Abstract

Background

Abstinence‐plus interventions promote sexual abstinence as the best means of preventing acquisition of HIV, but also encourage safer‐sex strategies (eg condom use) for sexually active participants.

Objectives

To assess the effects of abstinence‐plus programs for HIV prevention in high‐income countries.

Search methods

We searched 30 electronic databases (eg CENTRAL, PubMed, EMBASE, AIDSLINE, PsycINFO) ending February 2007. Cross‐referencing, hand‐searching, and contacting experts yielded additional citations.

Selection criteria

We included randomized and quasi‐randomized controlled trials evaluating abstinence‐plus interventions in high‐income countries (as defined by the World Bank). Interventions were any efforts that encouraged sexual abstinence as the best means of HIV prevention, but also promoted safer sex. Results were self‐reported biological outcomes, behavioral outcomes, and HIV knowledge.

Data collection and analysis

Three reviewers independently appraised 20070 citations and 325 full‐text papers for inclusion and methodological quality; 39 evaluations were included. Due to heterogeneity and data unavailability, we presented the results of individual studies instead of a meta‐analysis.

Main results

Studies enrolled 37724 North American youth; participants were ethnically diverse. Programs took place in schools (10), community facilities (24), both schools and community facilities (2), healthcare facilities (2), and family homes (1). Median final follow‐up occurred 12 months after baseline.

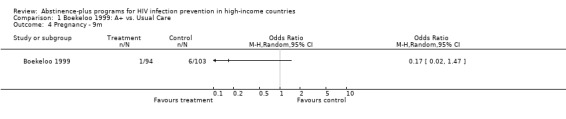

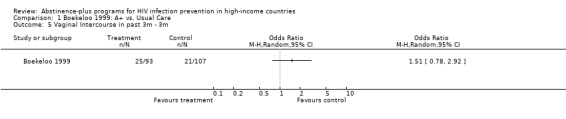

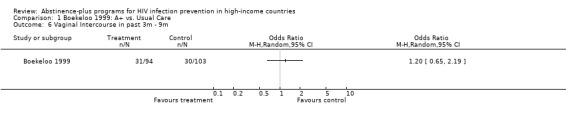

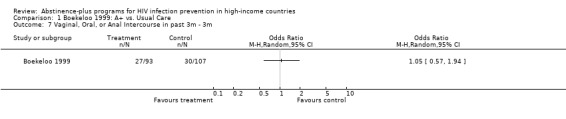

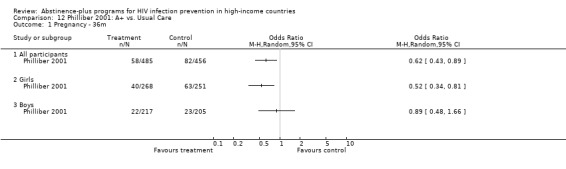

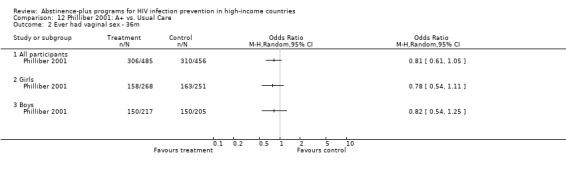

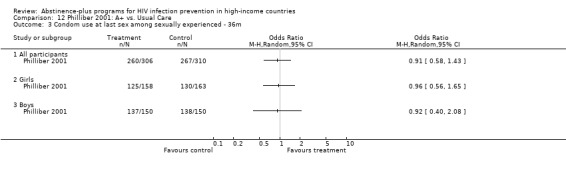

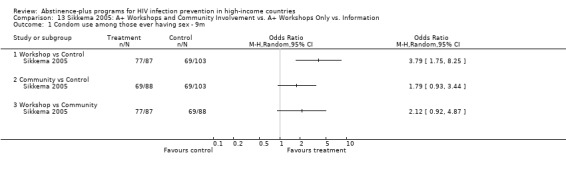

Results showed no evidence that abstinence‐plus programs can affect self‐reported sexually transmitted infection (STI) incidence, and limited evidence that programs can reduce self‐reported pregnancy incidence. Results for behavioral outcomes were promising; 23 of 39 evaluations found a significantly protective intervention effect for at least one behavioral outcome. Consistently favorable program effects were found for HIV knowledge.

No adverse effects were observed. Several evaluations found that one version of an abstinence‐plus program was more effective than another, suggesting that more research into intervention mechanisms is warranted.

Methodological strengths included large samples and statistical controls for baseline values. Weaknesses included under‐utilization of relevant outcomes, self‐report bias, and analyses neglecting attrition and clustered randomization.

Authors' conclusions

Many abstinence‐plus programs appear to reduce short‐term and long‐term HIV risk behavior among youth in high‐income countries. Evidence for program effects on biological measures is limited. Evaluations consistently show no adverse program effects for any outcomes, including the incidence and frequency of sexual activity. Trials comparing abstinence‐only, abstinence‐plus, and safer‐sex interventions are needed.

Keywords: Humans, Developed Countries, Sexual Abstinence, HIV Infections, HIV Infections/prevention & control, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Safe Sex

Plain language summary

Abstinence‐plus programs for preventing HIV infection in high‐income countries (as defined by the World Bank)

Abstinence‐plus programs are widespread interventions that primarily target young people. On the premise that sexual abstinence is the best way to prevent HIV, abstinence‐plus interventions aim to prevent, stop, or decrease sexual activity; however, programs also promote condom use and other safer‐sexstrategies as alternatives for sexually active participants. Abstinence‐plus programs differ from abstinence‐only interventions, which promote abstinence as the exclusive means of HIV prevention without encouraging safer sex.

This review included 39 randomized and quasi‐randomized controlled trials comparing abstinence‐plus programs to various control groups (eg "usual care," no intervention). Although we conducted an extensive international search for trials, all included studies were conducted among youth in the US, Canada, and the Bahamas (total baseline enrolment=37724 participants). The included programs took place in schools, community centers, and healthcare facilities. We did not conduct a meta‐analysis because of missing data and variation in program designs.

Using various control groups, 24 of 39 evaluations showed a significantly protective intervention effect on at least one biological or behavioral outcome at short‐term, medium‐term, or long‐term follow‐up. Eight trials found no evidence that abstinence‐plus programs affect self‐reported sexually transmitted infection (STI) incidence and limited evidence that programs have a protective effect on self‐reported pregnancy incidence. Results for behavioral outcomes were inconsistent across studies. Findings in almost every trial assessing HIV‐related knowledge favored the intervention group over controls. No harms were observed for any outcome, including incidence and frequency of sexual activity.

Limitations for this review include underreporting of relevant outcomes, reliance on program participants to report their behaviors accurately, and methodological weaknesses in the trials.

Background

Although over two decades have passed since the first AIDS diagnosis, an effective and accessible HIV vaccine remains a distant hope. More than 7600 people died from AIDS‐related causes each day in 2005, while an estimated 38.6 million people worldwide were living with HIV (UNAIDS 2006). Poverty and structural violence, insufficient prevention efforts, and rapid viral evolution contribute to the spread of this "modern plague" (Farmer 2001); approximately 4.1 million new infections occurred in 2005 alone (UNAIDS 2006). In the absence of a vaccine, HIV prevention programs demand continued attention. The HIV pandemic is most devastating for middle‐ and low‐income nations, but new infections continue mounting even in countries with many resources for prevention (Jaffe 2004). The World Health Organization estimated in 2004 that 1.6 million people in high‐income countries were living with HIV (UNAIDS 2004); by 2005, 2.0 million individuals in North America, Western Europe, and Central Europe alone were living with HIV, and 65000 became newly infected in these three regions (UNAIDS 2006). The widespread availability of antiretroviral treatment (ART) allows many individuals in high‐income countries to live longer and healthier lives than their counterparts in resource‐poor countries, but ART is not a cure. Furthermore, even if ART could eliminate the virus, it would still be desirable to prevent the spread of HIV. Primary prevention efforts are still necessary in high‐income countries, particularly among high‐risk groups.

High‐income economies are defined by the World Bank by gross national income as those with a gross national income per capita of $10,726 or higher: Andorra, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Australia, Austria, the Bahamas, Bahrain, Belgium, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Cayman Islands, Channel Islands, Cyprus, Denmark, Faeroe Islands, Finland, France, French Polynesia, Germany, Greece, Greenland, Guam, Hong Kong (China), Iceland, Ireland, Isle of Man, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea Rep., Kuwait, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Macao (China), Malta, Monaco, Netherlands, Netherlands Antilles, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Puerto Rico, Qatar, San Marino, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United States, US Virgin Islands (World Bank 2007).

Sexual behavior outpaces drug injecting as the major cause of HIV infection in many high‐income countries. Studies from the United States suggest that over 70% of HIV‐positive men and women may remain sexually active, and a substantial percentage continue to engage in unprotected sex (Crepaz 2002). The rising prevalence of other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as gonorrhea and chlamydia, indicates increased risky sexual behavior in Australia, Western Europe, Japan, and the US. Although sex between men still accounts for most new infections in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Greece, New Zealand, and the US, evidence suggests that heterosexual sex is responsible for an increasing proportion of seroconversions (UNAIDS 2004). For example, according to UK figures, heterosexual sex accounted for 66% of all new infections in 2003 (AVERT 2005). Major risk groups vary by region (Rivers 2000), but evidence suggests that HIV is now disproportionately concentrated among youth, ethnic minority groups, men who have sex with men, women, and recent immigrants (UNAIDS 2006, Berry 2005, AVERT 2005). In the current socio‐epidemiological climate, primary prevention programs targeting sexual risk behavior are essential for all groups.

Description of the intervention Various behavioral interventions have proven effective in reducing HIV‐risk behaviors in high‐income countries, but a number of prevention strategies still require rigorous evaluation. Abstinence‐based programs are one such approach, consisting of abstinence‐plus and abstinence‐only approaches. The term "abstinence‐based" indicates that the interventions promote sexual abstinence as the best means of HIV infection prevention.

Abstinence‐plus interventions are conducted in a variety of formats, but all use a hierarchical approach to promote sexual abstinence and then safer sex for the prevention of HIV. These interventions convey the message that sexual abstinence is the best or safest behavior choice; interventions encourage both primary abstinence (remaining a virgin) and secondary abstinence (returning to abstinence after experiencing sex in the past). Recognizing that some participants do choose to have sex, abstinence‐plus programs then also encourage sexually active participants to use condoms, limit their number of sexual partners, or practice other safer‐sex behaviors. Abstinence‐plus interventions also typically include extensive information on sexually transmitted infections, pregnancy, contraception, and HIV.

Theoretical bases for abstinence‐plus programs have included social learning theory, the health belief model, the theory of reasoned action, and the theory of planned behavior, and social cognitive theory. The primary targets for abstinence‐based programs are youth, and although the interventions often occur in school settings, they are also implemented in community settings, after‐school groups, clinics, and via media‐based campaigns. These interventions often incorporate or address family involvement, school influences, and community norms as factors that influence behavior, but abstinence‐plus programs fundamentally encourage abstinence and safer sex as individual‐level choices.

Notably, abstinence‐plus programs differ from abstinence‐only programs. Abstinence‐only programs emphasize abstinence as the exclusive means of sexual risk reduction, without encouraging condom use, partner reduction, or other safer‐sex strategies as alternatives for sexually active participants. While abstinence‐only programs present participants with a strict dichotomy (abstinence or sexual activity), abstinence‐plus programs offer participants a pyramid of risk reduction behaviors, in which abstinence is promoted as the safest choice, but then followed by safer sex.

Terminology complicates the discussion of abstinence‐plus programs: programs differ in their specific definitions of "abstinence" and "sex," and possible definitions for these terms vary widely (Haglund 2002, Horan 1998, Pitts 2001, Remez 2000, Sanders 1999, Sonfield 2001). Furthermore, various terms have been used to describe abstinence‐plus interventions, including "comprehensive," "safer‐sex," and "abstinence‐oriented" approaches. Regardless of terminology, programs were included in this review if they used a sexual risk behavior hierarchy that promoted abstinence from any type of sexual activity as the best, but not the only means of preventing the sexual acquisition of HIV.

Why it is important to do this review Although a number of reviews have commented specifically on the intervention effects of abstinence‐only programs (NHS 1997, DiCenso 2002, Franklin 1997, Kirby 2001, Kirby 2006, and Thomas 2000), we have found very few that have specifically defined and discussed the effects of abstinence‐plus interventions. Instead, abstinence‐plus interventions are often reviewed alongside safer‐sex or abstinence‐only programs (eg in Kirby 2006, Jemmott 2000, Kim 1997, Pedlow 2003, Robin 2004), and it can be difficult to determine which programs use a hierarchy and which do not. Bennett 2005 and Manlove 2004 have both evaluated abstinence‐plus programs alongside abstinence‐only approaches, but these reviews focused on pregnancy prevention instead of HIV, and they were limited to programs for United States adolescents. Frost 1995 also evaluated abstinence‐plus programs for pregnancy prevention in US youth, but this was a narrative review without a systematic search strategy. Abstinence‐only and abstinence‐plus programs have been jointly reviewed in the developing world (O'Reilly 2004, O'Reilly 2006); this review found one abstinence‐only and nine abstinence‐plus program evaluations, grouped the evaluations for analysis, and concluded that the interventions had "no impacts on condom use" and a "minimal, but significant effect on abstinence." As yet, however, no reviews exist for high‐income countries. We believe that an international search, a focus on HIV‐related outcomes, and the separation of abstinence‐only from abstinence‐plus programs are required to understand the effects of abstinence‐based programs for HIV prevention in high‐income countries.

Beyond the scientific rationale for this review, a review of abstinence‐plus programs is politically important, not least because abstinence‐plus programs are popular and widespread. Abstinence‐plus programs with a youth focus are particularly common in the United States: a nationally representative US survey of 825 school districts in 1999 discovered that 69% of districts had a specific policy for teaching sex education; of these, 51% districts used abstinence‐plus programs and 35% used abstinence‐only programs (Landry 1999). (The remaining 14% presented abstinence as one option for HIV prevention, but did not state that abstinence was the preferred choice.) This estimate of abstinence‐plus program prevalence does not account for programs that take place outside school settings, and little is known regarding the uptake of abstinence‐plus programs in high‐income countries other than the US.

Abstinence‐based programs, including both abstinence‐only and abstinence‐plus interventions, are also the subject of continuing political debate. Abstinence‐only interventions are frequently criticized for promoting sexual abstinence as the exclusive prevention strategy; one criticism is that the omission of safer sex strategies makes abstinence‐only interventions ineffective or inapplicable to participants who do engage in sexual activity (DiClemente 1998, HRW 2002, Lancet 2004, Lancet 2002, Lancet 2006, Walgate 2004). In contrast, abstinence‐plus programs have been opposed on the grounds that promoting safer sex along with abstinence can "undermine the abstinence message" (Haskins 1997). Critics suggest that safer‐sex promotion can send confusing mixed messages to program participants, "implicitly condone sexual activity among teens," or make participants more likely to engage in sex (Rector 2002). It is also important to investigate whether the abstinence promotion component of abstinence‐plus programs detracts from the effectiveness of safer‐sex messages. By separately reviewing the evidence for abstinence‐only and abstinence‐plus interventions, we aim to address these criticisms directly.

To date, there has been no systematic analysis of the effects of abstinence‐plus programs on HIV prevention among all residents of high‐income countries. This review seeks to identify, synthesize, and evaluate the effects of abstinence‐plus interventions on HIV‐risk behavior and HIV transmission among participants in high‐income countries. This review is a complement to our previous review of abstinence‐only interventions (Underhill 2007b, Underhill 2005, Underhill 2006a, Underhill 2006b); it has also been published in abridged form (Underhill 2007a).

Objectives

To determine the effects of abstinence‐plus programs for preventing HIV infection among participants in high‐income countries.

The interventions were any planned efforts intended to increase rates of abstinence as the best means of HIV prevention, but also intended to increase safer‐sex behaviors such as condom use, partner reduction, or decreased frequency of unprotected sex. The participants were anyone in high‐income countries. Our primary outcome measures were HIV, other STIs, and pregnancy, although we included any trials that assessed a behavioral or biological outcome. We included studies comparing abstinence‐plus programs with the following interventions: no intervention; HIV‐unrelated programs comparable in time and format (ie "attention controls"; for example, these might include a program involving the same activities and the same number of sessions, but focused on abstinence from drugs, not sex); abstinence‐only HIV prevention programs; other abstinence‐plus HIV prevention programs; and HIV prevention programs that did not emphasize abstinence.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only controlled interventions that evaluated the effects of abstinence‐plus programs designed to influence behavior change on at least one outcome measure related to HIV transmission. These included randomized and quasi‐randomized controlled trials. We defined quasi‐randomized controlled trials as those that approximated randomization by using a method of allocation that was unlikely to lead to consistent bias, such as flipping a coin or alternating participants. Limiting the review to randomized and quasi‐randomized controlled trials was practical because many of the primary outcomes were self‐reported, and random allocation is important to control for both known and unknown confounding. If a meta‐analysis had been feasible, we would have conducted a separate analysis on randomized controlled trials to assess the effects of methodological quality.

Types of participants

We included studies comprised of any participants that were conducted in high‐income countries, as defined by the World Bank (World Bank 2007). Participants did not need to be born in or hold citizenship in a high‐income country, but they must have been present in a high‐income country when the intervention took place. No exclusions were made by intervention setting (eg clinic, school, community center, faith‐based organization) or primary risk group. Because our focus was primary prevention, studies restricted to participants who were already HIV positive were excluded. No exclusions were made by gender, age, sexual orientation, language, occupation, racial or ethnic group, or other characteristics.

Types of interventions

"Abstinence" may be clinically defined as refraining from vaginal, anal, and oral sex. Given inconsistent definitions, this review included studies encouraging abstinence from any one or a combination of these behaviors. We made no exclusions by type of organization delivering the programs (eg schools, healthcare providers, community‐based organizations, faith‐based organizations).

Criteria for abstinence‐plus interventions included the following: 1. the intervention was a planned effort to encourage sexual abstinence or a return to sexual abstinence as the best means of HIV prevention; 2. specific outcomes of interest were presented; 3. HIV prevention was a stated goal of the intervention; 4. the program also promoted condom use, partner reduction, or any other safer‐sex behavior as an alternative to abstinence.

We included studies that used the following comparison groups: 1. no intervention; 2. attention control: interventions that were equal in format and time, but targeted HIV‐unrelated behaviors. For example, a comparison group might have received an intervention with the same number of sessions and the same activities, but the control intervention could have focused on refusing gang membership instead of abstaining from sexual activity; 3. interventions that did not encourage abstinence as a primary outcome (eg condom promotion programs, didactic HIV information sessions); 4. abstinence‐only programs; 5. comparisons between enhanced and non‐enhanced versions of the same program; 6. usual care as defined by the trialist.

Types of outcome measures

Studies reporting outcome measures directly related to HIV transmission (ie self‐reported risk behavior and biological outcomes) were included. Biological (primary) outcomes included the incidence of STIs, HIV, and pregnancy. Examples of risk behavior outcomes included condom use, number of sexual partners, and frequency of unprotected intercourse. If reports included a summary measure of sexual risk, authors were contacted for data on specific outcomes. Where possible, we also examined outcome measures relevant to HIV knowledge, adverse outcomes, program fidelity, cost‐effectiveness, and intervention acceptability.

Biological (primary) outcome measures

HIV incidence

STI incidence

Pregnancy incidence

Behavioral (secondary) outcome measures

Incidence and frequency of unprotected vaginal sex

Incidence and frequency of unprotected oral sex

Incidence and frequency of unprotected anal sex

Incidence and frequency of any vaginal sex

Incidence and frequency of any oral sex

Incidence and frequency of any anal sex

Number of sex partners

Use of male condoms

Use of female condoms

Abstaining from sex if condoms are not used

Duration of abstinence post‐intervention

Return to abstinence (for those who were previously sexually active)

Incidence of sexual initiation

Search methods for identification of studies

We refined our search strategy with recommendations from the Cochrane HIV/AIDS Review Group. No language restrictions were imposed, and translations were sought where necessary. No restrictions on journal of publication were imposed. No country names or other geographical terms were used in the search. Most databases were searched from 1980 onward. Full search strategies for each database are included in Table 1.

1. Search Strategies for Electronic Databases.

| Database | Years Searched | Strategy | Total Records |

| ADOLEC | Inception‐2007 | Inception ‐ 2005, Total Records Retrieved: 504 Search terms: ABSTINENCE [Words] and SEX [Words] and HIV [Words], SEX [Words] and POSTPONE [Words] or ABSTAIN [Words], VIRGIN [Words] or CHASTITY [Words] or CELIBATE [Words], SEX [Words] and EDUCATION [Words] and HIV [Words]. Examined all records. 2005‐2007, Total Records Retrieved: 87 Search terms: sex and education [Palavras] and hiv [Palavras] and 2005 or 2006 or 2007 [País, ano de publicação], abstain and sex, abstain and sex and hiv, postpone and sex, virgin or chaste or chastity or celibate. Examined all records. | 591 |

| AIDSLINE | 1980‐2007 | 1980‐2005, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 1450 #1 PT=RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL #2 PT=CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIAL #3 RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS #4 RANDOM ALLOCATION #5 DOUBLE BLIND METHOD #6 SINGLE BLIND METHOD #7 PT=CLINICAL TRIAL #8 CLINICAL TRIALS OR CLINICAL TRIALS, PHASE I OR CLINICAL TRIALS, PHASE II OR CLINICAL TRIALS, PHASE III OR CLINICAL TRIALS, PHASE IV OR CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIALS OR MULTICENTER STUDIES #9 (SINGL* OR DOUBL* OR TREBL* OR TRIPL*) NEAR6 (BLIND* OR MASK*) #10 CLIN* NEAR6 TRIAL* #11 CLIN* NEAR6 TRIAL* #12 PLACEBOS #13 RANDOM* #14 RANDOM* #15 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 #16 ANIMALS NOT (HUMAN AND ANIMALS) #17 #15 NOT #16 #18 SEXUAL ABSTINENCE [MESH] #19 ABSTINENCE OR ABSTAIN* OR CHASTITY OR CHASTE OR VIRGIN* OR CELIBA* OR (SEX* AND EDUCAT*) OR (SEX* AND (MARRIAGE* OR MARRIED)) #20 #18 OR #19 #21 #17 AND #20 AND PY=1980‐2005 2005‐2007, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 16 #1 PT=RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL #2 PT=CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIAL #3 RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS #4 RANDOM ALLOCATION #5 DOUBLE BLIND METHOD #6 SINGLE BLIND METHOD #7 PT=CLINICAL TRIAL #8 CLINICAL TRIALS OR CLINICAL TRIALS, PHASE I OR CLINICAL TRIALS, PHASE II OR CLINICAL TRIALS, PHASE III OR CLINICAL TRIALS, PHASE IV OR CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIALS OR MULTICENTER STUDIES #9 (SINGL* OR DOUBL* OR TREBL* OR TRIPL*) NEAR6 (BLIND* OR MASK*) #10 CLIN* NEAR6 TRIAL* #11 CLIN* NEAR6 TRIAL* #12 PLACEBOS #13 RANDOM* #14 RANDOM* #15 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 #16 ANIMALS NOT (HUMAN AND ANIMALS) #17 #15 NOT #16 #18 SEXUAL ABSTINENCE [MESH] #19 ABSTINENCE OR ABSTAIN* OR CHASTITY OR CHASTE OR VIRGIN* OR CELIBA* OR (SEX* AND EDUCAT*) OR (SEX* AND (MARRIAGE* OR MARRIED)) #20 #18 OR #19 #21 #17 AND #20 AND PY=2005‐2007 | 1465 |

| Bibliomap | 1887‐2007 | 1887‐2005, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 52 Search terms: EVALUATION AND SEXUAL HEALTH, ABSTINENCE AND SEX AND HIV, SEX AND (POSTPONE OR ABSTAIN), POSTPONE AND SEX, DELAY AND SEX, CHASTITY AND SEX, CHASTITY, VIRGIN, SEX AND EDUCATION AND HIV. 2005‐2007, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 154 abstinen* or abstain* or chastity or chaste or virgin* or celiba* or "sex education" | 206 |

| BIOSIS | 1969‐2007 | 1969‐2005, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 1061 (((ABSTINEN* or ABSTAIN* or postpon* or DELAY*) and SEX*) or CHASTITY or CHASTE or VIRGIN* or CELIBA* or (SEX* and EDUCAT*)) and (HIV* or AIDS*) and ((control* or trial* or random* or blind* or (clinical and trial*) or (research and design) or compar* or evaluation) not (animals not human)) 2005‐2007, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 185 #1(((ABSTINEN* or ABSTAIN* or postpon* or DELAY*) and SEX*) or CHASTITY or CHASTE or VIRGIN* or CELIBA* or (SEX* and EDUCAT*)) and (PY:BXCD = 2005‐2006) #2(HIV* or AIDS*) and (PY:BXCD = 2005‐2006) #3((control* or trial* or random* or blind* or (clinical and trial*) or (research and design) or compar* or evaluation) not (animals not human)) and (PY:BXCD = 2005‐2006) #4#1 and #2 and #3 and (PY:BXCD = 2005‐2006) *Records for 2007 were not yet available in Feb 2007. | 1246 |

| Catalog of US Government Publications | 1976‐2007 | 1976 ‐ 2005, Total Records Retrieved: 133 Search terms: Abstinence AND sex, (ABSTINEN* OR ABSTAIN* OR DELAY* OR POSTPON*) AND SEX, SEX* AND EDUCATION*, (SEX* AND EDUCATION*) AND (HIV* OR AIDS*). Examined all records. 2005‐2007, Total Records Retrieved: 295 Search terms: Abstinence AND sex, (ABSTINEN* OR ABSTAIN* OR DELAY* OR POSTPON*) AND SEX, SEX* AND EDUCATION*, (SEX* AND EDUCATION*) AND (HIV* OR AIDS*). Examined all records. | 428 |

| CENTRAL | 1980‐2007 | 1980‐2005, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 74 #1hiv OR hiv‐1* OR hiv‐2* OR hiv1 OR hiv2 OR (HIV INFECT*) OR (HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (HUMAN IMMUNEDEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (HUMAN IMMUNE‐DEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (HUMAN IMMUNO‐DEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (HUMAN IMMUN* DEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUNEDEFICIENCY SYNDROME) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUNO‐DEFICIENCY SYNDROME) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUNE‐DEFICIENCY SYNDROME) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUN* DEFICIENCY SYNDROME) in All Fields in all products #2MeSH descriptor HIV Infections explode all trees in MeSH products #3MeSH descriptor HIV explode all trees in MeSH products #4MeSH descriptor Sexually Transmitted Diseases, Viral, this term only in MeSH products #5(#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4) #6MeSH descriptor Sexual Abstinence explode all trees in MeSH products #7ABSTINENCE OR ABSTAIN* OR CHASTITY OR CHASTE OR VIRGIN* OR CELIBA* OR (SEX* AND EDUCAT*) OR (SEX* AND (MARRIAGE* OR MARRIED)) in All Fields in all products #8(#6 OR #7) #9(#5 AND #8), from 1980 to 2005 2005‐2007, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 138 #1(hiv OR hiv‐1* OR hiv‐2* OR hiv1 OR hiv2 OR (HIV INFECT*) OR (HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (HUMAN IMMUNEDEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (HUMAN IMMUNE‐DEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (HUMAN IMMUNO‐DEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (HUMAN IMMUN* DEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUNEDEFICIENCY SYNDROME) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUNO‐DEFICIENCY SYNDROME) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUNE‐DEFICIENCY SYNDROME) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUN* DEFICIENCY SYNDROME)), from 2005 to 2007 #2MeSH descriptor HIV Infections explode all trees #3MeSH descriptor HIV explode all trees #4MeSH descriptor Sexually Transmitted Diseases, Viral explode all trees #5MeSH descriptor Sexual Abstinence explode all trees #6ABSTINENCE OR ABSTAIN* OR CHASTITY OR CHASTE OR VIRGIN* OR CELIBA* OR (SEX* AND EDUCAT*) OR (SEX* AND (MARRIAGE* OR MARRIED)) #7(( #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 ) AND ( #5 OR #6 )), from 2005 to 2007 | 212 |

| CHID | 1985‐2005 | Search terms: Abstinence, Sex Education, Abstinence and Sex, examined records, most were program manuals or propaganda materials, no visible evaluations, even when using the "professional" audience filter. Examined all records. *CHID was taken off‐line in September 2006. | 0 relevant |

| CINAHL | 1982‐2007 | 1982‐2005, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 4079 (((ABSTINEN* or ABSTAIN* or postpon* or DELAY*) and SEX*) or CHASTITY or CHASTE or VIRGIN* or CELIBA* or (SEX* and EDUCAT*)) and (HIV* or AIDS*) and ((control* or trial* or random* or blind* or (clinical and trial*) or (research and design) or compar* or evaluation) not (animals not human)) 2005‐2007, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 143 #1((((ABSTINEN$ or ABSTAIN$ or postpon$ or DELAY$) and SEX$) or CHASTITY or CHASTE or VIRGIN$ or CELIBA$ or (SEX$ and EDUCAT$)) and (HIV$ or AIDS$) and ((control$ or trial$ or random$ or blind$ or (clinical and trial$) or (research and design) or compar$ or evaluation) not (animals not human))).mp. [mp=title, subject heading word, abstract, instrumentation] #2(((ABSTINEN$ or ABSTAIN$ or postpon$ or DELAY$) and SEX$) or CHASTITY or CHASTE or VIRGIN$ or CELIBA$ or (SEX$ and EDUCAT$)).mp. [mp=title, subject heading word, abstract, instrumentation] #3(HIV$ or AIDS$).mp. [mp=title, subject heading word, abstract, instrumentation] #4((control$ or trial$ or random$ or blind$ or (clinical and trial$) or (research and design) or compar$ or evaluat$) not (animals not human)).mp. [mp=title, subject heading word, abstract, instrumentation] #52 and 3 and 4 #6limit 5 to yr="2005 ‐ 2007" | 4222 |

| CSA Illumina ‐ includes ASSIA, ERIC, Political Science Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts, and Sociological Abstracts | 1963‐2007 | Sociological Abstracts [1963‐], ERIC [1991‐], ASSIA [1987‐], Political Science Abstracts [1975‐], and Social Services Abstracts [1979‐]. Searched until Febuary 15, 2007 Total Unique Records Retrieved: 1179 1975‐2005, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 841 ((ABSTINENCE OR ABSTAIN* OR CHASTITY OR CHASTE OR VIRGIN* OR CELIBA* OR (SEX* AND EDUCAT*) OR (SEX* AND (MARRIAGE* OR MARRIED))) and (HIV* or AIDS*)) and (randomized controlled trial OR controlled clinical trial OR randomized controlled trials OR random allocation OR double‐blind method OR single‐blind method OR clinical trial OR clinical trials OR random* OR research design OR comparative study OR evaluation NOT (animals NOT human)) 2005‐2007, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 338 (ABSTINENCE OR ABSTAIN* OR CHASTITY OR CHASTE OR VIRGIN* OR CELIBA* OR (SEX* AND EDUCAT*) OR (SEX* AND (MARRIAGE* OR MARRIED))) and (HIV* or AIDS*) and (randomized controlled trial OR controlled clinical trial OR randomized controlled trials OR random allocation OR double‐blind method OR single‐blind method OR clinical trial OR clinical trials OR random* OR research design OR comparative study OR evaluation NOT (animals NOT human)), Date Range: 2005‐2007 | 1179 |

| DARE | 1991‐2007 | 1991‐2005, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 127 Search terms: HIV, ABSTINENCE, VIRGINITY, VIRGIN, POSTPON* SEX, AIDS 2005‐2007, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 122 Search terms: HIV, ABSTINENCE, VIRGINITY, VIRGIN, POSTPON* SEX, AIDS | 249 |

| Dissertation Abstracts International (UMI Proquest) | 1997‐2007 | 1 KEY(abstinence) or TI(abstinence) or AB(abstinence) 2 #1 and (KEY(hiv) or TI(hiv) or AB(hiv)) | 64 |

| EMBASE | 1974‐2007 | 1980‐2005, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 622 #1 ('human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp) OR ('human immunodeficiency virus'/exp) OR (hiv:ti OR hiv:ab) OR ('hiv‐1':ti OR 'hiv‐1':ab) OR ('hiv‐2':ti OR 'hiv‐2':ab) OR ('human immunodeficiency virus':ti OR 'human immunodeficiency virus':ab) OR ('human immuno‐deficiency virus':ti OR 'human immuno‐deficiency virus':ab) OR ('human immunedeficiency virus':ti OR 'human immunedeficiency virus':ab) OR ('human immune‐deficiency virus':ti OR 'human immune‐deficiency virus':ab) OR ('acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome':ti OR 'acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome':ab) OR ('acquired immunedeficiency syndrome':ti OR 'acquired immunedeficiency syndrome':ab) OR ('acquired immunodeficiency syndrome':ti OR 'acquired immunodeficiency syndrome':ab) OR ('acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome':ti OR 'acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome':ab) #2 (random*:ti OR random*:ab) OR (factorial*:ti OR factorial*:ab) OR (cross?over*:ti OR cross?over:ab OR crossover*:ti OR crossover*:ab) OR (placebo*:ti OR placebo*:ab) OR (((doubl*:ti AND blind*:ti) OR (doubl*:ab AND blind*:ab))) OR (((singl*:ti AND blind*:ti) OR (singl*:ab AND blind*:ab))) OR (assign*:ti OR assign*:ab) OR (volunteer*:ti OR volunteer*:ab) OR ('crossover procedure'/de) OR ('double‐blind procedure'/de) OR ('single‐blind procedure'/de) OR ('randomized controlled trial'/de) OR (allocat*:ti OR allocat*:ab) #3 sexual AND 'abstinence'/exp #4 'abstinence'/de OR abstain* OR chastity OR chaste OR virgin* OR celiba* OR (sex* AND educat*) OR (sex* AND (marriage* OR married)) #5 #3 OR #4 #6 #1 AND #2 AND #5 #7 #1 AND #2 AND #5 AND [1980‐2005]/py 2005‐2007, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 83 #1exp human immunodeficiency virus infection/ or exp human immunodeficiency virus/ or hiv.ti,ab. or hiv‐1.ti,ab. or hiv‐2.ti,ab. or human immunodeficiency virus.ti,ab. or human immuno‐deficiency virus.ti,ab. or human immunedeficiency virus.ti,ab. or human immune‐deficiency virus.ti,ab. or acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome.ti,ab. or acquired immunedeficiency syndrome.ti,ab. or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.ti,ab. or acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome.ti,ab. #2(random$ or factorial or cross?over or crossover or placebo).ti,ab. or ((doubl$ and blind$).ti. or (doubl$ and blind$).ab.) or ((singl$ and blind$).ti. or (singl$ and blind$).ab.) or (assign$.ti. or assign$.ab.) or (volunteer$.ti. or volunteer$.ab.) or exp crossover procedure/ or exp double‐blind procedure/ or exp single‐blind procedure/ or exp randomized controlled trial/ or allocat$.ti,ab. #3exp abstinence/ and sex$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name] #4exp abstinence/ or abstain$.mp. or chastity.mp. or chaste.mp. or virgin$.mp. or celiba$.mp. or (sex$ and educat$).mp. or (sex$ and (marriage$ or married)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name] #53 or 4 #61 and 2 and 5 #7limit 6 to yr="2005 ‐ 2007" | 705 |

| EurasiaHealth Knowledge Multilingual Library | Inception‐2007 | Inception ‐ 2005, Total Records Retrieved: 452 Search terms: Abstinence, Abstain, Sexual health, AIDS, HIV, HIV Prevention. Examined all records. 2005‐2007, Total Records Retrieved: 488 Search terms: Abstinence, Abstain, Sexual health, AIDS, HIV, HIV Prevention. Examined all records. | 940 |

| HealthPromis | 1997‐2005 | Search Terms: HIV, AIDS, Abstinence. Examined all records. | 14 |

| OVID 2005 ‐ includes SIGLE and Global Health | 1973‐2005 | SIGLE (1980 ‐ May 28, 2005) and Global Health (1973 ‐ May 28, 2005) Total Unique Records Retrieved: 683 (((ABSTINEN* or ABSTAIN* or postpon* or DELAY*) and SEX*) or CHASTITY or CHASTE or VIRGIN* or CELIBA* or (SEX* and EDUCAT*)) and (HIV* or AIDS*) and ((control* or trial* or random* or blind* or (clinical and trial*) or (research and design) or compar* or evaluation) not (animals not human)) *Please see Ovid 2007 search for Global Health 2005‐2007. SIGLE was taken off line in 2005. | 683 |

| OVID 2007 ‐ includes AMED, BNI, HMIC, and Global Health | 2005‐2007 | AMED [2005‐], BNI [2005‐], HMIC [2005‐], and Global Health [2005‐], Searched February 15, 2007 Total Unique Records Retrieved: 118 #1(((ABSTINEN$ or ABSTAIN$ or postpon$ or DELAY$) and SEX$) or CHASTITY or CHASTE or VIRGIN$ or CELIBA$ or (SEX$ and EDUCAT$)).mp. [mp=ab, hw, ti, ot, bt] #2(HIV$ or AIDS$).mp. [mp=ab, hw, ti, ot, bt] #3((control$ or trial$ or random$ or blind$ or (clinical and trial$) or (research and design) or compar$ or evaluat$) not (animals not human)).mp. [mp=ab, hw, ti, ot, bt] #41 and 2 and 3 #5limit 4 to yr="2005 ‐ 2007" | 118 |

| PAIS 2007 | 2005‐2007 | 1972‐2005, see WebSpirs 2005 ‐ February 15, 2007 Total Unique Records Retrieved: 9 (ABSTINENCE OR ABSTAIN* OR CHASTITY OR CHASTE OR VIRGIN* OR CELIBA* OR (SEX* AND EDUCAT*) OR (SEX* AND (MARRIAGE* OR MARRIED))) and (hiv* or aids*) and (randomized controlled trial OR controlled clinical trial OR randomized controlled trials OR random allocation OR double‐blind method OR single‐blind method OR clinical trial OR clinical trials OR random* OR research design OR comparative study OR evaluation NOT (animals NOT human)) | 9 |

| PsycINFO | 1887‐2007 | 1887‐2005, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 1146 ((ABSTINEN* or ABSTAIN* or postpon* or DELAY*) and SEX*) or CHASTITY or CHASTE or VIRGIN* or CELIBA* or (SEX* and EDUCAT*)) and (HIV* or AIDS*) and ((control* or trial* or random* or blind* or (clinical and trial*) or (research and design) or compar* or evaluation) not (animals not human)) 2005‐2007, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 99 #1((((ABSTINEN$ or ABSTAIN$ or postpon$ or DELAY$) and SEX$) or CHASTITY or CHASTE or VIRGIN$ or CELIBA$ or (SEX$ and EDUCAT$)) and (HIV$ or AIDS$) and ((control$ or trial$ or random$ or blind$ or (clinical and trial$) or (research and design) or compar$ or evaluation) not (animals not human))).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts] #2limit 1 to yr="2005 ‐ 2007" | 1245 |

| PubMed | 1980‐2007 | 1980‐2005, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 5164 #1 Search HIV Infections[MeSH] OR HIV[MeSH] OR hiv[tw] OR hiv‐1*[tw] OR hiv‐2*[tw] OR hiv1[tw] OR hiv2[tw] OR hiv infect*[tw] OR human immunodeficiency virus[tw] OR human immunedeficiency virus[tw] OR human immuno‐deficiency virus[tw] OR human immune‐deficiency virus[tw] OR ((human immun*) AND (deficiency virus[tw])) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immunedeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR ((acquired immun*) AND (deficiency syndrome[tw])) OR "Sexually Transmitted Diseases, Viral"[MeSH:NoExp] #2 Search SEXUAL ABSTINENCE [MESH] #3 Search ABSTINENCE OR ABSTAIN* OR CHASTITY OR CHASTE OR VIRGIN* OR CELIBA* OR (SEX* AND EDUCAT*) OR (SEX* AND (MARRIAGE* OR MARRIED)) #4 Search #2 OR #3 #5 Search randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomized controlled trials [mh] OR random allocation [mh] OR double‐blind method [mh] OR single‐blind method [mh] OR clinical trial [pt] OR clinical trials [mh] OR ("clinical trial" [tw]) OR ((singl* [tw] OR doubl* [tw] OR trebl* [tw] OR tripl* [tw]) AND (mask* [tw] OR blind* [tw])) OR ( placebos [mh] OR placebo* [tw] OR random* [tw] OR research design [mh:noexp] OR comparative study [mh] OR evaluation studies [mh] OR follow‐up studies [mh] OR prospective studies [mh] OR control* [tw] OR prospectiv* [tw] OR volunteer* [tw]) NOT (animals [mh] NOT human [mh]) #6Search #1 AND #4 AND #5 Field: All Fields, Limits: Publication Date from 1980 to 2005 2005‐2007, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 595 #1 Search HIV Infections[MeSH] OR HIV[MeSH] OR hiv[tw] OR hiv‐1*[tw] OR hiv‐2*[tw] OR hiv1[tw] OR hiv2[tw] OR hiv infect*[tw] OR human immunodeficiency virus[tw] OR human immunedeficiency virus[tw] OR human immuno‐deficiency virus[tw] OR human immune‐deficiency virus[tw] OR ((human immun*) AND (deficiency virus[tw])) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immunedeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR ((acquired immun*) AND (deficiency syndrome[tw])) OR "Sexually Transmitted Diseases, Viral"[MeSH:NoExp] Limits: Publication Date from 2005 to 2007 #2 Search SEXUAL ABSTINENCE [MESH] Limits: Publication Date from 2005 to 2007 #3 Search ABSTINENCE OR ABSTAIN* OR CHASTITY OR CHASTE OR VIRGIN* OR CELIBA* OR (SEX* AND EDUCAT*) OR (SEX* AND (MARRIAGE* OR MARRIED)) Limits: Publication Date from 2005 to 2007 #4 Search #2 OR #3 Limits: Publication Date from 2005 to 2007 #5 Search randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomized controlled trials [mh] OR random allocation [mh] OR double‐blind method [mh] OR single‐blind method [mh] OR clinical trial [pt] OR clinical trials [mh] OR ("clinical trial" [tw]) OR ((singl* [tw] OR doubl* [tw] OR trebl* [tw] OR tripl* [tw]) AND (mask* [tw] OR blind* [tw])) OR ( placebos [mh] OR placebo* [tw] OR random* [tw] OR research design [mh:noexp] OR comparative study [mh] OR evaluation studies [mh] OR follow‐up studies [mh] OR prospective studies [mh] OR control* [tw] OR prospectiv* [tw] OR volunteer* [tw]) NOT (animals [mh] NOT human [mh]) Limits: Publication Date from 2005 to 2007 #6 Search #1 AND #4 AND #5 Limits: Publication Date from 2005 to 2007 | 5759 |

| SciSearch (Web of Knowledge): Biomedical abstracts | 1974‐2007 | 1974‐2005, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 21 #1 topic=(((ABSTINEN* OR ABSTAIN*) and SEX*) OR CHASTITY OR CHASTE OR VIRGIN* OR CELIBA* OR (SEX* AND EDUCAT*)) Database=Web of Science; Timespan=Latest 5 Years #2 topic=(HIV* OR AIDS*) Database=Web of Science; Timespan=Latest 5 Years #3 topic=((randomized SAME controlled) OR control* OR trial* OR random* OR double‐blind* OR single‐blind* OR (clinical AND trial*) OR (research SAME design) OR comparative OR evaluation NOT (animals NOT human)) Database=Web of Science; Timespan=Latest 5 Years #4 topic=((((ABSTINEN* OR ABSTAIN*) and SEX*) OR CHASTITY OR CHASTE OR VIRGIN* OR CELIBA* OR (SEX* AND EDUCAT*)) and (HIV* OR AIDS*) and ((randomized SAME controlled) OR control* OR trial* OR random* OR double‐blind* OR single‐blind* OR (clinical AND trial*) OR (research SAME design) OR comparative OR evaluation NOT (animals NOT human))) 2005‐2007, Total Unique Records Retrieved: 66 #1 topic=(((ABSTINEN* OR ABSTAIN*) and SEX*) OR CHASTITY OR CHASTE OR VIRGIN* OR CELIBA* OR (SEX* AND EDUCAT*)) Database=Web of Science; Timespan=Latest 5 Years #2 topic=(HIV* OR AIDS*) Database=Web of Science; Timespan=Latest 5 Years #3 topic=((randomized SAME controlled) OR control* OR trial* OR random* OR double‐blind* OR single‐blind* OR (clinical AND trial*) OR (research SAME design) OR comparative OR evaluation NOT (animals NOT human)) Database=Web of Science; Timespan=Latest 5 Years #4 topic=((((ABSTINEN* OR ABSTAIN*) and SEX*) OR CHASTITY OR CHASTE OR VIRGIN* OR CELIBA* OR (SEX* AND EDUCAT*)) and (HIV* OR AIDS*) and ((randomized SAME controlled) OR control* OR trial* OR random* OR double‐blind* OR single‐blind* OR (clinical AND trial*) OR (research SAME design) OR comparative OR evaluation NOT (animals NOT human))) Database=Web of Science; Timespan=Latest 5 Years Examined records from 2005‐2007. | 87 |

| TROPHI | Inception‐2007 | Inception ‐ 2005, Total Records Retrieved: 176 Search terms: abstinence AND sex AND HIV, sex and (postpone or abstain), postpone AND sex, delay AND sex, chastity, virgin, sex education AND HIV, HIV OR AIDS. Examined all records. 2005‐2007, Total Records Retrieved: 200 Search terms: abstinence and sex, virgin, postpone sex, abstain, HIV. Examined all records from 2005‐2007. | 376 |

| WEBSPIRS 2005 ‐ includes AMED, BNI, RCN Journals, HMIC, PAIS, and SERFILE | 1972‐2005 | AMED [1985‐], BNI [1985‐], RCN [1985‐1996], HMIC [1983‐], SERFILE [Inception‐], and PAIS [1972‐], Searched May 28, 2005 Total Unique Records Retrieved: 94 (((ABSTINEN* or ABSTAIN* or postpon* or DELAY*) and SEX*) or CHASTITY or CHASTE or VIRGIN* or CELIBA* or (SEX* and EDUCAT*)) and (HIV* or AIDS*) and ((control* or trial* or random* or blind* or (clinical and trial*) or (research and design) or compar* or evaluation) not (animals not human)) *For 2005‐2007 searches of AMED, BNI, and HMIC, see the search of OVID. For 2005‐2007 searches of PAIS, see PAIS. RCN was searchable via BNI in 2007. | 94 |

Electronic Databases We searched the following electronic databases, ending February 15, 2007: 1. ADOLEC (Inception‐2007) 2. AIDSLINE (1980‐2007) 3. AMED (1985‐2007) 4. ASSIA (1987‐2007) 5. BiblioMap (1887‐2007) 6. BIOSIS (1969‐2007) 7. BNI (1985‐2007) 8. Catalog of US Government Publications (1976‐2007) 9. CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) (1980‐2007) 10. CHID (1985‐2005; went offline in 2005) 11. CINAHL (1982‐2007) 12. DARE (1991‐2007) 13. Dissertation Abstracts International (1997‐2007) 14. EMBASE (1974‐2007) 15. ERIC (1991‐2007) 16. EurasiaHealth Knowledge Multilingual Library (Inception‐2007) 17. Global Health Abstracts (1973‐2007) 18. HealthPromis (1997‐2005; went offline in 2005) 19. HMIC (1983‐2007) 20. PAIS (1972‐2007) 21. Political Science Abstracts (1975‐2007) 22. PsycINFO (1887‐2007) 23. PubMed (1980‐2007) 24. RCN (1985‐1996; updating ended in 1996) 25. SCISEARCH (Web of Knowledge) (1974‐2007) 26. SERFILE (Inception ‐ 2005; inaccessible in 2007) 27. SIGLE (1980‐2005; went offline in 2005) 28. Social Services Abstracts (1979‐2007) 29. Sociological Abstracts (1963‐2007) 30. TRoPHI (Inception‐2007)

Other relevant libraries of international agencies, especially those concerned with the prevention of HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS, USAID, WHO, UNFPA, World Bank, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) were searched. We made additional efforts to identify and acquire unpublished literature.

Hand‐Searching We hand‐searched various conference proceedings from 2000 onwards to identify unpublished reports. These included proceedings from the International AIDS Conference, the Conferences on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, the US National HIV Prevention Conferences, the Abstinence Education Evaluation Conference, and the International Society of STD Research (ISSTDR).

Personal communication We contacted leading experts in the field of abstinence‐based programs to solicit potentially relevant unpublished papers, ongoing research, and suggestions for other contacts.

Cross References The reference lists of related reviews and all articles obtained were examined for additional citations.

Search Terms We searched with combinations of the following terms. MeSH terms (eg "Sexual Abstinence") were also identified and included. We did not include country names or program names, as they may not be specified in searchable headings.

Intervention terms: abstinence, abstain, chastity, chaste, virgin, celibacy, celibate, sex education, marriage, delay, postpone.

Study terms: randomized controlled trial, controlled clinical trial, random allocation, double‐blind, single‐blind, clinical trial, mask, comparative study, control, pre‐post controlled designs, comparison group, cohort study, comparative study, evaluation study, feasibility study, follow up studies.

HIV terms: HIV Infections, HIV, HIV‐1, HIV‐2, human immunodeficiency virus, human immunedeficiency virus, human immuno‐deficiency virus, human immune‐deficiency virus, AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, acquired immunedeficiency syndrome, acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome, acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome, sexually transmitted diseases.

PUBMED SAMPLE SEARCH STRATEGY #1 Search HIV Infections[MeSH] OR HIV[MeSH] OR hiv[tw] OR hiv‐1*[tw] OR hiv‐2*[tw] OR hiv1[tw] OR hiv2[tw] OR hiv infect*[tw] OR human immunodeficiency virus[tw] OR human immunedeficiency virus[tw] OR human immuno‐deficiency virus[tw] OR human immune‐deficiency virus[tw] OR ((human immun*) AND (deficiency virus[tw])) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immunedeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR ((acquired immun*) AND (deficiency syndrome[tw])) OR "Sexually Transmitted Diseases, Viral"[MeSH:NoExp] Limits: Publication Date from 1980 to 2007 #2 Search SEXUAL ABSTINENCE [MESH] Limits: Publication Date from 1980 to 2007 #3 Search ABSTINENCE OR ABSTAIN* OR CHASTITY OR CHASTE OR VIRGIN* OR CELIBA* OR (SEX* AND EDUCAT*) OR (SEX* AND (MARRIAGE* OR MARRIED)) Limits: Publication Date from 1980 to 2007 #4 Search #2 OR #3 Limits: Publication Date from 1980 to 2007 #5 Search randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomized controlled trials [mh] OR random allocation [mh] OR double‐blind method [mh] OR single‐blind method [mh] OR clinical trial [pt] OR clinical trials [mh] OR ("clinical trial" [tw]) OR ((singl* [tw] OR doubl* [tw] OR trebl* [tw] OR tripl* [tw]) AND (mask* [tw] OR blind* [tw])) OR ( placebos [mh] OR placebo* [tw] OR random* [tw] OR research design [mh:noexp] OR comparative study [mh] OR evaluation studies [mh] OR follow‐up studies [mh] OR prospective studies [mh] OR control* [tw] OR prospectiv* [tw] OR volunteer* [tw]) NOT (animals [mh] NOT human [mh]) Limits: Publication Date from 1980 to 2007 #6 Search #1 AND #4 AND #5 Limits: Publication Date from 1980 to 2007

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies All reviewers independently examined citations reviewed by the search strategy. KU obtained full‐text articles of potentially relevant papers. All reviewers independently assessed their eligibility using an eligibility form based on pre‐specified inclusion criteria. Reasons for excluding potentially relevant trials are specified in the "Characteristics of Excluded Studies." We contacted the authors for clarification when necessary. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and, if necessary, referral to the Cochrane HIV/AIDS Review Group.

Data extraction and management All reviewers independently extracted data on study design, participants, interventions, outcomes and methodological quality using pre‐designed data collection forms. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and referral to the Cochrane HIV/AIDS Review Group if necessary.

The extracted data included the following measures: citation, study design, methodological criteria, inclusion and exclusion criteria, comparison group intervention, participant characteristics, trial setting, theoretical basis for intervention, elements of intervention, all relevant outcome measures, and results. We expected the trial settings to vary widely (eg schools, clinics, prisons, community centers, and churches), and examined this carefully when considering the heterogeneity of our data set. We also examined any process or cost‐effectiveness data reported, including training, monitoring, acceptability, costs, and sustainability.

Where reports were uncertain or included summary measures, authors were contacted for clarification. We noted any data that was consistently underreported, and highlighted this deficit along with future research needs in the discussion.

Assessment of methodological quality of included studies Depending on study design, we evaluated the following methodological components, since there is evidence that these may be associated with biased estimates of effects. 1. Similarity of the intervention and control groups (whether groups were treated equally except for the intervention). 2. Method of generation of the randomization sequence. 3. Generation of allocation concealment. 4. Blinding (participants, intervention staff, and outcome assessors). 5. Intention‐to‐treat analysis. 6. Loss to follow up. In our results and discussion sections, we highlight attrition as a particular limitation of any studies with a total dropout exceeding one third of baseline enrolment.

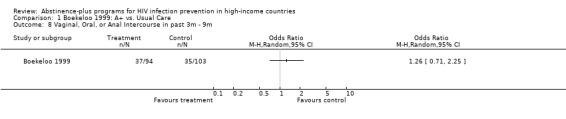

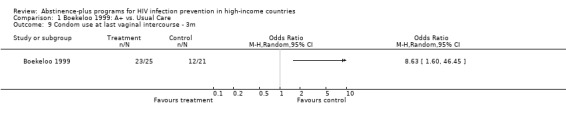

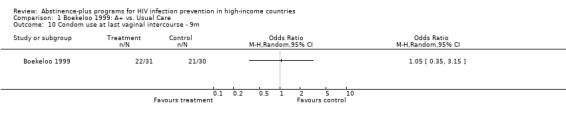

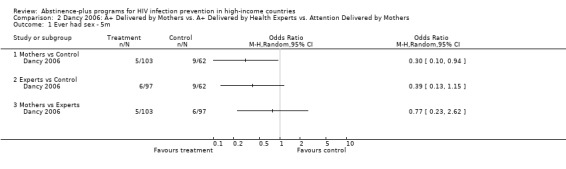

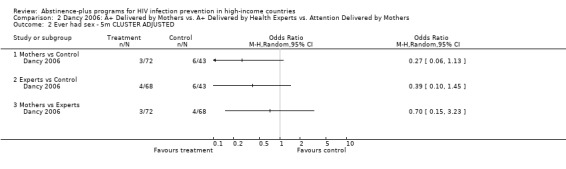

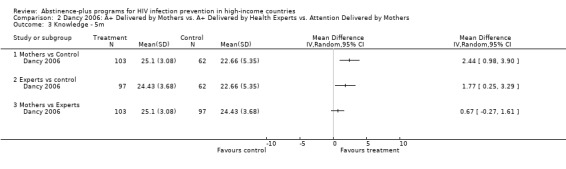

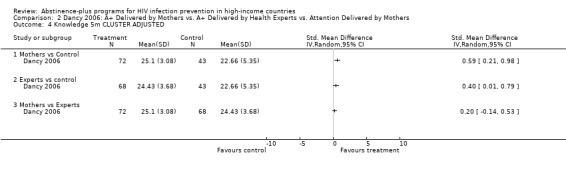

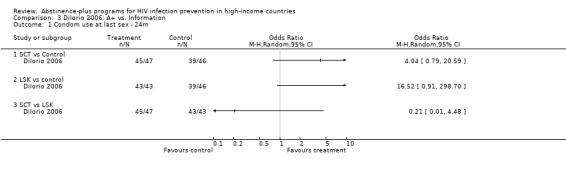

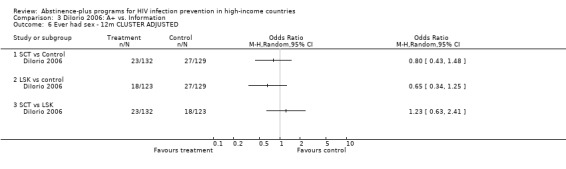

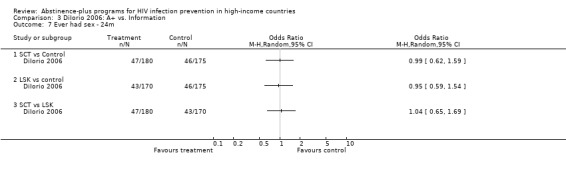

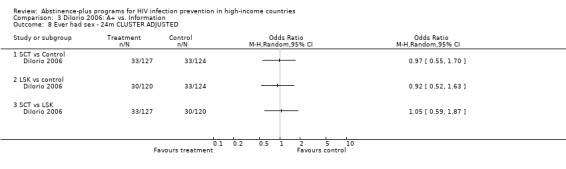

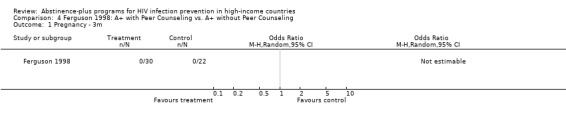

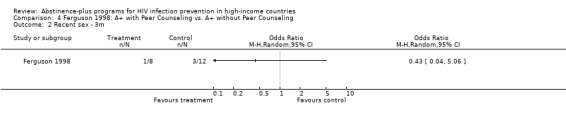

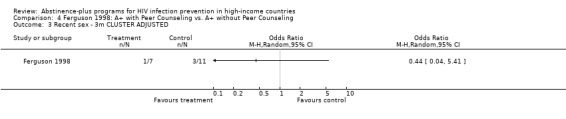

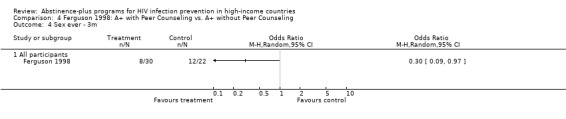

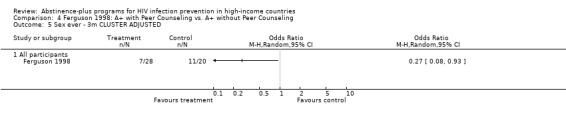

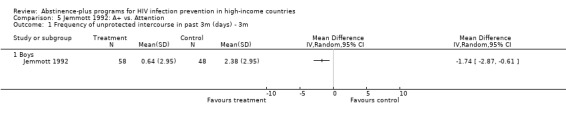

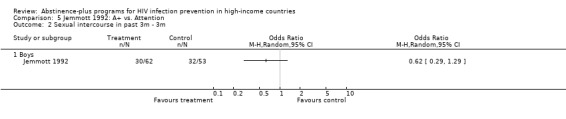

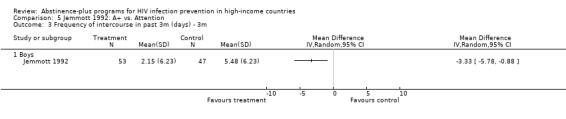

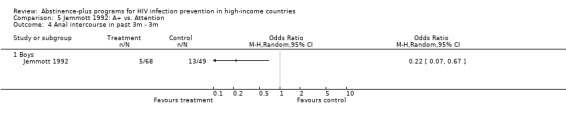

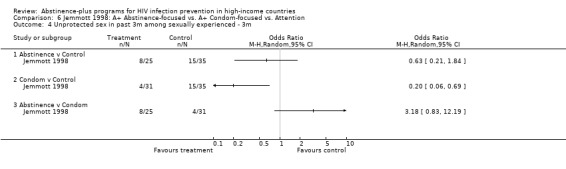

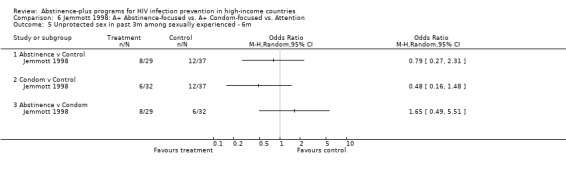

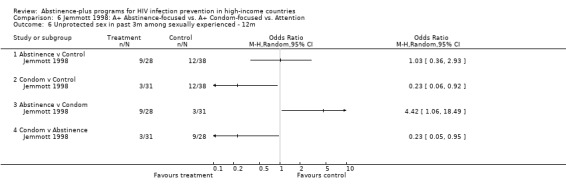

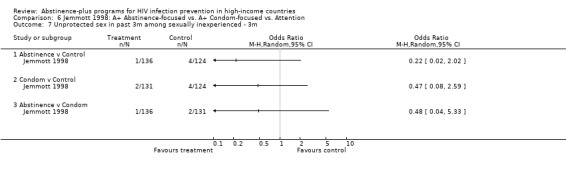

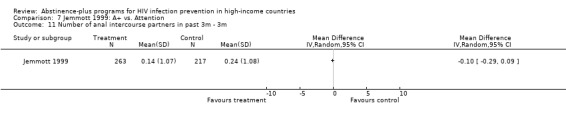

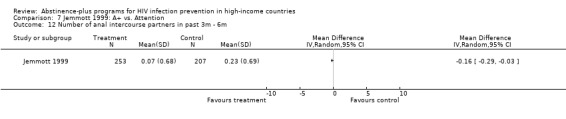

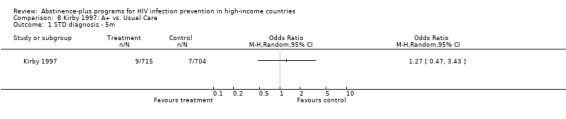

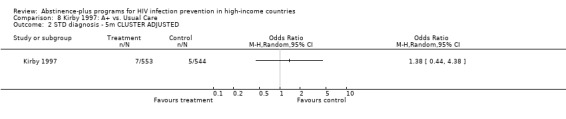

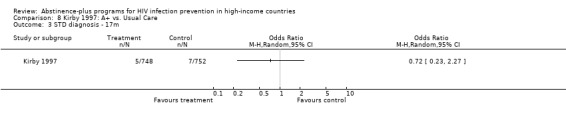

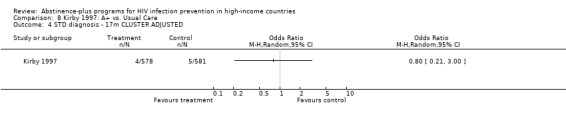

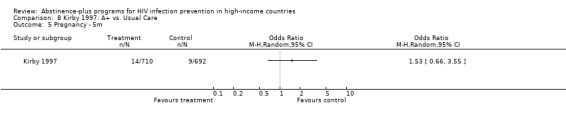

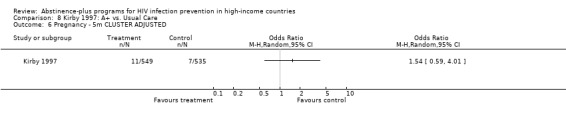

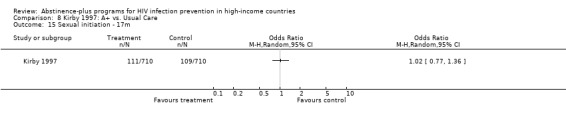

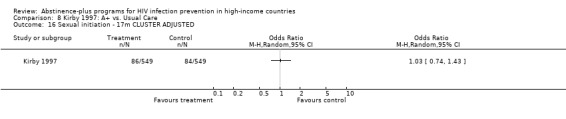

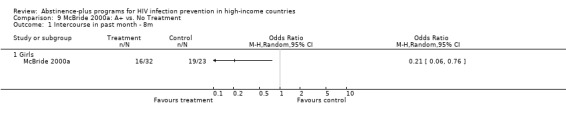

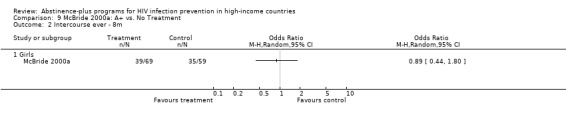

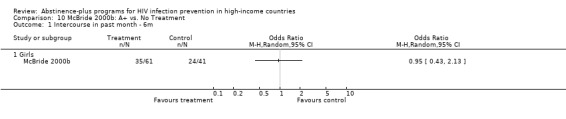

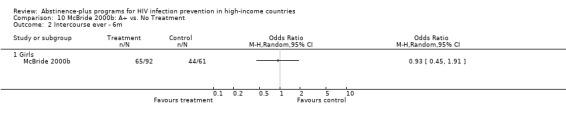

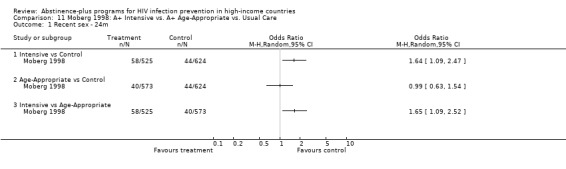

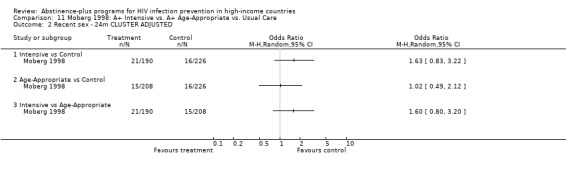

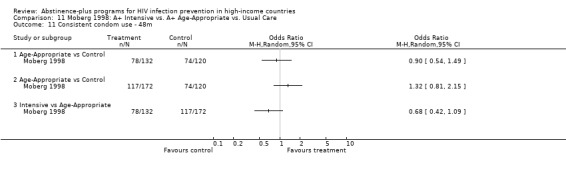

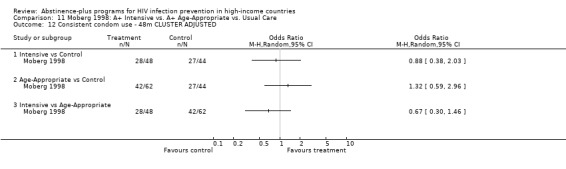

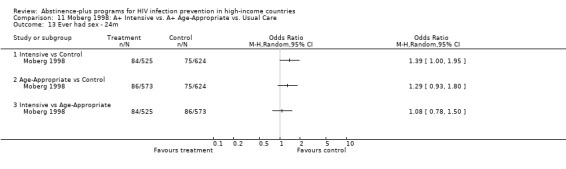

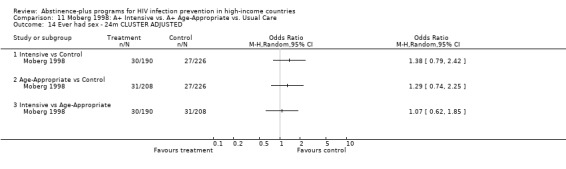

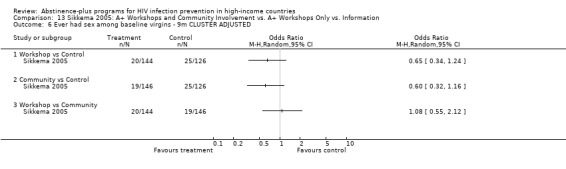

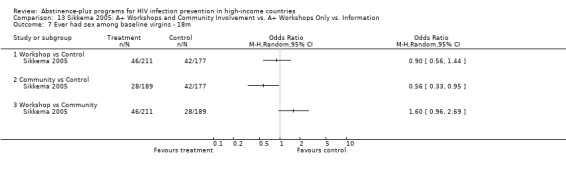

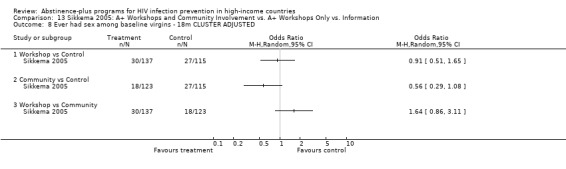

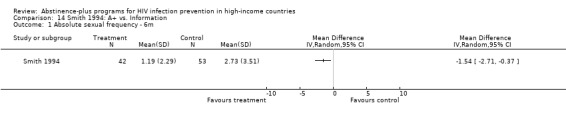

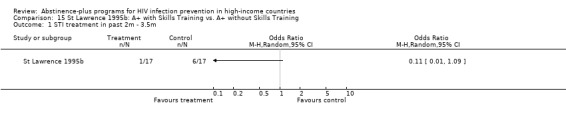

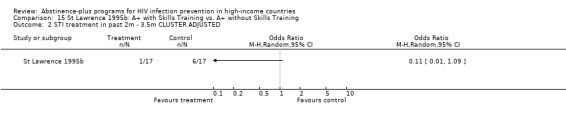

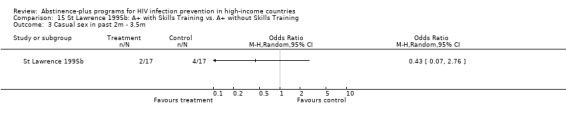

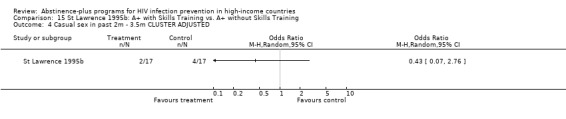

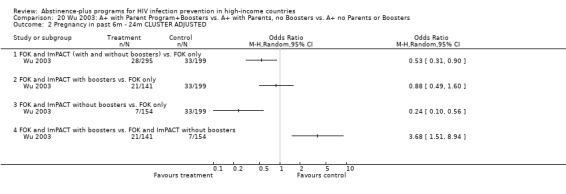

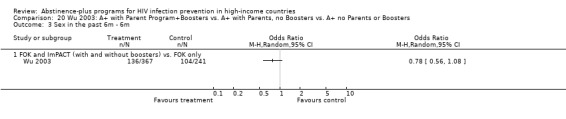

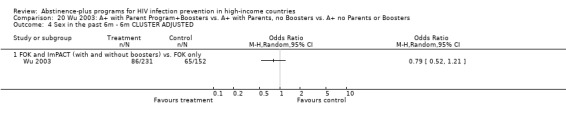

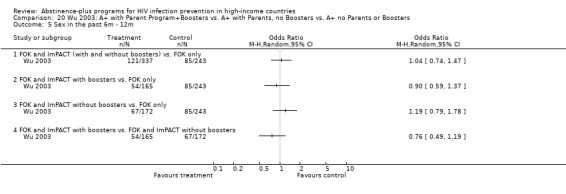

Measures of treatment effect To investigate the feasibility of a meta‐analysis, all eligible studies were summarized in RevMan to the fullest extent possible. All reviewers assisted in abstracting the data, with KU entering all data into RevMan and DO and PM checking all entries. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. A narrative synthesis was provided for all results, but we determined that a statistical meta‐analysis was not appropriate for this review due to differences in program and evaluation design, underreporting of key data, and inability to retrieve unpublished or missing data from authors. Had the studies been comparable and more completely reported, our meta‐analysis would have measured the weighted average effect size for each outcome measure, weighted mean differences (for continuous outcomes), odds ratios of effects (for dichotomous outcomes), and 95% confidence intervals. Odds ratios less than one would have expressed a protective intervention effect.

Unit of analysis issues Studies with multiple treatment groups A meta‐analysis was not conducted for this version of the review. However, had meta‐analysis been possible, we would have dealt with multiple treatment groups in the following way: When studies had more than 2 treatment groups, we planned to accept only 2 groups for the meta‐analysis. In keeping with procedures used by the US HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis project (Johnson 2002), we planned to take the arm with the greatest or most intense exposure (as identified by the trialist), compared to the arm with the least or least intense exposure, thereby giving each study the most favorable chance of yielding significant program effects. When different trial arms emphasized sexual abstinence to differing extents, we would have accepted the arm that emphasized abstinence the most, compared to the arm that emphasized abstinence the least.

Cross‐over trials We did not anticipate dealing with these trials in the review, and no cross‐over trials were recovered by the search. If we had identified any studies using this design, we would have analyzed only the follow‐up data from the period before the cross over.

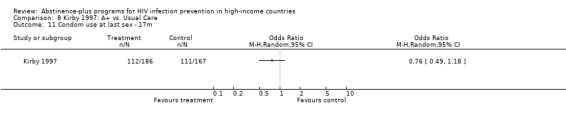

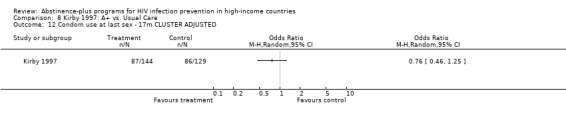

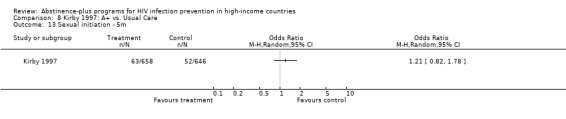

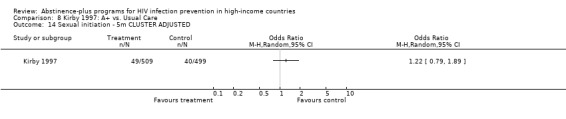

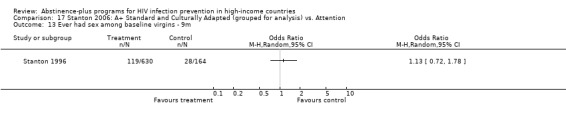

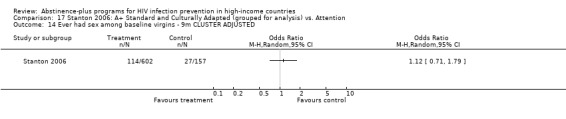

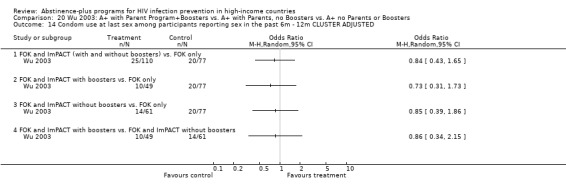

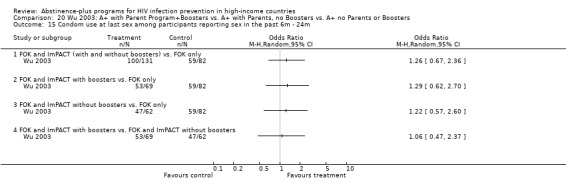

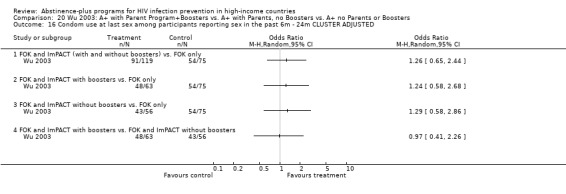

Cluster randomized trials When studies use cluster randomization, analyzing the data at the level of the individual participant has two implications. First, p‐values may be artificially small, suggesting significant effects where none occurred (Higgins 2005). Second, the confidence intervals for these results may appear artificially narrow, which would cause the studies to receive disproportionately more weight in the context of a meta‐analysis (Donner 2002, Johnson 2002). The second concern was unimportant for this version of the review because no meta‐analysis was conducted. However, the first remained relevant because wherever possible, we reported the individual study results as calculated in RevMan.

In order to analyze cluster‐randomized trials appropriately in RevMan, we sought statistical guidance from the Cochrane HIV/AIDS Review Group and a number of external statistical experts. Before entering the results of cluster‐randomized studies into RevMan, we transformed outcome data according to the procedure in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2005, supported in Adams 2004), dividing the number of events and number of participants by the design effect [1 + (1 ‐ m) * r]. We used the details provided by each study (total n and number of clusters) to calculate the average cluster size (m). After a sensitivity analysis, we decided upon consultation with the review group to report results using the intra‐class correlation coefficients (r) recommended in Johnson 2002. These were ICC=0.015 for school‐based studies and ICC=0.005 for community‐based studies (regardless of cluster size); these values were calculated respectively from school‐based studies of youth smoking behavior and community‐based studies of HIV prevention for men who have sex with men (Johnson 2002). Insufficient data were available for us to estimate a reliable ICC from the included studies.

Even with extensive statistical guidance, we acknowledge that the applicability of external values to this review is somewhat uncertain. For greater transparency, we report the results of cluster‐randomized trials analyzed both before and after controlling for clustering.

Dealing with missing data Missing data arose from two sources: participant attrition and missing statistics.

Attrition We preferred to accept studies with intention‐to‐treat analyses, which minimize attrition bias by imputing data for participants who drop out of the trial (Hollis 1999). However, we also accepted studies that used complete case analyses, but contacted authors for missing data. If a meta‐analysis had been possible, we would have conducted sensitivity analyses to investigate attrition as a source of heterogeneity and possible bias.

Missing statistics Where statistics were missing (eg numbers of participants per group, attrition rates, means and standard deviations, or percentages), we contacted primary study authors to supply the information. Where the information was unavailable due to data loss or non‐response, we reported the available results as stated in the trial report.

Assessment of heterogeneity If a meta‐analysis had been possible, we would have assessed heterogeneity using the chi square test of heterogeneity, visual inspection of the data, and the I2 statistic (Higgins 2002). The I2statistic determines the percentage of variability that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error, where a value greater than 50% suggests moderate heterogeneity. If any of these methods indicated heterogeneity, we would have investigated possible explanations, including clinical and methodological characteristics. Even when tests for heterogeneity were non‐significant, we planned to conduct subgroup analyses to explore other potential moderators.

Assessment of reporting biases If a meta‐analysis had been possible, we would have used funnel plots (plotting effect size against standard error) to detect potential bias. Additional analyses may have included the planned Egger regression approach with a weight‐function model. Asymmetry can be due to publication bias, but it can also arise from clinical and methodological heterogeneity. In the event that a relationship had been found, these sources of heterogeneity would also have been examined as possible explanations (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis If a meta‐analysis had been possible, we would have considered conducting analyses according to both fixed effects and random effects models. The random effects model would have been used where there was indication of heterogeneity and the source of such heterogeneity could not be explained. The random effects model would also have been used for analyses incorporating small numbers of studies, for which tests of heterogeneity may be underpowered. If there were no source of heterogeneity beyond differences in the observed covariates, we would have conduct both fixed effects and random effects analyses and investigated differences between the two procedures.

The narrative synthesis was conducted according to the following methods. First, we entered each individual study in RevMan. Secondly, we prepared the supplemental Charts of Effects appended to this review (see Appendix A). These charts are organized by outcome, and each chart shows the effects of individual studies according to RevMan analyses (where possible) or as reported in the primary study. The charts also integrate key methodological features of each study (eg control group, attrition), along with each study's definition of the outcome of interest (eg condom use was variously defined as condom use at last sex among sexually experienced participants, or condom use in the last month among sexually active participants). The charts were then explained in text format for the description of studies and results.

Sub‐group analyses If we had conducted a meta‐analysis, we would have stratified our analysis by intervention setting (eg school, clinic) and by participants' age, country, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Subgroup analyses would only have been conducted if data allowed, with the knowledge that using a number of subgroups can lead to statistically misleading conclusions.

Sensitivity analysis If we had conducted a meta‐analysis, we would have performed separate analyses for studies using complete case, per‐protocol, and intention‐to‐treat methods, with a sensitivity analysis to investigate disparities among the three groups.

Results

Description of studies

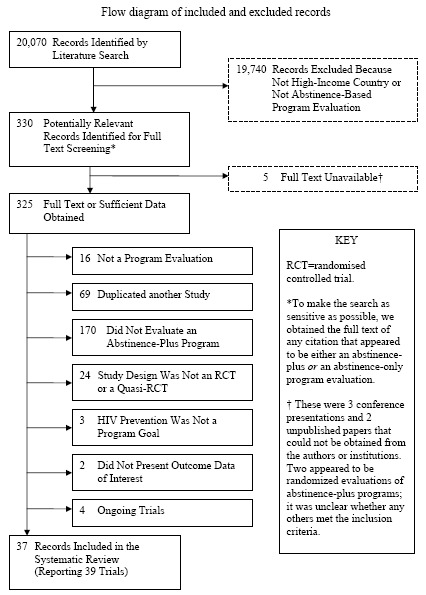

See Figure 1.

1.

QUOROM Chart.

A total of 20070 citations were assessed for inclusion (of these, 19892 were recovered from electronic database searches ending February 2007, 99 were from hand‐searching, 17 were from personal contacts, and 62 were from cross‐referencing). After screening, 330 papers were deemed potentially relevant evaluation studies. Full text copies (or sufficient information) for 235 of these citations were obtained.

Of the 5 papers we could not obtain, 2 were conference abstracts of unclear relevance whose authors could not be located. One was an in‐press paper of unclear relevance that could not be obtained from the authors. Two appeared to be recently completed abstinence‐plus program trials, but reports were not available and could not be obtained from the trialists.

Of the 325 papers for which the full text (or sufficient study information) was obtained, 288 were excluded for the following reasons: 16 were not program evaluations, 69 duplicated another paper, 170 did not evaluate an abstinence‐plus intervention, 24 did not meet the criteria for study design, 3 evaluated abstinence‐plus interventions that did not list HIV prevention as a program goal, 2 did not present outcome data of interest, and 4 were ongoing or recently completed trials for which full reports were not yet available.

After these studies were excluded, analyses were limited to 37 separate papers (along with the papers that duplicated these reports), comprising 39 separate evaluations assessing the effects of abstinence‐plus programs. Two reports described 2 evaluations (Kennedy 2000a, Kennedy 2000b, McBride 2000a, McBride 2000b). Additionally, one trial (Philliber 2001) reported a 12‐site evaluation study but grouped the 12 sites for analysis, so this represents one evaluation.

Included Studies Detailed information about individual studies may be found in the Table of Included Studies.

Design Five of the included studies were quasi‐randomized controlled trials. Methods of allocation were reported in four studies, which used alternation (Danielson 1990), tossing a coin (Ferguson 1998), and assignment by even or odd birth date (McBride 2000a, McBride 2000b). We included these quasi‐randomized designs after determining that the randomization sequences, as described, were unlikely to lead to systematic bias between the treatment arms. Although baseline differences reached significance in two of these studies (Danielson 1990 and McBride 2000b), all four of these quasi‐randomized controlled trials controlled for baseline values in analyses.

The fifth quasi‐RCT (Moberg 1998) was a three‐arm trial, with arms receiving a one‐year intervention, a three‐year intervention, and usual care. This study used a stratified randomization sequence based on whether the included schools could feasibly deliver a one‐year or a three‐year program. Within each of those two categories, schools were then randomly assigned to deliver either the intervention or usual care. Specific procedures for random assignment within these categories were not reported.

The remaining 34 evaluations were randomized controlled trials, although method of randomization was rarely reported (see Methodological quality of included studies).

Twenty‐one trials randomized clusters of participants: units of randomization included schools (Aarons 2000, Coyle 2001, Coyle 2004, Coyle 2006, Markham 2006, Moberg 1998, Wright 1997), classrooms (Kirby 1997, O'Donnell 2002), school districts (Weeks 1997), neighborhoods or communities (Dancy 2006, Ferguson 1998, Sikkema 2005, Wu 2003), community centers (DiIorio 2006, DiIorio 2007, Jemmott 2004), friendship groups (Stanton 1996), recruitment groups (Stanton 2006), and cohorts of 6‐10 participants (St Lawrence 1995b, St Lawrence 2002). The remaining 18 trials randomized individuals. Cluster‐randomization was commonly driven by the need to minimize potential contamination, along with the convenience of schools and other clustered units for program delivery.

Control groups for the evaluations varied as follows:

Controls in ten trials received usual care (Aarons 2000, Boekeloo 1999, Coyle 2004, Coyle 2006, Kirby 1997, Markham 2006, Moberg 1998, Philliber 2001, Weeks 1997, Wright 1997). Usual care consisted of the HIV/AIDS prevention services or sex education normally provided by the school system or community setting. These services may have included no treatment, abstinence‐only programs, safer‐sex interventions, condom promotion programs, or other abstinence‐plus programs, but very few details were provided to gauge what services usual care control groups actually received. This prevented a quantitative synthesis of trials with usual care controls.

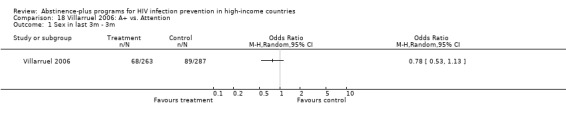

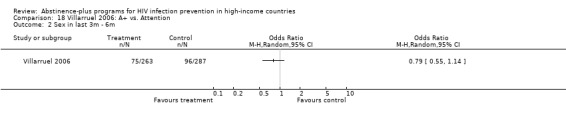

Seven trials used a non‐intervention (no‐treatment) control group (Danella 2000, Danielson 1990, Hernandez 1990, Kennedy 2000a, Kennedy 2000b, McBride 2000a, McBride 2000b); in some cases the intervention was offered to the control group after completion of treatment.

Eleven trials used attention control groups, in which the control participants are exposed to the same types of program activities and exposure but with a different thematic focus (Dancy 2006, DiIorio 2007, Hewitt 1998, Jemmott 1992, Jemmott 1998, Jemmott 1999, Jemmott 2004, St Lawrence 1999, Stanton 2000, Stanton 2006, Villarruel 2006). Four of these trials involved the same program developers (Hewitt 1998, Jemmott 1992, Jemmott 1998, Jemmott 1999). Attention control groups focused on concepts such as career planning and career opportunities (Jemmott 1992, Stanton 2000), general health (Dancy 2006, Hewitt 1998, Jemmott 1998, Jemmott 1999, Jemmott 2004, Villarruel 2006), anger management (St Lawrence 1999), and environmental education (Stanton 2006).

In four trials (Coyle 2001, DiIorio 2006, Sikkema 2005, Smith 1994), controls received an educational program, which we designated as an "information" control group. These interventions were generally brief and provided factual information about HIV and its transmission.

Fifteen trials compared several different versions of an abstinence‐plus intervention, sometimes in addition to a usual care, non‐intervention, attention control, or information control (Dancy 2006, DiIorio 2006, Ferguson 1998, Hewitt 1998, Jemmott 1998, Moberg 1998, O'Donnell 2002, Sikkema 2005, St Lawrence 1995a, St Lawrence 1995b, St Lawrence 2002, Stanton 1996, Stanton 2006, Weeks 1997, Wu 2003).

Hernandez 1990 was the only trial to compare identical formats of an abstinence‐plus program, an abstinence‐only program, and a safer‐sex program, along with a non‐intervention control. In a similar trial, Jemmott 1998 compared an abstinence‐plus program with a heavy emphasis on abstinence, an abstinence‐plus program with a heavy emphasis on condom skills, and an attention control focusing on general health.

Ten evaluations involved more than two treatment arms (Dancy 2006, DiIorio 2006, Hernandez 1990, Hewitt 1998, Jemmott 1998, Moberg 1998, Sikkema 2005, St Lawrence 2002, Weeks 1997, Wu 2003). Another evaluation evolved into a three‐arm design based on dosage when the host school system decided to expand the experimental program halfway through the evaluation; analyses were provided both by original assignment and by dosage received (0, 1, or 2 program years) (O'Donnell 2002).

Sample Size Together, the 39 studies enrolled approximately 37724 participants at baseline, with a median baseline enrolment of 535. Sample size at baseline ranged from 34 (St Lawrence 1995b) to 4512 (Wright 1997); one trial did not report the specific number enrolled at baseline, but this was approximated from the given attrition rates and number analyzed (Kirby 1997). Nine trials reported using a power calculation (DiIorio 2006, DiIorio 2007, Ferguson 1998, Jemmott 1998, Kennedy 2000a, Kennedy 2000b, Moberg 1998) or reported the statistical power attained by the sample size for each outcome at follow‐up (McBride 2000a, McBride 2000b); while it is likely that a majority of remaining trials used power calculations as well, these calculations were not reported.

After attrition at each study's longest follow‐up, the analyses reported in this review encompass approximately 25796 participants (with values imputed for trials using intention‐to‐treat analyses), for an overall attrition of 31.6%. This figure does not account for non‐response or under‐utilization of any specific outcome measure.

Setting Despite our international search for trials, all 39 studies took place in North America; 37 studies took place in the contiguous United States, 1 multi‐site study involved four Canadian provinces, and 1 trial took place in the Bahamas. US evaluation sites varied and are described in the Table of Included Studies; most trials were conducted in coastal areas. Of the trials that used multi‐site designs, all grouped participants from different sites together for analysis, and only Coyle 2001 reported group‐by‐location analyses. The majority of evaluations took place in urban settings; only one trial took place in an exclusively rural area (Stanton 2006).

The immediate program setting was usually a school or community center (32 trials). Other programs took place at health centers (Danielson 1990, St Lawrence 1995a), doctors' offices (Boekeloo 1999), a residential drug treatment center (St Lawrence 1995b, St Lawrence 2002), a juvenile reformatory (St Lawrence 1999), and family homes (Stanton 1996, Wu 2003).

Participants All participants were adolescents or young adults. Mean ages in individual trials ranged from 11.5 years (Coyle 2004) to 19.25 years (Hernandez 1990); the median of these mean ages was approximately 14.4 years. The majority of programs targeted pre‐secondary‐school youth; it has been suggested that programs promoting sexual abstinence may be more effective before participants make their sexual debut (DiClemente 1998). Specific data on participant inclusion criteria and target ages are provided in the Table of Included Studies.

Twenty‐nine trials enrolled primarily minority participants (Aarons 2000, Boekeloo 1999, Coyle 2001, Coyle 2004, Coyle 2006, Dancy 2006, DiIorio 2006, Ferguson 1998, Hewitt 1998, Jemmott 1992, Jemmott 1998, Jemmott 1999, Kennedy 2000b, Kennedy 2000a, Kirby 1997, Markham 2006, O'Donnell 2002, Philliber 2001, Sikkema 2005, Smith 1994, St Lawrence 1995a, St Lawrence 1999, Stanton 1996, Villarruel 2006, Weeks 1997, Wu 2003, Jemmott 2004, DiIorio 2007, Stanton 2000), of which 12 enrolled samples that were 97‐100% African‐American (Dancy 2006, DiIorio 2006, Ferguson 1998, Hewitt 1998, Jemmott 1992, Jemmott 1998, Jemmott 1999, St Lawrence 1995a, Stanton 1996, Wu 2003, DiIorio 2007, Stanton 2000). An additional study was conducted among participants of Bahamian ethnicity (Danella 2000). Twenty trials reported any information about participants' socioeconomic status (Aarons 2000, Coyle 2001, Coyle 2004, DiIorio 2006, DiIorio 2007, Ferguson 1998, Jemmott 1992, Jemmott 1998, Jemmott 1999, Markham 2006, O'Donnell 2002, Philliber 2001, Sikkema 2005, Smith 1994, St Lawrence 1995a, Stanton 1996, Wu 2003, Dancy 2006, Stanton 2000, Weeks 1997), of which 18 indicated that participants were of lower SES than the general population (Aarons 2000, DiIorio 2006, DiIorio 2007, Ferguson 1998, Jemmott 1992, Jemmott 1998, Jemmott 1999, Markham 2006, O'Donnell 2002, Philliber 2001, Sikkema 2005, Smith 1994, St Lawrence 1995a, Stanton 1996, Wu 2003, Dancy 2006, Stanton 2000, Weeks 1997). Indicators of SES included uptake of free/reduced lunch plans, neighborhood, receipt of Medicaid or public assistance, mothers' education, and living in a home with a working adult.

Thirty trials included both male and female participants. Four studies enrolled males only (Danielson 1990, DiIorio 2007, Jemmott 1992, St Lawrence 1999), and five studies enrolled females only (Dancy 2006, Danella 2000, Ferguson 1998, McBride 2000a, McBride 2000b).

Since participants in most studies were younger than the legal age of consent, parental consent procedures were relevant ethical concerns. Hernandez 1990 was limited to participants over the age of 18 and so did not require parental consent. Twenty‐eight studies required active parental consent for participation in the intervention and participation in data collection. Two studies required active parental consent, but only for participants under the age of 14 years (McBride 2000a, McBride 2000b). In three studies, the experimental interventions were delivered as part of a school curriculum; however, these three studies required active parental consent for participation in data collection procedures (Coyle 2004, Kirby 1997, and Moberg 1998). One study used passive consent procedures for participation in both the intervention and in data collection (Weeks 1997). Two evaluations were part of a 5‐evaluation design (Kennedy 2000a, Kennedy 2000b); the report for all five sites stated that parental consent was waived for two sites where the experimental program targeted sexually active youth. However, four of the five sites met this criterion, so it was unclear which two had waived the parental consent procedures. Type of consent was not determined for two trials (Jemmott 2004, Markham 2006).

Twenty‐two of the 39 included studies offered an incentive of some kind for participation in either the experimental program or the data collection process. The experimental programs in 11 evaluations were delivered as part of a school curriculum or as a means of earning course credit, creating an academic motivation for participation (Aarons 2000, Coyle 2001, Coyle 2004, Coyle 2006, Hernandez 1990, Kirby 1997, Markham 2006, Moberg 1998, O'Donnell 2002, Weeks 1997, Wright 1997). At least 19 trials offered participants some type of material incentive (Danielson 1990, DiIorio 2007, Hewitt 1998, Jemmott 1992, Jemmott 1998, Jemmott 1999, Kennedy 2000a, Kennedy 2000b, McBride 2000a, McBride 2000b, Philliber 2001, St Lawrence 1995a, St Lawrence 1999, St Lawrence 2002, Sikkema 2005, Stanton 1996, Stanton 2000, Villarruel 2006, Weeks 1997). Incentives included coupons, pizza parties, cash or gift certificates, and non‐monetary gifts. The experimental interventions frequently included end‐of‐program celebrations.

Interventions A number of similarities unified the 39 experimental interventions. Most importantly, every intervention promoted both sexual abstinence and condom or contraception use, and every intervention conveyed the message that abstinence is the best preventive choice. The use of this prevention hierarchy allows the grouping of these 39 programs in a systematic review. All but one of the programs (Hernandez 1990) targeted teenagers or adolescents. Every intervention conveyed information about HIV, STIs, the risks of sex, and different strategies for HIV prevention.

Within this rubric, however, there was a wide range of program designs. Reporting about intervention design and implementation was often limited, particularly for reporting on implementation fidelity. It was often extremely difficult to discern what proportion of the program was spent discussing and encouraging abstinence as opposed to condom use or other methods of risk reduction, which is a source of error for this review.

Notably, fifteen programs emphasized pregnancy prevention as much or more than HIV prevention (Aarons 2000, Coyle 2001, Coyle 2004, Coyle 2006, Danielson 1990, DiIorio 2006, Ferguson 1998, Kirby 1997, Markham 2006, McBride 2000b, McBride 2000a, Moberg 1998, O'Donnell 2002, Philliber 2001, Smith 1994); the remaining programs exclusively targeted HIV prevention. Studies that were limited to pregnancy prevention were excluded because interventions focused only on pregnancy may exclusively emphasize the consequences of penile‐vaginal sex, while neglecting the risks of oral intercourse, anal intercourse, or same‐sex sexual activity.

Not all of the abstinence‐plus interventions maintained an exclusive topical focus on sexual risk behaviors. Several programs included activities such as scheduled community service (Coyle 2006, DiIorio 2006, O'Donnell 2002); tutoring, job assistance, college application assistance, healthcare and mentoring (Philliber 2001); education‐related field trips (DiIorio 2006); general nutrition and substance abuse (Moberg 1998); a 6‐week career mentorship placement (Smith 1994); and parental monitoring (Dancy 2006, DiIorio 2007, Stanton 2000, Wu 2003). However, sexual risk reduction via abstinence and condom use remained primary goals for all of these programs.

The delivering organizations were schools for 10 programs (Aarons 2000, Coyle 2001, Coyle 2004, Coyle 2006, Hernandez 1990, Kirby 1997, Markham 2006, Moberg 1998, Weeks 1997, Wright 1997), community facilities for 24 programs (Dancy 2006, Danella 2000, DiIorio 2006, Ferguson 1998, Hewitt 1998, Jemmott 1992, Jemmott 1998, Jemmott 1999, Kennedy 2000b, Kennedy 2000a, McBride 2000b, McBride 2000a, Philliber 2001, Sikkema 2005, Smith 1994, St Lawrence 1995a, St Lawrence 1999, St Lawrence 2002, St Lawrence 1995b, Stanton 1996, Villarruel 2006, Wu 2003, Jemmott 2004, DiIorio 2007), schools and community facilities for 2 programs (O'Donnell 2002, Stanton 2006), healthcare personnel for 2 programs (Boekeloo 1999, Danielson 1990), and staff visiting family homes in one program (Stanton 2000). Twelve programs were delivered in large groups or classroom format (Aarons 2000, Coyle 2001, Coyle 2004, Coyle 2006, Ferguson 1998, Hernandez 1990, Kirby 1997, Markham 2006, Moberg 1998, O'Donnell 2002, Weeks 1997, Wright 1997), 24 were delivered in small groups (Dancy 2006, Danella 2000, DiIorio 2006, Hewitt 1998, Jemmott 1992, Jemmott 1998, Jemmott 1999, Kennedy 2000b, Kennedy 2000a, McBride 2000b, McBride 2000a, Philliber 2001, Sikkema 2005, Smith 1994, St Lawrence 1995a, St Lawrence 1999, St Lawrence 2002, St Lawrence 1995b, Stanton 2006, Stanton 1996, Villarruel 2006, Wu 2003, Jemmott 2004, DiIorio 2007), two involved one‐on‐one delivery (Boekeloo 1999, Danielson 1990), and one was delivered to parent‐child dyads (Stanton 2000).