Abstract

Background

In the US, over half of all cervical and lumbar arthrodesis spine surgeries are for people ≥60 years of age. The extent to which adverse outcomes vary by social (eg, disadvantaged neighborhoods) and demographic factors have been scarcely investigated in spine surgery. We investigated the association of social, demographic, and clinical factors with complications, 30-day readmission, and 30-day mortality in older Veterans undergoing elective spine surgery.

Methods

Veterans (N=5,277) aged ≥65 years who underwent inpatient elective spine surgery for degenerative disease in the Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program (VASQIP) comprised our retrospective cohort. VASQIP (2013–2019) data were merged with other Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and Medicare administrative data. Multivariable logistic regression models were estimated to assess the associations of social (rurality, Area Deprivation Index [ADI]) and clinical (frailty, comorbidity) factors with complications, 30-day readmission, and 30-day mortality. The ADI is a neighborhood-level socioeconomic disadvantage ranking using 17 variables (eg, housing quality). We defined highly disadvantaged as ADI>85.

Results

Veterans aged 65–74 years comprised 82.7%; 77.9% identified as White, 15.1% as Black, and 7.0% as another race; and 97.1% were male. Over one-third (38.9%) lived in rural areas and 12.3% lived in highly disadvantaged neighborhoods. Readmission and mortality were 10.0% and 0.6%, respectively, and 6.0% experienced complications. Rurality and ADI>85 were not associated with complications, 30-day readmission, or 30-day mortality. Frailty, comorbidity, class-3 obesity, and operative stress were associated with adverse outcomes.

Conclusions

Social (rurality, ADI>85) and demographic variables were not associated with complication, 30-day readmission, or 30-day mortality in older Veterans following elective spine surgery. While clinical factors (frailty, co-morbidity, class-3 obesity, and operative stress score) were associated with adverse outcomes, Veterans in this study did not experience disparities in medical outcomes due to social vulnerability. Untangling mechanisms connecting social and clinical factors may improve outcomes.

Keywords: Area Deprivation Index, Older adult, Socioeconomic disadvantage, Postoperative Outcomes, Social Determinants of Health, Social Risk Factors, Veteran

Background

Nearly one-third of older Americans suffer from degenerative spine disease (DSD) [1]. Spinal surgery to relieve pain and preserve independence among older adults with DSD is increasing [2,3]. In the US, over half (52.4%) of cervical and 59.8% of lumbar arthrodesis spine surgeries are for people 60 years of age and older [4]. Patients ≥65 years of age had the largest increase in lumbar spine fusion surgeries (1998–2008) [5,6], and are expected to increase further with the aging of the population. One in 4 Americans will be ≥65 by 2060 [6,7]. Older adults are vulnerable for adverse postoperative outcomes, with unique risks related to clinical and social risk factors [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]]. Older adult clinical risks such as multimorbidity are well-described [10,[14], [15], [16]]. However, literature addressing social risk factors is scarce [[17], [18], [19], [20]]. Social risk factors influence a person’s health and vary by both demographic (eg, age, race. sex) and social (eg, living in highly disadvantaged neighborhoods, rurality) factors [17,18].

Social risk factors, or social determinants of health (SDoH), affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes [21]. Economic stability, quality of, and access to, education and healthcare, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community contexts are the pillars of SDoH [21]. Social risk factors may contribute to care fragmentation, care that is delivered by different providers in different settings and organizations with poor communication between them [[22], [23], [24]]. Care fragmentation is a problem between primary and specialty care [23] and contributes to adverse postoperative outcomes following non-spine surgery [25]. Further, patient-level context such as low education [17], Black race [26], and advancing age [11] have been associated with adverse outcomes following spine surgery. Understanding the influence of patient and contextual-level socioeconomic factors is imperative to improving postoperative outcomes following spine surgery [27].

Although some research has examined the association of socioeconomic neighborhood disadvantage [[27], [28], [29]] with postoperative outcomes, data are sparse following spine surgery in Veterans [[29], [30], [31]]. Socioeconomic neighborhood disadvantage is often measured using composite measures that integrate multiple socioeconomic neighborhood level factors into one variable summarizing disadvantage, such as the Area Deprivation Index (ADI) [[27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34]].

Understanding the relationship between neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and adverse postoperative outcomes is integral to providing equitable care and mitigating disparities for those undergoing spine surgery [17]. The current study investigated associations between social (rurality, ADI>85), demographic, and clinical factors with postoperative complication, 30-day readmission, and 30-day mortality of Veterans ≥65 years of age who underwent elective spine surgery in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). Our hypothesis was that social (rurality and ADI>85), demographic, and clinical factors would be associated with adverse postoperative outcomes (complication, 30-day readmission, and 30-day mortality) among older Veterans undergoing elective spine surgery.

Methods

Study design, data sources, and record selection

This retrospective cohort study used a national sample of Veterans who underwent inpatient spine surgery within the VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program (VASQIP) registry [35] from 2013 to 2019. The study is reported according to STROBE guidelines [36] and was determined exempt by the VHA Central Institutional Review Board.

VASQIP is a quality assurance activity-derived database containing information on patients who undergo surgery within the VHA. Data for VASQIP is entered by trained surgical quality nurses who use Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA) for data abstraction. Additional data sources which were linked to VASQIP data include: (1) the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), for demographic information (i.e. age, sex, race) and patient death dates; (2) the VHA Program Integrity Tool (PIT) and VA fee-based domain, used to measure care delivered by non-VA providers reimbursed by the VHA; (3) the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Systems (CMS) data on Medicare enrollment and fee-for-service claims among VHA beneficiaries; (4) the VA Planning Systems Support Group (PSSG) provided geocoded patient addresses, including census tract for assigning rurality and census block group for assigning ADI. For those initially missing ADI values, we first obtained the closest census tract to their home address from U.S. Census Bureau’s Gazetteer Files using longitudinal and latitudinal coordinates. From this, we were able to derive approximate ADI values, matching the census track with the national ADI file. In the end, only 9 cases were excluded for missing ADI. The cohort was restricted to ≥65 years old to provide comprehensive data on care fragmentation using Medicare data and meet study objectives.

Study population

Veterans in VASQIP aged 65 years of age and older undergoing elective spine surgery (as identified by Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) consistent with surgery for DSD (N=5,277) were included. We excluded Veterans whose CPT® and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 or 10 codes indicated spine surgery for diagnoses other than DSD (cancer [tumor/biopsy], fracture, infection, or other surgeries). Supplement 1 details the included CPT® codes and associated N (%) of each code. To further define the cohort, Veterans whose case status was emergent or urgent were excluded. Veterans without prior VHA use, not enrolled in fee-based Medicare, enrolled in a Medicare managed care plan, or missing key clinical variables were excluded (Figure).

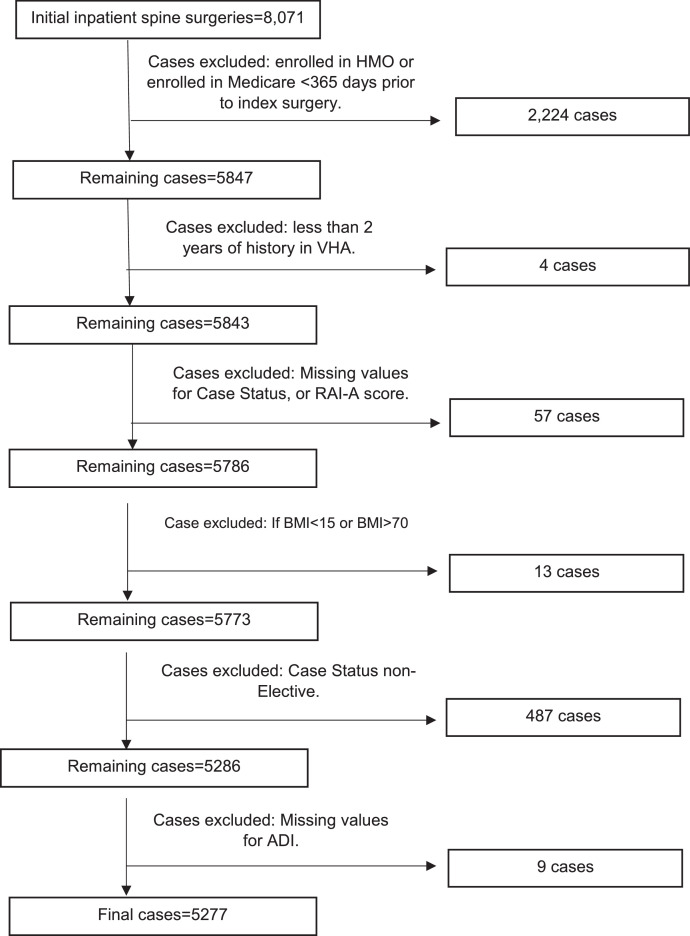

Figure.

Cases included and excluded with corresponding numbers, represented in a flow chart. RAI-A, Risk Analysis Index.

Variables of interest

Veteran characteristics and social risk factors

Veteran characteristics included age, race, assigned sex in VASQIP. Social risk factors included rural residence and ADI [33]. Rurality was defined as rural or urban according to the VA Office of Management and Budget definition using Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes (RUCA) of patient’s home address. The ADI is a composite measure of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage that combines 17 social indicators including income, education, employment, and housing (eg, homes without complete plumbing and homes without a vehicle) at the National Census Block Group level. ADI is a 1-100 percentile score with a high percentile indicating high disadvantage (low prosperity) [[32], [33], [34],37]. Because ADI includes neighborhood-level income, individual-level income was not included in the logistic regression models. For this study, an ADI score of >85% was defined as highly disadvantaged [32].

Clinical risk factors

Patient clinical risk factors included the Risk Analysis Index of Frailty (RAI-A) [38], the Gagne Comorbidity Score [39], smoking status, body mass index (BMI), Operative Stress Score (OSS) [40,41], care fragmentation, Preoperative Acute Serious Conditions (PASC) [42], and surgery location and type grouping using CPT® codes.

The RAI-A is a validated measure of frailty using preoperative variables from VASQIP to render a score from 0-81 with higher scores indicating greater frailty. Unlike many frailty measures, the RAI-A has been validated in the surgical population and is suitable for large retrospective data analysis exploring the association of frailty with postoperative outcomes [13,43]. For descriptive analysis, frailty was categorized based on the RAI-A score as follows: Robust (≤20); Normal (21–29); Frail (30–39); and Very Frail (≥40) [44]. For bivariable and multivariate analysis, the RAI-A was operationalized as a continuous variable.

The Gagne Comorbidity Score quantifies the impact of comorbidities on short-term and long-term mortality on a scale from -2 to 26 [39]. We derived the score by using diagnoses from CDW and CMS claims data during the 12 months prior to surgery.

Positive smoking status, height and weight were obtained from VASQIP. Body mass index (BMI) was categorized by underweight, normal weight, overweight, class 1 obesity, class 2 obesity, and class 3 obesity. OSS estimates surgery induced physiological stress based on CPT® codes by assigning a score of 1 (low stress) to 5 (high stress). PASC uses preoperative conditions of ventilator use, pneumonia, coma, sepsis, large blood transfusions, or renal failure within the prior 30 days of surgery. Care fragmentation was defined as receiving any non-VA care during the 12 months prior to surgical admission as determined by VHA Fee-based care and CMS claims data. CPT codes were grouped to account for spinal region and surgery type. Four CPT code groups were formed: Group 1 - anterior cervical or thoracic; Group 2 - posterior cervical or thoracic; Group 3 - lumbar decompression; Group 4 - lumbar fusion (Supplement 1). Technical definitions of each variable are provided in Supplement 2.

Outcome variables

The outcomes of interest were at least one complication within 30 days of surgery, death within 30 days of surgery, and readmission to acute care within 30 days of live discharge. Complications were identified using VASQIP variables including indicators of postoperative bleeding, infection (superficial, deep, organ space, urinary, colitis, sepsis), deep vein thrombosis, wound dehiscence, and pneumonia (Supplement 3). Postoperative mortality was calculated as 30 days from the index surgery date, including deaths after discharge. Readmission was defined as a subsequent admission to a VHA or non-VHA acute care facility within 30-days of live discharge from the index surgery hospitalization. Additional exclusions for readmission outcome variable included: discharge against medical advice; died within 30-days of discharge without a readmission or observation stay; transferred to a non-VA hospital or hospice; death at hospitalization.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean/standard deviation and N/percent) were calculated for demographic, social, and clinical variables. Bivariable analysis evaluated relationships between each patient risk factor and the outcomes of 30-day complication, 30-day mortality and 30-day readmission, followed by multivariable logistic regression models to assess the relationships between demographic, clinical and social variables with outcomes. Social factors (rurality, ADI>85) and race were included in all multivariable models for hypothesis testing; clinical risk adjustment variables were included only when significantly related to the outcome. Correlation between patient risk factors was assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient for continuous variables (eg, age, RAI-A score) and Cramer’s V for categorical variables (eg, race). We also conducted sensitivity analyses using propensity matching in which each Veteran with ADI>85 was matched to 3 Veterans with ADI≤85. Propensity scores were estimated by logistic regression using patient characteristics listed in Table 1 to calculate the predicted probability of residing in a census block group with ADI>85. A greedy matching algorithm using a caliper of 0.50 standard deviation was used to match all 656 veterans with ADI>85 to 1938 veterans with ADI. We assessed covariate balance using the criterion that standardized differences in all patient covariates are 0.10 after matching (Supplemental 4, 5). Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4. All p-values were considered significant at the p<.05 level and all confidence intervals (CI) are reported at the 95% level.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Veteran cohort and for Veterans with ADI ≤85 and those with an ADI>85

| Full Cohort | ADI ≤85 | ADI<85 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=5,277 |

n=4,621 (87.6%) |

n=656 (12.3%) |

|

| Variable | Mean (SD) or N (%) | Mean (SD) or N (%) | Mean (SD) or N (%) |

| Age | |||

| 65–74 | 4,362 (82.7) | 3,810 (82.5) | 552 (84.2) |

| 75–84 | 847 (16.1) | 748 (16.19) | 99 (15.1) |

| 85+ | 68 (1.3) | 63 (1.4) | 5 (0.8) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 152 (2.9) | 136 (2.9) | 16 (2.4) |

| Male | 5,125 (97.1) | 4,485 (97.1) | 640 (97.6) |

| Race | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 4,110 (77.9) | 3,663 (79.3) | 447 (68.1) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 796 (15.1) | 627 (13.6) | 169 (25.8) |

| Other, non-White, non-Hispanic | 371 (7.0) | 331 (7.2) | 40 (6.1) |

| Rurality | |||

| Rural/Highly rural | 2,050 (38.9) | 1,716 (37.1) | 322 (50.9) |

| Urban | 3,227 (61.2) | 2,905 (62.9) | 322 (49.1) |

| Frailty (RAI-A score) | |||

| Robust (≤20) | 71 (1.4) | 65 (1.4) | 6 (0.9) |

| Normal (21-29) | 4,271 (80.9) | 3,740 (80.9) | 531 (81.0) |

| Frail (30–39) | 854 (16.2) | 748 (16.2) | 106 (16.2) |

| Very frail (≥40) | 81 (1.5) | 68 (1.5) | 13 (2.0) |

| Comorbidity (Gagne score) | 1.88 (2.4) | 1.88 (2.36) | 1.93 (2.3) |

| Positive smoking status | 1,053 (20.0) | 905 (19.6) | 148 (22.6) |

| BMI | |||

| Underweight | 28 (0.5) | 22 (0.5) | 6 (0.9) |

| Normal weight | 887 (16.8) | 754 (16.3) | 133 (20.3) |

| Overweight | 2,016 (38.2) | 1,797 (38.9) | 219 (33.3) |

| Class 1 obesity | 1,531 (29.0) | 1,337 (28.9) | 194 (29.6) |

| Class 2 obesity | 627 (11.9) | 545 (11.8) | 82 (12.5) |

| Class 3 obesity | 188 (3.6) | 166 (3.6) | 22 (3.4) |

| OSS | |||

| 1 or 2 | 1,809 (34.3) | 1,606 (34.8) | 203 (31.0) |

| 3 | 3,468 (65.7) | 3,015 (65.3) | 453 (69.1) |

| Care fragmentation (<100%) | 2,108 (38.9) | 1,838 (39.8) | 270 (41.2) |

| PASC | 8 (0.2) | 8 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

| CPT code groupings | |||

| Group 1 | 630 (11.8) | 531 (11.5) | 99 (15.1) |

| Group 2 | 1,084 (20.5) | 949 (20.5) | 135 (20.6) |

| Group 3 | 2,415 (45.8) | 2,143 (46.4) | 272 (41.5) |

| Group 4 | 1,148 (21.8) | 998 (21.6) | 150 (22.9) |

| Complication | 314 (6.0) | 282 (6.1) | 32 (4.9) |

| 30-d readmission | 511 (10.0) | 446 (10.0) | 65 (10.2) |

| 30-d mortality | 31 (0.6) | 25 (0.5) | 6 (0.9) |

ADI, area deprivation index; BMI, body mass index; BMI classification: underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight 18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), class 1 obesity (30.0–34.9 kg/m2,) class 2 obesity (35–39.9 kg/m2), class 3 obesity (≥ 40.0 kg/m2); Bold = p<.05; CPT Group 1, anterior cervical/thoracic fusion; CPT Group 2, posterior cervical/thoracic fusion; CPT Group 3, lumbar decompression, CPT Group 4, lumbar fusion.

Results

Our cohort of Veterans undergoing elective spine surgery for DSD (N=5,277) (Table 1) were 97.1% male, with 15.1% Black Non-Hispanic, 77.9% White Non-Hispanic, and 7.0% from other racial and ethnic groups. Most Veterans were aged 65–74 (82.7%), with 16.1% aged 75–84 and those ≥85 only comprising 1.3%. Those who resided in highly disadvantaged neighborhoods (ADI>85%) totaled 12.3% of the cohort and 38.9% lived in rural or highly rural areas. Of those living in highly disadvantaged neighborhoods, 50.9% resided in rural areas and 25.8% were Black.

Overall, 16.2% of the cohort was frail, with an additional 1.5% being very frail (RAI-A). The mean comorbidity (Gagne) score was 1.88 (SD=2.4) and 20% had a positive smoking status. Only 16.8% were normal weight with 0.5% underweight, 38.2% overweight, 29.0% class 1 obesity, 11.9% class 2 obesity, and 3.6% class 3 obesity. Over one-third (38.9%) of Veterans received at least one day of care outside the VHA system. The average PASC score was 8 (SD=.2) and 65.7% had an OSS of 3 (moderate stress surgery).

Ten CPT® codes comprised 82.2% of cohort surgeries. Of those ten, code 63047 (lumbar laminectomy, facetectomy, and/or foraminotomy) accounted for 22.4%; 22551 (cervical arthrodesis) 9.8%; 22612 (lumbar arthrodesis) 8.1%; 63,030 (lumbar laminectomy) 7.5%; and 22,630 lumbar arthrodesis 7.3% (Table 2). CPT group 1 (anterior cervical/thoracic) comprised 11.8%, group 2 (posterior cervical/thoracic) 20.5%, group 3 (lumbar decompression) 45.8% and group 4 (lumbar fusion) 21.8% of the cohort.

Table 2.

The top 10 CPT codes of the cohort ranked from most to least. The top 10 codes represent 82.2% of the total cohort (5,277).

| N (%) | CPT code | Code type |

|---|---|---|

| 1,180 (22.4) | 63,047 | Lumbar decompression |

| 516 (9.8) | 22,551 | Cervical arthrodesis |

| 426 (8.1) | 22,612 | Lumbar arthrodesis |

| 397 (7.5) | 63,030 | Lumbar decompression |

| 384 (7.3) | 22,630 | Lumbar arthrodesis |

| 349 (6.6) | 63,005 | Lumbar decompression |

| 319 (6.1) | 63,015 | Cervical decompression |

| 299 (5.7) | 63,017 | Lumbar decompression |

| 275 (5.2) | 22,600 | Cervical arthrodesis |

| 191 (3.6) | 22,633 | Lumbar arthrodesis |

| 4,336 (82.2) |

Complications occurred in 6.0% of patients (n=314) and mortality within 30 days in 0.59% of patients (n=31). The readmission rate was 10.0% (n=511), in 5,117 Veterans who did not meet further readmission exclusion criteria.

Predictors of complications

Social risk factors (ADI>85 and rurality) and race were not significantly related to complication development in either bivariable (Table 3) or multivariable (Table 4) analyses.

Table 3.

Bivariable analysis of social, demographic characteristics, and clinical variables associations with the adverse outcomes of complication, 30-day readmission, and 30-day mortality.

| Complication | 30-day readmission | 30-day mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI), p value* | OR (95% CI), p value | OR (95% CI), p value | |

| Social factors | |||

| ADI >85% (ref: ≤85%) | 0.79 (0.54–1.15), .22 | 1.03 (0.78–1.36), .82 | 1.70 (0.69–4.15), .25 |

| Residence (ref: Urban) | |||

| Rural/Highly rural | 0.85 (0.67–1.08), .19 | 0.91 (0.75–1.09), .31 | 0.99 (0.48–2.05), .99 |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (Ref: ≥85 years) | |||

| 65–74 | 2.00 (0.49–8.20), .34 | 1.10 (0.47–2.57), .82 | NA |

| 75–84 | 2.65 (0.64–11.08), .18 | 1.39 (0.58–3.29), .46 | NA |

| Race (Ref: White non-Hispanic) | |||

| Black non-Hispanic | 1.30 (0.97–1.74), .08 | 0.95 (0.73–1.24), .71 | 1.29 (0.53–3.17), .57 |

| Others non-White, non-Black | 0.73 (0.44–1.23), .23 | 0.85 (0.59–1.24), .41 | 0.46 (0.06–3.41), .45 |

| Clinical Factors | |||

| Frailty (RAI-A score) | 1.06 (1.03–1.08), <.001 | 1.05 (1.03 –1.07), <.001 | 1.05 (0.99–1.13), .12 |

| Co-morbidity (Gagne score) | 1.10 (1.06–1.15), <.001 | 1.08 (1.04 –1.12), <.001 | 1.15 (1.03–1.30), .02 |

| Tobacco use (ref: None) | 0.94 (0.71–1.26), .70 | 0.88 (0.70–1.11), .29 | 1.40 (0.62–3.14),.46 |

| BMI (Ref: normal weight) | |||

| Underweight | 0.58 (0.08–4.37), .60 | 0.33 (0.05–2.49), .28 | 5.44 (0.63–46.75), .12 |

| Overweight | 0.84 (0.60–1.18), .31 | 0.80 (0.62–1.05), .11 | 0.88 (0.33–2.35), .80 |

| Class 1 Obesity | 1.05 (0.75–1.49), .77 | 0.92 (0.70–1.21), .56 | 0.48 (0.15–1.58), .23 |

| Class 2 Obesity | 1.13 (0.74–1.72), .57 | 1.13 (0.82–1.58), .44 | 1.42 (0.45–4.42), .55 |

| Class 3 Obesity | 1.87 (1.09–3.22), .02 | 1.30 (0.80–2.10), .29 | 0.79 (0.09–6.56), .82 |

| OSS (Ref:1 or 2) | 1.34 (1.04–1.73), .02 | 1.39 (1.14–1.70), .002 | 1.50 (0.67–3.37), .32 |

| Care Fragmentation (Ref:100%) | 1.08 (0.86–1.36), .51 | 1.19 (0.99–1.43), .07 | 1.24 (0.61–2.52), .55 |

| PASC (Ref: 0) | 2.26 (0.28 –18.45), .45 | NA | NA |

| CPT Codes (ref: Group 1) | |||

| Group 2 | 1.42 (0.85–2.11), .09 | 1.16 (0.85–1.60), .35 | 0.58 (0.20–1.66, .31 |

| Group 3 | 0.88 (0.60–1.28), .49 | 0.75 (0.55–1.01), .06 | 0.40 (0.16–1.05), .06 |

| Group 4 | 0.95 (0.62–1.44), .80 | 1.11 (0.81–1.53), .50 | 0.47 (0.16–1.40), .17 |

ADI, area deprivation index; BMI classification: underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight 18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), class 1 obesity (30.0–34.9 kg/m2,) class 2 obesity (35-39.9 kg/m2), class 3 obesity (≥ 40.0 kg/m2);CPT Group 1, anterior cervical/thoracic fusion; Bold = p<0.05; CPT Code Group 2, posterior cervical/thoracic fusion; CPT Group 3, lumbar decompression, CPT Group 4, lumbar fusion; NA, not able to analyze due to small variable number; OR, Odds Ratio

*Bold = p<.05

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of social and clinical variables associations with the adverse outcomes of complication, 30-day readmission, and 30-day mortality.

| Complication | 30-day readmission | 30-day mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI), p value* | aOR (95% CI), p value | aOR (95% CI), p value | |

| Social factors | |||

| ADI >85% (Ref: ≤85%) | 0.76 (0.52–1.11), .16 | 1.04 (0.79–1.38), .77 | 1.65 (0.66–4.12), .28 |

| Residence (Ref: Urban) | |||

| Rural/Highly rural | 0.90 (0.70–1.15), .38 | 0.90 (0.74 –1.09), .28 | 1.02 (0.48–2.16), .96 |

| Race (Ref: White non-Hispanic) | |||

| Black non-Hispanic | 1.25 (0.92–1.70), .15 | 0.88 (0.67–1.15), .35 | 1.15 (0.45–2.93), .77 |

| Others non-White, non-Black | 0.73 (0.44–1.23), .24 | 0.84 (0.57–1.23), .36 | 0.46 (0.06–3.40), .44 |

| Clinical factors | |||

| Frailty (RAI-A score) | 1.04 (1.02–1.07), .001 | 1.03 (1.01–1.06), .002 | NS |

| Co-morbidity (Gagne score) | 1.06 (1.02–1.11), .01 | 1.06 (1.02–1.10), .006 | 1.15 (1.3–1.30), .02 |

| BMI (Ref: normal weight) | |||

| Underweight | 0.55 (0.07–3.96),.53 | NS | NS |

| Overweight | 0.92 (0.65–1.29),.62 | NS | NS |

| Class 1 obesity | 1.16 (0.82–1.62),.40 | NS | NS |

| Class 2 obesity | 1.24 (0.81–1.89),.32 | NS | NS |

| Class 3 obesity | 2.10 (1.16–3.47), .01 | NS | NS |

| OSS (Ref: 1 or 2) | 1.34 (1.04–1.73), .02 | 1.38 (1.13–1.69), .002 | NS |

ADI, area deprivation index; BMI classification: underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight 18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), class 1 obesity (30.0–34.9 kg/m2,) class 2 obesity (35–39.9 kg/m2), class 3 obesity (≥ 40.0 kg/m2); Bold = p<.05; NS, variable not included in this model because it was not statistically significant in the bivariable model; OR, Odds Ratio

*Bold = p<.05

The RAI-A Frailty score (OR=1.06; 95% CI:1.03–1.08; p<.001), Gagne comorbidity score (OR=1.10; 95% CI: 1.06-1.15; p<.001), class 3 obesity (OR=1.87; 95% CI: 1.09-3.22; p=.02) and OSS (OR=1.34; 95% CI: 1.04–1.73; p=.02) were associated with post-surgical complications in bivariable analyses (Table 3). These associations remained in multivariable analysis: frailty (aOR=1.04; 95% CI: 1.02–1.07; p=.001), comorbidity (aOR=1.06; 95% CI: 1.02–1.11; p=.01), class 3 obesity (aOR=2.10; 95% CI: 1.16–3.47; p=0.01) and OSS (aOR=1.34; 95% CI: 1.04–1.73; p=.02) (Table 4). Tobacco use, BMI (underweight, overweight, class 1 and 2 obesity, care fragmentation, PASC and CPT code groups were not associated with complications in either bivariable (Table 3) or multivariable (Table 4) analysis.

Predictors of 30-day readmission

Social risk factors (ADI>85 and rurality) and race were not significantly related to 30-day readmission in either bivariable (Table 3) or multivariable (Table 4) analyses. In bivariable analysis (Table 3), frailty (OR=1.05; 95% CI:1.03-1.07; p<.001), comorbidity (OR=1.08; 95% CI: 1.04–1.12; p<.001), and OSS (OR=1.39; 95% CI: 1.14–1.70; p=.002) were associated with higher odds of 30-day readmission. In multivariable analysis (Table 4), these associations remained for frailty (aOR=1.03; 95% CI: 1.02–1.06; p=.002), comorbidity (aOR=1.06; 95% CI: 1.02–1.10; p=.006), and OSS (aOR=1.38; 95% CI: 1.13–1.69; p=.002). Tobacco use, BMI (underweight, overweight, class 1, 2, and 3 obesity, care fragmentation, PASC, and CPT code groups were not associated with readmission in either bivariable (Table 3) or multivariable (Table 4) analyses.

Predictors of 30-day mortality

Social risk factors (ADI>85 and rurality) and race were not significantly related to 30-day readmission in either bivariable (Table 3) or multivariable (Table 4) analyses.

Comorbidity (OR=1.15; 95% CI: 1.03–1.30; p=.02) was associated with 30-day mortality in bivariable analysis (Table 3) and remained significant in multivariable analysis (Table 4; aOR=1.15; 95% CI: 1.03–1.30; p=.02). Frailty, tobacco use, BMI (underweight, overweight, class 1,2, and 3 obesity, OSS, care fragmentation, PASC, and CPT code groups were not associated with readmission in either bivariable (Table 3) or multivariable (Table 4) analyses.

Sensitivity analyses

Supplemental 4 shows standardized differences in patient characteristics before and after matching, with all characteristics showing excellent balance after matching. Relative outcomes for patients with ADI>85 versus ADI≤85 were consistent with our primary results (Supplemental 5). These analyses were repeated to propensity match Veterans residing in rural or highly rural areas to urban veterans (not shown), with similar results to our primary analysis.

Discussion

This retrospective study hypothesized that social, demographic, and clinical factors would be associated with adverse outcomes (complication, 30-day readmission, and 30-day mortality) among older Veterans undergoing elective spine surgery for DSD. We found that high ADI, rurality, age, and race were not statistically associated with complication, 30-day readmission, or 30-day mortality in our older Veteran elective spine surgery cohort. The clinical factors of positive smoking status, BMI underweight, overweight, class 1 and 2 obesities, care fragmentation, PASC, and spine surgery location and type were also not associated with adverse outcomes. Frailty, co-morbidity, and operative stress score were associated with most adverse outcomes in both bivariable and multivariable analysis. Class 3 obesity was associated with complications in both bivariable and multivariable analysis.

We found no disparity in medical outcomes for older Veterans living in high ADI neighborhoods. This finding supports the efforts of the VHA to provide health care irrespective of social disadvantage or living situation and may be a function of access to primary care unique to the VHA system. To support access across all Veterans receiving VHA healthcare, the VHA provides a variety of resources including Care in the Community. Legislation to improve access to care includes The Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act of 2014 (“Choice Act,” Public Law No. 113-146) and the 2018 VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act (“MISSION Act,” Public Law No. 115-182) [45]. Notably, only 58.8% of high ADI (and 60.2% of ADI≤85) Veterans in our cohort received 100% of their care in the VHA. This suggests that even Veterans residing in disadvantaged neighborhoods can access care outside VHA, although we cannot assess whether this access is sufficient. Untangling the impact of expanded private sector care access on Veterans’ health and outcomes, including any reductions in disparities, warrants further investigation.

Our findings of no association between high ADI and adverse outcomes in our older Veteran (receiving VHA health care) cohort contrasts with many authors investigating private sector elective spine surgery cohorts. These authors [19,20, [46], [47], [48], [49]] have found high ADI was associated with adverse outcomes (increased length of stay, complication, readmission, mortality). Similarly, Veterans living in rural areas did not have an increased risk of adverse outcomes following spine surgery. In our cohort, over 50% of those who lived in neighborhoods of high socioeconomic disadvantage, also lived in rural or highly rural areas. This is in contrast to private sector investigations of total knee replacement, in which only 5-10% of high ADI patients lived in rural areas [50]. Our findings are interesting given that rural Veterans in the VHA are prescribed more opioids [51] and have increased multimorbidity [52], factors that increase risk of postsurgical outcomes. The significance of the lived environment, spine surgery, and patient outcomes are not clear[17]. Future research is warranted to investigate what protective measures are occurring so that these can serve as potential interventions in other settings.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis [26] as well as a Medicare claims study of older adults report Black patients were significantly more likely than White patients to experience mortality, complication, or readmission [53]. Importantly, in contrast to previous spine surgery literature [31,54], we found Black race was not predictive of adverse outcomes. This may be attributed to a yet unanswered health care benefit within the VHA that is addressing racial inequities. Further investigation is warranted.

Consistent with current literature, our findings support frailty, co-morbidity, and class 3 obesity as clinical risks for adverse postoperative outcomes. [10,[55], [56], [57], [58]] While these clinical factors have been established as risk factors for adverse postoperative outcomes among patients in the private sector [10,13,28,55,57,58], this study adds to our understanding of the associations of frailty, co-morbidity, class 3 obesity, and operative stress with adverse outcomes following elective spine surgery in older Veterans served by the VHA. Additionally, frailty, comorbidity, and neighborhood disadvantage may be intertwined [59] with longitudinal evidence suggesting a lack of wealth and neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage leads to frailty [60]. This brings to light the question of how social determinants of health, including neighborhood disadvantage and clinical risk, are intertwined and how to understand the impact of each so that appropriate responses can be developed. Toward that end, preoperative collection of routine social risk factor data for research, resource allocation, and interventions have been suggested by other authors [17,19,47,61]. For example, a patient who lives in a socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhood with pain and immobility from DSD may need higher levels of coordinated social and healthcare resources to mitigate potential adverse outcomes associated with spine surgery.

Our study has important limitations. Data was obtained from administrative data sets. The number of levels performed at surgery was not a reliable variable, thus limiting our ability to report further surgical complexity. Findings may not generalize to younger patients and those in non-VHA settings. As a retrospective study, causal inferences are limited. The relationships between various social risk factors, independently and compounding, are complex and require further investigation to understand the possible interactions, causal structures, and potentially unrecognized confounders. Patient-level demographics may have contributed, and our study may have lacked power to detect social risk factor associations.

Conclusion

Social (rurality, ADI>85) and demographic variables were not associated with complication, 30-day readmission, or 30-day mortality in older Veterans following elective spine surgery. A lack of association of social and demographic variables contrasts with recent private sector findings. Clinical factors (frailty, co-morbidity, class 3 obesity, OSS) were associated with adverse outcomes. While Veterans in this study did not experience medical outcome disparity, clinical factors are associated with adverse outcomes. Untangling mechanisms connecting social and clinical factors may improve outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the VHA Office of Research and Development (HSR&D I01HX003095/IIR 19-414). The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the United States government.

Data availability statement

These data cannot be disclosed upon request, as they are confidential and privileged under the provisions of 38 U.S.C. 5705 and internal VA policy.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors disclose other grant funding from the NIH, AHRQ, the Heinz Endowments, and the US Department of Veterans Affairs outside the scope of this work. Dr. Hall discloses a consulting relationship with FutureAssure, LLC. Dr. Strayer discloses royalties from Wolters Kluwer, Thieme Publishers, and Taylor & Francis Publishers.

Footnotes

FDA device/drug status: Not applicable.

Author disclosures: ALS: Royalties: Wolters Kluwer (B); Thieme (A), Taylor & Francis (A). YG: Grant: VA HSR&D (D). MAJ: Grant: VA HSR&D (E). HD: Grant: VA HSR&D (D); Research Support: US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Rural Health (F). CAJ: VA HSR&D (E). SS: Grant: VA HSR&D (B), NIH/NCATS (D), AHRQ (C). LRMH: Grant: VA HSR&D (A), NIH (D), Department of Veterans Affairs (F), The Heinz Endowments (D). PKS: Grant: Veterans Health Administration (F); Trips/travel: National Institutes of Health (A); Scientific Advisory Board: NCATS Advisory Council of NIH (A); Endowments: Dielmann Chair of Surgery Endowment, Texas Health Science Center (C); Grants: NIH (F). GW: Nothing to disclose. DEH: Nothing to disclose. MVS: Grant: VA HSR&D (F). KEH: Grant: VA HSR&D (D).

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.xnsj.2025.100611.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Parenteau C.S., Lau E.C., Campbell I.C., Courtney A. Prevalence of spine degeneration diagnosis by type, age, gender, and obesity using Medicare data. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):5389. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84724-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferreira M.L., de Luca K. Spinal pain and its impact on older people. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatolol. 2017;31(2):192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rezaii P.G., Cole M.W., Clark S.C., et al. Lumbar spine surgery reduces postoperative opioid use in the veteran population. J Spine Surg. 2022;8(4):426–435. doi: 10.21037/jss-22-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bydon M., Sardar Z.M., Michalopoulos G.D., et al. Representativeness of the American Spine Registry: a comparison of patient characteristics with the National Inpatient Sample. J Neurosurg Spine. 2023;39(2):228–237. doi: 10.3171/2023.3.Spine221264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajaee S.S., Bae H.W., Kanim L.E., Delamarter RB. Spinal fusion in the United States: analysis of trends from 1998 to 2008. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37(1):67–76. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31820cccfb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh R., Moore M.L., Hallak H., et al. Recent Trends in Medicare Utilization and Reimbursement for Lumbar Fusion Procedures: 2000-2019. World Neurosurg. 2022;165:e191–e1e6. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.05.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vespa J. United States Census Bureau; Washington D.C.: 2018. The U.S. Joins Other Coutnries with large Aging Population.https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2018/03/graying-america.html#:~:text=By%202060%2C%20nearly%20one%20in,add%20a%20half%20million%20centenarians [cited 2023 July 6]; Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strayer A.L., King BJ. Older adults’ experiences living with and having spine surgery for degenerative spine disease. The Gerontologist. 2022 doi: 10.1093/geront/gnac184. Available from10.1093/geront/gnac184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strayer A.L., Kuo W.C., King BJ. In-hospital medical complication in older people after spine surgery: a scoping review. Int J Older People Nurs. 2022 doi: 10.1111/opn.12456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan V., Wilson J.R.F., Ravinsky R., et al. Frailty adversely affects outcomes of patients undergoing spine surgery: a systematic review. Spine J. 2021;21(6):988–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2021.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang H., Lu S., Jiang D., Fei Q. Clinical outcomes of lumbar spinal surgery in patients 80 years or older with lumbar stenosis or spondylolisthesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J. 2020;29(9):2129–2142. doi: 10.1007/s00586-019-06261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buehring B., Barczi S. In: Spine surgery in an aging population, N Brooks and A Strayer. Brooks N.P., Strayer A.L., editors. Thieme Publishers; New York: 2019. Assessing the aging patient; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowers C.A., Varela S., Conlon M., et al. Comparison of the risk analysis index and the modified 5-factor frailty index in predicting 30-day morbidity and mortality after spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2023;39(1):136–145. doi: 10.3171/2023.2.Spine221019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernstein D.N., Thirukumaran C., Saleh A., Molinari R.W., Mesfin A. Complications and Readmission After Cervical Spine Surgery in Elderly Patients: An Analysis of 1786 Patients. World Neurosurg. 2017;103:859. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.04.109. -68.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saleh A., Thirukumaran C., Mesfin A., Molinari RW. Complications and readmission after lumbar spine surgery in elderly patients: an analysis of 2,320 patients. Spine J. 2017;17(8):1106–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zileli M., Dursun E. How to improve outcomes of spine surgery in geriatric patients. World Neurosurg. 2020;140:519–526. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reyes S.G., Bajaj P.M., Alvandi B.A., Kurapaty S.S., Patel A.A., Divi SN. Impact of social determinants of health in spine surgery. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2023;16(1):24–32. doi: 10.1007/s12178-022-09811-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiner D.K., Holloway K., Levin E., et al. Identifying biopsychosocial factors that impact decompressive laminectomy outcomes in veterans with lumbar spinal stenosis: a prospective cohort study. Pain. 2021;162(3):835–845. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holbert S.E., Andersen K., Stone D., Pipkin K., Turcotte J., Patton C. Social determinants of health influence early outcomes following lumbar spine surgery. Ochsner J. 2022;22(4):299–306. doi: 10.31486/toj.22.0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohanty S., Lad M.K., Casper D., Sheth N.P., Saifi C. The impact of social determinants of health on 30 and 90-day readmission rates after spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2022;104(5):412–420. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.21.00496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Department of Health and Human Services OoDPaHP Healthy People 2030, Social Determinants of Health. 2023. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health [cited.

- 22.Joo JY. Fragmented care and chronic illness patient outcomes: a systematic review. Nurs Open. 2023;10(6):3460–3473. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timmins L., Kern L.M., O'Malley A.S., Urato C., Ghosh A., Rich E. Communication gaps persist between primary care and specialist physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2022;20(4):343–347. doi: 10.1370/afm.2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kern L.M., Bynum J.P.W., Pincus HA. Care fragmentation, care continuity, and care coordination-how they differ and why it matters. JAMA Intern Med. 2024;184(3):236–237. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.7628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juo Y.Y., Sanaiha Y., Khrucharoen U., Chang B.H., Dutson E., Benharash P. Care fragmentation is associated with increased short-term mortality during postoperative readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery. 2019;165(3):501–509. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2018.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan I.S., Huang E., Maeder-York W., et al. Racial disparities in outcomes after spine surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2022;157:e232–ee44. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.09.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trinidad S., Brokamp C., Mor Huertas A., et al. Use Of area-based socioeconomic deprivation indices: a scoping review and qualitative analysis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2022;41(12):1804–1811. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chamberlain A.M., Finney Rutten L.J., Wilson P.M., et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage is associated with multimorbidity in a geographically-defined community. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-8123-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordon A.M., Elali F.R., Ng M.K., Saleh A., Ahn NU. Lower neighborhood socioeconomic status may influence medical complications, emergency department utilization, and costs of care after 1-2 level lumbar fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2023 doi: 10.1097/brs.0000000000004588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J.K., Greenberg J.K., Javeed S., et al. Association between neighborhood-level socioeconomic disadvantage and patient-reported outcomes in lumbar spine surgery. Neurosurgery. 2023;92(1):92–101. doi: 10.1227/neu.0000000000002181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen S.A., White R.S., Tangel V., Nachamie A.S., Witkin LR. Sociodemographic characteristics predict readmission rates after lumbar spinal fusion surgery. Pain Med. 2020;21(2):364–377. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kind A.J., Jencks S., Brock J., et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30-day rehospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):765–774. doi: 10.7326/m13-2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kind A.J.H., Buckingham WR. Making neighborhood-disadvantage metrics accessible - the neighborhood atlas. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2456–2458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1802313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health CfHDR . Unversity of Wisconsin-Madison; Madison, WI, USA: 2023. Neighborhood atlas.https://www.neighborhoodatlas.medicine.wisc.edu/ [citedOctober 15]; Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khuri S.F., Daley J., Henderson W., et al. The Department of Veterans Affairs' NSQIP: the first national, validated, outcome-based, risk-adjusted, and peer-controlled program for the measurement and enhancement of the quality of surgical care. National VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Ann Surg. 1998;228(4):491–507. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199810000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghaferi A.A., Schwartz T.A., Pawlik TM. STROBE Reporting Guidelines for Observational Studies. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(6):577–578. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knighton A.J., Savitz L., Belnap T., Stephenson B., VanDerslice J. Introduction of an area deprivation index measuring patient socioeconomic status in an integrated health system: implications for population health. EGEMS (Wash DC) 2016;4(3):1238. doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arya S., Varley P., Youk A., et al. Recalibration and external validation of the risk analysis index: a surgical frailty assessment tool. Ann Surg. 2020;272(6):996–1005. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000003276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gagne J.J., Glynn R.J., Avorn J., Levin R., Schneeweiss S. A combined comorbidity score predicted mortality in elderly patients better than existing scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(7):749–759. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shinall M.C., Jr, Youk A., Massarweh N.N., et al. Association of preoperative frailty and operative stress with mortality after elective vs emergency surgery. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shinall M.C., Jr., Arya S., Youk A., et al. Association of preoperative patient frailty and operative stress with postoperative mortality. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(1) doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.4620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan Q., Kim J., Hall D.E., et al. Association of frailty and the expanded operative stress score with preoperative acute serious conditions, complications, and mortality in males compared to females: a retrospective observational study. Ann Surg. 2023;277(2):e294–e304. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000005027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall D.E., Arya S., Schmid K.K., et al. Development and initial validation of the risk analysis index for measuring frailty in surgical populations. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(2):175–182. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.George E.L., Hall D.E., Youk A., et al. Association between patient frailty and postoperative mortality across multiple noncardiac surgical specialties. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(1) doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.5152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rasmussen P., Farmer CM. The promise and challenges of VA community care: veterans' issues in focus. Rand Health Q. 2023;10(3):9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khalid S.I., Maasarani S., Nunna R.S., et al. Association between social determinants of health and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing single-level lumbar fusions: a matched analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2021;46(9):E559–Ee65. doi: 10.1097/brs.0000000000003829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hagan M.J., Sastry R.A., Feler J., et al. Neighborhood-level socioeconomic status, extended length of stay, and discharge disposition following elective lumbar spine surgery. N Am Spine Soc J. 2022;12 doi: 10.1016/j.xnsj.2022.100187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hagan M.J., Sastry R.A., Feler J., et al. Neighborhood-level socioeconomic status predicts extended length of stay after elective anterior cervical spine surgery. World Neurosurg. 2022;163:e341–e3e8. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.03.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ng G.Y., Karsalia R., Gallagher R.S., et al. The impact of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage on operative outcomes after single-level lumbar fusion. World Neurosurg. 2023;180:e440–e4e8. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2023.09.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kamath C.C., O'Byrne T.J., Lewallen D.G., Berry D.J., Maradit Kremers H. Neighborhood-level socioeconomic deprivation, rurality, and long-term outcomes of patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty: analysis from a large, tertiary care hospital. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2022;6(4):337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2022.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lund B.C., Ohl M.E., Hadlandsmyth K., Mosher HJ. Regional and rural-urban variation in opioid prescribing in the Veterans Health Administration. Mil Med. 2019;184(11-12):894–900. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usz104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bennett M.D., Jr., McDaniel J.T., Albright D.L. Chronic disease multimorbidity and substance use among African American men: veteran-non-veteran differences. Ethn Health. 2023;28(8):1145–1160. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2023.2224949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Engler I.D., Vasavada K.D., Vanneman M.E., Schoenfeld A.J., Martin BI. Do community-level disadvantages account for racial disparities in the safety of spine surgery? A large database study based on medicare claims. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2023;481(2):268–278. doi: 10.1097/corr.0000000000002323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aladdin D.E.H., Tangel V., Lui B., Pryor K.O., Witkin L.R., White RS. Black race as a social determinant of health and outcomes after lumbar spinal fusion surgery: a multistate analysis, 2007 to 2014. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2020;45(10):701–711. doi: 10.1097/brs.0000000000003367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Owodunni O.P., Yocky A.G., Courville E.N., et al. A comprehensive analysis of the triad of frailty, aging, and obesity in spine surgery: the risk analysis index predicted 30-day mortality with superior discrimination. Spine J. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2023.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bays A., Stieger A., Held U., et al. The influence of comorbidities on the treatment outcome in symptomatic lumbar spinal stenosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. N Am Spine Soc J. 2021;6 doi: 10.1016/j.xnsj.2021.100072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bono O.J., Poorman G.W., Foster N., et al. Body mass index predicts risk of complications in lumbar spine surgery based on surgical invasiveness. Spine J. 2018;18(7):1204–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2017.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goyal A., Elminawy M., Kerezoudis P., et al. Impact of obesity on outcomes following lumbar spine surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2019;177:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2018.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lenoir K.M., Paul R., Wright E., et al. The association of frailty and neighborhood disadvantage with emergency department visits and hospitalizations in older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s11606-023-08503-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maharani A., Sinclair D.R., Chandola T., et al. Household wealth, neighbourhood deprivation and frailty amongst middle-aged and older adults in England: a longitudinal analysis over 15 years (2002-2017) Age Ageing. 2023;52(3) doi: 10.1093/ageing/afad034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yap Z.L., Summers S.J., Grant A.R., Moseley G.L., Karran EL. The role of the social determinants of health in outcomes of surgery for low back pain: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Spine J. 2022;22(5):793–809. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2021.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

These data cannot be disclosed upon request, as they are confidential and privileged under the provisions of 38 U.S.C. 5705 and internal VA policy.