Abstract

Aberrant transcriptional regulation of transforming growth factor α (TGFα) appears to be an important contributor to the malignant phenotype and the growth factor independence with which malignancy is frequently associated. However, little is known about the molecular mechanisms responsible for dysregulation of TGFα expression in the malignant phenotype. In this paper, we report on TGFα promoter regulation in the highly malignant growth factor-independent cell line HCT116. The HCT116 cell line expresses TGFα and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) but is not growth inhibited by antibodies to EGFR or TGFα. However, constitutive expression of TGFα antisense RNA in the HCT116 cell line resulted in the isolation of clones with markedly reduced TGFα mRNA and which were dependent on exogenous growth factors for proliferation. We hypothesized that if TGFα autocrine activation is the major stimulator of TGFα expression in this cell line, TGFα promoter activity should be reduced in the antisense TGFα clones in the absence of exogenous growth factor. This was the case. Moreover, transcriptional activation of the TGFα promoter was restored in an antisense-TGFα-mRNA-expressing clone which had reverted to a growth factor-independent phenotype. Using this model system, we were able to identify a 25-bp element within the TGFα promoter which conferred TGFα autoregulation to the TGFα promoter in the HCT116 cell line. In the TGFα-antisense-RNA-expressing clones, this element was activated by exogenous EGF. This 25-bp sequence contained no consensus sequences of known transcription factors so that the TGFα or EGF regulatory element within this 25-bp sequence represents a unique element. Further characterization of this 25-bp DNA sequence by deletion analysis revealed that regulation of TGFα promoter activity by this sequence is complex, as both repressors and activators bind in this region, but the overall expression of the activators is pivotal in determining the level of response to EGF or TGFα stimulation. The specific nuclear proteins binding to this region are also regulated in an autocrine-TGFα-dependent fashion and by exogenous EGF in EGF-deprived TGFα antisense clone 33. This regulation is identical to that seen in the growth factor-dependent cell line FET, which requires exogenous EGF for optimal growth. Moreover, the time response of the stimulation of trans-acting factor binding by EGF suggests that the effect is directly due to growth factor and not mediated by changes in growth state. We conclude that this element appears to represent the major positive regulator of TGFα expression in the growth factor-independent HCT116 cell line and may represent the major site of transcriptional dysregulation of TGFα promoter activity in the growth factor-independent phenotype.

The autocrine growth factor hypothesis was proposed to explain the decreased exogenous growth factor dependence that is associated with the loss of growth regulation of the transformed phenotype (41–43). Autocrine growth regulation is characterized by coexpression of both the growth factor and its receptor, leading to a positive feedback growth stimulus. The mouse homolog of transforming growth factor α (TGFα) was the first positive growth factor which behaved in this manner to be described (11). TGFα is a member of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) family (6, 12, 45). All members are highly homologous to EGF and exert their biological effects through the EGF receptor (EGFR).

Interestingly, EGFR activation by TGFα or EGF stimulates TGFα mRNA synthesis and, consequently, increases TGFα protein production (2, 8, 9). The addition of EGF or TGFα to cultured cells, including keratinocytes and breast and colon carcinoma cells, results in a dose-dependent increase in TGFα mRNA production at 4 to 8 h. The secretion of TGFα protein into the culture medium also increases with similar kinetics. Furthermore, expression of TGFα in the weakly tumorigenic colon carcinoma cell line GEO by stable transfection of a TGFα expression vector results in the isolation of clones which show increased tumorigenicity both in vitro and in vivo (47). Significantly, endogenous TGFα mRNA was induced in these cells, which normally express very little TGFα, as a result of transfection of the TGFα expression vector.

The stimulation of TGFα mRNA production by TGFα autocrine activity may significantly enhance the growth stimulatory effect in the various cancers in which it is expressed. However, very little is known about the molecular mechanisms for transcriptional autoregulation of TGFα expression. In order to study the transcriptional control of TGFα autocrine activity, we cloned a 2,813-bp fragment of the TGFα promoter (translation start site designated 1) (25, 34), thus extending TGFα promoter characterization by 1,673 bp in the 5′ direction beyond that reported by another group (24). The regions of the 5′ flanking DNA sequences which overlap are identical. The rat TGFα promoter has also been cloned and shows significant homology with the human gene (3). Notable features of the TGFα promoter are that it does not contain CCAAT or TATA box sequences but that there are several Sp-1 sites located in the first 600 bp of DNA. Since classical autocrine TGFα activation of the EGFR stimulates further TGFα production, the characterization of the TGFα response element within the human TGFα promoter is important to the understanding of the regulation of this gene.

The human HCT116 colon carcinoma cell line expresses both TGFα and EGFR (33, 34, 47). These cells show complete independence from the need of exogenous growth factors, including EGF and TGFα (33, 34, 47). It seemed likely that the presence of an inappropriately regulated TGFα autocrine loop in this cell line would account for this growth factor independence. However, neutralizing antibodies to either TGFα or EGFR did not inhibit the growth of these cells. Burgess used TGFα antisense oligonucleotides to effectively disrupt TGFα autocrine activity in several colon carcinoma cell lines (39, 40). Consequently, we used constitutive TGFα antisense RNA expression in HCT116 cells to show the functional importance of the TGFα autocrine loop in the HCT116 cell line (21). Constitutive expression of TGFα antisense RNA by stable transfection of an expression vector resulted in the isolation of clones which had decreased TGFα mRNAs and consequently were dependent on exogenous growth factors, including EGF and TGFα, for growth.

It seemed likely that the antibody-inaccessible TGFα autocrine loop might stimulate TGFα promoter activity by autoinduction in HCT116 cells. Therefore, we examined TGFα transcriptional regulation in the HCT116 cell line. The development of antisense clones of HCT116 with disrupted TGFα autocrine function facilitated these studies. TGFα promoter transcriptional activity was studied in a NEO transfected parental line and in TGFα-antisense-RNA-expressing clones designated clone U and clone 33. By comparing the activities of various deletion constructs in the parental cell line with that in clone U or clone 33 in the absence of exogenous EGF, we were able to define the TGFα autostimulatory element regulating TGFα expression in HCT116 cells. This appears to represent a unique element, showing no homology to consensus sequences of known transcription factors. Moreover, regulation of TGFα promoter activity by this site involves both repressors and activators of transcription. We show that autocrine TGFα activation of the TGFα promoter is a major positive regulator of TGFα expression in this growth factor-independent cell line.

(This report was completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Ph.D. by Rana Awwad.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

The HCT116 cell line was derived from a primary human tumor and was routinely maintained in a serum-free medium as previously described (4, 33, 46). This consists of McCoy’s 5A medium (Sigma) supplemented with amino acids, pyruvate, antibiotics, and the growth factors insulin (20 μg/ml; Sigma), transferrin (4 μg/ml; Sigma), and EGF (10 ng/ml; Collaborative Research). Working cultures were maintained at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. Cells were subcultured with 0.05% trypsin in Joklik’s medium (Gibco) containing 0.1% EDTA and replated in serum-free medium.

RNA preparation and analysis.

Total RNA was prepared from cultured cells which had been switched to serum-free medium at 50 to 60% confluency for 48 h prior to harvest. In experiments where the effect of exogenous EGF on TGFα expression was studied, some cells were treated with EGF for 4 h prior to harvest. The RNA was prepared essentially as described by Chirgwin et al. (7) with a cesium trifluoroacetate gradient (Pharmacia). For Northern blot analysis, total RNA (30 μg) was electrophoresed in a 1.2% agarose–formaldehyde gel by using a phosphate buffer system as described by Maniatis et al. (29). Following staining with ethidium bromide to verify equal loadings, the RNA was transferred to a Nytran nylon membrane (Schleicher and Schuell) and hybridized with a high-specific-activity full-length 930-bp TGFα cDNA probe. Probe was labelled with [32P]dCTP with a Multiprime labelling kit (Amersham). The RNase protection assay for TGFα mRNA was performed as has been described previously (21).

Cloning of the TGFα promoter.

A normal human leukocyte genomic library in EMBL3 vector (Clontech) was screened with a probe homologous to the published TGFα cDNA sequence spanning +104 to +129 (27, 37). This screening resulted in the isolation of a 2,813-bp fragment comprising 125 bp of untranslated sequence and 2,695 bp of 5′ flanking sequence. Deletion fragments were generated by use of appropriate restriction enzymes and the PCR technique and were cloned just upstream of the bacterial chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene in the pGCAT-C vector. In order to generate deletion mutants of the 25-bp TGFα autoregulatory element within the context of the TGFα promoter, primers were designed for use with the Stratagene Ex-Site PCR-directed mutagenesis protocol to delete specific motifs within the 25-bp element.

Heterologous promoter constructs contained either the thymidine kinase (TK) promoter in the pBLCAT2 vector or the first 65 bp of the adenovirus major late promoter (AML65; includes 10 bp of untranslated coding sequence), which replaced the TK promoter in the pBLCAT2 vector. There are no restriction sites present within the EGF response element of the TGFα promoter which would facilitate further subcloning. Therefore, oligonucleotides containing the sequences of interest were synthesized with BamHI sticky ends and cloned just upstream of the appropriate heterologous promoter.

Transient transfections and CAT assays.

HCT116 cells and clones were harvested by trypsinization, resuspended in 800 μl of serum-free medium, and transferred to a 0.4-cm-diameter electrogap cuvette containing 50 μg of the appropriate TGFα promoter-CAT construct. Cells (approximately 2 × 108 per cuvette) were electroporated in a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser (250 V, 960 μF). A Rous sarcoma virus–β-galactosidase reporter construct (15 μg) was cotransfected to account for transfection efficiency. Cells were divided between two dishes containing serum-free medium and changed 12 h later to serum-free medium minus EGF. Cells were harvested at 36 to 48 h following removal of EGF from the medium.

Cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline and harvested by scraping them in 1 ml of TEN buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl). Following centrifugation, cells were resuspended in 250 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, and lysed by three cycles of freezing-thawing. Protein concentration was determined by macroassay with bicinchoninic acid reagent (Pierce). The β-galactosidase activity was quantitated by the microassay as described by Promega.

Cell lysates were added to the CAT assay corrected for β-galactosidase activity. The CAT activity of each sample was determined in a total volume of 164 μl in 250 mM Tris, pH 7.8, containing 0.2 μCi of [14C]chloramphenicol [14C-d-threo (dichloroacetyl-1-14C) chloramphenicol, 55 mCi/mmol; Amersham] and 3.6 mM acetyl coenzyme A (lithium salt; Pharmacia) overnight at 37°C. Both the acetylated and the remaining nonacetylated [14C]chloramphenicol were extracted with ethyl acetate and separated by thin-layer chromatography by using a chloroform-methanol solvent system.

The HCT116 TGFα antisense transfectants were previously described (21). Briefly, in order to disrupt TGFα autocrine function in HCT116 cells, TGFα antisense RNA was constitutively expressed in this cell line by stable transfection of an expression vector containing TGFα cDNA inserted in the antisense orientation relative to the cytomegalovirus promoter in the vector pRC/CMV (Invitrogen). This construct, which contains a neomycin (NEO) selection marker, was transfected into HCT116 cells by electroporation as described above, but cells were subsequently plated at 1:40 to 1:50 dilutions. Transfected clones were selected with geneticin (600 μg/ml) and expanded following ring cloning. Northern blot analysis of total RNA was performed to detect the presence of antisense TGFα RNA. Incorporation of the antisense TGFα cDNA into the genomes of the resistant clones was confirmed by Southern blot analysis. Typical antisense transfectant clones U and 33 (21) were chosen for these studies.

Nuclear extracts.

Cells were harvested either following removal of EGF from the medium for 36 to 48 h or following subsequent EGF treatment for 1 or 4 h. HCT116 cells were lysed with a type B pestle in homogenization buffer containing 0.5 mM dithiothreitol and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride as described by Dignam et al. (14). Following centrifugation, nuclear proteins were extracted from the partially purified nuclei by addition of 3 M KCl to a final concentration of 0.6 M and ammonium sulfate precipitated as described by Gorski et al. (18). Following dialysis against 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, containing 0.1 mM EDTA, 40 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, and 1 mM dithiothreitol, nuclear extracts were concentrated to 5 to 10 mg/ml with Aquacide I (Calbiochem), aliquoted, snap-frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80°C.

Gel shifts.

High-specific-activity double-stranded oligonucleotide labelled with [32P]ATP by T4 polynucleotide kinase was incubated with nuclear extract in a final volume of 20 μl (18). Following incubation on ice, the reaction mix was loaded onto a 4% polyacrylamide gel in 25 mM Tris–25 mM boric acid buffer containing 0.5 mM EDTA and run at 150 to 250 V at 4°C (38). Nuclear extracts were run against synthesized, double-stranded oligonucleotide comprising the 25-bp TGFα autoregulatory element (−225 to −201 of the TGFα promoter; designated oligonucleotide 3/4) and oligonucleotides comprising the element with various 4-bp deletions along its length. Non-TGFα-responsive oligonucleotide comprising −201 to −176 of the TGFα promoter (designated oligonucleotide 5/6) was run as a control. Competition studies with cold oligonucleotide were performed to confirm specificity of binding.

RESULTS

TGFα antisense RNA expression.

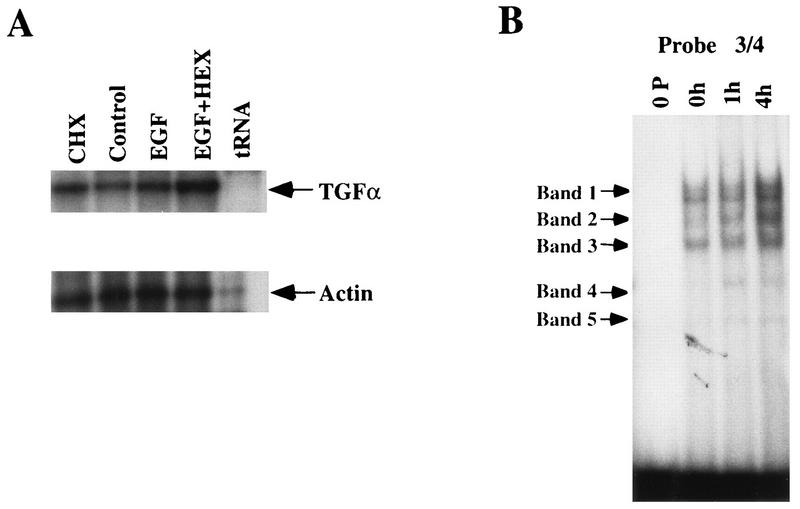

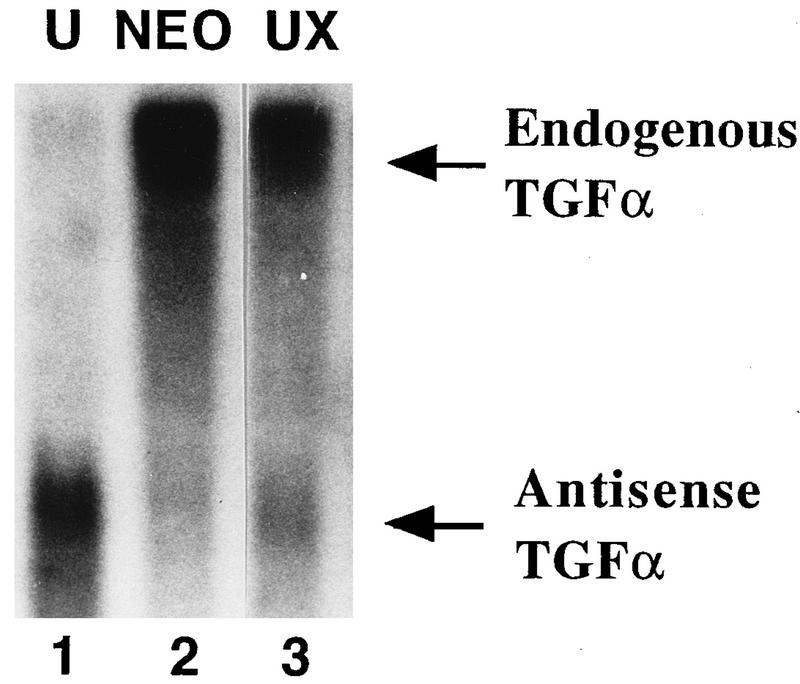

TGFα antisense RNA was constitutively expressed in HCT116 cells by stable transfection of a vector containing TGFα cDNA inserted in the antisense orientation to the cytomegalovirus promoter. To confirm constitutive expression of the TGFα antisense RNA, total RNA from the NEO-resistant and TGFα-antisense-RNA-expressing clones was subjected to Northern blot analysis with a cDNA probe labelled with [32P]dCTP by random priming. As both sense and antisense strands are labelled, sense and antisense RNAs can be studied on the same blot. Figure 1 shows the Northern blot analysis of RNA from one of the antisense clones, designated clone U. A 4.8-kb mRNA transcript corresponding to endogenous TGFα mRNA is present in both the NEO control cells (lane 2) and clone U (lane 1), but the 1.1-kb transcript corresponding to the antisense TGFα mRNA is present only in clone U (lane 1). Due to the expression of this TGFα antisense RNA, the level of TGFα mRNA in clone U is reduced to 10 to 20% of that in the NEO control cells. This decrease is consistent with a fivefold reduction in the amount of the TGFα protein secreted into the culture medium by clone U compared to that secreted by the NEO control cells, as assessed by an EGFR competitive binding assay (21). In accord with the decreased TGFα production, clone U requires the presence of exogenous EGF or TGFα in the culture medium for optimal growth (21).

FIG. 1.

Northern blot of TGFα RNA in clone U and revertant clone UX. Total RNAs from clone U (lane 1), UX (lane 3), and the NEO control (lane 2) were analyzed by Northern blotting for TGFα mRNA. The TGFα cDNA probe was labelled by random priming, and so endogenous (sense) TGFα mRNA and antisense TGFα RNA are both detected on the same blot.

Antisense-RNA-expressing cells which had reverted back to a high-TGFα-expression phenotype were also isolated (21). This clone, designated UX, did not require exogenous EGF or TGFα in the culture medium for optimal growth. Although UX still expressed antisense RNA, it had a level of TGFα mRNA similar to that of the NEO cell line (Fig. 1, lane 3). Similar data were obtained with other revertant TGFα-antisense-RNA-expressing clones (21).

Exogenous EGF increases TGFα expression in the TGFα-antisense-mRNA-expressing clones.

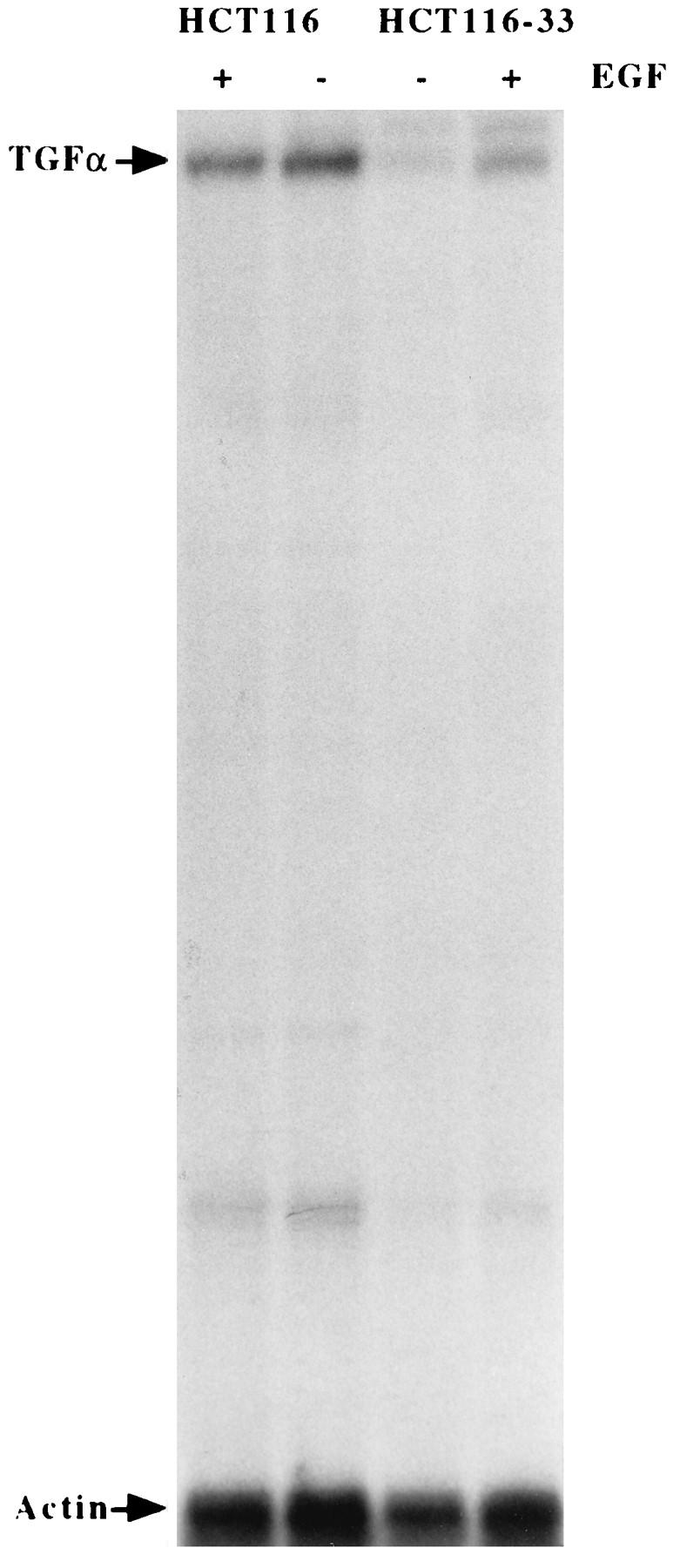

The effect of exogenous EGF (10 ng/ml) on TGFα mRNA expression in EGF-deprived parental HCT116 and clone 33 cells was studied. As shown in Fig. 2, the addition of EGF to the EGF-deprived parental cell line did not affect the TGFα mRNA level. However, in the TGFα-antisense-mRNA-transfected cells designated clone 33, which has a basal level of TGFα ∼20% of that of the parental cell line, the addition of EGF led to increased TGFα mRNA levels. Treatment with EGF for 4 h resulted in an approximately threefold increase in TGFα mRNA (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Effect of EGF treatment on TGFα expression in TGFα-antisense-RNA-transfected cells. HCT116 and TGFα-antisense-RNA-transfected cells (HCT116-33) were changed to serum-free medium minus EGF. After 48 h, cells were treated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for 4 h and RNA was isolated. Total RNA (40 μg) was analyzed by RNase protection assay for TGFα mRNA. An actin probe was used to normalize for loading.

Effect of disruption of the TGFα autocrine loop on TGFα promoter activity.

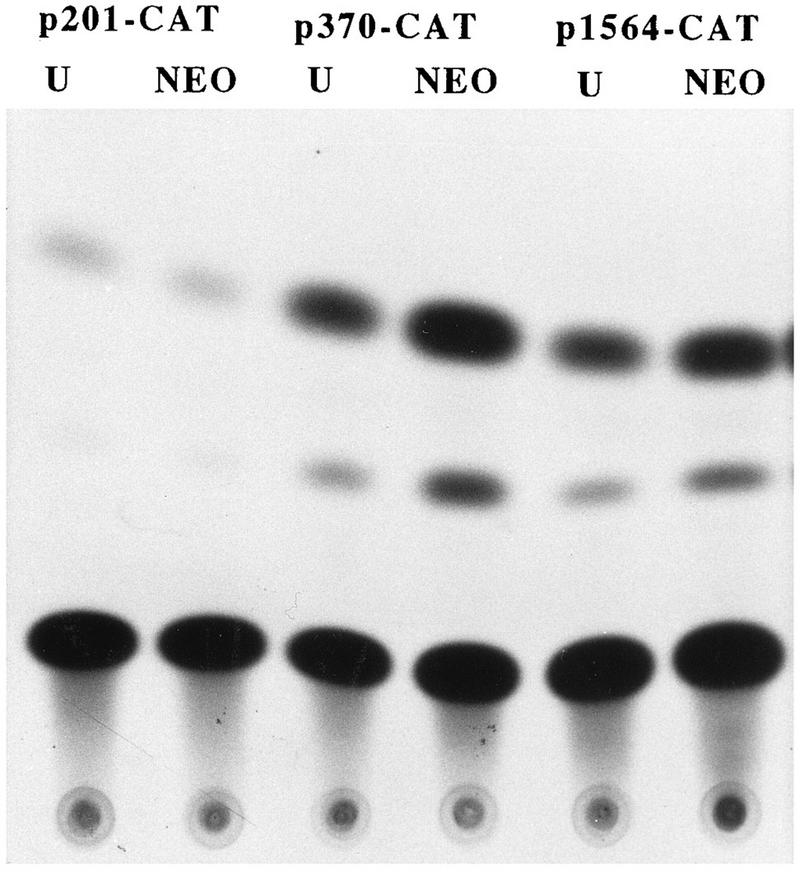

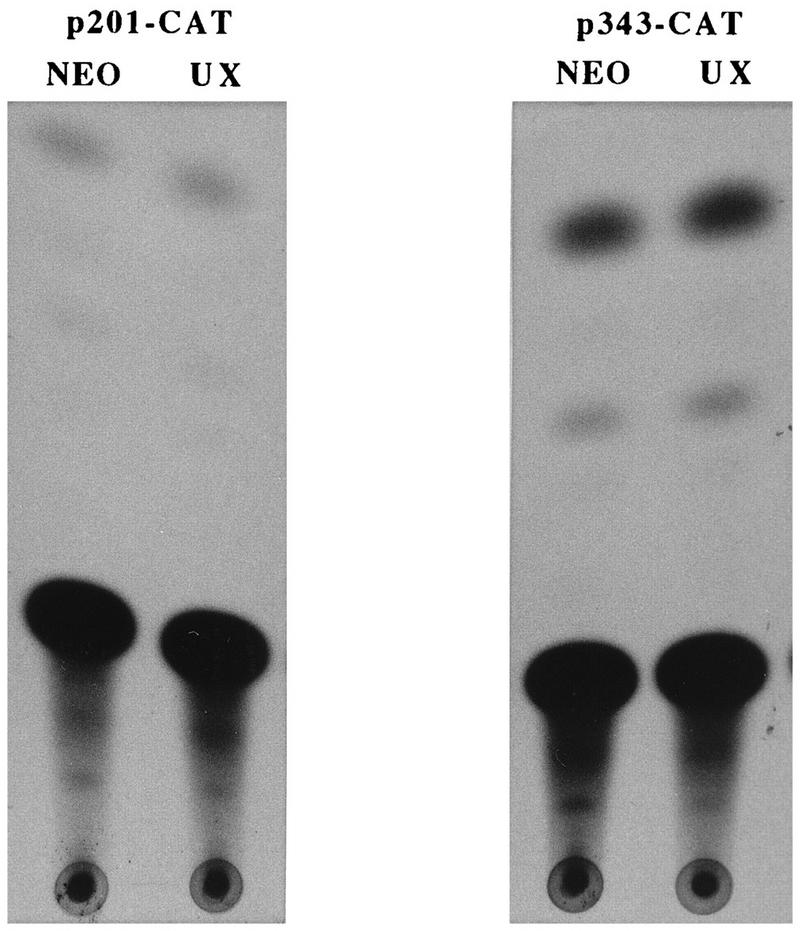

The antisense-RNA-expressing clone U and revertant clone UX provided a model to study the effects of endogenous TGFα modulation on TGFα promoter activity in the HCT116 cell line. In particular, repression of endogenous TGFα should result in reduced activity of TGFα promoter constructs containing a TGFα autoregulatory element, while activity of these constructs should be restored to that of the parental or NEO control cell line in the revertant clone UX. As exogenous EGF can partially restore TGFα mRNA expression in the TGFα antisense clones, it was necessary to remove EGF from the medium of the cells following transfection in order to abrogate any effects of exogenous EGF on stimulation of promoter activity. Figure 3 shows a typical result of a transient-transfection study with the p201-, p343-, and p1564-CAT constructs (containing 201, 343, and 1,564 nucleotides, respectively, of 5′ DNA flanking sequence adjacent to the ATG start codon, designated 1). The activities of the p1564- and p343-CAT constructs were reduced two- to threefold in clone U compared to that of the NEO control in the absence of exogenous EGF. However, the activities of the p201-CAT construct are similar in both clone U and the control. In contrast, the activity of the p343-CAT construct is slightly increased in the revertant clone UX compared to that of the control (Fig. 4). Again, the CAT activities of the p201-CAT construct are similar in the UX and the NEO control. As expected from the mRNA data shown in Fig. 2, if the cells are maintained in the presence of exogenous EGF, there is little difference in the levels of transcription of the p343-CAT constructs in the control cells and clone U (data not shown). In further transient-transfection comparisons of clone U and the NEO control, the p370-, p343-, and p247-CAT constructs each showed 2.5-, 2.1-, and 2.9-fold increased activities, respectively, in the NEO control cells compared to that of clone U in the absence of exogenous EGF or TGFα. In contrast, each of these constructs showed activity similar to that of the NEO control cell line in the revertant UX clone. These results suggest that the activities of the TGFα constructs p370, p343, and p247 reflect the endogenous TGFα levels within the various clones but that the activity of the p201-CAT construct does not. This suggestion infers that there is an element responsive to the autocrine TGFα level between −201 and −247 of the TGFα promoter. Therefore, regulation of the TGFα promoter by autocrine TGFα appears to significantly affect TGFα expression in the HCT116 cell line.

FIG. 3.

TGFα promoter activity in TGFα-antisense-RNA-expressing clone U. The p201-, p370-, and p1564-CAT constructs were transiently transfected into clone U and NEO-transfected control cells. At 12 h following transfection, cells were switched to serum-free medium minus EGF, and 48 h later, cells were harvested for CAT assay.

FIG. 4.

TGFα promoter activity in revertant-phenotype clone UX. The p201- and p343-CAT constructs were transiently transfected into clone UX, a TGFα-antisense-mRNA-expressing clone which had reverted to a growth factor-independent phenotype. These same vectors were also transfected into NEO control cells. At 12 h following transfection, cells were switched to serum-free medium minus EGF, and 48 h later, the cells were harvested for CAT assay.

Further localization of the TGFα autoregulatory element.

In order to confirm the identity and localization of the TGFα autoregulatory element, overlapping oligonucleotides with DNA sequences corresponding to positions −247 to −220 (designated oligonucleotide 1/2), −225 to −201 (designated oligonucleotide 3/4), and −201 to −176 (designated oligonucleotide 5/6) of the TGFα promoter were synthesized and inserted just upstream of the TK promoter in the pBLCAT2 vector. The CAT activities of these heterologous constructs in clones U and UX were compared with the activities of the constructs in the control cells.

The TK promoter is severalfold more active than the TGFα promoter, and the TGFα autoregulatory element caused only two- to threefold stimulation of gene expression. Thus, the activity of the TK promoter obscures TGFα autoregulatory effects in the presence of EGF. Therefore, in order to carry out this experiment, we adopted a strategy of looking in clone U for decreased TGFα promoter activity due to low endogenous TGFα in the absence of exogenous EGF on the one hand and increased CAT activity when EGF was added back to the medium on the other. This strategy allowed us to confirm the presence of the EGF/response or TGFα autoregulatory element within clone U and obviated our relying on comparisons between clones with high levels of expression of the TK promoter.

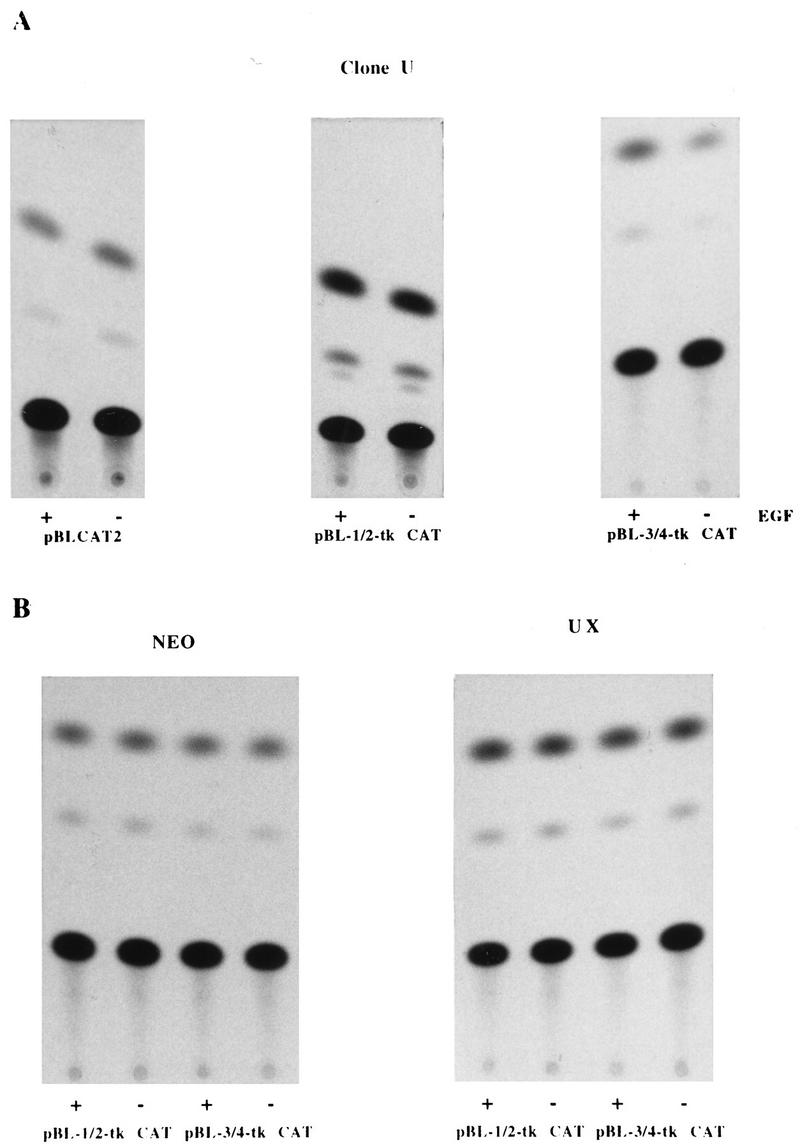

The results of these assays are shown in Fig. 5 and summarized in Table 1. In the NEO control clone and clone UX, the activities of all three heterologous constructs (pBL-1/2-CAT, pBL-3/4-CAT, and pBL-5/6-CAT) were similar in both the presence and absence of EGF. Moreover, when clone U was maintained in serum-free medium containing EGF, the CAT activities of the heterologous constructs were similar to those seen in the NEO control and clone UX. When EGF was removed from the medium so that the activity of the heterologous CAT constructs was solely dependent upon the reduced endogenous TGFα level in clone U, the pBL-3/4-CAT construct showed markedly reduced activity compared to that seen in the presence of exogenous EGF. In contrast, the activities of the pBL-1/2-CAT and pBL-5/6-CAT constructs in clone U were not affected by the removal of EGF from the medium. This experiment localizes the TGFα autoregulatory element to between −225 and −201 of the TGFα promoter.

FIG. 5.

Localization of the TGFα autoregulatory element within the TGFα promoter. (A) The TGFα promoter-TK heterologous constructs pBL-1/2-tk-CAT (containing −247 to −225 of the TGFα promoter) and pBL-3/4-tk-CAT (containing −225 to −199 of the TGFα promoter) and the control vector pBLCAT2 were transiently transfected into TGFα antisense clone U. At 12 h, half the transfected cells were switched to serum-free medium minus EGF (−), the rest being maintained in EGF-containing medium (+). Cells were harvested for CAT assay 48 h later. (B) CAT activities of the pBL-1/2-tk-CAT and pBL-3/4-tk-CAT constructs in TGFα-revertant-phenotype clone UX and NEO-transfected control cells. CAT activities were again measured in the presence (+) and absence (−) of EGF.

TABLE 1.

Fold differences in CAT activities in the presence and absence of EGF

| Cell clone | Mean CAT activity ± SEM (n = 3) with construct:

|

Mean CAT activity (n = 2) with construct pBL-(5/6)-CAT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pBL-CAT 2 | pBL-(1/2)-CAT | pBL-(3/4)-CAT | ||

| NEO | 0.89 ± 0.16 | 0.94 ± 0.08 | 1.03 ± 0.13 | 1.12 |

| U | 1.25 ± 0.22 | 1.09 ± 0.13 | 2.01 ± 0.25 | 1.00 |

| UX | 1.19 ± 0.01 | 0.80 ± 0.27 | 1.09 ± 0.01 | 1.15 |

Further characterization of the TGFα autoregulatory element.

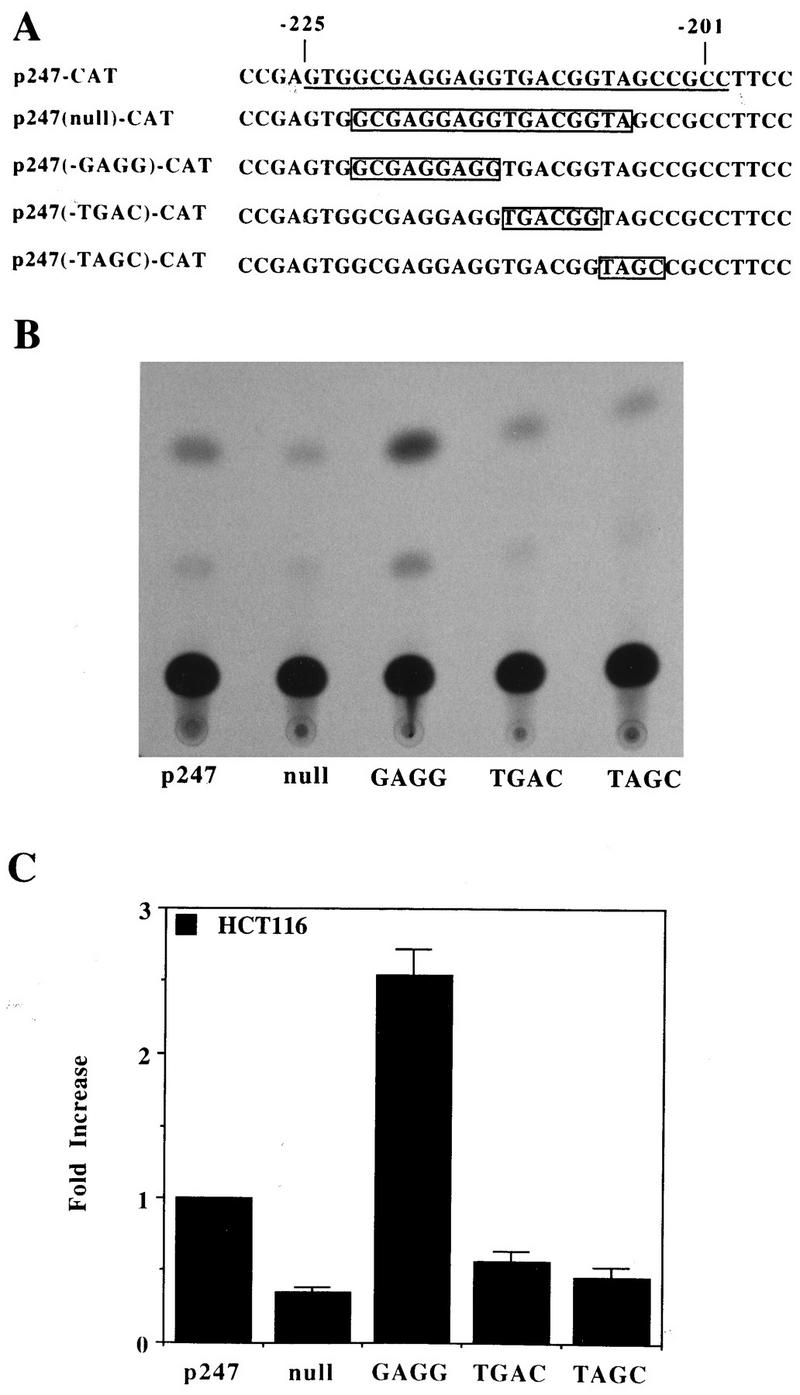

The sequence of the 25-bp autoregulatory element contains no known consensus sequences and shows no homology to previously described EGF- and TGFα-responsive sequences (Fig. 6A). Therefore, in order to further determine the importance of the TGFα autoregulatory element in the control of TGFα expression in HCT116 and to narrow down the precise regions of the 25-bp sequence involved in this regulation, deletions of this sequence within the context of the TGFα promoter were generated as shown in Fig. 6A. Deletion of the sequence TGACGG or deletion of the sequence TAGC [p247(-TGAC)-CAT and p247(-TAGC)-CAT, respectively] (Fig. 6) resulted in constructs with reduced promoter activities compared to that of the parental p247-CAT vector (Fig. 6B and C). However, deletion of the CGAGGAGG sequence [the p247(-GAGG)-CAT construct] (Fig. 6) resulted in a construct with two- to threefold increased promoter activity compared to that of the parental p247-CAT vector (Fig. 6B and C). Therefore, there appears to be an activator binding region within the TGFα autoregulatory element, centered on the TGACGG and TAGC sequences. There also appears to be a repressor binding region within the sequence GCGAGGAGG.

FIG. 6.

Further characterization of the 25-bp TGFα autoregulatory element. (A) Sequence of the TGFα autoregulatory element. The sequence −201 to −225 in the parental p247-CAT vector is underlined. Underneath, the boxed sequences represent the bases which were deleted from the p247-CAT plasmid to generate the various Ex-Site PCR deletion constructs. (B) CAT activities of the Ex-Site PCR deletion plasmids in the HCT116 cell line. The plasmids illustrated in panel A were transiently transfected into HCT116 cells maintained in the absence of EGF. Cells were harvested for the CAT assay 48 h after transfection. (C) Quantitation of the CAT activities of the Ex-Site PCR deletion plasmids in HCT116 cells. The scan activity of the parental p247-CAT vector was normalized to 1. The data are presented as means ± standard errors of the means (n = 3).

When we made an 18-bp deletion containing the sequence GCGAGGAGGTGACGGTA, which represents −206 to −222 of the TGFα autoregulatory element and which deletes or disrupts all three previously described sequences [designated the p247(null)-CAT construct] (Fig. 6A), a construct with very low promoter activity was generated. This p247(null)-CAT construct shows approximately 20% of the CAT activity of the parental p247-CAT construct. Therefore, although a major repressor binding site within the TGFα autoregulatory element is lost, in the absence of the putative activator binding regions, the TGFα promoter shows very little activity.

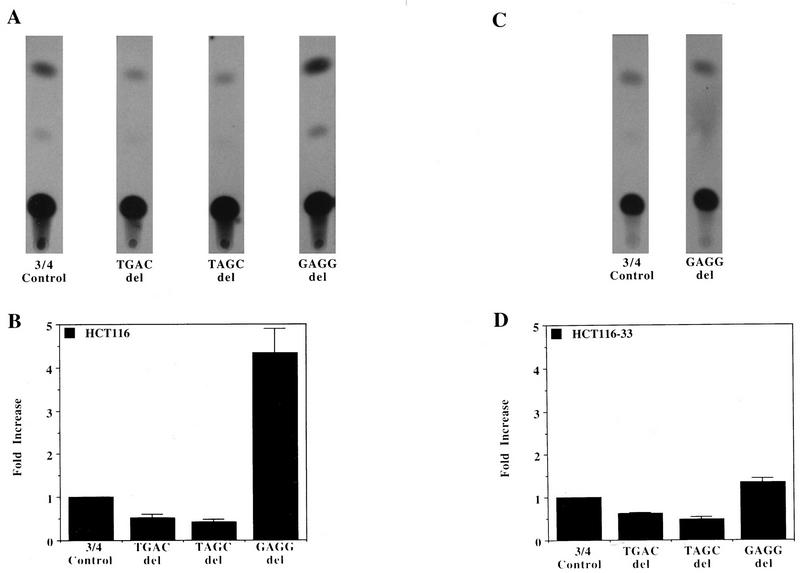

The effects of these deletions on heterologous promoter activity were also examined to test whether or not they were specific for the TGFα promoter. For these studies, the AML65 heterologous promoter was used. The low basal CAT activity of this promoter facilitated detection of deletion constructs, resulting in increased CAT activity. The deletions used in the oligonucleotides are described in detail in the legend to Fig. 7. The results of a typical transient-transfection experiment with the HCT116 cell line is shown in Fig. 7A. As in the previous studies, when the TGAC or TAGC sequence was deleted from the 25-bp autoregulatory element, reduced activity was conferred on the heterologous AML65 promoter. However, when the GAGGAG sequence was again deleted from the 25-bp sequence, the activity of the heterologous construct was increased two- to threefold.

FIG. 7.

Characterization of the effect of TGFα autoregulatory element deletions on heterologous-promoter activity. Oligonucleotide 3/4, sequence GTGGCGAGGAGGTGACGGTAGCCGC; the TGAC deletion oligonucleotide, sequence GTGGCGAGGAGGGTAGCCGC; the TAGC deletion oligonucleotide, sequence GTGGCGAGGAGGTGACGG; and the GAGG deletion oligonucleotide, sequence GTGGCGTGACGGTAGCCGC were synthesized, hybridized, and cloned just upstream of the pAML65 promoter as described in Materials and Methods. (A) CAT activities of the oligonucleotide deletion constructs in the HCT116 cell line; (B) quantitation of the CAT activities of the oligonucleotide deletion constructs in the HCT116 cell line. The activity of the native TGFα autoregulatory element represented by oligonucleotide 3/4 (the p-3/4-AML65-CAT plasmid) was normalized to 1. Data are presented as means ± standard errors of the means (n = 4). (C) CAT activities of oligonucleotide 3/4 and the GAGGAG deletion construct in TGFα-antisense-mRNA-expressing clone 33; (D) graphical presentation of the activities of the deletion and heterologous-promoter constructs in clone 33. Again, the CAT activity of the p3/4-AML65-CAT plasmid was normalized to 1. Scan data are presented as means ± standard errors of the means (n = 4). 3/4, oligonucleotide 3/4; del, deletion; HCT116-33, HCT116 cells with clone 33.

These heterologous-promoter deletion constructs were also transfected into TGFα antisense clone 33. Deletion of the TGAC or TAGC sequence again resulted in constructs with reduced CAT activities in clone 33 compared to that in the heterologous-promoter construct containing the complete 25-bp TGFα autoregulatory sequence (Fig. 7D). However, the most notable difference between the antisense clone and HCT116 is that deletion of the repressor binding sequence GAGGAG does not result in induction of CAT activity in the antisense clone (Fig. 7C and 7D). There are two possible interpretations of this data. First, there may be decreased repressor activity in clone 33, such that deletion of the GAGGAG sequence has no marked effect on the promoter activity. This result implies that repressor expression is regulated by TGFα. Second, clone 33 still contains a significant amount of repressor, but when the GAGGAG sequence is deleted, there is no associated increase in promoter activity because the amount of activator(s) binding to the TGAC and TAGC sequences is very low in clone 33. Therefore, there is very little promoter activity to be repressed in clone 33 due to the low level of activator(s).

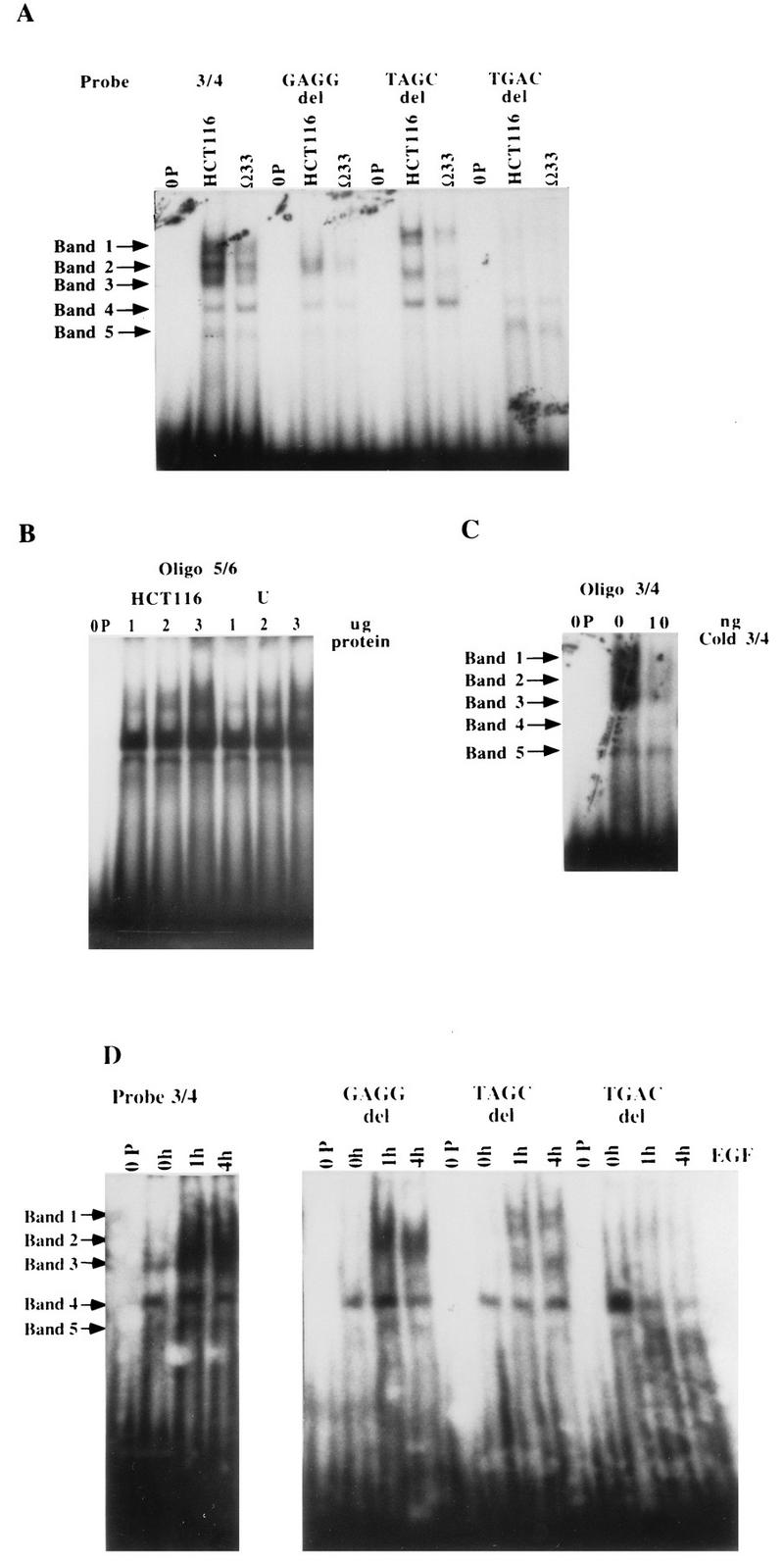

Gel shift analysis.

When equivalent amounts of protein from the NEO and clone 33 extracts prepared from EGF-deprived cells were run in a gel shift assay with 32P-labelled oligonucleotide 3/4 (the TGFα autoregulatory element) as the probe, several putative autocrine-TGFα-regulated bands were observed (Fig. 8A). These comprised three major low-mobility-shift bands, called bands 1, 2, and 3 (Fig. 8A), and a minor high-mobility-shift band, called band 5. Another high-mobility-shift complex, band 4, was not regulated by the level of TGFα autocrine activity.

FIG. 8.

Gel shift assay with the TGFα autoregulatory element. (A) Gel shift analysis of complexes formed with the TGFα autoregulatory element (oligonucleotide 3/4 [3/4]) and the GAGG, TAGC, and TGAC deletions (del) of this element. Equivalent amounts of nuclear extract protein (3 μg) from HCT116 control cells and TGFα antisense clone 33 were run against the various 32P-labelled oligonucleotides. 0P denotes the lanes containing probe run without protein; Ω33 denotes the lanes containing probe run with clone 33. (B) Gel shift analysis of complexes formed with control oligonucleotide 5/6. Equivalent amounts of nuclear extract protein (3 μg) from control HCT116 cells and TGFα antisense cells were run against 32P-labelled oligonucleotide 5/6, which contains −201 to −176 of the TGFα promoter sequence. This sequence does not participate in EGF or TGFα regulation and does not confer EGF or TGFα responsiveness to a heterologous-promoter construct. (C) Specificity of nuclear protein binding to the TGFα autoregulatory element. Nuclear extract (3 μg protein) was run against 32P-labelled oligonucleotide 3/4 in the presence (10 ng) or absence (0 ng) of cold competing oligonucleotide 3/4 (Cold 3/4). (D) Effect of exogenous EGF on nuclear protein binding in TGFα antisense clone 33. Equivalent amounts of nuclear extract protein from TGFα antisense clone 33 cells maintained without EGF or treated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for 1 or 4 h prior to harvest were run against the 32P-labelled TGFα autoregulatory element (oligonucleotide 3/4) or the GAGG, TAGC, and TGAC deletion oligonucleotides described in the legend to Fig. 7. 0h, 1h, and 4h denote the durations of EGF treatment.

When the deletion sequences are used as probes, specific changes occur in the pattern of binding of bands 1, 2, and 3 (Fig. 8A). When the GAGGAG sequence is deleted from oligonucleotide 3/4, complexes 1 and 3 disappear, whereas when the TAGC sequence is deleted from oligonucleotide 3/4, band 2 disappears. Deletion of the TGAC sequence results in the loss of bands 1, 2, and 3. The regulation of these bands by autocrine TGFα appears to be specific for oligonucleotide 3/4, which contains the TGFα autoregulatory element. When downstream oligonucleotide 5/6 (−201 to −176 of the TGFα promoter), which is not TGFα regulated, is used as the probe, no difference in binding is seen between HCT116 control and antisense-TGFα nuclear extracts (Fig. 8B). In the presence of excess unlabelled oligonucleotide 3/4, binding of bands 1 to 3 to the autoregulatory element is abolished (Fig. 8C), providing evidence that these are the specific bands of interest.

If the differences in the bands produced by nuclear extract binding of the TGFα antisense clone is a function of repression of TGFα autocrine activity, then addition of exogenous EGF to the antisense clone should alter binding in a manner consistent with autocrine-TGFα regulation of the bands. The result of such an experiment is shown in Fig. 8D. The addition of EGF to TGFα antisense clone 33 cells results in increased binding in bands 1, 2, and 3 by 1 h. This increase persists for at least 4 h following EGF treatment, and the time course of these changes is the same as that of EGF stimulation of TGFα mRNA in these cells (Fig. 2). The same pattern of bands binding the TGFα autoregulatory sequence (oligonucleotide 3/4) and the deletion sequences does not change following EGF addition, but the amount of binding activity in these bands is EGF regulated. Again, both the putative activator (band 2) and repressor (bands 1 and 3) appear to be increased by exogenous EGF in clone 33 in a manner which is consistent with the effect of autocrine TGFα in the HCT116 and TGFα antisense cell lines.

Effect of EGF on TGFα production in an exogenous growth factor-dependent cell line.

The well-differentiated FET cell line expresses a classical, externalized TGFα autocrine loop, and its growth can be inhibited by blocking antibodies to TGFα or EGFR (33, 34). While this TGFα autocrine loop is sufficient to maintain some growth of these cells in media lacking EGF, exogenous EGF is required for optimal growth of these cells. Addition of exogenous EGF to these cells stimulates TGFα mRNA production at 4 h following treatment (Fig. 9A). This induction is augmented in the presence of cycloheximide, which is characteristic of immediate-early genes (19, 20).

FIG. 9.

Effect of exogenous EGF on TGFα regulation in growth factor-dependent cells and effect of EGF and cycloheximide on TGFα mRNA expression. (A) Growth factor-dependent FET cells maintained in the absence of EGF were treated with EGF (10 ng/ml) or cycloheximide (10 μg/ml) for 4 h prior to harvest. Total RNA was prepared and used in a RNase protection assay as described in Materials and Methods. Control, no EGF treatment; EGF, 4 h of EGF treatment; CHX, 4 h of cycloheximide treatment; EGF+HEX, 4 h of treatment with EGF and cycloheximide. (B) Gel shift of effect of EGF on nuclear protein binding to the TGFα autoregulatory element in FET cells. FET cells were maintained in serum-free medium minus EGF. Some cells were treated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for 1 or 4 h (lane 1h or 4h, respectively) prior to harvest. These nuclear extracts were run in a gel shift assay with the TGFα autoregulatory element (oligonucleotide 3/4) as the probe. Lane 0P, probe without protein.

Nuclear extracts from these cells show a binding pattern similar to that of HCT116 cells (Fig. 9B). Significantly, when EGF is added to EGF-deprived cells, the binding activities of bands 1 to 3 to the TGFα autoregulatory element are again increased by 1 h following treatment and continue at a sustained level through 4 h.

DISCUSSION

Increased TGFα autocrine activity contributes to the loss of growth regulation associated with the transformed phenotype (13, 25, 39, 40), and HCT116 cells provide a good example of autocrine-TGFα-mediated growth factor independence (21). The importance of EGFR activation in TGFα action has been established by the use of neutralizing antibodies to the receptor (16, 23, 28, 31). This activation of EGFR by TGFα not only elicits growth responses but also results in autostimulation of further TGFα production (3, 8, 9, 47). Clearly, TGFα autostimulation plays an important role in maintaining TGFα expression and the associated uncontrolled growth of the transformed phenotype by abrogating the need for exogenous growth factors in HCT116 cells (21, 33). However, although the TGFα promoter has been cloned, little is known about the molecular events triggered by TGFα activation of the EGFR which result in this autoregulation of TGFα expression. More importantly, the potential sites of deregulation of TGFα expression in the transformed phenotype have not been identified. Therefore, we studied TGFα promoter regulation in the highly tumorigenic colon carcinoma cell line HCT116, which demonstrates a high degree of exogenous growth factor independence due to a TGFα autocrine activity (21, 33,34). This cell line is not inhibited by neutralizing antibodies to EGFR, but the importance of TGFα autocrine function in this progressed phenotype was demonstrated by constitutive TGFα-antisense-RNA expression. The TGFα-antisense-RNA-expressing clones required exogenous growth factors, including EGF and TGFα, for growth and showed reduced TGFα mRNA and protein levels as well as reduced tumorigenic properties both in vitro and in vivo (21). We used the HCT116 cell line and the TGFα antisense clones as a paradigm for studying TGFα regulation by autocrine TGFα in a progressed versus a less progressed cell line.

Using this model system, we localized the TGFα autostimulatory element to a 25-bp DNA sequence from bp −201 to −225 of the TGFα promoter. Moreover, in the growth factor-dependent clones, this element was responsive to the presence of EGF in the medium. This finding is in agreement with the findings of Raja et al. (36), who localized EGF responsiveness to the first 313 bp of the TGFα promoter. Further deletion studies of the 25-bp autoregulatory element revealed that transcriptional control by this sequence is complex. Deletions of either the TGAC or TAGC sequence within the element resulted in constructs with promoter activities lower than those of constructs with the full 25-bp TGFα autoregulatory element, either within the context of the native TGFα promoter sequence or in heterologous-promoter deletion constructs transfected in the HCT116 cell line. Clearly these sequences bind an activator(s) of TGFα promoter activity. Deletion of a third sequence, the GAGGAG sequence, resulted in constructs with increased basal activities compared to that of the 25-bp wild-type sequence, both in the context of the native TGFα promoter sequence and heterologous-promoter constructs transfected in HCT116 cells. Therefore, there is also a repressor associated with the TGFα autoregulatory element. When all three sequences were deleted within the context of the TGFα promoter [the p247(null)-CAT plasmid] a construct with very low promoter activity was generated, indicating that this 25-bp sequence may represent the core promoter.

In TGFα antisense clone 33, deletion of either the TGAC or TAGC sequence within the 25-bp sequence attached to the heterologous AML65 promoter again resulted in loss of CAT activity compared to that of the wild-type 25-bp autoregulatory element. However, in the antisense clone, deletion of the GAGGAGG sequence did not result in increased promoter activity compared to that of the wild-type 25-bp sequence. Gel shift analysis revealed specific complexes bound by the repressor binding sequence (bands 1 and 3), which disappeared on deletion of this GAGGAG sequence. There were smaller amounts of this complex in the TGFα antisense clone 33 nuclear extracts than in the HCT116 NEO nuclear extracts. Therefore, the amount of repressor appears to be decreased in the TGFα antisense clones. Deletion of the sequence then should not have as marked an effect on promoter activity in the TGFα antisense clones as in HCT116. However, the gel shift assay also shows that there is less activator(s) binding in the specific complex (band 2) in the TGFα antisense clones and that binding completely disappears on deletion of the TGAC or TAGC sequence. These findings also explain the lack of increased promoter activity on deletion of the GAGGAG sequence from the 25-bp element in TGFα antisense clone 33. Thus, both mechanisms may contribute to the lack of activation of the GAGGAG deletion element in the TGFα-antisense-mRNA-expressing clone.

When the TAGC sequence is deleted, only band 2 disappears. This binding activity may result from an activator. When the TGAC sequence is deleted, bands 1, 2, and 3 disappear. Therefore, the TGAC sequence may be shared by both the activator and repressor and be essential for both to bind. It should be noted that when activator binding is lost due to TAGC deletion, the binding activities in bands 1 and 3 are decreased. Therefore, activator binding may affect repressor binding in a positive fashion. Such complex interactions between transcription factors have been shown in other systems (46). For example, stimulation of transcription of the c-fos gene by serum can be mediated by serum response factor (SRF) bound at the SRF site. However, stimulation by other mitogens requires both SRF and the ternary complex factor, which binds at an adjacent site. However, ternary complex factor cannot bind independently of SRF.

The stimulation of CAT activity and nuclear extract binding by EGF in clone U provides evidence that it is the loss of TGFα autocrine activity in the TGFα antisense cells rather than growth state which is directly responsible for the regulation of the TGFα promoter. The change in binding of the trans-acting factors in response to EGF occurs too early to be a consequence of a growth response of the cell. Further evidence for this comes from the effects of exogenous EGF and cycloheximide in growth factor-deprived FET cells. Exogenous EGF stimulates TGFα mRNA production at 4 h and protein binding to the TGFα autoregulatory element at 1 to 4 h. These cells actively grow, although not optimally in the absence of EGF. Significantly, cycloheximide augments not only TGFα mRNA production itself as has been reported for keratinocytes (35) but also the TGFα mRNA response to EGF. This finding suggests that the responses induced by autocrine TGFα or exogenous EGF are immediate-early responses (19, 20), again suggesting that TGFα promoter regulation in clone U is not due to cell growth state.

The putative activator and repressor functions are regulated both by autocrine TGFα and by exogenous EGF. Autocrine TGFα and exogenous EGF stimulate increased binding of the putative activator as was expected for an EGF- or TGFα-responsive transcription factor. However, the role of the TGFα- or EGF-regulated repressor binding activity is less clear. Overexpression of TGFα results in the first step of cellular transformation (8, 13). Autostimulation of TGFα promoter activity would lead to high levels of TGFα if no feedback systems regulated the response. One level of control is by downregulation of EGFR following TGFα stimulation. Autocrine-TGFα regulation of repressor binding activity to the TGFα promoter would provide another negative feedback function which might also be dependent on the presence of activator binding activity.

The loss of TGFα transcriptional activator must also contribute to decreased TGFα mRNA production in the TGFα antisense clones. Previous studies characterizing these TGFα antisense clones showed duplex formation of the sense and antisense TGFα RNAs (21). Most likely, both mechanisms contribute to the development of the growth factor-dependent phenotype in the TGFα antisense clones. Duplex formation decreases the amount of TGFα protein which is translated due to loss of TGFα mRNA (21), which then decreases expression of the TGFα promoter transcriptional activator and results in the decreased TGFα promoter activity observed in the antisense clones. Decreased endogenous TGFα stimulation of transactivator production may then allow for stimulation by exogenous EGF, which would explain the responsiveness of the TGFα promoter to exogenous EGF in TGFα-antisense-RNA-expressing cells.

Another feature of the decrease in TGFα promoter activity observed when the TGAC or TAGC sequence is deleted is that the resulting two- to threefold reduction is consistent with the increased physiological responses of TGFα mRNA and protein as well as of other promoters to EGF or TGFα treatment. Thus, stimulation by exogenous EGF produces a two- to fourfold stimulation of TGFα mRNA in several different growth factor-dependent cell lines (3, 8, 9), and the gastrin promoter shows a two- to threefold increase in activity in response to exogenous EGF in cultured pituitary cells (32). Moreover, the level of TGFα mRNA induction by exogenous EGF in the TGFα antisense clones described here is two- to threefold.

The binding of the activators to this sequence is TGFα dependent, but it is not clear whether this binding changes in response to transcriptional upregulation of the trans-acting factors or whether other posttranscriptional modifications of these transactivators downstream of EGFR signal transduction might also affect binding and/or activator activity. Certainly, the major specific proteins binding the 25-bp TGFα autoregulatory sequence appear as doublets, which may reflect such posttranslational modifications.

The sequence of the TGFα autoregulatory element is unique, as the 25-bp DNA sequence in which it is located shows no homology to other previously described EGF response elements. These include the GC-rich, AP-2 like elements reported within the gastrin and Egr-1 promoters (5, 32, 41, 44). Indeed, although there are potential AP-2 sites within the TGFα promoter, they are all upstream of the region which we have identified as the TGFα response element (24). Another element which has been reported to mediate EGF responsiveness is the AP-1 site (1, 10, 17, 30). This element binds homodimers of the jun family or heterodimers of jun and fos. Again, no consensus AP-1 site is present in the DNA sequence containing the TGFα autoregulatory element. This element also differs from the class of EGF response elements shared by the prolactin and tyrosine hydroxylase genes (15, 26). Furthermore, it is not homologous to the EGF response element within the EGFR promoter (22). Therefore, the TGFα autoregulatory element probably represents a unique sequence for response to EGFR activation. The repressor region also represents a unique transcription control element.

The 25-bp TGFα autoregulatory element described here may represent a key site for loss of normal TGFα regulation. The TGFα antisense model described here suggests a biological paradigm in which the autocrine-TGFα-regulated transcriptional activator(s) may act as a potential oncogene to cause overexpression or inappropriate expression of TGFα in G0/G1 cells and so cause deregulation of growth. Thus, HCT116 cells upregulate TGFα expression during growth arrest and the acquisition of quiescence whereas the less progressed colon carcinoma cell line FET downregulates TGFα expression during quiescence (33, 34). However, it is also possible that loss of repressor function which would parallel loss of a tumor suppressor gene might occur in some cell systems. This loss of repressor function would be in line with the possible function of the repressor as a physiological brake on TGFα promoter activation. Excessive TGFα production in response to normal physiological stimuli may lead to the first stages of transformation, and the repressor might function to limit TGFα production.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Jenny Zak and Suzanne Payne for typing the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA34432 and CA54807.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angel P, Imagawa M, Chiu R, Stein B, Imbra R J, Rahmsdorf H J, Jonat C, Herrlich P, Karin M. Phorbol ester-inducible genes contain a common cis element recognized by a TPA-modulated trans-acting factor. Cell. 1987;49:729–739. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90611-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjorge J D, Paterson A J, Kudlow J E. Phorbol ester or epidermal growth factor (EGF) stimulates the concurrent accumulation of mRNA for the EGF receptor and its ligand transforming growth factor-α in a breast cancer cell line. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4021–4027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blasband A J, Rogers K T, Chen X, Azizkhan J C, Lee D C. Characterization of the rat transforming growth factor alpha gene and identification of promoter sequences. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:2111–2121. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.5.2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd D D, Levine A E, Brattain D E, McKnight M K, Brattain M G. A comparison of growth requirements for two human intratumoral colon carcinoma cell lines in monolayer and soft agarose. Cancer Res. 1988;48:2469–2474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao X, Koski R A, Gashler A, McKiernan M, Morris C F, Gaffney R, Hay R V, Sukhatme V P. Identification and characterization of the Egr-1 gene product, a DNA-binding zinc finger protein induced by differentiation and growth signals. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1931–1939. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.5.1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carpenter G, Cohen S. Epidermal growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:7709–7712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chirgwin J M, Przybyla A E, Mackondla R J, Rutter W J. Isolation of biologically active ribonucleic acid from sources enriched in ribonuclease. Biochemistry. 1979;18:5294–5299. doi: 10.1021/bi00591a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffey R J, Derynck R, Wilcox J N, Bringman T S, Goustin A S, Moses H L, Pittelkow M R. Production and auto-induction of transforming growth factor-α in human keratinocytes. Nature. 1987;328:817–820. doi: 10.1038/328817a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coffey R J, Jr, Graves-Deal R, Dempsey P J, Whitehead R H, Pittelkow M R. Differential regulation of transforming growth factor α autoinduction in a non-transformed and transformed epithelial cell. Cell Growth Differ. 1992;3:347–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curran T, Franza B R., Jr Fos and Jun: the AP-1 connection. Cell. 1988;55:395–397. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeLarco J E, Todaro G J. Growth factors from murine sarcoma virus-transformed cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:4001–4005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.4001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derynck R. The physiology of transforming growth factor-α. Adv Cancer Res. 1992;58:27–52. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60289-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derynck R, Goeddel D V, Ullrich A, Gutterman J U, Williams R D, Bringman T S, Berger W H. Synthesis of messenger RNAs for transforming growth factors α and β and the epidermal growth factor receptor by human tumors. Cancer Res. 1987;47:707–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dignam J D, Lebowitz R M, Roeder R G. Accurate transcription initiation by polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elsholtz H P, Mangalam H J, Potter E, Albert V R, Supowit S, Evans R M, Rosenfeld M G. Two different cis-active elements transfer the transcriptional effects of both EGF and phorbol esters. Science. 1986;234:1552–1557. doi: 10.1126/science.3491428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ennis B W, Valverius E M, Bates S E, Lippman M E, Bellot F, Kris R, Schlessinger J, Masui H, Goldenberg A, Mendelsohn J, Dickson R B. Anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies inhibit the autocrine-stimulated growth of MDA-468 human breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;3:1830–1838. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-11-1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisch T M, Prywes R, Roeder R G. An AP1-binding site in the c-fos gene can mediate induction by epidermal growth factor and 12-O-tetradecanoyl phorbol-13-acetate. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1327–1331. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.3.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorski K, Carneiro M, Schibler U. Tissue-specific in vitro transcription from the mouse albumin promoter. Cell. 1986;47:767–776. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90519-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenberg M E, Hermanowski A L, Ziff E B. Effect of protein synthesis inhibitors on growth factor activation of c-fos, c-myc, and actin gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:1050–1057. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.4.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenberg M E, Ziff E B. Stimulation of 3T3 cells induces transcription of the c-fos proto-oncogene. Nature. 1984;311:433–438. doi: 10.1038/311433a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howell G M, Ziober B L, Humphrey L E, Willson J K V, Sun L, Lynch M, Brattain M G. Regulation of autocrine gastrin expression by the TGFα autocrine loop. J Cell Physiol. 1995;162:256–265. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041620211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudson L G, Thompson K L, Xu J, Gill G N. Identification and characterization of a regulated promoter element in the epidermal growth factor receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7536–7540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imanishi K-I, Yamaguchi K, Kuranami M, Kyo E, Hozumi T, Abe K. Inhibition of growth of human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines by anti-transforming growth factor-α monoclonal antibody. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:220–223. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakobovits E B, Schlokat U, Vannice J L, Derynck R, Levinson A D. The human transforming growth factor alpha promoter directs initiation from a single site in the absence of a TATA sequence. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:5549–5554. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.12.5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee L W, Raymond V W, Tsao M-S, Lee D C, Earp H S, Grisham J W. Clonal cosegregation of tumorigenicity with overexpression of c-myc and transforming growth factor α genes in chemically transformed rat liver epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 1991;51:5238–5244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis E J, Chikaraishi D M. Regulated expression of the tyrosine hydroxylase gene by epidermal growth factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:3332–3336. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.9.3332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lynch M J, Pelosi L, Carboni J M, Merwin J, Coleman K, Wang R R C, Lin P F M, Brattain M G. Transforming growth factor β1 induces transforming growth factor-α (TGFα) promoter activity and TGFα secretion in the human colon adenocarcinoma cell line FET. Cancer Res. 1994;53:4041–4047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malden L T, Novak U, Burgess A W. Expression of transforming growth factor alpha messenger RNA in the normal and neoplastic gastro-intestinal tract. Int J Cancer. 1989;43:380–384. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. pp. 202–203. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDonnell S E, Kerr L D, Matrisian L M. Epidermal growth factor stimulation of stromelysin mRNA in rat fibroblasts requires induction of proto-oncogenes c-fos and c-jun and activation of protein kinase C. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:4284–4293. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.8.4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markowitz S D, Molkentin K, Gerbic C, Jackson J, Stellato T, Willson J K V. Growth stimulation by co-expression of transforming growth factor-α and epidermal growth factor-receptor in normal and adenomatous human colon epithelium. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:356–362. doi: 10.1172/JCI114709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merchant J L, Demediuk B, Brand S J. A GC-rich element confers epidermal growth factor responsiveness to transcription from the gastrin promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:2686–2696. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.5.2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mulder K M, Brattain M G. Effects of growth stimulatory factors on mitogenicity and c-myc expression in poorly differentiated and well differentiated human colon carcinoma cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;3:1215–1222. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-8-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mulder K M, Brattain M G. Growth factor expression and response in human colon carcinoma cells. In: Augenlicht L, editor. The cell and molecular biology of colon cancer. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1989. pp. 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pittelkow M R, Lindquist P B, Abraham R T, Graves-Deal R, Derynk R, Coffey R J. Induction of transforming growth factor-α expression in human keratinocytes by phorbol esters. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5164–5171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raja R H, Paterson A J, Shin T H, Kudlow J E. Transcriptional regulation of the human transforming growth factor-α gene. Mol Endocrinol. 1991;5:514–520. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-4-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saeki T, Gistiano A, Lynch M J, Brattain M, Kim N, Normanno N, Kenney N, Ciardiello F, Salomon D S. Regulation by estrogen through the 5′-flanking region of the transforming growth factor α gene. Mol Endocrinol. 1991;5:1955–1963. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-12-1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheidereit C, Heguy A, Roeder R G. Identification and purification of a human lymphoid-specific octamer-binding protein (OTF-2) that activates transcription of an immunoglobulin promoter in vitro. Cell. 1987;51:783–793. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sizeland A M, Burgess A W. The proliferative and morphologic responses of a colon carcinoma cell line (LIM 1215) require the production of two autocrine factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:4005–4014. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.8.4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sizeland A M, Burgess A W. Anti-sense transforming growth factor α oligonucleotides inhibit autocrine stimulated proliferation of a colon carcinoma cell line. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:1235–1243. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.11.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sporn M B, Roberts A B. Introduction: autocrine, paracrine and endocrine mechanisms of growth control. Cancer Surv. 1985;4:627–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sporn M B, Roberts A B. Autocrine growth factors and cancers. Nature. 1985;313:745–747. doi: 10.1038/313745a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sporn M B, Todaro G J. Autocrine secretion and malignant transformation of cells. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:878–880. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198010093031511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sukhatme V P. The Egr family of nuclear signal transducers. Am J Kidney Dis. 1991;17:615–618. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80333-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Todaro G J, Rose T M, Spooner C E, Shoyab M, Plowman G D. Cellular and viral ligands that interact with the EGF receptor. Semin Cancer Biol. 1990;1:257–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wan C-W, McKnight K M, Brattain D E, Brattain M G, Yeoman L C. Growth requirements and receptor levels for epidermal growth factor in human colon carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Lett. 1988;43:139–145. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(88)90226-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ziober B L, Willson J K V, Humphrey L E, Childress-Fields K, Brattain M G. Autocrine transforming growth factor-α is associated with progression of transformed properties in human colon cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:691–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]