Abstract

Purpose

To identify the core competencies of social workers in palliative care.

Method

A systematic review of 19 high-quality studies published in English and Chinese up to February 2025 was conducted.

Results

The study identified five core competencies—Ethics, Coordination, Assessment, Resource Allocation, and Education—establishing the core competencies of social workers. They serve as interdisciplinary coordinators, communication facilitators, and educators, addressing psychosocial, emotional, and environmental challenges while navigating systemic resource constraints. The framework emphasizes ongoing assessment, resource allocation, and educational interventions, positioning social workers as system navigators and existential educators essential to compassionate, patient- and family-centered care.

Discussion

E-CARE framework equips social workers to navigate complex care ecosystems, foster team cohesion, mediate conflicts, advocate for patient autonomy, destigmatize end-of-life discussions, and promote resilience through ongoing training, particularly in resource-constrained settings.

Keywords: Social work, Core competencies, Hospice, Palliative care, End-of-life care

Introduction

The global demand for palliative care has surged significantly, driven by demographic aging and the rising burden of chronic diseases. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 56.8 million people, including 25.7 million in the last year of life, are in need of palliative care each year, while only about 14% of people have access to this service worldwide [1]. This trend is particularly acute in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where two-thirds of the world's elderly will reside by 2050, exacerbating health-related suffering that palliative care could alleviate [2]. Chronic diseases such as cardiovascular conditions, cancer, and diabetes are major contributors to this demand. For instance, cancer-related deaths are expected to rise from 143,638 to 208,636 in the coming years, underscoring the urgent need for integrated palliative care services [3]. Evidence suggests that approximately 75% of individuals at the end-of-life stage could benefit from palliative care, highlighting the necessity of a holistic approach that addresses not only physical symptoms but also psychosocial and emotional needs [4].

Social workers were viewed to play a pivotal role in palliative care, serving as essential interdisciplinary professionals who bridge the critical gap between medical treatment and psychosocial support [5]. Research demonstrates that interdisciplinary teams incorporating social workers significantly enhance family satisfaction, particularly in two key areas: facilitating effective communication and optimizing care coordination [6]. Furthermore, empirical evidence indicates that patients receiving integrated psychosocial support experience measurable improvements in well-being, with a 20–30% reduction in anxiety and depression levels [7]. However, substantial implementation challenges persist, particularly in crucial domains such as advance care planning and symptom management, where implementation rates remain critically low at approximately 30% [8]. This significant disparity between established best practices and actual clinical implementation highlights the urgent need to systematically examine and strengthen the core competencies of palliative care social workers, with the ultimate goal of enhancing service quality and improving patient outcomes [9]. Addressing these persistent gaps is particularly crucial in light of the increasing demand for holistic, compassionate care that upholds the dignity and respects the unique needs of both patients and their families [10].

The concept of competency in social work is a multidimensional and dynamic construct, encompassing the integration of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values to achieve professional objectives [11, 12]. The Social Work Education Committee defines social work competencies as the purposeful and professional integration and application of knowledge, values, and skills to enhance well-being, guided by social work values [13]. In interdisciplinary healthcare training, Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME) defines competency as the proficient application of knowledge, skills, and behaviors in role fulfillment, characterized by multidimensionality, context-dependence, and developmental adaptability [14]. Within the social work field in palliative care, countries such as the United States, the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) and South Korea have established competencies frameworks comprising three core dimensions: 1) knowledge (e.g., symptom recognition and pain management), 2) skills (e.g., risk assessment and interdisciplinary collaboration), and 3) values (e.g., ethical awareness of death and empathetic practice) [15–17].

While numerous countries and regions have developed competency frameworks for palliative social work, a significant theory–practice gap persists. Research indicates that social workers in palliative care often feel underprepared in critical areas, particularly in communication skills and cultural competence [18]. This challenge has been further compounded by evolving internal and external demands, including the essential competencies developed during the COVID- 19 pandemic, such as crisis intervention skills, telehealth proficiency, ethical decision-making in complex situations, and emergency resource coordination [19, 20]. In response to these challenges, this study seeks to bridge existing gaps by systematically analyzing core competencies in palliative social work practice. The research specifically addresses two pivotal questions: (1) What core competencies are essential for social workers to effectively support end-of-life patients and their families? and (2) How do these competencies impact the quality of palliative care delivery?

Methods

Search strategy

The databases searched were CNKI, Wanfang Data, VIP, PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane, and APA. To maximize coverage, retrieval strategies employed a mix of thesaurus terms, free-text terms, and broad-based terms [21]. The search terms used included “social work” and “social worker” for social work; “hospice”, “palliative”, and “end of life” for end-of-life care; and “competency”, “ability”, “skill”, “value”, and “knowledge” for competencies. For the retrieval of competencies, an operational definition was used to split it to ensure the comprehensive coverage of the literature. For literature in Chinese, equivalent terms were employed, as shown in Table 1. Due to the bilingual nature of the search, Chinese databases (CNKI, Wanfang Data, and VIP) were divided into separate English and Chinese search approaches. Advanced search techniques, such as Boolean operators were used to develop a tailored search strategy. The search strategies for each database are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

The search terms used

| Search terms for social work | Search terms for end of life care | Search terms for competence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ENGLISH | social work、social worker | hospice、palliative、end of life | competence、competency、 skill 、value 、knowledge 、ability |

| CHINESE | 社会工作、社工、社会工作者 | 安宁疗护、临终关怀、安宁缓和、缓和医疗、临终护理 | 能力、核心能力、职能、技能、知识、价值观 |

Table 2.

Search strategies for each database

| CNKI | (社会工作 + 社工 + 社会工作者) * (安宁疗护 + 临终关怀 + 安宁缓和 + 缓和医疗 + 临终护理) * (能力 + 核心能力 + 职能 + 知识 + 技能 + 价值观) |

|---|---|

| WanFang | 主题:(社会工作 OR 社工 OR 社会工作者) and 主题:(安宁疗护 OR 临终关怀 OR 安宁缓和 OR 缓和医疗 OR 临终护理) and 主题:((能力 OR 核心能力 OR 职能 OR 知识 OR 技能 OR 价值观)) |

| VIP | 任意字段:(社会工作 OR 社工 OR 社会工作者) and 任意字段:(安宁疗护 OR 临终关怀 OR 安宁缓和 OR 缓和医疗 OR 临终护理) and 任意字段:((能力 OR 核心能力 OR 职能 OR 知识 OR 技能 OR 价值观)) |

| Web of Science | ((TS = ("social work"OR"social worker")) AND TS = (hospice OR palliative OR"end of life")) AND TS = (competenc* OR skill OR value OR knowledge OR ability) |

| Scopus | ("social work"OR"social worker") AND (hospice OR palliative OR"end of life")) AND (competenc* OR skill OR value OR knowledge OR ability) |

| PubMed | (("social work"[Title/Abstract] OR"social worker"[Title/Abstract]) AND (hospice[Title/Abstract] OR palliative[Title/Abstract] OR"end of life"[Title/Abstract])) AND (competenc*[Title/Abstract] OR skill[Title/Abstract] OR value[Title/Abstract] OR knowledge[Title/Abstract] OR ability[Title/Abstract]) |

| APA | Abstract:"social work"OR Abstract:"social worker"AND Abstract: hospice OR Abstract: palliative OR Abstract:"end of life"AND Abstract: competenc* OR Abstract: skill OR Abstract: value OR Abstract: knowledge OR Abstract: ability |

| Embase | ("social work"OR"social worker") AND (hospice OR palliative OR end of life)) AND (competenc* OR skill OR value OR knowledge OR ability) |

| Cochrane | ("social work"OR"social worker") AND (hospice OR palliative OR end of life)) AND (competenc* OR skill OR value OR knowledge OR ability) |

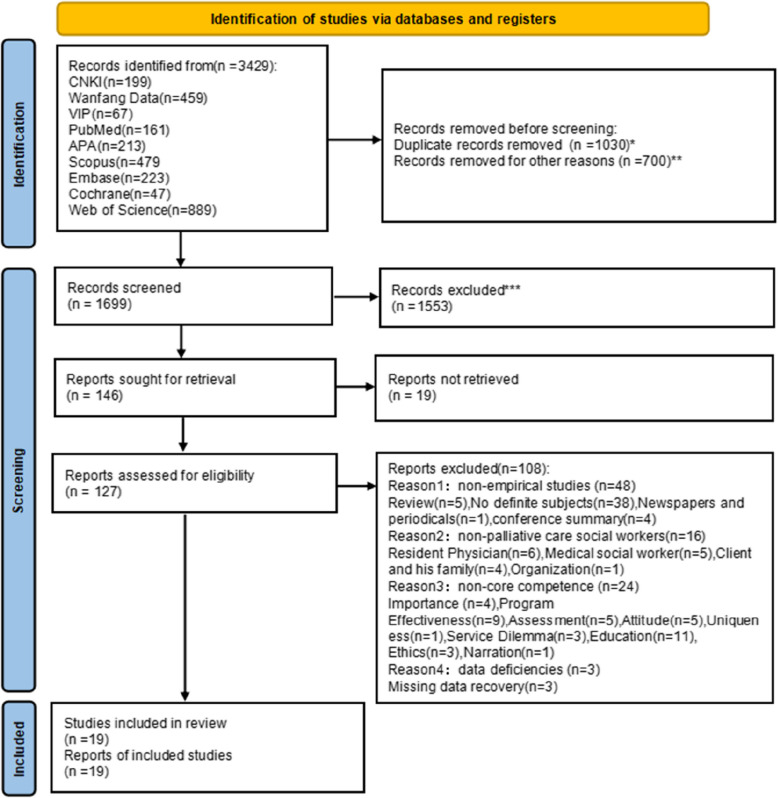

As Fig. 1 shows, the PRISMA flow chart details the search and selection process. Initially, 1,030 duplicate records and 700 irrelevant articles-type records (including 241 book reviews, 208 books, etc.) were removed, leaving 1699 for screening. Through manual screening of titles, abstracts, and keywords, 1,553 reports were excluded: 891 are unrelated to social work (e.g., research on groups such as nurses), 196 are unrelated to palliative care, and 33 are unrelated to core competencies. This left 146 reports for eligibility assessment, while 19 articles were excluded as full-text articles were not retrievable. After full-text review, 108 ineligible reports were removed: 48 non-empirical studies, 16 irrelevant to palliative social workers, 24 irrelevant to core competencies, and 3 with incomplete data. Finally, 19 articles were included in the study.

Fig. 1.

The PRISMA flowchart of data screening. 2. Duplicate records removed in each database are as follows: CNKI(n = 0), WanfangData(n = 25), VIP(n = 48), PubMed(n = 78), APA(n = 26), Scopus(n = 229), Embase(n = 151), Cochrane(n = 4), Web of Science(n = 469). Records removed for Ineligible types is as follows: book section(n = 241), book(n = 208), conference(n = 33), thesis(n = 217), newspaper(n = 1). Records excluded by manual reading of titles, abstracts, and keywords is as follows: non-social workers(n = 891), non-palliative care(n = 196), non-core competence(n = 334), non-coincidence type study(n = 132), non-social workers: The criteria for non-social workers refers to the research whose objects are not social workers, but nurses, residents, and nursing workers, and those in the fields of medicine, diagnostics, pharmacy, and oncology where the words “staff”, “staff”, and “group” include social workers but do not focus on social workers. Non-core competence: The criteria of non-core competence refers to the research whose content does not involve core competence defined by “competence”, “knowledge”, “skills” and “values”, “attitudes”, “ethics”, “functions” and “roles”, including policy advice and advocacy, needs assessment, feasibility, verification of the need for social workers, and population census. Non-palliative care: The criteria for non-palliative care refers to the research topic was not related to “hospice care” “palliative care” “end-of-life care”. Non-coincidence type study: The criteria for non-coincidence type study refers to the research types are literature review, book review and conference summary

Quality appraisal

To ensure methodological rigor in synthesizing heterogeneous studies, we adopted the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) to evaluate 19 empirical articles meeting predefined criteria. Inclusion criteria comprised: 1) peer-reviewed articles published in English or Chinese by February 2025; 2) empirical studies explicitly addressing social workers'roles/competencies in palliative care; 3) studies with complete data, clear conclusions, and direct relevance to review objectives. Duplicate datasets were excluded to ensure unique contributions. Two authors independently conducted quality assessments by using MMAT's standardized criteria, resolving discrepancies through consensus. Studies scoring below 60% on methodological rigor (e.g., sampling adequacy, analytical coherence, ethical considerations) were excluded to ensure synthesis validity. Table 3 documents each study's methodological strengths and limitations, focusing on design appropriateness, data triangulation in mixed-methods studies, and interpretative validity. This screening process balanced inclusivity with critical appraisal, enhancing the review's reliability while accounting for methodological diversity across qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods designs.

Table 3.

The methodological quality of the included studies

| 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 5.5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arnold, E. M., Artin, et al. (2006) [22] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Carmel,P. (2001) [23] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Csikai EL,Raymer M. (2005) [24] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Fantus S, Cole R, Hawkins L, et al.(2023) [25] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Guan T, Brintzenhofeszoc K, Middleton A,et al.(2024) [26] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Guo MR, Guo JH, Liang K, et al.(2024) [27] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Head B, Peters B, Middleton A.et al.(2019) [28] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Jang SM, Lim JW, Choi JE.(2024) [29] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Jones B. L. (2006) [30] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Kramer B. J. (2013) [31] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Lacey D. (2005) [32] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Liu XY.(2014) [33] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Lv QL, Cheng HL.(2018) [34] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Prieto-Lobato JM, De la Rosa-Gimeno P, Rodríguez-Sumaza C, et al. (2023) [35] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Sheldon FM.(2000) [36] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Supiano KP, Berry PH.(2013) [37] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Waldron M, Kernohan WG, Hasson F.(2013) [38] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Washington KT, Albright DL, Parker Oliver D,et al.(2016) [39] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Xu LY, Weng ZC, Mo N.(2019) [40] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Data extraction

To ensure that all relevant information related to the review questions was systematically captured, data extraction sheets were used to organize key details into a standardized table (Tables 4 and 5). These sheets, adapted from a previous systematic review by Johnston et al., were tailored to meet the specific needs of this review. [41] The extracted data included: (1) basic study characteristics, such as the first author, publication year, country, and sample size; (2) key characteristics of the study subjects; (3) research objectives; (4) research methods; (5) study conclusions; (6)research settings and (7) the roles and competencies of social workers as specified in the study content.

Table 4.

Data extraction

| Author(date)/ Country |

Sample | Study aim | Methodology | Setting | Qual ass |

Theoretical orientation | Role in palliative care | Competences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arnold, E. M., Artin, et al. (2006) USA [22] | Hospice social workers in 2 Southeastern states (N = 73) | To examine the experiences of hospice social workers in working with hospice patients who had unmet needs at the end of life | Questionnaire survey; Use standard descriptive statistical methods by SPSS to analzy | Hospital setting | 5 | Consult or support of the patient or family; Referral for outside services; Educate the patient and family; aggressive pain management; Continued assessment and intervention on family conflicts | Professional consulting skills; Cultural Sensitivity: leveraging societal attitudes for efficient palliative care | |

| 2 | Carmel,P. (2001) Israel [23] | Social workers in Israel. (N = 68, 52 participants (76.5%) worked at hospitals and 16 (23.5%) worked at nursing homes) | To examine the involvement, beliefs, and knowledge of social workers in health care settings in the process of making decisions regarding life-sustaining treatments | Questionnaire survey | hospital setting and nursing homes | 5 | Involve patients and their family members in decisions regarding life-sustaining treatments; Talking with the family regarding near-death prognosis; Obligations as surrogates of elderly persons | Knowledge and understanding of family structure, dynamics, and relationships; Knowledge about sensitive issues; Strong beliefs in the decision making process | |

| 3 | Csikai EL,Raymer M.(2005) USA [24] | Social workers from across the country working in a variety of health care settings(n = 381) | To examine educational preparation obtained in social work programs and continuing education | Questionnaire survey | nursing homes and private homes,community setting | 5 |

Support the decisions made and work with the family around anticipatory grief issues, completed the advance directive with the assistance of the hospital social worker;Get continuing education curriculum |

Knowledge which they can seek further training in the specific skills needed to fulfill their roles in their particular setting |

|

| 4 | Fantus S, Cole R, Hawkins L, et al.(2023) USA [25] | Employed in the health sector as a full-time or part-time social worker,and held a degree with an accredited uni versity, as either a Bachelor of Social Work or MSW(n = 42) | To explore frontline HSWs’ lived expe riences of MD during the pandemic | Semi-structured interviews | Hospital setting, nursing homes and prvate homes, Community setting | 5 | Face in moral distress(MD) in discharging and end-of life care;Interdisciplinary collaboration;Advocate social justice |

Enhancing team collaboration,responding to ethical concerns and formalising peer facilitation;Incorporate a social work lens into organisational practice |

|

| 5 | Guan T, Brintzenhofeszoc K, Middleton A,et al.(2024)USA [26] |

AOSW, the Association of Pediatric Oncology Social Work, and the Association of Community Cancer Centers,oncology social workers involved in palliative care in the 3 organizations'membership Listserv (n = 242) |

To delineate the current practice role of oncology social workers involvement in palliative care in the United States |

Cross-sectional study | Hospital setting, nursing homes and prvate homes, Community setting | 5 |

Therapeutic Interventions for Individuals, Couples, and Families; Facilitate Patient Care Decision-making; Care Coordination; Assessment and Emotional Support; Organization and Community Service; and Equity and Justice |

Assessing patient understanding of treatment options; Helping support health equity value in palliative care | |

| 6 | Guo MR, Guo JH, Liang K, et al.(2024) China [27] | Experts in the field of social work and palliative care at Fujian Medical University (n = 5) | To explore the core competencies expected of hospice social workers | In-depth interview; Literature research method | Hospital setting | 4 | Grounded theory | Intervene in psychological and psychiatric problems of themselves, patients and their families; provide better social support for patients and their families | Removing obstacles to traditional ethical concepts; Ability to educate about death; Build team coordination; Integrate resources; Mastery of healthcare-related knowledge |

| 7 | Head B, Peters B, Middleton A.et al.(2019)USA [42] | Social workers representing 43 states (N = 482) | To clearly describe the roles, skills and tasks of social workers | Cross-sectional survey | Hospital setting | 4 | Assess family dynamics, culture, cognition, mental health; Update care plans based on findings; Respect customs, support grief, assess risks and provide bereavement care | Assessment Skills; Teamwork and crisis management; Ethical decision-making; Personal Qualities of empathy, attention to detail, patience, supportiveness | |

| 8 | Jang SM, Lim JW, Choi JE.(2024) Korea [29] | Social workers who had worked in hospice institutions for over 5 years (N = 10) | To explore achievements and barriers in hospice social work practice and to suggest strategies | Reputational case sampling; Focus group interview; Thematic analysis | Hospital setting | 4 | Support patients and families in hospice adaptation; Facilitate communication; Develop tailored care programs; Offer social welfare information or resources; Identify overlooked aspects; Support medical team | Psychosocial assessment and intervention; Communication and coordination; Understanding community resources and welfare services; Respect for patient autonomy and dignity; Teamwork | |

| 9 | Jones B. L. (2006) USA [30] | Social workers in APOSW (N = 131) | To identify the social work perception of the psychosocial needs of dying children and adolescents and their families |

qualitative and quantitative; template analysis and principal components analysis |

Hospital setting | 4 | Assess the family and treatment situation; Supportive counseling and support for the emotions experienced by children and families facing the end of life | Assisting family members in understanding their emotions; Responding non-judgmentally to children and families; Maintaining openness and honesty; The skills to identify different needs in each family | |

| 10 | Kramer B. J. (2013) USA [31] | Report of a survey of the needs of deceased older adults by social workers (n = 120), focus groups with members of the interdisciplinary team (n = 5), older adults (n = 14) and family caregivers (n = 10) | To examine social workers roles in caring for low-income elders with advanced chronic disease in innovative, community-based care | Focus group; In-depth interview | Community setting | 3 | Address family's psychological responses; Coordinate community resources; Support caregivers and family; Aid in decision-making and end-of-life prep; Provide information, emotional support, and relieve family burden | Assessment and communication skills; Crisis intervention; Teamwork; Knowledge of grief, mourning and funeral planning; Cultural sensitivity; Understanding of legal and ethical requirements related to end-of-life care; empathy | |

| 11 | Lacey D. (2005) USA [32] | Nursing home socials from 2 facilities in New York State (n = 137) | To discuss nursing home social workers'response to using end-of-life skills | Questionnaire survey; Chi-Square Analyses and Factor Analysis | Nursing homes | 4 | Educate families and staff on advance directives; Plan care for dementia residents; Resolve family conflicts; Implement policies; Enhance social work professionalism; Provide grief counseling to families and staff | Expertise in advance directive decisions; Knowledge of geriatric palliative care and dementia views; Grief counseling; Active listening; Combined family education and care planning for conflict resolution | |

| 12 | Liu XY.(2014)China [33] | A child hospice care case in a hematology and oncology department in a hospital in Shanghai | To explore the needs of patients, the role of social workers, service strategies, intervention techniques and evaluation methods in child hospice care | Participatory observation, field notes | Hospital setting | 3 | Coordinate the services between the hospice care teams;Coordinate the differences between the doctors and the families of the child;Integrate social support resources;Emphason individualized hospice services | Discussion on the topic of Death and Life Review Death in Chinese values; Assessment,coordination and resourse allocation skills | |

| 13 | Lv QL, Cheng HL.(2018)China [34] | Six cases from the Surgery Department of Shanghai A Hospital, the long-term inpatients in this ward were mainly cancer patients(n = 6) | To explore the ethical dilemma of social workers'intervention | Participatory field observation; Unstructured interview | Hospital setting | 4 | Coordinator between patients and family members; the coordinator and the supporter in the doctor-patient relationship; Resource raisers | Face in thical dilemmas caused by the conflict of values | |

| 14 | Prieto-Lobato JM, De la Rosa-Gimeno P, Rodríguez-Sumaza C, et al.(2023) Spain [35] | professionals intervening in the social dimension of end-of-life care in INTecum project, (n = 234) | To examine the role of social workers involved in a pilot home care project | Questionnaire survey;In-depth interviews; Semi-structured interviews | Nursing homes and pravte homes, community setting | 4 | evidence-based, constructivist, and comprehensive evaluation |

Management of services and supports, the establishment of teamwork , and the recognition of the basic principles of the care process |

Assessment skills of the social needs of the person and their relatives;Technical and methodological knowledge,relational skills,and ethical attitudes |

| 15 | Sheldon FM.(2000)UK [36] |

Five experienced social workers: urban voluntary,urban NHS inpatient, rural voluntary,urban NHS community palliative care team and a seaside town voluntary(n = 5) |

To focuse on the role of the social worker in a specialist palliative care service |

In-depth qualitative interviews;Focus grop | Hospital setting, nursing homes and prvate homes, Community setting | 4 | Focusing on family relationships;Advice and information giving;Being a team member;Managing anxiety;Values and valuing;Knowing and working with limits |

Skills and knowledge of coordination,assessment,resource allocation; Values of being nonjudgemental,encouraging self-determination,confidentiality,and Challenging discrimination |

|

| 16 | Supiano KP, Berry PH.(2013)USA [37] | Students in the courses for six semesters.(n = 87) |

To evaluate elements contributing to competence and confidence in interdisciplinary practice skills of second year MSW students |

Participatory field observation;Focus group | Hospital setting | 4 | Phenomenological inquiry | Be the dynamics of interdisciplinary teams and collaboration;Pain and suffering;Symptom management; ethical,cultural,and spiritual issues;Grief and bereavement, and family dynamics | Increased knowledge in palliative care,enhanced attitudes in practice, and application of skills to their clinical practice settings |

| 17 | Waldron M, Kernohan WG, Hasson F.(2013)UK [38] |

social workers with a range of experience from both the NHS and the voluntary sectors (n = 13) |

To examine the social worker’s role in the delivery of palliative care to clients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) | Focus grop; In-depth interview | hospital setting and nursing homes | 4 |

Providing practical and psychological support, information,signposting to other services and caring for the clients and their families;gave support on practical, financial or legal issues to clients’ families, help to ease communication and reduce stresses |

Skills of communication, assessment and self-care; Knowledge of the definition of palliative care, referres and public awareness; Value of death and dying | |

| 18 | Washington KT, Albright DL, Parker Oliver D,et al.(2016)USA [39] |

Hospice and palliative social workers from 23 states and 1 foreign country(n = 78) |

To determine the frequency with which hospice and palliative social workers encounter risk of suicide and the preparation they have | Cross-sectional survey | Hospital setting, nursing homes and prvate homes, Community setting | 4 | Possessed sufficient knowledge and skills to intervene effectively with individuals at risk of suicide |

Suicide-related competencies in the practice of hospice and palliative social work |

|

| 19 | Xu LY, Weng ZC, Mo N.(2019) China [40] | A fourth year student of social work major in Fujian Provincial Hospital (N = 8) | Discusses the cultivation of the core competence of hospice care from four aspects: concept education, special training, whole-process supervision and quality expansion | Participatory observation; In-depth interview | Nursing homes | 3 | Demand assessment; assisting medical services, facilitating doctor-patient communication, and developing end-of-life strategies; Emotional regulation; Family empowerment | Ability to respond to medical and nursing knowledge; Analysis of and emergency handling capability of the terminal scenario; The ability to care for and empower the family as a whole; The ability to integrate resources and the social advocacy power |

Table 5.

Themes extracted from data analysis

| Ethics |

| 1. Maintaining non-judgmental stance in interactions with complex service receipts [24, 36] |

| 2. Advocating for person-centered care frameworks and autonomous decision-making rights [24, 27, 31, 34, 36] |

| 3. Deconstructing structural inequalities in palliative care delivery systems [25, 27, 34] |

| 4. Providing professional supports to colleagues facing workplace discrimination [26, 27] |

| 5. Operationalizing empathy principles and privacy protection [34, 36] |

| 6. Enhancing care quality through humanistic care practices [31] |

| 7. Institutional ethical decision-making prioritizing patients welfare [25, 31, 34, 40] |

| 8. Adaptive integration of religious/ethnic belief systems [24, 25, 31, 33] |

| 9. Negotiating ethical tensions between patient advocacy and professional moral distress [25, 34] |

| 10. Implementing abuse identification and reporting protocols [27, 28] |

| 11. Mastery of legal frameworks for patient rights protection [26, 27, 31] |

| Coordination |

| Interdisciplinary team coordinator |

| 12. Facilitating interprofessional collaboration across medical, nursing, social work, and allied health disciplines [25, 28, 33, 35, 38, 43] |

| 13. Supporting colleagues navigating end-of-life care complexities [31, 36, 38] |

| 14. Mitigating occupational anxiety among hospice professionals [27, 28, 31, 34, 36] |

| 15. Role clarification to enhance social work visibility in multidisciplinary team [25, 36, 43] |

| 16. Strategic advocacy for social work roles through interprofessional education and policy engagement [22, 27] |

| 17. Fostering role consciousness and mutual appreciation within care teams [25, 34, 37] |

| 18. Articulating social work's unique contributions to holistic care [25, 27, 28, 31, 34, 37, 43] |

| 19. Developing medical-literacy to support clinical staff in care provision [23, 25, 34, 37, 38, 40] |

| 20. Operationalizing division of labor protocols for responsive terminal care [27, 34, 40] |

| 21. Mediating interdisciplinary dialogues on informed consent protocols [27, 34] |

| 22. Implementing case management models for resource coordination [26, 26, 27, 33, 37, 43] |

| 23. Adapting team roles to pandemic-induced care paradigm shifts [25] |

| 24. Addressing moral distress from interprofessional disagreements [25, 34, 36] |

| 25. Navigating administrative constraints in visitation policies and remote assessments [25, 32, 43] |

| Fostering communication between patients(families) and healthcare professionals |

| 26. Translating patient anxiety narratives to medical teams [22, 31, 43] |

| 27. Bridging therapeutic communication gaps in treatment plan adherence [32, 33, 36, 43] |

| 28. Facilitating systemic access to palliative care services [24, 26, 28, 31, 32, 37, 43] |

| 29. Identifying unmet care needs through critical needs assessment [31, 34–36, 43] |

| 30. Contextualizing care through comprehensive psychosocial histories [28, 31, 34, 37] |

| 31. Facilitating acceptance of non-intervention approaches [22, 31, 32, 35] |

| Fostering communication between patients and their families |

| 32. Alleviating anticipatory grief in familial systems [22, 26, 31–33, 36] |

| 33. Co-constructing legacy projects and transitional plans [23, 26, 28, 31, 32, 35, 36] |

| 34. Facilitating familial narrative reconstruction and mutual understanding [22, 27, 28, 31, 36, 40] |

| 35. Enabling shared decision-making frameworks [23, 26, 28, 32, 37, 43] |

| 36. Delivering psychotherapeutic support to familial networks [22, 31–33] |

| 37. Cultivating adaptive hope within family systems [22, 23, 26] |

| 38. Facilitating life review processes and mortality dialogues [32, 33] |

| 39. Mediating familial conflict resolution through structured interventions [22, 27, 31, 32, 43] |

| 40. Providing supportive counseling and emotional support [22, 24, 26, 31, 32, 43] |

| 41. Developing pediatric palliative care plans with parental systems [22, 33] |

| Assessment and intervention |

| Patient Assessment |

| 42. Conducting biopsychosocial life-course assessments [24, 27, 28, 40] |

| 43. Employing active listening in clinical information synthesis [27, 40] |

| 44. Implementing multidimensional assessment protocols (physical, psychological, social, cognitive) [24, 27, 28, 40, 43] |

| 45. Conducting suicide risk stratification [39] |

| 46. Identifying systemic gaps in familial support structures [22, 28, 33, 35, 38, 38, 40, 43] |

| 47. Utilizing standardized assessment instruments [27, 33, 39, 40, 43] |

| Family Assessment |

| 48. Analyzing familial dynamics through systems theory lenses [24, 28, 33, 35, 43] |

| 49. Assessing socioeconomic determinants of family functioning [24, 28, 35, 40] |

| 50. Evaluating caregiver burden and social isolation [28, 33, 38] |

| Environmental Assessment |

| 51. Mapping community health ecologies [43] |

| 52. Evaluating informal support networks and financial resources [24, 33] |

| Ongoing Assessment |

| 53. Incorporating sociocultural and spiritual assessment dimensions [28] |

| 54. Implementing continuous and dynamic assessments [22, 28] |

| 55. Phased assessment models: intake to termination [33] |

| Resource allocation |

| Direct Services |

| 56. Implementing evidence-based clinical interventions [26, 28, 43] |

| 57. Crisis intervention in suicidality contexts [28, 40] |

| Social and Financial Support |

| 58. Navigating welfare benefit systems [22, 25, 26, 28, 31, 34, 35, 38, 43] |

| 59. Providing legal empowerment services [23, 26, 27, 34, 38] |

| 60. Educating on policy entitlements [25, 27, 31–33] |

| 61. Coordinating mental health service linkages [26, 43] |

| 62. Clarifying care system navigation protocols [26, 31, 35, 38, 43] |

| 63. Facilitating assistive technology access [26, 35] |

| 64. Coordinating housing insecurity interventions [31, 35, 43] |

| 65. Facilitating legacy documentation processes [28, 31] |

| 66. Navigating complex insurance architectures [22, 31, 34] |

| 67. Advocating for health literacy in medical decision-making [22, 23, 27, 31, 34, 38, 43] |

| 68. Mobilizing volunteer support networks [22, 33, 38, 40] |

| 69. Building community partnership models [28, 38, 43] |

| Referral Services |

| 70. Managing care transitions, discharge, and transfers [26–28, 38, 43] |

| 71. Sustaining community-based support ecosystems [28, 38, 43] |

| 72. Implementing localized resource referral systems [28] |

| 73. Coordinating respite care services [26, 31, 38] |

| 74. Integrating peer support paradigms [22, 25, 27, 31, 33, 40, 43] |

| 75. Facilitating end-of-life ritual planning [22, 31, 43] |

| 76. Transitioning hospital-to-home care model [26, 35] |

| 77. Addressing health resource disparities [22, 25, 26, 38, 43] |

| 78. Implementing holistic system interaction frameworks [33, 43] |

| 79. Ensuring health information equity [22, 31, 36, 38] |

| 80. Organizing therapeutic group modalities [34, 40] |

| 81. Implementing continuum-of-care interventions [22, 24, 26, 35, 43] |

| Family engagement |

| 82. Co-developing provisional support, life story, and care plans [35] |

| 83. Operationalizing patient preference actualization [23, 34, 40] |

| 84. Empowering families through resource brokerage [22, 27, 32, 40, 43] |

| 85. Mediating familial emotional discord [22, 31, 32, 34, 40] |

| 86. Implementing advance care planning dialogues [23, 24, 31] |

| 87. Aligning interventions with familial cultural capital [22, 31] |

| Education |

| Patient and Family Education |

| 88. Demystifying social work roles in care systems [28, 43] |

| 89. Implementing caregiver competency training [36, 40] |

| 90. Advancing palliative care literacy and ACP education [22, 27, 28, 32] |

| 91. Implementing thanatology education frameworks [22, 24, 27, 31, 33] |

| 92. Enhancing health literacy for informed decision-making [22, 28, 31–33, 36] |

| 93. Providing personalized grief counseling for family members [22, 27, 28, 31, 35, 38, 40, 43] |

| Educating Colleagues |

| 94. Advocating for social work integration in health systems [25, 26, 28, 43] |

| 95. Institutionalizing person-centered communication training [31, 34] |

| 96. Educating on palliative care biopsychosocial dimensions [22, 32] |

| Community Education and Advocacy |

| 97. Implementing community-based hospice awareness initiatives [26–28, 32, 40] |

| 98. Advocating for palliative care policy reform [22, 25, 28, 33, 34, 40] |

| Professional Supervision and Self-Care |

| 99. Implementing clinical supervision burnout prevention models [24, 25, 33, 34, 40, 43] |

| 100. Building professional resilience through specialized training [27, 33, 43] |

| 101. Ensuring workplace rights through equitable conflict resolution mechanisms [25, 27, 43] |

| Promoting the Development of Professionalism |

| 102. Optimizing social work curricula for clinical competencies [24, 27, 40, 43] |

| 103. Developing continuing education frameworks in palliative social work [22, 24, 25, 27, 32, 35, 39, 40] |

| 104. Contributing to evidence-based practice innovation [22, 28, 43] |

| 105. Facilitating lifelong learning through professional forums [24, 32] |

Data synthesis

Thematic analysis was selected for its flexibility in systematically identifying patterns across qualitative and quantitative studies. This method aligns with the review’s exploratory aim to synthesize heterogeneous data types, allowing inductive theme generation while maintaining methodological rigor23. To ensure rigor and reliability, two authors (Wang and Zhu), who underwent comprehensive training in qualitative analysis under the supervision of the first author, independently conducted the analysis. Data from the 19 selected articles were imported into NVivo software for systematic coding and categorization, focusing on the roles and competencies of social workers in palliative care. Through line-by-line coding, 105 initial sub-themes were identified, which were subsequently refined and synthesized into five overarching themes: ethics, coordination, assessment, resource allocation, and education. As a result, E-CARE framework emerged organically from the data rather than being imposed a priori. To enhance the validity of the findings, all authors engaged in iterative discussions to critically review and refine the themes, ensuring consistency and depth in the analytical process.

Findings

Study characteristic

A comprehensive literature search identified 3,429 articles. After screening titles and abstracts, 127 full-text articles were retrieved. A detailed review excluded 108 articles that didn't meet inclusion criteria, leaving 19 left. These studies, published from 2001–2024, came from the US (10), China (4), UK (2), Israel, Spain, Korea (1 each). According to MMAT criteria, 19 articles meet the quality standards. There were 9 qualitative, 9 quantitative descriptive, and 1 mixed-methods study.

Through thematic synthesis, five core competencies emerged, forming the E-CARE framework: Ethics, Coordination, Assessment, Resource Allocation, and Education. The E-CARE framework outlines five core competency standards for palliative social workers, which might serve as benchmarks for high-quality, patient-centered care. These standards reflect the ideal integration of knowledge, skills, and values, acknowledging that actual practice may vary across contexts.

Ethics

In palliative care, social workers operationalize an integrated ethical-operational framework, balancing patient autonomy, cultural humility, and systemic advocacy. They operationalize these principles by prioritizing patients'best interests over institutional demands [29, 31], advocating for marginalized populations through structural barrier deconstruction [24–27, 34–36], and maintaining non-judgmental therapeutic alliances to uphold patient autonomy [24–27, 34–36], Their practice integrates cultural, spiritual, and ethnic belief systems into care plans through adaptive navigation of belief systems [24, 25, 31], while systematically implementing empathy principles and privacy protection mechanisms to foster trust [34, 36]. Ethically, they construct welfare-prioritizing decision frameworks [25, 28, 31, 34] that balance advocacy efforts with moral distress mitigation [24–26, 31, 34], resolving dilemmas through abuse identification protocols [27, 40] and legal safeguard mastery [26, 27, 31, 40]. Concurrently, they enhance service quality via intentional humanistic practices and collegial support systems addressing workplace discrimination [26, 27, 31]. This value paradigm is sustained through self-care strategies preventing professional burnout while enabling rights preservation across healthcare hierarchies [24, 25, 29, 31]. Collectively, these interconnected competencies—spanning justice-oriented advocacy [24, 27, 31, 34, 36], cultural mediation [24, 25, 31, 34], and dual protective systems [26, 27, 31, 40] —position social workers as catalysts for systemic change and dignity-preserving care in palliative ecosystems.

Coordination

Interdisciplinary team coordinator

Social workers demonstrate essential interdisciplinary competencies that are crucial for optimizing team functioning in palliative care settings. Their specialized skill set enables them to facilitate effective interprofessional collaboration while making distinctive contributions to team dynamics [25, 28, 29, 31, 34]. Specifically, they exhibit advanced competencies in emotional regulation, conflict mediation, and moral distress management, which they utilize to support both team cohesion and individual well-being among hospice professionals [24, 25, 34, 36]. A key competency lies in their ability to maintain team stability through enhanced communication protocols and information-sharing systems. Their professional sensitivity enables them to identify and address psychological pain that might otherwise be overlooked due to disciplinary differences in perception and approach. Furthermore, they demonstrate strategic competencies in clarifying role differentiation and optimizing operational workflows, thereby preventing inefficiencies in service delivery. Through the effective application of these competencies, social workers synergize diverse professional strengths, transforming multidisciplinary groups into cohesive, high-functioning care teams [25, 31]. Their unique skill set in team coordination and system optimization ultimately enhances the quality of palliative care delivery while supporting both patients and fellow healthcare professionals.

Communication facilitator between patients(families) and healthcare professionals

Social workers possess specialized competencies in mediation and information synthesis, which enable them to effectively bridge communication gaps between patients, families, and multidisciplinary healthcare teams. They apply advanced communication skills to cultivate an environment conducive to open-ended dialogue, which is essential for understanding the unique needs and preferences of patients and their families. Through their expertise in data integration, social workers systematically collect and synthesize information from diverse sources, including medical records, psychosocial assessments, and family histories. By leveraging these analytical and integrative skills, they provide the healthcare team with comprehensive and accurate data, empowering informed clinical decision-making and the development of personalized care plans [24, 27, 31, 38].Additionally, social workers demonstrate exceptional competencies in knowledge dissemination and team coordination [23, 27–29, 31, 32]. ensuring the seamless flow of critical information among all stakeholders. This coordination skill set not only maintains team alignment but also enhances the delivery of optimized, patient-centered care.

Communication facilitator between patients and their families

During periods of uncertainty and distress, social workers intervene to assist patients and their families in grappling with complex decisions. They offer emotional counseling and psychological support during family meetings, creating opportunities for family members to progress and reach consensus in decision-making [22, 23, 29, 31–33, 38]. Confronted with the reality of death, social workers collaborate with families to help patients reflect on their lives, plan for the remaining time with the dying individual, and kindle realistic hope. As facilitators of communication between patients and their families, social workers mobilize and integrate essential resources to ensure the best-possible services for patients [22, 23, 25, 26, 32].

Assessment

Patient assessment

The competencies to assess the needs of patients and their families is characterized by multi-dimensionality, real-time adaptability, dynamism, and methodological diversity. Social workers evaluate multiple dimensions of a patient's life, with a focus on aspects such as safety, illness perception, decision-making capacity, quality of life, psychosocial well-being, and social support networks. They gather insights through various means, including basic information collection, assessment of problem severity, quality-of-life evaluation, analysis of support networks, pain scale measurement, and assessment of suicidal intentions [23, 26, 28, 35, 40]. This process involves understanding the patient's primary current needs and expectations, coping mechanisms, understanding of illness perceptions, and healthcare planning [24, 26, 28, 29, 31, 40]. It is worth noting that the focus of social workers'assessments varies depending on the disease and age group [34]. For instance, during the treatment of Parkinson's disease, social workers concentrate on assessing mobility and drug-induced hallucinations [23, 35, 38].

Family assessment

Drawing on family system theory, social workers acknowledge the interdependence among family members and the significant impact of a member's terminal illness on the entire family system. They assess family's knowledge and skills of caregiving, communication patterns, and coping strategies, and then provide psychosocial support and interventions [28, 29, 31, 33, 35]. In contrast to patient assessment, family assessment primarily focuses on the measurement of psychological distress in family members, particularly helplessness and anticipatory grief, rather than physical symptomatology. This involves identifying obstacles to effective palliative care, such as family dysfunction,"conspiracies of silence", and the reluctance to express needs. Social workers advocate for the family's needs, offer psychological support, facilitate communication about physical and mental states, and encourage the expression of needs [22, 28, 33, 38].

Environmental assessment

Social workers evaluate the social support factors within the patient's community, which include social relationships, financial status, and living conditions. They provide material support and resources, such as volunteer services and funeral arrangements, to promote patient-centered goals and care planning [23, 33, 34, 40]. They also assess socioeconomic status, the safety of the living environment, the presence of abuse and neglect, and geographic barriers to identify the patient's support systems [25, 28].The assessment of the macro social environment is an advanced requirement, a minority of social workers routinely explored prevalent psychosocial issues, which serves as preparation for family meeting.

Ongoing assessment

Continuous assessment is of utmost importance for social workers. It enables them to address emotional issues, understand patient values, and judge needs based on physical appearance, voice, and family dynamics [29, 33, 40]. For example, social workers monitor and prevent suicidal behaviors, such as a patient's previous suicide attempts, thoughts about death, saying goodbye to family members, preparing wills, and storing medications. The temporal dimension of social workers'assessment competencies is demonstrated through their sustained engagement with bereaved families, employing a multimodal approach that includes systematic telephonic follow-ups, personalized written communications, structured group support sessions, and individualized counseling interventions to monitor and support high-risk families during the post-bereavement period.

Resource allocation

Direct services

Social workers demonstrate a comprehensive range of clinical competencies that span both general medical social work and specialized psychiatric interventions. They exhibit advanced skills in implementing evidence-based therapeutic approaches, including crisis intervention, problem-solving therapy, family systems interventions, and cognitive-behavioral techniques [26, 28, 29, 36]. Their clinical expertise extends to specific counseling modalities such as life review therapy, relaxation training, active listening techniques, guided imagery, and brief therapeutic interventions. In high-risk situations, particularly in suicide prevention, social workers apply specialized competencies in rapid assessment and crisis management. They employ innovative therapeutic methods, such as narrative-based interventions, to address complex psychological challenges like death anxiety [28, 33, 35]. These competencies enable them to effectively ensure client safety while promoting psychological well-being through tailored, client-centered approaches.

Social and financial support

In palliative care, social workers streamline access service ways to legal aid, in-home care services, financial and benefits assistance programs and the procurement of medical supplies and equipment, such as such as SSDI/SSI, FMLA, food banks, etc [23, 25, 26, 28, 29, 31, 32, 34, 38]. Navigating through complex insurance, entitlement, and financial programs can be a daunting task for patients and their families. Therefore, social workers assist patients in comprehending and accessing these programs to ensure that they receive the necessary support, such as finding a list of all funeral homes for patients, copying the health proxy to respond to patients'questions, etc [22, 31, 34]. Moreover, they connect patients with care programs, elucidate the associated rules [26, 29, 31, 35, 38], while also offering information, control, and advocacy regarding medical decisions, thereby enabling patients and their families to make well-informed choices [23, 27, 29, 31, 34, 38]. Additionally, social workers collaborate with agencies and communities, and contribute to public assistance programs to offer continuous support and resources. This ensures that patients can maintain their dignity at the end of life and that families can access continued services after the patient's passing [22, 26, 29, 33, 36, 38].

Referral services

Referral services play a crucial and fundamental role in palliative social work, particularly when the existing medical services and support systems fall short of meeting the ever-changing needs of patients in palliative care. Social workers are responsible for implementing systematic interventions that span the entire continuum of care, from the pre-death stage to the post-bereavement period [24, 26, 29, 35]. They act as a vital link to a diverse array of specialized services. This includes providing respite care for overburdened caregivers [26, 31, 33] and arranging funeral services [29, 31, 33]. Moreover, social workers offer assistance during transfers, discharges, and other care transitions. For instance, they employ specialized interventions to mitigate the anxiety and fear experienced by patients and caregivers facing potential discharge after exceeding 60-day care periods [26–29, 38, 43]. Whether it’s facilitating the transition of patients to nursing homes, referring them to community hospitals, or arranging in-home care, social workers are actively involved in providing resources for advance directive work and end-stage care planning [26–29, 38].

However, the scarcity of economic resources and community welfare services often restricts the available referral options [22, 25, 26, 29, 34]. In response, social workers adopt a comprehensive approach. They focus on how patients interact with and adapt to the surrounding systems [29, 33]. To enhance the support available to patients, they integrate peer support, volunteer services, and other social resources [22, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33]. Additionally, they recommend suitable local resources and institutions to patients [28]. In the process, social workers also maintain communication with medical institutions to obtain comprehensive medical information [31, 33, 36]. At the same time, they connect various social resources to establish and facilitate support groups for both patients and caregivers [28, 34]. This multi-faceted approach ensures that patients in palliative care receive the most appropriate and comprehensive support throughout their journey.

Family engagement

Social workers demonstrate specialized competencies in family-centered palliative care, facilitating emotional connections and mutual understanding between patients and families during challenging circumstances [22, 25, 27, 29, 34, 40]. Their expertise encompasses implementing home-based care strategies, facilitating advance care planning discussions, and developing individualized care plans through family collaboration [23, 24, 31, 35] while applying specialized mediation skills in structured family meetings to help members comprehend and respect patients'preferences [22, 32, 34, 35]. Drawing on psychotherapeutic training and family systems theory, they provide comprehensive grief support, addressing complex emotions and preparing families for role transitions [22, 23, 25, 28, 29, 31, 33, 35], while maintaining professional neutrality to mediate conflicts and establish effective communication patterns [22, 28, 31, 34, 40]. These multifaceted competencies enhance end-of-life support systems and establish foundations for healthy bereavement processes.

Education

Patient and family education

Through effective communication, social workers tend to facilitate patients and families to understand knowledge about care protocols, medical prognoses, and hospice philosophy, enabling patients and families to make informed decisions and feel empowered through tailored education in end-of-life care [26, 40]. During initial engagement, they clarify their professional scope to establish therapeutic alliances, subsequently guiding patients and families through medical condition comprehension and care decision-making processes [28, 29]. This includes structured discussions on treatment pathways, advance directives, and quality-of-life optimization strategies [21, 22, 28, 29, 32, 33, 38, 39]. Central to social workers'educational mandate is elucidating palliative care's multidimensional framework, emphasizing symptom control, psychosocial support, and dignity preservation. In terminal phases, they implement thanatological interventions addressing mortality perceptions, existential distress, and legacy reconciliation through psychoeducational techniques like life review and death anxiety mitigation [25, 28, 30, 32]. This dual-focused pedagogy enhances adaptive coping while fostering meaning-centered perspectives on mortality [22, 24, 27, 31, 33].

Education for colleagues

Despite their pivotal role in advancing patient-centered care within multidisciplinary teams, social workers frequently encounter professional undervaluation, underscoring the critical need for role clarification and interprofessional education [25, 26, 28, 29]. As champions of compassionate, humanistic care paradigms, they operationalize patient autonomy through systematic advocacy and the cultivation of nonjudgmental team dynamics. Their educational interventions focus on enhancing core competencies in therapeutic communication, active listening, and empathy development among healthcare providers [31, 34]. Furthermore, they deliver specialized training in thanatology, encompassing pain management protocols, advance care planning, hospice principles, and grief support mechanisms, thereby ensuring comprehensive, empathetic care delivery across the dying process [22, 32]. This focus on skill development and philosophical alignment strengthens interdisciplinary collaboration while maintaining fidelity to patient-centered care principles. However, social workers have to engage in role clarification and interprofessional education to prevent the undervaluation of their expertise and to foster team recognition [25, 26, 28, 29].

Community education and advocacy

Social workers serve as key change agents in advancing societal awareness and policy development in end-of-life care. Through strategic knowledge dissemination across multiple platforms, including mass media, community outreach programs, and academic symposia, which facilitate critical discourse on hospice principles, mortality awareness, and aging-related challenges, while reducing barriers to professional service utilization [26–28, 32, 40]. Their advocacy extends to active engagement in policy formulation, interdisciplinary research collaborations, and resource mobilization initiatives, which collectively enhance public literacy and promote systemic improvements in palliative care delivery [22, 25, 28, 33, 34, 40]. This multidimensional approach not only destigmatizes end-of-life discussions but also ensures sustained investment and innovation in the field.

Competency in self-care training

In palliative care practice, social workers must implement robust safeguards against professional burnout and competency gaps. Professionally, this necessitates regular clinical supervision to address ethical complexities and practice dilemmas, ensuring adherence to evidence-based interventions and ethical frameworks [24, 25, 29, 33, 34, 40]. Concurrently, targeted training in spiritual care competencies and self-care strategies is crucial to mitigate the cumulative impacts of emotional labor and occupational stress [27, 29, 33]. Furthermore, the development of conflict resolution skills enables practitioners to effectively advocate for their professional rights while maintaining therapeutic boundaries and personal well-being. These multilayered protective mechanisms collectively sustain both service quality and practitioner resilience in this demanding specialty.

Promoting the development of professionalism

The advancement of professionalism in social work is crucial to ensuring high-quality services and addressing the evolving needs of individuals and communities. Social workers not only organize educational workshops and seminars, but also participate in research to advance program development and innovation, all aimed at improving palliative social work practice [24, 28–30, 32, 37, 43]. In turn, the practices of social workers in palliative care refine the social work curriculum, equip students with the theoretical knowledge and practical skills necessary for effective practice [27, 29, 35, 40]. What's more, it can also underpin to the development of specialized frameworks for continuing education in social work, while contribute to research for program development and innovation [22, 25, 27–30, 32, 35, 37, 39, 40].

Discussion

The E-CARE framework, emerging from a systematic synthesis of 19 high-quality studies, offers a comprehensive set of competency standards for palliative social workers. While these standards reflect an ideal integration of knowledge, skills, and values, it is important to recognize that actual practice may vary widely due to differences in resources, training, and cultural contexts. The E-CARE framework intends to guide professional development and systemic improvements, rather than to assume uniformity in current practice. For instance, environmental assessment techniques (e.g., mapping socioeconomic barriers) and thanatological interventions (e.g., death anxiety mitigation) translate cultural sensitivity into actionable protocols, overcoming the operational limitations of prior models [29, 44]. Notably, the inclusion of Resource Allocation as an independent dimension advances beyond U.S., European and Korean palliative care frameworks by redefining resource navigation as ethical decision-making—balancing systemic constraints (e.g., limited community welfare) with patient autonomy in care planning [45, 46]. This structural innovation responds to persistent challenges identified in majority of reviewed studies, particularly financial inequities and post-pandemic service fragmentation [25, 47]. Concurrently, the framework embeds “Ongoing Assessment” as a critical ethical safeguard, ensuring resource allocation decisions remain anchored in real-time biopsychosocial evaluations rather than reactive triage. This approach directly addresses documented risks of inequitable service distribution in resource-constrained environments.

E-CARE framework substantiates social workers' professional identity as “system navigators” and “existential educators” within palliative care ecosystems. Empirical studies consistently affirm their catalytic role in fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, particularly through conflict mediation and team cohesion strategies [48–50]. However, entrenched systemic barriers—manifested in professional marginalization across healthcare hierarchies—persistently undermine role recognition, as evidenced by cross-national practice analyses [42]. To countervail these structural constraints, the “ Education” dimension proposes transformative levers: equipping healthcare teams with patient-centered communication competencies and mobilizing community-level death literacy initiatives [51]. These strategies collectively facilitate paradigm shifts toward inclusive care models by implementing community epistemic empowerment via death literacy programs that reconfigure societal health narratives from curative dominance to dignity-preserving closure.

Practical implications and future directions

By providing a structured approach for social workers to navigate complex care ecosystems, E-CARE framework aims to fostering team cohesion, mediating conflicts, and ensuring seamless communication among healthcare professionals, thereby strengthening the delivery of patient- and family-centered care. The inclusion of Resource Allocation as an independent dimension equips social workers with tools to navigate systemic constraints, such as financial inequities and limited community welfare services, while advocating for family empowerment. Additionally, by emphasizing patient, family, and community education, social workers can destigmatize end-of-life discussions, enhance death literacy, and promote informed decision-making. The framework also underscores the need for ongoing training in thanatology, self-care, and ethical decision-making, ensuring social workers remain resilient and effective in high-stress environments. These implications are particularly relevant in resource-constrained settings, where social workers often face systemic barriers to delivering equitable care [25, 52].

To further refine and operationalize the competency framework, future research and practice should focus on several key areas. First, longitudinal studies should be conducted to empirically validate the framework's effectiveness in diverse palliative care settings, particularly in low-resource environments. Second, evidence-based policy recommendations should be developed to address systemic barriers, such as financial inequities and professional marginalization, that hinder the role of social workers in palliative care. Third, the integration of digital tools, such as telehealth platforms and decision-support systems, should be explored to enhance resource allocation, patient education, and interdisciplinary collaboration. Fourth, the framework should be adapted to different cultural and healthcare contexts to ensure its relevance and applicability across diverse populations. For example, the balance between patient autonomy and family involvement in decision-making may differ significantly across cultures, particularly in collectivist versus individualist societies. Finally, interprofessional training programs should be expanded to include healthcare professionals from other disciplines, fostering a shared understanding of social workers'roles and competencies in palliative care. By addressing these areas, the framework can evolve into a globally recognized standard for palliative social work practice, ultimately improving the quality of care for patients and their families at the end of life.

Limitation

While the proposed five-dimensional competency framework offers a structured approach to palliative social work, this study carries several limitations. First, the literature search was constrained by the specific keywords used, which may have inadvertently excluded studies addressing critical areas such as continuous professional education and the provision or receipt of quality supervision. Second, the review was restricted to studies published in English and Chinese, which may have overlooked valuable insights from other cultural and linguistic contexts. This exclusion of diverse cultural perspectives could affect the framework's applicability to non-English and non-Chinese speaking populations, particularly in regions where palliative care practices and societal attitudes toward end-of-life care differ significantly. However, these constraints underscore the importance of future research to expand the scope of literature searches, incorporate a broader range of cultural perspectives, and address gaps in professional development and supervision. By doing so, the framework can be further refined to enhance its global applicability and ensure its effectiveness in diverse palliative care settings.

Conclusion

This study synthesizes the core competencies of palliative social workers into a five-dimensional framework: Ethics, Coordination, Assessment, Resource Allocation, and Education, emphasizing their pivotal roles as system navigators, interdisciplinary facilitators, and existential educators. Social workers drive interprofessional collaboration, conduct holistic assessments of patients' and families' needs, navigate systemic resource constraints, and promote informed decision-making to deliver person-centered care. Their expertise in addressing psychosocial, emotional, and practical challenges enhances the quality of life during end-of-life care. The framework's focus on ongoing assessment and equitable resource allocation tackles systemic inequities, particularly in resource-limited settings, while its educational advocacy dimension aims to destigmatize end-of-life discussions and improve death literacy. The framework offers actionable strategies for practice, calling for empirical validation, cultural adaptation, and systemic reforms to meet global palliative care demands.

Authors’ contributions

In terms of contribution, the first author of conceptualizing and carrying out current study, including allocating resources, supporting data analysis, interpreting findings and composing the original draft. The second and third authors was contributing to data analysis and the rest of authors reviewed the manuscript and provided valuable comments on refinement.

Funding

This study is funded by National Social Science Fund (CZ23054).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

None.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hong Yao, Email: lollipops_rain@126.com.

Yang Hui, Email: yanghuimuc@163.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Palliative care. Geneva, Switzerland; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care [Last accessed: 02/26/2025].

- 2.Tan MP. Healthcare for older people in lower and middle income countries. Age Ageing 2022;51(4):afac016; 10.1093/ageing/afac016 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bizuayehu HM, Ahmed KY, Kibret GD, et al. Global Disparities of Cancer and Its Projected Burden in 2050. JAMA Netw Open 2024;7(11):e2443198. Published 2024 Nov 4; 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.43198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Etkind SN, Bone AE, Gomes B, et al. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):102. 10.1186/s12916-017-0860-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taels B, Hermans K, Van Audenhove C, et al. How can social workers be meaningfully involved in palliative care? A scoping review on the prerequisites and how they can be realised in practice [published correction appears in Palliat Care Soc Pract 2021 Dec 16;15:26323524211067890; 10.1177/26323524211067890.]. Palliat Care Soc Pract 2021;15:26323524211058895. Published 2021 Nov 30; 10.1177/26323524211058895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Patterson GT, Swan PG. Police social work and social service collaboration strategies one hundred years after Vollmer: A systematic review. Policing: An International Journal 2019; 42(5):863–886; 10.1108/PIJPSM-06-2019-0097

- 7.Fischer S, Meisinger C, Linseisen J, et al. Depression and anxiety up to two years after acute pulmonary embolism: Prevalence and predictors. Thromb Res. 2023;222:68–74. 10.1016/j.thromres.2022.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alshehri HH, Wolf A, Öhlén J, et al. Healthcare professionals’ perspective on palliative care in intensive care settings: An interpretive descriptive study. Global Qualitative Nursing Research. 2022;9(2):233339362211380. 10.1177/23333936221138077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glajchen M, Berkman C, Otis-Green S, et al. Defining Core Competencies for Generalist-Level Palliative Social Work. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(6):886–92. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Donnell A, Gonyea J, Wensley T, et al. High-quality patient-centered palliative care: interprofessional team members’ perceptions of social workers’ roles and contribution. J Interprof Care. 2024;38(1):1–9. 10.1080/13561820.2023.2238783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macanović N, Petrović J, Dragojević A. Professional competence of experts in psychosocial work. International Review. 2022;3–4(3–4):47–54. 10.5937/intrev2204049M. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez N, Dory V, Ste-Marie LG, et al. Varying conceptions of competence: an analysis of how health sciences educators define competence. Med Educ. 2012;46(4):357–65. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Germain CB. Social work identity, competence, and autonomy: the ecological perspective. Soc Work Health Care. 1980;6(1):1–10. 10.1300/j010v06n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638–45. 10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gwyther LP, Altilio T, Blacker S, et al. Social work competencies in palliative and end-of-life care. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2005;1(1):87–120. 10.1300/J457v01n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang J, Kim Y, Yoo YS, et al. Developing competencies for multidisciplinary hospice and palliative care professionals in Korea. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013;21(10):2707–17. 10.1007/s00520-013-1850-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes S, Firth P, Oliviere D. Core competencies for palliative care social work in Europe: An EAPC White Paper, Part 1. Eur J Palliat Care. 2015;22:300–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monette EM. Cultural Considerations in Palliative Care Provision: A Scoping Review of Canadian Literature. Palliative Medicine Reports. 2021;2(1):146–56. 10.1089/pmr.2020.0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latimer A, Fantus S, Pachner TM, et al. Palliative and hospice social workers’ moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliat Support Care. 2023;21(4):628–33. 10.1017/S1478951522001341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roulston A, Ross J, Dobrikova P, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on palliative care social work: An online survey by a European Association of Palliative Care Task Force. Palliat Med. 2023;37(6):884–92. 10.1177/02692163231167938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaw RL. Identifying and synthesizing qualitative literature. In:Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: A guide for students and practitioners, ( David Harper, Andrew R Thompson,eds.)Wiley-Blackwel:USA;2011; pp. 09–22.

- 22.Arnold, E. M., Artin, et al. Unmet needs at the end of life: Perceptions of hospice social workers. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2006;2(4):61–83; 10.1300/j457v02n04 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Carmel, P.W., Sara. Israel End-of-life decision making: Practices, beliefs and knowledge of social workers in health care settings. educational Gerontology 2001;27(5) pp.:387–398; 10.1080/03601270152053410.

- 24.Csikai EL, Raymer M. Social Workers’ Educational Needs in End-of-Life Care. Soc Work Health Care. 2005;41(1):53–72. 10.1300/J010v41n01_04. (PMID: 16048856). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fantus S, Cole R, Hawkins L, et al. “Have they talked about us at all?” The moral distress of healthcare social workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative investigation in the state of Texas. The British Journal of Social Work. 2023;53(1):425–47. 10.1093/bjsw/bcac206. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guan T, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Middleton A, et al. Oncology social workers’ involvement in palliative care: Secondary data analysis from nationwide oncology social workers survey. Palliat Support Care. 2024;24:1–7. 10.1017/S1478951524000622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo MR, Guo JH, Liang K, et al. Study on the professional ability of social workers in hospice care based on rooted theory. Chin J Soc Med. 2024;41(01):118–22. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Head B, Peters B, Middleton A, et al. Results of a nationwide hospice and palliative care social work job analysis. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2019;15(1):16–33. 10.1080/15524256.2019.1577326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jang SM, Lim JW, Choi JE. Achievements and Barriers in Hospice and Palliative Social Work Practice: A Qualitative Study. J Hosp Palliat Care. 2024;27(4):131–48. 10.14475/jhpc.2024.27.4.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones BL. Companionship, Control, and Compassion: A Social Work Perspective on the Needs of Children with Cancer and their Families at the End of Life. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(3):774–88. 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kramer BJ. Social workers’ roles in addressing the complex end-of-life care needs of elders with advanced chronic disease. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2013;9(4):308–30. 10.1080/15524256.2013.846887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lacey D. Nursing home social worker skills and end-of-life planning. Soc Work Health Care. 2005;40(4):19–40. 10.1300/J010v40n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu XY. The practice of medical social work in the field of child hospice care —— Take the hospice care of a child with blood disease as an example. J Soc Work. 2014;05:39–48+153. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lv QL, Cheng HL. Research on ethical dilemmas and countermeasures in medical social work practice —— Take cancer patients as an example. Social Work and Management. 2018;18(03):36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prieto-Lobato JM, De la Rosa-Gimeno P, Rodríguez-Sumaza C, et al. Social work at the end of life: Humanization of the process. Journal of Social Work 2023;24(1); 10.1177/14680173231206713

- 36.Sheldon FM. Dimensions of the role of the social worker in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2000;14(6):491–8. 10.1191/026921600701536417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Supiano KP, Berry PH. Developing Interdisciplinary Skills and Professional Confidence in Palliative Care Social Work Students. J Soc Work Educ. 2013;49(3):387–96. 10.1080/10437797.2013.796851. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waldron M, Kernohan WG, Hasson F. What do social workers think about the palliative care needs of people with Parkinson’s disease? Br J Soc Work. 2013;43:81–98. 10.1093/BJSW/BCR157. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Washington KT, Albright DL, Parker Oliver D, et al. Hospice and palliative social workers’ experiences with clients at risk of suicide. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14(6):664–71. 10.1017/S1478951516000171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu LY, Weng ZC, Mo N. On the cultivation of the core competencies of hospice care and social work —— based on the reflection of practice and supervision. Chinese Medical Ethics. 2019;32(09):1183–7. [Google Scholar]