Abstract

Radiotherapy (RT) is a cornerstone of cancer treatment but limited by its dual role in modulating the tumor immune microenvironment: while promoting immunogenic cell death (ICD), RT concurrently upregulates PD-L1 to suppress antitumor immunity. To address this limitation, we developed PEP-PLG-IMDQ, a polymer-peptide-immune agonist nanomedicine that synergizes RT with immunotherapy. This nanoplatform employs a poly (L-glutamic acid) carrier conjugated with a PD-L1-targeting peptide and the TLR7/8 agonist imidazoquinoline (IMDQ), enabling three-pronged action: (1) PD-L1-mediated tumor targeting, (2) TLR7/8-driven dendritic cell activation, and (3) reinforcement of the anti-tumor immune cycle. In CT26 tumor-bearing mice, RT combined with PEP-PLG-IMDQ achieved 98.1 % tumor suppression, with 83 % long-term survival and complete resistance to tumor rechallenge. Mechanistically, the combination therapy enhanced CD8+ T cell infiltration (5.3-fold vs. RT alone) and established durable immune memory. Our work provides a translatable strategy to overcome radioresistance through spatiotemporal immune modulation.

Keywords: Radiotherapy, PD-L1-targeted nanomedicine, TLR7/8 agonist, Immunogenic cell death, Tumor immune microenvironment

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

PD-L1-targeted nanomedicine synergizes radiotherapy for durable tumor control.

-

•

Triple-action mechanism reshapes immunosuppressive microenvironment.

-

•

Optimized nanoplatform with enhanced tumor specificity.

-

•

Clinical-translatable biosafety profile.

1. Introduction

Radiotherapy (RT) remains a cornerstone of clinical cancer treatment [[1], [2], [3]]. However, its efficacy is limited by variability in tumor radiosensitivity and patient-specific factors, often resulting in suboptimal therapeutic outcomes. To address this challenge, strategies to enhance RT's antitumor effects are urgently needed. Emerging evidence highlights RT's dual role in shaping the tumor immune microenvironment: while it potentiates antitumor immunity by increasing tumor antigen exposure, promoting immunogenic cell death, and enhancing chemokine release, it simultaneously suppresses immune responses through upregulation of inhibitory markers (e.g., PD-L1, CD73), activation of TGF-β signaling, and secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines [[4], [5], [6], [7]]. This duality is further complicated by the remarkable heterogeneity of tumor microenvironment (TME) across tumor types. For instance, immunologically "hot" tumors (e.g., melanoma) exhibit abundant T cell infiltration, whereas "cold" tumors (e.g., pancreatic adenocarcinoma) are characterized by dense stromal barriers and immunosuppressive cell populations [8,9]. Such complexity necessitates tumor model selection that recapitulates key TME features relevant to therapeutic interventions. The CT26 colorectal carcinoma model was chosen for its well-characterized immunosuppressive microenvironment featuring upregulated PD-L1 expression post-RT [10], thereby providing a clinically relevant platform to evaluate immunomodulatory strategies. These counterproductive mechanisms diminish RT's therapeutic potential, underscoring the critical need for immunostimulatory agents that can amplify RT-driven antitumor immunity and overcome current limitations in treatment efficacy.

Since the concept of “immunoradiotherapy” was first proposed by Demaria et al., in 2005 [11], this approach has emerged as a promising strategy for cancer treatment. Current clinical efforts primarily focus on combining radiotherapy (RT) with PD-1/PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies, though therapeutic efficacy remains limited. In contrast, peptides offer distinct advantages over antibodies, including enhanced tissue penetration, minimal immunogenicity, and cost-effective production with shorter development cycles [[12], [13], [14]]. These attributes have positioned peptide-based therapies as a key research focus in oncology [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]]. Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which recognize pathogen-associated (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), play a critical role in activating dendritic cells (DCs) [16,[21], [22], [23]]. TLR-mediated DC activation represents a pivotal bridge between innate and adaptive immunity. Mature DCs upregulate co-stimulatory molecules (CD80/CD86) and MHC class I/II complexes, enabling efficient tumor antigen presentation to naïve T cells in lymph nodes [24].This process is particularly crucial in radiotherapy contexts, where RT-generated tumor antigens require DC-mediated cross-presentation to activate cytotoxic CD8+ T cells [24].

Specifically, TLR7 and TLR8 overexpression in DCs enables ligand binding, triggering DC activation, enhanced tumor antigen presentation, and subsequent CD8+ T cell infiltration for tumor eradication. Imidazoquinolines (IMDQs), synthetic TLR7/8 agonists, hold therapeutic potential but face clinical challenges due to systemic inflammatory responses caused by off-target effects [[25], [26], [27]]. Consequently, developing tumor-targeting IMDQs to mitigate toxicity while retaining efficacy is crucial for advancing their clinical application.

In this study, we developed PEP-PLG-IMDQ, a tumor-targeting polymer-peptide-immune agonist nanomedicine designed to selectively deliver the TLR7/8 agonist imidazoquoline (IMDQ) to murine tumor sites. This novel nanomedicine comprises three components: (1) a PD-L1-targeting peptide, (2) a poly (L-glutamic acid) (PLG) nanocarrier, and (3) the immunostimulatory agonist IMDQ. RT primes the tumor immune microenvironment by upregulating PD-L1 expression on tumor cells, enabling targeted accumulation of PEP-PLG-IMDQ. Upon binding to TLR7/8 on intratumoral dendritic cells (DCs), the nanomedicine activates DCs, enhances tumor antigen presentation, and promotes CD8+ T cell infiltration, thereby exerting localized antitumor effects. Furthermore, this strategy induces durable immune memory, which prevents tumor recurrence and significantly improves survival outcomes (Scheme 1).

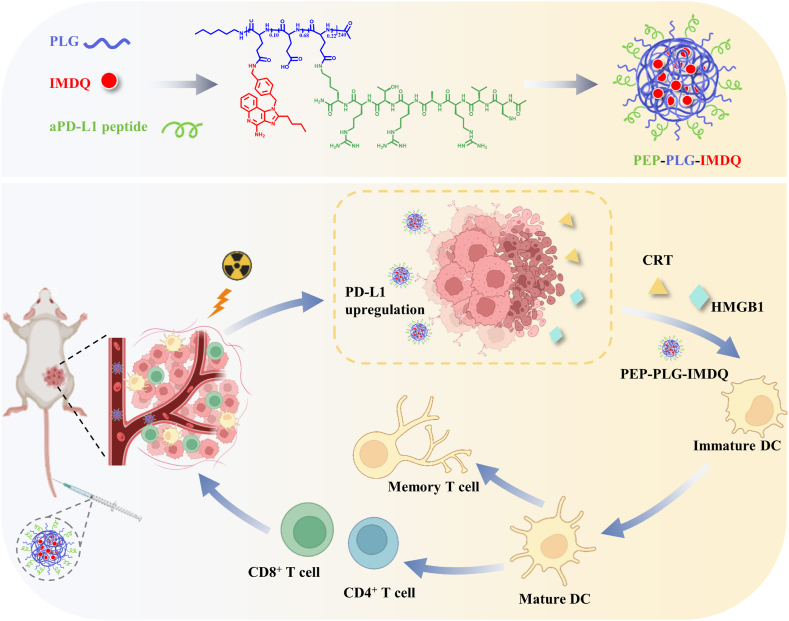

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of the preparation and therapeutic mechanism of the polymer-peptide-immune agonist nanomedicine (PEP-PLG-IMDQ). Radiotherapy (RT)-treated tumors exhibit upregulated PD-L1 expression, whichserves as a molecular target for precision drug delivery. PEP-PLG-IMDQ integrates two functional components: (i) a PD-L1-targeting peptide to direct tumor-selective accumulation and (ii) the toll-like receptor 7/8 (TLR7/8) agonist imidazoquinoline (IMDQ) to orchestrate antitumor immunity. Upon systemic administration, PEP-PLG-IMDQ selectively accumulates in irradiated tumors, where it activates intratumoral dendritic cells via TLR7/8 signaling. This dendritic cell activation triggers a cascade of immune responses, including robust cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) infiltration and the establishment of long-term immune memory, thereby amplifying systemic antitumor efficacy and suppressing metastatic recurrence. This schematic was designed using BioRender.com.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

IMDQ was purchased from Nebulae Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, China). PD-L1-targeting peptide was purchased from Qybio Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All antibodies used for flow cytometry were purchased from Biolegend Co., Ltd. (CA, USA). Cy5-NH2 was purchased from DuoFluor Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (CRE), uric acid (UA), alkaline phosphatase (AKP), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ATL) assay kits were purchased from Chengjian Bioengineering Research Institute (Nanjing, China). Hoechst 33342 and Lysotracker-green were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Characterization

1H NMR spectrums were measured on a Bruker AV-500 nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer. Ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) absorption spectrums were recorded on a UV-2401PC spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan). Dynamic laser scattering (DLS) and Zeta measurements were performed on a Malvern zetasizer instrument (Nano-ZS). PEP-PLG-IMDQ morphological features were observed using a transmission electron microscope (JEOL JEM-1011 TEM). Images of tissue sections with immunofluorescence were obtained using confocal laser scanning microscopy. (CLSM, Carl Zeiss LSM 780, Germany).

2.3. Cells and animals

The CT26 and DC2.4 cell lines were sourced from Fuheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1 % penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C under a atmosphere of 5 % CO2 and 95 % air (approximately 20 % O2). Female BALB/c mice (aged 6–8 weeks) and Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were acquired from Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) and Changsheng Laboratory Animal Center (Liaoning, China), respectively. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Animal Welfare and Ethics Committees of the Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry (Chinese Academy of Sciences) and Jilin University.

2.4. Synthesis of PEP-PLG-IMDQ and PLG-IMDQ

Poly (L-glutamic acid) (PLG) was synthesized as previously described [28]. Briefly, PLG (0.85 g) was dissolved in anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF, 40.0 mL). To this solution, EDCI (172 mg, 0.896 mmol), NHS (120 mg, 1.04 mmol), IMDQ (150 mg, 0.4 mmol), and the PD-L1-targeting peptide (340 mg, 0.33 mmol) were added sequentially. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 72 h. The crude product was dialyzed against distilled water (pH adjusted to 8.0 with sodium bicarbonate) for 72 h and lyophilized to yield the final conjugate. For the control polymer PLG-IMDQ, the same protocol was followed, excluding the PD-L1-targeting peptide.

2.5. Drug release profiling

The release kinetics of IMDQ from PEP-PLG-IMDQ nanocomposites (10 mg) were characterized using dynamic dialysis methodology. Test samples dissolved in 2 mL PBS or PBS containing 10 % fetal bovine serum were loaded into dialysis membranes (MWCO 3.5 kDa) and dialyzed against 28 mL matching solvent reservoirs under physiologically relevant conditions (37 °C, 100 rpm agitation). At predetermined time intervals, 1 mL aliquots were withdrawn from the external reservoir for chromatographic analysis. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was conducted using a C18 reverse-phase column with isocratic elution (acetonitrile/water containing 0.05 % trifluoroacetic acid) and ultraviolet detection at 245 nm, enabling precise quantification of released IMDQ.

2.6. Plasma pharmacokinetics study

Cy5-labeled PEP-PLG-IMDQ was intravenously administered to SD rats (n = 3). Blood samples were collected from the retro-orbital venous plexus at designated timepoints, and fluorescence intensity was measured to quantify PEP-PLG-IMDQ blood concentration. The in vivo circulating half-life was determined using a two-compartment pharmacokinetic model.

2.7. Cellular uptake of PEP-PLG-IMDQ

CT26 and DC2.4 cells were seeded into confocal dishes at a density of 3 × 105 cells/dish and incubated overnight. Cy5-PEP-PLG-IMDQ (2 μg/mL) was added to the cultures and incubated at 37 °C for 0.5, 1, 2, or 4 h. After incubation, cells were washed three times with PBS, and images were acquired using CLSM.

2.8. Formula optimization of PEP-PLG-IMDQ

The drug feeding ratios (Table 1) were labeled with Cy5-NH2, and the compounds were synthesized as previously described. We evaluated the PD-L1 binding affinity of PEP-PLG-IMDQ with varying feeding ratios both in vitro and in vivo. For the in vitro study, CT26 cells (3 × 105 cells/well) were co-incubated with Cy5-PEG-PLG-IMDQ (2 μg/mL) at 4 °C or 37 °C for 1 h. Fluorescence intensity was quantified via flow cytometry to assess cellular binding and uptake. For the in vivo study, BALB/c mice bearing CT26 tumors were intravenously administered Cy5-PEG-PLG-IMDQ (20 mg/kg). Tumors were excised 24 h post-injection, and intratumoral drug enrichment was analyzed via fluorescence imaging.

Table 1.

Sample detail.

| PEP-PLG-IMDQ sample | Content of PD-L1-targeting peptide and IMDQ (w%) |

Feeding content of PD-L1-targeting peptide and IMDQ (w%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD-L1-targeting peptide | IMDQ | PD-L1-targeting peptide | IMDQ | |

| Carrier 1 | 7.1 | 11.6 | 7.8 | 15.0 |

| Carrier 2 | 11.8 | 11.6 | 14.6 | 15.0 |

| Carrier 3 | 22.1 | 9.6 | 25.4 | 15.0 |

| Carrier 4 | 31.6 | 9.0 | 39.0 | 15.0 |

2.9. In vitro DCs activation

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were differentiated from femoral marrow isolates of 4–5 week-old female C57BL/6 mice (Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd.) under controlled culture conditions. Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum, 1 % penicillin-streptomycin, 10 ng/mL interleukin-4 (IL-4), and 20 ng/mL granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), with half-medium replacements performed on culture days 3 and 5 to ensure optimal differentiation. For activation assays, mature BMDCs (1 × 106 cells/well in 12-well plates) were exposed to three experimental conditions: pharmacological stimulation with PEP-PLG-IMDQ (10 μg/mL, eq. to IMDQ), co-culture with untreated CT26 colorectal carcinoma cells (1 × 106 cells/well), or interaction with radiation-pretreated CT26 cells (8 Gy irradiation). Following 24-h incubation under standard culture conditions (37 °C, 5 % CO2), cellular suspensions were prepared for surface marker analysis via flow cytometry while the cell-free supernatant from BMDC cultures was preserved at −80 °C for subsequent cytokine profiling.

2.10. In vivo antitumor efficiency in CT26 bearing mice

A subcutaneous CT26 tumor model was established in female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old) by injecting 100 μL of PBS-resuspended CT26 cells (1.0 × 106 cells/mouse) into the dorsal flank. Tumor-bearing mice (initial volume ≈200 mm3) were randomized into eight treatment groups (n = 5): 1) PBS, 2) RT, 3) IMDQ, 4) PLG-IMDQ, 5) PEP-PLG-IMDQ, 6) RT + IMDQ, 7) RT + PLG-IMDQ, and 8) RT + PEP-PLG-IMDQ. PLG-IMDQ and PEP-PLG-IMDQ were administered intravenously at 2 mg/kg (eq. to IMDQ). RT was delivered as a single 8 Gy dose (4 Gy/min; Elekta platform). Tumor volumes and body weights were monitored every 48 h. Tumor volume (V) was calculated using the formula:

| V=(a × b2)/2, |

where a and b represent the longest and shortest tumor diameters, respectively. The tumor suppression rate (TSR) was calculated as:

| TSR (%) = [(Vc−Vt)/Vc] × 100 %, |

where Vt and Vc denote the mean tumor volumes of the treatment and PBS control groups, respectively.

On day 10, mice were euthanized, and tumors, draining lymph nodes, and spleens were harvested for flow cytometry. Major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys) and tumors were sectioned for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunofluorescence analysis. In survival studies, tumor volumes were recorded daily, and mice were euthanized when tumors approached 2000 mm3.

2.11. Post-therapy immune profiling

On day 10 post-treatment, tumor tissues, draining lymph nodes, and spleens were harvested from experimental mice (grouping and treatment protocols as described in Section 2.8). Tissues were mechanically dissociated, filtered through a 300 mesh sieve, and washed with PBS. Single-cell suspensions were stained with fluorescently-labeled antibodies and analyzed using a BD FACS Celesta flow cytometer. The following markers were used: T cells (CD3+), CD8+ T cells (CD3+CD8+), CD4+ T cells (CD3+CD4+), activated DCs (CD11c+CD86+, CD11c+CD80+ or CD11c+MHCII+), MDSCs (CD11b+Gr-1+), Tregs (CD25+FOXP3+), Tem+Tcm cells (CD3+CD44+) and Tcm cells (CD3+CD44+CD62L+). Fresh tumor specimens were precisely weighed (10–20 mg fragments) and mechanically homogenized in 1 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) using tissue grinders. The resulting homogenates underwent centrifugation at 12,000×g for 15 minutes at 4 °C to isolate protein-rich supernatants. Parallel processing of venous blood samples yielded serum through standard centrifugation protocols. Subsequent cytokine quantification was performed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits specific for TNF-α and IFN-γ, following established manufacturer protocols with optical density measurements normalized against standard curves.

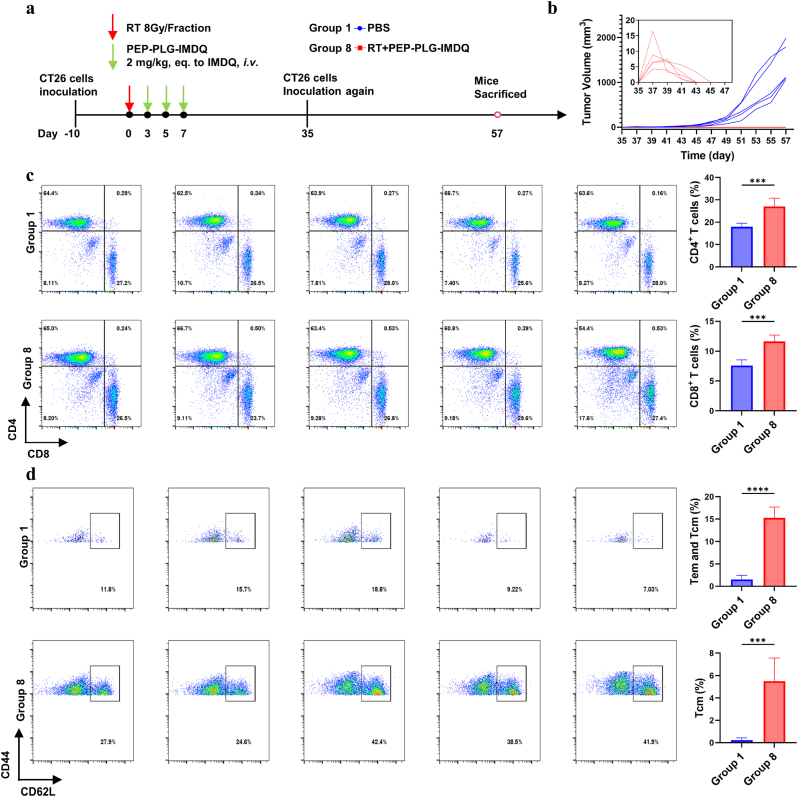

2.12. Tumor re-challenge experiment

Mice bearing CT26 tumors were treated with RT + PEP-PLG-IMDQ (treatment protocols as described in Section 2.10). Tumors that achieved complete regression (cured cohort) were re-challenged with CT26 cells on day 35. Age-matched naive mice served as controls. Tumor growth was monitored every 48 hours via caliper measurements. When tumors approached 2000 mm3, mice were euthanized, and spleens were excised for immune analysis. Splenic single-cell suspensions were prepared, and immune cell subsets were quantified by flow cytometry.

2.13. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.5. Continuous data are presented as mean ± SD. Group comparisons were conducted using: One-way ANOVA (multiple groups) and Unpaired Student's t-test (two-group comparisons). Survival differences were analyzed via Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank testing. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Preparation and characterization of PEP-PLG-IMDQ

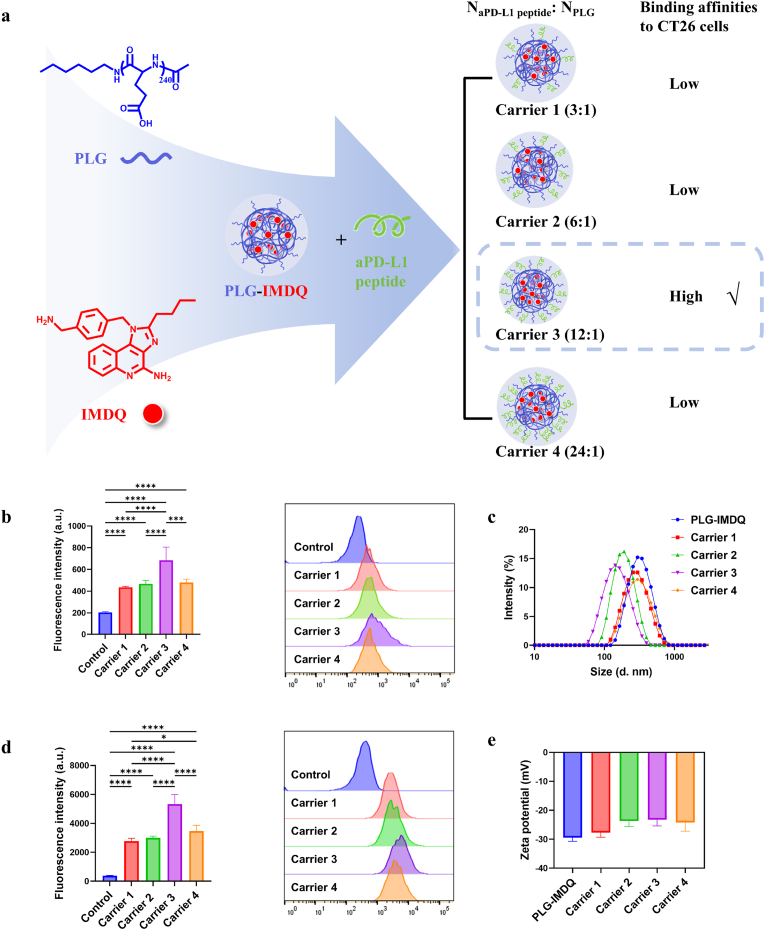

To determine how the density of PD-L1-targeting peptides conjugated to poly (L-glutamic acid) (PLG) chains influences drug targeting in CT26 cells, four PEP-PLG-IMDQ variants with distinct peptide-to-PLG ratios (Table 1) were synthesized, fluorescently labeled (Cy5-PEP-PLG-IMDQ), and characterized. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) revealed significant differences in nanoparticle size and zeta potential (Fig. 1c and e): Carrier 1 (299.1 nm, −27.70 ± 1.57 mV), Carrier 2 (197.5 nm, −23.73 ± 1.86 mV), Carrier 3 (158.4 nm, −23.27 ± 2.11 mV), and Carrier 4 (324.8 nm, −24.23 ± 3.00 mV). The PLG-IMDQ control (337.0 nm, −29.43 ± 1.27 mV) confirmed that peptide conjugation modulates nanoparticle properties. CT26 cells exhibited constitutively high PD-L1 expression compared to normal cells [10]. Flow cytometry revealed that Carrier 3 exhibited the highest in vitro binding affinity to PD-L1 on CT26 cells (Fig. 1b and d). This finding correlated with in vivo results, where Carrier 3 achieved superior tumor accumulation in CT26-bearing mice, as evidenced by significantly higher Cy5 fluorescence intensity (Fig. S1). Based on these results, Carrier 3 (158.4 nm, −23.27 mV) was selected for subsequent experiments due to its optimal PD-L1 targeting and tumor enrichment.

Fig. 1.

Binding kinetics and physicochemical characterization of PEP-PLG-IMDQ variants (Carrier 1–4) with distinct peptide-to-PLG ratios in CT26 cells. a) Synthesis schematic of PEP-PLG-IMDQ. b) Immunofluorescence intensity of CT26 cells incubated with Carrier 1–4 for 1 h at 4 °C (n = 5), demonstrating PD-L1-targeting specificity under non-internalizing conditions. c) Hydrodynamic diameter of Carrier 1–4 and the non-targeted control PLG-IMDQ. d) Immunofluorescence intensity of Carrier 1–4 after 1 h incubation at 37 °C (n = 5), reflecting temperature-dependent cellular internalization. e) Zeta potential of Carrier 1–4 and PLG-IMDQ, highlighting surface charge modulation by peptide conjugation. Gating strategies are detailed in Fig. S2. In (b, d, e), data represent mean ± SD. In (b, d), statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA (∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001; ns, no significance).

Structural validation of PEP-PLG-IMDQ – comprising a PD-L1-targeting peptide, PLG nanocarrier, and TLR7/8 agonist IMDQ – confirmed successful synthesis. 1H NMR revealed characteristic IMDQ aromatic protons (δ 7.0–8.5 ppm) and peptide backbone signals (δ 5.0–6.8 ppm; Fig. S4), while UV–vis spectroscopy showed a blue-shifted λmax (Fig. 2a). The FTIR spectrum of PEP-PLG-IMDQ confirmed the retention of characteristic peaks corresponding to IMDQ, PLG, and PD-L1-targeting peptide (Fig. S5). Quantification via UV spectroscopy (300–350 nm; Fig. S6) determined IMDQ loading at 9.6 %, with peptide content (22.14 %) measured using a fluorometric arginine assay [29] (Fig. S7). IMDQ exhibited a cumulative release of 20 % from PEP-PLG-IMDQ over 7 days in PBS or PBS +10 % serum (Fig. S8).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of PEP-PLG-IMDQnanoparticles.a) UV–vis absorption spectra of PEP-PLG-IMDQ and free IMDQ in DMF. b) Hydrodynamic stability of PEP-PLG-IMDQ in PBS over 144 h, as measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) (n = 3). c) Pharmacokinetic profile of PEP-PLG-IMDQ in vivo, showing plasma concentration over time (n = 3). d) Representative TEM image of PEP-PLG-IMDQ nanoparticles; scale bar: 200 nm. e) Fluorescence microscopy images demonstrating cellular uptake of Cy5-labeled PEP-PLG-IMDQ in DC 2.4 cells after coincubation; scale bar: 50 μm. In (b, c), data represent mean ± SD.

PEP-PLG-IMDQ displayed favorable physicochemical properties: a spherical morphology (Fig. 2d), particle size stability and zeta potential stability in PBS (pH 7.4) for 6 days (Fig. 2b, Fig. S9), and a blood elimination half-life (t1/2) of 3.69 h via two-compartment modeling (Fig. 2c). Cellular uptake studies further demonstrated rapid internalization into both CT26 tumor cells and DC2.4 dendritic cells within 4 h (Fig. 2e and S10), highlighting its dual targeting capability for tumor and immune compartments.

3.2. Radiotherapy induces dose- and time-dependent PD-L1 upregulation in CT26 cells

To investigate RT-driven immune evasion mechanisms in CT26 cells, we analyzed PD-L1 expression via flow cytometry following irradiation (0–10 Gy). In vitro, PD-L1 levels increased significantly 48 hours post-irradiation (2–10 Gy), with further upregulation observed at 72 hours (Fig. 3a and b, Figure S11). This dose- and time-dependent response suggests sustained RT-induced immunosuppressive signaling.

Fig. 3.

RT upregulates PD-L1 expression in CT26 cells and enhances tumor-targeted enrichment of PEP-PLG-IMDQ. a)In vitro flow cytometry analysis of PD-L1 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in CT26 cells 48 h post-RT (n = 5–6). b) PD-L1 MFI in CT26 cells 72 h post-RT (n = 5–6). c)Ex vivo PD-L1 MFI quantification in dissociated tumor tissue (n = 4). Gating strategy is detailed in Figure S3 d)In vivo fluorescence imaging of PEP-PLG-IMDQ distribution in CT26 tumor-bearing mice at indicated time points. e) Quantitative analysis of tumor fluorescence intensity over time (n = 3). f) Fluorescence intensities in ex vivo tumors and major organs harvested at study endpoint (n = 3). In (a, b, c, e, f), data represent mean ± SD. In (a, b, c, f), statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA (∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001; ns, no significance).

In ex vivo tumor models, PD-L1 expression was quantified in CD45-negative tumor cells isolated from irradiated tissues. Consistent with in vitro findings, PD-L1 levels rose markedly by 72 hours post-RT (2–10 Gy) (Fig. 3c, Fig. S11). Immunofluorescence staining of tumor sections corroborated these results, revealing enhanced PD-L1 localization at the tumor interface (Fig. S12). Together, these data demonstrate that RT promotes PD-L1 overexpression on tumor cells, potentially compromising antitumor immunity.

3.3. In vitro activation of BMDCs

First, we evaluated the cytotoxicity of PEP-PLG-IMDQ against CT26 cells in vitro. Incubation of CT26 cells with 100 μM PEP-PLG-IMDQ for 24 or 48 hours showed no significant cytotoxicity (Fig. S13). To assess the stimulatory effect of PEP-PLG-IMDQ on dendritic cells (DCs), BMDCs were co-cultured with PEP-PLG-IMDQ, with IMDQ serving as a positive control [30]. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that PEP-PLG-IMDQ effectively promoted DC activation, comparable to IMDQ (Fig. S14). In PEP-PLG-IMDQ group, ELISA assays demonstrated significant increases in TNF-α and IL-12 p70 levels in the culture supernatants (Fig. S15).

3.4. PD-L1-targeted delivery of PEP-PLG-IMDQ

Peptides offer distinct advantages over monoclonal antibodies for therapeutic targeting, including smaller size, enhanced tumor penetration, reduced immunogenicity, and structural flexibility that facilitates conjugation with drug payloads [31]. PEP-PLG-IMDQ incorporates a PD-L1-binding peptide previously validated for its high affinity to PD-L1 [17]. We hypothesized that radiotherapy (RT)-induced PD-L1 upregulation in CT26 tumors (Section 3.2) would enhance the tumor-specific accumulation of PEP-PLG-IMDQ.

To test this, Cy5-labeled PEP-PLG-IMDQ and non-targeted PLG-IMDQ were intravenously administered to CT26-bearing mice three days post-RT. In vivo fluorescence imaging revealed significantly stronger tumor enrichment of Cy5-PEP-PLG-IMDQ compared to Cy5-PLG-IMDQ (Fig. 3d and e). Notably, PLG-IMDQ exhibited baseline tumor accumulation unaffected by RT, underscoring the passive targeting inherent to nanoparticle systems. In contrast, PEP-PLG-IMDQ's RT-dependent enhancement suggests active PD-L1-mediated targeting. Ex vivo imaging of dissected tumors further confirmed this trend, with Cy5-PEP-PLG-IMDQ showing 2.3-fold higher fluorescence intensity than the control (Figs. S16 and 3f; p < 0.05). Collectively, these results demonstrate that PEP-PLG-IMDQ achieves robust, PD-L1-driven tumor targeting, leveraging RT-induced immune checkpoint upregulation to improve therapeutic precision.

3.5. PEP-PLG-IMDQ combined with RT repressed CT26 tumor growth via enhanced antitumor immunity

RT is a well-established inducer of immunogenic cell death (ICD), characterized by the release of damage-associated molecular patterns such as HMGB1 and calreticulin (CRT) [32]. Consistent with this mechanism, we observed significant upregulation of HMGB1 and CRT in vitro CT26 cells and in ex vivo CT26 tumors following 2–10 Gy irradiation (Figs. S17 and S18). However, RT alone often fails to elicit robust systemic antitumor immunity due to insufficient antigen presentation and transient ICD signaling. To address this limitation, we combined RT with PEP-PLG-IMDQ, a PD-L1-targeted nanoparticle delivering the TLR7/8 agonist IMDQ, to amplify immunogenic signaling within the TME.

Prior to conducting in vivo experiments, we first evaluated the interaction between BMDCs and CT26 cells (with or without prior radiotherapy) in vitro. BMDCs were co-cultured with CT26 cells and PEP-PLG-IMDQ under controlled conditions. Notably, when BMDCs were incubated together with irradiated CT26 cells and PEP-PLG-IMDQ, a significantly higher proportion of BMDCs exhibited activation markers compared to other experimental groups (Fig. S19).

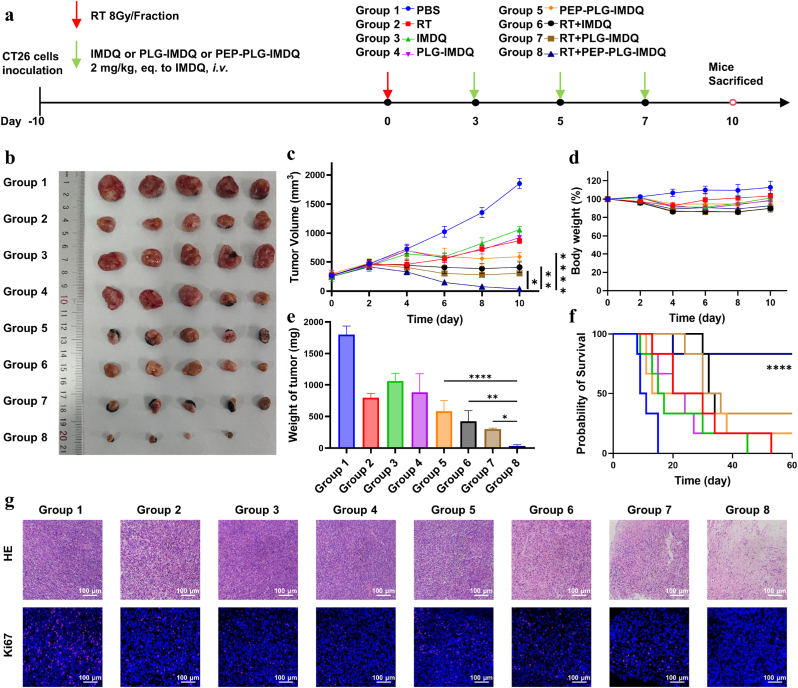

In CT26 tumor-bearing mice, the combination of RT and PEP-PLG-IMDQ demonstrated striking therapeutic synergy. Eight treatment groups—including controls (PBS, RT alone, free IMDQ, non-targeted PLG-IMDQ, PEP-PLG-IMDQ, RT + IMDQ, RT + PLG-IMDQ and RT + PEP-PLG-IMDQ)—were evaluated for tumor growth and survival. By day 10, tumors in the RT + PEP-PLG-IMDQ group were reduced to 35.3 mm3 (98.1 % suppression), compared to 1854.1 mm3 in PBS-treated controls, 871.3 mm3 with RT alone, 1062.7 mm3 with free IMDQ, 925.0 mm3 with non-targeted PLG-IMDQ, 589.8 mm3 with PEP-PLG-IMDQ, 410.1 mm3 with RT + IMDQ and 304.7 mm3 with RT + PLG-IMDQ (Fig. 4b and c). While RT transiently slowed growth (53 % suppression at day 10), only the combination therapy achieved near-complete tumor control. No mortality occurred in all treatment groups until day 10, and mice in the combination treatment groups showed a decrease in body weight, with the largest body weight decrease of 14 % occurring in the RT + IMDQ group (Fig. 4d). Histopathological analysis of major organs (Fig. S20) and blood biochemical markers (Fig. S21) revealed no treatment-related abnormalities (alkaline phosphatase (AKP), uric acid (UA) aspartate aminotransferase (AST), creatinine (CRE), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and blood urea nitrogen (BUN)). Histological evaluation confirmed extensive tumor necrosis and suppressed proliferation in the combination group (Fig. 4g), aligning with its superior efficacy. Immunofluorescence staining confirmed that radiotherapy induced ICD in treated groups (Fig. S22). Survival studies further underscored the durability of this approach, with 83 % (5/6) of RT + PEP-PLG-IMDQ-treated mice surviving to day 60, compared to rapid progression in control groups (Fig. 4f). Based on these findings, IMDQ conjugated PD-L1-targeting peptide in combination with RT is an effective therapeutic strategy.

Fig. 4.

In vivo antitumor efficacy of PEP-PLG-IMDQ in CT26 tumor-bearing mice. a) Schematic of the experimental treatment protocol. b)Ex vivo tumor images from each group at day 10 (n = 5). c) Tumor growth curves across treatment groups (mean ± SEM; n = 5). d) Body weight trends monitored as a surrogate for systemic toxicity (mean ± SD; n = 5). e) Final ex vivo tumor weights (mean ± SD; n = 5). f) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (n = 6). g) Histopathological (H&E) and immunofluorescence staining of tumor sections post-treatment, revealing therapeutic effects on tumor architecture and biomarker expression. In (c, e), statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA (∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001; ns, no significance).

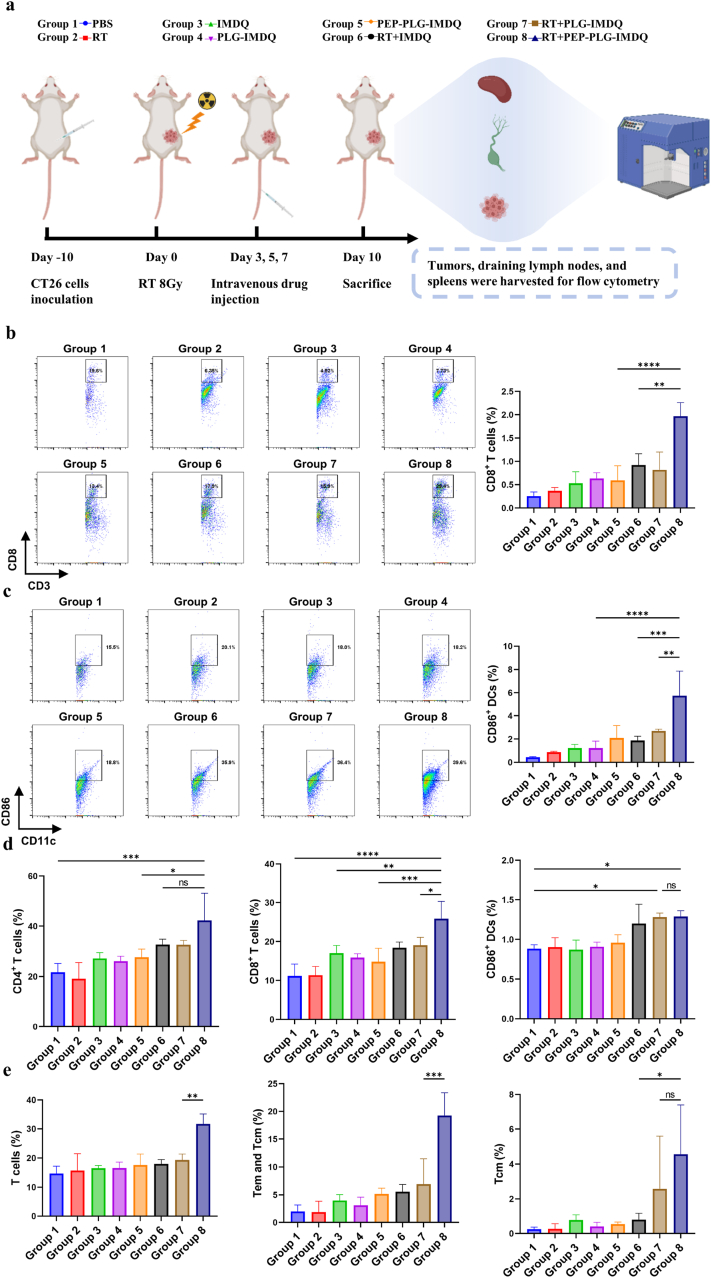

Mechanistically, RT + PEP-PLG-IMDQ synergizes through dual actions: RT generates tumor-specific antigens (TSAs) via ICD, while PEP-PLG-IMDQ delivers IMDQ to PD-L1-enriched tumors, activating dendritic cells (DCs) and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Flow cytometry revealed robust immune activation in RT + PEP-PLG-IMDQ-treated tumors, with CD3+CD8+ T cells (1.97 % vs. 0.37 % in RT alone) and CD3+CD4+ T cells (2.07 % vs. 0.32 %) infiltrating the TME (Fig. 5b and c; S23). DC maturation markers CD86+ (5.75 % vs. 0.8 %) and MHC-II+ (9.47 % vs. 2.26 %) were also elevated (Fig. 5c), indicating enhanced antigen presentation. This immune activation extended systemically: draining lymph nodes showed increased T-cell infiltration and DC activation (Fig. 5d and S24), In addition, memory T cells in the spleen were examined. The results showed that the levels of central memory T cells (Tcm) (CD3+CD44+CD62L+ cells) and effector memory T cells (Tem) (CD3+CD44+CD62L− cells) were significantly increased in the spleens of mice treated with RT + PEP-PLG-IMDQ compared to those treated with RT alone (Tcm: 4.55 % vs. 0.26 %; T cm and Tem: 19.23 % vs. 1.97 %), suggesting the occurrence of persistent anti-tumor immunity. (Fig. 5e and S25). The combination of radiotherapy (RT) and PEP-PLG-IMDQ markedly reduced the populations of immunosuppressive cells, including myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and regulatory T cells (Tregs), compared to controls (Fig. S26). Serum and tumor tissue analyses revealed significantly higher levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ in the RT + PEP-PLG-IMDQ group compared to radiotherapy alone, indicating robust immune stimulation (Fig. S27).

Fig. 5.

Systemic immune remodeling across tumor, lymphoid, and peripheral tissues following therapeutic intervention in CT26 tumor-bearing mice. a) Schematic workflow of the immunoassay protocol for multi-tissue immune profiling. b), c) Proportions of immune cell subsets within tumors across treatment groups, with representative flow cytometry plots (n = 3). d) Flow cytometric analysis of immune cell frequencies in tumor-draining lymph nodes (TDLNs) and (e) spleen (n = 3). Gating strategies are detailed in Fig. S28–S30. In (b, c, d, e), data represent mean ± SD and statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA (∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001; ns, no significance).

These findings establish RT + PEP-PLG-IMDQ as a potent strategy to overcome the limitations of standalone RT. The approach achieves localized immune amplification and systemic memory, offering a translatable paradigm for precision radio-immunotherapy.

3.6. RT + PEP-PLG-IMDQ effectively prevents recurrence of CT26 tumors

The establishment of immune memory following tumor eradication is critical for preventing recurrence. To evaluate whether RT + PEP-PLG-IMDQ induces durable antigen-specific immune memory, we performed tumor re-challenge experiments in mice cured of CT26 tumors. On day 35 post-treatment, these mice were re-inoculated with CT26 cells, and tumor growth was monitored until day 57 (Fig. 6a). Remarkably, all five mice treated with RT + PEP-PLG-IMDQ showed complete resistance to tumor recurrence, with no detectable tumor progression during the observation period (Fig. 6b). In contrast, control groups exhibited rapid tumor regrowth. These findings strongly suggest that the combination of RT and PEP-PLG-IMDQ generates robust, long-term immune memory capable of protecting against tumor relapse.

Fig. 6.

Immune memory response in CT26 tumor re-challenged mice post-treatment with PEP-PLG-IMDQ. a) Schematic of the tumor re-challenge experimental design. b) Individual tumor growth curves in mice following secondary tumor inoculation (n = 5). c) and d) Immune cell subset frequencies in splenic tissue and flow cytometry plots (n = 5). In (c, d) statistical significance was determined using an unpaired Student's t-test and data represent mean ± SD (∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001; ns, no significance).

To investigate the immunological mechanisms underlying this protective effect, we analyzed lymphocyte populations in immune organs. Flow cytometry of splenic immune cells on day 57 revealed significant increases in CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ T-cell populations in treated mice compared to controls (Fig. 6c). Notably, memory T-cell subsets—essential mediators of sustained antitumor immunity—were substantially enriched in the spleens of RT + PEP-PLG-IMDQ-treated mice (Fig. 6d and S31). Together, these results demonstrate that the combinatorial therapy promotes the expansion and persistence of memory T-cell populations, establishing a durable immunological barrier against tumor recurrence.

4. Conclusion

This study presents a synergistic therapeutic strategy that amplifies RT's antitumor efficacy through targeted immune modulation. While RT effectively upregulates PD-L1 expression in tumor cells, we demonstrate that coupling it with polymer-peptide-immune agonist nanomedicine (PEP-PLG-IMDQ) enables precise tumor targeting and DC activation.

This dual-action approach not only enhances CD8+ T cell infiltration but also establishes a potent, localized antitumor immune response. In the CT26 murine model, the RT + PEP-PLG-IMDQ combination achieved a remarkable 98.1 % tumor suppression rate (TSR) and induced durable immune memory, as evidenced by complete resistance to tumor re-challenge. These findings highlight the strategy's transformative potential for clinical translation, particularly as a platform adaptable to combinatory therapies.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jincheng Du: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Chuwen Luo: Data curation. Ya Liu: Data curation. Wenye Tan: Formal analysis. Kun Wang: Data curation. Jiachong Chi: Data curation. Linlin Liu: Supervision, Funding acquisition. Yajun Xu: Supervision, Methodology. Zhaohui Tang: Supervision, Methodology. Xuesi Chen: Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Data availability statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are included within the manuscript and its supplementary materials.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Animal Welfare and Ethics Committees of the Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry (Chinese Academy of Sciences) (2023 Research and Approval No. 0139) and Jilin University (2024 Research and Approval No. 552).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (52403211, 52025035, U24A20477), the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFE0110200), Jilin Provincial Department of Education Scientific Research Project (JJKH20250194BS) and Jilin Provincial International Cooperation Key Laboratory of Biomedical Polymers (YDZJ202402077CXJD).

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of editorial board of Bioactive Materials.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2025.05.017.

Contributor Information

Linlin Liu, Email: liulinl@jlu.edu.cn.

Yajun Xu, Email: yjxu@ciac.ac.cn.

Zhaohui Tang, Email: ztang@ciac.ac.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Verginadis I.I., et al. Radiotherapy toxicities: mechanisms, management, and future directions. Lancet. 2025;405(10475):338–352. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)02319-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price J.M., Prabhakaran A., West C.M.L. Predicting tumour radiosensitivity to deliver precision radiotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023;20(2):83–98. doi: 10.1038/s41571-022-00709-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arina A., Gutiontov S.I., Weichselbaum R.R. Radiotherapy and immunotherapy for cancer: from "systemic" to "multisite". Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;26(12):2777–2782. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charpentier M., et al. Radiation therapy-induced remodeling of the tumor immune microenvironment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022;86(Pt 2):737–747. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrera F.G., et al. Low-dose radiotherapy reverses tumor immune desertification and resistance to immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2022;12(1):108–133. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker H.E., et al. The tumour microenvironment after radiotherapy: mechanisms of resistance and recurrence. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15(7):409–425. doi: 10.1038/nrc3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarosz-Biej M., et al. Tumor microenvironment as A "game changer" in cancer radiotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(13):3212. doi: 10.3390/ijms20133212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeong J.H., et al. Spatial distribution and activation changes of T cells in pancreatic tumors according to KRAS mutation subtype. Cancer Lett. 2025;618 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2025.217641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galon J., Bruni D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18(3):197–218. doi: 10.1038/s41573-018-0007-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsieh R.C., et al. ATR-mediated CD47 and PD-L1 up-regulation restricts radiotherapy-induced immune priming and abscopal responses in colorectal cancer. Sci Immunol. 2022;7(72):eabl9330. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abl9330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demaria S., et al. Combining radiotherapy and immunotherapy: a revived partnership. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2005;63(3):655–666. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper B.M., et al. Peptides as a platform for targeted therapeutics for cancer: peptide-drug conjugates (PDCs) Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021;50(3):1480–1494. doi: 10.1039/d0cs00556h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang X., et al. Insights into therapeutic peptides in the cancer-immunity cycle: update and challenges. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2024;14(9):3818–3833. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2024.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gong L., et al. Research advances in peptide‒drug conjugates. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2023;13(9):3659–3677. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2023.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye J., et al. Inhibiting neutrophil extracellular trap formation through iron regulation for enhanced cancer immunotherapy. ACS Nano. 2025;19(9):9167–9181. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.4c18555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai Y., et al. Inhibiting endothelial cell-mediated T lymphocyte apoptosis with integrin-targeting peptide-drug conjugate filaments for chemoimmunotherapy of triple-negative breast cancer. Adv. Mater. 2024;36(3) doi: 10.1002/adma.202306676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurung S., et al. Phage display-identified PD-L1-binding peptides reinvigorate T-cell activity and inhibit tumor progression. Biomaterials. 2020;247 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.119984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomena J., et al. Targeting the gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRP-R) in cancer therapy: development of bombesin-based peptide-drug conjugates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24(4):3400. doi: 10.3390/ijms24043400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muratspahić E., et al. Design and structural validation of peptide-drug conjugate ligands of the kappa-opioid receptor. Nat. Commun. 2023;14(1):8064. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-43718-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou J., et al. A novel peptide-drug conjugate for glioma-targeted drug delivery. J. Contr. Release. 2024;369:722–733. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2024.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang N., et al. Spatio-temporal delivery of both intra- and extracellular toll-like receptor agonists for enhancing antigen-specific immune responses. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2022;12(12):4486–4500. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tran T.H., et al. Toll-like receptor-targeted particles: a paradigm to manipulate the tumor microenvironment for cancer immunotherapy. Acta Biomater. 2019;94:82–96. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffman B.A.J., et al. Engineered macromolecular Toll-like receptor agents and assemblies. Trends Biotechnol. 2023;41(9):1139–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2023.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mellman I., et al. The cancer-immunity cycle: indication, genotype, and immunotype. Immunity. 2023;56(10):2188–2205. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2023.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.SenGupta D., et al. The TLR7 agonist vesatolimod induced a modest delay in viral rebound in HIV controllers after cessation of antiretroviral therapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021;13(599) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abg3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Everson R.G., et al. TLR agonists polarize interferon responses in conjunction with dendritic cell vaccination in malignant glioma: a randomized phase II Trial. Nat. Commun. 2024;15(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-48073-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janku F., et al. Preclinical characterization and phase I study of an anti-HER2-TLR7 immune-stimulator antibody conjugate in patients with HER2+ malignancies. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2022;10(12):1441–1461. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-21-0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Y., et al. Tumor microenvironment remodeling-mediated sequential drug delivery potentiates treatment efficacy. Adv. Mater. 2024;36(23) doi: 10.1002/adma.202312493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prosser L., et al. Chemical carbonylation of arginine in peptides and proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025;147(12):10139–10150. doi: 10.1021/jacs.4c14476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang R., et al. Spatiotemporal nano-regulator unleashes anti-tumor immunity by overcoming dendritic cell tolerance and T cell exhaustion in tumor-draining lymph nodes. Adv. Mater. 2025;37(5) doi: 10.1002/adma.202412141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang M., et al. Peptide-drug conjugates: a new paradigm for targeted cancer therapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024;265 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.116119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu M.Q., et al. Immunogenic cell death induction by ionizing radiation. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.705361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are included within the manuscript and its supplementary materials.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Animal Welfare and Ethics Committees of the Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry (Chinese Academy of Sciences) (2023 Research and Approval No. 0139) and Jilin University (2024 Research and Approval No. 552).