Abstract

BACKGROUND: Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is a rare autoimmune disorder affecting the central nervous system that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential to minimize long-term disability. Recent advances in the understanding of the pathophysiology of NMOSD have led to multiple new therapies, but significant care and knowledge gaps persist.

OBJECTIVES: To summarize current knowledge about the burden of disease and diagnosis and treatment of NMOSD in order to support managed care professionals and health care providers in making collaborative, evidence-based decisions to optimize outcomes among patients with NMOSD. In addition, this review also presents findings of a patient survey that provides insight into real-world experiences of those living with NMOSD.

SUMMARY: Diagnosis of NMOSD is based on detection of immunoglobulin G antibodies to the water channel protein aquaporin-4 (AQP4-IgG) in the context of compatible clinical and magnetic resonance imaging features. Patients who are AQP4-IgG seronegative and/or who are positive for myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies may also satisfy criteria for NMOSD. The rarity of the condition combined with the significant overlap in clinical features with other autoimmune diseases affecting the central nervous system, most notably multiple sclerosis, can delay accurate diagnosis, which in turn can delay appropriate treatment, leading to the accumulation of long-term disability. Accumulating disability associated with NMOSD has a substantial negative impact on quality of life. The disease typically evolves as relapsing (ie, repeated) acute attacks. Treatment consists of management of acute attacks, prevention of subsequent attacks, and management of acute and chronic symptoms. The armamentarium of therapies to prevent attacks consists of several monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) approved to treat AQP4-IgG–seropositive disease and several off-label therapies used for patients with either seropositive or seronegative disease. There is limited evidence to guide treatment decision-making, including which therapies to use first line, when to switch, and when to use monotherapy vs combination therapy. In addition, therapies with the greatest demonstrated safety and efficacy in NMOSD are costly and may not be accessible to all patients. Moreover, the results of the patient survey revealed significant clinical and financial burdens to patients with NMOSD including frequent attacks, delays in therapy initiation, need for urgent care and repeat hospitalizations, new and worsening symptoms, accumulating disability, and difficulties affording care. As such, key stakeholders must weigh them against the substantial economic costs of untreated or suboptimal treatment of disease.

DISCLOSURES: Dr Wingerchuk has served on the advisory board or panel for Alexion, Biogen, Genentech, Horizon, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Novartis, Roche, UCB, and Viela Bio and has received grants of research support from Alexion. Dr Weinshenker has served as a consultant or on the advisory board or panel for Alexion, Genentech, Horizon, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Roche, UCB, and Viela Bio, served on the speakers bureau or other promotional education for Genentech and Roche, and has received royalties from RSR Ltd.

This activity is provided by PRIME Education. There is no fee to participate. This activity is supported by independent medical educational grants from Genentech.

Advances in our understanding of the pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) have led to clinical breakthroughs in the diagnosis, treatment, and management of this devastating disease. This review will summarize the latest evidence on the incidence/prevalence of NMOSD, burden of disease, both physical and socioeconomic, diagnosis and differentiation of NMOSD from similar diseases, treatment of acute relapses, clinical trial data on prevention of subsequent attacks, and management of symptoms. In addition, contemporary insights into the experiences of patients with NMOSD emphasize the multifaceted challenges that patients face in managing their disease and provide opportunities for providers and managed care professionals to close gaps in management and contribute to the delivery of optimal care.

NMOSD is a rare chronic autoimmune inflammatory condition affecting the central nervous system (CNS). The central pathogenesis of NMOSD is believed to be antibodymediated astrocyte dysfunction and destruction, resulting in secondary demyelination and neurodegeneration.1,2

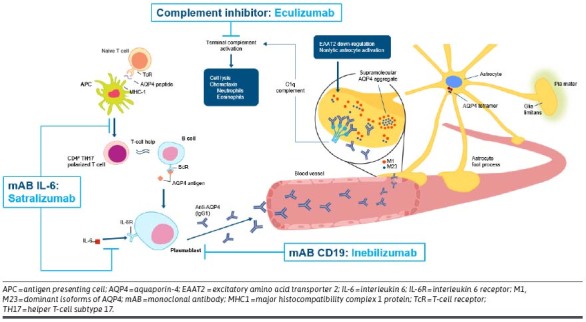

Formerly known as Devic disease, and once thought to be a rare form of multiple sclerosis (MS), understanding of the pathophysiology of NMOSD was substantially improved with the recognition of the association of the disease with serum immunoglobulin G-class antibodies to the water channel protein aquaporin-4 (AQP4-IgG).2 Patients with similar clinical and neuroimaging features who test negative for serum AQP4-IgG are sometimes are found instead to have serum IgG antibodies to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG-ab). Such patients may or may not satisfy clinical criteria for NMOSD, but clinical, radiological, and other evidence strongly support the current expert consensus that they have a distinct disease termed myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disorder (MOGAD). Although pathogenic AQP4-IgG are found exclusively in NMOSD, as many as 20%-30% of patients with NMOSD are seronegative for AQP4-IgG, and up to 42% of patients with NMOSD who are seronegative for AQP4-IgG are seropositive for MOG-ab.2 In very rare cases, patients may be positive for both antibodies.2 The patholophysiology of NMOSD with AQP4-IgG involves B cells, T cells, plasma cells, complement,1 and interleukin 6 (IL-6).3 As a result, these are all potential targets for biologic therapies (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Pathogenesis of NMOSD and Therapeutic Targets

There is growing evidence of differences in clinical presentation, severity, morbidity, and mortality of NMOSD among various racial and ethnic groups.4 Prevalence estimates for NMOSD range from 0.7 to 10/100,000 persons across most populations around the world, but the disease occurs more commonly among individuals of Asian or African ancestry. The lowest prevalence is observed among those with European ancestry.5

The condition is more common in women than men (female to male distribution 5-9:1)3,5,6 and usually first manifests between the ages of 30 and 40. Nevertheless, NMOSD can occur in patients of any age, including children.3,5 Disease onset or relapse has been associated with preceding infection, vaccination, or pregnancy/delivery.7

Burden of Disease

NMOSD has a pattern of repeated relapses in approximately 90% of patients.1 Attacks of myelitis, typically with “longitudinally extensive” spinal cord lesions, and attacks of optic neuritis are the most common manifestations. About 20% of patients experience, often as the first symptom, attacks of prolonged vomiting and/or hiccup, often unresponsive to conventional treatments for these symptoms but responsive to corticosteroids.8 Other brain or brainstem syndromes may eventually be observed, with encephalopathy notably occurring more commonly in children.9 Findings on cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) analysis differ in some respects from those in MS; a partly neutrophilic pleocytosis may be observed in the CSF, something hardly ever observed in MS.10,11 Unlike MS, oligoclonal bands are detected in spinal fluid in a small minority of individuals (less than 20%), whereas oligoclonal bands are present in more than 80% of patients with MS.9

Comorbidities, particularly other autoimmune diseases (eg, myasthenia gravis, lupus, and Sjögren syndrome), occur more commonly among individuals with NMOSD than those without the disease,2 and the presence of comorbidities amplifies the disease burden.12

Most individuals with NMOSD experience a relapsing disease course. Each relapse has the potential to require hospitalization and carries a risk of debilitating and often irreversible symptoms, including a small but still important risk of death from respiratory failure when associated with upper cervical or medullary inflammation.13,14 Complications from attacks of NMOSD include loss of visual acuity, motor strength, and sensory function, painful spasms, and death.13 A retrospective analysis of 871 attacks in 185 patients with NMOSD revealed that only 22% of patients completely recovered from a treated attack, with no residual disability remaining.15 Among patients with severe attacks, Bonnan et al found that on average, after 3 episodes of myelitis, patients may be rendered paraplegic, and after 1.5 episodes of optic neuritis in an eye, patients may be rendered blind.16 It has been reported that approximately half of patients with untreated NMOSD will be blind and require a wheelchair, and 33% of patients will die within 5 years of their first attack.10,13 However, ascertainment bias may have resulted in overestimates of disease severity in studies that predate current diagnostic criteria. In one study of 50 patients with MOG antibodies who met the criteria for NMOSD, 40% had significant disability, including impaired vision/functional blindness (36%), and limited ambulation due to paresis or ataxia (25%).7

Costs of care for NMOSD are significant. Individuals with NMOSD frequently report a high financial burden of disease largely secondary to cost of medications, hospital admissions, and outpatient/emergency department visits.17 In a 2022 patient survey conducted in the United Kingdom, mean 3-month total health care costs for patients with NMOSD were £5,623 ($6,793 USD) but ranged from £562 to £32,717 ($679 to $39,525 USD) when stratified by increasing Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score ranges. Mean 3-month costs of informal care (unpaid care or assistance provided by friends or family members) were valued at £13,150 to £24,560 ($15,886 to $29,670 USD).18 A 2022 German study reported that mean total annual per capita cost of illness were €59,574 ($70,297 USD), with the costs associated with the need for care from untrained people such as relatives accounting for 28% of total costs, indirect costs accounting for 23%, and drugs accounting for 16%. Costs increased with greater disease severity.19 A US-based retrospective, observational study that covered the period from 2012 to 2019 estimated mean annualized all-cause health care expenditure among patients with NMOSD of $60,599, compared with $8,912 among an age- and sexmatched comparative group.20 The mean annualized total expenditure for NMOSD relapses was $10,070 per patient, with hospital/inpatient care requiring more expenditure than ambulatory/outpatient care. Finally, a 2020 crosssectional survey by Huang et al of 210 patients from across 25 provinces in China revealed that 88.1% of patients with NMOSD found health insurance insufficient to pay all disease-related costs.21 Concerns about treatment side effects and financial burden contributed to diminished quality of life (QoL).

Reduced QoL is commonly reported by patients with NMOSD,22-23 with pain as a major contributing factor.5,22 As many as 80%-100% of patients with NMOSD have chronic pain, including neuropathic pain, pain attacks, or headache.23,24 Pain associated with NMOSD routinely interferes with work and relationships, with many patients unable to obtain relief despite treatment.5,23,24 Symptoms other than pain that negatively affect QoL in NMOSD include reduced mobility, anxiety, depression, bowel/bladder dysfunction, visual impairment,25 sexual dysfunction, and inability to work.26,27 Dysautonomia associated with NMOSD is often more severe than that in MS.5,28

In the Huang et al survey, which considered both QoL and costs, 61% of patients with NMOSD reported that the condition imposes a greatly negative impact on their QoL and that it worsens both physical and emotional health. Visual impairment, pain, and bowel and bladder dysfunction were the greatest negative physical determinants of overall QoL in this study. Only a small portion of patients (3.3%) exhibited psychological resilience, defined as poor physical health but very robust emotional health. In fact, NMOSD had a negative influence on the decision to have children in the study cohort. This latter finding was negatively correlated with age (r = -0.476; P < 0.001), suggesting it is of greatest concern among younger patients.21

Diagnosis of NMOSD

The diagnosis of NMOSD is primarily clinical but strongly supported by detection of AQP4-IgG in the serum as well as compatible and suggestive findings on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).29 The discovery of AQP4-IgG has revolutionized diagnosis by permitting a confident diagnosis at initial presentation in seropositive patients. Detecting AQP4-IgG can be accomplished by live or fixed cell-based assays revealed via immunofluorescence or flow-cytometry/fluorescence-activated cell sorting, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, or tissue-based assays. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting or visual-based indirect immunofluorescence (using recombinant AQP4-transfected cell lines or full-length human MOG-transfected cell lines for myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies [MOG-IgG]-associated disease) are recommended over enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay because of the lower sensitivity and specificity of the latter technique.30 Seronegative patients with clinical phenotypes strongly suspicious of MOGAD may also benefit from testing for MOG-IgG in the CSF.31 Among patients with features of NMOSD who initially test negative for AQP4-IgG, it may be worthwhile to retest in the future, as false negatives and/or seroconversion may occur. Retesting can be particularly important because all approved therapies for NMOSD are only approved for patients who are AQP4-IgG seropositive.32-34

Current diagnostic criteria mandate the presence of at least 1 syndrome with objective findings consistent with NMOSD in addition to the presence of AQP4-IgG and no longer require both optic neuritis or myelitis in a patient who is seropositive.29 Patients who are seronegative for AQP4-IgG can also be diagnosed with NMOSD, but they must have experienced 2, rather than 1, of the core clinical characteristics of the disease, either simultaneously or sequentially, and must satisfy other imaging requirements to improve the specificity of the disease. Full diagnostic criteria for NMOSD are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Diagnostic Criteria for NMOSD

| Core clinical characteristics |

|

| Diagnostic criteria for NMOSD AQP4-IgG–positive status |

|

| Diagnostic criteria for NMOSD AQP4-IgG–seronegative or unknown status |

|

| Additional MRI requirements for NMOSD AQP4-IgG–seronegative and NMOSD with unknown AQP4-IgG status |

|

AQP4-IgG = aquaporin-4; LETM = longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; NMOSD = neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder.

MRI characteristics of NMOSD include longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis with spinal cord inflammation that extends over 3 or more vertebral segments and longitudinally extensive lesions spanning half the length or longer of the optic nerve. Brain MRI features include normal/minimal nonspecific lesions, hypothalamic and medullary lesions, particularly when they are solitary lesions, and large cerebral lesions reminiscent of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, with "cloud-like" enhancement after gadolinium administration. Characteristics of NMOSD myelitis in patients who are AQP4-IgG seropositive include single longitudinally extensive lesions (often multiple in MOG-IgG–associated disease), lesions that are centrally located in the cord as seen on axial spinal cord sequences, “bright spotty lesions” (seen as very hyperintense T2 foci on axial images), and ring-like gadolinium enhancement on sagittal images.10

In addition to MS, conditions that may mimic NMOSD include sarcoidosis, metabolic disorders, such as biotinidase deficiency, paraneoplastic disorders, and some neoplasms (primary CNS lymphoma, ependymoma and hemangioblastoma of the spinal cord), among others.29,35,36

Predictors of Outcome

The evidence for factors that influence short- and longterm clinical outcomes among individuals diagnosed with NMOSD as well as the evidence that ties these predictors to each other is quite limited, but some demographic factors and clinical characteristics appear to be associated with attack frequency, severity, and recovery; accumulation of disability; and mortality. Several of these prognostic variables are listed here:

Disability increases with the number of attacks and attack severity.1,37

Recovery from attacks is worse in those older at disease onset.25,38-40

Younger patients have more severe attacks but recover better than older patients.41 However, overall outcomes are worse in those with childhood onset.42

More frequent attacks and a higher risk of death are observed in patients of African ancestry.5,39,40,43,44

Female patients have been observed to be at higher risk for all types of disability events,39 but male patients are more likely to develop permanent visual disability over time.37

The attack type at onset is positively associated with same attack phenotype at relapse.39

Specific clinical factors that have been linked with a higher risk of relapse risk or disability include brainstemonset attacks,39,45 longer length of myelitis lesions,25,46 optic neuritis at disease onset (with visual outcomes),47 and severity of initial attack.5,38,41

Compared with patients who are MOG-ab seropositive, those who are AQP4-IgG seropositive and those who are seronegative for both antibodies have lesser recovery from attacks and greater levels of disability.5,38

There has been no observed correlation between outcomes and the presence of gadolinium enhanced of CNS lesions.46

AQP4-IgG titers have not been shown to consistently correlate with relapse activity or disability after 5 or 10 years of follow-up.5,48

Time to receipt of treatment for acute episodes affects disability levels, a finding that highlights the need for rapid diagnosis and management of this condition.5,38,41

Role of Biomarkers

Biomarkers play an increasingly important role in the management of NMOSD, offering insight into diagnosis, treatment selection/switching, and prognoses. Currently available biomarkers relevant to NMOSD include antibody titers and persistence, B-cell counts, complement proteins, cytokines and other immunological markers, and markers of neuronal and astroglial damage.31

ANTIBODIES AND ANTIBODY TITERS

Identifying the presence of AQP4-IgG in the serum is an essential early step in the workup of patients with NMOSD, as their presence is a key component of the diagnosis.29 All currently approved therapies for this condition are indicated only for AQP4-IgG–seropositive disease and they have not demonstrated efficacy for AQP4-IgG–seronegative NMOSD.2 Nevertheless, there is no clear evidence that AQP4-IgG titers offer insight into prognosis or guidance in terms of treatment selection for individual patients. No consistent association has been found between serum titers at any given timepoint and disease prognosis; therefore, routine monitoring of AQP4-IgG titers in the serum or CSF of AQP4-IgG–seropositive patients is not recommended.31

MOG-IgG titers are influenced by several factors, including age, clinical presentation, and time since disease onset.31 There is some evidence, particularly in the pediatric setting, that high MOG-IgG titers at disease onset and persistently high titers predict a relapsing disease course.49,50 Thus, monitoring serum MOG-IgG titer over time is recommended.31 Testing MOG-IgG titers in the CSF may also play a role in identifying those rare patients with MOGAD when serum testing is unrevealing.31

B-CELL COUNTS

B-cell depleting therapies such as the anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody (mAb) inebilizumab and the anti-CD20 mAb rituximab have demonstrated activity in NMOSD.51,52 Thus, B cells have emerged as a potential biomarker to help monitor response to treatment and risk of relapse in those receiving such treatments. B cells in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells has been used in clinical trials to help inform infusion timing of rituximab.53 There is some evidence from observational studies54,55 that levels of CD19+CD27+but not total CD19 + cells are a reliable marker of biological relapse and could thus be used to decrease the frequency of treatment. Findings from the N-MOmentum clinical trial suggest sustained B-cell reduction among patients receiving anti-CD19 therapy was associated with a reduced annualized attack rate (AAR), with 4 or less cells/μL: AAR, 0.03 (0.02-0.04), more than 4 cells/μL: AAR, 0.09 (0.06-0.12), and placebo: AAR, 1.01 (0.79-1.23).56 Nevertheless, the utility of peripheral B-cell count monitoring for individual therapeutic decisionmaking (ie, alterations in drug dose and administration frequency) remains uncertain.

COMPLEMENT PROTEINS

The role of complement activation in NMOSD is well established,57 and targeting C5 is a proven therapeutic strategy.58,59 The role of complement proteins in MOGAD is less clear.31 Measurement of complement proteins as a tool for aiding in the differential diagnosis of NMOSD or for distinguishing NMOSD from MOGAD has yielded inconsistent results, as have evaluation of levels of complement proteins for use as a prognostic tool.31

CYTOKINES AND OTHER IMMUNOLOGICAL MARKERS

Interkeulin-6 (IL-6) is an established therapeutic target in both NMOSD and MOGAD.51-59 IL-6 may be a useful biomarker for differential diagnosis and may have some prognostic value.31 In particular, IL-6 measured in the CSF after a relapse may predict outcome and the occurrence of further relapses.60 Plasma concentrations of both IL-6 and IL-17 have been shown to correlate with both relapse and disability in NMOSD.61 Other cytokines and immunomodulatory markers relevant to NMOSD include IL-8, IL-10, C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand (CXCL) 8, CXCL10, CXCL13, B-cell activating factor, and A proliferation-inducing ligand. In MOGAD, relevant markers may be IL-8, IL-10, and human endogenous retroviruses. Additional research is needed to determine if these biomarkers will have clinical utility in aiding in differential diagnosis and prognosis.31

MARKERS OF NEURONAL AND ASTROGLIAL DAMAGE

Among multiple potential biomarkers of neuronal and astroglial damage, the two that have received the most attention in relation to NMOSD and related disease are neurofilament light chain (NfL) and glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP). Both are released into the CSF following axonal or astroglial injury and can also be detected in the blood, albeit at much lower levels and only using new single molecule assays.62 When using single-molecule array, serum NfL and GFAP may aid in differentiating NMOSD and MOGAD from one other as well as from other demyelinating disorders, although there may be overlap between some individuals with these conditions. In addition, serum NfL may be a marker of disability resulting from a relapse.31

In the N-MOmentum trial for inebilizumab, serum GFAP concentrations were associated with both risk of and severity of relapses. In addition, patients treated with inebilizumab had reductions in both risk of relapse and serum GFAP concentrations.51 Other research among patients with AQP4-IgG–seropositive NMOSD have confirmed the relationship between serum GFAP concentrations and risk of relapse.63,64 Increased concentrations of NfL and GFAP have also been linked with increased EDSS scores in this patient population.63,65,66 Serum GFAP rises in the majority of patients in advance of a relapse, especially when patients are not on an effective treatment. This biomarker in particular has the potential to help track subclinical inflammatory activity, distinguish relapses from pseudo relapses (clinical worsening because of fluctuation in existing disability rather than because of a new inflammatory event), identify nonresponders to treatment, identify high-risk patients in need of a more aggressive treatment approach, or identify need to initiate preventive treatment in patients not currently receiving it. Nevertheless, clinically relevant cut-off values are yet to be established.31 The role of these biomarkers in prognosis among patients with MOGAD is less clear.31

TREATMENT APPROACHES IN NMOSD

Treatment for NMOSD can be divided into 3 categories, based on the following primary goals: acute management, long-term relapse prevention, and management of symptoms. Traditionally, treatment approaches were guided by evidence from retrospective case series and consensus guidelines. More recently, an increase in the understanding of the underlying pathology has led to a shift toward use of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and other targeted therapies, each with randomized controlled trial (RCT) evidence demonstrating their efficacy and safety.2

ACUTE MANAGEMENT

Acute management refers to the management of acute attacks, whether it is a first attack or a relapse. The primary goals of acute management are to suppress acute inflammatory attacks, restrict CNS damage, and optimize recovery of neurological function.2 Early initiation of acute therapy is essential to prevent residual disability from attacks.41 Although there is still a need to identify an optimal attack treatment regimen,67 early aggressive management of acute relapses is generally recognized as the best approach.68,69 Current treatment options in the acute setting, which can be used alone or in combination, are:

Intravenous methylprednisone (IVMP), followed by oral tapered steroids: Usually used first line, this approach results in complete recovery in up to 35% of patients.2,3,15,70

Plasma exchange or immunoadsorption: Typically reserved for when response to IVMP is absent or inadequate, it can also be a first-line option (alone or in combination with IVMP) in severe cases.2,3,68,71 Initiating plasma exchange earlier vs later dramatically improves response rates.16 However, an important proportion of patients do not recover or do so minimally after plasma exchange, particularly those with absent deep tendon reflexes, which is an indicator of poor response.72,73

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG):2,3 One retrospective study of 10 patients with NMOSD revealed that IVIG had an effectiveness rate of 50% among those who failed to respond to IVMP,74 and another found IVMP plus IVIG to be more effective in severe attacks than IVMP used alone; especially when adding IVMP to IVIG therapy, better clinical improvement was observed (odds ratio = 5.85; 95% CI = 1.62-21.09; P = 0.007).75

The vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor bevacizumab76 and the anti-CD20 mAb ublituximab77 were shown to be safe in phase 1B trials of patients with NMOSD who presented with an acute attack, but additional studies have yet to be conducted. Ongoing trials of treatments for patients with AQP4-IgG–seropositive NMOSD experiencing acute exacerbations include the investigational anti-Fc receptor mAb HBM9161 (phase 1, NCT04227470) and the IVIG treatment NPB-01 (phase 2, NCT01845584).

LONG-TERM RELAPSE PREVENTION

In the setting of long-term management of NMOSD, the main goal is to minimize the frequency of relapse, with the ultimate aim of preventing accrual of disability from each relapse.2 The traditional approach to the long-term management of NMOSD has been the off-label use of classical immunosuppressants or therapeutic antibodies targeting CD20 or IL-6. Some of the most commonly used agents in this setting have been rituximab, azathioprine (AZA), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and tocilizumab (TCZ).2

More recently, the availability of the first disease-modifying drugs targeted to the underlying pathophysiology of the disease, as well as RCTs demonstrating their safety and efficacy, has led to an evidence-based approach to the long-term management of this condition.78 The first agent ever to be approved for the treatment of AQP4IgG-seropositive NMOSD was the complement inhibitor eculizumab (approved for use in the Europe and the United States in 2019), followed by the CD19 inhibitor inebilizumab (approved in the United States in 2020 and Europe in 2022), and finally the IL-6 inhibitor satralizumab (approved in the United States in 2020 and Europe in 2021).2,78 The anti-CD 20 mAb rituximab is also a commonly used treatment for NMOSD (approved in Japan in 2022),79 despite the fact that regulatory approval has not been sought for rituximab in this setting in the United States.52

Targeting C5

Eculizumab is a humanized mAb that inhibits the terminal complement protein C5 and prevents its cleavage into proinflammatory C5a as well as C5b, which coordinates the formation of membrane attack complex. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval was based on results of the PREVENT trial58 that enrolled 143 adults with AQP4IgG-seropositive NMOSD who were randomized 2:1 to receive either eculizumab 900 mg delivered intravenously (IV) weekly for the first 4 doses starting on day 1, followed by 1,200 mg every 2 weeks starting at week 4, or matched placebo.80 Patients could continue stable-dose immunosuppressive therapy (except rituximab) if they were using one at the time of enrollment. The time to first adjudicated relapse, the primary outcome, was reduced with eculizumab treatment (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.06; 95% CI = 0.02-0.20; P < 0.001), as was the rate of adjudicated annualized relapse (rate ratio = 0.04; 95% CI = 0.01-0.15; P < 0.001). Mean change in EDSS score was -0.18 with eculizumab and 0.12 with placebo group (least-squares mean difference = -0.29; 95% CI = -0.59 to 0.01). Eculizumab was associated with higher rates of upper respiratory tract infections and headaches. No events of meningococcal sepsis, a known potential adverse effect, was observed in the phase 3 study, but all patients were immunized. One death from pulmonary empyema occurred in the eculizumab group.58

Subsequent subgroup analyses of PREVENT revealed that benefits were observed across subgroups that were stratified based on immunosuppressive therapy, previous rituximab use, age, sex, region, race, time since clinical onset of NMOSD, historical annualized relapse rate (ARR), baseline EDSS score, and history of another autoimmune disorder. The same analysis revealed that rates of serious infection were lower with eculizumab vs placebo, regardless of rituximab use in the previous year, concomitant immunosuppressive therapy use, or history of another autoimmune disorder.59

The long-acting anti-C5 complement inhibitor ravulizumab-cwvz is currently being studied for NMOSD in a global, phase 3, open-label CHAMPION-NMOSD trial81 in 58 patients with AQP4-IgG–seropositive NMOSD. Initial outcomes data revealed that 0 patients experienced adjudicated relapses at a medium treatment duration of 73 weeks, with a relapse risk reduction of 98.6% (HR = 0.014; 95% CI = 0.000-0.103; P < 0.0001) compared with the PREVENT trial’s placebo arm.82 In a subgroup analysis using the same placebo comparison arm, ravulizumab-cwyz was superior in patients receiving monotherapy (n = 30; relapse risk reduction = 97.9%; HR = 0.021; 95% CI = 0.000-0.176; P < 0.0001) and in patients receiving concomitant therapy (n = 28; relapse risk reduction = 96.9%; HR = 0.031; 95% CI = 0.000-0.234; P < 0.0001).83 Among patients receiving ravulizumab-cwyz, 89.7% experienced no clinically important worsening in EDSS score compared with 76.6% of patients in the PREVENT placebo arm (not significant).82 Ravulizumab-cwyz was associated with a similar safety and tolerability profile as seen in previous studies and in realworld use. Two patients reported meningococcal infections but experienced full recovery without sequelae.82

Targeting IL-6

Retrospective case series of patients treated with the IL-6 antagonist, tocilizumab, including among treatment-refractory patients,84-87 suggested efficacy in NMOSD with AQP4-IgG. These studies led to the TANGO trial,88 an openlabel phase 2 trial in which TCZ significantly reduced the relapse rate compared with AZA (HR = 0.236; 95% CI = 0.107-0.518; P < 0.0001) among patients with NMOSD, with a lower rate of adverse events (61% vs 83%).

IL-6 antagonist treatment was optimized by development of a humanized monoclonal recycling antibody, satralizumab, which binds to and blocks soluble and membrane-bound IL-6 receptors and is reexported to the cell surface for further biological activity after being internalized after binding to its ligand. Satralizumab was FDA approved based on the results from 2 randomized controlled clinical trials. The first (SAkuraSky RCT)33 randomized 83 patients with AQP4-IgG–seropositive or -seronegative NMOSD 1:1 either to satralizumab 120 mg or placebo, administered by subcutaneous injection at weeks 0, 2, and 4 and every 4 weeks thereafter. This therapy was evaluated for efficacy as an add-on to a baseline treatment with a stable dose of AZA (maximum 3 mg/kg/day), MMF (maximum 3,000 mg/day), or oral glucocorticoids (maximum 15 mg prednisolone equivalent/day). Protocol-defined relapse (PDR) rates were reduced with satralizumab (HR = 0.38; 95% CI = 0.16-0.88), with greater reductions observed in the 55 AQP4-IgG–seropositive patients (HR=0.21; 95% CI = 0.06-0.75) than the 28 AQP4-IgG–seronegative patients (HR = 0.66; 95% CI = 0.202.24). Change in EDSS score was -0.1 with satralizumab and -0.21 with placebo (not significant). Effects of active therapy on pain and fatigue did not differ significantly from placebo, nor were there differences between the 2 groups with respect to the risk of serious adverse events (SAEs) or infections.

The second study (SAkuraStar RCT)32 randomized 168 patients AQP4-IgG–seropositive or seronegative NMOSD 2:1 to receive satralizumab 120 mg or visually matched placebo delivered by subcutaneous injection at weeks 0, 2, and 4 and monthly thereafter. Concomitant immunosuppressive treatment was not permitted in this study. PDRs were lower with active therapy (HR = 0.45; 95% CI = 0.23-0.89; P = 0.018). Rates of AEs, SAEs, and AEs leading to withdrawal were similar in both groups.

In a case series of 16 patients who participated in an open-label extension from SAkuraSky and who underwent steroid tapering, AAR did not increase from the doubleblind period.89

Results from follow-up of patients participating in the open-label extension of the SAkura studies have recently been reported in abstract form. In terms of efficacy, among 111 patients from SAkuraSky or SAkuraStar with AQP4IgG-seropositive NMOSD who received 1 or more doses of satralizumab during the double-blind or open-label extension periods of these trials, ARR remained stable after a combined 354.6 patient-years (PYs) of treatment. In the open-label extension, 73% of enrolled subjects in SAkuraSky and 72% in SAkuraStar were free from investigator-determined PDR at week 192.90

In terms of safety, 166 patients who received 1 or more doses of satralizumab during the double-blind period or the open-label extension and for whom the median treatment exposure was 205 weeks (range 4-311) in SAkuraSky and 157 weeks (range 5-265) in SAkuraStar were evaluated. Rates of AEs remained similar to those observed in the double-blind periods, at 389.6/100 PYs in SAkuraSky and 403.0/100 PYs in SAkuraStar. Rates of SAEs were 11.2/100 PYs and 12.2/100 PYs, respectively. Rates of infection were 130.5/100 PYs and 89.7/100 PYs, and rates of serious infection remained low, 3.5/100 PYs and 3.0/100 PYs, in SAkuraSky and SAkuraStar, respectively. These were similar to rates observed in the double-blind trials and were not higher than placebo.91

In a long-term follow-up of patients with both MOGAD and NMOSD, Ringelstein et al demonstrated that, after a median follow-up of nearly 2 years, TCZ therapy significantly reduced ARR in both NMOSD and MOGAD, with 60% of all patients remaining relapse free (79% for MOGAD, 56% for AQP4-IgG–seropositive NMOSD, and 43% for AQP4-IgG–seronegative NMOSD).34 Findings with TCZ by Ringelstein et al are particularly important given that there is currently no approved therapy for MOGAD.3

Targeting CD19/20

The anti-CD19, B-cell-depleting mAb inebilizumab was evaluated in the international N-MOmentum RCT51 and was FDA approved based on this study. In this trial, 230 adults with AQP4-IgG–seropositive or -seronegative NMOSD were randomized 3:1 to 300 mg IV inebilizumab or placebo administered on days 1 and 15 and followed for 6 months in the randomized portion of the study or until an attack occurred; more than 90% of enrolled patients were AQP4-IgG seropositive. The trial was stopped early because of the clearly demonstrated efficacy of inebilizumab, with a significantly reduced risk of an adjudicated attack (HR = 0.272; 95% CI = 0.150-0.496; P < 0.0001). Worsening in EDSS score was 16% in those receiving the study drug vs 34% receiving placebo. Rates of AEs were similar between the 2 groups, at 72% among patients on active therapy and 73% among patients on placebo. Rates of SAEs were 5% and 9%, respectively.51

Marignier et al used the N-MOmentum trial data to determine whether inebilizumab is as effective among patients with NMOSD who are AQP4-IgG seronegative as it is in patients who are seropositive.92 Most AQP4-IgG–seronegative patients did not meet screening criteria for the trial, highlighting difficulties in establishing diagnostic criteria for AQP4-IgG–seronegative NMOSD. Among the 16 AQP4-IgG–seronegative patients who were randomized, 12 received inebilizumab. Because the power was so limited for an assessment of the prospective data, AAR was compared between pretreatment and on-treatment periods; AAR was 0.048 (95% CI = 0.02-0.15) after treatment, compared with 1.70 (95% CI = 0.74-2.66) before the study in the total patient population. Among the 7 patients who were AQP4-IgG seronegative/MOG-ab seropositive, ARR was 0.043 (95% CI = 0.006-0.302) after treatment vs 1.93 (95% CI = 1.10-3.14) before the study. For the 9 patients who were AQP4-IgG seronegative/MOG-ab seronegative, ARR was 0.051 (95% CI = 0.013-0.204) before vs 1.60 (95% CI = 1.02-2.38) after. Data regarding efficacy of inebilizumab in AQP4-IgG–seronegative individuals remain inconclusive pending further study.

The anti-CD20 mAb rituximab has also been evaluated in NMOSD in the RIN-1 RCT52 that was conducted in Japan. In this trial, 38 patients aged 16-80 who were AQP4-IgG seropositive and were taking 5-30 mg/day of oral steroids but no other immunosuppressants were randomized 1:1 to rituximab 375 mg/m2 IV for 4 weeks, followed by rituximab 1,000 mg every 2 weeks, at 24 weeks and 48 weeks after randomization or to matching placebo. Concomitant oral prednisolone was gradually reduced to 2-5 mg/day, according to the protocol. Relapse rates at 6 months were 0% with rituximab vs 37% with placebo, for a group difference of 36.8% (95% CI = 12.3-65.5; log-rank P = 0.0058). The ARR was 0.0 vs 0.32, respectively,93 and rates of SAEs were 16% vs 11%, respectively. There were too few events in the treatment group of RIN-1 to calculate risk reduction.52 Rituximab may also provide some protection against relapse in MOGAD, but with a lower level of efficacy, compared with patients with NMOSD.94 However, no application for approval has been placed.

Another anti-CD20 agent that is being investigated for the treatment of NMOSD is the chimeric IgG1 mAb ublituximab. In a phase 1 pilot study, the agent was found to be a safe add-on agent that reduced EDSS score among 5 patients with NMOSD presenting with acute transverse myelitis and optic neuritis.77 In 2016, ublituximab was granted orphan drug designation for the treatment of NMOSD, but insufficient studies have been conducted to receive FDA approval.95

Open-Label Extension Evidence for Approved Therapies

The unblinded open-label extension data available to date for all 3 therapies currently approved in the United States for the treatment of NMOSD (eculizumab, inebilizumab, and satralizumab) suggest that all have persistent beneficial effects on relapse risk, with the caveat that these are uncontrolled, unblinded observations. In addition, the safety profile of each drug remains unchanged, with no clearly new or cumulative risks evident from open-label extension data. Details of the open-label extensions following the RCT of the 3 agents that have received regulatory approval in the United States are presented in Table 2.96-103

TABLE 2.

Efficacy and Safety of US Food and Drug Administration–Approved Therapies for NMOSD

| Pivotal studies | OLE results | OLE relapse rates | OLE AEs | OLE discontinuation | OLE EDSS scores | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eculizumab | PREVENT | 96.1% of patients initially receiving eculizumab and 94.8% initially receiving placebo were relapse-free at 192 weeks96 | The adjudicated ARR was 0.025 for the all eculizumab-treated patients96 | Rates of treatment-related AEs and SAEs were 62% (183.5/100 PY) and 13.9% (8.6/100 PY), respectively96 | 11.8% of patients (14 of 119) discontinued treatment96 | Mean EDSS scores maintained or continued to trend toward improvement96 |

| Inebilizumab | N-MOmentum | 87.7% of patients initially receiving inebilizumab and 83.4% initially receiving placebo remained attack-free for up to 4 years97 | The adjudicated ARR was 0.052 for the patients with AQP4+ receiving inebilizumab98 | Rates of treatment-related AEs and SAEs were 38.7% and 2.7%, respectively98 | 19.4% of patients (42 of 216) discontinued treatment99 | Mean EDSS scores for patients with AQP4+ were stable throughout98 |

| Satralizumab | SAkuraSky | 71% of satralizumab-treated patients were relapse-free at 192 weeks100 | The overall ARR was 0.11 from the first satralizumab dose to the cut-off date101 | Rates of AEs and SAEs were 383.4/100 PY and 13.7/100 PY, respectively101 | 21.4% of patients (9 of 42) discontinued treatment102 | 90% had no sustained worsening of EDSS100 |

| SAkuraStar | 73% of satralizumab-treated patients were relapse-free at 192 weeks100 | The overall ARR was 0.08 from the first satralizumab dose to the cut-off date101 | Rates of AEs and SAEs 324.8/100 PY and 10.6/100 PY, respectively101 | 18.2% of patients (6 of 33) discontinued treatment103 | 86% had no sustained worsening of EDSS100 |

AE = adverse event; ARR = adjudicated annualized relapse; EDSS = expanded disability status scale; NMOSD = neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; OLE = open label extension; PY = patient-year; SAE = serious adverse event.

Future Directions in Relapse Prevention

Several additional drugs are currently under early investigation for relapse prevention in NMOSD. Phase 3 clinical trials include the transmembrane activator and calcium modulator and cyclophilin ligand interactor (TACI)-antibody fusion protein injection telitacicept104 and mesenchymal stem cell therapy.105 Less advanced trials are evaluating the investigational anti-CD20 mAb BAT4406F106 and the investigational Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor SHR1459.107 Other potential future therapies include CD19/CD20 CAR-T cells, but recent early trials with these agents were withdrawn because of difficulty recruiting patients.108,109 Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has also shown promise in relapse prevention for NMOSD. In a prospective, open-label cohort study, Burt et al treated 13 patients with NMOSD HSCT. After a median follow-up of 57 months, 1 patient with comorbid systemic lupus erythematosus died from complications of the disease. Among the remaining 12 patients without other active coexisting autoimmune disease, 11 were followed up for more than 5 years after transplant, and 80% remained relapse-free off all immunosuppression. At 5 years, EDSS scores improved from a baseline of mean of 4.4 to 3.3 (P < 0.01). Also improved at 5 years were the Neurologic Rating Scale score and the Short Form-36 health survey for QoL total score. Among 11 patients who were AQP4-IgG seropositive at baseline, 9 became seronegative based on the immunofluorescence or cell-binding assays available at the time. The 2 patients who remained seropositive, with persistent complement activating and cell-killing ability, relapsed within 2 years of HSCT.110 A recent meta-analysis that included patients with both MS and NMOSD revealed progression-free survival of 76%, with no treatment-related mortality.111 Small pilot trials have suggested that the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib112 and the antihistamine cetirizine113 may help reduce the risk of relapse among patients already on standard therapy.

Clinical trials are also underway for MOGAD. The cos-MOG phase 3 clinical trial of rozanolixizumab, a humanized IgG4 mAb that targets the neonatal Fc receptor, that reduces plasma IgG levels, has begun recruitment.114

Aquaporumab is an investigational full human monoclonal antibody therapy with a novel mechanism of action; it is derived from a human AQP4-IgG and modified to act as an astrocyte protective agent by binding with high affinity to and thereby blocking access of pathogenic AQP4-IgG from binding to its target. This human mAb has undergone molecular modifications to render it non–complement fixing and unable to generate antibody-dependent cellular toxicity AQP4. Aquaporumab is undergoing preclinical assessment,115 but there are currently no ongoing clinical trials of aquaporumab for NMOSD.3

MANAGEMENT OF INDIVIDUAL SYMPTOMS

In addition to addressing acute attacks and preventing relapses, an important component of management of NMOSD is addressing individual symptoms as they arise. These symptoms can include, but may not be limited to:

Neuropathic pain

Tonic spasms and involuntary movements

Spasticity and muscle tone abnormalities

Bladder, bowel, and sexual dysfunction

Fatigue and sleep disorders

Psychiatric and cognitive impairment

Motor and visual dysfunction

These symptoms are typically addressed with therapies that are approved for or have demonstrated efficacy for the management of these specific symptoms for other indications, generally MS, rather than with therapies specifically designed for NMOSD.116

SPECIAL POPULATIONS: PREGNANCY AND PEDIATRICS

NMOSD is associated with an increased risk of pregnancy loss.117 The risk of relapse is either unchanged during pregnancy (compared with a significant decrease in MS) or perhaps heightened. It is increased in the postpartum period.118,119 This concern must be weighed against the possible teratogenic effects of treatment in pregnant patients. Treatments that appear to be relatively safe in pregnancy include AZA and rituximab; few data are available about approved drugs.120-122

Management of NMOSD in the pediatric setting is particularly challenging, as only 1 trial (SakuraSky) included pediatric patients.33 Ferilli et al have proposed a diagnostic and treatment algorithm for use in the pediatric setting.123 Pediatric patients with NMOSD should be prescribed immunosuppressive treatment. Until more experience is gained with newer agents in the pediatric setting, therapeutic options available for this age group include rituximab, AZA, or MMF.124

Patient Survey Findings

In a nation-wide survey conducted in the United States by PRIME Education in collaboration with the Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation, 80 patients with NMOSD completed a survey about the history of their disease, their individual goals for therapy, and their lived experiences with treatment, including key challenges they have faced. Patients with NMOSD were identified and contacted by the Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation and emailed a link to the survey. The outreach for survey participation was done one by one to ensure a diagnosis of neuromyelitis optica (no blast emails to organizational membership). PRIME provided nominal financial incentive in the form of a gift card upon survey completion. An initial goal was set at 75 completed surveys with 80 ultimately being collected. Statistical analyses were performed using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for counts less than 5. Note that the AQP4-IgG–seropositive rate of 70%, the preponderance of females (88%), and the high rate of comorbid autoimmune disease in this group reflects the current global profile for this disease, but this group differs from global estimates with regard to race and ethnicity, with the greatest proportion being White (66%).

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics of this patient population are presented in Table 3. The survey was conducted as part of an educational quality improvement program and was therefore exempt from institutional review board oversight.

TABLE 3.

Baseline Characteristics (PRIME NMOSD Patient Survey)

| Patients | N = 80 |

| Average age, years | 44 |

| Median | 46 |

| Range | 16-77 |

| Sex, n % | |

| Male | 11 (14) |

| Female | 69 (86) |

| Other | 0 (0) |

| Race and ethnicity (all that apply), n (%) | |

| African American/Black | 18 (23) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 (3) |

| Native American/Alaska Native | 1 (1) |

| Caucasian/White | 53 (66) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 12 (15) |

| Other | 0 (0) |

| Education level, n (%) | |

| High school or GED | 22 (27) |

| Associate degree | 18 (21) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 19 (23) |

| Postgraduate (master’s, PhD) | 10 (12) |

| Professional degree (MD, PharmD, DDS, JD) | 3 (4) |

| Other | 11 (13) |

| Health insurance status, n (%) | |

| Commercial or private plan | 30 (37) |

| Federal-exchange insurance | 5 (6) |

| Medicaid/Medicare | 36 (45) |

| TRICARE or VA health benefits | 4 (5) |

| I get my health care through IHS | 0 (0) |

| No insurance | 6 (7) |

| Years since diagnosis | 7 |

| Median | 6 |

| Range | 1-19 |

| Time period from symptoms to diagnosis, % | |

| 0-6 months | 49 |

| 6-12 months | 13 |

| 1-2 years | 9 |

| 2-4 years | 11 |

| More than 4 years | 19 |

| NMOSD type, % | |

| AQP4-IgG seropositive | 70 |

| AQP4-IgG seronegative | 23 |

| I am unsure | 8 |

| Positive test for MOG-IgG, % | |

| Yes | 15 |

| No | 64 |

| I am unsure | 21 |

| Misdiagnosed with MS, % | |

| Yes | 36 |

| No | 64 |

| Ever taken an MS-directed attack-prevention treatment, % | |

| Yes | 20 |

| No | 78 |

| I am unsure | 2 |

| Other diagnosed autoimmune diseases, % | |

| Myasthenia gravis | 3 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 3 |

| Sjögren syndrome | 14 |

| Thyroid disorder | 1 |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | 0 |

| Other | 17 |

| I do not have any of these conditions | 58 |

AQP4-IgG = aquaporin-4; GED = general educational development; IHS = Indian Health Services; MOG-IgG = myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein; MS = multiple sclerosis; NMOSD = neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; VA = Veterans Affairs.

TREATMENT-RELATED EXPERIENCES AND PERCEPTIONS

About half of patients (53%) were currently taking rituximab, 13% eculizumab, 8% satralizumab, 6% inebilizumab, and 2% TCZ. Among the remaining patients, 9% were on MMF, 7% prednisone, and 4% AZA. Approximately 5% of patients were not currently on therapy (Supplementary Table 1, available in online article). Approximately one-third of patients (32%) had only been on 1 preventive therapy for NMOSD, whereas 21% had been on 2, 24% on 3, and 23% on 4 or more (Supplementary Table 1). The greatest proportion of patients (41%) had been on their current therapy for 3 or more years, whereas 33% had been on it for 1-2 years, and 26% had been on it for less than 1 year (Supplementary Table 1). Patients felt moderately (20%), very (33%), or extremely (40%) confident that they understood their treatment plan (data not shown).

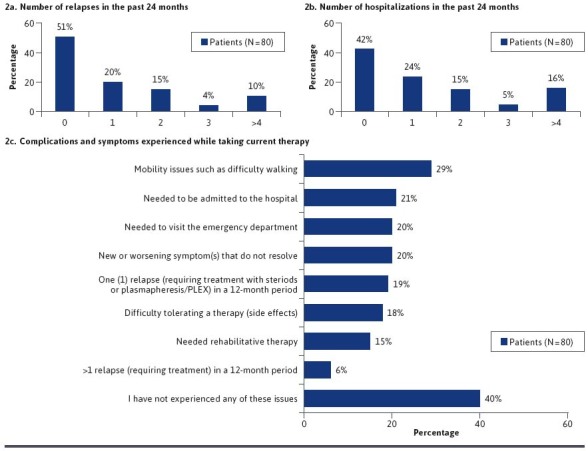

BURDEN OF DISEASE AND ASSOCIATED COMPLICATIONS

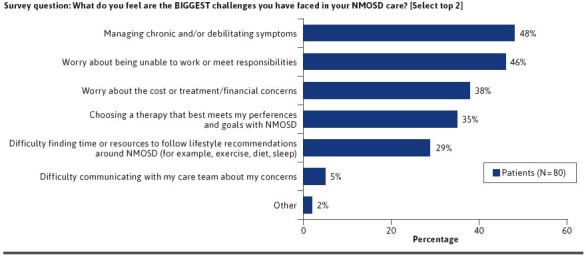

Health care resource utilization, symptoms, and complications associated with NMOSD are substantial.1 In order to gain further insights in this area, we asked survey participants about their experiences with relapses, hospitalization, and associated complications with NMOSD. Overall, 49% of patients recalled experiencing 1 or more relapses in the previous 24 months; 10% experienced 4 or more relapses (Figure 2A). Approximately 58% recalled being hospitalized in the previous 24 months; 24% were hospitalized once, 15% twice, 5% three times, and 16% four or more times (Figure 2B). While on therapy, the majority of patients reported experiencing disease-related complications or symptoms, such as difficulty walking, new or worsening symptoms, 1 or more relapses requiring treatment, and others (Figure 2C). The most common complication patients reported were mobility issues (29%). Additionally, 15% of respondents reported needing rehabilitative therapy. Difficulty tolerating therapy (side effects) was also frequent (18%) among the respondents. When asked to select the top 2 challenges faced in their NMOSD care, respondents identified 48% management of chronic/debilitating symptoms, 46% being unable to work or meet improved responsibilities, 38% costs of treatment/other financial concerns, 35% choosing therapy that best meets goals/preferences, and 29% fulfilling lifestyle recommendations as top concerns (Figure 3). These findings were consistent with published reports of challenges associated with a diagnosis of NMOSD.26,125

FIGURE 2.

Burden of Disease and Associated Complications (PRIME NMOSD Patient Survey Data)

FIGURE 3.

Challenges in NMOSD Care (PRIME NMOSD Patient Survey Data)

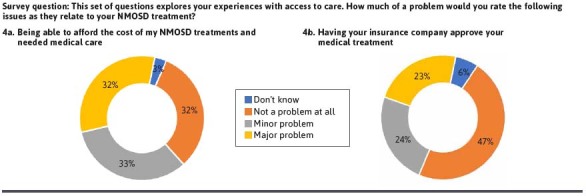

COST AND INSURANCE COVERAGE

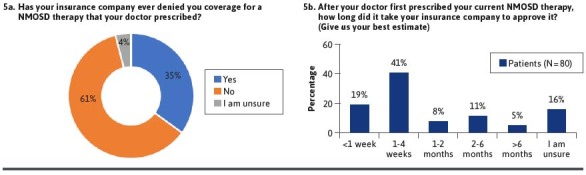

In addition to the clinical burden of NMOSD, the health care costs associated with NMOSD have been demonstrated to be substantial.17-21 We therefore asked patients about their ability to afford therapy and related medical care and about experiences with insurance coverage in order to assess patients’ access to care. When asked about their ability to afford NMOSD treatments and related medical care, 65% of respondents said that it was a problem, among whom 32% categorized it as a major problem (Figure 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Challenges With Access to Care Among Patients With NMOSD (PRIME NMOSD Patient Survey Data)

Obtaining health insurance coverage for medical treatment of NMOSD was reported to be problematic by 47% of respondents, with 23% reporting it was a major problem (Figure 4B). In a subgroup analysis comparing those with Medicare or Medicaid with those with private insurance, patients with Medicare or Medicaid were more likely to report that coverage for therapies was not a problem, although the difference was not statistically significant (Supplementary Figure 1). In addition, 35% of patients reported that their health insurance plan denied a prior authorization request for therapy that their provider prescribed (Figure 5A), most commonly rituximab (25%) (Supplementary Table 2). This may reflect the high use of rituximab for NMOSD and lack of regulatory approval for this drug. Furthermore, 11% of patients have had to switch therapies because of a prior authorization denial (Supplementary Figure 2). Prior authorization decisions took 1 week or less for only 19% of patients with the vast majority of patients waiting weeks to months for approval of their therapy (Figure 5B). The reasons for this delay are unknown but may have been related to trials of alternative therapies or requested transitions/overlap of therapies from old to new agents. These findings point to opportunities to streamline prior authorization processes and to support providers and patients in navigating managed care requirements.

FIGURE 5.

Challenges in Insurance Coverage and Approval (PRIME NMOSD Patient Survey Data)

NEED FOR IMPROVED COLLABORATION BETWEEN PAYERS AND PROVIDERS

Given the importance of early treatment to minimize long-term disability in NMOSD combined with difficulty obtaining access to and coverage of physician-recommended treatments, it is important for payers to collaborate with providers for patients with NMOSD. Considering the PRIME survey findings on prior authorization wait times and medication skipping, it is likely that cost concerns are driving patient behaviors that may promote otherwise avoidable acute attacks. These attacks, in turn, may increase the risk of long-term disability, which can have a negative impact on patient functioning and QoL and increase the economic burden of this disease.13-16,19,20 More than half of patients in the PRIME survey (53%) are currently being treated with rituximab, which is not FDA approved for NMOSD (Supplementary Table 1). It is likely that this is because of high historical use of this drug prior to regulatory approval of eculizumab, inebilizumab, and satralizumab. Although rituximab has been shown to have efficacy in NMOSD, use of rituximab over approved agents may be influenced by factors related to access/cost/insurance coverage as well as provider preference due to familiarity and comfort level with the treatment. As outlined in the following section, numerous opportunities exist for improved payer-provider collaboration across the NMOSD care continuum.

Opportunities for Payers and Providers to Close Gaps in the Management of NMOSD

ENSURING TIMELY AND ACCURATE DIAGNOSIS

Achieving an early diagnosis of NMOSD is critical because rapid initiation of treatment is associated with superior outcomes,5,38,41 potentially mitigating long-term disability, which is a key concern for patients.126 Diagnosis of NMOSD is complicated by overlap of clinical features with those of several other conditions, most of which are far more common, such as MS. Neuroimaging findings are often nonspecific, which can contribute to misdiagnoses.127 Unfortunately, most treatments for MS are not effective in NMOSD and may even contribute to increased risk of relapse.2,39,128-133 Accurate diagnosis of NMOSD and access to FDA-approved therapies requires AQP4-IgG testing, which is not readily available in all settings.134 It is possible, however, for providers to send samples to locations with antibody testing capability.

A study from China revealed that more than 70% of patients with NMOSD were initially given a different diagnosis, most commonly idiopathic optic neuritis (43.6%), MS (19.5%), a gastrointestinal disorder (11.0%), or depression (10.0%). The average time from first symptom onset to accurate diagnosis of NMOSD was 2.4 ± 4.9 years.21 Similar results were reported in a survey of patients with NMOSD in the United States, 67% of whom reported that they were initially misdiagnosed, most often with MS.23 Similarly, in our survey we found that 36% had received a diagnosis of MS and 20% had received treatment for MS. In addition, 19% of patients had a duration of more than 4 years between symptom onset and correct diagnosis (Table 3).

Providers and payers both have key roles to play in ensuring the provision of a timely diagnosis of patients with NMOSD. Payers can support providers in this context via policies that ensure easy and timely access to diagnostic testing, including imaging and laboratory analyses, and to relevant specialists when needed.

OPPORTUNITIES TO FACILITATE COMMUNICATION

Managed care professionals can promote self-efficacy among patients with NMOSD by facilitating communication between providers and patients and ensuring that providers have the capacity to allocate adequate time for appointments with patients. Provision of educational resources for both providers and patients, particularly regarding strategies that support overall physical and mental wellness, QoL, and long-term outcomes, could enhance patient-provider collaboration and patient satisfaction with care. Furthermore, increased patient satisfaction with patient-provider interactions has been correlated to greater adherence and self-care.135-138 Ultimately, goals of improved care and lowered cost are especially imperative in diseases such as NMOSD in which the consequences of inadequate or suboptimal treatment are both medically and financially significant.

Few Options for AQP4-IgG–seronegative Disease and Existing Disability

The greatest treatment gaps exist for those with AQP4-IgG–seronegative disease. All currently indicated treatments for NMOSD are approved only for those who are AQP4-IgG seropositive, and none have been proved to be effective in a phase 3 study of AQP4-IgG–seronegative patients.32-34 Drugs targeting C5 have not been evaluated in AQP4IgG-seronegative patients.58,81 Insufficient numbers of AQP4-IgG–seronegative patients have been treated with inebilizumab in the RCT to reach conclusions, but the drug appears to have been less effective than in AQP4IgG-seropositive patients, although comparing prewith on-treatment results, efficacy cannot be completely ruled out in this subgroup.92

A meta-analysis of RCTs of mAbs for NMOSD revealed that all mAbs included in the analysis (ie, eculizumab, inebilizumab, rituximab, satralizumab, and tocilizumab) reduced relapse rate in the AQP4-IgG–seropositive patients, but not AQP4-IgG–seronegative patients. Similar results were observed when RCTs involving only the anti–IL-6 mAb satralizumab were analyzed. However, mAb therapy in general did not significantly alter EDSS from baseline.139

Restoration of already lost function in NMOSD remains a daunting challenge for which few good options are available. Payers and providers can work together to support patients with AQP4-IgG–seronegative disease and existing disability by facilitating access to rehabilitative services, such as specialized physiotherapy, and ensuring provision of necessary supportive services, such as at-home care from appropriately trained professionals. These patients should also be made aware of the potential to participate in clinical trials of drugs in development.

Considerations for Treatment Selection

In general, treatment should be made as soon as a confident diagnosis of AQP4-IgG–seropositive disease is made. However, how to select among available treatments, when and how to switch therapies, and what type of disease monitoring is clinically useful to guide dosing remain challenges.93,140 Although it is essential to determine AQP4-IgG seropositivity in patients with NMOSD, seropositivity alone only qualifies patients for therapies approved in the United States but does not aid in selection among those therapies.141

There are limitations in the extent that one can compare results from trials of therapies for NMOSD because of differences in trial design, including eligibility criteria and outcome definitions. When comparing results, it is important to consider subgroups based on AQP4-IgG seropositivity because of important efficacy differences based on serostatus.93

In a network meta-analysis of the 4 randomized controlled trials that led to approval of eculizumab, inebilizumab, and satralizumab, the C5 inhibitor eculizumab prevented relapses more effectively than did mAbs with broader mechanisms of action, including satralizumab and inebilizumab; however, this study used group data and could not account for differences in study design including endpoint (attack) adjudication methods that may have contributed to variability in results.142 A pooled analysis of RCTs showed no significant differences among the mAbs rituximab, eculizumab, inebilizumab, and satralizumab for multiple efficacy endpoints and AEs, but a subgroup analysis suggested eculizumab may be the most effective option for decreasing on-trial relapse risk for AQP4-IgG–seropositive patients.143 These meta-analyses also have limitations of unknown degree whereby differences in study design and criteria for relapse definition between studies may influence comparative outcomes. A post hoc analysis was conducted of 17 patients from N-MOmentum who had previously been treated with rituximab, only 13 of whom were assigned to receive inebilizumab. Among the patients with prior rituximab experience, 94% had 1 or more infections while receiving inebilizumab.144 Pooled results suggest that, among the unapproved therapies for NMOSD, rituximab appears superior to MMF and AZA.145

Given the lack of data available to guide treatment selection, clinicians must frequently turn to expert opinion. Jarius et al have proposed a treatment algorithm that recommends use of approved treatments when available and feasible. In the setting of treatment failure, they recommend switching between any agents, with the caveat that patients who experienced treatment failure on a B-cell–depleting agent should avoid using another B-cell–depleting agent. However, there are preliminary reports from treatment of other conditions that anti-CD19 therapy may be effective in individuals who have failed anti-CD20 treatment, which was also supported by patients that experienced disease activity on rituximab and, after enrollment in N-MOmentum, remained relapse free on inebilizumab.146-149

In the PRIME patient survey, 82% of patients were taking a mAb for NMOSD (Supplementary Table 1A). Nevertheless, 49% had experienced at least 1 relapse in the previous 24 months (Figure 2A), and 58% had been hospitalized at least once during that same time period (Figure 2B). The mAb prescribed most often was rituximab (used in 53% of patients), which may reflect easier access/lower cost of this treatment in most settings, despite rituximab not having regulatory approval for NMOSD.

Mode of administration can impact cost of care, and patients’ preferences and experiences with different routes may also influence treatment adherence. Although both eculizumab and inebilizumab are administered via intravenous infusion, satralizumab is administered by subcutaneous injection. In a 2013 systematic review of drug administration costs, it was found that intravenously administered medications tended to have 6 times higher administration costs than those given subcutaneously.150 Furthermore, another review in 2019 of oncology biologics found that patients generally preferred subcutaneous formulations in addition to reporting better health-related QoL.151 A study in the Netherlands in 2018 broke down the costs further, finding that intravenous administration of trastuzumab and rituximab was about double the administration cost of subcutaneous administration, with the cost savings primarily attributed to time spent at the day care unit, as well as decreased time of health care professions, decreased costs of consumables required for administration, and reduced societal costs (traveling expenses, informal care costs, paid work, and unpaid work) with subcutaneous administration.152 Because of the repeated administrations necessary for patients to remain relapse free, the potential cost savings that are generated by considering mode of administration may be significant. However, they must be carefully weighed against the effectiveness of the therapy for the individual patient as the cost of relapse is far greater. Little evidence exists to guide the balancing of the cost savings of relapse prevention and cost of administration, but ultimately determining the optimal therapy selection for individual patients will be beneficial for patients, health care providers, and payers.

Payers can support optimal patient management by ensuring timely access to the therapies recommended by providers with expertise in NMOSD. Unnecessary delays in initiating optimal treatment, such as those created by mandating use of less optimal therapies prior to approving access to potentially more effective therapies, could increase the risk of relapse and resulting permanent disability.

Monotherapy vs Combination Therapy

Both the PREVENT and SakuraSKY studies allowed for (although they did not require) add-on therapy.33,58 Among the patients treated with eculizumab and satralizumab, the outcomes were not superior in those on combination therapy compared with monotherapy.33,58,59 Although benefits of combination over monotherapy were not evident, it may be reasonable to continue a previous therapy until a new therapy is fully active. Subsequently, withdrawal of the previous therapy should be undertaken, given evidence of long-term efficacy with approved monotherapy.153

Payers can support providers in this setting by eliminating any barriers to use of combination therapy in the short term, when providers deem it necessary, despite the lack of evidence that combination therapy is superior to monotherapy in the long term.

Disease Monitoring and Retesting

Although the diagnosis of NMOSD requires both antibody testing and MRI, AQP4-IgG monitoring and repeat MRI outside the setting of acute attacks are not currently indicated. There are currently no universally accepted criteria for defining treatment failure or the need to switch therapy. Patient monitoring is largely based on clinical factors (breakthrough attacks), and there is no established role for regular MRI surveillance in the absence of suspected attacks. There are currently no known cytokine markers that yield reliable prognostic information, although this is an area of active research.31

Early identification of patients who require treatment modification to minimize the risk of relapse and long-term disability is an important unmet need.

Access to and Cost of Treatment

Another challenge in the management of NMOSD is access to and affordability of treatments. This varies considerably across the globe.134 In the United States, populations at highest risk of severe attacks, such as those of African ancestry, are often those with the greatest economic barriers to care.154 When making treatment decisions, it is important to consider local availability of, access to, and cost of individual therapies.93

Payers can also play an important role in consulting with employers in the area of benefit design, access to additional care management services, and providing member education. Reviewing cost shares, out of pockets costs, and deductibles for employees can play an important role in the access to care relating to services needed for patients with NMOSD to ensure that costs are not a barrier. Payers, in coordination with their clients, can often arrange for additional resources such as clinicians to provide further support as well as connect patients to social services who can often find financial support when needed.

Other Considerations

Other treatment-related considerations when making therapy decisions for patients with NMOSD include convenience, such as mode and frequency of administration, safety, and need for monitoring. Patient- and disease-related considerations include likelihood of good adherence,140 individual barriers to treatment (eg, insurance coverage, need to travel to receive treatment), stability of disease, need for monotherapy vs concomitant immunosuppressive therapy, and comorbidities.87

Drug-drug interactions can be an issue, especially with older treatments. For instance, AZA should not be combined with allopurinol or aminosalicylates. Magnesium- or aluminum hydroxide-based antacids and proton pump inhibitors may decrease absorption of MMF or its metabolites. Drugs excreted renally may compete with renal excretion of MMF, increasing the risk of toxicity, and MMF may reduce the action of oral contraceptives. TCZ should only be used with caution when combined with omeprazole, warfarin, statins, cyclosporine, or oral contraceptives, as inhibition of IL-6 may cause increased CYP450 enzyme activity.78 These risks represent an opportunity for both pharmacists and payers to promote patient safety, by verifying the potential for drug-drug interactions.

Given these numerous considerations in selecting therapy for patients with NMOSD, ideally patients and providers would have access to the range of available treatments so that therapy can be individualized as needed. Managed care professionals can help improve NMOSD outcomes by working with providers to ensure evidence-based access to treatment and balance outcomes and burden of therapy, including cost of therapy and burden on the patient.

Conclusions

NMOSD is a rare but debilitating chronic neurological disease characterized by astrocyte dysfunction and loss that leads to secondary demyelination and neurodegeneration. Although the presence of AQP4-IgGs play a central role in the pathogenesis of this disease, it is possible to meet consensus NMOSD criteria without detectable AQP4-IgGs. A minority of patients who have an NMOSD clinical phenotype may be positive for serum MOG-IgG instead of AQP4-IgG. NMOSD typically results in repeated acute attacks, with each attack conferring a signficant risk of long-term disability and/or death. The primary goal of the management of NMOSD is prevention of acute attacks to minimize irreversible impairment and disability. Recent improvement in understanding of the pathogenesis of NMOSD has led to the development, evaluation, and regulatory approval of several mAbs that effectively reduce the risk of acute attacks, but these agents are uniquely or primarily effective in AQP4-IgG–positive disease. In addition, treated patients may still experience attacks. Both direct and indirect costs of NMOSD are high, and medical insurance coverage does not provide adequate support in many patients.

There remain significant unanswered questions about the optimal management of NMOSD. There is scant evidence to guide selection among available treatments, and the long-term effects of available therapeutic strategies remain largely unknown. Currently, no head-to-head trials have been conducted on approved agents. A large knowledge gap exists regarding optimal management of AQP4-IgG–seronegative disease, a likely heterogeneous disorder. Despite promising findings with several new mAbs in NMOSD, there are insufficient data to develop treatment selection guidelines for NMOSD.155 Lacking evidence-based guidance, treatment selection for patients with AQP4-IgG–seropositive NMOSD largely depends on comorbidities, infection risks, and current medications, as well as affordability and patient access to therapy.

Real-world studies and patient insights point to numerous challenges across the NMOSD care continuum that can pose barriers to optimal outcomes. In collaboration with neurologists and NMOSD specialists, managed care professionals can play key roles in improving timely, evidence-based treatment and in supporting patients with adherence to NMOSD management plans. By working together, both payers and providers can ensure that patients have timely access to the therapies necessary to minimize the risk of NMOSD attacks that often require hospitalization and may lead to permanent disability. Among the minority of patients for whom approved diseasemodifying drugs targeting underlying pathology are not yet available, access to comprehensive specialized rehabilitation services and supportive care can maximize QoL and promote optimal engagement in social and economic life for both patients and their caregivers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing support under the authors’ guidance was provided by Alison Palkhivala.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wingerchuk DM, Lucchinetti CF. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(7):631-9. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1904655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carnero Contentti E, Correale J. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: From pathophysiology to therapeutic strategies. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18(1):208. doi:10.1186/s12974-021-02249-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redenbaugh V, Flanagan EP. Monoclonal antibody therapies beyond complement for NMOSD and MOGAD. Neurotherapeutics. 2022;19(3):808-22. doi:10.1007/s13311-022-01206-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hor JY, Asgari N, Nakashima I, et al. Epidemiology of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and its prevalence and incidence worldwide. Front Neurol. 2020;11:501. doi:10.3389/FNEUR.2020.00501/PDF [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holroyd KB, Manzano GS, Levy M. Update on neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2020;31(6):462-8. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flanagan EP, Cabre P, Weinshenker BG, et al. Epidemiology of aquaporin-4 autoimmunity and neuromyelitis optica spectrum. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(5):775-83. doi:10.1002/ana.24617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarius S, Ruprecht K, Kleiter I, et al. MOG-IgG in NMO and related disorders: A multicenter study of 50 patients. Part 2: Epidemiology, clinical presentation, radiological and laboratory features, treatment responses, and long-term outcome. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13(1):280. doi:10.1186/s12974-016-0718-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Misu T, Fujihara K, Nakashima I, et al. Intractable hiccup and nausea with periaqueductal lesions in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2005;65(9):1479-82. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000183151.19351.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKeon A, Lennon VA, Lotze T, et al. CNS aquaporin-4 autoimmunity in children. Neurology. 2008;71(2):93-100. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000314832.24682.c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huda S, Whittam D, Bhojak M, et al. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19(2):169-76. doi:10.7861/CLINMEDICINE.19-2-169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lana-Peixoto MA, Talim N. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and Anti-MOG syndromes. Biomedicines. 2019;7(2):42. doi:10.3390/biomedicines7020042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Exuzides A, Sheinson D, Sidiropoulos P, et al. Burden and cost of comorbidities in patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. J Neurol Sci. 2021;427:117530. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2021.117530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wingerchuk DM, Hogancamp WF, O’Brien PC, et al. The clinical course of neuromyelitis optica (Devic’s syndrome). Neurology. 1999;53(5):1107-14. doi:10.1212/wnl.53.5.1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eaneff S, Wang V, Hanger M, et al. Patient perspectives on neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: Data from the PatientsLikeMe online community. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;17:116-22. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2017.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kleiter I, Gahlen A, Borisow N, et al. Neuromyelitis optica: Evaluation of 871 attacks and 1,153 treatment courses. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(2):206-16. doi:10.1002/ANA.24554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]