Abstract

Giant cell-rich osteosarcoma (GCRO) is a rare variant of osteosarcoma with unusual radiological and histopathological features that make its diagnosis challenging. The most critical and unusual feature of GCRO is that it has a purely osteolytic appearance. Therefore, GCRO cases are frequently subject to delayed diagnosis or incorrect treatment owing to misdiagnosis. This negatively affects the prognosis of these patients. In this study, 3 young adult cases are presented. The first case describes a young female patient who underwent repeated curettages due to a misdiagnosis of a giant-cell bone tumor, and the second case describes a delay in diagnosis in a young male patient who was misdiagnosed with an aneurysmal bone cyst. The final case report describes a young woman who was diagnosed early, treated promptly, and had a good prognosis. One of the poor prognosis cases in this report was treated with amputation, and the other was alive with multiple metastases. Misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis leads to a poor prognosis in such cases. To make a diagnosis, it is necessary to have knowledge and to be suspicious of the radiological features of this rare variant. Giant cell-rich osteosarcoma should be among the differential diagnosis options when dealing with pure metaphysiodiaphyseal osteolytic bone lesions in young adults. To avoid misdiagnosis or delay, it is necessary to have knowledge and to be suspicious of this rare variant.

Level of Evidence: Level IV, Therapeutic study.

Keywords: Osteolytic lesions, Osteosarcoma, Giant-cell bone tumor, Diagnosis, Prognosis

Highlights

Presence of purely osteolytic lesions in osteosarcoma, which is classified as a primary malignant osteoblastic tumor, is very unusual.

Adult patients presenting with osteolytic lesions, giant cell tumor of bone, Brown tumor, plasma cell disorders, and bone metastases should be considered in the preliminary diagnosis.

Giant cell-rich osteosarcoma (GCRO), a rare osteosarcoma variant, presents a difficult diagnostic challenge because of its confusing histological and radiological features, and clinicians should have a high level of suspicion for GCRO in young adults presenting with osteolytic lesions.

Misdiagnosis can lead to delay in treatment, which contributes to poor outcomes, emphasizing the critical need for an accurate diagnosis.

Introduction

Osteolytic bone lesions can be seen in bone metastasis, plasma cell disorders, hormonal imbalances as in Brown tumor, or in benign bone tumors such as giant cell tumor of bone (GCTB).1 Purely osteolytic appearance of a bone lesion in osteosarcoma, which is classified as a primary malignant osteoblastic tumor, is an unusual situation.2 The osteosarcoma is a high-grade malignant tumor composed of mesenchymal cells producing osteoid and immature bone.3 These tumors are bone sarcomas that rapidly metastasize to the lungs and have a high mortality rate. Without the use of chemotherapy, 80%-90% of osteosarcoma patients die of metastases, notwithstanding ablation of the primary tumor.4 The clinical and radiological features of conventional osteosarcoma, the most common type, are well known to clinicians, and its diagnosis and treatment have become almost standard. Giant cell-rich osteosarcoma (GCRO), a rare osteosarcoma variant, presents a difficult diagnostic challenge because of its confusing histological and radiological features, especially the abundance of multinuclear giant cells and the formation of pure osteolytic bone lesions.5

Due to unexpected histological and radiological features in osteosarcoma, GCRO cases usually experience a diagnostic delay, causing increased morbidity and mortality rates.6-8 Misdiagnosis leads to the spread of the disease by treating patients with inappropriate treatment methods such as intralesional curettage, while diagnostic delays contribute to disease progression and lung metastases. In this article, our aim is to highlight the diagnostic challenges associated with GCRO, which are mostly characterized by purely osteolytic lesions, by describing 3 cases who were initially evaluated for other diseases and had a delayed diagnosis of GCRO.

Case presentation

Case 1

A 21-year-old female patient presented with swelling and pain in the right proximal leg. The patient had a history of previous surgical treatment for the lesion in an elsewhere center 4 times in the last 5 years. The initial diagnosis was GCTB in the proximal diaphysis of the right tibia. Before applying to our center, the patient had undergone several surgical interventions due to local recurrences shortly after intralesional curettages. The patient applied due to the presence of neoplastic infiltration in the pathology report regarding her last surgery.

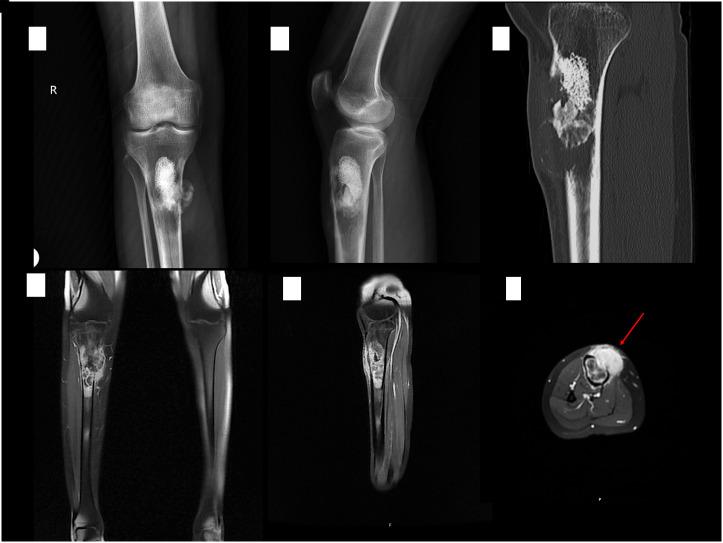

Physical examination revealed a 5 × 5 cm palpable, firm, immobile, and painful mass on the anterior of the right proximal tibia, and a 10 cm previous incision scar overlapping the mass. Plain radiographs, computed tomography (CT) scans, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) views at the admission are seen in Figure 1. A core-needle biopsy was planned by the Institutional Tumor Board. The biopsy revealed a chondroblastic type, conventional osteosarcoma rich in giant cells. The patient underwent proximal tibial wide resection and prosthetic reconstruction following neoadjuvant chemotherapy admission. The histopathological evaluation of the resected specimen revealed a GCRO. The patient was transferred to the oncology clinic for adjuvant chemotherapy.

Figure 1.

Radiographs (A and B), sagittal CT scan (C), and T1 weighted FatSat MR images with contrast enhancement (D-F) at the presentation. An osteolytic-cystic bone lesion with cortical destruction at the right proximal tibia containing granular opacities compatible with bone cement secondary to previous surgery. Arrow indicates intramedullary tumor with strong contrast uptake, extending through cortical destruction area to the paraosseous structures and subcutaneous plane.

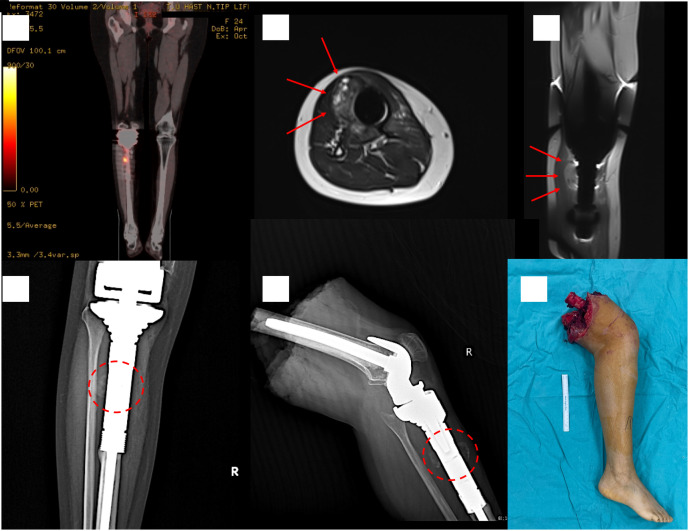

Three years after the resection, the patient reported recurrent swelling and pain at the surgery site. Increased FDG uptake on positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET–CT) evaluation in the soft tissue with calcific content suggested malignancy recurrence (Figure 2). The biopsy of the recurrent lesion indicated a high-grade osteosarcoma. After staging, the patient received 3 courses of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by an above-knee amputation. The final histopathological evaluation revealed the diagnosis of high-grade osteosarcoma.

Figure 2.

Local recurrence 3 years after proximal tibia resection. Coronal PET–CT scan showing increased FDG uptake in close relation with the prosthesis (A). Arrows indicating the tumor surrounding the prosthesis in MRI scans (B and C). Dashed circles showing irregular calcific soft tissue lesions around the prosthesis in specimen radiographs (D and E). The patient was treated with an above-knee amputation (F).

Case 2

A 20-year-old male patient was applied to our clinic with initial complaints of swelling in his right knee that had been ongoing for 5 months during his military service. The patient presented with a core-needle biopsy result indicating a subperiosteal aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC), which was performed at another center. Approximately 4 months after the onset of his complaints, the patient was discharged from military service due to the development of difficulty in gait and weight loss, and subsequently applied to our hospital.

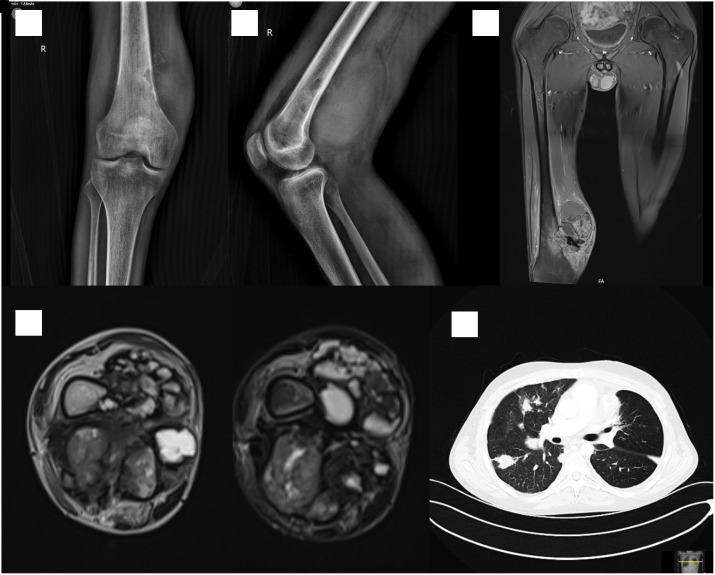

Limited range of motion at the right knee accompanied by a painful 12 × 10 cm soft-tissue mass in the distal posteromedial aspect of the right thigh was present at the initial examination. The radiologic work-up for the lesion is shown in Figure 3. The patient’s biopsy was repeated. In the core-needle biopsy, a giant cell tumoral lesion, woven bone formation, and suspicious atypical osteoid formation were observed. The presence of atypical osteoid production was considered to be indicative of a GCRO as discussed in the Institutional Tumor Board. No other tumoral focus was detected in PET–CT, and the patient underwent distal femur resection and reconstruction with tumor prosthesis following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The histopathological evaluation of the resected specimen revealed a GCRO. Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered in the postoperative period by the medical oncology department.

Figure 3.

Radiographs (A and B), contrast-enhanced coronal T1 weighted FatSat (C), T1 and T2 weighted FatSat (D) MR images at the presentation. The tumor is spreading out to the popliteal fossa through an osteolytic lesion at the medial metaphyseal cortex of the right femur. The patient presented with multiple visceral metastases 8 months after the distal femur resection (E).

Eight months after the resection, the patient presented with a painful, firm, fixed, non-pulsating 3 × 3 cm soft-tissue mass in his right popliteal fossa. A subsequent biopsy showed recurrence of the GCRO. A PET–CT scan revealed extensive metastatic lesions in the lungs and brain, which led to admission of 10 courses of radiotherapy. The patient was alive with metastases under the supervision of the medical oncology department.

Case 3

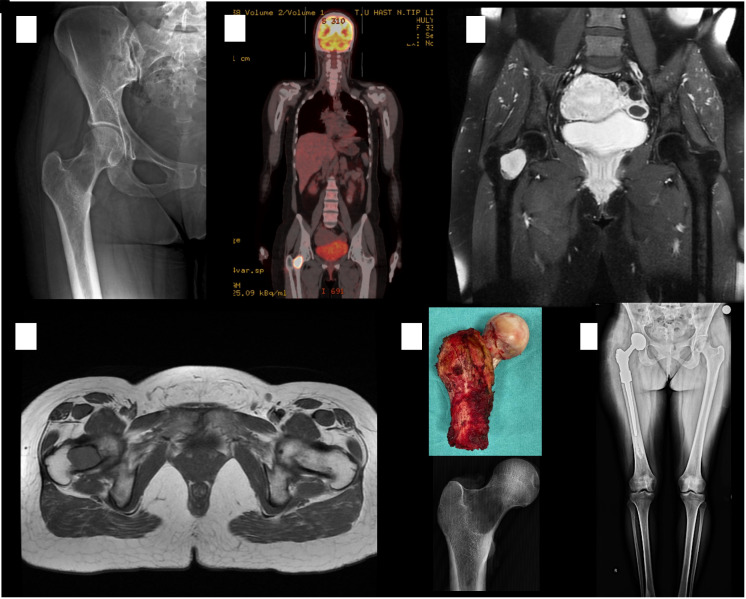

A 33-year-old female patient applied to an outpatient clinic with a complaint of pain in her right groin and limping for the last 2 months. A right hip joint examination was painful. Radiographs revealed an osteolytic lesion with a wide zone of transition at the right femoral neck with partially ill-defined borders. An intramedullary lesion extending from the subcapital region to the intertrochanteric area was seen on MR and CT images (Figure 4). Considering these findings, a differential diagnosis of GCTB was considered by the Tumor Board. A core-needle biopsy was performed with the preliminary diagnosis of GCTB, and the result was spindle cell malignant mesenchymal tumor. A direct wide resection and reconstruction with tumor prosthesis without neoadjuvant treatment was planned for the patient due to the low-grade characteristics of the tumor. Pathology examination after resection reported the patient’s tumor as GCRO. The patient was referred to the medical oncology department, where adjuvant chemotherapy was administered. After the patient’s treatment was terminated, she was followed up in remission.

Figure 4.

Radiograph showing an osteolytic lesion with an ill-defined border at the right femoral neck (A). PET–CT scan showing increased FDG uptake at the right femoral neck (B). MRI scans demonstrating an intramedullary mass showing hypointense signals in T1-weighted and hyperintense signals in T2-weighted images (C and D). The patient underwent a right proximal femoral resection with a diagnosis of low-grade spindle cell malignant mesenchymal tumor (E and F).

Histopathological diagnosis

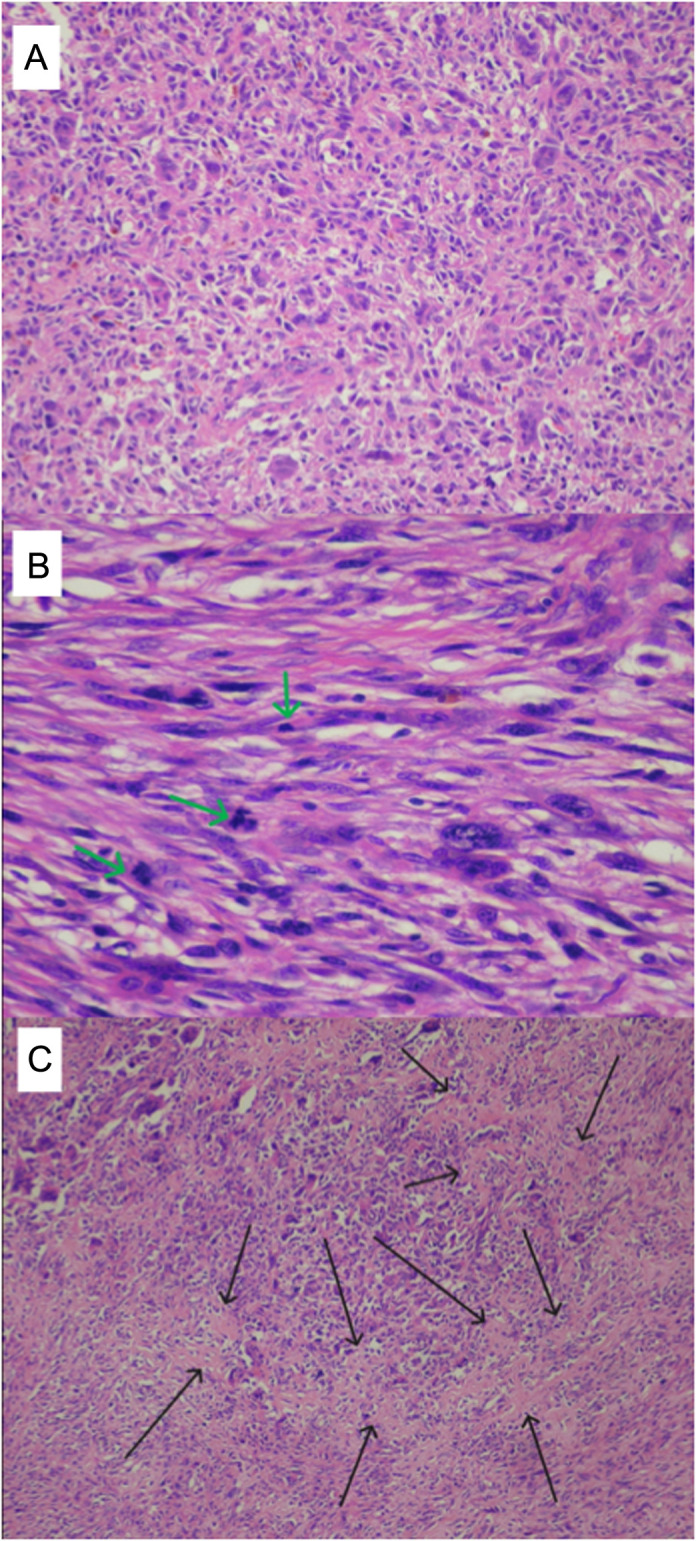

The tissues observed in the sections of all 3 cases were largely composed of giant cell areas without atypia and with old and new hemorrhage areas. The tumor, which had destroyed and eliminated a large part of the trabecular bone, contained areas with lace-like osteoid material and malignant cellular features in different areas in varying proportions (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Giant cell rich areas of the tumor without evidence of malignancy (HE ×200) (A). Malignant tumor areas with spindling of the mesenchymal cells harboring prominent atypical nuclei and high number of mitotic figures (green arrows) (HE ×400) (B). Malignant tumor areas with spindling of the mesenchymal cells harboring prominent atypical nuclei and high number of mitotic figures (black arrows) (HE ×400) (C).

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Trakya University Ethics Committee with the approval number TÜTF-GOBAEK 2023/474 on 11.12.2023 and was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki Standard of 1964, as revised in 1983 and 2000. All patients were informed about the study in detail before providing written informed consent for enrollment.

Discussion

Osteosarcoma is an osteoblastic primary malignant tumor that typically appears in the seconddecade around the knee, characterized by osteoblastic involvement of metaphyseal bone and malignant periosteal reaction.4 Several variants of osteosarcoma with different anatomo-clinical presentations, treatments, and prognosis were reported.9 In the majority of cases, tumor type is conventional osteosarcoma, which arises from metaphyseal bone, rapidly grows, and spreads to the surrounding soft tissue, and has very characteristic radiographic features.10 Because of this reason, osteosarcoma is not at the forefront in the differential diagnosis of young adult patients presenting with osteolytic bone lesions.6 In the differential diagnosis, the possibility of telangiectatic osteosarcoma, a rare tumor with purely osteolytic radiographic features that can be confused with ABC, should not be ignored.11 However, telangiectatic osteosarcoma is a tumor with an aggressive clinical course and relatively unique radiological findings such as a concentric location within the bone, expansile, ill-defined purely osteolytic and destructive X-ray findings alongside fluid–fluid levels, a multicystic pattern (hyperintense signal in both T1 and T2 because of fluid and hemosiderin component), and soft tissue component with contrast enhancement. Diagnosis is not difficult in the presence of clinical and radiological suspicion.11

In adult patients presenting with osteolytic metaphysioepiphyseal bone lesions, GCTB, Brown tumor, plasma cell disorders and bone metastases should be considered in the preliminary diagnosis.12 When radiological and laboratory and systemic screening findings are evaluated together, it is inevitable that rare tumors such as GCRO should also be included in the differential diagnosis.13

Giant cell tumor of bone, formerly known as osteoclastoma, is a benign bone tumor that can be confused with many benign and malignant bone tumors, often characterized radiographically by ill-defined metaphysoepiphyseal osteolytic lesions.14 Giant cell tumor of bone has very rare potential for sarcomatous transformation unless radiotherapy is applied.15 Conventional treatment for GCTB is based on extended intralesional curettage and filling the cavity with bone cement.14 Case 1 was diagnosed as GCTB and underwent recurrent intralesional treatments; the tumor recurred more aggressively each time. Very early (within months after curettage) and aggressive local recurrences after surgical treatment of GCTB are not normally expected.16,17 Sarcomatous transformation is a condition that can develop within years, perhaps decades, even in the presence of a condition that facilitates transformation, such as radiotherapy.15 The presence of multiple and aggressive local recurrences is sufficient to raise suspicion about the initial diagnosis. Although sarcomatous transformation was among the preliminary diagnoses, GCRO diagnosis was clarified by the histopathological examination reporting malignant osteoid formation in large areas in the tumor stroma consisting of osteoclast-type multinuclear giant cells in this case. This case emphasizes the significance of thorough diagnostic processes and other differential diagnosis alternatives, such as GCRO, in the therapy of osteolytic bone lesions in young individuals, particularly when the initial diagnosis is inconsistent with the clinical course.

The second presented case was initially diagnosed as ABC based on a previous biopsy result. However, GCRO was identified following a re-biopsy and thorough pathological investigation at our institution. This case further highlights the importance of considering GCRO in the differential diagnosis when osteolytic bone lesions are encountered, even in the presence of an initial biopsy suggestive of GCTB or ABC. In this case, despite a benign biopsy result, the clinical picture progressed rapidly. Due to the discordance between pathological and clinical diagnoses, there was a delay in the treatment of the rapidly progressing disease, and unfortunately the disease became metastatic.

The third case included a patient who presented with hip pain and had an osteolytic bone lesion in the femoral neck on imaging. A bone biopsy was performed, and the diagnosis of GCRO was made. This case demonstrates that GCRO can occur in different localizations in the skeleton and should be included in the differential diagnosis of osteolytic bone lesions regardless of localization. In this case, the radiological preliminary diagnosis was GCTB, while the differential diagnosis included Brown tumor, plasma cell disease, carcinoma metastasis (especially RCC), and GCRO. As a matter of fact, the biopsy showed that the lesion was GCRO, and the prognosis of the patient who was diagnosed early was also promising.

Bathurst et al18 first described GCRO as osteoclast-rich osteosarcoma in 1986 and pointed out that it is very difficult to distinguish this rare tumor from benign lesions. Sundaram et al8 reported 4 osteosarcoma cases presented by lytic-cystic radiographic and osteoclast-rich histopathologic features. Authors reported those cases as pseudo-cystic osteosarcoma. Since GCRO is very rare, it is only reported in the literature as case reports or series.6,13,19 Chow6 reported that nearly 35 cases of GCRO have been reported in the English literature. The cases presented in our article are consistent with the literature, demonstrating the aggressive nature of GCRO, often requiring a combination of surgical resection and chemotherapy, and the possibility of recurrence and metastasis.

Conclusion

Our study highlights the importance of considering GCRO in the differential diagnosis of osteolytic bone lesions in young adults. The complex diagnostic process, often involving multiple biopsies and consultations, and the resulting poor prognosis (need for amputation in one case, and systemic disease spread in 1 case) reflect the need for greater awareness and research on this rare and aggressive variant of osteosarcoma. Osteosarcoma may manifest radiologically as mixed osteolytic-osteoblastic lesions, or different osteosarcoma variants may show different radiological features. Clinicians should have a high degree of suspicion for GCRO in young adults with metaphysoepiphyseal osteolytic bone lesions because it is uncommon and frequently manifests with unusual radiologic findings. Misdiagnosis can lead to delay in treatment, which contributes to poor outcomes, emphasizing the critical need for an accurate diagnosis. In conclusion, the problems involved with the diagnosis and treatment of GCRO are substantial, but the relevance of considering this rare variant in the differential diagnosis of osteolytic bone lesions in young adults is critical for optimizing patient outcomes. Discussing the clinical, radiological, and histopathological findings (and histopathological re-evaluation in case of necessity) with a multidisciplinary team work known as the Tumor Board aids in the resolution of this diagnostic enigma. The cases presented here serve to highlight these points and contribute to the growing body of knowledge about this rare but important disease.

Funding Statement

The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Trakya University (Approval no.: TÜTF-GOBAEK 2023-474;; Date: 11.12.2023).

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patients who agreed to take part in the study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept – M.C., C.Ü.; Design – M.C., C.Ü.; Supervision – F.E.U., U.U.; Resources – M.C., F.E.U.; Materials – F.E.U., U.U.; Data Collection and/or Processing – C.Ü., F.E.U.; Analysis and/or Interpretation – F.E.U., U.U.; Literature Search – M.C., C.Ü.; Writing – M.C., F.E.U.; Critical Review – M.C., U.U.

Acknowledgements: None.

Declaration of Interests: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Campanacci M. In: Campanacci M, ed. Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors: Clinical Features, Imaging, Pathology and Treatment. Springer; Vienna, Vienna; 1999:1 70. ( 10.1007/978-3-7091-3846-5_1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eftekhari F. Imaging assessment of osteosarcoma in childhood and adolescence: diagnosis, staging, and evaluating response to chemotherapy. In: Jaffe N, Bruland OS, Bielack S, eds. Pediatric and Adolescent Osteosarcoma. Springer; US; 2010:33 62. ( 10.1007/978-1-4419-0284-9_3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Campanacci M. High grade osteosarcomas. In: Campanacci M, ed. Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors: Clinical Features, Imaging, Pathology and Treatment. Springer; Vienna, Vienna; 1999:463 515. ( 10.1007/978-3-7091-3846-5_28) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Picci P. Classic osteosarcoma. In: Picci P, Manfrini M, Fabbri N, Gambarotti M, Vanel D, eds. Atlas of Musculoskeletal Tumors and Tumorlike Lesions: the Rizzoli Case Archive. Springer International Publishing, Cham; 2014:147 152. ( 10.1007/978-3-319-01748-8_34) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hong SJ, Kim KA, Yong HS, et al. Giant cell-rich osteosarcoma of bone. Eur J Rad Extra. 2005;53(2):87 90. ( 10.1016/j.ejrex.2004.12.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chow LT. Giant cell rich osteosarcoma revisited-diagnostic criteria and histopathologic patterns, Ki67, CDK4, and MDM2 expression, changes in response to bisphosphonate and denosumab treatment. Virchows Arch. 2016;468(6):741 755. ( 10.1007/s00428-016-1926-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chow LT. Fibular giant cell-rich osteosarcoma virtually indistinguishable radiographically and histopathologically from giant cell tumor-analysis of subtle differentiating features. APMIS. 2015;123(6):530 539. ( 10.1111/apm.12382) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sundaram M, Totty WG, Kyriakos M, McDonald DJ, Merkel K. Imaging findings in pseudocystic osteosarcoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176(3):783 788. ( 10.2214/ajr.176.3.1760783) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yasko AW. Surgical management of primary osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Res. 2009;152:125 145. ( 10.1007/978-1-4419-0284-9_6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mei J, Zhu XZ, Wang ZY, Cai XS. Functional outcomes and quality of life in patients with osteosarcoma treated with amputation versus limb-salvage surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(11):1507 1516. ( 10.1007/s00402-014-2086-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Picci P. Telangiectatic osteosarcoma. In: Picci P, Manfrini M, Fabbri N, Gambarotti M, Vanel D, eds. Atlas of Musculoskeletal Tumors and Tumorlike Lesions: the Rizzoli Case Archive. Springer International Publishing, Cham; 2014:153 156. ( 10.1007/978-3-319-01748-8_35) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Steffner RJ, Jang ES. Staging of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas. JAAOS. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018;26(13):e269 e278. ( 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00055) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang CS, Yin QH, Liao JS, Lou JH, Ding XY, Zhu YB. Giant cell-rich osteosarcoma in long bones: clinical, radiological and pathological features. Radiol Med. 2013;118(8):1324 1334. ( 10.1007/s11547-013-0936-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gundavda MK, Agarwal MG. Extended curettage for giant cell tumors of bone: A Surgeon’s view. JBJS Essent Surg Tech. 2021;11(3):e20.00040. ( 10.2106/JBJS.ST.20.00040) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Manfrini M. Giant cell tumor. In: Picci P, Manfrini M, Fabbri N, Gambarotti M, Vanel D, eds. Atlas of Musculoskeletal Tumors and Tumorlike Lesions: the Rizzoli Case Archive. Springer International Publishing, Cham; 2014:91 94. ( 10.1007/978-3-319-01748-8_20) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barnaba A, Colas M, Larousserie F, Babinet A, Anract P, Biau D. Burden of complications after giant cell tumor surgery. A single-center retrospective study of 192 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2022;108(4):103047. ( 10.1016/j.otsr.2021.103047) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Errani C, Ruggieri P, Asenzio MA, et al. Giant cell tumor of the extremity: a review of 349 cases from a single institution. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(1):1 7. ( 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.09.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bathurst N, Sanerkin N, Watt I. Osteoclast-rich osteosarcoma. Br J Radiol. 1986;59(703):667 673. ( 10.1259/0007-1285-59-703-667) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nagata S, Nishimura H, Uchida M, Hayabuchi N, Zenmyou M, Harada H. Giant cell-rich osteosarcoma of the distal femur: radiographic and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Radiat Med. 2006;24(3):228 232. ( 10.1007/s11604-005-1546-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Content of this journal is licensed under a

Content of this journal is licensed under a