Abstract

Background

Adenomyosis is associated with lower implantation and higher miscarriage rates. Studies on recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) and recurrent implantation failure (RIF) have shown that endometrial immune cell populations play a crucial role during implantation and early pregnancy. In women with adenomyosis, improved pregnancy outcomes following assisted reproductive technologies (ART) and pre-treatment with GnRH-agonists (GnRH-a) prior to frozen embryo transfer (FET) have been reported. We aimed to compare the endometrial immune cell populations of women with adenomyosis to those of women with RPL and RIF, and to characterise endometrial leucocyte subpopulations within the adenomyosis group before and after GnRH-a.

Methods

We conducted a prospective study between 2021 and 2024. Women with infertility and adenomyosis undergoing ART underwent one endometrial biopsy 6–9 days after oocyte retrieval and a second biopsy after 3 months of GnRH-a prior to FET. Women in the RPL and RIF groups underwent one endometrial biopsy in the midluteal phase. We performed flow cytometry (FC) to characterise immune cell populations and immunohistochemistry (IHC) to analyse uterine natural killer cells (uNKs) and plasma cells (PC). The Kruskal–Wallis test was used for comparisons between the study groups, and the Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used for paired samples before and after GnRH-a.

Results

Endometrial leucocyte subpopulations at baseline showed no significant differences between the adenomyosis (n = 20), the RPL (n = 40) and RIF (n = 15) group. In the adenomyosis group, following GnRH-a, we observed a significant decrease in the percentage of monocytes, from 77% (IQR 71, 82) to 71% (IQR 65, 75) (adj. p = 0.030). Baseline IHC showed elevated plasma cell concentrations (≥ 5/mm2) in 1/20 adenomyosis patients (5%), 4/40 RPL patients (10%) and 1/15 RIF patients (6.7%) while uNK cells were elevated (≥ 300/mm2) in 8/20 adenomyosis patients (40%), 11/40 RPL patients (27.5%) and 1/15 RIF patients (6.7%).

Conclusions

Women with infertility and adenomyosis showed a similar endometrial immune profile as women with RPL and RIF. The beneficial effect of GnRH-a prior to FET in women with adenomyosis may be mediated through effects on monocyte subpopulations. Based on the high prevalence of elevated uNK cells in patients with adenomyosis, we suggest testing women with adenomyosis undergoing ART before FET.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12916-025-04162-3.

Keywords: Adenomyosis, Infertility, Endometrial immune cells, Uterine natural killer cells, GnRH-agonists, Recurrent implantation failure, Recurrent pregnancy loss

Background

Adenomyosis has historically been considered a pathological condition of peri- and post-menopausal women, associated with heavy and prolonged bleeding and diagnosed histologically upon hysterectomy. With advancements in transvaginal sonography and increased availability of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [1, 2], adenomyosis is now commonly diagnosed in women of reproductive age [3–5], and has been linked to infertility. In fact, lower pregnancy and live birth rates, higher miscarriage rates, and an increased risk of pregnancy complications have all been reported in women with adenomyosis [6–8]. Despite the high prevalence of 20–34% in reproductive-aged women [9], the pathogenesis of adenomyosis in this population has not yet been fully understood. Endocrine and immunological alterations seem to play an important role and exert a synergistic effect [10–18].

At the same time, studies evaluating the pathophysiology of recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) and recurrent implantation failure (RIF) have shown that specific immune cell populations are fundamental for the establishment and maintenance of normal implantation and (early) pregnancy, and aberrations are associated with RPL and RIF [19]. It is therefore plausible that the systemic and endometrial immunological alterations described in adenomyosis are—at least in part—responsible for the subfertility and adverse pregnancy outcomes [20].

Various immune cell populations participate in the establishment of immune tolerance at the feto-maternal interface, especially uterine natural killer (uNK) cells, T-lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages, and dendritic cells. uNK cells constitute the predominant leucocyte population in healthy endometrium and account for 30–40% of all endometrial leucocytes during the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle [21, 22]. Based on the expression of surface markers CD16 and CD56, they can be divided into different subsets, mainly CD56brightCD16dim and CD56dimCD16bright, the first being primarily responsible for cytokine production and the latter being highly cytotoxic. In the endometrium, mainly CD56brightCD16dim NK cells are present, regulating vascular remodelling, promoting tissue repair, modulating the immune response, and interacting with trophoblast cells [23–25]. Thanks to their regulatory function, they play an important role in early pregnancy.

T cells are lymphocytes involved in the adaptive immunity. Different subsets perform different functions. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) help maintain immune balance and are crucial to the immune tolerance of the foetus. T helper 17 cells (Th17), on the other hand, play a significant role in the defence against extracellular pathogens. Producing pro-inflammatory cytokines, they prevent not only pregnancy infections, but also trophoblast invasion, and have been associated with preeclampsia and RPL [26, 27]. NKT cells are another subset of T cells which, in the endometrium, help to regulate local immune responses and tissue homeostasis [28]. Monocytes circulate in the bloodstream and, migrating into tissues, can differentiate into macrophages or, if the need arises, into dendritic cells. In the endometrium, they are involved in trophoblast invasion, tissue and vascular remodelling, and immune surveillance [29, 30].

Previous studies have observed a pro-inflammatory milieu with an increase of Th17 and decrease of Treg cells both in peripheral blood and in the endometrium in women with adenomyosis [31]. Similar alterations have been described in RPL patients, making it plausible that this shift in T cell populations might be involved in adverse pregnancy outcomes [32, 33]. Overall, T lymphocytes as well as macrophages seem to be increased in the endometrium of women with adenomyosis [20, 34, 35]. Moreover, increased concentrations of peripheral NK cells (pNK) and uNK cells have been associated with early pregnancy loss [36, 37]. So far, only a few studies have analysed pNK and uNK cell concentrations in women with adenomyosis, reporting conflicting results [20, 38, 39]. Thus, it remains unclear whether these cells play a role in infertility and miscarriages in women with adenomyosis.

The immune system is known to be influenced by sex steroids. Accordingly, variations in leucocyte populations throughout the menstrual cycle have been observed in both peripheral blood and the endometrium [40]. In adenomyosis, the relative progesterone resistance and local hyperoestrogenism appear to have a pro-inflammatory effect on the immune system [16, 41, 42], which seems to be modifiable via administration of exogenous hormones and hormone blockers [43]. In women with adenomyosis undergoing assisted reproductive technologies (ART), observational studies have reported improved pregnancy outcomes following pre-treatment with GnRH-agonists (GnRH-a) prior to frozen embryo transfer (FET) [6, 44–46]. Although the specific mechanisms of GnRH-a beyond central hormonal suppression remain unclear, they may be mediated through local and/or systemic immunomodulation.

Based on these previous studies, we hypothesised that the endometrial immune cell populations in women with adenomyosis might show alterations similar to those seen in RPL and RIF. Thus, we aimed to phenotypically characterise immune cell populations in the endometrium of women with adenomyosis before and after GnRH-a treatment prior to FET. Furthermore, we compared the results with endometrial immune cell populations in patients with RPL and RIF to investigate both differences as well as possible correlations with ART outcome.

Methods

Study population

This prospective study was performed at the Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria, between 2021 and 2024 after approval of the study protocol by the local Ethics Committee. The study group consisted of women with infertility and adenomyosis who presented to the Department of Gynecological Endocrinology and Reproductive Medicine, underwent ART, and agreed to participate. Adenomyosis was diagnosed with transvaginal ultrasound if ≥ 2 criteria published by the MUSA group were met [1, 47]. The second study population consisted of women with RPL (defined as ≥ 2 consecutive miscarriages) without adenomyosis and the third of women who underwent ART and experienced RIF (defined as ≥ 3 embryo transfers without pregnancy [48, 49, 50, 51]. No sample size calculation was performed. Exclusion criteria for all study groups included autoimmune diseases (e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease) and infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis B and C. Women with adenomyosis were excluded if they had experienced RPL or RIF in the past. Women with RPL and RIF were excluded from the comparison group if diagnosed with adenomyosis, known genetic or anatomical uterine abnormalities, or haematologic disorders (e.g. antiphospholipid syndrome). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Procedures

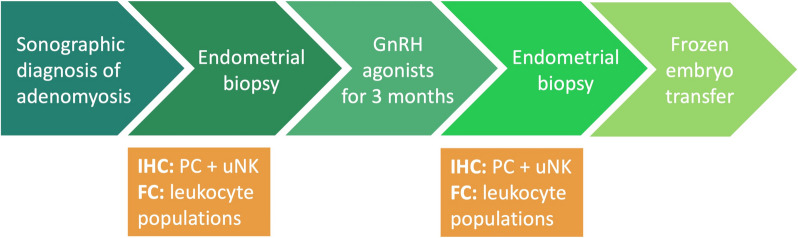

A flow chart summarising the study procedure for the adenomyosis group can be found in Fig. 1. Women with adenomyosis underwent ovarian hyperstimulation with gonadotropins using an antagonist protocol and oocyte retrieval according to standard institutional procedure. After oocyte retrieval, they began micronised progesterone 200 mg vaginally once daily. After 6–9 days, corresponding to the mid-luteal phase, an endometrial biopsy was performed. The vagina and cervix were swabbed with saline, taking care to avoid contamination, and the biopsy was performed via Pipelle de Cornier (CCD Laboratoire de la Femme®) to obtain an endometrial tissue sample. Treatment with GnRH-a (Leuprorelin 3.57 mg subcutaneously once a month) was started on the same day. After the third injection, all participants were given a standardised add-back therapy (estradiol 2 mg orally twice a day, micronised progesterone 200 mg vaginally once a day) for 3 weeks to induce comparable endocrine conditions to those at first sampling. Thereafter, endometrial tissue was obtained again for post-treatment analysis. A FET was performed in a subsequent programmed cycle according to our institutional protocol. Women in the RPL and RIF groups underwent an endometrial biopsy only once between cycle day 19 and 24 (mid-luteal phase) of their natural cycle.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart showing the study procedures in the adenomyosis group

Laboratory procedures

The endometrial tissue samples were analysed using flow cytometry (FC) and immunohistochemistry (IHC), as we have previously published [30]. Briefly, endometrial single cell suspension was prepared using the gentleMACS™ Octo Dissociator (Miltenyibiotec) without enzymatic digestion. For the staining, cells were incubated with fluorophore-labelled antibodies (see Additional file 1: Table S1). FC analysis was performed on DxFLEX (Beckman Coulter, USA). FC data were analysed using FlowJo (version 10.8.0 for Windows FlowJo Software, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

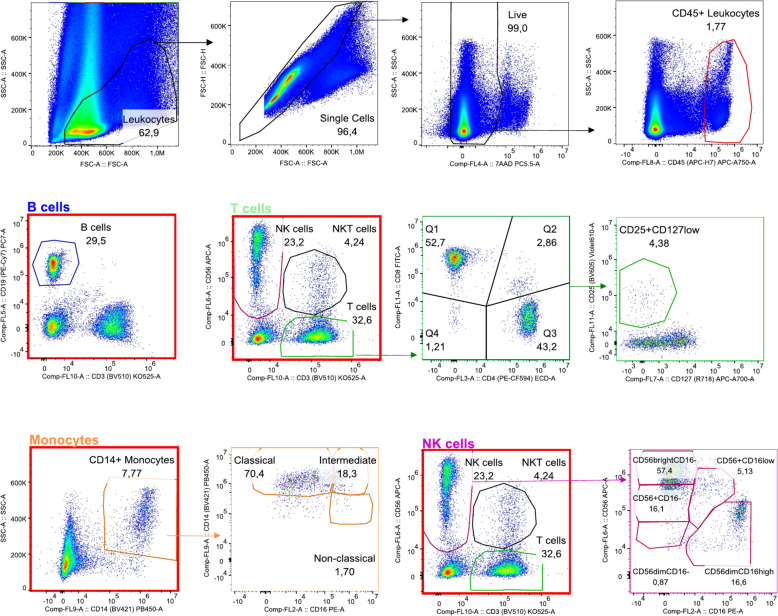

Gating strategy for viable CD45 + cells after exclusion of cellular debris, doublets, and dead cells was as follows: B cells were characterised as CD19 +, monocytes as CD14 +, NK cells as CD56 + CD3 −, NKT cells as CD56 + CD3 +, and T cells as CD56 − CD3 +. Monocytes were further separated into classical, intermediate, and non-classical subsets based on CD14/CD16 expression levels. T cells were characterised as CD8 + or CD4 +, from the latter, the CD25 + CD127 low were identified as T regulatory cells. NK cells were identified with further separation into five subsets in the endometrium and into two subsets in the peripheral blood based on their CD56/CD16 expression. The gating strategy is depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Gating strategy for viable CD45 + cells in endometrial biopsies

Part of the endometrial biopsy was fixed in 5% buffered formalin and sent to Reprognostics GbR in Mannheim, Germany, where the samples were immunohistochemically stained for CD138-positive plasma cells and CD56-positive uNK cells. All samples were analysed independently by two experts using a Zeiss AxioPlan Microscope and the AxioVison 4.8 program. A concentration of at least 5 plasma cells or 300 uNK cells per mm2 was regarded as elevated, as defined by previous studies [52, 53].

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics, leukocyte populations, and pregnancy outcomes were summarised using counts (%) for categorical variables and median (interquartile range (IQR)) for numeric variables. The leukocyte populations in the adenomyosis group before GnRH-a treatment were compared to those of the RPL and RIF groups using Kruskal–Wallis tests. Within the adenomyosis group, leukocyte populations before and after GnRH-a treatment were compared using Wilcoxon signed rank tests for paired samples. Women with adenomyosis who did not contribute samples both prior to and following GnRH-a treatment were excluded. For each set of comparisons of leukocyte populations, a correction for multiple testing was performed using the Benjamini–Hochberg method [54]. Due to small sample size, no subgroup analyses were performed.

Results

A total of 33 women with adenomyosis were included in the study. Of these, 20 women contributed samples both prior to and following GnRH-a treatment and were therefore considered in the full analysis. The remaining 13 were excluded after recruitment and/or the collection of samples due to various reasons, including failed sample collection or failure to complete the GnRH-a therapy due to side effects. 40 patients with RPL and 15 patients with RIF were included in the comparison groups. Their baseline characteristics can be found in Table 1. While adenomyosis and RIF patients were mostly nulligravid and nulliparous, 24/40 RPL patients (60%) reported a history of 2 or 3 pregnancies and 16/40 (40%) of 4 or more pregnancies. The median number of miscarriages in the RPL group was 3 (ICR 2.00, 5.00). Twenty out of 40 (50%) were cases of primary RPL, while the remaining 20/40 (50%) suffered from secondary RPL. In the RIF group, the median number of embryo transfers was 3 [ICR 3.00, 8.00]. Of the 20 women with adenomyosis, at transvaginal sonography, 9 (45%) fulfilled 2 of the diagnostic criteria as published by the MUSA group [1], 8 (40%) fulfilled 3 criteria, and 1 (5%) 4 criteria, while for one patient detailed ultrasound information was missing. In further detail, 15/20 (75%) women showed both direct and indirect signs as described in the MUSA consensus paper from 2022 [47], 3/20 (15%) only direct signs, and for 2/20 (10%) patients, no detailed information was available. In the adenomyosis group, 1/20 (5%) had concomitant thyroid autoimmunity (TAI), presenting thyroperoxidase antibodies and/or thyroglobulin antibodies. In the RPL and RIF groups, 4/40 (10%) and 1/15 (6.67%) showed TAI.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the adenomyosis, RPL and RIF group

| Adenomyosis | RIF | RPL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (N) | 20 | 15 | 40 |

| Age in years (median, IQR) | 34 (32, 36) | 34 (32, 37) | 33 (31, 38) |

| Gravida (N, %) | |||

| 0 | 12 (60.0%) | 9 (60.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 1 | 6 (30.0%) | 4 (26.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| 2–3 | 2 (10.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | 24 (60.0%) |

| ≥ 4 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 16 (40.0%) |

| Nr. previous miscarriages | 0 (0, 0.25] | 0 (0, 0.50) | 3.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| Nr. previous embryo transfers | 0 (0, 1.0) | 3.0 (3.0, 4.0) | 0 (0, 0) |

| Missing (N, %) | 1 (5.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Endometriosis laparoscopically confirmed | 9 (45.0%) | - | - |

| Sonography—Nr. of diagnostic criteria fulfilled | |||

| 2 | 9 (45.0%) | - | - |

| 3 | 8 (40.0%) | - | - |

| 4 | 1 (5.0%) | - | - |

| Missing | 2 (10.0%) | - | - |

IQR Interquartile range, N Number, RIF Recurrent implantation failure, RPL Recurrent pregnancy loss

Using FC analysis, 18 endometrial leucocyte subpopulations were analysed. At baseline, we found no significant differences between the adenomyosis and the RPL and RIF groups (Table 2). In the adenomyosis group, following GnRH-a therapy, we observed a significant decrease in the percentage of classical monocytes, from 77% (IQR 71, 82) to 71% (IQR 65, 75) (adj. p = 0.030). However, neither non-classical nor intermediate monocytes changed significantly (adj. p = 0.825). None of the other leukocyte subpopulations showed significant changes following GnRH-a, as summarised in Table 3. Unadjusted p-values are shown in Additional file 2: Table S2.

Table 2.

Immune cell populations in the adenomyosis group (baseline), RPL and RIF group

| Adenomyosis | RIF | RPL | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IHC (N, %) | ||||

| PC | 0.860 | |||

| < 5/mm2 | 19 (95.0%) | 14 (93.3%) | 36 (90.0%) | |

| ≥ 5/mm2 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (6.7%) | 4 (10.0%) | |

| uNK cells | 0.0713 | |||

| < 300/mm2 | 12 (60.0%) | 14 (93.3%) | 29 (72.5%) | |

| ≥ 300/mm2 | 8 (40.0%) | 1 (6.7%) | 11 (27.5%) | |

| FC (median, IQR) | ||||

| % monocytes | 4.97 (3.87, 9.30) | 5.43 (3.86, 10.8) | 3.30 (1.88, 4.94) | 0.057 |

| % classical monocytes | 76.8 (71.3, 82.2) | 74.5 (70.1, 80.8) | 68.7 (57.8, 76.0) | 0.057 |

| % intermediate monocytes | 4.68 (2.69, 9.89) | 2.72 (1.54, 6.24) | 4.59 (1.84, 10.0) | 0.750 |

| % non-classical monocytes | 2.35 (0.820, 3.71) | 1.72 (0.405, 3.03) | 1.71 (0.668, 3.11) | 0.793 |

| % B cells | 1.21 (0.635, 4.90) | 1.37 (0.775, 1.75) | 0.61 (0.27, 1.86) | 0.332 |

| % T cells | 33.4 (25.0, 49.3) | 34.8 (28.3, 45.6) | 39.6 (24.3, 50.5) | 0.793 |

| % CD8 T cells | 40.4 (35.3, 50.1) | 43.8 (39.6, 59.2) | 53.2 (45.5, 60.8) | 0.057 |

| % CD4 T cells | 51.4 (42.1, 56.8) | 48.0 (36.7, 54.4) | 38.0 (30.9, 45.9) | 0.098 |

| % DP T cells | 3.59 (2.20, 5.44) | 2.52 (2.21, 3.50) | 3.04 (1.65, 4.47) | 0.701 |

| % DN T cells | 2.45 (1.94, 3.29) | 2.44 (1.31, 3.42) | 2.04 (1.31, 2.78) | 0.662 |

| % T(reg) cells | 5.22 (3.37, 7.97) | 5.89 (2.26, 7.48) | 5.01 (3.22, 7.35) | 0.809 |

| % NKT cells | 2.41 (1.24, 4.53) | 2.88 (2.09, 4.39) | 2.27 (1.77, 2.78) | 0.701 |

| % NK cells | 39.3 (28.8, 54.3) | 39.6 (25.3, 46.4) | 43.4 (32.0, 59.9) | 0.662 |

| % CD56 + CD16 − NK cells | 47.2 (39.9, 56.1) | 33.2 (27.3, 38.9) | 40.8 (33.4, 53.5) | 0.062 |

| % CD56 + CD16 low NK cells | 5.90 (5.15, 10.2) | 5.64 (4.44, 8.87) | 7.27 (4.97, 12.4) | 0.701 |

| % CD56brightCD16 − NK cells | 38.8 (31.1, 43.9) | 46.4 (33.9, 55.9) | 36.4 (25.9, 48.9) | 0.662 |

| % CD56 dimCD16 − NK cells | 1.22 (0.848, 2.12) | 1.04 (0.710, 1.65) | 1.06 (0.745, 1.83) | 0.750 |

| % CD56 dimCD16 high NK cells | 3.12 (2.23, 5.25) | 6.64 (2.78, 10.5) | 2.95 (2.06, 4.79) | 0.470 |

DN T cells Double-negative T cells, DP T cells Double-positive T cells, FC Flow cytometry, IHC Immunohistochemistry, IQR Interquartile range, N Number, NKT cells Natural killer T cells, PC Plasma cells, RIF Recurrent implantation failure, RPL Recurrent pregnancy loss, T(reg) cells T regulatory cells, uNK cells Uterine natural killer cells

*Adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg method

Table 3.

Immune cell populations in the adenomyosis group before and after GnRH-a therapy

| Before GnRH-a | After GnRH-a | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FC (median, IQR) | |||

| % monocytes | 4.97 (3.87, 9.30) | 5.34 (3.53, 8.13) | 1.000 |

| % classical monocytes | 76.8 (71.3, 82.2) | 71.1 (64.8, 75.0) | 0.030 |

| % intermediate monocytes | 4.68 (2.69, 9.89) | 5.86 (1.98, 13.3) | 0.825 |

| % non-classical monocytes | 2.35 (0.820, 3.71) | 2.70 (1.56, 3.54) | 0.825 |

| % B cells | 1.21 (0.635, 4.90) | 1.36 (0.410, 2.58) | 0.850 |

| % T cells | 33.4 (25.0, 49.3) | 35.7 (29.7, 45.2) | 0.825 |

| % CD8 T cells | 40.4 (35.3, 50.1) | 46.9 (36.4, 53.5) | 0.692 |

| % CD4 T cells | 51.4 (42.1, 56.8) | 44.3 (39.0, 53.9) | 0.825 |

| % DP T cells | 3.59 (2.20, 5.44) | 3.51 (2.36, 6.08) | 0.825 |

| % DN T cells | 2.45 (1.94, 3.29) | 2.24 (1.48, 3.60) | 0.691 |

| % T(reg) cells | 5.22 (3.37, 7.97) | 4.37 (2.91, 5.64) | 0.240 |

| % NKT cells | 2.41 (1.24, 4.53) | 3.38 (2.57, 4.84) | 0.825 |

| % NK cells | 39.3 (28.8, 54.3) | 40.8 [29.4, 52.8) | 0.922 |

| % CD56 + CD16 − NK cells | 47.2 (39.9, 56.1) | 50.6 (36.0, 56.5) | 1.000 |

| % CD56 + CD16 low NK cells | 5.90 (5.15, 10.2) | 6.73 (5.30, 10.3) | 0.850 |

| % CD56brightCD16 − NK cells | 38.8 (31.1, 43.9) | 28.7 (20.0, 39.4) | 0.382 |

| % CD56 dimCD16 − NK cells | 1.22 (0.848, 2.12) | 1.80 (1.20, 2.72) | 0.692 |

| % CD56 dimCD16 high NK cells | 3.12 (2.23, 5.25) | 3.28 (1.72, 11.9) | 0.825 |

DN T cells Double-negative T cells, DP T cells Double-positive T cells, FC Flow cytometry, GnRH-a Gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists, IHC Immunohistochemistry, IQR Interquartile range, N Number, NKT cells Natural killer T cells, PC Plasma cells, RIF Recurrent implantation failure, RPL Recurrent pregnancy loss, T(reg) cells T regulatory cells, uNK cells Uterine natural killer cells

*Adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg method

In the adenomyosis group, at baseline IHC showed elevated plasma cell concentrations consistent with chronic endometritis in 1/20 patients (5%), while uNK cells were elevated (≥ 300/mm2) in 8/20 patients (40%) (Table 2). Seven out of the eight women with elevated uNK cells were treated with intravenous soybean oil emulsion (100 mg Intralipid 20%, Fresenius®) according to our routine treatment scheme of one i.v. dosage every three months, followed by one dosage every two weeks when pregnancy was achieved. In the RPL and RIF group, 4/40 patients (10%) and 1/15 patient (6,7%), respectively, were diagnosed with chronic endometritis, while 11/40 (27.5%) and 1/15 (6.7%) had elevated uNK cells, respectively (Table 2). Of the 11 RPL patients with elevated uNK cells, 10 received Intralipid infusion according to our routine treatment scheme.

In the adenomyosis group, all twenty participants who completed the study underwent a FET immediately following GnRH-a treatment, resulting in ten pregnancies (50%). Seven of the twenty (35%) women had a clinical pregnancy defined as the presence of a positive heartbeat during sonography at gestational week 7. Three of the biochemical pregnancies and one of the clinical pregnancies did not progress further and resulted in early pregnancy loss before 10 gestational weeks. No ectopic pregnancies occurred. Of the six remaining pregnant patients, five have already delivered a live born infant, with one ongoing pregnancy. Of the patients who did not become pregnant (n = 10) or suffered a miscarriage at the first FET (n = 4) after GnRH-a therapy, ten underwent further FET cycles with or without repeated GnRH-a application. Eight out of these 10 (80%) became pregnant after one of these subsequent FETs. Of these, five delivered a live born infant, and three pregnancies are still ongoing.

Discussion

In this study, we were able to show that the endometrial leucocyte populations of women with adenomyosis are comparable to those of women with RPL and RIF. Previous studies have established that these differ in RPL and RIF in comparison to control populations. GnRH-a therapy, as commonly given to adenomyosis patients before FET, led to a significant decrease in the percentage of classical monocytes. Women with adenomyosis showed a remarkably high prevalence of elevated uNK cells diagnosed by IHC. In the adenomyosis group, clinical pregnancy rates (CPR) after FET following GnRH-a pre-treatment were comparable to the general CPR after FET in our clinic, 35% and 38%, respectively.

In this study, we analysed an extensive set of endometrial immune cells known to play a crucial role in implantation and early pregnancy, as described by previous studies [19, 30, 55–57]. We found no significant differences between women with adenomyosis compared to women with RPL or RIF. Although we did not include a healthy, fertile control group, previous studies have shown alterations in leucocyte subpopulations in RPL and RIF patients compared to fertile controls [19, 30, 55–57]. In particular, increased uNK cells have been observed both in women with RPL and RIF [52, 55, 56], while Treg cells have been reported to be decreased in RPL, RIF, and those with pre-eclampsia [26, 58, 59]. The distribution of the leucocyte subpopulations in our adenomyosis group was similar to the RPL and RIF group, giving support to the hypothesis that immunological alterations in the endometrium of women with adenomyosis might be involved in the pathogenesis of adenomyosis-associated infertility.

In women with adenomyosis, we observed a significant decrease in the percentage of classical monocytes after GnRH-a therapy. Human monocytes have traditionally been grouped into three main subsets based on the expression of surface markers: classical (CD14 + CD16 −), non-classical (CD14 dimCD16 +), and intermediate (CD14 + CD16 +) monocytes [60]. The subsets seem to be sequential developmental stages in monocyte differentiation, performing different functions. Classical monocytes are phagocytic and produce reactive oxygen species (ROS). They can differentiate into monocyte-derived macrophages and, when needed, into dendritic cells and play a crucial role in regulating inflammation and its resolution in tissues. Intermediate monocytes contribute to antigen presentation, apoptosis and cytokine secretion and exhibit conflicting functional roles in inflammation, with some studies suggesting pro-inflammatory functions while others indicate anti-inflammatory roles [61]. Non-classical monocytes are highly differentiated, contribute to Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis, and have been associated with patrolling behaviour along blood vessel walls and anti-inflammatory functions [60–64]. Recent studies, however, have shown a broader heterogeneity within monocytes, warranting a re-evaluation of the traditional classification. For example, emerging evidence has identified additional markers—such as CD11c, CD36, CCR2, HLA-DR, and CD64—that further refine the distinction between intermediate and non-classical monocytes [61, 65]. These markers enable better differentiation between intermediate and non-classical monocytes, suggesting that the traditional tripartite classification may underestimate monocyte heterogeneity [66, 67]. These newly identified subsets show distinct cytokine production profiles (e.g. TNF-α, IL-1β) and migratory capacities, which may influence disease progression or resolution. In our study, the percentage of classical monocytes decreased after GnRH-a therapy, but this was not accompanied by a significant increase in intermediate nor non-classical monocytes. This might be due to their differentiation either into other monocyte subsets, not expressing the surface markers CD14 and CD16 used in our flow cytometry, or into macrophages or dendritic cells. However, we observed a trend to increase in the intermediate monocyte population, and the range and standard deviation in this subpopulation were much higher after GnRH-a therapy. To confirm the observed changes and understand their biological relevance, absolute cell counts in addition to the percentages would be helpful, but it was not possible to obtain these data due to the properties of this kind of tissue samples. Previous studies have shown that the mononuclear phagocyte system not only plays an important role in the pathogenesis of adenomyosis itself but is also involved in adenomyosis-associated infertility [18, 68, 69]. However, the exact mechanisms remain to be elucidated. Monocytes are known to play an important role throughout pregnancy [70]. During implantation and early pregnancy, the maternal innate immune activity, including monocytes and macrophages, is increased [70]. Monocyte subsets seem to influence the course of pregnancy, as well. In fact, Melgert et al. have analysed monocyte subsets in the blood of pregnant and non-pregnant women and found a decreased number of classical monocytes and an increased number of intermediate monocytes in healthy pregnancy [71]. However, most studies focussed on monocyte levels and subsets in peripheral blood [63, 71–74]. Our study supports the theory that endometrial monocytes play an important role in adenomyosis-associated infertility and suggests that the positive effects of GnRH-a therapy prior to FET might be mediated through changes in monocyte subsets.

In fact, the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effect of GnRH-a pre-treatment before FET in women with adenomyosis, as reported by several studies [75–77], have been scarcely investigated thus far. A study by Khan et al. showed a reduction in endometrial macrophage infiltration and micro-vessel density after GnRH-a treatment in women with adenomyosis [43]. This indicates a reduced inflammatory reaction and angiogenesis, involving the mononuclear phagocyte system, as confirmed by our results.

In our study, IHC showed elevated uNK cells in as many as 40% of the women with adenomyosis. This is in line with previous studies, reporting an increased concentration of uNK cells in women with adenomyosis [20]. We found that the prevalence of elevated uNK cells in women with adenomyosis was comparable to the prevalence in women with RPL and RIF, cohorts that are known to have a higher prevalence of elevated uNK cells than fertile controls [52, 78–81]. Immunomodulatory therapies such as corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) or intralipids have been proposed to improve the outcomes in these populations [82]. Intralipids consist of a fat emulsion originally used for parenteral nutrition. Moreover, they seem to have immunomodulatory effects. Even though the exact molecular mechanism is still unclear, intralipids have been reported to activate the cAMP pathway that is associated with the NFκB pathway. The latter reduces excessive NK cell activation and cytokine production, modulating gene transcription [83, 84]. Some studies found a positive effect of intralipids on live birth rates in women with RPL or RIF and abnormal NK cell levels, but their use is still controversial and further studies are needed [84–88]. A retrospective cohort study by Henshaw et al. found higher live birth rates in women with adenomyosis treated with GnRH-a pre-treatment combined with intralipid therapy before FET than in those receiving GnRH-a pre-treatment alone [89]. However, the women in that study were not tested for uNK cell concentrations in the endometrium. Considering the results of our study, the improved live birth rates in the intralipid group reported by Henshaw et al. might be due to the positive effects of intralipids in those with elevated uNK cells. Based on our results of a markedly high prevalence of uNK cells in our cohort, we suggest performing an endometrial biopsy to test uNK cell concentrations in infertile adenomyosis patients undergoing IVF before performing the first FET, with an indication for immunomodulatory therapy in those with elevated uNKs.

Although specific data for adenomyosis are lacking, women with endometriosis are known to have a higher prevalence of autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, coeliac disease, multiple sclerosis, and inflammatory bowel disease [90]. At the same time, a negative influence of autoimmunity on pregnancy outcomes has been described [91–93]. In fact, endometriosis and autoimmune diseases both show a hyper-inflammatory milieu which negatively influences embryo implantation [94]. In a retrospective case–control study, Salmeri et al. found significantly lower cleavage and implantation rates, as well as CPR, in women with endometriosis and concomitant autoimmunity compared to women with endometriosis alone [94]. In this study, most of the included women with endometriosis and autoimmunity suffered from TAI (67%). However, other studies investigating the impact of TAI on ART outcomes found no significant effect on embryo quality, clinical pregnancy rate, and cumulative live birth rate (LBR) when adjusting for possible confounders including fertilisation method (IVF vs. ICSI) [95, 96]. Therefore, in our study, we excluded women suffering from concomitant autoimmune diseases, except for TAI.

In the present study, we analysed endometrial immune cell populations using FC and IHC, offering some preliminary insights into their distribution in women with adenomyosis under ART conditions and their changes after GnRH-a therapy. However, these two methods can focus only on limited immune cell types, not allowing us to investigate their level of activity or the cytokines secreted by them. Some studies have used single-cell transcriptome analysis to investigate the endometrial immune microenvironment in endometriosis [97, 98]. Huang et al. found a decreased cycle variation of total immune cells, NK cells, and T cells; higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines; and an altered expression of multiple ligand-receptor pairs as a possible explanation for the impaired endometrial receptivity in women with endometriosis and infertility [97]. Single-cell transcriptome analysis has also been applied in adenomyosis, but has mainly been used to study the pathogenesis of the disease, not focussing on the immune microenvironment and fertility [99–101]. Since in our study we were working with a limited tissue sample that had to be divided for FC analysis and IHC staining, it was not possible to add transcriptomic or proteomic analyses. Thus, future studies involving these methods are needed in order to obtain a more complete picture of the endometrial immune landscape in adenomyosis.

In the present study, the CPR in patients with adenomyosis after FET following GnRH-a pre-treatment was comparable to the general CPR after FET in our clinic (35% and 38%, respectively). In the literature, a lower CPR in patients with adenomyosis has been reported [33, 102]. Several studies have found a beneficial effect of GnRH-a therapy prior to FET in women with adenomyosis, improving both CPR and LBR [75–77]. Our results give support to these findings. However, in our study, seven out of the eight adenomyosis patients with elevated uNK cells received intralipids in addition to GnRH-a therapy, representing a possible confounder.

Moreover, in the adenomyosis group, the treatment with micronised progesterone after oocyte retrieval might have influenced the results of the first endometrial biopsy. In fact, Loreti et al. found different endometrial immune cell compositions comparing oral dydrogesterone and micronised vaginal progesterone for luteal phase support [103]. However, patients with adenomyosis have been reported not only to suffer from infertility but also from lower pregnancy and LBR and higher miscarriage rates, even following ART [6–8]. Several studies have established that GnRHa improve outcomes; the mechanism is not clear [6, 44–46]. Therefore, we were interested in studying the endometrial microenvironment during ART, specifically at the time of embryo transfer. We acknowledge that the endometrial microenvironment at the time of the first biopsy may not reflect the natural cycle; nonetheless, it reflects the environment in the endometrium at the time of a planned embryo transfer following IVF. Similarly, with the standardised add back therapy prior to the second biopsy, we simulated the hormonal conditions at the time of FET following downregulation with GnRH-a. Thus, the present study does not elucidate the endometrial immune cell composition during the natural cycle in adenomyosis but gives some evidence on its composition and changes during GnRHa as part of ART.

Further limitations of the present study include the small number of patients, which limits the interpretability and generalisability of our results. Moreover, we did not include a healthy, fertile control group, as it was ethically unacceptable to perform an endometrial biopsy without medical indication. Therefore, our results need to be interpreted with caution. However, we evaluated RPL patients versus fertile controls in a previous study, establishing cut-off values for chronic endometritis and uterine NK cells [52]. Due to the extensive set of endometrial immune cells analysed, the results might be influenced by multiple testing. However, we accounted for this in the statistical analysis, performing a correction for multiple testing.

While most previous studies analysing immune cell populations in patients with adenomyosis concentrated on peripheral blood, we investigated their distribution in the endometrium, where implantation actually takes place. This represents one of the strengths of our study. Moreover, all included adenomyosis patients fulfilled either two or more direct diagnostic criteria for adenomyosis or both direct and indirect criteria as defined by the MUSA group [47], adding to the reliability of the diagnosis.

Conclusions

According to our data, women with adenomyosis show a similar endometrial immune profile as women suffering from RPL and RIF, supporting an immunological pathophysiological mechanism of adenomyosis-associated infertility. The beneficial effect of GnRH-a therapy prior to FET in women with adenomyosis may be mediated through positive effects on the mononuclear phagocyte system. Based on the high prevalence of elevated uNK cells in patients with adenomyosis, we suggest testing women with adenomyosis undergoing ART before performing FET.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Antibodies used for staining in flow cytometry.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Unadjusted p-values for comparisons of immune cell populations (flow cytometry).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Medical Science Fund (MFF) for funding this project.

Abbreviations

- RRL

Recurrent pregnancy loss

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- Th17

T helper 17 cells

- Treg

T regulatory cells

- NK

Natural killer cells

- uNK

Uterine natural killer cells

- pNK

Peripheral natural killer cells

- GnRH-a

Gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists

- ART

Assisted reproductive technologies

- FET

Frozen embryo transfer

- RIF

Recurrent implantation failure

- IVF

In vitro fertilisation

- FC

Flow cytometry

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- TAI

Thyroid autoimmunity

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- IQR

Interquartile range

- CPR

Clinical pregnancy rate

- IVIG

Intravenous immunoglobulins

- LBR

Life birth rate

Authors’ contributions

A.Z. contributed to conceptualization, sample/data collection, data management and interpretation, writing. C.K. contributed to conceptualization, laboratory analysis, data interpretation and writing. M.F. contributed to laboratory analysis, data collection, data interpretation and writing. E.G. contributed to laboratory analysis, data collection and data interpretation. E.R. contributed to sample/data collection, data management and interpretation and writing. A.-S.B. contributed to sample/data collection, data management and interpretation and writing. K.F. contributed to sample/data collection and writing. S.S. contributed to sample/data collection, data management and writing. P.R. contributed to statistical analysis, data interpretation and writing. B.T. contributed to conceptualization, sample/data collection, data interpretation, writing and supervision. B.S. contributed to conceptualization, sample/data collection, data interpretation, writing and supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This academic study was funded by the Medical Science Fund (MFF, Project 342).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files and can be made available on request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria (EK Nr: 1075/2020). Oral and written informed consent was obtained by all study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Van den Bosch T, Dueholm M, Leone FPG, Valentin L, Rasmussen CK, Votino A, et al. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe sonographic features of myometrium and uterine masses: a consensus opinion from the Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46:284–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Champaneria R, Abedin P, Daniels J, Balogun M, Khan KS. Ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review comparing test accuracy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:1374–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Donato N, Montanari G, Benfenati A, Leonardi D, Bertoldo V, Monti G, et al. Prevalence of adenomyosis in women undergoing surgery for endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;181:289–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lazzeri L, Di Giovanni A, Exacoustos C, Tosti C, Pinzauti S, Malzoni M, et al. Preoperative and Postoperative Clinical and Transvaginal Ultrasound Findings of Adenomyosis in Patients With Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2014;21:1027–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu O, Schulze-Rath R, Grafton J, Hansen K, Scholes D, Reed SD. Adenomyosis incidence, prevalence and treatment: United States population-based study 2006–2015. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:94.e1-94.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vercellini P, Consonni D, Dridi D, Bracco B, Frattaruolo MP, Somigliana E. Uterine adenomyosis and in vitro fertilization outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:964–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Younes G, Tulandi T. Effects of adenomyosis on in vitro fertilization treatment outcomes: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:483-490.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanekova V, Woodman RJ, Tremellen K. The rate of euploid miscarriage is increased in the setting of adenomyosis. Hum Reprod Open. 2018;2018:hoy011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Upson K, Missmer SA. Epidemiology of adenomyosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2020;38:89–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vannuccini S, Tosti C, Carmona F, Huang SJ, Chapron C, Guo S-W, et al. Pathogenesis of adenomyosis: an update on molecular mechanisms. Reprod Biomed Online. 2017;35:592–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cakmak H, Guzeloglu-Kayisli O, Kayisli UA, Arici A. Immune-endocrine interactions in endometriosis. Front Biosci. 2009;1:429–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urabe M, Yamamoto T, Kitawaki J, Honjo H, Okada H. Estrogen biosynthesis in human uterine adenomyosis. Acta Endocrinol. 1989;121:259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitawaki J, Noguchi T, Amatsu T, Maeda K, Tsukamoto K, Yamamoto T, et al. Expression of aromatase cytochrome P450 protein and messenger ribonucleic acid in human endometriotic and adenomyotic tissues but not in normal endometrium. Biol Reprod. 1997;57:514–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ezaki K, Motoyama H, Sasaki H. Immunohistologic localization of estrone sulfatase in uterine endometrium and adenomyosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(5 Pt 1):815–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y-J, Li H-Y, Huang C-H, Twu N-F, Yen M-S, Wang P-H, et al. Oestrogen-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition of endometrial epithelial cells contributes to the development of adenomyosis. J Pathol. 2010;222:261–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nie J, Lu Y, Liu X, Guo S-W. Immunoreactivity of progesterone receptor isoform B, nuclear factor kappaB, and IkappaBalpha in adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:886–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehasseb MK, Panchal R, Taylor AH, Brown L, Bell SC, Habiba M. Estrogen and progesterone receptor isoform distribution through the menstrual cycle in uteri with and without adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(2228–35):2235.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao Y, Yang D, Cai S, Yang L, Yu S, Geng Q, et al. Adenomyosis associated infertility: an update on immunological perspective. Reprod Biomed Online. 2024;50(5):104703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robertson SA, Moldenhauer LM, Green ES, Care AS, Hull ML. Immune determinants of endometrial receptivity: a biological perspective. Fertil Steril. 2022;117:1107–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tremellen KP, Russell P. The distribution of immune cells and macrophages in the endometrium of women with recurrent reproductive failure. II: adenomyosis and macrophages. J Reprod Immunol. 2012;93:58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wira CR, Rodriguez-Garcia M, Patel MV. The role of sex hormones in immune protection of the female reproductive tract. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:217–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manaster I, Mizrahi S, Goldman-Wohl D, Sela HY, Stern-Ginossar N, Lankry D, et al. Endometrial NK cells are special immature cells that await pregnancy. J Immunol. 2008;181:1869–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siewiera J, Gouilly J, Hocine H-R, Cartron G, Levy C, Al-Daccak R, et al. Natural cytotoxicity receptor splice variants orchestrate the distinct functions of human natural killer cell subtypes. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michel T, Poli A, Cuapio A, Briquemont B, Iserentant G, Ollert M, et al. Human CD56bright NK cells: An update. J Immunol. 2016;196:2923–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moffett A, Colucci F. Uterine NK cells: active regulators at the maternal-fetal interface. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1872–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosseini A, Dolati S, Hashemi V, Abdollahpour-Alitappeh M, Yousefi M. Regulatory T and T helper 17 cells: Their roles in preeclampsia. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:6561–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vignali DAA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:523–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:297–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jena MK, Nayak N, Chen K, Nayak NR. Role of macrophages in pregnancy and related complications. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2019;67:295–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun A-S, Vomstein K, Reiser E, Tollinger S, Kyvelidou C, Feil K, et al. NK and T cell subtypes in the endometrium of patients with recurrent pregnancy loss and recurrent implantation failure: Implications for pregnancy success. J Clin Med. 2023;12:5585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gui T, Chen C, Zhang Z, Tang W, Qian R, Ma X, et al. The disturbance of TH17-Treg cell balance in adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:506–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang W-J, Hao C-F, Qu Q-L, Wang X, Qiu L-H, Lin Q-D. The deregulation of regulatory T cells on interleukin-17-producing T helper cells in patients with unexplained early recurrent miscarriage. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:2591–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horton J, Sterrenburg M, Lane S, Maheshwari A, Li TC, Cheong Y. Reproductive, obstetric, and perinatal outcomes of women with adenomyosis and endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2019;25:592–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bulmer JN, Jones RK, Searle RF. Intraepithelial leukocytes in endometriosis and adenomyosis: comparison of eutopic and ectopic endometrium with normal endometrium. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:2910–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scheerer C, Bauer P, Chiantera V, Sehouli J, Kaufmann A, Mechsner S. Characterization of endometriosis-associated immune cell infiltrates (EMaICI). Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;294:657–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koo HS, Kwak-Kim J, Yi HJ, Ahn HK, Park CW, Cha SH, et al. Resistance of uterine radial artery blood flow was correlated with peripheral blood NK cell fraction and improved with low molecular weight heparin therapy in women with unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2015;73:175–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plaisier M, Dennert I, Rost E, Koolwijk P, van Hinsbergh VWM, Helmerhorst FM. Decidual vascularization and the expression of angiogenic growth factors and proteases in first trimester spontaneous abortions. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:185–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang J-H, Chen M-J, Chen H-F, Lee T-H, Ho H-N, Yang Y-S. Decreased expression of killer cell inhibitory receptors on natural killer cells in eutopic endometrium in women with adenomyosis. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1974–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones RK, Bulmer JN, Searle RF. Phenotypic and functional studies of leukocytes in human endometrium and endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update. 1998;4:702–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee SK, Kim CJ, Kim D-J, Kang J-H. Immune cells in the female reproductive tract. Immune Netw. 2015;15:16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Y-J, Li H-Y, Chang Y-L, Yuan C-C, Tai L-K, Lu KH, et al. Suppression of migratory/invasive ability and induction of apoptosis in adenomyosis-derived mesenchymal stem cells by cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(6):1972–9, 1979.e1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Zou S, Xia X, Zhang S. Human Adenomyosis Endometrium Stromal Cells Secreting More Nerve Growth Factor: Impact and Effect. Reprod Sci. 2015;22:1073–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khan KN, Kitajima M, Hiraki K, Fujishita A, Sekine I, Ishimaru T, et al. Changes in tissue inflammation, angiogenesis and apoptosis in endometriosis, adenomyosis and uterine myoma after GnRH agonist therapy. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:642–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maubon A, Faury A, Kapella M, Pouquet M, Piver P. Uterine junctional zone at magnetic resonance imaging: a predictor of in vitro fertilization implantation failure. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36:611–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thalluri V, Tremellen KP. Ultrasound diagnosed adenomyosis has a negative impact on successful implantation following GnRH antagonist IVF treatment. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:3487–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Youm HS, Choi YS, Han HD. In vitro fertilization and embryo transfer outcomes in relation to myometrial thickness. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2011;28:1135–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harmsen MJ, Van den Bosch T, de Leeuw RA, Dueholm M, Exacoustos C, Valentin L, et al. Consensus on revised definitions of Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) features of adenomyosis: results of modified Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2022;60:118–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Definitions of infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Evaluation and treatment of recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:1103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cimadomo D, Craciunas L, Vermeulen N, Vomstein K, Toth B. Definition, diagnostic and therapeutic options in recurrent implantation failure: an international survey of clinicians and embryologists. Hum Reprod. 2021;36:305–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun Y, Zhang Y, Ma X, Jia W, Su Y. Determining diagnostic criteria of unexplained recurrent implantation failure: A retrospective study of two vs three or more implantation failure. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:619437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kuon R-J, Weber M, Heger J, Santillán I, Vomstein K, Bär C, et al. Uterine natural killer cells in patients with idiopathic recurrent miscarriage. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2017;78:12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Santoro A, Travaglino A, Inzani F, Angelico G, Raffone A, Maruotti GM, et al. The role of plasma cells as a marker of chronic endometritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomedicines. 2023;11:1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benjamini Y, Yosef H. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1995;1995(57):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marron K, Walsh D, Harrity C. Detailed endometrial immune assessment of both normal and adverse reproductive outcome populations. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36:199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lachapelle MH, Miron P, Hemmings R, Roy DC. Endometrial T, B, and NK cells in patients with recurrent spontaneous abortion. Altered profile and pregnancy outcome. J Immunol. 1996;156:4027–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu S, Huang C, Lian R, Diao L, Zhang X, Cai S, et al. Establishment of reference intervals of endometrial immune cells during the mid-luteal phase. J Reprod Immunol. 2023;156:103822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee SK, Kim JY, Lee M, Gilman-Sachs A, Kwak-Kim J. Th17 and regulatory T cells in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2012;67:311–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diao L-H, Li G-G, Zhu Y-C, Tu W-W, Huang C-Y, Lian R-C, et al. Human chorionic gonadotropin potentially affects pregnancy outcome in women with recurrent implantation failure by regulating the homing preference of regulatory T cells. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2017;77:12618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cousins FL, Kirkwood PM, Saunders PTK, Gibson DA. Evidence for a dynamic role for mononuclear phagocytes during endometrial repair and remodelling. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cormican S, Griffin MD. Human monocyte subset distinctions and function: Insights from gene expression analysis. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kapellos TS, Bonaguro L, Gemünd I, Reusch N, Saglam A, Hinkley ER, et al. Human monocyte subsets and phenotypes in major chronic inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pflitsch C, Feldmann CN, Richert L, Hagen S, Diemert A, Goletzke J, et al. In-depth characterization of monocyte subsets during the course of healthy pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 2020;141:103151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Amengual J, Barrett TJ. Monocytes and macrophages in atherogenesis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2019;30:401–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ruder AV, Wetzels SMW, Temmerman L, Biessen EAL, Goossens P. Monocyte heterogeneity in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2023;119:2033–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guilliams M, Mildner A, Yona S. Developmental and functional heterogeneity of monocytes. Immunity. 2018;49:595–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Villani A-C, Satija R, Reynolds G, Sarkizova S, Shekhar K, Fletcher J, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals new types of human blood dendritic cells, monocytes, and progenitors. Science. 2017;356:eaah4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maclean A, Barzilova V, Patel S, Bates F, Hapangama DK. Characterising the immune cell phenotype of ectopic adenomyosis lesions compared with eutopic endometrium: A systematic review. J Reprod Immunol. 2023;157:103925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ulukus EC, Ulukus M, Seval Y, Zheng W, Arici A. Expression of interleukin-8 and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 in adenomyosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:2958–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.True H, Blanton M, Sureshchandra S, Messaoudi I. Monocytes and macrophages in pregnancy: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Immunol Rev. 2022;308:77–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Melgert BN, Spaans F, Borghuis T, Klok PA, Groen B, Bolt A, et al. Pregnancy and preeclampsia affect monocyte subsets in humans and rats. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e45229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Comins-Boo A, Valdeolivas L, Pérez-Pla F, Cristóbal I, Subhi-Issa N, Domínguez-Soto Á, et al. Immunophenotyping of peripheral blood monocytes could help identify a baseline pro-inflammatory profile in women with recurrent reproductive failure. J Reprod Immunol. 2022;154:103735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Al-ofi E, Coffelt SB, Anumba DO. Monocyte subpopulations from pre-eclamptic patients are abnormally skewed and exhibit exaggerated responses to Toll-like receptor ligands. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Faas MM, Spaans F, De Vos P. Monocytes and macrophages in pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Front Immunol. 2014;5:298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Park CW, Choi MH, Yang KM, Song IO. Pregnancy rate in women with adenomyosis undergoing fresh or frozen embryo transfer cycles following gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2016;43:169–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Niu Z, Chen Q, Sun Y, Feng Y. Long-term pituitary downregulation before frozen embryo transfer could improve pregnancy outcomes in women with adenomyosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29:1026–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hou X, Xing J, Shan H, Mei J, Sun Y, Yan G, et al. The effect of adenomyosis on IVF after long or ultra-long GnRH agonist treatment. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;41:845–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen X, Zhang T, Liu Y, Cheung WC, Zhao Y, Wang CC, et al. Uterine CD56+ cell density and euploid miscarriage in women with a history of recurrent miscarriage: A clinical descriptive study. Eur J Immunol. 2021;51:487–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.El-Azzamy H, Dambaeva SV, Katukurundage D, Salazar Garcia MD, Skariah A, Hussein Y, et al. Dysregulated uterine natural killer cells and vascular remodeling in women with recurrent pregnancy losses. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2018;80:e13024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Quenby S, Kalumbi C, Bates M, Farquharson R, Vince G. Prednisolone reduces preconceptual endometrial natural killer cells in women with recurrent miscarriage. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:980–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Von Woon E, Greer O, Shah N, Nikolaou D, Johnson M, Male V. Number and function of uterine natural killer cells in recurrent miscarriage and implantation failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2022;28:548–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Díaz-Hernández I, Alecsandru D, García-Velasco JA, Domínguez F. Uterine natural killer cells: from foe to friend in reproduction. Hum Reprod Update. 2021;27:720–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sfakianoudis K, Rapani A, Grigoriadis S, Pantou A, Maziotis E, Kokkini G, et al. The role of uterine natural killer cells on recurrent miscarriage and recurrent implantation failure: From pathophysiology to treatment. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Coulam CB. Intralipid treatment for women with reproductive failures. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2021;85:e13290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Canella PRBC, Barini R, Carvalho P de O, Razolli DS. Lipid emulsion therapy in women with recurrent pregnancy loss and repeated implantation failure: The role of abnormal natural killer cell activity. J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25:2290–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Meng L, Lin J, Chen L, Wang Z, Liu M, Liu Y, et al. Effectiveness and potential mechanisms of intralipid in treating unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;294:29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kumar P, Marron K, Harrity C. Intralipid therapy and adverse reproductive outcome: is there any evidence? Reprod Fertil. 2021;2:173–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Woon EV, Day A, Bracewell-Milnes T, Male V, Johnson M. Immunotherapy to improve pregnancy outcome in women with abnormal natural killer cell levels/activity and recurrent miscarriage or implantation failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Reprod Immunol. 2020;142:103189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Henshaw J, Tremellen K. Intralipid infusion therapy as an adjunct treatment in women experiencing adenomyosis-related infertility. Ther Adv Reprod Health. 2023;17:26334941231181256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shigesi N, Kvaskoff M, Kirtley S, Feng Q, Fang H, Knight JC, et al. The association between endometriosis and autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2019;25:486–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Andreoli L, Chighizola CB, Iaccarino L, Botta A, Gerosa M, Ramoni V, et al. Immunology of pregnancy and reproductive health in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Update from the 11th International Conference on Reproduction, Pregnancy and Rheumatic Diseases. Auto Immun Rev. 2023;22:103259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Singh M, Wambua S, Lee SI, Okoth K, Wang Z, Fazla F, et al. Autoimmune diseases and adverse pregnancy outcomes: an umbrella review. Lancet. 2023;402(Suppl 1):S84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tan Y, Yang S, Liu Q, Li Z, Mu R, Qiao J, et al. Pregnancy-related complications in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2022;132:102864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Salmeri N, Gennarelli G, Vanni VS, Ferrari S, Ruffa A, Rovere-Querini P, et al. Concomitant autoimmunity in endometriosis impairs endometrium-embryo crosstalk at the implantation site: a multicenter case-control study. J Clin Med. 2023;12(10):3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Huang N, Chen L, Yan Z, Chi H, Qiao J. Impact of thyroid autoimmunity on the cumulative live birth rates after IVF/ICSI treatment cycles. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024;24:230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rao M, Zeng Z, Zhang Q, Su C, Yang Z, Zhao S, et al. Thyroid autoimmunity is not associated with embryo quality or pregnancy outcomes in euthyroid women undergoing assisted reproductive technology in China. Thyroid. 2023;33:380–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Huang X, Wu L, Pei T, Liu D, Liu C, Luo B, et al. Single-cell transcriptome analysis reveals endometrial immune microenvironment in minimal/mild endometriosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2023;212:285–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ma J, Zhang L, Zhan H, Mo Y, Ren Z, Shao A, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of endometriosis provides insights into fibroblast fates and immune cell heterogeneity. Cell Biosci. 2021;11:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yildiz S, Kinali M, Wei JJ, Milad M, Yin P, Adli M, et al. Adenomyosis: single-cell transcriptomic analysis reveals a paracrine mesenchymal-epithelial interaction involving the WNT/SFRP pathway. Fertil Steril. 2023;119:869–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chen T, Xu Y, Xu X, Wang J, Qiu Z, Yu Y, et al. Comprehensive transcriptional atlas of human adenomyosis deciphered by the integration of single-cell RNA-sequencing and spatial transcriptomics. Protein Cell. 2024;15:530–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu Z, Sun Z, Liu H, Niu W, Wang X, Liang N, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of eutopic endometrium and ectopic lesions of adenomyosis. Cell Biosci. 2021;11:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nirgianakis K, Kalaitzopoulos DR, Schwartz ASK, Spaanderman M, Kramer BW, Mueller MD, et al. Fertility, pregnancy and neonatal outcomes of patients with adenomyosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;42:185–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Loreti S, Thiele K, De Brucker M, Olsen C, Centelles-Lodeiro J, Bourgain C, et al. Oral dydrogesterone versus micronized vaginal progesterone for luteal phase support: a double-blind crossover study investigating pharmacokinetics and impact on the endometrium. Hum Reprod. 2024;39:403–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Antibodies used for staining in flow cytometry.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Unadjusted p-values for comparisons of immune cell populations (flow cytometry).

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files and can be made available on request.