, the results reported here contribute to a better understanding of the role of JH in controlling the reproductive biology of mosquitoes.

Results

Epox−/− adult females show major defective ovarian phenotypes

A cohort of about 100 follicles per mosquito ovary begins to develop synchronously after adult eclosion. However, in our epox−/− mutants, weak JH signaling causes half of these follicles to undergo apoptosis and oosorption, so that females lay only half as many eggs after a blood meal [8]. To better understand this deficiency, we examined the phenotypic changes of female WT and epox−/− ovaries dissected at four critical stages of oogenesis: (A) Ovaries from newly eclosed females (0 h); (B) ovaries from sugar-fed females 4 days post-eclosion (4d SF) that have completed PVG maturation; (C) ovaries with early VG follicles from females at 16h after a blood meal (16h BF); and (D) ovaries with advanced vitellogenic follicles from females at 48h after a blood meal (48h BF). These are four stages where severe ovarian phenotypic differences between WT and epox−/−females can be observed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Ovarian development in WT and epox−/− females. Examples of follicles and ovaries dissected at four critical stages of oogenesis: 0h: newly eclosed females; 4d SF: sugar fed females 4 days after adult eclosion; 16h BF: females 16h after a blood meal; 48h BF: females 48h after a blood meal. Upper panel: close view of follicles. Lower panel: view of whole ovaries. (Scale bars in μm)

The ovaries of the newly eclosed females of both genotypes were phenotypically similar, but at the end of PVG development, the number of follicles of the 4d SF epox−/− females was reduced by half, and the follicles were significantly smaller and less mature than the primary PVG follicles of the WT females [8]. We have previously reported that PVG oocyte lipids play an important function in the reproductive physiology of Ae. aegypti and that JH plays a key role in the control of lipid incorporation in PVG oocytes [8, 12].

Sixteen hours after a blood meal, the most obvious phenotypic difference in the early VG follicles was a delay in follicle development in the mutants. Additional file 1 shows the size of primary follicles during the first 24h after a blood meal. A significant number of primary follicles of epox−/− females did not reach the size of mature PVG of WT females (≈100 µm) until approximately 12–16h after blood feeding. Finally, the VG follicles of WT females assumed their characteristic ovoid shape 48h after blood feeding, whereas the VG follicles of epox−/−females remained round (Fig. 1).

Weak JH signaling results in drastic gene expression changes of ovarian mRNA repertoires in epoxidase mutant females

To explore the molecular basis of oogenesis deficiencies caused by weak juvenile hormone signaling, we performed triplicate RNA-seq analyses of female WT and epox−/− ovaries dissected at the four critical stages of oogenesis described above: 0h, 4d SF, 16h BF and 48h BF. The total number of reads from the WT and epox−/− samples at all four time points ranged from 16.2 to 28 million, with an average of 82% of the reads clearly belonging to the reference genome of Ae. aegypti (see Additional files 2 and 3). In the 24 samples we identified 19,804 genes, 13,014 of each passed a filtration step using counts per million (CPM) ˃ 0.5 in at least one library.

The exploratory data analysis (EDA) indicated that epoxidase knockdown induced a drastic change in the expression of thousands of genes (Additional file 4). Hierarchical clustering showed good separation between biological replicates of the same genotype and between the time points analyzed, indicating that no significant differences were introduced during library construction and that variation between technical replicates was minimal (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Exploratory data analysis. A Heatmap showing hierarchical clustering of the top 1,000 differentially expressed genes. B PCA plot of the RNAseq datasets using the first two components. C An UpSet plot of the DEGs identified at each time point in the WT and epox−/− comparison shows the degree of overlap of the DEGs between the time points. The number of DEGs (79) present in all comparisons is indicated by arrows and pink color. The number of unique DEGs for each timepoint is denoted by blue color

Principal component analysis (PCA) using the first two components (PC1 and PC2) explained 56 and 19% of the variance, respectively (Fig. 2B). The number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with a false discovery rate (FDR) of < 0.01 and a fold-change (FC) of > 2 as cutoffs for the triplicate RNA-seq analyses of WT versus epox−/− for each of the time points can be found in Additional file 4. Volcano plots showed differences between the expression levels of the genes when comparing WT and epox−/− and WT across timepoints (see Additional file 5). An UpSet plot shows the number of overlapped differentially expressed genes between WT and epox−/− for all the timepoints, 79 of which were differentially expressed in all timepoints (Fig. 2C). We used qPCR to validate the expression of selected DEGs (Additional file 6).

Ovarian gene expression significantly changes in WT during the PVG and VG stages

To better understand the effects of weak JH signaling in oogenesis, we first analyzed the changes in gene expression in the ovaries of wild-type females during PVG and VG maturation. The highest changes in gene expression were detected when comparing the transcriptomes of 0h and 4d SF, a period when the previtellogenic maturation is completed. A total of 3,616 genes were differentially expressed, with 2,335 genes upregulated and 1,281 downregulated (Additional file 4). Changes in gene expression decreased when transcriptomes of 4d SF and 16h BF were compared. This period corresponds to the “initiation phase”, a stage after a blood meal when follicle growth recommences and incorporation of vitellogenin begins. A total of 810 genes were differentially expressed, with 552 genes upregulated and 258 downregulated (Additional file 4); finally, changes in gene expression increased again when comparing the transcriptomes of 16h BF and 48h BF. This period corresponds to the “trophic phase”, the main phase of incorporation of vitellogenin into growing oocytes. One thousand two hundred two genes were differentially expressed, with 643 genes upregulated and 559 downregulated (Additional file 4). One hundred seventy three differentially expressed genes were present in all samples (Additional file7).

We used k-means clustering to identify groups of genes with similar expression patterns; the four clusters identified by k-means clustering using the top 2,000 genes showed the largest changes when comparing the 0h and 4d SFs (Fig. 3A). Enrichment analysis using gene ontology (GO) terms revealed that several biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions are important for each of the time points (Fig. 3B). Clusters A and B contain genes with higher expression at 0h and 4d SF and no or lower expression at 16h BF and 48h BF. The largest cluster A comprised 1,070 genes and revealed an enrichment of genes involved in adhesion, oxidoreductase and hydrolase activities, heme binding, and membrane proteins. Cluster B contains 425 genes enriched in genes encoding troponin complex, myofilament, proteolysis, and peptidase activity. The genes with higher expression at 16h BF and 48h BF were included in cluster C, and their functions were related to reproductive processes, oogenesis, epithelial cell development, and integral components of the membrane. The smallest cluster D with only 86 genes represented genes with higher expression at 48h BF. In this cluster, we found genes involved in fatty acid metabolism, oxidative stress response and detoxification, Co-A transferase, peroxidase, and antioxidant activities, as well as genes targeting the oocyte chorion. The full list of the genes enriched in each cluster can be found in the Figshare repository [13].

Fig. 3.

Gene clusters and expression patterns in the WT transcriptome ovaries. A Heatmap depicting 4 clusters recovered from k-means clustering of the top 2,000 differentially expressed genes and B GO terms enrichment with the expression patterns of each cluster for the dataset presenting changes in the WT

The knockdown of the epoxidase gene has a pervasive effect on multiple gene pathways

After completing the analysis of changes in gene expression during ovarian development in WT females, we examined the effects of the epoxidase mutation on gene expression at the same time points. After applying the threshold of FDR < 0.01 and FC > 2, 3,275 DEGs were identified in all four-time points; with 48h blood fed samples having the maximum number of DEGs (1,239), and 0 h the smallest quantity (290) (Additional file 4). We performed Parametric Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (PGSEA) using GO Biological Processes to identify classes of genes that are over-represented among DEGs and may have an association with the observed ovarian phenotypes. These analyses highlighted gene pathways that were affected by the knockdown of the epoxidase gene. In the pathway enrichment, heatmaps red and blue indicate activated and suppressed pathways, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Differential gene expression of the ovarian transcriptomes of WT vs. epox−/−. Pre-ranked gene set enrichment analysis (PGSEA) using GO terms for the four timepoints. The heatmaps depict the levels of activation (red) and suppression (blue). The higher the level of activation the darker the red and the higher level of suppression is shown in dark blue in the gradient scale

When the transcriptomes of newly emerged ovaries (0h) were compared, several pathways were suppressed in mutants. Among them are endosomal transport and Acetyl-CoA, carbohydrate, nucleoside, and glycosyl metabolism. On the contrary, multicellular organism development, and detection of chemical stimulus were activated in mutants. Comparison of the ovarian transcriptomes of 4d SF WT and epox−/− females revealed several suppressed pathways in mutants; DNA-dependent DNA replication, processing of RNA, metabolism of phospholipids, protein catabolism, and processes involved in mitosis. Conversely, genes involved in proteolysis were activated in mutants.

Sixteen hours after a blood meal, several pathways were downregulated in mutant ovaries, including multiple processes involved in reproduction, metabolic processes, embryo and tissue development, and transcription. Finally, at 48h after a blood meal, mutant ovaries showed activation of biological processes connected to endopeptidase activity, reproduction, germ cell development, and phenol-containing compound metabolic process.

Epoxidase mutants show a significant delay in the expression of many ovarian genes

Our phenotypic studies revealed a significant delay in ovarian development in the mutants at both the PVG and VG stages (Fig. 1). A delay was also observed in the expression of several highly expressed genes when the transcriptomes of ovaries from WT and epox−/− females 16h BF and 48h BF were compared. Examples of genes that exhibited this delay in expression include those encoding vitelline membrane proteins (VMP), odorant binding proteins (OBP), major royal jelly proteins (MRJP), and chitin binding domain proteins (CBDP) (Fig. 5; Additional file 8).

Fig. 5.

Delay in the expression of ecdysteroid-regulated genes in epox−/− mutants. Developmental expression of three vitelline membrane proteins (VMP): 15a1: AAEL013027. 15a2: AAEL017403. 15a3: AAEL014561. Panels A and B show the time changes in the expression of transcripts in the transcriptomes of WT and epox−/− from 0 to 48h after blood meal. Females at 0h after blood meal were 4-day-old sugar fed. Each point represents means ± SEM of three transcriptome replicates. Panel C shows the developmental changes of the transcripts of the same three VMPs measured by qPCR. Each value represents means ± SEM of 3 independent samples of ovaries from 5 female mosquitoes mRNA: number of mRNA transcripts per 10,000 copies of rpL32. All individual data values are available in the Figshare repository (excel spreadsheet “VMPs_data_used_for_Fig. 5_and_Additional_file6.xlsx”inside VMPs_Fig. 5_Additional_file_6 directory) [13]

Several VMPs are highly expressed in our transcriptomes. Using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), we compared the expression of three vitelline membrane proteins at six different time points during ovarian development. In WT, high expression was detected at 24h BF and 36h BF, with reduced levels at 48h BF. In contrast, epox−/− ovaries showed comparatively lower expression at 24h BF and 36h BF and a very significant increase in the 48h BF transcriptome compared to WT (Fig. 5). At the same time, expression of OBP, MRJP, and CBDP was peaking in the WT ovaries at 48h after a blood meal; while in the mutant ovaries expression at 48h remained low when compared to WT (Additional file 8).

To better understand the dynamic between ecdysteroid titers and the expression of VMPs in the epox−/−, we used LC–MS/MS to assess the titers of three ecdysteroids at different times after a blood meal in whole body of WT and epox−/− females. These ecdysteroids are the precursor 2-deoxyecdysone (2DOE), the most important synthetic hormone ecdysone (E) and the most active metabolite 20-OH-ecdysone (20E). In the epox−/− mutants, we observed a significant delay in the peak levels of 2DOE, E, and 20E (Fig. 6). Considering the key role that ecdysteroids play in oogenesis, we examined the expression of genes involved in ecdysteroid biosynthesis and signaling in our transcriptomes (Additional file 9). Among the dysregulated genes, we can mention the biosynthetic enzyme Neverland and the nuclear hormone receptor FTZ-F1, both genes showing a significantly higher expression at 48h BF in the mutant ovaries.

Fig. 6.

Delay in the increase in ecdysteroids titers in epox−/− mutants. Ecdysteroid titers in whole body of WT and epox−/− females during the first 54h after a blood meal: A 2-deoxyecdysone (2DOE), B Ecdysone, and C 20-OH-ecdysone (20E). Each point represents means ± SEM of three independent replicates of 3 mosquitoes. Asterisks denote the time points where the levels of ecdysteroids were significantly different. In all panels asterisks denote significant differences (unpaired t-test; *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; and ns: not significantly different). All individual data values are available in the Figshare repository (excel spreadsheet “Ecdysteroids_titers_sum.xlsx” inside HPLC_MS_MS_Figure6 directory) [13]

The epoxidase mutation modifies the expression of long non-coding RNAs and DNA binding proteins

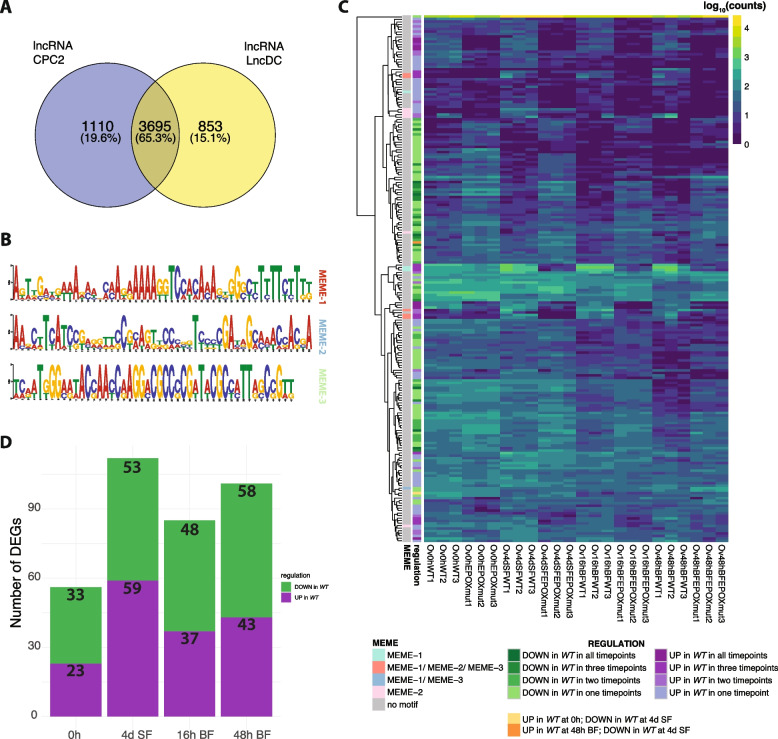

We searched our transcriptomes for long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) [9]. Of the 34,477 predicted transcripts in Ae. aegypti, 5,068 were annotated as ncRNAs (corresponding to 4,704 genes). Most of the ncRNA transcripts (4,503) had hits against Ae. aegypti (taxid 7159), only 36 transcripts had no hit. The CPC2 algorithm identified 4,805 transcripts (corresponding to 4,476 genes) as lncRNAs with no coding potential. Similarly, the LncDC algorithm predicted 4,548 (corresponding to 4085 genes) as lncRNAs. By combining both methods, 3,695 ncRNAs (65.3%) were consistently classified as lncRNAs and used for further motif analysis (Fig. 7A). A total of 234 transcripts representing 211 genes were differentially expressed at least at one time point (Fig. 7C). The highest number of differentially expressed lncRNAs was observed at 4d SF and 48h BF, with 53 and 58 upregulated genes and 59 and 43 downregulated genes, respectively (Fig. 7D). We identified three novel, ungapped motifs within differentially expressed lncRNAs that may function as recruitment sites for fixed-length DNA motifs, such as triplex target sites (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Analysis of the non-coding RNAs. A Overlap of the long non-coding RNAs predicted using CPC2 and lncRNA tools. B Motifs predicted in the differentially expressed lncRNAs using MEME-suite and their placement on the transcripts. C Heatmap with expression patterns (log10(Converted Counts)) of the DE lncRNAs. Panels on the left correspond to the type of regulation (up/ down regulated in WT in specific timepoint) in our transcriptomic datasets and the presence or absence of the specific motifs predicted by the MEME suite. D Bar-plot presenting numbers of the down- and upregulated lncRNAs in each of the time points

Additionally, we explored whether candidate lncRNAs are capable of forming RNA:DNA triplex structures, which would support their potential role as regulatory elements, particularly in relation to genes influenced by juvenile hormones, such as Kr-h1 (Additional file10). Using the Fasim-LongTarget algorithm [14], which predicts triplex formation based on Hoogsteen and reverse Hoogsteen base pairing, we identified genomic regions with potential lncRNA binding sites. Our findings suggest that certain lncRNAs may indeed act as regulators of key genes like Kr-h1. The complete output of this analysis is available in the Figshare repository [13].

We also searched for DNA-binding proteins (DBPs), transcription factors (TFs), and proteins with zinc finger domain (Fig. 8A). Of the 28,391 proteins in the proteome of Ae. aegypti, 13,069 were identified as DBPs with CLAPE [15] and 2,243 and 6,561 were classified as TFs using DeepTFactor [16] and TransFacPred [17] respectively (Fig. 8B). One thousand nine hundred eighty two proteins were classified as TFs by both methods. Two thousand nine hundred sixty two sequences were identified to have Zinc-finger motifs. The most abundant group, with 1,378 proteins corresponding to 776 genes, was classified as C2H2; the second largest group included Treble-clef with 975 proteins, followed by the third most abundant group classified as Zinc-ribbon (271 proteins) (Fig. 8B). Seven hundred sixty four proteins were classified as DBPs and TFs (by both methods) and had zinc finger domain (Fig. 8B). The largest number of zinc finger domain DEGs was at 48h BF for the FC 2 and 4d SF for the FC 1.5 cutoffs (Fig. 8C). We identified 54 DEGs with C2H2 domains for the FC 2 and 142 for the FC 1.5. In addition, we identified the Kr-h1 gene (AAEL002390) with a C2H2 domain (indicated by arrow in Fig. 8A). All the outputs from the analysis can be found in the Figshare repository [13].

Fig. 8.

DNA-binding proteins, transcription factors, and Zinc-finger domain analysis in Ae. aegypti. A Heatmap of the log10 (converted counts) of the genes identified as DBPs denoted by dark red color; TFs recovered by the two methods (DeepTFactor and TransFacPred) denoted by different shades of orange; Zinc-finger domains (C2H2, Treble-clef, and Zinc-ribbon) denoted by different shades of blue. Genes important for mosquito development are denoted by the arrows below the heatmap. B An UpSet plot of the analysis of the DBPs, TFs, and Zinc-finger domains representing the degree of overlap between different analyses and methods. All the sets with sizes smaller than 40 were excluded. C Number of the differentially expressed genes with Zinc-finger domains using fold-change 1.5 and 2 cutoffs for each time point

Discussion

Hormonal regulation of oogenesis in mosquitoes

Oscillating pulses of JH and 20E control the timing of reproduction in mosquitoes [3]. In the ovaries of Ae. aegypti, periods of growth and development alternate with periods of arrest, with the developing follicles passing through four main periods of arrest, which define four “developmental gates” [4]. There is a “germarial gate” (GG) at which the ovarian follicles are differentiated but closely associated with the germarium, with 20E at adult eclosion providing the stimulus to develop beyond the GG to a size of 40 µm and reach the “stage I gate” (SIG). After adult eclosion, JH provides the signal to develop beyond the SIG, whereby the primary follicles grow to a size of 100 µm, reach the “previtellogenic gate” (PVG) and remain “in arrest” in this gate until a blood meal. Follicles begin to exit pre-vitellogenic arrest within 2h after blood feeding, in direct response to insulin like peptide 3 (ILP3), ovary ecdysteroidogenic hormone (OEH), and increased nutrient supply [18]. Finally, the primary follicles develop beyond the “stage III gate” (SIIIG), begin to deposit the yolk and grow to the final egg size of about 600 µm. This development beyond SIIIG is regulated by 20E.

Our epoxidase mutants exhibit “weak JH signaling” [10], resulting in striking changes in ovarian phenotype during both the previtellogenic and vitellogenic ovarian stages, including a delay in the progression of the PVG stage and a decrease in the number and size of PVG follicles, as well as a delay in the progression of the VG stage and a reduction in the number of eggs laid by about 50% [8]. These phenotypes indicate that the mutants PVG follicles cannot reach the SIG (the 100 µm full PVG size; see Fig. 1) [8] and developing beyond this gate only occurs after a blood meal. As a result, development is delayed beyond the SIG, as is the increase in 20E titers, which brings about the end of “previtellogenic” arrest. Topical application of a JH analog to epox−/− females immediately after adult eclosion dramatically increases both the number and size of mature previtellogenic follicles to WT levels, confirming that weak MF/JH signaling alone is responsible for the deficient phenotypes of mutant ovaries [8].

Complexity of ovarian transcriptomes

In the female mosquito, two ovarian gonotrophic cycles take place simultaneously during a reproductive cycle [3]. While the original primary follicles fully mature and are laid, the secondary follicles develop to the previtellogenic resting stage and new secondary follicles separate from the germarium. The non-blood-fed ovary contains quiescent stem cell-like populations for both germline and somatic cells of the developing egg follicles, which are activated in response to a blood meal and begin proliferation and differentiation [4]. Primary oocytes complete oogenesis by packaging the yolk from the fat body and RNA and proteins from nurse cells, which later degenerate [19]. The follicle cells then secrete an egg membrane (chorion) before they also degenerate, leading to the formation of a mature egg [19]. This cellular diversity challenges the analyses of gene expression in ovaries as it creates a background noise of mixture of genes expressed in different cells that play different roles during oogenesis, as well as maternal transcripts that are loaded into the developing eggs. In addition, when ovaries are dissected for library preparation, hemocytes and fat body cells may contaminate the samples. Despite these problems, however, we found several important differences in gene expression caused by weak JH signaling.

Characteristics of ovarian transcriptomes

A major goal of this work was to identify gene expression changes in the epoxidase mutants to gain insight into possible molecular mechanisms by which “weak” JH signaling generates the observed ovarian deficient phenotypes. Our four different time points cover several of the critical stages and transitions of ovarian tissue during the gonotrophic cycle. The 0h shows gene expression in the ovaries of newly eclosed females (at the GG). The 4d SF shows the expression of genes in fully matured PVG ovaries (at the SIG). The 16h BF and 48h BF ovarian transcriptomes show mRNAs expressed in early and late stages of the vitellogenic phase (beyond the SIIIG). The ovary during PVG is highly enriched in genes involved in translation, including rRNA and tRNA, mitochondrial biogenesis, RNA polymerase function, mRNA splicing, and maturation. The high expression of all these genes indicates that the sugar-fed ovary is preparing for the rapid transcriptional response and growth that will occur after a blood meal. During PVG development, mutants showed downregulations of pathways involved in ribosome biogenesis, spliceosome, and ubiquitin mediated proteolysis.

Epoxidase mutants show a significant delay in the expression of many ovarian genes

Before and after a blood meal, a striking phenotype observed in the mutants was the delay in ovarian development. The delay was particularly noted when analyzing the expression of critical genes involved in the vitellogenic phase, including those encoding components of the vitelline membrane, the innermost layer of the eggshell. It has been previously reported that vitelline membrane protein mRNAs are very low 12h after blood meal, with a rapid increase in expression that peaks at 36h and declines 48h after blood meal [20]. We observed a corresponding expression pattern in the WT group with an increase in VMP expression by 16h after the blood meal, a maximum at 36h and reduced expression at 48h. In epox−/− females, we observed a delayed expression of VMPs, along with a higher expression of VMPs at 48h after the blood meal compared to 36h after blood ingestion. It has been previously described that the expression of genes for OBP, MRJP, and CBDP peaks at 48h after blood feeding [20]. Similar to VMPs, we also observed a pattern of delay for these genes in the mutant, while in WT the expression was high at 48h BF, in the mutant their expression was low across all time points analyzed (Additional file8). In Ae. aegypti, the expression of VMPs is regulated by ecdysteroids secreted by the follicular epithelium cells after a blood meal [21]. Indeed, we observed a significant delay in the peak of ecdysteroids in epox−/− mutants, suggesting that this hormonal dysregulation is one of the main causes of the observed delay in VG development in the mutants. Moreover, there is evidence for direct modulation of ecdysone biosynthesis and signaling by JH [22, 23] in Drosophila. Therefore, we hypothesized that the observed delay in ecdysteroid titer in the mutant after blood feeding is directly related to the weak JH signaling and is the driving force for the developmental delay of the mutant ovaries.

Weak JH signaling modifies the expression of lncRNAs and DNA-binding proteins

The knockdown of epoxidase led to a drastic change in the expression of thousands of genes, including those encoding long non-coding RNAs, which are important regulators of gene expression at the epigenetic, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional levels [24]. The activity of lncRNAs results from their secondary structures which involves complex interactions with DNA sequences, RNAs, or proteins [11]. A recent study investigated the role of ovary-specific lncRNAs in the reproductive capacity of Aedes albopictus [25] and showed that gene silencing led to a significant reduction in egg laying and hatching. Here we have observed up- and downregulations of several lncRNAs that appear to be involved in regulation of expression of many genes involved in ovarian development, including Krüppel homolog 1. Overall, this suggests that lncRNAs play important roles during mosquito reproduction.

DNA-binding proteins include transcription factors, polymerases, nucleases, and histones, all of them playing key roles in the regulation of gene expression. The activated JH receptor complex interacts with JH response elements in regulatory regions of target genes, some targets of the JH are transcription factors that in turn can regulate the expression of downstream genes [26]. Our results revealed that weak JH signaling resulted in dysregulation of hundreds of DNA-binding proteins, among them transcription factors such as Krüppel homolog 1; one of the crucial effectors which mediates the action of JH [27].

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that the effects of the epoxidase mutation on gene expression are broad; it provides a valuable dataset that offers a comprehensive overview of comparative gene expression in WT and epox−/− ovaries and will be essential for planning future studies to further understand the molecular genetic basis of the phenotypic effects of the epoxidase mutation in the ovaries of this important disease vector.

Methods

Insects, tissue dissection and RNA extraction

Ae. aegypti of the Orlando strain (WT) and epoxidase null mutants (epox−/−) were reared at 28 °C and 80% humidity as previously described [8]. Adult mosquitoes were offered a cotton pad soaked in a 10% sucrose solution. Four-day-old female mosquitoes were artificially fed pig blood equilibrated to 37 °C, and ATP was added to the blood meal to a final concentration of 1 mM immediately before use, as previously described [12]. Ovaries were dissected from four different adult female developmental stages: newly eclosed (0h), adults 4 days after eclosion fed 10% sugar (4d SF), and adults 16h (16h BF) and 48h (48h BF) after blood feeding. Total RNA was extracted from 5 to 10 pairs of ovaries from each developmental stage in triplicate using Norgen Biotek’s total RNA purification kit. Total RNA was treated with DNase I according to Norgen Biotek’s instructions.

Libraries preparation and sequencing

RNA library preparation and sequencing were conducted at GENEWIZ, LLC (South Plainfield, NJ, USA). RNA sample integrity and quantification was assessed using TapeStation (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA).

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated and treated with rDNAse I using the Machere-Nagel total RNA purification kit (Düren, Germany) and reverse transcribed using the Verso cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). The mRNA copy number, normalized to ribosomal protein L32 (rpL32) mRNA, was quantified in triplicate reactions in a QuantStudio™ 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) using the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The gene accession numbers as well as primer and probe sequences are listed in Additional file 11.

Data analysis

The quality of the reads was checked manually using FastQC v0.11.9 [28]. Low-quality regions and adapter sequences were removed using Trimmomatic v0.39 [29] in paired-end mode with the following parameters LEADING:30, TRAILING:30, MINLEN:100, HEADCROP:14, CROP:10, and standard Illumina adapter sequences. The high-quality RNA-seq reads were mapped to the Ae. aegypti reference genome (Ae. aegypti LVP_AGWG genome from VectorBase Release 57) using STAR v2.7.3a [30], with the sjdbOverhang set to 99. Next, read coverage across the Ae. aegypti reference genome was determined for each RNA-seq library using the feature Counts v2.0.1 tool of the Subread R package [31]. The resulting expression matrix was used in IDEP v0.96 [32], filtered with a cutoff set to 0.5 (counts per million, CPM) and transformed with rlog (regularized log) [33]. All data that passed the filtering step were then annotated with eggNOG-mapper v2.1.9 [34] and used for exploratory data analysis (EDA) with hierarchical clustering, k-means clustering and principal component analysis (PCA). In addition, we performed an enrichment analysis for k-means clustering of the data for the WT using Biological Process, Cellular Component and Molecular Function using the build-in tool in IDEP v96. Differentially expressed genes between the different conditions and time points were identified using the R package DESeq2 v1.38.3 [33]. All genes with FDR of < 0.01 and a fold-change FC of > 2 as cutoffs were considered significant DEGs. To better understand the biological role of the resulting DEGs, we performed an enrichment analysis using terms from the Gene Ontology and the PGSEA v1.60.0 R package [35] implemented in IDEP pipeline.

Identification of long non-coding RNAs and proteins with Zinc-finger domains/DNA binding proteins

To detect the long non-coding RNAs, we used a combination of CPC2 v3 [36] and LncDC v1.3.5 [37] analysis. First, all predicted transcripts were extracted from the Ae. aegypti VectorBase v57 dataset, which were annotated as non-coding RNAs. They were searched with the CPC2 algorithm and used to train a model with secondary structure features and predictions with the LncDC tool. Transcripts supported by both methods were considered “confident” lncRNAs and were used as BLASTn queries to search the NCBI nucleotide database to investigate the taxonomic assignment of the lncRNAs. In addition, all lncRNAs that were also differentially expressed (DE) were used as queries for motif searches with the MEME tool within the MEME suite [38] and examined for the possibility of binding to DNA sequences of the genes of interest by forming RNA:DNA triplexes with Fasim-LongTarget v3 [14]. To identify DNA-binding proteins as well as potential transcription factors we used CLAPE, a novel tool for predicting DBPs [15] and combination of DeepTFactor, a deep learning tool for predicting TFs [16] and TransFacPred [17], a hybrid approach for predicting TFs to search the entire proteome of Ae. aegypti from VectorBase v57. Additionally, we searched the proteome for the presence of proteins using web server ZnF-Prot (https://project.iith.ac.in/znprot/).

Measurement of ecdysteroid titers

Ecdysteroids were measured by HPLC MS/MS analysis as previously described [39]. In brief, after methanolic extraction, detectability of the ecdysteroids is increased 16- to 20-fold by conversion to their 14,15-anhydrooximes. These are further purified by pipette tip solid-phase extraction on a three-layer sorbent and subjected to HPLC–MS/MS analysis [39]. All the results are available at the Figshare repository [13].

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Length of primary follicles during the first 24 hours after a blood meal. Each point represents the mean ± SEM of 60 follicles from 6 different females.

Additional file 2: Supplemental Table S1. Total numbers of reads and unique mapped reads for ovarian transcriptomes.

Additional file 3: Fig. S2. Exploratory data analysis of ovarian transcriptomes of WT and epox−/− mutants. A) The total read counts in millions that uniquely mapped to the reference genome. B) Density plot showing the expression values of the transformed data. C) Distribution of transformed expression values for each replicate. D) Scatter plot of transformed expression values of the first two WT replicates for 0h.

Additional file 4: Supplemental Table S2. Differential gene expression analysis for comparisons of WT across time points and WT versus epox−/− transcriptomes. The table shows the number of differentially expressed genes that were upregulated and downregulated in both contrasts for all time points compared.

Additional file 5: Fig. S3. Exploratory data analysis, volcano plots. 1) For the WT and epox−/− mutant comparisons: A) 0h B) 4d SF C) 16h BF, and D) 48h BF; 2) For the WT across timepoints comparisons: A) 0h vs. 4d SF B) 4d SF vs. 16h BF, and C) 16h BF vs. 48h BF.

Additional file 6: Fig. S4. Validation of selected DGEs by Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR). The expression of three vitelline membrane genes (15a1, 15a2 and 15a3) at three different time points in the ovarian transcriptome were compared with qPCR analysis of the same genes in ovaries dissected at similar time points. All values are means ± standard error of triplicate analysis. A) WT transcriptome. Expressed as a counts. B) WT qPCR. C) epox−/− transcriptome. D) epox−/−epox-/- qPCR. The number of transcripts are expressed as number of mRNA copies/10000 copies of ribosomal protein L32 (rpL32), the gene used for normalization. All individual data values are available in the Figshare repository (excel spreadsheet “VMPs_data_used_for_Figure5_and_Additional_file6.xlsx” inside VMPs_Figure5_Additional_file_6 directory) [13].

Additional file 7: Fig. S5. Differentially gene expression during ovarian development in WT. An UpSet plot showing common DEGs between the three comparisons 0h vs. 4d SF, 4dSF vs. 16h BF and 16h BF vs. 48h BF. The number of DEGs (173) present in all comparisons is indicated by arrows and pink color. The number of unique DEGs for each comparison is denoted by blue color.

Additional file 8: Fig. S6. Developmental expression of genes with a delay at 48h after blood meal. The bars show the developmental expression of odorant binding proteins (OBP); Mayor royal jelly proteins (MRJP) and chitin binding protein domain 2 (CBPD). Asterisks denote that the expression of genes were significantly different. Values are means ± standard error of counts from the three library replicates. In all panels asterisks denote significant differences (unpaired t-test; *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001). All individual data values are available in the Figshare repository (excel spreadsheet “delay_genes_data_used_for_Additional_figure_8.xlsx” inside delay_genes_Additional_file_8 directory) [13].

Additional file 9: Supplemental Table S3. Expression of genes involved in ecdysteroid biosynthesis and signaling. The table shows the average number of reads for the triplicates RNA-seq analyses of WT and epox−/− for each of the time point. Ecdysteroid biosynthesis genes names and accession numbers. Ecdysteroid signaling genes names and accession numbers. Values are means ± standard error of counts from the three library replicates.

Additional file 10: Fig. S7. Putative regulation of Kr-h1 by lncRNAs. The expression of Kr-h1 and two lncRNAs at different time points in the ovarian transcriptome was compared. The lncRNA AAEL025087 shows similar expression changes as Kr-h1 in epox−/− mutants, it is downregulated in epox−/− mutants. In contrast, the lncRNA AAEL028011 shows opposite expression changes and is upregulated in epox−/− mutants. Values are means ± standard error of counts from the three library replicates. In all panels asterisks denote significant differences (unpaired t-test; *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001, and ns: not significantly different).

Additional file 11: Supplemental Table S4.Sequences of primers and probes used for RT-qPCR transcript quantification.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- JH

Juvenile hormone

- CA

Corpora allata

- MF

Methyl farneosate

- lncRNAs

Long non-coding RNAs

- WT

wild-type Ae. aegypti of the Orlando strain

- epox−/−

Epoxidase null mutants

- PVG

Previtellogenesis

- ORS

Ovarian resting stage

- VG

Vitellogenesis

- CPM

Count per million

- rlog

Regularized log

- EDA

Exploratory data analysis

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- FDR

False discovery rate

- FC

Fold-change

- GO

Gene Ontology

- PGSEA

Parametric Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

- VMP

Vitelline membrane proteins

- OBP

Odorant binding proteins

- MRJP

Major royal jelly proteins

- CBDP

Chitin binding domain proteins

- 2DOE

2-deoxyecdysone

- E

ecdysone

- 20E

20-OH-ecdysone

- Kr-h1

Krüppel homolog 1

- DBPs

DNA-binding proteins

- TFs

Transcription factors

- GG

Germarial gate

- SIG

Stage I gate

- ILP3

Insulin-like peptide 3

- OEH

Ovary ecdysteroidogenic hormone

- SIIIG

Stage III gate

Authors’ contributions

M.N., M.M.W., M.K. and F.G.N. designed research; M.N., M.M.W., M.K., F.G.N., M.M., P.B., and H.O.M. performed research; M.N., M.M.W, M.K and F.G.N. analyzed data; and M.N., M.M.W, M.K. and F.G.N. wrote the paper. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Funding

This research was funded by project 22-21244S from the Czech Science Foundation, Czech Republic to MN, and grant R21AI167849 from the National Institutes of Health-NIAID, USA to FGN. This research was also supported by the ERD fund “Centre for Research of Pathogenicity and Virulence of Parasites” number CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000759.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article, its supplementary information files and publicly available repositories. Datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the Figshare repository under 10.6084/m9.figshare.26780326 [13]. Sequence data generated for this study are deposited in the NCBI SRA archive under accession PRJNA1128542 [40]. All individual data values are available in the Figshare repository [13].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Martin Kolísko, Email: kolisko@paru.cas.cz.

Marcela Nouzova, Email: marcela.nouzova@paru.cas.cz.

References

- 1.Chala B, Hamde F. Emerging and re-emerging vector-borne infectious diseases and the challenges for control: a review. Front Public Health. 2021;9:715759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barillas-Mury C, Ribeiro JMC, Valenzuela JG. Understanding pathogen survival and transmission by arthropod vectors to prevent human disease. Science. 2022;377:eabc2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu J, Noriega FG. Chapter four - the role of juvenile hormone in mosquito development and reproduction. In: Raikhel AS, editor. Advances in insect physiology. Academic Press; 2016. p. 93–113.

- 4.Clements AN. The biology of mosquitoes. Volume 1. Development, nutrition and reproduction. London: Chapman & Hall, 1992. viii + 509 pp. Hard cover £50. ISBN 0–412–40180–0. Bull Entomol Res. 1993;83:307–8.

- 5.Klowden MJ. Endocrine aspects of mosquito reproduction. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 1997;35:491–512. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagedorn HH, Turner S, Hagedorn EA, Pontecorvo D, Greenbaum P, Pfeiffer D, et al. Postemergence growth of the ovarian follicles of Aedes aegypti. J Insect Physiol. 1977;23:203–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rivera-Pérez C, Clifton ME, Noriega FG, Jindra M. Juvenile hormone regulation and action. In: Advances in invertebrate (neuro)endocrinology. Apple Academic Press; 2020.

- 8.Nouzova M, Edwards MJ, Michalkova V, Ramirez CE, Ruiz M, Areiza M, et al. Epoxidation of juvenile hormone was a key innovation improving insect reproductive fitness. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2021;118:e2109381118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jindra M, Uhlirova M, Charles J-P, Smykal V, Hill RJ. Genetic evidence for function of the bHLH-PAS protein gce/met as a juvenile hormone receptor. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bittova L, Jedlicka P, Dracinsky M, Kirubakaran P, Vondrasek J, Hanus R, et al. Exquisite ligand stereoselectivity of a Drosophila juvenile hormone receptor contrasts with its broad agonist repertoire. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:410–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pang KC, Frith MC, Mattick JS. Rapid evolution of noncoding RNAs: lack of conservation does not mean lack of function. Trends Genet. 2006;22:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clifton ME, Noriega FG. The fate of follicles after a blood meal is dependent on previtellogenic nutrition and juvenile hormone in Aedes aegypti. J Insect Physiol. 2012;58:1007–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiśniewska MM, Kolísko M, Berková P, Moss M, Maaroufi HO, Noriega FG, Nouzova M. Ovarian transcriptomes analysis examines the molecular bases of oogenesis deficiencies caused by weak juvenile hormone signaling. Figshare. 2024. 10.6084/m9.figshare.26780326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Wen Y, Wu Y, Xu B, Lin J, Zhu H. Fasim-longtarget enables fast and accurate genome-wide lncRNA/DNA binding prediction. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022;20:3347–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Tian B. Protein–DNA binding sites prediction based on pre-trained protein language model and contrastive learning. Brief Bioinformatics. 2024;25:bbad488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim GB, Gao Y, Palsson BO, Lee SY. DeepTFactor: a deep learning-based tool for the prediction of transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2021;118:e2021171118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patiyal S, Tiwari P, Ghai M, Dhapola A, Dhall A, Raghava GPS. A hybrid approach for predicting transcription factors. Frontiers in Bioinformatics. 2024;4:1425419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valzania L, Mattee MT, Strand MR, Brown MR. Blood feeding activates the vitellogenic stage of oogenesis in the mosquito Aedes aegypti through inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 by the insulin and TOR pathways. Dev Biol. 2019;454:85–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isoe J, Riehle MA, Miesfeld RL. Mosquito egg development and eggshell formation. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2023. 10.1101/pdb.top107669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akbari OS, Antoshechkin I, Amrhein H, Williams B, Diloreto R, Sandler J, et al. The developmental transcriptome of the mosquito Aedes aegypti, an invasive species and major arbovirus vector. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics. 2013;3:1493–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin Y, Hamblin MT, Edwards MJ, Barillas-Mury C, Kanost MR, Knipple DC, et al. Structure, expression, and hormonal control of genes from the mosquito, Aedes aegypti, which encode proteins similar to the vitelline membrane proteins of Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1993;155:558–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu S, Li K, Gao Y, Liu X, Chen W, Ge W, et al. Antagonistic actions of juvenile hormone and 20-hydroxyecdysone within the ring gland determine developmental transitions in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115:139–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang T, Song W, Li Z, Qian W, Wei L, Yang Y, et al. Krüppel homolog 1 represses insect ecdysone biosynthesis by directly inhibiting the transcription of steroidogenic enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115:3960–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li K, Tian Y, Yuan Y, Fan X, Yang M, He Z, et al. Insights into the functions of lncRNAs in Drosophila. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belavilas-Trovas A, Gregoriou M-E, Tastsoglou S, Soukia O, Giakountis A, Mathiopoulos K. A species-specific lncRNA modulates the reproductive ability of the Asian tiger mosquito. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 2022;10:885767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jindra M, Tumova S, Milacek M, Bittova L. Chapter two - a decade with the juvenile hormone receptor. In: Adams ME, editor. Advances in insect physiology. Academic Press; 2021. p. 37–85.

- 27.He Q, Zhang Y. Kr-h1, a cornerstone gene in insect life history. Front Physiol. 2022;13:905441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andrews S. FASTQC. A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. 2010.

- 29.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:923–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ge SX, Son EW, Yao RN. iDEP: an integrated web application for differential expression and pathway analysis of RNA-Seq data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2018;19:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cantalapiedra CP, Hernández-Plaza A, Letunic I, Bork P, Huerta-Cepas J. eggNOG-mapper v2: functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38:5825–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Furge K, Dykema K. PGSEA: parametric gene set enrichment analysis. R package version 1.60.0. 2019.

- 36.Kang Y-J, Yang D-C, Kong L, Hou M, Meng Y-Q, Wei L, Gao G. CPC2: a fast and accurate coding potential calculator based on sequence intrinsic features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W12–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li M, Liang C. LncDC: a machine learning-based tool for long non-coding RNA detection from RNA-Seq data. Scientific Repports. 2022;12:19083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bailey TL, Johnson J, Grant CE, Noble WS. The MEME suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W39-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marešová L, Moos M, Opekar S, Kazek M, Eichler C, Šimek P. A validated HPLC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous determination of ecdysteroid hormones in subminimal amounts of biological material. J Lipid Res. 2024;65(10):100640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiśniewska MM, Kolisko M, Berková P, Moss M, Maaroufi HO, Noriega FG, Nouzova M. Ovarian transcriptomes analysis examines the molecular bases of oogenesis deficiencies caused by weak juvenile hormone signaling. GenBank. 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1128542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Length of primary follicles during the first 24 hours after a blood meal. Each point represents the mean ± SEM of 60 follicles from 6 different females.

Additional file 2: Supplemental Table S1. Total numbers of reads and unique mapped reads for ovarian transcriptomes.

Additional file 3: Fig. S2. Exploratory data analysis of ovarian transcriptomes of WT and epox−/− mutants. A) The total read counts in millions that uniquely mapped to the reference genome. B) Density plot showing the expression values of the transformed data. C) Distribution of transformed expression values for each replicate. D) Scatter plot of transformed expression values of the first two WT replicates for 0h.

Additional file 4: Supplemental Table S2. Differential gene expression analysis for comparisons of WT across time points and WT versus epox−/− transcriptomes. The table shows the number of differentially expressed genes that were upregulated and downregulated in both contrasts for all time points compared.

Additional file 5: Fig. S3. Exploratory data analysis, volcano plots. 1) For the WT and epox−/− mutant comparisons: A) 0h B) 4d SF C) 16h BF, and D) 48h BF; 2) For the WT across timepoints comparisons: A) 0h vs. 4d SF B) 4d SF vs. 16h BF, and C) 16h BF vs. 48h BF.

Additional file 6: Fig. S4. Validation of selected DGEs by Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR). The expression of three vitelline membrane genes (15a1, 15a2 and 15a3) at three different time points in the ovarian transcriptome were compared with qPCR analysis of the same genes in ovaries dissected at similar time points. All values are means ± standard error of triplicate analysis. A) WT transcriptome. Expressed as a counts. B) WT qPCR. C) epox−/− transcriptome. D) epox−/−epox-/- qPCR. The number of transcripts are expressed as number of mRNA copies/10000 copies of ribosomal protein L32 (rpL32), the gene used for normalization. All individual data values are available in the Figshare repository (excel spreadsheet “VMPs_data_used_for_Figure5_and_Additional_file6.xlsx” inside VMPs_Figure5_Additional_file_6 directory) [13].

Additional file 7: Fig. S5. Differentially gene expression during ovarian development in WT. An UpSet plot showing common DEGs between the three comparisons 0h vs. 4d SF, 4dSF vs. 16h BF and 16h BF vs. 48h BF. The number of DEGs (173) present in all comparisons is indicated by arrows and pink color. The number of unique DEGs for each comparison is denoted by blue color.

Additional file 8: Fig. S6. Developmental expression of genes with a delay at 48h after blood meal. The bars show the developmental expression of odorant binding proteins (OBP); Mayor royal jelly proteins (MRJP) and chitin binding protein domain 2 (CBPD). Asterisks denote that the expression of genes were significantly different. Values are means ± standard error of counts from the three library replicates. In all panels asterisks denote significant differences (unpaired t-test; *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001). All individual data values are available in the Figshare repository (excel spreadsheet “delay_genes_data_used_for_Additional_figure_8.xlsx” inside delay_genes_Additional_file_8 directory) [13].

Additional file 9: Supplemental Table S3. Expression of genes involved in ecdysteroid biosynthesis and signaling. The table shows the average number of reads for the triplicates RNA-seq analyses of WT and epox−/− for each of the time point. Ecdysteroid biosynthesis genes names and accession numbers. Ecdysteroid signaling genes names and accession numbers. Values are means ± standard error of counts from the three library replicates.

Additional file 10: Fig. S7. Putative regulation of Kr-h1 by lncRNAs. The expression of Kr-h1 and two lncRNAs at different time points in the ovarian transcriptome was compared. The lncRNA AAEL025087 shows similar expression changes as Kr-h1 in epox−/− mutants, it is downregulated in epox−/− mutants. In contrast, the lncRNA AAEL028011 shows opposite expression changes and is upregulated in epox−/− mutants. Values are means ± standard error of counts from the three library replicates. In all panels asterisks denote significant differences (unpaired t-test; *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001, and ns: not significantly different).

Additional file 11: Supplemental Table S4.Sequences of primers and probes used for RT-qPCR transcript quantification.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article, its supplementary information files and publicly available repositories. Datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the Figshare repository under 10.6084/m9.figshare.26780326 [13]. Sequence data generated for this study are deposited in the NCBI SRA archive under accession PRJNA1128542 [40]. All individual data values are available in the Figshare repository [13].