Abstract

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), marked by dyspnea, cough, and sputum production, significantly impairs patients’ quality of life and functionality. Effective management strategies, particularly those empowering patients to manage their condition, are essential to reduce this burden and health care use. Digital health interventions—such as mobile apps for symptom tracking, wearable sensors for vital sign monitoring, and web-based pulmonary rehabilitation programs—can enhance self-efficacy and promote greater patient engagement. By improving self-management skills, these interventions also help alleviate pressure on health care systems.

Objective

This systematic review and meta-analysis assesses the clinical effectiveness of smartphone apps, wearable monitors, and web-delivered platforms in four COPD management areas: (1) quality of life (measured by the COPD Assessment Test [CAT] and St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire), (2) self-efficacy (assessed by the General Self-Efficacy Scale), (3) functional capacity (evaluated via the 6-minute walk test and Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale), and (4) health care use (indicated by hospital and emergency department visits).

Methods

A systematic review was conducted using predefined search terms in PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, and Web of Science up to January 26, 2025, to identify randomized trials on digital health interventions for COPD. Two reviewers independently screened studies and extracted data. Outcomes included quality of life, self-efficacy, functional status, and health care use.

Results

This review included 17 studies with 2027 participants from 11 countries. Eleven trials involved health care professionals in digital platform use, and 12 reported adherence strategies. Digital tools for COPD primarily focused on telerehabilitation (eg, video-guided exercises) and self-management systems (eg, artificial intelligence–driven exacerbation alerts). The study participants were predominantly older adults. Meta-analysis results indicated that digital health interventions significantly improved quality of life at 3 months on the CAT (mean difference [MD] −1.65, 95% CI –3.17 to –0.14; P=.03); at 6 months on the CAT (MD −2.43, 95% CI −3.93 to −0.94; P=.001) and St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (MD 3.25, 95% CI 0.69-5.81; P=.01); at 12 months on the CAT (MD −2.53, 95% CI −3.91 to −1.16; P<.001), EQ-5D (MD 0.04, 95% CI 0.01-0.07; P=.02), and EQ-5D visual analogue scale (MD 5.88, 95% CI 0.38-11.37; P=.04); the General Self-Efficacy Scale at 3 months (MD 1.65, 95% CI 0.62-2.69; P=.002) and 6 months (MD 1.94, 95% CI 0.83-3.05; P<.001); and the Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale at more than 3 months (MD −0.23, 95% CI −0.36 to −0.11; P=.003). However, no significant differences were observed in the 6-minute walk test, emergency department admissions, hospital admissions, emergency department admissions for COPD, or hospital admissions for COPD.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that digital health interventions may benefit COPD patients, but their clinical effectiveness remains uncertain. Further robust studies are needed, particularly those involving larger numbers of older adults with COPD.

Trial Registration

PROSPERO CRD420251032053; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251032053

Keywords: mobile health, mHealth, telemedicine, self-management, remote patient monitoring, chronic respiratory disease, evidence synthesis

Introduction

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the third leading global cause of mortality, imposes a disproportionate burden on low- and middle-income countries, where >90% of its 384 million cases occur [1,2]. In China alone, COPD affects 13.7% of adults aged ≥40 years, driving substantial disability and health care expenditures that threaten household economic stability [3,4]. While current guidelines emphasize multidisciplinary care, systemic barriers such as workforce shortages and fragmented care pathways limit implementation, particularly in resource-constrained settings [5].

The growing imperative for scalable, patient-centered solutions has catalyzed interest in digital health technologies. Telehealth platforms, wearable sensors, and artificial intelligence (AI)–driven predictive tools now enable remote symptom monitoring, personalized rehabilitation, and real-time clinician-patient communication, potentially overcoming geographical and financial access barriers [6,7]. Accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, these innovations align with the World Health Organization’s priorities for integrating digital tools into chronic disease frameworks [8].

Despite proliferating trials evaluating COPD-focused digital interventions ranging from smartphone-based pulmonary rehabilitation to smart inhalers with adherence tracking, critical evidence gaps persist. Earlier reviews either examined narrow subsets (eg, telemonitoring alone) or aggregated heterogeneous technologies (eg, combining SMS text message reminders with AI systems), obscuring the efficacy of advanced tools such as sensor-guided activity adapters or exacerbation prediction algorithms [9-12]. No synthesis has specifically assessed whether contemporary digital health tools (1) improve COPD-specific quality of life (QoL) and self-efficacy, (2) enhance functional capacity, or (3) reduce acute care use—knowledge essential for guiding clinical adoption.

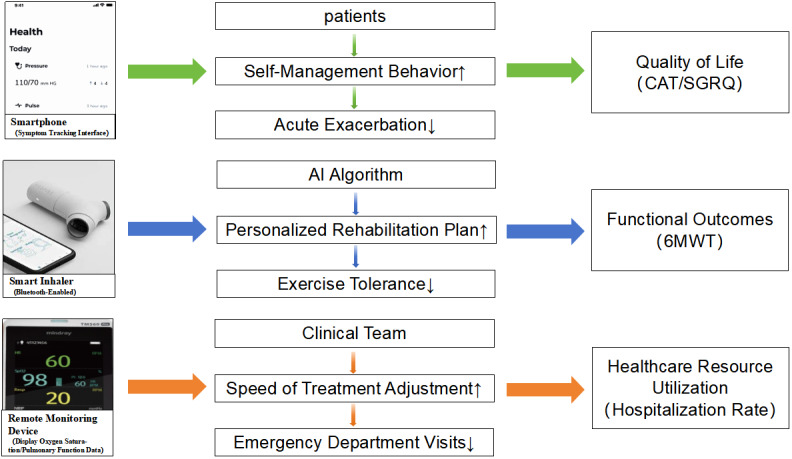

The hypothesized pathways through which digital health tools may influence COPD outcomes are illustrated in Figure 1. We propose that these interventions operate via three synergistic mechanisms: (1) enhanced self-management via mobile apps and wearable sensors, which provide real-time feedback on symptoms (eg, dyspnea thresholds) and medication adherence, enabling early detection of exacerbations, possibly reducing hospitalization risk by prompting preemptive interventions [13]; (2) personalized, AI-driven telerehabilitation platforms that adapt exercise regimens based on continuous spirometry or oxygen saturation data, potentially improving functional capacity and QoL through optimized physical activity [14]; and (3) clinician-patient synergy and remote monitoring systems to facilitate data sharing between patients and care teams, allowing timely adjustment of treatment plans (eg, corticosteroid titration during exacerbations), which could decrease emergency visits [15].

Figure 1.

Hypothesized pathways.

This framework posits that effective tools must concurrently engage patients (via behavioral nudges) and clinicians (through actionable analytics) to disrupt the cycle of COPD deterioration. This systematic review and meta-analysis addresses these gaps by evaluating rigorously designed digital health interventions targeting COPD management. By synthesizing evidence on patient-centered outcomes and health care use metrics, we aim to clarify the clinical value of these technologies and inform equitable implementation strategies.

Objective

This systematic review and meta-analysis aims to assess whether current digital health tools for COPD management can (1) improve disease-specific QoL and self-efficacy, (2) enhance functional capacity, and (3) reduce the use of acute health care services—key outcomes necessary to guide clinical adoption and policy decisions.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [16], and the PRISMA 2020 Checklist was used (Multimedia Appendix 1). The protocol for this study was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD420251032053).

Search Strategy

A systematic search of the PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, Web of Science, and Scopus databases was conducted up to January 26, 2025, to identify relevant publications. The search used combinations of keywords and indexing terms, such as MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) or Emtree, associated with the search domains. An automated electronic search was carried out using the MeSH terms identified in PubMed. The following MeSH keywords were included: “Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive” OR “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease” OR “COPD” OR “chronic obstructive lung disease” OR “chronic airflow obstruction” OR “emphysema” AND “digital health” OR “telehealth” OR “mHealth” OR “eHealth” OR “biosensor” OR “remote monitoring” OR “Smartphone” OR “Mobile Applications” OR “Apps” OR “Internet-based interventions” OR “Web-based platforms” AND “self-management” OR “self-monitoring” OR “self-care” AND “randomized controlled trial” OR “controlled clinical trial” OR “Clinical Trial.” A comprehensive search strategy for every database is outlined in Multimedia Appendix 2. Boolean operators were used to merge and cross-reference across different domains. Furthermore, a manual search was conducted by examining the reference lists of reviews on related topics and selected articles.

Eligibility Criteria

The specific eligibility requirements of inclusion criteria used the population, intervention, comparison, outcomes, and study format: (1) the population was COPD; (2) the intervention was an intervention delivered via a web-based remote digital health management system; (3) the comparison was the control group that received only the usual care interventions and the intervention group that used the web-based remote digital health management system in addition to the usual care interventions; (4) the outcomes were the impacts of the interventions on overall or at least one type of relevant health-related outcomes (eg, QoL, self-efficacy, functional outcomes, and health care use indicators); and (5) the study design was randomized controlled trials (RCTs). As the inclusion of unpublished studies can potentially introduce bias [17], this systematic review and meta-analysis only considered publications from peer-reviewed journals.

The review excluded case reports; preprint papers; letters to editors; simulation studies; published conference abstracts; research lacking adequate details on the measurement of the outcomes of interest; qualitative studies; surveys or reviews; studies describing protocols, along with those focusing solely on the interface or internal structure of apps; and studies based on web pages or websites without associated applications.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Two researchers separately reviewed the identified papers to reduce potential errors and bias throughout the selection process. Initially, the authors screened the title and abstracts of the potential papers against the set inclusion and exclusion criteria. Following this, the final selection of papers was made after thoroughly reading the complete manuscripts of the qualifying papers and their references. Any discrepancies were settled through discussions among the authors until a consensus was reached.

A structured data extraction form was used to gather the following details: the first author’s name; year of publication; study type; participant demographics (age range, sex ratio, sample size, and country); interventions for remote digital health management; intervention duration; involvement of health care professionals (HCPs); strategies implemented to ensure participant compliance; and outcomes. The corresponding authors were contacted to clarify or obtain any information that was unclear or missing.

Study Quality Evaluation

Two researchers performed the quality assessment independently. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion between the two researchers, and a third investigator independently reviewed the final decisions. The quality of the RCTs was evaluated by 2 researchers using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias [18]. This tool addresses 6 domains of bias: selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other biases. The risk of bias was classified as high, low, or unclear, with reasons provided for each classification.

Statistical Analysis

All meta-analyses were conducted using RevMan (version 5.4; Cochrane Collaboration). The statistical indicators used included the standardized mean difference (SMD), odds ratio, and 95% CI. An inverse-variance-weighted linear meta-analysis of SMD (Hedges g) was carried out to evaluate the effect size of smartphone-based remote digital health management on changes in review outcomes, such as self-efficacy/Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC)/6-minute walk test (6MWT). In general, a Hedges g value of less than 0.2 suggests a small effect, approximately 0.5 indicates a moderate effect, and greater than 0.8 signifies a strong effect. Heterogeneity among the results was assessed using the I2 statistical test. The choice between a random-effects model and a fixed-effects model was based on the heterogeneity I2 test, with I2 values below 50% indicating the use of a fixed-effects model and values above 50% suggesting the use of a random-effects model [18]. Effect sizes were compared using z tests, and a P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Selection

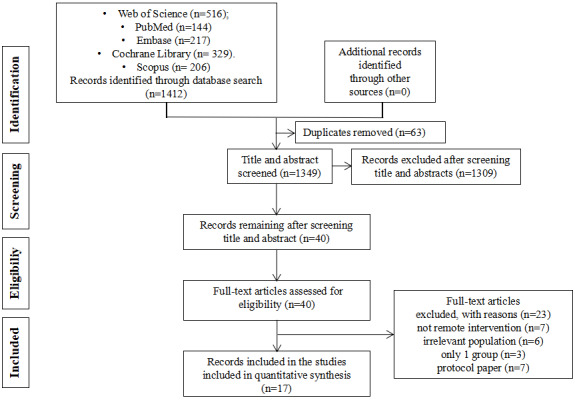

The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2) illustrates the screening process and the criteria used for excluding papers. The initial search yielded 1206 citations, from which 63 duplicates were eliminated. Following the removal of duplicates, 1143 records were evaluated against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Subsequently, 40 full-text manuscripts were examined for eligibility. Out of these 45 articles, 23 studies were excluded for various reasons. As a result, 17 records were ultimately included in this review.

Figure 2.

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) flow diagram.

Quality of Studies

Figures 3 and 4 [17,19-34] show the risk of bias judgment of the RCTs. All the studies [17,19-34] used specific random sequence generation methods. Allocation concealment was rated as having a low risk of bias in 9 (53%) trials [21,22,24-26,29-32] and unclear bias in 4 (23.5%) trials [17,19,20,23]. Given the nature of web-based remote digital health management interventions, blinding of researchers and participants is unreasonable, which inevitably leads to risk deviation. In total, only 9 trials [17,19-22,27,28,31,33] had a low risk of incomplete outcome data; it is worth noting that 14 trials [17,19-28,32-34] had a low risk of selective outcome reporting. The rates of dropout and attrition were within acceptable limits.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias graph of randomized controlled trials.

Figure 4.

Risk of bias summary of randomized controlled trials. The review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item are presented as percentages. The x-axis represents the percentage of studies that were found to have low (green), unclear (yellow), or high (red) risk of bias for each domain.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

Table 1 provides a summary of the specific information extracted from the included studies.

Table 1.

Specific information on the studies included.

| Studies | Countries | Study design | Study type | Participants, n | Age (y), mean (SD) | Intervention duration (months), n | Intervention and control arm | Involvement of health care professionals | Measures to ensure intervention adherence | Outcomes |

| Jiang et al [19], 2020 | China | Clinical outcome | RCTa | Eb: 53; Cc: 53 | E: 70.92(6.39); C: 71.83 (7.60) | 6 | Intervention: lung rehabilitation intervention plan based on WeChat; control: routine outpatient rehabilitation | Respiratory experts, clinicians, rehabilitation practitioners, nurses | Regularly calls | CATd; mMRCe; SGRQf |

| Park et al [20], 2020 | Korea | Clinical outcome | RCT | E: 22; C: 20 | E: 70.45 (9.40); C: 65.06 (11.12) | 6 | Intervention: smartphone-based self-management plan Control: telephone |

A pulmonary physician and a nurse researcher | Send SMS text message | 6MWTg; self-efficacy |

| Zanaboni et al [17], 2016 | Norway, Australia, and Denmark | Clinical outcome | RCT | E: 40; C: 40 | E: 64.9 (7.1); C: 63.5 (8.0) | 24 | Intervention: telerehabilitation; control: usual care | Physiotherapist | Send SMS text message | 6MWT, EQ-5D; mMRC, CAT; self-efficacy |

| Wang et al [21], 2021 | China | Clinical outcome | RCT | E: 39; C: 39 | E: 63.2 (7.5); C: 64.4 (7.0) | 12 | Intervention: plans based on mobile health apps; control: usual care | A respiratory nurse | Not stated | CAT; self-efficacy |

| Farmer et al [22], 2017 | England | Clinical outcome | RCT | E: 110; C: 56 | E: 69.8 (9.1); C: 69.8 (10.6) | 12 | Intervention: digital health system; control: usual care | Doctor, nurse or physiotherapist | Postal reminders; telephone contact | SGRQ; EQ-5D |

| Boer et al [23], 2019 | Netherlands | Clinical outcome | RCT | E: 35; C: 41 | E: 69.3 (8.8); C: 65.9 (8.9) | 12 | Intervention: smart mobile health program; control: paper action plan | Not stated | Regularly calls | EQ-5D; EQ-5D visual analogue scale |

| Stamenova et al [24], 2020 | Canada | Clinical outcome | RCT | E: 41; C: 20 | E: 71.98 (9.52); C: 72.78 (9.16) | 6 | Intervention: remote monitoring; control: routine | In-person follow-up appointments and access to a certified respiratory educator; a respiratory therapist | Regularly calls | Emergency department admissions or for COPDh; hospital admissions or for COPD |

| De San Miguel et al [25], 2013 | Australian | Clinical outcome | RCT | E: 36; C: 35 | E: 71; C: 74 | 6 | Intervention: remote monitoring; control: usual care | Not stated | Regularly calls | Emergency department admissions or for COPD; hospital admissions or for COPD |

| Kenealy et al [26], 2015 | New Zealand | Clinical outcome | RCT | E: 98; C: 73 | E: 62-83; C: 60-77 | 6 | Intervention: telemedicine; control: usual care | 3 respiratory physicians, 2 respiratory nurse specialists, and 1 respiratory nurse practitioner | Not stated | Self-efficacy; SGRQ |

| Nyberg et al [27], 2019 | Sweden | pilot study | RCT | E: 43; C: 40 | E: 65 (7); C: 71 (8) | 12 | Intervention: remote self-management; control: usual care | 4 asthma or COPD nurses, 1 district nurse, 1 dietician, and 1 physiotherapist | Not stated | CAT; mMRC; EQ-5D |

| Benzo et al [28], 2022 | United States | Clinical outcome | RCT | E: 188; C: 187 | E: 69.335 (9.53); C: 68.676 (9.53) | 3 | Intervention: remote monitoring; control: usual care | Not stated | Regularly calls | mMRC |

| Tabak et al [29], 2014 | Netherlands | Pilot study | RCT | E: 12; C: 12 | E: 64.1 (9.0); C: 62.8 (7.4) | 3 | Intervention: telemedicine program; control: usual care | A chest physician or nurse practitioner | Regularly calls | 6MWT; EQ-5D; EQ-5D visual analogue scale |

| Ali et al [30], 2021 | Sweden | Clinical outcome | RCT | E: 110; C: 112 | E: 71.1 (9.8); C: 70.4 (9.1) | 6 | Intervention: digital-based intervention; control: usual care | Not stated | Regularly calls | Self-efficacy |

| Moy et al [31], 2015 | United States | Clinical outcome | RCT | E: 144; C: 77 | E: 67.0 (8.6); C: 66.4 (9.2) | 3 | Intervention: internet-mediated pedometer-based intervention; control: usual care | Not stated | Not stated | SGRQ |

| Nguyen et al [32], 2009 | United States | Pilot study | RCT | E: 8; C: 9 | E: 64.0 (12); C: 72 (9) | 6 | Intervention: mobile phone –based rehabilitation; control: routine rehabilitation | Nurses | Send SMS text message | SGRQ |

| Wan et al [33], 2017 | United States | Clinical outcome | RCT | E: 57; C: 52 | E: 68.4 (8.7); C: 66.8 (7.9) | 3 | Intervention: web-based pedometer intervention; control: individual pedometer intervention | Not stated | Not stated | 6MWT; SGRQ; mMRC |

| Robinson et al [34], 2021 | United States | Clinical outcome | RCT | E: 93; C: 92 | E: 69.2 (7.2); C: 70.4 (7.3) | 6 | Intervention: web-based exercise routine intervention; control: usual care | Not stated | Follow-up, in-person assessments | 6MWT; SGRQ; mMRC |

aRCT: randomized controlled trial.

bE: experimental group.

cC: control group.

dCAT: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Assessment Test.

emMRC: Modified Medical Research Council.

fSGRQ: St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

g6MWT: 6-minute walk test.

hCOPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

A total of 17 studies were published between 2009 and 2023. All studies compared either the use of a single app/web platform or an app/web platform combined with additional participant support against a control group. Collectively, these studies involved 2027 participants, with sample sizes ranging from 17 [32] to 375 [28]. Geographically, 5 studies [28,31-34] were conducted in the United States; 2 studies in China [19,21], Australian [17,25], the Netherlands [23,29], and Sweden [27,30]; and 1 study in Korea [20], Norway [17], Denmark [17], England [22], Canada [24], and New Zealand [26]. In terms of study design, all the studies were RCTs. A total of 14 articles [17,19-26,28,30,31,33,34] reported clinical outcomes, whereas 3 [27,29,32] were pilot studies. Regarding the duration of interventions, 4 studies lasted ≤3 months [11,12,14,16], 9 studies [19,20,24-27,30,32,34] lasted between 3 and 6 months, 3 studies [17,21,27] lasted between 6 and 12 months, and 3 studies [17,22,23] lasted ≥12 months. All of the participants in these studies were aged ≥60 years.

In 15 trials, the control group received standard care without the use of the app [17,19-23,25-31,33,34]. In 1 trial, they received routine in-person follow-up appointments and access to a certified respiratory educator [24] or as per the physician’s judgment based on current guidelines [30], while in 4 trials, they were provided with leaflets [22], paper action plan [23], a COPD book [25], or an educational packet of 12 self-management themes [28]. Telephone follow-up was used in 2 trials [20,26], and in 1 trial, the control group used the same app as the intervention group but with different functionality [32].

Involvement of HCPs and Strategies to Ensure Adherence via Digital Health Tool Management Interventions

A total of 11 trials [17,19-22,24,26,27,29,30,32] included the participation of HCPs in digital health tools use, while the remaining 6 trials [23,25,28,31,33,34] did not provide specific information regarding HCP involvement in digital health tools use (Table 1). The roles of HCPs varied across the trials; in most cases, HCPs were involved in prescribing rehabilitation or self-management training for patients [19,20,22,27,29,30,32], guiding the training process [17,29], installing the digital health equipment and instructing patients on how to use them [21,22,25,26,29,30], and reviewing the data [17,22,24,26]. A total of 3 trials described approaches to enhance adherence to the digital health tools management interventions. The strategies involved checking progress [29], scheduling the follow-up meetings [30], sending regular SMS text message reminders, and making periodic phone calls [32].

Digital Health Tools’ Characteristics

Across the studies, a total of 17 distinct digital health tools were used. These tools were deployed across various types of digital platforms, including 1 WeChat official account, 5 apps, 7 websites, and 4 that did not specify the platform’s details. The functionality of these platforms varied significantly across the trials. Within the context of COPD management, digital platforms were used in 2 key areas: self-management [20-31] and rehabilitation [17,19,32-34]. Concerning self-management, most digital health platforms feature functionalities such as self-monitoring, medication reminders, health information provision, assessment, feedback, access to health services, and social support. In the realm of rehabilitation, these digital health platforms are capable of tracking various physical activities and transmitting rehabilitation-related data to a server, allowing therapists to review this information. Notably, most of these tools require additional devices to fully realize their capabilities. Furthermore, certain tools facilitate patients’ access to visual and auditory feedback on their exercises by displaying real-time information on connected device screens. An overview of digital health tools characteristics is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Digital health tools characteristics.

| Studies | Digital health tools name | General objective | Specific objectives | Devices | Main features of the digital health tools |

| Jiang et al [19], 2020 | PeR | Rehabilitation | Improve quality of life, symptoms, and exercise self-efficacy | WeChat official account |

|

| Park et al [20], 2020 | SASMP | Self-management | Self-care behavior | An Android platform (version 2.3; Gingerbread) |

|

| Zanaboni et al [17], 2016 | Not stated | Rehabilitation | Reducing hospital readmissions | A treadmill, a pulse oximeter, a tablet computer, and a holder for the tablet computer |

|

| Wang et al [21], 2021 | Not stated | Self-management | Quality of life, self-management behavior and exercise and smoking cessation behavior | No device |

|

| Farmer et al [22], 2017 | EDGE | Self-management | Improve quality of life and clinical outcomes | Android tablet computer (Samsung Galaxy Tab) running the app software and a Bluetooth-enabled oximeter probe |

|

| Boer et al [23], 2019 | Not stated | Self-management | The number of exacerbation-free weeks | A mobile phone, a pulse oximeter (CMS50D, Contec Medical Systems), a spirometer (PiKo-1 monitor, nSpire), and a forehead thermometer (FTN, Medisana AG) |

|

| Stamenova et al [24], 2020 | Not stated | Self-management | Self-management | A custom tablet computer, a Pulsewave wrist cuff monitor (which measures blood pressure), an oximeter, a weighing scale, and a thermometer |

|

| De San Miguel et al [25], 2013 | Health HUB | Self-management | Reduce the incidence of hospitalizations and EDa presentations | No device |

|

| Kenealy et al [26], 2015 | Health HUB | Self-management | Quality of life; self-care; hospital use; costs; and the experiences of patients, informal carers, and health care professionals | An LCDb |

|

| Nyberg et al [27], 2019 | COPD Web | Self-management | Increasing PAc | No device |

|

| Benzo et al [28], 2022 | Not stated | Self-management | Improves the physical and emotional disease-specific quality of life | A computer tablet, a Garmin Vivofit activity monitor and an oximeter (Nonin 3150) |

|

| Tabak et al [29], 2014 | Condition Coach | Self-management | The number of hospitalizations, length of stay, and ED visits | An accelerometer-based activity sensor (Inertia Technology, Enschede) and a smartphone (Desire S; HTC) |

|

| Ali et al [30], 2021 | Not stated | Self-management | General self-efficacy and hospitalization or death | No device |

|

| Moy et al [31], 2015 | Not stated | Self-management | Increasing PA | A computer with an internet connection; a USB port; and Windows XP, Vista, 7, or 8 |

|

| Nguyen et al [32], 2009 | Not stated | Rehabilitation | Maximal workload, 6-minute walk distance, health-related quality of life, or total steps | An Omron HJ-112 digital pedometer |

|

| Wan et al [33], 2017 | ESC | Rehabilitation | Increasing PA | An Omron HJ-720 ITC pedometer |

|

| Robinson et al [34], 2021 | Not stated | Rehabilitation | Increasing PA | Pedometer |

|

aED: emergency department.

bLCD: liquid crystal display.

cPA: physical activity.

dCOPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

ePCC: person-centered care.

Intervention Effectiveness

QoL Outcomes

An array of QoL outcomes was measured across the trials, which included a COPD Assessment Test (CAT), St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), EQ-5D and EQ-5D visual analogue scale (VAS). Assessments were conducted at 3 different time points: 3, 6, and 12 months.

At 3 months, the effects of digital health management were limited but showed some promising trends. A total of 3 studies (n=267) assessed its impact on CAT scores, revealing a mild but significant effect size (Hedges g=−1.65; mean difference [MD] −1.65, 95% CI −3.17 to −0.14; P=.03; Figure 5 [19,21,27]) with no heterogeneity (I2=0%). However, 4 studies (n=532) evaluating SGRQ scores found no significant effect (MD 4.24, 95% CI −4.33 to 12.81; P=.33; Figure 6 [31-34]) and high heterogeneity (I2=91%). Similarly, 2 studies (n=107) on EQ-5D also showed no significant improvement (MD 0.10, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.23; P=.17; Figure 7 [27,29]) with high heterogeneity (I2=92%). The overall meta-analysis (n=639) indicated that digital health management did not significantly improve QoL (SMD 0.18, 95% CI −0.15 to 0.50; P=.28; I2=80%; Figure 8 [19,21,27,29,31-34]).

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on quality of life assessed by the Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Assessment Test at 3 months.

Figure 6.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on quality of life assessed by St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire at 3 months.

Figure 7.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on quality of life assessed by EuroQol 5 Dimensions at 3 months.

Figure 8.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on quality of life at 3 months.

At 6 months, the benefits of digital health management became more pronounced. A total of 3 RCTs (n=264) examining CAT scores revealed a statistically significant benefit for the intervention group compared with controls (MD −2.43, 95% CI 3.93 to −0.94; P=.001; Figure 9 [17,19,21]), with low heterogeneity (I2=12%). In addition, 1 study on SGRQ scores also showed a significant effect (MD 3.25, 95% CI 0.69-5.81; P=.01; I2=37%; Figure 10 [19,22,26,32,34]), indicating improved symptom control and health status over time.

Figure 9.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on quality of life assessed by the Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Assessment Test at 6 months.

Figure 10.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on quality of life assessed by St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire at 6 months.

At 12 months, the positive effects observed at 6 months were sustained, with findings showing statistically significant improvements across multiple outcomes. A total of 5 studies (n=802) assessing CAT, EQ-5D, and EQ-5D VAS scores demonstrated highly significant effects in favor of digital health management (P<.05), with no or low heterogeneity (Figure 11 [17,21,27], Figure 12 [17,22,23,27], and Figure 13 [17,23]). These results suggest that long-term intervention has a sustained impact on symptom relief and overall health status improvement.

Figure 11.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on quality of life assessed by the Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Assessment Test at 12 months.

Figure 12.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on quality of life assessed by EQ-5D at 12 months.

Figure 13.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on quality of life assessed by EQ-5D VAS at 12 months.

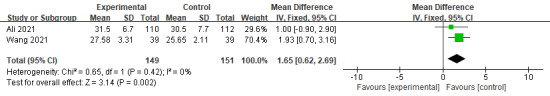

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy was also evaluated at 3, 6, and 12 months, using the General Self-Efficacy (GSE) Scale. Analysis showed significant differences at 3 months (MD 1.65, 95% CI 0.62-2.69; P=.002; Figure 14 [21,30]) and 6 months (MD 1.94, 95% CI 0.83-3.05; P<.001; Figure 15 [17,21,30]). Among the outcomes that were reported by 2 studies, no significant difference at 12 months (MD 3.12, 95% CI −2.29 to 8.53; P=.26) was observed between the two groups, with high statistical heterogeneity (I2=91%; Figure 16 [17,21]).

Figure 14.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on self-efficacy at 3 months.

Figure 15.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on self-efficacy at 6 months.

Figure 16.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on self-efficacy at 12 months.

Functional Outcomes

Dyspnea

A total of 6 studies (with a total sample size of 1392 patients) assessed the effect of digital health management on the mMRC Dyspnea Scale. The meta-analysis showed a significant difference favoring digital health management at 3 months (MD −0.23, 95% CI −0.36 to −0.11; P<.001; I2=0%; Figure 17 [19,27,28,33,34]) and at 12 months (MD −0.32, 95% CI −0.64 to 0.01; P=.05; I2=0%; Figure 18 [17,27]). However, no significant difference was observed at 6 months, with moderate heterogeneity among studies (MD −0.17, 95% CI −0.46 to 0.12; P=.26; I2=50%; Figure 19 [19,27,28,33,34]).

Figure 17.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on dyspnea at 3 months.

Figure 18.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on dyspnea at 12 months.

Figure 19.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on dyspnea at 6 months.

Six-Minute Walk Test

Meta-analysis indicated a positive trend for digital health management in 6MWT. However, no significant differences were observed between the intervention and control groups at 3 months (MD 25.01, 95% CI −45.34 to 95.36; P=.49; I2=94%; Figure 20 [29,33,34]) or at 6 months (MD −1.53, 95% CI −21.98 to 18.93; P=.88; I2=0%; Figure 21 [17,20,34]).

Figure 20.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on 6-Minute Walk Test at 3 months.

Figure 21.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on 6-Minute Walk Test at 6 months.

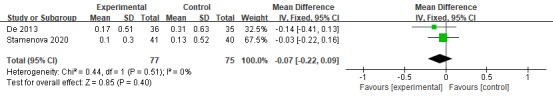

Health Care Use Indicators

Health care use indicators included emergency department admissions, hospital admissions, emergency department admissions for COPD and hospital admissions for COPD. The overall effect revealed that the digital health management intervention could not effectively reduce health care use indicators. The analysis showed no significant differences in emergency department admissions (MD −0.08, 95% CI −0.35 to 0.19; P=.57; Figure 22 [24,25]), hospital admissions (MD −0.19, 95% CI −0.44 to 0.05; P=.13; Figure 23 [24,25]), emergency department admissions for COPD (MD −0.07, 95% CI −0.22 to 0.09; P=.40; Figure 24 [24,25]), and hospital admissions for COPD (MD −0.19, 95% CI −0.39 to 0.02; P=.07; Figure 25 [24,25]), all of them with no statistical heterogeneity (I2=0%).

Figure 22.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on emergency department admissions.

Figure 23.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on hospital admissions.

Figure 24.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on emergency department admissions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Figure 25.

Meta-analysis results and forest plot of the digital health interventions on hospital admissions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Discussion

Principal Findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis aggregated data from 17 RCTs, encompassing a total of 2027 participants, to assess the efficacy of digital health interventions aimed at COPD. The digital health tools were mainly used for rehabilitation and self-management purposes. Although many trials included HCPs in the intervention process, few elaborated on strategies to maintain participant adherence throughout the intervention period. Most participants were older adults. Our study results showed that the remote digital health intervention demonstrated significant effects in improving QoL. Specifically, the CAT score showed statistically significant improvements at 3, 6 (CAT and SGRQ), and 12 months (CAT and EQ-5D and its VAS). In addition, the degree of dyspnea (mMRC) significantly decreased at 3 months and approached significance at 12 months. Self-efficacy (GSE) also improved significantly in the short term, particularly at 3 and 6 months, but no significant changes were observed at 12 months. Despite these encouraging results, no significant improvements were observed in physical performance (eg, the 6MWT) or hospitalization rates. For instance, the 6MWT did not show significant effects at either 3 months or 6 months. Similarly, although there were trends toward reduced all-cause hospitalization rates and COPD-related hospitalization rates, these did not reach statistical significance. While these results are promising, they should be interpreted with caution due to differences in digital health tools characteristics, content variability, and the diverse methodologies and clinical settings across studies, alongside generally small sample sizes.

Effects of Interventions on the Health Outcomes of Patients With COPD

QoL Outcomes

The overall effect indicated that the QoL of the group using digital health interventions was superior to that of the control group, with effects at 12 months being more pronounced than at 3 and 6 months. This sustained improvement can be attributed to the benefits of prolonged treatment without requiring a therapist’s online presence, ensuring offline monitoring of rehabilitative activities [35]. This finding aligns with the technology acceptance model [36], where prolonged exposure enhances perceived usefulness (eg, recognizing the role of tools in exacerbation prevention). However, early dropout may reflect low perceived ease of use among older users struggling with multidevice complexity. Therefore, while sustained engagement leads to better health outcomes, addressing usability challenges is crucial, especially for older adults [37].

The improvements in CAT, SGRQ, EQ-5D, and EQ-5D VAS scores hold clinical significance, particularly when considering their impact on patient outcomes. Taking CAT as an example, the improvement (an average reduction of 1.65 points), although slightly below the minimal clinically important difference (2 points), may indicate mild symptom relief, such as reductions in dyspnea and coughing. This can have practical importance for daily functioning, especially for patients with a higher symptom burden. While these improvements do not directly translate into significant enhancements in overall QoL, they may help reduce the risk of acute exacerbations or slow disease progression, serving as a valuable supplementary tool for personalized management, particularly in resource-limited or remote health care settings.

Notably, while the 12-month QoL data suggest potential long-term benefits, the effect sizes are derived from only 5 studies with varying designs and high heterogeneity (I2 up to 92%). Due to the limitations of the available data, these long-term findings should be interpreted with caution. In addition, we emphasize the need for further high-quality, long-term studies to confirm the robustness and generalizability of these results.

Functional Outcomes

In the second subgroup analysis, digital health interventions showed the greatest impact on dyspnea in patients with COPD at 3 months, likely due to high adaptability and initial learning effects. However, no significant differences were observed at 6 months, suggesting a decline in novelty and short-term adjustable factors reaching their limit. A marginally significant improvement was noted at 12 months, indicating that long-term adherence may gradually alleviate chronic issues. Individual differences, environmental changes, and study design characteristics also contribute to these observations. These findings highlight the dynamic and complex nature of digital health interventions. Future longitudinal studies should include larger, more diverse patient populations and conduct detailed analyses of intervention effects over time to validate these results and explore underlying mechanisms.

Despite significant improvements in dyspnea (mMRC) and QoL (CAT/SGRQ) for patients with COPD through digital health interventions, no such benefits were seen in the 6MWT. This may be due to a mismatch between interventions and functional improvement needs. Most digital tools focused on symptom monitoring (eg, dyspnea diaries) and self-management education (eg, medication reminders), lacking structured exercise prescriptions. Evidence shows that improving 6MWT requires high-intensity aerobic training, which remote monitoring alone cannot provide [38]. Only 1 trial included sensor-guided walking training; others did not prioritize exercise adherence [29]. In addition, the sensitivity of 6MWT is limited by comorbidities and testing conditions, diluting intervention effects. Future research should use accelerometers for more precise functional assessment. Furthermore, declining patient engagement over time, possibly due to “digital health fatigue,” where interest in repetitive tasks wanes, may reduce effectiveness [39]. No improvements in 6MWT or mMRC at 6 months suggest short-term effects diminish with reduced participation.

Self-Efficacy

Subgroup analysis results indicate that at 6 months, digital health interventions significantly enhanced self-efficacy in patients with COPD, but no significant effect was observed at 12 months. This pattern aligns with the social cognitive theory by Bandura [40]: early improvements (at 3 and 6 months) stem from mastery experiences (eg, symptom control via real-time feedback) and clinician-mediated social persuasion. Self-efficacy (GSE) improved significantly in the short term but showed no significant changes at 12 months. The lack of sustained adaptive reinforcement likely contributed to “digital health fatigue,” leading to attrition at 12 months [39]. Patients may have felt they maximized benefits within a 6-month period, experiencing the greatest benefit during this phase. This contrasts with long-duration trials where improvements plateaued. These findings also align with the study by Pierz et al [41], who noted digital health technologies enhance self-efficacy through remote management, improved communication, and personalized support. The improvement in self-efficacy indicates an increased confidence among patients in managing their disease, which may promote behavioral changes, such as better medication adherence and greater participation in physical activity.

Health Care Use Indicators

The reason for the lack of improvement in health care resource use is, first, that the monitoring systems in the 2 included studies lacked closed-loop response mechanisms—personalized plans by Stamenova et al [24] did not integrate automated clinical pathways, while nurse-led monitoring by De San Miguel et al [25] experienced response delays, preventing data from being promptly translated into preventive interventions. Second, there was insufficient patient-side execution efficacy: the complexity of multidevice operation in the former affected adherence among older patients, while the latter relied on self-recording, which was prone to errors. In addition, the interventions were not deeply integrated with regional health care resources (eg, emergency medication delivery and rapid referrals), meaning that even when deterioration was detected, timely treatment could not be ensured. Moreover, the technical design did not align with COPD management needs—the interfaces were complex and lacked threshold alerts for deterioration, resulting in inefficient data use. Fundamentally, the application of technology remained at the data collection level, failing to address systemic bottlenecks, such as the “monitoring-to-action” transition and resource accessibility, which explains why hospitalization rates were not reduced [24,25].

Analysis of High Heterogeneity

SGRQ Scores of QoL

The high heterogeneity in SGRQ scores (I2=91%) is primarily due to the multidimensional nature of the scale (symptoms, activity, and disease impact) conflicting with the varied focus of interventions. For instance, the study by Farmer et al [22] improved symptoms through blood oxygen monitoring but had limited effects on activity, while the study by Zanaboni et al [17] demonstrated greater improvements in activity via exercise training. In addition, differences in control group settings (eg, basic outpatient rehabilitation in China vs passive follow-ups in the United Kingdom) further contributed to result dispersion.

EQ-5D Scores of QoL

The high heterogeneity in EQ-5D scores (I2=92%) likely stems from a mismatch between general health assessments (mobility and self-care) and COPD-specific interventions (lung function and symptom control). The study by Stamenova et al [24] showed that remote monitoring reduced hospitalizations but had minimal impact on daily activities, while the study by Nyberg et al [27] found increased physical activity improved overall health, though comorbidities diluted these effects. Small sample sizes and varying intervention durations (12 vs 24 months) further exacerbated variability.

Overall QoL Assessments

The high heterogeneity in overall QoL assessments (I2=80%) arises from combining different scales (SGRQ, EQ-5D, and CAT), which vary in structure and sensitivity. For example, the CAT may show improvements in symptoms, while EQ-5D indicates no change or even deterioration. In addition, intervention goals often focus on symptom control or reducing exacerbations (eg, “exacerbation-free weeks” by Boer et al [23]) rather than directly enhancing overall QoL.

Self-Efficacy at 12 Months

The high heterogeneity in self-efficacy at 12 months (I2=91%) observed in the study by Wang et al [21] and the study by Zanaboni et al 2023 [17] primarily stems from key differences in their intervention approaches. The study by Wang et al [21] used a mobile app focusing on education and social support but lacked structured behavioral training, whereas the study by Zanaboni et al 2023 [17] implemented home-based telerehabilitation, incorporating exercise training and real-time monitoring. Differences in assessment timing, adherence strategies, and cultural contexts also contributed to outcome variability, leading to significant heterogeneity in pooled analysis.

6MWT at 3 Months

The high heterogeneity in the 6MWT at 3 months (I2=94%) is primarily due to fundamental differences in interventions and population adaptability across studies. The study by Robinson et al [34] relied on fully self-guided web-based exercise with community feedback; the study by Tabak et al [29] integrated real-time monitoring with remote counseling; and the study by Wan et al [33] focused on a pedometer combined with an educational website. Furthermore, significant variations in participant age, baseline disease severity, and intervention support intensity collectively led to highly dispersed improvements in walking capacity.

Relationship With Previous Published Literature

Previous systematic reviews have evaluated the effectiveness of digital health interventions in various areas such as blood pressure control in nondialysis chronic kidney disease [42], prevention of cardiovascular disease [43], hypertension management [44], and weight management in children and adolescents [45]. Many of these reviews concluded that digital health interventions are effective tools that lead to positive outcomes. To our knowledge, 5 other systematic reviews have been published on this topic specifically for patients with COPD [13,46-49]. One of these reviews was limited to the effects of digital health interventions for pulmonary rehabilitation in people with COPD [46], another focused on the role of digital health interventions for the self-management of COPD [47], and the other review focused on the cost-effectiveness of digital health interventions for asthma or COPD [48]. In addition, although 2 recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses aimed to assess the effects of home remote monitoring with mobile apps in patients with COPD [13,49], they included interventions module focusing solely remote monitoring rather than other module (eg, health education, behavioral incentive, and social support), and the technologies do not involve electronic health records, wearable technology, and data analysis platforms. Therefore, this systematic review is unique because it extends beyond previous reviews by including evidence from newly published studies that provide more comprehensive health management services.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, there may be language biases as the searches were conducted in English, which could restrict the cross-cultural applicability of our findings. Second, our exclusive focus on RCTs—while methodologically rigorous—excluded potentially relevant nonrandomized studies (eg, pragmatic trials) that could provide complementary insights into real-world implementation of digital health tools. Third, the Scopus database was not retrieved, and it should be included in the future. So, we searched PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, and Web of Science databases. Keyword searches in PubMed provide optimal update frequency and include early web-based articles; other databases rank articles by the number of citations as an indicator of importance. In addition, due to the small number of studies, subgroup analyses were not conducted, and publication bias was not explored. Finally, variations in the number of participants, intervention duration, frequency, research tool, and follow-up times led to heterogeneity.

Practical Implications for Health Care and Further Studies

Digital health interventions show potential as a valuable addition to standard clinical care for COPD. Nevertheless, the adoption of digital health tools in this population is still in its early stages. Further research is essential to evaluate the impact of such interventions. Moreover, it is crucial to determine whether the currently limited effectiveness remains consistent and to explore the conditions under which their benefits could be maximized. These are areas that warrant systematic investigation. In addition, with the growing aging population, future studies should focus on older adults with COPD, who represent the largest group of potential users. Older adults need access to digital health tools to support them to live independently and the self-care of chronic diseases. Computer or smartphone ownership among individuals aged ≥65 years has risen significantly [50]. However, according to the European Union Commission’s 2012 to 2020 eHealth Action Plan, the current mHealth environment lacks intuitive tools and services tailored for older patients [50]. Therefore, gaining insights into the needs of older adults with COPD is critical for designing, developing, and assessing digital health tools interventions for this demographic.

Conclusions

Our analysis revealed that digital health interventions may have the potential to improve QoL at 3, 6, and 12 months. In addition, the degree of dyspnea significantly decreased at 3 months and approached significance at 12 months. Self-efficacy also improved significantly in the short term, particularly at 3 and 6 months. However, no significant differences were observed in the 6MWT, emergency department admissions, hospital admissions, emergency department admissions for COPD, or hospital admissions for COPD. Furthermore, there is insufficient generalizable evidence to confidently advocate for replacing conventional management strategies with digital health interventions for COPD. This limitation arises due to clinical and methodological variability across studies, small sample sizes, and inconsistencies in platforms functionalities, content, duration, and follow-up protocols. Considering the global surge in digital health tools use and the increasing adoption of eHealth solutions, additional research using robust study designs, long-term follow-ups, and samples representative of older adults is essential to evaluate the long-term sustainability of digital health–based interventions.

Acknowledgments

They would like to thank Scribendi for their professional proofreading of this paper.

This work is supported by a special fund for the 12th batch of teaching reform research project of Xi’an Jiaotong University City College in 2024 (XJJG2413) and a Science and Technology Department of Shaanxi Province (2022SF-174).

Abbreviations

- 6MWT

6-minute walk test

- AI

artificial intelligence

- CAT

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Assessment Test

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- GSE

General Self-Efficacy

- HCP

health care professional

- MD

mean difference

- MeSH

Medical Subject Headings

- mMRC

Modified Medical Research Council

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- QoL

quality of life

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SGRQ

St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire

- SMD

standardized mean difference

- VAS

visual analogue scale

PRISMA 2020 checklist.

Search strategies.

Data Availability

The datasets used and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: MZ conducted the literature search and drafted the initial manuscript. YG and JQ organized data extraction and literature search. JY performed the data analysis. WMAWA and IIH revised the manuscript, contributed to the study conception, and supervised the research. All authors researched data for the paper, made substantial contributions to discussions of the content, and reviewed or edited the manuscript before submission. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.GBD 2016 Occupational Chronic Respiratory Risk Factors Collaborators Global and regional burden of chronic respiratory disease in 2016 arising from non-infectious airborne occupational exposures: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Occup Environ Med. 2020 Mar;77(3):142–150. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2019-106013. http://oem.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=32054818 .oemed-2019-106013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prasad B. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Int J Pharm Res Technol. 2020;10(1):67–71. doi: 10.31838/ijprt/10.01.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhong N, Wang C, Yao W, Chen P, Kang J, Huang S, Chen B, Wang C, Ni D, Zhou Y, Liu S, Wang X, Wang D, Lu J, Zheng J, Ran P. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a large, population-based survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 Oct 15;176(8):753–60. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200612-1749OC.200612-1749OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou M, Wang H, Zeng X, Yin P, Zhu J, Chen W, Li X, Wang L, Wang L, Liu Y, Liu J, Zhang M, Qi J, Yu S, Afshin A, Gakidou E, Glenn S, Krish VS, Miller-Petrie MK, Mountjoy-Venning WC, Mullany EC, Redford SB, Liu H, Naghavi M, Hay SI, Wang L, Murray CJ, Liang X. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2019 Sep 28;394(10204):1145–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30427-1. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140-6736(19)30427-1 .S0140-6736(19)30427-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guarascio AJ, Ray SM, Finch CK, Self TH. The clinical and economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the USA. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:235–45. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S34321. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2147/CEOR.S34321?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub0pubmed .ceor-5-235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teo WS, Tan WS, Chong WF, Abisheganaden J, Lew YJ, Lim TK, Heng BH. Economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respirology. 2012 Jan 21;17(1):120–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turakhia MP, Desai SA, Harrington RA. The outlook of digital health for cardiovascular medicine: challenges but also extraordinary opportunities. JAMA Cardiol. 2016 Oct 01;1(7):743–4. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.2661.2546893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Velardo C, Shah SA, Gibson O, Clifford G, Heneghan C, Rutter H, Farmer A, Tarassenko L, EDGE COPD Team Digital health system for personalised COPD long-term management. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2017 Feb 20;17(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s12911-017-0414-8. https://bmcmedinformdecismak.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12911-017-0414-8 .10.1186/s12911-017-0414-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Connor L, Behar S, Tarrant S, Stamegna P, Pretz C, Wang B, Savage B, Scornavacca T, Shirshac J, Wilkie T, Hyder M, Zai A, Toomey S, Mullen M, Fisher K, Tigas E, Wong S, McManus DD, Alper E, Lindenauer PK, Dickson E, Broach JP, Kheterpal V, Soni A. Healthy at home for COPD: an integrated digital monitoring, treatment, and pulmonary rehabilitation intervention. BMC Digit Health. 2025 Jan 14;3(1):s44247. doi: 10.1186/S44247-024-00142-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, Li G, Ezeana CF, Ogunti R, Puppala M, He T, Yu X, Wong SS, Yin Z, Roberts AW, Nezamabadi A, Xu P, Frost A, Jackson RE, Wong ST. An AI-driven clinical care pathway to reduce 30-day readmission for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients. Sci Rep. 2022 Nov 30;12(1):20633. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-22434-3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22434-3 .10.1038/s41598-022-22434-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruz J, Brooks D, Marques A. Home telemonitoring effectiveness in COPD: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2014 Mar 28;68(3):369–78. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang F, Wang Y, Yang C, Hu H, Xiong Z. Mobile health applications in self-management of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of their efficacy. BMC Pulm Med. 2018 Sep 04;18(1):147. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0671-z. https://bmcpulmmed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12890-018-0671-z .10.1186/s12890-018-0671-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jang S, Kim Y, Cho WK. A systematic review and meta-analysis of telemonitoring interventions on severe COPD exacerbations. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jun 23;18(13):6757. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18136757. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph18136757 .ijerph18136757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han X, Zhou X, Tan B, Jiao L, Zhang R. AI-based next-generation sensors for enhanced rehabilitation monitoring and analysis. Measurement. 2023 Dec;223:113758. doi: 10.1016/j.measurement.2023.113758. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0263224123013222 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chouvarda IG, Goulis DG, Lambrinoudaki I, Maglaveras N. Connected health and integrated care: toward new models for chronic disease management. Maturitas. 2015 Sep;82(1):22–7. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.03.015.S0378-5122(15)00605-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knobloch K, Yoon U, Vogt PM. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement and publication bias. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2011 Mar;39(2):91–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2010.11.001.S1010-5182(10)00218-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zanaboni P, Dinesen B, Hoaas H, Wootton R, Burge AT, Philp R, Oliveira CC, Bondarenko J, Tranborg Jensen T, Miller BR, Holland AE. Long-term telerehabilitation or unsupervised training at home for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023 Apr 01;207(7):865–875. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202204-0643OC. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/36480957 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA, Cochrane Bias Methods Group. Cochrane Statistical Methods Group The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011 Oct 18;343(oct18 2):d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. https://boris.unibe.ch/id/eprint/7356 .bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang Y, Liu F, Guo J, Sun P, Chen Z, Li J, Cai L, Zhao H, Gao P, Ding Z, Wu X. Evaluating an intervention program using WeChat for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Apr 21;22(4):e17089. doi: 10.2196/17089. https://www.jmir.org/2020/4/e17089/ v22i4e17089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park SK, Bang CH, Lee SH. Evaluating the effect of a smartphone app-based self-management program for people with COPD: a randomized controlled trial. Appl Nurs Res. 2020 Apr;52:151231. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2020.151231.S0897-1897(19)30284-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L, Guo Y, Wang M, Zhao Y. A mobile health application to support self-management in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2021 Jan 09;35(1):90–101. doi: 10.1177/0269215520946931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farmer A, Williams V, Velardo C, Shah SA, Yu LM, Rutter H, Jones L, Williams N, Heneghan C, Price J, Hardinge M, Tarassenko L. Self-management support using a digital health system compared with usual care for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2017 May 03;19(5):e144. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7116. https://www.jmir.org/2017/5/e144/ v19i5e144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boer L, Bischoff E, van der Heijden M, Lucas P, Akkermans R, Vercoulen J, Heijdra Y, Assendelft W, Schermer T. A smart mobile health tool versus a paper action plan to support self-management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019 Oct 09;7(10):e14408. doi: 10.2196/14408. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2019/10/e14408/ v7i10e14408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stamenova V, Liang K, Yang R, Engel K, van Lieshout F, Lalingo E, Cheung A, Erwood A, Radina M, Greenwald A, Agarwal P, Sidhu A, Bhatia RS, Shaw J, Shafai R, Bhattacharyya O. Technology-enabled self-management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with or without asynchronous remote monitoring: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Jul 30;22(7):e18598. doi: 10.2196/18598. https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e18598/ v22i7e18598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De San Miguel K, Smith J, Lewin G. Telehealth remote monitoring for community-dwelling older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Telemed J E Health. 2013 Sep;19(9):652–7. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2012.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenealy TW, Parsons MJ, Rouse AP, Doughty RN, Sheridan NF, Hindmarsh JK, Masson SC, Rea HH. Telecare for diabetes, CHF or COPD: effect on quality of life, hospital use and costs. A randomised controlled trial and qualitative evaluation. PLoS One. 2015 Mar 13;10(3):e0116188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116188. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0116188 .PONE-D-14-16859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nyberg A, Tistad M, Wadell K. Can the COPD web be used to promote self-management in patients with COPD in swedish primary care: a controlled pragmatic pilot trial with 3 month- and 12 month follow-up. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2019 Mar 31;37(1):69–82. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2019.1569415. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02813432.2019.1569415?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub0pubmed . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benzo R, Hoult J, McEvoy C, Clark M, Benzo M, Johnson M, Novotny P. Promoting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease wellness through remote monitoring and health coaching: a clinical trial. Annals ATS. 2022 Nov;19(11):1808–17. doi: 10.1513/annalsats.202203-214oc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tabak M, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk P, Hermens H, Vollenbroek-Hutten M. A telehealth program for self-management of COPD exacerbations and promotion of an active lifestyle: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:935–44. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S60179. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2147/COPD.S60179?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub0pubmed .copd-9-935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ali L, Wallström S, Fors A, Barenfeld E, Fredholm E, Fu M, Goudarzi M, Gyllensten H, Lindström Kjellberg I, Swedberg K, Vanfleteren LE, Ekman I. Effects of person-centered care using a digital platform and structured telephone support for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic heart failure: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2021 Dec 13;23(12):e26794. doi: 10.2196/26794. https://www.jmir.org/2021/12/e26794/ v23i12e26794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moy ML, Collins RJ, Martinez CH, Kadri R, Roman P, Holleman RG, Kim HM, Nguyen HQ, Cohen MD, Goodrich DE, Giardino ND, Richardson CR. An internet-mediated pedometer-based program improves health-related quality-of-life domains and daily step counts in COPD: a randomized controlled trial. Chest. 2015 Jul;148(1):128–37. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1466. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25811395 .S0012-3692(15)50028-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen HQ, Gill DP, Wolpin S, Steele BG, Benditt JO. Pilot study of a cell phone-based exercise persistence intervention post-rehabilitation for COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009 Aug;4:301–13. doi: 10.2147/copd.s6643. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2147/copd.s6643?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub0pubmed . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wan ES, Kantorowski A, Homsy D, Teylan M, Kadri R, Richardson CR, Gagnon DR, Garshick E, Moy ML. Promoting physical activity in COPD: insights from a randomized trial of a web-based intervention and pedometer use. Respir Med. 2017 Sep;130:102–10. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.07.057. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0954-6111(17)30256-1 .S0954-6111(17)30256-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson SA, Cooper Jr JA, Goldstein RL, Polak M, Cruz Rivera PN, Gagnon DR, Samuelson A, Moore S, Kadri R, Richardson CR, Moy ML. A randomised trial of a web-based physical activity self-management intervention in COPD. ERJ Open Res. 2021 Jul 15;7(3):00158-2021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00158-2021. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34476247 .00158-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isernia S, Pagliari C, Bianchi LN, Banfi PI, Rossetto F, Borgnis F, Tavanelli M, Brambilla L, Baglio F, CPTM Group Characteristics, components, and efficacy of telerehabilitation approaches for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Nov 17;19(22):15165. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192215165. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph192215165 .ijerph192215165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marangunić N, Granić A. Technology acceptance model: a literature review from 1986 to 2013. Univ Access Inf Soc. 2014 Feb 16;14(1):81–95. doi: 10.1007/S10209-014-0348-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aburub A, Darabseh MZ, Badran R, Eilayyan O, Shurrab AA, Degens H. The effects of digital health interventions for pulmonary rehabilitation in people with COPD: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024 Jun 11;60(6):963. doi: 10.3390/medicina60060963. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=medicina60060963 .medicina60060963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor JL, Holland DJ, Spathis JG, Beetham KS, Wisløff U, Keating SE, Coombes JS. Guidelines for the delivery and monitoring of high intensity interval training in clinical populations. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2019 Mar;62(2):140–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2019.01.004.S0033-0620(19)30031-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sada YH, Poursina O, Zhou H, Workeneh BT, Maddali SV, Najafi B. Harnessing digital health to objectively assess cancer-related fatigue: the impact of fatigue on mobility performance. PLoS One. 2021 Feb 26;16(2):e0246101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246101. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246101 .PONE-D-20-01496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Devi B, Khandelwal B, Das M. Application of Bandura's social cognitive theory in the technology enhanced, blended learning environment. Int J Appl Res. 2017;3(1):721–4. https://www.allresearchjournal.com/archives/?year=2017&vol=3&issue=1&part=J&ArticleId=3115 . [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pierz KA, Locantore N, McCreary G, Calvey RJ, Hackney N, Doshi P, Linnell J, Sundaramoorthy A, Reed CR, Yates J. Investigation of the impact of wellinks on the quality of life and clinical outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: interventional research study. JMIR Form Res. 2024 Feb 09;8:e47555. doi: 10.2196/47555. https://formative.jmir.org/2024//e47555/ v8i1e47555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muneer S, Okpechi IG, Ye F, Zaidi D, Tinwala MM, Hamonic LN, Ghimire A, Sultana N, Slabu D, Khan M, Braam B, Jindal K, Klarenbach S, Padwal R, Ringrose J, Scott-Douglas N, Shojai S, Thompson S, Bello AK. Impact of home telemonitoring and management support on blood pressure control in Nondialysis CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2022 Jun 21;9:20543581221106248. doi: 10.1177/20543581221106248. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/20543581221106248?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub0pubmed .10.1177_20543581221106248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Widmer RJ, Collins NM, Collins CS, West CP, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Digital health interventions for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015 Apr;90(4):469–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.12.026. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25841251 .S0025-6196(15)00073-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katz ME, Mszar R, Grimshaw AA, Gunderson CG, Onuma OK, Lu Y, Spatz ES. Digital health interventions for hypertension management in US populations experiencing health disparities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Feb 05;7(2):e2356070. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.56070. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/38353950 .2815070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kouvari M, Karipidou M, Tsiampalis T, Mamalaki E, Poulimeneas D, Bathrellou E, Panagiotakos D, Yannakoulia M. Digital health interventions for weight management in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2022 Feb 14;24(2):e30675. doi: 10.2196/30675. https://www.jmir.org/2022/2/e30675/ v24i2e30675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matthew-Maich N, Harris L, Ploeg J, Markle-Reid M, Valaitis R, Ibrahim S, Gafni A, Isaacs S. Designing, implementing, and evaluating mobile health technologies for managing chronic conditions in older adults: a scoping review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016 Jun 09;4(2):e29. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.5127. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2016/2/e29/ v4i2e29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verma A, Behera A, Kumar R, Gudi N, Joshi A, Islam KM. Mapping of digital health interventions for the self-management of COPD: a systematic review. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2023 Nov;24:101427. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2023.101427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferreira MA, Dos Santos AF, Sousa-Pinto B, Taborda-Barata L. Cost-effectiveness of digital health interventions for asthma or COPD: systematic review. Clin Exp Allergy. 2024 Sep 12;54(9):651–68. doi: 10.1111/cea.14547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nagase FI, Stafinski T, Avdagovska M, Stickland MK, Etruw EM, Menon D. Effectiveness of remote home monitoring for patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022 May 14;22(1):646. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-07938-y. https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-022-07938-y .10.1186/s12913-022-07938-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wildenbos GA, Jaspers MW, Schijven MP, Dusseljee-Peute LW. Mobile health for older adult patients: using an aging barriers framework to classify usability problems. Int J Med Inform. 2019 Apr;124:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.01.006.S1386-5056(18)30500-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA 2020 checklist.

Search strategies.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.