Abstract

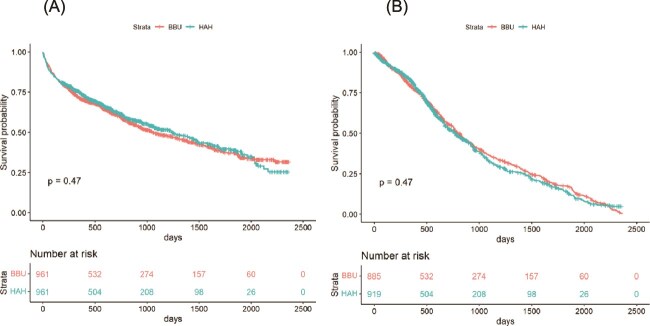

Objectives

To compare the effectiveness and safety of Hospital-at-Home based on Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA-HaH) for older adults with bed-based Intermediate Care Unit (BBU).

Design

Cohort study comparing all consecutive CGA-HaH cases managed between January 2018 and December 2023 with contemporary BBU-matched controls at the largest geriatric care provider in Barcelona.

Methods

We linked all intermediate care admissions at Parc Sanitari Pere Virgili to the Catalan health information system data to track patients’ trajectories from 6 months before the index episode to June 2024. Patients admitted to CGA-HaH were matched to BBU controls using propensity score matching (PSM) based on their baseline characteristics. We used multivariable linear regression to assess the association of CGA-HaH with the percentage of days spent at home (%DSH) and Cox regression to assess the risk of death and first re-hospitalisation.

Results

We included 1180 consecutive CGA-HaH and 10,528 BBU episodes. CGA-HaH patients were significantly older and more functionally impaired and had better socioeconomic status. After PSM, we compared 961 CGA-HaH and 961 BBU patients, with a mean follow-up of 705 days (SD 593). CGA-HaH patients had a 7.4 higher %DSH (95% CI: 4.5–10.2, P < 0.001) with similar first re-hospitalisation [HR 1.02 (95% CI: 0.91–1.1)] and mortality risk [HR: 0.93 (95% CI: 0.81–1.06)].

Conclusions

Our results suggest that CGA-Hospital-at-Home is a viable alternative to traditional inpatient intermediate care for older adults, offering relevant advantages such as increased time spent at home without a rise in mortality.

Keywords: hospital-at-home, integrated care, health crises, multimorbidity, older people

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Key Points

The CGA-HaH proved to provide more days spent at home without affecting mortality.

Strategies are needed to ensure access to CGA-HaH programmes for vulnerable populations.

The CGA-HaH model offers a viable, person-centred alternative to traditional inpatient care for older adults with health crises.

Introduction

In recent years, innovative approaches have emerged to address the complex health and social care needs of older adults living with frailty and chronic conditions. Conventional hospitalisation is often overloaded and might be associated with potential risks for older individuals, such as acute onset of functional decline, delirium and other geriatric syndromes [1–3].

The British Geriatrics Society (BGS) has highlighted the importance of providing high-quality healthcare outside hospital settings for older adults, particularly during crises or urgent medical needs [4]. In response, several community-based models have been developed to reduce the adverse effects of hospitalisation whilst maintaining or improving care quality. Amongst these, the Hospital-at-Home (HaH) model has gained prominence, demonstrating effectiveness across diverse populations and medical conditions, including heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hip fractures and stroke [5–8] and showing the potential to prevent geriatric syndromes, such as delirium, whilst promoting better functional outcomes [9–11].

Beyond health related benefits, HaH is usually preferred by patients and has demonstrated efficiency and patient satisfaction [12, 13]. However, its feasibility depends on specific patient selection criteria, including clinical stability and the availability of a valid caregiver to provide support [14].

Although recent scientific evidences support the effectiveness of HaH, the models analysed often focus exclusively on hospital admission avoidance (‘step-up’ care) [15–17]. Furthermore, the translation of scientific evidence from experimental studies into sustainable programmes within clinical and community settings remain limited [18].

Since the late 20th century, Catalonia has pioneered integrated intermediate care, combining interdisciplinary services with a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA)-based approach to ensure continuity of care, enhance recovery and restore independence at the interface between home and acute care [19]. In order to extend CGA-based interventions to community settings, Catalonia started to pilot home-based care schemes, integrating CGA into domiciliary healthcare services (CGA-HaH) [20]. As previously reported by our group, this innovative approach expanded the scope of intermediate care, providing an effective alternative to inpatient care for older adults experiencing disabling health crises by reducing hospital stays and overall costs [7, 20] whilst improving functional outcomes [21, 22]. Additionally, the model has demonstrated adaptability, maintaining its effectiveness even during the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic [23]. Remarkably, the CGA-HaH model implemented in Catalonia stands out for its ability to incorporate hospital admission avoidance (‘step-up’), early discharge from the hospital (‘step-down’), and mixed-care programmes, making it suitable for various clinical and community settings.

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the CGA-HaH model as an alternative to traditional inpatient care for older adults, using a large comprehensive cohort and focusing on days spent at home—a previously unexplored patient-centred outcome for this care model [24].

Methods

The CGA-HaH and the bed-based intermediate care unit (BBU): models of integrated care

The Parc Sanitari Pere Virgili (PSPV) Intermediate Care Hospital was established in 2009 and provides both hospital beds and a home-based care service to a total health service area of ⁓900 000 residents in Barcelona. It specialises in older adults with chronic disease exacerbations or mild acute events (e.g. urinary tract infections) in complex clinical contexts like dementia. Providing both step-down (early supported discharge) and step-up (admission avoidance) care, it integrates diagnosis, tailored treatment and rehabilitation to ensure continuity of care and support functional recovery.

The CGA-HaH model was launched with one team in January 2018 and expanded to three teams by October 2021, collectively managing up to 45 patients at home. Prior publications have described this interdisciplinary model, which is based on CGA principles, multidisciplinary care and individualised treatment plans, as well as its governance and integration within the local healthcare system [7, 20, 21, 23]. Patients in both CGA-HaH and BBU services receive an initial geriatric nursing assessment within 12 h of referral and a geriatrician visit within 24 h. A standardised CGA-based protocol was implemented, involving geriatricians, nurses, physiotherapist and occupational therapists, social workers and remote support from clinical pharmacists and speech therapists, as needed, with access to diagnostic and medical procedures. In BBU patients have 24 h/7 days access to onsite care, whilst in CGA-HaH, visits from healthcare professionals are available 12 h/7 days.

In CGA-HaH, all patients are assessed within 24 h of inclusion by a physician and a nurse, who determine the frequency of follow-up evaluations based on the patient’s needs, including daily assessments if necessary. Within the same timeframe, a physiotherapist and an occupational therapist evaluate the patient and collaboratively establish a personalised rehabilitation plan. At night, patients have access to an on-call geriatrician or conventional emergency care services. Both models discharge patients to primary care upon achieving therapeutic goals or transfer them to acute hospitals as necessary, following predefined protocols. The length of stay (LOS) for both programmes is ⁓4–6 weeks.

To be admitted to the CGA-HaH programme, patients require demonstrated hemodynamic stability and do not require 24-h acute ward monitoring. The presence of cognitive impairment or living in residential care is not exclusionary. For the present analysis, we excluded patients receiving palliative care or long-term hospitalisations.

Design

This cohort study compared clinical outcomes of all patients referred to the CGA-HaH, between January 2018 and December 2023 with a contemporary matched sample of patients admitted to the BBU.

We linked all episodes to the Catalan health information system data files to track patients’ trajectories from 6 months before the index episode to June 2024, with a minimum follow-up of 6 months and a maximum of ⁓6 years.

Data sources

The Catalan health information system collects data of all residents of Catalonia (7.5 million people) identified with a unique code which allows track through all the health administration registries: the mortality registry, the hospitals discharge minimum dataset (CMBD), the primary care minimum dataset (PC-CMBD) and the Pharmacy claims dataset. Diagnostic information is registered using International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes (ICD-9, for hospitals CMDB, and ICD-10, for PC-CMBD), and the Pharmacy Claims Registry uses WHOCC–ATC Index codes (World Health Organisation Collaborating Centre– Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical). After quality assessment, data is available to public research organisations through the Public Data Analysis for Health Research and Innovation programme (PADRIS), with warranted accomplishment of ethical principles and data protection.

Data was extracted after approval by the Ethics Committee of Vall d’Hebron Research Institute, PR(AG)107/2020. Given the nature of the data (anonymized data retrospectively extracted from public health care records), informed consent was not required.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the percentage of days spent at home (%DSH) between discharge and the end of follow-up, calculated by subtracting hospitalisation or institutionalisation days from the total days of follow-up (from the day of discharge at the end of the index episode until death or end of follow-up, 30 June 2024). Days of hospitalisation were obtained from the CMBD databases. Days of institutionalisation in residential care were obtained from the periods in which Pharmacy claims were assigned to a residential care setting.

Secondary outcomes included LOS for the index episode, the risk of death and first re-hospitalisation, and new admissions to residential care at the 6-month follow-up.

Covariates

‘Step-up’ or ‘step-down’ episodes were classified by exploring previous hospitalisation patterns: the episode was considered a step-up if there was not a hospital discharge within the 3 days before the index admission or if the admission was through the emergency department or if the previous admission was a short hospitalisation (LOS ˂2 days) for minor surgery.

Individual socioeconomic status was obtained from the Pharmacy claims database [25]. In Catalonia, drug dispensation follows a system of copayment according to individuals’ income or the social security benefits received. Levels of copayment are defined as follows: exempt (nonworking or receiving noncontributory pension), less than €18 000, between €18 000 and €100 000, and more than €100 000 income per year. Given the small percentage of patients with an income more than €100 000 in our cohort (˂1%), the last two categories were merged.

Area level socioeconomic status was obtained from the primary care service areas (PCSA) deprivation index [26]. The PCSA index ranges from 0 (less deprived) to 100 (more deprived).

Other covariates included age, sex, initial Barthel Index, comorbidity assessed using the Adjusted Morbidity Groups (AMG) [27], polypharmacy (5–9 drugs) and hyperpolypharmacy (10 or more drugs). The number of drugs was determined by counting unique ATC codes recorded in the Pharmacy claims database during the 3-month period preceding the month before the start of the health crisis.

The main diagnosis for the index episode (reason for admission) was categorised based on ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes, classified to wider categories using the Clinical Classification Software (CCS) [28]. Two geriatricians (LMP and AG) reviewed and consolidated the 125 unique CCS codes for CGA-HaH into 20 final diagnostic categories.

Statistical analysis

Cohort characteristics are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and absolute numbers plus percentages for categorical variables. Differences in baseline characteristics between CGA-HaH and BBU patients were analysed using the χ2 test for proportions and the t-Student test or the Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables.

To assess the effectiveness and safety outcomes of CGA-HaH we selected a contemporary group of BBU episodes using Propensity Score Matching (PSM) with the matchit function in R [29]. First, we ensured an exact match based on the diagnostic categories, step-up/step-down status and the time (quarter) of admission. Then, we used a nearest-neighbour matching algorithm with a 1:1 ratio to match patients based on their propensity of CGA-HaH. Propensity values were obtained from a regression model considering the following covariates: age, sex, initial Barthel Index, AMG, hyper/polypharmacy, individual socioeconomic status and area level socioeconomic status, hospital or emergency department admissions in the previous 6 months, Intensive Care Unit stays in the previous 6 months, the time elapsed since the last hospitalisation and admissions from residential care. For the episodes that did not find a match, we repeated the process using an exact match only with CCS categories and step-up/step-down status. We assumed balance between groups in baseline characteristics if the standardised mean difference was <0.2.

We compared %DSH, LOS, survival, time to first hospital readmission and new admission to residential care at 6 months between the matched cohorts. We estimated the association of CGA-HaH with %DSH using multiple linear regression and adjusting for baseline characteristics. Time until the first hospitalisation and survival of CGA-HaH and BBU-matched cohorts were evaluated using Kaplan–Meier curves. The association of CGA-HaH with mortality risk and first re-hospitalisation was assessed with Cox regression, adjusting for baseline characteristics.

Statistical analysis was performed using RStudio (RStudio Team: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA).

Results

After removing repeated episodes, we analysed data from 11 708 unique patients admitted to BBU (10 528) or CGA-HaH (1180) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of selection criteria of patients enrolled in HaH and BBU. Note: HaH, hospital-at-home; BBU, bed-based intermediate care unit; PSM, Propensity Score Matching.

The mean follow-up was 769 days (SD 670). CGA-HaH patients were older, more functionally dependent and with slightly higher comorbidity, polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy than BBU, whilst their socioeconomic status was better (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients attended by the CGA-HaH and those attended by the BBU.

| CGA-HaH (n = 1180) | BBU (n = 10 528) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y), mean (SD) | 82.8 (10.0) | 79.5 (11.5) | <0.001 |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 658 (55.8) | 5673 (53.9) | 0.231 |

| Initial Barthel Index, mean (SD) | 52.8 (24.7) | 54.4 (30.4) | 0.014 |

| Polypharmacy, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| No | 230 (19.5) | 2773 (26.3) | |

| Polypharmacy | 612 (51.9) | 5136 (48.8) | |

| Hyperpolypharmacy | 338 (28.6) | 2619 (24.9) | |

| Comorbidity, AMG, mean (SD) | 133.4 (55.6) | 129.1 (54.3) | 0.010 |

| Area based socioeconomic status, mean (SD) | 34.6 (19.3) | 36.9 (17.6) | <0.001 |

| Individual socioeconomic status, n (%) | |||

| Exempt | 312 (26.4) | 2722 (25.9) | <0.001 |

| ≤18 000 € | 434 (36.8) | 4880 (46.3) | |

| >18 000 € | 434 (36.8) | 2926 (27.8) | |

| Step-up, n (%) | 500 (42.4) | 1860 (17.7) | <0.001 |

| Previously admitted to Acute Care (6 m), n (%) | 861 (73.0) | 6934 (65.9) | <0.001 |

| Previously admitted to ICU (6 m), n (%) | 11 (0.9%) | 165 (1.6) | 0.116 |

| Admitted from residential care, n (%) | 36 (3) | 567 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up (days), mean (SD) | 624.4 (524.8) | 785.6 (682) | <0.001 |

AMG, Adjusted Morbidity Groups; m, months; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; CGA-HaH, CGA-hospital-at-home; BBU, bed-based intermediate care unit.

The most frequent admission diagnoses for CGA-HaH were femur and hip fractures, followed by heart failure, although other diagnostics typically attended in intermediate care were also common (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of admission diagnoses within the CGA-HaH and BBU cohorts. Note: CGA-HaH, CGA-hospital-at-home; BBU, bed-based intermediate care unit.

After PS matching, we obtained two comparable cohorts of 961 patients (see Appendix 1 in the Supplementary Data section for the full details). The mean follow-up time of the matched cohort was 705 days (SD 593), 657 days (SD 543) in CGA-HaH and 754 days (SD 636) in BBU. Matching reduced the standardised mean differences between groups to ˂0.2 for all baseline characteristics (see Appendix 2 in the Supplementary Data section). The 219 patients who could not be matched showed higher AMG and better socioeconomic status (see Appendix 3 in the Supplementary Data section for the full details).

Table 2 shows the outcomes’ comparison between CGA-HaH and BBU after PSM.

Table 2.

Comparison of outcome measures between patients attended by the CGA-HaH patients and the matched BBU sample.

| CGA-HaH (n = 961) | BBU (n = 961) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of days spent at home, mean (SD) | 70.6 (33.1) | 63.4 (36.35) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay (d), mean (SD) | 34.7 (20.2) | 39.9 (22.7) | <0.001 |

| New admission to residential care within 6 m of discharge, n (%) | 26 (2.8) | 82 (8.8) | <0.001 |

CGA-HaH, CGA-hospital-at-home; BBU, bed-based intermediate care unit; d, days; m, months.

Using multivariable linear regression analysis, we estimated an increase of 7.4%DSH (95% CI: 4.5–10.2, P < 0.001) in CGA-HaH compared to BBU.

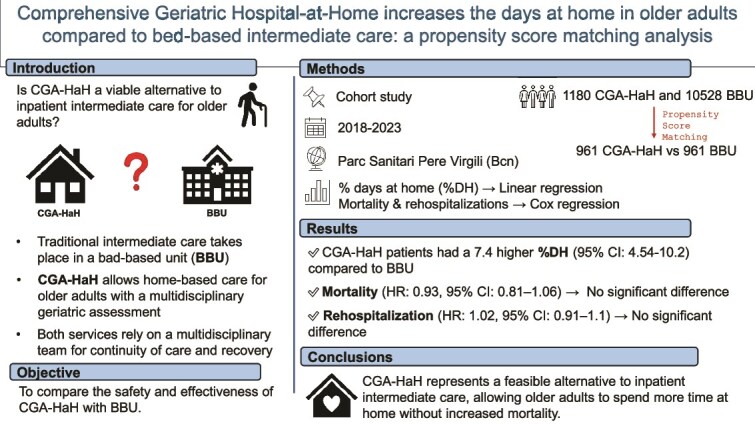

Figure 3 shows Kaplan–Meier curves for survival and time to the first re-hospitalisation of CGA-HaH and BBU. By Multivariate Cox regression analysis, there were no significant differences in mortality risk [HR 0.93 (95% CI: 0.81–1.06), P = 0.269] and first re-hospitalisation [HR 1.02 (95% CI: 0.91–1.10), P = 0.691] between CGA-HaH and BBU (see Appendix 4 in the Supplementary Data section).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing survival (A) and first re-hospitalisation (B) of patients attended by the CGA-HaH and those attended by the BBU. Note: CGA-HaH, CGA-hospital-at-home; BBU, bed-based intermediate care unit.

Discussion

This study, conducted in a cohort of consecutive patients admitted to a CGA-HaH unit during 6 years and followed up for almost 2 years, showed that the CGA-HaH model, compared to BBU, increased the percentage of days spent at home without affecting the risk of mortality and first re-hospitalisations. Additionally, CGA-HaH patients had shorter lengths of stay and fewer new residential care admissions in the 6 months following discharge.

Recent research increasingly supports the effectiveness of providing hospital care at home for older adults with comorbidities, either to avoid hospital admission (‘step-up’) or to anticipate discharge (‘step-down’) [6, 15, 16, 17, 30]. Numerous studies, including multiple Cochrane reviews, have shown comparable outcomes in mortality and readmission rates between HaH and traditional inpatient care, highlighting potential reductions in residential care admission and costs [5, 16, 31] [32].

Notably, HaH mitigates risks associated with traditional hospitalisation, such as immobilisation, delirium, sensory deprivation [33] and nosocomial infections [34].

A key challenge in evaluating HaH intervention is the lack of standardised models [35], as implementation often varies depending on regional healthcare systems and available resources. Many programmes focus solely on providing acute care for health crises with associated disability, usually excluding essential rehabilitation approaches [36] for older adults with complex needs. In contrast, our CGA-HaH model integrates a multidisciplinary team, including geriatricians, nurses, social workers and physiotherapist and occupational therapists, ensuring comprehensive and continued care from acute management through rehabilitation. This ability to manage both the acute and the post-acute phases of medical conditions reflects the adaptability and strength of our CGA-HaH model.

Our findings showed that the CGA-HaH is effective for older, frailer patients with higher rates of multimorbidity and polypharmacy, emphasising the potential of CGA-HaH to address critical challenges faced by social and health care systems worldwide.

Furthermore, our study focused on patient-centred goal such as days at home [24], which is highly valued by this specific population and reflects a reduction of hospitalisation rates and residential care admissions throughout the entire follow-up period. DSH is recognised as a key indicator of healthcare quality, with applications in post-stroke and dementia care [37–39]. Studies show that higher DSH is linked to lower disability and better patient-reported outcomes, supporting its use as a pragmatic measure for healthcare evaluation. Previous studies have shown mixed results regarding length of stay reduction. Whilst some suggest that HaH care models may lead to longer LOS [16, 31, 40] due to the complex nature of home-based care, our results are consistent with prior research from our group [22], indicating that CGA-HaH can effectively reduce global LOS without compromising the quality of care. This supports the hypothesis that individualised, multidisciplinary interventions, tailored to patients’ profiles, enhance efficiency and effectiveness.

Interestingly, patients admitted to CGA-HaH tended to have higher socioeconomic status, which may reflect better access to resources, including formal caregivers and more suitable home conditions, thus meeting the inclusion criteria for HaH admissions. This highlights the need to implement strategies to ensure equitable access to HaH programmes, especially for vulnerable populations who need a timely evaluation from social workers and might benefit from temporary social support at home.

Differences in admission diagnoses between groups provide valuable insights. CGA-HaH patients more commonly presented with conditions such as hip fractures and heart failure, where early discharge and rehabilitation at home are well-established strategies [7, 20, 22]. Conversely, cerebrovascular events were more prevalent amongst in-hospital patients, likely reflecting the need for specialised acute interventions. Importantly, results suggest that our mix (‘step-up’ and ‘step-down’) CGA-HaH model is effective across all diagnostic categories, reinforcing its versatility.

Beyond health related outcomes, CGA-HaH aligns with broader healthcare trends emphasising cost-effective, person-centred care services [41]. As the ageing population drives increased demand for healthcare services and rising healthcare costs, HaH models present a sustainable solution by reducing hospital stays and associated costs whilst improving patient satisfaction [42, 43]. However, their scalability requires strong financial and infrastructural support to integrate them seamlessly into existing healthcare systems. Integrated care strategies for managing health crises with associated disability within the community can play a pivotal role, providing alternatives to traditional in-bed hospitalisation.

The present study has some limitations. First, participants were not randomly assigned to groups, introducing potential selection bias. Although PSM was applied to enhance comparability, residual confounding may persist. Second, the analysis is based on data from a single hospital in Barcelona, which has pioneered this model, limiting the generalizability of our findings to other healthcare systems. Third, system-based follow-up data did not allow us to collect other patient-centred relevant outcomes, such as function and quality of life.

Despite these limitations, the study has several notable strengths. It evaluates an innovative CGA-integrated HaH model in a real-world setting, demonstrating the effectiveness of an implemented care model. The large sample size adds robustness and enhances the statistical power of the analysis. The use of the Catalan health information system data files strengthens the methodology by linking comprehensive healthcare data. The evaluation of different outcomes, emphasising a person-centred outcome as %DSH, provides a comprehensive understanding of the CGA-HaH model’s impact.

Future research should explore the generalizability of CGA-HaH programmes across diverse healthcare systems and assess the financial sustainability of HaH programmes and the long-term impact of CGA-HaH on health, functional recovery and quality of life of patients and caregivers. Finally, addressing socioeconomic disparities in access to HaH care will be essential to ensure equitable benefits and promote inclusive healthcare systems.

Conclusions

The CGA-HaH model offers a viable, person-centred alternative to traditional inpatient care for older adults with health crises with associated disability, providing more days spent at home, shorter hospital stays and reduced admissions to residential care without affecting mortality. These benefits appear consistent across a range of medical conditions, highlighting CGA-HaH as a key component of integrated geriatric care models. As healthcare systems grapple with the challenges associated with an ageing population, CGA-HaH represents a promising and efficient strategy for improving outcomes for older adults.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Tessa Mazzarone, Geriatrics Unit, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Pisa, Via Roma 67, Pisa 56126, Italy.

Laura M Pérez, Research on Aging, Frailty and Transitions in Barcelona (REFiT-BCN), Parc Sanitari Pere Virgili and Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), C/ Esteve Terradas 30, Barcelona 08023, Catalunya, Spain.

Lorena Villa, Research on Aging, Frailty and Transitions in Barcelona (REFiT-BCN), Parc Sanitari Pere Virgili and Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), C/ Esteve Terradas 30, Barcelona 08023, Catalunya, Spain; Department of Public Health, Mental Health, and Maternal and Child Health, University of Barcelona, Feixa Llarga, Barcelona 08907, Spain.

Oriol Planesas-Pérez, Research on Aging, Frailty and Transitions in Barcelona (REFiT-BCN), Parc Sanitari Pere Virgili and Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), C/ Esteve Terradas 30, Barcelona 08023, Catalunya, Spain.

Filippo M Verri, Institute of Geriatric Research (IFGF), Ulm University, Zollernring 26, Ulm 89073, BW, Germany.

Ana de Andrés, Research on Aging, Frailty and Transitions in Barcelona (REFiT-BCN), Parc Sanitari Pere Virgili and Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), C/ Esteve Terradas 30, Barcelona 08023, Catalunya, Spain.

Ana Gonzalez-de Luna, Research on Aging, Frailty and Transitions in Barcelona (REFiT-BCN), Parc Sanitari Pere Virgili and Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), C/ Esteve Terradas 30, Barcelona 08023, Catalunya, Spain.

Maria F Velarde, Research on Aging, Frailty and Transitions in Barcelona (REFiT-BCN), Parc Sanitari Pere Virgili and Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), C/ Esteve Terradas 30, Barcelona 08023, Catalunya, Spain.

Roger Martí-Tarradell, Research on Aging, Frailty and Transitions in Barcelona (REFiT-BCN), Parc Sanitari Pere Virgili and Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), C/ Esteve Terradas 30, Barcelona 08023, Catalunya, Spain.

Marco Inzitari, Research on Aging, Frailty and Transitions in Barcelona (REFiT-BCN), Parc Sanitari Pere Virgili and Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), C/ Esteve Terradas 30, Barcelona 08023, Catalunya, Spain; Faculty of Health Sciences, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC), Av. del Tibidabo 39-43, Barcelona 08035, Spain.

Aida Ribera, Research on Aging, Frailty and Transitions in Barcelona (REFiT-BCN), Parc Sanitari Pere Virgili and Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), C/ Esteve Terradas 30, Barcelona 08023, Catalunya, Spain; CIBER of Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP), Barcelona, Spain.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

This study has been funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) through the project PI22/00845 and co-funded by the European Union.

References

- 1. Merten H, Zegers M, de Bruijne MC et al. Scale, nature, preventability and causes of adverse events in hospitalised older patients. Age Ageing 2013;42:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: “she was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure”. JAMA 2011;306:1782–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet (London, England) 2014;383:911–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. SOCIETY BG . Bringing hospital care home: virtual wards and hospital at home for older people. 2022;10: Available from: https://www.bgs.org.uk/virtualwards. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Echevarria C, Brewin K, Horobin H et al. Early supported discharge/hospital At home for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review and meta-analysis. COPD 2016;13:523–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tibaldi V, Isaia G, Scarafiotti C et al. Hospital at home for elderly patients with acute decompensation of chronic heart failure: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1569–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Closa C, Mas MÀ, Santaeugènia SJ et al. Hospital-at-home integrated care program for older patients with Orthopedic processes: an efficient alternative to usual hospital-based care. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:780–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Langhorne P, Baylan S. Early supported discharge services for people with acute stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;7:CD000443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caplan GA, Coconis J, Board N et al. Does home treatment affect delirium? A randomised controlled trial of rehabilitation of elderly and care at home or usual treatment (the REACH-OUT trial). Age Ageing 2006;35:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Caplan GA, Coconis J, Woods J. Effect of hospital in the home treatment on physical and cognitive function: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005;60:1035–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leff B, Burton L, Mader SL et al. Comparison of functional outcomes associated with hospital at home care and traditional acute hospital care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:273–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B et al. Hospital-level care at home for acutely ill adults a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2020;172:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Costa-Font J, Elvira D, Mascarilla-Miró O. ‘Ageing in place’? Exploring elderly People’s housing preferences in Spain. Urban Stud 2009;46:295–316Available from:. 10.1177/0042098008099356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mäkelä P, Stott D, Godfrey M et al. The work of older people and their informal caregivers in managing an acute health event in a hospital at home or hospital inpatient setting. Age Ageing 2020;49:856–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Edgar K, Iliffe S, Doll HA et al. Admission avoidance hospital at home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2024;3:CD007491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arsenault-Lapierre G, Henein M, Gaid D et al. Hospital-At-home interventions vs in-hospital stay for patients with chronic disease who present to the emergency department. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:E2111568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shepperd S, Ellis G, Schiff R et al. Is comprehensive geriatric assessment admission avoidance Hospital at Home an alternative to hospital admission for older persons? Ann Int Med United States 2021;174:1633–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lai YF, Ko SQ. Time to shift the research agenda for Hospital at Home from effectiveness to implementation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev Engl 2024;3:ED000165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sezgin D, O’Caoimh R, O’Donovan MR et al. Defining the characteristics of intermediate care models including transitional care: an international Delphi study. Aging Clin Exp Res 2020;32:2399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mas MÀ, Closa C, Santaeugènia SJ et al. Hospital-at-home integrated care programme for older patients with orthopaedic conditions: early community reintegration maximising physical function. Maturitas 2016;88:65–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mas M, Santaeugènia SJ, Tarazona-Santabalbina FJ et al. Effectiveness of a hospital-at-home integrated care program as alternative resource for medical crises Care in Older Adults with complex chronic conditions. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018;19:860–3. Available from:. 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mas MÀ, Inzitari M, Sabaté S et al. Hospital-at-home integrated care programme for the management of disabling health crises in older patients: comparison with bed-based intermediate care. Age Ageing 2017;46:925–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Inzitari M, Arnal C, Ribera A et al. Comprehensive geriatric Hospital at Home: adaptation to referral and case-mix changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2023;24:3–9.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Groff AC, Colla CH, Lee TH. Days spent at home - a patient-Centered goal and outcome. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1610–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. García-Altés A, Ruiz-Muñoz D, Colls C et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in health and the use of healthcare services in Catalonia: analysis of the individual data of 7.5 million residents. J Epidemiol Community Health 2018;72:871–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Colls C, Mias M, García-Altés A. A deprivation index to reform the financing model of primary care in Catalonia (Spain). Gac Sanit 2020;34:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ministerio de Sanidad, consumo y bienestar. Informe del proyecto de Estratificación de la población por Grupos de Morbilidad Ajustados (GMA) en el. Sist Nac Salud 2018;33–9 Available from: http://www.mscbs.gob.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/pdf/informeEstratificacionGMASNS_2014-2016.pdf%0Ahttps://www.mscbs.gob.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/pdf/informeEstratificacionGMASNS_2014-2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clinical classifications software (CCS) for ICD-10-CM/PCS. Available from: https://catsalut.gencat.cat/ca/proveidors-professionals/registres-catalegs/catalegs/diagnostics-procediments/cim-10-mc-scp/fitxers/agrupadors/2022/index.html.

- 29. Sekhon JS. Multivariate and propensity score matching software with automated balance Ootimization: the matching pack-age for R. J Statist Soft 2011;42:1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aimonino Ricauda N, Tibaldi V, Leff B et al. Substitutive “hospital at home” versus inpatient care for elderly patients with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gonçalves-Bradley DC, Iliffe S, Doll HA et al. Early discharge hospital at home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;6:CD000356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Varney J, Weiland TJ, Jelinek G. Efficacy of hospital in the home services providing care for patients admitted from emergency departments: an integrative review. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2014;12:128–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Innovator C. Hospital at HomeSM care reduces costs, readmissions, and complications and enhances satisfaction for elderly patients. 2021;1–14.

- 34. Katz MJ, Roghmann M-C. Healthcare-associated infections in the elderly: what’s new. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2016;29:388–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Leff B, DeCherrie LV, Montalto M et al. A research agenda for hospital at home. J Am Geriatr Soc 2022;70:1060–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mas MÀ, Santaeugènia S. Hospital-at-home in older patients: a scoping review on opportunities of developing comprehensive geriatric assessment based services. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 2015;50:26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Quinn TJ, Dawson J, Lees JS et al. Time Spent at Home Poststroke: “Home-Time” a Meaningful and Robust Outcome Measure for Stroke Trials, Vol. 39. Stroke. Dallas, TX, United States, 2008, 231–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yu AYX, Fang J, Porter J et al. Hospital-based cohort study to determine the association between home-time and disability after stroke by age, sex, stroke type and study year in Canada. BMJ Open 2019;9:e031379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Qureshi N, Nuckols T, Tsugawa Y et al. Association between days spent at home and functional status and health among persons living with dementia. Age Ageing 2024;53:afae176. 10.1093/ageing/afae176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Conley J, O’Brien CW, Leff BA et al. Alternative strategies to inpatient hospitalization for acute medical conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wilkinson . The Solid Facts the Solid Facts, Vol. 46. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2008. www.euro.who.int. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cryer L, Shannon SB, Van Amsterdam M et al. Costs for “hospital at home” patients were 19 percent lower, with equal or better outcomes compared to similar inpatients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vilà A, Villegas E, Cruanyes J et al. Cost-effectiveness of a Barcelona home care program for individuals with multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:1017–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.