Abstract

Proteins are constantly damaged by intracellular and extracellular factors, particularly under stress conditions, leading to an accumulation of modified proteins such as isoaspartate (isoD), which is linked to aging and various diseases. The repair enzyme PCMT1 (protein-l-isoaspartate o-methyltransferase) specifically restores isoD residues to aspartate, preventing abnormal protein functions. Despite its importance, its role in non-neural tissues remains underexplored. This study employed isoD-proteomics, global proteomics, and transcriptomics on Pcmt1 knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice, revealing significant gene and protein changes in various KO tissues, enriched in extracellular and membrane-related categories, highlighting genome-proteome correlations. IsoD-carrying proteins were increased in KO tissues, predominantly consisting of long-lived proteins. Additionally, the proteomic analysis of PCMT1-overexpressing cells identified interacting proteins mainly in extracellular and membrane-related categories. These findings revealed both tissue-specific and shared roles of PCMT1, emphasizing its importance in maintaining protein integrity under physiological and stress conditions while also uncovering an unexpected extracellular function of PCMT1.

Keywords: PCMT1, multiomics, isoaspartate, extracellular, stress condition

Introduction

Proteins are continuously subjected to damage by various intracellular and extracellular factors, particularly under aging or stress conditions. The persistent accumulation of ‘damaged proteins’ increases susceptibility to chronic diseases. At the molecular level, these damaged proteins undergo various detrimental modifications, including oxidation, glycation, deamidation, and other nonenzymatic changes. − Notably, the deamidation of asparagine or the isomerization of aspartic acid, leading to the accumulation of isoaspartate (isoD), has been closely associated with various diseases. − While early studies suggested that isoaspartate modifications occur nonspecifically, primarily compromising protein structural integrity and biological activity, , emerging evidence indicates that such modifications may also confer abnormal function on proteins, actively contributing to disease progression. − The presence of isoD significantly increases the diversity of molecular states within the organism, potentially enhancing molecular interactions and affecting critical pathways and key molecules. ,− Cells employ multiple mechanisms to remove damaged proteins, including lysosome- and proteasome-dependent degradation pathways. Additionally, intracellular protein repair mechanisms, independent of de novo synthesis, play a vital role in restoring protein function.

PCMT1 (Protein-l-isoaspartate o-methyltransferase) is a specific repair enzyme that targets protein damage caused by isoaspartate (isoD) formation. This enzyme is widely expressed across various organisms, including bacteria, plants, Drosophila, and mammals. In mammals, PCMT1 expression can be detected in multiple tissues. A recent study reported that, in patients with alcoholic liver disease, serum PCMT1 levels decreased across disease stages compared to healthy controls, although its underlying mechanism remains unclear. Its primary function is to mediate protein repair by converting abnormal isoaspartate residues back to aspartate, thereby restoring protein functionality. Studies have shown that systemic knockout of PCMT1 in mice leads to a significant accumulation of isoaspartate in tissues, resulting in severe outcomes such as fatal seizures and premature death. Using mass spectrometry, researchers have identified abnormal isoD accumulation in brain proteins, highlighting several key PCMT1 substrates. These include synapsin 1, Tau, and amyloid beta (Aβ) protein, which are strongly associated with neural signal transduction and Alzheimer’s disease. Additionally, the loss of PCMT1 has been linked to the abnormal activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, as reported in several studies. , However, due to the early mortality caused by brain-related conditions in PCMT1-deficient models, its functions in other organs remain largely unexplored.

In this study, we performed multiomics analyses of global PCMT1 knockout mice and wild-type controls. We examined isoD-modified proteins, total protein levels, and transcriptome profiles across various organs and identified PCMT1-interacting proteins. This comprehensive approach allowed us to investigate the accumulation of isoD-modified proteins in different tissues and explore the potential functional consequences of this accumulation. Our findings provide valuable insights into the physiological roles of PCMT1 and its impact on protein homeostasis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Pcmt1 +/– mice were provided by Jiangsu Gempharmatech Co., Ltd. The primer sets for Pcmt1 intron 1 were as follows: Pcmt1-F1: TTGAACTCCTGACCTTCGGAAG, and Pcmt1-R1: TCTCCATCCATACAGATGGACTGC. All mice were maintained under a 12-h light–dark cycle and were given food and water ad libitum. Genomic identification was performed on genomic DNA extracted from tails using the Direct Mouse Genotyping Kit (Vazyme, PD101-01). All procedures were performed in accordance with guidelines and approved protocols by the Animal Care and Use Committees at Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (SYXK(Hu)2018–0027).

Cell Line and Culture Conditions

Human ovarian cancer SKOV3 cells expressing PCMT-HA or Luc-HA (control) were cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium (Basal media, L630 KJ) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. To simulate the heat shock condition, cells were heated in a cell culture chamber (40 °C, 5% CO2) for 3 h, followed by incubation at 37 °C in a regular cell culture incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2) for 12 h. To simulate the hypoxic condition, cells were cultured in a hypoxic cell culture chamber (37 °C, 1% O2) for 48 h.

RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from cell cultures using the EZ-press RNA Purification kit (B0004DP) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and purity were measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (TIANGE) at 260 and 280 nm absorbance. Reverse transcription of RNA to cDNA was carried out using the HiScript III All-in-one RT SuperMix Perfect for qPCR Kit (Vazyme, R333) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Q711) was used to detect the mRNA levels of target genes. The following primers were used: HSP70-F: TTTTACCACTGAGCAAGTGACTG, HSP70-R: ACAAGGAACCGAAACAACACA; VEGFA-F: AGGGCAGAATCATCACGAAGT, VEGFA-R: AGGGTCTCGATTGGATGGCA; GAPDH-F: ACAACTTTGGTATCGTGGAAGG, and GAPDH-R: GCCATCACGCCACAGTTTC. Relative quantification of the mRNA levels was performed using the comparative Ct method with GAPDH as the reference gene and the formula 2–ΔΔCt.

RNA-Seq

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent. The library construction and sequencing were performed at Shanghai Sinomics Corporation, as previously described. Briefly, the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina) was used to synthesize paired-end libraries according to manufacturer’s instructions. A Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies) was used to quantify RNA amounts in the libraries. Clusters were generated by cBot and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina). FastQC was used to assess the quality of Fastq files and trim them to clean the reads. The reads were then mapped to GRCm38.102 (mouse samples) using the Hisat2 tool. Mapped reads were converted to FPKM values to comprehensively characterize gene expression. The obtained FPKM values were used for horizontal comparisons between different samples and groups using edgeR.

Protein Purification

Purification of PCMT1 was performed as previously described. The human PCMT1 coding sequence was inserted into the pSmart-His-Sumo expression vector and introduced into Escherichia coli BL21 chemically competent cells via heat-shock transformation. Recombinant PCMT1 production was initiated by induction with 0.2 mM IPTG at 18 °C overnight. Post-induction, cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer. Cell disruption was performed using high-pressure homogenization at 900 MPa, followed by clarification via centrifugation. The supernatant was subjected to immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) using a HisTrap HP column (Cytiva). Bound proteins were eluted with a linear imidazole gradient (25–500 mM) in elution buffer. Eluate fractions were screened by SDS-PAGE with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 staining, and PCMT1-containing fractions were pooled. The His-SUMO fusion tag was enzymatically cleaved by incubation with the ULP1 protease. The reaction mixture was dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, then reapplied to the HisTrap HP column to separate the cleaved tag. Tag-free PCMT1 in the flowthrough was concentrated using a 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff centrifugal filter and further purified by size-exclusion chromatography equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 50 mM NaCl to eliminate low-molecular-weight contaminants. Final protein purity was verified by SDS-PAGE analysis. Purified PCMT1 aliquots were flash-frozen at −80 °C for downstream applications.

Tris-Labeled MS

Tissue samples were lysed using RIPA buffer (100 μL of RIPA was added to 10 mg of tissue) and supplemented with a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 4906837001), 1 mM PMSF (Sangon Biotech), and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 11836170001). Tissues treated with RIPA were homogenized and centrifuged to extract the protein. Protein samples were quantified using the BCA assay (Thermo, 23227). The centrifuged protein supernatants were reduced with 1 M DTT (Dithiothreitol, Roche, 10197777001) and alkylated with IAM (Iodoacetamide, Sigma, I6125). Methanol–chloroform sedimentation was then performed using 100 μg of protein per sample, followed by resuspension in 100 μL of 100 mM TEAB (pH 7.5). Trypsin/Lys-C Mix (Promega, V5072) was added at an enzyme-to-protein weight ratio of 1:50, and digestion was carried out at 37 °C overnight. The tryptic peptides were combined at a concentration of 40 μM for each sample and reacted with PCMT1 at a molar ratio of 1:50 PCMT1/peptide, along with 400 μM SAM and 1.0 M Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), at 37 °C for 24 h. The method was performed as previously reported. All samples were quenched with TFA to achieve a pH < 4, stopping further reactions. Peptides were then treated with 1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), purified using C18 ZipTips, and eluted with 0.1% TFA in 50–70% acetonitrile. Desalted peptides were preprocessed and injected into an orbitrap fusion lumos mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) coupled with an EASY-nLC 1000 liquid chromatograph instrument (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Peptides were separated using the same gradient as previously reported. Bioinformatics and statistical analysis of the original mass spectrometric data were performed using PEAKS Studio version 8.5 with the SwissProt database (updated March 2024). Oxidation (M), acetylation (N-term), carbamidomethylation, deamidation (NQ), and iso-asp-tris (103.06 Da) were set as variable modifications to identify D-to-isoD sites. Additionally, deamidation-iso-asp (104.05 Da) was added to the variable modifications to search for N-to-isoD sites. Only hits with FDR ≤ 0.01 and p-value < 0.05 were accepted for discussion.

Proteomics

TMT (tandem mass tag)-labeled LC-MS (liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry) was used to detect the different proteins between Pcmt1 +/+ and Pcmt1 –/– mice. Briefly, tissue samples were processed using the same method for peptides as described in isoD identification. The peptides were then labeled with TMT126–TMT131 (Thermo, 90061), and the reaction was quenched with 5% hydroxylamine. Equal amounts of labeled samples were mixed together, fractionated, and desalted using the Pierce High pH Reversed-Phase Peptide Fractionation Kit (Thermo, 84868). Finally, peptides were preprocessed and injected into an orbitrap fusion lumos mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) coupled with an EASY-nLC 1000 liquid chromatography instrument (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Statistical analysis of the original data was performed using Peaks Studio based on the UniProt database (updated March 2024). Only hits with FDR ≤ 0.01 and p-value < 0.05 were accepted for discussion.

Co-Immunoprecipitation-MS

Co-IP was performed as previously described. For HA-tagged protein and the interacting protein, PCMT1-HA and luciferase-HA (Luc-HA) stable cells (HK-2, SKOV3, and 293T cells) were harvested and incubated with 50 mM dimethyl dithiobispropionimidate (DTBP, Thermo, 20665) for 10 min at 25 °C. To quench the reaction after DTBP incubation, 125 mM glycine was added. The cells were then lysed using MCLB (mammalian cell lysis buffer: 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40) and centrifuged to extract proteins. One milligram of protein was subjected to Co-IP using 10 μL of prewashed anti-HA magnetic beads overnight at 4 °C with gentle rolling. The bound proteins were washed five times using MCLB and PBS and then eluted with a 0.1 M glycine solution, pH 2.0. Heat shock and hypoxia samples were eluted with HA-tag peptide. Eluted samples were preprocessed and injected into an LTQ-orbitrap fusion mass spectrometer, coupled with an EASY-nLC 1000 Liquid Chromatograph Instrument (Thermo Scientific). Statistical analysis of the original data was performed using Peaks Studio based on the UniProt database (20180524, 20349).

Results

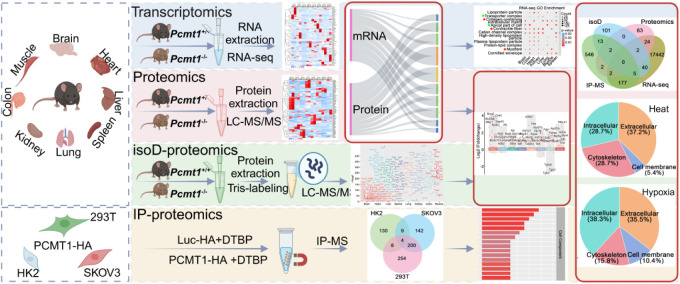

To elucidate the molecular pathways regulated by PCMT1, we utilized an integrative multiomics approach. Using Pcmt1 wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) mice, we identified genes, proteins, and pathways altered by Pcmt1 deficiency across multiple key tissues and organs. Enrichment analyses of individual datasets, as well as combined datasets (isoD-proteomics, proteomics, and transcriptomics), highlighted critical pathways, providing a comprehensive biological context for this enzyme. Furthermore, we mapped the interactome of PCMT1 in multiple cell lines to identify its potential substrates. Through these unbiased analyses, we aim to reveal the biological function of PCMT1 under physiological conditions (Figure ).

1.

Workflow of multiomics analysis on different tissues of Pcmt1 +/+ and Pcmt1 –/– mice.

Tissues from Pcmt1 +/+ and Pcmt1 –/– mice were subjected to transcriptomics, proteomics, and isoD-proteomics. Additionally, PCMT1-HA-overexpressing cells were utilized for immunoprecipitation-based interactomics. GO enrichment analysis of cellular component terms from transcriptomics and proteomics was integrated to perform comprehensive analyses.

IsoD-Carrying Proteins Were Identified

l-Isoaspartyl can be generated through the spontaneous deamidation of l-asparaginyl and the dehydration of l-aspartyl. PCMT1 then recognizes the l-isoaspartyl using S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM). This enzymatic process produces S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine (SAH) and a methyl ester intermediate. Under physiological conditions, the methyl ester hydrolyzes spontaneously, generating a succinimide ring structure. It has been reported that Tris can react with the succinimide ring during the deamidation of IgG peptides. This suggests that the succinimide ring appears to be amine-reactive. Therefore, the methyl ester intermediate formed during the PCMT1 repair process is most likely labeled by Tris with an additional mass of 103.06 Da. This provides a simple method to separate Asp and isoAsp.

Detecting protein isomerization sites is essential for understanding PCMT1’s role in biological processes. To globally map isoD sites in Pcmt1 +/+ and Pcmt1 –/– knockout mice, we applied a straightforward tag-labeling technique using PCMT1 and Tris, providing an effective method for site identification. This method was used across various tissues, including the brain, liver, heart, kidney, lung, colon, spleen, and muscle. The analysis revealed that potential PCMT1 substrates were generated not only through dehydration of l-aspartyl (Figure A) but also through deamidation of l-asparaginyl (Figure B) were widely distributed throughout different tissues. A higher accumulation of isoD-carrying proteins was observed in KO mice, with the kidney showing the most pronounced accumulation. Approximately 6% of the identified candidates were present in more than four tissues, including ACTA (Acta2), ACTC (Actc1), ACTB (Actb), ACTG (Actg1), EF1A1 (Eef1a1), RS14 (Rps14), HBB1 (Hbb-b1), and ALBU (Alb). In contrast, about 79.7% of the candidates were identified in only one tissue, such as VDAC1 (Vdac1), UBP14 (Usp14), and DYST (Dst). These findings suggest that the potential substrates of PCMT1 are randomly distributed across various tissues.

2.

Identification of proteins with isoAsp in various tissues of Pcmt1 +/+ and Pcmt1 –/– mice. (A) Proteins with D-to-isoD sites were identified through isoD-proteomics. (B) Proteins with N-to-isoD sites were also identified in different tissues. Proteins from different tissues were represented by different colors. The −10logP indicates the reliability of isoD-protein identification. The potential PCMT1 substrates were distributed across various tissues without tissue specificity. (C) The peptide sequences of D-isoD-containing proteins are shown with position information. The isoD site is located at the center of the peptides and is marked at position 0. Amino acids closer to the N-terminus were less frequent. Acidic amino acids, Asp and Glu, were predominantly distributed in positions −10 and −1, particularly at positions −10 to −8. Leu was more prevalent from positions −7 to 10. The top four amino acids surrounding the isoD sites are Asp, Glu, Leu, and Ser. (D) The peptide sequences of N-isoD-containing proteins are shown with position information. (E) Cellular localization of D-isoD-containing proteins. The location data were categorized into four main groups: the cell membrane (27.8%), the cytoskeleton (9.3%), the extracellular (3.4%), and the intracellular (59.5%). ((F) Cellular localization of N-isoD-containing proteins. There was a higher prevalence of N-to-isoD modifications in intracellular proteins (69.6%). (G) Overlap between D-isoD- and N-isoD-containing proteins.

IsoD-proteomics not only identified isoD-carrying proteins but also provided amino acid sequence information surrounding the isoD sites. The modified aspartic acid (+103.06 Da) was identified as the D-to-isoD site. Peptides containing the D-to-isoD site were then matched to the SwissProt database (updated March 2024) using sequences obtained by LC-MS/MS. When a match was found, the isoD site was labeled as position 0, and the 10 amino acids before and after it were extracted. Interestingly, amino acids near the N-terminus were less frequent, while those near the C-terminus were more abundant (Figure C). Acidic amino acids Asp and Glu were predominantly distributed between positions −10 to −1, especially from positions −10 to −8. Leu was more commonly found between positions −7 to 10. The four most common amino acids identified were Asp, Glu, Leu, and Ser. These findings suggest that protein isomerization more likely occurs when these amino acids (Asp, Glu, Leu, and Ser) are present near the D site, highlighting their potential role in influencing isomerization susceptibility.

The modified aspartic acid (+104.05 Da) was identified as the N-to-isoD site. Additionally, we confirmed that the modified aspartic acid (+104.05 Da) was detected at the same isoD sites as aspartic acid (+103.06 Da), supporting the identification strategy. To further investigate sequence patterns around N-to-isoD sites, we applied the same analytical approach used for D-to-isoD modifications. However, we found no clear sequence similarity or motif enrichment surrounding N-to-isoD sites (Figure D).

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the characteristics of isoD-carrying proteins, we performed a functional enrichment analysis using Gene Ontology. Proteins were classified into three categories: Molecular Function (MF), Biological Process (BP), and Cellular Component (CC). In the CC and MF domains, cytoskeleton-related terms, labeled with red stars, were enriched across various tissues. Notable examples include the myelin sheath in the brain, the dynactin complex and cytoplasmic dynein complex in the heart, the apical junction complex in the kidney, and the myosin complex in muscle. Furthermore, terms related to actin filaments and microtubules were clustered in the liver, spleen, lung, and colon. Membrane-related components, such as the membrane raft in the brain and lung, postsynaptic specialization in the brain, presynapse in the colon, cell leading edge in the liver, and the apical and basal parts of the cell in the kidney, were enriched alongside cytoskeleton-related terms (Figure S1). These results suggest that the absence of PCMT1 induces alterations in the activity of the cytoskeletal and membrane components within cells.

To investigate the specific cellular localization of PCMT1 enzymatic activity, we retrieved the localization data of D to isoD proteins from the reviewed SwissProt database on UniProt. The localization information was classified into four main categories: the cell membrane (27.8%), cytoskeleton (9.3%), extracellular (3.4%), and intracellular (59.5%) (Figure E). The cell membrane category included both membrane proteins and membrane-related structures, which were further subdivided into: (1) transmembrane proteins: SL2L3, NPT2A, AT1A1, RAB3D, VINC, BLTP2, CAVN1, AT1A4, HCN1, GRM3, PLXA1, PLXA4, NLGN3, BIN1, and others; (2) peripheral membrane proteins: STRN, AP3B2, KCRS, KPCA, and CXA1; and (3) cell junction-related proteins: SI1L3, RAP1B, VAPA, VINC, and TLN2. The intracellular category was divided into cytoplasmic proteins, cytosolic proteins, and organelle-specific proteins. Given that organelle membranes are critical components of membrane fractions, we further divided intracellular proteins into membrane-associated (NDUS1, ADT1, BDH, ECHB, VDAC1, VAT1, and others) and non-membrane-associated proteins (SOD2, CH60, PCCB, SYIM, MDH2, ETFB, SARDH, and others). Overall, 37.1% of isoD-containing proteins were located in membrane and membrane-related regions, and 12.7% were enriched in the cytoskeletal and extracellular regions (Figure E). These results indicate that, contrary to the previously understood cytosolic function of PCMT1, the enzyme also plays a role in protein repair within the extracellular and membrane-associated regions.

Functional enrichment analysis using Gene Ontology revealed that N-to-isoD sites had a similar enrichment proportion in cytoskeletal (9.9%) and extracellular (3.2%) proteins but showed a decreased proportion in cell membrane proteins (17.4%) and an increased proportion in intracellular membrane-associated proteins (16.6%; Figure F). Overall, the higher prevalence of N-to-isoD modifications in intracellular proteins (69.6%) aligns with the previously recognized cytosolic function of PCMT1. These findings offer new insights into N-to-isoD modifications and their cellular distribution. However, only 30 isoD-carrying proteins were identified in both the D-isoD and N-isoD groups (Figure G). The D-isoD site differs from the N-isoD site because it can be repaired to the native D form by PCMT1. Therefore, further research is needed to better distinguish the functional differences between D-isoD and N-isoD.

IsoD-Carrying Proteins are Mostly Long-Lived and Enriched in the Extracellular Space

Approximately 49.8% of N-isoD-carrying proteins and 47% of D-isoD-carrying proteins were localized to the extracellular and membrane regions of the cell (Figure E,F). Additionally, cytoskeletal and membrane components were enriched in various tissues of Pcmt1 KO mice (Figure S1). To further investigate the role of PCMT1 in the extracellular space, we performed GO enrichment analysis for isoD-carrying proteins across different tissues. Among the eight tissues analyzed, only biological process (BP) and cellular component (CC) terms were significantly enriched (Figure A, Figures S2 and S3A). Of the nine CC terms identified, four were associated with the extracellular space, three with the cytoskeleton, and two with the membrane component (Figure A). These results provide further evidence that the extracellular space and membrane regions are crucial sites for PCMT1’s protein repair function.

3.

Proteins carrying D to the isoD site were enriched in extracellular and membrane compartments. (A) Cytoskeleton- and membrane-related terms were enriched in various tissues. Terms with p-values < 0.05 were shown. Terms in the liver with p-values > 0.11 were excluded from this graph. (B) Expression levels of D-isoD-carrying proteins were increased in KO mice. IsoD-proteins identified in tris-labeled MS were used to determine their corresponding protein levels in the proteomics results. Fold change = ratio (protein intensity in KO/protein intensity in WT). (C) Heatmap of the protein levels in different tissues. Log10 (intensity of protein) was used for comparison. The top 10% of proteins coexpressed in multiple tissues were shown. All groups had p-values < 0.05. Proteins with D-to-isoD sites were marked with green stars. (D) The half-life of D-isoD-carrying proteins was significantly longer than that of global proteins. ***p < 0.001, unpaired Students t-test.

To further investigate the effects of PCMT1 knockout on protein levels, we performed a global proteomics analysis on eight tissues. In the proteomics results, the expression levels of D-isoD-containing proteins were first compared between WT and KO mice. Most D-isoD-carrying proteins exhibited fold changes greater than 2 (Figure B), indicating an increase in protein levels of isoD-containing proteins in KO mice compared to WT controls. Additionally, global protein levels were analyzed in eight tissues from both WT and KO mice, and the results were visualized in a heatmap (Figure C). D-isoD-carrying proteins (marked with green stars) were notably enriched, reflecting significant changes in their protein levels. The expression levels of N-isoD-containing proteins were also detected and were consistent with those of D–isoD (Figure S3B,C). These findings suggest that protein isomerization contributes to the accumulation of isoD-containing proteins in the absence of PCMT1.

It has been reported that some long-lived proteins (LLPs) accumulate aspartic acid residue isomerization over time, which affects their structure and function. To explore the connection between isoD-carrying proteins and LLPs, we predicted the half-life of proteins using ExPASy ProtParam (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/). The accession numbers of global and isoD-carrying proteins (both D-isoD and N-isoD) were submitted separately, and their instability index (II) and classifications across eight tissues were analyzed and summarized. The analysis revealed that the half-life of isoD-carrying proteins was significantly longer than that of global proteins (Figures D and S3D).

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the characteristics of proteins significantly altered in Pcmt1 KO mice, we conducted GO analysis based on the proteomics results from 8 tissues (Figure S4 and S5). In the cellular component (CC) category, terms related to the cytoskeleton and membrane components were enriched across all tissues. For example, distal axon and synaptic membrane in the brain, cortical cytoskeleton and adherens junction in the kidney, and cell projection membrane in the colon were identified. This aligns with the GO results of isoD-carrying proteins (Figure S2), suggesting that PCMT1 primarily performs its protein repair function in the extracellular and membrane regions of the cell. Based on the GO results, terms enriched in 8 tissues were also summarized. Seven out of eleven (63.6%) terms were related to the cytoskeleton, including microtubules, myofibrils, contractile fibers, and sarcomere structures (I band, A band, Z disc). Membrane-related terms such as membrane raft, plasma membrane, and cell cortex were also enriched (Figure A). These findings further support the conclusion that PCMT1’s protein repair function is primarily active in the extracellular and membrane-associated regions of the cell.

4.

High correlation between transcriptomics and proteomics. (A,B) Cellular component terms enriched in eight tissues based on transcriptomics and proteomics data. Pathways are ordered by fold enrichment, with only terms with p-value < 0.05 displayed. (C) Comparison of mRNA across different tissues. The top 20% of coexpressed mRNA across multiple tissues are shown. Groups with p-value < 0.05 are included, and genes encoding isoD-carrying proteins are marked with green stars. (D) Correlation between proteomics and transcriptomics across eight tissues. Red points represent terms identified in both data sets, while green points indicate terms not identified. Over 98% of terms were found in both datasets. (E) The top 10 terms are sorted by p-value and compared between proteomics and transcriptomics. The width of the connecting line represents the proportion within each dataset.

High Correlation Between Genomics and Proteomics

Cells regulate protein production at multiple levels, with protein abundance reflecting the integration of various processes, from mRNA synthesis to protein degradation. To assess the global impact of mRNA expression in Pcmt1 KO mice, we performed transcriptomics on total RNA from various tissues of KO and WT mice. Differential expression analysis identified 7084 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (log2 (fold change) ≥ 2, p < 0.05) in KO mice, with 3983 genes upregulated and 3101 genes downregulated. The top 20% of DEGs, prioritized by fold change, were summarized in a heatmap, with the protein carrying D–isoD (Ddx1) marked with a green star and proteins carrying N-isoD (Eno1, Ank2) marked with purple stars (Figure C and S6).

After identifying differentially expressed genes, we integrated transcriptomic data from eight tissues to perform GO enrichment analysis, prioritizing terms based on their fold enrichment (Figures S7 and S8). This revealed significant enrichment of cytoskeleton-related cellular components (CC), along with pathways associated with membrane composition and transporters, such as the collagen-containing extracellular matrix and the apical part of the cell (Figures B and S7). To integrate proteomics with transcriptomics data, we performed a joint GO analysis using a Sankey diagram, which showed over 98% term overlap between the two datasets (Figure D). Key pathways, like the apical part of cell, lamellipodium, and focal adhesion, were unique to differentially expressed genes. In contrast, sarcomere, contractile fiber, and myofibril were specific to differentially abundant proteins. Shared pathways included the cell leading edge and spindle (Figure E).

Interactome of PCMT1 Identified Its Substrate

To explore PCMT1 function, we employed a DTBP cross-linking immunoprecipitation (IP)-based liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) approach. Cells expressing PCMT-HA or Luc-HA (control) were treated with DTBP (ditert-butyl peroxide) to covalently cross-link interacting proteins, thereby stabilizing transient interactions. The protein complexes were then captured using anti-HA antibodies, followed by mass spectrometry (MS) analysis to identify coimmunoprecipitated proteins. Proteins enriched in the PCMT-HA sample compared with the Luc-HA control were considered potential interactors. This method enabled the identification of novel binding partners of PCMT1 and provided insights into its functional interactome.

We investigated the interacting proteins of PCMT1 in ovarian cancer cells (SKOV3), embryonic kidney cells (293T), and renal epithelial cells (HK2) and performed intersection analysis. The interactome profiles identified by IP-MS in these three cell types were highly divergent, with no common substrates identified (Figure A). Structural analysis of PCMT1 showed that its active center is located on the protein surface. This region lacks typical substrate recognition motifs, suggesting that PCMT1 may have a broad substrate recognition range (Figure B). This discrepancy could be attributed to differences in protein expression profiles across the different cell types and also suggests that PCMT1 substrates may not be highly specific. Substrate interactions were also analyzed using STRING (https://cn.string-db.org/), and clusters were classified using the K-means algorithm with a high-confidence threshold of 0.7. ECM proteoglycans were clustered, with substrates labeled in red (Figure C). The color of the nodes represents the biological process (BP) associated with substrates: red for cytoskeleton organization, blue for organelle organization, and green for cellular component organization or biogenesis. These findings support the hypothesis that PCMT1 substrates may not be highly specific, with some related to ECM. GO enrichment analysis of substrates further confirmed this, showing enrichment in cytoskeleton-related and membrane-related components in terms of the cellular component (CC) (Figure D and S9), consistent with findings from isoD-carrying substrates, global proteomics substrates, and transcriptomics data.

5.

Interactome Analysis of PCMT1 using immunoprecipitation followed by MS (IP-MS). (A) Venn diagram of the interacting proteins in SKOV3, HK2, and 293T cells, and the overlap between proteomics and transcriptomics candidates. (B) Protein structure of PCMT1 is shown using PyMOL. (C) Interaction among the substrates of PCMT1. Most substrates were not clustered, except ECM proteoglycans, which were clustered (labeled in color). (D) Overlapping substrates from both proteomics and transcriptomics were more enriched in cytoskeleton- and membrane-related components.

Substrates of PCMT1 Under Stress Conditions Were Identified

Isoaspartate accumulated under aging and stress conditions, such as oxidative stress and heat. To further understand the role of PCMT1 under stress conditions, we identified the substrates using Tris-label MS in SKOV3 cells. The mRNA level of Hsp70 increased significantly after exposure to 40 °C for 3 h (Figure A). Under 1% O2, the mRNA level of HIF1α decreased (Figure B), while VEGFA increased (Figure C), indicating that SKOV3 cells successfully responded to the stress conditions. LC-MS analysis of treated and control cells revealed a high proportion of D-isoD-carrying proteins in the stressed group (Figure D). The subcellular localization of D-isoD-carrying proteins was also examined, with proteins in the extracellular space and region highlighted with red stars (Figure E,H). Notably, the proportion of D-isoD-carrying proteins in the extracellular space/region was higher than in other locations under both heat and hypoxic stress conditions (Figure F,I). Specifically, 37% of the proteins in the extracellular space under heat stress were D-isoD-carrying proteins (Figure G), while 17% of the proteins in the extracellular space under hypoxic stress were D-isoD-carrying proteins (Figure J). For N-isoD-carrying proteins, the presence of PCMT1 reduced l-asparaginyl deamidation under control conditions but not under stress conditions (Figure K). Notably, the proportion of N-isoD-carrying proteins was higher in the extracellular space/region (Figure L) and cytoskeleton (Figure M). These findings suggest that isoD-carrying proteins accumulate under stress, particularly in the extracellular matrix (ECM), consistent with our multiomics data.

6.

N-isoD-containing proteins were less than the D-isoD protein under stress conditions. (A) Increased mRNA levels of heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70), **p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA with Tukeys test. (B,C) mRNA levels of hypoxia markers Vegfa and Hif1α. The mRNA level of Vegfa was increased, while Hif1α decreased under 1% O2, ***p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Tukeys test. (D) Ratio of D-isoD-carrying proteins under 40 °C and hypoxia stress in the mass spectrum. (E) Substrates containing D-isoD sites under 40 °C compared with 37 °C. Extracellular space and extracellular region were labeled with red or blue, respectively. D-isoD-carrying proteins were labeled with red stars. (F) Subcellular distribution of substrates of PCMT1 under 40 °C. (G) Ratio of D-isoD-carrying proteins in extracellular and other parts under 40 °C. (H) Substrates containing D-isoD sites under 1% O2 compared with the control. Extracellular space and extracellular region were labeled with red or blue, respectively. D-isoD-carrying proteins were labeled with red stars. (I) Subcellular distribution of substrates of PCMT1 under 1% O2. (J) Ratio of D-isoD-carrying proteins in extracellular and other parts under 1% O2. (K) Ratio of N-isoD carrying proteins under 40 °C and hypoxia stress in the mass spectrum. (L) Substrates containing the N-isoD site under 40 °C compared with 37 °C. Extracellular space and extracellular region were labeled with red or blue, respectively. (M) Substrates containing N-isoD site under 1% O2 compared with the control. Intermediate filaments and polymeric cytoskeletal fibers were labeled with red or blue, respectively.

Discussion

In our study, the integrative multiomics analysis of Pcmt1 knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice provides comprehensive insights into the enzyme’s biological functions. Transcriptomic and proteomic data integration revealed significant overlaps in enriched pathways, particularly those related to cytoskeletal organization and membrane-associated functions. Both unique and shared pathways between differentially expressed genes and proteins highlighted PCMT1-regulated processes across different tissues. Furthermore, stress response analysis suggests that PCMT1 plays a role in adapting to environmental challenges. The accumulation of isoD-carrying proteins, particularly in the extracellular matrix (ECM), points to PCMT1’s potential involvement in ECM remodeling or signaling under stress conditions.

Previous studies have suggested that the cytosolic localization of PCMT1 limits its repair activity to the cytosol and nucleus, leading to the accumulation of damaged aspartyl residues in organelles or extracellular proteins, which may be processed by alternative mechanisms. It has also been observed that methyltransferase can access extracellular proteins when released during cell lysis, as seen in vascular injury. However, based on our previous findings and the current study, we propose that PCMT1 is secreted into the extracellular space to perform its protein repair function, with substrates including ECM and membrane proteins. Our data demonstrate that PCMT1-mediated repair is primarily concentrated in membrane-associated and extracellular regions, consistent with its function in maintaining the structural integrity of cellular interfaces. The significant representation of membrane proteins (37.1%) among isoD-carrying proteins underscores the importance of PCMT1 in preserving membrane dynamics and signaling. Additionally, subcellular fractionation studies have shown that certain protein methyltransferase activity of PCMT1 is found in membrane fractions of various cell types, such as those in the rat brain.

The accumulation of isoD-carrying proteins, particularly in the ECM, suggests a role in ECM remodeling or signaling under stress. This enrichment, especially under heat (37%) and hypoxia (17%), may contribute to maintaining extracellular integrity and function, consistent with previous reports of isoaspartyl residue accumulation in ECM proteins like fibronectin and collagen I during aging or disease. , It has been shown that the NGR motif in various ECM proteins can convert to isoDGR, binding integrins and promoting immune cell activation. ,, Further investigation is required to understand how these modifications influence ECM dynamics and stress-related cellular behaviors. Intriguingly, specific clearance of isoDGR has been shown to extend the lifespan of PCMT1-deficient mice and reduce tissue inflammation. Excessive ECM deposition is associated with organ aging and fibrosis in multiple organs, including the liver, lung, and kidney. Therefore, precise studies on the accumulation of isoD in different tissues might have profound implications for understanding these aging-related diseases.

Integrating transcriptomic and proteomic data revealed overlaps in pathways related to cytoskeletal organization and membrane functions, mapping PCMT1-regulated processes. Shared pathways, such as lamellipodium formation and focal adhesion, are crucial for cellular migration and interaction, further supporting the importance of PCMT1 in maintaining cellular architecture. This finding aligns with our previous results, where PCMT1 was released from ovarian cancer cells and interacted with the ECM protein LAMB3, which binds to integrin and activates FAK-Src signaling to promote cancer cell migration and invasion.

Interactome analysis across cell lines revealed diverse PCMT1 substrates with minimal overlap, indicating broad substrate recognition for repairing isoD-carrying proteins. Substrates linked to ECM proteoglycans and cytoskeletal organization emphasize PCMT1’s role in maintaining cellular structure, supported by STRING and GO enrichment aligning with isoD proteomics findings. Isomerization, one of the most prevalent age-related modifications, and the deamidation of asparagine (Asn) and glutamine (Gln) residues are closely associated with protein turnover, development, and natural aging. These modifications also serve as molecular clocks that regulate biological processes. The isoD site reflects the state of protein modification rather than changes in protein abundance. While most proteins in the body turn over rapidly, long-lived proteins (LLPs), such as crystallins and ECM proteins, have half-lives ranging from 48 h to a human lifetime. Over time, aspartic acid residue isomerization accumulates in LLPs, significantly affecting their structure and function. Our data suggest that isoD-containing proteins have longer predicted half-lives, though causation remains uncertain. It is possible that prolonged protein half-lives enable isoD accumulation, enriching LLPs with isoD-modified species, or that isoD formation directly enhances protein stability. While this correlation is intriguing, further investigation is needed to fully understand the mechanistic link between isoD accumulation and protein stability. This association is consistent with the inherent nature of LLPs, which are less frequently turned over and thus more susceptible to nonenzymatic post-translational modifications over time, such as aspartic acid isomerization. These modifications can alter protein structure, stability, and function, potentially impairing cellular processes and contributing to aging-related pathologies. By classifying isoD-carrying proteins across eight tissues, the study further emphasizes the tissue-wide relevance of this phenomenon, opening avenues for exploring how LLPs contribute to age-related functional decline. IsoD modifications could also serve as biomarkers or therapeutic targets for addressing protein aging and related diseases.

Most proteolytic enzymes target normal L-amino acid peptide bonds, raising questions about the fate of proteins with unrepaired d-aspartyl and l-isoaspartyl residues in compartments inaccessible to repair enzymes. The recognition of l-isoaspartyl residues by methyltransferase may facilitate their “repair,” enabling proteolytic degradation and preventing the accumulation of abnormal peptides. This system ensures the efficient removal of altered proteins while avoiding abnormal peptides by the major histocompatibility complex. Consistent with this, we observed that the levels of isoD-containing proteins increased in Pcmt1 KO tissues. Interestingly, altered aspartyl residues may also promote selective degradation. For instance, damaged calmodulin has been shown to undergo ubiquitin-independent proteasome degradation, potentially due to modifications of its residues or the induction of an unfolded conformation. Therefore, the relationship between isoD and protein stability requires further systematic investigation.

The observation that acidic residues such as Asp and Glu, as well as hydrophobic residues such as Leu, are commonly located near isoD sites provides mechanistic insight into the amino acid contexts that promote isomerization. It has also been reported that the spontaneous replacement of Asp by isoAsp in a peptide sequence renders the site of exchange resistant to exo- and endoproteolysis, revealing the correlation between amino acid sequence and isomerization. A cyclic product that forms spontaneously from peptides containing a penultimate Asp, Asn, or isoAsp residue at the N-terminus has been characterized. This cyclic product is resistant to hydrolysis by leucine aminopeptidase and is not readily digested by the cell’s normal proteolytic machinery. The influence of the local sequence on the rates of isoD repair has been studied using synthetic peptides. IsoD forms most readily at sequences in which the C-flanking amino acid is relatively small and hydrophilic. The most favorable C-flanking amino acids are Gly, Ser, and His. This further confirms the influence of the local sequence on isoD formation. The acidic residues observed near the isoD site in this study, based on the post-translational sequence, provide a new perspective on isoD formation.

For a comprehensive analysis of post-translational modifications, MS-based proteomics is highly effective. However, Asp isomerization does not alter the molecular weight of the residue, necessitating specialized methods for its analysis. Classical approaches, such as top-down and bottom-up proteomics, along with ECD/ETD, can identify isoAsp peptides. Yet, these methods place high demands on sample preparation and data analysis, often requiring greater expertise in data interpretation. The integrated application of proteomics approaches and 13C-methionine tracing has proven to be an effective method for observing the conversion of Asn to Asp and methyl-Asp. However, conducting isotope-based experiments requires specific certifications for the laboratory, which limits the widespread application of this method. Tag labeling, such as Tris-labeled MS, induces a detectable +103 Da mass shift at modified aspartic acid, enabling separation from unmodified peptides under specific experimental conditions. However, detection becomes challenging if the abundance of Tris-labeled sequences is low. Additionally, peptides containing acidic repeats, which are the most likely sites of isomerization, are also difficult to label with Tris. This limitation partly explains the relatively small number of identifications obtained.

Conclusions

In summary, this study underscores the critical role of PCMT1 in maintaining cytoskeletal integrity, membrane structure, and ECM organization by repairing the isoD sites, whereas dysfunction of PCMT1 is linked to pronounced isoD accumulation in various tissues. Future research should focus on tissue-specific effects of PCMT1 loss, the biochemical mechanisms underlying its broad substrate specificity, and the potential connections to age-related diseases involving cytoskeletal disorganization. These findings position PCMT1 as a vital component of protein quality control, with significant implications for cellular and tissue homeostasis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research received support from various funding sources, including the National Key R&D Program of China (grant number 2021YFA1301400), the Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (82102184), the Shanghai high-level local university construction project (PT21011), the Shanghai 2023 “Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan” Natural Science Foundation Project (23ZR1436800), NATCM’s Project of High-level Construction of Key TCM Disciplines (ZYYZDXK-2023070), Alzheimer’s Association Research Fellowship (AARF-19-619387). We thank all the members of the Zhang, Yang, and Xu Laboratories for their insightful discussions. We also thank Mrs. Liyuan Meng and the Proteomics Platform of the Core Facility of Basic Medical Sciences, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine.

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD058971.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jproteome.4c01111.

GO analysis results of isoD-proteins from each tissue (Figure S1); biological processes of isoD-protein terms enriched in 7/8 tissues (Figure S2); proteins carrying N-to-isoD sites were enriched in extracellular and membrane compartments (Figure S3); GO analysis results of proteins identified in 8 tissues from KO and WT mice (Figure S4); molecular function (MF) and biological process (BP) terms of proteins enriched in 8 tissues (Figure S5); correlation between transcriptomics and N-isoD proteomics (Figure S6); GO analysis results of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified in 8 tissues (Figure S7); molecular function (MF) and biological process (BP) terms of genes (identified in RNA-seq) enriched in 8 tissues (Figure S8); GO enrichment of proteins identified in IP-MS of SKOV3, HK2, and 293T cells (Figure S9) (PDF)

#.

J.W. and J.X. contributed equally. Y.X., P.Z., and W.Y. conceived the project. Y.X. directed the research. Y.X. and J.W. designed the experiments. J.W., J.X., J.S., and Z.C. performed the transcriptomics and proteomics procedures and analyses. J.W. and J.X. performed the LC-MS and isomerization analyses. J.S. and Z.C. maintained the knockout mice. J.W. performed all other experiments and analyzed the data. J.W., J.X., and Y.X. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Yamazaki Y., Fujii N., Sadakane Y., Fujii N.. Differentiation and semiquantitative analysis of an isoaspartic acid in human alpha-Crystallin by postsource decay in a curved field reflectron. Anal. Chem. 2010;82(15):6384–6394. doi: 10.1021/ac100310x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chondrogianni N., Petropoulos I., Grimm S., Georgila K., Catalgol B., Friguet B., Grune T., Gonos E. S.. Protein damage, repair and proteolysis. Mol. Aspects Med. 2014;35:1–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truscott R. J. W., Schey K. L., Friedrich M. G.. Old Proteins in Man: A Field in its Infancy. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016;41(8):654–664. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Otín C., Blasco M. A., Partridge L., Serrano M., Kroemer G.. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell. 2023;186(2):243–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipp M. S., Kasturi P., Hartl F. U.. The proteostasis network and its decline in ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;20(7):421–435. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0101-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perna A. F., Castaldo P., De Santo N. G., di Carlo E., Cimmino A., Galletti P., Zappia V., Ingrosso D.. Plasma proteins containing damaged L-isoaspartyl residues are increased in uremia: implications for mechanism. Kidney Int. 2001;59(6):2299–2308. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro A., Hay A., Dzieciatkowska M., Brown B. C., Morrison E. J., Hansen K. C., Zimring J. C.. Protein-L-isoaspartate O-methyltransferase is required for in vivo control of oxidative damage in red blood cells. Haematologica. 2021;106(10):2726–2739. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2020.266676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. E., JebaMercy G., Pazhanchamy K., Guo X., Ngan S. C., Liou K. C. K., Lynn S. E., Ng S. S., Meng W., Lim S. C.. Aging-induced isoDGR-modified fibronectin activates monocytic and endothelial cells to promote atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2021;324:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2021.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Guo C., Meng Z., Zwan M. D., Chen X., Seelow S., Lundström S. L., Rodin S., Teunissen C. E., Zubarev R. A.. Testing the link between isoaspartate and Alzheimer’s disease etiology. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2023;19(4):1491–1502. doi: 10.1002/alz.12735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo H. V., Lincoln M. D., Ho C.-T.. Effect of temperature, feed moisture, and pH on protein deamidation in an extruded wheat flour. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1993;41:199–202. doi: 10.1021/jf00026a010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cloos P. A., Jensen A. L.. Age-related de-phosphorylation of proteins in dentin: a biological tool for assessment of protein age. Biogerontology. 2000;1(4):341–356. doi: 10.1023/A:1026534400435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloos P. A., Christgau S.. Post-translational modifications of proteins: implications for aging, antigen recognition, and autoimmunity. Biogerontology. 2004;5(3):139–158. doi: 10.1023/B:BGEN.0000031152.31352.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deverman B. E., Cook B. L., Manson S. R., Niederhoff R. A., Langer E. M., Rosová I., Kulans L. A., Fu X., Weinberg J. S., Heinecke J. W.. Bcl-xL deamidation is a critical switch in the regulation of the response to DNA damage. Cell. 2002;111(1):51–62. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00972-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner H., Sarg B., Grunicke H., Helliger W.. Age-dependent deamidation of H1(0) histones in chromatin of mammalian tissues. J. Cancer Res. Clin Oncol. 1999;125(3–4):182–186. doi: 10.1007/s004320050261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitaleri A., Mari S., Curnis F., Traversari C., Longhi R., Bordignon C., Corti A., Rizzardi G. P., Musco G.. Structural basis for the interaction of isoDGR with the RGD-binding site of alphavbeta3 integrin. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283(28):19757–19768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmack R. A., Boyer D. R., Zee C. T., Richards L. S., Sawaya M. R., Cascio D., Gonen T., Eisenberg D. S., Clarke S. G.. Structure of amyloid-β (20–34) with Alzheimer’s-associated isomerization at Asp23 reveals a distinct protofilament interface. Nat. Commun. 2019;10(1):3357. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11183-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curnis F., Cattaneo A., Longhi R., Sacchi A., Gasparri A. M., Pastorino F., Di Matteo P., Traversari C., Bachi A., Ponzoni M.. Critical role of flanking residues in NGR-to-isoDGR transition and CD13/integrin receptor switching. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(12):9114–9123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.044297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuchi T., Sakurako K., Katane M., Sekine M., Homma H.. The role of protein L-isoaspartyl/D-aspartyl O-methyltransferase (PIMT) in intracellular signal transduction. Chem. Biodivers. 2010;7(6):1337–1348. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200900273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curnis F., Longhi R., Crippa L., Cattaneo A., Dondossola E., Bachi A., Corti A.. Spontaneous formation of L-isoaspartate and gain of function in fibronectin. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281(47):36466–36476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604812200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavous D. A., Jackson F. R., O’Connor C. M.. Extension of the Drosophila lifespan by overexpression of a protein repair methyltransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98(26):14814–14818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251446498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenson J. D., Kim E., Young S. G., Clarke S.. Limited accumulation of damaged proteins in l-isoaspartyl (D-aspartyl) O-methyltransferase-deficient mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276(23):20695–20702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Recio I., Goikoetxea-Usandizaga N., Rejano-Gordillo C. M., Conter C., Rodríguez Agudo R., Serrano-Maciá M., Zapata-Pavas L. E., Peña-Sanfélix P., Azkargorta M., Elortza F.. et al. Modulatory effects of CNNM4 on Protein-L-Isoaspartyl-O-Methyltransferase repair function during Alcohol-Induced hepatic damage. Hepatology. 2024:10–1097. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000001156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z., Dimitrijevic A., Aswad D. W.. Accelerated protein damage in brains of PIMT± mice; a possible model for the variability of cognitive decline in human aging. Neurobiol. Aging. 2015;36(2):1029–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigneswara V., Lowenson J. D., Powell C. D., Thakur M., Bailey K., Clarke S., Ray D. E., Carter W. G.. Proteomic identification of novel substrates of a protein isoaspartyl methyltransferase repair enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281(43):32619–32629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605421200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro A., Lukens J. R., Zimring J. C.. The role of PIMT in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis: A novel hypothesis. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2023;19(11):5296–5302. doi: 10.1002/alz.13115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar C., Houser C. R., Clarke S.. Activation of the PI3K/Akt signal transduction pathway and increased levels of insulin receptor in protein repair-deficient mice. Aging Cell. 2005;4(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong J., Yuan C., Liu L., Du Y., Hui Y., Chen Z., Diao C., Yang R., Liu G., Liu X.. PCMT1 regulates the migration, invasion, and apoptosis of prostate cancer through modulating the PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β pathway. Aging. 2023;15(20):11654–11671. doi: 10.18632/aging.205152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J., Zhang J., Wang L., Liu H., Wang J., Liu J., Liu Z., Zhu Y., Xu Y., Yang W.. et al. Non-apoptotic function of caspase-8 confers prostate cancer enzalutamide resistance via NF-κB activation. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(9):833. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-04126-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J., Hou Y., Wang J., Zhang J., Wu J., Yu X., Cai H., Yang W., Xu Y., Mou S.. Repair of Isoaspartyl Residues by PCMT1 and Kidney Fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2025:10–1681. doi: 10.1681/ASN.0000000652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silzel J. W., Lambeth T. R., Julian R. R.. PIMT-Mediated Labeling of L-Isoaspartic Acid with Tris Facilitates Identification of Isomerization Sites in Long-Lived Proteins. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2022;33(3):548–556. doi: 10.1021/jasms.1c00355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers R. R., Fanélus I.. Damaged proteins bearing L-isoaspartyl residues and aging: a dynamic equilibrium between generation of isomerized forms and repair by PIMT. Curr. Aging Sci. 2011;4(1):8–18. doi: 10.2174/1874609811104010008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabadi P. G., Sankaran P. K., Palanivelu D. V., Adhikary L., Khedkar A., Chatterjee A.. Mass Spectrometry Based Mechanistic Insights into Formation of Tris Conjugates: Implications on Protein Biopharmaceutics. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2016;27(10):1677–1685. doi: 10.1007/s13361-016-1447-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigler J. S. Jr, Goosey J.. Aging of Protein Molecules - Lens Crystallins as a Model System. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1981;6(5):133–136. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(81)90050-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo S., Ingrosso D., Migliardi V., Sorrentino A., Donnarumma G., Baroni A., Masella L., Tufano M. A., Zappia M., Galletti P.. Hydroxytyrosol, a natural antioxidant from olive oil, prevents protein damage induced by long-wave ultraviolet radiation in melanoma cells. Free Radical Bio. Med. 2005;38(7):908–919. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak N. R., Putnam A. A., Addepalli B., Lowenson J. D., Chen T. S., Jankowsky E., Perry S. E., Dinkins R. D., Limbach P. A., Clarke S. G.. An ATP-Dependent, DEAD-Box RNA Helicase Loses Activity upon IsoAsp Formation but Is Restored by PROTEIN ISOASPARTYL METHYLTRANSFERASE. Plant Cell. 2013;25(7):2573–2586. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.113456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. A., Aswad D. W.. Identification and Topography of Substrates for Protein Carboxyl Methyltransferase in Synaptic Membrane and Myelin-Enriched Fractions of Bovine and Rat-Brain. J. Neurochem. 1985;45(4):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb05531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanthier J., Desrosiers R. R.. Protein L-isoaspartyl methyltransferase repairs abnormal aspartyl residues accumulated in vivo in type-I collagen and restores cell migration. Exp. Cell Res. 2004;293(1):96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta B., Park J. E., Kumar S., Hao P., Gallart-Palau X., Serra A., Ren Y., Sorokin V., Lee C. N., Ho H. H.. Monocyte adhesion to atherosclerotic matrix proteins is enhanced by Asn-Gly-Arg deamidation. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):5765. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06202-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalailingam P., Mohd-Kahliab K. H., Ngan S. C., Iyappan R., Melekh E., Lu T., Zien G. W., Sharma B., Guo T., MacNeil A. J.. Immunotherapy targeting isoDGR-protein damage extends lifespan in a mouse model of protein deamidation. EMBO Mol. Med. 2023;15(12):e18526. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202318526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. J., Li Y., Liu H., Zhang J. H., Wang J., Xia J., Zhang Y., Yu X., Ma J. Y., Huang M. S.. Genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 library screen identifies PCMT1 as a critical driver of ovarian cancer metastasis. J. Exp Clin Canc Res. 2022;41(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s13046-022-02242-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambeth T. R., Julian R. R.. Differentiation of peptide isomers and epimers by radical-directed dissociation. Method. Enzymol. 2019;626:67–87. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2019.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson N. E., Robinson A. B.. Amide molecular clocks in drosophila proteins: potential regulators of aging and other processes. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2004;125(4):259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor C. M.. 13 Protein L-isoaspartyl, D-aspartyl O-methyltransferases: Catalysts for protein repair. Enzymes. 2006;24:385–433. doi: 10.1016/S1874-6047(06)80015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarcsa E., Szymanska G., Lecker S., O’Connor C. M., Goldberg A. L.. Ca-free calmodulin and calmodulin damaged by aging are selectively degraded by 26 S proteasomes without ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(27):20295–20301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001555200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhme L., Bär J. W., Hoffmann T., Manhart S., Ludwig H. H., Rosche F., Demuth H. U.. Isoaspartate residues dramatically influence substrate recognition and turnover by proteases. Biol. Chem. 2008;389(8):1043–1053. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons B., Kwan A. H., Truscott R.. Spontaneous cyclization of polypeptides with a penultimate Asp, Asn or isoAsp at the N-terminus and implications for cleavage by aminopeptidase. Febs J. 2014;281(13):2945–2955. doi: 10.1111/febs.12833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reissner K. J., Aswad D. W.. Deamidation and isoaspartate formation in proteins: unwanted alterations or surreptitious signals? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2003;60(7):1281–1295. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2287-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisz J. A., Nemkov T., Dzieciatkowska M., Culp-Hill R., Stefanoni D., Hill R. C., Yoshida T., Dunham A., Kanias T., Dumont L. J.. Methylation of protein aspartates and deamidated asparagines as a function of blood bank storage and oxidative stress in human red blood cells. Transfusion. 2018;58(12):2978–2991. doi: 10.1111/trf.14936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD058971.