ABSTRACT

A plethora of new and exciting findings have dramatically widened the horizons of plant RNA-related research. Despite being identified decades ago, RNA modifications were largely ignored owing to the immense difficulty in studying them with traditional methods. We now know that these chemical additions to RNA nucleotides affect a myriad of plant biological processes ranging from plant growth and development to stress responses. The field of epitranscriptomics, the study of RNA modifications, has been dominated by m6A in messenger RNAs (mRNAs), while modifications other than m6A remained largely unstudied. A recent increase in studies investigating other RNA modifications and the development of novel tools has added to the evolving landscape of plant epitranscriptomic research. As this non-m6A RNA modification research gathers pace, we use this review to provide a snapshot of the current state-of-the-art regarding these modifications with a focus on those occurring in functional non-coding RNAs as compared to mRNAs.

KEYWORDS: RNA biology, RNA modifications, epitranscriptome, plant RNA biology, RNA degradation, RNA stability

Introduction

From the discovery of nuclein by Miescher at the end of the 19th century to current studies, many discoveries have been made to better understand the composition, the structure, and the functions of nucleic acids. During the 20th century, scientists like Phoebus Levene and Albrecht Kossel furthered our knowledge about nucleic acids with distinction between DNA and RNA being established alongside the identification of canonical building blocks of nucleic acids, nucleotides. Chemical modifications of canonical nucleotides Adenine (A), Thymine/Uracil (T/U), Cysteine (C), and Guanine (G) have been known and investigated as epigenetic (DNA)/epitranscriptomic (RNA) modifications. In fact, the field of epitranscriptomics was kickstarted by the discovery of pseudouridine (Ψ) in RNA [1] and its characterization as the ‘fifth nucleotide’ in 1957 [2] but remained stagnant until more recently. More than 170 different RNA modifications have now been identified [3]. Nucleotide modifications involve isomerization of the nucleobase (such as in pseudouridine) or the addition of chemical groups on either the nucleobase (e.g. N1-methyladenosine (m1A), C2-methyladenosine (m2A), N6-methyladenosine (m6A), 5-methylcytosine (m5C), ac4A, etc.) or on the ribose (e.g. 2’-O-ribose methylation (Nm)). Among these, methylation is the most common type of covalent modification observed so far [3,4].

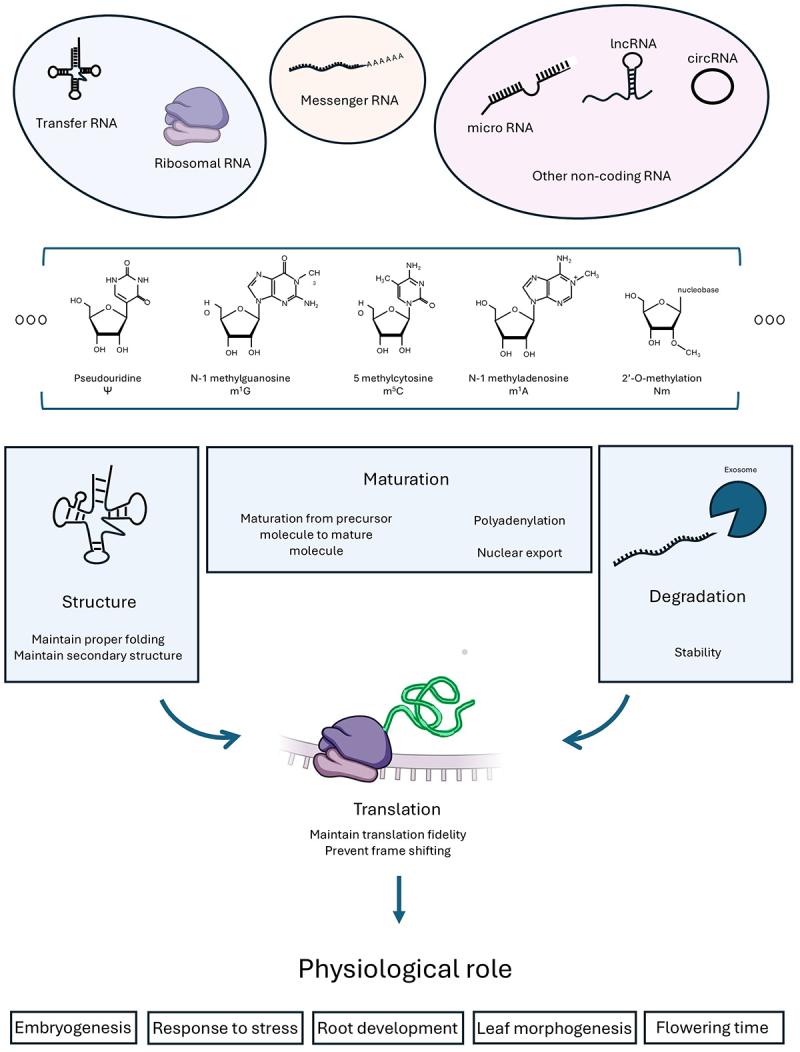

These chemical modifications can have profound impacts on RNA biology ranging from co- to post-transcriptional regulation. Recently, our approach to studying RNA modifications has evolved alongside rapid technological advancements. These include chromatography techniques allowing the identification of a modification as part of the RNA molecule to antibody-based techniques and long read sequencing emerging more recently that enables us to pinpoint the precise location of a modified RNA base. Additionally, numerous recent studies on the functions and physiological effects of the modifying enzymes responsible for the writing, reading, or erasing of RNA modifications have revealed an extremely important and extremely fast-moving field of study. Here, we describe the present spectrum of RNA modifications in plant transcriptomes and focus our discussions on the most recent findings and potential future directions in this exciting field of research (Figure 1). More specifically, this review focuses on non-m6A modifications with an emphasis on the modifications that occur in various classes of plant non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

A snapshot of RNA modifications and their roles in various RNA types. More than 170 different RNA modifications have been identified on various RNA species ranging from tRNAs to long non-coding RNAs. They affect RNA biology in varied ways including but not limited to altering RNA secondary structure and RNA turnover, ultimately affecting protein production, thus representing another potent layer of gene expression regulation.

Table 1.

A list of RNA modifications, their modifying enzymes, and which RNAs contain them.

| Modification | Type of RNA it can be found on |

Modifying enzyme |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudouridine Ψ |

tRNA; rRNA; mRNA; miRNA |

AtPUS10 AtTruA family proteins AtTruB family proteins AtTruD family proteins AtRsuA family proteins AtRluA family proteins |

| N1-methylguanosine m1G |

tRNA; mRNA* | AtTRM5A |

| 5-methylcytosine m5C |

tRNA; rRNA; mRNA; lncRNA |

AtTRM4B AtTRDMT1 (DNMT2) |

| N1-methyladenosine m1A |

tRNA; rRNA; mRNA; circRNA; lncRNA |

AtTRM61 AtTRM6 |

| C2-methyladenosine m2A |

tRNA; Chloroplast rRNA |

AtRLMN1 (Chloroplast rRNA) AtRLMN2 (Chloroplast tRNA) AtRLMN3 (Cytosolic tRNA) |

| 5-methyluridine m5U |

tRNA | AtTRM9 for mcm5U AtALKBH8 for mchm5U ROL5 & CTU2 for mcm5s2U AtTRM7 (SCS9) for mcm5Um |

| Inosine I |

tRNA | AtTAD2 (EMB2191) AtTAD3 (EMB2820) |

| N2,N2-dimethylguanosine m22G |

tRNA; rRNA | AtTRM1A AtTRM1B |

| 2’-O-methylation Nm |

tRNA; rRNA | FIB1 FIB2 |

| N4-acetylcytidine ac4C |

tRNA; rRNA; mRNA |

ACYR1 ACYR2 |

| N6-methyladenosine m6A |

tRNA; rRNA; mRNA circRNA; lncRNA |

MTA FIONA |

*Predicted by HAMR. Vandivier et al. 2015.

Transfer RNA (tRNA)

Transfer RNAs (tRNAs) are adaptor molecules that play a central role in translation by bringing amino acids to ribosomes, thereby allowing the polypeptide chain to be synthesized. These small ncRNAs (generally between 76 and 90 nucleotides long) harbour a cloverleaf secondary structure stabilized by intramolecular base pairing. tRNAs are the second most abundant type of RNA in a cell after ribosomal RNA (rRNA). In addition to their canonical role in translation, tRNAs have also been reported to be involved in the synthesis of other organic compounds [5].

tRNAs are the RNA molecules that carry the largest proportion of modifications compared to their length. It is also well established that their RNA modifications influence translational efficiency and fidelity through directing the folding of these RNAs into their proper secondary structure [6]. Modifications on tRNAs are most of the time only present on a subset of the population of isoacceptors, but specific positions have been identified as conserved key modified nucleotides. Depending on their position and chemical properties, modifications can have an impact on the amino-acylation, the codon–anticodon interaction, or the stability of the secondary structure. For example, modifications near the anticodon loop, at positions 32, 34 (the wobble position), 37, and 38 are known to be crucial by affecting codon–anticodon interactions [6,7]. Because of the universal functions of tRNAs in living organisms, findings on modified nucleotide effects done in yeast provide a model for understanding these covalent nucleotide additions in multicellular eukaryotes. However, this has not inhibited the studies of tRNA modifications in the processes of whole organism development and response to stress [8]. For instance, liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) results identified 21 kinds of RNA modifications in Arabidopsis tRNAs, some of which are associated with normal organism development or responses to stress [8]. Below we discuss some of the most studied/conserved modifications (Ψ, m1G, m5C m1A, m2A, m5U, inosine, and m22G) in tRNAs, which have recently been the subject of focused studies, resulting in exciting new discoveries in the field of plant RNA modifications. These modifications are graphically depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Conserved transfer RNA modifications. A majority of tRNA modifications identified so far have been found to be highly conserved across species. Modifications in important tRNA regions like the anti-codon loop and the TΨC loop are depicted in the figure.

Pseudouridine (Ψ)

Ψ is a post-transcriptional modification that results from the isomerization of a U nucleotide. This isomerization introduces an additional hydrogen bond donor on the Hoogsteen face. It is the most abundant modification when all known RNA modifications are taken into consideration because it is widely present on functional non-coding RNAs (mainly ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and tRNA). In fact, transcriptome-wide mapping of Ψ identified a total of 232 sites on plant tRNAs [9]. Unsurprisingly, highly conserved positions (13, 27, 38, 39, and 55) known to be pseudouridylated in eukaryotes and yeast were identified in plant tRNAs as well [10]. Specifically, Ψ13 and Ψ55 are conserved modification sites in eukaryotes and contribute to the stabilization of the D stem and the TΨC loop, respectively. Ψ on tRNAs is deposited by pseudouridine synthases (PUSs).

In 2022, the identification of specific PUS enzymes in plant genomes was done through a phylogenetic analysis that revealed that Arabidopsis and maize genomes contained 20 and 22 genes encoding PUS proteins, respectively [11]. Interestingly, these PUS proteins were clustered into six known subfamilies (RluA, RsuA, TruA, TruB, PUS10, and TruD). Furthermore, it was recognized that the PUS10 class of enzymes is often found to be a single-copy gene in many plant genomes [12]. Even though the plant PUS10 demonstrates a low overall sequence similarity to other eukaryotic members of this enzyme [13], it is still believed to have the same function in catalysing Ψ54 and Ψ55 on tRNA due to its conserved functional domain architecture [14]. Overall, the writing enzymes and specific Ψ sites in tRNAs tend to be conserved between plants and other eukaryotic organisms demonstrating the importance of this RNA modification.

N1-methylguanosine (m1G)

One of the first mentions of m1G in plant tRNAs are for those present in wheat germ [15]. m1G is a conserved modification found at position 37 of eukaryotic tRNAs [6]. As stated above, many tRNA modifications were initially studied in yeast with the assumption that these findings extrapolate across kingdoms, but experiments done in plants were done only recently to specifically decipher the effects on plant development and adaptation to stress. Through homology analyses using the sequence of the m1G writer protein from yeast, AtTRM5 was identified and validated as the m1G writer in Arabidopsis [16,17]. AtTRM5 was shown to be localized in the nucleus and has a dual functionality as it can also catalyse inosine methylation at the 1 position of the nucleotide ring (m1I). Defects in AtTRM5 lead to a late flowering phenotype and an overall reduction of plant growth with smaller rosette leaves and roots. In fact, attrm5 mutants also display decreased levels of auxin and impaired functionality of their translation machinery, highlighting the ubiquitous role of m1G37 on tRNAs. To be able to deduce the role of a given modification by studying specific writer mutants is convenient, but conclusions often need to be validated through additional experimental work. In the case of a bifunctional protein like AtTRM5, it is hard to discriminate the role of m1G and m1I with the analysis of this specific mutant. However, the importance of m1G to tRNA functionality means that additional studies on AtTRM5 function are needed in the future.

5-methylcytosine (m5C)

The m5C profile of tRNAs for Arabidopsis was established for the first time in 2015 [18]. Using RNA bisulphite conversion followed by high-throughput sequencing, the authors reported that five structural positions: C38, C48, C49, C50, and C72 were frequently methylated on tRNAs. Furthermore, these experiments showed that tRNAAsp(GTC) was the most highly methylated tRNA and was the only tRNA that contained methylation at all five structural positions. The structure of tRNAAsp(GTC) may require these additional m5C sites for greater stability or resistance to cleavage. In addition to the core tRNAs involved in protein synthesis, plants also have a variety of specialized tRNAs in the mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes that also have their own protein synthesis machinery. Interestingly, no m5C sites were detected in Arabidopsis chloroplast or mitochondrial tRNAs. It was also found that TRNA METHYLTRANSFERASE4B (AtTRM4B) and tRNA ASPARTIC ACID METHYLTRASFERASE1 (TRDMT1, aka DNA METHYLTRANSFERASE 2 (DNMT2)) are the methyltransferases required for m5C tRNA methylation events with no apparent redundancy of function between the enzymes. In fact, methylation events at position 38 in certain tRNAs (tRNAAsp(GTC), tRNAGly(CCC), and tRNAGly(GCC)) were shown to be specifically added by TRDMT1. Finally, attrm4b and trdmt1 single mutants are more sensitive to hygromycin. This is because hygromycin decreases translation efficiency when the structural integrity of tRNAs is altered. Thus, these results suggest that m5C participates in the proper maintenance of tRNA secondary structure in plants. It is important to note that TRM4B has also been shown to methylate cytosines on mRNA [19] (reviewed below). Thus, our current understanding of m5C does not allow us to distinguish tRNA – as compared to mRNA-specific effects on plant physiology. In general, there is still much to learn considering m5C in eukaryotic functional ncRNAs.

N1-methyladenosine (m1A)

Even though the presence of m1A was widely accepted within eukaryotic tRNAs, it was reported for the first time in plant tRNAs in 2010 [20]. These studies identified this modification at multiple positions and is most conserved at position 58 where it plays an important role in the structural stability of the TΨC loop. Recent studies found that m1A58 is added to tRNAs by AtTRM61 and AtTRM6 [21,22]. First, they demonstrated that these two nuclear-localized proteins are thought to interact together to form a functional heterotetramer complex. Additionally, the analysis of attrm61 and attrm6 mutants indicated they result in embryo lethality because no homozygous mutant plants for either of the two genes could be obtained. Furthermore, the high rate of seed abortion in heterozygous plants (likely because of the 25% homozygous mutant seeds from these plants) demonstrates the importance of AtTRM61/AtTRM6 for embryo development. In fact, it was revealed that AtTRM61 is required for embryogenesis and endosperm development because attrm61 mutants exhibited arrested embryos at early stages (2–4 cell stages) and endosperm with diminished numbers of nuclei [22]. To connect this severe phenotype to translation interference, the authors investigated the level of initiator methionyl-tRNA (tRNAiMet, the precursor molecule of tRNAMet) and found a correlation with the level of m1A in tRNA [21]. Relatedly, the overexpression of tRNAiMet rescued the low fertility mutant phenotype [22]. m1A58 disruption had already been shown to result in tRNAiMet instability and a diminution of translation initiation as a subsequent consequence in other organisms [23,24], and the same was found for plants [21]. However, many questions remain unanswered, even when it comes to a well-studied modification such as m1A. For example, the methyltransferases responsible for m1A addition to chloroplast and mitochondrial tRNAs still need to be identified. In addition, m1A is a dynamic modification on human tRNAs with ALKBH1 as the corresponding demethylase [23], but the plant demethylase ortholog is currently unknown. Finally, it would be interesting to investigate the potential regulation of plant tRNAs that is potentially mediated by m1A, as has been seen in other eukaryotes [23,24].

C2-methyladenosine (m2A)

m2A is one of the modifications found at position 37 of certain tRNAs in E. coli [25] and was also identified as a rare modified nucleoside in several plant species (e.g. wheat tRNAArg ICG [26] or tobacco tRNAGln UmUG [27]). Recently, m2A was shown to be present on chloroplast and nuclear-encoded tRNAs in multiple species across the plant kingdom [28]. Using LC-MS-MS, the researchers found two cytosolic tRNAs (tRNAArgACG and tRNAGlnUUG) and four chloroplast tRNAs (elongator tRNAMetCAU, tRNAArgACG, tRNASerGGA, andtRNAHisGUG) containing m2A in Arabidopsis. Notably, m2A on tRNAGlnUUG was present in all the species tested (Arabidopsis, Oryza sativa, Spinacia oleracea, Physcomitrella patens, and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii). They then confirmed that m2A is always situated at position 37, highlighting the conservation of modification at this tRNA position. When studying the effect of m2A37 on tRNA secondary structure, m2A37-containing tRNAs migrated slower in a native polyacrylamide gel than non-m2A37 tRNAs. Moreover, by measuring the melting curve, they observed an increase of the transition point temperature, suggesting that m2A37 induced a relaxed conformation of the anticodon loop. This relaxed conformation can have an impact on translation efficiency (calculated as the amount of ribosome on a given gene). Specifically, this modification was found to promote translation efficiency of mRNAs containing tandem m2A37-tRNA-dependent codons [28]. The methyltransferase responsible for m2A in E. coli – RlmN – is a dual-specificity enzyme that methylates both rRNA and tRNA [29]. In Arabidopsis, researchers found three homologs of this enzyme named RLMNL1–3 and showed that RLMNL1 and RLMNL2 methylate chloroplast rRNAs and tRNAs, respectively, while RLMNL3 methylates cytosolic tRNAs, showing a specialization of substrates for the three plant homologs [28].

5-methyluridine and derivatives

Nucleotides at the wobble position are heavily modified and are thoroughly investigated because of their impact on translation fidelity. Such modifications participate in the degeneracy of the genetic code by enlarging the possible base pairing to the third codon nucleotide. U at the wobble position (U34) is frequently modified to 5-carbamoylmethyluridine (ncm5U), 5-methoxycarbonylmethyluridine (mcm5U), or other variants that are 2’-O methylated (such as 5-methoxycarbonylmethyl-2’-O-methyluridine (mcm5Um)), hydroxylated to mchm5U, or that are further modified by thiolation giving 5-methoxycarbonylmethyl-2-thiouridine (mcm5s2U) [30]. LC-MS/MS results indicate that the most abundant form in total tRNA from Arabidopsis are ncm5U, mcm5s2U, and mchm5U whereas cm5U and mcm5U are detected to a lesser extent.

Modifications on U34 increase the stability of the anticodon loop and stabilize the codon–anticodon interaction [31]. Concerning the modifying enzymes adding these different chemical groups, various pathways are required and investigated in plants. The methylation of mcm5U from 5-carboxymethyluridine (cm5U) is catalysed by TRM9 and is dependent on the co-expression of TRM112a or TRM112b, whereas the hydroxylation reaction of mcm5U to mchm5U requires ALKBH8 [30]. As for the thiolation, its pathway first involves the transfer of the sulphur group by the sulfurtransferase CNX5 to two ubiquitin-related proteins URM11 and URM12. The sulphur group is then added to tRNAs by CTU2 and ROL5 [32–34]. The thiolation of mcm5s2U has also been shown to be dependent on the elongator complex which was previously identified as responsible for the formation of xm5U (mcm5U or ncm5U) [32]. Defects in U34 thiolation revealed impairment in leaf morphogenesis [32], root development [33] and immunity to pathogen infection [34], thus demonstrating the importance of modifications at the wobble position for Arabidopsis development and response to stress. In addition, the Elongator complex is composed of six ELONGATOR PROTEINs (ELP1–6) with roles in ABA and oxidative stress responses [35,36]. Because the elongator complex is involved in many other biological processes such as DNA methylation or cell cycle progression [37,38], it is difficult to discern the effects that are solely a consequence of the loss of U34 thiolation in elp mutant plants. Finally, the 2’-O methylation is performed by TRM7 (aka SCS9), which is required for effective immune response to Pseudomonas syringae [39]. Recently, a study using data-independent acquisition MS also detected increased abundance of U34 modification (nm5U, ncm5U, nchm5U and mcm5U) alongside with an upregulation of TRM9 and ELP1 upon salt stress in Arabidopsis [40]. This study hints at an additional gene regulation mechanism role for the wobble position modifications in plant abiotic stress response. As more and more regulatory pathways involving the modification of tRNA U34 are discovered, further investigations are required to uncover a complete picture of the importance of modification of this specific uridine nucleotide in plant tRNAs.

Inosine (I)

Isoacceptors containing an A at the wobble position also undergo massive modification through Adenosine-to-Inosine editing (I34). I34 results from the determination of an A at position 34 and expand the decoding capacity of a given tRNA by being able to base pair with U, C, and A [41]. In Arabidopsis, the tRNA-specific adenosine deaminases (TAD2 and TAD3) is found in the nucleus and form a heterodimeric complex [42]. These proteins are encoded by essential genes, and their disruption leads to embryo lethality, stopping development at the globular stage. Mutants with reduced expression of TAD2 and TAD3 showed stunted growth and displayed compromised adenosine-to-inosine editing efficiency in six tRNAs species [42]. In addition, one deaminase encoded in the nuclear genome but targeting the chloroplast tRNAArg has also been identified: TADA [43,44]. Interestingly, disruption of chloroplast tRNAArg deamination impairs photosynthesis and phenotypically results in pale-green leaves, diminished fertility and an overall delayed growth [43].

N2,N2-dimethylguanosine (m22G)

N2,N2-dimethylguanosine at position 26 (m22G26) is another conserved modification found in plant tRNAs [10]. m22G26 is most likely providing essential structural stability by regulating intramolecular base-pairing in the hinge region [45,46]. Arabidopsis AtTRM1A and AtTRM1B were shown to be the enzymes responsible for m22G26 addition in the yeast heterologous system [47] and further validated as the bona fide m22G26-adding enzymes of plant cytosolic tRNAs [48]. Interestingly, it was by investigating the interactome of Protein-only RNase P2 (PRORP2) a protein involved in the maturation of pre-tRNA by 5’ exonuclease activity, that the authors identified AtTRM1A and AtTRM1B. When studying the double mutant attrm1a attrm1b, LC-MS/MS showed decreased level of m22G26 on cytosolic tRNA by ≈ 90%, while single mutants did not show any variation, suggesting a redundancy of function. Knockout of both methyltransferases resulted in severe growth inhibition and, at the molecular level, in downregulation of tRNAs containing m22G26 implying that this modification is involved in the overall steady state level of these tRNAs. Further investigations should leverage uncertainties on the role of m22G26 on tRNA maturation and stability.

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA)

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) provides the structural framework necessary for ribosome formation and function and is therefore a crucial component of the translation machinery. A specific collection of rRNAs forms a large subunit of the ribosome (25S, 5.8S, and 5S) and the 18S rRNA assembles to form a small subunit of the ribosome. They are the most abundant type of RNA in eukaryotic cells and harbour many modified nucleotides within their sequences. For instance, Ψ and methylation on the 2’ hydroxyl group of the ribose (Nm) are the two main covalent RNA modifications that occur in all rRNA molecules [49]. Ψ and Nm modifications can be guided by two different mechanisms: an RNA-dependent mechanism and an RNA-independent mechanism. Most modifications are added by the RNA-dependent mechanism where small nucleolar RNA-protein complexes (snoRNPs) recognize target sites through base-pairing interactions. The snoRNP includes a small nucleolar RNA (snRNA) molecule along with core protein components [50,51]. As for the RNA-independent mechanism, ‘stand alone’ enzymes are sufficient to catalyse these reactions. The rRNA modifications tend to occur in functionally important regions such as the peptidyl transferase centre, the A, P, and E sites as well as the mRNA binding site [52]. For example, using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) researchers discovered an interaction in a small subunit of tobacco ribosomes between 2’-O-methylated cytosine at position 1645 and N6 methylated adenine at position 1771 via a non-canonical base pairing interaction. This RNA modification-driven binding allows for the correct positioning of the mRNA strand [53]. rRNAs have long been viewed as homogeneous molecules that strictly perform their functions in translation without much intrinsic regulation. This point of view is evolving to a more heterogeneous composition, notably with the presence of modified nucleosides, allowing a new layer of gene expression regulation [54].

Pseudouridine (Ψ)

Ψ in plant rRNAs was first detected in wheat in 1978 [55]. Instances of Ψ in plant rRNAs are numerous, with 187 sites detected by genome-wide pseudouridine sequencing in Arabidopsis [9]. This mapping allowed validation of Ψ depositions that were previously only predicted [56,57] and identification of novel sites. Looking at the locations of Ψ gave insight into their possible significance in protein synthesis. Notably, some of the potential most significant sites being the three Ψ sites in the decoding region of the small subunit and the six Ψs in the peptidyltransferase and the A-site of the large subunit. These results were further validated by the cryo-EM structure of the plant ribosome that was recently obtained for tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) [58] and from tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) [53]. In fact, the Ψs identified by the different methods showed a high degree of similarity across the three species. The most pronounced differences were found for the 18S (small subunit), and these differences could be a result of the different techniques used for the three plant species. More intriguingly, the differences in identified Ψ sites may be the result of stage-specific, tissue-specific, or species-specific pseudouridylation that could indicate distinct Ψ-related ribosomal regulation [53]. This hypothesis will require future testing.

The enzymes responsible for directing Ψ of rRNAs are known as pseudouridine synthetases (PUSs) and can either be guided to specific Ψ sites by H/ACA snoRNAs or catalyse the reactions as standalone proteins. In the RNA-dependent mechanism, CBF5 is the PUS responsible for pseudouridylation of yeast rRNAs and its ortholog in humans (NAP57) was shown to have the same role. Although the functional homology of the plant ortholog AtCBF5 still needs to be directly shown, it is assumed to play the same role in plant rRNA maturation [59]. This is because this protein is localized in the plant nucleolus and Cajal bodies and interacts with the H/ACA snoRNP assembly factor AtNAF1, which participates in the maturation of H/ACA snoRNAs [59]. Several other PUS enzymes have been identified to be responsible for rRNA pseudouridylation as well. For example, SUPPRESSOR OF VARIEGATION1 (SVR1) in Arabidopsis and THERMOSENSITIVE CHLOROPHYLL DEFICIENT3 (TCD3) in rice have been identified as chloroplast rRNA PUSs [60,61]. Both svr1 and tcd3 mutant plants have decreased pseudouridylation in chloroplast rRNAs [9,61,62]. TCD3 is also involved in chloroplast development at low temperatures. Finally, LEAF CURLY AND SMALL1 (FCS1) is a PUS responsible for the pseudouridylation of U1692 of mitochondrial 26S rRNAs [63]. fcs1 mutants have a late germination phenotype as well as delayed development and reduced fertility, suggesting that the pseudouridylation of mitochondrial 26S rRNA is essential for proper plant development. Overall, pseudouridylation of plant rRNAs is necessary for proper development, and stress responses and more effort should be given to uncover the regulation and potential physiological functions for this important RNA modification.

2’-O-methylation (Nm)

Two recent studies focused on mapping the sites of 2’-O-methylation in Arabidopsis cytoplasmic rRNAs revealed over 100 potential Nm sites in these functional ncRNAs [64,65]. The studies were done using the RiboMeth-seq approach that relies on the principle that Nm prevents alkali hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bonds between modified nucleotides and their adjacent 3' nucleotides. RNA fragments are then sequenced by Illumina sequencing and aligned to a reference genome, allowing the simultaneous mapping and quantification of Nm sites. The cryo-EM model of tobacco rRNA indicates ~110 putative Nm sites, which aligns well when compared to the RiboMeth-seq driven studies [53].

The addition of most Nm sites is guided by C/D snoRNAs with approximately 90% of Nm sites having a matching C/D snoRNA sequence. The remaining 10% are thought to be added by standalone RNA methyltransferases (RMTases). In fact, four RMTases have been identified in other organisms associated with C/D snoRNAs to direct Nm addition. They are Fibrillarin, nucleolar protein 56 (NOP56), NOP58, and L7Ae in humans. By studying the orthologs of these proteins in Arabidopsis, the intrinsic mechanism is being unravelled in plants. Specifically, there are two Fibrillarin, FIB1 and FIB2 [66], two NOP56, two NOP58, and four L7Ae proteins encoded by genes in the Arabidopsis genome. Interestingly, fib1 and fib2 single mutant plants both showed a reduction of rRNA Nm with fib1 displaying a larger impact. As Nm continues to be studied for its role in maintaining rRNA secondary structure and translation efficiency, studies like these are revealing plant and developmental stage specificity of Nm site addition and are also driving the functional understanding of this important RNA modification [67]. Moreover, the reason why some Nm sites seem to be deposited by standalone RMTases whereas the majority are guided by snoRNA, remains unsolved. Thus, much more study of this specific rRNA modification is needed in the future.

Other rRNA modifications

Although Ψ and Nm are the most widely studied modifications of rRNA because of their high levels of occurrence, other types of RNA modifications are found that also participate in the catalytic activity and structural integrity of the rRNA molecules. In total, numerous types of RNA modifications can be found on the 18S rRNA alone. They include the following 2'-O-methyladenosine (Am), 2'-O-methylcytidine (Cm), 2'-O-methylguanosine (Gm), 2'-O-methyluridine (Um), m6A, m5C, N7-methylguanosine (m7G), N2,N2-dimethylguanosine (m22G), N6,N6-dimethyladenosine (m66A), N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C), and 1-methyl-3-(3-amino-3-carboxypropyl) pseudouridine (m1acp3Ψ) [53,58,68]. As for the 25S rRNA, at least 12 types of RNA modifications were reported including Ψ, Am, Cm, Gm, Um, m6A, m5C, m7G, m1A, m22G, m66A, and 3-methyluridine (m3U).

To identify these sites, researchers first obtained highly pure 18S and 25S rRNA by doing (1) polyA-based mRNA depletion and (2) an agarose gel electrophoresis-based purification to eliminate any bacterial rRNA contamination (23S and 16S rRNA) and then performed liquid chromatography – electrospray ionization – tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS). Notably, the study revealed the presence of m22G and m66A on 18S and m22G, m66A, m7G, and m3U for the first time in plant 25S rRNA. Extensively studied for its regulatory effects on mRNA (see below), m6A on rRNA has recently been the subject of study for its ability to influence ribosome function [69]. Specifically, this modification is only found on 18S rRNAs (but not on 25S) and only one m6A is reported as a conserved site: m6A 1771 [53]. It is specifically added on 18S RNA by AtMETTL5 that has a ubiquitous expression profile in Arabidopsis plants. Polysome profiling in the atmettl5 mutant revealed decreased translation levels. Furthermore, AtMETTL5 was found to be required for proper hypocotyl photomorphogenesis under blue light treatment through the regulation of translation of transcripts encoding blue light-related proteins. Overall, there is still much to learn about the functional significance of modified nucleotides throughout the sequences of plant rRNA molecules.

Nucleotide modifications in messenger RNA (mRNA)

In popular science references, the mention of RNA is most likely in the context of mRNA. One of the central molecules in the classical central dogma of biology, mRNA, acts as a bridge between the stored genetic information in DNA and its translation into proteins. From the beginning of their production (transcription), mRNAs are subject to a variety of molecular processes ranging from splicing to polyA+ tailing and includes additions of various epitranscriptomic modifications. In this section, we will briefly review the current state of covalent RNA modifications that have been found to occur on mRNA molecules.

N6-methyladenosine (m6A)

m6A is currently the most abundant known internal modification on mRNA molecules and aptly has become the most researched modification in recent years. Since the focus of this review is on non-m6A modifications, we direct the readers to a couple (among a myriad) of reviews that do an excellent job of summarizing the varied aspects of m6A and its effects on mRNA and plant biology in general [70–73]. Briefly, m6A is deposited by a multi-protein complex called the methyltransferase complex (MTC), whose main catalytic component is mRNA ADENOSINE METHYLASE A (MTA) [74]. Recently, FIONA1 (FIO1) was reported to show m6A methyltransferase activity on its own collection of mRNA molecules as well [75]. However, it appears that these could be indirect effects involving crosstalk between FIO1 mediated U6 snRNA methylation and altered splicing patterns [76,77]. Other major classes of m6A related proteins include YT521-B homology (YTH) domain containing proteins (‘m6A readers’) and α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase ALKB homology (ALKBH) family proteins (‘m6A erasers’). In line with its widespread presence in mRNAs, m6A has been found to regulate almost all aspects of mRNA fate including, but not limited to, stability, alternative polyadenylation, degradation, and translation [70].

5-methylcytosine (m5C)

m5C was first reported in plant mRNAs in 2017 [78]. The researchers of this study used bisulphite conversion followed by sequencing to identify nearly 1000 m5C sites in Arabidopsis mRNAs. They reported a 3’ UTR bias of m5C distribution. m5C appeared to have a minor negative effect on mRNA abundance. An RNA cytosine-5-methyltransferase (RCMT) named tRNA-SPECIFIC METHYLTRANSFERASE 4B (TRM4B) was reported to instal m5C on mRNAs across different plant organs. Interestingly, trm4B mutant plants demonstrate a short root phenotype that was attributed to reduced cell proliferation in the root apical meristem. In a demonstration of rapid methodological progress in the field of epitranscriptomics, six months later, another research group used an antibody-based m5C-RIP-seq approach to identify nearly 6000 m5C peaks [19]. Thanks to a more substantial dataset, the authors were able to resolve the location of m5C within the modified mRNAs to peaks located just after and just before the start and stop codons, respectively. In addition, m5C was implicated in negatively regulating mRNA translation efficiency. A deeper dive into the role of TRMB4 revealed that TRMB4 affects m5C only in roots and not in aerial tissue [19].

Independent m5C-RIP-seq and nanopore sequencing by an additional group identified 562 distinct m5C containing mRNAs [79]. They found that ~64% of the m5C containing mRNA molecules were cell-to-cell mobile. The identification of two motifs CC[AUG]CC[AG] and C[UA]UCUUC in 182 and 82 transcripts, respectively, perhaps provides a first indication of specific m5C motifs, albeit in the context of mobile mRNAs. Consequently, a homolog of Arabidopsis TRM4B and human NOP2/Sun (NSUN) domain family member (NSUN2) was identified as a m5C methyltransferase in rice [80]. In this rice study, researchers used bisulphite sequencing and found OsNSUN2 mediated m5C deposition was crucial for plant response to heat stress providing the first evidence for a possible role of m5C in plant response to abiotic stresses. In fact, a subset of transcripts was found to gain m5C after heat stress while a much smaller set lost the m5C mark, pointing to a reprogramming of m5C landscape upon stress. Interestingly, contrary to previous reports, this study reported a positive correlation between m5C and mRNA translation efficiency [80].

Recently, nanopore sequencing in rice revealed that salt stress results in significantly reduced m5C levels in mRNAs [81]. This study identified m5C in >25,000 rice transcripts with a peak distribution consistent with a previously published report [19]. Among these, 2983 transcripts were common across six different tissue samples, providing evidence for common methylated transcripts and those that demonstrate tissue-specific m5C deposition. In their study, this group also observed that over 75% of transcripts modified with m5C also had the m6A mark. While both m5C and m6A were observed to stabilize the transcript, there did not seem to be an additive effect [81]. A new bisulphite-free sequencing method, m5C detection by TET-associated chemical labelling (m5C-TAC) has been developed with demonstrated success in mammalian systems [82]. This technique promises base-resolution and highly specialized detection of m5C in RNA molecules. The use of this technique and its comparison to m5C-RIP-seq in plant systems remains to be done. Such technical and methodological developments will certainly provide detailed insights into the role of m5C in governing mRNA fate through additional future studies.

Pseudouridine (Ψ)

Ψ was reported in Arabidopsis mRNA as recently as 2019 [9]. Transcriptome-wide identification of Ψ in Arabidopsis was done using N-cyclohexyl-N'-(2-morpholinoethyl)-carbodiimide-metho-p-toluenesulfonate (CMC) to label Ψ eventually blocking reverse transcription during library preparation followed by high-throughput sequencing. Using this method, the authors identified Ψ in both coding and non-coding transcripts. In mRNA, 451 Ψ sites (within 332 gene transcripts) were identified with a positive distribution bias within the 5’ UTR and the coding sequence (CDS), while 3’ UTRs were found to lack Ψ as compared to U. An observed decrease in the expression of several photosynthesis-associated genes in chloroplast Ψ synthase (SUPPRESSOR OF VARIEGATION 1 (SVR1)) svr1 mutant plants indicated at least a partial role of SVR1 mediated pseudouridylation in regulating protein expression [9]. Ψ remains poorly studied in the context of plant mRNAs and whether this is due to the lack of sensitivity in current techniques, or the biological aspects of this modification remain to be seen.

N1-methyladenosine (m1A)

The first transcriptome-wide study of m1A in a plant system was done in petunia and identified transcripts from ~3000 genes that contained m1A [83]. The most common site of m1A occurrence was found to be just after the start codon. The authors of this study used an antibody-based approach and reported that ethylene treatment resulted in a reduction in m1A levels. tRNA-specific METHYLTRANSFERASE 61A (PhTRMT61A) was found to affect m1A levels in mRNA and the authors suggested a possible role for m1A in RNA splicing, transcription/translation regulation and protein degradation [83]. A recent tomato-based study identified ~1900 mRNAs that had m1A sites as well as demonstrated enrichment of m1A at the start codon and in the CDS [84]. With a focus on the ripening process, the authors report a dynamic change in the m1A distribution along modified mRNAs depending on the stage of maturity of the tomato fruits including in a mutant that is insensitive to ethylene (never ripens). Both studies identified ‘CCAC’ and ‘GRAG’ as motifs enriched at the detected m1A sites [83,84]. At a more granular scale, transcripts of genes related to fruit flavour and aroma (e.g. MALATE DEHYDROGENASE (MDH), FRUCTOKINASE-LIKE1 (FLN1)), texture related (e.g. PECTINERASE3 (PE3) and fruit ripening (e.g. auxin-responsive protein IAA9, ALPHA AMYLASE (AMY)) exhibited mostly positive association of expression with m1A with notable exceptions [84]. While these data are encouraging, the exact role(s) of m1A in guiding plant mRNA fate needs to be studied in more detail.

5'-nicotinamide adenine diphosphate cap (NAD+ cap)

First identified in plant mRNAs in 2019, NAD+ caps serve as an alternative to the canonical m7G cap [85,86]. Variations of NADcapture-seq were utilized by two groups to report that Arabidopsis mRNAs are NAD+-capped. Most NAD+-capped RNAs were found to be transcripts of nuclear-encoded protein coding genes, and both studies concluded that NAD+-capped RNAs are very likely to be translated. One study observed that most NAD+-capped RNAs had shorter 5’ UTRs than their canonically capped versions, providing a possible deterministic factor between canonical and NAD+-cap deposition on a given RNA [86]. The development of a metal ion-free NAD-capture seq method in combination with m7G depletion by another group provided a more ‘gentle on nucleic acids’ approach to sequencing NAD+-capped RNAs and identified 5642 NAD+-capped RNAs including >80% of mRNAs identified by the previous NADcapture-seq studies [87]. In order to elucidate the role of NAD+ caps, a transcriptome-wide study in the context of D × O1 mutation (a known protein capable of removing NAD+ caps in vitro [88,89]) and abscisic acid (ABA) stress revealed that NAD+ caps could act as a degradation tag for ABA response-related mRNAs [90]. In addition, the authors noted this degradation to be a result of RDR6-dependent processing of NAD+ capped mRNAs into smRNAs [90].

More recently, it has been shown that D × O1 interacts with RNA GUANOSINE-7 METHYLTRANSFERASE1 (RNMT1) via its plant-specific 200 amino acid N-terminal extension and modulates the deposition of m7G on mRNAs [91]. In addition, the characterization of NUDIX family enzymes, AtNUDT19 and AtNUDT27, revealed them to also possess NAD+ decapping activity, thereby adding to the repertoire of proteins that can modulate NAD+ cap levels in mRNAs [92]. Interestingly, both AtNUD19 and AtNUDT27 are chloroplastic, but transcripts from chloroplasts have not been shown to contain NAD+ caps thus far. Thus, this seeming disparity in findings will need to be clarified in the future research. It is also intriguing that the NAD+ cap and m7G machinery seem to crosstalk with one another, and this connection also requires further clarification.

N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C)

Studies targeted at detecting and elucidating the role of ac4C in mRNAs have been gathering steam recently. The first transcriptome-wide profile of ac4C in plants was done using Arabidopsis and rice [93]. Using an antibody against ac4C, this study reported the occurrence of ac4C in transcripts from 2160 Arabidopsis genes and 3824 rice genes. In both rice and Arabidopsis, ac4C showed a higher distribution near the start codon with a smaller peak near the stop codon exclusive to Arabidopsis. A concurrent study also investigated ac4C in plants using a similar antibody-based approach and identified 325 transcripts with ac4C with a peak distribution biased to the 3’ end in contrast to the other study in both Arabidopsis and rice [94]. This concurrent study also identified two homologs of mammalian acetyltransferase NAT10, N-ACETYLTRANSFERASEs FOR CYTIDINE IN RNA (ACYR1 and 2), as potential ac4C modifying enzymes with single mutants exhibiting 1.3–3.5-fold lower ac4C abundance while double mutants were embryo lethal. In this study, ac4C was found within a CCWCCDCC (W = A or U or G; D = U or G or A) motif and was linked with mRNA stability and pollen viability [94].

In tomato plants, ac4C was detected in the coding region of 1211 transcripts [95]. The findings for this modification in tomato also demonstrated a 3’ end ac4C distribution bias as well as a similar sequence motif. Additionally, it was found that ac4C levels decreased as tomato fruits ripened alongside the increase of this modification on key ripening related mRNAs indicating ac4C’s role in mRNA stability with notable exceptions [95]. Combined, all these data point to a strict regulation of ac4C on mRNA with developmental controls in place. Better tools and experimental design are needed in future research studies to establish a definite relation between ac4C and mRNA turnover, especially since these effects are bound to be very specific and granular at the transcript level.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs)

miRNAs are small ~21nt long RNAs that play a vital role in the regulation of plant gene expression post-transcriptionally. miRNAs target mRNAs via sequence complementarity and inhibit their expression either via direct target RNA cleavage and/or translation inhibition. Transcribed from MIR genes by RNA polymerase II, miRNAs are produced via a two-step cleavage of their primary transcripts (pri-miRNAs). Core proteins involved in miRNA biogenesis include DICER-LIKE1 (DCL1), HYPONASTIC LEAVES1 (HYL1), and SERRATE (SE). These are assisted by several other accessory proteins like TOUGH (TGH), CELL DIVISION CYCLE5 (CDC5), CAP BINDING PROTEIN20/80 (CBP20/80) and others [96]. miRNA biogenesis has been found to be influenced by epitranscriptomic marks, which we will discuss further in the following section.

N6-methyladenosine (m6A)

m6A was first reported in plant pri-miRNAs in 2020 [97]. The absence of m6A on pri-miRNAs was reported to hinder miRNA biogenesis possibly via the alteration of pri-miRNA secondary structure, which likely results in the decreased binding efficiency of proteins involved in pri-miRNA processing [97]. More recently, two additional reports confirmed m6A’s positive effect on miRNA biogenesis [98,99]. Both reports demonstrated that SERRATE (SE) [a multi-functional protein (also involved in miRNA biogenesis)] interacts with the m6A methyltransferase complex (MTC) in phase separated condensates. The SE driven phase separation was found to be crucial for the solubility of MTC component MTB [98,99]. In addition, m6A reader ECT2 was found to facilitate m6A-dependent pri-miRNA processing in both m6A-dependent and independent manners. In fact, their evidence indicated that the MTC recruits miRNA processing machinery to chromatin to facilitate co-transcriptional processing of this class of small RNAs [98]. Overall, m6A and its reading and writing machinery play crucial roles in miRNA biogenesis, but whether this RNA modification affects other miRNA-mediated regulatory pathways is still unknown.

NAD+ caps

NAD+ caps have been detected in several pri-miRNAs in the RNA pool obtained from 12-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings and flower buds [90]. The presence of a NAD+ cap on these pri-miRNAs was found to be conditional. For example, pri-miR158A was observed to have a NAD+ cap only in wild-type samples treated with abscisic acid (ABA) and in dxo1 mutant samples regardless of ABA treatment, while pri-miR398C was NAD+ capped only in the non-ABA treated wild-type samples. A tissue-specific pattern of NAD+ capping was also observed in some pri-miRNAs. For instance, pri-miRNA167A, pri-miRNA167D, and others were NAD+-capped in 12-day-old seedling tissue but not in flower buds, while others (e.g. pri-miRNA398C) were found with NAD+ caps in both seedling and unopened flower buds [90]. With this singular study identifying NAD+-capped pri-miRNAs, the knowledge base for this modification in miRNAs is very limited, thus it remains to be seen whether this modification affects miRNA biogenesis or function. This research question will require future experimental probing.

Pseudouridine (Ψ)

In a 2024 report, researchers focused on detecting Ψs in small RNAs namely microRNAs and epigenetically activated small interfering RNAs (easiRNAs) [100]. A combination of antibody-based Ψ detection alongside modified CMC-based protocols allowed the researchers to detect Ψ in small RNAs with high confidence. Ψ was found to be deposited in pri-miRNAs before they are cleaved into mature miRNAs, with DYSKERIN1 (DKC1) postulated to be one of the PUSs responsible for this deposition [100]. Additionally, Arabidopsis mutants lacking the homolog of yeast LOSS OF SUPPRESSION 1 (Los1+) that encodes a tRNA export factor (Exportin-t): PAUSED/HUA ENHANCER5 (PSD) showed a decrease in miRNA pseudouridylation. This study lays a solid foundation for pseudouridine research focused on miRNAs while simultaneously raising further questions that need to be interrogated in the future (e.g. Is Ψ deposited co-transcriptionally? Are there other proteins involved in Ψ-related miRNA biogenesis/action?).

Circular RNAs (circRNAs)

Initially observed in plants (1976 [101]) and considered to be viroids, circRNAs are single-stranded, covalently closed RNAs. They are formed by an altered splicing process called back-splicing during which the 3’ end of an exon ligates back to its own 5’ end or that of an upstream exon [102]. Functionally, circRNAs act as miRNA sponges, regulate transcription, affect salt stress response, and even produce peptides, with this latter functionality facilitated by m6A modifications [102,103]. So far only m6A and m1A have been observed in plant circRNAs. In fact, direct sequencing of circRNA enriched RNA samples from moso bamboo revealed that ~10% of the 470 detected circRNAs contained m6A [104]. Furthermore, the researchers of this study observed that most m6A sites occurred near the donor and acceptor splice sites that formed circRNAs hinting at m6A’s important role in the formation of circRNAs. Additionally, m1A was observed in circRNAs from petunia [83]. In this study (previously discussed in the m1A section under mRNAs), 134 circRNAs were found to contain m1A modifications. Like the trend in mRNAs, the m1A peaks in circRNA were altered by ethylene treatment. In the study investigating differential m1A in tomato fruit ripening, m1A was also observed to be differentially deposited on circRNAs [84]. Specifically, 38 circRNAs were found to contain m1A with a general trend of circRNA m1A methylation levels going up as the fruit ripens [84].

Methods focused on studying circRNAs often involve treating RNA samples with RNase R, which adds an additional step in sample preparation. Combined with the lower expression levels of these RNAs, it is difficult to meaningfully detect and interpret circRNA modifications. However, with constant sequencing innovations and improvements, better detection of possible circRNA modifications and identification of the roles they play in circRNA biogenesis/function are imminent in future research projects.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs)

lncRNAs traditionally include a variety of RNAs obtained from a variety of RNA Polymerases (RNAPs), with the only common factor being their role in functions other than protein production. However, recently, scientists have tried to clarify the definition of lncRNAs to RNAPII transcripts that are more than 500 nucleotides in length [105]. Thus, the identification of epitranscriptomic marks in lncRNAs is usually a side note in transcriptome-wide studies that mostly focus on mRNAs. For instance, in the studies profiling m1A, 476 lncRNAs from petunia, and 14 lncRNAs from tomato were identified as m1A modified [83,84]. In addition to m1A, m5C was also reported in Arabidopsis lncRNAs [78]. While these modifications have been noted in lncRNAs, their function and impact on a given lncRNA’s biogenesis, turnover, and function remains to be investigated.

Meanwhile, m6A has been identified in lncRNAs using traditional m6A-IP sequencing as well as direct RNA sequencing [106,107]. Notable observations made by researchers include a uniform pattern of m6A site distribution along the 293 m6A lncRNAs that shifted to the 3’ end if filtered for highly methylated examples. lncRNAs were also found to have a lower density of m6A sites as compared to mRNAs, while m6A carrying lncRNAs were found to be expressed at a higher level overall [107]. Additionally, the analysis of various MTC mutant plants has revealed the possibility of yet unknown methyltransferases that could methylate lncRNAs. Particularly interesting is the observation that a mutation in the MTC component VIRILIZER resulted in the detection of more novel m6A sites in lncRNAs [107]. These observations require future experimental follow-up with a true focus on lncRNA biology in future studies.

Conclusion

The study of epitranscriptomic modifications emerged in the 1960s with the initial identification of modified nucleotides on rRNAs and tRNAs. The idea that RNA modifications could represent another layer of gene regulation with the notable discovery that RNA modifications occur in mRNAs in the 1970s, initiated more intense attention to this area of study by the scientific community. The work of many groups is now focused on mapping and understanding the epitranscriptome and its effects specifically on mRNAs. However, the ability to isolate distinct classes of ncRNAs (such as miRNAs and lncRNAs) and the progress made in the study of these functional ncRNAs have made it clear that a re-focus on ncRNA research could unravel the full potential of RNA modifications in regulating living organism development. As highlighted in this review, work on ncRNA modifications reveals crucial roles for these post-transcriptional regulators on plant development and stress responses. As more modifications are mapped genome-wide and their modifying enzymes identified and characterized, it will become possible to use these powerful gene expression regulators to answer current and future challenges in crop plant improvement.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank members of the BDG lab both past and present for helpful discussions.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the United States National Science Founcation grants [MCB-2427729] and [IOS-2023310] to BDG. The funders had no role in study design; literature collection; and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript; Directorate for Biological Sciences [IOS-2023310].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Author contributions

SSB, MP, and BDG wrote and edited this Review Article. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Data availability statement

No data were generated in this work.

References

- [1].Cohn WE, Volkin E.. Nucleoside-5'-Phosphates from Ribonucleic Acid. Nature. 1951;167(4247):483–484. doi: 10.1038/167483a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Davis FF, Allen FW. Ribonucleic acids from yeast which contain a fifth nucleotide. J Biol Chem. 1957;227(2):907–915. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)70770-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cappannini A, Ray A, Purta E, et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modifications and related information. 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52(D1):D239–D244. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Motorin Y, Helm M. RNA nucleotide methylation. WIREs RNA. 2011;2(5):611–631. doi: 10.1002/wrna.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chery M, Drouard L, Manavella P. Plant tRNA functions beyond their major role in translation. J Exp Bot. 2023;74(7):2352–2363. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erac483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bjork GR, Gustafsson CED, Hagervall TG, et al. TRANSFER RNA MODIFICATION. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56(1):263–285. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.001403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Weixlbaumer A, Murphy FV, Dziergowska A, et al. Mechanism for expanding the decoding capacity of transfer RNAs by modification of uridines. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14(6):498–502. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wang Y, Pang C, Li X, et al. Identification of tRNA nucleoside modification genes critical for stress response and development in rice and Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17(1):261. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1206-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sun L, Xu Y, Bai S, et al. Transcriptome-wide analysis of pseudouridylation of mRNA and non-coding RNAs in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2019;70(19):5089–5600. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Machnicka MA, Olchowik A, Grosjean H, et al. Distribution and frequencies of post-transcriptional modifications in tRnas. RNA Biol. 2014;11(12):1619–1629. doi: 10.4161/15476286.2014.992273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Xie Y, Gu Y, Shi G, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of pseudouridine synthase family in Arabidopsis and maize. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5):2680. doi: 10.3390/ijms23052680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fitzek E, Joardar A, Gupta R, et al. Evolution of Eukaryal and archaeal pseudouridine synthase Pus10. J Mol Evol. 2018;86(1):77–89. doi: 10.1007/s00239-018-9827-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Niu Y, Liu L, Manavella P. RNA pseudouridine modification in plants. J Exp Bot. 2023;74(21):6431–6447. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erad323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Deogharia M, Mukhopadhyay S, Joardar A, et al. The human ortholog of archaeal Pus10 produces pseudouridine 54 in select tRnas where its recognition sequence contains a modified residue. RNA. 2019;25(3):336–351. doi: 10.1261/rna.068114.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Marcu KB, Mignery RE, Dudock BS. Complete nucleotide sequence and properties of the major species of glycine transfer RNA from wheat germ. Biochemistry. 1977;16(4):797–806. doi: 10.1021/bi00623a036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Guo Q, Ng PQ, Shi S, et al. Arabidopsis TRM5 encodes a nuclear-localised bifunctional tRNA guanine and inosine-N1-methyltransferase that is important for growth. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(11):e0225064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Jin X, Lv Z, Gao J, et al. AtTrm5a catalyses 1-methylguanosine and 1-methylinosine formation on tRnas and is important for vegetative and reproductive growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(2):883–898. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Burgess AL, David R, Searle IR. Conservation of tRNA and rRNA 5-methylcytosine in the kingdom plantae. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15(1):199. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0580-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cui X, Liang Z, Shen L, et al. 5-methylcytosine RNA methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant. 2017;10(11):1387–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chen P, Jäger G, Zheng B. Transfer RNA modifications and genes for modifying enzymes in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10(1):201. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tang J, Jia P, Xin P, et al. The Arabidopsis TRM61/TRM6 complex is a bona fide tRNA N1-methyladenosine methyltransferase. J Exp Bot. 2020;71(10):3024–3036. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Aslam M, Huang X, Yan M, et al. TRM61 is essential for Arabidopsis embryo and endosperm development. Plant Reprod. 2022;35(1):31–46. doi: 10.1007/s00497-021-00428-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Liu F, Clark W, Luo G, et al. ALKBH1-mediated tRNA demethylation regulates translation. Cell. 2016;167(3):816–828.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Macari F, El-Houfi Y, Boldina G, et al. TRM6/61 connects PKCα with translational control through tRnai(met) stabilization: impact on tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2016;35(14):1785–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Saneyoshi M, Ohashi Z, Harada F, et al. Isolation and characterization of 2-methyladenosine from Escherichia coli RNAGlu2, tRNAAsp1, tRNAHis1 and tRNAArg. Biochim et Biophys Acta (BBA). 1972;262(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(72)90212-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Barciszewska MZ, Keith G, Kubli E, et al. The primary structure of wheat germ tRNAArg–the substrate for arginyl-tRnaarg: protein transferase. Biochimie. 1986;68(2):319–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Grimm M, Nass A, Schüll C, et al. Nucleotide sequences and functional characterization of two tobacco UAG suppressor tRnagln isoacceptors and their genes. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;38(5):689–697. doi: 10.1023/A:1006068303683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Duan H-C, Zhang C, Song P, et al. C2-methyladenosine in tRNA promotes protein translation by facilitating the decoding of tandem m2A-tRNA-dependent codons. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):1025. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-45166-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Benítez-Páez A, Villarroya M, Armengod M-E. The Escherichia coli RlmN methyltransferase is a dual-specificity enzyme that modifies both rRNA and tRNA and controls translational accuracy. RNA. 2012;18(10):1783–1795. doi: 10.1261/rna.033266.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Leihne V, Kirpekar F, Vågbø CB, et al. Roles of Trm9- and ALKBH8-like proteins in the formation of modified wobble uridines in Arabidopsis tRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(17):7688–7701. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Schaffrath R, Leidel SA. Wobble uridine modifications–a reason to live, a reason to die?! RNA Biol. 2017;14(9):1209–1222. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2017.1295204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Nakai Y, Horiguchi G, Iwabuchi K, et al. tRNA wobble modification affects leaf cell development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019;60(9):2026–2039. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcz064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Philipp M, John F, Ringli C. The cytosolic thiouridylase CTU2 of Arabidopsis thaliana is essential for posttranscriptional thiolation of tRnas and influences root development. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14(1):109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zheng X, Chen H, Deng Z, et al. The tRNA thiolation-mediated translational control is essential for plant immunity. In: Weigel D, editor. eLife. Vol. 13. 2024. p. e93517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chen Z, Zhang H, Jablonowski D, et al. Mutations in ABO1/ELO2, a subunit of holo-elongator, increase abscisic acid sensitivity and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(18):6902–6912. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00433-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhou X, Hua D, Chen Z, et al. Elongator mediates ABA responses, oxidative stress resistance and anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009;60(1):79–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03931.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Woloszynska M, Le Gall S, Van Lijsebettens M. Plant Elongator-mediated transcriptional control in a chromatin and epigenetic context. Biochim et Biophys Acta (BBA). 2016;1859(8):1025–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2016.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Skylar A, Matsuwaka S, Wu X. ELONGATA3 is required for shoot meristem cell cycle progression in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Dev Biol. 2013;382(2):436–445. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ramírez V, González B, López A, et al. A 2’-O-Methyltransferase responsible for transfer RNA anticodon modification is pivotal for resistance to pseudomonas syringae DC3000 in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2018;31(12):1323–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Janssen KA, Xie Y, Kramer MC, et al. Data independent acquisition for the detection of mononucleoside RNA modifications by mass spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2022;33(5):885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Rafels-Ybern À, Torres AG, Grau-Bove X, et al. Codon adaptation to tRnas with inosine modification at position 34 is widespread among eukaryotes and present in two bacterial phyla. RNA Biol. 2017;15(4–5):500–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Zhou W, Karcher D, Bock R. Identification of enzymes for adenosine-to-inosine editing and discovery of cytidine-to-uridine editing in nucleus-encoded transfer RNAs of arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2014;166(4):1985–1997. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.250498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Delannoy E, Le Ret M, Faivre-Nitschke E, et al. Arabidopsis tRNA adenosine deaminase arginine edits the wobble nucleotide of chloroplast tRnaarg(ACG) and is essential for efficient chloroplast translation. Plant Cell. 2009;21(7):2058–2071. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.066654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Karcher D, Bock R. Identification of the chloroplast adenosine-to-inosine tRNA editing enzyme. RNA. 2009;15(7):1251–1257. doi: 10.1261/rna.1600609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Bavi RS, Kamble AD, Kumbhar NM, et al. Conformational preferences of modified nucleoside N2-methylguanosine (m2G) and its derivative N2, N2-dimethylguanosine (m22G) occur at 26th position (Hinge region) in tRNA. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2011;61(3):507–521. doi: 10.1007/s12013-011-9233-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Pallan PS, Kreutz C, Bosio S, et al. Effects of N2,N2 -dimethylguanosine on RNA structure and stability: crystal structure of an RNA duplex with tandem m2 2G: A pairs. RNA. 2008;14(10):2125–2135. doi: 10.1261/rna.1078508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Funk HM, Zhao R, Thomas M, et al. Identification of the enzymes responsible for m2,2G and acp3U formation on cytosolic tRNA from insects and plants. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(11):e0242737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Arrivé M, Bruggeman M, Skaltsogiannis V, et al. A tRNA-modifying enzyme facilitates RNase P activity in Arabidopsis nuclei. Nat Plants. 2023;9(12):2031–2041. doi: 10.1038/s41477-023-01564-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Piekna-Przybylska D, Decatur WA, Fournier MJ. The 3D rRNA modification maps database: with interactive tools for ribosome analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(suppl_1):D178–D183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ganot P, Bortolin ML, Kiss T. Site-specific pseudouridine formation in preribosomal RNA is guided by small nucleolar RNAs. Cell. 1997;89(5):799–809. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80263-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kiss-László Z, Henry Y, Bachellerie J-P, et al. Site-specific ribose methylation of preribosomal RNA: a novel function for small nucleolar RNAs. Cell. 1996;85(7):1077–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81308-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Decatur WA, Fournier MJ. rRNA modifications and ribosome function. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27(7):344–351. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)02109-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Smirnova J, Loerke J, Kleinau G, et al. Structure of the actively translating plant 80S ribosome at 2.2 Å resolution. Nat Plants. 2023;9(6):987–1000. doi: 10.1038/s41477-023-01407-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Gay DM, Lund AH, Jansson MD. Translational control through ribosome heterogeneity and functional specialization. Trends Biochem Sci. 2022;47(1):66–81. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2021.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].R�cz I, Kir�ly I, L�sztily D. Effect of light on the nucleotide composition of rRNA of wheat seedlings. Planta. 1978;142(3):263–267. doi: 10.1007/BF00385075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Brown JWS, Echeverria M, Qu L-H, et al. Plant snoRNA database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(1):432–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Chen H-M, Wu S-H. Mining small RNA sequencing data: a new approach to identify small nucleolar RNAs in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(9):e69. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Cottilli P, Itoh Y, Nobe Y, et al. Cryo-EM structure and rRNA modification sites of a plant ribosome. Plant Commun. 2022;3(5):100342. doi: 10.1016/j.xplc.2022.100342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Lermontova I, Schubert V, Börnke F, et al. Arabidopsis CBF5 interacts with the H/ACA snoRNP assembly factor NAF1. Plant Mol Biol. 2007;65(5):615–626. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9226-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Yu F, Liu X, Alsheikh M, et al. Mutations in SUPPRESSOR of VARIEGATION1, a factor required for normal chloroplast translation, suppress var2-mediated leaf variegation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20(7):1786–1804. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Lin D, Kong R, Chen L, et al. Chloroplast development at low temperature requires the pseudouridine synthase gene TCD3 in rice. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):8518. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-65467-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Wang Z, Sun J, Zu X, et al. Pseudouridylation of chloroplast ribosomal RNA contributes to low temperature acclimation in rice. New Phytol. 2022;236(5):1708–1720. doi: 10.1111/nph.18479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Niu Y, Zheng Y, Zhu H, et al. The Arabidopsis mitochondrial pseudouridine synthase homolog FCS1 plays critical roles in plant development. Plant Cell Physiol. 2022;63(7):955–966. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcac060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Azevedo-Favory J, Gaspin C, Ayadi L, et al. Mapping rRNA 2’-O-methylations and identification of C/D snoRnas in Arabidopsis thaliana plants. RNA Biol. 2021;18(11):1760–1777. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2020.1869892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Wu S, Wang Y, Wang J, et al. Profiling of RNA ribose methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(7):4104–4119. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Barneche F, Steinmetz F, M E. Fibrillarin genes encode both a conserved nucleolar protein and a novel small nucleolar RNA involved in ribosomal RNA methylation inArabidopsis thaliana*. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(35):27212–27220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Neumann SA, Gaspin C, Sáez-Vásquez J. Plant ribosomes as a score to fathom the melody of 2’-O-methylation across evolution. RNA Biol. 2024;21(1):70–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Tang X-M, Ye T-T, You X-J, et al. Mass spectrometry profiling analysis enables the identification of new modifications in ribosomal RNA. Chin Chem Lett. 2023;34(3):107531. doi: 10.1016/j.cclet.2022.05.045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Song P, Tian E, Cai Z, et al. Methyltransferase ATMETTL5 writes mA on 18S ribosomal RNA to regulate translation in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2024;244(2):571–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Tang J, Chen S, Jia G. DetectiDetectiOn, regulation, and functions of RNA N6-methyladenosine modification in plants. Plant Commun. 2023;4(3):100546. doi: 10.1016/j.xplc.2023.100546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Tayier S, Tian E, Jia G. Regulatory role of RNA N6-methyladenosine modification in plants. Isr J Chem. 2024;64(5):e202400029. doi: 10.1002/ijch.202400029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Hu J, Xu T, Kang H. Crosstalk between RNA m6A modification and epigenetic factors in plant gene regulation. Plant Commun. 2024;101037(10):101037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Prall W, Ganguly DR, Gregory BD. The covalent nucleotide modifications within plant mRNAs: what we know, how we find them, and what should be done in the future. Plant Cell. 2023;35(6):1801–1816. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koad044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Zhong S, Li H, Bodi Z, et al. MTA is an Arabidopsis messenger RNA adenosine methylase and interacts with a homolog of a sex-specific splicing factor. Plant Cell. 2008;20(5):1278–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Wang C, Yang J, Song P, et al. FIONA1 is an RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase affecting Arabidopsis photomorphogenesis and flowering. Genome Biol. 2022;23(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s13059-022-02612-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Parker MT, Soanes BK, Kusakina J, et al. m6A modification of U6 snRNA modulates usage of two major classes of pre-mRNA 5’splice site. Elife. 2022;11:e78808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Miyokawa R, Sasaki E. The role of FIONA1 in alternative splicing and its effects on flowering regulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2024;243(6):2055–2060. doi: 10.1111/nph.19995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].David R, Burgess A, Parker B, et al. Transcriptome-wide mapping of RNA 5-methylcytosine in Arabidopsis mRNAs and noncoding RNAs. Plant Cell. 2017;29(3):445–460. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Yang L, Perrera V, Saplaoura E, et al. m5C methylation guides systemic transport of messenger RNA over graft junctions in plants. Curr Biol. 2019;29(15):2465–2476.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Tang Y, Gao C-C, Gao Y, et al. OsNSUN2-mediated 5-methylcytosine mRNA modification enhances rice adaptation to high temperature. Dev Cell. 2020;53(3):272–286.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Yu F, Qi H, Gao L, et al. Identifying RNA modifications by direct RNA sequencing reveals complexity of epitranscriptomic dynamics in rice. Genom Proteom & Bioinf. 2023;21(4):788–804. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2023.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Lu L, Zhang X, Zhou Y, et al. Base-resolution m5C profiling across the mammalian transcriptome by bisulfite-free enzyme-assisted chemical labeling approach. Mol Cell. 2024;84(15):2984–3000.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Yang W, Meng J, Liu J, et al. The N1-methyladenosine methylome of petunia mRNA. Plant Physiol. 2020;183(4):1710–1724. doi: 10.1104/pp.20.00382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Ma L, Zuo J, Bai C, et al. The dynamic N-methyladenosine RNA methylation provides insights into the tomato fruit ripening. Plant J. 2024;120(5):2014–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Wang Y, Li S, Zhao Y, et al. NAD±capped RNAs are widespread in the Arabidopsis transcriptome and can probably be translated. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(24):12094–12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Zhang H, Zhong H, Zhang S, et al. NAD tagSeq reveals that NAD±capped RNAs are mostly produced from a large number of protein-coding genes in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(24):12072–12077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Hu H, Flynn N, Zhang H, et al. SPAAC-NAD-seq, a sensitive and accurate method to profile NAD±capped transcripts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118(13):e2025595118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Pan S, Li K, Huang W, et al. Arabidopsis DXO1 possesses deNadding and exonuclease activities and its mutation affects defense-related and photosynthetic gene expression. J Integr Plant Biol. 2020;62(7):967–983. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Kwasnik A, Wang V-F, Krzyszton M, et al. Arabidopsis DXO1 links RNA turnover and chloroplast function independently of its enzymatic activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(9):4751–4764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Yu X, Willmann MR, Vandivier LE, et al. Messenger RNA 5' NAD+ capping is a dynamic regulatory epitranscriptome mark that is required for proper response to abscisic acid in Arabidopsis. Dev Cell. 2021;56(1):125–140.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Xiao C, Li K, Hua J, et al. Arabidopsis DXO1 activates RNMT1 to methylate the mRNA guanosine cap. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):202. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-35903-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Mititelu M-B, Hudeček O, Gozdek A, et al. Arabidopsis thaliana NudiXes have RNA-decapping activity. RSC Chem Biol. 2023;4(3):223–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Li B, Li D, Cai L, et al. Transcriptome-wide profiling of RNA N4-cytidine acetylation in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa. Mol Plant. 2023;16(6):1082–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2023.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Wang W, Liu H, Wang F, et al. N4-acetylation of cytidine in mRNA plays essential roles in plants. Plant Cell. 2023;35(10):3739–3756. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koad189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Ma L, Zheng Y, Zhou Z, et al. Dissection of mRNA ac4C acetylation modifications in AC and Nr fruits: insights into the regulation of fruit ripening by ethylene. Mol Horticul. 2024;4(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Li M, Yu B. Recent advances in the regulation of plant miRNA biogenesis. RNA Biol. 2021;18(12):2087–2096. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2021.1899491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Bhat SS, Bielewicz D, Gulanicz T, et al. mRNA adenosine methylase (MTA) deposits m6A on pri-miRnas to modulate miRNA biogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(35):21785–21795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2003733117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Zhong S, Li X, Li C, et al. SERRATE drives phase separation behaviours to regulate m6A modification and miRNA biogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2024;26(12):2129–2143. doi: 10.1038/s41556-024-01530-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Bai H, Dai Y, Fan P, et al. The METHYLTRANSFERASE B–SERRATE interaction mediates the reciprocal regulation of microRNA biogenesis and RNA m6A modification. J Integr Plant Biol 2024;66(12):2613–2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Herridge RP, Dolata J, Migliori V, et al. Pseudouridine guides germline small RNA transport and epigenetic inheritance. Nat Struct & Mol Biol. 2024. doi: 10.1038/s41594-024-01392-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Sanger HL, Klotz G, Riesner D, et al. Viroids are single-stranded covalently closed circular RNA molecules existing as highly base-paired rod-like structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73(11):3852–3856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]