Abstract

Objective

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) contribute to maternal mortality and morbidity globally. Mobile health technologies may improve HDP management through patient education, facilitating patient-provider communication, and supporting blood pressure self-monitoring through tailored feedback and reminder prompts. Our objective was to understand the digital health needs of women with HDP from low-socioeconomic backgrounds.

Methods

An interactive HDP management digital prototype was developed and evaluated through usability and acceptability testing. Participants included nine pregnant or postpartum women with diagnosed HDP and three maternal-fetal medicine specialists, recruited from two clinics in a predominantly low-income city, Newark, N.J., in 2024 The Technology Acceptance Model was used to guide the assessment of the prototype's acceptability and usability. Data were collected from interviews, a digital literacy questionnaire, and a system usability questionnaire, with quantitative data analyzed descriptively and qualitative data through content analysis.

Results

The median gestational age among pregnant women was 22.0 (17.0, 29.0) weeks, with 89 % identifying as Black/African American. Most women (78 %) reported moderate or high digital health literacy. The mean System Usability score was 81 ± 17, indicating good usability. Three themes were identified: high acceptability and usability, the importance of tailored feedback, and the need for real-time provider-patient communication to support treatment decisions.

Conclusions

These findings indicate a high acceptability and usability of a digital application for HDP management and home blood pressure monitoring among pregnant and postpartum women diagnosed with HDP and their providers in a low-income urban setting.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Postpartum, Hypertension, mHealth, Acceptability, Usability

Highlights

-

•

We used person-centered testing for a hypertensive disorders of pregnancy application.

-

•

Our app prototype for HDP demonstrated high acceptability and usability.

-

•

Timely and tailored feedback on BP readings contributed to app acceptability.

-

•

Interoperability with electronic health records is key for an effective HDP app.

-

•

HDP apps can enhance but not replace vital provider-patient communication and care.

1. Introduction

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP), including chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or combinations thereof, affect 5–10 % of pregnancies worldwide and are a significant contributor to adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes (Duffy et al., 2020) In the United States, HDP remains a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality with African American women and low resourced areas disproportionately (Conklin et al., 2024) Preeclampsia, a form of HDP, can be mild with limited consequences to severe cases leading to complications for both mother and baby, including stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, or renal failure (Leffert et al., 2015). Although only 15–25 % of at-risk women will develop preeclampsia, HDP management often requires frequent clinic visits for blood pressure (BP) monitoring, which can be burdensome and disruptive to daily life (Chen et al., 2017).

With the widespread use of smartphones among young women (Paradis et al., 2022) mobile health (mHealth) applications offer a promising alternative for managing HDP, potentially reducing the need for frequent in-person monitoring while maintaining similar health outcomes (Albadrani et al., 2023; Ganapathy et al., 2016; Pealing et al., 2022). However, most commercially available pregnancy-related BP monitoring applications lack key interactive features for long-term engagement, such as education, tailored feedback, reminders, social support, and incentives (Michie et al., 2017). Despite the potential of mHealth tools to bridge healthcare access gaps, few studies have examined their design for women from low-resource backgrounds, who often face barriers to healthcare and may have differences in digital health literacy (Harris et al., 2017; Whitehead et al., 2023).

To address this, we used a person-centered approach to evaluate the usability, acceptability, and behavior change features of a multicomponent HDP digital application prototype among pregnant and postpartum women recruited from a low-income setting. This mixed methods study aimed to 1) assess the prototype's usability and acceptability and examine variations by digital health literacy among women with HDP, 2) gather insights from providers and women with diagnosed HDP on expected engagement with key behavior change features within the application and 3) triangulate these findings to inform further design and functionality enhancements.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

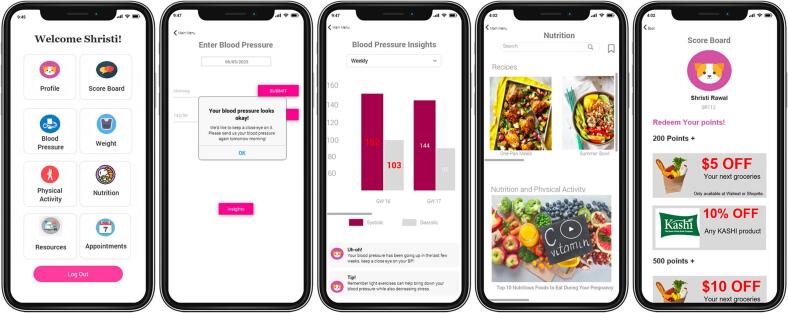

This convergent mixed methods study builds on previous work that led to the development of an interactive, multicomponent digital prototype tailored to the antenatal needs of women with HDP (Wills et al., 2024). Relevant behavior change features were built into the prototype with content informed by a literature review, theory-based behavioral strategies, best practices in digital application design, expert input, and evidence-based HDP management (Carter et al., 2019). Created in Just-in-Time,™ (Fig. 1), this web-based prototype allowed women to test and interact with the application in a simulated environment.

Fig. 1.

Screenshot Examples of the Mobile Application Prototype Designed for Management of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy in Newark, New Jersey, 2024.

2.1.1. Participants and study site

Usability or acceptability testing for the HDP prototype was conducted with nine pregnant or postpartum women with diagnosed HDP and three Maternal and Fetal Medicine (MFM) specialists recruited from a predominantly low-income city. Inclusion criteria for recruited women included age over 18, English proficiency, Wi-Fi access, a computer or mobile device with a camera, and either being pregnant with HDP or postpartum within a two-year diagnosis of HDP. All women provided written informed consent per the Institutional Review Board approval process and received a $50.00 gift card for participation. This study was approved by the Rutgers Health Sciences Newark Electronic Institutional Review Board (Pro202200169).

2.1.2. Sample size

In usability and acceptability studies, there is no formal sample size estimation. However, five respondents typically reveal most issues (Nielsen and Landauer, 1993), but given our additional focus on behavior change feature acceptability, we recruited a sample size of nine women to ensure saturation of feedback.

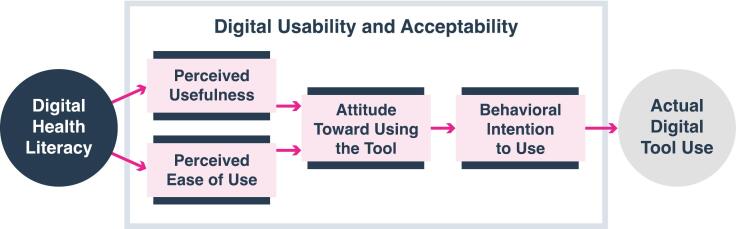

2.1.3. Theoretical framework

We used a person-centered framework, which emphasizes individual preferences and values in designing engaging and effective digital tools (Rhodes et al., 2023; Yardley et al., 2015). Accordingly, our study explored the acceptance of the proposed HDP application, the perceived usefulness of its features, and the degree to which the women believed it would be a valuable and helpful tool in their care. According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (Grassi et al., 2017), usability refers to “the extent to which a product can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction in a specified context of use” (p.56). We focused on behavior change features such as self-monitoring, tailored feedback, action planning, social support, prompts, incentives, rewards, behavior comparison, and educational modules (Abraham and Michie, 2008). Guided by the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989) (Fig. 2), we evaluated barriers and facilitators to adoption, focusing on perceived usefulness (the prototype's acceptability and anticipated benefits) and perceived ease of use (effortlessness of use). Additionally, we assessed women's digital health literacy as a potential contributing factor to acceptance and usability testing.

Fig. 2.

Technology Acceptance Model Used to Guide the Assessment of Acceptability and Usability of a Mobile Application Prototype for Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy in Newark, New Jersey, 2024.

2.2. Data collection tools

Provider feedback was gathered via a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix A), while data on women was collected through a structured interview guide with quantitative and qualitative components (Appendix B). The interview guides were reviewed for partial face validity by two subject matter experts in digital intervention and qualitative methodology to provide feedback on the relevance and clarity of the questions. In addition to the qualitative interviews, quantitative data gathered from the women included demographics and responses on the Digital Health Literacy Scale (DHLS) (Appendix C) (Nelson et al., 2022) and the System Usability Scale (SUS) questionnaire (Lewis, 2018), (Appendix D). The DHLS, a validated three-item questionnaire, assessed digital health application skills (Nelson et al., 2022), while the SUS, a ten-item usability questionnaire, evaluated the prototype's ease of use (Lewis, 2018). Data was collected from women residing in the Newark, N.J area through remote interviews during February and April 2024 by video conference and moderated by two student researchers, a doctoral and master's student, under the supervision of the faculty director. Interviews were audio and video-recorded and securely stored on a cloud-based platform.

2.3. Study procedures

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with three MFM specialists. Providers viewed a demonstration video of the prototype (Appendix A) and then shared insights into patient needs and prototype features. Acceptability and usability testing were conducted with women through structured interviews via video conferencing (Appendix B). The women answered demographic questions and completed the three-item DHLS questionnaire before viewing the demonstration video. They were then provided a URL to engage with the prototype on their device while sharing their screen, allowing researchers to observe the sequence of actions, ease of navigation, or challenges. The women interacted with all features, including the dashboard, menu navigation, data entry, graphical data interpretation, incentives, social support, tailored messaging, gamifications, reminder notifications, and educational modules. The women were also asked to complete tasks such as inputting blood pressure values (“Navigate to the where you would input your blood pressure value”) and interpreting trends (“How would you interpret your blood pressure trends from last week?”). Usability data were collected through women's verbal feedback, researcher observations, and the ten-item SUS questionnaire (Lewis, 2018). We employed the Think Aloud technique (Fonteyn et al., 1993), in which women verbalized their thoughts in real time as they navigated the prototype.

2.4. Data analysis

Qualitative and quantitative data were analyzed separately, and then the results were triangulated to identify areas where the data diverged or confirmed findings. For qualitative data, deductive content analysis was performed (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008). Transcriptions of audio and video recordings were uploaded for coding. Two researchers independently coded the data, resolving discrepancies through discussion to achieve >80 % agreement. Themes were identified and refined through iterative discussions. During qualitative interviews and testing, we tracked the frequency with which participants expressed particular views related to content or prototype navigation. Descriptive statistics were used to report quantitative data, including demographics, DHLS, and SUS responses, using IBM SPSS (v29.0, IBM Inc., Armonk, NY). Categorical data were presented as frequencies, normally distributed data were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and non-normally distributed data as median with interquartile range (IQR). Statistical package, NVivo™ (v14.23, Lumivero, Denver, CO).

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

Nine women with current or recent HDP diagnosis' (within two years) participated in usability testing. Gestational ages for pregnant women ranged from 13 to 36 weeks. The mean age was 32.6 ± 6.1 years, with 56 % (n = 5) diagnosed with chronic hypertension. Most (89 %) identified as Black/African American (Table 1). Nearly 78 % demonstrated moderate to high digital health literacy and actively sought health-related information online. All women reported a comfortable familiarity with technology in the SUS questionnaire. However, two women demonstrated lower digital health literacy based on their responses to questions one and three in the DHLS (Table 2).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Women with Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy who Participated in Usability and Acceptability Testing of a Mobile Application in Newark, New Jersey, 2024 (N = 9).

| Age (years) Mean ± SD Min-Max |

(n = 9) 32.6 ± 6.1 23, 39 n (%) |

|---|---|

| Between 18 and 25 | 2 (22) |

| Between 26 and 33 | 2 (22) |

| Between 34 and 40 | 5 (55) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 1 (11) |

| Black or African American | 8 (89) |

| Pregnancy Status | |

| Pregnant | 7 (78) |

| Postpartum Hypertension Diagnosis | 2 (22) |

| Gestational Hypertension | 1 (11) |

| Chronic Hypertension | 5 (56) |

| Preeclampsia | 1 (11) |

| Preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension | 2 (22) |

| Gestation weeks Mean ± SD |

(n = 7) 23.0 ± 7.7 |

| Median (IQR) | 22.0 (17.0, 29.0) |

| Min-Max | 13.0, 36.0 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; IQR, Interquartile range.

Percentages may not add up to 100 % due to rounding.

IQR is reported as quartile 1, quartile 3.

Nine women recruited, seven pregnant at time of data collection.

Table 2.

Distribution of Responses to Digital Health Literacy Items Among Women with Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy who Participated in Usability and Acceptability Testing of a Mobile Application in Newark, New Jersey, 2024 (N = 9).

| Never n (%) | Rarely n (%) | Sometimes n (%) | Often n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1. How often do you look for answers to health questions on the Internet? | 1 (11) | 1 (11) | 1 (11) | 6 (67) |

| I know a little n (%) | Comfortable w/ technology n (%) |

Excited w/ new technology n (%) |

A technology enthusiast n (%) |

|

| Q2. Which of the following best describes your familiarity with technology? | 0 | 4 (44) | 4 (44) | 1 (11) |

| Low-level technology literacy, 0–1 statements n (%) |

Mid-level technology literacy, 2–3 statements n (%) |

High-level technology literacy, 3+ statements n (%) |

||

Q3. Which statements describe your relationship with technology products? Choose all that applya

|

2 (22) |

1 (11) |

6 (67) |

Abbreviations: HDP, hypertensive disorder of pregnancy.

Scoring for Question 3. High level technology literacy = 3+ statements, Mid-level technology literacy = 1–2 statements, Low level technology literacy = 0 statements.

After reviewing the video and exploring the prototype, the women reported a mean System Usability Score of 81 ± 17, exceeding the median of 68 and indicating good usability (Lewis, 2018). The alignment of DHLS and SUS scores supports strong acceptance, ease of use, and engagement with the application, as corroborated by qualitative feedback.

3.2. Women's feedback

Qualitative results revealed three overarching themes, summarized in Table 3, which provides definitions and illustrative quotes for each. The first theme centered on a high acceptability and usability of the digital application for managing HDP. Acceptability refers to women's perceptions of the application's relevance, desirability, and value for HDP management. Specific drivers included the application's affordability, educational content, and behavior change features, including rewards, incentives, and social support. Usability was described in terms of the ease of navigating the application and its ability to support users in meeting their health goals for managing HDP. The second theme reflected what women valued most about the application, particularly the role of tailored feedback in facilitating action planning. The women appreciated receiving personalized in-app messages in response to their BP readings, reminder prompts for self-monitoring, and visual feedback through charts and graphics that tracked BP and weight. The third theme captured women's desire for improved integration with provider communication, primarily through the electronic health record (EHR). Many women expressed a need for the application to provide personalized feedback and enable seamless communication of concerning readings, particularly high BP values, to their healthcare providers.

Table 3.

Qualitative themes, participant feedback, and interviewer observations from usability and acceptability testing of a mobile application among women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in Newark, New Jersey, 2024 (N = 9).

| Theme | Definition | User Testing |

Sample quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usability Testing | Interviewer Observation | ||

| 1. Acceptability and Usability | |||

| 1a. Willingness to use the application | Comments on the acceptability and the perceived ease of use | Usefulness and Acceptability |

“From what I can see, I love it. And from a person who had no issues prior with blood pressure and now, you know, knowing the seriousness of it, having an application or something that I could use because we're all digital that can help me to track my blood pressure and also kind of, I guess, make it incentivized as well by earning points. I like it. I love it, actually.” “I think it's an amazing idea. I think that it could really take off. Um. I like the fact that it's self-explanatory. It doesn't take rocket scientists or a genius to understand what's going on.” |

| Ease of use | All seven participants who shared their screens, all showed ease of navigation between pages and features. Two women who did not screen share demonstrated difficulty exploring the BP feature. Four women encountered some difficulty interpreting the weight graph |

||

| 1b. Rewards and incentives | Comments on earning points for future material incentives through the use of application with engagement | Usefulness and Acceptability | “Yeah, I think it's really cool. I mean, it's motivational because everybody wants to give you stuff half of some percentage or free. And it keeps you wanting to get more points so you can redeem more.” |

| Ease of use | One in seven women showed difficulty navigating the rewards feature, and three of seven stated that the pie chart of points earned was hard to interpret. | ||

| 1c. Easily Digestible Education Content | Comments on the value of educational materials, nutrition information, and recipes. | Usefulness and Acceptability |

“I like that you guys give articles on preeclampsia and nutrition. I like articles. I would like to come back and read them. They're probably going to be very good. I like that.” “Would I be able to just put my questions in the search box and add a pop up? I would prefer it answer the question that I type instead of like hitting me with a whole bunch of different [ones]. I wouldn't like that because I'd be irritated.” “I think I'd like a video. A lot of people will be moving around and like, let's say, if they have something to listen to. I'd watch if it was short.” |

| Ease of use | All women self-navigated or guided the interviewer through the resources with ease. | ||

| 1d. Social support and competitive comparisons | Comments regarding connecting to a ‘friend’ group and engaging in a leaderboard incentive point competition |

Usefulness and Acceptability |

“I don't think I would want anybody else to be able to, like, log in to see certain things, right?” “It makes it more interesting because then I'm like, I want to beat my friends in that reporting. So, the competitive aspect of it, in my head it is pretty good. It's a lot of motivation.” “We could talk to somebody that is going through the same thing. Ask them how they are coping. It would be nice but not necessary.” |

| Ease of Use | One of nine showed difficulty navigating this feature | ||

| 1e. Affordability | Comments expressed regarding costs | Usefulness and Acceptability | “Will it be free? Because I've been downloading a few applications to like to track my pregnancy and keep up with certain things, but to access certain information from these apps, they want you to subscribe and pay.” |

| Ease of Use | N/A | ||

| |||

|

2a.Progress tracking and tailored feedback |

Comments on the data visualization graphs.

The real-time feedback pop ups specific to the participant's blood pressure input |

Usefulness and Acceptability |

“It is important for me to track my progress. There are times where my blood pressure could be high, and I don't feel anything. And I don't know. And there are other times where I do feel kind of funny, and I would like to track that. Like, how can I determine what I'm feeling? Does that mean that the pressure is high or low? That's kind of how I would do this.” “Before I got pregnant, I wasn't really aware of what was high or low for blood pressure because I never experienced this. But yeah, for those of us that do have these complications, knowing that it's in the normal range or high, we should call our provider. That's helpful for sure.” “…and one thing I know is that a lot of people do not have scales in their house.” |

| Ease of Use | Four women had some difficulty interpreting expected weight versus actual weight in the weight graph. | ||

|

2b. Prompts and Reminders |

Comments on notifications and reminders (e.g., reminder to take blood pressure) |

Usefulness and Acceptability |

“Will this application be giving me notifications like reminders when to take my blood pressure? Because sometimes I forget, and I procrastinate a lot.” “I would only want it when it is time for me to check it and then a two-minute reminder afterwards.” “It would be helpful if I could set my own [reminder] times.” |

| Ease of Use | Familiarity with types of mobile notifications they preferred. | ||

| |||

| 3. Bidirectional, informed communication | Comments regarding sending and receiving information from the provider | Usefulness and Acceptability |

“Like my blood pressure information when I enter it. I would want that to be relayed to my provider so they could keep track, and they could know.” “And my interaction with the app. Will the information that I put in be related to my providers. Can they access it?” |

| Ease of Use | Unable to test as electronic health record not integrated | ||

3.2.1. Theme 1 acceptability and usability

Willingness to use the application. All women reported a high acceptability and usability of the prototype's features. Seven navigated the application confidently and believed home monitoring would benefit both their and their baby's health. The SUS mean score of 81 ± 17, exceeding the U.S. adult population median, aligns with the qualitative findings (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of System Usability Scale (SUS) responses and scores in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in Newark, New Jersey, 2024 (N = 9).

| Mean ± SD |

Min-Max |

50th Percentile Reference Valueb ≥68 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total SUS Scorea | 81 ± 17 | 55–97 | |||

| SUS Response by Item n (%) |

Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neither agree or disagree | Agree | Strongly agree |

|

1 (11.) | 2 (22) | 6 (66) | ||

|

4 (44) | 5 (56) | |||

|

3 (33.) | 6 (67) | |||

|

6 (67) | 2 (22) | 1 (11) | ||

|

1 (11) | 5 (56) | 3 (33) | ||

|

4 (44) | 3 (33) | 2 (22) | ||

|

3 (33) | 6 (67) | |||

|

4 (44) | 4 (44) | 1 (11) | ||

|

1 (11) | 8 (88) | |||

|

6 (67) | 2 (22) | 1 (11) | ||

Abbreviations: SUS, system usability scale; HDP, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; SD, standard deviation, Min minimum, Max maximum.

Out of a total possible score of 0–100 and calculated by the raw score contributions from each item. Each item's score contribution will range from 0 to 4. For items 1,3,5,7 and 9, the score contribution is the scale position minus 1. For items 2,4,6,8 and 10, the contribution is five minus the scale position. The sum of the scores is then multiplied by 2.5 to obtain the overall value of SUS.

A score of ≥68 is considered a good score for the product.

Two women had trouble accessing the Just in Time™ URL, requiring the interviewer to share their screen while the woman verbally guided the navigation. This limited the interviewer's ability to assess usability fully in these two interviews. However, seven of the nine women demonstrated high ease of use with most of the application's features. All women were highly positive about the application's usability and expressed intent to engage with it.

Rewards and Incentives. All women responded favorably to the application's point-based rewards and incentive system. Four women indicated that they would use the application even without incentives, and they noted that this feature would increase daily engagement. One in seven women had difficulty navigating the rewards feature, and three found interpreting the graphic display of points earned challenging.

Easily Digestible Education Content. The educational resources were well regarded and viewed as trusted resources by all women. Four suggested presenting them as short videos over lengthy text, and three indicated they would not use the recipe section due to cultural food preferences, or time constraints.

Social Support and Competitive Comparisons. Half of the women who viewed the social support section valued a ‘friend group’ feature for support, while others expressed privacy concerns or a lack of interest. Opinions on the leaderboard feature were mixed, though all women liked the point tracking of their own progress.

Affordability. Echoing provider feedback, the women emphasized the importance of a low-cost digital application, stating that high cost could limit their accessibility.

3.2.2. Theme 2 tailored feedback for action planning

Progress Tracking and Tailored Feedback. Two women showed disinterest in tracking physical activity progress due to time constraints or skepticism about its benefits. Four expressed some difficulties in interpreting the graphical feedback on the weight graphs and the lack of home scales was identified as a barrier for weight monitoring. The women appreciated the tailored feedback based on BP input. Real-time feedback on abnormal BP readings was seen as a critical tool for guiding action steps and providing a safety net, as were the graphical displays informing BP trends over time. Tailored feedback helped guide action steps, such as rechecking BP, contacting their doctor, or seeking urgent care. Four women wanted feedback specific to their condition that aligned with the parameters set by their healthcare provider.

Prompts and Reminders. The women emphasized the challenges of managing HDP during pregnancy, especially while balancing work and family responsibilities. All women agreed that daily BP monitoring reminders via text messaging or push notifications would be helpful and preferred customizable reminder times rather than following a fixed daily schedule.

3.2.3. Theme 3 patient-provider communication

Bidirectional, Informed Communication. Women viewed the application as a beneficial tool for home monitoring, particularly for alerting providers to high-risk BP readings. Integration with the EHR was preferred as most women communicated with their providers through an online portal. One woman highlighted the desire for real-time provider monitoring and direct communication if their BP values fell outside the normal range. However, most women emphasized their role in action planning, noting that they would initiate a phone call to their provider if concerning BP trends emerged. While most prioritized BP monitoring, weight tracking communication to the provider was less of a priority for three participants.

3.3. Provider feedback

3.3.1. Optimizing patient-provider communication

Providers agreed that traditional BP home monitoring via pen-and-paper logs can be inefficient, frequently missing during appointments, and complicating treatment decisions. All emphasized the need for an integration with the EHR, as most women used it for communication and accessing test results. One provider stressed that abnormal BP results can necessitate emergency follow-up, highlighting the importance of having personnel monitor the data: “The human is what makes it work.”

3.3.2. Navigating care

Two providers noted challenges in accessing and navigating care during pregnancy and postpartum. One remarked, “The hard part is not the content of an application; it is getting access to care and staying in a system that is complicated and requires many transitions. Often pregnancy is the first healthcare experience of care for many patients.” “ ….especially postpartum when it is difficult to get on a bus with a newborn two weeks after delivery to check blood pressure.”

3.3.3. Insights on resources and digital application features

Providers valued the application's educational modules as a way to enhance limited clinic resources, particularly for nutrition and pregnancy guidance. Two recommended adding a “what to expect” section outlining appointments and tests throughout pregnancy and postpartum, noting it as “high-yield and an adjunct to nutrition access as it is otherwise not very available.” Additional features suggested by providers were glucose monitoring, fetal kick counts, and vaccination reminders. However, one provider found the multiple features confusing, questioning its focus: Do you want it to be a BP app, a nutrition app, or an education app?” Two providers advocated for simple, friendly language, such as “number of weeks pregnant” instead of “gestational weeks.” Tailored feedback based on specific diagnoses and pregnancy stages was strongly supported. Incentives and rewards were viewed favorably.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key findings

The findings of this study highlight the strong acceptability and usability of a digital health application designed for women managing HDP. Most women demonstrated good digital health literacy, with high SUS scores aligned with the qualitative theme of acceptability and usability. Women value tailored feedback and real-time prompts, particularly for blood pressure (BP) monitoring, and they recognize these features as essential for informed decision-making and timely action. While the application's social support features were generally well received, preferences varied based on individual considerations. A key finding among women was their current use of EHR and the need to integrate any health application to facilitate provider communication. These findings emphasize the importance of personalized, accessible, and interactive digital health solutions to support self-monitoring and provider engagement in managing HDP.

The qualitative results of this study align with previous usability research on pregnancy planning apps that have similarly employed person-centered approaches (Band et al., 2019; Rhodes et al., 2023; van den Heuvel et al., 2020) and uniquely examines internal and external factors influencing the acceptability and usability of behavior change features within a technology acceptance framework among women recruited from a low-income setting. Regarding Aim 1, seven of nine women demonstrated strong digital health literacy and reported high usability and perceived value of the application, reflected in above-average System Usability Scale (SUS) scores. These findings contradict several studies that link lower digital health literacy with socioeconomic factors such as education and income (Western et al., 2021; Whitehead et al., 2023). A systematic review noted that social and economic factors influence digital health literacy and, thus, the use of applications (Estrela et al., 2023). However, our findings showed strong acceptability and little variation in digital health literacy. For Aim 2, participants and providers reported strong expected engagement with features they perceived as valuable, particularly tailored feedback through in-application messages and reminders. Features such as physical activity and weight tracking were seen as less relevant, less relevant, or more challenging to navigate. These results mirror prior research indicating that usability and perceived value drive intended use (Band et al., 2019; Vijayakumar et al., 2022). Tailored feedback was especially appreciated for its motivational and action-oriented support, and providers emphasized opportunities to further individualize content based on reproductive status, diagnosis, and medical history. With respect to the third aim, the study identified key opportunities for improvement, including more digestible educational content, customizable preferences for social support and messaging, and better integration with provider communication. Both women and providers stressed the importance of linking the application with electronic health records (EHRs) to support timely, coordinated care, especially for sharing elevated blood pressure readings. These insights align with broader efforts to improve interoperability between digital health tools and EHR systems (Frid et al., 2022) and reinforce the importance of communication pathways that enhance clinical decision-making and patient trust.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study is its integration of a theoretical framework with a person-centered approach in a low socioeconomic group at increased risk for HDP. While the sample size is small, rigorous data analysis methods in independently coded data and intercoder reliability minimized researcher bias. However, the study has limitations. The small sample size makes generalizing findings to a larger population challenging. Self-selection bias may have influenced findings, as most women had chronic hypertension prior to pregnancy and were likely familiar with interpreting BP readings. In addition, women were already engaged in prenatal care and had access to personal digital devices, suggesting higher digital health literacy in this sample. There is also potential for social desirability bias or input bias due to study compensation. To mitigate this, the Think-Aloud approach (Fonteyn et al., 1993) encouraged women to freely discuss barriers and facilitators as they navigated the prototype's screens. Additionally, the DHLS may not fully capture digital health literacy given the diverse and multidimensional ways individuals interact with health information through online platforms such as social media. Future studies of digital health literacy may benefit from more nuanced, competency-based assessments, such as those described by van der Vaart and Drossaert (van der Vaart and Drossaert, 2017).

4.3. Implications for practice

Further exploration of digital health literacy and person-centered design in mHealth applications among women in low resource settings is needed. User experiences with digital health tools directly impact engagement and health outcomes. Positive interactions encourage continued use and benefits, while negative experiences can lead to frustration, disengagement, and missed care opportunities. The study findings support the use of tailored, just-in-time messaging and point to future opportunities for integrating generative artificial intelligence to enhance personalization and scalability in HDP management.

5. Conclusions

Our study findings indicate a high acceptability and usability of a digital application for managing HDP and supporting home blood pressure monitoring among both pregnant and postpartum women with diagnosed HDP, as well as their providers in a low-income urban setting. Participants demonstrated above-average digital health literacy and responded positively to the application's behavior change features, including tailored feedback, educational content, and reminders. Providers also recognized the potential of digital tools to address the limitations of traditional pen-and-paper monitoring. These insights highlight the importance of person-centered, contextually grounded design in developing effective mHealth solutions for underserved populations.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jennifer Wills: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Laura Byham-Gray: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Pamela Rothpletz-Puglia: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis. Tenzin Sangmo: Project administration, Data curation. Todd Rosen: Writing – review & editing. Shauna Williams: Writing – review & editing. Mafudia Suaray: Writing – review & editing. Shristi Rawal: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Funding

This research was supported by the New Jersey Health Foundation, Award ID AWD00009584.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Shirsti Rawal reports financial support was provided by New Jersey Health Foundation. Shristi Rawal reports a relationship with New Jersey Health Foundation that includes: funding grants. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank M. Rager for her support in this project's work, Dr. Bailey for reviewing the manuscript, I. Nkrumah for his support in the recruitment efforts, and R. McCoy for her graphic design of the figures.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Wills, Email: jlw374@shp.rutgers.edu.

Laura Byham-Gray, Email: byhamgld@shp.rutgers.edu.

Pamela Rothpletz-Puglia, Email: rothplpm@shp.rutgers.edu.

Tenzin Sangmo, Email: ts1153@sph.rutgers.edu.

Todd Rosen, Email: rosenti@rutgers.edu.

Shauna Williams, Email: williash@njms.rutgers.edu.

Mafudia Suaray, Email: mafudia.suaray@rutgers.edu.

Shristi Rawal, Email: shristi.rawal@rutgers.edu.

Appendix A. Interview Guide for Healthcare Providers

What is your experience and perspective about using mobile applications to support your patients with high blood pressure during pregnancy?

-

•

Do you or your patients use them? If so, what do you consider as benefits? If not, do you think it could be useful?

-

•

What do you think are barriers to using a mobile applications for this condition? Or mobile health applications in general?

-

•

How do you think mobile applications could be feasible to use in the management of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy?

-

•

How do you think mobile applications will impact the quality of care?

< Interviewer will give 10 min presentation on the proposed application design, features and function>.

What do you think about the proposed mobile application based on this presentation?

-

•

General opinions?

-

•

What do you like and what you did not like?

Do you think this mobile application will be useful for women with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy?

-

•

What aspects of the application do you think will be useful?

What do you think of the features included in the mobile application? (List and ask feedback on each feature).

What about the educational topics/modules included in the mobile application? (List and ask feedback on each topic)

-

•

Do you think these modules could be useful to women with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy?

-

•

Was it missing anything?

Lastly, would you like to see any more features in the mobile application?

And do you have any further suggestion on how to improve this application?

Thank you for your time. Version #: 03 7/25/2023

Appendix B. Interview Guideline for Patients

“Thank you for sitting with us today and giving us your time and opinions on a mobile application for women with pregnancy hypertension. We appreciate your thoughts very much. You will help make this application better.”

This interview will take about 1 h to complete. I'll ask you some questions, show you a video introduction of the application and then you can try out the application yourself and give us your feedback and opinions.

If you feel uncomfortable or do not want to continue, just let me know and you can choose to leave the session.

Do you have any questions before we begin? Do I have your permission to record? I'll start with a few questions.

DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION (1 min)

-

1.What is your age?

-

a)Between 18 and 25 years

-

b)Between 26 and 33 years

-

c)Between 34 and 40

-

d)Older than 40 years

-

a)

-

2.How would you describe yourself

-

a)American Indian or Alaska Native

-

b)Asian

-

c)Black or African American

-

d)Hispanic or Latino

-

e)Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander

-

f)White

-

a)

-

3.Are you currently pregnant?

-

a)Yes/No

-

a)

-

4.

Which week of gestation are you in?

-

5.

Which type of hypertension or high blood pressure did your doctor tell you have?

-

a)

Gestational hypertension

-

b)

Chronic Hypertension

-

c)

Preeclampsia

-

d)

A combination of the above

Section 1 Digital Health Literacy Questionnaire

SECTION 2 HDP VIDEO (7 min)

I am going to show you a 7-min video of the digital application to introduce you to it. Afterwards, you will have a chance to explore it yourself and I will ask that you give your thoughts and opinions on its features. I will turn off the recording for this section.

[interviewer turn off recording].

SECTION 3 USER'S USE OF THE PROTOTYPE

Next, I will ask you to use the mobile application you just viewed. Since this is a prototype, some fields have been filled in and some places in the application are not active. Please open the link that I sent in the chat (or sent via email) and share your screen [if applicable]. As we are reviewing the application, we ask that you think aloud about what you are viewing. Describe what you are doing, where you are looking and why you are looking at these areas. Please share if there is something you dislike or are confused about any of the components. We may remind you to think aloud at different times during the session. There are no right or wrong answers to what we're asking. We're genuinely interested in your thoughts and opinions about the site. It doesn't matter if they're negative or positive.

[User opens the prototype link]. Please ask questions at any time. Prompt user to log into the application. Application dashboard displays.

Task 1 Blood Pressure Monitoring

Let's say you want to add your blood pressure results for this morning and view your blood pressure trend over time. Where would you go to log your BP numbers? Go ahead and click in that space.

-

•

Was the prompt helpful in interpreting the results? What would you do if you received that feedback? Where would you go to see yesterday's BP numbers? How about your BP each week?

Please remember to think aloud.

-

•

How would you interpret this graph?

-

•

What do the two BP values indicate to you?

-

•

How would you use the information if at all?

-

•

What would you do if you received that feedback?

-

•

How easy or difficult was it to identify your personal BP numbers?

-

•

Would you change how the graph displays your BP numbers? If so, how?

-

•

Is there any other information you would like to see on this or removed from the page?

| User actions | Interviewer Observations |

|---|---|

| Navigates to BP | |

| Enters BP > submit | |

| Goes to My Graphs | |

| Explores graph views | |

| Interpret BP |

Task 2 Weight Monitoring

Let's say you want to add your weight for this morning and view your weight trend over time. Where would you go to log your weight? Remember to think aloud.

-

•

How would you interpret this graph?

-

•

How would you use this information?

-

•

How easy or difficult was it to identify your weight gain trend?

-

•

Would you change how the graph displays your weight? If so, how?

-

•

Is there any other information you would like to see on this or removed from the page?

| User actions | Interviewer Observations |

|---|---|

| Navigates back to home page | |

| Navigates to weight page | |

| Adds weight into proper box | |

| Interprets weight gain graph | |

| Explores daily and weekly views |

Task 3 Resources > Dictionary > Articles > Additional Resources

Now let's say there is a term you are unfamiliar with that your doctor said today. Where would you go to find the definition of the term? Please think aloud.

-

•

How would you use this information?

-

•

Please explore other sections and let me know your thoughts and opinions

-

•

Is there any other information you would like to see in this section?

| User actions | Interviewer Observations |

|---|---|

| Navigates back to home page | |

| Navigates to Resources > dictionary | |

| Explores other topic Articles | |

| Explores Additional Resources |

Task 4 Physical Activity

Now let's say your doctor has encouraged you to get daily physical activity and you are doing so by trying to get in 4000 steps per day. Where would you go to see your daily steps. Remember to think aloud.

-

•

How would you use this information?

-

•

Is there any other information you would like to see on this graph?

-

•

Would you prefer to see your physical activity information any differently?

| User Actions | Interviewer Observations |

|---|---|

| Navigates back to home page | |

| Navigates to physical activity | |

| Interprets step graph |

Task 5 Score Board/Points Earned/Friends

This program will reward the user points based on self-monitoring activities, viewing the lessons and resources. Please navigate to the Score Board. Remember to think aloud. Please explore the ways you can earn points, redeem points and connect with ‘friends.’

-

•

How easy or not easy was it to identify your points earned and how to earn points?

-

•

BP log, PA, nutrition Resources

-

•

How important is points and being able to redeem gift cards to you?

-

•

How does the leader board appeal to you?

-

•

Comment on the feature of seeing other users point score. Does it appeal? If so, how?

-

•

Would you use adding the ‘friend’ feature? Why or why not?

-

•

Is there anything you would change about this section of the application?

| User Actions | Interviewer Observations |

|---|---|

| Use the back button to get to Score board? | |

| Do they read How Do I Earn Points? | |

| Navigate to their points board? | |

| Did they navigate to the leader board? | |

| Did they navigate to how to redeem points? | |

| Explored friends section (leader board) |

Task 6 Nutrition > Recipes and Nutrition and Physical Activity Modules

Let's say you are looking for further information about nutrition and physical activity during pregnancy. Where would you go to find that information?

-

•

How would you use the information?

-

•

Is there any other information you would like to see in this section?

-

•

How easy or not easy was it to find the educational modules?

| User actions | Interviewer Observations |

|---|---|

| Navigates back to home page | |

| Navigates to Nutrition | |

| Scrolls through the recipes | |

| Scrolls through the Nutrition and PA |

Task 7 Other features of the application; Appointments and Profile

Please feel free to explore other areas of the application and please think aloud as you do.

User comments:

Task 8 Text message (web application) or push notifications (native mobile).

For women with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, the recommendation is to take two BP measurements per day, in the morning and the afternoon. The application will send push notification/text messages to help remind you to take your BP in the morning and in the afternoon, and to record and monitor your weight and PA. Would text messages or push notification reminders be an interest to you? Do you have a strong preference for either one? How many reminder messages are too many?

-

1.

Twice a day, (morning/afternoon) every day with a follow up reminder if you don't take your BP that morning or that afternoon?

-

2.

Twice a day (morning/afternoon) and no follow up reminders?

-

3.

Would you prefer to customize the time of day to receive the BP reminders? For example; between 8 am and 9 am and between 5 pm and 6 pm.

SECTION 4 FOLLOW UP QUESTIONS

Thank you for exploring the prototype with me and providing me with your thoughts and opinions. We will use your feedback to make this application better. You may close out of the link. May I ask you some follow up questions?

-

(1)

What do you think of the application?

-

(2)Which features of the application, if any, do you think will be useful in managing hypertension during pregnancy? Which features would be unnecessary? [Interviewer be prepared to bring up the prototype]

-

a.Feedback of the BP readings and communication with your clinical team

-

b.Regular self-monitoring of BP

-

c.Reminders to check your BP

-

d.Graphs of BP over time

-

e.Graphs of weight gain over time

-

f.Dictionary of terms

-

g.Connection to your medical record

-

h.Incentives to weigh and monitor BP

-

i.The educational resources for diet, exercise, and healthy pregnancy – anything missing?

-

j.The points earned in comparison to others?

-

k.Social support of others using the application

-

a.

-

(3)

Any input on the images, font, color on the application or other content?

-

(4)

Is there anything you would change about the layout of the website to help you find information?

-

(5)Would this application help and support you to monitor your hypertension during pregnancy versus not having this application?

- If no, what would help?

- What would stop you from using this application?

-

(6)

Would this application help you decide when to follow-up with your OBGYN? If no, what would help?

Section 5 System Usability Scale Questionnaire

Stop recording. Thank the user for their time and opinions

Appendix C. Section 1 digital health literacy scale questionnaire (5 min)

-

(1)How often do you look for answers to health questions on the Internet? Make one choice.

-

a.Never

-

b.Rarely (1–2 times a month)

-

c.Sometimes (3–4 times a month)

-

d.Often (5 or more times a month)

-

a.

-

(2)Which of the following best describes your familiarity with technology?

-

a.I know little about technology and do not use technical products very often

-

b.I'm comfortable with technology but will only buy new technology items after they have

-

c.been out for a while, and I've seen other people around me test them

-

d.I'm excited to try new technology and buy new products that come out before others

-

e.around me buy the product.

-

f.I'm a technology enthusiast and always have the newest technology products right when

-

g.they come out.

-

a.

-

(3)Which statements describe your relationship with technology products? Choose all that apply

-

a.When a new technology product is released, I am the first one to buy it

-

b.I know more about technology products than others around me

-

c.I have used more technology products than others around me

-

d.When friends and family buy new technology products, they ask me which one to buy

-

e.When using technology products, I use more of the features of the product than other

-

f.people around me

-

g.I regularly visit websites or subscribe to newsfeeds or magazines to get the most updated

-

h.technology information

-

a.

Scoring for question 3:

High level technology literacy 3+ statements.

Mid level technology literacy: 1–2 statements.

Low level of technology literacy: 0 statements.

Appendix D. Section 5 system usability scale questionnaire

We are almost finished. I have 10 questions I would like to ask you to rate on your level of agreement. Rate each of the following from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neither agree or disagree | Agree | Strongly agree |

-

1.

I think that I would like to use this application frequently.

-

2.

I found the application unnecessarily complex.

-

3.

I thought the application was easy to use.

-

4.

I think that I would need the support of a technical person to be able to use this application.

-

5.

I found the various functions in this application were well integrated.

-

6.

I thought there was too much inconsistency in this application.

-

7.

I would imagine that most people would learn to use this application very quickly.

-

8.

I found the application very cumbersome to use.

-

9.

I felt very confident using the application.

-

10.

I needed to learn a lot of things before I could get going with this application.

SUS Scoring

SUS yields a single number representing a composite measure of the overall usability of the.

system being studied. Scores for individual questions range from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree. For items 1,3,5,7,and 9 (odd-numbered questions) the score contribution is the scale position minus 1. For items 2,4,6,8 and 10 (even-numbered questions), the contribution is 5 minus the scale position. Multiply the sum of the scores by 2.5 to obtain the overall value of SUS. SUS scores have a range of 0 to 100.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Abraham C., Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008;27(3):379–387. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albadrani M., Tobaiqi M., Al-Dubai S. An evaluation of the efficacy and the safety of home blood pressure monitoring in the control of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in both pre and postpartum periods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23(1):550. doi: 10.1186/s12884-023-05663-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Band R., Hinton L., Tucker K.L., Chappell L.C., Crawford C., Franssen M., Yardley L., et al. Intervention planning and modification of the BUMP intervention: a digital intervention for the early detection of raised blood pressure in pregnancy. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019;5:153. doi: 10.1186/s40814-019-0537-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter J., Sandall J., Shennan A.H., Tribe R.M. Mobile phone apps for clinical decision support in pregnancy: a scoping review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2019;19(1):219. doi: 10.1186/s12911-019-0954-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K.H., Seow K.M., Chen L.R. Progression of gestational hypertension to pre-eclampsia: a cohort study of 20,103 pregnancies. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2017;10:230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin M.B., Wells B.M., Doe E.M., Strother A.M., Tarasiewicz M.E.B., Via E.R., Farias-Eisner R., et al. Understanding health disparities in preeclampsia: a literature review. Am. J. Perinatol. 2024;41(S 01):e1291–e1300. doi: 10.1055/a-2008-7167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989;13(3):319–340. doi: 10.2307/249008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy J., Cairns A.E., Richards-Doran D., Van’t Hooft J., Gale C., Brown M., McManus R.J. International collaboration to harmonise outcomes for pre-eclampsia. A core outcome set for pre-eclampsia research: an international consensus development study. BJOG. 2020;127(12):1516–1526. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S., Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrela M., Semedo G., Roque F., Ferreira P.L., Herdeiro M.T. Sociodemographic determinants of digital health literacy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2023;177 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2023.105124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonteyn M.E., Kuipers B., Grobe S.J. A description of think aloud method and protocol analysis. Qual. Health Res. 1993;3(4):430–441. doi: 10.1177/104973239300300403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frid S., Maria Angeles Fuentes E., Grau-Corral I., Amat-Fernandez C., Montserrat Muñoz M., Xavier Pastor D., Lozano-Rubí R. Successful integration of EN/ISO 13606–standardized extracts from a patient Mobile app into an electronic health record: description of a methodology. JMIR Med. Inform. 2022;10(10) doi: 10.2196/40344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganapathy R., Grewal A., Castleman J.S. Remote monitoring of blood pressure to reduce the risk of preeclampsia related complications with an innovative use of mobile technology. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2016;6(4):263–265. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi P., Garcia M., Fenton J. U.S. Department of Commerce; Gaithersburg, MD: 2017. Digital Identity Guidelines.https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-63-3.pdf Retrieved from chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/ [Google Scholar]

- Harris C., Straker L., Pollock C. A socioeconomic related 'digital divide' exists in how, not if, young people use computers. PLoS One. 2017;12(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffert L.R., Clancy C.R., Bateman B.T., Bryant A.S., Kuklina E.V. Hypertensive disorders and pregnancy-related stroke: frequency, trends, risk factors, and outcomes. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;125(1):124–131. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J. The system usability scale: past, present, and future. Int. J. Human–Comput. Interaction. 2018;34(7):577–590. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2018.1455307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S., Yardley L., West R., Patrick K., Greaves F. Developing and evaluating digital interventions to promote behavior change in health and health care: recommendations resulting from an international workshop. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017;19(6) doi: 10.2196/jmir.7126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson L., Pennings J., Sommer E., Popescu F., Barkin S. A 3-item measure of digital health care literacy: development and validation study. JMIR Form. Res. 2022;6(4) doi: 10.2196/36043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen J., Landauer T. Paper presented at the proceedings of ACM Interchi ’93 conference, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. 1993, April 24. A mathematical model of the finding of usability problems. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis S., Roussel J., Bosson J.L., Kern J.B. Use of smartphone health apps among patients aged 18 to 69 years in primary care: population-based cross-sectional survey. JMIR Form. Res. 2022;6(6) doi: 10.2196/34882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pealing L., Tucker K.L., Fletcher B., Lawley E., Chappell L.C., McManus R.J., Ziebland S. Perceptions and experiences of blood pressure self-monitoring during hypertensive pregnancy: a qualitative analysis of women’s and clinicians’ experiences in the OPTIMUM-BP trial. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2022;30:113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2022.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes A., Pimprikar A., Baum A., Smith A.D., Llewellyn C.H. Using the person-based approach to develop a digital intervention targeting diet and physical activity in pregnancy: development study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023;7:1. doi: 10.2196/44082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel J.F.M., Lely A.T., Huisman J.J., Trappenburg J.C.A., Franx A., Bekker M.N. SAFE@HOME: digital health platform facilitating a new care path for women at increased risk of preeclampsia – a case-control study. Pregnancy Hypertension. 2020;22:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vaart R., Drossaert C. Development of the digital health literacy instrument: measuring a broad Spectrum of health 1.0 and health 2.0 skills. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017;19(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.6709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumar N.P., Neally S.J., Potharaju K.A., Curlin K., Troendle J.F., Collins B.S., Powell-Wiley T.M., et al. Customizing place-tailored messaging using a multilevel approach: pilot study of the step it up physical activity Mobile app tailored to neighborhood environment. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2022;15(11) doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.122.009328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Western M.J., Armstrong M.E.G., Islam I., Morgan K., Jones U.F., Kelson M.J. The effectiveness of digital interventions for increasing physical activity in individuals of low socioeconomic status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021;18(1):148. doi: 10.1186/s12966-021-01218-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead L., Talevski J., Fatehi F., Beauchamp A. Barriers to and facilitators of digital health among culturally and linguistically diverse populations: qualitative systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023;25 doi: 10.2196/42719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills J., Sangmo T., Suaray M., Williams S., Rothpletz-Puglia P., Rawal S. Paper presented at the American Society of Nutrition; Chicago IL: 2024. User-Centered Development of a Mobile Application for Managment of Hypertension Disorders of Pregnancy: A Study Protocol. [Google Scholar]

- Yardley L., Morrison L., Bradbury K., Muller I. The person-based approach to intervention development: application to digital health-related behavior change interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015;17(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.