Abstract

Changes in collagen orientation and distribution on the corneas lead to the development of diseases characterized by progressive thinning, such as keratoconus. Part of people diagnosed with keratoconus require a corneal graft, which has availability as a major limiting factor. In this scenario, new approaches have been tested to obtain substitute tissues. Porcine cornea has been receiving increasing attention due to its ease of obtaining, biomechanical properties similar to those of human tissue and lower antigenicity. Based on this, the objective of this study was to evaluate the biocompatibility of porcine stroma decellularized by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) through interlamellar implantation in rabbit corneas. The obtained results showed that the lenticule intrastromal implantation was successfully performed and did not elicit rejection. Furthermore, the implanted stroma was able to promote an increase in the thickness of the host cornea. Microscopic analyses revealed that the tissue was well-adhered and the collagen fibrils were more aligned on its periphery. Therefore, it is concluded that the implantation of decellularized porcine stroma occurred satisfactorily and represents a promising alternative to replace human tissue.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The corneal stroma is a highly organized 3-dimensional meshwork of collagen fibrils surrounded by proteoglycans [1]. Collagen type I lamellae is the most abundant in this tissue followed by other collagen types that are also present such as V and VI [2]. Proteoglycans are proteins that play an important role in regulating interfibrillar collagen spacing and epithelial cell behavior [3].

It is well-known that the stroma layer constitutes over 90% of the corneal diameter. In some diseases of the cornea, an increase in corneal thickness could reflect an enhancement of water influx and consequently corneal edema. On the other hand, a decrease in corneal thickness is observed in many eye dystrophies, which is believed to be attributed to loss of stroma tissue and this can influence the physiological functions of the cornea [2, 4].

In some corneal diseases, there is an absence or a limited production of proteoglycans, interfering in the collagen fibrils assembly. Thus, the 3-dimensional matrix formed is distorted and collagen is unevenly distributed, which facilitates the development of corneal ectatic disorders [5].

Ectatic corneal disorders are pathologies characterized by progressive corneal thinning which leads to a loss of vision [6]. The most prevalent corneal disease of this group is keratoconus, a condition in which the cornea becomes a conical shape because of stromal corneal thinning, as a consequence of loss of collagen fibril orientation [7]. This disorder affects between 0.2 and 4790 per 100,000 persons and some patients need a corneal transplant (~10–20%) [7–9]).

Interlamellar keratoplasty has become a widely used technique in the treatment of patients with keratoconus due to faster recovery and minor complications [10]. However, in most parts of world, the supply of donated human cornea is insufficient for demand [11]. In this scenario, new approaches have been tested for the obtention of materials or tissues that could replace the cornea. Porcine cornea is receiving increasing attention due to its easiness in obtaining, similar biomechanical properties to human tissue and lower antigenicity [12, 13]. These corneas are prepared through physical, chemical, and/or biological agents aiming to remove cellular components and immunogens to minimize the immune response, without losing their integrity [12, 14, 15].

Previous studies have reported the successful implantation of the decellularized porcine cornea in rabbits’ eyes and evaluated their potential use as a corneal tissue substitute [14, 16]. However, these studies used full-thickness corneas, and sometimes, techniques of implantation that require sutures in the cornea [14, 17, 18].

Nevertheless, with the technology emerging from femtosecond laser, it became possible to extract a small corneal stroma lenticule that, along with the interlamellar keratoplasty technique, could provide a corneal thickness correction to patients with a high grade of keratoconus and fewer complications [19, 20].

Based on this, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the porcine stroma decellularization by many chemical agents and subsequently their biocompatibility into an intrastromal pouch on rabbit corneal stroma.

Methods

Preparation of porcine corneal stroma

Fresh porcine eyes were obtained from a local slaughterhouse (Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil). After, the corneal flap was prepared using a biopsy trephine by a circular central wound of 6.5 mm in diameter and 200 µm in depth. The dissection of the corneas was performed to obtain a corneal layer constituted only by corneal stroma.

Decellularization of porcine corneal stroma

Tissues were washed in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) 0.15 M, pH = 7.2, and divided into five groups (n = 20, per group), according to the decellularization solution used: 0.1% w/v sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1% w/v SDS, 1.5 M NaCl or 1% w/v Triton-X. Also, a fifth group with native stroma was included.

Initially, tissues were incubated in the decellularization solution under agitation for 24 hours (h) at room temperature. After, rinsed with PBS solution for 90 min at 4 °C. At each wash cycle (30 min), the PBS was replaced. In the end, the stroma was maintained for another 72 h in PBS solution (under agitation) at 4 °C. PBS was replaced every 24 h.

For control (native group), the tissues were incubated at room temperature for 24 h and they were maintained for addional 72 h (under agitation) at 4 °C.

Hydration and transparency observations of decellularized porcine corneal stroma

After the decellularization process, excess fluid of the corneal stroma was removed and the tissues were weighed (Wi) and transferred to a vacuum desiccator for 24 h. Then they were weighed again (Wf) and the difference of mass was calculated according to the following equation (n = 8):

| 1 |

Where:

Wi refers to the initial weight.

Wf to final weight.

To evaluate the transparency, the tissues were rehydrated in PBS for 30 min and photographed. Sequentially, they were dehydrated with glycerol 100% (v/v) (Sigma Aldrich St. Louis, MO. USA) for 10 min and registered over the black letter “A” on white paper, to assess light transmittance (n = 3).

Histological analysis

Corneal stromas were fixed in Davidson’s solution (95% ethyl alcohol v/v formaldehyde/glacial acetic acid/distilled water) for 24 h and transferred to a 70% (v/v) alcohol solution for another 24 h. Tissues were dehydrated with serial ethanol cycles (70% to absolute), followed by clarification in xylol, and then embedded in paraffin. Samples were cut with a thickness of 5 μm added to the slice and submitted to the following staining: hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to observe histopathological changes, periodic acid Schiff (PAS) for glycoproteins, alcian blue for proteoglycans, and Masson’s trichrome (T. Masson) to assess the distribution of collagen. From T. Masson’s micrographs and using the ImageJ® software (version 1.50i, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) the percentage of collagen in each sample was quantified (n = 6, per group) as described before by [21].

Immunostaining

Nuclear labeling was performed using the Hoechst 33258 probe (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Paraffinized slides (n = 3) were obtained (as described before) and a series of washes were performed with xylene and, later, with alcohol, to remove the paraffin present in the slide. Sections were washed in PBS three times for 5 min/each, followed by a final rinse with distilled water [22]. The sections were incubated with Hoechst 33258 (1 µg/mL; Sigma) in PBS for 20 min to mark the nuclei. Then, the slides were washed 3 times with PBS solution for 10 minutes each cycle.

For observation and analysis, a confocal laser scanning microscope LSM 880 located at CAPI/UFMG was used. Photographs were taken using an objective lens with 20× magnification. The Hoechst probe was excited at 490 nm with an emission at 526 nm. The number of cell nuclei in the corneal stroma was determined by ImageJ® software (version 1.50i, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The sections were chosen randomly from the central part of the stroma.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Samples were fixed by immersion for at least 12 h at room temperature in Modified Karnovsky’s (2.5% glutaraldehyde and 1% formaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.2). After, they were maintained in sodium cacodylate buffer 0.1 M, pH 7.2 (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MA) for 12 h. Next, uranyl acetate (2% uranyl acetate in deionized water) was used for counterstain followed by dehydration with increased concentrations of ethanol (70%, 80%, 90%, and 100%). The samples were included in Epon resin (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MA) and ultrathin sections with a thickness of 70 nm were obtained (ultramicrotome, Leica Microsystems) and placed over a 200-mesh copper screen. Slices were counterstained with Reynold’s lead citrate solution for 10 min and then examined with a transmission electron microscope (Tecnai G2-12-SpiritBiotwin FEI Company) localized at UFMG Microscopy Center with an acceleration voltage of 120 kV. The images were captured by a charge-coupled device camera. Semithin sections of 1 μm were then stained with toluidine blue 0.1% to identify more precisely the observed area.

Animals

New Zealand White female rabbits with six-week-old and approximately 2 kg in weight were obtained from the Experimental Farm of UFMG and housed under standard conditions according to the guidelines of the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and the study protocol that was approved by the Ethics Committee in Experimental Animals of UFMG (Protocol n° 206/2022).

Corneal transplantation by interlamellar keratoplasty

Lenticule of intrastromal corneal tissue was cut into approximately 6.5 mm in diameter and 106 µm of thickness, which was further collected and stored in Balanced Salt Solution (BSS; Serumwerk Bernburg AG, Bernburg, Germany) at −10 °C.

The animals were randomly divided into 2 experimental groups (n = 6/each group). In the first group, the rabbits were submitted to surgical procedure and received an insertion of the decellularized lenticule by SDS 1% method (named as lenticule). In the second group, the animals underwent the same procedure without the insertion of the lenticule (surgery group). For each animal, only the right eye was operated, and the left eye served as the control and was representative of a healthy eye (control group).

For the procedure, rabbits were anesthetized via intramuscular injection of 3 mg/Kg of xylazine hydrochloride and 22 mg/Kg of ketamine hydrochloride, and the eyes were anesthetized with a drop of 0.5% proxymetacaine chloride.

For the insertion of the lenticule, it was necessary to create a stromal flap with 100 µm thick, 7.5 mm long, and 18 mm in diameter. The interface between the margins of the obtained flap was then separated to produce a stromal pocket through a 4 mm incision. Postoperatively, the eyes were treated with tobramycin and dexamethasone ointment three times a day for 1 week.

Slit lamp photography and optical coherence tomography (OCT)

All the animals were observed at least once a day throughout the study period to monitor the incision site. To evaluate the clinical grading of lenticule haze, the opacity was classified based on a method reported by Fantes [23] (Table 1):

Table 1.

Scoring for lenticule opacity evaluation

| Score | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | Completely clear cornea |

| 0.5 | Trace haze seen with careful oblique illumination |

| 1 | Mild obscuration of iris details |

| 2 | A more prominent haze not interfering with visibility of fine iris details |

| 3 | Moderate obscuration of the iris and lens |

| 4 | Complete opacification of the stroma in surgery area |

Haze grading was performed in a blinded manner by three independent observers at 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after interlamellar keratoplasty.

To quantify the lenticule haze grading, slit-lamp photographs were registered under standardized conditions at 14 and 28 days after interlamellar keratoplasty employing a biomicroscope (Apramed HS5, São Carlos, Brazil) coupled to a Canon EOS Rebel T5 digital camera, (Canon, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) for image acquisition. The photographs were converted to 8-bit grayscale images and a circle corresponding to the lenticule area was converted to pixels using ImageJ® software (version 1.50i, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) as described previously by [24].

After 28 days, visualization of the corneal cross-sectional was performed using Spectralis HRA® + OCT device (Heidleberg Engineering, Germany). Imagens of lenticule or interlamellar keratoplasty area were obtained by vertical volumetric mode under the automatic real-time and high resolution (HR) mode with the highest potential and 30° lens. Obtained images were analyzed using ImageJ® software.

At the end of the experiment, animals were euthanized with an overdose of sodium thiopental (90 mg/kg; iv). The eyes were enucleated and prepared for histological analysis and TEM (as described before).

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SD. Data were considered statistically significant when p was less than 0.05. GraphPad Prism version 8.4.2 was used for all graphs and statistical analyses.

The comparison between two groups was analyzed using non‐paired two‐tailed Student’s t-test. The comparison between multi-groups was done using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey.

Results

Hydration and transparency of decellularized stroma

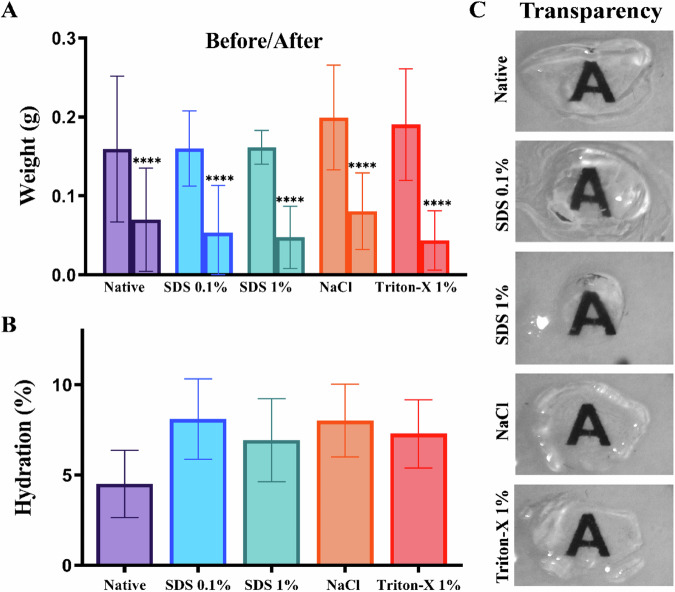

The evaluation of the hydration percentage was performed after the respective decellularization processes. It was possible to observe that all groups presented significant weight variation (Fig. 1A) and the decellularized groups showed higher percentages of hydration than the native group (4.51%). Among these groups, SDS 0.1% presented a higher percentage of hydration (8.1%) followed by the stroma treated with NaCl (8.01%), 1% Triton-X 1% (7.28%), and SDS 1% (6.92%), respectively (Fig. 1B). No statistical differences were found between percentages of hydration.

Fig. 1.

Measurement of weight variation and hydration of stromas after the decellularization process. The graph shows the initial weight and final weight in grams (A) or Hydration percentage (B) in the native, SDS 0.1%, SDS 1%, NaCl, and Triton-X 1% groups. C Representative images from each group after dehydration with glycerol. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 8)

The stroma had their transparency and macroscopic structure evaluated by photographs. It was possible to observe that, when compared with the control group (Fig. 1C), decellularized groups maintained their macroscopic structure. Also, after dehydration with 100% glycerol (v/v), all groups showed higher transparency.

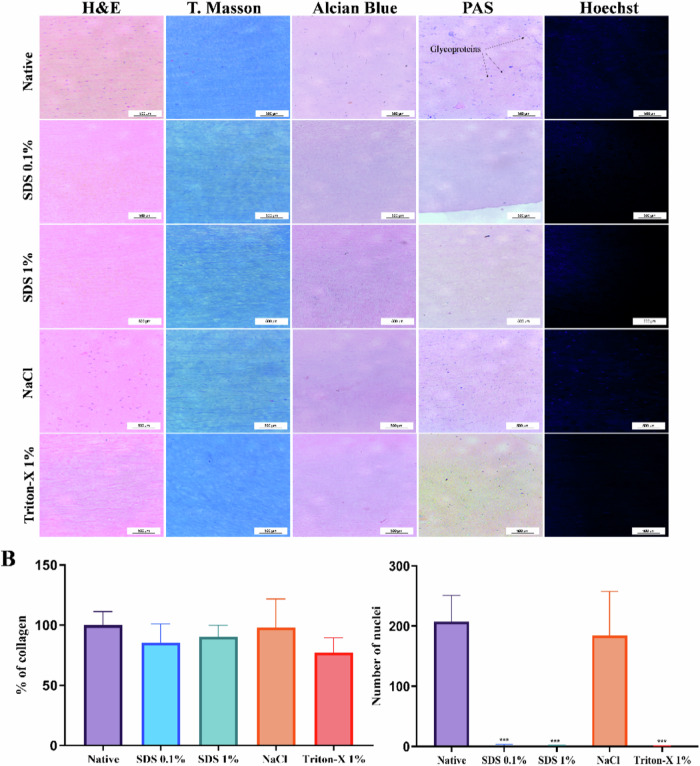

Histological analysis and immunofluorescence

H&E images showed that almost all cells were eliminated in the corneal stromas treated with SDS 0.1%, SDS 1% and Triton-X 1% (Fig. 2A) while many keratocyte cells were observed in the group treated with NaCl.

Fig. 2.

Microscopic assessments of decellularized treatments in porcine stromas. A Representative images of histological section with hematoxylin and eosin, Masson’s Trichrome (T. Masson), Alcian Blue, and Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) stainings show the effects of decellularization processes. B All the processes changed the collagen fiber, mainly in stroma treated by Triton-x. C In Hoechst 33258 marked images, it is demonstrated that stroma prepared by SDS 0.1%, SDS 1%, and Triton-X 1% have reduced number of nuclei, while the NaCl treatment presented intact nuclei visible, similar to the native group. Scale bar: 50 µm. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 6)

In Masson’s trichrome staining, all decellularization treatments slightly changed collagen fibril structures, mainly observed in the Triton-X 1% group that presented collagen reduction of 22.71% + 10.58% in comparison to the stromas of the native group. Besides that, no significant differences in the percentage of collagen were observed between the groups (Fig. 2B). Alcian blue staining reveals rather weak staining in the stroma of all groups. Otherwise, glycoproteins were identified (arrows) in native stroma by PAS staining.

Hoechst 33258 was used to stain the nucleus in blue. The average of counted nucleic acid particles in the corneal stroma is shown in Fig. 2C. The results revealed a significant reduction of nuclei in SDS 0.1%, SDS 1%, and Triton-X 1% decellularized stroma, when compared to the native group (p < 0,001). These processes eliminate respectively: 99.35 + 0.85, 99.67 + 0.42, and 99.83 + 0,21 of nuclei in stromas. In NaCl group, although there was a decrease in the number of nuclei detected, an average similar to the native group remained after the decellularization process.

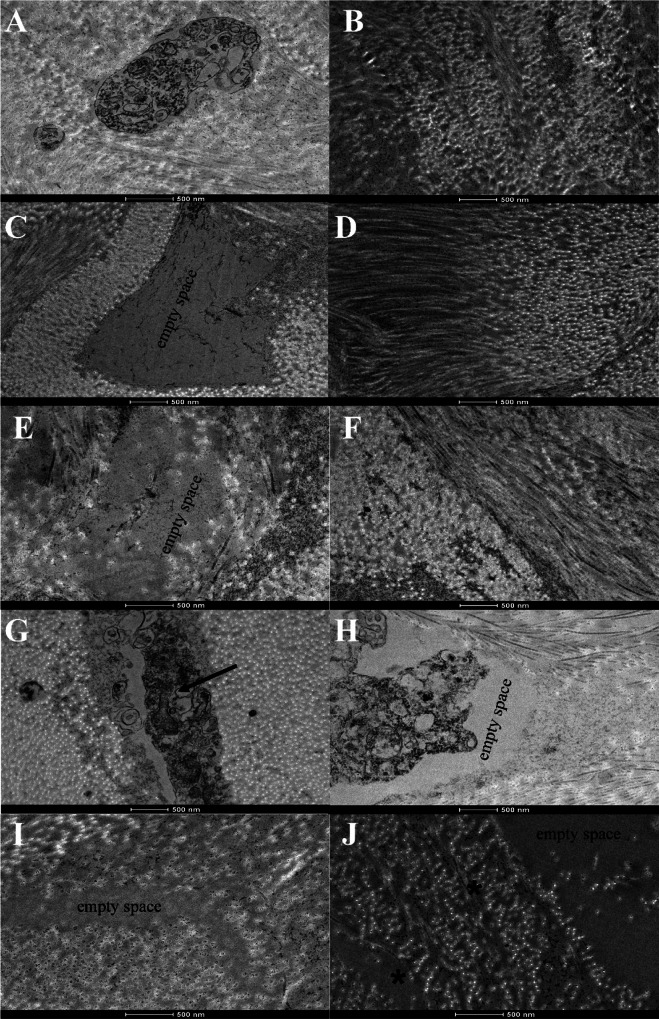

Ultrastructural architecture in stroma after decellularization processes

TEM analysis also indicated that in the native stroma some electron-dense structures, vacuoles, and cellular debris were observed (Fig. 3A). In the tissues treated with SDS 0.1% (Fig. 3C), SDS 1% (Fig. 3E), and Triton-X 1% (Fig. 3I) empty spaces where previous cells should be observed were found, while in stroma treated with NaCl some keratocytes residues were visualized between the lamella of collagen fibers (indicated by arrow in Fig. 3G), which corresponds to the previous demonstrated histological analyses.

Fig. 3.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) micrographs of decellularized corneal stroma. TEM images of the stroma of native cornea (A, B). Corneas treated with NaCl (G, H) show the presence of cellular components (indicated by black arrow), while in the images of SDS 0.1%, SDS 1%, and Triton-X 1% (C–F, I, J, respectively), no cellular debris were observed. The collagen fibrils showed a lower density in Triton-X 1% (indicated by asterisks in (J)). Scale bar: 500 nm

Moreover, the ultrastructural arrangement of collagen fibril architecture, in the native group, was normal and well organized (Fig. 3B). In the treated groups, the collagen fibers remained regular for SDS 0.1% (Fig. 3D), SDS 1% (Fig. 3F) and NaCl (Fig. 3H). However, in the Triton-X group (Fig. 3J), higher spacing (indicated by an asterisk) between the collagen fibers was observed. This observation is consistent with collagen quantification by histological data.

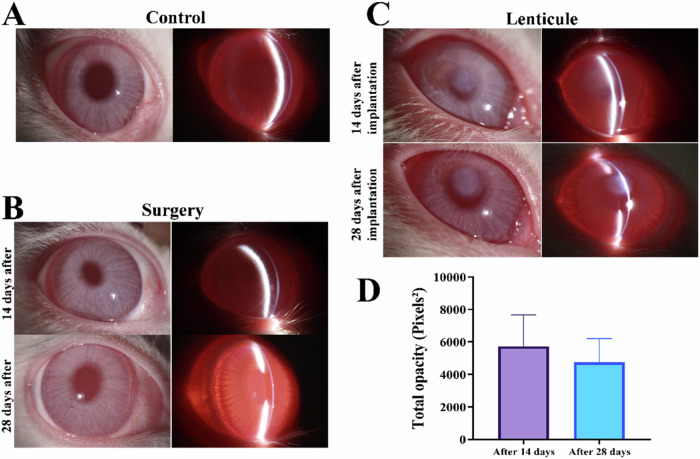

Slit lamp microscopy

In general, the interlamellar keratoplasty surgery realized was uneventful, except for one rabbit of the surgery group, which had its cornea perforated. Besides that, no interventions were registered during the period of the experiment.

Neovascularization and the incision place were first monitored daily, and then weekly. Eye irritation was observed for all operated animals in the first days after surgery. Also, a discharge could be observed in the corners of the eyes. These symptoms ceased to be significant after 3 days and all of the corneal surfaces were clear and smooth. The perforated cornea showed neovascularization that began on the 7th day. Thus, this animal was excluded in further analysis.

Representative images of the corneal surface along the time are shown in Fig. 4A. The decellularized corneal lenticule showed prominent haze, without interfering in the visibility of fine iris details, then was classified as grade 1. However, on the 14th day, it was observed that the haze was in the inner part of implanted lenticule. Also, the interface between native corneal stroma gradually became difficult to distinguish from the decellularized porcine lenticule and it could be seen with careful oblique illumination using slit lamp biomicroscopy. Thus, these corneas were reclassified as grade 0.5 until the end of the experiment.

Fig. 4.

Slit lamp and opacity quantification after surgery procedure. Representative slit-lamp photographs of (A) native cornea (control group), (B) corneas that underwent interlamellar keratoplasty procedure without (surgery group), and (C) with insertion of decellularized porcine corneal lenticule (lenticule group) after 14 and 28 days of procedure. D Quantification of central cornea haze after 14 and 28 days of interlamellar keratoplasty. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5)

In the opacity quantification, no statistical differences were observed between the 14 and 28 days of experiment. However, a reduction of 17.48 ± 18.19% in the opacity was observed, with corroborates with the clinical evaluation.

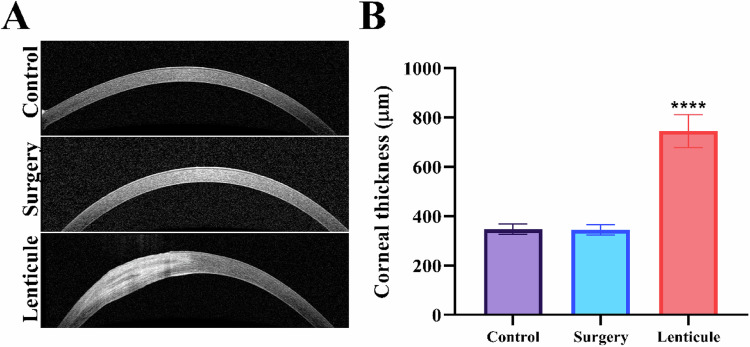

OCT images showed the presence of the lenticule in the cornea (Fig. 5A). It can be visualized that the lenticule was well-adhered to the host tissue in its entire circumference. The quantification of the cornea thickness showed a statistically significant increase in the place of the insertion of decellularized lenticule when compared to the native corneas in the control group (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

OCT images and Thickness of the cornea. A OCT images of native and postoperative cornea show the absence of changes in the cornea after the surgical process and the stroma in the corneas that received the decellularized porcine lenticule after 28 days. B Quantification of corneal thickness for all groups. Statistical significance was obtained by comparing control to surgery or lenticule groups. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5). ****p < 0.005

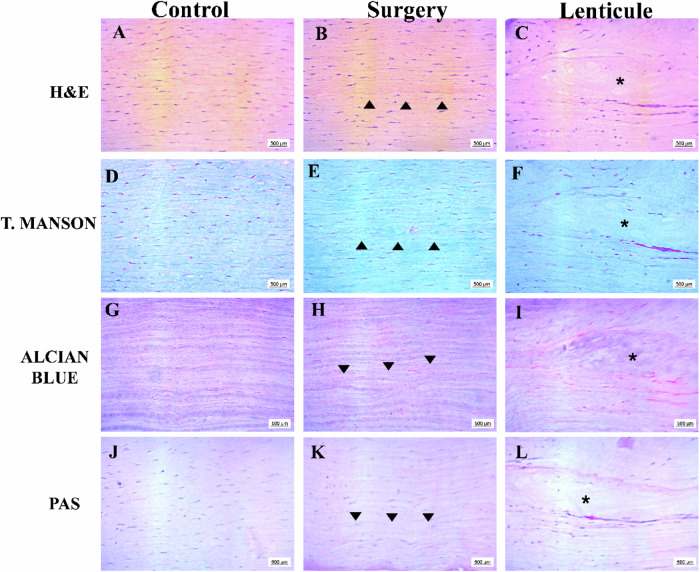

In general, the histology of the corneal stroma of control and surgery groups showed normal appearance with the presence of keratocytes and collagen fibers aligned in all staining, except for the presence of a positive collagen line (indicated by black arrowhead) which corresponds to the surgical cut in the interlamellar keratoplasty. In the lenticule group, it could be observed that the donor tissue (indicated by the asterisks) did not have keratocytes and the collagen fibers were thinner with orientation changes. Interestingly, in the same way as the previous results, it was difficult to distinguish the surface of the decellularized lenticule from the rabbit stroma in all staining. Also, it was observed the presence of some keratocytes and a major density of collagen fibers in the external portion of the implanted lenticules (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Representative histological sections of cornea native and 28 days after interlamellar keratoplasty. Sections were stained with H&E (A–C), T. Manson (D–F), Alcian Blue (G–I), and PAS (J–L). Scale bar: 500 μm (A–L). The black arrowheads show the surgical place on the corneal stroma in the surgery group (B, E, H, K) and the asterisks highlight the decellularized porcine lenticule (C, F, I, L)

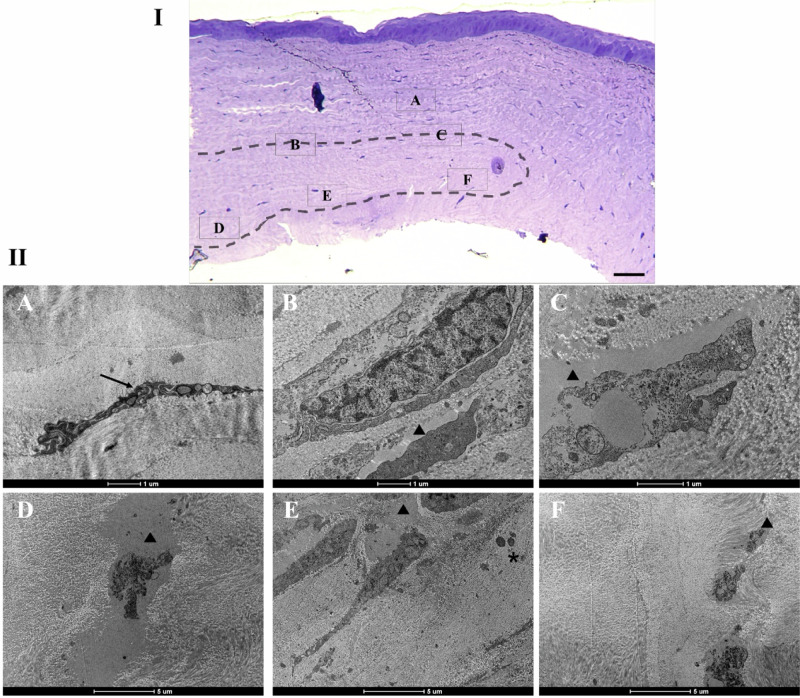

TEM analysis reveals that the rabbit cornea presents keratocytes and collagen fibrils with regular orientation and the decellularized lenticule was well-adhered to the host tissue (Fig. 7I). In the periphery of the lenticule it could be observed the presence of some keratocytes between the collagen fibrils (Fig. 7II—A). Cellular structures were found in spaces that used to be empty after the decellularization process, at upper (Fig. 7II—B, C) and under (Fig. 7II—D, E, F) boundaries of donor tissue (indicated by arrowhead). Moreover, granulocytes were identified in the implanted lenticule and are indicated by asterisks (Fig. 7II—E). Lastly, it could be observed that the collagen fibrils organization is more similar to the host corneal stroma in the lenticule periphery.

Fig. 7.

Ultrastructure of the corneal stroma at 28 days after interlamellar keratoplasty. I—Optical micrograph of the cornea stained with toluidine blue to demonstrate in the MET the areas around the lenticule. The dotted area indicates the insertion site of the decellularized lenticule. II—TEM images of the indicated areas in I are shown in (A–F). A Black arrow indicates keratocyte between the collagen fibrils. Empty cell space (arrowhead) shows cellular structures upper (B, C) and under (D–F) the boundaries of lenticule. D In the decellularized lenticule a fibril disorganization was observed. E Granulocytes (asterisks) were observed in transplanted lenticule. F The structure of the collagen fibrils was more organized in lenticule periphery

Discussion

The corneal stroma is a transparent layer essential in the refractive system of the eye. Although numerous researches have been conducted to find possible artificial substitutes, decellularized corneas from animals remain the best alternative [25–27]. In particular, porcine corneas are commonly due to easy access and human-like behavior [28].

In this view, many methods for corneal decellularization have been developed. However, nowadays there is no consensus regarding the viability of the decellularized tissues because the researchers have different results using similar methods [29, 30].

From our investigations, we observed that the transparency and hydration (%) were very similar in all decellularizing chemical agents used and there were no substantial differences compared to native stroma. However, in the histological analysis, it is interesting to highlight that the NaCl decellularization process did not eliminate all cellular compounds, and many keratocytes could be observed as demonstrated in Fig. 2. A similar result was found in a study carried out by [31] in which NaCl-treated corneas had more nuclear material than corneas treated with Triton-X or SDS. However, this study used the association with nucleases for better results.

Porcine corneal stroma was decellularized using NaCl in a study performed by [32] but, in this case, the epithelium and endothelium were removed by enzymatic digestion, which may have contributed to remove the keratocytes. Moreover, the authors observed that collagen fibrils were slightly loosened after decellularization, which has not been observed in our study. An evidence of this was the absence of significant differences in collagen quantification in comparison to native stroma. Nevertheless, irregular collagen fibril spacing was observed in Triton-X-treated stromas by Masson staining and TEM analyses as described before.

The main difference between decellularization solutions lies in the mechanism to remove cell components. NaCl is an ionic reagent that induces osmotic shock and subsequently, cell death, while SDS and Triton-X are detergents with different ionic groups [31, 33]. SDS has an ionic group that acts on protein-protein ligation and promotes cell and nuclear membrane solubilization. Thus, this class of detergent is capable of removing cellular components but they also change the extracellular matrix because of the breakage of protein ligations. Triton-X has a non-ionic group that interferes with lipid-lipid and lipid-protein interactions, thereby, the extracellular matrix is not affected [34, 35].

In this study, it was demonstrated that corneal stromas were optimally decellularized by 0.1% and 1% SDS. After the decellularization processes, samples from these groups showed transparent stroma with fibril-collagen architecture preserved and no cellular components, which corroborates with previously published results [34, 36]. However, some studies have demonstrated that 0.1% SDS can completely decellularize cornea with minimum structural disruption while others reported that in lower concentrations (up to 0.1% SDS), cellular debris was found in the decellularized tissue and high levels of fibril disorganization [31, 34, 37, 38].

Therefore, the in vivo biocompatibility test was performed using a 1% SDS lenticule decellularized. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study about the transplantation of porcine stromal lenticules decellularized by SDS 1% on rabbit cornea using the interlamellar keratoplasty.

Our findings provide evidence that lenticule intrastromal implantation was successfully performed in most cases and did not elicit a long-term immune response. The decellularized porcine lenticule remained relatively clear and well-adhered to the cornea host. Also, they promoted increase in the thickness of the corneal stroma, particularly in the mid-stromal layer (within the surgical area). These findings are similar to those that used similar surgical approaches for xenogenic grafting [14, 36, 39, 40].

Hence, it is important to emphasize that collagen fibrils present in the lenticule showed a more diffuse architecture and radial arrangement. This finding was also observed in the study conducted by [36], which is suggested that these changes could be attributed to the host keratocytes that stimulate stromal response through enzymes like metalloproteinases and collagenases to remodel the collagen fibrils.

In this paper, this hypothesis may be confirmed due to the presence of many keratocytes surrounding the implanted lenticule, which could be observed in the histological and TEM analyses.

Nevertheless, the implanted lenticules were swollen and slightly opaque after 28 days. This change occurs due to the increase of the collagen fibril space, partial changes in the extracellular matrix, and loss of cells, as previously described in the literature [36, 41–43]. These spaces are replaced by a fluid that changes the cornea refractive index. However, post-mortem lenticule transparency was quickly restored by immersion in 100% sterile glycerol (data not shown), which suggested that SDS 1% decellularization process preserved extracellular matrix stromal structure and chemical composition [14, 42].

However, there were also some limitations of our study. First, the short time follow-up hamper complete traceability of lenticule transparency. Second, the interlamellar lenticule implantation only reflects corneal stromal inflammation, excluding the endothelial reactions. Thus, in the next steps, improvement in lenticule and tissue host interactions were considered to be evaluated for better understanding the clinical scenario.

Conclusion

This study reported that SDS 1% efficiently decellularized porcine corneal stroma and generated acellular lenticules that met the basic features to act as alternative tissue in the treatment of corneal diseases. The decellularized lenticule implantation promoted an increase in corneal stroma host thickness with negligible immunogenicity and recellularization potential. Actually, there is no well-defined protocol to use xenogeneic tissue for corneal repair. The decellularization protocol combined with interlamellar keratoplasty may be beneficial to many corneal diseases. Further studies should explore the long-term evaluation of this technique to ensure the future applicability in humans.

Acknowledgements

To Brazilian National Counsel of Technological and Scientific Development and the Minas Gerais Research Foundation, Brazil.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lorenzo-Martín E, Gallego-Muñoz P, Mar S, Fernández I, Cidad P, Martínez-García MC. Dynamic changes of the extracellular matrix during corneal wound healing. Exp Eye Res 2019;186:107704. 10.1016/j.exer.2019.107704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma J, Wang Y, Wei P, Jhanji V. Biomechanics and structure of the cornea: implications and association with corneal disorders. Surv Ophthalmol 2018;63:851–61. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2018.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahearne M. Corneal extracellular matrix decellularization. 2020:81–95. 10.1016/bs.mcb.2019.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Ehlers N, Hjortdal J. Corneal thickness: measurement and implications. Exp Eye Res 2004;78:543–8. 10.1016/j.exer.2003.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michelacci YM. Collagens and proteoglycans of the corneal extracellular matrix. Braz J Med Biol Res 2003;36:1037–46. 10.1590/S0100-879X2003000800009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu AC, Mattioli L, Busin M. Optimizing outcomes for keratoplasty in ectatic corneal disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2020;31:268–75. 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dua HS, Darren SJ, Mouhamed Al-Aqaba T, Said DG. Pathophysiology of Keratoconus, In: Keratoconus. Elsevier; 2023. p. 51–64. 10.1016/B978-0-323-75978-6.00005-4

- 8.Godefrooij DA, Gans R, Imhof SM, Wisse RPL. Nationwide reduction in the number of corneal transplantations for keratoconus following the implementation of cross‐linking. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016;94:675–8. 10.1111/aos.13095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santodomingo-Rubido J, Carracedo G, Suzaki A, Villa-Collar C, Vincent SJ, Wolffsohn JS. Keratoconus: An updated review. Contact Lens Anterior Eye. 2022;45:101559. 10.1016/j.clae.2021.101559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez A, Price MO, Feng MT, Lee C, Arbelaez JG, Price FW. Immunologic rejection episodes after deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty: incidence and risk factors. Cornea. 2017;36:1076–82. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gadhvi KA, Coco G, Pagano L, Kaye SB, Ferrari S, Levis HJ, et al. Eye banking: one cornea for multiple recipients. Cornea. 2020;39:1599–603. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amano S, Shimomura N, Kaji Y, Ishii K, Yamagami S, Araie M. Antigenicity of porcine cornea as xenograft. Curr Eye Res 2003;26:313–8. 10.1076/ceyr.26.5.313.15440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Formisano N, van der Putten C, Grant R, Sahin G, Truckenmüller RK, Bouten CVC, et al. Mechanical properties of bioengineered corneal stroma. Adv Healthc Mater 2021;10:2100972. 10.1002/adhm.202100972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pang K, Du L, Wu X. A rabbit anterior cornea replacement derived from acellular porcine cornea matrix, epithelial cells and keratocytes. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7257–65. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson S, Sidney L, Dunphy S, Rose J, Hopkinson A. Keeping an eye on decellularized corneas: a review of methods, characterization and applications. J Funct Biomater 2013;4:114–61. 10.3390/jfb4030114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang F, Zhao L, Li H, Li D, Zhou M, Zhou Q, et al. Scleral defect repair using decellularized porcine sclera in a rabbit model. Xenotransplantation. 2020;27. 10.1111/xen.12633 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Hashimoto Y, Funamoto S, Sasaki S, Negishi J, Hattori S, Honda T, et al. Re-epithelialization and remodeling of decellularized corneal matrix in a rabbit corneal epithelial wound model. Mater Sci Eng C. 2019;102:238–46. 10.1016/j.msec.2019.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hashimoto Y, Hattori S, Sasaki S, Honda T, Kimura T, Funamoto S, et al. Ultrastructural analysis of the decellularized cornea after interlamellar keratoplasty and microkeratome-assisted anterior lamellar keratoplasty in a rabbit model. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27734. 10.1038/srep27734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu X, Wei R, Liu C, Wang Y, Yang D, Sun L, et al. Recent advances in small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE)-derived refractive lenticule preservation and clinical reuse. Eng Regen 2023;4:103–21. 10.1016/j.engreg.2023.01.002 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu N, Chen S, Yang X, Hou X, Wan L, Huang Y, et al. Comparison of fresh and preserved decellularized human corneal lenticules in femtosecond laser-assisted intrastromal lamellar keratoplasty. Acta Biomater. 2022;150:154–67. 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baratta RO, Del Buono BJ, Schlumpf E, Ceresa BP, Calkins DJ. Collagen mimetic peptides promote corneal epithelial cell regeneration. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12. 10.3389/fphar.2021.705623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Kim A, Martinez-Valbuena I, Li J, Lang AE, Kovacs GG. Disease-specific α-synuclein seeding in lewy body disease and multiple system atrophy are preserved in formaldehyde-fixed paraffin-embedded human brain. Biomolecules. 2023;13:936. 10.3390/biom13060936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fantes FE. Wound healing after excimer laser keratomileusis (photorefractive keratectomy) in monkeys. Arch Ophthalmol 1990;108:665. 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070070051034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim S, Park YW, Lee E, Park SW, Park S, Kim JW, et al. Air assisted lamellar keratectomy for the corneal haze model. J Vet Sci 2015;16:349. 10.4142/jvs.2015.16.3.349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang H, Han Y, Jin M, Zheng L, Liu Zhen, Xue Y, et al. Decellularized squid mantle scaffolds as tissue‐engineered corneal stroma for promoting corneal regeneration. Bioeng Transl Med. 2023;8. 10.1002/btm2.10531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Taylor DA, Sampaio LC, Ferdous Z, Gobin AS, Taite LJ. Decellularized matrices in regenerative medicine. Acta Biomater. 2018;74:74–89. 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.04.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X, Chen X, Hong H, Hu R, Liu J, Liu C. Decellularized extracellular matrix scaffolds: Recent trends and emerging strategies in tissue engineering. Bioact Mater 2022;10:15–31. 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoon CH, Choi HJ, Kim MK. Corneal xenotransplantation: where are we standing? Prog Retin Eye Res. 2021;80:100876. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2020.100876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernández-Pérez J, Ahearne M. Decellularization and recellularization of cornea: progress towards a donor alternative. Methods. 2020;171:86–96. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2019.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holland G, Pandit A, Sánchez-Abella L, Haiek A, Loinaz I, Dupin D, et al. Artificial cornea: past, current, and future directions. Front Med. 2021;8. 10.3389/fmed.2021.770780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Wilson SL, Sidney LE, Dunphy SE, Dua HS, Hopkinson A. Corneal decellularization: a method of recycling unsuitable donor tissue for clinical translation? Curr Eye Res. 2016;41:769–82. 10.3109/02713683.2015.1062114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma XY, Zhang Y, Zhu D, Lu Y, Zhou G, Liu W, et al. Corneal stroma regeneration with acellular corneal stroma sheets and keratocytes in a rabbit model. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132705. 10.1371/journal.pone.0132705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilbert T, Sellaro T, Badylak S. Decellularization of tissues and organs. Biomaterials. 2006. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marin-Tapia HA, Romero-Salazar L, Arteaga-Arcos JC, Rosales-Ibáñez R, Mayorga-Rojas M. Micro-mechanical properties of corneal scaffolds from two different bio-models obtained by an efficient chemical decellularization. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2021;119:104510. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2021.104510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Du L, Wu X, Pang K, Yang Y. Histological evaluation and biomechanical characterisation of an acellular porcine cornea scaffold. Br J Ophthalmol 2011;95:410–4. 10.1136/bjo.2008.142539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yam GH-F, Yusoff NZBM, Goh T-W, Setiawan M, Lee X-W, Liu Y-C, et al. Decellularization of human stromal refractive lenticules for corneal tissue engineering. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26339. 10.1038/srep26339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez-Andrades M, de la Cruz Cardona J, Ionescu AM, Campos A, del Mar Perez M, Alaminos M. Generation of bioengineered corneas with decellularized xenografts and human keratocytes. Investig Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:215. 10.1167/iovs.09-4773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nara S, Chameettachal S, Midha S, Murab S, Ghosh S. Preservation of biomacromolecular composition and ultrastructure of a decellularized cornea using a perfusion bioreactor. RSC Adv. 2016;6:2225–40. 10.1039/C5RA20745B [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alio del Barrio JL, Chiesa M, Garagorri N, Garcia-Urquia N, Fernandez-Delgado J, Bataille L, et al. Acellular human corneal matrix sheets seeded with human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells integrate functionally in an experimental animal model. Exp Eye Res. 2015;132:91–100. 10.1016/j.exer.2015.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi JS, Williams JK, Greven M, Walter KA, Laber PW, Khang G, et al. Bioengineering endothelialized neo-corneas using donor-derived corneal endothelial cells and decellularized corneal stroma. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6738–45. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamil S, Mohan RR. Corneal stromal wound healing: major regulators and therapeutic targets. Ocul Surf 2021;19:290–306. 10.1016/j.jtos.2020.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pantic IV, Cumic J, Valjarevic S, Shakeel A, Wang X, Vurivi H, et al. Computational approaches for evaluating morphological changes in the corneal stroma associated with decellularization. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11. 10.3389/fbioe.2023.1105377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Espana EM, Birk DE. Composition, structure and function of the corneal stroma. Exp Eye Res. 2020;198:108137. 10.1016/j.exer.2020.108137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]